Abstract

This study intended to examine visual perception (VP) of pictorial signage of public toilets including perceptual differences among the subjects in the study. The importance of the study is that in making meaning process of toilet signage people can misinterpret the signage, in particular, if the figures depicted on the signage are not in common basic forms such as the male figure illustrated by a man wearing a pair of trousers and the female figure shown by a woman wearing a dress. People’s confusion to interpret male and female toilet signs has also been noted in previous studies and explained that it might cause hesitation to determine male or female toilet cubicle. In the study in this paper, the pictorial signage examined were some examples of toilet signage depicted as stylised forms of men and women. The signage and a visual analogue scale (VAS), which were used to test the four parameters of the study, were presented to 36 undergraduate university students, who were the subjects of the study. The parameters of the study are the level of difficulty of identifying the toilet signage, the level of difficulty of differentiating toilet cubicles based on gender difference, the level of the probability of error to enter the toilet cubicle regarding gender difference, and the level of embarrassment if entering the inappropriate toilet cubicle. The study employed theories of VP and visual social semiotics (VSS) as the integration of them can help us to explain viewers’ perceptual processes of the signage, including their visual perceptual differences, and to reveal meanings of the signage. This study showed that the application of VAS is beneficial to collect the subjective judgement of the subjects about the signage with regard to the four parameters. In addition, the integrated approach comprising the theories of VP and VSS is useful to explain the subjects’ understanding of the public toilet signage and potential meanings of the signage.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Public toilet signage can be confusing as the pictures depicted in such signage can be interpreted differently by different viewers. It is therefore important to explore how people interpret the signage and why they misinterpret them even though the signage have been designed by referring to certain guidelines and have been evaluated using certain tools which are concerned with the ease of understanding of the signage. However, it is not easy to collect information on viewers’ perception about the signage since it cannot be easily measured. A visual analogue scale (VAS), which is still rarely used in Media or Communication Studies research, has the potential to be used to gather information about this viewers’ understanding. To investigate their responses and meanings of the signage, then, we can apply the advantage of theories of visual perception (VP) and visual social semiotics (VSS).

1. Introduction

Sign systems of facilities in public places are sometimes confusing for some people which can then lead to misinterpretation and incorrect usage of such facilities. Toilet signage is one of the examples of sign system and is considered as one of the most common signage which exist in the contemporary era (Ciochetto, Citation2003, p. 209). However, it is often found that toilet signage is difficult to understand indicating the message from designers of the signage cannot be easily understood by their viewers. Some studies showed that in some cases toilet signage is often confusing and unclear because of several reasons, for example, the signage contains too much information and the elements of the signage illustrates shape, colour, line, tone, and pattern which are not easy to understand. The common impact of presenting “confusing” signs was that it caused hesitation, ambivalence, and anxiety in viewers of the signs to enter and use and the toilet (Afacan & Gurel, Citation2015; Ng, Siu, & Chan, Citation2012; Johannessen, Citation2013; Sutherland, Citation2016). Some people might ask someone before they enter toilet cubicles to verify meanings of the sign systems, for example, whether the provided pictures on the signage refers to males or females. People might understand easily the examples of pictorial signage in Figures and . However, for some other viewers these examples might not be easy to interpret. This might be due to the transformation of the signs from their original shapes or the depiction of non-human figures in the signage. The viewers might understand that the left sign in indicates an image of a woman and the right sign refers to an image of a man. They might interpret that the left sign is derived from a female human body and the right sign is from a male human body, as shown in . To interpret the signage in the viewers might differentiate male and female chickens (i.e. rooster and hen), and then apply this gender difference to define the images in this signage. When they distinguish the images of the chickens, they might compare some important characteristics of male and female chickens, for example their heads (e.g. comb and wattle) and tails. After determining the male and female chickens, they use this knowledge to imagine the images of human, and then they recognise that the left sign refers to female and the right sign denotes male, as illustrated in . The images of a man and a woman in Figures and are some examples of human figure which are likely to arise in the human mind about male and female bodies. Apart from those examples of signage, some other pictorial signage of public toilets may be combined with words due to the issue of the effectiveness of the pictorial image per se, as mentioned by Ciochetto (Citation2003, p. 209).

Figure 1. An example of pictorial signage of public toilet. Adapted from “Toilet signage as effective communication” by L. Ciochetto (Citation2003), Visible Language, 37 (2), p. 218.

Figure 2. An example of pictorial signage of public toilet. Adapted from “Toilet signage as effective communication” by L. Ciochetto (Citation2003), Visible Language, 37 (2), p. 218.

In the interpretation process of the pictorial signage the viewers might use their knowledge and experience to make meaning the signs which are socially conditioned during the life time of the viewers (Trisnawati, Citation2012, pp. 107–109). For example, they might know that the left sign in refers to women as, according to their knowledge, the shape of this sign refers to females, as indicated by human wearing a skirt. Our knowledge about it is socially conditioned in our society that clothes are related to gender where generally skirts tend to be worn by women (Craik, Citation2009, p. 140). However, different viewers’ level of knowledge and experience influences the way they make meaning the signage which is then possible to cause misinterpretation.

Although pictorial signage of public toilets might cause misinterpretation, before placing them in public places designers of the signage have usually conducted usability testing to examine their effectiveness. Usability itself is generally concerned with the effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction with which specified users can achieve specified goals in particular environments. Effectiveness relates to the capability of users to perform the intended task. Efficiency refers to the total time taken by the users to carry out the task. Satisfaction of the users relates to acceptability and comfort level of the system to the users, and they prefer one system over another (ISO DIS 9241–11 in Faulkner, Citation2000, pp. 7–8). In terms of the interaction between viewers and the signage, effectiveness refers to the ability of the viewers to make meaning the signage, for example, which signs in the two examples above refers to male or female. If the viewers are able to make meaning the signage for a certain time, it means they are able to accomplish the task. This refers to efficiency. When the viewers can make meaning the signage within certain time and they are considered to be convenient with them, this relates to satisfaction. It is therefore usability of the signage refers to “ease of use” of it by the viewers together with its “usefulness”.

Usability of pictorial signage relates to the way the viewers make meaning the signage in a way that when they see it they also interpret its meanings. The viewers’ meaning-making process of the toilet signage is considered as a visual perception (VP) process which, according to Cantor (Citation2014, p. 1), is a mental process involving the formation and interpretation of mental images. Mental image is the representation about something which exists in the viewers’ mind. This representation is about the physical world outside the viewers. Their VP process is influenced by their knowledge and experience about the signage. Their visual knowledge and experience is what they have seen in the past. This is what Arnheim (Citation1974, p. 48) said about “the influence of the past” where what people have seen in the past influences what they see now. Differences of VP among the viewers might due to different mental processes among them influenced by their different knowledge and experience about the signage.

Investigating VP of pictorial signage of public toilets is important as previous studies on perceptual process of visual images have not focused on pictorial signage of public toilets, in particular the signage which are depicted as human figures, and have not used a visual analogue scale (VAS) which is combined with the use of the theories of VP and visual social semiotics (VSS). Previous studies on VP, however, have focused on several aspects ranging from visual components to visual perceptual learning. In relation to visual components, the previous studies have discussed, for example, the role of colour to identify graphic symbols (Alant, Kolatsis, & Lilienfeld, Citation2010), visual–verbal relationships (Bloomberg, Karlan, & Lloyd, Citation1990), and textual features (Hideyuki, Shunji, & Takashi, Citation1978). Cultural and social aspects have also been paid attention in VP research, for example, gender stereotypes in the discourse of public educational spaces (Romera, Citation2015), consumers’ perception of symbols and health-related information (Carrillo, Fiszman, Lähteenmäki, & Varela, Citation2014), perceptual grouping cues in artists and non-artists by viewing grids of dots (Ostrofsky, Kozbelt, & Kurylo, Citation2013), and viewers’ different cultural background and the perception of symbols (Chu & Martinson, Citation2003). Learning process has also been mentioned in the previous studies, for example, relationships between development of children’s VP and their maturity and their drawings of human picture (Canel & Yukay Yüksel, Citation2015), visual reading skills of first grade students in relation to the use of fictional elements and vocabularies (Bas & Örs, Citation2015), behavioural findings of visual learning with physiological and anatomical data (Ahissar & Hochstein, Citation2004), and the impact of attention and perceptual grouping on statistical learning of visual shapes (Baker, Olson, & Behrmann, Citation2004). In addition, some other aspects have also been paid attention in VP research, for example, its relation to reward given to viewers on space- and object-based selection (Shomstein & Johnson, Citation2013).

In addition to those studies, although several studies examine toilet signage as the object of investigation, such as the studies conducted by Afacan and Gurel (Citation2015), Ng et al. (Citation2012), Johannessen (Citation2013), and Sutherland (Citation2016), no previous studies has examined viewers’ VP and their perceptual differences about the pictorial signage of public toilets which are depicted as human figures using VAS. Afacan and Gurel (Citation2015) focused on the use of toilet as a social activity and how the design of public toilet including its sign systems affects the way people use the land and participate in social life. Ng et al. (Citation2012) concentrated on the importance of using the stereotype production method for collecting user ideas during the symbol design process to examine the influence of user factors and symbol referents on public symbol by asking the participants of the study to draw public facility symbols. Johannessen (Citation2013) emphasised on toilet signs as graphic phenomena by highlighting the ways in which toilets are placed in the urban environment using graphic signs conducted by a corpus-based approach. Sutherland (Citation2016) focused on symbols in public facilities, where symbols in toilet signage are one of her objects of study. Her study examined such symbols which might be difficult to understand and examined the feasibility of designing symbols that might be more effective for their viewers. Although the two last mentioned studies discussed toilet signage, the aims and methodologies of those studies are different from the study in this paper. Johannessen (Citation2013) offered a tentative approach to corpus-based studies of graphic form which then proposed two formal systems of graphic form in public toilet signs, which are shape and enshapening. The image corpus (i.e. photographs of pictograms from the doors of public toilets) was collected by a group of university students, who were also the participants of the study who gave responses to the interpretation about the image corpus. Besides, Sutherland (Citation2016) used qualitative methodology to discover the impact of different symbols and investigate design factors which might influence viewers’ interpretation about the symbols. Data of this qualitative study were from focus groups which provided information about social contexts which might influence viewers’ interpretation about the meanings of the symbols.

From the examples of previous study, it is clearly seen that those studies have not discussed VP of pictorial signage of public toilets, in particular, exploring viewers’ subjective response about the signage which is believed to be able to show characteristics of the response which cannot easily be directly measured. This is an important omission because, as mentioned earlier, toilet signage is considered as one of the most common sign systems which exist in the contemporary era. Moreover, Ciochetto (Citation2003, p. 213) mentioned that because of the existence of public toilets, the signage, which is commonly indicated by images of men and women, are needed as a means of identification of such facilities. Therefore, examining VP of the signage consisting of male and female images is indispensable as, according to Ciochetto (Citation2003, p. 210), in most culture toilets are differentiated by gender.

In the study in this paper we examined toilet signage depicted in the form of “derivative” images of men and women as these kinds of image have the potential to cause misinterpretation. We focused on this kind of toilet signage to narrow this study although toilet signage might also indicate location of the toilet, facilities in the toilet, and etcetera. Also, we used the term pictorial signage to indicate toilet signs since the object of this study is the images of men and women, even though some studies called them symbol (e.g. Shen, Woolley, & Prior, Citation2006; Seok-Seo et al., Citation2010) and icon (e.g. Wright, Lickorish, & Hull, Citation1990; Dormann, Citation1994; Ingrey, Citation2012; Motel, Citation2016; Motel & Peck, Citation2018). The term symbol is commonly used to call something visual which stands for something other than itself (Hartley, Citation2002, p. 223), including to call toilet signage in public places. Symbol and icon, according to Charles Sanders Peirce’ categorisation of signs, together with index are the three semiotic categories which have meanings based on the things referred to by the signs. Briefly, toilet signs refer to icon if they resemble the object, which is the toilet. The signs refer to iconic function when they represent toilet users, which are men and women. Toilet signs refer to index if the signs are combined with a direct link to connect the depicted image and the location, as the object. Toilet signs might also represent facilities of activities of using toilet which relate to a symbolic function representing cultural convention and thus refers to symbol (Ciochetto, Citation2003, p. 209). Although toilet signage can be icon, index, or symbol, in this paper the term pictorial signage is used to refer to toilet signs as in general the signs mainly consist of visual images which are used cross-culturally.

This study examined viewers’ VP of pictorial signage of public toilets regarding the difficulty of identifying the signage, the difficulty of distinguishing toilet cubicles based on gender difference, the level of probability of error to enter the toilet cubicles with regard to gender difference, and the level of embarrassment if the viewers entered the inappropriate toilet cubicle due to their misinterpretation about the male and female images in the signage. The study also investigated visual perceptual differences between the male and female viewers about the signage. Data were collected from 36 students of Faculty of Art and Design, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Indonesia. We used a VAS to collect their responses, as subjective judgement, about the signage. Data were analysed by applying theories of VP (Arnheim, Citation1974) and VSS (Jewitt & Oyama, Citation2001; Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation1998) to explain subjects’ perceptual processes of the signage and to reveal meanings of the signage. This study can then contribute to the current discussion of arts and humanities where communicating visually is not merely sending and receiving messages visually through certain media, but it includes people’s ability to understand their surrounding to interpret meanings of the images by considering certain social and cultural contexts.

In the next section we will describe a short description of theories of VP and VSS, which is applicable to this study, followed by methods, results, and discussion of the study. The final part of this paper is conclusions including implications of the study.

2. Theories of VP and VSS for pictorial signage of public toilets

A combination of theories of VP and VSS are considered appropriate to examine viewers’ perception of pictorial signage of public toilets since theories of VP can help us to explain a mental process involving the formation and interpretation of mental images. Also, VSS can be used to reveal meanings of visual images and to examine relevant aspects of social relations of those who participated in communication and consider production of message as a text with relevant contexts. In addition, some of the Kress and van Leeuwen’s concepts of social semiotics of visual images are in line with the Arnheim’s theory of VP since some of the concepts in VSS refer to the Arnheim’s theory. In general, the idea of VSS relates to the Arnheim’s VP about the dynamic of the visual experience of the viewers in a way that in VSS the meaning of the visual images is shaped and construed by social, cultural, and historical factors. The meaning, according to van Leeuwen (Citation2005), is socially made and changeable through social interactions. It is therefore the integration of the theories of VP and VSS was suitable for this study since it can help us to explain experience of VP of the viewers about the pictorial signage.

The relevance of the Arnheim’s theory of VP to our study is that the theory explains the fundamental ideas of visual experience where viewers’ interpretation about the pictorial signage is not only about the composition of the toilet signage itself such as line, shape, and colour, but also is influenced by viewers’ knowledge about the signage and its visual elements (Arnheim, Citation1974, p. 11). Also, his concepts about balance, shape, light, and colour are applicable to this study because the toilet signage comprises these visual elements which interact with each other forming a visual composition of the signage.

The appropriateness of VSS in our study is due to its strength to reveal meanings of visual objects consisting of representational, interactive, and compositional meanings (Jewitt & Oyama, Citation2001; Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation1998). The concept of representational meaning was considered appropriate for this study as this concept discusses meanings which are conveyed by element depicted. For example, the meaning of an image composition is defined by particular characteristics including colour, size, position, etc. (Jewitt & Oyama, Citation2001, pp. 141–145; Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation1998, pp. 79–118). This concept can then help us to understand that pictorial signage of public toilets illustrates stable essences. The concept of interactive meaning was useful in this study as it can be used to explain that meanings are produced from interactions between the viewers of images and the images themselves. Relationships between the viewers and the images might be in an imaginary relation where visual elements of an image composition can be considered to invite the viewers to look at the image composition (Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation1998, pp. 122, 124). This concept can then be beneficial to this study to examine how the pictorial signage relate to their viewers. The concept of compositional meaning was taken into account in this study since this concept can help us to examine how the pictorial signage, as a visual composition, is composed. For example, in a visual composition some elements can be made more eye-catching than others by means of size, colour contrast, or tonal contrast (Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation1998, pp. 122–124).

Apart from their strengths, theories of VP and VSS have limitations. Some interpretation can be subjective while objective at the same time. In particular, in the application of VSS there might be difficulties in examining relationships between visual elements and the viewers (Trisnawati, Citation2012, p. 141). Despite their limitations, their strengths outweigh this limitation so that theories of VP and VSS are valuable to examine the viewers’ interpretation of pictorial signage as they can help us to explain perceptual process in the viewer interactions with the signage as well as revealing their potential meanings. Exploring this perceptual process can then support the results obtained from the measurement instrument (i.e. a VAS) given to the viewers of the signage in this study.

3. Methods

To examine the viewers’ VP of pictorial signage of public toilets including visual perceptual differences among the viewers, we conducted the following experiment.

3.1. Participants

The research sample, who were the viewers of the pictorial signage, comprised a group of 36 undergraduate students of Faculty of Art and Design, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Indonesia. They were enrolled in a course on human factors in design. The 36 participants, as the subjects of the study, consisted of 15 males and 21 females, aged between 18 and 22 years (M = 19.97, SD = 0.73). Since the sample of viewers was largely homogenous, the 36 subjects were considered sufficient for this study as, according to Sarantakos (Citation2004, pp. 170–171), the size of the sample depends on characteristics of the whole population, and if the sample of population is homogenous, a small sample is considered sufficient. Also, the students from this faculty were assumed to have a reasonably understanding of derivative images. Their knowledge of visual subject matter would provide them the tools with which to examine their interaction with the derivative pictorial signage. The sample in this study can then provide opportunities for the researchers to focus in detail on the subjects being studied.

3.2. Design and stimuli

The experiment was based on questions about the pictorial signage on a questionnaire employed a VAS, which allowed the subjects to mark the scale ranged from 0 to 100, to know their responses about the pictorial signage (PS) depicted in (i.e. PS A, PS B, PS C, and PS D). The questionnaire comprised four questions which explored the level of difficulty of identifying the toilet signage, the level of difficulty of differentiating toilet cubicles based on gender difference, the level of probability of error to enter the toilet cubicle regarding gender difference, and the level of embarrassment if they entered the inappropriate toilet cubicle. These four questions were then the parameters of this study. The questions and the pictorial signage samples were considered appropriate to examine VP of pictorial signage of public toilets, including visual perceptual differences among the subjects, as the questions and the signage were considered to provide sufficient information to collect data on how they recognised the signage in public places including identifying the male and female toilet cubicles and to what extent they would enter the inappropriate toilet cubicle with regard to gender classification as well as the extent to which they would be ashamed if they entered the inappropriate toilet cubicle.

Figure 5. Pictorial signage of public toilet used in the experiment of the study. Adapted from “Go where? Sex, gender, and toilet” [Blog post] by Marissa (Citation2010), September 2, Retrieved 15 October 2015, from https:/thesocietypages.org/socimages/2010/09/02/guest-post-go-where-sex-gender-and-toilets/.

![Figure 5. Pictorial signage of public toilet used in the experiment of the study. Adapted from “Go where? Sex, gender, and toilet” [Blog post] by Marissa (Citation2010), September 2, Retrieved 15 October 2015, from https:/thesocietypages.org/socimages/2010/09/02/guest-post-go-where-sex-gender-and-toilets/.](/cms/asset/3de8b0f5-b290-4838-93ca-40cb07b90e37/oaah_a_1553325_f0005_oc.jpg)

In terms of the parameters of the study, the level of difficulty of identifying the toilet signage (parameter 1), the level of difficulty of differentiating the toilet cubicle based on gender difference (parameter 2), and the level of probability of errors to enter the toilet cubicle (parameter 3) were chosen as deemed appropriate for this study since they are the visual perceptual process of the subjects, as the viewers, when they see the signage. This is in accordance with Arnheim’s VP (Citation1974, p. 43) that seeing means grasping some outstanding characteristics of objects so that when people see toilet signage they try to understand the signage and try to distinguish male and female toilet cubicles to avoid making mistake in choosing and entering an appropriate toilet cubicle for them. Since the seen objects are the toilet signage where, as mentioned earlier, in most culture toilets are differentiated by gender (Ciochetto, Citation2003, p. 210), examining such VP of the signage is essential. Also, the level of embarrassment if they entered the inappropriate toilet cubicle (parameter 4) was considered appropriate as it relates to cultural dimensions where the cultural background of the subjects in this study can be categorised as collectivist cultures. In collectivist cultures if someone breaks the rules and norms of the society, he or she will feel embarrassed, based on a sense of collective obligation. Shame is social in nature and it is felt relies on whether the infringement has become known by others (Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov, Citation2010, pp. 109–110). Therefore, this aspect was taken into account as in a collectivist society if someone accidentally enter a toilet cubicle which is not for their gender, they will probably feel embarrassed.

With regard to the samples of pictorial signage, the signage were focused on the four types of male and female human figure representing the stylised forms of men and women. The samples were (1) Pictorial Signage A (PS A), the United States Department of Transportation (USDOT or DOT) pictogram, the signs which appear to have become standardised internationally in public places (Ciochetto, Citation2003, p. 215); (2) Pictorial Signage B (PS B) shows human in the outline image; (3) Pictorial Signage C (PS C) illustrates human torso (i.e. the central part of human bodies from which extend the neck and limbs) image; and (4) Pictorial Signage D (PS D) depicts human posture (i.e. particular position of the body) in using toilets. Those four pictorial signage were considered appropriate for this study since they represent human bodies in various forms (i.e. standard form, outline image, human torso, and human posture). Since public toilet signage are commonly depicted by human figures (Ciochetto, Citation2003, pp. 210–213), those types of human figure were the important samples to be used in this study.

In addition, VAS was appropriate to investigate VP of the subjects about the signage and visual perceptual differences among them because it can help us to measure the subjects’ perception about the signage which cannot be easily measured. As mentioned in some literature, for example, in Wewers and Lowe (Citation1990), such a scale is often used to measure attitude or subjective characteristics which cannot be easily measured, and, hence, it was applicable to examine the four questions in this study.

3.3. Procedure

The experiment consisted of two parts: (1) delivering information about the verbal informed consent, the pictorial signage of public toilet, and VAS and (2) informing how to fill the questionnaires out. The experiment was conducted for approximately 20 min in a classroom and used a projector to show the pictorial signage. After delivering information about the verbal informed consent, the pictorial signage, and the scale, the researchers distributed the questionnaire sheets, contained four pages, to each subject. Each page of the questionnaire provided the same information: detail information of the subjects (i.e. gender and age), the four questions (i.e. the level of difficulty of identifying the toilet signage, the level of difficulty of differentiating toilet cubicles based on gender difference, the level of probability of error to enter the toilet cubicle regarding gender difference, and the level of embarrassment if they entered the inappropriate toilet cubicle), and the scale (i.e. a horizontal line to mark subject responses, 100 mm in length, anchored by word descriptors at each end).

The researchers then showed the pictorial signage for 5 s for each signage and the subjects gave their responses to each signage on the questionnaire by marking the scale. The subjects gave the responses to the questions on the questionnaire at the same time guided by the researchers. Each page of the questionnaire was used to provide response to each pictorial signage so that the first page of the questionnaire sheet was to provide the subject responses to the four questions about PS A. Similarly, the second, the third, and fourth pages of the sheet were used by the subjects to respond to PS B, PS C, and PS D, respectively.

After the researcher collected the completed questionnaires, the subject responses to each question about each pictorial signage were calculated. These subjective ratings were in the form of scores which were then processed by descriptive statistics to get mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) where the questions were used as the parameters of the study (). To get significant differences of the subject responses on the four pictorial signage we conducted an analysis used inferential statistics which employed a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (). This method was aimed at identifying mean variation of certain pictorial signage to be compared to mean variation of the other pictorial signage. A post-hoc test was then used to identify the extent to which those differences occurred. Correlations between the parameters were also analysed by a regression analysis where this kind of correlation was used to see to what extent the parameters influenced each other. In addition, an unpaired t-test was conducted to analysed the different responses between the male and female groups.

Table 1. Mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) of subject responses to the toilet pictorial signage

Table 2. p-Value for all parameters

To analyse VP including perceptual difference among the subjects about the toilet pictorial signage, this study applied the theories of VP (Arnheim, Citation1974; Cantor, Citation2014) since these theories can help us to explain viewers’ ability to interpret their surrounding by processing information contained in visible light. This study also employed a VSS approach (Jewitt & Oyama, Citation2001; Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation1998) as it focuses on revealing potential meanings of images so that this approach can be used to explore meanings of the signage.

4. Results

shows that in general the subject responses to PS A with regard to parameters 1, 2, and 3 indicated the lowest scores. In other words, the subject responses to PS A showed the lowest average value in comparison to their responses to PS B, PS C, and PS D with regard to those parameters. It suggests that PS A was easier to understand, but the other signage (i.e. PS B, PS C, and PS D) were more difficult to interpret. However, in terms of parameter 4, the subject responses to PS A showed the highest average value compared to the answers to PS B, PS C, and PS D. These responses indicated that, in terms of PS A, the level of embarrassment of the subjects if they entered the toilet cubicle which was not for their gender was higher. On the contrary, that level was lower when associated with PS B, PS C, and PS D. In addition, illustrates the results of an ANOVA for all pictorial signage. It indicates that, regarding the four parameters, PS A was significant to the other PS (i.e. PS B, PS C, and PS D). In terms of parameters 1, 2, and 3, the subject responses showed the lowest score or strongly significant (p < 0.0001). However, in terms of parameter 4, the response was not strongly significant.

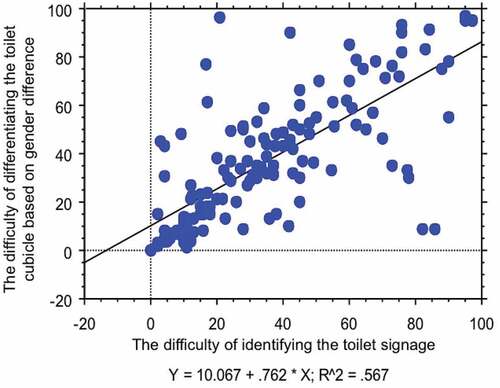

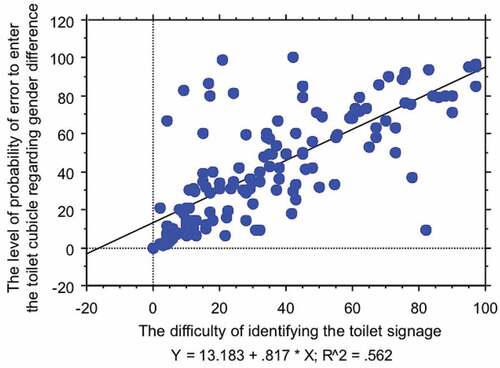

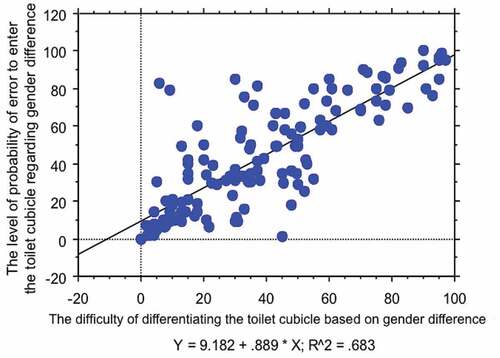

In addition to the above results, the subject responses indicated correlations between the parameters showing the positive and negative trends. Regarding the positive linear relation, it is indicated in the trend of the three relations between the subject responses to the parameters in the study, which are (1) between parameters 1 and 2, (2) between parameters 1 and 3, and (3) between parameters 2 and 3. Firstly, regarding the relation between parameters 1 and 2, it indicates that the more difficult the subjects identified the toilet signage, the more difficult they differentiated the male and female toilet cubicles (r2 = 0.567, p < 0.0001) (). Secondly, with regard to the relation between parameters 1 and 3 (), it shows that the harder the subjects identified the toilet signage, the higher the level of probability of error to enter the toilet cubicle regarding gender difference (r2 = 0.562, p < 0.0001). Thirdly, in the relation between parameters 2 and 3, it shows in that the more difficult the subjects to differentiate the toilet cubicle based on gender classification, the higher the probability of error to choose and enter the appropriate toilet cubicle (r2 = 0.683, p < 0.0001).

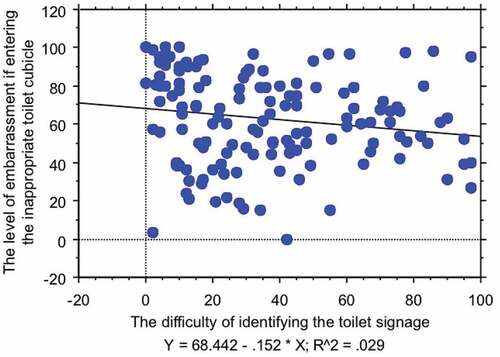

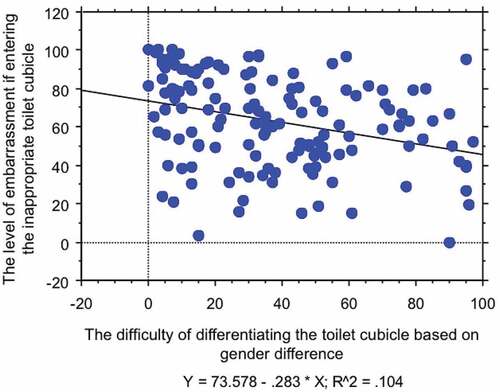

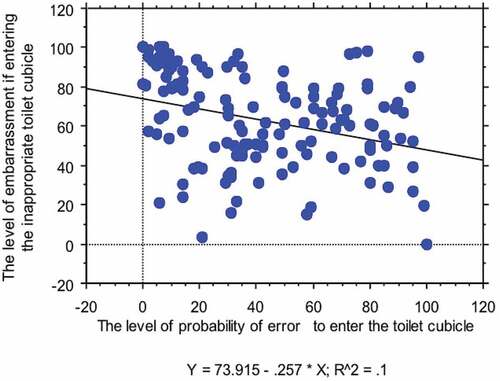

With regard to the negative trend, Figures 9–1 illustrate this relation in the three categories of subject responses to the parameters: (1) between parameters 1 and 4 (Figur 9), (2) between parameters 2 and 4 (), and (3) between parameters 3 and 4 (). First, no significant correlation between the subject responses to parameters 1 and 4 suggests that the more difficult the subjects to recognise the signage, the lower the level of embarrassment that might arise if they entered the toilet cubicle which was not for their gender (r2 = 0.029, p = 0.421). Second, the negative trend in the relation between the responses to parameters 2 and 4 indicates that the harder the subjects differentiated the pictures indicating the male and female toilet cubicles, the lower the level of embarrassment if they entered the inappropriate toilet cubicle based on gender classification (r2 = 0.104, p < 0.0001). Third, the inverse relationship of the responses to parameters 3 and 4 shows that the higher the level of probability of error to enter the toilet cubicle, the lower the level of embarrassment that might arise if the subjects entered the inappropriate toilet cubicle (r2 = 0.1, p < 0.0001).

In terms of gender difference, as mentioned earlier in the methodology section, the 36 subjects consisted of 15 males and 21 females. The results from an unpaired t-test, shown in , indicated that there was no significant difference between the two groups to the four parameters as the p-value was higher than 0.05. However, the average value (i.e. mean) for the female subjects was higher than that of the male subjects indicating that in this study the women tended to be more perceptive than the men in all parameters tested.

Table 3. Unpaired t-test for gender difference

5. Discussion

5.1. Visual perceptual process and meanings of the pictorial signage

The study demonstrated that the subjects’ interpretation of the four pictorial signage of public toilet indicated differences. PS A tended to be easier to understand than PS B, PS C, and PS D. In comparison to PS B, PS A was likely easy to understand (parameter 1) and had less likely to be misunderstood whether the images in this pictorial signage referred to the male or female toilet cubicle (parameter 2). In perceptual process of the signage, the subjects’ understanding about PS A was also influenced by their previous visual knowledge and experience which were socially conditioned during the lifetime of the subjects. This is in accordance with Arnhem’s (Citation1974, p. 48) explanation that VP is influenced by experience of the past so that they might be familiar with the signage depicted in PS A since such signage is commonly found in public places, where the male is depicted using a pair of trousers and the female is featured using a skirt. Also, this kind of signage, derived from the USDOT or DOT (Ciochetto, 2003, p. 215), is a generic form of male and female and seems to have become standardised internationally in public places.

In addition, visual appearance of PS A including its shape and colour tended to be easy to identify. The shape of the two human figures in this signage represents a symmetric visual object which, according to Arnheim (Citation1974, p. 20), in VP balance is important since a balanced composition depicts shapes in such a way that no change. The balanced composition in this signage was likely easy to recognise by the subjects indicating that they could determine its meaning easily. Since this signage was easier to identify, the subjects would enter the appropriate toilet cubicle (parameter 3).

In the perceptual process, the ease of interpreting PS A was also supported by the colour contrast between the images of male and female and their background which create coloured regions with boundaries determined by white for the male and female images and blue for the background. In visual representation process Cantor (Citation2014, p. 3) called it segmentation where the visual scene is recognised as segmented into coloured regions determined by colour contrast. The colour contrast between the images of male and female and their background in PS A forms figuration (Cantor, Citation2014, p. 3) so that in a visual scene the subjects could see the images as a unitary object with a clear visual organisation (Cantor, Citation2014, p. 3). This clear organisation is indicated by a similarity of colour to represent the male and female images in white with the blue background.

In terms of colour contrast of the pictorial signage, the perceptual process of the four signage was formed when the subjects viewed two areas of different brightness at the same time (Arnheim, Citation1974, p. 362). In PS A the white over the blue, in PS B the white on the black, in PS C the blue over the white, and in PS D the yellow on the brown. This perceptual process could then make the subjects understand the shapes of the human figure and the whole composition of the signage determined by the boundaries of the images of human in the signage. This perceptual shape was the outcome of an interplay between the images of human in the signage, the medium of light acted as the transmitter of information, and the condition prevailing in the nervous system of the subjects (Arnheim, Citation1974, p. 47). The boundaries determined the shapes of human figure derived from the capacity of the subject’ eyes to distinguish between areas of different brightness and colour.

Regarding the VP of PS B, PS C, and PS D, this study showed that these three pictorial signage relatively had a similar level of difficulty to identify. In perceptual experience the outline image in PS B created a structural skeleton of the signage. Skeleton of pictorial elements help viewers to determine meaning of visual objects (Arnheim, Citation1974, p. 15) so that the skeleton in PS B could assist the subjects to create the shapes of the images of male and female in their mind which could then help them to define meaning of the images. However, the subjects might need more time to transform the lines into the shapes of male and female in their perceptual process. This time lag was likely the reason which caused PS B was more difficult to understand than PS A. In addition, PS C, the image of human torso, and PS D, the image of human posture in using a toilet, depict unbalanced visual composition. An unbalanced visual composition looks temporary and is likely to change shape (Arnheim, Citation1974, p. 20) so that it seems like these two pictorial signage were difficult to understand within a short space of time. This kind of visual composition present an ambiguous pattern, an Arnheim’s term (Arnheim, Citation1974, p. 20), which can cause difficulties in deciding on which of the possible visual composition is meant. It could then make the subjects needed more time in the perceptual process.

The subjects’ understanding about the four pictorial signage also relates to the representational, interactive, and compositional meanings. Regarding representational meaning, the images of a man and a woman in each signage, which are depicted differently, represent conceptual structure (Jewitt & Oyama, Citation2001, pp. 143–145; Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation1998, pp. 78–118) as these images are placed symmetrically and supported by the same colour and size, showing that they illustrate a stable essence and belong to a same class which is gender classification. In PS A this meaning relates to the previous explanation in this paper that commonly an image of a man is represented by people wearing trousers, whereas a woman is depicted by an image of people using skirts. In PS B, the depiction of human in the outline image, the image of female (i.e. the left image) is differentiated from the image of male (i.e. the right image) by the image of human wearing a skirt. As mentioned earlier, our knowledge about fashion is socially shaped in our society. Skirts generally represent female clothes, whereas trousers indicate male clothes (Craik, Citation2009, p. 140). This general perception of stoicism (i.e. a school of philosophy which taught that everything was rooted in nature) is focused on an idea of fashion as emphasising a sense of a time when “men are men and women are women”. According to this notion, men look like men in their trousers and women look like women with their skirts (Edwards, Citation2007, p. 192). In PS C the images of male and female are differentiated by the shapes of human torso. In this signage the left image represents male torso, whereas the image on the right indicates female torso. This difference is indicated by a large torso in male body with a low waistline as well as high and broad shoulders, and a small torso in female body with a high waistline as well as low and narrow shoulders (Dobkin, Citation2010, pp. 87–89). Different from the other pictorial signage in this study, PS D does not only represent conceptual structures (i.e. classification structures), but also illustrates narrative structures (Jewitt & Oyama, Citation2001, pp. 141–143; Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation1998, pp. 43–47) as the images of a man on the left and a woman on the right illustrates “doing something”, which is the activity of using a toilet. In this representation these two images including their shapes indicate vectors. This vector is imaginary depicted by imaginary lines connecting the images of human to urination/defecation devices, even though the devices are absent in the signage. In this relation the man and the woman are the “actor”, the element from which the vector emanates, whereas the urination/defecation devices is the “goal”, the element at which the vector is directed.

In terms of interactive meaning, this meaning is produced by the relation between the subjects and the signage. The images of a man and a woman in each signage in this interaction can be likened to something that “asked” or “invited” the subjects to look at them. In other words, these two images want to “inform” the subjects in this study that they are the toilet signage. Although it is an imaginary relation, the signage creates a contact between themselves and the subjects, which is relevant to the concept of contact (Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation1998, pp. 122–129) within interactive meaning. The colours and shapes of the human images, in particular, the contrast colours between the images of human and their background, are considered as important visual elements which attract the subjects to look at the signage which can then determine this relation.

Regarding compositional meaning, visual elements of each signage comprise the whole composition of each signage and produce the meaning of composition about the public toilet signage. The colours and shapes of human in each signage composition are more salient, supported by the colour contrast between the human images and their background. The images of male and female depicted in white on blue in PS A might indicate saliency of the two images. Also, the images of human in white over the black (PS B), in blue with the white background (PS C), and in yellow over the brown (PS D) indicate saliency of the images of human. This is in accordance with the concept of salience (Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation1998, pp. 112–114) within compositional meaning where the signage are made more eye-catching than the other visual elements in the composition of the signage. Although in VP the perceptual process begins with the grasping outstanding structural features (Arnheim, Citation1974, p. 44), the two images appear as a complete and show an integrated pattern consisting of colour and shape. In addition, in each signage composition some visual cues indicate a connection between the two images which then indicate frames. The visual cues are the similarity of the background colour (i.e. blue, black, white, and brown) and the size and colour of the two images in each signage (i.e. white, blue, and yellow). This connection is therefore related to a framing concept (Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation1998, pp. 214–218) of this signage.

In the four signage, the whole meaning of the signage (i.e. representational, interactive, and compositional) are related to each other illustrate the public toilet signage. This whole meaning is shaped by social context since, as mentioned previously, the subjects in their society might recognise that this signage was usually used to indicate a public toilet. In other words, their interpretation was based on their visual knowledge and experience. More specifically, they might understand that two visual images which are put symmetrically indicate a same category, for example, a group of people in a composition. They might also understand that a visual composition might attract them to look at due to, for example, its colour, shape, or size. Also, they recognised that different colours in a visual composition might indicate that such elements are more important than the other elements within their composition. It is therefore their VP was influenced by their experience of the past, as mentioned earlier.

5.2. Relationship between the parameters of the study

The relation between parameters 1 and 2 showed a significant relation indicating causality. If the subjects had difficulty to identify the toilet signage (parameter 1), they also had difficulty to identify the toilet cubicle based on gender difference (parameter 2). This causality is important to take into account since toilet signage is universally indicated by the image of human figure, men and women (Ciochetto, Citation2003, pp. 208, 210). This causality also relates to visual organisation in the perception process where understanding a unitary figure is defined by the perception of relations between elements in a visual scene (Arnheim, Citation1974, p. 63; Cantor, Citation2014, p. 4). If the subjects were familiar with the images of male and female as the toilet signage, for example, as shown in PS A, it is likely they recognised the similarity of visual elements such as colour of the images of male and female (white) and their background (blue) as a unitary figure. This perception is also supported by the subjects’ visual knowledge and experience about the images which were obtained in their lifetime. However, the asymmetrical shapes of PS B (the left image), PS C, and PS D are likely more difficult to understand than the symmetrical shape of PS A (see ). The forms of skeleton (PS B), human torso (PS C), and human posture in using toilet (PS D) are possible to cause these forms become more difficult to interpret than the common signage shown in PS A. So, the similarity of colour of the three pictorial signage might not be sufficient to understand the signage easily due to their unbalanced shape.

The difficulty of identifying the toilet signage (parameters 1 and 2) relates to the level of probability of error to choose and enter the toilet cubicle based on gender difference (parameter 3) which also indicates causality. If the subjects had difficulty to make meaning the signage, there would be an error in choosing and entering the toilet cubicle with regard to gender classification. This indicates that they would enter the toilet cubicle which was not for their gender. The unbalanced images in the pictorial signage, as described in the previous paragraph, and the subjects’ unfamiliarity with the shapes of the images in the signage have the potential to cause the misinterpretation.

The relation between the three parameters (1, 2, and 3) and parameter 4 indicates a nonsignificant relation where if the subjects had difficulty to understand the signage they were likely to have less level of embarrassment. Similarly, if they entered the inappropriate toilet cubicle, they had low level of embarrassment. On the contrary, the level of embarrassment was higher if the signage were easier to understand and the probability of error to enter the appropriate toilet cubicle was lower. Since the subjects were considered from a collectivist culture (see Section 3) this condition is likely related to the fact that in such a culture people usually tend to avoid direct conflict if someone makes mistakes (O'Rourke & Collins, Citation2009, p. 30). They believe that the conflict will cause shame for others which can then disturb the harmony of the group. Also, the concept of “face” in the collectivist culture is important so that they tend to avoid making other members of the group to “loose” their face which, according to Hofstede et al. (Citation2010, p. 110), relates to the sense of being humiliated. “Loosing face” might occur if someone in the group fails to meet fundamental obligations in their social life. Although the subjects might make a mistake to interpret the pictures in the toilet signage and were possible to have a higher degree of error to choose the toilet cubicle caused by misinterpreting the signage, other members of their group would usually keep a proper relationship with their social environment.

In terms of the visual perceptual difference between the male and female subjects, as illustrated in , there was no significant difference between these two groups in interpreting the pictorial signage. This is most likely due to the homogeneity of the subjects who were the students of the same course at the same institution. Taking into account their educational background is important as it can cause their relatively similar level of visual knowledge and experience in understanding the signage although their level of understanding might be slightly different for each of them since this is also influenced by their previous experience both formal and informal (Trisnawati, Citation2012, p. 286). In addition, the homogeneity is indicated by their cultural similarity since 80.6% of the total number of the subjects are from cities in Java Island and the rest, 19.4%, are from cities in Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Sulawesi islands.Footnote1

Although there was no significant difference between the male and female subjects to the four parameters, the average value of the female subjects was higher than that of the male subjects (see ). This was due to visual perceptual differences between these two groups. According to Hultén (Citation2015, p. 186), previous research suggests that there are differences between men and women in relation to VP and visual preferences from variety of aspects. Women are likely to be more sensitive to colour than men so that women might outperform men in visual tasks in terms of colour perception. Women also tend to have abilities of perceptual speed, which is the ability to quickly and accurately compare pictures, and can hold an afterimage of a briefly bit longer (Kim & Johnson, Citation2010, pp. 492–493). Since colour is an important element in the composition of the pictorial signage which creates the shape of the human figures, the subjects’ ability to detect colour was likely connected to their ability to notice the shapes. The samples of pictorial signage in this study are depicted in several colours which are white and blue (PS A and PS C), white and black (PS B), and yellow and brown (PS D). The average value of the female subject responses then implies that they were much better detecting the pictorial signage including identifying the male and female figures in the signage by the colours and shapes of the figure and the whole composition of the signage.

In addition, in terms of the subject responses to parameter 4, p-value of this parameter was 0.0975 which is close to 0.05 where p < 0.05 indicates significant level (see ). It might indicate that p-value of that parameter is close to significant. There might be possibilities to be significant for this value if there are changes on the data, for example, the number of male and female subjects.

6. Conclusions and implications

This study underlines the importance of examining VP of derivative pictorial signage of public toilet depicted as human figures and used a VAS which measured the attitude of the subjects about the signage in combination with the use of the theories of VP and VSS. Although VAS is still relatively rarely used in visual communication research, the scale was useful to measure the attitude of the subjects in this study as the level of subjects’ understanding about the signage cannot be easily measured directly. In more details this utility is shown in the results about the varied subject responses according to the four parameters of the study. In addition, the integrated approach comprising the theories of VP and VSS can help us to explain not only how the subjects took information or stimuli from the signage and developed meanings including reaction to the signage, but also how they communicated by using the signage in particular social settings where their understanding about the modes of communication were obtained in their everyday instantiation.

In general, the limitation of this study might be due to the type of the subjects as they were a group of homogenous university students. Apart from the limitation, the strengths of the study are it has shown the use of VAS to examine visual perceptual process including visual perceptual differences among the subjects of the derivative pictorial signage, while this scale is rarely used in visual communication research. Also, the combination of the theories of VP and VSS are useful to examine VP of the signage and to reveal potential meanings of the signage.

This study can then be a model for further VP studies, especially studies on signage systems in public places. The results of the investigation can contribute to developing pictorial signage of public toilets or other public facilities. Also, the combination of VAS and the theories of VP and VSS is potential to be applied to investigating other pictorial signage. In addition, the study is closely related to visual communication and media studies in terms of VP of pictorial signage of public facilities, and, in general, to the field of arts and humanities. In addition, indirectly, this study will relate to visual culture and design studies in a way that designing signage of public facilities needs to consider viewers’ way of interpretation of the signage to minimise misinterpretation, moreover minimising incorrect usage of the public facilities, for example, by considering the standard symbols or common logos.

Further research may include other types of pictorial signage, other methods of data collection, and other theories to be combined for the investigation. Methods of data collection in similar studies can combine questionnaires with other methods, for example, focus groups with viewers of signage, interviews with visual communication designers, or observations of viewer response when they see and make meaning the signage. Considering a cross-cultural context might also be useful for further studies as the study in this paper is specific to a certain culture. Also, viewers with culturally diverse backgrounds might show the dynamic nature of VP as well as their perceptual difference.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Suranti Trisnawati

Suranti Trisnawati studied Communication and Media Studies at University of Southern Queensland, Australia, and Discourse Studies at University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands. She is currently a lecturer at Institut Teknologi Bandung, Indonesia, and used to teach at Keio University, Japan, and Taylor’s University, Malaysia. Her research interests include science communication, health communication, and visual communication. In general, her research synthesises communication, culture, and language.

Andar Bagus Sriwarno

Andar Bagus Sriwarno is a graduate of Chiba University, Japan and Institut Teknologi Bandung, Indonesia where he studied industrial design and ergonomics. He is currently lecturing at the Faculty of Art and Design, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Indonesia. His research covers a wide range of topics in product design and ergonomics.

Notes

1. The islands of Java, Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Papua are the five largest islands in Indonesia.

References

- Afacan, Y., & Gurel, M. O. (2015). Public toilets: An exploratory study on the demands, needs and expectations in Turkey. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 42, 242–262. doi:10.1068/b130020p

- Ahissar, M., & Hochstein, S. (2004). The reverse hierarchy theory of visual perceptual learning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(10), 457–467. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2004.08.011

- Alant, E., Kolatsis, A., & Lilienfeld, M. (2010). The effect of sequential exposure of color conditions on time and accuracy of graphic symbol location. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 26(1), 41–47. doi:10.3109/07434610903585422

- Arnheim, R. (1974). Art and visual perception: A psychology of the creative eye. (the new version). Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Baker, C. I., Olson, C. R., & Behrmann, M. (2004). Role of attention and perceptual grouping in visual statistical learning. Psychological Science, 15(7), 460–466. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00702.x

- Bas, B., & Örs, E. (2015). A study on visual reading skills of first grade students at primary school. Journal of Theory and Practice in Education, 11(1), 225–244.

- Bloomberg, K., Karlan, G. R., & Lloyd, L. L. (1990). The comparative translucency of initial lexical items represented in five graphic symbol systems and sets. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 33, 717–725. doi:10.1044/jshr.3304.717

- Canel, N., & Yukay Yüksel, M. (2015). Evaluating the development of the visual perception levels of 5–6 year-old children in terms of school maturity and “draw a person” technique. Journal Plus Education, 12(1), 61–78.

- Cantor, R. M. (2014). A semiotic model of visual perception. Semiotica, (2014(200), 1–20. doi:10.1515/sem-2014-0008

- Carrillo, E., Fiszman, S., Lähteenmäki, L., & Varela, P. (2014). Consumers’ perception of symbols and health claims as health-related label messages: A cross-cultural study. Food Research International, 62, 653–661. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2014.04.028

- Chu, S., & Martinson, B. (2003). Cross-cultural comparison of the perception of symbols. Journal of Visual Literacy, 23(1), 69–80. doi:10.1080/23796529.2003.11674592

- Ciochetto, L. (2003). Toilet signage as effective communication. Visible Language, 37(2), 208–221.

- O'Rourke, J.S., & Collins, S.D. (2009). Module 3: Managing conflict and workplace relationship (Managerial communication) (2nd ed.). Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning.

- Craik, J. (2009). Fashion: The key concepts. Oxford: Berg.

- Dobkin, A. (2010). Principles of figure drawing. Cleveland: The World Publishing Company.

- Dormann, C. (1994). Self-explaining icons. Intelligent Tutoring Media, 5(2), 81–85. doi:10.1080/14626269409408346

- Edwards, T. (2007). Express yourself: The politics of dressing up. In M. Barnard (Ed.), Fashion theory: A reader (pp. 191–196). London: Routledge.

- Faulkner, X. (2000). Usability engineering. Houndmills: Macmillan Press.

- Hartley, J. (2002). Communication, cultural and media studies: The key concepts (3rd ed.). London: Routledge.

- Hideyuki, T., Shunji, M., & Takashi, Y. (1978). Textural features corresponding to visual perception. IEEE Transactions on Systems Man and Cybernetics, 8(6), 460–473. doi:10.1109/TSMC.1978.4309999

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organization: Software of the mind (3rd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Hultén, B. (2015). Sensory marketing: Theoretical and empirical grounds. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Ingrey, J. C. (2012). The public school washroom as analytic space for troubling gender: Investigating the spatiality of gender through students’ self-knowledge. Gender and Education, 24(7), 799–817. doi:10.1080/09540253.2012.721537

- Jewitt, C., & Oyama, R. (2001). Visual meaning: A social semiotic approach. In T. van Leeuwen & C. Jewitt (Eds.), Handbook of visual analysis (pp. 134–156). London: Sage Publications.

- Johannessen, C. M. (2013). A corpus-based approach to Danish toilet signs. RASK – International Journal of Language and Communication, 39, 149–183.

- Kim, H. J., & Johnson, S. P. (2010). Individual differences in perceptions. In E. B. Goldstein (Ed.), Encyclopedia of perception (Vol. 1, pp. 492–501). Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Kress, G., & van Leeuwen, T. (1998). Reading images: A grammar of visual design. (Original work published 1996). London: Routledge.

- Marissa. (2010, September 2), Go where? Sex, gender, and toilet [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2010/09/02/guest-post-go-where-sex-gender-and-toilets/.

- Motel, L. (2016). Sex symbols: A pilot study examining the effects of a content analysis of gendered visual imagery in cross cultural road signs. Journal of Intercultural Communication, 41.

- Motel, L., & Peck, B. (2018). SexIER symbols: Examining the effects of a content analysis of gendered visual imagery in cross cultural road signs. Journal of Intercultural Communication, 47.

- Ng, A. W. Y., Siu, K. W. M., & Chan, C. C. H. (2012). The effects of user factors and symbol referents on public symbol design using the stereotype production method. Applied Ergonomics, 43, 230–238. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2011.05.007

- Ostrofsky, J., Kozbelt, A., & Kurylo, D. D. (2013). Perceptual grouping in artists and non-artists: A psychophysical comparison. Empirical Studies on the Arts, 31(2), 131–143. doi:10.2190/EM.31.2.b

- Romera, M. (2015). The transmission of gender stereotypes in the discourse of public educational spaces. Discourse & Society, 26(2), 205–229. doi:10.1177/0957926514556203

- Sarantakos, S. (2004). Social research (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Seok-Seo, H., Arshamian, A., Schemmer, K., Scheer, I., Sander, T., Ritter, G., & Hummel, T. (2010). Cross-modal integration between odors and abstract symbols. Neuroscience Letters, 478(3), 175–178. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2010.05.011

- Shen, S. T., Woolley, M., & Prior, S. (2006). Towards culture-centered design. Interacting with Computers, 18(4), 820–852. doi:10.1016/j.intcom.2005.11

- Shomstein, S., & Johnson, J. (2013). Shaping attention with reward effects of reward on space-and object-based selection. Psychological Science, 24(12), 2369–2378. doi:10.1177/0956797613490743

- Sutherland, L. (2016). Inclusive symbols for people living with dementia: Feasibility research. Edinburgh: StudioLR.

- Trisnawati, S. (2012). An integrated communications approach to user multimedia interactions. Saarbrücken: LAP Lambert Academic Publishing.

- Van Leeuwen, T. (2005). Introducing social semiotics. London: Routledge.

- Wewers, M. E., & Lowe, N. K. (1990). A critical review of visual analogue scale in the measurement of clinical phenomena. Research in Nursing and Health, 13, 227–238.

- Wright, P., Lickorish, A., & Hull, A. (1990). The importance of iterative procedures in the design of location maps for the built environment. Information Design Journal, 6(1), 67–78. doi:10.1075/idj.6.1.04wri