Abstract

Since the introduction of Shakespeare to Iranians in the late nineteenth century through stage productions, his work has been positively received and many of the plays have also been adapted in Persian literature and theater. In contemporary Iranian drama numbers of adaptations of canonical works of Western literature, including Shakespeare, have increased substantially, largely because they offer an ideal platform for reflecting on sociocultural and political problems of present-day Iran. A daring playwright, Hamid-Reza Naeemi, whose theater shows a strong inclination to adapting Western masterpieces, adapts Shakespeare’s Richard III (ca. 1593) in his modernized reworking of the play entitled Richard, in order to express disapproval of undemocratic government system and thorny sociopolitical issues in modern Iran, particularly the era of the Pahlavi State (1925–79). Through intertextual analysis and adaptation theory formulated by Linda Hutcheon, this study analyzes how Shakespeare’s tragic drama has been adapted by Naeemi to shape his dissident discourse to critique the state power and restriction of freedom in the above play. It also recontextualizes and analyzes Shakespeare’s tragic theme of the rise and fall of a tyrant in Naeemi’s reflection of the overthrow of the Pahlavi Dynasty in winter 1979.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Shakespeare has been adapted and reworked by many authors around the globe. There are various reasons for adapting and appropriating Shakespeare’s plays, including the aesthetic and the sociopolitical. In modern Iran, Shakespeare was first introduced in the late nineteenth century through stage performances and later translations. From then on, many Iranian playwrights have engaged in adapting and appropriating Shakespeare’s plays to achieve their desired ends. Iran’s 1979 Revolution, which overthrew the Pahlavi Monarchy, influenced Shakespeare adaptation greatly, and several playwrights reworked Shakespeare’s major plays. A striking case is the Iranian playwright and theater director Hamid-Reza Naeemi that in his 2018 play Richard adapted Shakespeare’s Richard III. Naeemi uses Shakespeare to question dictatorship in modern Iran and to reflect on socioeconomic problems that Iranians face today. This article explores the adaptive features and oppositional stance in Naeemi’s Richard through intertextual analysis and adaptation theory advanced by Linda Hutcheon.

1. Introduction

Shakespeare’s composition of Richard III was concurrent with the period of “extreme hardship” in England of the 1590s (Heinemann, Citation2003, p. 170). Problems like poverty, peasant discontent caused by bad harvests, and political tension with the Catholic nations, Spain in particular, loomed large in the Elizabethan England. The reflection of these deplorable conditions can be seen in the second act of Richard III, where two citizens are worried about Richard’s cunning plans and viciousness. Richard is a multi-faced figure in the play, Mehl (Citation1999) argues, that playacts, seduces, and intrigues. In Richard III, Shakespeare stages the rise and fall of an Elizabethan Machiavel who uses his deformed body to pursue his evil intentions. Pierce (Citation1971) maintains that “destruction of the family, corrupted inheritance, and tainted marriage pervade the language and action of Richard III” (p. 93). The play has been adapted many times for television and cinematic productions in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The well-known ones are Richard III (1955) directed and produced by Laurence Olivier, and Richard III (1995) directed by Richard Loncraine. Al Pacino’s Looking for Richard (1996) also is another important adaptation in which Pacino not only plays Richard in some of the scenes, but also explores the relevance of Shakespeare’s drama in today’s culture. BBC Television Shakespeare was produced between 1978 and 1985, with Richard III directed by Jane Howell. The seven-episode adaptations of the Henry and Richard play, under the name of The Hollow Crown, was produced between 2012 and 2016; the Richard III episode was directed by Dominic Cooke. In the Middle East, one notable adaptation is Sulayman Al-Bassam’s Richard: An Arab Tragedy (2007) which reflects on the Iraq War (2003) and contemporary Arab politics in its Arabic setting to explore issues like power, corruption, and political disillusionment in the Arab world.

In contemporary Iranian drama, the reception of Richard III has been positive since its initial translation into Persian by Reza Baraheni in 1964. Since then, the play has been retranslated by different Iranian translators, which can be indicative of the play’s significance for Iranian audience. Among the prominent theater actors and directors, Davoud Rashidi showed his grand passion for performing Richard III in Persian in 1967 and 1999. He also acted in Philip Monta’s production of the play between 1968 and 1972. However, Safar (Citation2017) quotes from Rashidi that because of the official censorship in Iran, he was not able to perform the play again in the 1970s: the theme of removing a ruling tyrant was politically contentious during the reign of the Pahlavi dynasty (1925–79). In addition to Rashidi’s performances, another important stage production is Atila Pesyani’s Richard III in 2011 in Iranshahr Theater Hall. His production was positively received by theater critics and audiences, and was awarded the best stage performance of the year at Fajr International Theater Festival in the same year. In 2018, the celebrated theater director, actor, and playwright Hamid-Reza Naeemi, who has always expressed his avid interest in adapting Western canonical texts, appropriated and staged Richard III, entitled Richard with the regnal number from the original notably omitted. His theatrical adaptation was performed in July and August in Tehran’s Vahdat Opera Hall, and like Shakespeare’s original text, Naeemi lays emphasis on the necessity of removing a tyrant and ending his “autocracy” (Dunn, Citation1996, p. 20). Most notably, this adaptation presents a sociopolitical critique of the Iranian society, and a criticism of undemocratic governments in modern Iran. It is likely that the Arab Spring in 2010–2011 influenced Naeemi’s politics of adaptation because these protests and revolts are aimed at removing dictatorial regimes across the Middle East and North Africa (Eposito et al., Citation2015). Esmailpour (Citation2018) celebrates Naeemi’s creative use of the characterization based on Shakespeare’s original figures and addition of new ones to his dramatis personae, namely, the three Tailors. It can be argued that Naeemi’s Richard pursues dual purposes: a political critique of dictatorship that has caused the preservation of the oppressive social order in modern Iran, and a social critique of poverty, unemployment, and violation of personal freedom.

Stage productions and (re)translations of Shakespeare’s plays from the late nineteenth century onward exerted a major impact on Shakespeare’s reception and adaptations in contemporary Iranian theater. This article explores this phenomenon by offering a case study of a notable political adaptation of Shakespeare’s Richard III by Hamid-Reza Naeemi in his play Richard (Naeemi, Citation2018). It argues that Naeemi’s drama questions the dictatorial governments and limited political freedom in modern history of Iran in conjunction with reflecting on socioeconomic problems of contemporary Iran. The study also analyzes the scope of dissidence and the way in which Shakespeare’s tragic drama has been adapted by Naeemi in order to reflect on the downfall of the Pahlavi monarchy and voice his disapproval at Iran’s recent state of affairs such as economic problems and oppressive social order. Before examining Naeemi’s Richard, I would first like to discuss briefly the theory of adaptation and its intertextual aspects.

2. Adaptation as intertextual interaction

Following Ferdinand de Saussure’s theory of how: stress on the systematic features of language establishes the relational nature of meaning and thus of texts” (Allen, Citation2000, p. 2), Mikhail Bakhtin’s The Dialogic Imagination (Bakhtin, Citation1981) forges a link between the concepts like author, text, reader, society, and history. In Bakhtin’s view, every literary text contains multiple discourses and dialogues that make the text a form of “hybrid construction” (p. 304). Literary texts, Bakhtin posits in Speech Genres and Other Essays (Bakhtin, Citation1986), do not simply follow, correct, or rewrite previous texts; rather, they inform and are informed by those preceding texts: “Each utterance is filled with echoes and reverberations of other utterances” (p. 91). Bakhtin contends that every utterance is dialogic whose meaning is contingent upon the previous utterances and “how they will be perceived by others” (Allen, Citation2000, p. 19). His discussion of intertextuality influences and informs Julia Kristeva in Revolution of Poetic Language (Kristeva, Citation1984) to go on to assert that a text is a form of cultural textuality, always shaped by transformation of other textual utterances and structures (p. 65). For her, the term intertextuality, or transposition, “denotes this transposition of one (or several) sign system(s) into another” (pp. 59–60). Deploying the same Bakhtinian line of argument, Kristeva deduces that,

lf one grants that every signifying practice is a field of transpositions of various signifying systems (an inter-textuality), one then understands that its “place” of enunciation and its denoted “object” are never single, complete, and identical to themselves, but always plural, shattered, capable of being tabulated. ln this way polysemy can also be seen as the result of a semiotic polyvalence—an adherence to different sign systems. (p. 60)

The arguments of Bakhtin and Kristeva concerning intertextuality lay the theoretical groundwork for the field of adaptation studies which was brought to prominence by Linda Hutcheon whose groundbreaking monograph A Theory of Adaptation (Hutcheon, Citation2013) has enriched this field of study. Intertextuality suggests a cornucopia of preceding texts informing textuality, and this establishes a correlation with the central thrust of Hutcheon’s conception of adaptation as an intertextual and intercultural product.

Hutcheon’s A Theory of Adaptation is one of the most influential texts on the subject of adaptation, theorizing, and developing the field of adaptation studies. In it, Hutcheon questions the traditional understanding of adaptation, i.e. the attribution of being “inferior,” “secondary” or “parasitic” to adaptation (169). For Hutcheon, every adapted text constitutes processes of (re)interpretation, production, and reception involving pleasure, surprise, and novelty (p. 7). Following Bakhtin and Kristeva, Hutcheon moots that “adaptation is a form of intertextuality” (p. 8), having a textual relationship with the original text. By focusing on promoting adaptation theory, Hutcheon outlines reasons such as the aesthetic, the cultural, and the political that adapters attempt to create adaptive works (pp. 73–74). Form the cultural perspective, context is of great significance for adaptation because it is a means of attracting audience; accordingly, from the discussion of context, the term indigenization emerges as a form of adapting the features and elements of the original text with that of the adapted work. Hutcheon posits that indigenized works are hybrid bearing cultural principles of both original and adapted contexts (p. 151). Related to context is the anthropological concept “indigenization” that Hutcheon employs to specify that authors (adapters) “pick and choose what they want” in order to “transplant to their” literary heritage (p. 150). For literary adapters, to indigenize means to conform the tradition, culture, and history of the original text to domestic audience whose culture, religious faith, gender norms, and sociopolitical standing wield marked influence over the way literary works are going to be adapted. Given this consideration, adaptation is an intercultural and intertextual production that establishes a “dialogue between the society in which the works, both the adapted text and adaptation, are produced and that in which they are received, and both are in dialogue with the works themselves” (p. 149).

3. Shakespeare in contemporary Iranian Drama

Looking into the history of Iranian theater would indicate that the adaptation of Shakespeare’s plays has a long tradition among Iranian playwrights and directors. One of the main reasons for the ubiquity of Shakespearean adaptation is likely the potential it offers for reflecting on and critiquing the respective contemporary social and political circumstances (Litvin et al., Citation2017, p. 97). According to Sedarat (Citation2011), there is a direct relationship between sociocultural and political conditions and the adaptation of Shakespeare’s plays in modern Iranian drama. For example, the Constitutional Revolution (1905–11) was a significant movement toward limiting the power of monarchy and establishing a real nation-state founded on democratic principles (Axworthy, Citation2013), and it played a crucial role in introducing Western canonical authors as it “inspired a new translation wave” among Iranians (Litvin et al., Citation2017, p. 100). The Constitutionalists, many of whom had acquired their qualifications from European academic institutions, launched newspapers and periodicals that helped to spread Western literary forms, styles, and texts among Iranians. It is very likely, Bozorgmehr (Citation2015) observes, that the presence of the Britons in Qajar court in the nineteenth century introduced Shakespeare to Iran. The first stage productions of Shakespeare appeared in the 1880s, and the first translations of Shakespeare were produced by the turn of the century. The first Persian translations of Shakespeare appeared in the twentieth century, though it seems likely that translations of Shakespeare have been made prior to 1900, there is no conclusive evidence in this regard as none of these early translations seem to survive or be documented (Horri, Citation2003). Quintessential examples are Hosseinqoli Saloor’s The Taming of the Shrew (1900), Mirza Abolgassem Khan Qaragozlu’s Othello (1914) and The Merchant of Venice (1917). Horri (Citation2003) states that after the Constitutional Revolution, more translations of Shakespeare were produced and plays like Othello, Hamlet, King Lear and The Merchant of Venice was retranslated several times.

During the era of the Pahlavi Monarchy (1925–79), the number of translations and performances of Shakespeare’s works increased substantially, although due to limited political space and the absence of democratic principles in the Pahlavi era (Katouzian, Citation2003), political readings, and interpretations of Shakespeare were discouraged. Mirsepassi (Citation2000) writes about a central paradox in the overall policy of the Pahlavi monarchs: in conjunction with their endeavor to transform Iran’s educational, social, and economic systems through promoting literacy, establishing academic institutions, and generally modernizing the country, they set up a system of police surveillance in order to make sure that “only politically safe views” could be expressed (p. 190). Shakespeare productions during this era were largely limited to teleplays and occasional stage performances, like the theatrical productions of Davoud Rashidi: Richard III in 1967 and A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1970. However, only a handful of playwrights tried their hands at adapting Shakespeare play-texts themselves in that period. A prominent playwright, Akbar Radi (1939–2007), appropriated Hamlet’s melancholic and hesitant state of mind in his grotesquely comic Hamlet with Seasonal Salad (1977) to dramatize the disappointment and failure of Iranian intellectuals, and to show the characters as a group of “puppets” under control of the discursive state power (Massoudi & Behrouzinia, Citation2016, p. 112). Shakespearean elements and features have been used and adapted by Iranian playwrights during the Pahlavi era. To illustrate, Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi’s An Eye for an Eye (1971) adapts Measure for Measure (1604) in a comic setting to question the notion of justice in the Iranian society.

The downfall of the Pahlavi State in 1979, due to the mass uprisings which has become known as the Islamic Revolution, resulted in an exponential increase in the publication of translated texts and adaptations of Western literary masterpieces across different media (Haddadian-Moghaddam, Citation2014). Eventually, the Persian translation of all Shakespeare’s comedies and tragedies was published by the celebrated economist and literary translator Aladdin Pazarghardi (1913–2004) in his two-volume set in 2002. Iran’s political ups and downs in the twentieth century had a significant effect on the writing practice of contemporary Iranian authors; to some degree, they determined and caused new trends in literary and theatrical productions. For example, the Student Protests of 1999 in Tehran over the State’s closing down the reformist newspaper Salam (Hello) (Yaghmaian, Citation2012), which gave rise to a series of political writings, also inspired the production of several dramatic and cinematic adaptations of Shakespeare, particularly the plays that deal with the rise and fall of tyrants. Such politically charged adaptations typically aim at offering sociocultural and political critiques of important problems of contemporary Iran. The phenomenon of Shakespeare adaptations in Iran may be akin to the argument of Stříbrný (Citation2000) in his critical study of Shakespeare adaptations and interpretations in Eastern Europe where Shakespeare was read politically and used for “exposing the whips and scorns of time” (p. 1), because there were political discontent and undemocratic governmental regulations.

In 2000, the collaboration of Atila Pesyani and Mohammad Charmshir, celebrated theater directors and playwrights, resulted in allegorically adapting King Lear, Hamlet, and The Tempest in their Three Rewritings of Shakespeare. Their reworkings are of importance because, for Pesyani and Charmshir, representations of defiance and chaotic situations are reflection of the present-day Iran. These adaptations, Azimi and Moosavi (Citation2019) argue, present “subtle sociopolitical criticism of the abuse of power and social injustice” (p. 155). Another major adaptation is Charmshir and Mohandespour’s rewriting of Macbeth in 2001 that showcases a struggle for power and starving people roaming the stage to depict the State’s indifference to people’s struggle for basic subsistence. Two other famous adaptations that present social critique are Rouzbeh Hosseini’s When the Ghost of Lear Asks Joker for a Day Off (2016) and Davoud Fathali-Beygi’s Taming of the Shrew: A Minstrel Show (2017). In the former, Hosseini offers a collage of Shakespeare’s King Lear and the film The Dark Knight (2008) directed by Christopher Nolan to stage Lear’s confrontation with Joker, Batman’s nemesis in DC comics of the same name. This play enters a world of “forever darkness” and callous indifference toward humanity in contemporary Iranian social life (Hosseini, Citation2016, p. 14). The latter, originally staged in 2001 yet printed sixteen years later, appropriates Shakespeare’s comedy to question the long-established conventions on marriage and family connections in Iran. To conclude, many of Shakespeare adaptations in contemporary Iranian drama attempt to voice criticism of sociocultural and political problems of contemporary Iran.

4. The theater of Hamid-Reza Naeemi

A brief glance at the playwriting career of Hamid-Reza Naeemi reveals his penchant for literary adaptations of acclaimed works of fiction and drama by world-renowned authors. He rose to prominence through his stage adaptation of Macbeth in 2005, won a prestigious award at Fajr International Theater Festival in the same year. In his production, there are no Witches and prophecies of Macbeth’s enthronement. The play presents a bewildered Macbeth who is caught in a chaotic situation and forced to act against the legitimate King Duncan. The performance draws attention to the interplay of power, politics, and conspiracy in a crisis-stricken society, much resembling Iran in the early years of the twenty-first century. Overall, his other theatrical productions such as Socrates (2013), an adaptation of Maxwell Anderson’s Barefoot in Athens (1951), and Assassination (2015) were highly successful at the box-office and positively received by theater critics like Nasiri (Citation2014) who praises the performance of Socrates and writes about the play’s focus on intellectual life and activity of Socrates and its relevance for contemporary Iran.

Naeemi’s employment of choral singing and group dance, which is one of the typical features of his stage productions, has frequently stirred up controversy in the Iranian media. A notable case is the use of female soprano and choral dance in the performance of his commercially immensely successful play Socrates in 2014, which the daily 20:30 News Bulletin of IRIB TV 2 censured severely for its staging of music, singing, and dance because these are against Iranian constitutional laws. According to Article 4 of Iran’s Constitution, all forms of laws, e.g., military, civil, criminal, financial, economic, administrative, cultural, military, political must be based on Islamic principles. Similarly, all forms of the arts, including cinema, theater, and literary compositions must abide by the Islamic rules; whence, representation, and articulation of sensitive subjects concerning “love, affection, and any association thereto; wine, drunkenness, and bars; descriptions of women’s beauty; descriptions of sexual organs; gambling; unconventional words and expressions; suicide; and music” are all subject to censorship and, in some extreme cases apprehension of the artists (Haddadian-Moghaddam, Citation2014, p. 122). Another example of theater censorship is Vahid Rahbani’s stage production of Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler in 2011 which was officially banned after the run of a few nights, due to the play’s indecent material.

Dramatization of historical events and figures is another important feature of Naeemi’s theater practice. Staging history in a play like Assassination (2016), which delves into the Arab history and stages the assassination of Ali ibn Abi Talib (601–61)—the fourth Caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate—is a complex process of historical re-construction to place unofficial accounts and narratives in the foreground; in this way, the playwright can cast doubt on the authenticity of historiography and examine “political implications of particular historical forms and structures” (Malpas, Citation2005, p. 97). Explorations of the past can help the playwright to interpret and reflect on how and why specific forces of history influence individuals. Foregrounding the inner conflict of the main character ibn Muljam, the assassin of Abi Talib, who had vowed to murder the Caliph, the play focuses on the inner thoughts of ibn Muljam and narrates the historical event from his point of view. To paraphrase Rabey (Citation2003), history is the site that various ideologies, ambiguities, conflicting attitudes converge. Naeemi’s re-vision of past events and figures is his technique to represent indirectly contemporary Iranian society and politics. Naeemi’s theater has been simultaneously influenced by and affects modern Iranian drama. His avid interest in staging and exploring important social, political, and historical issues, as well as the adaptive features of his plays, can be considered his major contribution to contemporary Iranian playwriting.

5. Richard: the will to deceive, improvise, and kill

Through adapting Shakespeare, Naeemi actually establishes a cultural link between the sixteenth-century England and present-day Iran. The main reason that Naeemi has engaged in adapting Richard III is the political reading that the play invites. Richard III is an exploration of issues including a ruling tyrant, hegemonic power, poverty, Machiavellism, female protest over patriarchal society, and the desire for freedom from a tyrant (Wells, Citation1986). In the wider context, similar to Naeemi’s adaptation, Al-Bassam’s Richard: An Arab Tragedy (2007) indigenizes Shakespeare’s play to reflect on grave issues concerning the Arab societies, especially the war-torn Iraq. To use Hutcheon (Citation2013), both Al-Bassam’s and Naeemi’s adaptations in a way highlight “canonical cultural authority” of Shakespeare in the Middle Eastern context (p. 93). Such political interpretations of Shakespeare lead to the adapters’ goal of making political interventions in their societies. Looking at Naeemi’s adaptation, its language is colloquial Persian, and this sets it apart from previous Persian performances of Shakespeare, which were usually produced in neutral or formal language. Richard aroused controversy among Iranian entertainment and theatrical circles from the beginning. Lack of support from related official institutions and advertising agencies induced Naeemi’s angry reactions against the advertising agencies under contract of Tehran’s municipality, which is in charge of the cinematic and theatrical advertisements in the country. He remains loyal to the main dramatic events of Shakespeare’s original text; however, he manipulates it to varying degrees in order to pursue his political ends in the context of present-day Iran.

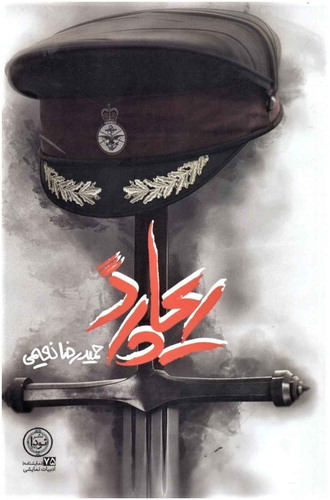

As has been discussed, the addition of the Tailors, for instance, is cognate to the dramatic effect of the Weird Sisters and their prophetic vision in Macbeth. The Tailors embolden Richard to wear elegant military uniforms; their prophecy takes the form of Carlyle’s clothes metaphor that meaning is contingent on situations and relates to “false” systems (Felluga, Citation1995, p. 583). In the adaptation, Richard is not represented as a tragic figure: he is more callous and cunning than his Shakespearean counterpart whose contriteness about his wrongdoings is revealed to the audience at the end. The Iranian Richard never displays remorse; from the outset, the audience recognizes a Janus-faced opportunist, working hard toward reaching his goals: he is a modern-day dictator. Like his Shakespearean counterpart, Richard makes a pact with the audience to reveal his true intentions, and this continues even to his defeat at the end of Naeemi’s drama. In Richard, furthermore, all the actions of dying and killing are presented on stage which turns the adaptation more violent and uncomfortable. This can refer to the incontrovertible fact about the everyday context of “instability and violence” that characterizes the Middle Eastern countries (Cook, Citation2017, p. 3). His adaptation, broadly speaking, is a critique of dictatorship and undemocratic governments in the Middle East, including modern Iran. As Figure shows, the front cover of Naeemi’s print text promotes the idea of adaptation: a peaked cap of a modern dictator is placed on the sword’s hilt. An example of this is the persuasive argument by the Tailors that Richard must wear elegant military uniforms in order to impress the people and also to hide his true intentions. It is also essential to note that Naeemi’s adaptation of Richard III, particularly in an era in Iranian history that is characterized by the re-imposition of US sanctions against Iran and the isolation of the country in this respect, as well as the failed domestic policies on currency value and economy, can be regarded as a skillful evasion from blame and official theater censorship (Atwood, Citation2012). This intertextual maneuver, in fact, draws attention to Shakespeare’s play, and the criticism that the adaptation provokes pointing to the Elizabethan era.

In his adaptation, Naeemi manipulates the Machiavellian Richard. As Rees (Citation2004) comments on the political thought of Machiavelli, “The prince should, whilst retaining the dignity of his position meet with his subjects, display courtesy, and munificence, and entertain the people with shows and festivities” (p. 11). This is not the case in Naeemi’s adaptation: not only does Richard disregard his subjects, but also does he believe in successful rule by expressing that “there is always something to threaten” (Naeemi, Citation2018, p. 13) (All translations of the play are by the article’s author). Here, Richard is very contemptuous of and abhorrent to his subjects; for him, infliction of fear is the key to rule. The beginning of the play is marked with Richard’s maneuver around his own chaos theory (Kellert, Citation1993). He is charismatic and self-assured, and his success in reaching his goals relies on creating conflict, exploiting the situation, and inducing others through reasoning and justification. Unlike Richard’s soliloquy in the beginning of Shakespeare’s play for the purpose of creating a direct dialogue with the audience, in Naeemi’s rewriting, he only engages in conversations with his subordinates, especially the ones under his command like the Tailors and the Assassins, in order to induce them to carry out his nefarious schemes. Naeemi’s clever manipulation of characters’ relationships of the original text can be explained through Hutcheon’s argument that the adapter carries out subtle alterations in order to make the adapted text “suitable” for the domestic context (Hutcheon, Citation2013, p. 7); that is, he initiates the process of indigenization of the original play.

Naeemi’s adaptation foregrounds Richard’s theatricality, which Stephen Greenblatt identifies as a core feature of Shakespeare’s play in his Renaissance Self-Fashioning (Greenblatt, Citation1980), arguing that power improvises, and the improviser seeks to create his “own scenario” (p. 227). Theatricality is one of the essential attributes of many Shakespearean figures like Iago, Hamlet, and Richard III. Such kind of behavior is to deceive others and take advantage of the situation. Richard’s deceptive behavior toward Clarence and his death is a case in point. In the rewriting, as the Tailors measure Richard’s size for making him an elegant new military uniform, Richard commissions two killers to dispatch the brother in the Tower. At the same time, he expresses his admiration for Clarence, appreciates family ties, and starts to mourn (Naeemi, Citation2018, p. 20). The Assassins are baffled by Richard’s contradictory statements, yet they intend to pay no attention since for many there is insurmountable difficulty in obtaining employment, which is clearly meant as a reference to Iran’s high rate of unemployment and job insecurity in the twenty-first century: “You fool! Do you think employment is readily available? I tried hard to find this job for you” (ibid, p. 20). Iran’s economy has worsened after the US withdrawal from the 2016 Nuclear Deal in May 2018. However, mismanagement and economic exploitation can also be identified as other causes of economic and currency crisis in contemporary Iran. In his study of Iran’s negotiation with world powers over its nuclear program, Jett (Citation2018) argues that Iran’s failed domestic policy on economic affairs and adverse impacts of the US sanctions have driven the country’s economy to the brink of collapse.

Naeemi shows the rise of Richard in the first half of the play and lays stress on Richard’s power of inducement to make everyone think and act according to his intentions. However, it is interesting that he has no influence over female characters, who are suspicious and contemptuous of his intentions. Richard also reveals his seduction, as part of his theatricality, in the funeral scene where the grieving survivors of the late Henry participate in the ceremony. Aided by his deformity, Richard wears his impassive mask every time he faces female cursing in the play. He puts much effort into carrying out his plans, and this includes the wooing of Lady Anne that interrupts the priest’s performing the funerary ritual. Throughout the play, he pretends to be religious, and its climax is in the prayer session scene when the Mayor of London approaches him to persuade him to reign over the nation. Strikingly, all the male characters are manipulated and exploited by Richard. Lady Anne too is Richard’s instrument on his path to the throne. She is considered by Richard to be a property of the state because it is her main duty to secure the royal lineage by giving birth to a crown prince. To achieve this goal, Richard tries to obtain “possession of her body” (Rabey, Citation2009, p. 116). On seduction, Greene (Citation2003) contends that seductive behavior includes “a process of penetration” into another’s mind (p. xxii). In this fashion, Richard is an inducer; his adoption of rational explanation and reasoning as justification of his wrongful acts is a constitutive part of his seductive conduct. After the ceremony is left unfinished and the mourners exit the stage, Richard finally wins Lady Anne. However, it is later revealed that Lady Anne’s acceptance of Richard’s marriage proposal is her own play-acting in order to plot revenge. Remarkably, such representation of seduction and the use of seductive language in Naeemi’s drama can be viewed as an act of transgression that challenges conservative structures and views in the Iranian society. Transgression, as Foust (Citation2010) puts it, aims to “cross boundaries and violate limits” (p. 3). Naeemi’s Richard is a play about the violation of individual rights and liberty and of the boundaries of a conservative society by staging group dance, choral singing, and scenes of seduction. However, it is noteworthy to mention that in the performance of Richard dance moves are performed in a way to appear amateur and less exciting, in an attempt to avoid censorship. Following Shakespeare, Naeemi places deformity at the center of the play. Richard celebrates his deformity and puts it to efficient use because it offers him distraction and justification that he is physically disabled and his actions can never be taken seriously. In this way, he is able to secure the permission to transgress normality and be exceptional (Garber, Citation2004). As a result, his involvement with criminal conduct and depravity will be unpunished. The scene ends with Richard smoking over Henry’s coffin, mocking the deceased sovereign: “Make peace with God, Henry [he lights a cigarette]. The sun of York, Shine! … whenever I walk, I’d like to see my own shadow. I’ll never ashame my countenance, my hunchback” (Naeemi, Citation2018, p. 33).

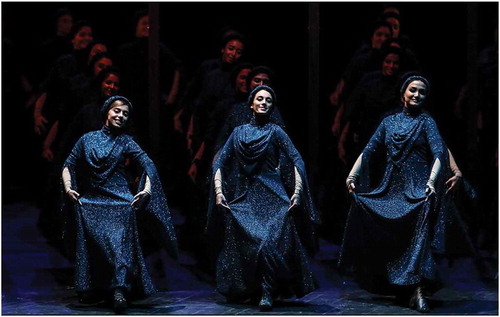

Richard’s play-acting underlines that he is a completely different individual. Even when he has been offered a meat meal at the court’s feast, he refuses to take it on the pretext that he is a vegetarian. To some extent, it can be said that Naeemi places considerable emphasis on Richard’s theatrical and pretentious behavior in order to attribute such qualities to Middle Eastern dictators. To quote Mesquita and Smith (Citation2011), conduct based on pretense and deception is of the trait of dictators and corrupt politicians. Richard only thinks about his personal interests; everyone else is inconsequential and must be executed if they try to take the stand against Richard: “There are still lots of heads to be cut off” (Naeemi, Citation2018, p. 45). The court scene depicts a group of ballet dancers accompanied by contrapuntal music which are quite controversial within Iranian laws—particularly the first nights of Richard’s stage performance, such group dance and music goaded conservative voices, notable among them were several state officials that expressed diatribe against dramatization of dance accompanied by rhythmic music. As Figure illustrates, during the performance of Richard, Naeemi makes use of group dance on stage, especially in the scenes related to court and coronation of Richard, which caused some controversy. To quote Jenks (Citation2003), in a conservative society, especially one like Iran entangled with religious principles, in particular, representation of a female and male ballet dance violates its “recognisable constraint” (p. 26). Looking at Richard’s performance, Figure illustrates a ballet dance scene in which the male and female dancers performing without having any physical contact because a man and a woman must not touch each other unless they are family-related or legally wedded.

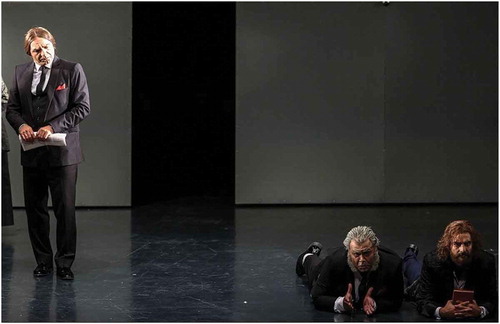

In the play, Richard and Buckingham spread scurrilous rumors to denigrate their opponents by improvising in order to exercise power and control over their subjects. Greenblatt maintains that improvisation is an essential part of self-fashioning process which is also informed by theatricality, and therefore self-fashioning becomes “a manipulative, artful process” (Greenblatt, Citation1980, p. 2). Improvisation gives Richard “a calculated mask” (p. 222); namely, he can not only hide his original intentions, but also use everything according to his own scenario. Another deceptive practice of Richard is the prayer session—an attempt to show himself a highly religious leader. Regarding the stage performance, Figure shows Richard and the Mayor of London lying on the ground, and Buckingham standing on the left side observing them. Here, this association of religion with a dictator as Richard propagates the idea of Providentialism, according to which many dictators, specifically often those from the Middle East, believe that their position is ordained by the divine power. For them, Guyatt (Citation2007) asserts, “God imagined a special role for certain nations in improving the world […]” (p. 6). However, Richard expresses his atheism several times in the play. Most strikingly, in the prayer scene, after the exit of the Mayor of London from the stage, he reveals to Buckingham that his Bible is actually Machiavelli’s The Prince. His promises are lies including the one he has made to Buckingham: “an earldom and immense wealth” (Naeemi, Citation2018, p. 47)—the wealth which will be acquired as a result of the properties confiscated from Richard’s victims and those who oppose him.

Figure 4. Buckingham, the Mayor of London, and Richard (from left to right) in Prayer Session scene, photo by the author.

In his characterization of Richard, Naeemi follows Shakespeare: Richard mocks and makes fun of his victims. Moreover, as confirmation of his pact to the audience, Naeemi’s Richard seeks approval of the audience to execute his evil plans. During the performance, whenever Richard seeks to reveal his true intentions or provide a rationale, he faces the auditorium in doing so. In every execution order he issues, he first provides a rationale for removing his opponent. However, as noted above, the acts of killing happen on stage such as Richard’s removal of his dissenting courtiers in a secret gathering at the Tower where he and Buckingham command a group of assassins to kill everyone sitting around the table including the suspicious Hastings. In addition to the representation of violence, Naeemi shows that Richard is an adamant opposer of freedom. Much resembling today’s dictators, he believes in having absolute control over people and their affairs in a way to limit drastically their personal freedom. This becomes evident as Buckingham suggests to him to reign by providing security and comfort in his kingdom, yet he meets with Richard’s scathing reply that “nothing exists in the name of safety” and goes on to say that “let two-third of the city live in utter darkness” (Naeemi, Citation2018, p. 65). Civil uprisings and street demonstrations mark the early days of Richard as a monarch; during his conversation with his dressmaker, “the sound of guns and ambulance sirens” is heard distantly (ibid, p. 101). Here, the costume design is telling in a way that male characters’ dressing is modernized, e.g., wearing formal and combat suits, and female figures are dressed in the late Victorian fashion. Most strikingly, Richard evinces an avid interest in wearing a red military uniform, particularly after his coronation. His wearing combat uniform bears resemblance to many twentieth-century world dictators who typically appeared in their formal ceremonies and events in military uniforms. In Iran, the two Pahlavi monarchs too almost always appeared in public in military uniforms, especially the first Pahlavi ruler Reza Shah (1878–1944) who exercised repressive power and under whose rule many intellectuals and dissenters “were marginalized” (Mirsepassi, Citation2019, p. 177). Richard questions the era of the Pahlavis; it points to the fact that although that period was marked as the Constitutional Monarchy, the two Shahs were arbitrary rulers whose decisions and policies were impediment of democracy and Constitutional laws.

The second half of the play, it can be argued, is a survey into Richard’s autocratic regime and the exercise of his political violence. Naeemi employs the idea that Shakespeare’s representation of tyrants can be relevant in understanding today’s dictators. Through his presentist approach, Greenblatt (Citation2018) examines the relevance of Shakespeare’s representation of tyrants and politics in the present context by asking “how is it possible for a whole country to fall into the hands of a tyrant?” (p. 1). Shakespeare’s critical voice echoes in Naeemi’s adaptation: an autocrat like Richard is the one that applies and flouts the laws according to his own will and interest, such as Richard’s remark to Buckingham that “we are the authorities determining what is right and wrong!” (Naeemi, Citation2018, p. 84). He then adds that fear is the key to having a successful rule because it

gives legitimacy to freedom … subway bombing, poisoning the water by the terrorists; act in a way to make people terrify walking on empty, dark streets. The thought that there is always a threat, a danger makes them crippled … fear of unemployment, natural disasters, pollution, disease, counterfeit medications, unhealthy foodstuff with banned additives, imprisonment, execution, the police, a judge … fear must rule people’s lives and affairs. (ibid, pp. 63–64)

In the above lines, the things Richard utters are actually the grave difficulties that the Iranian society faces today. Saikal (Citation2019) opines that the high rate of theft and robbery, news coverage of discoveries of illegal stores of fake medicines and food products, and oppressive social order, have all contributed to the deterioration of living conditions of Iranians in the past decades.

Naeemi characterizes Richard in such a way that he resembles Persian authoritarian rulers after the Arab conquest of Persia (633–56 AD). Particularly, the Safavid and Afsharid dynasties, which ruled Iran between the early sixteenth and mid-eighteenth centuries, were famous for having absolutist system of aristocracy and absolute monarchs such the Safavid Abbas the Great (1571–1629) and the Afsharid Nader Shah (1988–1747), who exercised extreme violence against those their dissenters, including their own family members, although they were at the same time powerful figures who initiated reform and development in Persia (Axworthy, Citation2008). It can be said that Richard is somewhat akin to such monarchs; he not only eliminates his own family members, Clarence for example, but also anticipates his opponents’ move to contain the possibility of resistance. However, oppositional ideas expressed in Shakespeare originate from female characters; they forge a close bond in order to resist patriarchal influence and the fact that they are marginalized in the political scene. The Duchess of Gloucester, Lady Anne, and Queen Margaret, as stated by DiGangi (Citation2016), “deploy the rhetoric of motherhood to enhance their own social and political status in a time of crisis” (p. 429). By the same token, as Hutcheon argues that adaptation involves “(re)interpretation” (Hutcheon, Citation2013, p. 8), Naeemi makes use of this female bond and highlights it to critique oppressive structures of patriarchy in the Iranian society in which the implementation of severe laws, particularly in the post-1979 revolutionary period, have restricted Iranian women’s freedom and rights greatly (Paidar, Citation1995). In Naeemi’s Richard, Queen Anne attempts to liberate herself from Richard’s tyranny and because of her opposition to Richard’s murderous acts and her obligations as his wife, she intends to “self-immolate at the coronation ceremony” (Naeemi, Citation2018, p. 55); however, her act never takes place since Richard kills her by offering a poisonous drink and shouting that the queen has fainted and a physician is needed. Female self-immolation, according to Suhrabi et al. (Citation2012), is actually an age-old traditional practice in developing countries such as Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. This practice, they argue, is done by reason of the guilt, shame, and scandal caused by socio-cultural and religious including sexual affairs, “bigamy, lack of interest in the family affairs, lack of love, premature marriage” and taboo subjects surrounding marital life, e.g., adultery (pp. 95–97).

After the coronation, the dominant characters are Richard and Buckingham. The characterization of the Duke of Buckingham is significant. Although he is accomplice in carrying out Richard’s death sentences and other unlawful acts such as confiscating the victims’ properties (Walsh, Citation2009), he often acts as Richard’s inner voice giving him warnings about exercise of tyranny and restriction of people’s freedom and rights. When he realizes the formation of strong oppositional forces against Richard, he escapes and joins those forces. Before departure, his dialogue with Richard is influential in his decision, particularly Richard’s remark that “we are the authorities determining what is right and wrong!” (Naeemi, Citation2018, p. 84). Richmond is totally absent from the adaptation, and there is also no approaching army to threaten Richard’s regime. It is the common people, with the aid of deserters and disobedient officials like Buckingham, who have sparked a mass uprising to overthrow Richard’s dictatorial regime.

In the last two scenes, the Messenger, a comic figure, appears to deliver detailed reports of the mass insurgence to Richard. He is the only figure, who in his dialogues with Richard, outwits and reprimands him:

Your life should have been ended 20 years ago … I’ve seen many died at the age of 10, 12, or 20 … understand what I’m saying? You’ve lived 20 years more than those; you should have died a long time ago. Now that you’re breathing, alive. Glorify the Lord … respect His servants … only a small incident has made you a king and me a messenger … if your father made my mother pregnant, I’d wear a big crown now and you were the one giving me reports.

…

What! You can’t talk … of course you can’t have anything for a rational statement. OK, I got to leave now, need do some errands. Have a nice day … oh, by the way, give me a bit raise in my salary … with this low income even dogs can’t support their families and afford living expenses my Lord! (Naeemi, Citation2018, p. 108)

The Messenger’s role can be related to that of the Fool in King Lear. Both figures speak freely to the royal figures of the play in their sarcastic, mocking tone. After Buckingham, Naeemi gives the responsibility of warning Richard about his suppressive actions and oppression to the Messenger. Unimpressed by any piece of advice, Richard finally mobilizes the army under his own command to suppress rebel forces; however, before the dispatch of the army, without any serious conflict and bloodshed, Richard is defeated, and his dictatorial regime overthrown. Figure shows Richard’s defeat by a group of soldiers wearing today’s Iranian military uniforms yet holding swords, somehow mixing the modern and the old. The Assassin, who is previously commissioned by Richard to remove his opponents, stabbed Richard in the end: “My lord, you’re alone, deserted! Please … make peace with me” (Naeemi, Citation2018, p. 124). The final lines in the play are uttered by Queen Margaret over the corpse of Richard. She laments that, for both her husband King Henry VI and Richard, the exercise of tyranny and oppression was the main cause of their downfall: “people will never forgive us” (ibid, p. 125). As an authoritarian ruler, Richard violates all ethical and humanitarian principles to achieve his goals. He is a tyrant and, in the end, his removal from power is considered urgent and essential. Unlike in Shakespeare’s original, where Richard is finally defeated by Richmond, in the adaptation, his reign is overthrown by people’s revolutionary uprising, which signals Iran’s contemporary political agitation and the Arab Spring’s spirit of overthrowing dictators of the Middle East. Through establishing an intercultural link, Naeemi’s adaptation directs attention to modern Iran, where the exercise of “sustained autocracy” by Iranian rulers (Ansari, Citation2007, p. 2), and the formation of undemocratic governments have led to unpleasant consequences for Iranians.

6. Conclusion

Since Shakespeare was introduced to Iranians in the late nineteenth century through stage performances and literary translations, his plays have been positively received on the Iranian literary scene. In the second half of the twentieth century, especially after the overthrow of the Pahlavi State, literary and theatrical adaptations of Shakespeare increased substantially, and the first published texts of Shakespeare’s adapted plays appeared in the country from the 1990s onward. For a country like Iran, whose government system lacks democratic principles and structures, Shakespeare provides fruitful material for political interpretations and uses. In this respect, Iranian playwrights and theater producers have aimed to reflect upon sociocultural and political problems by adapting Western canonical authors such as Shakespeare. A striking case is Hamid-Reza Naeemi’s Richard—an adaptation of Richard III—that raises important questions about the government system and in doing so attempts to question dictatorship in modern Iran and other Middle Eastern countries. In Richard, Naeemi expresses disapproval of the difficult socioeconomic and political circumstances in contemporary Iranian society by using Shakespearean tragic theme of the rise and fall of a tyrant. Naeemi poses important questions on the nature of Iranian government system, which since the start of the twentieth century has been undemocratic and has repeatedly suppressed oppositional voices. Shakespeare’s exploration of legitimacy and tyranny in Richard III enables Naeemi to carry out a critical survey of the relationship between Iranian government system and the people.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ramin Farhadi

Ramin Farhadi, M.A. in English at Azad University of Karaj in Iran, is an independent scholar who is interested in the intersection of literature, politics, and history. His main areas of research include postwar Anglo-American theater, Shakespeare and his peers, contemporary Iranian drama, and comparative and adaptation Studies. He reads literary texts through the critical lens of cultural materialism, post-structuralism, sociopolitical criticism, and gender studies in order to explore representations of dissident politics, sexual identities, and social inequalities alongside of mapping power relations and ideological implications. He has so far written on contemporary British playwrights such as Howard Barker, Howard Brenton, and Edward Bond. Chief among them are “Power and Resistance: Disappointment of Socialism in Howard Brenton’s Magnificence” in Athens Journal of Philology and “Power and Surveillant Gaze in Howard Barker’s The Gaoler’s Ache” in International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature (IJALLEL).

References

- Allen, G. (2000). Intertextuality. Routledge.

- Ansari, A. (2007). Modern Iran (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Atwood, B. (2012). Sense and censorship in the Islamic Republic of Iran. World Literature Today, 86(3), 38–15. https://doi.org/10.7588/worllitetoda.86.3.0038

- Axworthy, M. (2008). A history of Iran: Empires of the mind. Basics Books.

- Axworthy, M. (2013). Revolutionary Iran: A history of the Islamic Republic. Oxford University Press.

- Azimi, A., & Moosavi, M. (2019). Mystic lear and playful hamlet: The critical cultural dramaturgy in the Iranian appropriations of Shakespearean tragedy. Asian Theatre Journal, 36(1), 144–164. https://doi.org/10.1353/atj.2019.0007

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination: Four essays. (C. Emerson and M. Holquist, Trans.). University of Texas Press.

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1986). Speech genres and other late essays. (V. W. McGee, Trans.). University of Texas Press.

- Bozorgmehr, S. (2015). The impact of translation of dramatic texts on Iranian theater. Bonyan Books.

- Cook, S. (2017). False dawn: Protest, democracy, and violence in the new middle east. OUP.

- DiGangi, M. (2016). Competitive mourning and female agency in Richard III. In D. Callaghan (Ed.), A feminist companion to Shakespeare (2nd ed., pp. 428–439). Blackwell.

- Dunn, T. (1996). Sated, starred, or satisfied: The languages of theatre in Britain Today. In T. Shank (Ed.), Contemporary British theatre (pp. 19–38). Macmillan.

- Eposito, J., Sonn, T., & Voll, J. (2015). Islam and democracy after the Arab spring. Oxford University Press.

- Esmailpour, G. (2018, August 20). An introduction to Naeemi’s Richard. Saliss. Retrieved August 30, 2019, from https://saliss.com/%D8%AA%D8%A6%D8%A7%D8%AA%D8%B1/2%D8%AA%D8%A6%D8%A7%D8%AA%D8%B1/721-2.html

- Felluga, F. (1995). The critic’s new clothes: Sartor resartus as cold carnival. Criticism, 37(4), 583–599. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23118254

- Foust, C. (2010). Transgression as a mode of resistance: Rethinking social movement in an era of corporate globalization. Lexington Books.

- Garber, M. (2004). Richard III and the shape of history. In E. Smith (Ed.), Shakespeare’s histories (pp. 42–66). Blackwell.

- Greenblatt, S. (1980). Renaissance self-fashioning: From more to Shakespeare. University of Chicago Press.

- Greenblatt, S. (2018). Tyrant: Shakespeare on politics. W.W. Norton & Company.

- Greene, R. (2003). The art of seduction. Penguin Books.

- Guyatt, N. (2007). Providence and the invention of the United States, 1607–1876. Cambridge University Press.

- Haddadian-Moghaddam, E. (2014). Literary translation in modern Iran. John Benjamins B.V.

- Heinemann, M. (2003). Political Drama. In A. R. Braunmuller & M. Hattaway (Eds.), The Cambridge companion to English renaissance Drama (pp. 164–196). Cambridge University Press.

- Horri, A. (2003). The influence of translation on Shakespeare’s reception in Iran: Three Farsi Hamlets and suggestions for a fourth [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Middlesex University.

- Hosseini, R. (2016). When the ghost of lear asks joker for a day off. Botimar.

- Hutcheon, L. (2013). A theory of adaptation (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Jenks, C. (2003). Transgression. Routledge.

- Jett, D. (2018). The Iran nuclear deal: Bombs, bureaucrats, and billionaires. Macmillan.

- Katouzian, H. (2003). Iranian history and politics: The dialectic of state and society. Routledge.

- Kellert, S. (1993). In the wake of Chaos. Chicago University Press.

- Kristeva, J. (1984). Revolution in the poetic language. (M. Waller, Trans.). Columbia University Press.

- Litvin, M., Oz, A., & Partovi, P. (2017). Middle Eastern Shakespeares. In J. Levenson & R. Ormsby (Eds.), The Shakespearean World (pp. 97–115). Routledge.

- Malpas, S. (2005). The postmodern. Routledge.

- Massoudi, S., & Behrouzinia, Z. (2016). Revision of dominance as puppet in Akbar Radi’s Hamlet with seasonal salad: A max weberian reading. Iran Journal of Theater, 1(66), 107–120. https://www.sid.ir/fa/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=314786

- Mehl, D. (1999). Shakespeare’s tragedies: An introduction. Cambridge University Press.

- Mesquita, B., & Smith, A. (2011). The Dictator’s Handbook: Why bad behavior is almost always good politics. Public Affairs.

- Mirsepassi, A. (2000). Intellectual discourse and the politics of modernization: Negotiating modernity in Iran. Cambridge University Press.

- Mirsepassi, A. (2019). Iran’s quiet revolution: The downfall of the Pahlavi state. Cambridge University Press.

- Naeemi, H. (2018). Richard. Novda.

- Nasiri, M. (2014). The Hemlock of courage: A review of Hamid-Reza Naeemi’s socrates. Theater Magazine, 15(173), 78–79. https://theater.ir/fa/108922

- Paidar, P. (1995). Women and the political process in 20th Century Iran. Cambridge University Press.

- Pierce, R. (1971). Shakespeare’s HISTORY plays: The family and the state. Ohio State University Press.

- Rabey, D. I. (2003). English Drama since 1940. Routledge.

- Rabey, D. I. (2009). Howard barker: Ecstasy and death: An expository study of his drama, theory and production work, 1988–2008. Macmillan.

- Rees, A. (2004). Political thought from Machiavelli to Stalin: Revolutionary Machiavellism. Macmillan.

- Safar, M. (2017, April 30). A journey with Shakespeare, Davoud Rashidi and Reza Baraheni. Iran Art. Retrieved July 23, 2020, from http://www.iranart.news/tags/%D9%86%D9%85%D8%A7%DB%8C%D8%B4_%D8%B1%DB%8C%DA%86%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%AF_%D8%B3%D9%88%D9%85

- Saikal, A. (2019). Iran rising: The survival and future of the Islamic Republic. Princeton University Press.

- Sedarat, R. (2011). Shakespeare and the Islamic Republic of Iran: Performing the translation of Gholamhoseyn Sa’edi’s Othello in Wonderland. Theatre Annual, 64, 86–106. https://theatreannual.atds.org/

- Stříbrný, Z. (2000). Shakespeare and Eastern Europe. Oxford University Press.

- Suhrabi, Z., Delpisheh, A., & Taghinejad, H. (2012). Tragedy of women’s self-immolation in iran and developing communities: A review. International Journal of Burns and Trauma, 2(2), 93–104. http://www.ijbt.org/IJBT_V2N2.html

- Walsh, B. (2009). Shakespeare, The Queen’s Men, and the Elizabethan Performance of History. Cambridge University Press.

- Wells, R. H. (1986). Shakespeare, politics and the state. Macmillan.

- Yaghmaian, B. (2012). Social change in Iran: An eyewitness account of dissent, defiance, and new movements for rights. SUNY Press.