Abstract

The burgeoning food waste problem is driving environmental pollution and climate change due to landfilling of waste. It is imperative to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and lower carbon footprint through food waste management. In the culinary setting, a vast amount of food waste is generated from food preparation. However, there is no module to educate staff on this. In this study, a culinary waste management (CWM) module was introduced to train culinary arts students to reduce culinary waste in the food preparation process, from cleaning to assembling. It is essential to assess the user-friendliness of the module during practical implementation. This study aimed to explore participants’ awareness and understanding of CWM before and after implementing of a CWM module in teaching kitchens and identify the motivators and barriers to its implementation. A total of 35 participants, consisting of students, teaching chefs and cleaning staff’s were recruited at Sunway University, Malaysia. Themes derived in the pre-module interview revealed a varying degree of engagement among participants, with low literacy, alongside barriers like labor-intensiveness and concern over hygiene. The post-module interview highlighted positive psychological and cognitive impacts on participants with motivators that drive them to practice CWM. Nevertheless, barriers such as resistance to novelty impeded the implementation. Therefore, CWM is the way forward to reduce the significant amount of waste generated in culinary settings. Integrating this CWM module into the education-industrial system will equip future culinary professionals with the knowledge and skills needed for.g a sustainable culinary career.

1. Introduction

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 12 aim to reduce food waste by 50% in 2030. But each year, the world is moving further away from that goal as 1.3 billion tons of food waste are generated annually (World Food Programme, Citation2020). The Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) of the United Nations (UN) highlighted that the amount of food wasted can provide sustenance for an estimated 1.26 billion individuals annually (FAO & WFP, Citation2022). This staggering amount of food waste has negatively impacted the economic, environmental and social aspects.

From the economical perspective, managing food waste is getting costlier each year. The World Bank estimates that the negative impacts produced by food loss and waste, land degradation and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from agricultural practices cost at least USD 6 trillion worldwide (The ASEAN Secretariat Jakarta, Citation2022). Furthermore, food waste leads to severe environmental impacts, such as increases GHG production, resulting in global warming and environmental pollution. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), U.S. food loss and waste produces 170 million metric tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) equivalent to GHG emissions, excluding landfill emissions. This amount is equal to the annual CO2) emissions of 42 coal-fired power plants (Buzby, Citation2022).

On the social aspect, approximately 690 million people remain hungry worldwide, while 3 billion people are unable to afford a healthy diet. Furthermore, the increase in food waste generated will affect food insecurity rates. According to the Global Report on Food Crisis 2022 Mid-year Update, up to 205 million people will be at risk of acute food insecurity in 45 countries by January 2023 (World Food Programme, Citation2022).

Malaysia is the 4th highest food waste generator in the world after Mexico, Australia and Nigeria (Roy et al., Citation2023). Malaysian households produce approximately 17,000 tonnes of food waste daily, and of that amount, 24% is avoidable food waste (Hani, Citation2022). Avoidable food waste is food that is edible at some point of time prior to discarding such as apples and bread, whereas unavoidable food waste is waste originating from food but is less likely to be consumed by humans such as bones and fruit peelings. The amount of avoidable food waste in Malaysia has the potential to provide three meals a day for 2.9 million people (Hani, Citation2022).

1.1. Factors contributing to food waste

There are numerous reasons contributing to food waste, and household is one of the main reasons (Chia et al., Citation2023). Apart from households factors, restaurant and hotel sectors emerge as one of the major contributors to global food waste (Betz et al., Citation2015; Goh & Jie, Citation2019). One of the primary causes of food wastage within these establishments is the inadequate demand forecasting in their culinary kitchen operations, which leads to an overabundance of food ingredients (Taib Ali & D’cruz, Citation2022). This is clearly noticeable in restaurants that serve buffets where customers have an unlimited flow of food for a fixed price (Papargyropoulou et al., Citation2019). In addition, Goh and Jie (Citation2019) revealed that staff in the hospitality industry discard old ingredients for fresher ones to maintain the food quality. Moreover, although demand forecasting is one of the most effective ways to prevent oversupply of food ingredients, it is challenging to be able to accurately forecast the food needed due to the variations in demand especially in Malaysia with different festivals (Filimonau et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b). Moreover, Filimonau and Coteau (2018) highlighted that there is insufficient research done to address food waste in the hospitality and food service industry. Thus, it is important to find effective ways to reduce food waste in the hospitality and food service sectors, such as implementing a culinary waste management (CWM) module in Malaysia.

In education, the word ‘module’ is referred to a unit or section of a course that focuses on a specific topic or set of skills. Operationally, a Culinary Waste Management (CWM) module is a unit incorporated to the culinary arts curriculum, designed to train professional kitchen users on managing food waste during preparation sustainably. A CWM module can be a comprehensive system that aids in reducing, reusing and recycling different materials in the hospitality sector to equip culinary professionals with the knowledge and skills on food waste. Amicarelli et al. (Citation2021) revealed that staffs at restaurants are aware of food waste issues and are looking for solutions to overcome them but struggle due to different obstacles. Their participants proposed that efforts are required by both hotels and suppliers. For instance, excess cooking ingredients can be reused in the hotel for other recipes, while surplus food can be distributed to other institutions in need, such as animal shelters. Furthermore, waste can be segregated into different categories such as organics, plastics and papers and put them to good use based on their respective usage. In addition, demand forecasting can be used to help hotel staffs to predict the number and nationalities of guests in attendance before preparing meals and buffets, which prevents the culinary team from cooking an excessive amount of food (Amicarelli et al., Citation2021; Principato et al., Citation2018). Therefore, if culinary staffs are equipped with the CWM module, they will obtain the necessary knowledge and skills to manage waste effectively.

Although the CWM module can be used in the food service sector, the adoption rate is slower compared to the hospitality sector. This is because CWM module such as redistribution of surplus food and repurposing excess food are commonly deemed unfeasible in restaurants due to the smaller scale of the business (Filimonau et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b). Moreover, Sakaguchi et al. (Citation2018) highlighted that the accessibility to the knowledge on food management is crucial for waste reduction. Nevertheless, based on the articles reviewed, previous studies on food waste have primarily focused on developed countries and households, and not on the educational institutions with hospitality programs. In Malaysia, there is no centralized database for collecting food waste generated in educational institutions. Nevertheless, several researchers who independently conducted studies on food waste at various universities revealed that massive amount of food waste was generated in higher education institutions. For instance, Saalah et al. (Citation2020) found that Universiti Malaysia Sabah generated 127.7 kg of food waste weekly, while Izan et al. (Citation2017) reported an average of 74 kg of food waste produced daily at Universiti Malaysia Terengganu. Therefore, it is crucial to initiate the CWM module in the educational setting.

Drawing insights from the CWM module in other countries and also the lack of food waste management systems in developing countries (Thi et al., Citation2015), the Malaysian hospitality sector has already begun implementing similar modules locally (Samsuddin et al., Citation2022). However, despite the large amounts of food waste generated by educational institutions with hospitality programs, the CWM module is not extended to universities or schools, to the authors’ knowledge. Therefore, it is important to implement the CWM module in an educational context to educate future generations regarding food waste as well as reducing the food waste generated throughout the teaching and learning process.

In this study, a CWM module (Appendix 1) was introduced with the purpose to reduce culinary waste that occurs throughout the food preparation process, from cleaning till assembling. This CWM module advances planetary health through SDGs 12 and 13 - ‘Responsible Consumption and Production’ and ‘Climate Action’. The CWM module is expected to be able to tackle global food waste challenges and climate change by promoting resource efficiency and reducing environmental footprint in the university and hospitality industry settings.

This research aims to achieve two objectives as below:

To explore participants’ awareness and understanding of CWM before and after the implementation of a CWM module in teaching kitchens

To identify the motivators and barriers to the implementation of the CWM module

2. Methodology

2.1. Sample/participants

A purposive and criterion-based sampling was employed in this study. The inclusion criterion for the participants is individuals who produce and handle culinary waste during the food preparation process on a regular basis. Hence, the participants were invited from the culinary arts and hospitality programs of the Department of Culinary Arts and School of Hospitality at Sunway University main campus, Malaysia. 30 students, 2 teaching chefs and 3 cleaning staff were interviewed by the researchers. These participants were specifically recruited from the cuisine and pastry kitchen practical classes, from the program of Diploma in Culinary Arts. The age range of the participants was between 18 and 34 years old (Agemean = 18.3). Out of 35 participants, 19 were males and 25 were Malaysians. Among the students, 13 have work experience in food and beverage settings prior to this course, including the baking industry, restaurants, hotels, and cafes. The data collection activities started on 10 January 2022 till 16 December 2022, spanning across three academic semesters, and ceased when the data reached the point of saturation. See for additional background information on participants below.

Table 1. Participants background information.

2.2. Research design

This study employed a phenomenological qualitative approach, utilizing semi-structured interviews to gather in-depth insights from participants, aimed to understand and describe the lived experiences of the participants (Denzin et al., Citation2024) to achieve the two research objectives. By conducting semi-structured interviews, the study captured the nuanced and evolving perceptions of the participants, allowing for a comprehensive assessment of their initial knowledge and the impact of the educational intervention. Furthermore, the flexible nature of semi-structured interviews facilitates the exploration of individual experiences and perspectives, thereby uncovering the diverse factors that influence the adoption and effectiveness of CWM practices in culinary education. This approach ensures that the data collected is rich and detailed, providing valuable insights for enhancing the design and delivery of CWM modules in culinary training programs.

2.3. Implementation of CWM module and Research procedures

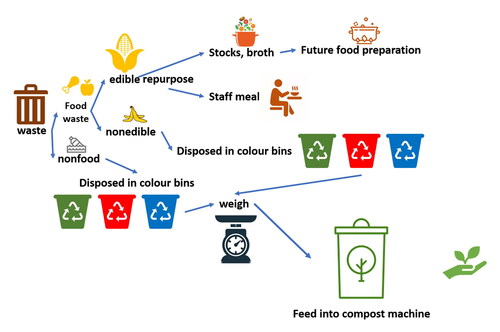

First and foremost, the ethics approval (Ref No: SUREC 2021/072) was obtained from the University Research Ethics Board before the commencement of data collection. Next, with the support of schools for culinary arts and hospitality, the participant recruitment activities were carried out by approaching potential volunteers right after their classes ended. The purpose of study and the approach of data collection were explained. The volunteer participants were then be given a copy of Participant Information Sheet that outlined the nature of the study, participants’ right and confidentiality practice. Upon agreeing, participants then read through and signed a consent form. The contents on the consent form include: 1. participants agree to volunteer in the project, 2. they are free to withdraw from the project at any time without any disadvantages, 3. if personal identifying information is collected, it will be destroyed at the conclusion of the project but any raw data on which the results of the project depend will be retained in secure storage, and 4. the results of the project may be published in scientific journals, conferences and through other media. Next, participants identified their preferred time and scheduled for interviews. The study process involved two interviews with the same participants, in between the CWM module developed by a senior teaching chef. The volunteers underwent a 2-month period of learning and familiarizing themselves with the CWM module. (A further description of the CWM module is provided in Appendix 1.) The pre-CWM-module interview was to access the basic understanding and practice of CWM among the participants; and the post-CWM-module interview was to identify their new experience after learning and adhering to the CWM for a minimum of 2 months. The individual face-to-face interviews were conducted between January and December 2022, subjected to the availability of culinary arts classes. Each interview lasted around 15 to 30 minutes. A token of appreciation in the form of RM30 Touch n Go e-wallet voucher (about the worth of USD6.5) was given to the volunteers after the post-CWM interview. The interviews were all audio recorded and transcribed for further analysis. [Graphical abstract]

2.4. Interview questions and data analysis

Prior to the CWM module, the volunteers were interviewed using three pre-module questions:

Pre1. What is your normal practice in handling kitchen waste?

Pre2. What is your opinion on such practice?

Pre3. Do you know what culinary waste management is?

Approximately 2 months after the CWM training and practice, the volunteers were invited for a post-module interview. In order to achieve the second part of Research Objective 1 as well as Research Objective 2, five post-module interview questions were used:

Post1. How were your experiences in following the new system to manage the kitchen waste?

Post2. In what way the new system is different from your previous method?

Post3. What are the encouraging factors for you to inculcate the system into your regular practice?

Post4. What are the hindrances that obstruct you from practicing the new system?

Post5. In what way the system needs to be modified to improve its practicality and effectiveness for you?

3. Results

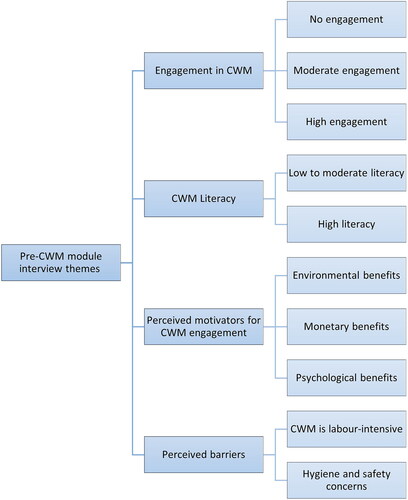

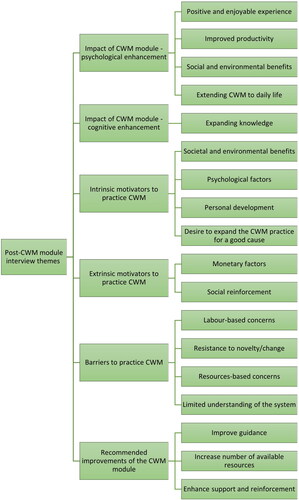

Before participants were exposed to the CWM module, they were interviewed to understand their daily practice in handling culinary waste, their opinion on CWM practices and their understanding of CWM to establish basic understanding of waste management. A summary of themes derived from the interview before and after the implementation of the CWM module as shown in and , respectively.

3.1. Pre-CWM module interview themes

3.1.1. Engagement in CWM

The levels of participants’ CWM engagement prior to learning the module can be categorized as no engagement, moderate and high level of engagement. Most of the respondents displayed a high level of CWM engagement. These participants stated that they were already repurposing food waste in personal and professional settings, such as in their homes, at the university and in their workplaces. Participants gave examples of these CWM practices such as ‘the fats could be kept for making oil or herbs’ (P3),’reuse remaining ingredients—onion skin used to make onion powder, pineapple skin to make detergent’ (P6), ‘coffee grounds kept and given to customers’ (P9) and feeding leftovers to their pet dogs (P8, P12, P14, P16). Two participants had a moderate level of engagement in kitchen waste management. They explained that they ‘don’t reuse food waste, but tries to reduce it’ (P26), and that the ‘food waste that is not used [as compost] in soil is thrown away’ (P23). Nonetheless, a small number of participants did not practice any form of CWM prior to learning the module. These participants disposed all kitchen waste as general waste, without any form of waste segregation or repurposing.

3.1.2. CWM literacy

Participants’ levels of CWM literacy vary from low to high levels. Approximately half of the participants displayed little to no understanding of CWM practices. For instance, certain participants stated that ‘maybe there’s different ways for organic waste to be separated’ (P24), or ‘there is a pipe for filtering oil from kitchen waste’ (P19). Some students even mentioned that ‘chefs didn’t explain in detail, usually the kitchen manages food waste’ (P5), and ‘not much of the food waste can actually be processed’ (P4), which reflects an inconsistent understanding of CWM. Participants with low CWM literacy also expressed uncertainty over how to segregate and repurpose food waste (P13, P17, P18, P28, P30, P33, P34, P35). Nonetheless, there were also participants who possessed a high level of CWM literacy prior to the module. These participants mentioned they would ‘keep the extra stuff other than wasting it…find a way on what can I use it for’ (P2), while another stated CWM is to repurpose food waste and ‘use it as fertilizer’ (P11).

3.1.3. Perceived motivators for CWM engagement

Many participants cited environmental benefits as one of the reasons why CWM is important. These respondents believe that CWM reduces food waste and protects the environment. ‘It’s like a better way to manage the waste or like trying to not waste it’ (P14), ‘making sure that the waste produced is being used for something’ (P16). Participants also cited monetary benefits such as maximizing the usage of ingredients and cost efficiency as one of the perceived benefits of CWM. ‘That’s basically like an easy side income’ (P6) and ‘food waste can be turned into so many products’ (P28). Furthermore, participants think that CWM will bring them psychological benefits which include alleviating personal guilt (P16: ‘gives you a sense of morality’) and convenience (P4: ‘this waste management can be taken into action easily by everyone and any age or any experience level’). Several participants are also eager to spread this knowledge to others, which further enhances their sense of personal achievement. ‘Will teach others how to practice this’ (P27).

3.1.4. Perceived barriers for CWM engagement

Nevertheless, several participants think that CWM is labour-intensive, describing it as ‘difficult and troublesome’ (P3), while others have a low perceived effectiveness of the practice. P6 stated it would be ‘quite hard to actually keep these ingredients and preserving them to make sure that they are actually usable’. Hence, these participants think that the effort that goes into CWM is not proportionate to the outcome, and this becomes a barrier for them to segregate and repurpose kitchen waste. Certain respondents also expressed concerns over hygiene and safety in the CWM practice. Some mentioned that the ‘rubbish bin will smell’ (P12), and that ‘throwing away food [keeps] the house clean’ (P15). Moreover, P13 also stated ‘I’m scared the food will get spoiled and I will be sick’.

3.2. Post- CWM module interview themes

3.2.1. Impact of CWM module - psychological enhancement

Participants reported four types of psychological enhancement after learning the CWM module. These psychological enhancements are 1) positive and enjoyable experience, 2) improved productivity, 3) social and environmental benefits, and 4) extension of CWM to participants’ daily lives. Seven participants described the experience of learning the CWM module as a ‘good experience [which is] easy to follow’ (P24). These feelings of enjoyment can serve as a reinforcement to increase participants’ CWM behaviours. Furthermore, participants reported improved productivity in the kitchen since the implementation of the CWM module. P4 stated that ‘more food waste is recycled now’, while seven participants agreed that the module is a more organized way to manage food waste (P5, P7, P13, P20, P24, P34, P35).

Additionally, a significant portion of participants mentioned the social and environmental benefits brought by the CWM module. Environmental benefits refer to waste reduction by reducing and recycling food waste. Participants noted that less food waste was produced after the module was implemented as more types of kitchen waste were repurposed compared to before. For instance, vegetable trimmings and animal bones were used for soup stocks, and eggshells and onion peels were used to make organic compost. The CWM module also resulted in social benefits as excess food can be donated to charity (P13). Furthermore, several participants reported a willingness to extend the CWM practice into their daily lives. P30 stated that ‘participant now learn to think-out-of the-box instead of just throwing food waste’. This sentiment is in line with other responses, for instance, P32 mentioned that their exposure to the CWM module has made them think about ‘[improving their own] independent disciplining’.

3.2.2. Impact of CWM module - cognitive enhancement

Participants reported an increase in knowledge of CWM after learning the module. Several mentioned they were not aware of the practice prior to taking the module (P6, P11, P23, P28, P30), while one respondent noted that the module helped them understand how to manage food waste (P31). P21, a teaching chef in the School of Culinary Arts, stated that through the module, ‘students can learn how to manage kitchen waste before going out to the industry’. This expansion of knowledge and exposure brought by the CWM module also increases participants’ curiosity towards the practice of food waste management. For example, one participant mentioned they were ‘not sure what the eggshell is used for, makes it interesting and curious to know more’ (P22).

3.2.3. Intrinsic motivators to practice CWM

Overall, the majority of participants reported intrinsic factors as motivators to continue the practice of CWM. These motivators include societal and environmental benefits, psychological factors, personal development, and desire to expand the CWM practice for a good cause. Societal benefits refer to the ways participants can benefit the society by practicing CWM, such as reducing food wastage to be mindful of the underprivileged communities. For instance, P25 expressed when they are reminded of ‘some people [who] don’t have the food to eat’, they will try to reduce their food waste to show consideration to these communities. Additionally, several participants also cited environmental benefits as reasons to practice CWM, such as reducing waste and environmental pollution. According to P6, a student, ‘knowing the fact that [the kitchen waste] going to be used to a good thing’ encourages them to participate in CWM. The repurposed food waste can then be ‘used as fertilizer to plant some fruits or plants’ (P8).

Another common intrinsic motivator for participants to practice CWM is psychological factors. Participants mentioned that they will continue reducing and repurposing food waste as it aligns with their personal values (P24) and makes them ‘feel good knowing that [they’re] not wasting anything’ (P28). CWM also acts as a psychological motivator because it ‘makes the environment around [the participant] very clean’ (P26) and prevents stress caused by unclean surroundings.

Furthermore, participants cited personal development as a motivator to apply CWM. P29 stated ‘because [their] dream is to be a chef…so this kind of thing should be practice on a daily basis’. Other participants echoed this sentiment by saying that CWM helps them ‘to improve [themselves]’ (P26) and ‘be more professional’ (P28). P30 also mentioned that ideas like the CWM module drives them to think of creative solutions to existing problems.

Lastly, participants’ desire to expand the CWM practice for a good cause also acts as an intrinsic motivator to CWM behaviours. Several participants mentioned teaching their peers and family members about CWM and encouraging them to take up this practice (P13, P28, P30). One chef, P21, also expressed their desire to ‘share [their] knowledge and information to the students’. These show that the ability to influence others to practice CWM increases participants’ desire to engage in CWM behaviours.

3.2.4. Extrinsic motivators to practice CWM

Participants cited monetary factors as one of the main extrinsic motivators to practice CWM. By repurposing food waste, they can reduce the cost used to buy new ingredients. For instance, vegetable trimmings that are usually thrown away can be used to make soup stocks, which reduces the cost spent on buying fresh vegetables for soup. P4 stated that ‘these waste can be turned into something profitable’, referring to the food waste that is converted into compost, which can later be sold to earn side income. They also said that ‘money is a good motivator’. Another extrinsic motivator is social reinforcement, which encompasses peer pressure and reinforcement from colleagues, lecturers and family members. For instance, P32 mentioned that the chef strictly reinforces CWM practices. The respondent also described how their family started applying CWM, which later became a common practice in their household. P24 highlighted the role that social reinforcement plays in encouraging CWM, saying ‘when you are doing with lot of people, it’s far easier’.

3.2.5. Barriers to practice CWM

This study found several barriers to practicing CWM in personal and professional settings. Firstly, participants cited labour-based concerns as an obstacle to engaging in CWM. These concerns revolve around CWM being a troublesome and time-consuming practice, as ‘there are more steps included’ in managing waste (P25). Some participants also mentioned that laziness results in a lack of motivation to practice CWM (P20, P30, P35), while P30 stated that they do not consider the positives of segregating food waste when they are busy cooking. These labour- and time-based concerns act as roadblocks to participants’ willingness to practice CWM. Furthermore, resistance to novelty and change acts as a barrier to practicing CWM. To many participants, the CWM module represents a new way to manage kitchen waste that they are unfamiliar with. This module deviates from existing norms and habits, where kitchen waste is usually disposed of together with general waste. Hence, many participants cited concerns about changing old habits to suit the new CWM module. P1 stated that it is ‘quite hard to change people’s mindset that is set for so many years’, while P11 mentioned the difficulty of conveying this new practice to the elderly at home. Moreover, people tend to be apathetic to novel ideas that do not directly benefit them. As P30 and P35 mentioned, it may be challenging to implement CWM when people do not see its importance. Some may even think, ‘it’s not my responsibility, why should I be doing this?’ (P35).

In addition, several participants stated resources-based concerns as a roadblock to applying the CWM module. Participants were apprehensive about storing food waste in the kitchen, which might contaminate the clean food that will be served to customers. ‘Meats and vegetables cannot be together. There will be like [bacterial infection], so separating those maybe a bit hard than usual’ (P3). Participants also expressed concerns about storage. ‘Trying to figure out where to put those ingredients instead of throwing it away might be one problem’ (P6), and P8 mentioned that they will ‘need to prepare more containers and wash up all the containers’, which will incur more labour. A lack of resources may also present a hindrance to practicing CWM. Some respondents stated that there were ‘not enough bins for food waste’ in the university, making it harder for them to segregate waste (P33, P34). Moreover, several participants were concerned about the CWM module’s dependency on the composting machine. ‘If the machine breaks down, the kitchen waste will become hard to manage’ (P19). One participant also suggested that in order to extend the CWM practice to the whole community, the manufacturing company needs to ‘make more affordable food compost machines’ (P1).

Lastly, this study found that a limited understanding of the system acts as a barrier to participation in CWM. Seven participants stated that they were still unfamiliar with the CWM process upon completion of the module (P1, P5, P13, P23, P24, P26, P33). This confusion typically stems from a limited understanding of the waste segregation process and the types of food waste that can be reused. ‘Sometimes I am confused about which items belong to which bins’ (P13), and ‘I don’t know if this food waste can reuse or not’ (P23).

3.2.6. Recommended improvements of the CWM module

When asked if they had any suggestions on improving the CWM module, the majority of the participants recommended providing students with more guidance on the module. P3 proposed having ‘a class on how [CWM] actually works…I want to know what happens after [the waste segregation] because they don’t really tell us’. P25 suggested to ‘label the bins’, and this is echoed by P22 and P24, who recommend using bins of different colours or pasting pictures or symbols on the bins to help users differentiate the type of waste that goes into each bin.

Secondly, participants proposed increasing the number of resources available. At the campus level, P23, P24 and P33 recommended increasing the number of bins that collect food waste throughout the university. P9 even suggested installing sensors in the bins to detect whether the food waste inserted is acceptable, although it is unclear whether this technology will be available at the time of writing. On the household and consumer levels, P1 urged companies to make food composting machines more affordable to encourage consumers to repurpose food waste.

Participants also recommended enhancing support and reinforcement to encourage the practice of CWM. This reinforcement may take the form of monetary incentives, training, education and peer influence. P21, a chef, proposed ‘giving [students] more support in terms of materials…especially lecture materials’ to educate students on the importance of segregating food waste. Participants also suggested community efforts to maintain the CWM practice such as ‘build a community to collect the food waste from business’ (P8) and peer influence where participants encourage friends and family to practice CWM (P9, P20). Several participants recommended stricter measures of implementing CWM, such as ‘make the system compulsory to practice for each student’ (P13) and ‘punish those who don’t follow it’ (P35). On a national level, two participants were of the opinion that federal law enforcement is required to instil the CWM practice in people: ‘government should impose a regulation for citizens to follow’ (P1, P11). Businesses in the Food and Beverages industry should also train their employees on kitchen waste management (P1).

4. Discussion

The aim of this study is to explore participants’ understanding and awareness of CWM before and after the implementation of the culinary waste management module. The interviews before the implementation of the CWM module showed that most of the participants had basic knowledge of the importance of CWM, however, it has not been a common practice to be incorporated in their daily life. There was a lack of awareness among the students and staff regarding the importance of segregating culinary waste (e.g., food waste vs plastic waste) to ensure that the waste could be recycled or used for composting. CWM is a developing area in the country; however, continuous initiatives have been implemented to reduce the culinary waste generated and promote sustainable practices in waste disposal, but there is still an area for improvement in the industrial settings (Soliman, Citation2020).

In terms of motivators and barriers to practice food waste management, the findings show that before the implementation of the CWM module, the participants indicated benefits for the environment, cost effectiveness and psychological satisfaction. However, the practical aspects of waste managements were described as troublesome and time consuming by the participants. It is essential to address efforts to overcome these challenges by enhancing education, developing efficient waste management methods and providing resources for the better CWM (Cheng et al., Citation2022; Hamzah et al., Citation2022), including the implementation of policies and regulations that allow collaboration between different stakeholders that are in charge of sustainable practices related to waste management (Wu et al., Citation2020).

The results of the post-interviews showed a significant amount of evidence related to benefits of the CWM module. Psychological and cognitive enhancement are one of the key benefits of the participation in the CWM programme. Participation in the educational programme allowed participants to experience sense of accomplishments, increase awareness on sustainable practice, develop skills for recycling and repurposing of food waste and enhance creativity in mindful cooking. The developed skills related to optimizing waste management may contribute to environmental safety and have a strong environmental impact (Obersteiner et al., 2021).

Intrinsic and extrinsic motivators play a significant role in implementation of CWM. Intrinsic motivation is focused on the process of the activity itself, the experience of interest and autonomy in making decisions, and has the greatest potential in maintaining behaviours. Attitudes, subjective and moral norms are considered as the most important predictors of household CWM behaviour (Yuan et al., Citation2016). Moreover, social norms help to expand the practice of waste sorting behaviour to farming and other industries (Ahmed et al., Citation2021). Extrinsic motivators to implement CWM may include convenient facilities that can lead to contribution to the society through converting food waste into compost and monetary reinforcement. Although it is known that intrinsic motivators are the most powerful in term of sustainable environmentally oriented behaviour, an introduction of compulsory waste separation measures could improve CWM among students and consumers (Kaur et al., Citation2021).

Barriers to incorporate CWM into the everyday practice include the culinary kitchen settings that may prevent a proper storage of food ingredients, time pressure to cook dishes and to ensure the best quality of food, and inflexible menu when it comes to the Higher Educational settings (Kaur et al., Citation2021). Other barriers refer to lack of facilities and infrastructure to separate culinary waste as well as lack of awareness on the importance of waste management (Goh et al., Citation2022). These barriers may impact the successful implementation of CWM module related to food waste reduction and overcoming these barriers would require to develop practical strategies that allow to ease the process of food waste management, advocate for circular economy practices and recycling, conduct public awareness campaigns and establish effective waste management resources and infrastructure (Amicarelli et al., Citation2021; Goh et al., Citation2022).

The implications of the development and implementation of CWM are significant on governmental, societal and environmental levels. On a governmental level, introduction of effective CWM may lead to improvement of policies and regulations related to waste reduction, recycling and composting. Composting can assist with reducing the volume of food waste, eliminating of harmful chemical substances and producing fertilizer (Sun et al., Citation2021). Governmental funding or waste management initiatives, infrastructure development and public awareness campaigns would prioritize projects aimed at promoting sustainability and environmentally oriented behaviour. At a societal level, CWM may contribute to the circular economy promoting bioenergy production and sustainable practice (Sun et al., Citation2021). More importantly, CWM interventions may contribute to the development of social norms and culture of responsible consumption, fostering a sense of accountability towards the environment. When individuals become more conscious of their consumption habits, it leads to reduction of food waste and higher appreciation of environmental resources. From an environmental perspective, reducing food waste will contribute to a decrease in GHG emissions and help conserve natural resources. Overall, CWM practices will help to mitigate issues related to environmental resources, promote sustainable behaviour and more efficient usage of resources (Sulewski et al., Citation2021).

Based on these research findings, the following recommendations could be suggested. Firstly, it is important to simplify the process of sorting and recycling food waste, e.g., have clearly labeled bins near the station and precise instructions on how to manage culinary waste and contribute to composting. Composting of kitchen scraps that yield fertilizer could be done in the industry as this is a cost-effective method for treating food waste that promotes sustainable behaviour (Arrigoni et al., Citation2018). Next, behaviour modification techniques could be used in promotion of CWM. Offering rewards such as discounts or coupons for individuals who practice waste management can encourage more active participation in sustainable behaviour and create a sense of personal gain. Another recommendation is to consider the gamification of waste management, especially when talking about educational programmes. Developing game-like features such as points, levels, leaderboards, social interactions may lead to greater engagement of individuals, promote intrinsic motivation, educate and raise awareness on sustainable waste management practice (Cheng et al., Citation2022).

Integrating CWM into curricula can cultivate environmental awareness, promote sustainable practices, and foster a culture of responsibility among students. Through experiential learning opportunities and theoretical frameworks embedded within the curriculum, students gain a deeper understanding of the environmental challenges posed by waste generation and disposal. By engaging in hands-on activities such as waste audits, recycling initiatives, and sustainability projects, students not only learn about the importance of waste reduction but also actively participate in implementing solutions. Additionally, CWM may serve as a platform for interdisciplinary learning, involving various departments that could further promote sustainable behaviour (Yusuf & Fajri, Citation2022). Furthermore, in the context of governmental institutions and business entities, the integration of CWM not only promises environmental benefits but also holds economic advantages. By implementing efficient waste reduction, recycling, and disposal strategies, institutions can reduce operational costs associated with waste management. Highlighting these tangible economic benefits can help garner support and investment for CWM initiatives from stakeholders across various sectors. In the Malaysian context, implementing the Comprehensive Waste Management (CWM) module as part of higher education curricula would provide a structured and practical approach to managing food waste in various settings.

Although this study looked at the CWM module from multiple perspectives, there are a few limitations of this study that should be mentioned. This qualitative study has been conducted in the Malaysian context so findings may not be generalized to other regions. The results of pre-CWM interviews showed that most of the participants had some level of familiarity with the principles of CWM and generally held positive attitudes towards this practice, however, it is important to note that these findings may not be representative of the broader population. Secondly, barriers and challenges in implementing CWM were found among the participants. To overcome these barriers, it is recommended to develop a holistic CWM module whereby manuals or guidebooks for different stakeholders such as degree students, trainers and waste handlers can be developed. With a holistic and comprehensive CWM module, students, trainers and waste handlers can be empowered to practice CWM via the teaching and learning process as well as practicing CWM in their operation process. Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable insights on attitudes and motivations related to the implementation and execution of CWM.

5. Conclusion

The results of this study showed that it is essential to include CWM module into the educational curriculum to promote sustainable practices among culinary arts students who are potentially the future chefs. This module provides a sustainable waste management knowledge and skills to succeed in a professional culinary career with environmental mindfulness. By early exposure to the knowledge and practice of managing culinary waste through recycling and composting, aspiring culinarians who would actively applying such sustainable practice can be produced to significantly lower the loss of valuable resources via recovering, reusing and repurposing culinary waste. Efficient CWM will lead to production of renewable energy sources and maximize resource utilization, creating a more sustainable and resilient eco-systems. Overall, Malaysia is making significant efforts to improve CWM practices, but there are still areas that require further development to achieve sustainable practices and a sound waste management programme. Conducted in Malaysia, the study’s findings may not be generalizable to other regions, and further research should be done involving broader populations in different contexts. Future research could focus on exploration of specific strategies to overcome identified barriers and challenges in CWM implementation. Hence, it is recommended to introduce CWM module to the foodservices industry to better assimilate CWM knowledge to the practitioners as well as the public.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This project was approved by Sunway University Research Ethics Committee (Ethic no.: SUREC 2021/072).

Authors’ contributions

PVS, CCY, SLW, MKA and GLT contributed to conception and design of the study. PVS drafted the module, PVS and CCY conducted the experiment, CCY, SLW and LTG performed the data analysis. PVS, CCY, SLW, EB, MKA and LTG supervised the project. CCY, SLW, EB, and LTG drafted the manuscript. PVS, CCY, MKA and LTG funding acquisition

Appendices Clean.docx

Download MS Word (25.3 KB)Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank research assistants, teaching chefs, culinary students and cleaners that have participated in this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request due to ethical and legal reasons

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Chin Choo Yap

Chin Choo Yap is a health psychologist by training. She began her career in Malaysia in the late 1990s as a professional counsellor upon completion of her bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the United States of America. With the conviction that education is the best approach to develop healthy minds and reduce psychological issues, she set foot in tertiary institutions to work with emerging adults directly at the capacity of Sunway University. She then took a four-year break to embark on her postgraduate studies obtained her doctorate degree from Monash University. She re-embarked on her career path with Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman and now Sunway University. Her research interests revolve around health-promoting behaviour modification and personal wellbeing in the areas of psychology and planetary health.

Shin Ling Wu

Shin Ling Wu is currently a faculty member in the Department of Psychology at Sunway University, Malaysia. She earned both her bachelor’s degree in Human Development and her doctorate in Psychology of Child Development from Universiti Putra Malaysia. Her research focuses on mental health and suicidal phenomena, parenting, Positive Psychology, and Social Psychology.

Pau Voon Soon

Pau Voon Soon is a multi-award cook book Author on the subject of Food Upcycling, Food Security and Food Heritage. As a Culinary Educator, he pioneered the delivery of Worldchefs’ Sustainability Education for Culinary Professional programme. As a Professional Chef; he has lead the Malaysia National Youth Culinary Team in winning Gold and Silver at the Culinary Olympics, Stutgart 2020. He is currently Teaching Fellow at the School of Hospitality and Service Management as well as the Secretary General for the Professional Culinaire Association, Malaysia.

Elizaveta Berezina

Elizaveta Berezina is a Senior Lecturer in Psychology at Sunway University, Department of Medical and Life Sciences, and joined the Department in March 2017 after several years working as a Senior Lecturer in Singapore. Dr. Berezina obtained her Doctoral degrees in Psychology at Moscow State University, Russia and worked as a Researcher at the Russian National Research Centre on Drug Addiction. She was also holding a post of Programme Manager with the Centre for Social Development and Information, where she was responsible for managing HIV-prevention programmes in Russia. After dedicating more than seven years to implementing health-related prevention programs with hard-to-reach populations, she returned full time to academia where her research interests include health promotion among youth, behavioural change techniques, personality and well-being. Since January 2022 Dr. Berezina has been Programme Leader for BSc (Hons) Psychology at Sunway University, managing a cohort of more than 500 students. Dr. Berezina is a member of the European Association of Social Psychology, the British Psychological Society, and the International Society of Critical Health Psychology.

Mohamed Kheireddine Aroua

Mohamed Kheireddine Aroua completed his PhD (Analytical Chemistry) in 1992 at the University of Nancy 1, France. His research addresses the fundamental and technical issues related to water, energy, and environment. He is interested in developing green solvents, sorbents and processes for CO2 capture and utilization; treatment of water and wastewater using novel adsorbents and advanced electrochemical processes. His research has generated more than 250 articles in ISI-ranked journals and over 25,000 citations, and his h-index is 78 according to Google Scholar database. He was listed by Clarivate Analytics as top 1% highly cited researcher in 2018 and 2019. He is also recognized in Stanford University list as top 2% world scientist for career-long as well as single-year impacts in 2019,2020, 2021, and 2022.

Lai Ti Gew

Lai Ti Gew is an associate professor at Sunway University School of Medical and Life Sciences. Dr Gew earned her PhD in Chemistry at University of Malaya, Malaysia. She is actively involved in research activities that are in-line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals by using and developing new green and safe alternative processes and chemicals. She is also passionate and committed to understand and address plastic pollution issues to achieve a sustainable world through change in policy and social structure. One of the highlights of her research career was the discovery of microplastics in edible sea salt in 2019. The research findings were featured in The Star newspapers, The Petri Dish and various websites. In her course of research and study, Dr Gew has received several awards namely “Outstanding Women in Science (Chemistry) by Venus International Women Awards, Chennai, Bentham Ambassador (since 2019 to date) and the “SSHN (High level Scientific Stay) Scholarship for Young Researcher” by France Embassy in Malaysia. In her line of research and study, Dr Gew has published research papers in prominent research journals and has demonstrated her commitment and dedication which are evident through her works with numerous research partners and grants.

References

- Ahmed, M., Guo, Q., Qureshi, M. A., Raza, S. A., Khan, K. A., & Salam, J. (2021). Do green HR practices enhance green motivation and proactive environmental management maturity in hotel industry? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102852

- Amicarelli, V., Aluculesei, A.-C., Lagioia, G., Pamfilie, R., & Bux, C. (2021). How to manage and minimize food waste in the hotel industry: An exploratory research. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 16ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print). (1), 152–167. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-01-2021-0019

- Arrigoni, J. P., Paladino, G. L., Garibaldi, L. A., & Laos, F. (2018). Inside the small-scale composting of kitchen and garden wastes: Thermal performance and stratification effect in vertical compost bins. Waste Management , (76), 284–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2018.03.010

- Betz, A., Buchli, J., Göbel, C., & Müller, C. (2015). Food waste in the Swiss food service industry – Magnitude and potential for reduction. Waste Management , 35, 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2014.09.015

- Buzby, J. (2022, January 24). Food Waste and its Links to Greenhouse Gases and Climate Change. https://www.usda.gov/media/blog/2022/01/24/food-waste-and-its-links-greenhouse-gases-and-climate-change#:∼:text=EPA%20estimated%20that%20each%20year

- Cheng, K., Koo, A. C., Nasir, J. S. B. M., & Wong, S. Y. (2022). An evaluation of online Edcraft gamified learning (Egl) to understand motivation and intention of recycling among youth. Science Report, 1(12) https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-15709-2

- Cheng, K. M., Tan, J. Y., Wong, S. Y., Koo, A. C., & Amir Sharji, E. (2022). A review of future household waste management for sustainable environment in Malaysian cities. Sustainability, 14(11), 6517. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116517

- Chia, D., Yap, C. C., Wu, S. L., Berezina, E., Aroua, M. K., & Gew, L. T. (2023). A systematic review of country-specific drivers and barriers to household food waste reduction and prevention. Waste Management & Research: The Journal of the International Solid Wastes and Public Cleansing Association, ISWA, 42(6), 459–475. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X231187559

- Denzin, N. K., Lincoln, Y. S., Giardina, M. D., & Cannella, G. S. (Eds.) (2024). The Sage handbook of qualitative research. (6th ed.). Sage Publications Ltd.

- FAO & WFP. (2022). Hunger Hotspots: FAO-WFP early warnings on acute food insecurity, October 2022 to January 2023 Outlook - World | ReliefWeb. Reliefweb.int. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/hunger-hotspots-fao-wfp-early-warnings-acute-food-insecurity-october-2022-january-2023-outlook

- Filimonau, V., Todorova, E., Mzembe, A., Sauer, L., & Yankholmes, A. (2020a). A comparative study of food waste management in full-service restaurants of the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Journal of Cleaner Production, 258, 120775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120775

- Filimonau, V., Zhang, H., & Wang, L. (2020b). Food waste management in Shanghai full-service restaurants: A senior managers’ perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 258, 120975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120975

- Global Report on Food Crises. (2022). World Food Programme, 2022, May 4, https://www.wfp.org/publications/global-report-food-crises-2022

- Goh, E., & Jie, F. (2019). To waste or not to waste: Exploring motivational factors of Generation Z hospitality employees towards food wastage in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 80, 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.02.005

- Goh, E., Okumus, B., Jie, F., Djajadikerta, H., & Lemy, D. (2022). Managing food wastage in hotels: Discrepancies between injunctive and descriptive norms amongst hotel food and beverage managers. British Food Journal, 124(12), 4666–4685. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-05-2021-0513

- Hamzah, N. H. C., Sanusi, A., Khairuddin, N., Azman, N. S., & Lahuri, A. H,. (2022). Public practice, knowledge and attitude on managing kitchen and food wastes in Bintulu, Sarawak, Malaysia. International Journal of Environmental Science and Development, 13(4), 118–123. https://doi.org/10.18178/ijesd.2022.13.4.1381

- Hani, A. (2022). Malaysia throws away 17,000 tonnes of food daily. The Malaysian Reserve. https://themalaysianreserve.com/2022/02/15/malaysia-throws-away-17000-tonnes-of-food-daily/

- Izan, J., Tengku Azmina, I., Noor Hayati, M. I., & Nor Syuhada, M. Z. (2017). Waste audit in UMT campus: Generation and management of waste in cafeteria and food kiosk. Journal of BIMP-RAGA Regional Development, 3(1), 84–94. https://doi.org/10.51200/jbimpeagard.v3i1.1033

- Kaur, P., Dhir, A., Talwar, S., & Alrasheedy, M. (2021). Systematic literature review of food waste in educational institutions: Setting the research agenda. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(4), 1160–1193. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-07-2020-0672

- Obersteiner, G., Gollnow, S., Boer, E., Sándor, R. (2021). . Enhancement of food waste management and its environmental consequences. Energies, 14(6), 1790. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14061790

- Papargyropoulou, E., Steinberger, J. K., Wright, N., Lozano, R., Padfield, R., & Ujang, Z. (2019). Patterns and causes of food waste in the hospitality and food service sector: Food waste prevention insights from Malaysia. Sustainability, 11(21), 6016. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216016

- Principato, L., Pratesi, C. A., & Secondi, L. (2018). Towards zero waste: An exploratory study on restaurant managers. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 74(1), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.02.022

- Roy, P., Mohanty, A. K., Dick, P., & Misra, M. (2023). A review on the challenges and choices for food waste valorization: Environmental and economic impacts. ACS Environmental Au, 3(2), 58–75. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenvironau.2c00050

- Saalah, S., Rajin, M., Yaser, A. Z., Azmi, N. A. S., & Mohammad, A. F. F. (2020). Food waste composting at faculty of Engineering, Universiti Malaysia Sabah. In Yaser, A. (Eds), Green engineering for campus sustainability. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-7260-5_13

- Sakaguchi, L., Pak, N., & Potts, M. D. (2018). Tackling the issue of food waste in restaurants: Options for measurement method, reduction and behavioral change. Journal of Cleaner Production, 180(10), 430–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.136

- Samsuddin, Z., Zainal, N. A. M., Sulong, S. N., & Bakar, A. M. F. A. (2022). Handling Food Waste in The Hotel Industry. Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 7(11), e001926–e001926. https://doi.org/10.47405/mjssh.v7i11.1926

- Soliman, S. E. (2020). Food waste management: Exploratory study of Egyptians chefs. Journal of Association of Arab Universities for Tourism and Hospitality, 18(3), 177–198. https://doi.org/10.21608/jaauth.2020.34793.1040

- Sulewski, P., Kais, K., Gołaś, M., Rawa, G., Urbańska, K., & Wąs, A. (2021). Home bio-waste composting for the circular economy. Energies, 14(19), 6164. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14196164

- Sun, W., Shahrajabian, M., & Cheng, Q. (2021). Organic waste utilization and urban food waste composting strategies in China - A review. Notulae Scientia Biologicae, 13(2), 10881. https://doi.org/10.15835/nsb13210881

- Taib Ali, R., & D’cruz, C. C. (2022). Challenges and management of restaurant waste in Shah Alam. Journal of Management & Science, 20(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.57002/jms.v20i1.206

- The ASEAN Secretariat Jakarta. (2022). ASEAN Regional Guidelines for Sustainable Agriculture in ASEAN: Developing Food Security and Food Productivity in ASEAN with Sustainable and Circular Agriculture. https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/2023_App-1.-ASEAN-Regional-Guidelines-for-Sustainable-Agriculture_adopted.pdf

- Thi, N. B. D.,Kumar, G., &Lin, C.-Y. (2015). An overview of food waste management in developing countries: Current status and future perspective. Journal of Environmental Management, 157, 220–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.04.022 25910976

- World Food Programme. (2020, June 2). 5 facts about food waste and hunger | World Food Programme. www.wfp.org. https://www.wfp.org/stories/5-facts-about-food-waste-and-hunger

- Wu, X., Fan, X., Xu, T., & Li, J. C. (2020). Emergency Preparedness and Response to African Swine Fever in The People’s Republic of China. Revue Scientifique et Technique (International Office of Epizootics), 39(2), 591–598.), https://doi.org/10.20506/rst.39.2.3109

- Yuan, Y., Nomura, H., Takahashi, Y., & Yabe, M. (2016). Model of Chinese household culinary waste separation behavior: A case study in Beijing City. Sustainability, 8(10), 1083.), https://doi.org/10.3390/su8101083

- Yusuf, R., & Fajri, I. (2022). Differences in behavior, engagement and environmental knowledge on waste management for science and social students through the campus program. Heliyon, 8(2), e08912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08912