Abstract

This study aimed to examine the relationships between perceived internal and external salary equity and affective commitment, as well as the moderation effect of gender on these relationships among university academic staff in Egypt. Structural equation modeling was used to test the study hypotheses, based on data obtained through a face-to-face questionnaire survey of 246 academic staff members conveniently-sampled from eight Egyptian universities located in Greater Cairo. The findings of the study disclose: (1) a significant positive relationship between perceived internal salary equity and affective commitment; (2) a significant positive relationship between perceived external salary equity and affective commitment; and (3) that the relationship between perceived internal salary equity and affective commitment is stronger among males. Despite the fact that this study is, methodologically, a replication of other previous studies, it still contributes new insights from Egypt to the predominantly Western and Asian literature on the perceived salary equity-affective commitment link. Additionally, the study examines the neglected moderation effect of gender on this link.

1. Introduction

Affective commitment (AC) –which refers to an employee’s emotional attachment to, identification with, and involvement in the organization (Meyer & Allen, Citation1997)– positively relates with various positive work outcomes such as employee performance (Kim, Citation2014) and employee innovation (Odoardi et al., Citation2019). Thus, organizational success requires the maintenance of high levels of AC. Enhancing AC requires profound acquaintance with its antecedents. One important positive contributor to AC is perceived salary equity (PSE). This is indicated in the findings of many studies (e.g. Buttner & Lowe, Citation2017; ElDin & Abd El Rahman, Citation2013; Khaola and Rambe, Citation2021; Li et al., Citation2018; Roberts et al., Citation1999; Chai et al., Citation2020; Suifan, Citation2019; To & Huang, Citation2022). Building on Adams’s (Citation1963, Citation1965) Equity Theory, PSE can be defined as the extent to which employees perceive that they receive an equitable salary as compared to others working for the same organization (perceived internal salary equity—PISE) and those working for other organizations (perceived external salary equity—PESE).

To the best of the researcher’s knowledge, the vast majority of published studies tackling the PSE-AC link have been conducted in Western and Asian countries, and no research has addressed the link in Egypt. From a cultural relativist perspective, this constitutes a substantial knowledge gap and sheds doubt on the applicability of the findings of previous research in the Egyptian context. This is because cross-cultural dissimilarities lead to differences with regards to preferences of outcomes at the workplace (Hofstede, Citation2001). More pertinent to the present study, cultural factors profoundly impact equity sensitivity levels and the subsequent employees’ attitudes (Chhokar et al., Citation2001; Buzea, Citation2014). For example, Aumer-Ryan et al., (Citation2007) reported that employees in individualistic cultures are far more concerned with equity than are employees in collectivist cultures. Another knowledge gap is that, to the best of the researcher’s knowledge, no research has tackled the moderation effect of employees’ demographic characteristics in the PSE-AC nexus.

In an attempt to fill the first of the two above-discussed knowledge gaps, the present study aimed to examine the relationships between PISE and PESE (as independent constructs) and AC (as a dependent construct) among university academic staff in Egypt. Additionally, to help fill the second knowledge gap, the study also aimed to scrutinize the moderation effect of gender in these relationships.

2. Literature review and study hypotheses

2.1. Distinguishing AC from continuance and normative commitment

Perhaps the most widely used model of organizational commitment in organizational research is Meyer and Allen’s (Citation1991, Citation1997) three-component model. According to this model, organizational commitment is defined as the employee’s psychological state towards his/her organization that has three distinguishable components (a continuance component, a normative component and an affective component). As per Meyer and Allen, continuance commitment refers to commitment caused by the employee’s perceived costs (both economic and social) of losing organizational membership. In this sense, employees remain with the organization because they “need to”. Normative commitment refers to commitment induced by the employee’s moral feelings of obligation to continue employment in the organization (Meyer & Allen). In this sense, employees remain with the organization because they “feel that it is the right thing to do so”. Most pertinent to the present study, the affective component of commitment refers to an employee’s emotional attachment to, identification with, and involvement in the organization (Meyer & Allen). In this sense, employees remain with the organization because they “want to”.

2.2. PISE and PESE

According to Equity Theory (Adams, Citation1963, Citation1965), every employee cognitively processes a perceived ratio of the outcomes that he/she receives from a job to the inputs that he/she brings on the job, and compares this ratio to the ratios of other employees (comparison referents). In such equity assessments, outcomes comprise, but are not limited to: status, recognition, promotion, job security, fringe benefits, and most relevant to the present study, salary. Inputs, on the other hand, typically include: qualifications, skills, experience, job effort, working hours, etc. The comparison referent can be either another employee working for the same organization (in internal equity assessments), or another employee working for another organization (in external equity assessments). In this manner of social comparison, the closer the employee’s own ratio to the referent’s ratio, the greater is perceived equity. Thus, in the context of the present study, PISE is defined as the extent to which the employee perceives that he/she receives an equitable salary as compared to others working for the same organization. Conversely, PESE is defined as the extent to which the employee perceives that he/she receives an equitable salary as compared to others working for other organizations.

Adams (Citation1963, 1967) argues that all employees seek equitable treatment. However, this view has been challenged by other organizational psychologists. For instance, Huseman et al. (Citation1987) proposed an “equity sensitivity construct”, suggesting that individuals vary with regards to their equity preferences. Three different types of people were identified by Huseman et al.: (1) “benevolents” –those who prefer to be relatively undercompensated; (2) “entitleds” –those who prefer to be relatively overcompensated; and (3) “equity-sensitives” –those who prefer to be equitably compensated.

2.3. The relationship between PSE and AC

A positive relationship between perceived equity and AC is highly evident in the literature (e.g. Buttner & Lowe, Citation2017; ElDin & Abd El Rahman, Citation2013; Roberts et al., Citation1999; Li et al., Citation2018; Suifan, Citation2019; Chai et al., Citation2020; Khaola & Rambe, Citation2021; To & Huang, Citation2022). This positive link can be attributed to the intervention of perceived organizational support. Shore and Shore (Citation1995) proposed that repeated instances of fairness decisions concerning resource distribution strongly contribute to perceived organizational support by indicating a concern for employees’ welfare. In line with this notion, a meta-analytic study by Rhoades and Eisenberger (Citation2002) reported a consistent, strong positive effect of procedural justice on perceived organizational support. Based on the norm of reciprocity, perceived organizational support creates a felt obligation to care about the welfare of the organization (Eisenberger et al., Citation2001). Rhoades and Eisenberger suggest that this felt obligation to exchange caring for caring enhances AC to the “personified organization”. Additionally, in line with Rhoades and Eisenberger, perceived organizational support contributes to AC through satisfying employees’ socioemotional needs for affiliation and emotional support. Consistent with this, research has constantly shown that perceived organizational support positively relates with AC (e.g. Rhoades et al., Citation2001; Arasanmi & Krishna, Citation2019; Dasgupta, Citation2016; Rumangkit, Citation2020). Thus, the two following hypotheses were tested:

H1:

There is a significant positive relationship between PISE and AC.

H2:

There is a significant positive relationship between PESE and AC.

2.4. The moderation effect of gender

We propose two rationales for hypothesizing that gender moderates the PSE-AC link. First, there is empirical evidence that men and women exhibit different equity sensitivity levels. According to Kahn et al. (Citation1980), due to different interaction objectives, while females are more concerned about interpersonal success, males tend to be more concerned about competitive success. As per Witt and Nye (Citation1992), this difference leads to females placing more emphasis on equality, and males placing more emphasis on equity. In this context, equality in the workplace refers to distributing resources equally among employees disregarding their individual inputs, while equity signifies the distribution of resources in direct proportion to individual inputs (Brockner & Adsit, Citation1986).

The second rationale for hypothesizing a moderating role of gender in the relationship between PSE and AC is that there has also been empirical evidence that the importance of the job’s financial aspects to the employee varies by gender. Due to psychogender and cultural factors, men and women demonstrate dissimilar work-related interests. For example, Hofstede (Citation2001) proposes that while the primary concerns of men are earnings, promotion, responsibility and autonomy, women on the other hand tend to place more emphasis on issues like social networking, task significance and job security. In line with Hofstede, Vaskova (Citation2006) reported that male employees exhibited more response to “instrumental motivators” that covered basic salary and bonuses, while female employees exhibited more response to “softer issues” such as inter-personal relations and work-family reconciling human resource practices. Additionally, research has been consistently reporting that male employees are more prospective to negotiate for higher salaries (Arnania-Kepuladze, Citation2010; Leibbrandt & List, Citation2014).

Given the above discussion, it can be hypothesized that the relationship between PSE and AC is stronger among male employees. The satisfactoriness of this notion is even higher in a strong male-breadwinner society like Egypt, where men are self-perceived as primary earners of family income, while women are self-perceived as secondary earners and place more emphasis on work-life balance issues (Barrett & McIntosh, 2015). Thus, the two following hypotheses were also tested:

H3:

The relationship between PISE and AC is stronger among males.

H4:

The relationship between PESE and AC is stronger among males.

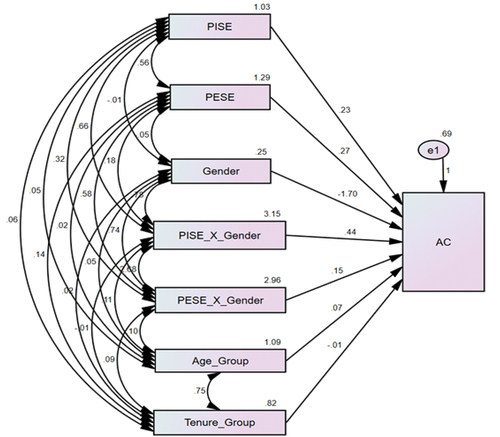

Figure depicts the conceptual framework of the present study, and illustrates the hypothesized relationships among the study constructs.

3. Methods

3.1. Sampling

The sample in the present study comprised 246 academic staff at Egyptian universities. Participants were conveniently drawn from six private universities and two public universities located in Greater Cairo metropolitan area. Respondents’ gender, age group and tenure group data are provided in Table below.

Table 1. Respondents’ gender, age group and tenure group

3.2. Measurement

The data needed for the present study were gathered using a face-to-face, self-report questionnaire survey. The questionnaire started with a guarantee of confidentiality and anonymity to reduce the bias that may result from socially desirable responses. The questionnaire comprised four sections. The first section comprised the demographic items (gender, age and tenure with current employer). The second, third and fourth sections, respectively, involved the items for measuring PISE, PESE and AC. The total number of questionnaires received was 285. This number was reduced to only 246 complete, usable questionnaires. A detailed description of the operationalization of the study constructs is provided below.

Dependent construct (AC): AC was measured using an Arabic version of Meyer et al.’s, (Citation1993) AC scale. The scale consisted of six items, each of which prompted the respondents to rate their agreement with a statement denoting that they are emotionally attached to the organization. An example item is: “I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization”. Responses were obtained using a five-point Likert scale, where 5 = “Strongly Agree”, and 1 = “Strongly Disagree”. Scores for the six items were then averaged to obtain an overall AC score, where a higher score signifies higher AC.

Independent constructs (PISE and PESE): PISE was measured using an Arabic version of Roberts et al.’s, (Citation1999) perception of internal salary equity scale. The scale consisted of three items. Each item asked the respondents to rate their agreement with a statement denoting that they receive a fair salary as compared to co-workers. An example item is: “My salary is fair compared to salaries received by others in this company”. Responses were obtained using a five-point Likert scale, where 5 = “Strongly Agree”, and 1 = “Strongly Disagree”. Scores of the three items were then averaged to calculate an overall PISE score, where a higher score indicates higher PISE. Similarly, PESE was measured using an Arabic version of Roberts et al.’s, (Citation1999) perception of external salary equity scale. The scale consisted of three items, each of which probed the respondents to rate their agreement with a statement denoting that they receive a fair salary as compared to employees working for other organizations. An example item is: “My salary is fair given what employees at other organizations make”. Responses were obtained using a five-point Likert scale, where 5 = “Strongly Agree”, and 1 = “Strongly Disagree”. Scores of the three items were then averaged to calculate an overall PESE score, with a higher score designating higher PESE.

Moderator (gender): Gender was measured using one item prompting the respondents to indicate their gender (male or female). In the analysis, gender was dummy-coded, with 0 assigned for “female”, and 1 assigned for “male”.

Controls (age group and tenure group): The age group of the respondent was determined using one item prompting the respondent to indicate the age group to which he/she belongs. Five age groups were made available to the respondent to choose from: “21–30 years”, “31–40 years”, “41–50 years”, “51–60 years”, and “> 60 years”. Age group was included in the analysis as an ordinal variable, with the mentioned age groups assigned the scores of 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, respectively. Similarly, the tenure group of the respondent was determined using one item prompting the respondent to indicate which group he/she belongs to. Five choices were made available to the respondent: “0–5 years”, “6–10 years”, “11–15 years”, “16–20 years”, and “> 20 years”. Tenure group was included in the analysis as an ordinal variable, with the mentioned groups assigned the scores of 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, respectively.

Ensuring cross-cultural validity of the PISE, PESE and AC scales: To ensure that the Arabic versions of the scales used in the present study are conceptually equivalent to their original English versions, the following procedure recommended by Widenfelt et al. (Citation2005) was employed for each scale. First, the original English version of the scale was translated to Arabic by a professional translator. The resulting Arabic version was then back-translated to English by a second professional translator. This back-translated English version was then compared to the original English version by a third professional translator to scan for any significant discrepancies that might affect linguistic validity of the scale. None of the three translators had any knowledge of the objectives of the present study. For each of the scales used, no significant conceptual differences were found between the original English version and the back-translated English version. Thus the Arabic versions used in the present study were all deemed conceptually-equivalent to the original English versions.

3.3. Statistical methods

We initially calculated the descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, skewness and kurtosis) for PISE, PESE and AC, and the Pearson correlations among them. Afterwards, we assessed the reliabilities of the PISE, PESE and AC scales using Cronbach’s alphas. Next, using AMOS (24.0) software, we: (1) conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess the questionnaire’s discriminant validity; and (2) tested the four study hypotheses through assessing the fit of a structural model. In this structural model, the dependent variable was AC, and the independent variables were: PISE; PESE; gender; PISE*gender (an interaction term); PESE*gender (an interaction term); age group (as a control); and tenure group (as a control).

H1, H2, H3 and H4 were tested based on the signs and statistical significances of the regression weights of PISE, PESE, PISE*gender and PESE*gender, respectively. Since for the variable gender, the response “female” is coded 0, and the response “male” is coded 1, then a statistically significant positive regression weight of any of the interaction terms stated above would indicate that the relationship between PISE or PESE and AC is stronger among males. Further details on how interaction terms are used to test for moderation effects can be found in the work of Frazier et al. (Citation2004).

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive statistics and correlations

Table below reveals the descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations. As shown in Table , none of the skewness or kurtosis statistics is greater than 3.00 in absolute value, indicating that all the variables are normally distributed. Further, PISE and PESE exhibit very low correlation (r = 0.49, P < 0.01), which indicates the absence of a multicollinearity problem.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and correlations

4.2. Reliabilities of the scales

Each of the three scales used in the present study exhibited acceptable reliability, where the Cronbach’s alphas for the AC scale, the PISE scale, and the PESE scale all exceeded 0.70.

4.3. Discriminant validity of the measurement instrument

As aforementioned, we used CFA to assess the discriminant validity of the study questionnaire. The assessment was based on the fit of a model comprising three latent constructs (one for PISE items, one for PESE items, and one for AC items). None of the latent constructs pairs exhibited a standardized covariance of greater than 0.70 in absolute value, signifying good discriminant validity of the measurement instrument. Additionally, each of the PISE items, the PESE items and the AC items loaded well on its corresponding latent construct (where the minimum factor loading was 0.85, and all factor loadings were significant at the P < 0.05 level). Additionally, the overall fit of the model was acceptable; Chi-square = 111.97, P < 0.05; goodness of fit index (GFI) = 0.93; normed fit index (NFI) = 0.97; Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = 0.98; and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.07.

4.4. Hypotheses testing results

Table and Figure show the results of testing the four hypotheses of the study. As revealed in both exhibits, the unstandardized regression weight of PISE is positive and statistically significant (b = 0.23, P < 0.05), indicating support for H1. Further, the unstandardized regression weight of PESE is positive and significant (b = 0.27, P < 0.05), indicating support for H2. Furthermore, the unstandardized regression weight of PISE*gender is positive and statistically significant (b = 0.44, P < 0.05), indicating support for H3. However, the unstandardized regression weight of PESE*gender is positive, but statistically insignificant (b = 0.15, P > 0.05), indicating no support for H4. The overall fit of the model is acceptable; Chi-square = 0.00, df = 0.00, P < 0.05; GFI = 1.00; CFI = 1.00; TLI = 0.98; and RMSEA = 0.51. It should be noted that the high RMSEA value of this model does not constitute an indicator of poor model fit, as the model has zero degrees of freedom. According to Kenny et al. (Citation2015, p. 503), in structural equation modelling (SEM), the RMSEA value should be completely ignored when the model’s degrees of freedom are very few.

Table 3. Results of testing the study hypotheses (SEM)

5. Discussion

The findings of the present study suggest: (1) a significant positive relationship between PISE and AC; (2) a significant positive relationship between PESE and AC; and (3) that the relationship between PISE and AC is stronger among males. The first two findings can be rationalized by the norm of reciprocity. In the context of employment, the employee and the organization enter into a reciprocal relationship in which the employee affectively commits to the organization in exchange for a fair, supportive environment provided by the organization (Moorman et al., Citation1998; Rupp & Cropanzano, Citation2002). Perceptions of fair treatment by the organization (including internal and external salary equity) instill a sense of obligation on the part of employees (Moorman & Byrne, Citation2005). The repayment can then be in the form of positive workplace attitudes, including AC toward the organization (Wayne et al., Citation2002). The third finding can be explained in light of two notions. The first notion is that male employees care for equity more than women do (Witt & Nye, Citation1992). The second notion is that men tend to emphasize pay more than women, who tend to exhibit more concern for “softer” rewards (Arnania-Kepuladze, Citation2010; Hofstede, Citation2001; Vaskova, Citation2006).

With regards to the theoretical contributions made by the present study, the first two findings provide support from Egypt to prior Western and Asian research reporting a positive relationship between PSE and AC (e.g. Buttner & Lowe, Citation2017; ElDin & Abd El Rahman, Citation2013; Li et al., Citation2018; Roberts et al., Citation1999; Suifan, Citation2019; Chai et al., Citation2020; Khaola & Rambe, Citation2021; To & Huang, Citation2022). Further, the third finding provides support to prior research reporting that men care for equity more than women do (e.g. Witt & Nye, Citation1992). Furthermore, the third finding provides support to prior research reporting that men tend to emphasize pay more than women do (e.g. Arnania-Kepuladze, Citation2010; Hofstede, Citation2001; Vaskova, Citation2006).

The findings of the present study have important managerial implications. Since perceptions of internal and external salary equity both positively relate with AC, then managers at Egyptian organizations should ensure that employees will always perceive equity when they compare their salaries to others inside and outside the organization. To achieve this, organizations should adopt equitable financial compensation policies, and openly communicate these policies organization-wide. Further, to avoid ambiguity and incorrect equity assessments, managers should ensure that employees are acquainted of the exact inputs (e.g. job effort, job performance, etc.) contributed by their peers, as well as the salaries those peers receive. This can be achieved through regular, open communication of performance appraisal results.

The present study has a number of limitations. First, a convenient sampling approach was used, and as such, the findings can only be generalized to the population with great caution. Another limitation is that equity sensitivity was not controlled for. Third, all the constructs were measured using the same questionnaire, which could have contributed to common method variance error. According to Podsakoff et al. (Citation2003), measuring predictor and criterion variables in the same measurement context (in terms of time and location in the questionnaire) may produce artifactual covariance that is independent of the content of the constructs. A fourth limitation of the present study is the cross-sectional design it adopted. Particularly in psychological research, it is difficult to determine the temporal order of variables using cross-sectional data, which makes it difficult to establish causal relationships (Cooper & Schindler, Citation1999, p. 166). Given these limitations, it is recommended to conduct a similar longitudinal study using a probability sample, and controlling for equity sensitivity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, M. H. K., upon reasonable request.

References

- Adams, J. S. (1963). Toward an understanding of inequity. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(5), 422–10. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040968

- Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 2, 267–299.

- Arasanmi, C. N., & Krishna, A. (2019). Employer branding: Perceived organisational support and employee retention–the mediating role of organisational commitment. Industrial and Commercial Training, 51(3), 174–183.. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICT-10-2018-0086

- Arnania-Kepuladze, T. (2010). Gender stereotypes and gender feature of job motivation: Differences or similarity? Problems and Perspectives in Management, 8(2), 84–93.

- Aumer-Ryan, K., Hatfield, E. C., & Frey, R. (2007). Examining equity theory across cultures. Interpersona, 1(1), 61–74.. https://doi.org/10.5964/ijpr.v1i1.5

- Brockner, J., & Adsit, L. (1986). The moderating impact of sex on the equity–satisfaction relationship: A field study. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(4), 585–590. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.4.585

- Buttner, E. H., & Lowe, K. B. (2017). The relationship between perceived pay equity, productivity, and organizational commitment for US professionals of color. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 36(1), 73–89.. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-02-2016-0016

- Buzea, C. (2014). Equity theory constructs in a Romanian cultural context. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 25(4), 421–439.. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21184

- Chai, D. S., Jeong, S., & Joo, B. K. (2020). The multi-level effects of developmental opportunities, pay equity, and paternalistic leadership on organizational commitment. European Journal of Training and Development, 44(4/5), 405–424. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-09-2019-0163

- Chhokar, J. S., Zhuplev, A., Fok, L. Y., & Hartman, S. J. (2001). The impact of culture on equity sensitivity perceptions and organizational citizenship behavior: A five-country study. International Journal of Value-Based Management, 14(1), 79–98.. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007865414146

- Cooper, D. R., & Schindler, P. S. (1999). Business research methods (8th edition). McGraw-Hill Irwin.

- Dasgupta, P. (2016). Work engagement of nurses in private hospitals: A study of its antecedents and mediators. Journal of Health Management, 18(4), 555–568. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972063416666160

- Eisenberger, R., Armeli, S., Rexwinkel, B., Lynch, P. D., & Rhoades, L. (2001). Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.42

- ElDin, Y. K. Z., & Abd El Rahman, R. M. (2013). The relationship between nurses’ perceived pay equity and organizational commitment. Life Science Journal, 10(2), 889–896..

- Frazier, P. A., Tix, A. P., & Barron, K. E. (2004). Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51(1), 115–134. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.51.1.115

- Hofstede, G. H. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations (2nd edition). SAGE Publications.

- Huseman, R. C., Hatfield, J. D., & Miles, E. W. (1987). A new perspective on equity theory: The equity sensitivity construct. Academy of Management Review, 12(2), 222–234. https://doi.org/10.2307/258531

- Kahn, A., Krulewitz, J. E., O’Leary, V. E., & Lamm, H. (1980). Equity and equality: Male and female means to a just end. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 1(2), 173–197. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp0102_6

- Kenny, D. A., Kaniskan, B., & McCoach, D. B. (2015). The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociological Methods & Research, 44(3), 486–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124114543236

- Khaola, P., & Rambe, P. (2021). The effects of transformational leadership on organisational citizenship behaviour: The role of organisational justice and affective commitment. Management Research Review, 44(3), 381–398. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-07-2019-0323

- Kim, H. K. (2014). Work-life balance and employees’ performance: The mediating role of affective commitment. Global Business and Management Research: An International Journal, 6(1).

- Leibbrandt, A., & List, J. A. (2014). Do women avoid salary negotiations? Evidence from a large-scale natural field experiment. Management Science, 61(9), 2016–2024.. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.1994

- Li, Y., Castaño, G., & Li, Y. (2018). Perceived supervisor support as a mediator between Chinese university teachers’ organizational justice and affective commitment. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 46(8), 1385–1396. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.6702

- Meyer, J., & Allen, N. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z

- Meyer, J., & Allen, N. (1997). Commitment in the workplace. SAGE Publications.

- Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(4), 538–572. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538

- Moorman, R. H., Blakely, G. L., & Niehoff, B. P. (1998). Does organizational support mediate the relationship between procedural justice and organizational citizenship behavior? A group value model explanation. Academy of Management Journal, 41(3), 351–357. https://doi.org/10.2307/256913

- Moorman, R. H., & Byrne, Z. S. (2005). How does organizational justice affect organizational citizenship behavior? In J. Greenberg & J. Colquitt (Eds.), Handbook of Organizational Justice (pp. 355–380).

- Odoardi, C., Battistelli, A., Montani, F., & Peiró, J. M. (2019). Affective commitment, participative leadership, and employee innovation: A multilevel investigation. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 35(2), 103–113.. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2019a12

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method variance in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698–714. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698

- Rhoades, L., Eisenberger, R., & Armeli, S. (2001). Affective commitment to the organization: The contribution of perceived organizational support. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(5), 825–836. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.825

- Roberts, J. A., Cooper, K., & Lawrence, B. C. (1999). Salesperson perceptions of equity and justice and their impact on organizational commitment and intent to turnover. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 7(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.1999.11501815

- Rumangkit, S. (2020). Mediator analysis of perceived organizational support: Role of spiritual leadership on affective commitment. JDM (Jurnal Dinamika Manajemen), 11(1), 48–55.. https://doi.org/10.15294/jdm.v11i1.21496

- Rupp, D. E., & Cropanzano, R. (2002). The mediating effects of social exchange relationships in predicting workplace outcomes from multi-foci organizational justice. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 89(1), 925–946. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-5978(02)00036-5

- Shore, L. M., & Shore, T. H. (1995). Perceived organizational support and organizational justice. Organizational Politics, Justice, and Support: Managing the Social Climate of the Workplace.

- Suifan, T. S. (2019). The effect of organizational justice on employees’ affective commitment: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Modern Applied Science, 13(2), 42–53. https://doi.org/10.5539/mas.v13n2p42

- To, W. M., & Huang, G. (2022). Effects of equity, perceived organizational support and job satisfaction on organizational commitment in Macao’s gaming industry. Management Decision.

- Vaskova, A. (2006). Administrative behavior: A study of decision-making processes in administrative organization. Free Press.

- Wayne, S. J., Shore, L. M., Bommer, W. H., & Tetrick, L. E. (2002). The role of fair treatment and rewards in perceptions of organizational support and leader-member exchange. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 590–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.590

- Widenfelt, B. M., Treffers, P. D., de Beurs, E., Siebelink, B. M., & Koudijs, E. (2005). Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of assessment instruments used in psychological research with children and families. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 8(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-005-4752-1

- Witt, L. A., & Nye, L. G. (1992). Gender and the relationship between perceived fairness of pay or promotion and job satisfaction. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(6), 910–917. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.77.6.910