Abstract

The current study seeks to examine how mentoring functions foster the well-being of employees working in the Pakistani financial sector. In line with this, the model explores the indirect path of career self-efficacy through which mentoring enhances employee well-being. The mentoring functions (traditional and relational) were explored as predictors of employee well-being and career self-efficacy. Four dimensions of employee well-being were investigated, including purpose in life, job wellness, work-life balance and physical health. Data (N = 384) were collected through a survey-based questionnaire from staff employed in all twenty-five domestic private and public sector commercial banks, including Islamic banks. The Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) technique was used to analyze the collected data. The findings suggest that mentoring functions not only enhance employee well-being in a direct relationship but also enhance employee well-being via increased career self-efficacy. Additionally, the results suggest that traditional mentoring has a significant and direct impact on employee well-being when compared to relational mentoring. Moreover, in terms of mediation through career self-efficacy, relational mentoring exhibits a stronger influence on employee well-being than traditional mentoring. The present study advances our knowledge of mentoring concepts by investigating both traditional and relational mentoring functions in the Eastern context. The last of the study presented the practical and theoretical implications and recommendations for future studies.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

The twenty-first century comprises economic instability and insecurity (Barley et al., Citation2017) and individual well-being is in danger (Di Fabio & Kenny, Citation2016). In a dynamic labor market, the employee’s health and happiness are an inevitable part of successful organizations. Employees’ state of health and well-being contributes to organizations’ performance (MacDonald, Citation2005). In the era of cut-throat competition and leading-edge technology, the employee’s well-being is affected by the various stakeholders in the individual’s broad social network as well as the employee’s adaptive capacity. Employee well-being depends on the individuals’ development and employers’ capabilities (Di Fabio, Citation2017; Di Fabio and Kenny, Citation2016) to assist them in dealing with the challenges and protect their well-being. United Nations Sustainable development goals for 2030 encompass the well-being and good health of employees (United Nations, Citation2015). Employee well-being is imperative for sustainable development goals. It is a state of complete physical, mental, social and spiritual well-being and not merely the absence of infirmity or disease (World Health Organization, Citation2022). Thus, well-being is central to human resources function and professional life (Di Fabio, Citation2017).

Bandura (Citation1997) put forward that persons form their efficacy through mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion and physiological and affective states. Mastery experience includes past positive and negative experiences that affect the individual’s future capability to carry out a particular job. Through vicarious experience, individuals can build their efficacy by observing others, i.e. mentors, to complete the task effectively. Verbal persuasion includes receiving positive and negative feedback from mentors to assist the individual’s ability to perform a particular task. Physiological and emotional well-being influence how a person feels about their ability to carry out a particular task. Hence, vicarious learning and verbal persuasion are strong predictors of individual efficacy, and ultimately, mentoring programs have a significant association with protégé mental health (Gill et al., Citation2018). Bandura (Citation1982) put forward that the two main self-efficacy sources are vicarious learning and verbal persuasion. Vicarious learning gains through observing other persons having harmonized interests, whereas verbal persuasion describes individuals being persuaded by other persons, such as mentors, to complete the task proficiently. Therefore, it is vital to examine the predictors that enhance career self-efficacy among protégé so that they can sustain their well-being in an unpredictable economic environment.

The literature highlights personal, behavioral and environmental factors as predictors of career self-efficacy, i.e. personality traits (Wille & De Fruyt, Citation2014), leadership (Latif et al., Citation2022), organizational career management (Runhaar et al., Citation2019) and perceived supervisor support (Chami-Malaeb, Citation2022). Mentor guidance is a predictor of career self-efficacy of protégé (Malik and Nawaz, Citation2022) and ultimately fosters their career development. A complementary fit perspective proposed by Ehrhardt and Ragins (Citation2019) offered a theoretical foundation for this study and considered a fit perspective between protégé requirements and mentor suppliers. The general support theory ignores the fit perspective. The protégé is attached to mentors to fulfill their needs, i.e. self-efficacy and well-being, which are fulfilled via the support offered by a mentor. A deep psychological connection between them is established when there is a fit perspective. Stephens (Citation2012) put forward that high-quality work connections are a vital source of bonding, vitality and engagement. Traditional mentoring connections are regarded as having moderate quality, wherein the mentor provides psychosocial and career-related assistance to the protégé (Kram, Citation1985). Conversely, relational connections are seen as high-quality connections, offering additional advantages such as advancement, learning and personal development for both protégés and mentors (Ragins, Citation2012). Most literature focused on traditional mentoring functions (Briscoe & Freeman, Citation2019; Gill et al., Citation2018; Ouerdian & Mansour, Citation2019). Few studies include both traditional and relational mentoring as antecedents of employee outcomes (Malik & Nawaz, Citation2022). Therefore, this study aims to investigate the effects of both traditional and relational mentoring functions on career self-efficacy, which ultimately contributes to the well-being of employees in Pakistan’s banking sector as they navigate the challenges of a dynamic environment. Additionally, this study explores the indirect relationship between mentoring functions and protégé well-being (purpose in life, job wellness, work-life balance and physical health). Finally, the study aims to determine whether traditional or relational mentoring functions have a stronger influence on employee well-being, as well as their indirect effects through career self-efficacy, using a complementary fit perspective (Ehrhardt & Ragins, Citation2019).

Furthermore, Pakistani banks are experiencing heightened competition as a result of expanding networks and technological advancements. In the face of such intense competition, employees in the banking sector face significant challenges in maintaining their well-being, especially in a developing country grappling with economic crises. Therefore, this study aims to gather empirical evidence, specifically within the Pakistani banking sector, to shed light on this issue.

2. Literature review

The relationship quality and positive connections with others, such as mentors both within and outside the workplace, facilitated individual advancement (Kram, Citation1985), securing better career opportunities for career progression (Feeney & Collins, Citation2014) sources for vitality, enrichment and individual’s learning to advance, flourish and prosper (Ragins & Dutton, Citation2017).

2.1. Mentoring functions

The mentor refers to a senior person who actively promotes the mentee’s career and psychosocial advancement (Forret & de Janasz, Citation2005). Traditionally, Kram (Citation1985) highlighted two mentoring functions, i.e. career and psychosocial, which are hierarchical and moderate-quality connections (Ragins & Verbos, Citation2017). Additionally, the authors also proposed a role-modeling mentoring function (Scandura, Citation1992; Scandura & Viator, Citation1994). Moreover, Ragins (Citation2012) proposed relational mentoring as having high-quality connections. It is an inter-reliant and generative connection that boosts learning, growth and advancement (Ragins, Citation2007).

The mentoring connections are classified into dysfunctional, traditional or relational connections (Ragins, Citation2012). Dysfunctional connections are considered as inferior quality associations in which bullying or sabotaging takes place (Eby & McManus, Citation2004); traditional connections are considered as moderate quality, where the mentor supplies psychosocial and career-related support to protégé (Kram, Citation1985); and relational connections is considered a high-quality connection, where both protégé and mentors attain added benefits such as advancement, learning and growth (Ragins, Citation2012). To gain maximum from the mentoring relationships, the protégé-mentor dyad must have a deep psychological attachment and high-quality connections are the source of connection, engagement and vitality.

2.2. Career self-efficacy

Hackett and Betz (Citation1981) proposed the notion of career self-efficacy, which is being studied in the career development literature. Self-efficacy refers to personal beliefs about their competencies. It refers to an individual’s belief that one is capable of adopting certain behaviors and actions to attain the planned objectives (Wu et al., Citation2012). Career self-efficacy is defined as the person’s belief in their ability to efficiently engage in career exploration and make decisions related to career advancement (Ireland & Lent, Citation2018). Further, it is considered a vital construct in career-related decision-making. Career selection and decisions ultimately affect the individual’s success and well-being.

The mentoring notion can be linked with two sources of self-efficacy (Bandura, Citation1997): verbal persuasion and vicarious learning. In verbal persuasion, the individual is being persuaded by the mentor to perform a particular task efficiently, whereas in vicarious learning, the protégé starts learning by observing the mentor. Further, the mentor is a high-ranking person in your professional network who has advanced knowledge and experience and is devoted to supporting protégé career advancement (Scandura & Williams, Citation2001). Building a professional network and having a mentor are key enablers to support protégé for career progression (Mate et al., Citation2018). Ultimately, successful career navigation fostered employee well-being. Moreover, employees with a robust sense of career self-efficacy experience enhanced employability (Malik & Nawaz, Citation2022) and achieving successful career development necessitates an elevated level of career self-management. Individuals who possess heightened career self-efficacy are better equipped to navigate their career trajectory successfully (Hirschi & Koen, Citation2021).

3. Employee well-being

Employee well-being means how well they are satisfied with their current working environment and how environmental factors influence an individual’s mental and physical health. A Gallup study of 2016, ‘The Economics of Well-being’, clearly demonstrates how employee well-being affects various outcomes, including profit, productivity, safety, engagement and turnover. Wise leaders not only recognize the value of employee well-being in maintaining a profitable firm.

Ilies et al. (Citation2015) put forward that employee well-being is recognized as a leading area of HRM research (Wright & Huang, Citation2012). Likewise, Zheng et al. (Citation2015) highlight that employee well-being is vital to the organization’s survival and growth. In the prior literature, various notions have been used to describe the concept of employee well-being, and systematic categorization has yet to be made. For example, subjective well-being at the workplace (Van de Voorde et al., Citation2012), work-life balance, happiness at work, purpose and meaning, work engagement, job burnout, job satisfaction, spiritual well-being (Paloutzian & Ellison, Citation1982), social well-being (Celma et al., Citation2018), happiness and life satisfaction (Hill et al., Citation2019; Sumner et al., Citation2015). Further, Khatri and Gupta (Citation2019) conceptualize well-being as purpose in life (PIL), work-life balance (WLB), job wellness (JW) and physical wellness (PW).

Workplace wellness is often associated with physical health, and employers offer various programs such as gym facilities (Purcell et al., Citation2019). Job wellness includes individuals who are satisfied with their current jobs, including working conditions, challenging roles and growth opportunities (Khatri & Gupta, Citation2019).

The traditional 9–5 and 5 working days seem old-fashioned, and employees are looking for more flexibility, better work-life balance and the ability to make more choices about their jobs. Reducing working hours leads to more focus on their jobs (World Economic Forum, Citation2022). Such a work environment makes it impossible for individuals to create a balanced work-life, which causes harmful health consequences (Lepsinger, Citation2018). The swift advancement of technology has fused the boundaries between personal and work life, necessitating immediate attention (Hassard et al., Citation2018). Work-life balance refers to social connectedness with family, society and colleagues, reinforcing that individuals are social beings who require personal assistance (Graham & Smith, Citation2022). Researchers have shown that a strong feeling of PIL is linked to higher physical and mental well-being (Thoits, Citation2012), longer lifespan (Hill et al., Citation2019), Individual well-being (Geraghty, Citation2018), better lifespan and healthy and meaningful life (Pfund & Hill, Citation2018).

3.1. Mentoring functions and employee well-being

Previous research has shown that mentoring has a variety of personal and career benefits for protégé. Mentoring leads to job search behavior (Kao et al., Citation2022), motivation to lead (Joo et al., Citation2018), career success (Day & Allen, Citation2004), employee performance (Malik & Nawaz, Citation2021a), career success (Malik & Nawaz, Citation2021b) and perceived employability (Malik & Nawaz, Citation2022). Louis and Freeman (Citation2018) indicate that mentor connections significantly affect graduate students and often provide them with the assistance they desperately need to graduate. Similarly, Briscoe and Freeman (2019) argue that informal mentorship is critical for navigating academic education and professional training for a future career. Moreover, Ouerdian and Mansour (Citation2019) put forward that receipt of support from a mentor leads to career success. Likewise, Gill et al. (Citation2018) found that mentoring programs are strong predictors of protégé and mentors’ mental health and well-being. Few past studies explored the traditional mentoring functions as an antecedent of employee outcomes (Briscoe & Freeman, 2019; Malik & Nawaz, Citation2021b; Ouerdian & Mansour, Citation2019). Further, few studies explored traditional and relational mentoring as antecedents of protégé internal and external employability (Malik & Nawaz, Citation2022); hence, the following hypotheses are proposed.

H1: Traditional mentoring is positively associated with protégé well-being.

H2: Relational mentoring is positively associated with protégé well-being.

3.2. Mediation of protégé career self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is an individual attribute and should be appraised in a specific field (Bandura, Citation2006). Additionally, verbal persuasion and vicarious learning are crucial for developing career self-efficacy. Protégé performs a task when being persuaded and also through observing the mentor (Bandura, Citation1982). Eby et al. (Citation2013) call for more research regarding antecedents, moderators, mediators and their outcomes of mentoring connections. In addition, St-Jean and Mathieu (Citation2015) state that mentoring is a predictor of employee self-efficacy and self-efficacy mediates the link between mentoring support and job satisfaction. Malik and Nawaz (Citation2021b) highlight that self-efficacy intervenes in mentoring functions and employee outcomes. Furthermore, Malik and Nawaz (Citation2022) state that career self-efficacy medicates the path between mentoring functions (traditional and relational) and the perceived employability of protégé. Hence, the following hypotheses are proposed.

H3: Career self-efficacy mediates the relationship between traditional mentoring and employee well-being.

H4: Career self-efficacy mediates the relationship between relational mentoring and employee well-being.

3.3. Theoretical framework

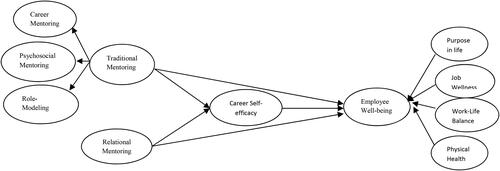

In this study, a complementary fit perspective provides a theoretical foundation (Ehrhardt & Ragins, Citation2019). Putting forward that protégé fulfills their requirements, i.e. self-efficacy and well-being support provided by a mentor. The relationship between protégé and mentor becomes idealistic when protégé needs equal mentor support supplies. Therefore, in this study, the TMF and RMF were explored as predictors of protégé career self-efficacy and well-being of protégé as shown in .

4. Methodology

Pakistani banking sector consists of public sector commercial banks, specialized banks, domestic private banks, foreign banks and microfinance banks. In this study, the employees working in all twenty-five domestic private and public sector commercial banks, including Islamic banks, were taken as the study population. A total of 153,396 permanent employees are employed in all twenty-five domestic private and public sector commercial banks, including Islamic banks, as of 31 December 2019 (State Bank of Pakistan, Citation2020). The number of permanent employees was extracted from banks’ annual audited financial statements. The sample size for the current study was determined through the sampling table provided by Krejcie and Morgan (Citation1970). The sample for the current study was three hundred eighty-four employees working in different departments, including branches, regional and general manager offices, regional credit administration departments and head office, including all hierarchical levels and in all the cities. Furthermore, to ensure that each bank in the sample represented its respective population, a proportional random sampling approach was employed. The sample was divided according to a ratio of bank employees to permanent employees working in twenty-five domestic Pakistani Banks. Previous studies conducted in the Pakistani banking sector indicate that the response rate was from 64% to 67% (Arif et al., Citation2020; Yan et al., Citation2020). Therefore, considering the response rate, six hundred survey-based questionnaires were distributed to the respondents by visiting them and after repeated follow-ups, four hundred twenty-six responses were received at the author-provided address via mail, few received scanned copies of the filled questionnaires via author email and WhatsApp, and the author also collected the filled responses directly by visiting the bank’s branches. A forty-two questionnaire was excluded due to pattern responses; incomplete responses led to three hundred eighty-four, a robust sample size for the study.

The respondents’ demographic profile is shown in . The male respondents were 87.60%, and 12.4% were 32.81 females. The respondents between 20 and 29 years were 29.17%, between 30 and 39 years were 32.81%, between 40 and 49 years were 27.86% and 10.16% were 50 years or older. The respondent’s education profile shows that 59.11% held a master’s or sixteen-year education, and 35.16% held MS/M.Phil has eighteen years of education, and 5.73% hold other professional education. Similarly, shows that from Habib Bank Limited, 53 respondents and similarly from MCB data gathered from 34 employees and so on as shown in the .

Table 1. Demographic information.

4.1. Measures

A five-point Likert scale was used in the present study. One represents strongly agree, and 5 represents strongly disagree. Precisely, to appraise traditional mentoring functions (career, psychosocial and role-modeling), the short-form scale (MFQ-9), three items for each proposed by Castro and Williams (Citation2004), was employed. Similarly, six items validated by Ayoobzadeh (Citation2018) were employed to appraise the relational mentoring functions. Likewise, an 11-item scale proposed by Kossek et al. (Citation1998) was used to appraise career self-efficacy. Further, employee well-being was measured using a multidimensional 14-item scale developed by Warr (Citation1990). It included three items for each physical health and purpose in life and four for job wellness and work-life balance.

5. Data analysis

The partial least squares-structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) technique was used to analyze the studied model (Ringle et al., Citation2015). The rationale for employing smart-PLS 3 is that it is an advanced and robust second-generation and variance-based technique (Hair et al., Citation2017). Additionally, this technique is used due to its capacity to concurrently evaluate all the underlying linkages in the proposed model (Hair et al., Citation2017; Kock & Hadaya, Citation2018). Given the study’s aim to predict the endogenous construct, it was deemed the right choice to use PLS-SEM (Hair et al., Citation2017). In PLS-SEM Modeling, the data distribution is not normally assumed, but it’s still valuable to examine the data distribution. The researcher visually examined the data through SPSS 27 using histograms and normal probability plots (Pallant, Citation2020). This examination revealed that the data of the study were normally distributed. The PLS-SEM technique was employed as it handles both reflective and formative constructs. All the constructs studied in the current study were reflective. In the current study, traditional mentoring functions and employee well-being were second-order constructs. A repetitive indicator approach was employed to analyze the reflective-reflective model. In the repeated indicators approach, the indicators of the first-order constructs are reused for the second-order construct.

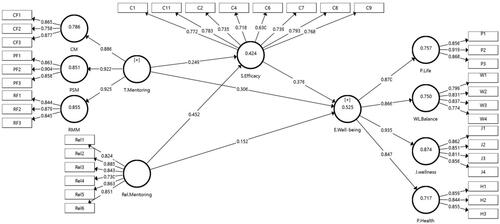

Hair et al. (Citation2017) highlight that the measurement model must be evaluated before the structural model. Further, all constructs used in this study were reflective and must be evaluated through their reliability and validity. Firstly, for individual items’ reliability, the outer loading of each studied construct was evaluated and was in the acceptable range between 0.625 and 0.919, hence retaining all the items (Duarte & Raposo, Citation2010; Hair et al., Citation2017). In the subsequent step, the internal consistency reliability was estimated via Cronbach’s alpha values and composite reliability (CR), which were higher than the threshold level of 0.70 (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation1988; Hair et al., Citation2017).

Further, the average variance extracted (AVE) criterion proposed by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) was used to appraise the convergent validity, which indicates that the AVE score was greater than the threshold of 0.5 (Chin, Citation1998; Hair et al., Citation2017). Further, discriminative validity was evaluated via the Fornell-Larcker test, heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio and cross-loadings (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Hair et al., Citation2017; Henseler et al., Citation2015) ().

Table 2. Reliability and validity statistics.

For the evaluation of discriminative validity, the Fornell–Larcker technique was used. According to this technique, the square root of AVE must be higher than the correlation among the studied constructs. The findings shown in indicate that values were higher than the correlation among latent constructs. Findings indicate that HTMT loading was below the threshold value of 0.85, as suggested by Henseler et al. (Citation2015) and Hair et al. (Citation2017), and details are shown in table (). To further authenticate the discriminative validity of all latent constructs, each measurement item must share the highest loading at their constructs compared with other study constructs. Details of cross-loading are present in . Overall; these results endorsed the criterion for reliability and validity of all measurement models studied.

Table 3. Fornell–Larcker test.

Table 4. Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio.

Table 5. Cross-loading.

In the following step, a structural model was estimated via bootstrapping. Firstly, the collinearity issue was assessed through the variance inflation factor (VIF) (Hair et al., Citation2017). The finding indicates that the VIF score was less than 5, demonstrating no collinearity.

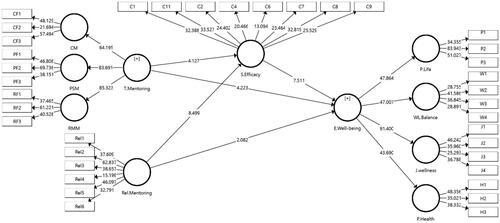

The finding reveals that the studied structural model has significant explanatory power, i.e. a value of R2 = 0.528 for employee well-being. Moreover, there is also significant explanatory power for career self-efficacy R2 = 0.424, as shown in . Further, the variance for career self-efficacy was moderate and substantial for employee well-being, as Hair et al. (Citation2017) suggested. Further, the R2 criterion is not sufficient for estimating the prudence of the structural model; therefore, the Q2 test through blindfolding was used to evaluate the predictive relevance of the structural model. The Q2 value other than zero indicates that the study’s structural models have significant predictive relevance for its endogenous variables (Hair et al., Citation2017). Results indicate that the studied structural model (Q2 = 0.271) shows a strong predictive relevance for employees’ well-being ().

Additionally, the findings show that the proposed path between traditional mentoring and employee well-being (β = 0.400; t = 5.004; p < .01) is positive and significant, indicating that H1 is supported. Similarly, For H2, a positive and significant relationship (β = 0.322; t-value = 4.267; p < .01) is found between relational mentoring functions and employee well-being. Additionally, results show that the link between traditional mentoring and career self-efficacy (β = 0.249; t-value = 4.127; p < .01) and also confirm the association between relational mentoring functions and career self-efficacy (β = 0.452; t-value = 8.499; p < .01).

Similarly, the study also evaluated the relationship between career self-efficacy and employee well-being (β = 0.376; t = 3.761; p < .01) as positive. In particular, indirect effect between traditional mentoring functions, career self-efficacy and employee well-being (β = 0.094; t-value = 3.761; p < .01) has confirmed that H3 is significant. Likewise, the path between relational mentoring functions, career self-efficacy and employee well-being (β = 0.170; t-value =5.359; p < .01) has confirmed that H4 is significant. Hence, career self-efficacy mediates the relationship between mentoring functions (traditional and relational) and employee well-being.

Additionally, provides evidence that traditional mentoring exhibits a significant and direct impact on employee well-being when compared to relational mentoring. Furthermore, relational mentoring has a strong effect on employee well-being, surpassing that of traditional mentoring through an indirect relationship mediated by career self-efficacy.

Table 6. Hypothesis testing.

However, it is still unclear whether mediation is partial or full mediation. Baron and Kenny (Citation1986) presented a conservative technique for mediation assessment. Conversely, a few authors, e.g. Zhao et al. (Citation2010), criticized this outdated technique. In the current study, we used the bootstrapping approach, as the mediation model suggested by Zhao et al. (Citation2010). Therefore, in the present study, we used a systematic mediator analysis process (Hair et al., Citation2017). According to this approach, the direct and indirect paths are significant and positive; therefore, complementary (partial mediation) is approved.

6. Discussion

The dyadic relationship between protégé and mentor becomes ideal as a life-changing connection. The current study aimed to investigate the direct association between mentoring functions and employee well-being and the indirect path via career self-efficacy.

The protégé and mentor have strong bonds among themselves when they have deep psychological connections. The foundation of these connections is based on the complementary fit perspective proposed by Ehrhardt and Ragins (Citation2019). The prior studies focused on general social support but overlooked the fit perspective between the needs of protégé and the support supply by the mentor. In the working relationship, the protégé connects with the mentor to accomplish their requirements, i.e. career self-efficacy. The complementary fit concept goes beyond the conventional perception of social support, which ignores the protégé’s needs or desires via these relationships (Shumaker & Brownell, Citation1984). The major need of the protégé is to enhance their well-being in the dynamic working environment. Protégé’s personal and professional development does not foster isolation and is considerably affected by the impacts of other stakeholders, i.e. mentors. The support of a mentor acts as an environmental factor and is vital for protégé well-being. The mentor acts as a resource reservoir and supplies vital support via mentoring functions (traditional and relational). This dyadic connection becomes idealistic when there is a match between protégé requirements and supplies of support by the mentor.

In a turbulent economic environment, the well-being of the protégé is at stake, and they must be proactive to secure their well-being. Thus, protégés must be more proficient in successful career navigation that matches with purpose in life, job wellness, work-life balance and physical health safety. Therefore, the protégé needs to develop their career self-efficacy via mentor assistance and eventually facilitate the protégé in their career navigation to protect their well-being in a dynamic labor market.

First, the present study aimed to investigate the association between mentoring functions (traditional and relational) and employee well-being (purpose in life, job wellness, work-life balance and physical health). The findings show that both traditional and relational mentoring functions are antecedents of protégé well-being. The TMF has a strong predictor (β = 0.400, p < .01) compared to RMF (β = 0.322, p < .01) on protégé well-being. The mentor supplies support to the protégé to protect their well-being. Hence, the protégé who secured more support from a mentor is better able to safeguard their well-being. Hence, the protégé must proactively be engaged in building relations with a mentor to get the utmost support required to protect their well-being. Further, the organization must devise mentoring programs to assist protégés in enhancing their well-being.

Next, this study seeks to explore the association between mentoring functions and the career self-efficacy of protégé. The results show that mentoring has a positive and significant link with the career self-efficacy of protégé. Mentor assistance is a prerequisite in constructing efficacy through vicarious learning and verbal persuasions. Furthermore, we argue that mentors are supposed to be a support reservoir. Protégé utilized these resources and ultimately aid them in building their efficacy and ultimately making career decisions efficiently to safeguard their well-being (Direnzo et al., Citation2015) and keenly engaged in finding better career opportunities (Herrmann et al., Citation2015) that harmonized with their life purpose, job wellness, work-life balance and secure physical health. We argued that a protégé having more mentor assistance is better able to secure internal career opportunities that match their interest, enhance the work-life balance and safeguard their physical and emotional health. The results indicate that TMF has (β = 0.249, p < .01) and RMF (β = 0.452, p < .01) on career self-efficacy of protégé. RMF produced more career self-efficacy than TMF. Thus, RMF is a greater antecedent than TMF of career self-efficacy of protégé, which is consistent with prior studies such as (St-Jean & Mathieu, Citation2015). The quality of the mentoring dyadic connection is varied. The TMF is believed to be an average-quality connection that is hierarchical and dyadic and offers career and psychosocial functions (Kram, Citation1985). In contrast, the RMF is considered a high-quality connection that focuses on mutual development (Ragins, Citation2012). These connections are illustrated as a perfect situation in which both gain mutual benefits from the relationship.

Lastly, the indirect effect of protégé career self-efficacy in the path of mentoring functions and employee well-being was investigated. The results show that the mediating effect of career self-efficacy was significant and positive, which is aligned with the previous study (St-Jean & Mathieu, Citation2015).

The findings offer empirical confirmation from the Pakistani perspective. Due to the increased branch network, there is strong competition among banks to increase their revenue. In a competitive environment, it’s always challenging for employees to safeguard their well-being. Through career self-efficacy, the individual becomes more efficient in their career navigation to secure their well-being in a competitive environment. The support of a mentor acts as a resource pool that aids protégé in constructing their efficiency. Finally, protégé having greater self-efficacy will be better able to take ownership of their career and career navigation to protect and enhance their well-being. The findings also put forward that career self-efficacy helps them in building precious capital, such as career self-efficacy via mentor support and ultimately helps the employees to match their career with their purpose in life, secure job wellness, balance the work-life and safeguard from physical harm.

7. Theoretical and practical implications

The current study presents few theoretical and practical implications.

The current study investigates the linkage between mentoring and the well-being of the protégé. The results indicate that mentoring is an antecedent of protégé well-being. Moreover, it was found that protégé can build their career self-efficacy through mentor support through vicarious learning and verbal persuasion that promote their well-being. RMF is a strong predictor of career self-efficacy of protégé compared to TMF, and RMF has a greater impact on employee well-being than TMF. The results indicate that mentoring functions generate identical outcomes and patterns. Hence, employers must hire mentors and retain them for mentoring programs to be implemented, managed and successful. In formal mentoring, the mentor and protégé meet on time regardless of the quality of connections, but this is not the case in informal mentoring. Furthermore, the personal learning approach, i.e. self-motivation and capacity, may be key elements in mentoring program effectiveness.

The existing research also has few practical implications. First, the protégé must participate in the mentoring programs. Before participating in mentoring programs, it is recommended that the needs of protégé must be systematically identified and then matched with the skills of the mentor. It will help organizations use their development resources in talent management efficiently and also be fertile for the protégé to gain maximum benefits from mentoring programs. The protégé must engage proactively in developing the relationship with the mentor to receive the most assistance for developing their self-efficacy that also protects and enhances their well-being.

There are a few limitations in this study; the mentoring connections were explored as predictors of protégé career self-efficacy and well-being. In future studies, other predictors such as occupation expertise, individual personality and leadership may be studied. Furthermore, specific leadership styles such as servant and ethical leadership might be explored as antecedents of employee well-being, as recent studies highlight that servant leaders nurture strong connections with followers and prioritize their well-being (Jiménez-Estévez et al., Citation2023; Ruiz‐Palomino et al., Citation2023). Further, young professional employability might be considered a dependent construct. Further, in this study, career self-efficacy was explored as a mediating variable; in the future, relational self-efficacy or career goal orientation might be explored in another context of the manufacturing or services sector, such as call centers or freelancers. In the current study, we studied the composite variables instead of the dimensions of constructs as, according to system theory, the combination must be studied instead of the dimension of constructs in isolation (Wilkinson, Citation2011). However, in future studies, the relationships between the dimension of mentoring and well-being may be explored. Finally, the current study is cross-sectional; future research should include a longitudinal study to analyze the impact of specific mentoring programs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Muhammad Kashif Nawaz

Dr. Muhammad Kashif Nawaz holds a Ph.D. in Business Administration from Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan. His research focuses on sustainable careers, organizational behavior and mentoring. His research papers have been published in various national and international journals. Additionally, he serves as a visiting lecturer at the University of Education, Lahore (Multan campus) and at National College Of Business Administration And Economics, Lahore (Multan campus). Apart from his academic endeavors, he has 11 years of professional experience in SME and commercial lending. He has worked at prominent Pakistani banks, including United Bank Ltd., Allied Bank Ltd. and Soneri Bank Limited.

Sadaf Nawaz

Ms. Sadaf Nawaz holds an M.Phil in Psychology from the Institute of Southern Punjab, Multan, with a specific interest in employee behavior.

Muhammad Saqib Nawaz

Dr. Muhammad Saqib Nawaz is a Lecturer at Noon Business School, University of Sargodha, Sargodha, Punjab, Pakistan. He earned his Ph.D. from BZU, Multan and specializes in teaching entrepreneurship, commerce and business management.

Sohail Ijaz

Mr. Sohail Ijaz serves as a lecturer at Government Associate College, Tibba Sultanpur, Punjab, Pakistan.

Samar Ejaz

Mr. Samar Ejaz is a Ph.D. Scholar, University of Utara, Malaysia.

References

- Arif, I., Aslam, W., & Hwang, Y. (2020). Barriers in adoption of internet banking: A structural equation modeling-neural network approach. Technology in Society, 61, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101231

- Ayoobzadeh, M. (2018). Leader development outcomes of relational mentoring for mentors. [Doctoral dissertation]. Concordia University

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723327

- Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Macmillan.

- Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(2), 164–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00011.x

- Barley, S. R., Bechky, B. A., & Milliken, F. J. (2017). The changing nature of work: Careers, identities, and work lives in the 21st century. Academy of Management Discoveries, 3(2), 111–115. https://doi.org/10.5465/amd.2017.0034

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Briscoe, K. L., & Freeman S., Jr. (2019). The role of mentorship in the preparation and success of university presidents. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 27(4), 416–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2019.1649920

- Castro, S. L., & Williams, E. A. (2004). Validity of Scandura and Ragins’ (1993) multidimensional mentoring measure: An evaluation and refinement. Paper Presented at the meeting of the Southern Management Association, San Antonio, TX.

- Celma, D., Martinez-Garcia, E., & Raya, J. M. (2018). Socially responsible HR practices and their effects on employees’ well-being: Empirical evidence from Catalonia, Spain. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 24(2), 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2017.12.001

- Chami-Malaeb, R. (2022). Relationship of perceived supervisor support, self-efficacy and turnover intention, the mediating role of burnout. Personnel Review, 51(3), 1003–1019. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-11-2019-0642

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Modern Methods for Business Research, 295(2), 295–336.

- Day, R., & Allen, T. D. (2004). The relationship between career motivation and self-efficacy with protégé career success. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64(1), 72–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(03)00036-8

- Di Fabio, A. (2017). The psychology of sustainability and sustainable development for well-being in organizations. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1534. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01534

- Di Fabio, A., & Kenny, M. E. (2016). From decent work to decent lives: Positive Self and Relational Management (PS&RM) in the twenty-first century. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 361. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00361

- Direnzo, M. S., Greenhaus, J. H., & Weer, C. H. (2015). Relationship between protean career orientation and work–life balance: A resource perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(4), 538–560. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1996

- Duarte, P. A. O., & Raposo, M. L. B. (2010). A PLS model to study brand preference: An application to the mobile phone market. In Handbook of partial least squares (pp. 449–485). Springer.

- Eby, L. T., & McManus, S. E. (2004). The protégé’s role in negative mentoring experiences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65(2), 255–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2003.07.001

- Eby, L. T. d T., Allen, T. D., Hoffman, B. J., Baranik, L. E., Sauer, J. B., Baldwin, S., Morrison, M. A., Kinkade, K. M., Maher, C. P., Curtis, S., & Evans, S. C. (2013). An interdisciplinary meta-analysis of the potential antecedents, correlates, and consequences of protégé perceptions of mentoring. Psychological Bulletin, 139(2), 441–476. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029279

- Ehrhardt, K., & Ragins, B. R. (2019). Relational attachment at work: A complementary fit perspective on the role of relationships in organizational life. Academy of Management Journal, 62(1), 248–282. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.0245

- Feeney, B. C., & Collins, N. L. (2014). A theoretical perspective on the importance of social connections for thriving. In M. Mikulincer & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Mechanisms of social connection: From brain to group (pp. 291–314). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14250-017

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics.

- Forret, M., & de Janasz, S. (2005). Perceptions of an organization’s culture for work and family: Do mentors make a difference? Career Development International, 10(6/7), 478–492. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430510620566

- Geraghty, S. (2018). Workplace well-being. Nice to have or necessity? www.business2community.com/health-wellness/workplace-well-being-nice-to-have-or-a-necessity-02047285 (accessed December 09, 2022).

- Gill, M. J., Roulet, T. J., & Kerridge, S. P. (2018). Mentoring for mental health: A mixed-method study of the benefits of formal mentoring programmes in the English police force. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 108, 201–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.08.005

- Graham, J. A., & Smith, A. B. (2022). Work and Life in the Sport Industry: A Review of Work-Life Interface Experiences Among Athletic Employees. Journal of Athletic Training, 57(3), 210–224. https://doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-0633.20

- Hackett, G., & Betz, N. E. (1981). A self-efficacy approach to the career development of women. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 18(3), 326–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(81)90019-1

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Hassard, J., Teoh, K. R., Visockaite, G., Dewe, P., & Cox, T. (2018). The cost of work-related stress to society: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000069

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Herrmann, A., Hirschi, A., & Baruch, Y. (2015). The protean career orientation as predictor of career outcomes: Evaluation of incremental validity and mediation effects. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 88, 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.03.008

- Hill, P. L., Edmonds, G. W., & Hampson, S. E. (2019). A purposeful lifestyle is a healthful lifestyle: Linking sense of purpose to self-rated health through multiple health behaviors. Journal of Health Psychology, 24(10), 1392–1400. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317708251

- Hirschi, A., & Koen, J. (2021). Contemporary career orientations and career self-management: A review and integration. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 126, 103505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103505

- Ilies, R., Pluut, H., & Aw, S. S. (2015). Studying employee well-being: Moving forward. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(6), 848–852. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2015.1080241

- Ireland, G. W., & Lent, R. W. (2018). Career exploration and decision-making learning experiences: A test of the career self-management model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 106, 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.11.004

- Jiménez-Estévez, P., Yáñez-Araque, B., Ruiz-Palomino, P., & Gutiérrez-Broncano, S. (2023). Personal growth or servant leader: What do hotel employees need most to be affectively well amidst the turbulent COVID-19 times? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 190, 122410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122410

- Joo, M. K., Yu, G. C., & Atwater, L. (2018). Formal leadership mentoring and motivation to lead in South Korea. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 107, 310–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.05.010

- Kao, K. Y., Hsu, H. H., Rogers, A., Lin, M. T., Lee, H. T., & Lian, R. (2022). I see my future!: Linking mentoring, future work selves, achievement orientation to job search behaviors. Journal of Career Development, 49(1), 232–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845320926571

- Khatri, P., & Gupta, P. (2019). Development and validation of employee well-being scale–a formative measurement model. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 12(5), 352–368. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-12-2018-0161

- Kock, N., & Hadaya, P. (2018). Minimum sample size estimation in PLS‐SEM: The inverse square root and gamma‐exponential methods. Information Systems Journal, 28(1), 227–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12131

- Kossek, E. E., Roberts, K., Fisher, S., & Demarr, B. (1998). Career self‐management: A quasi‐experimental assessment of the effects of a training intervention. Personnel Psychology, 51(4), 935–960. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1998.tb00746.x

- Kram, K. E. (1985). Improving the mentoring process. Training & Development Journal, 39(4), 40–43.

- Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447003000308 (accessed March 29, 2019).

- Latif, K. F., Ahmed, I., & Aamir, S. (2022). Servant leadership, self-efficacy and life satisfaction in the public sector of Pakistan: exploratory, symmetric, and asymmetric analyses. International Journal of Public Leadership, 18(3), 264–288. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPL-11-2021-0058

- Lepsinger, R. (2018). How to achieve ultimate work-life balance, available at: www.business2community.com/health-wellness/how-to-achieve-the-ultimate-work-life-balance-02114823

- Louis, D. A., & Freeman S., Jr. (2018). Mentoring and the passion for propagation: Narratives of two Black male faculty members who emerged from higher education and student affairs leadership. Journal of African American Males in Education (JAAME), 9(1), 19–39.

- Macdonald, L. A. (2005). Wellness at work: protecting and promoting employee health and well-being. CIPD Publishing.

- Malik, M. S., & Nawaz, M. K. (2021a). The relationship between mentoring functions and employee performance: mediating effects of protégé relational self-efficacy. Annals of Social Sciences and Perspective, 2(2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.52700/assap.v2i2.50

- Malik, M. S., & Nawaz, M. K. (2021b). Relationship between mentoring functions and career success with mediating role of career resilience: evidence from Pakistani banking sector. Bulletin of Business and Economics (BBE), 10(3), 89–100.

- Malik, M. S., & Nawaz, M. K. (2022). Fostering employability through mediation of protégé career self-efficacy of Pakistani bankers. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2141672. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2141672

- Mate, S. E., McDonald, M., & Do, T. (2018). The barriers and enablers to career and leadership development: An exploration of women’s stories in two work cultures. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 27(4), 857–874. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-07-2018-1475

- Ouerdian, E. G. B., & Mansour, N. (2019). The relationship of social capital with objective career success: the case of Tunisian bankers. Journal of Management Development, 38(2), 74–86.

- Paloutzian, R. F., & Ellison, C. W. (1982). Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS) [Database record]. APA PsycTests.

- Pallant, J. (2020) SP SS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using IBM SP SS. McGraw-hill education (UK).

- Pfund, G. N., & Hill, P. L. (2018). The multifaceted benefits of purpose in life. In the International Forum for Logotherapy, 41(3), 27–37.

- Purcell, R., Gwyther, K., & Rice, S. M. (2019). Mental health in elite athletes: increased awareness requires an early intervention framework to respond to athlete needs. Sports Medicine-Open, 5(1), 1–8.

- Ragins, B. R. (2007). Diversity and workplace mentoring relationships: A review and positive social capital approach. In The Blackwell handbook of mentoring: a multiple perspectives approach (pp. 281–300).

- Ragins, B. R. (2012). Understanding diversified mentoring relationships: Definitions, challenges and strategies. In Mentoring and diversity (pp. 35–65). Routledge.

- Ragins, B. R., & Dutton, J. E. (2017). Positive relationships at work: An introduction and invitation. In Exploring positive relationships at work (pp. 2–24). Psychology Press.

- Ragins, B. R., & Verbos, A. K. (2017). Positive relationships in action: Relational mentoring and mentoring schemas in the workplace. In Exploring positive relationships at work (pp. 91–116). Psychology Press.

- Ringle, C., Da Silva, D., & Bido, D. (2015). Structural equation modeling with the SmartPLS. Bido, D., da Silva, D., & Ringle, C. (2014). Structural Equation Modeling with the Smartpls. Brazilian Journal of Marketing, 13(2), 56–73.

- Ruiz‐Palomino, P., Linuesa‐Langreo, J., & Elche, D. (2023). Team‐level servant leadership and team performance: The mediating roles of organizational citizenship behavior and internal social capital. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility, 32(S2), 127–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12390

- Runhaar, P., Bouwmans, M., & Vermeulen, M. (2019). Exploring teachers’ career self-management. Considering the roles of organizational career management, occupational self-efficacy, and learning goal orientation. Human Resource Development International, 22(4), 364–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2019.1607675

- Scandura, T. A. (1992). Mentorship and career mobility: An empirical investigation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13(2), 169–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030130206

- Scandura, T. A., & Viator, R. E. (1994). Mentoring in public accounting firms: An analysis of mentor-protégé relationships, mentorship functions, and protégé turnover intentions. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 19(8), 717–734. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(94)90031-0

- Scandura, T. A., & Williams, E. A. (2001). An investigation of the moderating effects of gender on the relationships between mentorship initiation and protégé perceptions of mentoring functions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 59(3), 342–363. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1809

- Shumaker, S. A., & Brownell, A. (1984). Toward a theory of social support: Closing conceptual gaps. Journal of Social Issues, 40(4), 11–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1984.tb01105.x

- St-Jean, É., & Mathieu, C. (2015). Developing attitudes toward an entrepreneurial career through mentoring: The mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Journal of Career Development, 42(4), 325–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845314568190

- State Bank of Pakistan. (2020). List of scheduled banks, microfinance banks, development finance institutions & Investment Banks. https://www.sbp.org.pk/publications/anu_stats/2020/Part-4/15-Appendix.pdf

- Stephens, J. P. (2012) High-quality connections [Doctoral dissertation]. Oxford University.

- Sumner, R., Burrow, A. L., & Hill, P. L. (2015). Identity and purpose as predictors of subjective well-being in emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 3(1), 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696814532796

- Thoits, P. A. (2012). Role-identity salience, purpose and meaning in life, and well-being among volunteers. Social Psychology Quarterly, 75(4), 360–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272512459662

- United Nations. (2015). Sustainable development goals. http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

- Van De Voorde, K., Paauwe, J., & Van Veldhoven, M. (2012). Employee well‐being and the HRM–organizational performance relationship: a review of quantitative studies. International Journal of Management Reviews, 14(4), 391–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00322.x

- Warr, P. (1990). The measurement of well‐being and other aspects of mental health. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(3), 193–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00521.x

- Wilkinson, L. A. (2011). Systems theory. In Encyclopedia of child behavior and development. Springer. (pp. 1466–1468).

- Wille, B., & De Fruyt, F. (2014). Vocations as a source of identity: Reciprocal relations between Big Five personality traits and RIASEC characteristics over 15 years. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(2), 262–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034917

- World Economic Forum. (2022). Could we soon be seeing the end of 9-5? https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/04/9-to-5-work-2022/

- World Health Organization. (2022). Mental health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health#tab=tab_1

- Wright, T. A., & Huang, C. C. (2012). The many benefits of employee well‐being in organizational research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(8), 1188–1192. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1828

- Wu, S. Y., Wang, S. T., Liu, F., Hu, D. C., & Hwang, W. Y. (2012). The influences of social self-efficacy on social trust and social capital–A case study of Facebook. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET, 11(2), 246–254.

- Yan, R., Basheer, M. F., Irfan, M., & Rana, T. N. (2020). Role of psychological factors in employee wellbeing and employee performance: An empirical evidence from Pakistan. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 29(5), 638.

- Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G.Jr., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197–206. https://doi.org/10.1086/651257

- Zheng, X., Zhu, W., Zhao, H., & Zhang, C. (2015). Employee well‐being in organizations: Theoretical model, scale development, and cross‐cultural validation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(5), 621–644. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1990