Abstract

Ambiguous figures, as described in visual perceptual psychology, are single pictures that contain several possible, mutually exclusive, motifs. When looking at a rock-art panel, petroglyphs at a first glance can seem to be distributed randomly, but when physically moving around on the panel new patterns can start to emerge. We discovered that some figures seemed to represent two different motifs depending from which angle they were observed. The figures thus became ambiguous. Some specific cases of images in South Scandinavian Bronze Age rock art—of ships, cows and circles—lend themselves particularly well to be analysed as ambiguous figures. Furthermore, we propose that these images represent some sort of narrativity, which needs to be understood in order to make a perceptual switch between different motifs in one picture. Using a semiotic approach, we describe the experiential requirements on the perceiver for seeing the different motifs.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

For almost two centuries, researchers had claimed that it is possible to reveal visual narratives by studying rock art in south Scandinavia, and comparing these images with ethnographic and historical sources. These complementary sources are distant in both time and space and their relevance for the study of rock art is arguable. This paper introduces a new method of revealing visual narratives from rock art images. By acknowledging the existence of ambiguous images, where one single image contains several mutually exclusive motifs, it is possible to link different motifs to each other in a coherent way without using written sources. This method makes it possible to examine the narrativity of rock art as it is grounded in the data itself—the visual features and the distribution of the images on the panels—which makes the observer less dependent on external sources. By using this method, the paper concludes the existence of small-scale narratives consisting of up to three individual images possible to comprehend sequentially.

1. Introduction

In the present article we are analysing certain types of petroglyphs in south Scandinavia dating from ca. 1700 BC to c 200 BC that we classify as being “ambiguous figures”. We suggest that the principle of ambiguous figures, as defined within the framework of visual perception research (Goldstein, Citation2010), may fruitfully be applied to some cases of Bronze Age rock art in south Scandinavia. Specifically, we will suggest that ambiguous figures can be indicative of narratives and thereby improve our understanding of these pictorial cultures. However, we also underline that we cannot fully know why petroglyphs were made, or what purpose they had, but theory might help us on the way to an understanding by way of looking at the carvings as such. Subsequent interpretation of the observations may give us some important clues as to their possible meaning(s) for the people who made them. Our own observations adhere to what the philosopher and semiotician Charles Sanders Peirce (Citation1903/1998b) called abduction, which is characterised by a reaction of surprise, followed by the urge to form a hypothesis that might explain what has been perceived. Staggering figures caught our attention when we moved around on horizontal panels among the petroglyphs, seeking to find an explanation to why these appeared to represent different motifs depending from which angle they were perceived. We then formed our hypothesis that these might belong to a category of imagery that in modern cognitive visual psychology is termed ambiguous figures. Thus, this became a starting point to the inquiry into the possibility of Bronze age ambiguous figures.

Ambiguous figures may in short be described as figures that contain one or more motifs, or have motifs partly embedded in larger motifs. There are classic examples of the former in the history of psychology, such as the “Rubin vase” and the “Duck—rabbit” (Figures and ). In addition, ambiguous figures may be of different kinds with respect to the interpretation processes that they require: the Rubin vase is an example of “visual hypotheses testing” (Figure ), while e.g., the classical Kanizsa triangle illustrates an example of “filling in” missing lines (Figure ) where the shape of a triangle is being created by the effects such a shape would have had on underlying features. (Further examples of perceptual phenomena in pictures can be found in e.g., Hodgson & Pettitt, Citation2018). These two phenomena in particular—visual hypothesis testing and filling in—are relevant for the examples of ambiguous figures from the Bronze Age brought up here.

Figure 1. Edgar Rubins’s Vase/face illusion (Citation1915/2005). Original published in Synsoplevede Figurer [“Visual Figures”] around 1915. Retrieved 2019–10-28 from https://da.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edgar_Rubin#/media/Fil:Facevase.png.

![Figure 1. Edgar Rubins’s Vase/face illusion (Citation1915/2005). Original published in Synsoplevede Figurer [“Visual Figures”] around 1915. Retrieved 2019–10-28 from https://da.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edgar_Rubin#/media/Fil:Facevase.png.](/cms/asset/279cd9cb-c067-4c90-8443-d97df1fa1f79/oaah_a_1802804_f0001_b.gif)

Figure 2. J. Jastrow’s (Citation1899/2006) “The duck/rabbit illusion” (original published in Popular Science Monthly 1899. Retrieved 2019–10-28 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Duck- Rabbit_illusion.jpg#filehistory.

Figure 3. “The Kanizsa Triangle”. From Fibonacci (Citation2007), original by G. Kanizsa published in 1979. Retrieved 2019–10-30 from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/55/Kanizsa_tri angle.svg/768px-Kanizsa_triangle.svg.png.

Research shows that humans are predisposed to fill in lines or gaps which might be missing in an image in order to be able to perceive the motif (Hodgson & Pettitt, Citation2018), it also shows that human visual perception is multistable (Leopold et al., Citation2002). This means that human visual perception might alter with respect to interpretation when exposed to images, or other patterns, which are ambiguous or contradictory (Leopold et al., Citation2002). See the classical examples in Figures and , where one can switch between the respective interpretations, but not uphold both views at the same time. Consequently, visual perception can also alter between interpretations of several motifs within a single image. If one should apply this to Figure , it could for example, be that a squiggle in the middle of the picture could either be a pattern on the vase, or it could be something that was coming out of the mouths of the facing people. That is, one thing changes meaning due to the active interpretation of involved motifs. On a local level this is already taking place with regards to the features that either makes out the anatomy of a face or the figure of a vase, depending on the active visual hypothesis. But in this latter case the features are integral to the motif being appreciated, while in the former case with the (imagined) squiggle, the interpretation of the squiggle depends on the previous identification of a motif. What both phenomena illustrate, however, is a general fact about visual perception: that parts and wholes inform each other. A very clear example where the exact same local information gets new meaning in a different global context, can be found in Figure .

Figure 4. Gustave Verbeek’s (Citation1904/2005) “A Fish Story” from The Upside Downs of Little Lady Lovekins and Old Man Muffaroo (original published in The New York Herald, around 1904. Retrieved 2019–10-28 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Verbeek-rocanoe.gif.

Another relevant concept in the analysis of ambiguous figures is the notion of “iconic sign”. Central is the assumption that many of the images depicted in rock art are iconic signs, more specifically they are images, standing in a relation of similarity to the object they depict (Peirce, Citation1903/1998b; Sonesson, Citation2013). Without going into detail here, relevant for our purpose is also to what extent convention (habits) is involved in our understanding of signs (Sonesson, Citation2013). Since rock art was made and perceived in a specific cultural context that could vary over time depending on the development of the cultures, their meaning arguably also varied over time. We therefore focus on the iconic images as such, rather than on their possible specific meaning in a Bronze Age context. In this, our approach resembles the one that the psychologist Peter Van Sommers (Citation1991) adopts in his study on the development of systems of writing, including the hieroglyphs in Egypt, the cuneiform in Mesopotamia and the Greek alphabet as it developed from Semitic scripts, as he focuses on the “graphic aspects” of the scrips, rather “the way they mapped onto sounds and ideas” (Citation1991, p. 3).

The idea that the nature of the meaning bearing elements in a sign change over time, as the example of the Cuneiform in van Sommers’s study (Citation1991) shows, might also be applied to Bronze Age petroglyphs, As we have pointed out, some signifying elements in the icons are lost to contemporary interpreters, namely those that were grounded in customs and habits prevailing at the time the petroglyphs were made, and that we fail to reproduce today. Thus, the meaning of a sign is typically subject to change, depending on who, in time and space, is the interpreter (Peirce, Citation1894/1998a).

In this paper we also claim that certain rock art images, what we call ambiguous figures, were not carved in order to point directly to a referent/object, but were, for some reason, variable with respect to their possible motif(s) from the point of view of a beholder. Otherwise put, these images were made to incorporate more than one iconic motif, by way of triggering a process of altering visual perception, that would oscillate from one motif to the other, as in the case of Figures –. Particular, however, to Bronze Age ambiguous figures is that the perceiver needs to move in order to see the different motifs in the ambiguous configuration.

This emphasises the importance of studying the Bronze Age images on their own premises which lead us to the following two questions, that will be of central importance to our study:

1) How are ambiguous figures composed in South Scandinavian Bronze age rock art? and,

2) What could the possible function(s) of ambiguous figures in South Scandinavian Bronze Age rock art be?

2. What are ambiguous figures?

Often the term ambiguous figure is used interchangeably with the term “reversed figure”, and typical examples of this type of figures are the Rubin’s vase (vase/two profiles), the duck/rabbit illusion and the Kanizsa triangle mentioned above (Figures –). Another example, which show similarities with the Bronze Age examples we are going to discuss since it needs to be looked upon from two different positions, is an image from The Upside Downs of Little Lady Lovekins and Old Man Muffaroo, “A Fish Story” by Gustave Verbeek (Figure ).

The general conception of ambiguous figures is that they are open to several interpretations, due to their specific construction, and more specifically the reversible figures are those constructions that usually lend themselves to two alternative interpretations, each interpretation referring to a different object, as seen in Figures , and above. Closely related to reversible figures are “embedded figures” which can be found in e.g., animal art of the Migration Period (Lindstrøm & Kristoffersen, Citation2001). The difference between them is that in the embedded figures, as the name alludes, one or several figures can be perceived within one image, and do not share all contour outlines with the other figures in the larger image material.

What we find in our material is instead ambiguous images that share all contour outlines, but which will be perceived differently depending upon the position of the perceiver. For example, an image may alter between being perceived as a ship or as a cow depending upon where the spectator is standing (Figure ). Generally, a rock art panel does not favour a specific “station point” from where the images should be seen, but it is possible to walk around and perceive the images from different angles (Janik, Citation2014). The notion of station points is thus crucial when discussing ambiguous figures on a horizontal rock surface.

Other images can be regarded as embedded, since details in the images can be regarded as either part of a whole, or as separate icons. For example, the cow’s horn can either be just horns, or the shape can be regarded as a circular image and then for example, represent the sun or/and the moon (Figure ). In the former case the whole probably carries a particular meaning based on a cultural cosmological narrative beyond the scope of our study (for further readings about the implications of moon-sun connections, see Sims, Citation2006).

Furthermore, we also find fruitful Lindstrøm and Kristoffersen (Citation2001) definitions of three levels of ambiguity: 1) Ambiguity within motifs, 2) Ambiguity on a compositional or structural level (broken symmetry) and 3) Ambiguity on an iconographic level in which elements of different species are mingled. It is foremost 1) and 3) that are of importance to our analysis. The reasons are that the examples we have found consist of ambiguous figures composed of parts that separately can be perceived as images or iconic signs in themselves. The ambiguity is then within motifs; for example, the cow’s horn being a circle (Figure ). Furthermore, the relations between the parts of the whole are ambiguous when it comes to classification of object, i.e. different motifs are combined in the same image. In our case we can observe an intertwined combination of ships, bulls or cows (hereafter cows), and circles which can be perceived as different motifs depending upon the station point (see discussion below).

We adhere, thus, to Christopher Tilley’s approach (Citation1991) expressed in his outlines of previous research of Nämforsen, namely the importance of paying attention to the relations between the figures and not only on the figures themselves in isolation. We believe, in line with Tilley (Citation1991) that the relations between the images are not random, but on the contrary, these carry meaning. Specifically, examples of overlaps are of utmost interest, because these “must have been intentional” (Tilley, Citation1991, p. 56). The most common overlaps at Nämforsen are “between elks and boats and elks and humans” (Tilley, Citation1991, p. 57). Our examples differ from Tilley’s, due to images not being superimposed, but the different icons rather seem to have been composed as being part of the same image, and thus as part of its original design.

2.1. Rock art as signs

Peirce elaborated a sophisticated system of signs which rests on the assumption that humans use signs to make sense of the world, and that understanding the world is based on an endless interpretation of signs (see e.g., Preucel & Bauer, Citation2001; Rédei et al., Citation2018 for the application of semiotics to archaeology). Already from an early age, human children start to interpret the world in terms of signs (e.g., A. Nilsson, Citation2014) and through the acquisition of language our body and mind are connected to the socio-cultural context surrounding us (Danesi, Citation2004; Sonesson, Citation1989). On a basic level, signs can be classified in three main categories: Icons, Indexes and Symbols. Petroglyphs could potentially contain elements of all three signs, but predominantly they are iconic signs standing in a relation of similarity to the object they depict. For instance, we easily recognise the similarity between the rock art image of an ard (plough) with real wooden ards that have been found in bogs (Skoglund, Citation2016).

However, there are examples of a certain type of rock art images (i.e. icons) where the indexical features are prominent, as for example, carvings showing a pair of legs that can be assumed to stand for the whole object, i.e., a human being, the only bipedal animal with calves (excluding e.g., birds). Indexical signs, thus, stand for their objects on the basis of either being parts of the wholes that they represent (factorality) or of being an indication of a previous event in time (contiguity). A classic example is that of footprints in the sand being the indexical sign of somebody having walked by on a previous occasion. The footprints as an effect of this event has the potential to refer to the person that walked by. Thus, indexical signs depend on relations of closeness in space and time (Sonesson, Citation1989).

Many iconic signs, though, contain to a larger or lesser degree, elements of conventionality (Peirce, Citation1903/1998b, Citation1903/1998c; Sonesson, Citation1989). Consequently, degrees of iconicity can vary, i.e. to what degree similarity on its own can point out a referent to the image. A sun symbol, for example, commonly presumed theme in Bronze Age rock art, have iconic properties in the form of the shape of a sun, size relation to ships, etcetera but could easily be confused with other round things without a previous knowledge about sun images. As we will see, the dynamics between the iconic and the symbolic (in Peircean terms) is fundamental in connection to ambiguous figures.

When we consider rock art figures to be iconic signs, they, as all images, are subjected to what in visual semiotics is called “re-semantisation” (Sonesson, Citation1989). On the level of perception images are processed in parallel (Treisman & Gelade, Citation1980), in contrast to verbal language that are serially processed. Images are interpreted in a process of oscillating between wholes and their parts in a feedback loop. The visual hypothesis that one is viewing a particular whole feedback to the parts, which in turn make out the whole. Visual hypothesis testing can also be responsible for the phenomenon of “filling in” information that would be expected given a certain whole, but is not really there. While the Kanizsa triangle (Figure ) is probably a more direct, perceptual example of filling in, Figure illustrates it differently. If we accept that the rabbit ears also can be a duck beak, although it is not a perfect example of a beak, this sets off a series of expectations on the rest of the image. The beak makes the head more “duck like” and the interpretation of a duck head makes the beak more “beak-like”. In another visual context the rabbit ears would not be interpreted as a beak (nor ears perhaps).

3. Ambiguous images in South Scandinavian Bronze Age rock art

Lindstrøm and Kristoffersen (Citation2001) identified cases of embedded figures and reversible figures on Iron Age metalwork. They describe the imagery of animals in the material as “impossible to specify with regard to species” (Lindstrøm & Kristoffersen, Citation2001, p. 66) because details that are important for the interpretation of the images are omitted, and thus the art is difficult to comprehend. In the present paper we will similarly apply the concept of ambiguous and embedded figures to South Scandinavian Bronze Age rock art.

South Scandinavian Bronze Age rock art was produced from ca. 1700 BC to 200 BC (Ling, Citation2008, Citation2013; P. Nilsson, Citation2017; Skoglund, Citation2016). Many of the carvings are figurative and we are able to identify a very large number of ships but also human figures, foot soles, animals, weapons, circle images and other kinds of images.

Traditionally, South Scandinavian Bronze Age rock art images have been categorized into well-defined types such as ships or a human figure, and statistics based on such assumptions are common in rock art research (for example, Bertilsson, Citation1987; Hauptman, Citation2002; P. Nilsson, Citation2017; Skoglund, Citation2016). This approach has been criticized, however, and it has been questioned whether it is possible to at all judge what the images represent (Goldhahn, Citation2004; Ljunge, Citation2015). But given the strong similarity between depicted objects and preserved metal and wooden objects, we consider the images—at least partly—to be inspired by objects, humans and animals that appeared during the times of Bronze Age societies (Skoglund, Citation2016).

However, there are reasons to question the assumption that images always were intended to represent well defined types. It happens that images are ambiguous and do not fit into standardized schemas. Indeed, there are reasons to believe that images sometimes were made ambiguous by purpose in order to be open for different interpretations. Such a purpose could have been playful, metaphorical, poetic, narrative, etc.

A well-known example from the southern tradition is the paired outlined foot soles which sometimes are difficult to discern from wheel crosses. Foot soles are outline images where the line demarks the contour of the foot. Sometimes there is a transverse line added to indicating leather strings going beneath the foot to keep the moccasin in place (Hald, Citation1972; Malmer, Citation1981; Marstrander, Citation1963; Skoglund et al., Citation2017). When such foot soles with transversal lines are paired, they can also be seen as a wheel cross—i.e. a circle image divided into four segments by two crossing lines.

As indicated by the name, the circle images are circular, while the paired foot soles tend to have a more irregular shape. However, it happens that the individual foot soles are placed close to each other and are made almost circular. If these have only one transverse line and are sharing the same “inner line”, the composition cannot be separated from a wheel cross. These images will be ambiguous and different researchers will categorize them either as a wheel-cross or as a pair of foot soles. (Figure ) (Coles, Citation1999; Welinder, Citation1974).

Figure 5. Paired outlined foot soles at Boglösa in Uppland, Sweden, some of which can be interpreted as wheelcrosses. Photo Bertil Almgren. Shfa Bild- Id 12984.

On occasions like these it seems as if the person making the paired foot soles could have deliberately stretched them into an almost circular shape in order to create ambiguous images that could either be seen as paired foot soles or as a wheel-cross. In these examples, however, it is not clear if the ambiguity was intentional or merely a result of different kinds of images having similar kinds of shapes.

There are, however, similar and perhaps more explicit ambiguity in certain cases of images of cows, which could be interpreted as either a cow with almost circular horns or, when viewed from the opposite station point, a ship with a crew of four or five people and a circle images attached to the ship’s hull. These examples occur quite regularly, especially in northern Bohuslän and just going through the Swedish Rock Research Archive’s online database we have identified 50 such examples (https://www.shfa.se/; Appendix A).

Such a relationship would gain strength if these images (ships, cows and circles) also occur as separate images put together as parts of compositions. Thus, in order to give a background to this argument, we will first discuss the following combinations of images, before again turning our attention to the ambiguous cow-ship-circle images.

The ship-cow combination

The circle-ship-combination

The cow-circle combination

3.1. Cows, circles and ships in combination

A combination of images, which is especially common in northern Bohuslän, is the combination of a ship and one or several cows.

The cow-ship combination seems to have a rather restricted chronology and is defined to Montelius’ period 1 and 2, 1700–1300 BC. As pointed out by Ling and Rowlands (Citation2015), several cows often appear close to a ship, sometimes walking against it, almost as if embarking the ship. This is the case at Aspeberget in northern Bohuslän where five cows appear in close association to ships (Figure ). Three of these are aligned to a large ship and approaching it almost as if embarking the vessel (Ling & Rowlands, Citation2015; Rédei et al. Citation2018).

Figure 6. Example of close spatial association between cows (bulls) and ships. Aspeberget, Bohuslän, Sweden. Photo: Bertil Almgren. SHFA bild id 11838.

It also happens that some cow’s body is designed almost as a ship, blurring the difference between the two kinds of images, which is the case at Runohällen, also in northern Bohuslän (Figure ). Here a larger cow’s body is designed with vertical lines resembling lines that sometimes are found on ship’s hulls, where they are supposed to indicate ribs (Ling & Rowlands, Citation2015).

Figure 7. Example of cows (bulls) with “ship-like” bodies. Runohällen, Bohuslän, Sweden. Photo: Bertil Almgren. SHFA bild id 11645.

It has also been argued that the shape of some Bronze Age ships (i.e. the Rörby type of ship) having semicircular fore and aft stems, reflects the curvature shaped by cows’ horns (Ling & Rowlands, Citation2015). These examples demonstrate the cow and the ship images to be intertwined in several ways.

Due to the character of the horns the cow can also be associated with a circle image. The shape of the horns is often semicircular and together the two horns can make up an almost complete circle with only a small part missing, for example, in Torsbo in northern Bohuslän (Figure ).

Figure 8. Cows and ships in close spatial association. Note the almost circular shape of the horn on some of the cows. The connection through roundness is further strengthen by the cup-mark enclosed in the horn-formation of the animal to the bottom right of the photo. Torsbo, Bohuslän, Sweden.

There are also examples of horns being depicted in a way that forms a complete circle, for example, Vrångstad in Bottna parish, Bohuslän and in Alvhem, Västergötland (Figure ). Moreover, there are several examples of cup-marks being placed between the horns which further emphasizes the circular character of the composition.

Figure 9. Cows with horns, the horns are displayed differently, either in a naturalistic way or as a circle with a dot. Alvhem, Skepplanda, Västergötland, Sweden. Photo: Tomas Persson.

The combination of ships and circles is a recurring motif, both on rock-art panels and on decorated metalwork. In rock art various kinds of circle images, such as cup-marks and wheel-crosses, occur in close connection to ships. The position varies, one or several circle images can occur aboard, or in close association, to the ship. Circular images may also be part of the ship itself, being incorporated as a decorative element onto the hull. A good case in point is the carving at Alvhem in Västergötland (see figure ). On this panel, circle images are found incorporated in the aft and stem of some of the ships (Rex Svensson, Citation1982, pp. 90–91). Cup-marks and circle images also appear in close connection to four of the ships at the panel. Another example is Lökeberget i Bohuslän (Figure ) where there are close spatial associations between a ship and a wheel-cross, a hollowed out circle image and two cup marks.

Figure 10. Close spatial association between circle images and ships. Lökeberg, Bohuslän, Sweden. Photo: Andreas Toreld. SHFA bild id 5158.

The ship-circle combination stands out very clearly in those cases when a circle is attached to a ship by a line. In these instances, the circle is often on top of the ship as if it is placed on a pole, thus pointing out a very strong relationship between the two images (Almgren, Citation1927, pp. 8–14; Kaul, Citation1998, pp. 195–199).

Combining ships and circles is also common in decorated metalwork. According to Flemming Kaul, one or several circle images appear in connection to ship images in 126 instances on decorated Danish metalwork (Kaul, Citation1998, pp. 195–199).

So far, we may conclude

1. Ships and cows are often combined

2. The ship images and the circle image are a recurring combination

3. The cow’s horns often take the shape of an almost complete circle image.

At the backdrop of this, we will now continue to analyse certain kinds of ship-cow images in terms of being ambiguous images which, depending on the station point, will refer to different kinds of icons.

3.2. The cow as an ambiguous image

Now, we will return to the assumption that some images of cows can be comprehended either as a cow or as a ship—i.e. they are ambiguous. In order to consider this argument, we need to briefly discuss how images on the panels are perceived from different angles using the concept of station points.

Western paintings typically presuppose a singular viewing position from which the composition ideally should be perceived. Liliana Janik (Citation2014), inspired by the work of the perceptual psychologist Margaret Hagen, refers to this as a station point: “Station points are determined by the direction in which the artist was looking at the object or landscape and conveyed the representation of it onto canvas or rock. Understanding this allows us to follow the artist in how to look at the picture, as if we were being guided by historical and pre-historical artists as we view the creations” (Janik, Citation2014, cf. also Hagen, Citation1986).

Here we are interested in the occurrence of several station points in one display of images. In fact, rock carvings may consist of compositions pointing into several different directions, from 0 degrees to 360 degrees, including several station points in one and the same composition. These might well be carved by the same rock art maker at one point in time, or by another rock art maker at another point in time. When multiple station points are represented on rock art panels, the scenery is possible to view and comprehend from several positions. The more horizontal a rock surface is, the more likely it seems that variations in station points occur, reflecting the fact that there often are no natural up- or downsides on such surfaces. The complete absence of a dominant station point would then allow for free and irregular movements across the panels. An implication of this is that when using one station point to comprehend an image, nearby images may be viewed upside-down. Thus, an image will look different depending upon from which direction the viewer is making the observation. Hence, it would be possible for the rock art maker to use two different station points in order to compose two different motifs out of the same carving.

This is, in fact, what can be seen in many of the images depicting cows, because depending upon the station point, they may represent either a cow or a ship. In several cases, moving to the opposite side of the cow’s body will turn the body into a hull and the legs and tail will turn into crew strikes. On these occasions, the horns get the shape of an almost enclosed circle which is attached to the boat. As noted above, the ship and the circle, is a well-known combination in south Scandinavian rock art and decorated metalwork.

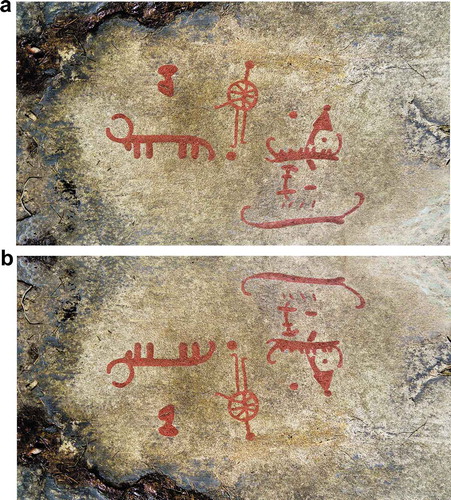

However, not all cows are transformed into ships when looked at from the opposite angle. When the cows are realistically designed, with a large ample body, (for example, the Aspeberget site, Figure ) it makes less sense to look at them from another station point. It seems to be only when the cows are schematically displayed, i.e. when the body, the legs and the tail are made of straight or slightly bent lines, that they can be transformed into ships when viewed from the opposite side. This effect is demonstrated clearly at the Torsbo site where the cows turn into small ships when viewed from the opposite direction (Figure ). It should be noted that Torsbo is just one of several such examples (See Appendix A). Arguably, the rock art maker creating these images was aware of the phenomenon and designed the cows purposely in order to make them look like boats with a crew when viewed from the opposite side. Thus, depending on the station point these cow images could either be a cow where the horns resemble a circle, or a ship associated to a circle.

Figure 11. (a,b) The same motif viewed from two different stations points differing 180 degrees. On top, the carving displayed as a cow and below the same carving displayed as a ship. Torsbo, Bohuslän, Sweden. Photo: Peter Skoglund.

In Bronze Age research it is often argued that circle images are representations of the sun (for example, Kaul, Citation1998, pp. 263–265). Accepting this premise, we are dealing with a sequence of at least three icons involving the cow, the ship and the sun. The sun is in both cases an iconic sign, since the shape of the circle is similar to the shape of the sun, but it also depends on convention, since such a circle could be any round object, say a full moon (Sims, Citation2006). This highlights the fact that there could be no iconic signs without some degree of conventionality. Given that there are crew strikes aboard the ships, a fourth icon involving a high degree of conventionally could be added, namely a group of humans.

In fact, all these four components are clearly depicted at a panel in Alvhem (Figure ) where circle images are incorporated into the ship images, or are situated around the ships. On the panel there are three cow animals two of them having perfect circular horns with a small cup- mark incorporated into the center of the circle. Associated to one of the cows is a human seemingly holding the cow in its tail. Furthermore, the human is attached to a circle by a line. In Alvhem a human, circles, ships and cows are individually depicted; while at Torsbo (Figure ) all these components are condensed into one image, that could either be seen as a cow with circular horns or a ship with a crew of humans which are attached to a circle.

3.3. Implications

Our analysis suggests that a selection of images in the rock art of southern Scandinavia were deliberately made as ambiguous images, alluding to established associations between the components of those images in a wider pictorial culture. This means that the same image would resemble different objects, or agents, depending upon the station point; furthermore, different icons could be extracted from the same image, and a previously highly iconic feature could take on a more conventional meaning in its new context, as exemplified above. The recurrent pattern, i.e. that this observation can be found in several instances, favors the idea that it is not a random situation, but a deliberate choice made by the rock art maker (Appendix A).

Now we want to return to the questions of how ambiguous figures were composed, and their possible functions.

Concerning the first question our analysis demonstrates that rock art artisans were aware of, and used, embedded images—i.e. one or several figures can be perceived within one image, and do not share all contour outlines with the other figures in the larger image material. In our material this is a relevant definition for the case when the cows’ horns can either be regarded as horns or as a circle image (i.e. a sun). The other way of composing ambiguous images was to use two station points where one and the same image would represent two different icons depending on the position of the viewer.

Concerning the possible functions of ambiguous images, we want to highlight that the dual meaning of ambiguous images represents a transformation, and the reason for aiming towards this effect could be that the pictures held narrative functions, i.e. a story that acted as background information that made the transformation understandable. Even the transformation itself can be seen as narrative. The change from ship to cow and back to ship again would qualify as a narrative in its most basic form as a transformation of one state of affairs to another. Stories often occur in abbreviated form, as proverbs, or as “gists”. People tend to not remember specific narrations of stories, but rather the gist of them. Thus, condensed pictorial compositions can remind people of possible gists, which can be extended into larger narratives (Ranta et al., Citation2019).

The ambiguous figures discussed in this paper could have functioned in this way—i.e. as a gist with four building blocks from which a larger narrative could be told: the ship, the cow, the circle, and a ship crew. Ambiguous figures could then be defined as “single events and implied action schemas, understood as changes of state, usually performed by (several or single) agents” (Ranta et al., Citation2019, p. 15). The intent behind making an ambiguous image instead of separate images, could also have been to create a sense of surprise, which is not only a defining hallmark of a good story, but also the reason as to why we enjoy when one image switches into another in Figures and . This rewarding experience of discovery and surprise might in fact have motivated the onlooker to move around the panel and view it from different station points. That said, we cannot know for sure if time, another cornerstone in narrativity (especially in verbal narratives), was intended to be explicit in Bronze age visual rock art. It could be that the intention with the ambiguous figures was to draw the viewers’ attention to the polymorphous narratives embedded in the figure, with its inherent “movement from perspective to perspective instead of from event to event” (Sass, Citation1992, p. 34). In that sense, we may perhaps regard the ambiguity in this specific rock art as a device of mediating a form of transformations from one state or stage to another. Regardless, we may on good grounds assume that the complexity of the ambiguous figures gives them a narrative quality, in terms of pointing at possible transformations more or less relying on our sense of time as we experience it in our ordinary life.

In conclusion, with the aid of cognitive psychology and semiotics we have demonstrated that there are ambiguous images in south Scandinavian rock art, and suggest that these could be understood as being part of pictorial narratives.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anna Cabak Rédei

Anna Cabak Rédei has a PhD in (Cultural) Semiotics and is a Reader in Cognitive Semiotics at Lund University, Sweden. Her interests include cognitive, cultural and pictorial semiotics, film and history. Peter Skoglund is a lecturer and Reader in Archaeology at the Linnaeus University in Kalmar, Sweden. He has published extensively on Scandinavian rock art and his research interests include rock art chronology and the relationship between rock art sites and the wider landscape settings. Tomas Persson is a lecturer and PhD in Cognitive Science at Lund University, focusing on representational abilities as well as social synchronization in great apes and other animals. He has previously worked on animals’ and human infants’ understanding of pictures. The present work has been conducted as part of the cross-disciplinary project Storytelling in Rock Art, financed by the Swedish Research Council (Grant no. 2016–01288).

References

- Almgren, O. (1927). Hällristningar och kultbruk: Bidrag till belysning av de nordiska bronsåldersristningarnas innebörd. Wahlström & Widstrand.

- Bertilsson, U. (1987). The rock carvings of northern Bohuslän: Spatial structures and social symbols. Stockholm University.

- Coles, J. (1999). The Dancer on the Rock; record and analysis at Järrestad, Sweden. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 65, 167–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0079497X00001985

- Danesi, M. (2004). Studies in linguistic and cultural anthropology. In M. Danesi (Ed.), A basic textbook in semiotics and communication (3rd ed.). Canadian Scholars’ Press.

- Fibonacci. (2007). The Kanizsa triangle. Wikimedia Commons. (Original published 1979 by G. Kanizsa). Retrieved October 30, 2019, from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/55/Kanizsa_triangle.svg/768px-Kanizsa_triangle.svg.png

- Goldhahn, J. (2004). Mångtydighetens tydlighet. In G. Milstreu & H. Prøhl (Eds.), Bilden som arkeologisk källa (pp. 121–135, pp. 205–208). Gotarc Serie C. Arkeologiska Skrifter 50.

- Goldstein, E. B. (2010). Sensation and perception. Wadsworth.

- Hagen, M. (1986). Varieties of realism. Geometries of representational art. Cambridge University Press.

- Hald, M. (1972). Primitive shoes: An archaeological-ethnological study based upon shoe finds from the Jutland peninsula. Arkæologisk-historisk række, 13. National Museum of Denmark.

- Hauptman, K. (2002). Bilder av betydelse: Hällristningar och bronsålderslandskap i nordöstra Östergötland. Stockholm University.

- Hodgson, D., & Pettitt, P. (2018). The origins of iconic depictions: A falsifiable model derived from the visual science of Palaeolithic cave art and world rock art. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 28(4), 591–612. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095774318000227

- Janik, L. (2014). Seeing visual narrative: New methodologies in the study of prehistoric visual depictions. Archaeological Dialogues, 21(1), 103–126. https://doi.org/10.1017/S138023814000129

- Jastrow, J. (1899/2006). ‘The duck/rabbit illusion’. The mind’s eye. Popular Science Monthly, 54, 299–312. Retrieved October 28, 2019, from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Duck-Rabbit_illusion.jpg#filehistory

- Kaul, F. (1998). Ships on bronzes: A study in Bronze Age religion and iconography. National Museum.

- Leopold, D. A., Wilke, M., Maier, A., & Logothetis, N. K. (2002). Stable perception of visually ambiguous patterns. Nature Neuroscience, 5(6), 605–609. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn851

- Lindstrøm, T. C., & Kristoffersen, S. (2001). Figure it out! Psychological perspectives on perception of migration period animal art. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 34(2), 65–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/00293650127468

- Ling, J. (2008). Elevated rock art: Towards a maritime understanding of Bronze Age rock art in northern Bohuslän, Sweden. University of Gothenburg.

- Ling, J. (2013). Rock art and seascapes in Uppland. Oxbow Books.

- Ling, J., & Rowlands, M. (2015). The ‘Stranger King’ (bull) and rock art. In P. Skoglund, J. Ling, & U. Bertilsson (Eds.), Picturing the Bronze Age (pp. 89-104). Oxbow Books.

- Ljunge, M. (2015). Bortom avbilden: Sydskandinaviska hällbilders materialitet. Stockholms universitet.

- Malmer, M. P. (1981). A chorological study of North European rock art. Vitterhets-, historie- och antikvitetsakademien.

- Marstrander, S. (1963). Østfølds Jordbruksristninger – Skjeberg. Universitetsforlaget.

- Nilsson, A. (2014). Affekter, relationer, operationer – Grunden för Homo psychicus. Mot en människoteori i dynamiken mellan det analoga och det digitala. Östlings Bokförlag Symposion AB.

- Nilsson, P. (2017). Brukade bilder: Södra Skandinaviens hällristningar ur ett historiebruksperspektiv. Stockholms universitet.

- Peirce, C. S. (1894/1998a). What is a sign? In C. J. W. Kloesel & N. Houser (Eds.), The essential Peirce, vol II (pp. 5–26). Indiana University Press.

- Peirce, C. S. (1903/1998b). Sundry logical conceptions. In C. J. W. Kloesel & N. Houser (Eds.), The essential Peirce, vol II (pp. 267–288). Indiana University Press.

- Peirce, C. S. (1903/1998c). Nomenclature and divisions of triadic relations, as far as they are determined. In C. J. W. Kloesel & N. Houser (Eds.), The essential Peirce, vol II (pp. 289–299). Indiana University Press.

- Preucel, R. W., & Bauer, A. A. (2001). Archaeological pragmatics. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 34(2), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/00293650127469

- Ranta, M., Skoglund, P., Cabak Rédei, A., & Persson, T. (2019). Levels of narrativity in Scandinavian Bronze Age petroglyphs. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 9(3), 497–516. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774319000118

- Rédei, A. C., Skoglund, P., & Persson, T. (2018). Applying cartosemiotics to rock art: An example from Aspeberget, Sweden. Social Semiotics, 29(4), 543–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2018.1488338

- Rex Svensson, K. (1982). Hällristningar i Älvsborgs län: En inventering av samtliga kända hällristningar i Dalsland och Göta älvdalen. Älvsborgs länsmuseum.

- Rubin, E. (1915/2005). Vase/face illusion. Original published in Synsoplevede Figurer [‘Visual Figures’]. Retrieved October 28, 2019, from https://da.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edgar_Rubin#/media/Fil:Facevase.png

- Sass, L. A. (1992). Madness and modernism. Insanity in the light of modern art, literature, and thought. Basic Books.

- Sims, L. (2006). The ‘solarization’ of the moon: Manipulated knowledge at Stonehenge. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 16(2), 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774306000114

- Skoglund, P. (2016). Rock art through time: Scanian rock carvings in the Bronze Age and earliest Iron Age. Oxbow Books.

- Skoglund, P., Nimura, C., & Bradley, R. (2017). Interpretations of footprints in the Bronze Age rock art of south Scandinavia. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 83, 289–303. https://doi.org/10.1017/ppr.2017.2

- Sonesson, G. (1989). Pictorial concepts. Lund University Press.

- Sonesson, G. (2013). The natural history of branching: Approaches to the phenomenology of firstness, secondness, and thirdness. Signs and Society, 1(2), 297–325. https://doi.org/10.1086/673251

- Tilley, C. (1991). Material culture and text. The art of ambiguity. Routledge.

- Treisman, A., & Gelade, G. (1980). A feature integration theory of attention. Cognitive Psychology, 12(1), 97–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(80)90005-5

- Van Sommers, P. (1991). Where writing starts: The analysis of action applied to the historical development of writing. In J. Wann, A. M. Wing, & N. Sövik (Eds.), Development of graphic skills. Research, perspectives and educational implications (pp. 3–38). Academic Press Limited.

- Verbeek, G. (1904/2005). A fish story. The New York Herald. Retrieved October 18, 2019, from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Verbeek-rocanoe.gif

- Welinder, S. (1974). A study on the Scanian rock carvings by quantitative methods. Meddelanden Från LUHM, 1973-74, 244–275.

Appendix A:

Sites displaying ambiguous images

Information extracted from Swedish Rock Art Research Archives’ (SHFA) online database: www.shfa.se RAÄ no refers to the Swedish National Heritage Boards register of ancient monuments (Fornsök).