Abstract

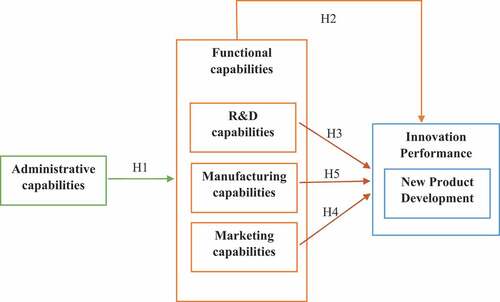

This paper analyzes the organizational capabilities associated with new product development of SMEs in manufacturing companies with indicators such as administrative capabilities, functional capabilities (R&D, manufacturing, and marketing), and innovative performance (new product development) in Malaysia. This study develops an extended structural model linking administrative and functional capabilities to new product development. To empirically analyze these relationships, the researchers used a questionnaire-based survey to collect data from the managers of small manufacturing firms operating in Malaysia. A total of 159 usable questionnaires were received via an online survey of SME managers in Malaysia. The questionnaire was subjected to a PLS structural equation modeling analysis to establish quantitative relationships among constructs. This empirical study confirmed four out of the five hypotheses as statistically significant. SMEs will sustain their competitive advantage by integrating and effectively utilizing their capabilities in administration, manufacturing, and marketing resources. The positive but insignificant effect of the relationship between R&D and new product development can be attributed to the small sample size in this study. However, functional capabilities through the combined mean values of R&D, manufacturing, and marketing capabilities positively and significantly affect SMEs’ new product development. The research framework offers a practical guide for SMEs to sustain their competitive advantage by integrating and effectively utilizing their administration, manufacturing, and marketing resource capabilities.

1. Introduction

As local and global competition intensifies, particularly with COVID-19, the markets are becoming complex and uncertain (Wang, Hong, Li et al., Citation2020). Marketing innovations and organizational capabilities have been extensively argued to help firms survive potential risks during the economic crisis (OECD, Citation2017). “To be innovative is the best way to compete, penetrate a new market, and expand the market share.” This statement sparks the importance of innovation as an unavoidable option for companies. Moreover, innovation has become the main engine and driver of economic growth (EPU, Citation2010; Rosenberg, Citation2004; Torun & Cicekci, Citation2007), which makes building innovative capabilities more important for developing countries that aim to become developed a developed country (Torun & Cicekci, Citation2007). In this regard, new product development (NPD is one of the main components of innovation performance through which the reflection of innovation appears on the market and at economic levels. This fact has promoted the interest of academics who have tried to determine the factors that help companies develop innovations to achieve and secure a competitive advantage in the marketplace (Martinez-Costa & Martnez-Lorente, Citation2008). Certainly, even the most stable environments will ultimately change (Spanos, Citation2012), and this fact further justifies the necessity of innovation for organizations. Therefore, it becomes an imperative goal and option for the companies to adopt or initiate innovation activities continually over time to maintain and improve the competitive position they target or have achieved.

Looking at the Malaysian context, NPD is considered one of the targets to enhance the economy of the country, where the abilities of Malaysian manufacturing companies to develop new successful products will determine the international market share of Malaysian products. However, the Malaysia Science and Technology Information Center's (MASTIC (Citation2003) report shows the slow movement of innovation performance. Despite the efforts that have been paid, the global innovation index report for the five past years 2014 until 2018 demonstrates the range of innovation performance of Malaysian companies varies between 32 and 37. The report is still motivating to continue to level up the innovation performance of Malaysian companies (MASTIC, Citation2003; MOSTI, Citation2017). In the latest survey by the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation (MOSTI) (2018), 499 manufacturing companies participated, and it was reported that 150 manufacturing companies introduced new products. Interestingly, the survey further classified the novelty of the product innovation, and accordingly, it was reported that 25.5% of the participating manufacturing companies introduced new products to the world, while only 40.4% introduced new products to the Malaysian market, and around 37.1% introduced a new product to the firm. Importantly, the profile of the companies that participated in this survey reports that 35.3% of the manufacturing companies were small companies, while 37.5% were medium-sized, followed by 27.3% of big manufacturing companies. This fact could justify the low percentage of new products introduced to the world. Therefore, this study attributes the low performance of the participating companies in introducing a new products to the category of the companies, where 72.7% of the companies involved in the survey were classified as SMEs that face some obstacles to reinforcing their innovation performance.

Even though MOSTI made commendable efforts to conduct this survey, it still does not reflect the real situation in Malaysia due to the low percentage of participants from different sectors and the size of companies. However, the survey is still a valuable source for researchers to get an initial perspective on Malaysian manufacturing players. Consequently, it could be concluded that the performance of Malaysian manufacturing companies is below par compared to what is expected. Given the important role of SMEs in the Malaysian economy, this study is targeting this sector of industry (i.e., SME manufacturing companies). Trying to boost and assist SMEs in manufacturing to be innovative is considered an essential way to reinforce the competitiveness of the manufacturing sector and, at the same time, the productivity of the economy as a whole (Spanos, Citation2012).

On the comparison base, big companies are considered in a much better position of having advantages to be innovative. These advantages originate from a wider pool of resources that big companies own, for instance, formal management skills, specialized manpower (i.e., technical skills), R&D infrastructure and expertise, economies of scale and scope of R&D activities, and the ability to get the rewards of innovative output through gaining numerous intellectual property protections (Spanos, Citation2012; Tether, Citation2000). On the way around, SMEs own some advantages that may help them be innovative; for example, SMEs are more flexible in structures and systems applied compared to big companies, less bureaucratic, the process of making a decision is faster, they are closer to their customers, and they can therefore respond more quickly and effectively to market signals (Spanos, Citation2012; Tether, Citation2000; Vossen, Citation1998). However, the obstacles faced by SMEs constrained the SMEs’ abilities to perform creatively. On top of these obstacles are resource constraints that have been considered considerable restrictions that hinder SMEs’ innovation performance (Rosenbusch et al., Citation2010). Lack of resources comes in different forms, such as a lack of time, technology, expertise, and experience. Besides, the high degree of uncertainty that accompanies innovation makes SMEs more susceptible to risks that might endanger the survival of many SMEs (Gulati, Citation2016; Spanos, Citation2012; M.M. Yusr et al., Citation2014). Therefore, studies to figure out the best strategies to push up the innovation performance of SMEs are needed (Yusr et al., Citation2021a). It is a fact that long-term success requires SMEs to emphasize and focus more on innovation (Spanos, Citation2012). However, the failure of many companies to perform creatively raises questions about what lies behind the uneven product innovation performance of SMEs. The assumption introduced by this study to understand the failure and success of SMEs is that the companies’ capacity to innovate will determine their ability to succeed or fail in producing new successful products.

Customers reward more responsible firms that respond to their requirements and preferences, which requires companies to adapt to meet these emergent needs (Buil-Fabregà et al., Citation2017). Due to the lead managers’ need to adjust to the changing environment, they also need to embrace new capabilities (Yusr et al., Citation2021a; Buil-Fabregà et al., Citation2017). Moreover, capabilities are now viewed by a rising number of academics as the core of business strategy, value generation, and competitive advantage during the past 10 years (Protogerou et al., Citation2008). However, the literature now available on capabilities focuses on determining how organizations may acquire certain abilities that give them long-term sustainability and competitive benefits (Buil-Fabregà et al., Citation2017; Corrêa et al., Citation2019; Kamasak et al., Citation2020; Yusr et al., Citation2022). Thus, a group of studies focus on the nature of the capabilities (Easterby-Smith et al., Citation2009; D J. Teece, Citation2010), while others focus on the gains of establishing capabilities (Yusr et al., Citation2022; Zott, Citation2003), and some investigate what steps must be taken to achieve them (Yusr, Salimon et al., Citation2020; Zahra et al., Citation2006; Zollo & Winter, Citation2002). However, current research still makes a lot of ambiguous claims and interpretations that have not been supported by empirical research (Buil-Fabregà et al., Citation2017; Corrêa et al., Citation2019; Kamasak et al., Citation2020; Protogerou et al., Citation2008). Several researchers are still dubious about the significance of sophisticated conceptualizations of capabilities (Zahra et al., Citation2006); moreover, capabilities have been critiqued for being un-operational and tautologically ambiguous (Priem & Butler, Citation2001). Additionally, although organizational performance has been a central concern in the study of capabilities since Teece et al. (Citation1997) published their landmark work, it is still unclear whether and how capabilities affect performance (Ali et al., Citation2020; Pundziene et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, the majority of the literature introduced capabilities from a general perspective as ”dynamic capabilities” (Aas & Breunig, Citation2017; Farzaneh et al., Citation2022). This could be a reason that creates an ambiguous situation related to the way capabilities impact performance. Therefore, this study divides capabilities into two main categories (i.e., administrative and functional capabilities) to provide a better understanding of what types of capabilities the companies need and where to start building them. There is a lack of understanding of how capabilities administrative and functional capabilities relate to driving innovation performance, particularly new product development. Hence, to better understand the crucial link between administrative capabilities and functional capabilities in fostering the development of new products, we construct and experimentally evaluate a framework that includes both in this study.

This study seeks to make several contributions. First, this study contributes to organizations’ capabilities literature by providing more details related to the types of capabilities that are needed within the organization. We believe it will enable the decision makers with the insight into the right direction to allocate time and budget to build their organizations’ capabilities to boost innovation performance. Second, we answer the demand to deepen our comprehension of how capabilities impact the development of new products by clarifying the relationship between functional capabilities and new product development. The majority of research done so far has used capabilities as a bundle variable, ignoring the individual impact of each element on intended outcomes (e.g., Ali et al., Citation2020; Farzaneh et al., Citation2022; Pundziene et al., Citation2021). To address this gap, we consider functional capabilities as comprising three different components: R&D capabilities, manufacturing capabilities, and marketing capabilities, as depicts. Finally, this research reacts to the need to bridge the knowledge gap in the literature by investigating the role of administrative capabilities in predicting functional capabilities. There is a lack of studies that investigate the antecedents of functional capabilities. Administrative capabilities give managers the ability to deal with market changes, which can occasionally be unforeseen (Buil-Fabregà et al., Citation2017); hence, their role in directing all functional capabilities is crucial. However, empirical evidence is needed.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: The coming section will describe the status of innovation in the Malaysian context, followed by a literature review and hypothesis development. Collecting and analyzing data is presented in the methodology section, followed by results, discussion, and conclusion in the last section.

1.1. Malaysia in perspective

Malaysia is among the well-known countries in the world that have successfully transformed from being an agriculture and mining-based economy in the 1970s to a knowledge-based economy in the 2000s and an innovation-led economy from 2011 onwards (10th Malaysia Plan Citation2011–2015, 2010). The attribute that lies behind this remarkable achievement is the successive plans and strategies targeted by the government during consecutive periods of time. The country successfully managed several economic crises and chose suitable mitigation strategies to mitigate the consequences of major crises that attacked the national economy. Looking at the history of the country, in the last five decades, Malaysia has faced four critical economic crises, all of which resulted from external factors (Lee & Chew-Ging, Citation2017). For instance, the 1973 oil crisis, the mid-1980s global economic slowdown, the 1997 Asian financial crisis, and the 2008 global financial crisis (Lee & Chew-Ging, Citation2017) According to World Economic Forum (Citation2019) Malaysia is classified as an upper-middle-income country with an estimated GDP per capita of about US$ 9,813 in 2018. 2019 Since the independence from British colonialism in 1957, the nation has made outstanding progress on the social and economic front to be announced as a developed and high-income economy by 2020. However, due to several challenges globally and internally, this plan seems to be postponed. Boosting economic performance is the main target, before and currently, to build the nation, and at the same time, to mitigate the unfavorable consequences on the society and economy.

Noticeably, Malaysia has paid attention to innovation as a strategic option to grow. Through several plans, Malaysia started to establish the necessary infrastructure to be an innovation-driven economy. Starting with the knowledge-based economy in 1991, the country strengthens all economic sectors with requirements of the knowledge-based economy. Knowledge-based economy has been defined as an economy where knowledge plays the main role in growth, and this concept, further, relies on humans as the driver of creativity, and other emerged technologies under the fourth industrial revolution umbrella as the enabler of a knowledge-based economy. The country goes steps ahead compared to the other countries in the region (Malaysian Master Plan). Innovation-driven economy is the target to achieve the national goals by being a high-income country soon. Arguably, Malaysia is considered as a country that has the necessary infrastructure to drive innovation; however, the performance still needs a lot to do to be at the desired level (GLOBAL INNOVATION INDEX, Citation2018). In Malaysia, the researches on innovation became among the most interesting issues on academic and government levels (Halim & Ahmad, Citation2017). On a government level, many steps have been taken to insure providing the necessary environment to operate innovation options that have been chosen for economic transformation (MOSTI, 2007). For monitoring purposes, several surveys have been conducted to figure out the progress towards an innovation-led economic goal (MOSTI, 2007). The main points of the Malaysia Economic Monitor Growth through innovation towards high-income nation are as follows (Schellekens, Citation2010):

The main driver of productivity and competitiveness is the nation’s capacity to promote innovation;

Transition to high growth pathway and the high-income nation needs suitable environment for productivity, competitiveness, and innovation which can lead to the creation of high value-added activities for the economy; and

The forefront of the innovation-led growth strategy is focused on leading-edge technologies, developing the human capital capabilities to fulfill the requirements of knowledge-intensive and skills-based industries, and encouraging investment towards quality performance that leads to higher value-added activities.

Nevertheless, despite the efforts government put to foster innovation performance of economic sectors, the ranking of the global competitiveness index demonstrates the slight improvement of Malaysia’s position from 25st in the year 2018 to 27th in the year 2019 (World Economic Forum, Citation2019). Moreover, Malaysia comes at 28th in the performance pertaining innovation ecosystem. This report, though it shows slight improvement, the performance is unsatisfactory where it comes below the expectation and shows the need to form and execute suitable strategies to enhance Malaysian economic sector performance (The World Bank, Citation2018). This result indicates, furthermore, the need to conduct more research to look closely at what factors need to be emphasized to boost the innovation performance of Malaysian industrial sectors. In this regard, SMEs are one of the industrial sectors that play a considerable role in the total performance of the Malaysian economy and are urgently needed to reinforce their innovation performance and build their competitive advantage. A report in August 2020 from the Department of Statistics, Malaysia (DOSM) indicated that the overall SMEs’ contribution to the Malaysian economy has increased to 38.9% in 2019 compared to 38.3% in 2018 (Malaysia Ministry of Entrepreneur Development and Cooperatives, Citation2020). The pre-COVID data for this report in 2019 shows that SMEs in Malaysia employed more than 7 million people, thereby contributing 48.4% of the country’s employment rate. However, due to the limited resources and capacity SEMs own, they are vulnerable to facing several kinds of risks that might threaten their survival, and more attention is needed by this economic sector to enhance innovation performance and build a competitive advantage.

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

2.1. Administrative capabilities and functional capabilities of the organization

To enhance the role of the functional capabilities, effective innovation management or administrative capacity is needed. On the one hand, administrative capacity is defined as the capacity for achieving alignment between a company’s capabilities and changing environmental conditions (Kor & Mesko, Citation2012). Adner and Helfat (Citation2003) consider administrative capabilities as abilities that managers use to develop, combine, and restructure organizational resources and competencies. On the other hand, functional capabilities are related to the organization’s function, which is all activities through which the organization moves towards achieving goals. For instance, marketing, manufacturing, warehousing, customer service, R&D, and other functions or sets of activities carried out within a department or firm. Protogerou et al. (Citation2008) describe functional capabilities as purposeful combinations of resources that provide a company with the ability to carry out operational tasks like manufacturing, marketing, sales, and so on.

Buil-Fabregà et al. (Citation2017) demonstrate that administrative capabilities give managers the ability to deal with market changes, which can occasionally be unforeseen. These capabilities also make the managers better at spotting changes rapidly to alter the firm’s functional capabilities. Moreover, it increases the social and environmental engagements of the company, which leads to the development of the organization’s sustainability. Administrative capabilities are the capabilities that include managerial skills such as managerial cognition, managerial human resources, and managerial social resource (Corrêa et al., Citation2019). According to Adner and Helfat (Citation2003), these skills impact, either combined or separately, managers’ operational and strategic decisions related to the other functional capabilities within the organization. Administrative capabilities play a vital role to direct the organization’s functions towards the market needs. Decisions to start penetrating a new market, the time it takes to make the first sale and profitability, divestment, and investment into new manufacturing technologies are all strongly influenced by administrative skills (Corrêa et al., Citation2019; Helfat & Martin, Citation2015). Furthermore, administrative capabilities describe the connection between managerial choices and actions, strategic transformation, and business success in changing environments through several forms, such as allocating budget, restructuring communication systems among the functional department in a way that can enhance the response to the market requirements, type of training needed, technology, and so on.

Several requirements have been determined by Christiansen (Citation2000) to build an innovative company, such as management structure, deployed culture, and top management attitude that can guide functional capabilities to perform creatively. Hence, administrative capabilities represent the ability to accomplish functions, solving the problems that hinder the tasks to achieve the objectives. Initially, it helps to establish a required level of coordination among the functional departments within the company, which is found to be among the requirements that leads to enhancing the performance of the organizational functions. Besides, administrative capabilities play a role in establishing effective communication throughout the organization; therefore, it can help to illustrate how managers in different functions are more connected, which helps to create the ideal conditions for the interchange and combining of resources, and how this positively affects business performance (Corrêa et al., Citation2019; Helfat & Martin, Citation2015). Moreover, Ferreira et al. (Citation2019) and others considered the strength of the relationship among all functions within the company to reflect the low level of conflict among the organization’s divisions, which in turn, indicate the level of alignment that occurs within the firm to improve the performance (Poberschnigg et al., 2020).

The successful complementary relationship between these two categories of capabilities (administrative and functional capabilities) is critical to the extent that failing in achieving harmony in the link between administrative and functional capabilities will result in a lack of coordination. In other words, tightening the functional capabilities with administrative capabilities will direct the efforts of the firm towards the desired and determined destination. Moreover, administrative ability is considered as the infrastructure to synthesize such functional competencies into an integrated structure (Kogut & Zander, Citation1992). Consequently, we summarized the above discussion in the following hypothesis:

H1: Administrative capabilities have a significant effect on the functional capabilities of the organization.

2.2. Functional capabilities and new product development

Determinants of innovation behaviour take place in the literature with the hope to catch and figure out the most influential innovation determinants (Souitaris, Citation2002). There is a common conclusion among scholars that innovation is subjected to the influence of internal (i.e., organizational) and external (i.e., environmental) factors (Spanos, Citation2012; Yusr, Citation2016a). To determine the conducive environment for innovation performance, several studies have been conducted theoretically and empirically (e.g., Cobbenhagen, Citation2000; Damanpour, Citation1991; Forsman & Rantanen, Citation2011; D J. Teece, Citation2010; Souitaris, Citation2002; Spanos, Citation2012; Sulaiman et al., Citation2017; Wolfe et al., Citation2006; Yusr et al. Citation2017, Citation2022, Citation2012). Between traditional and recent streams of thought, there is a consensus that innovation is an output of several different kinds of processes. The traditional school of management, for instance, states that communication (internally and externally) plus other organizational features (i.e., specialization, functional differentiation, centralization) be determinants of innovation performance (Damanpour, Citation1991; Spanos, Citation2012). More recently, the studies tend to adopt and rely on theories that emerge to explain and explore innovation processes. Among several well-known theories in the literature are absorptive capacity theory, Resource-Based View RBV, and Knowledge-Based View KBV theories. These theories, furthermore, emphasized, without ignoring the traditional determinants of innovation, resources that companies own and the capabilities that have been built within an organization as the antecedents of innovation performance. Resource-based theory and knowledge-based theory classify the resources of organizations into two kinds of resources: hard and soft resources (Grant, Citation1996; guideline-procedures/first_10mp Barney, J, Citation1991). Soft kinds of resources are represented by knowledge the company owns and accesses which includes explicit and tacit kinds of knowledge (Nonaka, Citation1994; i.e., the system of obtaining and generating knowledge and the knowledge in the mind of employees). Based on RBV and KBV theories, the company is a bundle of resources and capabilities that are synthesized together by which the organization performs (Grant, Citation1996; guideline-procedures/first_10mpBarney, J, Citation1991). Therefore, how far the resources are distinguished and heterogeneous, how strong is the competitive advantage of the company. In the same period, Teece et al. (Citation1997) argue that despite the positive role of the resources (i.e., hard and soft capabilities) in building the organisation's competitive advantage, these kinds of competitive advantage are easy to be imitate by competitors in the short run. This argument, further, encourages the authors to emphasize capabilities as another sort of competitive advantage that is embedded within the organization and difficult to imitate at least in the short run. Moreover, innovation in general and new product development, in particular, require unique organizational assets, and capabilities as a foundation to capture the desired benefits (M.M. Yusr et al., Citation2014; Spanos, Citation2012). Capabilities are a bundle of skills that result from repeated activities performed by the organization (Teece et al., Citation1997), it is about what the company does well and what they are likely to do (Teece & Pisano, Citation1994). Therefore, an organization’s functions are places to own and develop inimitable capabilities through which the organization can create a competitive advantage that can be captured through any form of innovation performance. Noticeably, there is an agreement in the economics and management literature on the importance of forming links across functional capabilities such as marketing, R&D, and manufacturing capabilities for successful new product development processes (Teece & Pisano, Citation1994; Yusr, Citation2016a; Yusr et al., Citation2022). Tidd et al. (Citation2005) stress that effectively coordinating and linking all specialist functions is the millstone of successful new product development. Achieving a certain level of interaction and communication throughout the functional areas is critical in enabling product innovation (Pérez-Luño et al., Citation2019). Moreover, responding quickly to market needs on time is essential for new product development processes; in this regard, better coordination among functional capabilities is associated with a more flexible structure that enhances rapid response (Pérez-Luño et al., Citation2019; Tidd et al., Citation2005; Yusr, Mokhtar et al., Citation2020).

Through functional capabilities, the organization will be able to exploit the internal and external competencies to handle the changes in the environment (Teece et al., Citation1997). To do so, establishing an effective communication and coordination system among the involved functions is crucial. Through improving horizontal linkages, better understanding among functional departments will be achieved by including a variety of viewpoints (Spanos, Citation2012; Swink & Song, Citation2007), reducing ambiguity, and anticipating problems before they arise. Achieving that will also help enhance creativity in knowledge creation (Moenaert & Souder, Citation1990).

As capabilities are found to be embedded within organizational functions, for instance, technological, marketing, and manufacturing/operational, the hierarchy of capabilities might go deeply integrated as the functional hierarchy goes which constitutes wide cross-functional capabilities (Grant, Citation1991; Spanos, Citation2012). As new product development is a result of interdisciplinary activities, the contribution of all basic functions of the company is required to successfully develop and commercialize new and/or significantly improved products to the market (Spanos, Citation2012). In the new product domain, David J. Teece (Citation1982) asserts that technological capabilities were determined as the critical constitutive elements that derived from the organization’s R&D activities. Capabilities related to other functions, such as marketing and manufacturing, are classified as complementary competencies (Teece, Citation1982). Based on the discussion above, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H2: functional capabilities have a significant effect on new product development.

2.3. R&D capabilities and new product performance

Logically, the in-house R&D activities establish a decisive antecedent of innovation performance (Spanos, Citation2012) of either radical innovation or, more commonly, incremental innovation that comes in the form of new features in the existing products. Research and development is a component of knowledge-related capabilities, where firms maximize their internal and external knowledge through inter-firm collaborative efforts (Mennenset al., Citation2018). Therefore, companies that invest in enhancing their R&D capabilities will, eventually, generate effective innovation performance (Stock et al., Citation2001). R&D capabilities, in addition, were found to be influential in other dimensions of new product development processes such as time to market, product quality, and, more broadly, innovativeness (i.e., introducing a new product to the market not only new to the company; Spanos, Citation2012). Cohen and Levinthal (Citation1990) emphasize absorptive capacity as the capacity that reflects the organization’s ability to be innovative. Cohen and Levinthal (Citation1990) introduce absorptive capacity theory whereby they argue that absorptive capacity is a capacity represented by several kinds of processes to acquire, disseminate, apply, and commercialize knowledge. This theory, moreover, is being tested and supported by several studies (Griffith et al., Citation2012; Kim, Citation1998; Lane & Koka, Citation2006; M.M. Yusr et al., Citation2014). Other studies conducted by Hung et al. (Citation2010) and Yusr et al. (Citation2017) assert that the ability to use the knowledge and commercialize is the most critical stage by which the innovation performance will be determined. In this context, R&D capacity is one of the organizations’ capabilities to generate related knowledge to develop a new product. This argument is in line with the technology push model whereby the new product is developed and started inside the company when research is being conducted to develop new technology and apply it to the products. Therefore, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H3: R&D capabilities have a significant effect on new product innovation.

2.4. Marketing capabilities and new product performance

The absorptive capacity theory argues that the abilities to commercialize the absorbed knowledge are critical to the success of the new product development. Therefore, as R&D capabilities important to generate the related knowledge for a new or significantly improved product, the capacity to commercialize the new offered product/features is no less important, which reflects the role of marketing capabilities in the success of new product development by identifying and satisfying customers’ needs. Several challenges in the market such as the short life cycle of a product, the revolution of technology in different industries, the role of the retail sector to be as customer agents rather than the company, and so on, raise the importance of marketing capabilities in introducing a new product to the market. Being adopted by the final customer is the main step to succeed in the market. Achieving that is the main concern of marketing activities, whereby all marketing capabilities will be directed to serve this goal. Having a unique capability of marketing research to figure out the gap among customers’ needs helps to improve the output of the screening stage by which the ideas will be filtered and limited to the most relevant and applicable ideas. This stage is critical where the idea might be unique and breakthrough, but, on the laboratory level, not at the market! And this is one of the reasons behind the failure of many newly developed products. As aforementioned, marketing capability is essential to identify and determine the most applicable idea that can fill in the gap in customers’ needs, and yet more important, is to discover the latent need that can give the firm the momentum to capture the first step in the market. The effectiveness of marketing capabilities to boosting the newly developed product on the market, activities such as branding, distribution, pricing, integrated marketing communication, educating customers packaging, advertising, salesmanship, and so on, all play a major role in supporting new product on the market. In addition, the market pull of innovation is a model that emphasizeson market as the starting point through which the new product ideas come to fulfill the needs gap in the market or to offer a solution to some current problems. Therefore, it has been widely emphasized in the literature regarding the role of lead users in new product development processes (Spanos, Citation2012). Accordingly, the following hypothesis is introduced to catch up on the relationship between marketing capabilities and new product development.

H4: marketing capabilities have a significant effect on new product development.

2.5. Manufacturing capabilities and new product performance

Strong capability of manufacturing is another essential requirement of new product development. The ability to produce and transfer the idea and the final prototype of the suggested product is considered among the internal capabilities that give an advantage to the companies that own it. However, the manufacturing capabilities or operation capabilities were discussed inadequately in the literature (Spanos, Citation2012). Several capabilities reflect the organization’s manufacturing capabilities, such as flexibilities, efficiencies, being lean, six sigma, lall of which are types of capabilities that improve manufacturing processes. The synergy among these kinds of capabilities helps to reduce the cost of new product development processes. Therefore, in order to build up manufacturing capabilities, companies need to invest more in so-called manufacturing infrastructure. Elements such as people, management and information system, learning, technology, to mention a few, constitute the necessary infrastructure of an organization’s manufacturing capabilities (Swink & Hegarty, Citation1998). Manufacturing capabilities play a role in achieving product differentiation in the market (Swink & Hegarty, Citation1998; Yusr et al., Citation2018). One of the main challenges facing companies to maintain their manufacturing capabilities up to the bar is the rapid change in the technologies used in the industry. Guan et al. (Citation2006), Yam et al. (Citation2004), Guan and Ma (Citation2003), and others include manufacturing capabilities to be as part of the innovative capabilities of the organization. Referring to absorptive capacity theory to use/apply the knowledge in developing a new product field is translated by the ability to manufacture the product. Hence, the assumption of the role of manufacturing capabilities is supported theoretically by absorptive capacity theory. As a result, the coming hypothesis is introduced:

H5: manufacturing capabilities have a significant effect on new product development.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Data collection

This study is a quantitative approach where a cross-functional survey has been conducted to collect the data. The quantitative approach of this study is compatible with literature that finds it suitable if the goal of the research is to determine the influence relationships among the chosen variables (Creswell, Citation2003; Yusr et al., Citation2017). Hence, the adapted questionnaire from the related literature is used as an instrument to obtain the needed data (Spanos, Citation2012; Yam et al., Citation2004, Citation2011; Yusr, Citation2016b). For this study, an SME is defined as a small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) that employs between 50 and 250 employees (OECD, Citation2017). There are a total of 1300 listed manufacturing companies in the Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers (FMM, Citation2019). Due to the nature of this study, the targeted respondents were the top management of each company as we believe that top management the most appropriate respondents that hold the relevant knowledge to conduct this study (Hung et al., Citation2010; Yusr, Citation2016a; Yusr et al., Citation2017). Simple random sampling is the technique used to form the sample. Data collection processes took place in the period between February and August 2019. A total number of 800 questionnaires were sent to the companies using an online survey. Due to the nature of the population, some efforts were needed to do the appropriate follow up with the company to remind and encourage them to participate in the study. In total, 163 were returned back, and after the processes of screening and cleaning the data, a total number of 159 returned questionnaires were used for final analysis. The response rate of 20% is considered appropriate for such kinds of studies that seek organizational level as a unit of analysis (Cavusgil et al., Citation2003; Gold et al., Citation2001; Hung et al., Citation2010; Yusr, Salimon et al., Citation2020). Besides, Roscoe (Citation1975) suggests a rule of thumb that a sample size which is more than 30 and below 500 is sufficient for most of the research. Looking at Table , almost 44% were CEO, while other percentage goes to different positions among top management like 14% of marketing, 14% of the operation, and 19% of R&D executives. The experience of the respondents was adequate to answer and provide relevant information were 74% of the respondents have experience in the industry ranged between 6 and 15 years. Importantly, 67% of the participating companies were under the category of medium size while 33% were small companies according to Malaysian SMEs Corp.

Table 1. Demographic data

3.2. Measurement and scale

To count the included variables in the model, adopted items from the related literature have been used. All items were counted through a 7-point Likert scale rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). New product development is measured using (Wang & Ahmed, Citation2004). To capture functional capabilities (i.e., marketing, manufacturing, and R&D capabilities), 11 items were adopted from Spanos (Citation2012) and Yam et al. (Citation2011). Finally, to assess administrative capabilities, the study adopted items from Spanos (Citation2012).

An initial pilot study was conducted to check the validity and clarity of the items. For that purpose, the researchers invited three experts, one from the academic field and the other two from the industry. Accordingly, slight modifications were made to items to reflect the environment where the study will be conducted.

4. Data analysis

There are several techniques and statistical approaches that can help to run the obtained data; however, this study applied Partial Least Square-Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Given the advantages of this approach in handling complex models and all related issues that social science usually faces such as non-normal data, the current research tests the proposed hypotheses using SmartPLS 3.0 software. PLS-SEM involves two stages of analysis; starts with a measurement model by which the validity and reliability of the instrument will be tested. This is then followed by a structural model where the proposed hypotheses will be examined.

4.1. Measurement model

In this stage of analysis, the significance of item loadings, validity, and reliability, and and the convergence of the items along with the discriminant validity will be tested. Following the recommendations of Joseph F. Hair et al. (Citation2019), assessment of the reflective measurement model begins with evaluating the loadings of the items. Joseph F. Hair et al. (Citation2019) and Jörg Henseler et al. (Citation2016) suggest that loadings above 0.70 are acceptable and appropriate as this threshold indicates that the construct explains more than 50% of the indicator’s variance that shows a good level of reliability. The next step is to examine the internal consistency reliability. To do so, there are several relevant measures, and among them, the most common measures is composite reliability. It has been reported that the value that is greater than 0.70 and less than 0.95 was found to be satisfactory to good (J. F. Hair et al., Citation2011; Jorg Henseler et al., Citation2009; Joseph F. Hair et al., Citation2019). Moreover, Dijkstra and Henseler (Citation2015) propose Rho_A measure of construct reliability where the minimum accepted value is 0.70 for PLS. The third step of reflecting the measurement model assessment is the convergent validity of each single construct measure (Joseph F. Hair et al., Citation2019). Basically, convergent validity is a measurement that reflects to what extent the construct converges to count the variance of its indicators. Average Variance Extracted (AVE) is the metric used to examine the convergent validity; the acceptable AVE is 0.50 or higher that indicates that the construct is able to count at least 50% of the variance of its items (Joseph F. Hair et al., Citation2019). Table indicates that all values of the mentioned metrics are acceptable and meet all recommended values.

Table 2. The reliability and validity of constructs

The final step to confirm the validity and reliability of the reflective measurement is to test its discriminant validity. Discriminant validity is a metric that displays to what extent the constructs are empirically different from each other constructs in the structural model (Joseph F. Hair et al., Citation2019). In this regard, Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) suggest traditional measures that proposed that the square root value of each construct’s AVE be higher compared to the inter-construct correlation values. However, this metric was found be not suitable all the time and does not help to determine the discriminant validity of the model, particularly when the indicator loadings are differing slightly (Henseler et al., Citation2015). Alternatively, Henseler et al. (Citation2015) suggested the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio of the correlations. HTMT represents “the mean value of indicator correlation across constructs relative to the (geometric) means of the average correlations for the items measuring the same construct” as cited in Joseph F. Hair et al. (Citation2019). According to Henseler et al. (Citation2015), the Liberal HTMT criterion establishes discriminant validity if the value is below 90%, while the strictest standard of HTMT indicates that values must be below 85% to confirm discriminant validity. The obtained result of HTMT of the model under evaluation is displayed in Table . According to the given results, there are no issues related to discriminant validity, and the constructs in the model meet the conservative requirement value that is 0.85 (Henseler et al., Citation2015). Moreover, cross-loading result is shown in Table , indicating that each item has a high load on its respective construct compared to other constructs; this further, leads to conclude confidently that the proposed model meets the discriminant validity criteria.

Table 3. Heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT)

Table 4. Cross loading

NOTE: This are the loading values of each items to the respective construct there are no significance bcoz there are no t_value in the analysis

It is important to indicate that the model includes second-order construct (i.e., functional capabilities); as this study introduced a reflective-reflective model, a repetitive indicator approach is adopted to count the reliability and validity of the second-order conctructs between functional capabilities and the sub-capabilities (i.e., manufacturing, marketing, and RandD capabilities; Becker et al., Citation2012). Tables indicate the loading values and reliability of the higher-order constructs.

4.1.1. Structural measurement

Having satisfactory results of reflective measurement model assessment facilitates the analysis processes to move to the second stage of analysis that is meant to examine the proposed hypotheses. Several criteria need to be met to accomplish this stage (Joseph F. Hair et al., Citation2019), such as coefficient determination (R2), the blindfolding-based cross-validated redundancy measure (Q2), and the statistical significance of path coefficients. As PLS-SEM is a prediction-oriented approach that targets to explain the amount of variance that happens on the endogenous latent variable, the coefficient of determination R2 of a particular endogenous latent variable is considered as the main criteria that help to evaluate the explanatory power of the model (Jörg Henseler et al., Citation2016; Joseph F. Hair et al., Citation2019). The rule of thumb regarding the range of R2 has been determined to be substantial with a value of 0.75, moderate with a value of 0.50, and weak with a value of 0.25 (J. F. Hair et al., Citation2011; Jorg Henseler et al., Citation2009). The proposed model includes two endogenous variables (i.e., functional capabilities and new product development) given that the result by the PLS-SEM algorithm indicates that the R2 value of functional capabilities was 0.282 referring that almost 30% of the variance in functional capabilities was captured by administrative capabilities. In addition, the result indicates that administrative capabilities have a weak impact on functional capabilities. As for new product development, the value of R2 was 0.471 which indicated that 47% of the variance in new product development is counted by functional capabilities. Moreover, the impact of functional capabilities on new product development was classified as moderate.

The study also assesses the cross-validity redundancy Q2 by using blindfolding procedures (Jorg Henseler et al., Citation2009). The value that is greater than zero for a particular endogenous construct indicates the predictive relevance of that exact endogenous construct (Joe F. Hair et al., Citation2014). The attained result from PLS-SEM shows that the Q2 value of functional capabilities was 0.137 while the Q2 of new product development was 0.310. Accordingly, the given output supported the claim that the model established satisfactory predictive relevance.

The final step to examine the structural measurement is testing the proposed hypotheses. To accomplish that, PLS algorithm was run to detect the path coefficient and then bootstrapping was used to identify the significance level of the given coefficients. Two-tailed t-values were used to determine the level of significance of the paths. Out of the four formulated hypotheses, only hypothesis 3 was rejected. Figure and Table present the path coefficient values along with the significance level. Notably, this study primarily measures the relationship between the primary structures, but further analysis is carried out to identify the impact of each capability and which capability has the most influence.

Table 5. Path coefficients

5. Discussion

The goal of this study is to explore the internal requirements that determine the success of new product development among SMEs. For that purpose, a comprehensive review of the related literature has been conducted to figure out the most conducive factors. As a result, two-level of influential factors have been captured to play a role in enhancing the performance of newly developed products (i.e., administrative capabilities and functional capabilities). Basically, administrative capabilities are determined to be the antecedents of functional capabilities that play an essential role in providing and establishing functional capabilities. Functional capabilities, in turn, were counted by three main capabilities represented by marketing, manufacturing, and R&D capabilities to have an influential role in the success of new product development. Managers of SME manufacturing companies in Malaysia were the source of information to evaluate the hypothesized model.

The results indicate that administrative capabilities have a significant effect on functional capabilities (b 0.538, t 10.268) with a positive direction. This result indicates that administrative capabilities are essential to coordinate and lead all functions within the organization to be more innovative, which in turn, leads to establish innovation capabilities. This finding supports what has been reported in past studies (Pérez-Luño et al., Citation2019; Troy et al., Citation2008; Yusr, Salimon et al., Citation2020). Administrative capabilities reflect the organization’s attitude and the system through which the decision is made. Therefore, the more the administrative capabilities are flexible to accommodate the needs to change the better is the environment to build relevant functional capabilities. In this regard, administrative capabilities cover wide aspects of the management within the organization. An organization’s structure and the hierarchy to make decisions are among the prominent factors that stand behind the innovation performance of the companies. Moreover, these factors help to understand the innovation behavior of SMEs and big companies, private and public sectors. While the SMEs have some credit in terms of the flexibility of the organization’s structure and relatively shorter journey to make decisions, big companies have some bureaucracy. However, the bureaucracy of big private companies is comparatively more flexible compared to public companies. Although the role of these factors is to facilitate and pave the way to innovation performance, these factors are not the determinant factors of innovation performance and new product development. It is important to mention that administrative capabilities play a facilitator role that supports all functions within the firm to perform accordingly. The empirical results of this study emphasize the importance of administrative capabilities, and we could describe these capabilities as the joints that help the body to move and accomplish the tasks; the healthier and more flexible they are; the better the performance.

This study, also, revealed that functional capabilities are a significant determinant of new product development (b 0.687, t 14.611). This expected result supports what has been reported in the literature (Souitaris, 2001; Spanos, Citation2012; Yusr, Citation2016a). What an organization performs reflects its capabilities; hence, the level of quality to perform determines many aspects of organizational performance, including new product development performance. To gain deeper insight related to what functions have more impact on new product development, the effect of marketing, manufacturing, and R&D capabilities were tested through three hypotheses. Providing details related to the role of each function’s capabilities will be useful to the decision-maker of the manufacturing companies, more specifically, SMEs to better understand how and what capabilities need to focus to enhance new product development and innovation performance in general. Accordingly, the hypothesis that discusses the effect of R&D on new product development was not supported (b 0.067, t 1.105). This unexpected result indicates that R&D is not a capability that enhances new product development that is in contrast to the past study’s suggestions. The obtained result of the third hypothesis can be logical from the perspective of the targeted sample, i.e., SMEs. The high cost needed to build R&D capabilities is on top of the reasons behind this result where SME manufacturing companies usually do not have the capabilities to conduct and sponsor R&D function. Looking at the Malaysian scenario, this result is, further, supported by the result of the National Survey of Innovation (Citation2018) that is conducted every 5 years by the Malaysian Science and Technology Information Center (MASTIC). National Survey of Innovation (Citation2018) report indicates that only 25.5% of the participating manufacturing companies introduced a new product to the world. According to this report, around 75% of the manufacturing companies introduced products that were either new to the local market or to the company itself. In other words, the majority are still imitating new successful products.

As expected, the result of this study supports hypothesis 4 that introduces the relationship between marketing capabilities and new product development performance (b 0.179, t 2.127). This also is supported by Yam et al. (Citation2011), Spanos (Citation2012), and Yusr (Citation2016a). Marketing capabilities play a determinant role in most cases of successful new product development. New product usually needs specific marketing capabilities that put efforts to educate the customers and alert them with new function and solution offered by the new products. Moreover, a newly developed product needs the support and effort of marketing not only to commercialize it, but rather the involvement of marketing capabilities is important at the beginning of the processes of developing a new product. To enhance the success rates of a new product, the processes need to be guided by the market. Therefore, pre- and post-marketing activities are essential.

Hypothesis five that states the relationship between manufacturing capabilities and new product capabilities was supported by this study (b 0.564, t 7.756). This output is compatible with previous studies such as Swink and Hegarty (Citation1998), Guan et al. (Citation2006), Yam et al. (Citation2011), and Yusr et al. (Citation2018) that consider manufacturing capabilities as an infrastructure for new product development. To bring this idea to come true, companies need to have the capabilities to produce it in an efficient manner. Moreover, flexibilities are among the manufacturing capabilities that enhance the organizations’ abilities to flex with needs in the market. Efficiency is another critical capability of the manufacturing process. It is not a simple task to alter the processes from one production line to another; however, having such ability is important to encourage new product development processes. As it is well known, one of the hindering factors of new product development among SMEs is the risk associated. In this regard, the risk related to the cost involved in introducing a new product is at the top of the list. Therefore, reducing the cost of introducing a new product will eventually reinforce product innovation performance and make it more achievable.

5.1. Theoretical and managerial implications of study

The outputs of this study carried two levels of implications. First, at a theoretical level, this study offers empirical evidence of the significant and positive role of administrative capabilities to provide a conducive atmosphere of functional capabilities. At the same time, functional capabilities were found to be essential to enhance new product development. Second, at a managerial level, the findings of the present study show that new product development is not only happening in the lab or operation department, but it is also rather a result of holistic work and capabilities that involve top, middle, and bottom-line management to support innovation performance in general and developing a new product in specific. Hence, SME companies need to pay an effort to enhance their administrative capabilities as it helps to facilitate the task of all functional capabilities. A level of coordination is needed to support each functional capability. Administrative capabilities are related to the top-management attitude, the relevant policies, culture, communication structure, autonomy, and so on, that all together form it.

Moreover, functional capabilities are equally important to determine the organization’s innovativeness. Therefore, in light of the obtained results, the decision-makers need to understand the relevant functional capabilities that help to boost new product development. Several factors play a role in pointing out the most significant functional capabilities such as the product, the stage of the product in the life cycle, the competitive strategy, and the objectives of the organization. However, the undeniable functional capabilities that were found to influence new product development are marketing, manufacturing, and R&D capabilities. Although the given result of this study did not support the assumption that establishes the relationship between R&D capability and new product development, we still believe and advise SMEs to put effort to build up the R&D capabilities that can help them to gain the advantage of being first in the market.

In addition, this study recommends that government agencies in Malaysia engage the manager of SMEs in several training programs to enhance and build their administrative capabilities through the functional capabilities will be affected positively. This goal can be achieved through collaboration with educational institutions, for instance, universities. The engagement between industry and knowledge-based institutions will increase the possibilities of sharing knowledge in society, and, consequently, reduce the risk that usually surrounds new product development. It also opens the door to expose potential ideas proposed by the society that could be one way to overcome the financial and knowledge obstacles that SMEs are facing.

6. Limitation

Some limitations need to be highlighted to take note of future research endeavors. This study focuses on SME manufacturing companies that have some characteristics and limitations too. Therefore, in order to generalize the output of this study, it is recommended to cover all players in the manufacturing sector. It is also worth exploring the service sector as innovation in this sector is different compared to manufacturing. The model introduced in the study brings administrative capabilities and unidimensional construct; hence, we suggest breaking it down into several related capabilities to figure out the most effective administrative capabilities and bring deeper knowledge in this regard. Considering broadening functional capabilities to cover other functions helps to expand the view of the decision-maker on the needed capabilities to be developed within their companies, especially the related capabilities to fourth industrial revolution, such as blockchain and internet of things. Moreover, several moderating conditions could be determinants of innovation, for instance, firm size, the industrial sector, and the country environment. Though the size of the company was found to affect the level of the company’s capacity, we argue that the experience of the company in the market and certain industries matters a lot to build the SMEs’ capabilities. The longer time the company spends in the market, the more experience and skills it gains. Therefore, we recommend future studies to explore the moderating condition of innovation performance which is the age of the firm. This suggestion is further supported by the nature of capabilities that request time to establish and build it.

7. Conclusion

As extensively argued above, in most of the quantitative research on innovation, measuring the R&D capabilities is an important component of evaluating new product development and innovative performance of SMEs. However, there are very few studies that have empirically validated the combined effects of the dimensions of functional capabilities (R&D, manufacturing & marketing capabilities) on new product development. A major contribution of this empirical research is the proposed interactive model based on administrative capabilities as the independent variable to the dimensions of functional capabilities and new product development as the dependent variable. The originality of the proposed model is explained in the following four points: (1) It empirically validates the impact of administrative capabilities on functional capabilities of SMEs in Malaysia. The effect of administrative capabilities on the combined mean values of R&D, manufacturing and marketing capabilities explains that SMEs in Malaysia have management processes that focus on cross-functional coordination capabilities. (2) The model incorporates a broad dimension of variables that are relevant to functional capabilities that have not been combined and studied in a single empirical model and particularly from a manufacturing-based economy like Malaysia. (3) As a non-linear model, and it allows both researchers and practitioners to observe the individual and joint impacts of the functional capabilities on new product development that have been overlooked in previous linear models. These results have quantitatively established that the capabilities of SMEs in Malaysia to innovate will determine their ability to succeed or fail in new product development.

New product development is one of the determinant indicators of the organizations’ performance. Therefore, it was important to figure out the best practices to achieve it. For that purpose, the proposed model was tested empirically to investigate the effect of relationship among administrative capabilities and functional capabilities on new product development processes. Due to the special condition that SMEs face in terms of lack of experience and capabilities, this study targeted SMEs manufacturing companies operating in Malaysia. The empirical result confirms the validity and reliability of the instrument used to collect the data which equally assert the validity of the model. All relationships that have been introduced are established positively with significant impact by the outcome of this study. However, a surprising result was related to the relationship+-p between R&D and new product development where the obtained result denied the influential role of R&D on new product development. Nevertheless, this result is justified due to the high cost that R&D requests might go beyond SMEs’ capacity to afford. The positive but insignificant effect of the relationship between R&D and new product development can also be due to the small sample size in this study. Statistically, p-values have been theoretically considered to be confounded due to their dependence on sample size. But we still recommend the SMEs put in the effort to involve in R&D activities and start to build a long-run strategy to establish them.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Prince Sultan University for paying the Article Processing Charges (APC) of this publication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- https://www.smecorp.gov.my/images/press-release/2020/PR_3augBI.pdf

- 10th Malaysia Plan 2011-2015. (2010). Economic planning unit. www.epu.gov.my/en/

- Aas, T. H., & Breunig, K. J. (2017). Conceptualizing innovation capabilities: A contingency perspective. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 13(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.7341/20171311

- Adner, R., & Helfat, C. E. (2003). Corporate effects and dynamic managerial capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 24(10), 1011–1025. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.331

- Ali, M. A., Hussin, N., Abed, I. A., Nikkeh, N. S., & Mohammed, M. A. (2020). Dynamic capabilities and innovation performance: systematic literature review. Technology Reports of Kansai University, 62(10), 5989–6000. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344278226

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700

- Becker, J. M., Klein, K., & Wetzels, M. (2012). Hierarchical latent variable models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long Range Planning, 45(5–6), 359–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2012.10.001

- Buil-Fabregà, M., Alonso-Almeida, M. Del, M., & Bagur-Femenías, L. (2017). Individual dynamic managerial capabilitiesInfluence over environmental and social commitment under a gender perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 151, 371–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.03.081

- Cavusgil, S. T., Calantone, R. J., & Zhao, Y. (2003). Tacit knowledge transfer and firm innovation capability. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 18(1), 6–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/08858620310458615

- Christiansen, J. A. (2000). Building the Innovation organization. Management Sytems That Ecnourage Innovation.

- Cobbenhagen, J. (2000). Successful innovation towards a new theory for the management of small and medium-sized enterprises. Edward Elgar.

- Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity : A new perspective on and innovation learning. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128–152. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393553

- Corrêa, R. O., Bueno, E. V., Kato, H. T., & Silva de O, L. M. (2019). Dynamic managerial capabilities: Scale development and validation. Managerial and Decisito the Economics, 40(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.2974

- Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design (I) ed.). Sage Publication.

- Damanpour, F. (1991). Organizational innovation : A meta-analysis of effects of determinants and moderators. Academy of Management Journal, 34(3), 555–590. https://doi.org/10.2307/256406

- Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J. (2015). Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, 39(2), 297–316. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2015/39.2.02

- Easterby-Smith, M., Lyles, M. A., & Peteraf, M. A. (2009). Dynamic capabilities: Current debates and future directions. British Journal of Management, 20(Suppl. 1), S1–S8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2008.00609

- EPU. (2010). Economic Plan Unit. http://www.epu.gov.my/

- Farzaneh, M., Wilden, R., Afshari, L., & Mehralian, G. (2022). Dynamic capabilities and innovation ambidexterity: The roles of intellectual capital and innovation orientation. Journal of Business Research, 148(April), 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.04.030

- Ferreira, A. C., Pimenta, M. L., & Wlazlak, P. (2019). Antecedents of cross-functional integration level and their organizational impact. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 34(8), 1706–1723. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-01-2019-0052

- FMM. (2019). Federation of Malaysian manufacturers (41 st) ed.).

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, XVIII(Feb), 39. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- Forsman, H., & Rantanen, H. (2011). Small manufacturing and service enterprises as innovators: A comparison by size. European Journal of Innovation Management, 14(1), 27–50. https://doi.org/10.1108/14601061111104689

- GLOBAL INNOVATION INDEX. (2018). GLOBAL INNOVATION INDEX 2018: Energizing the world with innovation. Cornell University, INSEAD, and WIPO. https://doi.org/10.1080/10686967.2002.11919042

- Gold, A. H., Malhotra, A., & Segars, A. H. (2001). Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 185–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2001.11045669

- Grant, R. (1991). The Resource-Based Theory of Competitive Advantage: Implications for Strategy Formulation. California Management Review, 33(3), 114–135.

- Grant, R. M. (1996). Prospering as in integration environments : organizational capability as knowledge integration. Organization Science, 7(4), 375–387. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.7.4.375

- Griffith, D. A., Kiessling, T., & Dabic, M. (2012). Aligning Strategic Orientation with Local Market Conditions Management, 29(4), 379–402. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651331211242629

- Guan, J., & Ma, N. (2003). Innovative capability and export performance of Chinese firms. Technovation, 23(9), 737–747. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4972(02)00013-5

- Guan, J. C., Yam, R. C. M., Mok, C. K., & Ma, N. (2006). A study of the relationship between competitiveness and technological innovation capability based on DEA models. European Journal of Operational Research, 170(3), 971–986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2004.07.054

- Gulati, R. (2016). Is slack good or bad for innovation ? Author (s): Nitin Nohria and Ranjay Gulati Source. The Academy of Management Journal, 39(5), 1245–1264. Vol . 39, No . 5 (Oct ., 1996), pp . 12451264 Published by : Academy of Management Stable URL . . Vol . 39, No . 5 (Oct ., 1996), pp . 12451264 Published by : Academy of Management Stable URL . http://www.jstor.org/stable

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. The Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

- Halim, H. A., & Ahmad, N. H. (2017). Transforming Malaysia towards an innovation-led economy by leveraging on innovative human capital. The Winners, 13(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.21512/tw.v13i1.667

- Helfat, C. E., & Martin, J. A. (2015). Dynamic managerial capabilities: review and assessment of managerial impact on strategic change. Journal of Management, 41(5), 1281–1312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314561301

- Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management and Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academic Science, 43, 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Advances in International Marketing, 20, 277–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1474-7979(2009)0000020014

- Hung, R.-Y.-Y., Lien, B. Y.-H., Fang, S.-C., & McLean, G. N. (2010). Knowledge as a facilitator for enhancing innovation performance through total quality management. Total Quality Management, 21(4), 425–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783361003606795

- in the Malaysia economy expanded further in 2019; Retrieved on 9th May, 2021 from

- Kamasak, R., Ozbilgin, M., Kucukaltan, B., & Yavuz, M. (2020). Regendering of dynamic managerial capabilities in the context of binary perspectives on gender diversity. Gender in Management, 35(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-05-2019-0063

- Kim, L. (1998). Crisis construction and organizational learning: capability building in catching-up at Hyundai motor. Organization Science, 9(4), 506–521. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.9.4.506

- Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the firm. Combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Knowledge in Organisations, 3(3), 17–36. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.3.3.383

- Kor, Y. Y., & Mesko, A. (2012). Dynamic managerial capabilities: configuration and orchestration of top executives’ capabilities and the firm’s dominant logic. Strategic Management Journal, 4(June), 2–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj

- Lane, P. J., & Koka, B. R. (2006). The reification of absorptive capacity: A critical review and rejuvenation of the construct. Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 833–863. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20159255

- Lee, C., & Chew-Ging, L. (2017). The evolution of development planning in Malaysia. Journal of Southeast Asian Economies, 34(3), 436–461. https://doi.org/10.1355/ae34-3b

- Malaysia Ministry of Entrepreneur Development and Cooperatives. (2020). Media release share of SMEs. https://www.smecorp.gov.my/

- Martínez-Costa, M., & Martínez-Lorente, A. R. (2008). Does quality management foster or hinder innovation? An empirical study of Spanish companies. Total Quality Management, 19(3), 209–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783360701600639

- MASTIC. (2003). National Survey Of Innovation. Malaysian Science and Technology Information Centre.

- Mennens, K., Van Gils, A., Odekerken-Schröder, G., & Letterie, W. (2018). Exploring antecedents of service innovation performance in manufacturing SMEs. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 36(5), 500–520. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242617749

- Moenaert, R. K., & Souder, W. E. (1990). An information transfer model for integrating marketing and R&D Personnel in new product development projects. The Journal of Product Innovation Management, 7(2), 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/0737-6782(90)90052-G

- MOSTI. (2017). National Survey of innovation (2015) (Issue January). http://www.mosti.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/TechnoFund-Guidelines-2016.pdf

- National Survey of Innovation. (2018). Ministry of science, technology & innovation MOSTI. https://mastic.mosti.gov.my/sti-survey-content-spds/national-survey-innovation-2018

- Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science, 5(1), 14–37. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.5.1.14

- OECD.(2017). Entrepreneurship at Glance 2017. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/entrepreneur_aag-2017-en

- Pérez-Luño, A., Bojica, A. M., & Golapakrishnan, S. (2019). When more is less: The role of cross-functional integration, knowledge complexity and product innovation in firm performance. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 39(1), 94–115. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-04-2017-0251

- Poberschnigg da S, T. F., Pimenta, M. L., & Hilletofth, P. (2020). How can cross-functional integration support the development of resilience capabilities? The case of collaboration in the automotive industry. Supply Chain Management, 25(6), 789–801. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-10-2019-0390

- Priem, R. L., & Butler, J. E. (2001). Is the Resource-Based ”View” a Useful Perspective for Strategic Management Research?. The Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 22–40. https://doi.org/10.2307/259392

- Protogerou, A., Caloghirou, Y., & Lioukas, S. (2008). Dynamic capabilities and their indirect impact on firm performance. Industrial and Corporate Change, 21(3), 615–647. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtr049

- Pundziene, A., Nikou, S., & Bouwman, H. (2021). The nexus between dynamic capabilities and competitive firm performance: The mediating role of open innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 25(6), 152–177. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-09-2020-0356

- Roscoe, J. T. (1975). Fundamental research statistics for the behavioral sciences (2nd) ed.). Hort, Rinehart and Winston.

- Rosenberg, N. (2004). Innovation and Economic Growth. Retrieved from: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/tourism/34267902.pdf

- Rosenbusch, N., Brinckmann, J., & Bausch, A. (2010). Is innovation always beneficial? A meta-analysis of the relationship between innovation and performance in SMEs. Journal of Business Venturing, xxx(xxx, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.12.002

- Schellekens, P. (2010). Malaysia economic monitor: Growth through innovation. In Malaysia economic monitor. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. https://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/671411468050060249/Malaysia-economic-monitor-growth-through-innovation

- Souitaris, V. (2002). Technological trajectories as moderators of firm-level determinants of innovation. Research Policy, 31(6), 877–898. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(01)00154-8

- Spanos, Y. E. (2012). Antecedents of SMEs’ product innovation performance: A configurational perspective. International Journal of Innovation and Regional Development, 4(2), 97. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijird.2012.046577

- Stock, G. N., Greis, N. P., & Fischer, W. A. (2001). Absorptive capacity and new product development. Journal of High Technology Management Research, 12(1), 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1047-8310(00)00040-7

- Sulaiman, Y., Masri, M., Yusr, M. M., Ismail, M. Y. S., Mustafa, S. A., & Salim, N. (2017). The relationship between marketing mix and consumer preference in supplement product usage. International Journal of Economic Research, 14(19). https://serialsjournals.com/index.php?route=product