Abstract

The use of social media for activism has become a growing trend in Ghana and Africa. Although there have been several studies on how social media is used for activism to address socio-political issues, most of these studies have focused on using platforms such as Twitter and Facebook. In contrast, video-based platforms such as YouTube have received less attention from researchers. Employing framing theory and content analysis of comments on some selected YouTube videos about Kamala Harris’ statements on promoting LGBTI + rights in Ghana, the study shows that Ghanaian audiences engaged with the content to express their resistance to the promotion of this agenda. The findings revealed that three main issues surrounding her statements attracted the most audiences’ attention, who used the YouTube comment section to express their resistance. The issues included: 1) the promotion of LGBTI + rights in Ghana, as suggested by Kamala Harris; 2) the response of the President of Ghana to the country’s position on the matter; and 3) the colorful light display on the Jubilee House. This article has implications for scholarship on gender and sexuality studies and the discourse on online activism.

1. Introduction

On March 26th, 2023, US Vice President (VP) Kamala Harris arrived in Ghana as part of her weeklong tour to three countries in Africa: Ghana, Tanzania, and Zambia. An initiative aimed at repositioning the US as a valuable partner of the African continent under the Biden-Harris administration. Ghana was the first country to host the US VP on her African tour. On Monday, March 27th, 2023, she met with the President of the Republic of Ghana at a joint press meeting, at which the issue of the rights of people who identified as LGBTI + in Ghana was raised. As part of her response to the issue, the US VP indicated that she felt very strongly about supporting the rights of people who identified as LGBTI + in Africa, an issue which according to her is ‘a human right issue that will not change.’ Her comment, which came at a time when an anti-LGBTI + bill was before the parliament of Ghana, received massive backlash with the Speaker of Ghana’s parliament coming out to call her comments undemocratic. Citizens of the country also used various social media platforms, including YouTube, to express their sentiments on the matter as a form of activism and civic engagement on the issue.

According to Worldometer (Citation2024), Ghana has a population of over 34 million as at May 2024. Out of this population, about 8.8 million people use social media (Sasu, Citation2024). Thus, out of every 4 people in Ghana, 1 person uses social media. This number is expected to increase in the coming years. WhatsApp, Instagram, Facebook, and Snapchat are the most widely used social media platforms in Ghana, with the youth being the most active users of these platforms (Sasu, Citation2024). However, the use of social media for activism is a new trend in Ghana and Africa at large (Mateos & Erro, Citation2021; Nartey, Citation2022a; Nartey & Yu, Citation2023). The study of social media for activism in Ghana has also received attention from researchers (Brobbery et al., Citation2021; Nartey, Citation2022a; Nartey & Yu, Citation2023). Brobbery et al. (Citation2021) conducted a study on the #Fixthecountry movement, which was aimed at ensuring the accountability of successive governments in Ghana, and found that although the COVID-19 pandemic and government sanctions impacted the effectiveness of the offline version of the protest, social media afforded the protestants the opportunity to advance their course despite the continuous government interference with the protest. On this same issue, Nartey & Yu (Citation2023) identified three discursive strategies used by protesters to express their grievances on Twitter. These included the construction of the government of Ghana as insensitive, the identification of the Ghanaian public as suffering masses due to the failure of leaders, and the call to the government to listen to the cries of the protestants and act in response to their request. Nartey (Citation2022a) also studied the use of Twitter for the #Occupyflagstaffhouse and #Redfriday movements in Ghana and found that Twitter could be used as an effective platform to mobilize people for social action to put pressure on the government to respond to their needs. Ghanaians, like others, use social media as a platform for activism to address specific socio-political issues.

Although previous studies have shown that social media can be used as a platform for online activism to address social, economic, and political issues such as racism, gender, better governance, and corruption, such studies have focused extensively on platforms such as Twitter and Facebook (Brobbery et al., Citation2021; Hopton & Langer, Citation2022; Malik, Citation2022; Nartey, Citation2022a; Nartey & Yu, Citation2023). Studies on how video-based platforms, such as YouTube, are used for activism have received little attention. A significant gap in the literature is studies emanating from non-Western countries, like Ghana. Given this, the current paper analyzes users’ comments on YouTube videos about Kamala Harris’s comments on the promotion of LGBTI + rights in Ghana during her visit to Ghana as part of her 1-week tour of some African countries. This paper analyzes audiences’ comments on the videos as a form of activism against the promotion of LGBTI + rights in Ghana and shows how and why commentators express their resistance to this idea. At the end of the study, the following research questions will be answered: 1) What LGBTI + related issues surrounding Kamala Harris’ visit attracted the most audiences’ reactions on YouTube? 2) How do the audiences’ reactions on YouTube reflect audiences’ attitudes towards the promotion of LGBTI + rights in Ghana? The study is significant because it adds to the knowledge of gender and sexuality studies as it pertains to the Ghanaian context. It also adds to our understanding of the use of visual-based social media platforms as spaces for activism and civic engagement.

2. Literature review

2.1. Defining digital activism

To define digital activism, it is prudent to attempt to explain what activism is in itself. Chon and Park (2019. pp.73) define activism from the perspective of public relations as ‘the process whereby groups of people exert pressure on organizations and institutions to change policies, practices and conditions they activists consider problematic’. However, from a sociological perspective, they defined the concept as ‘a series of contentious performances by which ordinary people try to change social issues through collective action’ (pp.74). Thus, activism has come to be associated with collective action on controversial issues that affect the populace. With the advent of digital technologies, ‘collective action’ which has come to be associated with activism has given way to ‘connective action’- ‘contentious political action in the digital age’ (George & Leidner, Citation2019, pp. 4). Thus, today people use digital tools to engage in activist activities such as protests, petitions and fundraising among others. Several scholars have since studied this developing phenomenon in activism and have attempted to define digital activism. For instance, Ozkula (Citation2021) define digital activism as a form of political activism that occur on the internet and the political movements that rely on these activities. Kaun & Uldam (Citation2018) also define digital activism based on previous studies in the field as the use of mobile and fixed devices with access to the Internet to engage in hacktivism, hashtag activism and open forms of advocacy. Karatzogianni (Citation2015) also defined digital activism as political participation and protests that occur in digital networks. She identified four waves of digital activism beginning from 1994 with the Zapatista movement and anti-globalization movement to the mainstream digital activism in the form of Wikileaks and Snowden between 2010-2013. However, today, the use of social media for digital activism seems to be the trend in many countries. In this vein, George & Leidner, (Citation2019) identified three levels of digital activism. These include 1) digital spectator activities such as clicktivism, meta voicing and assertion, 2) digital transitional activities such as political consumerism, digital petitions, botivism, and e-funding and, 3) digital gladiatorial activities such as data activism, exposure, and hacktivism

2.2. Social media for political activism

Social media for activism can be defined as a form of communicative action on social media aimed at collectively addressing a problem (Chon and Park, 2020). The power of social media for protest movements has been felt across the globe in campaigns such as #Blacklivesmatter in the USA, #Mashaamini in Iran, #EndSARSNow in Nigeria, and, #FeesMustFall (FMF) in South Africa with Twitter being the most used platform in most of these protests. Research on the use of social media for activism has received a lot of attention in communication studies, with previous works focusing on issues such as racism, homophobia, xenophobia, and better governance among others (Nartey & Yu, Citation2023). While most studies in the West have focused extensively on issues such as racism, gender equality, and feminism (Hopton and Langer; 2021; Jun et al., Citation2024; Turley & Fisher, Citation2018; Tao et al., Citation2022), studies in other parts of the world, particularly Africa, have focused on socio-political issues such as political accountability and good governance (Kofi Frimpong et al., Citation2022; Mateos & Erro, Citation2021; Nartey, Citation2022a).

With the advent of new digital technologies, there are now new communicative spaces to discuss and deliberate issues that concern social, economic, and political stability. For instance, Chon & Park (Citation2020) investigated how social media was used to discuss contentious issues in the US, such as gun ownership, immigration, and police use of power, and suggested that active communicative behaviors aimed at collectively solving a problem move people to participate in collective action on an issue. Twitter has been instrumental in the issue of racism and police brutality. Jun et al., (Citation2024) and Tao et al. (Citation2022) showed how social media can be used to address racial issues by investigating how Asian Americans took up social media activism to deal with the problem of discrimination and hate crimes against Asian Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic. De Choudhury et al. (Citation2016) also argued that participation in protests is closely associated with the intensity of social media conversations surrounding an issue, as was seen in the case of the #Blacklivesmatter movement. According to them, protestants used social media to address the serious social issue of racism in America and mobilize support for the campaign to bring about change.

However, the situation in Africa seems quite different from most studies that focus on the use of social media for political activism. For instance, a study by Mateos & Erro (Citation2021) argues that sub-Saharan Africa has in recent years seen a wave of social and political protests with a growing trend in online protests. Focusing on Senegal, Burkina Faso, and Congo, their study concluded that the recent trend has given birth to a third wave in African protests. Kofi Frimpong et al. (Citation2022) also conducted a study to investigate the relationship between online political activism and voting patterns in an African context and found a strong positive relationship between social media activism and voter voting patterns. Nartey (Citation2022a), on the other hand, showed how social media particularly, Twitter is used by Ghanaian activists to put pressure on government to respond to serious socioeconomic issues that affect citizens. In South Africa, Bosch et al. (Citation2018) also found that social media particularly Twitter is used by activities alongside traditional media to raise awareness about their course and communicate with journalists to get mainstream media coverage for their activities. For instance, in the case of the Fees Must Fall protest in South Africa, Bosch & Mutsvairo (Citation2017) found that the student protestors used images to create narratives centered on feminism and race to expose broader underlying issues of inequality in South Africa. These images were often not captured by the mainstream media. The situation in Nigeria was not so different Akerele-Popoola et al. (Citation2022) also investigated the use of Twitter in the End SARS protests in Nigeria and found that Twitter was an effective tool for organizing the protest as it enabled users to form ties during and after the protest to drive social change. They, therefore, conclude that Twitter can be a very powerful tool to enhance or degrade democracy depending on how it is used. These studies show that users of social media platforms in Africa are actively involved in online activism, just as their Western counterparts, although the African situation is dynamic and unique to its sociopolitical context.

2.3. Social media for gender and sexuality activism

Social media has also been used to address issues related to gender-based violence, sexuality, and LGBTI + rights. Turley & Fisher (Citation2018) argue that social media offers a platform for feminists to address issues relating to sexism and misogyny using ‘shouting back against hegemony.’ According to Portwood-Stacer & Berridge (Citation2014) online spaces have proven to be fetile grounds for the growth of feminist communities and activism as many popular blogs and social media apps emerge. On this note Mao (Citation2020) studied how social media users in China took advantage of a social media post on developing a TV play idea that celebrates the valor of 4 single professional women and found that although feminist activism in China is highly censored, the social media post created opportunities for grassroot feminist to put a resistance against recent stereotypical and insulting representation of women in the Chinese Media. Hopton & Langer (Citation2022) also argued that online communities can be havens for the manosphere who often use platforms such as Twitter to advance their misogynist agendas by portraying men as victims and feminists as monstrous to undermine feminist agendas. Regarding gender-based violence, Malik (Citation2022) also conducted a study to investigate how platforms such as Facebook are used to draw attention to women’s rights and violence against women within the Ghanaian context. Through an interview with seven activists, the study found that Facebook offers a platform for victims of gender-based violence to tell their stories and draw attention to their problems and for activists to network and share ideas on how to help victims. Jenzen (Citation2015) also found that social media provides a space for sexual politics, with platforms such as YouTube and Tumblr being preferred mostly by people who identify as LGBTI + to create awareness about issues surrounding their culture due to the platform allowance for user creativity. However, Barnes (Citation2022), who studied how pro-LGBTI + groups used social media to promote their agenda in a conservative culture like Mexico, found that pro-LGBTI + groups often do not take full advantage of social media to create awareness of issues affecting themselves.

2.4. The case of YouTube

Although there have been several studies on the use of social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook for activism, studies on the use of YouTube for activism have been limited and varied in methodology. Some studies, however, have focused on the use of YouTube videos as activist videos in response to specific socioeconomic or political issues. For instance, Kellner & Kim (Citation2010) argue that YouTube should be taken advantage of by critical pedagogy practitioners to create an alternative Internet culture that promotes human agency, grassroots democracy, and sociopolitical reconstructions. Regarding the use of YouTube in political activism, Uldam & Askanius (Citation2013) also found that YouTube can function as a communicative space for advancing activist movements and investigated how commenting on activist videos can help promote civic cultures in ways that allow for inclusive political debates. Rospitasari (Citation2021) also argues that a glimmer of hope appears for a minority group to use video activism in the form of documentary films to express their social concerns and fight against the dominant discourses. As seen from the above studies, YouTube, as a social media platform, is often used by activists to promote their agenda. With regard to LGBTI + activism, a few studies have been conducted in this regard that shows the potential for YouTube as a platform for activism for people who identify as LGBTI+. For instance, Tortajada et al. (Citation2021) conducted a study on how tans Youtubers are transitioning from using YouTube to promote videos on the trans body to what it means to be trans in itself. Using Elsa Ruiz Cómica’s videos as a case study, their study found that Elsa shares her personal experiences on YouTube on what it means to be trans as a way of fighting against the labelling of people who do not conform to the gender assigned to them at birth as people ‘patients with gender identity disorder’.

The choice of YouTube for analysis in this study holds significance not only within academic research but also in the Ghanaian society. YouTube’s prominence, coupled with its practice of compensating content creators, underscores its relevance. Moreover, the platform fosters a space for comprehensive insights, thanks to its diverse user base. Unlike platforms like Twitter with character constraints, YouTube enables users to express detailed responses, aligning with the research’s need for thorough comments. This richness in engagement and depth of discussion sets YouTube comments apart, making them ideal for analysis in this study. However, studies on the use of YouTube for LGBTI + activism and otherwise are limited, especially in the African context. The current study aims to fill this gap by exploring how YouTube is used in Ghana as a communicative space for civic engagement and activism especially as it pertains to the promotion of LGBTI + rights in Ghana.

2.5. Framing theory

This study is informed by framing theory, as postulated by Goffman (Citation1974). Framing is a concept closely related to the agenda-setting power of the media, which emphasizes the media’s power to influence what issues people consider important. However, diverging from traditional agenda-setting theory, framing theory not only explains how the media presents certain issues as more important than others but also how the media places these issues within a specific context of meaning. As Entman (Citation1993, pp. 52) posits, ‘to frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation and/or treatment for the item described’. Framing theory argues that how certain information is presented to an audience influences how the audiences processes the information. Framing theory is widely used in media studies to investigate how media selection and the interpretation of news items influence audiences’ comprehension of specific issues. It is an approach to analyzing news discourse, which mainly deals with how public discourse about public policy issues is constructed and negotiated (Pan & Kosicki, Citation1993). D’Angelo (Citation2019) found that research on framing analysis has looked at framing from cognitive and constructionist views and argued that constructionist views on framing place more emphasis on how audiences use media frames to construct their meanings on an issue instead of simply accepting media frames as reality. In this study, framing theory was employed to identify the frames within which the media presented Kamala Harris’ statement on promoting LGBTI + rights in Ghana and how these media frames influenced audiences’ comprehension of the issue and subsequent reactions to the issue. Framing analysis is also used to investigate how audiences present their viewpoints on the issue in harmony with the media frames they are presented with.

3. Methodology

The study employed non-reactive online observations and a content analysis of audiences’ comments. Non-reactive observations allow researchers to study the behavior of people in a setting without making them aware that they are being studied. This approach allows people to behave more naturally as they are being studied (Neuman, Citation2012). Denscombe (Citation2010) argues that content analysis can be used with any text, whether it is in the form of writing, sounds, or pictures, and can be used to quantify any text. Given the nature of the study, content analysis was considered the best approach because it provides an easy and efficient way of quantifying a text through word or phrase counts. However, content analysis goes beyond simple word counts. This could be an effective and rigorous approach to unpacking the hidden issues that underlie a given text (Matthews & Ross, Citation2010). Thus, this study employs both qualitative and quantitative content analysis techniques to analyze the comments of a YouTube video on Kamala Harris and the LGBTI + issue in Ghana.

A purposive sampling technique was used to sample the videos for this study. Etikan & Bala (Citation2017) posited that purposive sampling, which is based on a researcher’s judgment, helps the researcher select samples that will provide the best information to achieve the objectives of a study. To collect data, a quick YouTube search using the keywords ‘Kamala Harris in Ghana and LGBTI + Issues’ was conducted to sample videos for the study.

The YouTube search yielded several results. However, the search was filtered by focusing only on videos posted by YouTube channels owned by Ghanaian media houses and targeted at Ghanaian audiences. This resulted in an eventual sample of only three videos. For anonymity, these channels will be referred to as ‘YC’ where ‘YC’ means YouTube Channel. Video 1 was posted by, YC 1 a television news agency in the capital, Accra. This channel has over 733k subscribers and their video had garnered about 12k views and about 121 comments at the time of the study. Video 2 was also posted by YC 2 another television news agency in Accra. This channel also has 636k subscribers had also garnered about 600k views and 1K comments at the time of the study. However, Video 3 which was posted by YC 3, was a private YouTube channel whose owner also operates in Accra. The channel also has about 630K subscribers had garnered about 96,000 views, with about 1200 comments at the time of the study. The figures on the viewership and comments associated with the selected videos under-scores the importance of the issue to the Ghanaian audiences.

We leveraged YouTube’s API to extract data from the selected videos. This involved initiating HTTP requests to YouTube’s servers, with the API key serving as authentication. The API provides endpoints for accessing various video data, including comments and views. Upon making the requests, the researchers parsed the JSON-formatted responses, containing the pertinent information. Due to the potentially vast number of comments, the API’s pagination feature was utilized to retrieve all comments. Subsequently, the researchers filtered out irrelevant comments and removed duplicates to prepare the data for analysis. 840 random comments were initially sampled. At the time of the study, the comments spanned from March 28th, 2023, to April 11th, 2023. The research focused on three videos, employing a random selection approach for quality control and manageable data analysis. This methodological decision aimed to ensure a rigorous analysis while avoiding potential redundancies and overwhelming data volumes. By prioritizing a subset of comments, the researchers could conduct a thorough and robust analysis, extracting meaningful insights without being bogged down by excessive data.

The data was further screened to eliminate comments that did not speak to the issue under investigation and from people who were identified as non-Ghanaians, leading to an eventual sample of 775 comments that were considered valid for the study. The data were then numbered YTC 1 to YTC 775, where YTC indicates YouTube comment. Given the objectives of the study, the collected data were analyzed for recurring themes. The themes were then quantified and categorized to identify the most dominant issues addressed in the audiences’ comments and how they presented their comments in response to the issues under discussion. We initially read through the data to familiarize the ourselves with the text. We then went into the texts to identify themes which were assigned unique codes such as, LJBH, PR, PLGBTI + where LJBH means ‘lighting of the Jubilee House’, PR means, ‘presidents’ response’ and PLGBTI + means ‘promoting LGBTI + rights in Ghana.’ We then assigned the individual comments to one of these codes based on their overt meanings. However, in a few cases, we assigned codes based on the perceived meaning of a comment in the absence of a clear dominant meaning. The codes were then quantified and categorized into themes and sub-themes, and presented in the form of tables and charts with paraphrased extracts from the text as support.

Given the nature of the study, a formal consent of all commentators could not be obtained before the research as this would have been impossible. This is because in this study, we attempt to bring to the fore, the general sentiments of Ghanaians on an issue that has serious sociopolitical implications for the freedom and liberties of people who identify as LGBTI+. Townsend & Wallace (Citation2016) argue that informed consent may not be acquired for studies that uses the critical approach in order to protect the identity of the researchers or lead to censorship of scientific research. However, to protect the identity of commentators on the YouTube videos sampled for the study, efforts were made to ensure that participants could not be traced in any way to their comments. Given this, participants’ comments used in the study are paraphrased instead of using direct quotations.

4. Findings and discussion

RQ1. What LGBTI + related issues surrounding Kamala Harris’ visit attracted the most audiences’ reactions on YouTube?

The study identified three major themes that attracted the most reactions among audiences. These issues include the promotion of LGBTI + rights in Ghana, the president of Ghana’s response to the issue of promoting LGBTI + rights in Ghana and the colorful light displays on the Jubilee House, the presidential seat of Ghana. summarizes the themes and sub-themes identified from the comments along with their frequencies and percentages.

Table 1. Themes from audiences’ comments on YouTube Video.

shows that the issue that attracted the most comments was the promotion of LGBTI + rights in Ghana, as Harris suggested. Of the 775 (100%) comments, 373 (48%) extensively discussed this issue. The second most widely deliberated issue among commentators was the colorful display on the Jubilee House, attracting 284 (37%) comments with commentators deliberating the possible meaning of this act by government officials. The president of Ghana’s response to promoting LGBTI + rights attracted about 118 (15%) comments among commentators. These figures are representative of the general situation in the comment section of all the YouTube videos sampled for the study.

4.1. Promotion of LGBTI + rights in Ghana

One of the overarching themes that attracted the most audiences’ reaction on the YouTube videos analyzed in this study was the promotion of LGBTI + rights in Ghana. This was based on Kamala Harris’ statement on the issue when she met the president of the Republic of Ghana on the second day of her visit to Ghana. As mentioned earlier, her statement on the US’s position on LGBTI + rights came during a period when there was an anti-LGBTI + bill before the parliament of Ghana. Thus, her statement received a substantial number of comments from audiences with most commentators rejecting the idea of promoting LGBTI + rights in Ghana (See ).

Table 2. Commentators’ responses on promoting LGBTI + rights in Ghana.

In , the discussion centers on the perspectives expressed in 373 comments regarding the promotion of LGBTI + rights in Ghana. The majority of commentators, constituting 48% (181 individuals), associated the promotion of LGBTI + rights with the imposition of Western values on Ghanaians. Another significant proportion, 27% (99 individuals), outrightly rejected the promotion of this agenda in Ghana. A smaller percentage, 2% (eight individuals), advocates for the acceptance of the rights of people who identify as LGBTI + in Ghana. Additionally, 15% (55 commentators) attributed the promotion of LGBTI + rights in Ghana to the failure of the country’s leaders, while the remaining 8% (30 individuals) linked Kamala Harris’s comments on promoting LGBTI + rights in Ghana to the conspiracy theories of a hidden Western hegemonic agenda.

also reveals distinct patterns in commentators’ responses to the promotion of LGBTI + rights in Ghana. Understanding the implications requires careful analysis. A substantial 48% of comments linked the promotion of LGBTI + rights to the imposition of Western values. The dominant narrative suggests resistance to perceived external influence, emphasizing the need for further investigation into cultural dynamics and influences shaping opinions. Resistance may stem from the desire to preserve traditional values and resist perceived cultural intrusion. These findings are consistent with those of Baisley (Citation2015) who found that in Ghana, pro-LGBTI + frames are usually counteracted by decolonization frames. A viewpoint supported by the assumption that homosexuality is largely alien to Ghana and Africa at large.

A notable 27% outright rejected the promotion of LGBTI + rights in Ghana. The rejection signifies a strong conservative sentiment among commentators who view the promotion of LGBTI + rights as a form of moral degradation. Thus, conservative values appear to dominate the discourse, influencing resistance to the promotion of LGBTI + rights in Ghana. These findings are also consistent with those of Nartey (Citation2022b) who found that among the many factors that lead to the resistance to LGBTI + rights in Ghana is the fear of moral decadence that may arise as a result of acceptance of LGBTI + rights.

Only 2% expressed support for the acceptance of LGBTI + rights. A minority in favor indicates a lack of vocal support, prompting the need to investigate the nuances of supportive perspectives. The absence of strong advocacy implies that those in favor of LGBTI + rights may not be vocal or may face challenges expressing their views in the given context. Our findings are consistent with those of Barnes (Citation2022), who argued that in most conservative cultures, people who identify with the LGBTI + community do not often take advantage of media platforms to promote their agenda or advocate for their course. A situation that may arise due to fear of persecution.

About 15% attributed the promotion of LGBTI + rights to leadership failure, and 8% associated it with conspiracy theories. The blame on leaders and the presence of conspiracy theories suggests a complex interplay of political and ideological factors, necessitating a deeper exploration. Commentators attribute the promotion of LGBTI + rights to leadership failures, indicating the need for effective governance to gain public trust. As revealed by the extracts, some commentators view the promotion of LGBTI + rights in Ghana as a psyop program. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines a psyop as a military operation aimed at influencing the enemy’s state of mind through non-combative means. The association of Kamala Harris’s comments with conspiracy theories (8%) underscores the impact of political figures on public perception. Political influence is a key factor, necessitating further investigation of the role of political discourse in shaping opinions on sensitive topics. Political discourse plays a pivotal role in shaping attitudes toward sensitive topics, warranting further exploration of the interplay between politics and public opinion.

4.2. Presidents’ response to promoting LGBTI + rights in Ghana

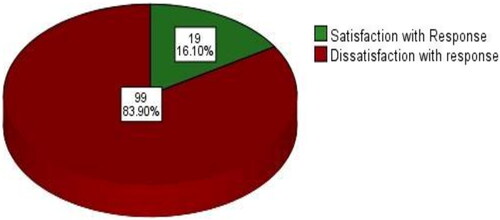

Another issue from the video that attracted the most audiences’ reaction and a discourse of contention among commentators was the response of the President of the Republic of Ghana to Kamala Harris’ Comment on promoting LGBTI + rights in Ghana. President Akuffo Addo, who was asked a question about the rights of people who identified as LGBTI + in Ghana, responded concerning the anti-LGBTI + bill in parliament without indicating a clear government position on the matter. This issue was also met with mixed reactions from commentators, with the majority of commentators expressing their disappointment in the president’s unclear response (See ).

In , the analysis focuses on 118 comments that directly address the dissatisfaction or approval of the president’s response to the issue of LGBTI + rights in Ghana. Of these, 84% (99 comments) expressed dissatisfaction with the president’s stance, while 16% (19 comments) commended him for his response. While some commentators question the brilliance of the president’s response, others criticized his lack of representation of the sentiments of Ghanaians on the matter. This challenges the notion of political diplomacy, emphasizing the president’s role in representing the people of Ghana. This diverse range of opinions highlights the complexity of the issue and the challenges faced by the president in navigating diplomatic waters. Additionally, some expressed dissatisfaction with what they perceived as a lack of candor and assertiveness, while others commended the president for what they viewed as a diplomatic and strategic response which highlights the pressure on the president to provide a clearer stance that aligns with people’s sentiments. The findings also concur with those of Nartey & Yu (Citation2023) who found that in Ghana people often use online spaces such as social media to put pressure on the government to act in a certain way, a way they consider appropriate.

4.3. Colorful light display on the Jubilee House

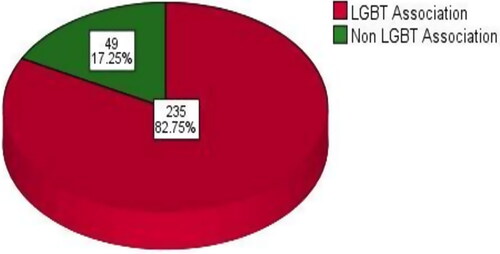

Another issue that attracted the most audiences’ reactions and a discourse of contention among commentators was the colorful lights displayed on the Jubilee House (JBH). The JBH, also known as the Flagstaff House, is the presidential seat of the Ghana government in Accra, the capital city. As part of the LGBTI+-related issues surrounding Kamala Harris’ visit presented in one of the sampled videos the lighting of the Jubilee House with colors was also addressed. This issue also attracted significant comments from the audiences. The audiences also took advantage of the comment section to express their opinions on possible interpretations of the colors in the JBH. From the data, it was observed that commentators’ interpretations of the lights displayed on the JBH had two main associations. LGBTI + and non-LGBTI + associations. However, most of the commentators gave LGBTI + associations to the lighting of the JBH in colors (See ).

According to the host of the show in Video 3, from which video this issue was largely discussed, the colorful lights displayed on the JBH signify the restrengthening of US-Ghana relations, as the lights displayed on the walls of the JBH were a combination of Ghanaian and US flags. The red, gold, and green colors in the light display represent Ghana’s flag, and the red, blue, and white sides of the light display represent the flag of the United States. As observed in , out of the 284 (100%) comments associated with this phenomenon, the majority of commentators 235 (83%) associated the colors with the government’s acceptance of LGBTI + activities in Ghana. In contrast, only 49 (17%) agreed with the interpretation of the displays on the JBH as given by the host of the show. Most of the comments that associated colorful light displays with LGBTI + activities were mostly critical. From the comments, several individuals expressed their opinions on the colors displayed at the Jubilee House in Ghana. The prevailing sentiment in these comments was the perception that the colors resemble those associated with the LGBTI + community. In summary, these comments showcase a range of reactions to the perceived connection between the colors on the Jubilee House and LGBTI + symbolism. Some expressed frustration and disbelief in this interpretation, while others offered alternative explanations rooted in diplomatic relations between Ghana and the United States. These comments collectively highlight the diverse perspectives and interpretations that can arise from symbolic gestures in the public domain. Perhaps D’Angelo’s (Citation2019) constructivist view of framing analysis provides the most plausible explanation, as commentators reject the mainstream media’s interpretation of a phenomenon and construct their meaning for a phenomenon that they hold as truth.

RQ2. How do the audiences’ reactions on YouTube reflect the audiences’ attitudes towards the promotion of LGBTI + rights in Ghana?

Concerning Kamala Harris’ comments on promoting LGBTI rights in Ghana, it was observed from that audiences reactions ranged from claims of Western imposition to an outright rejection of the idea. For instance, in the comment, YTC 505, the commentator emphasizes the importance of self-respect in Africa, particularly Ghana, and criticizes the perception that the US influences the promotion of LGBTI + rights in Ghana. The commentator attributed this influence to Ghanaian leaders’ willingness to compromise their values for financial gain. YTC 5 also expressed a strong rejection of Kamala Harris’s involvement in advocating for the legalization of homosexuality in Africa. The commentator urges her to return to her origin, insisting that Africa is not for sale. On the other hand, the comment labeled YTC 294 straightforwardly rejects the idea of LGBTI + people in Ghana, questioning why the American government is posing such questions. YTC 236, delves into conspiracy theories, suggesting that the promotion of LGBTI + rights is a psychological program backed by elites to alter African culture and family structures. This commentator encourages an investigation into the funding of Kamala Harris’s vice presidency to unveil the truth. YTC 373 draws a parallel to the historical acceptance of practices like slavery, which questions resistance to LGBTI + rights. It argues for acceptance and contends that it does not affect heterosexual marriage rights. Finally. YTC 509 advocates the democratic right of every citizen to choose their gender identity, asserting that no culture should dictate someone’s wishes. Despite the majority of commentators expressing dissatisfaction with the promotion of LGBTI + ideas in Ghana, instances such as YTC 373 and YTC 509 showcase support for LGBTI + rights, albeit in the minority. The presence of supportive comments challenges the overall conservative trend, indicating a diverse range of perspectives that require a nuanced examination. Thus, it can be argued that while conservative sentiments prevail, there is a nuanced landscape with individuals expressing support, highlighting the complexity of public opinion. However, the resistance observed in this study is consistent with broader trends identified in previous research, underlining the endurance of conservative cultural values (Barnes, Citation2022). All in all, the audiences’ reactions on YouTube concerning this issue highlight a conservative sentiment prevailing among commentators, with resistance to the promotion of LGBTI + rights being the dominant theme.

On the issues of the president’s response to the idea of promoting LGBT rights in Ghana, audiences’ reactions revealed that the majority of the audiences were critical in their assessment of the president’s position on the matter. The general sentiment observed here was dissatisfaction with the president’s response as revealed in . For instance, in the case of the comment labeled YTC 515, the commentator expressed disappointment, calling on the president to exhibit bravado in the face of Western imposition just like other African leaders who have taken clear anti-LGBTI + positions. From YTC 636, the commentator compares the president to the leaders of Uganda and Kenya, suggesting that the Ghanaian president should have been more assertive and bold in his response, invoking the metaphor of a borrower as a slave to the lender. Contrary to the critical comments mentioned earlier, there were a few comments that acknowledge the president’s diplomatic move to save face with the West and please his people in the situation. For instance, the comment labeled YTC 669 commends the president’s response, considering it a smart move. The commentator suggests that the president made a fine balance between pleasing the West and avoiding backlash from Ghanaians. In the case of YTC 695, the commentator dismisses the call from some Ghanaians for a more emphatic stance from the president on the issue, suggesting that it is unrealistic for the president to take a clear anti-LGBTI + stance while concurrently seeking funding for anti-terrorism efforts during the IMF negotiations.

Moreover, from audiences’ reactions to the color display on the JBH, we gleaned insights into audiences’ attitudes towards the promotion of LGBT rights as well. From the comment labeled YTC 8, The commentator suggests a punitive response to whoever advised the display of these colors on the Jubilee House, indicating strong disapproval or discontent with the choice of colors. From YTC 13, the commentator asserts that the flag on the Jubilee House indeed displays LGBTI + colors. The plea for Ghana to ‘wake up’ and the mention of potential destruction implies a sense of urgency and concern over the perceived symbolism. From YTC 178, the commentator reinforces the belief that the lighting was displaying LGBTI + colors, emphasizing the idea that this perspective is the ‘truth.’ In the case of YTC 219, the commentator challenged the show host as downplaying the colors, suggesting that it was indeed the LGBTI + rainbow color. However, YTC 381 directly attacks the host of the show urging him not to be a hypocrite and insists that the colors are unmistakably those of the LGBTI + community. The commentator even claims to have sought validation from U.S. citizens, adding an external perspective to the argument. Essentially, these comments reveal a collective concern or suspicion among the commentators that the colors displayed on the Jubilee House are associated with the LGBTI + community. There is a call for acknowledgment, and in some instances, a sense of disappointment or disapproval directed toward public figures who are perceived as downplaying or dismissing this interpretation. The comments reflect not only an observation of colors, but also a broader societal concern or debate around symbolism, identity, and potential international influences. Though most of the comments on this issue were mostly critical, a few commentators however shared similar sentiments as the host of the show. In the case of YTC 121, the commentator expressed frustration and disbelief, questioning how the lights on the JBH could be perceived as LGBTI + colors. The repetition of ‘why’ suggests a sense of incredulity and possible disappointment with the interpretation. From YTC 404, the commentator counters the perception that the lights represent LGBTI + colors, asserting that they are meant to symbolize the union between the United States and Ghana. The commentator questions whether the person making the LGBTI + association was misinformed or intentionally trying to stir the controversy. From YTC 455, the commentator challenged the immediate association of rainbow colors with the LGBTI + community. The comment advocates a more open-minded perspective, suggesting that these colors have various symbolic meanings beyond their association with the LGBTI + community. YTC 548, provides an alternative interpretation of the lights, suggesting that the left light represents the United States’ colors (red, white, blue), and the right light represents Ghana’s colors (red, yellow, green). The commentator emphasizes that this symbolism signifies diplomatic relations between the two countries, and asserts that it has nothing to do with LGBTI + issues. Despite these objective comments concerning the issue, the general attitude observed among the commentators was that of disappointment and dissatisfaction with the leadership of the country for accepting the promotion of LGBTI rights.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

This study analyzed Ghanaian reactions to YouTube videos about Kamala Harris’s comments on the promotion of LGBTI + rights in Ghana and found that most Ghanaians who reacted to the videos used different discursive strategies to express their resistance to the promotion of this agenda in Ghana. The commentators expressed their dissent on the agenda by either outrightly rejecting the promotion of LGBTI + rights in the country, accusing the West of imposing its values on Ghanaians or associating the agenda with conspiracy theories about hidden US agenda to corrupt African cultures. It was also observed that the commentators took advantage of the YouTube comment section to express their dissatisfaction with the response of the President of the Republic of Ghana on the country’s position on promoting LGBTI + rights. Regarding the issue of the colorful lights displayed on the JBH, it was found that most of the commentators associated the colorful lights on the JBH with the LGBTI + symbol of the rainbow and heavily criticized the act as promoting LGBTI + activities in Ghana.

These findings show that the debates on the rights of people in Ghana who identify as LGBTI + is still ongoing and a part of the global discourse on the issue. As Baisley (Citation2015) puts it the debate as to whether Africans are homosexuals or homophobic remains unclear as the continent has had mixed reactions to the global development on this human rights issue. Thus, studies on the rights of people who identify as LGBTI + in conservative cultures like Ghana must be encouraged to keep up with the development of the phenomenon on the continent. Previous studies on the situation in Ghana has found that the media in Ghana often promotes homophobic viewpoints and give their platform to politicians and moral entrepreneurs who often promote homophobic sentiments among the populace (Baisley, Citation2015; Nartey, Citation2022b; Tettey, Citation2016). Our study is consistent with these findings in that the media in their reportage of the issues surrounding Kamala Harris’ visit focused largely on her comments on promoting LGBTI + rights in Ghana. These media reports gave the general population the impression that Kamala Harris’ visit to Ghana was solely about promoting LGBTI + rights which led to the critical reactions of most Ghanaians on the issue.

Also, the study argues that, although YouTube as a social media platform may often be overlooked as a platform for civic engagement, users often take advantage of the comments section to engage with each other on matters of mutual interest as seen in this study. These conclusions are in harmony with those of Uldam & Askanius (Citation2013) and Rospitasari (Citation2021), who found that YouTube can serve as a communicative space for activist groups to advance their activist agenda. Thus, the study concludes that YouTube should not be overlooked as a platform for civic engagement on important issues, as it provides insights into the perspectives of viewers on specific socio-cultural or political matters under deliberation within the public domain.

Besides, the study has significant implications for gender and sexuality studies in Ghana. First, it must be noted that the literature on LGBTI + in Ghana is minimal and this study adds to the ongoing discussion of LGBTI + in Ghanaian society. Secondly, by analyzing YouTube comments, the study offers a glimpse into public attitudes and reactions regarding LGBTI + rights in Ghana. This contributes to the broader understanding of how social media platforms shape and reflect public discourse on sensitive issues, such as gender and sexuality issues particularly in a conservative context like Ghana. Additionally, since Kamala Harris’ visit to Africa was not in Ghana alone but in other countries like Tanzania and Zambia, the issue of promoting the rights of people who identify as LGBTI+ in Ghana sparked so many conversations in the African community. Thus, the findings of this research contribute to the literature on politics, diplomacy, and LGBTI + rights in Africa, particularly through the lens of the Vice President of the United States of America, Kamala Harris. Also, this study allows future researchers to do a comparative analysis of the public attitudes and perceptions about her visit to these countries as mentioned earlier. The study also sheds light on how political events and statements by political figures can influence public perceptions and discussions on LGBTI + rights.

The findings of this study also have implications for human rights activists and pro-LGBTI + advocate groups in Ghana. Concerning the promotion of LGBTI + rights in Ghana, it has been established that Ghanaians largely resist the idea because it is considered foreign to Ghana and a corruption of the moral and cultural values of the Ghanaian society. These conclusions have been established by previous studies on this topic. Given this, pro-LGBTI + groups should not overlook the culture and decolonization frame when attempting to embark on pro-LGBTI + activism in the country. Furthermore, in Ghana, the role of the media in shaping people’s views on LGBTI + related issues should also not be overlooked as the media play a major role in influencing how people perceive the activities of the LGBTI+.

Authors’ contributions

Michael Asante Quainoo was the principal investigator in this study. He was responsible for the conception of the study, the study design, and data collection procedures. He also contributed to the initial data analysis and composition of the initial draft of the manuscript. Daniel Appiah Gyekye is a co-investigator in this study. He assisted with the coding of the data and interpretation of the results of the study. He also contributed to writing the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the faculty members of the Department of Communication Studies at Ankara University for their contributions to this study. We are particularly grateful to Prof. Pinar Ozdemir and Dr. MD Nazmul Islam for their advice on this paper. We are grateful to the reviewers for their guidance. We do recognize that the improvements in clarity and precision of this paper are partly the result of their comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflicts of interest were reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The corresponding author can provide the data for the study upon request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michael Asante Quainoo

Michael Asante Quainoo holds a bachelor’s degree in Communication Studies from the University of Cape Coast, Ghana an M. Ed in Educational Technology and Communications from the Rajamangala University of Technology Thanyaburi, Thailand, and an MA in Media and Communication Studies from Ankara University. He has research interests in digital inclusion, online activism, disability studies and new and emerging media.

Daniel Appiah Gyekye

Daniel Appiah Gyekye holds a bachelor’s degree in English, Religion and Human Values from the University of Cape Coast, a master’s degree in Communication and Media Studies from Purdue University, Northwest, and currently a PhD. Student at the University of Oregon, USA. His research interests include online activism, religious communication, and gaming studies.

References

- Akerele-Popoola, O. E., Azeez, A. L., & Adeniyi, A. (2022). Twitter, civil activisms and EndSARS protest in Nigeria as a developing democracy. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1), 2095744. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2095744

- Baisley, E. (2015). Framing the Ghanaian LGBT rights debate: Competing decolonisation and human rights frames. Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, 49(2), 383–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/00083968.2015.1032989

- Barnes, N. (2022). LGBT human rights and conservative backlash: A case study of digital activism in Mexico. International Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, 3(2),1–11.

- Bosch, T., & Mutsvairo, B. (2017). Pictures, protests and politics: Mapping Twitter images during South Africa’s fees must fall campaign. African Journalism Studies, 38(2), 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/23743670.2017.1368869

- Bosch, T., Wasserman, H., & Chuma, W. (2018). South African activists’ use of nanomedia and digital media in democratization conflicts. International Journal of Communication, 12, 18.

- Brobbery, C. A. B., Da-Costa, C. A., & Apeakoran, E. N. (2021). The communicative ecology of social media in the organization of social movement for collective action in Ghana: The case of# FixTheCountry. Information Impact: Journal of Information and Knowledge Management, 12(2), 73–86.

- Chon, M. G., & Park, H. (2020). Social media activism in the digital age: Testing an integrative model of activism on contentious issues. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 97(1), 72–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699019835896

- D’Angelo, P. (2019). Framing theory and journalism. The International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies, 2002, 1–10.

- De Choudhury, M., Jhaver, S., Sugar, B., & Weber, I. (2016). Social media participation in an activist movement for racial equality. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 10(1), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v10i1.14758

- Denscombe, M. (2010). The good research guide–for small-scale social. Open University Press.

- Entman, R. E. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

- Etikan, I., & Bala, K. (2017). Sampling and sampling methods. Biometrics & Biostatistics International Journal, 5(6), 00149. https://doi.org/10.15406/bbij.2017.05.00149

- George, J. J., & Leidner, D. E. (2019). From clicktivism to hacktivism: Understanding digital activism. Information and Organization, 29(3), 100249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2019.04.001

- Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: Essays on the organization of experience. Northeastern University Press.

- Hopton, K., & Langer, S. (2022). “Kick the XX out of your life”: An analysis of the manosphere’s discursive constructions of gender on Twitter. Feminism & Psychology, 32(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/09593535211033461

- Jenzen, O. (2015). LGBT digital activism, subjectivity and neoliberalism [Paper presentation]. In Centre for Research in Memory, Narrative and Histories Research Seminar Series.

- Jun, J.,Kim, J. K., &Woo, B. (2024). Fight the virus and fight the bias: Asian Americans’ engagement in activism to combat anti-Asian COVID-19 racism. Race and Justice, 14(2), 233–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/21533687211054165

- Karatzogianni, A. (2015). Firebrand waves of digital activism 1994-2014: The rise and spread of hacktivism and cyberconflict. Springer.

- Kaun, A., & Uldam, J. (2018). Digital activism: After the hype. New Media & Society, 20(6), 2099–2106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817731924

- Kellner, D., & Kim, G. (2010). YouTube, critical pedagogy, and media activism. The Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 32(1), 3–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714410903482658

- Kofi Frimpong, A. N., Li, P., Nyame, G., & Hossin, M. A. (2022). The impact of social media political activists on voting patterns. Political Behavior, 44(2), 599–652. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09632-3

- Malik, B. (2022). Social media activism and offline campaigns in the fight against domestic violence in Ghana. A study of selected activists on Facebook. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(3), 3028–3039.

- Mao, C. (2020). Feminist activism via social media in China. Asian Journal of Women’s Studies, 26(2), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/12259276.2020.1767844

- Mateos, O., & Erro, C. B. (2021). Protest, internet activism, and sociopolitical change in Sub-Saharan Africa. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(4), 650–665. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764220975060

- Matthews, R., & Ross, E. (2010). Research methods: A practical guide for the social sciences. Pearson Education Ltd.

- Nartey, M. (2022a). Advocacy and civic engagement in protest discourse on Twitter: an examination of Ghana’s# OccupyFlagstaffHouse and# RedFriday campaigns. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, 19(4), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/14791420.2022.2130950

- Nartey, M. (2022b). Marginality and otherness: the discursive construction of LGBT issues/people in the Ghanaian news media. Media, Culture & Society, 44(4), 785–801. https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437211045552

- Nartey, M., & Yu, Y. (2023). A discourse analytic study of# FixTheCountry on Ghanaian Twitter. Social Media + Society, 9(1), 20563051221147328.

- Neuman, W. L. (2012). Nonreactive research and secondary analysis. In Basics of social research.

- Ozkula, S. M. (2021). What is digital activism anyway? Social constructions of the “digital” in contemporary activism. Journal of Digital Social Research, 3(3), 60–84. https://doi.org/10.33621/jdsr.v3i3.44

- Pan, Z., & Kosicki, G. M. (1993). Framing analysis: An approach to news discourse. Political Communication, 10(1), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.1993.9962963

- Portwood-Stacer, L., & Berridge, S. (2014). Introduction: privilege and difference in (online) feminist activism. Feminist Media Studies, 14(3), 519–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2014.909158

- Rospitasari, M. (2021). Youtube as alternative media for digital activism in documentary film creative industry. Jurnal Studi Komunikasi (Indonesian Journal of Communications Studies), 5(3), 665–692. https://doi.org/10.25139/jsk.v5i3.3779

- Sasu, D. D. (2024). Social media in Ghana- statistics & facts. https://www.statista.com/topics/9778/social-media-in-ghana/#topicOverview

- Tao, W., Li, J. Y., Lee, Y., & He, M. (2022). Individual and collective coping with racial discrimination: What drives social media activism among Asian Americans during the COVID-19 outbreak. New Media & Society, 26(6), 3168–3187. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221100835

- Tettey, W. J. (2016). Homosexuality, moral panic, and politicized homophobia in Ghana: Interrogating discourses of moral entrepreneurship in Ghanaian media. Communication, Culture & Critique, 9(1), 86–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/cccr.12132

- Tortajada, I., Willem, C., Platero Méndez, R. L., & Araüna, N. (2021). Lost in transition? Digital trans activism on YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 24(8), 1091–1107. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1797850

- Townsend, L., & Wallace, C. (2016). Social media research: A guide to ethics. University of Aberdeen, 1(16) 1–16.

- Turley, E., & Fisher, J. (2018). Tweeting back while shouting back: Social media and feminist activism. Feminism & Psychology, 28(1), 128–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353517715875

- Uldam, J., & Askanius, T. (2013). Online civic cultures? Debating climate change activism on YouTube. International Journal of Communication, 7, 20.

- Worldometer. (2024). Ghana population. https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/ghana-population/