Abstract

Power has always been an obvious presumption in planning theory. At times it has been considered as a one-way, top-down, instrumental and rational dominance while at other times, planning theory, in more fortunate moments, has tried to divide concepts of power between different actors through a communicative rationality-based process. This article locates Foucault’s theory of power in relation to recent planning theories as a magnifier in order to reveal the invisible or neglected lines of urban planning theories. The paper shows how the epistemology of power occurs in the six urban planning theories of synoptic, incremental, transactive, advocacy, bargaining and communicative. Finally, the main point of Foucault’s power theory will be derived into two suppositions: firstly, where planning results from the normalization of free and formal subjects when the power game of the government has been rejected; secondly, the characteristics of planning and planner from a power point of view are explained by understanding planning as an opportunity for the presence of power and resistance.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The urban planning theories have seen as a tool in the hand of those who have power like government or as a way for minorities and marginal groups which makes their voice be heard by authorities. The first view which is called top-down planning and second one is based on participation of people in the process of planning. This paper aimed to investigate about power layers that hidden behind the structure of urban planning theories. In order to define power, this paper focused on Foucault point of view about power and tried to employ Foucauldian power theory as a lens to read the urban planning theories. The urban planning theories which discussed in this paper includes six different type (paradigm) from top-down planning to participation planning. As the result, the characteristics of planning and planner from a power point of view are explained by understanding planning as an opportunity for the presence of power and resistance.

1. Introduction

Since the dominance of the era of instrumental rationality, which has been realized through blueprint planningFootnote1 models and recent theories like communicative theory, planning theories have emerged with specific aims and processes. However, according to some scholars, recent planning theories mourn the scarcity of limited public participation opportunities and have raised public participation as one of the main traits of policy determination and planning process within new theories. In fact, the role of the state has become the government in planning and it is possible to identify a series of “new technologies of governing”, such as governing by swarms (Reddel, Citation2002; Rose, Citation2000), “third way” strategies (Giddens, Citation2013; Rose, Citation2000), decentralization of governing in favor of civil society (Fischer, Citation2000) and partnerships between the private and public sector (Edwards, Citation2002; Teisman & Klijn, Citation2002). However, there is a hidden significance of participation discussion in planning theories: the power assumed evident by many planning theories.

Many scholars have surveyed the concept of power in planning. Hillier (Citation2002) believes that the practices of planning have not yet penetrated into theory. Some practices including those related to issues of power about the selected agents of planning committees that sacrifice the suggestions of authorities for the sake of social justice or for the market facilitation, are set within the context of crowded city halls and proscenium of local elections (Hillier, Citation2002). “In practice, planners are dealing with social and political forms of unsound management of knowledge, contentment, reliance, and consideration of citizens when it comes to encountering the power manifesto,” says Forester (Citation1988: 67) about planning confronting systems of power. Apart from Hillier and Forester, who are specifically engaged with power in planning systems, Healey’s article (Citation1998) deals with the Institutionalization capacity of collaborative approaches and presents an analysis of government power. Scholars have also worked through case studies, such as recognizing power relations within the urban environment of Singapore (Yeoh, Citation1998) or the methods of controlling society through planning as an instrument of power in Africa (Njoh, Citation2009). Nonetheless, power is a complicated concept with different meanings and traits throughout diverse theories.

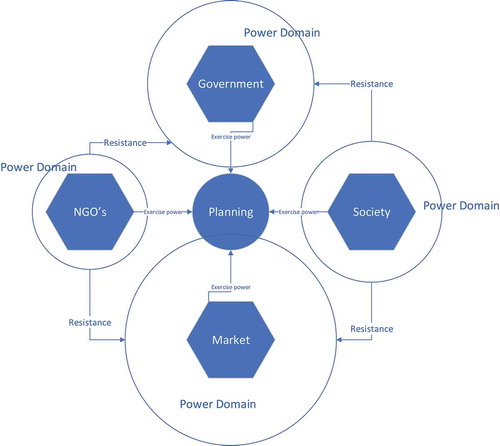

It might be said that the theory of power is as old as the history of philosophy. The scope of power theory starts from Plato and Aristotle and brought to the contemporary era through Machiavelli’s theory (Winslow, Citation1948). In the current era, Gaventa’s theory of power is based on a model of power and powerlessness (Gaventa, Citation1982) and Mann’s organizational outflanking determines a number of essential organizational resources and tools in order to activate these resources for effective resistance against power. From his point of view, the advantage of power relations goes to those who have a better organization (Mann, Citation1986). Moreover, Clegg’s triple circuit of power consists of the power obvious circuit, power social circuit and power systemic and economic circuit (Clegg, Citation1989) while Giddens’ power theory should be mentioned as a part of a social theory that he terms structuration (Giddens, Citation1984). Nevertheless, Michel Foucault’s theory of power represents a pivotal moment in the modern understanding of the concept of power. Foucault’s approach presents power as a sort of software; whereas, in the past, power was assumed to be a hardware or an object belonging to a specific class of society (Figure ). While power had been considered top-down and concentrated centrally in traditional views, Foucault proposed that power rises from the bottom-up and is present wherever domination is concentrated (Grosz, 1990).

Figure 1. Presumed current of power and resistance among urban planning actors (Based on Rafieian and Jahanzad, 2015: Page: 255).

The purpose of this article is to survey urban planning theories from Foucault’s point of view on power theory. In order to achieve this goal, firstly we intend to question our knowledge about planning theory and then how the knowledge of power can make visible the hidden layers of planning theories which, until now, have been neglected. Therefore, this article deals with the epistemology of power in urban planning and also the source of knowledge. In this article, logical knowledge is located within the category of critical paradigm. For this reason, the conceptual framework of the research has been first determined and then the Foucauldian survey of urban planning executed. In conclusion, two assumptions are illustrated for urban planning.

2. Conceptual framework

First of all, it is necessary to define the field of discourse and consequently elaborate some concepts imaginable within it. In this article, there are two discourses to address: the first being the work of Michel Foucault’s power theory and the second being existing urban planning theories of power. Foucault did not present a single orderly doctrine of power. He located himself peacefully in between conflicts and debates which have created his approach and theory. He did not believe in some steadfast truths, but instead uncovered certain layers that should be eliminated. Although he was influenced by the theory of phenomenology, he did not string along with the main ideas of the day. His writing illustrates an element of strong structure, but he did not produce a model within his writings and refused to create a monotone model from its rules (Hall, Citation2001). Foucault was influenced by Weber and Marx, but unlike them, he did not feel any commitment to a comprehensive analysis of organizations or economic dimensions. He analyzed a different social entity each time and despite his asserted preference to focus on micro-politics of power, his theory is full of macrostructural tenets (Ritzer, Citation1988; Walzer, Citation1986).

Foucault employed Nietzsche’s ideas about the relation between knowledge and power (Lash, Citation1991). He presumed a correlation between power and knowledge which cannot be separated. Foucault considers each social relation as power relevancy. However, he stipulates that each power relevancy does not necessarily lead to dominancy (Deleuze, Citation1988). In his view, the power structure of modern society is dependent on a system of relations based on knowledge (a network of knowledge-power) which embeds the individual within. This network means that while the individual becomes known (either by registering in outer offices or understands and classifies him or herself from the inside in accordance with the imposed norms and knowledge of society) or goes through systems of knowledge such as medicine, psychology or education, becomes visible and in this way is placed under the dominancy of power (Foucault, Citation2012b). Power even impresses upon the body of an individual through education and the regularizing of life, which is why we can discuss the life-power and life-politic that desires to be applied to the body and organize it according to its own desired order (Foucault, Citation2012c). Nonetheless, Foucault, in the end, says that his main purpose has not been to study power, but rather to survey the nature of subject, meaning that the individual’s formation which someone who is known because of it and of course, at the same time, put him or herself under subjugation of higher power (Dreyfus & Rabinow, Citation2014).

In “Microphysics of Power”, Foucault surveys the visages of power and analyzes them:

Power does not exist in a particular place, but it has penetrated into all aspects of life in modern societies. This means that it does not have any central location and far from the notion of Marxist-Leninist theorists, it is not arranged from top-down as in a hierarchy (power embraces all people in society and the individual is, in fact, the consequence of that power).

Power cannot be captured, but it affects the tiniest elements of society.

Power does not necessarily rise from economic affairs and it cannot be understood solely through the forces of autonomy and dependence.

Everything and everyone orbits power and structures of power are always dynamic and fluid (Foucault, Citation1985).

The mentioned study of microphysics requires that to consider the applied power as a strategy and not as a trait requires domination of this power over hierarchies, maneuvers, tactics, techniques and functions rather than a takeover. Power should be considered as a network of ever-growing relations and actions, not as an achievable advantage that necessitates knowing the permanent pattern of power, an agreement that transacts or triumphs over a territory. Overall, it must be accepted that power can be applied and not possessed. Neither can power be achieved or retained as an “advantage” by a ruling class, but it is the general effect and results of strategic situations of this class—an effect that reveals and sometimes accompanies the situation of the levels of society which have been dominated.

Planning theories have emerged in different eras and proposed by different scholars. The following sections question the common aspects between power theory and other planning theories in order to reveal the similarities and differences between these discourses. In order to find a common aspect, it is essential to define the main proposition of power theory. According to Foucault, power exists only when there is la résistance, otherwise, there is only dominance and people under the pressure of that rule (Dreyfus & Rabinow, Citation1982; Foucault, Citation1982). According to this proposition, it is understandable that the combination of these two discourses should be located where the planning theory places different actors in its process. Consequently, planning theory that considers participation shares a common aspect with power theory.

One of the most important revolutions in planning thinking occurred in the late 1950s and 1960s when synoptic planning or systems overcame blueprint planning in the United States and later in Britain (Hall, Citation1983; McLoughlin, Citation1969). Hall declares that the urban geographical changes caused by cars forced planners to deal with challenges which “did not exist in such a level” (Hall, Citation1983). The new large-scale problems compelled planners to survey these problems using the conceptual or mathematical models that connect the aims (goals) to the tools (resources and constraints) by heavily relying on numeral and quantitative analyses from a systems point of view (Hudson, Galloway, & Kaufman, Citation1979).

Although synoptic planning at one level addresses the continuation of comprehensive rational paradigm, at another level, it deals with the fast and important departure from blueprint planning. As Hudson et al. (Citation1979) discuss, synoptic planning is known as the starting point of many diverse strategies rising from critical analyses on defects of this form of planning.

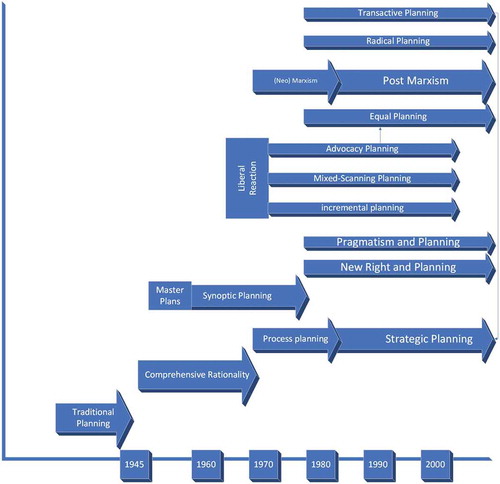

In the late 1960s, the intense criticism to the rational-comprehensive paradigm caused the emergence of new models of planning (Friedmann, Citation1994; McDonald, Citation1989). But, as a result of these models, no united model of planning developed. Instead, a wide range of new strategies was proposed, all of which have the same purpose of overcoming numerous criticisms of the ideal of the synoptic. All of them, such as transactive, advocacy, Marxist, bargaining and communicative approaches were primarily derived from the social evolution of the planning tradition rather than the tradition of social guidance which has aged significantly (see Figure ) (Friedmann, Citation1994).

According to the concepts expressed by Foucault, the survey of urban planning theories can be divided into three categories. In the first group (first wave), the transition from dominance to power is brought up prior to Foucault’s theory of power and accompanied synoptic and incremental theories. The second wave regards the formation of power and resistance and the advocacy and bargaining theories which are surveyed. Finally, the third wave focuses on the relation of power/knowledge with transactive and communicative theories studied from a power point of view.

3. First wave- the transition from domination to power

It was in the context of system planning, which for the first-time requests for public association in planning processes occurred (Faludi, Citation2013). Hall (Citation1983) declares that consulting (following changes to the law in 1968), implemented by British planning authorities, was part of the development goals and systematic process, led by the professional planner. He argues that this will change the fundamental direction in the role of planner and his\her relationship with the public (Hall, Citation1983).

The important fact is that synoptic idolizers still cling to the notion of a unitary public interest. In Faludi’s terms, the synoptic model image of society is a “Holistic” image and the inducer of hegemony of interest (Faludi, Citation2013). The planner, within synoptic planning processes, is substituted by a medieval priest in the role of social reformer. It presents holistic images of the community where solutions for city issues are found through the standardization of land use per capita and showcases the efforts of a sovereign government that produces “norms”. Similarly, the concept of prison in the notion of Foucault’s’ Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (1975) shifts a person from being abnormal to normal, the synoptic planner in order to maintain the interests of government tries to solve urban issues (malformed) by the elimination or modification of the problems (normalization), through the production of laws and regulations and afterward the implementation of the laws by its operator (Planner and City authorities). By exercising this power by the government for the community, knowledge could be born which shows that a distance between planner and public participation should be constantly kept due to the lack of domination of the public by the knowledge of urban planning expertise. This knowledge contains professional discussions which intend to exercise its superiority over society and remains subjugated by the government. Accordingly, examples of synoptic planning can be found in the concept of “domination.”

The above point has three usages for the role of public participation in planning. First, it reduces the need and importance of public participation. Assuming society to be homogeneous, it means that participation is only needed for the accreditation and legitimacy of planning goals. Second, homogeneity ideology leads to legitimacy without criticism of planning activities and objectives (Kiernan, Citation1983). Eventually, the unitary interest tends to de-legitimize and stigmatize objections to planning proposals as parochial (Gariépy, Citation1991; Kiernan, Citation1983). In domination discourses, the government is framed as trying to guide behavior and influence the actions of free subjects. The free subject is immersed in spaces of power and in the absence of resistance (la résistance) the government unifies the public interest. Domination is the birth of holiness of knowledge came from enlightenment era and can be critiqued just as the church’s actions during the Middle Ages -the Roman Catholic Church became organized into an elaborate hierarchy with the pope as the head in western Europe as a Supreme leader- were denounced. Similar to Middle-Ages which the church was in the center of everyday life and act as the divine government, enlightenment-era argued that the knowledge is the only way to gaining or understanding the truth and scientist act as the pope. And as Foucault (Citation2002) describes the psychologists are like median priest whom people confess their sins to them. Enlightenment era which gives birth to Positivism is not parallel to Middle Ages church but have so much similarities for instance the reason is the primary source of authority and legitimacy of every ideas as the holy bible once was in Middle Ages. Any comments regarding the information extracted during the knowledge process are illegitimate. The planner as the savior of humanity, the imagination of a homogeneous community accompanied by a hegemony of instrumental rationality is the undisciplined state exercising power and reproducing the Disciplinary Society. At a time when there is no resistance or during a situation where insubordination is impossible, the power of debate diminishes and only domination remains. Therefore, from the point of view of Foucault’s power theory, this scenario can be realized within Synoptic planning, which does not indicate the presence of power in the relationship between government and citizens, but citizens who are subordinate to force rather than power.

In seeking to solve the challenges of synoptic planning, Lindblom (Citation1959) stated that the logical model: (1) with the intellectual capacities of man and the adequacy of the information is poorly adapted (2) the policymaking makes no relation between truths and values (3) cannot go through the range of related variables and (4) contains a variety of conditions which policy-making problems reveal, but do not synchronize. The Lindblom (Citation1959) critiques the rational-comprehensive paradigm, originally related to its impractical nature. On the contrary, the incremental strategy provides relevant and practical guidance for decision-making (Lindblom, Citation1959). Muddling through means: (1) Make selections based on the margin; (2) Select from a limited range of policy making alternatives and a limited range of outcomes; (3) Continuously pursue goals; (4) Make restorative use of data; (5) Perform serial analysis and evaluation; (6) and adapt compensatory orientation and evaluation (Faludi, Citation2013; Lindblom, Citation1959). According to Lindblom (Citation1959, p. 87), limited sequential comparison is actually a method or system and “it does not mean the failure of the method which administrators ought to apologize”. Therefore, the instrumentalist variant of synoptic planning theory, known as the “disjointed incrementalist”, was an alternative strategy proposed by Lindblom (Citation1959).

As Hudson et al. (Citation1979) argue, the impact of institutions and players are hidden in the official policy-making arena of the incremental approach. Therefore, the incremental strategy confirms the pluralism of interests rather than a society-wide unitary interest and is ready to accept the limited decentralization of policymaking. Plans are the product of this view, as well as political and informational constraints, technical knowledge and intuition of the planner (Hudson et al., Citation1979). While public participation under incremental planning is nearly limited to consulting, the nature of decentralization and pluralism provides a mechanism to accommodate other actors (albeit unofficially), which is a significant change. The pluralistic nature of incremental planning in transition from synoptic planning to the theories where participation is a central goal can be considered as a transition from sovereignty to government. According to Foucault, no lawyer in history would consider a legitimate governor/ruler as one allowed to exercise his/her power over society with no other abilities (Dreyfus & Rabinow, Citation1982). Therefore, a ruler must always take the lead for a reason (common good or the salvation of all). In other words, the government is “the right disposition of things, arranged so as to lead to a convenient end” (Lemke, Citation2015). The right disposition of things is not known to necessarily navigate towards “the common greater good,” but indeed relies on each thing’s (human, territory or space as objective) “suitable goal,” which must be arranged precisely. This definition implies the plurality of specific goals, such as citizen accessibility to urban services or a focus on urban entrepreneurship in order to improve livelihoods which ultimately leads to a set of specific ends, thus becoming the goal of the government itself. To achieve these different ends, different aspects should be arranged. This term “arranged” is important. While laws allow the government to achieve its goals, the issue is not about imposing laws over humans but arranging things in such a way that the government plays with tactics, not laws. These tactics work with a certain number of methods (like public participation) in order to achieve planning objectives.

The pluralistic nature of incremental planning should not distort our view, but should be explained under shadow of the nature of pragmatism. This is the incremental pragmatism nature, which leads to an arrangement of things in order to meet particular targets. Public participation is one possible tactic which makes it possible to achieve certain purposes. This is similar to the art of governing—Arts de gouverner—which is connected with mercantilism and cameralism (Foucault, Citation1982), both of which aim to rationalize governance through the virtue of knowledge coming from the Doctrine of Statistics and Principles, which seeks to increase the power and wealth of the Government. Indeed, adopting public participation within incremental approaches can also be a tactic to allow planning to become more pragmatic and working towards legitimatizing the planning action of governments.

4. Second wave- the existence of both power and resistance

As McDonald (Citation1989) states, the failure of the synoptic ideal “has faced planners to challenge for finding new paradigm”. Advocacy planning in the same way can also be an answer to synoptic failure. Advocacy planning assumes a social and political pluralism (Mazziotti, Citation1974). Originally, Davidoff (Citation1965) spoke about Advocacy planning, although a more accurate description has been produced by Mazziotti (Citation1974).

The main propositions of the formation of advocacy planning are: (1) a deep inequality between groups from the point of power of bargaining; (2) unequal access to the political structure and (3) the un-organization of many people who are not represented by any interest groups (Mazziotti, Citation1974). These inequalities form the foundation of advocacy goals, which include the demanding of equality for all people and to embed all citizens in planning processes (Davidoff, Citation1965). Thus, advocacy planning stands at the heart of traditional radical social transformation and its concern of searching for social changes to mitigate uneven social situations by representing the interests of actors who have been less considered and discussed.

Power is not a phenomenon which can be transferred to people or be in the possession of government, but rather power is a mode of relationship between portions of society with a network nature, almost like a nervous system spreading throughout a community. With such an explanation, the first proposition of advocacy planning will be rejected (Dreyfus & Rabinow, Citation1982; Knights & Vurdubakis, Citation1994). In fact, what does not exist, is not equal bargaining power, but rather resistance to power. On the other hand, unequal access to political structures represents the efforts of the government to create a controlled society (Lemke, Citation2007). However, perhaps it can be said that a minority group that relies on an emotional plea and demonstrates oppression is in fact an attempt to exercise power and meet their own interests through the support of humanism theory. The third statement raises the issue of the lack of organized citizen/minority groups, but existence of a coherent structure in which its members are well managed and led by an institution does not, at least theoretically, differ from the structure of government. Therefore, as a government which tries to control the behavior of free subjects would be considered to dominate society (Lemke, Citation2015), so advocacy planning also desires to dominate urban planning processes. Although there are indeed differences between these two acts, domination by the government through planning processes has been defined as totalitarian systems, while the control of advocacy theory over planning processes has been interpreted through more popular vocabularies like democracy, recognizing the rights of minorities and equality. From Foucault’s point of view, the concept of physical justice/equality is part of general concepts and general facts which in different societies has been employed as an instrument to advocate for economic and political power or has been developed into a weapon to combat power. However, from the perspective of power, both approaches maintain similar natures.

Another theory attempting to replace synoptic theory is the bargaining model. The bargaining model is based on the fact that planning is an element of decision-making rather than a separate technical field (Faludi, Citation2013; McDonald, Citation1989). This strategy emphasizes that bargaining, within the range of parameters established by legal and political institutions, is the most important aspect of decision-making in mixed economies (Dorcey, 1986; McDonald, Citation1989).

In this context, bargaining is used as a transaction between two or more of the parties which illustrates that “each party bound to what to give and what to take or perform and receive of something (Dorcey, 1986)”. According to this view, planning decisions are a product of a transaction between active participants elaborated in planning. The mentioned model therefore digested anti-political ideologies of previous models and has recognized the fundamental political nature of planning. Similar to advocacy and Marxist planners, the school of bargaining recognizes the uneven distribution of power to bargaining, but indicates that all contributors have the effective capacity to influence decisions, even if just through voting, providing information for decision-making or the ability to prevent decision-making (McDonald, Citation1989).

The bargaining model can be considered as the planning theory closest to Foucault’s thoughts on power and resistance, where resistance stands in front of the exercising of power. This resistance stands against subjection and submission (Knights & Vurdubakis, Citation1994). According to Foucault’s argument, each power relationship represents a potential “fighting strategy” (Foucault, Citation1980). In the bargaining model, several players employ strategic discourses to support their own interests as a way of resistance against the power of the other party. For example, an investor in urban development argues for cost-benefit based on economic discourses and attempts to retain its interests in urban development based on financial relations and return on capital theories. On the other hand, the powerlessness that stands in the critical field is actually similar to the nature of power and workings of power relations (Heller, Citation1996). Consequently, environmentalist organizations employ naturalist discourses such as the need to preserve nature and existing environmental life in order to limit the progression of capital-based power and maintain their own benefit for the ecosystem. There are also other local institutions such as worker unions or the representatives of the lower class within the community that establish their place at the planning table by relying on general concepts such as justice or equality.

The key is hearing the voice of each actor in planning and that these voices can be examples of resistance to the exercise of power. On the other hand, in the bargain model, the exercise of power by an individual promotes others’ actions and reproduced by each other. This problem expresses the formation of a power network which in Foucault’s point of view, as much as in Nietzsche’s, operates as a plurality of forces under the tensions of “me—the other” (Ure & Testa, Citation2018). However, it should be noted that resistance exists not only in the bargain model but can also be found in any other kind of planning, though it may be that the actors or beneficiaries of planning do not have a proper understanding of their power. Planners, in addition to the power they possess, act as a mediator. This role is a very important point. The mediating planner in the bargain model does not create a collaborative space between players but serves as a leverage which prevents domination of the process of planning by a specific entity or group. This planner, of course, is not a lawyer of a particular kind (like advocacy planning) but is the one who tries to create a balance between various groups exercising power, even though a true balance may never actually be achieved.

While in normal models, like the ideal of the synoptic, public participation has certain functions such as providing information for the planner. According to bargaining analysis, the participation of various actors is the primary source of decision-making. Although public participation has priority in decision-making, according to the second analysis, participation is the main dynamic of decision-making

5. Third wave—power cycle/knowledge

Theories of planning after Foucault are interconnected by two concepts of participation as a goal of planning and empowerment. The main content of these theories was formed and completed in the 1990s. The first theory discussed in this wave is transactive planning, which Friedman first proposed in 1973 as a response to the failure of synoptic planning (Friedmann, Citation1973) and was fully articulated by Friedman in 1994 (Friedmann, Citation1994). Planning, through a transactive lens, with a reflection of Friedman’s theory, understands planning as a link between knowledge and practice and does not rely on empirical techniques; instead, it relies on interpersonal dialogues where ideas are validated through action (Friedmann, Citation1994). The main purpose of Transactive planning, along with the conservative social learning school from which Friedmann (Citation1987) traditional social transformation points towards, is two-way learning. In this way, transactive planning, instead of pursuing specific functional goals, places emphasis on personal and institutional development (Friedmann, Citation1994).

The main proposition of this planning theory considers planning to be far beyond the previous models in terms of opportunities for participation. Not only is the community of planning involved, which is part of the planning process, but one of the most important goals is also the decentralization of planning institutions by empowering the people to guide and control societal trends which determine their welfare (Friedmann, Citation1992; Hudson et al., Citation1979). According to this planning concept, participation and empowerment, instead of being used as a method, become targets to be acquired. Transactive planning conquered new fields in terms of the spectrum and role of public participation. The professional planner who distributes information and feedback while the public is invited to participate actively in policy and planning trends began a new era for public participation.

In this planning approach, guiding and controlling social trends through empowering people takes place in order to improve the welfare of the people themselves. Here, directing and controlling social trends are important. The government continuously works to guide and control the behaviors of free subjects (Foucault, Citation1991). But as Foucault admits, power in its bare state is much gentler and less dangerous than in its hidden form (Foucault & Ewald, Citation2003). Empowering people to guide and control societal trends is a technique to develop a norm which is an appendix of a common concept of general welfare. In this planning approach, empowerment is not merely the expanding of power to a range of individuals or the induction of knowledge, but rather a changing way to govern in planning based on the belief that previous theories have not succeeded in controlling space (territory) and human beings. As Miller and Rose (Citation2017) showed modern political rationalities and governmental technologies as to be intrinsically linked to developments in knowledge and to the powers of expertise. They clearly mentioned that:

“Key practices of rule were institutionalized within a central, more or less permanent body of offices and agencies, given a certain more or less explicit constitutional form, endowed with the capacity to raise funds in the form of taxes, and backed with the virtual monopoly of the legitimate use of force over a defined territory.”

The above sentence of Miller and Rose could be seen clearly in recent events in Paris which is called “Yellow Vests Protest” accompanying with 1400 arrests and 126 injuries (Matamoros & Graham, Citation2018) and the coincidence of a defined territory of rule and a project and apparatus for administering the lives and activities of those within that territory, conclude to speak of governmentality (or as Miller and Rose declared the modern nation-state) as a centralized set of institutions and personnel wielding authoritative power over a nation (for more study see: Beveridge, Citation2000; Della Porta, Citation2006; Mann, Citation1986, Citation1988; Paul, Ikenberry, & Hall, Citation2003). Undoubtedly, relying on social reform by individuals, is a reminder of discipline and punishment that starts to reach the discipline of community through the creation of domesticated bodies “Organismes domestiques” under the concept of bio-power (Foucault, Citation2012b).

Democracy in addition to freedom of information and debate presumes a discipline of citizens, a discipline that serves the public interest. Bio-power actually has two dimensions, the first being “Technologies of the Self” and the second “governmentality.” The first implies those techniques that act through the body, soul, thought and behavior, with one’s own tools and abilities (Foucault, Citation1988), in a way that changes oneself to reach the state of happiness (empowerment). Governmentality (Foucault, Citation1991) implies the methods that shape the view of the government’s supervision of its citizens, their wealth, their misery, rituals and their habits (planning). These two are not separated from each other, but each one provides conditions for the other to operate. Actually, from Foucault’s point of view, what can be assumed from the transaction between them is that the supremacy of empowerment distorts the concept of freedom and changes it and instead of guaranteeing the free movement of subjects tries to control and guide them in line with the public interest. However, there is another important point in the main proposition of transactive planning: the decentralization of planning institutions.

It should be asked then what this decentralization is and how it occurs. Decentralization provides aims to unlock power distribution and permit different players to participate in planning, but it can be imagined as the hidden layer that the government is responsible for arranging things in line with the purpose of public interest. It aims (Foucault, Citation1991) not only to reduce its costs but also to keep away the consequences of planning failure by putting planning action in the hands of non-governmental institutions and citizens. In this expression, the scope of power of individuals and institutions is undeveloped rather than the planning process being accompanied by a kind of public participation which has been allowed by the government to be disposed at the lower levels of society. We will explain more about this kind of public participation in the discussion of communicative planning.

In considering planners’ attention to the issues of participation and empowerment, the concept of mutual learning arises as part of the main core of planning in communicative theory. Healey (Citation1992) argues that the different kinds of “power-broking planning” has no role in the creation of “environmental planning”. In particular, she argues that environmental planning strategies understand profit as the source of power and describe bargaining as a creation of calculated power relationships among contributors that use the sophisticated, but empty language of the prevailing political power. No attempt is made to “learn about” the interests and perceptions of contributors which formed the basis of previous strategies. By possessing this knowledge, each of the contributors can review their thoughts about the others and their own benefits (Healey, Citation1992).

This point is where the main conceptual transformation occurs in the context of communicative theory. The declining authority of scientific rationalism posited the need to re-examine the nature and role of reason (Giddens, Citation1994; Healey, Citation1992; Hillier, Citation1993). The communicative Perspective is based on a set of convergent ideas which include: Habermas’s view (Citation1987) on the case of communicative rationality, the concept of deliberative democracy (Dryzek, Citation1994) and the idea of democracy dialogue raised by Giddens (Citation1994). Following Habermas (Citation1987), Healey (Citation1992) summarized the communicative perspective as instead of abandoning wisdom as the principal organizer of contemporary science, should consider our own perspective from the consideration of wisdom as an object-centered and solitary concept to the concourse in the form of interpersonal communicative (Dryzek, Citation1994).

The communicative strategy of planning considers public participation as an essential component. The importance of the relationship between subjects is its communicative model, which requires a variety of partnerships that develop forums for discussion, reasoning and discourse (Healey, Citation1992; Hillier, Citation1995). Moreover, the communicative strategy develops the spectrum of actors (and their concerns), which are considered legitimate in planning. Public participation in communicative planning should go beyond consulting to improve the situation. Instead, public participation in communicative theory is likely to include bargaining, negotiation and debate (Dryzek, Citation1994; Giddens, Citation1994; Healey, Citation1996).

In addition, according to the communicative perspective of planning, participation has a fundamental role. According to this view, planning means inducing, reasoning, discussion and participation in discourses leading to “Organizing attention to possible actions” (Forester, Citation1988). As a result, communicative planning cannot advance without the participation of relevant players.

Communicative planning includes the presence of knowledge that completes the power/resistance cycle. First, it must be noted that Healey’s point of power broker planning is synonymous with the traditional theory of power with its top-down nature. This view also considers sources of power as a lying between the traditional power theories where there can also be found the power of religion, law and force, which accompany Foucault’s view of power that considers knowledge as the main producer of power. That view of power (of a repressive government) cannot make us understand the nature of power in communicative planning. Foucault argues that: “If power is nothing but a repressive force, if power has nothing to do but just to say no, in this situation do you really think that it was compulsory for us to obey it?” (Foucault, Citation1985). The theme of this argument is that something else must apart from oppression lead people to compromise and adapt to the state of power. He argues in the first volume of “The history of sexuality” (1984) that while disciplinary practices in areas such as criminology and educational issues transforms man into an object or an identified issue, practices used in science related to sex transforms man into an identification agent which is in keeping with his status (Foucault, Citation1978). In Foucault’s view, this is the power/knowledge that produces the facts and single scientists are merely queues or bases where knowledge is generated (Foucault, Citation2012a). The idea of power/knowledge is something that can reveal the nature of communicative planning.

Foucault’s analysis is clearly based on this assumption coming from Nietzsche that knowledge has an inseparable connection with power networks (Ure & Testa, Citation2018). Power produces knowledge (And not just by promising and encouraging the production of knowledge, because knowledge serves power, or with the use of knowledge because of its usefulness), power and knowledge both imply the other. There is no power relationship which does not create a sphere of its own correlated knowledge and there is no knowledge in which the unit requires and does not bind power relations. As a result of what happens in communicative planning, it is not with the distribution of power, but indeed among the various players, the induction of knowledge and the production of the desire to know (Foucault, Citation1980). According to Foucault, power cannot be divided or enforced, but it can exist in space and the will to know can extend the range of power of each player (Foucault & Ewald, Citation2003). It may be argued that in practice the result is that both discourses—the re-distribution of power or expansion of the power range—is the same for the planning players, but one important difference separates these two views. That difference is that the first discourse, of distributing power, specifies the dependence of various actors on the government, meaning that it is the government which decides to choose communicative theory and legitimize relationships between different actors or, in other words, it decides whether or not to hear other parties’ voices. However, in the second discourse, power distribution from the upper levels of a hierarchy (governance) to the low levels of society (citizens) has been rejected and is instead based on that “the will to know enables and empowers them”. Power distribution somehow expresses a new way of planning to normalize society in way where public participation is obviously assumed. Whereas the flow of power relations in a network of human relationships and prior knowledge has been assumed to be normalized, so public participation, even in the best situation, cannot imply the expansion of power as long as it is subordinate to laws and or the desire of government. We then face a new form of domination whose ruler is uncertain because the deciding planning which should be participatory is the government and those who decide the direction of the plans are citizens and interest groups. It should be noted that the discussion is not between “good” or “bad” theories, but rather understanding the relationships of power which exist in communicative planning. In the end, we can say that communicative planning can increase the range of power of individuals along with creating knowledge and inducing it to various players and consequently reduce the role of government and the presence of governmentality in planning.

Additionally, hidden governmentality would be primarily revealed by investigating contemporary urbanism’s dialectics in terms of neoliberalism and socialization. The socialization, as a nonmarket cooperation between social actors, has been increasingly considerable in both production and reproduction in the long term. Since socialization has always been problematically related to private property and class discipline, it cannot be observed in politically progressive forms. There was a socialization growth in varied forms during the long boom, yet this intensified the classic crisis tendencies toward capitalism bringing about growing politicization. These tensions have been determined by neoliberalism by compelling unmediated value dealings and class discipline, as well as separating labor and capital and encouraging depoliticization. Anyway, this has adequately made inefficiencies and failure obvious for reproduction of the wage relation. Modified forms of plenty of long-term socializations could therefore be retained. In addition, cities have observed the development of new forms of urban socialization significantly. In this regard, Gough (Citation2002) reviewed the role of business organizations, industrial clusters, top–down mobilization of community and attempts at “joined–up” urban governance. Urban socialization under neoliberalism can be demonstrated by the declared goal of the current labor government in Britain in order to improve “joined-up government”, particularly in urban policy. As a consequence, the urban policy has put up with lack of coordination of policy for health, education, transport and so on, absence of congruence among various branches of the national and local state, and deficiency in partnership with organizations of civil society. Therefore, better “joined up” is needed for governmental partitions and their links with civil society. Thus, “social exclusion” can be alternative to poverty comprehensively in “social” and “cultural” as well as “economic” approaches, as long as “joined-up government” has been the core centralization of national plans for area regeneration. Thus, the state has seriously accepted socialization by bringing social processes into focus rather than independent actors. Neoliberalism can reasonably leave these fill gaps in socialization. Their politicization has mainly been hindered by the neoliberal context, so does any socialist potential particularly. In fact, internalization of neoliberal social relations and often deepened social segmentations is caused by the new forms of urban socialization. Therefore, the fundamental goals of neoliberalism can be paradoxically achieved better than “pure” neoliberalism itself. All the same, neoliberalism may often weaken these forms of socialization.

Contemporary urban class relations and forms of regulation thus reflect both opposition and mutual construction between neoliberal strategies and forms of socialization. In cases of socialization weakening by neoliberalism, it can be pointed to the fact that the persistent logic of socialization is reflected in the economic and social problems. The detected failures to satisfy the requirements of workers (Keil, Citation2002; Weber, Citation2002) and capital (Bluestone & Harrison, Citation2000; Jones & Ward, Citation2002; Martin, Citation1999) have been due to weakened nonmarket coordination in training, housing and transport areas. Todays’ political economy of cities entangles a complex interaction of neoliberal interventions, longstanding forms of socialization and new or revived forms of coordination maybe due to indwelling of socialization.

6. Discussion and conclusion

Power is present everywhere. The application of power has a wide span that influences all people and objects, controlling and leading the territory of contemporary urban space. Power can breakthrough all structures or displace differing values. The aim of this article is to interpret urban planning through the eyes of Foucault’s theory of power by surveying the urban planning theories that include participation (the presence of power, but not dominance) through the lens of power. A Foucauldian reading of urban planning demonstrates interesting and invisible points which show that power definitely exists in urban planning, but how does urban planning synthesize with power theory? This question cannot be answered definitively. The discourse of Foucault makes it quite difficult to define a new theory of planning. Nevertheless, the purpose of this article has not been to present a new theory of urban planning, but rather to consider the properties and characteristics of urban planning from the power point of view. To this end, there are two assumptions:

First, that planning is a game of power from the perspective of government to govern the city and its future development. In this way, planning normalizes Sujets libres and the subjugation of society as the government wants to control and lead society under its dominance by relying on planning tactics. In this assumption, different forms of planning derive from the power/knowledge cycle that the government utilizes to legitimize its power and expand the span of its dominance based on new theories.

Second, If we put aside the pessimistic view of planning, within the theory of power it can serve as an opportunity to resist against the government and egress subjugation through the context of democracy. Unlike the first assumption that places planning in an ominous position, this assumption considers planning a blessing. It presents an opportunity for those whose span of power is limited to harness external forces such as capital, idealism or governance. Planning then becomes a context for people and institutions to decide the future interaction of their city and with one another. Although there would be no balance of power among them, this forward movement represents both power and resistance. Regarding this second assumption, it is important to identify the characteristics of urban planning and the planner from the perspective of power. To consider these aspects, it is possible to use the essence of power from Foucault’s point of view to locate planning and planner in relation to power.

Power relations are moving, unfair and non-symmetric. We should not expect to find a sustainable logic for power or the possibility of power balance in planning. Therefore, planning cannot be universally theorized or defined as a power relation between urban actors—from the urban governor to non-government organizations and citizens. It is impossible to do so as they differ extremely from one context to another as well as over time. By changing the target, the power span of urban actors also changes. The planner in this view should accept the unfairness and non-symmetry of power in order to attempt to increase the span of power of weaker players by injecting knowledge. On the other hand, the planner must also prevent the formation of dominance in the process of planning.

On the other hand, since power is not an object, it cannot control a set of institutions. Thus, the aim of the planner is to discover it at first to see how it functions and for this reason should recognize and analyze the network of power relations. Each social institute has power and can assist in the niche and relation of that institute in the network of power relations. It should not be thought that the whole of power rests solely in the hands of the capitalist or government, but non-government organizations and minority groups hold power too. The recognition of origin and the way to apply power by weaker individuals or institutes can reveal the resistant solutions against dominancy and thus planning is a movement that works toward the balance between power and resistance among different urban actors, though no such balance may occur in actuality.

Moreover, power is not limited to political institutes and has a direct and creative role in social life. Power is multi-directional and acts from top-down as well as from bottom-up. The challenge of urban planning is not the choice between hierarchy or bottom-up power, but the adoption of chain strategies that induce resistance in groups with limited power against the dominancy of greater power. The form of power can be political, economic, human-friendly or naturalist. The planner must stand in front of these various forms of power that tend to dominate processes of planning, whether the form of power is economical like in the capitalism system or fights for the environment such as in the Green movement (Dark, Light, and Bright Greens contemporary environmentalists).

Foucault’s theory of power emphasizes that when disciplinary technologies create a permanent connection with the framework of a particular institute, they become more productive. Planning on behalf of the government should reside in the position of a specific institution. In the cycle of power/knowledge, the act of planning can reduce the role of government and lead to effective technological advantages based on generative power in fields of productive-economic, industrial and science that finally extend to the participation of different actors in urban planning (such as using modern technologies like virtual reality or new economic techniques like urban entrepreneurship). Ultimately, dominancy is not the essence of power. Dominancy exists, but power does not only exist in the hands of government but can also be imposed on governments. In the same way, the planner is under the pressure of different actors’ power. Nonetheless, it is important that the planner is not under the domination of a particular group. For this reason, the planner should facilitate the moving path of power/knowledge for divested groups by relying on the recognition of the network of power relations and change his or her role from law-maker to facilitator. From the other side, in power relations there is intent, but no subject. The urban planner must be aware of the values of society, but this knowledge should not be used for the modification of society, but to improve the value basis of the target society. In general, the values of society differ from each context or country to another and planning should not import value concepts from other societies into a target community, even if cultural exchange (until it normalizes) settles inside planning.

In conclusion, it can be said that power theory cannot be considered a pivot of planning and there is no guarantee that the trajectory of planning will not become one of power games of government systems. The purpose of this article is not to reject or recommend particular urban planning theories or prescribe the merging of power theory with urban planning theory, but rather attempts to make visible some aspects of urban planning that are not possible to view without using the lens of power theory. This research emphasizes the recognition of power from different angles and points of views of urban planning theories as it is not otherwise possible to obtain participation or empowerment within planning processes without understanding the network of power relations and its traps. Just when it would be certain that empowerment and public participation do not align with the power game of dominancy or government, the recognition of power relations and the solutions or proper reactions of weaker groups are sought out and revealed. Power theory also helps planning theory to appear as the understanding of the network of power relations between different actors and at the same time increases the complexity while non-generalizing planning and its naturally changing essence. Regarding this, can any planning theory serve as the major paradigm of our era? On the other hand, if we accept power theory, then the essence of planning theory is put into doubt by constantly challenging power criteria in a way that perhaps does not fully fit Foucault’s view. Additionally, if we put it aside, how then can we be assured that the government or other powerful economic forces sequester power without being noticed by planning knowledge and realizing that society is already in their hands?

Correction

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Seyed Navid Mashhadi Moghadam

Seyed Navid Mashhadi Moghadam (MSc) is a Ph.D. candidate at the Faculty of Art and Architecture at Tarbiat Modares University in Iran. His research focuses on social aspects and dynamics in power distribution between Citizens and Governance.

Mojtaba Rafieian

Mojtaba Rafieian is Associated Professor at the Faculty of Art and Architecture at Tarbiat Modares University in Iran. His research focuses on the governance of urban development, with a special interest in Urban Transformation.

Notes

1. Blueprint planning is a label for rational planning which refers to blue color of master plans papers which introduced by Sir John Herschel in 1842. Following the rise of empiricism during the industrial revolution, the rational planning movement (1890–1960) emphasized the improvement of the built environment based on key spatial factors. Examples of these factors include: exposure to direct sunlight, movement of vehicular traffic, standardized housing units, and proximity to green-space. To identify and design for these spatial factors, rational planning relied on a small group of highly specialized technicians, including architects, urban designers, and engineers. Other, less common, but nonetheless influential groups included governmental officials, private developers, and landscape architects. Through the strategies associated with these professions, the rational planning movement developed a collection of techniques for quantitative assessment, predictive modeling, and design. Due to the high level of training required to grasp these methods, however, rational planning fails to provide an avenue for public participation. Throughout both the United States and Europe, the rational planning movement declined in the later half of the twentieth century. Read more in:

References

- Beveridge, W. (2000). Social insurance and allied services. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 78, 847–17.

- Bluestone, B., & Harrison, B. (2000). Growing prosperity. New Yor+: Houghton mifflin.

- Clegg, S. R. (1989). Frameworks of power.

- Davidoff, P. (1965). Advocacy and pluralism in planning. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 31, 331–338. doi:10.1080/01944366508978187

- Deleuze, G. (1988). Foucault.

- Della Porta, D. (2006). Social movements, political violence, and the state: A comparative analysis of Italy and Germany.

- Dreyfus, H., & Rabinow, P. (1982). The subject and power. Michel Foucault: beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics

- Dreyfus, H. L., & Rabinow, P. (2014). Michel Foucault: Beyond structuralism and hermeneutics. Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

- Dryzek, J. S. (1994). Discursive democracy: Politics, policy, and political science. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Edwards, M. (2002). Public sector governance—Future issues for Australia. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 61, 51–61. doi:10.1111/ajpa.2002.61.issue-2

- Faludi, A. (2013). A reader in planning theory (Volume 5). Toronto: Elsevier.

- Fischer, F. (2000). Citizens, experts, and the environment: The politics of local knowledge. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Forester, J. (1988). Planning in the face of power. California: Univ of California Press.

- Foucault, M. (1978). The history of sexuality, volume I. New York, NY: Vintage.

- Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972–1977. New York, NY: Pantheon.

- Foucault, M. (1982). The body of the condemned. New York, NY: Arbor House.

- Foucault, M. (1985). Freiheit und Selbstsorge: Interview 1984 und Vorlesung 1982. Paris: Materialis-Verlag.

- Foucault, M. (1988). Technologies of the self. Technologies of the self: A seminar with Michel Foucault (pp. 16–49). Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

- Foucault, M. (1991). The Foucault effect: Studies in governmentality. Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

- Foucault, M. (2002). The birth of the clinic. London: Routledge.

- Foucault, M. (2012a). The archaeology of knowledge. New York, NY: Vintage.

- Foucault, M. (2012b). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. New York, NY: Vintage.

- Foucault, M. (2012c). The history of sexuality, vol. 2: The use of pleasure. New York, NY: Vintage.

- Foucault, M., & Ewald, F. (2003). “Society Must Be Defended”: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975–1976. London: Macmillan.

- Friedmann, J. (1973). Retracking America; A theory of transactive planning. Massachusetts: Anchor Press.

- Friedmann, J. (1987). Planning in the public domain: From knowledge to action. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Friedmann, J. (1992). Empowerment: The politics of alternative development. London: Blackwell.

- Friedmann, J. (1994). Planning education for the late twentieth century: An initial inquiry. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 14, 55–64. doi:10.1177/0739456X9401400106

- Gariépy, M. (1991). Toward a dual-influence system: Assessing the effects of public participation in environmental impact assessment for Hydro-Quebec projects. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 11, 353–374. doi:10.1016/0195-9255(91)90006-6

- Gaventa, J. (1982). Power and powerlessness: Quiescence and rebellion in an Appalachian valley. Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

- Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. California: Univ of California Press.

- Giddens, A. (1994). Beyond left and right: The future of radical politics. California: Stanford University Press.

- Giddens, A. (2013). The third way: The renewal of social democracy. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Gough, J. (2002). Neoliberalism and socialisation in the contemporary city: Opposites, complements and instabilities. Antipode, 34, 405–426. doi:10.1111/anti.2002.34.issue-3

- Habermas, J. (1987). The theory of communicative action (Vol. 2). Boston: Beacon.

- Hall, P. (1983). The Anglo-American connection: Rival rationalities in planning theory and practice, 1955–1980. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 10, 41–46. doi:10.1068/b100041

- Hall, P. (2014). Cities of tomorrow: An intellectual history of urban planning and design since 1880. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Hall, S. (2001). Foucault: Power, knowledge and discourse. Discourse Theory and Practice: A Reader, 72, 81.

- Healey, P. (1992). Planning through debate: The communicative turn in planning theory. Town Planning Review, 63, 143. doi:10.3828/tpr.63.2.422x602303814821

- Healey, P. (1996). The communicative turn in planning theory and its implications for spatial strategy formation. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 23, 217–234. doi:10.1068/b230217

- Healey, P. (1998). Building institutional capacity through collaborative approaches to urban planning. Environment and Planning A, 30, 1531–1546. doi:10.1068/a301531

- Heller, K. J. (1996). Power, subjectification and resistance in Foucault. SubStance, 25, 78–110. doi:10.2307/3685230

- Hillier, J. (1993). To boldly go where no planners have ever…. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 11, 89–113. doi:10.1068/d110089

- Hillier, J. (1995). The unwritten law of planning theory: Common sense. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 14, 292–296. doi:10.1177/0739456X9501400406

- Hillier, J. (2002). Shadows of power: An allegory of prudence in land-use planning. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Hudson, B. M., Galloway, T. D., & Kaufman, J. L. (1979). Comparison of current planning theories: Counterparts and contradictions. Journal of the American Planning Association, 45, 387–398. doi:10.1080/01944367908976980

- Jones, M., & Ward, K. (2002). Excavating the logic of British urban policy: Neoliberalism as the “crisis of crisis–Management”. Antipode, 34, 473–494. doi:10.1111/anti.2002.34.issue-3

- Keil, R. (2002). “Common–Sense” neoliberalism: Progressive conservative urbanism in Toronto, Canada. Antipode, 34, 578–601. doi:10.1111/anti.2002.34.issue-3

- Kiernan, M. J. (1983). Ideology, politics, and planning: Reflections on the theory and practice of urban planning. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 10, 71–87. doi:10.1068/b100071

- Knights, D., & Vurdubakis, T. (1994). Foucault, power, resistance and all that. London: Routledge.

- Lash, S. (1991). Foucault/Deleuze/Nietzsche. The Body: Social Process and Cultural Theory, 7, 256.

- Lemke, T. (2007). An indigestible meal? Foucault, governmentality and state theory. Distinktion: Scandinavian Journal of Social Theory, 8, 43–64. doi:10.1080/1600910X.2007.9672946

- Lemke, T. (2015). Foucault, governmentality, and critique. London: Routledge.

- Lindblom, C. E. (1959). The science of ”muddling through”. Public Administration Review, 19, 79–88. doi:10.2307/973677

- Mann, M. (1986). The sources of social power (Vol. 2). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. 1: 38.

- Mann, M. (1988). States, war and capitalism: Studies in political sociology. New York, NY: Basil Blackwell.

- Martin, R. L. (1999). Money and the space economy. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Matamoros, C. A., & Graham, D. (2018). Yellow Vests’: 1,400 arrests and 126 injuries in France as clashes continue. Retrieved from https://www.euronews.com/2018/12/08/paris-is-on-lockdown-as-france-braces-for-a-fourth-week-of-yellow-vest-protests

- Mazziotti, D. F. (1974). The underlying assumptions of advocacy planning: Pluralism and reform. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 40, 38–47. doi:10.1080/01944367408977445

- McDonald, G. T. (1989). Rural land use planning decisions by bargaining. Journal of Rural Studies, 5, 325–335. doi:10.1016/0743-0167(89)90059-4

- McLoughlin, J. B. (1969). Urban & regional planning: A systems approach. London: Faber and Faber.

- Miller, P., & Rose, N. (2017). Political power beyond the state: Problematics of government. In Foucault and law (pp. 191–224). London: Routledge.

- Njoh, A. J. (2009). Urban planning as a tool of power and social control in colonial Africa. Planning Perspectives, 24, 301–317. doi:10.1080/02665430902933960

- Paul, T. V., Ikenberry, G. J., & Hall, J. A. (2003). The nation-state in question. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Reddel, T. (2002). Beyond participation, hierarchies, management and markets:‘New’governance and place policies. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 61, 50–63. doi:10.1111/ajpa.2002.61.issue-1

- Ritzer, G. (1988). Sociological metatheory: A defense of a subfield by a delineation of its parameters. Sociological Theory, 6, 187–200. doi:10.2307/202115

- Rose, N. (2000). Community, citizenship, and the third way. American Behavioral Scientist, 43, 1395–1411. doi:10.1177/00027640021955955

- Taylor, N. (1998). Urban planning theory since 1945. London: SAGE Publications.

- Teisman, G. R., & Klijn, E. H. (2002). Partnership arrangements: Governmental rhetoric or governance scheme? Public Administration Review, 62, 197–205. doi:10.1111/0033-3352.00170

- Ure, M., & Testa, F. (2018). Foucault and Nietzsche. In Foucault and Nietzsche: A critical encounter (pp. 127). London: Bloomsbury Academic

- Walzer, M. (1986). The politics of Michel Foucault. New York, NY: Blackwell.

- Weber, R. (2002). Extracting value from the city: Neoliberalism and urban redevelopment. Antipode, 34, 519–540. doi:10.1111/anti.2002.34.issue-3

- Winslow, E. M. (1948). The pattern of imperialism: A study in the theories of power. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Yeoh, B. S. (1998). Contesting space: Power relations and the urban built environment in colonial Singapore. Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society (pp. 71-80). Singapore: Singapore University Press.