Abstract

In this article, we have focused on the narrative features and cinematic techniques of Bharati Mukherjee’s short story “The Management of Grief” to examine the construction of identity in “the third space” in the age of immigration. The narrator-focalizer, Shaila Bhave, who has just lost her husband and two sons in the terrorist attack on the Air India, tells her story in the form of a diary with each part written at a distinct moment in time; as a result, the narrating “I” of each section is different from other parts, providing an opportunity for self-improvement. Shaila’s perspective, however, is not the only one in the story and irreconcilable perspectives and worldviews are revealed through dialogues. These perspectives and the dialogic nature of the story can help readers discern three governing chronotopes (time-space), that is, the chronotope of homeland, the host country and the third space, typical of most diasporic narratives. Analysis of the chronotopes and the cinematic features of the story would enhance one’s understanding of Shaila’s quest for identity and her maturation from a naive self-confident person to someone who is aware of the instability of her identity in the third space. Mukherjee’s dialogic story, then, deftly throws into high relief the dialogic nature of human identity, offering “dialogue” with others and with one’s selves as a way of “managing” humanity’s “grief.”

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Today, immigration, transnational and transcultural relationships comprise our reality. The culture and identity of the people living in diasporic communities, therefore, are of interest to both critics and writers. Bharati Mukherjee, as a writer of the Indian diaspora, in her fiction, in general, and in “The Management of Grief,” in particular, is concerned with these borderline identities. In this paper, there is an attempt to analyze such hybrid identities according to Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of Chronotope, an aesthetic way of presenting human beings in relation to their temporal and spatial world. Immigrants, living in diaspora, are actually living in the third space where they create a new identity and a new culture for themselves, separate and different from the culture of the homeland and that of the host country. Thus, Mukherjee’s story sheds light on one of the most pressing issues of our time.

[T]he fundamental liberation of cultural-semantic and emotional intentions from the hegemony of a single and unitary language, … is possible only for a consciousness organically participating in the universum of mutually illuminating languages. (Bakhtin, Citation1981, p. 367)

1. Introduction: Bakhtin’s chronotope and Mukherjee’s home

For Bakhtin, social life is dialogical, or multi-vocal, involving two or more voices. Dialogue begins with the encounter of self and other and is responsible for identity formation. That is, the self is constructed in dialogue with the other, so dialogue is the process of becoming who we are. It is a system of languages that mutually and ideologically “illuminate” one another (Bakhtin, Citation1981, p. 367). It contains both centripetal forces of unity (seeking commonality) and centrifugal forces of difference (asserting separate identity). Bakhtin’s focus is not on sharp dualistic opposites, but on “the ongoing complexities of how words, and the identities that emerge from them, have been partially shared in the past and will continue to be shared into the future” (Reid, Citation2013, p. 75). The tension arising from negotiation between different voices constitutes the “deep structure” of all human experiences. In other words, there is no one truth, one final word, but always dialogue and negotiation since conflicting tendencies are always multiple, varied and changing within the context of the moment. Bakhtin’s concept of “hybridity” refers to this ongoing negotiation among diverse voices. In hybridization, “only one language is actually present in the utterance, but it is rendered in the light of another language” (Bakhtin, Citation1981, p. 362). Hence, novel, Bakhtin’s celebratory genre, becomes “a hybrid contested site of identity, where many voices destabilize unitary or authoritative language” (Mabardi, Citation2000, p. 5).

Hybridity also implies that there can be no pure word, independent of context. Every dialogue, for Bakhtin, is performed in the context of a specific and unique time (chronos) and place (topos), which he calls its “chronotope.” In devising the concept of chronotope, Bakhtin has been under the influence of Einstein, who believes that an event is always a “dialogic unit” in so far as it is “a co-relation”: something happens only when something else reveals a change in time and space (Holquist, Citation2002, p.113). Accordingly, Bakhtin “roots the essence of things in relationships rather than in fixed qualities and tends to discuss chronotopes usually in the plural and in relationship” (Lawson, Citation2011, p. 388).

Chronotope is a term conceptualizing an aesthetic way of presenting human beings in relation to their temporal and spatial world. It is “a way of comprehending human life as materially and simultaneously present within a physical-geographical space and a specific point of historical time” (Morris, Citation1994, p.180). Discerning the chronotope of a narrative is of crucial importance since “every entry into the sphere of meanings is accomplished only through the gates of the chronotope” (Bakhtin, Citation1981, p. 258). Accordingly, “all the novel’s abstract elements—philosophical and social generalizations, ideas, analyses of cause and effect, gravitate toward the chronotope and through it take on flesh and blood” (Bakhtin, Citation1981, p. 250). The chronotope of a fictional narrative situates it in its historical time and mirrors the chronotope of the real world (Bakhtin, Citation1981, p. 253).

The reality of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the age of migration, is the huge movement across the globe, and it is best represented in the immigration literature. Esther Peeren (Citation2007), using Louis Althusser’s model of ideology, explains the chronotope’s function as “an ideology of time-space that interpellates individuals as subjects into collective space and into collective time through specific spatial and temporal norms” (p. 71). For the immigrants, who negotiate past, present, and future at different spaces while living in diasporic communities, this interpellation is tripled: diasporic subjects are interpellated by more than one chronotope simultaneously. They are subjected by home chronotope, host chronotope and the third space chronotope of the journey between these two, which creates the hybrid identity. These chronotopes are considered as the “organizing centers,” places where “the knots of narrative are tied and untied” (Bakhtin, Citation1981, p. 250).

Generally, immigrant literature challenges and questions the possibility of such negotiations between developed countries, mostly America, and immigrants of the developing countries. Writers of (American) immigrant literature ask whether America is really the land of freedom and a promise of a better life or it represents a mirage luring enthusiastic people of the developing countries. They wonder whether America is a place where the nation delivers the promises of the American Dream to all its citizens, regardless of their nationality. These questions get even more difficult to answer at the time of Donald Trump’s presidency. The Trump administration’s immigration policy “cast immigrants and refugees as threats to the United States,” as Kristin E. Heyer claims (Citation2018, p.146). His anti-immigrant sentiment reflected in the most popular chant at his rallies, “Build the wall!,” his policy of securing America’s borders against the strangers, deporting undocumented immigrants and separating children from their families at the borders have “fanned the flames of nationalism, sown fear in immigrant communities, and eroded civic life” (Heyer, Citation2018, p. 147). Therefore, current readers of immigrant literature would look anew at this genre and wonder how immigrant characters would feel and act today among all the Americans who have elected Trump and supported his immigration policy.

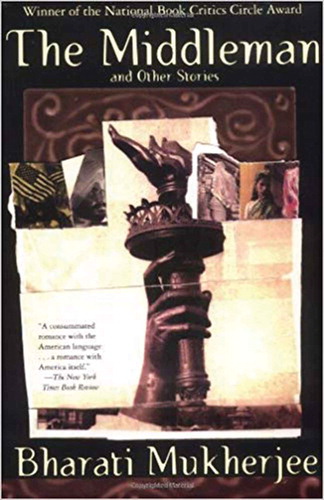

In the field of Asian-American literature, the fiction of Bharati Mukherjee, an Indian born American writer, invites more critical reading. Mukherjee is one of the most contested and, at the same time, acclaimed Indian-American writer. Her stories have found their ways into anthologies and won her literary awards. Her fiction, in general, is concerned with the experience of non-Westerners, particularly (female) Indian immigrants, who are fluttering between different times and spaces in search of a better home. The present article is an attempt to explore the narrative features of Mukherjee’s short story “The Management of Grief,” published in her 1988 collection of short stories (Mukherjee, Citation2002a), The Middleman and Other Stories, to see how and to what extent the play of chronotopes of homeland, host country and the third space could shed light on the main character of the story and distinguish her from Mukherjee’s other female characters.

In a work of art, beside dialogic relationships among diverse perspectives and chronotopes, it is possible to discern a dialogue between the text and the paratext. The image of the Statue of Liberty on the book cover of The Middleman is the first thing that attracts the readers’ attention. Readers, who are familiar with the mainstream/critical American fiction, like American Pastoral, Invisible Man, The Great Gatsby, The Death of a Salesman and many more, most probably would think that the image is ironic, especially by knowing that the book has been written by an immigrant. However, Mukherjee’s fiction and her interviews reveal that she is a believer in the American Dream and an admirer of America, as a land open to the newcomers, either legal or illegal. Her fiction mostly narrates the story of Indian women who, liberated from the manacles of constrictive patriarchal society, are able to refashion their lives and get an inner sense of freedom in America. She has distinguished herself from other Asian-American writers by avoiding postcolonial nostalgia, displacement and loss present in expatriate writings. In an interview conducted by Vrinda Nabar in The Times of India, she contends: “An expatriate works very hard to artificially hang on to the past. I say let the old self die, if it must, if the new self must be born” (Mukherjee, Citation1995, p. 17). Instead of letting the mainstream culture marginalize her and her characters by hyphenating their national identity, she focuses on the immigrants’ empowerment, self-esteem, and their resourcefulness, necessary for a triumphant survival in America.

Mukherjee’s revisionary cultural politics regarding diaspora has aroused considerable critical interest. One of the chief criticisms made against Mukherjee, especially her novel Jasmine, is her too optimistic view of American society, where all sorts of determined and willful immigrants, legal or illegal, are able to succeed (Stoneham, Citation1996). These critics believe that Mukherjee has been oblivious to the role of race, class and gender in the identity formation of the third world immigrants in America (Knippling, Citation1993; Roy, Citation1993). Some other critics, by referring to Mukherjee’s privileged position as an upper-class, educated migrant, highlight her failure in representing Indian-troubled history accurately and do not regard her as an appropriate spokesperson for Indian culture (Banerjee, Citation1993; Tandon, Citation2004). We think Mukherjee’s view of America as well as Canada is flawed because of her “one-dimensional” approach to conceptualizing multiculturalism, to use Hartmann’s and Gerteis’ term (qtd. in Wong, Citation2015, p. 70). In this “narrow and binary approach,” there is either assimilation or fragmented multiculturalism. In her critique of Canadian multiculturalism, Mukherjee is in tune with sociologists like John Porter in The Vertical Mosaic and Reginald Bibby in Mosaic Madness: Pluralism Without a Cause), who criticize Canadian multiculturalism as “mosaic,” “fragmented,” “divisive,“ and “a barrier to the development of a unified Canadian identity” (Wong, Citation2015, p. 74). For them, assimilation is the only way to overcome Canadian disunity and ethnic marginalization. Hence, it is only by resettling in America in 1981 that Mukherjee feels that at last she has been allowed to merge into the melting pot of American culture. It is in America that she thinks she has turned into an immigrant as opposed to her previous state of expatriate in Canada. Canada and America in all Mukherjee’s works are intertwined. Her experience and mood in either of these countries have always influenced her writing. Through various forums, Mukherjee has announced her experience of racism in Canada, which made her feel different, inferior and like an outsider while she held Canadian citizenship. To describe her sense of isolation, aloofness, and dislocation in this “unhoused” phase of her life in her memoirs, Days and Nights in Calcutta (Citation1977), she asserts that the anxiety was derived from “the absolute impossibility of ever having a home” (p. 287). Moreover, in the essay, “An Invisible Woman” (Citation1981), she elaborates on her rootlessness and despair in Canada on account of her paradoxical position of being both too visible and too invisible. She was invisible as a writer, but her color made her too visible as a non-white immigrant in Canada. Thus, despite being set in America, Mukherjee’s first two novels, The Tiger’s Daughter (Citation1971) and Wife (Citation1975), which were written in Canada, acutely reflect her mood in Canada by relating stories of Indian expatriates described as “lost souls, put upon and pathetic […] adrift in the new world, wondering if they would ever belong” (Mukherjee, Citation1985, p. xiii—iv).

Transformation to an exuberant writer and attempts at “rehousement” occurred with the act of immigration to America, which “represented a kind of glitziness … a chance for romantic reincarnation” for Mukherjee (Mukherjee, Citation1990a, p. 11). It seems that in the United States, she has been able to overcome her problem of homelessness by “adopt[ing] this country as my home. I view myself as an American author in the tradition of other American authors whose ancestors arrived at Ellis Island” (emphasis added, Mukherjee, Citation1989a, p. 650). For her, being an American is “a quality of mind and desire. It means that you can be yourself, not what you were fated to be” (Mukherjee, Citation1989b, p. 22). However, her view of America in her early period, like that of Canada, seems to be narrow and one-dimensional. It seems that she has been ignorant of the diversity of multiple narratives of American identity. Shannon Latkin Anderson (Citation2016) defines American identity in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries in the light of assimilation and immigration. She contends that “versions of Anglo-conformity (Anglo-Protestantism), the melting pot, and cultural pluralism (multiculturalism or the mosaic)” have long been present simultaneously in America, and the emphasis shifted from one to the other “in part because of structural factors like immigration rates and foreign affairs” (p. 218). During the same period that Mukherjee celebrates American tolerance for the other, that is, during the 1980s, Anderson reveals how Americans’ awareness of the growing number of immigrants with non-European origins led to a backlash against immigrants. During this time,

increasingly, proposals seeking to limit the increasing numbers of Latinos and Asians entering the country were put forward. Lawmakers, the labor movement, some African-American groups, some environmentalists, and many ordinary Americans (black, white, rich, poor) decried the presence of these newcomers, arguing that they were taking jobs away from rightful American workers. (Citation2016, p. 156)

Ignorant of other narratives of America, in contrast with bitter stories of her early works, Mukherjee tells the story of brave, self-assertive, determined immigrant survivors who, lured by the American dream, conquer the unknown world replete with violence and brutality. They undergo deep painful emotional, mental, and physical transformation while they rid themselves of old social and traditional mores to merge with the mainstream culture in America. Jasmine (Mukherjee, Citation1989c) is the prototypical novel of this phase in Mukherjee’s career. Jasmine is a young semiliterate village girl who finds her way from Punjab into Florida, New York, Iowa and finally California through many transformations—Jyoti, Jasmine, Jazzy, Jase and Jane. In Mukherjee’s sense of Americanness, Jasmine becomes a true American woman since she is determined to “reposition the stars” (Mukherjee, Citation1989c, p. 240) and “remake” herself by “murder[ing]” her old self and being reborn “in the images of dreams” (Mukherjee, Citation1989c, p. 29). Faithful to American dream, Jasmine feels that she has made the right choice by choosing “the promise of Americas” as opposed to “the old world dutifulness” (Mukherjee, Citation1989c, p. 240) when she leaves her crippled partner, Bud, and accompanies her former lover, Taylor, to New York.

Sharmani Gabriel argues against Mukherjee’s easy assimilation, reminding us that Mukherjee prefers the term “fusion” over “assimilation” (Citation1999, p. 75). She contends that Mukherjee’s assimilation does not leave “unproblematized the meaning of home” (Citation1999, p. 75). Although Mukherjee’s immigrants are willing to be changed into something new by discarding nostalgia and accepting the challenges of constructing an alternative narrative of home, Gabriel continues, their assimilation is not uncritical of the dominant white American identity (Citation1999, p. 76). As Mukherjee claims, while America changes all those who make their home in it, America itself is being transformed: “I’m saying we haven’t come to accommodate or to mimic; we have changed ourselves, but we have also come to change you” (Mukherjee, Citation1990b, p. 9). However, what the reader witnesses in this novel is not so much an American change as Jasmine’s transformation. Although she draws upon Hindu concepts of Sati and reincarnation, which empowers her to face the brutality of the American life, she turns out to be an “Americanized, commodified, consumerist, professional caregiver” (Singh, Citation2010, p. 84). Taylor’s consumerist habit of returning the defective products appeals to Jasmine who is after an easy way out of a life with a crippled man (Singh, Citation2010, p. 83).

In Leave It to Me (Citation1997), the story of self-construction takes another route. Debby, as an adopted child of an Italian-American family, feels the urge of searching for her bio-parents. Unlike Jasmine, she has already had an American identity and looks into her Indian past from the perspective of America. Her mother is revealed to be a Berkeley educated American hippie who deserted her child on a love-and-peace flower trip to India. Knowing that her mother might be in San Francisco, she leaves New York for San Francisco and begins a series of transformations, changing names and leaving lovers. San Francisco, as a transnational space peopled with ex-hippies in pursuit of money, drug dealers, and immigrants from all parts of the world, appeals to Debby. She enjoys the new age of “love and profit, charity and sex” (Mukherjee, Citation1998, p. 69). This space is liberating for her: “I felt free; I was free” (Mukherjee, Citation1998, p. 69); free to perform a variety of identities: the hippie, the lover, the arsonist and the killer. Debby calls this multiethnic place Asia (Mukherjee, Citation1998, p. 67). However, her concept of Asia is romanticized and stereotypical as she fancies about Frankie’s father’s life in hotels and nightclubs in imaginary Singapores and Shanghais, places that are “hot, loud, smoky, full of cheats, drugs and whores; the nightclubs were always places of viciousness and degradation and carnality” (Mukherjee, Citation1998, 27). Though this hybrid space suggests the ways immigrants have transformed America, the culture presented here is much closer to the easy-going contemporary American street culture than the traditional Indian one. Moreover, Debby’s revenge on his father, an Indian-Pakistani guru-turned-Killer, may symbolize Debby’s attempt at ignoring her Indian side despite her cherishing of the free-floating identity of the diaspora. In addition, Manju Jaidka (Citation1999) believes that the use of Indian mythology in this American context is problematic since Debby’s “total lack of spiritual depth, her very pragmatic/materialistic approach to life, and her many liaisons with the men who come her way” prevents any comparison between her and the Goddess Kali/Devi, a warrior goddess of Indian mythology, who is praised for her strength and moral uprightness (p. 204). Hence, Debby is more representative of a young self-assertive American, who imagines to have been adapted by America. As Nyman (Citation2004) points out: “In the end it is only the imagination of nation, the mythical America with transformative powers, that may take over the role of the home” (p. 415).

It must be pointed out that with each reincarnation derived from Hindu religion, both Jasmine and Debby create new certainties out of loss, get closer to their new American identity and further away from the old world. Nevertheless, another shift in Mukherjee’s work is discernible by the publication of Desirable Daughters (Citation2002b) and The Tree Bride (Citation2004). Unlike Jasmine and Leave It to Me, in which native culture and homeland were represented as something to be rejected, these novels encourage a return to tradition and a search for one’s roots, as symbolized in the image of the roots of the tree bride. Tara, the narrator of these novels, is a daughter of a rich Brahmin Bengali family who entered the USA in an arranged marriage. Though at the pinnacle of American success, in an act of self-fulfillment and against the rules of her traditional culture, she gets divorced from her Silicon-Valley millionaire husband, Bish, and takes a foreign lover. However, a terrorist attack on her house in California sets her on a journey back to India, where she tries to find out about her roots by unraveling threads of Bengali history related to her family and the tree bride, as her ancestor. As Katherine Miller (Citation2004) maintains, these novels suggest that “one’s birthplace does form one’s identity, that identity performance can only be enacted within the limitations of an assigned space” (p. 17). “The return to her roots,” she continues, “along with Tara’s re-emerging relationship with Bish, calls into question the very notion of a performative identity, [which] … remains firmly constrained within the ideological determinants of home and community” (p. 17).

In contrast with the aforementioned narratives, “The Management of Greif” represents a female character who becomes aware of her hybrid identity in the third space. Without being successful in assimilating into the host country or returning home, Shaila Bhave becomes confident about her uncertain and unstable identity in the liminal space. This story situates characters with different nationalities, Indian, Canadian, and Irish, in a kind of dialogic relationship. Having in mind that “The Management of Greif” is written in America and all other stories in Middleman are set in America, we should see these people also in dialogue with Americans. In fact, Mukherjee’s positive attitude toward America makes it possible for Shaila to have a hybrid identity in Canada. Concerned with the concept of hybridity in Middleman, Andrew Hammond (Citation2007) believes that Mukherjee’s treatment of cross-cultural encounter is complex and its complexity is evidenced by “the sheer heterogeneity of forces influencing the perspectives of the characters, the cultural encounter refracted through a tortuous negotiation of tradition, modernity, nationhood and class as well as the more evident identifications with ‘ethnicity, postcoloniality, gender and migrancy’” (p. 194). He argues that in these stories Mukherjee has painted all sorts of attitudes towards cultural interactions: “racism, … the assimilation of dominant ideology, … a retention of traditional loyalties, … [and] the hybrid model, with an acceptance of diversity and a resolution of conflict via the recognition of duality within self and other” (p. 194). He continues that although it is in hybridity that Mukherjee finds hope, this ideal state in intercultural relationships is “constantly under threat from the forces of essentialisation” and is “achieved with extreme difficulty” (p. 195).

For the concept of hybridity in “The Management of Grief,” in this paper, we argue that it takes place gradually and with efforts made by Shaila while she is reinventing herself after the tragedy of Air India. By analyzing the narrative structure of this story through Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of chronotope and Hamid Nafisy’s analysis of diasporic films, it is suggested, we can go beyond solely discussing the theory of hybridity and instead show how it is achieved through cinematic narrative techniques.

2. Dialogic structure of “The Management of Grief”

This short story narrates a real terrorist attack on the Air India in 1985, killing all 329 people on board. This catastrophe is one of the worst air disasters of any kind by a number of fatalities. Most passengers on board were Indian-Canadians who were traveling from Canada to India. Sikh militants, who were fighting for their independence back in India, were accused of being responsible for the disaster. Mukeherjee had previously investigated the disaster together with her husband, Clarke Blaise, through interviewing with the bereaved families and published the research in the non-fictional The Sorrow and The Terror in 1987. The unspeakable grief of the relatives and the image of the bodies torn and scattered in the Atlantic obliged her to write a story about this disaster. “The Management of Grief,” thus, reflects the grief shared by the remaining relatives and at the same time narrates Shaila’s quest for identity in the third space after losing her husband and two sons in the disaster.

The narrative begins in the middle of a crisis when something strange and unexpected has happened about which the narrator herself does not have enough information: “A woman I don’t know is boiling tea the Indian way in my kitchen. There are a lot of women I don’t know in my kitchen, whispering and moving tactfully” (Grief, p. 612). The present tense and the indefinite article “a” reflect the narrator’s current anxiety, estrangement and confusion right at the beginning. References to the central crisis of the story are made in a way which increases suspense and confusion: “They’re acting evasive, Ma. They’re saying it could be an accident or a terrorist bomb” (Grief, p. 612). An utter confusion fills a few more paragraphs by introducing different stories about what has happened: Space debris? Russian laser? Accident? Hijacking? Terrorist bomb? This plane crash which little by little is known to be a terrorist attack becomes the main object of focalization, that is, different perspectives and worldviews are revealed through the presentation of different perceptions of the catastrophe. In other words, different ways of “grieving” for the loss of loved ones and dealing with this disaster represent diverse worldviews held by different characters in the story.

Belief in individually constructed reality has led Ansgar Nunning (Citation2001) to focus on the idea of “perspective” in fictional narratives. In the same way that individuals in the real-life construct their own subjective perspectives and worldviews (regardless of the influence of ideological discourses on one’s way of constructing worldviews), characters and narrators “shape the subjective world-models that constitute their individual perspectives” (p. 209). According to Pfister, “the level of advance information the figure has access to” as well as “psychological dispositions” and “ideological orientation” of a character define the character’s perspective (as cited in Nunning, Citation2001, p. 210). Nunning (Citation2001) assumes an individual perspective for both characters and narrators and explains that it is up to the reader to infer and construct perspectives of various characters on the basis of what the narrator tells him/her about the character’s physical, verbal and mental acts. The reader can also deduce the narrator-perspective from what he/she says and does. Auto-diegetic narratives usually involve two main perspectives: the narrator-perspective representing the private domain of the narrating “I” and the character-perspective, namely, the perspective of the experiencing “I” which in retrospective narration is embedded in the narrator-perspective (p. 214, 218).

“The Management of Grief” consists of several parts separated by three asterisks which resemble different pages of a diary. The time duration varies from one part to the other: the first part which introduces the crisis is told in minute details and covers the span of few hours while other parts move quickly and one covers almost six months. Each part is limited to the knowledge of the narrator about events and other characters at a specific time; as a result, the information varies from one part to the other which emphasizes the difference between the narrating “I” of each part. For example, in one part, Shaila writes that Pam wants to open a yoga-cum-aerobics studio in Hollywood with her share of the insurance money, but in the final part when she has gained more information about Pam she knows that Pam is in Vancouver and works in a department store (Greif, p. 619, 622). Therefore, like a diary, each part has been written after the passage of some time and not written retrospectively at once from beginning to end. Consequently, the narrating “I” of each section is different from the narrator of other parts which makes it possible for the narrator to develop and mature over time. Moreover, each narrator-perspective embodies a character-perspective of the experiencing “I” since the narrator in each part remembers what the narrating “I” knew, experienced, thought and felt at a specific time.

Shaila, as the main focal character, has access to her own feelings and thoughts and perceives them from within; however, this accessibility does not guarantee comprehension. After the disaster, she is too confused to understand her calm behavior. She wonders if “pills alone explain this calm. Not peace, just a deadening quiet” (Greif, p. 612). She feels “repressed,” “tensed, ready to scream” (Greif, p. 612), but she remains silent, controlled and detached from the crowd of neighbors in her house. She does not know why “this terrible calm will not go away” (Greif, p. 614). Shaila’s behavior also becomes the object of focalization for others, who perceive her calmness as strength. She is introduced as “the strongest person of all, a pillar” to Judith Templeton, an appointee of the provincial government. As the auto-diegetic narrator, through interior monologues, Shaila reveals the confusion she feels. Although she seems calm, she wishes she “could scream, starve, walk into Lake Ontario, jump from a bridge”; she does not see herself as a model and deep down she knows other Indians, who have also lost loved ones in the plane crash, would regard her behavior as “odd and bad” (Greif, p. 614).

Besides her own thoughts and emotions, Shaila has access to other characters from without. By presenting what she perceives from their appearances and their actions as well as reporting directly their dialogues, she helps readers construct the characters’ perspectives and worldviews. Judith Templeton is a character who stands out as an icon for the white Canadian people and government as well as a stereotype of Western rationality and practicality. Judith’s characterization is shaped both by what Shaila can perceive from her appearance and what Judith herself says in her dialogues. Shaila represents her as a typical Western businesswoman, wearing a blue suit with a tie and holding a new leather briefcase. As a social worker, Judith tries to help “relatives” accept the disaster and get over their grief in order to be able to continue to face challenges in rebuilding their lives. She intends to help “hysterical” widows, depressed widowers and old people, both as a government agent and as a human being, who “presume[es] the equal human worth of the Indian bereaved” (Bowen, Citation1997, p. 50). As Shaila points out, Judith is very responsible and she “has done impressive work,” regarding Indian “relatives” (Greif, p. 619). However, despite her awareness of “the complications of culture, language and customs” and her desire to have “the right human touch” (Greif, p. 619) with Shaila’s help, Judith is unable to cross the cultural barriers. She deals with all accident victims, regardless of their cultural differences, with the same method based on her “textbook on grief management,” which describes an orderly staged process of “rejection, depression, acceptance, reconstruction” (Greif, p. 619).

Thus, the way Judith believes people should cope with tragedies is based on her textbooks, providing practical and rational solutions for everyday problems, such as money, home facilities and social services. She is so walled within her own perspective that cannot see other people may have other ways of coping with their grief. Although she seems to be benevolent, she shares the Eurocentric worldview of Westerners who believe in their own civilization as the only worthy way of life, prompting them to educate and civilize others whose traditions appear wrong and ignorant. Judith sees the old Sikh couple, who refuse to sign the legal documents, as “stubborn and ignorant” (Greif, p. 621); she thinks “they fear that anything they sign or any money they receive will end the company’s or the country’s obligations to them” (Greif, p. 620) while she does not understand that signing the papers means giving up hope for the return of their sons. She cannot comprehend what they mean when the old couple talk about the return of their sons since she does not understand “man alone does not decide these things [life and death]” (Greif, p. 621) and cannot realize losing electricity, telephone, gas, water and place means nothing for the people who believe that “God will provide, not government” (Greif, p. 621).

Shaila’s interaction with other members of the Indian community in Canada represents other ways of dealing with grief. Kusum, who has lost both her husband and her daughter in the plane crash, questions God’s justice; however, she is religious enough to consult with her swami and accepts his teachings about fate and afterlife. Following her swami’s advice, she pursues inner peace and is able to see her husband and hear her daughter singing again. Shaila respects Kusum’s way of dealing with her grief. When Kusum writes that in one of her pilgrimage, “she heard a young girl’s voice, singing one of her daughter’s favorite bhajans, … an exact replica of her daughter, … [who] cried out, ‘Ma!’ and ran away,” Shaila does not think it is stupid and “only env[ies] her” (Greif, p. 622). In another perspective, Dr. Ranganathan, an electrical engineer, has ambivalent attitudes towards grief. On the one hand, he has a “scientific perspective” with an “orderly mind, [which] holds no terror,” as Shaila perceives; on the other, he has “not surrendered hope” despite identifying the bodies of his wife and three of his children (Greif, p. 622). He believes that “it’s a parent’s duty to hope,” which kindles sparks of hope in Shaila’s mind, reasoning that since her son was a great swimmer, he might have been able to save both himself and his brother and be alive in one of the islets. In addition, through retrospection, Shaila contemplates about her grandmother’s and her parents’ perspectives on grief. Her grandmother, daughter of a rich zemindar, stuck to the “Vedic rituals”: she shaved her head, slept in a hut and took her food with the servants when she was widowed at sixteen. Her grief over her husband’s death ruined her and made her unable to take care of her child. Conversely, Shaila’s mother “grew up a rationalist [and] abhor[s] mindless mortification” (Greif, p. 618). Here, the object of focalization moves again and Shaila perceives the Irish outward behavior. She concludes that the Irish people, contrary to the Canadians, are more sympathetic towards the foreigners: “there’s been an article about it in the local papers. When you see an Indian person, it says, please give him or her flowers” (Greif, p. 616). She believes that “the Irish are not shy” since “they rush to me and give me hugs and some are crying. I cannot imagine reactions like that on the streets of Toronto. Just strangers, and I am touched. Some carry flowers with them and give them to any Indian they see” (Greif, p. 617).

Although this story is narrated by an auto-diegetic narrator, who runs the risk of making partial, biased and even distorted narrative as a result of her cognitive limitations, the way different characters are filtered through Shaila’s consciousness is supported by and is compatible to a great degree with how they act and talk. For example, when she represents the Irish as more sympathetic and more understanding than the Canadians, the reader is provided with some examples of the narrator’s emotional contact with the Irish people, how they hug, cry and give the “relatives” flowers. On the other hand, Judith’s insensitivity revealed through her insistence on Shaila’s help with the Sikh couple while knowing that her family had been killed most probably by a group of radical Sikh, as well as her self-righteousness and her pushy attitude to fit all victims into her rigid, inflexible, bookish categories, together with the Canadian Government’s evasive behavior and reluctance to accept the terrorist attack, all indicate that Shaila’s narrative about Canada is a comparatively reliable account.

Moreover, in this story, there is no dominant perspective to be able to remove other perspectives or reduce them to one unified worldview. All perspectives, whether rational and practical, spiritual and supernatural, hopeful or denying live side by side and the narrator’s perspective negotiates among them without superseding or rejecting any of them. In this way, the narrator’s perspective has no hierarchal value and is treated as one of the character-perspectives. The relationship between these character-perspectives and the narrator-perspective form a pattern called “perspective structure,” which becomes more complex and more dialogic with the increase in the number of perspectives and with the greater “spectrum of social, moral and or ideological differences” among various character-perspectives (Nunning, Citation2001, p. 215). Therefore, the difference in age (Shaila’s grandmother and her parents or Kusum and her daughter, Pam), gender (widows and widowers) and race (Indian, Canadian, Irish) represent a plurality of conflicting moral and ideological stances in the dialogic perspective structure of “The Management of Grief.” These different ideological perspectives in the world of narration resemble the conflicting and discrepant worldviews present in our contemporary globalized world where massive immigration and movement around the globe have forced people with diverse cultural backgrounds live together. These opposing voices are bound with specific time and space which refer to the three negotiating chronotopes of the homeland, the host country and the third space.

3. Chronotopes of the homeland and the host country

Analyzing accented films, that is to say, exilic and diasporic films produced in the interstices of social formations and cinematic practices, Hamid Naficy (Citation2001) points out that primarily the “utopian prelapserian chronotope of the homeland” is expressed in the homeland’s “open chronotope,” namely, “its nature, landscape, landmarks, and ancient monuments and in certain privileged renditions of house and home” (p.152). Spatially, the open form is represented in a mise-en-scene that favors “external locations and open settings and landscapes, bright natural lighting, and mobile and wandering diegetic characters”; temporally, the open films are infused with structures of feeling that favor “continuity, introspection, and retrospection. The present is often experienced retroactively by means of a nostalgically reconstructed past or a lost Eden” (Naficy, Citation2001, p. 153). The host country when associated with dystopic images, contrastingly, is expressed in the “closed chronotopes of imprisonment and panic” (Naficy, Citation2001, p. 153). The spatial aspect of the closed-form in the mise-en-scene consists of interior locations and closed settings, such as prisons and crowded living areas, poor lighting that creates a mood of constriction and claustrophobia, and characters who are restricted in their movements and perspective by spatial barriers. The closed temporal form is represented by panic and fear narratives, a form of temporal claustrophobia, in which the plot centers on pursuit, entrapment, and escape (Naficy, Citation2001, p. 153).

In this story, different sections of the diary with emphasis on spatial and temporal details of each setting move in front of one’s eyes like a film. Back in India, after mourning ceremonies, Shaila and her family travel to “hill stations and to beach resorts … play contract bridge in dusty gymkhana clubs … ride stubby ponies up crumbly mountain trails”; they participate in tea dances and “hit the holy spots” (Greif, p. 618). She goes to an abandoned temple in a Himalayan village and is able to connect with her husband spiritually in an altar room. Therefore, India as Shaila’s homeland is expressed by open forms of mountains, hills, beaches, temples and holy places. However, contrary to Naficy’s “utopian prelapserian chronotope of the homeland” (Citation2001, 152), her Edenic India is tainted with superstition, oppressive customs and traditions. In “Varanasi, Kalighat, Rishikesh, Hardwar,” Shaila states that “astrologers and palmists seek me out and for a fee offer me cosmic consolations” (Greif, p. 618); widowers were shown new bride candidates and most of them would marry within a month despite their will since “they cannot resist the call of custom, the authority of their parents and older brothers” (Greif, p. 618). Moreover, her representation of India is not accompanied by nostalgia and a sense of loss. In a retrospective passage, where Shaila remembers India, she is reminded of the disturbing conflicting worldviews of her grandmother and her parents which have trapped her “between two modes of knowledge” and have made her “flutter between worlds” (Greif, p. 618). In addition, people in India are not depicted as all sympathetic and consoling. The man in uniform “with the popping boils” at the airport, indifferent to the grief of his compatriots, orders them to wait and refuses to cooperate because his boss is on a tea break (Greif, p. 617). Therefore, India is not that Edenic place, where Shaila feels comfortable and longs to stay for the rest of her life. After six months in India, she feels forced to leave when her husband’s spirit tells her “you must finish alone what we started together” (Greif, p. 619), sending her back to Canada on a mission.

Canada, as the host country, is not a place where Shaila can fit properly either. The chronotope of the host country is expressed in a claustrophobic closed-form which suggests entrapment, isolation and anxiety. The events in Canada mostly take place in the closed spaces, such as Shaila’s house, the old Sikh couple’s apartment and Judith’s car. At the beginning of this narrative, Shaila is in an alienating and confusing situation; she is detached from the neighbors who have crowded her house; she stands in a claustrophobic space where she hears her children’s and her husband’s voices all around her: “I hear my boys and Vikram cry, ‘Mommy, Shaila!’ and their screams insulate me, like headphones” (Greif, p. 612). Another location in Canada is the old Sikh couple’s apartment inside which Shaila “wince[s] a bit from the ferocity of onion fumes” (Greif, p. 620) and sees their two rooms as “dark and stuffy” with only “an oil lamp sputter[ing] on the coffee table” (Greif, p. 620). Her relationship with Judith also involves the plot of entrapment and escape. Shaila, who suffers from her own conflicting feelings, is unable to reject Judith’s insisting request to help her with the old Sikh couple. Though she feels uneasy opening up to these people and “stiffen[s] at the sight of beards and turbans” (Greif, p.620), she feels forced to accompany her.

Due to her calm behavior, Shaila becomes Judith’s “confidante, one of the few whose grief has not sprung bizarre obsessions” (Greif, p. 619). It has made Judith believe that she has accepted the death of her family and now is on the path to recovery; however, Shaila herself does not understand why she is calm and quiet, unlike other hysterical “relatives.” She confesses that she was “always controlled,” but she is confused with this “terrible calm,” which will not leave her. Most probably, the shock of this huge disaster has given her this “deadening quiet,” nevertheless, the influence of her parents’ rationality and her assimilation into the new attitudes of the host country, as possible reasons for her calm behavior, should not be ignored. She is torn between her feelings: on the one hand, she understands Judith’s rationality and her attempts to help her compatriots, on the other, she realizes her affinity to the Indian culture and its way of grieving. More than ever, in her conversation with the old Sikh couple she confronts this duality in her feelings and the frailty of her assimilated identity.

After overcoming her initial distrust and disgust towards the Sikh couple, Shaila is able to feel sympathy towards them, not as Sikh people, but as some relatives who share her grief. She connects with them and reads this message in the old man’s eyes: “Give to me or take from me what you will, but I will not sign for it. I will not pretend that I accept” (Greif, p.621; original emphasis), which forces Shaila to face her own pretense and realize her calmness to be a defense against the threat of revealing the difference between her behavior and the accepted behavior of the host country. Shaila is unable to convey her real feelings to Judith; she cannot cross the cultural barriers and make her understand the Indian culture and their beliefs. She is unable to admit that “my boys and my husband are with me too, more than ever” (Greif, p. 621). She cannot tell Judith that her family “surrounds me and that like creatures in epics, they’ve changed shapes”; she is unable to “tell her my days, even my nights, are thrilling” (Greif, p. 620). She cannot declare “it’s a parent’s duty to hope” (Greif, p. 621). Shaila’s inability to convey her feelings and her choice of remaining silent, according to Deborah Bowen (Citation1997), prove her “awareness of the difficulty of translation” between cultures and her fight “against both subalternity and forced assimilation” (p. 55). However, the word “pretend” in the old man’s message and the distress it causes seem to assert Shaila’s awareness of her own pretense. She cannot tell Judith how she feels lest she finds out that Shaila is not properly assimilated to the new culture. Her meeting with the old couple uncovers her unconscious attempt to hide her feelings, which results in her distress and breakdown. Her realization of her own pretense, her anger at Judith for her lack of understanding and her irrational insistence on changing different manners of grieving to what she believes to be the standard behavior urge Shaila to escape from Judith and get out of her car right after leaving the old Sikh couple.

4. The chronotope of third space

“Border chronotope” or “threshold chronotope,” in Bakhtin’s writings, refers to “the problematic of existential transition, a critical transitory moment in the life of a character,” away from imperial/colonial relations and imperial differences (Tlostanova, Citation2010, p. 260). However, taken into the context of transcultural writings and movies, it could represent the chronotope of the third space which involves “transitional and transnational sites, such as borders, airports, and train stations, and transportation vehicles, such as buses, ships, and trains” (Naficy, Citation2001, p.154). This chronotope mostly includes narratives of border-crossing and journeying which engage these sites and vehicles. Airplanes, as Jigns Desai (Citation2004) notes, are associated with “the spatial mobility and displacement of diaspora,” which like Paul Gilroy’s ships are the setting of a “suspended time and space, of a displacement from the normative identifications” (p. 120). However, unlike the slave ship, airplanes are “ambivalent and ambiguous vessels” since they are uncontrollable by those who seek refuge; they may explode and break dreams of escape (Desai, Citation2004, p. 120). The terrorist plane crash is at the heart of “The Management of Grief” and though this airplane has been exploded earlier than the beginning of the narrative, its presence is felt in the memory of all the characters and it becomes the main focal object. The air crash deflates Shaila’s hope of escape from the political disputes and shatters her dream of founding new stable home and identity in Canada: “we, who stayed out of politics and came half way around the world to avoid religious and political feuding, have been the first in the New World to die from it” (Greif, p. 622).

In search of a new beginning and new life, away from the political and cultural disputes, Shaila and her husband had left India and immigrated to the multicultural environment of Canada. They found jobs, bought a beautiful “pink split-level” house, had successful children and became an “envied family” within the Indian community in Canada. They had planned to establish a new home in the new environment and this is “what [they] started together,” which must be finished by Shaila alone (Greif, p. 619). Before facing the crisis of the plane crash, Shaila had naively believed in her newly attained stable identity in the new country. Due to the air crash, she lost her secure and stable identity as a wife and a mother in the host country, where she had considered her new home. Now she is forced to remake herself and create a new identity; she has to admit and face the hostility of the government, which evades taking responsibility for the disaster and instead, tries to put blames on other things, such as “space debris,” “Russian laser” and “some accident.” She silently agrees with one of her neighbors who bitterly swears when he sees the indifferent Canadian government: “Damn! How can these preachers carry on like nothing’s happened?” She thinks with herself “we’re not that important. You look at the audience, and at the preacher in his blue robe with his beautiful white hair, the potted palm trees under a blue sky, and you know they care about nothing” (Greif, p. 612). After the crisis, she realizes her situation as a stranger in Canada; as a person who is “suspended in the empty space between a tradition which they have already left and the mode of life which stubbornly denies them the right of entry” (Sarup, Citation2005, p. 98). Like Madan Sarup’s “stranger,” through assimilation, Shaila had tried to erase the “stigma,” which emphasizes the difference between cultures. However, this difference seems irreparable and forces strangers stand between “the inside and the outside, order and chaos, friend and enemy” (Sarup, Citation2005, p. 98). Shaila, then, has blurred the boundary and crossed the frontier, but she is neither fit in her homeland nor in the host country; she has been uprooted from each and not at home in either; hence, she is living in the constructed world of third space.

The idea of displacement and transition in the third space is also strengthened by the characters’ travel aboard airplanes to return to the territory of their origin and then back to the host country. This transitory situation, as a result of immigration, has granted them a “double consciousness” or “double vision,” which is specific to the way of either the home or the host chronotope. However, the immigrants are “always in negotiation with both. Their identities are governed by a diasporic chronotope that is inherently split into two (or more) parts that are inflected through each other” (Peeren, Citation2007, p. 74). They live in the liminal third space, which is not defined by the concrete time and space like that of homeland or host chronotopes; diaspora, then, can be regarded as a way of living in “dischronotopicality” (Peeren, Citation2007, p. 72). In diaspora, the very practices of constructing meaning, allocating value and determining status, which are all related to the formation of identity, can take place perfectly in conditions of traveling and movement away from home, as an independent entity complete in itself.

Thus, the very presence of the migrant in diaspora and the mobility and fluidity of its culture unveil the fact that “cultural practices are not tied to place and are deterritorialized” (Smith, Citation2004, p. 256), which resembles what Peeren calls “dischronotopicality.” Therefore, culture and subjectivity in the “third space” would be constructed through “performative enactment,” that is, performative construction of time-space through re-enacting and remembering the homeland chronotope and negotiating it with the host chronotope and its culture (Peeren, Citation2007, p. 73–4). In the third space, by remembering their native traditions and negotiating them with the culture of the host country, immigrants are able to create a culture and identity, which transcend both territories. In this short story, the Indians by remembering and re-enacting their traditional ways of clothing, cooking, tea making, grieving, giving parties and having community newspaper and at the same time, working, participating in the Canadian communities or supporting charities are able to create an Indian diasporic community in Canada. Nevertheless, it should be mentioned that diaspora is lived differently by its individuals, and shared origin does not guarantee similarity in their behavior. For instance, each individual in the Indian diaspora deals with his or her grief in his/her own way or even a kind of hostility may emerge among them, like the hatred and distrust Shaila feels towards Sikhs.

Leaving India for Canada, Shaila was hopeful she might be able to avoid the political and religious disputes of her home and find a new stable identity for herself in the new country. Longing to be accepted as a member of the Canadian society, she had tried to adapt herself to the new environment. However, the plane crash evokes her self-awareness, leads her to understand the unstable nature of identity and forces her to admit her inability to fully assimilate into the Canadian culture. She understands that her identity is always changing and is shaped through negotiation with others, in the same way that her grieving stands in between different perspectives. Moreover, by recognizing and acknowledging her difference from the dominant culture, Shaila is able to resist Judith’s easy categorization. In this sense, Bhabha’s concept of hybridity seems to fit her more and more. For Bhabha, who is himself under the influence of Bakhtin, hybridity is the moment of challenge and resistance against the dominant cultural power. Similar to Bakhtin, who maintains that there is always a mixture of the authorial language with traces of the other language/voice with which it has dialogized, Bhabha believes that hybridity of the colonial discourse disturbs the power relation present in the colonial situation by recognizing the voice of the other in its discourse and proving to be “double- inscript[ed]” (Bhabha, Citation2007, p. 154). However, Bhabha’s hybridity entails mimicry as a “form of difference that is almost the same but not quite,” denoting that while the colonized people are encouraged to repeat certain traits, beliefs and values of the colonizers, in actuality, they are able to maintain an element of their own cultural differences (Bhabha, Citation2007, p. 127). Hence, underneath assimilation, there is a sense of rejection, which pushes mimicry close to mockery (Bhabha, Citation2007, p. 85). In Shaila’s case, nevertheless, there is no sense of mockery in her attitude since she tries to assimilate into the host country and has no intention of mocking Western culture.

To some extent, Shaila has adapted to the Canadian culture and understands Judith and her rational acceptance of the tragedy; like Kusum, she sees the spirit of her husband and her sons around her; like the old Sikh couple she is hopeful and brings a suitcase “packed heavy with dry clothes for [her] boys” (Greif, p. 617). Her identity, as a woman, has also been under the influence of such negotiations. While at the airport, she screams at the guard and swears at him. Later, she contemplates that “once upon a time we were well-brought up women; we were dutiful wives who kept our heads veiled, our voices shy and sweet” (Greif, p. 618). Living in Canada has influenced her gender identity and has enabled her to shake off the oppressive Indian traditions against women. Nevertheless, she stands in between two cultures and cannot erase her tradition altogether. She confesses to Kusum, at the day of disaster, that she never told her husband that she loved him since she was “too much the well-brought up woman.” She was so well-brought up that she “never felt comfortable calling [her] husband by his first name” (Greif, p. 613).

Perceiving and contemplating her own thoughts and other characters’ behavior, especially the old Sikh couple, regarding the plane crash, she gradually sees the dualities of her own character and instability of her identity. Therefore, the narrating “I” of the first part stands in contrast to the narrating “I” of the last part, where she understands and welcomes her existence in the third space. The third space, however, is not the only place where she feels confused and uncertain. The nonsense rationality of her parents and the “mindless mortification” of her grandmother had made her “flutter between worlds” even in her homeland (Greif, p. 618). While she was previously repelled by the idea of uncertainty and was angry for not having a fixed identity, several months of grief, contemplation and assessment of her situation make her accept and embrace uncertainty and instability. Just a week before writing the last part of the diary, Shaila hears the voice of her family who tells her: “Your time has come. Go, be brave” while she does “not know where this voyage [she has] begun will end.” She does not “know which direction [she] will take. [She] dropped the package on a park bench and started walking” (Grief, p. 623). This perplexity, nevertheless, is expressed in the “open chronotope,” which alleviates the tension such confusion creates and approves this idea that the narrator now has accepted the uncertainty of her situation more calmly. She hears their voice in “one rare, beautiful, sunny day” while “walking through the park. … The day was not cold, [she] looked up from the gravel, into the branches and the clear blue sky beyond” (Grief, 622–3).

5. Conclusion

Since Mukherjee wrote The Middleman and Other Stories, both American and Canadian policies regarding immigration, assimilation and multiculturalism have undergone some changes. Each year more and more immigrants with non-European origins enter Canada and contribute to Canada’s economy and social diversity. In contrast with Trump’s America, Canada has welcomed 320,932 immigrants between July 2015 and July 2016, approximately 60% more than the US welcomed (Adams, Citation2017, p. 56). Besides, Canada’s multiculturalist policy “has evolved from song and dance in the 1970s, to anti-racism in the 1980s, to civic participation in the 1990s, and to fitting in in the 2000s” (Wong & Guo, Citation2015, p. 4). That is, it has shifted from “ethnicity multiculturalism with focus on “celebrating differences” in the 1970s to “integrative multiculturalism” with focus on “Canadian identity” in the 2000s (Wong & Guo, Citation2015, p. 4). “Integrative multiculturalism,” namely, assimilation into Canadian society has been introduced as a solution for the earlier fragmented multiculturalism. Not only in Canada, but also in the United States and the European Union, with terrorism on the rise, scholars are talking about “post-multiculturalism” or “end of multiculturalism” to suggest the need to “move beyond current policies and practices of multiculturalism and to find different approaches … to foster social cohesion and promote assimilation and a common identity” (Wong & Guo, Citation2015, p. 6). Along the same line, Trump administration’s vision for “American greatness,” according to Julia G. Young (Citation2017), is “a nativist one,” which is a return to the America of 1920s defined by emphasis on assimilation and restriction of immigration based on “national, ethnic, and religious criteria” (p. 218). However, assimilation could be as harmful as fragmented multiculturalism to interracial relationships, as Wong (Citation2015) in his critique of one-dimensional approach to multiculturalism reminds us. He contends that if true multiculturalism is to survive, we should follow Hartmann’s and Gerteis’s two-dimensional model in which “interactive pluralism” replaces both assimilation and fragmented multiculturalism. Hall, drawing upon the work of Bhabha and Derrida, argues that this strategic approach suggests cultural “negotiations,” “a wave of similarities and differences that refuse to separate into fixed binary oppositions” (qtd. in Wong, Citation2015, p. 84) and settle down somewhere in between, as a hybrid identity in the third space, as discussed in this article.

With assimilation increasingly emphasized around the globe now, those literary works that promote interactive pluralism and hybridity in the third space should receive more attention. Mukherjee’s characters are always hovering in an in-between contradictory space. Many studies have focused on the hybrid nature of these characters and the way they form their identities through negotiation in the third space. However, Mukherjee’s concept of hybridity and third space, it is suggested, differ from one group of fictional works to the other. Some of her female characters, like Tara in The Tiger’s Daughter or Dimple in Wife, are frustrated at their inability to feel at home either in India or America. Unlike them, Jasmine rejects her roots and struggles to assimilate into American culture until she achieves oneness with the American dream. Debby, in Leave It to Me, also becomes representative of American youth culture despite her engagement with diasporic communities. Still, Tara of the Desirable Daughter and The Tree Bride, while tries to form her identity by drawing from Bengali, British (through colonial discourse) and American culture, she feels unable to uproot herself from her traditional culture. Shaila, in “The Management of Grief,” is also in the process of “uprooting and re-rooting” or “unhousment and rehousement,” in Mukherjee’s and Blaise’s words (Mukherjee, Citation1989a, p. 648). However, she gradually matures and understands that her uprooting from her homeland does not guarantee her complete separation from her native culture and its political disputes. Moreover, she realizes that she and her other compatriots are living in the third space, in the interstitial space between two cultures, neither able to return nor completely assimilate to the host country, but only able to negotiate their identities with others. She also acknowledges the instability of identities and accepts uncertainty and confusion more easily and more confidently in the last part of the narrative, where the tension of perplexity is relaxed through the open chronotope. As mentioned earlier, despite being set in Canada, the story reflects Mukherjee’s positive attitude toward America, which made it possible for Shaila to acknowledge her place in the third space and negotiate her identity between different cultures in Canada in contrast with the protagonists of the novels preceding and following The Middleman. This is how she “manages” to deal with her loss. This is how, the story implies, many people have to “manage” in a world full of “grief.”

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sahar Jamshidian

Sahar Jamshidian received her PhD in English literature from University of Tehran, Kish International Campus and is currently an assistant professor at Malayer University, Iran. She is interested in cultural studies, ethics and the relationship between self and the other in both postcolonial and feminist contexts.

Hossein Pirnajmuddin

Hossein Pirnajmuddin is an associate professor of English literature at University of Isfahan, Iran. His research interests include Renaissance literature, contemporary English fiction, literary theory, and translation studies.

References

- Adams, M. (2017). Could it happen here? Canada in the age of trump and brexit. New York & Toronto: Simon & Schuster.

- Anderson, S. L. (2016). Immigration, assimilation, and the cultural construction of American national identity. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogical imagination: Four essays. M. Holquist (Ed.). C. Emerson & M. Holquist (Trans.). Austin and London: University of Texas press.

- Banerjee, D. (1993). In the presence of history: The representation of past and present Indias in Bharati Mukherjee’s fiction. In E. S. Nelson (Ed.), Bharati Mukherjee: Critical perspectives (pp. 161–17). New York, NY: Garland.

- Bhabha, H. K. (2007). The location of culture. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Bowen, D. (1997). Spaces of translation: Bharati Mukherjee’s ‘The Management of Grief’. ARIEL, 28(3), 47–60.

- Desai, J. (2004). Beyond bollywood: The cultural politics of South Asian diasporic film. London: Routledge.

- Gabriel, S. P. (1999). Construction of home and nation in the literature of the Indian Diaspora, with particular reference to selected works of Bharati Mukherjee, Salman Rushdie, Amitav Ghosh and Rohinton Mistry (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). The University of Leeds, West Yorkshire, England.

- Hammond, A. (2007). Cultural perspectivism in Bharati Mukherjee’s short stories. In J. Kuortti& & R. Mittapalli (Eds.), Indian women’s short fiction (pp. 191–210). New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers & Distributors LTD.

- Heyer, K. E. (2018). Internalized borders: Immigration ethics in the age of Trump. Theological Studies, 79(1), 146–164. doi:10.1177/0040563917744396

- Holquist, M. (2002). Dialogism: Bakhtin and his world (2nd ed.). London & New York: Routledge.

- Jaidka, M. (1999). Leave it to me by Bharati Mukherjee. Review. MELUS, 24(4), 202–204. doi:10.2307/468189

- Knippling, A. S. (1993). Toward an investigation of the subaltern in Bharati Mukherjee’s The Middleman and other stories and jasmine. In E. S. Nelson (Ed.), Bharati Mukherjee: Critical perspectives (pp. 143–160). New York, NY: Garland.

- Lawson, J. (2011). Chronotope, story, and historical geography: Mikhail Bakhtin and the space-time of narratives. Antipode, 43(2), 384–412. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2010.00853.x

- Mabardi, S. (2000). Encounters of a heterogeneous kind: Hybridity in cultural theory. In R. Grandis & Z. Bernd (Eds.), Unforeseeable Americas: Questioning cultural hybridity in the Americas (pp. 1–20). Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Miller, K. (2004). Mobility and identity construction in Bharati Mukherjee’s desirable daughters: The tree wife and her rootless namesake. Studies in Canadian Literature, 29(1), 63–73.

- Morris, P. (1994). The Bakhtin reader. London: Edward Arnold.

- Mukherjee, B. (1971). The Tiger’s Daughter. Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin.

- Mukherjee, B. (1975). Wife. Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin.

- Mukherjee, B. (1981, March). An invisible woman. Saturday Night, 96, 36–40.

- Mukherjee, B. (1985). Darkness. New York, NY: Fawcett Cress.

- Mukherjee, B. (1989a). An interview with Bharati Mukherjee. Interview by A.B. Carb. The Massachusetts Review, 29(4), 645–654.

- Mukherjee, B. (1989b, January 30). An interview with Bharati Mukherjee. Interview by C. McGree. Foreign Correspondent.

- Mukherjee, B. (1989c). Jasmine. New York, NY: Fawcett Crest.

- Mukherjee, B. (1990a). An interview with Bharati Mukherjee and Clark Blaise. Interview by M. Connell, J. Grearson, & T. Grimes. The Iowa Review, 20(3), 7–32. doi:10.17077/0021-065X.3908

- Mukherjee, B. (1990b). An interview with Bharati Mukherjee. Interview by M. Jaggi. Bazaar: South Asian Arts Magazine, 13(8), 9.

- Mukherjee, B. (1995, December 31). Bharati Mukherjee: Interview. Interview by V. Nabar. Times of India.

- Mukherjee, B. (1998). Leave it to me. New York, NY: Fawcett Crest.

- Mukherjee, B. (2002a). The management of grief. In J. G. Parks (Ed.), American short stories since 1945 (pp. 611–623). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Mukherjee, B. (2002b). Desirable daughters: A novel. New York, NY: Hyperion Books.

- Mukherjee, B. (2004). The tree bride. New York, NY: Theia.

- Mukherjee, B., & Blaise, C. (1977). Days and nights in Calcutta. New York, NY: Doubleday.

- Naficy, H. (2001). An accented cinema: Exilic and diasporic filmmaking. New Jersey & Oxfordshire: Princeton University Press.

- Nunning, A. (2001). On the perspective structure of narrative texts. In W. V. Peer & S. B. Chatman (Eds.), New perspectives on narrative perspective (pp. 207–223). New York: State University of New York Press.

- Nyman, J. (2004). Imagining transnationalism in Bharati Mukherjee’s leave it to me. In J. Kupiainen, E. Sevänen, & J. Stotesbury (Eds.), Cultural identity in transition: Contemporary conditions, practices and politics of a global phenomenon (pp. 399–418). New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers & Dist.

- Peeren, E. (2007). Through the lens of the chronotope: Suggestions for a spatio-temporal perspective on diaspora. In M. A. Baronian, S. Besser&, & Y. Jansen (Eds.), Diaspora and memory: Figures of displacement in contemporary literature, arts and politics (pp. 67–78). Amsterdam & New York: Rodopi.

- Reid, D. (2013). Bakhtin on the nature of dialogue: Some implications for dialogue between Christian Churches. The Finnish Society for the Study of Religion. Temenos, 49(1), 65–82.

- Roy, A. (1993). The aesthetics of an (Un)willing immigrant: Bharati Mukherjee’s days and nights in Calcutta and Jasmine. In E. S. Nelson (Ed.), Bharati Mukherjee: Critical perspectives (pp. 127–142). New York, NY: Garland.

- Sarup, M. (2005). Home and Identity. In G. Robertson, M. Mash, L. Tickner, J. Bird, & T. Putnam (Eds.), Traveler’s tales: Narratives of home and displacement (pp. 89–101). London & New York: Taylor & Francis e-Library.

- Singh, R. P. (2010). “I want to be surprised when I hear your voice”: Who speaks for Jasmine? In K. Singh & R. Chetty (Eds.), Indian writers: Transnationalisms and diasporas (pp. 69–86). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Smith, A. (2004). Migrancy, hybridity, and postcolonial literary studies. In N. Lazarus (Ed.), The Cambridge companion to postcolonial literary studies (pp. 241–261). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stoneham, G. (1996). ‘It’s a free country’: Bharati Mukherjee’s vision of hybridity in the metropolis. Wasafiri, 12(24), 18–21. doi:10.1080/02690059608589499

- Tandon, S. (2004). Bharati Mukherjee’s fiction: A perspective. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons.

- Tlostanova, M. (2010). The imperial-colonial chronotope: Istanbul-Baku-Khurramabad. In W. D. Mignolo & A. Escobar (Eds.), Globalization and the decolonial option (pp. 260–281). London & New York: Routledge.

- Wong, L. (2015). Multiculturalism and ethnic pluralism in sociology: An analysis of the fragmentation position discourse. In L. Wong & S. Guo (Eds.), Revisiting multiculturalism in Canada: Theories, policies and debates (pp. 69–90). The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

- Wong, L., & Guo, S. (2015). Revisiting multiculturalism in Canada: An Introduction. In L. Wong & S. Guo (Eds.), Revisiting multiculturalism in Canada: Theories, policies and debates (pp. 1–16). The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

- Young, J. G. (2017). Making America 1920 again? Nativism and US immigration, past and present. JMHS, 5(1), 217–235. doi:10.1177/233150241700500111