Abstract

Social entrepreneurship (SE) strategic literature is in an under-theorized condition for large-scale strategy setting and classification. However, the research intends to fill the gap by proposing a literature-supported governmental-scale SE strategic grid. Thus, a systematic SE literature review was conducted up to getting four core strategic orientations of Externalism vs. Internalism, and Governmentalism vs. Volunteerism. Accompanied with a study of large-scale SE strategic partnerships by local, global, national and international social enterprises, four patterns of partnership (hence, dimensionality) within Localism vs. Globalism, and Nationalism vs. Internationalism were emerged. Later, the orientations and dimensions were corroborated based on the officially released documents of 15 governments, selected randomly in three economic classes, based on the recent UN’s triad economic classification. Next, four comprehensive SE strategic classifications of Global Citizen Strategy, Opened Door Strategy, Closed Door Strategy, and Country Citizen Strategy were recognized. Finally, combining the classified strategies with their orientations and dimensions on a visualized framework led to an ultimate comprehensive SE strategic grid. The implications of the grid are its potential consensus making effect not only among SE strategists on the governmental scale but also in the academic settings.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The role of government in our daily life and social welfare is pivotal. However, still there is not any consensus among public sector’s strategists and policymakers on the factors that should be taken into consideration for setting public welfare strategies. This paper not only paves the way for the formation of the consensus but also helps the public strategists to classify the social welfare strategies within a coherent grid to be able to set and customize far-reaching social entrepreneurship strategies according to public needs.

Competing interests

The authors claim that they have no conflict of interest to be cited here.

1. Introduction

Some of the world-renowned schools of public affairs and administration are now teaching some courses on SE and it has “a growing presence in U.S. public affairs programs” (Wiley & Berry, Citation2015, p. 381). Public affairs and their administration are embedded in a larger social structure. Social structure as, “patterned social relations—those regular and repetitive aspects of the interactions between the members of a given social entity” (Wilterdink & Form, Citation2018, p. 1) could be affected by macro-scale SE. Moreover, “social structure is often treated together with the concept of social change, which deals with the forces that change the social structure and the organization of society” (Wilterdink & Form, Citation2018, p. 1). SE, which could be defined as “a socially mission-oriented innovation which seeks beneficial transformative social change by creativity and recognition of social opportunities in any sectors” (Forouharfar, Rowshan, & Salarzehi, Citation2018, p. 33), has a capacity to be seen as core governmental strategy for promoting public welfare, eradicating or relieving social pains and changing the overall social structure for the better. Thus, social entrepreneurs as communal and urban change makers (Adetu, Citation2014; Dees, Emerson, & Economy, Citation2002; Drayton, Citation2002; Robinson, Joshi, Vickerie-Dearman, & Inouye, Citation2019) have the capability of contributing states to promote socially benefiting initiatives, innovations and enterprises under well-defined state strategies. However, public SE strategies are insufficiently theoretically studied and still do not have any well-formed strategic epistemology for classifying, setting and formulating (Forouharfar, Citation2018). Therefore, to fill the current gap the following research question is posed:

What recurring systematic SE-literature-reviewed components constitute a strategic grid to visualize classification, orientation and dimensionality in the current governmental-scale SE strategic paradigms?

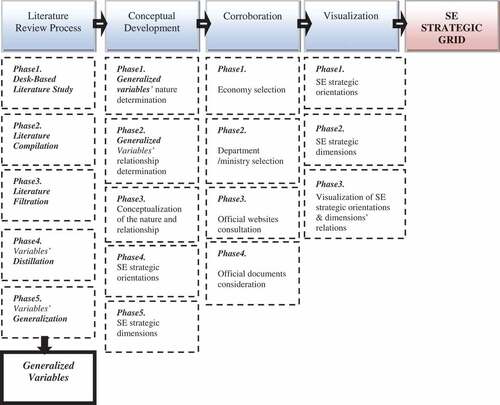

Based on the research question a five-step process (literature review, conceptual development, corroboration, nature and relationship visualization, and ultimate grid composition) was carried out to reach the intended visualization of governmental-scale SE strategic classification, orientation and dimensionality. The steps start with the literature review in the following.

2. Literature

SE literature is “a rather fragmented literature without dominant frameworks” (Saebi, Foss, & Linder, Citation2019, p. 70). Not only strategic entrepreneurship is still “an emerging concept” (Kuratko & Audretsch, Citation2017, p. 1) but also social entrepreneurship is a “pre-paradigmatic” phenomenon (Lehner & Kansikas, Citation2013, p. 198) “in the stage of conceptualization” (Sekliuckiene & Kisielius, Citation2015, p. 1015). Thus, “SE strategies remain poorly understood” (Chandra, Jiang, & Wang, Citation2016, p. 1). Although, numerous attempts were made from “conceptual understanding” of SE itself (Choi & Majumdar, Citation2014, p. 363) to the conceptualization of social entrepreneurs’ behavioral characteristics (Weerawardena & Mort, Citation2006), there is not enough study on conceptualizing SE in the public sector. Mort, Weerawardena and Carnegie (2002, p. 76) “conceptualises social entrepreneurship as a multidimensional construct involving the expression of entrepreneurially virtuous behaviour to achieve the social mission, a coherent unity of purpose and action in the face of moral complexity, the ability to recognise social value‐creating opportunities and key decision‐making characteristics of innovativeness, proactiveness and risk‐taking.” However, a few have ever set forth to conceptualize strategic SE. A research gap that calls for strenuous efforts to be filled. Chandra, Jiang and Wang (Citation2016, p. 1) believe, “Despite the burgeoning research on social entrepreneurship (SE), SE strategies remain poorly understood.”

According to Dharani (Citation2014, p. xi) “conceptualization is the formation of an abstract principle in the mind of a researcher in order to answer the question under observation, basing it upon the available evidence.” By reviewing SE strategic literature we frequently face concepts such as social value making (Nicholls, Citation2008), social innovation (Mulgan, Citation2006), strategic social impact (Rawhouser, Cummings, & Newbert, Citation2019); social mission (Forouharfar, Citation2018); volunteerism (Gandhi & Raina, Citation2018); impact scaling (Dees, Citation2008), etc. Therefore, any literature-based conceptualization of strategic SE should be constructed upon the extraction of the most unanimous and frequent concepts in this realm. Although, numerous researchers have tried to conceptualize various strategic manifestations of entrepreneurship, e.g. from “developing a conceptual framework of strategic entrepreneurship” itself (Luke, Kearins, & Verreynne, Citation2011, p. 314) to “conceptualizing corporate entrepreneurship strategy” (Ireland, Covin, & Kuratko, Citation2009, p. 19), the realm of strategic SE is under-conceptualized. Thus, one of the attempts in the conceptualization of strategic SE was Customized SE Strategy, which intends the sustainable development of any country via customized and tailored SE practices, based on the priorities of each country’s social problems (Rowshan & Forouharfar, Citation2014).

On the other hand, in the strategic approach to SE, at least two levels are identifiable: a macro-level and a micro-level. According to Nicholls (Citation2009) these arenas of SE embrace a vast spectrum from a macro interference to compensate the gaps in “institutional voids” (e.g. BRAC and Grameen Bank) or micro customized technical solutions to local communities (e.g. Kickstart’s East Africa low-priced marketing of water pumps). Concerning the macro-level, SE has the capability of a social movement or a strong force behind “societal cognitive frames” which are in “sub-optimal” (or below satisfactory) circumstances and makes a satisfactory change by generating innovation on “macro-political level” (Zald, Citation2000; Zald & Davis, Citation2005). According to Forouharfar (Citation2018):

SE in the public sector is on a macro level. Governments have regulatory and policy-making roles and they could have a facilitating role for SE, as well. In other words, they pave the way for the not-for-profits, NGOs, social enterprises, benevolent entrepreneurs, etc. to play in the playground field, which is beaten and prepared by the governments. Therefore, two types of strategies could be seen in SE. One type is the macro-strategies, which are applied by the governments and the other are the micro-strategies used by the operational social entrepreneurs. (p. 192)

Replication strategies and Scaling strategies are two major classes of SE strategies (Bloom & Smith, Citation2010; Tracey & Jarvis, Citation2007). Replication is “the process by which a cell or DNA makes an exact copy of itself” (Longman Dictionary, Citation2007, p. 1341). In the strategic SE, it is letting the other SE enterprises exactly copy the successful approach and techniques of a recognized example of a previous SE. Scaling in strategic SE focuses on the amplification of the impact of SE, i.e. increasing the SE impact to be as equal as the social problem in degree and magnitude (Dees, Citation2008) to guarantee that great number of people will receive the social services (Ahlert et al., Citation2008). Researchers (e.g. Dees, Anderson, & Wei-Skillern, Citation2004; Grieco, Citation2015; London & Hart, Citation2011; Manton, Citation2005; Volkmann, Tokarski, & Ernst, Citation2012) have identified the following scaling and/or replication strategies:

(1) Dissemination Strategy, (2) Social Affiliation Strategies, (3) Social Joint Venture Strategy, (4) Social Licensing Strategy, (5) Social Franchise Strategy, (6) Social Price-Differentiation Strategy, (7) Social Cross-Subsidization Strategy, (8) Social Microfinance Strategy, and (9) Base-of-the-Pyramid Strategy.

Governments have a key role in operationalizing SE strategies on a large-scale public size with countrywide impact. Shockley and Frank (Citation2011, p. 181) believe: “[…] little or no social change resulting from social entrepreneurship could have become ‘large‐scale’ without the enabling institutions, resources, and policies of government, even ones with reputations for inefficiency or corruption.” While discussing “government as problem solver,” Dees (Citation2007, p. 25) truly accentuates that, “it has become clear that large-scale, top-down government programs have serious drawbacks.” Yet, governments should set national SE strategies and avoid propensity of socialist governments, that is too much intervention in SE affairs.

Volunteerism is a recurring occurrence in strategic SE; since “social enterprises often rely upon volunteers to serve key functions, such as board members, to help with fundraising or to provide professional services, or as staff to deliver their services on the ground” (Austin, Stevenson, & Wei-Skillern, Citation2012, p. 377). “Volunteering is any activity in which time is given freely to benefit another person, group or cause” (Wilson, Citation2000, p. 215). The ILO’s official manual defines it as: “Unpaid non-compulsory work; that is, time individuals give without pay to activities performed either through an organization or directly for others outside their own household” (International Labour Office [ILO], Citation2011, p. 3) and the United Nations [UN] (Citation2003, p. 4) as “work without monetary pay or legal obligation provided for persons living outside the volunteer’s household”. Besides, social activism and volunteering are related concepts in sociology (Wilson, Citation2000) which add to the sociological aspect of strategic SE.

Moreover, a resource-based view in strategic management; hence strategic SE, looks inwards or internally. Too much insistence on strategic resource-based view would potentially lead to halo effect in strategic SE. Zander and Zander (Citation2005, p. 1523) asserts, “Extensions of the resource‐based view suggest that the inward‐looking perspective has produced an overly narrow understanding of how firms may generate rents and secure long‐term growth.” Concerning SE, Cheah, Amran, and Yahya (Citation2019, p. 607) believe “Internal oriented resources (i.e., entrepreneurial orientation, social salience and business planning)” under the moderating effect of “socio-economic context” could influence the social performance and financial achievement of social enterprises. In contrary, instead of looking inwardly, some countries benefit from international SE organizations (Forouharfar, Citation2018) and “international for-profit social entrepreneurs” (Marshall, Citation2011, p. 183). Usually governments have close cooperation and partnership in resources with the UN, UNHCR, UNESCO, UNDP, GEM, ECOSOC, World Bank, World Economic Forum, and world-famous SE organizations such as Ashoka, Schwab, Skoll, for the promotion of SE locally or globally. Bricolage as “a key theoretical frame for understanding how social entrepreneurs mobilize and deploy resources to create social value under situations of resource scarcity” (Langevang & Namatovu, Citation2019, p. 1) is one of the reasons behind SE strategic partnerships. These international SE organizations usually have a strategic usage of bricolage in order to mobilize their resources in the target countries (Desa, Citation2012).

3. Research design and methodology

This paper is a non-empirical secondary-data study of large-scale SE strategies with the intention of conceptualizing, classifying, and systematizing them in a visualized comprehensive strategic grid. As a conceptual paper the research goal is to go “beyond summarizing recent research, […] provide an integration of literatures, offer an integrated framework, provide value added, and highlight directions for future inquiry. […] not expected to offer empirical data” (Gilson & Goldberg, Citation2015, p. 127). Thus, by reviewing the highly cited literature on SE strategies, the study shapes integration of SE large-scale strategy literature in visualization. Hence, the integration to the authors means unification and consolidation of the large-scale SE in a logically literature-supported grid to provide conceptual value addition for the future classification and accordingly discussion of state-sponsored SE. As, a conceptual paper should be judged and formed at least based on seven criteria: “(a) What’s new? (b) So what? (c) Why so? (d) Well done? (e) Done well? (f) Why now? and (g) Who cares?” (Whetten, Citation1989, pp. 494–495); here, (a) the newness lies in systematizing the governmental-scale SE strategies; (b) it introduces a framework for the strategic classification of macro-scale SE; (c) the underlying logic is filling the current research gap in strategic SE studies; (d) the completeness of the conceptualized framework rests in its reliance on relevant highly-cited literature; (e) the paper is shaped gradually based on a methodological flowchart presented in Figure ; (f) the timeliness and necessity of such a study lies in coordinating SE researches with facts on the ground, since “A literature review of research on social entrepreneurship reveals that academics and practitioners seem to be operating in separate spheres” (Hand, Citation2016); and finally, (g) the paper potentially not only contributes to the state policymakers in the matters relevant to SE, but also makes a linkage between SE and public administration, that is the type of SE strategies which could be applied in the realm of public administration.

Generalization phase of the literature review process has a pivotal role in the research methodological flowchart. In reality, SE variables differ across regions and cultures. This characteristic of SE variables is called embeddedness. The small-scale variables of SE are deeply ingrained and embedded in the geographical locations and local communities (Kistruck & Beamish, Citation2010; Seelos, Mair, Battilana, & Tina Dacin, Citation2011; Smith & Stevens, Citation2010; Wang & Altinay, Citation2012). The Localism dimension of the grid intends to reflect this feature. However, large-scale variables of SE share some common unifying features, which are generalized in the strategic orientations and reflected in the ultimate strategic grid; otherwise, the formation of the grid was not possible. Such an approach systematically brings out and generalizes what Hill, Kothari, and Shea (Citation2010, p. 5) have called “patterns of meaning in the social entrepreneurship literature.” On the other hand, logical pondering on the three closely related concepts of strategic management (strategy, policy and tactic) justifies the generalization approach (Table ). According to Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (Citation2002) strategy, derived from Strategia in Greek, is “the art of devising or employing plans or stratagem toward a goal (p. 1162); policy, derived from Politia in Latin, is “a high-level overall plan embracing the general goals and acceptable procedures, esp. of a governmental body” (p. 901); and tactic, derived from Tactica in Latin, is “a device for accomplishing an end” (p. 1200). These levels convert a totally abstract, relevant but general decision (strategy) to a semi-abstract principle (policy) through operationalized arrangements and maneuvering actions (tactics) to reach pre-defined strategic goals, missions and visions. The above concepts in this three-storied hierarchy of the conversion of abstract to concrete are more abstract and general, and comparatively the below concepts are more concrete and operational.

Table 1. The strategic conversional hierarchy: process of operationalizing abstract strategies to concrete tactics

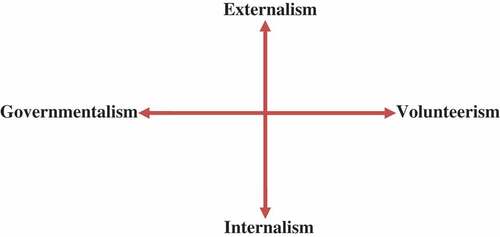

3.1. SE strategic orientations

The research data are secondary non-empirical data since they are collected by desk-based approach. The research question determined the literature context; hence, SE strategies. Furthermore, “strategic orientation is an important consideration since it impacts the activities and resource allocations of a venture that can influence its performance” (Scillitoe, Poonamallee, & Joy, Citation2018, p. 257). Thus, the literature on SE strategies was reviewed in five phases to reach SE strategic orientations (Table ). The outcome was the generalization of the variables in the following orientations:

Table 2. Systematic approach in reviewing strategic SE literature

(1) Governmentalism; (2) Volunteerism; (3) Externalism; and (4) Internalism.

Table has summarized the complete literature review process to reach the grid “Generalized Variables”.

Table 3. Literature review process

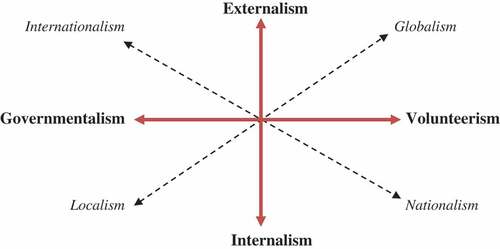

3.2. SE strategic dimensions (partnerships)

Partnership is a pivotal concept not only in overall strategic management but also especially in SE strategies (Choi, Citation2015; Smith, Meyskens, & Wilson, Citation2014). “The value of networks and collaboration” is empirically proved to be a significant factor in strategic SE; largely for SE impact investment strategies (Ormiston, Charlton, Donald, & Seymour, Citation2015, p. 352). “Collective social entrepreneurship” accentuates cross-sectoral collaborations and alliances (Montgomery, Dacin, & Dacin, Citation2012, p. 375). Dimensionality in this research reflects the directionality of such large-scale partnerships and collaborations. I.e. in some cases at the operational level, there are some large-scale SE strategies, which simultaneously or singly pursue local or global, national or international goals through cooperation or partnership with local, global, national or/and international social enterprises (e.g. “for-profit and not-for-profit social enterprises” generally show “internationalization behavior” (Yang & Wu, Citation2015, p. 31). Dimensions on the grid could be pursued unidirectionally, bidirectionally, tridirectionally or in every four directions (dimensions). By reviewing the operational and active SE enterprises, summarized in Table , the following macro-scale dimensions (partnering tendencies) were emerged:

Table 4. Large-scale partnership examples

(1) Internationalism; (2) Nationalism; (3) Globalism; and (4) Localism

Since both the orientations, Governmentalism/Volunteerism and Externalism/Internalism, and the dimensions (partnerships), Localism/Globalism, and Nationalism/Internationalism, have contrary natures, and then they stand at either extreme, that is logically they must have inverse or negative correlative relationship. I.e., by the increase in one of the extremes there should be a decrease in the other. Therefore, the generalized variables must have logically inverse correlation, which could be presented on coordinate axes (Table ).

Table 5. Grid development components

3.3. Corroboration of the SE orientations and dimensionsFootnote15

Entrepreneurship is an economic theory. Its social orientation, SE, also deals with the social economy of each geographical region or state. “The social economy is a sector of the market which operates between the public and the private sphere;” and “[…] a universally accepted definition of the social economy still does not exist” (Liger, Stefan, & Britton, Citation2016, p. 7). However, it includes a large group of organizations embedded within the national economies such as social enterprises, mutual societies, not-for-profit organizations, charities and the foundations, which are active in the third sector. Since the paper aims to introduce a SE strategic grid for the governmental-scale SE strategies, it needs reliable and comprehensive sampling of world economies to be able to corroborate the grid. To accomplish the task the authors relied on the recent UN report, the World Economic Situation and Prospects 2019. Although Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), as one of the most reliable global bodies in charge of global entrepreneurship study and statistics, has issued two reports in 2009 and 2016 on SE, they are dated for the year 2019, since economy is always in a state of flux. Based on the UN’s economic classification in the World Economic Situation and Prospects (Citation2019, p. 169–170), 15 economies (5 from each class of “developed economies,” “economies in transition,” and “developing economies”) were selected. Then, the most recent official documents and publication of the 15 governments were read to complete Table . The main programs in the table were selected based on the officially-stated public budget spending on the SE/social welfare program(s). Collecting SE strategic corroborating data in Table was easier in “developed economies”. These governments are mainly following Open Government Policy. Through this policy, e.g. in Canada, “In 2016, the Government of Canada announced its intent to revitalize the Access to Information Act in a two-phased approach; first through targeted legislative changes to improve the Access to Information Act, followed by a full review of the Act by no later than 2018, and every five years thereafter” (Departmental Plan, Citation2018-2019, p. 55). The governmental bodies/ministries or departments in charge of SE strategy setting and planning in these governments also follow the policy (e.g. in Canada, “ESDCFootnote16 is collaborating on the government-wide priority of revitalizing the Access to Information Act and Privacy Act reform” (Departmental Plan, Citation2018–2019, p. 55). The policy and data made corroboration step possible. Hence, to reflect the official SE strategic views, merely the data from the official government websites, publications of each governmental body, and the national and officially-approved and -funded studies were collected in Table .

Table 6. Corroboration of the emerged SE strategic orientations and dimensions

One of the major aspects of the concept of Governmentalism is the regulatory aspect of the governments. Regulatory aspects of the governments play a major role in determining the choice of entry and operations of social enterprises (Kelley, Citation2009) as well as their incubations (Bhamoriya, Sinha, & Golwa, Citation2014). Even the conception and perception of social enterprise and its social functions in the European and American contexts are different (Kerlin, Citation2006), and generally there is a universal “lack of a common understanding of social enterprise” (Galera & Borzaga, Citation2009, p. 210). Therefore, governments do not have universal regulatory measures toward social enterprises. Hence, Governmentalism, and its impact in the promotion of state social enterprises and SE, is a context-related orientation (e.g. there are multiple and different legal forms and definitions for social enterprises in the U.S. and Europe, and “ … at least fifteen European Union member states have specific laws for social enterprise” (Fici, Citation2016, p. 639). In sum, the state’s regulatory measures for social enterprises is a double-edged sword which could bring “opportunity or confusion” to the social enterprises (Snaith, Citation2007, p. 20).

4. Results and discussion

The Literature Review Process yielded the generalized variables of the research, which turned into the following strategic orientations and visualization (Figure ):

Degree of Externalism, i.e. how much the government intends to rely on international social organizations to implement its strategies.

Degree of Internalism, i.e. how much the government intends to rely on national organizations, resources and capabilities for the SE strategy implementation.

Degree of Governmentalism, i.e. How much the government intends to interfere and meddle with the SE implementation.

Degree of Volunteerism, i.e. how much the government lets the NGOs, SEOs and volunteers do the job.

After that, the study of the large-scale SE practices via partnerships, asserted by the governments and social enterprises (Table ), shed light on the strategic dimensions. The following dimensions determine the types and visualization (Figure ) of most recurring and potential partnerships (e.g. the potential strategic partnership between the orientations of Governmentalism and Externalism, would be Internationalism):

Internationalism, i.e. a mutual collaboration between a governmental body and a foreign-based SE entity.

Nationalism, i.e. a mutual collaboration between a volunteering organization/people and a domestic SE entity.

Globalism, i.e. a mutual collaboration between a volunteering organization/people and a foreign-based SE entity.

Localism, i.e. a mutual collaboration between a governmental body and a domestic SE entity.

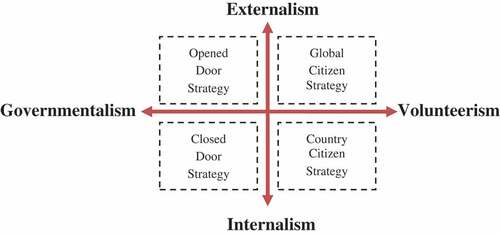

Moreover, based on the interplay of the two by two contrary in nature orientational variables, which logically in visualization were placed at either extreme, i.e. logically they must have inverse or negative correlative relationship, four classes of state-promoted SE are possible (Figure ).

The Horizontal axis (Governmentalism-Volunteerism axis) with Externalist orientation indicates promotion of SE within the state with extraterritoriality in resource-based view; that is benefiting from global/international resources for large-scale SE promotion. On the contrary, Governmentalism-Volunteerism axis with Internalist orientation seeks SE via intra-territorial view to the resources; i.e. benefiting from the local or national resources of the state. Therefore, the following “Opened Door Strategy” and “Global Citizen Strategy” indicate extraterritoriality in resources and partnership:

If a state pursues SE by close cooperation between the government and extraterritorially global or international organizations/governments to answer social problems, it is a state-sponsored SE strategy which could be called “Opened Door Strategy”. Such a state tries to compensate its weak points and benefiting from extraterritorial resources by some SE strategies, such as social licensing strategy, social franchising strategy and social joint venture strategy. In “Opened Door Strategy” the social licensor, franchiser or partner is a foreign organization, social entrepreneur or even a foreign government/state. The government pursing “Opened Door Strategy” has chosen cooperative positioning in relation to the international and foreign partners.

In the most optimal state strategy for the promotion of SE, “Global Citizen Strategy” government functions as SE regulator and facilitator. It tries not to interfere overly in SE activities and trusts SE organizations and social entrepreneurs. Moreover, it respects volunteering activities and accepts global NGOs and SE entities as its partners and contributors not its rivals. These states choose cooperative positioning in dealing with active social entrepreneurs and in some cases proactive in dealing with future or emerging social problems. The proactive positioning of the government provides opportunities for global scientific counseling with the SE experts and accepting their criticisms. Additionally, these states usually choose one or several of scaling strategy, replication strategy, dissemination strategy and affiliation strategies to promote, scale up and replicate SE.

On the other hand, the following “Closed Door Strategy” and “Country Citizen Strategy” indicate intra-territoriality in resources and partnership:

The third class of state-sponsored strategies could be called “Closed Door Strategy”. If a government completely or partially limits any volunteer activity by NGOs, national and international social entrepreneurs and organizations and on the other hand, tries to have a tight monopoly on any SE activities, it pursues a strategy based on Governmentalist and Internalist orientations. Such a state is not eager to accept any cooperation, or if it accepts, it is from a limited number of local SE practitioners. The positioning of the government is mostly aggressive and in some cases, a defensive one since it does not trust mostly global or international partners. Since the government looks at the global/international organizations as its rivals, it could sometimes show competitive positioning too. States with “Closed Door Strategy” potentially could apply social microfinance strategy and show socialism/communism propensities toward SE.

In “Country Citizen Strategy” the state accepts Volunteerism but within and from the internal social entrepreneurs and SEOs. The state’s positioning toward SE promotion is defensive and in some cases by aggressive measures that limit the activity of global/international social entrepreneurs. Moreover, such strategies inevitably rely heavily on the national resources for the promotion of SE. Social price-differentiation strategy, social cross-subsidization strategy, social microfinance strategy and base-of-the-pyramid strategy could be classified within this class with two conditions, first if the government only accepts internal volunteers and second if it limits its interference with their activities as much as possible.

Ultimately by adding: a) the strategic orientations’ coordinate axis system; b) the strategic partnerships’ (dimensionalities) oblique coordinates; and c) the classified governmental-scale SE strategies on a grid the SE strategic grid visualization was shaped (Figure ).

The strategic orientations’ coordinate axis system is the undergirding foundation of the grid formation. Metaphorically, the coordinating axis functions as a strategic compass and the strategic orientations as its cardinal directions (N, S, E and W). Accordingly, the partnership oblique coordinates could be read as intercardinal directions (NE, NW, SE, SW) located halfway between each pair of SE strategic orientations. Finally, each rectangle on the grid defines the class of governmental-scale SE strategy or the destination that the pointer on the strategic compass shows.

5. Conclusion

Five steps of the research arranged in a way to narrow down the large stockpile of raw literature data on SE to a visualized SE strategic grid. The first step (literature review process) consisted of five systematic phases of variable study, compilation, filtration, distillation and generalization. The result of the initial step of the study was literature-supported generalized variables. Then operational large-scale SE partnerships were studied. The second step was carried out for conceptual development. To corroborate the acquired strategic orientations and partnerships (dimensions) with the facts on the ground, 15 economies and their governments in 3 economic classes were randomly selected in each class. In the third step, the official websites of each governmental body or agency in charge of the state-wide promotion of SE were carefully consulted in accordance with the previously derived orientations and partnerships. The corroboration step verified the results based on the governments’ released documents and their asserted active operations on SE. The fourth step visualized the relationships among the orientations together, and the partnerships with each other, and the two concurrently. This step made the classification of governmental-scale SE strategies possible. Ultimately, by the combination of the officially corroborated strategic orientations, partnerships and the author-defined strategic classifications on a single grid the finalized comprehensive SE strategic grid was visualized with 4 orientations, 4 dimensions and 4 SE strategic classifications. The four cardinal orientations of the grid (Governmentalism vs. Volunteerism, and Externalism vs. Internalism) define governmental intentions for the degree of reliance either on its own, or volunteers and external or internal resources and entities based on its defined missions and visions for fostering and promoting SE within the state. On the other hand, the four intercardinal dimensions (Internationalism vs. Nationalism, and Globalism vs. Localism) define the governmental nature of partnership with either international or national, and global or local active SE entities and enterprises unidirectionally or by taking the advantage of two or more simultaneous dimensions. Furthermore, the origin of the coordinating axes, where the axes meet, is the situation where a government has a passive role toward state SE. The non-existence of any orientations and dimensions indicates governmental SE passivism. The interplay of the orientations and dimensions help governments to define, formulate and set their SE strategies within the grid from a Global Citizen Strategy as the most cooperative, non-interfering and partnering strategy for the promotion of large-scale SE by governments to the least externally cooperative and full governmental meddling in the implementation of SE within a Closed Door Strategy. Additionally, the grid could contribute to the large-scale SE strategy fitting and customization based on the governmental plan for scaling or/and replicating SE impact within the state, the availability and compatibility of the government’s resources and facilities with the scale of the social work to be done and its successful operational accomplishment, and finally the degree of its reliance on partnering entities.

Acknowledgements

The authors like to show their heartfelt appreciation and gratitude for the editor, Dr. Pedro Lorca, and the scholarly comments and suggestions of three anonymous reviewers.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Amir Forouharfar

Amir Forouharfar is a Ph.D. candidate in Public Administration. His research interests are in the areas of public administration, strategic management, entrepreneurship, and political philosophy. He has authored more than 20 refereed papers and several book chapters. His recent project is contributing to Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance with several entries.

Seyed Aligholi Rowshan

Seyed Aligholi Rowshan is associate professor of Public Administration at University of Sistan and Baluchestan, Iran. He is the author of more than 50 refereed papers and several books. His research interests are mainly Critical Theory, strategic management, philosophy and qualitative methods of research. His recent book is on critical management studies.

Habibollah Salarzehi

Habibollah Salarzehi is associate professor of Public Administration at University of Sistan and Baluchestan, Iran. His research interests are mainly social and corporate entrepreneurship.

Notes

2. “It is funding tens of thousands of local, regional and national employment-related projects throughout Europe: from small projects run by neighborhood charities to help local disabled people find suitable work, to nationwide projects that promote vocational training among the whole population” http://ec.europa.eu/esf/main.jsp?catId=35&langId=en.

3. On 22/06/2018 “The European Investment Fund (EIF) signed a guarantee agreement for €50 million with seven member banks of the Erste Group … [to] support social entrepreneurship by providing financing to over 500 social enterprises in seven countries during the next five years, in the framework of the EU Program for Employment and Social Innovation (EaSI).” http://ec.europa.eu/esf/main.jsp?catId=67&langId=en&newsId=9144.

15. Via the SE data disseminated under Open Government Policies.

16. Employment and Social Development Canada.

17. https://www.ssa.gov/.

20. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/social-investment-and-social-entrepreneurship-in-the-uk.

25. “The Departmental Plan is an expenditure plan for Employment and Social Development Canada. The reports provide details on the Department’s main priorities over the next three years by core responsibilities and departmental indicators. It is tabled in Parliament in the spring of each year by the President of the Treasury Board.” https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/corporate/reports/departmental-plan.html.

34. “The Federal Republic of Germany is a democratic and social federal state” (Article 20 (1) of the German Basic Law).

51. Ibid.

52. Republic of Belarus law on “Demographic Security” of 4 January 2002 (National Register of Legal and Regulatory Acts, 2002г, No. 7, 2/829).

54. Ibid.

55. Ibid.

58. Ibid.

61. Part IV on Directive Principles of State Policy.

62. Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment annual report 2017–2018, http://socialjustice.nic.in/ViewData/?mid=76658.

66. Ibid.

67. Ibid.

References

- Adams, D. (2009). A social inclusion strategy for Tasmania (Appendix 1). Hobart: Department of Premier & Cabinet (Social Inclusion Unit).

- Adetu, S. (2014). AIESEC pursues social entrepreneurship for economic development. Retrieved from http://www.spyghana.com/aiesec-pursues-social-entrepreneurship-economic-development.

- Ahlert, D., Ahlert, M., DuonDinh, H. V., Fleisch, H., Heußler, T., Kilee, L., & Meuter, J. (2008). Social franchising: A way of systematic replication to increase social impact. Berlin: Bundesverb & DeutscherStiftungen.

- Alvord, S. H., Brown, L. D., & Letts, C. W. (2004). Social entrepreneurship and societal transformation: An exploratory study. Journal of Applied Behavioural Science, 40(3), 260–32. doi:10.1177/0021886304266847

- Anderson, B. B., & Dees, J. G. (2002). Developing viable earned income strategies. In J. G. Dees, J. Emerson, & P. Economy (Eds.), Strategic tools for social entrepreneurs: Enhancing the performance of your enterprising nonprofit. New York: Wiley.

- Austin, J., Stevenson, H., & Wei-Skillern, J. (2012). Social and commercial entrepreneurship: Same, different, or both? Revista de Administração, 47(3), 370–384. doi:10.5700/rausp

- Auvinet, C., & Lloret, A. (2015). Understanding social change through catalytic innovation: Empirical findings in Mexican social entrepreneurship. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration, 32(4), 238–251. doi:10.1002/cjas.1353

- Bacq, S., & Eddleston, K. A. (2018). A resource-based view of social entrepreneurship: How stewardship culture benefits scale of social impact. Journal of Business Ethics, 152(3), 589–611. doi:10.1007/s10551-016-3317-1

- Bacq, S., Ofstein, L. F., Kickul, J. R., & Gundry, L. K. (2015). Bricolage in social entrepreneurship: How creative resource mobilization fosters greater social impact. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 16(4), 283–289. doi:10.5367/ijei.2015.0198

- Battilana, J., Lee, M., Walker, J., & Dorsey, C. (2012, summer). In search of the hybrid ideal. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Retrieved from https://ssir.org/articles/entry/in_search_of_the_hybrid_ideal

- Berthon, P., McHulbert, J., & Pitt, L. (2004). Innovation or customer orientation? An empirical investigation. European Journal of Marketing, 38(9/10), 1065–1090. doi:10.1108/03090560410548870

- Bhamoriya, V., Sinha, P. K., & Golwa, A. (2014). The role of government regulation in incubating social enterprises (No. WP2014-03-10). Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad, Research and Publication Department.

- Bloom, P., & Smith, B. R. (2010). Identifying the drivers of social entrepreneurial impact: Theoretical development and an exploratory empirical test of SCALERS. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 126–145. doi:10.1080/19420670903458042

- Bloom, P. N., & Chatterji, A. K. (2009). Scaling social entrepreneurial impact. California Management Review, 51(3), 114–133. doi:10.2307/41166496

- Brouard, F., Hebb, T., & Madill, J. (2008). Development of a social enterprise typology in a Canadian context. Retrieved from https://carleton.ca/3ci/wp-content/uploads/SETypologyPaper2.pdf

- Bugg-Levine, A., Kogut, B., & Kulatilaka, N. (2012). Unbundling societal benefits and financial returns can dramatically increase investment. Harvard Business Review, 120–122.

- Chalmers, D. (2013). Social innovation: An exploration of the barriers faced by innovating organizations in the social economy. Local Economy, 28(1), 17–34. doi:10.1177/0269094212463677

- Chandra, Y., Jiang, L. C., & Wang, C. J. (2016). Mining social entrepreneurship strategies using topic modeling. PLoS One, 11(3), e0151342. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0151342

- Cheah, J., Amran, A., & Yahya, S. (2019). Internal oriented resources and social enterprises’ performance: How can social enterprises help themselves before helping others? Journal of Cleaner Production, 211, 607–619. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.203

- Choi, D., & Gray, E. (2008). The venture development processes of “sustainable” entrepreneurs. Management Research News, 8(31), 558–569. doi:10.1108/01409170810892127

- Choi, N., & Majumdar, S. (2014). Social entrepreneurship as an essentially contested concept: Opening a new avenue for systematic future research. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(3), 363–376. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.05.001

- Choi, Y. (2015). How partnerships affect the social performance of Korean social enterprises. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 6(3), 257–277. doi:10.1080/19420676.2014.965723

- Christiansen, C. (1997). The innovators’ dilemma. Cambridge: Harvard Business School Press.

- Cohen, B., & Winn, M. (2007). Market imperfections, opportunity and sustainable entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(1), 29–49. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.12.001

- Davis, S. (2016). Relocating development communication: Social entrepreneurship, international networking, and South-South cooperation in the viva Rio NGO. International Journal of Communication, 10, 18.

- Dawson, P., & Daniel, L. (2010). Understanding social innovation: A provisional framework. International Journal of Technology Management, 51(1), 9–21. doi:10.1504/IJTM.2010.033125

- Dees, G. J., Emerson, J., & Economy, P. (2002). Strategic tools for social entrepreneurs: Enhancing the performance of your enterprising nonprofit. New York: Wiley.

- Dees, J. G. (1998a). Enterprising nonprofits: What do you do when traditional sources of funding fall short? Harvard Business Review, January/February, 55–67.

- Dees, J. G. (1998b). The meaning of social entrepreneurship, (2001 Revision). Retrieved from https://entrepreneurship.duke.edu/news-item/the-meaning-of-social-entrepreneurship/

- Dees, J. G. (2007). Taking social entrepreneurship seriously. Society, 44(3), 24–31. doi:10.1007/BF02819936

- Dees, J. G. (2008). Developing the field of social entrepreneurship. Oxford: Center for the advancement of social entrepreneurship, Duke University.

- Dees, J. G., Anderson, B. B., & Wei-Skillern, J. (2004). Scaling social impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 1(4), 24–32.

- Departmental Plan. (2018–2019). Government of Canada, Cat. No.: Em1-10E-PDF. ISSN: 2371-7645. Retrieved from www.canada.ca/publicentre-ESDC

- Desa, G. (2012). Resource mobilization in international social entrepreneurship: Bricolage as a mechanism of institutional transformation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(4), 727–751. doi:10.1111/etap.2012.36.issue-4

- Dharani, K. (2014). The biology of thought: A neuronal mechanism in the generation of thought - A new molecular model. USA: Elsevier Science Publishing Co. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800900-0.00007-5

- Diochon, M. (2013). Social entrepreneurship and effectiveness in poverty alleviation: A case study of a Canadian first nations community. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 4(3), 302–330. doi:10.1080/19420676.2013.820779

- Drayton, W. (2002). The citizen sector: Becoming as entrepreneurial and competitive as business. California Management Review, 44(3), 120–132. doi:10.2307/41166136

- Driver, M. (2012). An interview with Michael Porter: Social entrepreneurship and the transformation of capitalism. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 11(3), 421–431. doi:10.5465/amle.2011.0002a

- Duarte Alonso, A., Kok, S., & O’Brien, S. (2019). ‘Profit is not a dirty word’: Social entrepreneurship and community development. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1–23. doi:10.1080/19420676.2019.1579753

- Easter, S., & Conway Dato-On, M. (2015). Bridging ties across contexts to scale social value: The case of a Vietnamese social enterprise. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 6(3), 320–351. doi:10.1080/19420676.2015.1049284

- El Ebrashi, R. (2013). Social entrepreneurship theory and sustainable social impact. Social Responsibility Journal, 9(2), 188–209. doi:10.1108/SRJ-07-2011-0013

- Emerson, J., & Twersky, F. (1996, September). New social entrepreneurs: The success, challenge and lessons of non-profit enterprise creation. San Francisco: The Roberts Foundation, Homeless Economic Development Fund.

- European Commission. (2011). Social protection and social inclusion in Armenia: Executive summary of the country report. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=6881&langId=en

- European External Action Service. (2019). Armenia development strategy for 2014-2025. Retrieved from https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/armenia_development_strategy_for_2014-2025.pdf

- Ferreira, J. (2002, June 16–19). Corporate entrepreneurship: A strategic and structural perspective. International Council for Small Business, 47th World Conference. San Juan, Puerto Rico.

- Fici, A. (2016). Recognition and legal forms of social enterprise in Europe: A critical analysis from a comparative law perspective. European Business Law Review, 27(5), 639–667.

- Florin, J., & Schmidt, E. (2011). Creating shared value in the hybrid venture arena: A business model innovation perspective. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 2(2), 165–197. doi:10.1080/19420676.2011.614631

- Forouharfar, A. (2018). Social entrepreneurship strategies by the Middle Eastern governments: A review. In N. Faghih & M. Zali (Eds.), Entrepreneurship ecosystem in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) (pp. 189–264). Cham: Springer.

- Forouharfar, A., Rowshan, S. A., & Salarzehi, H. (2018). An epistemological critique of social entrepreneurship definitions. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 8(1), 1–40. doi:10.1186/s40497-018-0098-2

- Franz, H. W., Hochgerner, J., & Howaldt, J. (Eds.). (2012). Challenge social innovation: Potentials for business, social entrepreneurship, welfare and civil society. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Galera, G., & Borzaga, C. (2009). Social enterprise: An international overview of its conceptual evolution and legal implementation. Social Enterprise Journal, 5(3), 210–228. doi:10.1108/17508610911004313

- Gandhi, T., & Raina, R. (2018). Social entrepreneurship: The need, relevance, facets and constraints. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 8(1), 9. doi:10.1186/s40497-018-0094-6

- Geobey, S., Westley, F. R., & Weber, O. (2012). Enabling social innovation through developmental social finance. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 3(2), 151–165. doi:10.1080/19420676.2012.726006

- Gilson, L. L., & Goldberg, C. B. (2015). Editors’ comment: So, what is a conceptual paper? Group and Organization Management, 40(2), 127–130. doi:10.1177/1059601115576425

- Goldsmith, S. (2010). The power of social innovation: How civic entrepreneurs ignite community networks for good. New York: Wiley.

- González, M. F., Husted, B. W., & Aigner, D. J. (2017). Opportunity discovery and creation in social entrepreneurship: An exploratory study in Mexico. Journal of Business Research, 81, 212–220. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.10.032

- Gras, D., & Lumpkin, G. T. (2012). Strategic foci in social and commercial entrepreneurship: A comparative analysis. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 3(1), 6–23. doi:10.1080/19420676.2012.660888

- Greblikaite, J., Sroka, W., & Grants, J. (2015). Development of social entrepreneurship in European Union: Policy and situation of Lithuania and Poland. Transformations in Business and Economics, 14(2), 376–396.

- Grieco, C. (2015). Assessing social impact of social enterprises. Springer Briefs in Business. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-15314-8_2

- Guclu, A., Dees, J. G., & Anderson, B. B. (2002). The process of social entrepreneurship: Creating opportunities worthy of serious pursuit. Center for the Advancement of Social Entrepreneurship, 1, 1–15.

- Haigh, N., & Hoffman, A. (2012). Hybrid organizations: The next chapter of sustainable business. Organizational Dynamics, 41, 126–134. doi:10.1016/j.orgdyn.2012.01.006

- Hand, M. (2016,, May 24). The research gap in social entrepreneurship. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Retrieved from https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_research_gap_in_social_entrepreneurship

- Hervieux, C., Gedajlovic, E., & Turcotte, M. F. B. (2010). The legitimization of social entrepreneurship. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 4(1), 37–67. doi:10.1108/17506201011029500

- Hibbert, S. A., Hogg, G., & Quinn, T. (2002). Consumer response to social entrepreneurship: The case of the big issue in Scotland. International Journal of Non-profit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 7(3), 288–301. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1479-103X

- Hill, T. L., Kothari, T. H., & Shea, M. (2010). Patterns of meaning in the social entrepreneurship literature: A research platform. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 5–31. doi:10.1080/19420670903442079

- HM Government. (2018). Civil society strategy: Building a future that works for everyone, cabinet office. Retrieved from London.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/732765/Civil_Society_Strategy_-_building_a_future_that_works_for_everyone.pdf

- Hoffman, A. J., Badiane, K. K., & Haigh, N. (2010). Hybrid organizations as agents of positive social change: Bridging the for‐profit and non-profit divide, Ross School of Business. Working Paper. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=1675069

- Huda, M., Qodriah, S. L., Rismayadi, B., Hananto, A., Kardiyati, E. N., Ruskam, A., & Nasir, B. M. (2019). Towards cooperative with competitive alliance: Insights into performance value in social entrepreneurship. In Creating business value and competitive advantage with social entrepreneurship (pp. 294–317). IGI Global.

- Idris, A., & Hijrah Hati, R. (2013). Social entrepreneurship in Indonesia: Lessons from the past. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 4(3), 277–301. doi:10.1080/19420676.2013.820778

- International Labour Office. (2011). Manual on the measurement of volunteer work. Geneva.

- Ireland, R. D., Covin, J. G., & Kuratko, D. F. (2009). Conceptualizing corporate entrepreneurship strategy. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(1), 19–46. doi:10.1111/etap.2009.33.issue-1

- Jiao, H. (2011). A conceptual model for social entrepreneurship directed toward social impact on society. Social Enterprise Journal, 7(2), 130–149. doi:10.1108/17508611111156600

- Kelley, T. (2009). Law and choice of entity on the social enterprise frontier. Tulane Law Review, 84, 2.

- Kerlin, J. A. (2006). Social enterprise in the United States and Europe: Understanding and learning from the differences. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 17(3), 247–263. doi:10.1007/s11266-006-9016-2

- Kerlin, J. A. (2010). A comparative analysis of the global emergence of social enterprise. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 21(2), 162–179. doi:10.1007/s11266-010-9126-8

- Kistruck, G. M., & Beamish, P. W. (2010). The interplay of form, structure, and embeddedness in social intrapreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(4), 735–761. doi:10.1111/etap.2010.34.issue-4

- Korosec, R. L., & Berman, E. M. (2006). Municipal support for social entrepreneurship. Public Administration Review, 66(3), 448–462. doi:10.1111/puar.2006.66.issue-3

- Kuratko, D. F., & Audretsch, D. B. (2017). Strategic entrepreneurship: Exploring different perspectives of an emerging concept. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(1), 1–17. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00278.x

- Kuratko, D. F., & Hodgetts, R. M. (1995). Entrepreneurship: A contemporary approach (3rd ed.). Orlando: Dryden Press.

- Langevang, T., & Namatovu, R. (2019). Social bricolage in the aftermath of war. In Entrepreneurship & regional development (pp. 1–21).

- Lasprogata, G. A., & Cotton, M. N. (2003). Contemplating enterprise: The business and legal challenges of social entrepreneurship. American Business Law Journal, 41(1), 67. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1714.2003.tb00002.x

- Lehner, O. M., & Kansikas, J. (2013). Pre-paradigmatic status of social entrepreneurship research: A systematic literature review. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 4(2), 198–219. doi:10.1080/19420676.2013.777360

- Liger, Q., Stefan, M., & Britton, J. (2016). Social Economy. European Parliament, Directorate general for internal policies, Policy Department A: Economic and scientific policy. Retrieved from http://www.europarl.europa.eu/studies

- Lisetchi, M., & Brancu, L. (2014). The entrepreneurship concept as a subject of social innovation. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 124, 87–92. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.02.463

- London, T., & Hart, S. L. (2011). Next generation business strategies for the base of the pyramid: New approaches for building mutual value. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education.

- Longman Advanced American Dictionary. (2007). Replication, p. 1341.

- Lough, B. J., & McBride, A. M. (2013). The influence of solution-focused reflection on international social entrepreneurship identification. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 4(2), 220–236. doi:10.1080/19420676.2013.777361

- Luke, B., Kearins, K., & Verreynne, M. L. (2011). Developing a conceptual framework of strategic entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research, 17(3), 314–337. doi:10.1108/13552551111130736

- Maclean, M., Harvey, C., & Gordon, J. (2013). Social innovation, social entrepreneurship and the practice of contemporary entrepreneurial philanthropy. International Small Business Journal, 31(7), 747–763. doi:10.1177/0266242612443376

- Mair, J., & Marti, I. (2006). Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. Journal of World Business, 41(1), 36–44. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2005.09.002

- Manton, S. (2005). Integrated intellectual asset management. Gower Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-566-08721-9.

- Marshall, R. S. (2011). Conceptualizing the international for-profit social entrepreneur. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(2), 183–198. doi:10.1007/s10551-010-0545-7

- Mas-Machuca, M., Ballesteros-Sola, M., & Guerrero, A. (2017). Unveiling the mission statements in social enterprises: A comparative content analysis of US- vs. Spanish-based organizations. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 8(2), 186–200. doi:10.1080/19420676.2017.1371629

- Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary. (2002). 10th ed. USA: Springfield, Massachusetts.

- Millar, R., Hall, K., & Miller, R. (2013). A story of strategic change: Becoming a social enterprise in English health and social care. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 4(1), 4–22. doi:10.1080/19420676.2012.694371

- Ministry of Justice. (2019). Retrieved fromhttp://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/law/detail/?id=24&vm=04&re=01

- Montgomery, A. W., Dacin, P. A., & Dacin, M. T. (2012). Collective social entrepreneurship: Collaboratively shaping social good. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(3), 375–388. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1501-5

- Moore, M. L., Westley, F. R., & Brodhead, T. (2012). Social finance intermediaries and social innovation. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 3(2), 184–205. doi:10.1080/19420676.2012.726020

- Mort, G., Weerawardena, J., & Carnegie, K. (2002). Social entrepreneurship: Towards conceptualization. International Journal of Non-profit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 8(1), 76–88. doi:10.1002/nvsm.202

- Mulgan, G. (2006). The process of social innovation. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization, 1(2), 145–162. doi:10.1162/itgg.2006.1.2.145

- Munoz, J. M. (2010). International social entrepreneurship: Pathways to personal and corporate impact. Business Expert Press.

- Newbert, S. L., & Hill, R. P. (2014). Setting the stage for paradigm development: A ‘small-tent’ approach to social entrepreneurship. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 5(3), 243–269. doi:10.1080/19420676.2014.889738

- Nicholls, A., & Cho, A. (2006). Social entrepreneurship: The structuration of a field. In A. Nicholls (Ed.), Social entrepreneurship: New models of sustainable social change (pp. 99–118). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nicholls, A. (Ed.). (2008). Social entrepreneurship: New models of sustainable social change. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nicholls, A. (2009). ‘We do good things, don’t we?’: ‘Blended value accounting’ in social entrepreneurship. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 34(6–7), 755–769. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2009.04.008

- Nicholls, A., & Murdock, A. (Eds.). (2011). Social innovation: Blurring boundaries to reconfigure markets. Springer.

- Nicholls, A., & Murdock, A. (2012). The nature of social innovation. In Social innovation (pp. 1–30). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ormiston, J., Charlton, K., Donald, M. S., & Seymour, R. G. (2015). Overcoming the challenges of impact investing: Insights from leading investors. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 6(3), 352–378. doi:10.1080/19420676.2015.1049285

- Ormiston, J., & Seymour, R. (2011). Understanding value creation in social entrepreneurship: The importance of aligning mission, strategy and impact measurement. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 2(2), 125–150. doi:10.1080/19420676.2011.606331

- Peredo, A. M., & McLean, M. (2006). Social entrepreneurship: A critical review of the concept. Journal of World Business, 41(1), 56–65. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2005.10.007

- Perrini, F., Vurro, C., & Costanzo, L. A. (2010). A process-based view of social entrepreneurship: From opportunity identification to scaling-up social change in the case of San Patrignano. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 22(6), 515–534. doi:10.1080/08985626.2010.488402

- Phillips, W., Lee, H., Ghobadian, A., O’Regan, N., & James, P. (2015). Social innovation and social entrepreneurship: A systematic review. Group and Organization Management, 40(3), 428–461. doi:10.1177/1059601114560063

- Picot, S. (2012). Jugend in der Zivilgesellschaft – Freiwilliges Engagement Jugendlicher im Wandel [Young people in civil society – Voluntary engagement in the process of change]. Gütersloh: Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung.

- Prabhu, G. N. (1999). Social entrepreneurship leadership. Career Development International, 4(3), 140–145. doi:10.1108/13620439910262796

- Public Assistance System. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/topics/social_welfare/dl/outline_of_the_public_assistance_system_20101004.pdf

- Rawhouser, H., Cummings, M., & Newbert, S. L. (2019). Social impact measurement: Current approaches and future directions for social entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(1), 82–115. doi:10.1177/1042258717727718

- Robinson, J. A., Joshi, A. M., Vickerie-Dearman, L., & Inouye, T. (2019). Urban innovation: At the nexus of urban policy and entrepreneurship. In Handbook of inclusive innovation: The role of organizations, markets and communities in social innovation (pp. 129–144). Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Ronsandic, A., & Smal, V. (2018). Social economy in Eastern neighborhood and in the Western Balkans: Country report – Ukraine. Directorate-General for Neighborhood and Enlargement Negotiations (DG NEAR), Contract N°2017/386778, Funded by the EU.

- Rowshan, A., & Forouharfar, A. (2014). Customized social entrepreneurship theory and customized social entrepreneurship strategy as a theory conceptualization and practice towards sustainable development in Iran. Asian Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities, 4(8), 367–385.

- Rwigema, H., & Venter, R. (2004). Advanced entrepreneurship. Cape Town: Oxford University Press.

- Saebi, T., Foss, N. J., & Linder, S. (2019). Social entrepreneurship research: Past achievements and future promises. Journal of Management, 45(1), 70–95. doi:10.1177/0149206318793196

- Sarasvathy, S. D., & Wicks, A. C. (2003). Value creation through entrepreneurship: Reconciling the two meanings of the good life. Under Revision by Academy of Management Review.

- Scheuerle, T., Schües, R., & Richter, S. (2013). Mapping social entrepreneurship in Germany: A quantitative analysis. Centre for Social Investment, University of Heidelberg.

- Scillitoe, J. L., Poonamallee, L., & Joy, S. (2018). Balancing market versus social strategic orientations in socio-tech ventures as part of the technology innovation adoption process–examples from the global healthcare sector. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 9(3), 257–287. doi:10.1080/19420676.2018.1498378

- Seelos, C., Mair, J., Battilana, J., & Tina Dacin, M. (2011). The embeddedness of social entrepreneurship: Understanding variation across local communities. In Communities and organizations (pp. 333–363). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Sekliuckiene, J., & Kisielius, E. (2015). Development of social entrepreneurship initiatives: A theoretical framework. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 213, 1015–1019. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.519

- Shockley, G. E., & Frank, P. M. (2011). The functions of government in social entrepreneurship: Theory and preliminary evidence. Regional Science Policy and Practice, 3(3), 181–198. doi:10.1111/j.1757-7802.2011.01036.x

- Smith, B., Meyskens, M., & Wilson, F. (2014). Should we stay or should we go? ‘Organizational’ relational identity and identification in social venture strategic alliances. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 5(3), 295–317. doi:10.1080/19420676.2014.927389

- Smith, B. R., & Stevens, C. E. (2010). Different types of social entrepreneurship: The role of geography and embeddedness on the measurement and scaling of social value. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 22(6), 575–598. doi:10.1080/08985626.2010.488405

- Snaith, I. (2007). Recent reforms to corporate legal structures for social enterprise in the UK: Opportunity or confusion? Social Enterprise Journal, 3(1), 20–30. doi:10.1108/17508610780000719

- Srivetbodee, S., Igel, B., & Kraisornsuthasinee, S. (2017). Creating social value through social enterprise marketing: Case studies from Thailand’s food-focused social entrepreneurs. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 8(2), 201–224. doi:10.1080/19420676.2017.1371630

- Stryjan, Y. (2006). The practice of social entrepreneurship: Notes toward a resource perspective. In C. Steyaert & D. Hjorth (Eds.), Entrepreneurship as social change: A third movements in entrepreneurship book (pp. 35–55). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Tapsell, P., & Woods, C. (2008). A spiral of innovation framework for social entrepreneurship: Social innovation at the generational divide in an indigenous context. Emergence: Complexity and Organization, 10(3), 25.

- Tapsell, P., & Woods, C. (2010). Social entrepreneurship and innovation: Self-organization in an indigenous context. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 22(6), 535–556. doi:10.1080/08985626.2010.488403

- Thake, S., & Zadek, S. (1997). Practical people, noble causes: How to support community-based social entrepreneurs. London: New Economics Foundation.

- Thompson, J., Alvy, G., & Lees, A. (2000). Social entrepreneurship–A new look at the people and the potential. Management Decision, 38(5), 328–338. doi:10.1108/00251740010340517

- Timmons, J. A., & Spinelli, S. (2003). New venture creation: Entrepreneurship for the 21st century. Boston: McGraw- Hill.

- Townsend, D. M., & Hart, T. A. (2008). Perceived institutional ambiguity and the choice of organizational form in social entrepreneurial ventures. Baylor University. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=1313848

- Tracey, P., & Jarvis, O. (2007). Toward a theory of social venture franchising. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(5), 667–685. doi:10.1111/etap.2007.31.issue-5

- UNICEF. (2017). Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/about/annualreport/files/Algeria_2017_COAR.pdf

- United Nations Statistics Division. (2003). Handbook of non-profit institutions in the system of national accounts. Statistical Papers, series F n°91.

- United Nations. (2019). World Economic Situation and Prospects 2019. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/WESP2019_BOOK-web.pdf

- van der Have, R. P., & Rubalcaba, L. (2016). Social innovation research: An emerging area of innovation studies? Research Policy, 45(9), 1923–1935. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2016.06.010

- Volkmann, C. K., Goia, S. I., & Hadad, S. (2018). Social entrepreneurship across the European Union: An introduction. In Doing business in Europe (pp. 213–234). Cham: Springer.

- Volkmann, C. K., Tokarski, K. O., & Ernst, K. (2012). Background, characteristics and context of social entrepreneurship. In Social entrepreneurship and social business. Germany: Springer, Gabler. doi:10.1007/978-3-8349-7093-0

- Waddock, S., & Post, J. E. (1991). Social entrepreneurs and catalytic change. Public Administration Review, 51(5), 393–401. doi:10.2307/976408

- Wang, C. L., & Altinay, L. (2012). Social embeddedness, entrepreneurial orientation and firm growth in ethnic minority small businesses in the UK. International Small Business Journal, 30(1), 3–23. doi:10.1177/0266242610366060

- Weerawardena, J., & Mort, G. S. (2006). Investigating social entrepreneurship: A multidimensional model. Journal of World Business, 41(1), 21–35. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2005.09.001

- Weisbrod, B. A. (1977). The voluntary nonprofit sector. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

- Westley, F., & Antadze, N. (2010). Making a difference: Strategies for scaling social innovation for greater impact. Innovation Journal, 15(2).

- Whetten, D. (1989). What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 490–495. doi:10.5465/amr.1989.4308371

- Wiley, K. K., & Berry, F. S. (2015). Teaching social entrepreneurship in public affairs programs: A review of social entrepreneurship courses in the top 30 US public administration and affairs programs. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 21(3), 381–400. doi:10.1080/15236803.2015.12002205

- Wilson, J. (2000). Volunteering. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 215–240. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.215

- Wilterdink, N., & Form, W. (2018). Social structure. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/social-structure

- Yang, Y. K., & Wu, S. L. (2015). An exploratory study to understand the internationalization strategies of social enterprises. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 6(1), 31–41. doi:10.1080/19420676.2014.954255

- Young, D. R., & Grinsfelder, M. C. (2011). Social entrepreneurship and the financing of third sector organizations. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 17(4), 543–567. doi:10.1080/15236803.2011.12001661

- Zahra, S. A., Newey, L. R., & Li, Y. (2014). On the frontiers: The implications of social entrepreneurship for international entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(1), 137–158. doi:10.1111/etap.12061

- Zahra, S. A., Rawhouser, H. N., Bhawe, N., Neubaum, D. O., & Hayton, J. C. (2008). Globalization of social entrepreneurship opportunities. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 2(2), 117–131. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1932-443X

- Zald, M. (2000). Ideologically structured action: An enlarged agenda for social movement research. Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 5(1), 1–16.

- Zald, M., & Davis, G. (2005). Social change, social theory, and the convergence of movements and organizations. In G. Davis, D. McAdam, W. Scott, & M. Zald (Eds.), Social movements and organization theory (pp. 335–350). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zander, I., & Zander, U. (2005). The inside track: On the important (but neglected) role of customers in the resource‐based view of strategy and firm growth. Journal of Management Studies, 42(8), 1519–1548. doi:10.1111/joms.2005.42.issue-8

- Zhao, M., & Han, J. (2019). Tensions and risks of social enterprises’ scaling strategies: The case of microfinance institutions in China. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1–21. doi:10.1080/19420676.2019.1604404

- Zietlow, J. T. (2002). Releasing a new wave of social entrepreneurship. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 13(1), 85–90. doi:10.1002/nml.v13:1

- Żur, A. (2015). Social problems as sources of opportunity: Antecedents of social entrepreneurship opportunities. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 3(4), 73–87. doi:10.15678/EBER.2015.030405