Abstract

During the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) worldwide, many countries have instructed the shutdown of all educational facilities to break the chain of virus transmission. Since March 2020, approximately 45 million students in Indonesia have adapted to online learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This study aimed to analyze Indonesian students’ perceptions of online schools using social media data, specifically Twitter. Based on the search query, there were 12,243 tweets collected from the Netlytic software from March 1st to 31st, 2021. From this social media platform, we found that students did not experience good things in an online school. Some of them might enjoy online school, but most of the students felt that it had a negative impact on them. In the word-level sentiment analysis, 1,649 words (81.59%) were considered negative words; for example, students frequently complained about how they felt ‘lazy’, ‘tired’, and ‘bored’. Meanwhile, the remaining 372 words (18.41%) were considered positive words as the students expressed their feelings with words like ‘comfortable’, ‘thanked God’, and ‘good’. Based on this finding, we suggest that educational facilitators prepare to adjust course materials and delivery to improve students’ online learning experiences.

Introduction

During the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) worldwide, many countries have instructed the shutdown of educational facilities to break the chain of virus transmission. As one of vulnerable citizens, children need to be protected from virus transmission, given that they socialize extensively at schools. Since March 2020, approximately 45 million students in Indonesia have adapted to online learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote1 The policy was implemented after The Circular Letter of the Ministry of Education and Culture No. 4/2020 on The Implementation of Education Policy in the Emergency of the Coronavirus Spreading Disease (COVID-19) was issued. The students were forced to study from home while the learning process in school was held online.

Many students were affected by this policy and experienced some inconveniences because the schools were closed for an indefinite period (Arsendy et al., Citation2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the well-being of Indonesian students both at school and home, notably since the students were required to attend class virtually, which potentially impedes feelings of school embeddedness. School shutdowns and online classes have compelled substantial changes in students from direct interactions with teachers and peers to online-only interfacing. Unforeseen and immanent disruptions may have indirect implications for student performance (Golberstein et al., Citation2020). Beyond school activities, students may still deal with more issues and stress regarding COVID-19’s potential effects on friendships, health, and the future (Magson et al., Citation2021).

Indonesia’s education is almost similar to that of India in terms of the traditional lecture-based approach in the classroom and the lack of digital interventions in educational activities (Muthuprasad et al., Citation2021). However, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced many schools in Indonesia to find creative methods on short notice. At that time, most schools applied online platforms such as Google Classroom, Zoom, and WhatsApp (Sakinah & Darmawan, Citation2022). However, it is pertinent to note that online learning success relies on digital access and efficiency.

The environment for online learning differs from the traditional classroom in terms of learner motivation and satisfaction as well as the interaction between the learner and instructor (Bignoux & Sund, Citation2018). Traditional classroom activities can engage students in learning, practice their communication skills, and assist them in learning by doing (Huang & Hu, Citation2015). However, an online class will be similarly effective as a face-to-face mode when it is designed properly (Ni, Citation2015). Online learning presents numerous technological benefits and leads to reduced resource usage compared with traditional physical classes (Li et al., Citation2023). For example, the use of Google Classroom helps improve students’ abilities, skills, and independent learning through its ease of use in their learning process during the COVID-19 pandemic (Oktaria & Rahmayadevi, Citation2021).

Nevertheless, the main concern lies not only in the learning quality in the form of how well the content is created and implemented but also in how the content is presented on an online platform and understanding and addressing the restraints faced by students. One year after implementing online schools in Indonesia, the pandemic persisted, and Indonesian students were still experiencing online learning. This situation was challenging for students, teachers, and even parents at that time. The experience of online learning varies depending on three aspects: teachers’ Internet and teaching skills, funding support for the school, and the socioeconomic condition of parents, including supporting facilities such as Internet access (Alifia et al., Citation2020).

The government has also addressed the problems raised by the implementation of online schools. Both the Ministry of Religious Affairs and the Ministry of Education and Culture supported teachers with online learning platform training and other kinds of support needed by teachers to ease their jobs. The Ministry of Education also simplified the curriculum to adapt to the emergency and provided free Internet quotas for online schools by partnering with telecommunication operators. They also launched free access to some online learning platforms and broadcast an educational TV program called Belajar dari Rumah (Study from Home). The last program was provided, especially for students without Internet access (Gupta & Khairina, Citation2020).

However, these policies may not have been sufficient to meet the ideal conditions for this study. Evaluation is needed to understand what is currently happening in the educational system during the pandemic. In contrast to previous studies that rely on teachers’ perspectives in online education (Gupta et al., Citation2022; Kumar et al., Citation2022), this study focuses on students as the object of the education system. Thus, understanding their perspectives on the pandemic situation is essential for analysis. This study remains relevant because online education in Indonesia has never been implemented on a large scale, and this practice is like a huge social experiment.

Studies in different countries have shown that the implementation of online learning generates both negative and positive effects for students. The negative impacts included psychological impact; for instance, the students were easily stressed (Chakraborty et al., Citation2021), bored, experienced mood changes as there were too many ineffective assignments (Irawan et al., Citation2020), and were anxious due to the pandemic situation (Adedoyin & Soykan, Citation2020) or regularly buying expensive quotas for poor students (Irawan et al., Citation2020). Remote teaching and online education seem ineffective, as they do not adequately meet the specific requirements of rural students (Mhandu et al., Citation2021). However, there were also some positive impacts, such as flexibility in time and location (Dhawan, Citation2020), decreased number of class dropouts (Baber, Citation2020), and increased comfort and accessibility for students (Mukhtar et al., Citation2020).

Previous research on online learning has mostly used online surveys with respondents (Akhter et al., Citation2022). Hence, social media analysis of student perspectives could fill this gap in the methodology. Social media analysis has become a way to analyze what people think about certain issues in a particular location and limited time (Neri et al., Citation2012). Since the rise of the Internet era, social media analysis has been used in many studies to understand people’s perceptions, feelings, and opinions that have already been communicated through the Internet (Balaji et al., Citation2017).

One of the most common analyses for social media is sentiment analysis at the word level by identifying the positive or negative words that came up from the retrieved data. The other key analysis is location analysis, which can categorize the users’ location and explain the possible spatial issues from the users’ opinions. This study aimed to analyze Indonesian students’ perceptions of online schools using social media data, specifically Twitter data. Using Twitter for sentiment analysis is more effective than Facebook and Instagram because Twitter’s platform is primarily text-based and features public posts that are easily accessible, providing a rich and straightforward dataset for analysis. Additionally, Twitter’s real-time nature makes it efficient to track trends and public opinions. As of 2022, this social media platform has 18.5 million users in Indonesia, equivalent to 6.6% of the total population (Kemp, Citation2022). Indonesia was noted as an early adopter of this social media platform and has become one of the most active users (Carley et al., Citation2015).

The data from this social media platform are unique. Balahur (Citation2013) described it as the character length of a tweet being only 140 characters; hence, it was difficult to insert all the important information in one tweet. There was also an issue with linguistic errors such as grammatical structure, misspellings, and abbreviations. Moreover, tweets are more likely to be informal. Thus, it contains specific slang and emoticons. There are also bots on this social media platform and automatic robot accounts run with computer scripts that spam users (Thomas et al., Citation2013). Therefore, it is crucial to clean tweets to obtain a valid dataset. Given that this social media platform provides a means of obtaining large numbers of temporal, network, linguistic, and other types of data from human behavior, particularly with little effort, it has become increasingly familiar to social science researchers, particularly in Indonesia (Santoso, Citation2021; Sari et al., Citation2022).

There are some other challenges in using social media analysis in the research (Social Media Research Group, Citation2016). First, social media users may not be representative of the entire population. This social media platform is considered not representative of any population because it is potentially biased toward affluent and urban populations (Hecht & Stephens, Citation2014). The user demographics of this social media platform vary globally, which influences their ability to draw clear conclusions (Cohen & Ruths, Citation2021). However, because Indonesia has a high number of social media users, social media analysis in Indonesia might still be relevant in representing the population. There were 170 million active social media users on any platform in Indonesia or 61.8% of the population in the January 2021 report. Regarding the number of active social media users, 12.5% of users were 13–17 years old or school-age children (Kemp, Citation2021). This aligns with the rule of this social media platform, which limits users to those aged 13 and above.

Second, several people may exhibit different behaviors in online media and reality. Hence, it was difficult to guess whether the content provided on social media was honest since the respondents might have changed their behavior. On the other hand, the students were not under pressure to tell the truth about their perception of the online school in the social media analysis. They were deliberate in saying anything in the social media world. The case was different if the students were interviewed because they might not be comfortable telling the truth in front of the interviewer.

Finally, the findings of this study are pivotal for educational institutions for several reasons. The shift to online learning has been swift because of the unanticipated lockdown to deal with COVID-19, and the schools did not have sufficient time to plan and adjust the course materials for online learning. This study examines the learning experience of Indonesian students in the online mode. Even after there is no longer a lockdown like the current situation, the post-pandemic situation will be different from before, and online learning remains to be combined with the traditional offline classroom. Thus, educational institutions need to adjust course materials and delivery to e-learning platforms to improve students’ experience in online learning.

Data and methodology

Data

The data were imported by Netlytic software, which can assist everyone in the analysis of cloud-based text and social networks from online conversations (Meneses, Citation2019). Netlytic was used for social media analysis and cloud storage. Some studies have used Netlytic to analyze social media for various issues, such as health (Santarossa et al., Citation2018), politics (Gruzd et al., Citation2016), and psychology (Santarossa et al., Citation2017). Netlytic provided the Ethical Decision-Making and Internet Research Recommendations by the Association of Internet Researchers and declared their support for using social media data ethically to carry out public interest research.

Netlytic could provide some combinations or even omitted keywords to be more relevant. In this study, the Search Query used is ‘sekolah’ and ‘dari rumah’ or ‘online’ or ‘daring’ lang:id. The search query means that the keyword ‘sekolah’ translated as ‘school’ combined with the words ‘dari rumah’ translated as ‘from home’ or combined the keyword ‘school’ with the word ‘online’ or ‘daring’ in the Indonesian language. The item ‘lang:id’ means that only tweets in Indonesian were collected for the analysis.

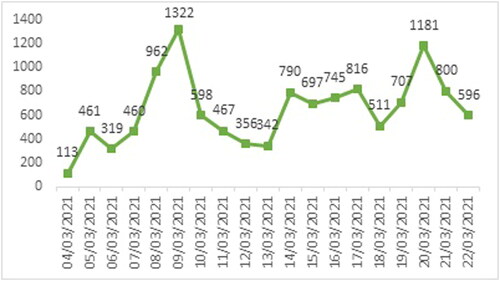

Based on the search query, there were 12.243 tweets were collected from the Netlytic software from 1st to 31st March 2021. The duration was selected because the government addressed the first case of the coronavirus in Indonesia in March 2020, followed by the study, work, and pray-from-home recommendation after the announcement. Therefore, March 2021 was the year after all Indonesian students were advised to study from home. This is also the period when the positivity rate in Indonesia reached a peak of about 35%, yet started to decline thereafter (Indrawati et al., Citation2022). shows the number of tweets created from 1st to 31st March 2021 with the search query mentioned above. There were no tweets about ‘online school’ from 1st to 3rd March 2021 and 23rd to 31st March 2021. Meanwhile, we found tweets about ‘online school’ every day from 4th to 22nd March 2021.

The average number of tweets per day is 644, with a median of 598. It started with 113 tweets on 4th March 2021, which was the lowest number of tweets during the period. The number of tweets peaked on 9th March 2021, at 1,322 tweets per day. At that time, there were two tweets about ‘online schools’ that went viral. The first tweet concerned the missing student, which was irrelevant to our analysis. The other was a tweet about ‘For those of you who are currently studying in an online class, you certainly want to go to school’. The tweets were retweeted 549 times a day.

Methodology

The first analysis used in this study was location analysis. Netlytic has already provided users’ location data based on the location description provided by the poster in their profile. Therefore, the name of the location may differ based on what is shown by the users. Some locations represent the country, island, province, city, or even a certain region in the city. To compare the analysis at the same level, the location analysis is equalized at the city/regency level based on the information already provided by the users. Since it is not possible to identify the education levels of the users who tweeted, this study did not consider any specific level to analyse the tweets.

In text analysis, opinions can be measured at different levels, such as words, phrases, sentences, paragraphs, and documents (Neri et al., Citation2012). This study applied word-level sentiment analysis by checking the list of the most frequent words used in the collected tweets. Adjectives that indicated something good were considered positive sentiments in the analysis. On the other hand, other adjectives were determined as negative sentiments if the meaning was bad.

However, because the word-level sentiment analysis could be biased in terms of subjectivity, which led to a different meaning, it was important to check the original tweets successively to determine the actual sentiment of the tweets. Checking the frequent words in the original tweets also enabled us to find some words that seemed unrelated to the analysis but had strong meanings about the perception when the words were combined with other words. Examples of this analysis are further described in the Results section.

The analysis also excluded words that appeared frequently but only in viral tweets that were not relevant. For example, the word ‘hilang’ which means ‘lost’, appears 555 times. The word could be interpreted as students feeling lost during online school. However, the original viral tweets about the missing students were irrelevant to the analysis.

Result and discussion

User location

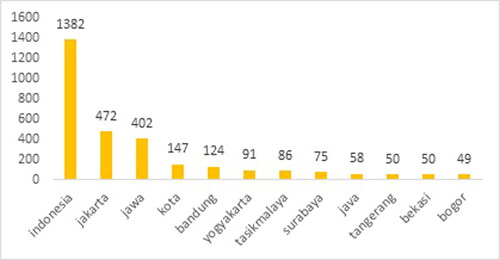

As the analysis focused on Indonesia, 1,382 users showed Indonesia as their location in the profile. The number was followed by Jakarta as the capital city of the country with 472 users, Jawa (Java) with 402 users, kota (city) with 147 users, and Bandung with 124 users. The results showed that the majority of Internet and users of this social media platform in Indonesia were concentrated on Java Island, specifically Jakarta and other urban areas in Java, while the internet is likely unavailable in the rural areas. The internet penetration is still highly centralised in the Java Island since the island contained 60% of population and dominated by the urban areas (Situmorang et al., Citation2023). Social media users are concentrated in these areas because they relatively have better technology and reliable electricity. Other parts of Indonesia struggle with poor technology and frequent power outages, limiting social media use.

This fact was supported by the top ten user locations from the collected tweets. provides this evidence. Jakarta, Bandung, Yogyakarta, Tasikmalaya, Surabaya, Tangerang, Bekasi, and Bogor were all big cities on the Java Islands. The other users even mentioned Java or Java as their living place in the bio, while 147 users mentioned kota (city). The results showed that Internet penetration in Indonesia still developed in urban areas.

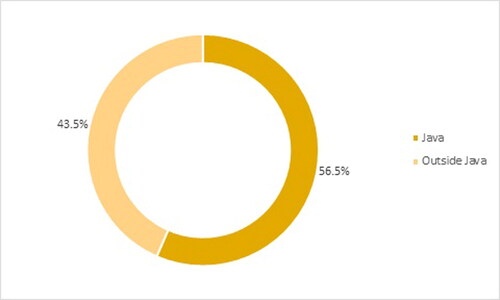

Inequality in Internet access is also shown in . From the location description, we categorized the cities mentioned on the profile as cities on Java Island or outside Java Island. 56.5% of users were located in a city on Java Island. The other 43.5% of users are in a city outside Java Island, including other large islands in Indonesia, such as Sumatra, Borneo, Sulawesi, and Bali.

Sentiment analysis

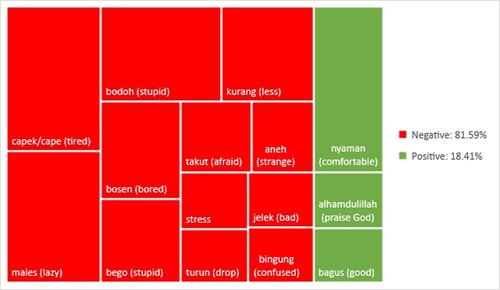

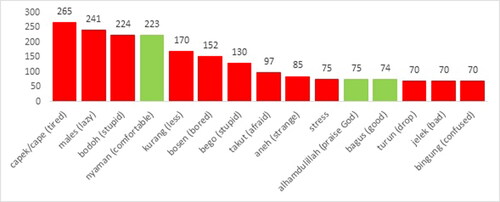

From the data, we found that students had a tough time in online school. In the word-level sentiment analysis, there were 1,649 words considered negative words or 81.59% of the total words containing sentimental tendencies. The remaining 372 words were considered positive words, or only 18.41% of the total words that contained sentimental tendencies. This finding is similar to two studies in Aceh, northwestern Indonesia, using a questionnaire that revealed negative attitudes of students toward online learning during the pandemic (Azhari & Kurniawati, Citation2020; Syahputri et al., Citation2020). Their studies showed that students felt fatigued, experienced physical pain, had poor time management, were isolated from their classmates, and missed the lecturer’s explanation during the online sessions. and summarize both the negative and positive words that emerged from the data.

The figure showed that negative words, such as ‘capek’ or ‘cape’, ‘males’, ‘bodoh’, ‘kurang’, and ‘bosen’ dominated the tweets about an online school. The number respectively appeared 265, 241, 224, 170, and 152 times from the collected data, followed by other negative words such as ‘bego’, ‘takut’, ‘aneh’, ‘stress’, ‘turun’, ‘jelek’, and ‘bingung’. On the other hand, only three positive words appeared, which were ‘nyaman’ which appeared 223 times, ‘alhamdulillah’ which appeared 75 times, dan ‘bagus’ which appeared 74 times. shows the frequency of each word with a sentimental tendency appearing in the collected tweets.

shows the English translation of the words that appear in since our analysis used Indonesian words. Students were ‘lazy’, ‘tired’, ‘bored’, ‘dumb’, ‘afraid’, ‘strange’, ‘stressed’, and ‘confused’ by their condition during the online school. They also felt ‘stupid’ and ‘less’ less’ during difficult times for studying. The tweets also contain words like ‘drop’ and ‘bad’ which are related to their score during online school if we read the tweets thoroughly. This finding supports the evidence that senior high school students face difficulties in the form of lacking motivation, poor Internet signals, being easily distracted, and experiencing more stress because of numerous assignments from teachers (Yuzulia, Citation2021).

Table 1. The English translation for the words appeared on the sentiment analysis.

However, there were also some positive words, although the number was less than that of the negative ones. Some students had already found that they were ‘comfortable’ with the online school. They also ‘thanked God’ for their condition during the online school, especially for having ‘good’ scores in these unusual circumstances. This positive aspect of online learning is probably due to greater confidence in students participating in online discussions rather than face-to-face interactions (Yuzulia, Citation2021). Students also experience positive attitudes toward using online learning platforms because of the flexibility they offer (Sakinah & Darmawan, Citation2022). It has been found that students who have a higher satisfaction level with online learning also perform better in academic performance (Djuwandi et al., Citation2022).

Despite some words with clear meanings, like what has been mentioned above, four other words came up frequently, but the meaning of those words could have been different if they were combined with the other words. After collecting the most frequent words that appeared in the collected tweets, the author also checked on the original tweets about those words and found that words like ‘tugas’, ‘enak’, ‘putus’, and ‘ngerti’ were interesting to be analyzed.

For example, in , the most frequent word came up with the word ‘tugas’ which means ‘task’ was ‘banyak’ or ‘many’ in English. The combination of these words means that many tasks should have been done by the students during online school, and they felt upset about it. The positive words such as ‘enak’ and ‘ngerti’ which means ‘good’ and ‘understand’ in English were contradictive with the actual meaning because the original tweets showed that those words frequently came up with the words ‘ga’, ‘ga’, or ‘ngga’ which had one meaning in English ‘not’. Hence, most students did not find that online school was good, and they hardly understood the subject during online school.

Table 2. Four other most frequently occurring words with an interesting combination.

The other word ‘putus’ (‘broken/down’) was more interesting with its frequent combination of ‘sekolah’ which means ‘school’ and the ‘internet’. The phrase ‘putus sekolah’ means that some students had to drop out of school due to the impact of the pandemic and online school. The reason why some students dropped out of school was probably explained by the phrase ‘internet putus’ which means that some students faced difficulty accessing the internet during online school. A similar situation was experienced by students in India, and technological constraints became a challenge in the implementation of online classes (Muthuprasad et al., Citation2021). Internet access is sometimes unstable or even broken in the middle of online school. This condition caused them to gain worse scores in school, fail to upgrade to a higher level, or even drop out. It is estimated that the dropout rate in primary schools in Indonesia has increased by 36.4% due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Halid, Citation2022).

The study highlights major challenges in education policies related to readiness, student motivation, internet access, and continuing education during emergencies. Negative sentiments show students struggling with online learning due to fatigue, isolation, poor time management, and physical discomfort. Similar issues were found in a previous study in Aceh, Indonesia (Azhari & Kurniawati, Citation2020; Syahputri et al., Citation2020). Key negative words indicate lower motivation and increased mental strain among students, with internet connectivity problems worsening the situation and causing higher dropout rates. Based on these findings, policymakers and researchers should further analyse the students’ perception of any change in the educational system; for instance, in the curriculum or infrastructure since their perceptions would reflect the result of a policy. Hence, understanding their feelings is as essential as evaluating their final score.

This also highlights the need for strong technological infrastructure and support systems for uninterrupted education. Despite these challenges, some students appreciated the flexibility and comfort of online learning, suggesting it could be improved to boost engagement. The study underscores the importance of enhancing digital readiness in the students’ curriculum, providing reliable internet distribution, and fostering motivational strategies to support education and student well-being during emergencies provided by related policymakers.

Conclusion

With efforts to curb the transmission of coronavirus, educational institutions must deal with online learning as the key approach to instruction. Schools shifted to online platforms to keep up with the curriculum during the COVID-19 pandemic. Using social media analysis, this study attempted to identify the readiness and perceptions of students coping with online learning. Thus, it is important to understand their experiences with online learning to run the class more effectively. In Indonesia, improvement of Internet penetration is essential to ensure the effectiveness of online learning. User location analysis could indicate how the distance learning policy was not suitable for every student, especially for those who live in remote areas without Internet access.

Our sentiment analysis revealed that students did not experience good things in an online school. Some of them might enjoy online school, but most of the students felt that it had a negative impact on them. The impact of their bad perceptions of online schools could lead to students dropping out of school because they did not find the benefits of school. As can be seen in the current situation, there is a continued increase in the use of online learning for student activities, complementing the traditional classroom although the COVID-19 pandemic has already settled down. Furthermore, online learning should be designed, executed, and evaluated to achieve learning objectives and minimize the problems faced by students.

Authors contributions

KS: conception and design; analysis and interpretation of the data; drafting of the paper. RBH: revising article critically for intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data and materials are available upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kanetasya Sabilla

Kanetasya Sabilla is a researcher at the Directorate for Economy, Employment, and Regional Development Policy, National Research and Innovation Agency of Indonesia. She was graduated from Master of Science in International Development from The University of Manchester. Her previous publications discussed about the regional development, environment, and macroeconomics.

Romi Bhakti Hartarto

Romi Bhakti Hartarto is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Economics, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta. He obtained his Doctoral in Economics from Heriot-Watt University where he served as an Associate Fellow. His research area focuses on family economics and child welfare.

Notes

1 Statistics Indonesia (2020). Potret Pendidikan Indonesia: Statistik Pendidikan 2020.

References

- Adedoyin, O. B., & Soykan, E. (2020). Covid-19 pandemic and online learning: The challenges and opportunities. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1813180

- Akhter, S., Robbins, M., Curtis, P., Hinshaw, B., & Wells, E. M. (2022). Online survey of university students’ perception, awareness and adherence to COVID‑19 prevention measures. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 964. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13356-w

- Alifia, U., Barasa, A. R., Bima, L., Pramana, R. P., Revina, S., & Tresnatri, F. A. (2020). Belajar dari rumah: potret ketimpangan pembelajaran pada masa pandemi COVID-19. SMERU Research Institute.

- Arsendy, S., Gunawan, C., Rarasati, N., & Suryadarma, D. (2020). Teaching and Learning during School Closure: Lessons from Indonesia. ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute Perspective, 89

- Azhari, T Kurniawati. (2020). Students’ perception on online learning during the Covid-19 pandemic (A case study of Universitas Malikussaleh students). Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 495, 46–50.

- Baber, H. (2020). Determinants of students’ perceived learning outcome and satisfaction in online learning during the pandemic of COVID-19. Journal of Education and e-Learning Research, 7(3), 285–292. https://doi.org/10.20448/journal.509.2020.73.285.292

- Balahur, A. (2013). Sentiment analysis in social media texts. In Proceedings of the 4th Workshop on Computational Approaches to Subjectivity, Sentiment, and Social Media Analysis (pp. 120–128). Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Balaji, P., Nagaraju, O., & Haritha, D. (2017 Levels of sentiment analysis and its challenges: A literature review [Paper presentation]. 2017 International Conference on Big Data Analytics and Computational Intelligence (ICBDAC) (pp. 436–439). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICBDACI.2017.8070879

- Bignoux, S., & Sund, K. J. (2018). Tutoring executives online: What drives perceived quality? Behaviour & Information Technology, 37(7), 703–713. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2018.1474254

- Carley, K. M., Malik, M., Kowalchuk, M., Pfeffer, J., & Landwher, P. (2015). Twitter usage in Indonesia. CASOS Technical Report.

- Chakraborty, P., Mittal, P., Gupta, M. S., Yadav, S., & Arora, A. (2021). Opinion of students on online education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 3(3), 357–365.

- Cohen, R., & Ruths, D. (2021). Classifying political orientation on Twitter: It’s not easy! Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 7(1), 91–99. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v7i1.14434

- Dhawan, S. (2020). Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 49(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239520934018

- Djuwandi, J., Niang, A. A. S., & Gunadi, W. (2022). The impact of online learning on student satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. International Journal of Education Economics and Development, 13(2), 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEED.2022.121816

- Golberstein, E., Wen, H., & Miller, B. F. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(9), 819–820. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456

- Gruzd, A., Mai, P., & Kampen, A. (2016). A How-to for using netlytic to collect and analyze social media data: A case study of the use of Twitter during the 2014 Euromaidan revolution in Ukraine. In M. Steele. (ed.) The SAGE handbook of social media research methods. SAGE Publications.

- Gupta, D., & Khairina, N. N. (2020). COVID-19 and learning inequities in Indonesia: Four ways to bridge the gap. The World Bank.

- Gupta, K. P., Bhaskar, P., & Joshi, A. (2022). Prioritising barriers of online teaching during COVID-19 from teachers’ perspective: using the analytic hierarchy process. International Journal of Knowledge and Learning, 15(3), 203–232. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJKL.2022.123956

- Halid, I. S. (2022). Covid-19 pandemic and school dropout rates: Empirical evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Economics Research and Social Sciences, 6(2), 149–155. https://doi.org/10.18196/jerss.v6i2.15316

- Hecht, B., & Stephens, M. (2014). A tale of cities: Urban biases in volunteered geographic information. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 8(1), 197–205. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v8i1.14554

- Huang, X., & Hu, X. (2015). Teachers’ and students’ perceptions of classroom activities commonly used in English speaking classes. Higher Education Studies, 6(1), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v6n1p87

- Indrawati, S. M., Nazara, S., Anas, T., Ananda, C. F., & Verico, K. (2022). Keeping Indonesia safe from the Covid-19 pandemic: Lessons learnt from the national economic recovery programme. ISEAS Publishing.

- Irawan, A. W., Dwisona, D., & Lestari, M. (2020). Psychological impacts of students on online learning during the pandemic COVID-19. KONSELI: Jurnal Bimbingan dan Konseling (E-Journal), 7(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.24042/kons.v7i1.6389

- Kemp, S. (2021). Digital 2021: Global overview report. Data Reportal.

- Kemp, S. (2022). Digital 2022: Indonesia. Data Reportal.

- Kumar, P., Garg, R. K., Kumar, P., & Panwar, M. (2022). Teachers’ perceptions of student barriers to sustainable engagement in online education. International Journal of Knowledge and Learning, 15(4), 373–408. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJKL.2022.126273

- Li, Y., Doewes, R. I., Al-Abyadh, M. H. A., & Islam, M. M. (2023). How does remote education facilitate student performance? Appraising a sustainable learning perspective midst of COVID-19. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 36(3), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2022.2162561

- Magson, N. R., Freeman, J. Y., Rapee, R. M., Richardson, C. E., Oar, E. L., & Fardouly, J. (2021). Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(1), 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9

- Meneses, L. (2019). Netlytic. Early Modern Digital Review, 2(1), 352–357.

- Mhandu, J., Mahiya, I. T., & Muzvidziwa, E. (2021). The exclusionary character of remote teaching and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. An exploration of the challenges faced by rural-based University of KwaZulu Natal students. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1947568

- Mukhtar, K., Javed, K., Arooj, M., & Sethi, A. (2020). Advantages, limitations, and recommendations for online learning during COVID-19 pandemic era. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 36(COVID19-S4), S27–S31. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2785

- Muthuprasad, T., Aiswarya, S., Aditya, K. S., & Girish, K. J. (2021). Students’ perception and preference for online education in India during COVID-19 pandemic. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 3(1), 100101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100101

- Neri, F., Aliprandi, C., Capeci, F., Cuadros, M., & By, T. (2012). Sentiment analysis on social media [Paper presentation]. 2012 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining Sentiment (pp. 919–926).

- Ni, A. (2015). Comparing the effectiveness of classroom and online learning: Teaching research methods. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 19(2), 199–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2013.12001730

- Oktaria, A. A., & Rahmayadevi, L. (2021). Students’ perceptions of using Google classroom during the Covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Educational Management and Innovation, 2(2), 153–163. https://doi.org/10.12928/ijemi.v2i2.3439

- Sakinah, K., & Darmawan, A. (2022). Students’ perceptions of online learning during the Covid-19 pandemic. Jurnal Pendidikan Tambusai, 6(1), 1146–1153.

- Santarossa, S., Lacasse, J., Larocque, J., & Woodruff, SJ. (2018). Orthorexia on Instagram: A descriptive study exploring the online conversation and community using the Netlytic software. Eating and Weight Disorders: EWD, 24(2), 283–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0594-y

- Santarossa, S., Coyne, P., & Woodruff, S. J. (2017). Exploring #nofilter images when a filter has been used: Filtering the truth on Instagram through a mixed methods approach using Netlytic and photo analysis. International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking, 9(1), 54–63. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJVCSN.2017010104

- Santoso, D. H. (2021). New media and nationalism in Indonesia: An analysis of discursive nationalism in online news and social media after the 2019 Indonesian presidential election. Jurnal Komunikasi: Malaysian Journal of Communication, 37(2), 289–304.

- Sari, D. K., Kumorotomo, W., & Kurnia, N. (2022). Delivery structure of nationalism message on Twitter in the context of Indonesian netizens. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 12(1), 173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-022-01006-3

- Situmorang, A. C., Suryanegara, M., Gunawan, D., & Juwono, F. H. (2023). Proposal of the Indonesian framework for telecommunications infrastructure based on network and socioeconomic indicators. Informatics, 10(2), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics10020044

- Social Media Research Group. (2016). Using social media for social research: An introduction. Government Social Research - Social Science in Government.

- Syahputri, V. N., Rahma, E. A., Setiyana, R., Diana, S., & Parlindungan, F. (2020). Online learning drawbacks during the Covid-19 pandemic: A psychological perspective. EnJourMe (English Journal of Merdeka): Culture, Language, and Teaching of English, 5(2), 108–116. https://doi.org/10.26905/enjourme.v5i2.5005

- Thomas, K., McCoy, D., Grier, C., Kolcz, A., & Paxson, V. (2013). Trafficking fraudulent accounts: The role of the underground market in Twitter spam and abuse [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the 22Nd USENIX Conference on Security (pp. 195–210).

- Yuzulia, I. (2021). The challenges of online learning during pandemic: Students’ voice. Wanastra: Jurnal Bahasa Dan Sastra, 13(1), 08–12. https://doi.org/10.31294/w.v13i1.9759