Abstract

The Government of South Africa, through Act 200 of 1993 Post-apartheid Constitution, established the Language-in-Education Policy, (LIEP), which has various provisions concerning the eleven languages recognized as official indigenous languages in the country and how these languages should be used in South African schools. This policy stipulates that these indigenous languages must be used both as a medium of instruction and as a subject. A gap between the intent of this policy and its implementation has already been established by many scholars in South Africa. This study is therefore aimed at critically answering the following questions which necessitated the study: In the face of the gap between LIEP intent and implementation, what needs to be done? Are there strategies to be employed for the implementation and actualization of this Education Policy? Using analytical method, this study reviewed related literatures, which have established media roles in the implementation of policies with the aim of prescribing the strategies which can help the media in South Africa in performing this function. The study concluded that with the strategies outlined in this policy for the revitalization of indigenous languages, the media in South Africa need to set the right agenda, which may snowball into the actualization of implementing the language-in-education policy in all schools in the country. It is recommended, among others, that Government and Non-Governmental Organizations in South Africa partner with the media in closing the gap between the intent and implementation of LIEP using the strategies proposed in this study.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This paper studied the Language-in-Education Policy (LIEP), formulated at the end of apartheid regime in South Africa. The policy stipulates that indigenous languages are to be used in South African schools as medium of instructions and as subjects. This paper reaffirmed earlier studies, which found a gap between the policy intent and implementation or practice. Since this is the reality on ground, this paper therefore set out to find the roles, which the media in South Africa can perform in order to ensure the policy intent is actualized. The study employed analytical discussion method in which related literatures were used to support the positions taken on issues discussed. This paper concludes that public awareness regarding implementation of LIEP can be handled by the South African media through various media tools like press releases, news articles, features, interpretive stories, context-setting stories, editorials, columns and even cartoons.

1. Introduction

South Africa’s Post-apartheid constitution Act No. 200 of 1993, recognizes language as a fundamental human right, and adopted the use of many indigenous languages as a national policy. With this position, the country has moved away from its former orientation that language is a national problem facing the country (Chick, Citation1996). In this constitution, it is clearly stated that:

“no person shall be unfairly discriminated against, directly or indirectly, on the grounds of language, (section, 8);

“that each person has the right to instruction in the language of his or her choice where this is reasonably practicable, (section, 32);

“that each person wherever practicable, shall have the right to insist that the state should communicate with him or her at national level in the official language (section,3), (South Africa, Citation1993).

The board responsible for the promotion of the use of these eleven languages is the Pan South African Language Board. It is backed by the constitution and was established in March 1996. This board ensures that these official languages are given equal attention and that none has undue leverage over another. It also provides translation services when necessary (Chick, Citation1996).

South Africa, as a nation, is multilingual just like other African nations like Nigeria, Ghana, Zimbabwe and the rest. The South Africa’s constitution of 1996, officially recognized eleven languages as the official languages. As a matter of emphasis, it is worthy to mention that twenty-five indigenous languages were said to have been spoken in South Africa in 1996, (Kamwangamalu, Citation2014). These notwithstanding, only eleven out of this number were chosen as official languages. These eleven languages have the following number of speakers as published in 2008 by South African Statistics Department:

Zulu 23%

Xhosa 16%

Afrikaans 13.5%

Sepedi 9.1%

Setswana 8%

Sesotho 7.6%

Xitsonga 4.5%

Swati 2.5%

Tshivenda 2.4%

Ndabele 2%

(Statistics South Africa, 2004, p. 8).

It is worthy of note to state that indigenous languages in the country have continued to increase tremendously while non-indigenous language like English remain the most dominant one still in use in official circles, (Kamwangamalu, Citation2014). The dominance of this non-indigenous language could be attributed to apartheid but post-apartheid policies, no doubt have strengthened the country’s smaller indigenous languages as well. This is the reason for the language – in-education policy commonly known as LIEP. This policy was formulated in order to give voices to indigenous languages already endangered. It is aimed at revitalizing them and preventing them from going extinct. But unfortunately there seems to be gap between the LIEP intent and implementation. This is the essence of this study. It is aimed at critically analysing the policy with a view to prescribing strategies which will help its implementation in South African schools. This study recognizes the media as the fourth estate of the realm and therefore is of the opinion that the media can successfully bring about the implementation of this policy. Since the study is highly prescriptive in nature, analytical discussion method was employed in looking at mind- bugging questions that necessitated the study. The first question being: in the face of the gap between LIEP intent and implementation, what needs to be done? Secondly, in what ways can the South African media help in the implementation of the LIEP policy? Thirdly, are there strategies to be employed by the media in order to achieve this objective? The analytical approach employed in the study allowed the researchers to draw inferences from previous studies and make assumptions based on their results. For this reason, this approach is deemed appropriate for the study.

2. Have the media been useful in implementing language policies?

This question is critical to this study based on the fact that this study is analytical in nature and therefore will draw inferences from already established studies in order to establish its own position and make valid recommendations. There are available literatures to show that the mass media have been used effectively in carrying out enlightenment campaigns that brought the formulation and implementation of language policies in some countries. A study undertaken by Tadhg O Hlfearnain in 2010 clearly showed how Irish minority language broadcasters used the airwaves in forcing the formulation and implementation of language policy that now allows programming in minority languages in the country. (O’Hlfearnain, Citation2010). In a study titled, “Language Policy and the Broadcast Media”, O’Laoire (Citation2010) underscores how the broadcast media can impact on language planning and language use in a nation. In a 2008 study, Mairead Moriarty found that the media have effects on language policies and practices in Ireland and therefore can be useful in language revitalization and normalization. Earlier studies like Cormack (Citation2003), Stuart-Smith (Citation2006) and Trudgill (Citation1986, Citation2006)) also show how language policies were formulated and implemented through enlightenment campaigns disseminated through various media platforms in some countries. It is on these available literatures that this study hinges its’ underpin.

3. Analysis of language – in-education policy

The Language-in-Education Policy has two major provisions guiding how language is used in South African schools. This is contained in 3(4) (m) of the South African National Education Policy Act of 1996. It is observed that the policy describes language as a subject of study; and also as a medium of instruction. Another important point to note concerning this policy is the fact that the learner has the right to choose a language through which teaching must take place. This implies that the learner has the right to select a language through which he or she is to be taught in school from the eleven official languages, (Department of Education, Citation2002, Citation2003). However, this right is to be exercised based on the number of students or pupils selecting a given indigenous language and availability of material and human resources needed in order to make this possible. In the Act, language as a subject to be taught in South African schools requires the following:

All learners shall choose at least one approved language as a subject in Grade 1 and 2.

All learners shall choose at least two approved languages, of which at least one shall be an official language, from Grade 3 onwards.

All language subjects shall receive equitable time and resource allocation.

The following promotion requirements apply to language subjects:

In Grade 1 to Grade 4, promotion is based on performance in one languages and mathematics

From Grade 5 onwards, one language must be passed

From Grades 10 to 12, two languages must be passed, one at first languages level and the other one at least second language level. At least one of these languages must be an official language.

Subject to national norms and standards, as determined by the Minister of Education, the level of achievement for promotion shall be determined by the provincial education departments.

This education policy was developed with a view to overcoming past education policies which marginalized and discriminated against black South Africans, especially the Banyu Education Act (Heugh, Citation2012). The 1952 Bantu Education Act enforced apartheid in the education system through the segregation of educational opportunities and infrastructures by racial structures. During this period, there was a clear difference in the quality and standards of schools meant for Whites and those meant for Blacks. The quality of teachers and instructions in schools where Black children were taught was low compared to what was obtainable in schools for White children. This scenario continued until 1979 when the efforts to repeal the Act were successful. No wonder then, Kamwangamalu (Citation2004), notes that this new LIEP in South Africa was aimed at uplifting the status of the indigenous languages of disadvantaged people of South Africa. It obligates the Government to recognize and upgrade the status of the indigenous languages by encouraging their use in schools. It does this by encouraging and promoting multilingualism to strengthen the eleven official languages. The policy also aims to close the gap between language used in schools and language spoken at homes. But the question is: Is this policy in practice in South African schools?

4. LIEP and practice: any match or mismatch?

Most African Nations are plagued by lack of implementation of well-formulated policies which are often applauded when seen on Government blue-prints. The LIEP in South Africa is just one out of the numerous others. Some languages are already going extinct. The sign language and San/Nama group are typical examples. The LIEP was developed to bridge the gap but its implementation seems very problematic and far-fetched (Klu&Quan-Baffour, Citation2006).

Many processes are involved in the making of public policies. A lot of politics and intrigues are encountered in the process as well. This is why policies do not stop with just the enacting of laws or supporting them with Acts or Constitutional provisions. Policies go beyond this. The three arms of Government; Executive, Judiciary and Legislature are involved. The fourth arm, being the media is also needed for the policy to work. All these arms of Government work together to make public policies and decisions become a reality in any nation.

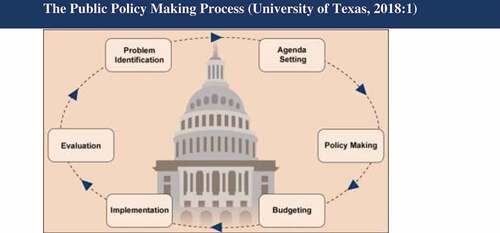

Public policy can be described as a long or short term chain of actions which government undertakes in order to solve problems or make life better for the citizens of a nation. These policies are formulated based on law, but people other than legislators make them a reality. This is often the reason why any person or group who violates such policies face penalty prescribed by the law for such violation. The process of formulating a policy is complex as outlined in this model developed by University of Texas:

These six stages complement each other, with mini-stages in-between. It is a process that goes round and round. It never comes to an end. It begins with identifying the problem, setting the agenda, coming up with a policy, making adequate budget for implementation, implementing the policy and evaluating the actions taken so far. The evaluation provides reasons for the success or failure of the entire programme and this necessitates new chains of actions again and again. The processes are explained as follows:

4.1. Problem identification as the first step

A problem can be identified in many ways. It can start with an individual or group expressing an opinion about how dissatisfied or unhappy they are with an existing policy or government institution. It can equally be triggered off when an arm of government raises an alarm over an issue affecting the citizens. When this happens, the problem is often made more popular by individuals, mass media and non-governmental organizations. The media are involved in this first stage. In fact, in all the stages, the nation’s media are needed in the policy making.

4.2. Setting the agenda

Although the media comes first when it comes to agenda setting, there are other key actors in every polity who set agenda for policy formulation. It is at this stage that every alternative is examined and defined. Once it becomes a national issue, then the issue becomes an item on the agenda list of the executive, legislature and judiciary. At this juncture, it is still an idea but once it makes it through these stages, it is as good as being adopted as a policy.

4.3. Making the policy

Policies normally emanate from problems addressed at various agendas of the arms of government. This is because they are formulated to solve such national issues. They will undergo various political scrutinies before being recognized through the bureaucratic machinery set in place for such. Even when no action or no decision is taken or when the proposal is defeated through superior arguments, it is regarded as a policy itself.

4.4. Mapping out of budget

It is the duty of government to decide on how much money is to be spent on a particular policy. This is done through the process of budgetary appropriations. But for monetary budgets to be made, the policy must have been adopted or authorized.

4.5. Implementing the policy

It is the responsibility of agencies under the executive arm of government to implement policies. This could be in the form of adoption of regulations guiding how things are to be done. It could equally be in the form of making goods and services available to certain people who need it. Mass education or enlightenment can be carried out through the media as well in order to achieve this aim.

4.6. Evaluating the policy impact

Evaluating the impact of a policy is not the job of government agencies alone. Evaluators can include the media and people in the academia. Many actors are involved at this stage. This is done to ascertain whether the policy is effective in doing what it was aimed for. Evaluators consider the cost implications of the policy vis-à-vis its intended benefits. The negative and unintended effects of the policy are also evaluated. Government agencies no doubt mostly use their various offices for this purpose. A good evaluation frequently triggers off the identification of new issues and a better approach of solving them through another round of agenda setting and making of policy (University of Texas, 2018, p. 1).

The functions which the media can perform in the making of any public policy can never be under estimated. Right from the onset, the media must be involved. The Language-in-Education Policy is at the evaluation stage. At this stage, the academia, the media and other interest groups seem to have agreed that there is a gap between the formulation of this policy and its full implementation. Most African Nations are good in formulating policies, but the implementation remains a herculean task. The current LIEP was well-formulated. The question is: Is this policy guiding instructions in South African schools? For instance, the Language-in-Education Policy, (LIEP, Government of South Africa, Citation1997), stipulates that “the right to choose the language of learning and teaching is vested in the individual”, though the choice must be made from the eleven official languages. The policy further asserts:

“the learner must choose the language of learning upon application for admission to a particular school. Where a school uses the language chosen by a learner and where there is a place available in the relevant grade, the school must admit the learner,(p. 3).

A cursory look at this policy statement reveals an extensive indigenous-based learning; however, it allows teachers and parents to choose English language and Afrikaans as the languages of instruction in most South African schools. This is despite the fact that there are other indigenous languages spoken in homes where these learners come from.

In Black schools, L1 or mother tongue is used in Grades 1–3 with English introduced as the additional language in Grade 1 or 2. In Grade 4, learners move to English language as the language of teaching and learning for the entire primary curriculum, (Manyike, Citation2013). This implies that for the majority of students with African home languages, the transition to English language is a switch to a foreign-language-medium instruction. For English-Speaking learners, it is not the case. They are allowed to use their mother tongue throughout their education (Heugh, 2011).

Department of Basic Education’s Annual Surveys of schools from 2007 to 2011, revealed that 79.8 per cent of children were in schools without change in language of instruction policy. Only 5.9 per cent of children were in schools that switched from English to an Indigenous language using the study period, (Taylor & Coetzee, Citation2013). This finding, although few years back, is still prevalent in most South African schools. Nothing seems to have changed. There is still post-apartheid hesitation to use indigenous languages in school instructions. Alexander (Citation2003, p. 16), is of the opinion that the preference for English is rooted in the” simplistic and inarticulate belief that if only all the people of the country could rapidly acquire knowledge of the English language, all communication problems and inter-group tensions will disappear”. Whether the knowledge of English will help solve communication and inter-group tension issues, is a case for another research work.

There is therefore a mismatch or gap between the policy intent and its implementation and actualization. As it has been asserted by Motala in UNICEF (Citation2016, p. 6), this gap has a damaging impact on learners. This is because, “inadequate mastery of the language of learning and teaching is a major factor in the abysmally low levels of learner achievement. Yet, many parents prefer to have their children taught in the second language of English by teachers who are themselves second language speakers of English.

5. Creating awareness about the strategies for indigenous language use in South African school setting: the role of the media

Since it has been established that there is a gap between the LIEP intent and its implementation and or actualization, this paper now explains the strategies with which the intent of LIEP could be implemented and actualized. These strategies, with the help of media organizations of most countries have worked in the revitalization of indigenous languages in school settings. With the help of the media in South Africa, these strategies hopefully will equally be effective in achieving the objectives of the LIEP.

Indigenous languages help preserve and protect indigenous people, their cultures and their identities. It helps in the formation of social belongingness between and among indigenous communities. This is why there is a renewed call for the use of indigenous languages in most African nations to promote learning in formal school settings. Royal Commission on Aboriginal People (Citation1996) supports this position by emphasizing that when few children learn and use their language, their cultures and identities will be lost. This is due to the fact that such languages transmit and enhance a rich way of understanding and making meaning out of the experiences we have as humans (Ball, Citation2006; Battiste, Citation2005; Task Force on Aboriginal Language and Cultures, Citation2005). Translating the cultural values, symbols, words, proverbs and idioms of one culture into another is often a difficult task because some meanings can be lost. So when children begin the use of their indigenous languages at infancy, they are better able to link their identities to where they come from and can better understand indigenous knowledge (Crystal, Citation1997).

It is upon this premise that this paper proposes the use of the under listed strategies for indigenous-based language instructions in South African schools. What the South African media can do in each stage is also outlined as follows:

1: The first strategy is the provision of human and material resources lacking in Indigenous Languages: Lack of human and material resources has been mentioned as the major stumbling block towards the actualization of LIEP in South Africa, (Brock-Utn’e, Citation2003; Mukana, Citation2017; Prah, Citation2006). Although Government of South Africa made provisions in the policy for indigenous languages to be used in schools, the resources for the actualization of this policy have not been provided. Even in cases where they have been provided, they are inadequate. Most of the institutions where these courses were taught no longer exist. Similarly, the departments offering African languages in some universities in the country have been scaled down (Klu et al., Citation2013). The media can create awareness of this problem and make it an item in the agendas of the three arms of government in South Africa so that a lasting solution can be found. The Canadian media as noted by Ball & McIvor (Citation2013) helped in setting the agenda that revitalized most Aboriginal languages. They pointed out how such function of the media created an awareness that made university of Victoria to partner with an indigenous education centre to co-create a university-accredited certificate in Aboriginal language, which developed into a baccalaureate teaching degree indigenous languages that are available in their catchment area. Typically, an indigenous language speaker from the local community is employed to teach students on a part-time arrangement.

Similarly, awareness by the media helped in the formulation of policy that made British Columbia’s Ministry of Education to come up with a system whereby schools can develop curriculum in English or French and teach it as a second language from Grades 5 to 12, (Hinton, 2001a). This has been helpful in the revitalization of indigenous languages

in some communities as noted by Johns & Mazurkewich (Citation2001), Smith & Peck (Citation2004); Stikeman (Citation2001) and Suina (Citation2004). It has been emphasized that first language speakers do not often encounter any difficulty of learning their languages, (Jacobs, Citation1998; Kirkness, Citation2002). South African media should engage in enlightenment campaigns that will encourage South Africans to become their indigenous language teachers, linguists, interpreters, translators, curriculum developers and researchers. On material resources, media professionals can help by disseminating information on how dictionaries, audio tapes of speakers, computers and CD-ROMS could be incorporated into the teaching and learning of indigenous languages as advised by Morrison and Peterson (Citation2003). An example of such technology is the Web-based resource, FIRSTVOICES, which is a multimedia that documents and archives indigenous languages into text, sound and video clips, (First People’s Cultural Foundation, Citation2003). This is not new as some indigenous language groups have created their own writing systems or continued to modify the ones earlier developed (Brand, Elliot, & Foster, Citation2002; Hinton, Citation2001b).

On the role of media based on this first strategy, appropriate awareness should be created using media tools. Such tools can be in form of news, commentaries, editorials, features. By producing and airing of programmes using indigenous languages, the media would have succeeded in performing the function of status conferral on these languages. By so doing, indigenous people would be proud to communicate in their indigenous languages. Phone-in programmes can also be used to seek people’s suggestions towards the issue at hand. Also, through media programmes, South Africans with philanthropic spirits can be called upon to partner with Government in establishing training centres in some communities. The media can equally call on corporate organizations in South Africa to donate resource materials needed in the teaching and learning of indigenous languages. This strategy is already working in Nigeria where Federal Radio Corporation of Nigeria (FRCN) and other media organizations air educational programmes in indigenous languages available in their areas of location.

2: The second strategy is to develop an academic curriculum that will encourage the teaching and learning of indigenous languages in schools. Curriculum development according to Wilson & Karma (Citation2001) is effective for revitalizing any language. Some instances are the Cree for kids videos created by Screen Weavers Studio (Citation2002), and the Disney movie, Bambi created by Stephen Greymorning (Citation2001). Similarly, a Hawaiian group collaborated with Apple in creating an operating system completely in Hawaiian, the first time a MAC OS was ever made available in an indigenous American language, (Warschauer, Donaghy & Kuamoyo, Citation1997).

Media role in this case will be producing and airing of curriculum based educational programmes using indigenous languages. This will help learners at home to master instructional materials even when at home. Yaunches (Citation2014) notes an all-Navajo radio station and the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation produced and aired educational programmes in indigenous languages for up to five and half hours a week. This was done to complete formal instructions in schools in those indigenous languages. South African media can successfully do the same thing. Sponsors can be invited to sponsor the programmes and buy air time for their products as well.

3: The third strategy centres on modernizing and upgrading indigenous languages. It is important to continually upgrade and build modern day expressions, words and symbols in such a way as to capture young people’s attention and interest without having to revert to English, (Anthony, Davis & Powell, Citation2003). Recent examples of where this strategy has worked successfully are in Quebec. A Cree Health Board in Quebec was tasked with creating new words for health terms such as pancreas and insulin and circulating them through the media and it was done to the admiration of the country’s Government and Non-Governmental Organizations, (Bonspiel, Citation2005). Also, Hawaiian computer project led to the successful creation of new Hawaiian words such as “hoyouka- the same word for loading a canoe” for “upload”; and “malama- part of a phrase that means to take proper care” for “save”, (Warschauer et al., Citation1997).

The South African media can produce enlightenment and awareness programmes based on this third strategy. Such programmes will be aimed at calling on the academia or linguists who are experts in word creations to partner with the appropriate Government Education Boards and Agencies in order to make this a reality. Even when these new words are created, it is the job of the media to make them known to the public and even use such words in their productions.

4: The fourth strategy is research. There is a need for continuous research on indigenous languages. Every serious academic endeavour needs continuous research in order to uncover trends and innovations. There is a need to seek answers to important questions through research. This is needful to effective teaching and learning of indigenous languages. This will help in the digging-up of facts about the languages, theorizing about them and producing effective instructional materials where necessary, (Anthony et al., Citation2003; Blair et al, Citation2002; Czaykowska-Higgins, Citation2003; Shaw, Citation2001).

Media role here should be disseminating information on the need for partnerships between Government and linguistic scholars. Media should also give information concerning the availability of research grants provided by Government, if any and also give details of how to apply for such grants. By so doing, professionals or researchers in this research entity will be motivated to take up research tasks that will yield interesting findings. It is the role of the media to disseminate and publicize research findings especially in situations that require public attention and actions. Most importantly, the media should allow people voice out complaints on instructional materials developed by researchers. This is necessary in order to fine tune the strategies if need be. This approach has been useful in Tanzania during the Mkukuta1 review and evaluation. Tanzanian media were key in the process just as in the final stages of completing their Millennium Development Goals phase one.

5: The last but not the least strategy is the creation of immersion programmes for indigenous languages. The indigenous immersion method is being recognized as one of the most effective tools for revitalizing indigenous languages. Hermes (Citation2007), infers from the works of Aguilera and LeCompte (Citation2007), Greymorning (Citation2000), Kipp (Citation2000), McCarthy (Citation2002) and Wilson and Kawai’ae’a (Citation2007) to assert categorically that: “indigenous language immersion is the pedagogy of choice among indigenous communities seeking to produce a new generation of fluent speakers”. Early childhood total immersion programme exclusively using indigenous language as the vehicle for interaction and instruction is considered one of the most successful language revitalization models in the world. Tekohango Reo, according to Kirkness (Citation1998), McClutchie-Mita (Citation2007), King (Citation2001) and Yaunches (Citation2014) is a typical example. After hearing about the success of this programme in Aotearoa, New Zealand, a small group of Hawaiians travelled to New Zealand in the early 1980s to study what Maoris were doing, (Warner, Citation2001). Now, in both Aotearoa and Hawaii, entire generations of speakers have emerged through immersion programming, (Warner, Citation2001; Wilson & Kamana, Citation2001). Since this programme has worked in these instances cited above, the Government of South Africa through the Education Board can implement this model in the Education system to strengthen the indigenous languages.

The role of the media towards the success of immersion programme will be to persuade both the Government and stakeholders to adopt this model in the education sector. Through commentaries and editorials, the media can effectively set the right agenda that can snowball into the final adoption of the immersion programme. It is equally the function of the media to educate and enlighten the entire South Africans on the need to send their children to centres designated for the programme. The venue for the programme, its take off and closing time, will all be part of the information which the media will make available to the public through appropriately scheduled programmes.

6. Conclusion and recommendations

The South African Government has come up with the Language-in-Education Policy which stipulates the use of indigenous languages as a medium of instruction and as a subject of study. A review of related literature shows there is a gap between the policy intent and its implementation. The South African media, being the watch dog of the society have many roles to perform as it concerns the full implementation of the LIEP.

News is aired to make issues known and basically as a way of disseminating messages to a large group of people (Babalola, Citation2002). It is the responsibility of the media to disseminate messages about government policies. It is equally the responsibility of the media to keep updates on these policies. The strategies that will help the teaching and learning of indigenous languages is South African schools are yet to be fully disseminated among Governmental bodies, teachers, school administrators, and even parents.

South African media can set agenda on this topic which can trigger off discussions and eventual adoption by stakeholders (Muyagi & Olengurumwa, Citation2016). In this respect, the media is seen as the fourth arm of the government which functions extensively in policy implementation.

Public awareness regarding the LIEP strategies for teaching and learning of indigenous languages in schools can be handled by the media through various media tools like press releases, news articles, features, interpretive stories, context-setting stories, editorials, columns and even cartoons. The use of these media tools has been successful in various countries as noted by Fairclough (Citation1995), Richardson (Citation2007), Schudson (Citation2000) and Muyagi and Olengurumwa (Citation2016).

In the context of policies and their implementations, it is the responsibility of the media as the fourth arm of government to provide forum for citizens to join in the discussions and be a link between government and masses (Lule, Citation2013). Media can create and hold public interest on topical issues. They can initiate and direct discussions on a policy debate by setting agenda and by conferring status on such issues. Media also can determine the nature, sources and outcomes of policy issues (Soroka, Lawlor, Farnsworth, & Young, Citation2011).

In view of the position of this paper concerning the LIEP, the following recommendations are made:

that in order to fully actualize the intent of the LIEP, the media in South Africa must wake up and perform the agenda setting roles, awareness creation and education and watchdog functions of the media profession. They must be socially responsive to the demands of the society towards this policy.

that the strategies proposed in this study be publicized by media organizations in South Africa for their application in the education setting.

that continuous evaluation be carried out in the LIEP in order to further make adjustments where necessary.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Angela Nkiru Nwammuo

Angela Nkiru Nwammuo is an emerging Scholar who holds PhD and MSc in Media and Communication Studies. She is a permanent staff of Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Anambra State–Nigeria but currently a Post-Doctoral Fellow at Indigenous Language Media in Africa (ILMA) research entity at North West University (NWU) Mafikeng Campus, South Africa.

Abiodun Salawu

Abiodun Salawu is a Professor of Journalism, Communication and Media Studies and the Director of ILMA research entity, NWU-South Africa. He has taught and researched Communication Studies for decades and is rated by NRF as an established researcher.

The authors are domiciled at ILMA research entity of Faculty of Humanities at NWU and are studying indigenous languages in Africa with a view to finding out how some of the languages already going into extinction could be revitalized. This present paper is part of the on-going researches which will blossom into wider projects at the entity.

References

- Aguilera, D., & LeCompte, M. (2007). Resiliency in native languages: The tale of three indigenous communities’ experience with language immersion. Journal of American Indian Education, 46(3), 11–36.

- Alexander, N. (2003). Language policy and national unity in South Africa. Cape Town: Buchu Books.

- Anthony, R. J., Davis, H. and Powell, J. V. (2003). Kwak'wala language retention and renewal: A review with recommendations. Accessed Februaury 15, 2018, from http://www.fpcf.ca/programs-lang-res.html.

- Babalola, E. T. (2002). Newspapers as instruments for building literate communities: The Nigerian experience. Nordic Journal of African Studies, 22(6), 10–21.

- Ball, J. (2006). Enhancing learning of children from diverse language backgrounds: Mother-tongue based bilingual or multilingual education in early primary school years. Paris: UNESCO.

- Ball, J., & McIvor, O. (2013). Canada’s big chill: Indigenous language in education. In C. Benson & K. Kosinen (Eds.), Language issues in comparative education (pp. 19–38). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Battiste, M. (2005). Maintaining indigenous language and culture in modern schools. In M. Battiste (Ed.), Reclaiming indigenous voice and vision (pp. 193–208). Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

- Blair, H., Rice, S., Wood, V., and Janvier, J. (2002). Daghida: Cold lake first nation works towards dene language revitalization. In B. Burnaby, and J. A. Reyhner (Eds.), Indigenous languages across the community. Flagstaff, AZ: Northern Arizona University: Center for Excellence in Education.pp.89-98.

- Bonspiel, S. (2005). How do you say pancreas in cree? school board and linguists collaborate to cree-ate new words. The Nation, pp. 7–9

- Brand, P., Elliot, J., & Foster, K. (2002). Language revitalization using multimedia. In B. Burnbaby & J. Reghner (Eds.), Indigenous language across the country (pp. 35-46). Flagstaff, AZ: Center for Excellence in Education: Northern Arizona University.

- Brock-Utn’e, B. (2003). The language question in the light of globalization, social justice and democracy. International Journal of Peace Studies, 8(2), 50–67.

- Chick, K. (1996). Language policy in the faculty of humanities: Discussion document. Unpublished Manuscript. Durban, South Africa: University of Natal.

- Cormack, M. (2003). Developing minority language media studies. Proceedings of Mercativ International Symposium, Aberystywyth, UK: University of Wales.

- Crystal, D. (1997). English as a global language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Czaykowska-Higgins, E. (2003). $900,000 programme to revitalize Island aboriginal languages. Media Release Houston: University of Victoria Press.

- Department of Education RSA. (2002, November 13). National policy framework; Final draft. Pretoria: National Department of Education.

- Department of Education RSA. (2003). Ministerial report on the development of African indigenous languages as medium of instruction in higher education. Pretoria: National Department of Education.

- Fairclough, N. (1995). Media discourse. London: Arnold Publishing.

- First People’s Cultural Foundation. (2003). First Voices. Retrieved April 14, 2018, from https://www.fact.ca/resources/first%20voices/default.htm

- Greymorning, S. (2000).Hinono’eitiitihoowu’- Arapaho language lodge: A place for our children, a place for our hearts. Retrieved March 30, 2018, from https://www.nativelanguages.org/arapaho.htm

- Greymorning, S. (2001). Reflections on Arapaho language project or when Bambi spoke Arapaho and other tales of Arapaho language revitalization efforts. In L. Hinton & K. Hale (Eds.), The green book of language revitalization in practice (pp. 287–297). San Diego: Academic Press.

- Hermes, M. (2007). Moving towards the language reflections in an indigenous-immersion school. Journal of American Indian Education, 46(3), 54–71.

- Heugh, K. (2012). The case against bilingual and multilingual education in South Africa. In K. Heugh, A. Sigruhn, & P. Pluddemann (Eds.), Multilingual education in South Africa (pp. 449-475). Cape Town: Heinemann.

- Hinton, L. (2001b). New writing systems. In L. Hinton & K. Hale (Eds.), The green book of language revitalization in practice (pp. 239–250). San Diego: Academic Press.

- Jacobs, K. A. (1998). A chronology of Mohauk language instruction at Kahnawlaike. In L. A. Grenoble & L. J. Whaley (Eds.), Endangered language: Current issues and future prospects (pp. 117–123). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Johns, A., & Mazurkewich, I. (2001). The role of university in training of native language teachers. In L. Hinton & K. Hale (Eds.), The green book of language revitalization in practice (pp. 355–366). San Diego: Academic Press.

- Kamwangamalu, N. (2004). The language policy/language economics interface and mother-tongue education in post-apartheid South Africa. Journal of Language Problems and Language Planning, 28, 131–146.

- Kamwangamalu, N. M. (2014). Effects of policy on English medium instruction in Africa. Retrieved March 20, 2018, from Onlinelibrary.wiley.com

- King, J. (2001). Tekohanga Reo: Maori Language Revitaliztion. In L. Hinton & K. Hale (Eds.), The green book of language revitalization in practice (pp. 119–128). San Diego: Academic Press.

- Kipp, D. (2000). Encouragement, guidance, insights and lessons learned for native language activists developing their own tribal language programme. St. Paul, MN: Piegan Institute.

- Kirkness, V. (1998). The critical state of aboriginal language in Canada. Cnadian Journal of Native Education, 22(1), 93–108.

- Kirkness, V. (2002). The preservation and use of language: Respecting the natural order of creator. In B. Burnaby & J. A. Reyhner (Eds.), Indigenous languages across the country (pp. 17–23). Flagstaff, AZ: Northern Arizona University: Center for Excellence in Education.

- Klu, E. K., Neeta, N. C., Makhwathana, R. N., Gudlhuza, W. J., Maluleke, M. J., Mulaudzi, L. M. P., & Odoi, D. A. (2013). Arguments for and against indigenous languages in South AFrican schools. Stud Tribes Tribals, 11(1), 35–38. doi:10.1080/0972639X.2013.11886662

- Klu, E. K., & Quan-Baffour, K. P. (2006). A mismatch between education policy planning and implementation: A critique of South Africa’s inclusive education policy. African Journal of Special Education Needs, 4(2), 285–291.

- Language-In-Education Policy RSA. (1997, December 19). Department of Education (LIEP Government Gazette No. 18546), Pretoria.

- Lule, J. (2013). Understanding media and culture. Irvington: Flat World Knowledge.

- Manyike, T. V. (2013). Bilingual literacy or substantive bilingualism? L1and L2 reading and writing performance among grade 7 learners in three selected township schools in Gauteng Province, South Africa. African Education Review, 10(2), 187–203. doi:10.1080/18146627.2013.812271

- McCarthy, T. (2002). A place to be Navajo: Rough rock and the struggle for self- determination in indigenous schooling. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- McClutchie-Mita, D. (2007). Maori language revitalization: A vision for the future. Canadian Journal of Native Language, 30(1), 101–107.

- Morrison, S., & Peterson, L. (2003). Using technology to teach native American languages. Retrieved April 23, from https://www.cal.org/ericll/langlink/feb03feature.html

- Mukana, E. (2017). Rethinking language of instruction in African schools in policy and practice. Development Education Review, 4(1), 53–56.

- Muyagi, P., & Olengurumwa, O. (2016). Media and public policy: Analysis of the dissemination of national policy mainstream media. International Journal of Innovative Research, 2(8), 15–28.

- O’Hlfearnain, T. (2010). Irish language broadcast media: The interaction of state, language policy, broadcasters and their audiences. Current Issues in Language and Society, 7(2), 92–116. doi:10.1080/13520520009615572

- O’Laoire, M. (2010). Language policy and the broadcast media: A response. Current Issues in Language and Society, 7(2), 149–154. doi:10.1080/13520520009615575

- Prah, K. W. (2006). Challenges to the promotion of indigenous languages in South Africa: review commissioned by foundation for human rights in South Africa. Cape Town: Center for Advanced Studies of African Society.

- Richardson, J. (2007). Analyzing newspapers: An approach from critical discourse analysis. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Royal Commission on Aboriginal People. (1996). Gathering strength: Report of the royal commission on aboriginal people. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services.

- Schudson, M. (2000). The sociology of news production revisited. In J. Curran & M. Gurevitch (Eds.), Mass Media and Society (pp. 175–200). London: Arnold.

- Screen Weavers Studio. (2002). Ceefor kids video DVD. Moberly Lake, BC: Screen Weaver.

- Shaw, P. (2001). Negotiating against loss: Responsibility, reciprocity, and respect in endangered language research. In F. Endo (Ed.), Proceedings of the 2nd international conference on the endangered languages of the pacific rim (pp. 1-13). Kyoto: ELPR.

- Smith, D., & Peck, J. (2004). Wksitnuow wejkwapniaqewa - mi'kmaq: A voice from the people of the dawn. McGill Journal of Education, 39(3), 342-353.

- Soroka, S., Lawlor, A., Farnsworth, S., & Young, L. (2011). Mass media policy making. Retrieved March 25, from https://www.snsoroka.com/files/mediaandpolicymaking.pdf

- South Africa. (1993). South Africa new language policy. Pretoria: Department of National Education.

- Stikeman, A. (2001). Talking my Language. Canadian Geographic, 12(1), 26.

- Stuart-Smith, J. (2006). The influence of media. In L. Liamas, L. Mullang, & P. Stockwell (Eds.), The Routledge companion to socio-linguistics (pp. 140–148). UK: Routledge.

- Suina, J. H. (2004). Native language teachers in a struggle for language and cultural survival. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 35(3), 281–302. doi:10.1525/aeq.2004.35.3.281

- Task Force on Aboriginal Language and Cultures. (2005). Towards a new beginning: A foundational report for a strategy to revitalize first nation inuit and metis languages and cultures. Ottawa: Department of Canadian Heritage.

- Taylor, S., & Coetzee, M. (2013). Estimating the impact of language of instruction in South African primary schools: A fixed effects approach (Working Papers 21/2013). Stellanbosch University, Department of Economics and the Bureau for Economic Research.

- Trudgill, P. (1986). Dialects in contact. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Trudgill, P. (2006). Norwich revisited: Recent linguistic changes in English urban dialect. English Worldwide, 9, 33–49. doi:10.1075/eww.9.1.03tru

- UNICEF. (2016). Language and learning in South Africa. Retrieved March 28, from https://www.unicef.org/esaro/unicef(2016)languageand learningsouthafrica.pdf

- Warner, S. (2001). The movement to revitalize Hawaiian language and culture. In L. Hinton & K. Hale (Eds.), The green book of language revitalization in practice (pp. 134–144). San Diego: Academic Press.

- Warschauer, M., Donagh, K., & Kuamoyo, H. (1997). Leoki: A powerful voice of Hawaiian language revitalization. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 10(4), 349–361. doi:10.1080/0958822970100405

- Wilson, W. A., & Kamana, K. (2001). Mailokomai o Kai T’ini: Proceeding from a dream – The Aha Punang leo connection in Hawaiian language revitalization. In L. Hinton & K. Hale (Eds.), The green book of language revitalization in practice (pp. 147–176). San Diego: Academic Press.

- Wilson, W. A., & Kawai’ae’a, K. (2007). Ikumu; Ilala: Let there be sources; let there be branches: Teacher education in the College of Hawaiian Language. Journal of American Indian Education, 46(3), 38–55.

- Yaunches, A. (2014). Building a language nest: Native peoples revitalize their language using a proven approach from across the globe. Rural Roots, 5(3), 1–8.