Abstract

This study examined rejection dialogues (refusals) in three popular Chinese TV dramas namely ‘Longing’, ‘The Happy Life of Zhang Damin’, and ‘Family with Children’ through the lens of speech act theory and refusal theory. Dialogue transcripts were thoroughly analyzed to identify rejection expressions within various contexts, considering politeness factors to select relevant examples. The analysis focused on how distinctions in politeness levels and contextual factors influenced the manifestation of refusals in Chinese discourse, highlighting five categories of refusal expressions embodying politeness strategies. Specific instances were qualitatively analyzed to discern deeper insights into refusal dynamics, considering factors such as linguistic form, triggering behavior, relational dynamics, and conversational impact. This comprehensive approach acknowledged the interplay of linguistic and non-verbal factors in shaping refusal expression, emphasizing their connection to cultural politeness norms.

Introduction

Refusal, a fundamental aspect of conversational interaction, represents a delicate balance between maintaining social harmony and asserting individual agency (Chang, Citation2001; Culpeper, Citation2011). It emerges as a distinctive form of linguistic behavior, wherein speakers navigate the intricacies of politeness and interpersonal dynamics to negotiate their communicative intentions effectively (Hargie, Citation2021). Within the expansive landscape of discourse analysis, understanding how refusals unfold holds significant relevance, not only for theoretical advancements but also for practical implications in everyday communication (Jaspers, Citation2023; Ziskin, Citation2019). Thus, this research endeavors to unravel the multifaceted complexities inherent in refusal speech acts within the context of popular Chinese television series. When delving into the phenomenon of refusal, it becomes apparent that such interactions have potential face-threatening implications for both interlocutors (Lingling & Chuanmao, Citation2020). The delicate task of declining requests, invitations, or offers requires speakers to navigate a fine line between asserting their autonomy and preserving the relational harmony with their conversational partners (Chang & Ren, Citation2020; Isabella et al., Citation2022). As posited by Brown & Levinson (1987), refusals inherently challenge the positive face of the hearer, making them particularly sensitive moments within discourse. Therefore, understanding the strategies employed by speakers to mitigate face-threatening acts becomes imperative (Salman & Betti, Citation2020).

Furthermore, the choice of Chinese television series as the primary corpus for this investigation is deliberate and consequential. Television dramas serve as rich repositories of naturalistic dialogue, encapsulating a diverse array of social interactions reflective of real-life communication patterns (Buckledee, Citation2020; Fauziyah et al., Citation2024). By analyzing refusal dialogues within the immersive narrative contexts of these series, this study aims to capture the intricacies of refusal expression as it unfolds within the dynamic tapestry of contemporary Chinese society. Moreover, with the prevalence of such media forms shaping cultural norms and linguistic conventions (Ojukwu & Dike, Citation2023), examining refusal discourse within this domain provides invaluable insights into the cultural and social underpinnings that influence communicative behaviors. Thus, against this backdrop, this research sets out to explore not only the linguistic manifestations of refusals but also the underlying socio-cultural dynamics that shape them. By examining the interplay of politeness strategies, contextual factors, and relational considerations, this study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of how refusal speech acts are negotiated and understood within the rich tapestry of Chinese television drama. Ultimately, the insights gleaned from this investigation hold implications not only for discourse analysis scholarship but also for enhancing cross-cultural communication competence and fostering effective interpersonal interactions in diverse sociocultural contexts.

Literature review

Politeness is a critical concept in pragmatics and cross-cultural communication, drawing significant scholarly interest due to its essential role in shaping interpersonal interactions. The seminal contributions of Leech (Citation1983) and Brown & Levinson (1987) have established a foundational understanding of the principles and strategies that underlie politeness within diverse cultural milieus. Central to this discourse is Politeness Theory, which offers a robust framework for examining how individuals navigate the management of face needs and the mitigation of face threats during communication. This theory has been extensively applied and rigorously critiqued in a plethora of subsequent studies (Chintawidy & Sartini, Citation2022; Kádár & House, Citation2021). In the context of Chinese communication, the work of scholars like Gu (Citation1990, Citation1992) has been pivotal in investigating how Confucian ideals of face and harmony inform communication strategies, thus providing profound insights into the cultural subtleties that shape polite discourse. Building upon this, Mao (Citation1994) and, more recently, Qiu et al. (Citation2021) have furthered our understanding by highlighting that politeness transcends mere linguistic selection; it is intricately woven into the societal fabric of China. These investigations emphasize the high-context nature of Asian cultures, where the indirectness and tone of language bear considerable communicative significance.

A salient feature of politeness in Chinese communication is the strategy of self-deprecation and other respect, which is firmly entrenched in traditional linguistic practices. This communicative approach is adeptly analyzed in the seminal work of Pan & Kádár (Citation2011), who expound on how these practices are indicative of broader cultural virtues, such as modesty and the preservation of societal harmony. These virtues are instrumental in sculpting the fabric of interpersonal relations within Chinese communities, presenting a stark divergence from the typically observed assertive communication styles of Western societies (House & Kádár, Citation2023; Zhou, Citation2022). This strategy not only emphasizes the significance of humility and respect but also mirrors a thorough comprehension of the relational intricacies essential to sustaining societal balance. Furthermore, the seminal work of Brown & Levinson (1987) has been instrumental in delineating the concepts of positive and negative face, elucidating the delicate balance required between asserting one’s autonomy (independence face) and preserving social harmony (involvement face). Their framework has been widely adopted and serves as a foundational theory for analyzing politeness across different cultural contexts. However, this framework often encounters challenges when applied uncritically across non-Western contexts. In response to these challenges, Scollon & Scollon (Citation2001) provide a more thorough understanding of how face-threatening acts unfold within discourse, particularly focusing on the intricate dynamics of face negotiation. Their work contributes to a deeper comprehension of how individuals navigate complex social landscapes through their communication choices, adapting to cultural expectations while also attending to personal and relational needs.

Empirical research in other cultural contexts provides a rich comparative perspective to the Chinese paradigm of politeness, which often contrasts significantly with communicative practices elsewhere. For example, studies of politeness in Japanese communication similarly emphasize the importance of indirectness and humility, yet they incorporate unique elements such as honorific language that stratify conversation according to social hierarchy (Pizziconi, Citation2003). In contrast, research into American conversational styles highlights a preference for directness and efficiency in communication, often valuing explicitness over the preservation of relational harmony (Jakučionytė, Citation2020). This divergence stresses the cultural specificity of politeness strategies and their alignment with broader societal values. In Middle Eastern contexts, particularly in Arabic-speaking countries, elaborate verbal courtesy and a strong emphasis on honor and dignity, deeply ingrained in social interactions, often manifest as politeness (Leech & Tatiana, Citation2014). These practices, while sharing the principle of face-saving with Chinese and Japanese cultures (Xiao & Zhou, Citation2024), often employ more overt expressions of respect and deference, reflecting the high-context communication styles typical of collectivist societies. Similarly, studies conducted in Indian contexts reveal a complex interplay of respect, hierarchy, and familial roles, with politeness expressed through linguistic subtleties that consider age, gender, and social status (Kapoor, Citation2022; Pandharipande, Citation1992). These findings illustrate how politeness is not merely a linguistic strategy but a reflection of deeply embedded social structures and values that vary significantly from one culture to another. Such comparative studies highlight the need for comprehensive frameworks in intercultural communication research, recognizing the limitations of universally applying Western models and the value of developing culturally sensitive approaches that better account for the diversity of global communication practices.

However, as the field evolves, a critical review by Jia & Yang (Citation2021) highlights an ongoing discourse among scholars who argue that existing theories of face and politeness, heavily influenced by Western paradigms, do not fully encapsulate the ways in which these concepts manifest in Chinese interactions. This critique suggests a significant theoretical gap; scholars are urged to disentangle these concepts from typical Western theorizations and instead construct theories of facework and politeness rooted in Chinese cultural norms. This entails a departure from a universalist approach, advocating for models that incorporate the unique sociocultural and linguistic distinctions inherent in Chinese communication styles (Du et al., Citation2024). Furthermore, there is a pressing need for empirical and theoretical expansion beyond the simple dichotomy of East-West communication styles. More studies are required to construct models that are genuinely cross-cultural, capable of identifying and explaining the underlying regularities that transcend superficial linguistic and cultural divides (Takimoto, Citation2020). Such models would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of global communication practices, facilitating more effective and respectful intercultural interactions. These endeavors would not only enrich our theoretical frameworks but also enhance practical applications in diverse fields such as international diplomacy, global business, and multicultural team management, where understanding and navigating politeness norms are crucial for success.

Ren & Woodfield (Citation2016) article offers a profound insight into the application of politeness strategies, with a particular emphasis on the methods utilized by women to tactfully handle refusals in the milieu of Chinese television dramas. Their analysis delves into the intricate manners by which individuals maneuver through potentially confrontational scenarios, all the while maintaining the integrity of their interpersonal connections. This research accentuates the vital role of contextual and relational dynamics in communicative exchanges, thereby illuminating the intricate interplay between personal autonomy and the preservation of collective concord. Furthermore, it brings to the fore critical reflections on gender dynamics, positing that women may resort to increasingly sophisticated acts of courtesy, possibly mirroring the entrenched societal anticipations and standards pertaining to gender conduct. Building on this foundation, Chang & Ren (Citation2020) extend the discourse by examining the impact of social hierarchy on the employment of courteous language by adolescents during instances of declination within Chinese conversations. Their research casts light upon the formative path of socio-pragmatic acumen, demonstrating the ways in which the youth calibrate their linguistic approaches in response to the exigencies of the situation and the hierarchical structures they navigate. This investigation is instrumental in delineating the malleable nature of politeness strategies in the developmental years, suggesting that the maturation of social and cognitive faculties is integral to the adept adjustment of verbal interactions to adeptly traverse the labyrinth of social intercourse.

In the broader academic discourse on refusal speech acts, the categorization of refusals into distinct types by Beebe et al. (Citation1990)—direct and indirect—stands out. Direct refusals are characterized by explicit denials or performative verbs that clearly indicate rejection, while indirect refusals employ a more varied set of linguistic strategies to convey refusal without straightforward denial. These might include the use of interjections, expressions of gratitude, or salutations, which serve to soften the refusal and mitigate potential threats to the interlocutor’s face. Zhang (Citation1995) observes that the motivation for employing such indirect strategies, particularly in the context of Chinese communication, often stems from deep-rooted politeness considerations. Small talk, for instance, is not merely filler conversation but a strategic tool used to navigate potentially face-threatening situations, underlining the profound role of politeness in shaping interpersonal dynamics. This emphasis on indirect communication highlights the cultural specificity of politeness strategies and challenges the universality of politeness theories developed in Western contexts.

In the exploration of politeness strategies within Chinese refusal behaviors, academic discourse frequently makes a distinction between genuine refusals and ostensible refusals, each embodying unique communicative functions and cultural significance. Genuine refusals are those in which the refuser clearly intends to decline an offer or request. They typically involve tactical delays, the articulation of specific, often plausible reasons, and the use of linguistic markers such as ‘possible’ to introduce uncertainty or employ a specific word order to enhance politeness. This intricate combination of tactics ensures that the refusal, while clear, is delivered in a manner that maintains social harmony and respects the needs of both parties involved (Li & Cao, Citation2011; Lii-Shih, Citation1994; Su, Citation2020). The employment of such linguistic strategies not only communicates non-acceptance but also cushions the impact of the refusal, thereby upholding the intricate tapestry of interpersonal relationships.

In contrast, ostensible refusals serve a different communicative purpose. Characterized by their lack of delay, ostensible refusals often appear as pre-acceptance refusals or ritualistic refusals and are employed primarily to maintain politeness in procedural interactions. Such refusals are not genuine denials but rather social maneuvers that fulfill certain ritualistic or procedural expectations within the interaction (Eslami, Citation2005; Shishavan, 2016; Su, Citation2020). Chen et al. (Citation1995) note that the utilization of ostensible refusals stresses the speaker’s attention to listener-centered considerations, reflecting a deep understanding of social dynamics and communicative norms. These refusals are strategically deployed to navigate complex social waters, allowing the speaker to defer a genuine refusal or acceptance while assessing the relational and situational context.

Furthermore, Gu (Citation1990) provides insights into the layered process of invitation acceptance within Chinese cultural contexts, describing a sequential progression from initial rejection to eventual acceptance. This pattern reflects the complex negotiation of social obligations and politeness norms, where multiple rounds of refusal and acceptance are not only expected but also required as part of maintaining face and demonstrating respect. Ran & Lai (Citation2014) delve deeper into the interpersonal pragmatic motivations underlying ostensible refusals, shedding light on the delicate balance between fulfilling social expectations and employing effective communicative strategies. However, while this discussion primarily centers on the analysis of genuine refusals from a politeness perspective, the intricate world of Chinese ostensible refusals remains partially unexplored. This gap in the literature suggests a significant area for further research, inviting scholars to delve into the multifaceted dynamics of refusal speech acts within Chinese discourse to better understand their functions, variations, and impacts on interpersonal communication. Such exploration could significantly enhance our understanding of the strategic use of language in maintaining social harmony and managing interpersonal relationships in culturally specific contexts.

Research gap and contribution of the study

Despite the extensive research on politeness strategies and refusal speech acts within the framework of pragmatics and cross-cultural communication, a distinct gap emerges in the empirical examination of these phenomena within the context of Chinese television dramas. Prior studies have extensively explored theoretical aspects of politeness and refusal, often focusing on direct interpersonal interactions, or using experimental designs that may not fully capture the spontaneous nature of everyday communication as depicted in media. Furthermore, while existing literature acknowledges the influence of cultural distinctions on communication strategies, there is a limited focus on how these strategies are portrayed and potentially evolved in modern Chinese television dramas, which are influential in shaping and reflecting contemporary societal norms and behaviors. This gap highlights a need for a more contextualized and media-centric investigation that can bridge the theoretical constructs with the practical, lived experiences as represented in popular media. This study aims to fill the identified gap by analyzing refusal speech acts in a selection of popular Chinese television series, providing a unique lens through which to view the practical application of politeness and refusal strategies in a culturally rich and dynamically evolving context. By leveraging the naturalistic setting of television dramas, this research not only offers insights into the linguistic and non-verbal components of refusal but also explores the broader socio-cultural dynamics at play, including the impact of social status, relational dynamics, and contextual factors.

Moreover, this study contributes methodologically by employing a comprehensive qualitative content analysis combined with a detailed examination of non-verbal cues, thus enriching the understanding of how refusal is communicated beyond mere words. This approach allows for a deeper understanding of the subtleties involved in refusal strategies, including the use of hesitation, mitigation, and other indirect tactics that are culturally specific to Chinese communication styles. By integrating findings from a popular media perspective, this research provides a more holistic view of how refusal strategies are employed in everyday life, thereby enhancing the theoretical frameworks with empirical evidence from contemporary sources. This contributes to the broader discourse in intercultural communication, offering valuable insights for both academic and practical applications in understanding and navigating complex communication patterns in a global context.

Methodology

This study was designed to conduct a detailed examination of rejection dialogues (refusals) in popular Chinese television dramas, specifically focusing on the series ‘Longing’, ‘The Happy Life of Zhang Damin’, and ‘Family with Children.’ The research utilized a dual theoretical approach, integrating frameworks from speech act theory (Liu, Citation2011; Yingxin, Citation2008) and refusal theory (Lee, Citation2016) to explore the complex mechanisms of refusal within these cultural narratives.

Selection of Chinese TV dramas

The selection of dramas for this study was guided by multiple criteria aimed at ensuring the relevance and representativeness of the data. These criteria included the relevance to contemporary Chinese society, the diversity of settings (rural and urban, historical, and modern), and the prevalence of social interactions that typically feature refusal dialogues. Employing a purposive sampling method, this approach guaranteed that the selected dramas would yield linguistically pertinent data while encapsulating the sociocultural traces intrinsic to Chinese familial and social interactions. The process involved a multi-tiered strategy, beginning with the compilation of a comprehensive list of popular Chinese dramas from the past decade. This list was generated through an examination of viewership ratings and critical reviews, with the intent to represent a broad spectrum of socio-cultural backgrounds and familial dynamics. Following this initial screening, dramas were specifically selected for their high viewership ratings, favorable critical reception, and the depth with which they portray interpersonal conflicts and resolutions. ‘Longing’, ‘The Happy Life of Zhang Damin’, and ‘Family with Children’ were ultimately chosen because they offer a rich source of dialogues featuring refusal interactions, thereby providing a diverse and informative dataset for analyzing refusal speech acts.

Data collection

The data collection phase was initiated by thoroughly transcribing dialogues from episodes of the selected television series that contained significant refusal interactions. This transcription was conducted by a team of linguistics students who were not only fluent in Mandarin but also trained in linguistic analysis and well-versed in the cultural traces of Chinese communication. They manually recorded every dialogue verbatim, with a particular focus on sequences anticipated or known to involve refusal speech acts. Then, the transcription process extended beyond verbal exchanges to include a detailed notation of non-verbal cues, such as body language, facial expressions, and the physical setting of each scene. These annotations provided crucial contextual information that could influence both the linguistic form and the functional implications of the refusals.

To ensure the reliability of the data, each episode was transcribed independently by two researchers. Any discrepancies encountered were resolved through discussion or, if necessary, consultation with a senior researcher. This rigorous approach not only enhanced the accuracy of the transcriptions but also guaranteed a comprehensive documentation of refusal instances. Each recorded instance of refusal was documented along with extensive contextual details such as preceding events, specific episodes, and timestamps. This structured approach facilitated the systematic compilation of data, allowing for easy retrieval and accurate re-examination of scenes during the analysis phase, thereby reinforcing the integrity and depth of the study’s empirical findings.

Data organization and preliminary filtering

Once transcribed, the dialogues underwent a preliminary filtering process where instances of explicit and implicit refusal were identified. The filtering criteria were developed based on the theoretical frameworks employed, focusing on linguistic markers of refusal and contextual parameters such as the power relations between characters, the formality of the setting, and the emotional tone of the interaction. Each potential refusal was tagged and categorized into a database with relevant metadata, including episode number, characters involved, and the nature of the refusal.

Data analysis

In the data analysis phase, the study employed qualitative content analysis methods to systematically evaluate the refusal utterances (Wiedemann, Citation2016). This involved coding each refusal instance based on several dimensions: the linguistic structure of the refusal, the conversational trigger (i.e. what request or suggestion was being refused), relational dynamics between the characters (e.g. familial, professional), and the characters’ ages and social statuses. A particular focus was placed on the interactional stakes involved—how the refusal might affect the relationship or status quo. Advanced linguistic models were then applied to analyze the data, such as pragmatic analysis to understand how refusals are situated within the broader conversational goals and sociolinguistic analysis to explore how identity and social factors influence refusal strategies (Allami & Naeimi, Citation2011). The use of computational tools such as text analytics software enabled the identification of patterns and trends across the data set, such as the frequency of certain types of refusals or the correlation between refusal types and specific social or familial roles (Kuhn, Citation2019).

Non-verbal cues were also analyzed using video analysis software, which helped in understanding the impact of gestures, facial expressions, and physical orientation on the delivery and reception of refusal. This comprehensive approach aimed to uncover the layered strategies of politeness and directness in refusal episodes, emphasizing the intricate balance between verbal and non-verbal communication in shaping interpersonal dynamics within the context of Chinese cultural norms. This study aimed to conduct a comprehensive examination of rejection dialogues (refusals) depicted in prominent Chinese television dramas, namely ‘Longing’, ‘The Happy Life of Zhang Damin’, and ‘Family with Children’, employing a dual theoretical framework rooted in speech act theory (Liu, Citation2011; Yingxin, Citation2008) and refusal theory (Lee, Citation2016).

The data analysis phase involved an examination of specific examples through qualitative analysis techniques (Kasper, Citation2006). Refusal utterances were classified based on multiple criteria, including the linguistic expression form of the refusal utterance itself, the triggering behavior prompting the refusal, the relational dynamics between conversational participants, the age of the refuser, and the potential impact of the refusal on both parties involved in the interaction. Additionally, linguistic factors were analyzed to discern patterns and traces in refusal expressions, with particular attention given to non-verbal cues that may influence the form and tone of refusal expressions. It is posited that these non-verbal factors play a fundamental role in shaping the politeness strategies employed by refusers, highlighting the intricate interplay between linguistic and socio-cultural dimensions in the manifestation of refusal speech acts.

Result and discussion

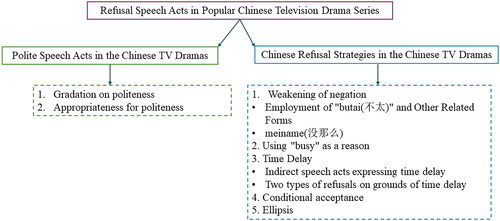

delineates the primary findings of the study’s analysis regarding speech acts in popular Chinese television drama series. The results are categorized into two principal groups: polite speech acts and Chinese refusal strategies in these dramas. The investigation into polite speech acts reveals two critical aspects: 1) Gradation of politeness; and 2) Appropriateness of politeness. These findings suggest that expressions of politeness in Chinese TV dramas are sophisticated and contingent upon contextual dynamics. The analysis of refusal strategies is more extensive, encompassing several methods: 1) Weakening of negation; 2) Utilization of ‘butai (不太)’ and analogous phrases; 3) Citing ‘busy’ as a rationale for refusal. 4) Time Delay, which includes indirect speech acts that signify time delay and two distinct types of refusals predicated on time delay; 5) Conditional acceptance; and 6) Use of ellipsis. Chinese television dramas articulate refusals in an indirect and culturally manner through these strategies. The results are further elaborated and discussed below.

Furthermore, the selected excerpts from the television drama series are presented in accordance with The Leipzig Glossing Rules, which traditionally require a uniform format comprising three principal elements: an example in the original language, a detailed morpheme-by-morpheme gloss, and a fluent translation into English or another language of choice (Chelliah et al., Citation2021). Nevertheless, this investigation confines itself to providing only the original language example and the corresponding morpheme-by-morpheme gloss, as each instance is accompanied by a subsequent analysis of the referenced extracts within the scope of the research.

Polite speech acts in the Chinese TV dramas

Gu (Citation1992) delineates polite speech acts into two distinct dimensions: politeness in content and politeness in expression. Refusal, by its very nature, often catches addresses off guard during communication, posing a threat to their face. Consequently, the politeness of refusal predominantly manifests in the form of expression. Within the realm of Chinese refusal, politeness is chiefly observed through two interconnected aspects: gradations and appropriateness.

Gradations on politeness

Politeness principles exhibit a continuum of gradations. Generally, the more indirect the expression, the higher the perceived level of politeness (He & Ran, Citation2002). However, this correlation is not absolute, as the degree of politeness conveyed by the same form may vary. Consider the following examples:

‘Hand me the newspaper.’

‘Have another sandwich.’

Both utterances employ imperative sentences, yet example (2) appears inherently more polite than example (1). While example (1) constitutes a request, example (2) frames an offer. In (1), the speaker benefits, whereas in (2), the hearer gains favor, rendering the imperative form more polite than (1) based on the differential impact on the hearer’s benefit and loss. Thus, while language form serves as a gauge for assessing politeness gradations, the underlying impact on the hearer’s benefit and loss stands as the fundamental criterion for evaluating politeness gradations across different forms and specific expressions within the same form. Consequently, while this discussion on politeness gradations in refusal focuses primarily on Chinese linguistic forms, due consideration is given to the influence of the benefit or loss accruing to the hearer on the politeness gradation. Speech acts entailing substantial benefit to the hearer exhibit a higher level of politeness, whereas those offering minimal benefit convey a lower level of politeness.

From the perspective that indirect forms reflect greater politeness, the politest refusal is expected to manifest through affirmative declarative sentences, whereas the least polite is conveyed through the illocutionary verb ‘refuse’ or a direct ‘no.’ Moreover, a plethora of refusals are executed through indirect speech acts (Searle, Citation1979/2001), each varying in politeness gradation owing to their distinct forms and the differential impact on the hearer’s benefit or loss. For instance:

(Original sentence in the source language).

刘慧芳: 妈, 把孩子给我吧! (Original sentence in the source language)

刘母: 不用!

刘母: 我不想给你!

刘母: 我给不了你!

刘母: 给你干嘛?

刘母: 别带走了!

刘母: 算了, 我带着吧。

刘母: 你带着, 行吗?Footnote1

刘母: 还是我带着吧。

刘母: 这……

刘母: 过两天再说吧。

刘母: 我想想。(电视剧《渴望》)

(Morpheme-by-morpheme gloss (word-for-word translation)).

Liu Huifang: Mom, give me the child!

Mother Liu: No need!

Mother Liu: I don’t want to give it to you!

Mother Liu: I can’t give it to you!

Mother Liu: Why should I give it to you?

Mother Liu: Don’t take it away!

Mother Liu: Forget it, I’ll take care of it myself.

Mother Liu: You take it with you, okay?

Mother Liu: I’d better take care of it.

Mother Liu: This…

Mother Liu: Let’s talk about it in a few days.

Mother Liu: Let me think about it. (TV series ‘Longing’)

Except for (3a), the rejection responses encompassed within (3b–3k) exhibit indirectness, rendering them inherently more polite than (3a). However, the degree of politeness varies across these utterances due to the diverse forms of indirect refusal and the disparate benefits accruing to the hearers. For instance, juxtaposing (3b) and (3c), both feature explicit negative markers. However, while (3b) accentuates the speaker’s controllable will, thereby imposing a greater loss on the hearer, (3c) accentuates the lack of ability, imbuing it with a higher level of politeness. In (3d), the utterance adopts an affirmative rhetorical question, amplifying the negative connotation and consequently inflicting more loss on the hearer. Similarly, considering two refusals executed through imperative sentences, (3f) emerges as more polite than (3e) due to the dissuasive and prohibitive nature of the negative form of the imperative sentence, resulting in greater loss and fewer benefits for the hearer when employed for refusal.

Appropriateness for politeness

Refusal, as a speech act that frequently poses a threat to the hearer’s face (Brown & Levinson, 1987), typically necessitates a polite form of expression. However, it is crucial to recognize that the degree of politeness must be balanced with appropriateness. Hence, when refusing, the speaker must consider various contextual factors, including the relationship and status of the conversational participants, the gender and age of the hearer, the situational context, the severity of the face-threatening act, and the complexity of the refusal expression. Striking this balance is paramount to avoid excessive politeness, which may lead to unintended consequences such as embarrassment or misinterpretation of implicature, ultimately hindering effective communication outcomes (Li & Guo, Citation2021). For instance, in the scenario depicted in example (3), where the refusal is issued by a mother to her daughter, a direct refusal using ‘buyong(不用)’ is deemed appropriate. Moreover, based on corpus analysis, direct refusals are commonly employed in two other scenarios: firstly, when the speaker and hearer share equal status and maintain a close relationship, with the refusal posing minimal threat to the hearer’s face; secondly, when the speaker and hearer are strangers, signifying a significant social distance between them, and where the speaker holds a visibly higher status than the hearer. For example:

(Original sentence in the source language)

张大民: 我跟着去吧?

张大雪: 不用。(电视剧《贫嘴张大民的幸福生活》).

张大民: 看不见没关系。您摸摸, 这暖壶, 漆喷得多滑溜, 跟您那小孙子的 小屁股蛋儿似的。您还不抱一个回去?

大妈: 不要!我们家有。(电视剧《贫嘴张大民的幸福生活》).

(Morpheme-by-morpheme gloss (word-for-word translation))

Zhang Damin: Shall I follow?

Zhang Daxue: Don’t. (TV series ‘The Happy Life of Zhang Damin’).

Zhang Damin: It doesn’t matter if you can’t see it. Just touch it, the paint on this

thermos is so slippery, it feels like your little grandson’s little butt. Don’t you want to take one back?.

Aunt: No! Our family has one. (TV series ‘The Happy Life of Zhang Damin’).

Example (4) depicts a typical exchange between siblings, wherein the elder brother’s proposal is declined. Given the familial context and the relatively low threat to the elder brother’s face, a direct refusal is deemed appropriate and does not entail a breach of politeness norms. Similarly, in Example (5), the interaction unfolds between a customer and a salesperson, wherein it is customary for the customer to issue a straightforward refusal. Dong (Citation1999) posits that the politest refusals in Chinese occur in interactions with acquaintances who maintain a level of familiarity but lack closeness. This observation highlights the interplay between linguistic and non-linguistic factors, such as the relational dynamics and relative social status of the conversational participants, in determining the appropriateness of refusal strategies. Thus, for acquaintances characterized by moderate familiarity but not intimacy, employing the politest refusal tends to optimize communication outcomes by striking the ideal balance between politeness and appropriateness.

Chinese refusal strategies in the Chinese TV dramas

As elucidated by Liao & Bresnahan (Citation1996), Chinese refusal strategies encompass a diverse array of 24 categories, several of which, including direct refusal, are intricately linked to considerations of politeness. This section delves into an analysis of five prevalent expressions in Chinese refusals that exemplify politeness, elucidating the underlying refusal strategies they encapsulate.

Weakening of negation

Employment of ‘butai(不太)’ and other related forms

Within the Chinese linguistic framework, expressions such as ‘butai(不太)’, ‘buda(不大)’, and ‘buzenme(不怎么)’ serve as common negation markers. While quantitatively, the degree conveyed by ‘butai(不太)’ and ‘buda(不大)’ is perceived to be lesser than that of ‘bu(不)’, pragmatically, they are often utilized to denote general negation in Chinese discourse. Essentially, despite the adoption of ‘butai(不太)’ and similar forms, they inherently signify ‘bu(不)’, maintaining the same degree of negation but attuning the tone to a more moderate register. Consequently, when employed to convey refusal, these expressions fulfill a similar functional role, albeit with a gentler tonal quality compared to straightforward negation. This moderated tone lends a sense of politeness to the refusal act. For example:

(Original sentence in the source language)

刘慧芳: 不是您说的吗?只要咱们共同的努力小芳总有站起来的那一天,

走吧!罗老师, 去找她姑姑商量商量, 别耽搁着了!.

罗冈: 我不太想去了。(电视剧《渴望》).

(Morpheme-by-morpheme gloss (word-for-word translation))

Liu Huifang: Didn’t you say it? If we work together, Xiaofang will stand up one day.

Let’s go! Teacher Luo let’s go to discuss it with her aunt. Let’s not delay!.

Luo Gang: I don’t really want to go. (TV series ‘Longing’).

In example (6), the expression ‘I don’t really want to go (Wo butai xiang qu le. 我不太想去了。)’ and ‘I don’t want to go (Wo bu xiang qu le. 我不想去了。)’ essentially serve the same purpose when employed to decline. Both convey a direct refusal strategy, explicitly stating a negative response. Furthermore, the modifier ‘butai(不太)’ in the former can be interchanged with ‘buda(不大)’ or ‘buzenme(不怎么)’ without altering the refusal’s essence. However, it’s imperative to note that while these forms occasionally substitute the rejection containing ‘bu(不)’ in Chinese, there exists a nuanced difference when ‘butai(不太)’ modifies the action verb for refusal. Unlike the construction ‘bu(不) + action verb’, which typically negates the speaker’s will and reflects subjective intention (Zhu, Citation1982: 200), ‘butai(不太) + action verb’ does not impart the same connotation. This distinction becomes apparent upon comparing the following example:

(Original sentence in the source language)

夏东海: 爸, 吃饭了!

爷爷: 不吃!

爷爷: 不太吃!Footnote2(电视剧《家有儿女》)

(Morpheme-by-morpheme gloss (word-for-word translation))

Xia Donghai: Dad, it’s time to eat!

Grandpa: I don’t eat!

Grandpa: I don’t eat much! (TV series ‘Family with Children’)

The expressions ‘Don’t eat(buchi不吃)’ and ‘not too much(butaichi不太吃)’ both possess the capability to convey refusal within specific contexts, yet they diverge in their connotations. The former, ‘buchi不吃’, may signify a denial of willingness or a direct rejection of the action implied by the directive. Conversely, the latter, ‘butaichi不太吃’, primarily denotes the speaker’s habitual preference or a comparatively infrequent engagement in a particular action. In essence, (7a) exhibits a more subjective stance compared to (7b). Consequently, it becomes evident that ‘butai(不太) + action verb’ cannot entirely substitute ‘bu(不) + action verb’ when expressing refusal. However, this discrepancy does not hold true for constructions involving ‘bu(不)/butai(不太) + auxiliary verb (phrase)/verbs showing emotion/adjective.’ In such cases, the semantic differences are minimal, with distinctions primarily manifesting at the pragmatic level.

Meiname(没那么)

When ‘meiname(没那么)’ is positioned before adjectives, verbs denoting emotion, auxiliary verbs, and similar elements, it functions to negate the degree rather than the inherent quality. For instance, ‘not so good (meiname hao没那么好)’ does not negate ‘hao(好)’ outright, but rather, it attenuates the degree of ‘hao(好).’ In comparison to the utilization of ‘bu(不)’ to modify these components, where ‘bu(不)’ typically conveys a sense of ‘less than’ or ‘lower than’ ‘meiname hao(没那么好)’ elucidates the nuanced distinction within the quality of ‘hao(好).’ When addressing negative attributes, ‘not so(meiname没那么)’ conveys a higher level of gradation compared to ‘no(bu不).’ Following the principle that smaller-scale negation entails a broader scope of negation, the scope of negation encompassed by ‘bu(不) + adjective’ is encapsulated within that of ‘meiname(没那么) + adjective.’ Conversely, the affirmative scope of ‘meiname(没那么) + adjective’ exceeds that of ‘bu(不) + adjective’, as negation inherently affirms a certain quantity, and the scope of negation inversely correlates with the scope of affirmation. Affirmation, being conducive to mitigating emotional and opinionated opposition between interlocutors, aligns more closely with the tenets of politeness. Hence, when adjectives permit modification by both ‘bu(不)’ and ‘meiname(没那么)’, employing ‘meiname(没那么)’ for negation in refusal is deemed more courteous. Nonetheless, it warrants attention that the scope of negation for ‘not so’ may not consistently align across different emotional contexts. When ‘meiname(没那么)’ modifies a laudatory term, it typically signifies a diminution of the internal degree of the word. Conversely, when modifying a neutral term, it can negate the internal degree or imply a level lower than that of the neutral term within a specific context, akin to the meaning conveyed by ‘bu(不).’ However, when modifying a pejorative term, ‘meiname(没那么)’ predominantly indicates ‘below’ or ‘less than’, abstaining from the negation of the internal degree. This distinction is exemplified in the following example:

(Original sentence in the source language)

没那么好 不好

没那么勤劳 不勤劳.

没那么热 不热.

没那么简单 不简单.

没那么娇气 不娇气Footnote3.

(Morpheme-by-morpheme gloss (word-for-word translation))

not so good/bad

not so hardworking/not hardworking.

not that hot/not hot.

not so simple/not simple.

not so squeamish/not squeamish.

Based on the principle of the inverse relationship between the scope of negation and the scope of affirmation, it follows that the diminishment of negation for commendatory terms entails a broader affirmation scope, whereas the amplification of negation for derogatory terms results in a narrower affirmation scope. Consequently, the variance in negation scope attributed to affective language may be contingent upon the speaker’s subjective inclination. Generally, individuals exhibit a predisposition to affirm positive connotations while refuting derogatory implications. Such linguistic forms employed in refusals often elucidate the rationale behind the refusal, representing an indirect speech act wherein refusal is conveyed through assertion. For instance:

(Original sentence in the source language)

田莉 : 要不要包一包?

王亚茹: 没那么娇气。(电视剧《渴望》).

(Morpheme-by-morpheme gloss (word-for-word translation))

Tian Li: Do you want to cover your wound?

Wang Yaru: (I am) Not so squeamish. (TV series ‘Longing’).

Example (9) articulates the rationale for refusal through an indirect approach. It is notable that in this instance, the negation pertains not to the degree of ‘squeamishness’, but rather to the quality itself. The usage of ‘meiname (没那么)’ here bears a semblance to that of ‘bu (不)’, albeit in a more indirect form.

Using ‘busy’ as a reason

In Chinese discourse, employing ‘no time (meiyou shijian 没有时间)’ as a pretext is a prevalent strategy for refusal. This refusal tactic hinges on furnishing objective reasons, a practice that typically obviates the need for intricate pragmatic inference to discern the refusal’s implication in everyday conversations. Particularly, while forms featuring negative markers like ‘no time (meiyou shijian 没有时间)’ explicitly convey negation, forms lacking such markers, such as ‘busy (mang 忙)’, also carry a negative connotation and are frequently deployed for refusal. This nuanced interplay between linguistic expressions and refusal strategies is exemplified in the following instance:

(Original sentence in the source language)

刘慧芳: 早点回来啊。

王沪生 : 今天所里有事儿, 孩子你接一下吧。(电视剧《渴望》).

王沪生: 对, 我就知道人无事不登三宝殿, 别废话, 没啥好的, 炒俩鸡蛋边吃 边谈, 好吗?

小马: 我还有事呢。(电视剧《渴望》).

(Morpheme-by-morpheme gloss (word-for-word translation))

Liu Huifang: Come back early.

Wang Husheng: There is something to do in the institute today, so please pick up our kid. (TV series ‘Longing’).

Wang Husheng: Yes, I know this guy never goes to the temple for no reason. Don’t talk nonsense, there is nothing good, just eat and talk with scrambled eggs, okay?

Xiao Ma: I still have something to do. (TV series ‘Longing’).

Examples (10) and (11) illustrate rejection through the emphasis on the objective constraints, namely, the presence of other engagements denoted by ‘have got something to do.’ In contrast to forms marked with negative indicators, this expression adopts a more implicit and indirect approach to refusal. Following the principle that greater linguistic indirectness correlates with increased politeness, these constructions are deemed more courteous than their negated counterparts. Particularly, the subjects in these refusals need not exclusively be first-person pronouns, as demonstrated in example (10). Utilizing objective factual grounds as primary rationale, these refusals commonly employ the modal particle ‘ne (呢)’ at the sentence’s conclusion to accentuate the veracity of the stated reasons, as evidenced in example (11). The modal particle ‘ne (呢)’ is frequently accompanied by ‘Hai (还)’ at the sentence’s onset, a structure elucidated by Lu (1999, p. 413) as emphasizing objective justifications during refusal. By foregrounding objective rationale, the speaker’s subjective volition is diminished in refusal acts, thereby mitigating emotional contention between conversational parties and rendering the refusal more diplomatically expressed.

Despite examples (10) and (11) contravening Grice’s maxim of quantity (Grice et al., Citation1975), they remain consistent with the politeness principle’s dictates. Beyond ‘hai (还)…ne (呢)’, adverbs such as ‘really (zhen 真)’ are commonly enlisted in this form of rejection to accentuate the authenticity of objective reasons, as in ‘Wo zhen youshi (I really have something to do)’ or ‘Jintian suoli zhen youshi. (Today there is really something to do in the office)’, among others. Furthermore, the addition of ‘shi (是)’ before ‘zhen (真)’ serves to intensify emphasis, as in ‘Wo shi zhen youshi. (I really have something to do).’ According to relevance theory (Sperber & Wilson, Citation1986, Citation1995), in examples (10) and (11), upon hearing the refusal reason ‘youshi (有事)’, hearers or the individuals being refused can readily infer that the speakers are unable to fulfill the requested task. This inference arises from combining contextual assumptions—that if someone has other engagements, they are unable to comply with the hearers’ requests—with the new information provided by the speakers. Consequently, implicated conclusions are drawn, indicating that the speakers have declined the requested action.

Time delay

Indirect speech acts expressing time delay

In addition to employing expressions such as ‘no time (meiyou shijian 没有时间)’ and ‘busy (mang 忙)’ to convey refusal, time delay serves as another prevalent strategy in Chinese discourse for refusal (Liao & Bresnahan, Citation1996). The introduction of a time delay provides a buffer for the hearers, thereby rendering the refusal less confrontational to their face compared to a direct refusal based on busyness. While this classification primarily revolves around semantic distinctions, several conventional forms for time delay are identifiable. Particularly, many of these expressions lack negative markers and have evolved into established methods of refusal, even in isolation from additional clauses or sentences. Phrases such as ‘later (yihou zaishuo 以后再说)’, ‘some other day (gaitianba 改天吧)’, ‘after some days (guo liangtian 过两天)’, ‘next time (xiahui ba 下回吧)’, and ‘wait for a moment (dai huir 待会儿)’ can function independently or within various contextual frameworks to convey refusal. For instance:

(Original sentence in the source language)

张大民: 云芳, 咱哪天领老人和孩子上香山玩儿玩儿去?

李云芳: 以后再说吧。(电视剧《贫嘴张大民的幸福生活》).

刘梅 : 你说看什么呀?刘星送我的礼物呀, 快点儿!

夏东海: 过生日的时候再看。走, 吃饭去, 吃饭去。(电视剧《家有儿女》).

刘燕 : 不价!妈给你的饭都做得了!

宋大成 : 下回吧!今儿厂里真有事儿!(电视剧《渴望》).

刘小芳: 那人家马上要用呢?

刘燕 : 过两天他来了,你自个儿说!(电视剧《渴望》).

(Morpheme-by-morpheme gloss (word-for-word translation))

Zhang Damin: Yunfang, when shall we take the elderly and kid to Xiangshan to play?

Li Yunfang: Let’s talk about it later. (TV series ‘The Happy Life of Zhang Damin’).

Liu Mei: Don’t you know what I want to see? (I want to see)the gift Liu Xing sent to me. Hurry!

Xia Donghai: Let’s see it on your birthday. Go, go eat, go eat. (TV series ‘Family with Children’).

Liu Yan: No. Mom has finished cooking the meal for you!

Song Dacheng: Next time! There is an issue in the factory today really! (TV series ‘Longing’).

Liu Xiaofang: Will I need to use it soon?

Liu Yan: When he comes in some days, you’d better ask him yourself. (TV series ‘Longing’).

Based on the example sentences, future time expressions can function independently or in conjunction with predicate components to convey refusal. When paired with predicate elements, the adverb ‘zai(再)’ frequently precedes the predicate verbs in these refusals. For instance, in examples (12) and (13), the speaker may append ‘zai(再)’ to the responses, as demonstrated in ‘Guoliangtian zai chi(过两天再吃)’ and ‘Guolaingtian ta lai le, ni zai ziger shuo(过两天他来了, 你再自个儿说)’. The actions following ‘Zai(再)’ are anticipatory, and due to their frequent use, certain verbs in these structures have undergone semantic bleaching. For instance, in ‘… let’s talk … later(zaishuoba再说吧)’, the verb ‘Shuo(说)’ no longer exclusively denotes speaking or saying. When employing the sensory verb ‘kan(看)’ in a similar construction as ‘shuo(说)’, the meaning may be interchangeable, as demonstrated in example (12). However, in example (13), where ‘kan(看)’ is utilized to defer the action, the verb retains its original meaning. Certain other sensory verbs, including ‘listen(ting听), think(xiang想), transmit(chuan传), speak(jiang讲), read(nian念), and ask(wen问)’, retain their semantic integrity when employed in such structures. Even for the sensory verbs ‘say(shuo说)’ and ‘see (kan 看)’, semantic bleaching typically occurs only when the future time component is directly followed by the verb (phrases). When these verbs are part of a clause followed by a subordinate clause, such as in example (15), they still retain their action-oriented meanings.

Time indicators in Chinese denoting future events exhibit diverse forms, encompassing both nouns and adverbs, such as ‘later(yihou以后)’, ‘tomorrow(mingtian明天)’, and ‘some other day(gaitian改天)’, as well as phrases or clauses like ‘next time(xiahui下回)’, ‘in a moment(daihuir待会儿)’, and ‘in another day (guo liangtian过两天)’. The verb ‘deng(等)’ can be paired with these words, phrases, or clauses to signify future time. For instance, when ‘deng(等)’ is prefixed to the beginning of the response as seen in examples (12–15), it yields the following sentences:

(Original sentence in the source language)

等以后再说吧。

等过生日的时候再看。

等下回吧

等过两天。

(Morpheme-by-morpheme gloss (word-for-word translation))

Let’s talk about it later.

Wait until the birthday.

Wait for the next time.

Wait for another days.

Examples (16–19) illustrate instances where the future timeframe is denoted, incorporating the verb ‘deng(等)’ to delineate an anticipated period ahead. However, the term ‘deng(等)’ (wait) can also be combined with other words that do not inherently imply future time, thereby representing a specific temporal occurrence in the future. For instance:

(Original sentence in the source language)

等(……)写完再去。Footnote4

等(……)回来了再说。

(Morpheme-by-morpheme gloss (word-for-word translation))

Wait for (…) to finish writing before going.

Wait until (…) comes back.

In examples (20) and (21), the inclusion of ‘wait(deng等)’ alongside other verbs forms serial-verb constructions, employed to defer and decline. However, the adjuncts attached to ‘wait(deng等)’ do not inherently denote temporal indications. For instance, ‘(…) finished writing (xiewan 写完)’ in example (20) merely states a factual completion without temporal reference. From a pragmatic standpoint, both instances (20) and (21) represent indirect refusals through commissives or directives.

It is crucial to acknowledge that whether ‘wait…(deng等)’ is followed by other verb phrases to construct serial-verb constructions or not, its presence is acceptable. For instance, examples (20) and (21) would still convey rejection even without ‘wait…(deng等)’—yet if ‘wait…(deng等)’ were used in isolation without accompanying verb phrases to form serial-verb constructions, the inclusion of ‘to wait(deng等)’ becomes imperative. In other words, phrases like ‘finished (xiewan 写完)’ and ‘come back(huilai回来)’ in examples (20–21) do not inherently suggest future temporal constraints, hence they cannot serve as rejections independently without the verb ‘deng(等)’. When ‘to wait(deng等)’ takes a clause or a verb phrase as its object, the auxiliary word ‘de(的)’ may be appended to the sentence’s end, as seen in ‘waiting (for me) to finish writing(Deng(wo)xie wan de.等我写完的)’ and ‘waiting (for him) to come back first(Deng(ta)huilai de.等他回来的)’, thereby elucidating a clear time delay and serving as a means of refusal.

Two types of refusals on grounds of time delay

Refusals grounded in time delay can be categorized into two distinct types: genuine reasons and customary pretexts. Genuine reasons entail conditional acceptance (Liao & Bresnahan, Citation1996), whereas customary pretexts often signify outright rejection. In the case of customary refusals, although the postponement of time is acknowledged in a literal sense, recipients (i.e. those being refused) typically do not require intricate pragmatic inference to grasp the refusal’s meaning during actual discourse. The temporal expressions used in these refusals have undergone semantic bleaching, no longer specifying a precise future timeframe. However, delineating between the two classifications is not always straightforward. For instance, phrases like ‘in other days (guoliangtian 过两天)’ and ‘another day (gaitian 改天)’ may serve as genuine explanations for the delay or merely imply a customary refusal. This can be illustrated through the following example:

(Original sentence in the source language)

刘燕: 罗老师您下午不是没事吗?去我们家坐坐!

罗冈: 改天吧, 我送稿子一定去!(电视剧《渴望》).

(刘慧芳母亲留宋大成吃饭)

宋大成: 大妈, 车间有事儿, 改日吧!(电视剧《渴望》).

(Morpheme-by-morpheme gloss (word-for-word translation))

Liu Yan: Teacher Luo, you are available this afternoon, aren’t you? Come and sit at our house!

Luo Gang: Another day, if I submit the manuscript, I will go! (TV series ‘Longing’).

(Liu Huifang’s mother invites Song Dacheng to stay for dinner during his visit.)

Song Dacheng: Aunt, there is something to do in the workshop. Let’s wait another day!.

(TV series ‘Longing’).

In examples (22) and (23), the phrase ‘another day (gaitian/gairi改天/改日)’ signifies refusal through the postponement of time. However, it is noteworthy that while declining the hearer’s invitation in example (22), the refuser also commits to accepting the invitation at a specific time in the future. Conversely, in example (23), ‘another day (gairi改日)’ lacks a specific time reference; it functions merely as an idiomatic expression in Chinese implying refusal. Despite violating the maxim of quality (Grice et al., Citation1975) by uttering something known to be false in example (23), the speaker (refuser) mitigates the threat to the hearer’s face, primarily prioritizing politeness for pragmatic purposes. Such refusals have limited correlation with actual time delays in meaning.

Conditional acceptance

Conditional acceptance encompasses situations where individuals do not outright decline the ‘behaviors/actions’ prompting certain acts, but instead reject the manner, timing, or location associated with executing these ‘behaviors/actions’. Moreover, negotiations regarding the quantity of items also fall within this realm of refusals. Conditional acceptance may be conveyed through explicit words or phrases, or it may necessitate inference based on contextual cues. For instance:

(Original sentence in the source language)

刘梅 : 哎, 你快给他装上啊!

夏东海 : 我, 我准备先吃饭去啦。(电视剧《家有儿女》).

狂野男孩: 夏雪呀, 你现在就告诉我怎么做那道题了吧。

夏雪 : 现在还不行。(电视剧《家有儿女》).

李云芳 : 给你几个西红柿。

李大妈 : 行了, 行了, 够做个汤就行了。(电视剧《贫嘴张大民的幸福生活》).

刘梅 : 夏东海!给你茶!

夏东海 : 给我吧。.

刘梅 : 你过来拿。(电视剧《家有儿女》).

(Morpheme-by-morpheme gloss (word-for-word translation))

Liu Mei: Hey, put it for him quickly!

Xia Donghai: I, I’m going to eat first. (TV series ‘Family with Children’).

Wild Boy: Xia Xue, tell me now how to do that question.

Xia Xue: Not yet. (TV series ‘Family with Children’).

Li Yunfang: Here are some tomatoes for you.

Aunt Li: All right, all right, enough to make soup is ok. (TV series ‘The Happy Life of Poor Zhang Damin’).

(Liu Mei: Xia Donghai! Tea for you!)

Xia Donghai: Give it to me.

Liu Mei: Come here and get it. (TV series ‘Family with Children’).

In example (24), speaker ‘Xia Donghai’ did not outright reject the prior instruction from the hearer ‘Liu Mei’, but rather declined to do so ‘quickly.’ In example (25), ‘Xia Xue’ declined to inform the hearer ‘now’, yet did not refuse to provide the information at a later time. In example (26), the conversation involved an ‘offer-refusal’ dynamic. While the latter part of the exchange indirectly rejects the offer through dissuasion (‘All right, all right’), the subsequent explanation by ‘Aunt Li’ indicates a reservation regarding the quantity of the offer rather than a complete refusal. In example (27), the speaker/refuser ‘Liu Mei’ declined her husband’s request not to provide items to the other party, but rather refused the method of delivery by stating ‘Come here and get it (Ni guolai na. 你过来拿).’ This indirect refusal is conveyed through instructions, showcasing a strategy of offering a new suggestion or method. While the tone of the imperative sentence used for refusal may seem assertive and impolite, it remains appropriate in the context of a conversation between spouses. From the perspective of the rejected party ‘Xia Donghai’, his request ‘give it to me (gei wo ba 给我吧)’ is based on the prior behavior of ‘Liu Mei’, leading to the cognitive assumption that ‘Liu Mei will provide him with water (Liu Mei hui na gei ta shui).’ However, the introduction of new information ‘Come and get it (ni guolai na)’ alters his cognitive context. Based on this, ‘Xia Donghai’ forms a new contextual assumption that ‘Liu Mei asked me to come and get it’, leading to the implicit premise ‘If Liu Mei asked me to come and get it, then she would not bring me water’, and subsequently inferring the implicit conclusion ‘Liu Mei won’t give me water.’

Ellipsis

Ellipsis in discourse represents a common method of refusal in Chinese communication. From the perspective of refusal strategies, ellipses primarily employ avoidance and hesitation tactics (Liao & Bresnahan, Citation1996). By omitting the central part of the refusal, speakers can significantly mitigate the potential threat to the hearer’s face, thereby offering a polite refusal. In such instances, only the subjects are explicitly mentioned while the predicates are omitted. These refusals, realized through ellipses, are context-dependent and would be incomprehensible without proper context. For instance:

(Original sentence in the source language)

刘梅 : 哎哎哎, 等会儿, 这是小雪的假条儿, 你别忘了交给他们老师啊。

刘星 : 她的事儿……(电视剧《家有儿女》).

王亚茹 : 真的!你可别稀里糊涂的, 我不是让你帮沪生一块儿搞搞突击吗?你 抓紧点儿……

肖竹心 : 亚茹姐, 我……(电视剧《渴望》).

玛丽 : 没关系。一会儿我带他们去饭店吃。

刘梅v : 这……(电视剧《家有儿女》).

(Morpheme-by-morpheme gloss (word-for-word translation))

Liu Mei: Hey, wait a minute, this is Xiaoxue’s note. Don’t forget to give it to her teacher.

Liu Xing: Her matter… (TV series ‘Family with Children’).

Wang Yaru: Really! Don’t be confused. Didn’t I ask you to help Husheng bone up on (something)? So, hurry up…

Xiao Zhuxin: Sister Yaru, I… (TV series ‘Desire’).

Mary: It’s okay. After a while, I will take them to a restaurant to eat.

Liu Mei: This… (TV series ‘Family with Children’).

The ellipses observed in (28–30) reflect the speakers’ tentative attitudes towards actions they can perform. Despite violating the criterion of quantity and providing insufficient information due to ellipses, these utterances demonstrate a greater degree of politeness as they consider the hearer’s face (the rejected party). While the main components of the refusal are omitted, hearers can still infer the intended meaning through existing contextual assumptions and the new relevant information provided by the speakers.

Taking (28) as an illustration, the existing contextual assumption of the hearer, ‘Liu Mei’, is that ‘Liu Xing’ is both capable and willing to assist ‘Xia Xue’ in delivering the leave note. When ‘Liu Xing’ contradicts this assumption by providing new information, ‘Liu Mei’ can infer from his words that ‘Liu Xing is unwilling’, thereby concluding that ‘Liu Xing has refused to assist.’ Similarly, in examples (29) and (30), the hearers can deduce the refusals from the speakers’ utterances, a process analogous to that in example 28. However, the structure of the omitted part slightly differs in examples (29) and (30). In example (28), the omitted predicate part is a subject-predicate phrase, which could be completed as ‘I don’t care about her affairs (她的事我不管)’, with ‘her affairs (她的事)’ serving as the focal point of the refusal behavior. Conversely, in examples (29) and (30), the omitted predicate part expressing refusal could be supplemented with phrases such as ‘I + not very convenient/I + have no time (我+不太方便/我+没有时间)’ or ‘this + is not suitable (这+不合适)’, among others.

In specific contexts, Chinese speakers frequently employ ellipsis to convey refusals solely through an address, representing a condensed form of communication. Unlike the instances depicted in examples (28–30), where only the predicate part is omitted, these ellipses entail the omission of entire propositions, including the subjects. This form of communication streamlines the refusal process, minimizing verbosity while conveying the intended message succinctly. For instance:

(Original sentence in the source language)

刘母 : 难得你们仨人儿凑一块儿, 今儿明人不做暗事, 把这无头的官司说道 说道……

刘慧芳: 妈……(电视剧《渴望》).

王子涛: 你!你快去把他给我接回来!

王沪生: 爸爸……(电视剧《渴望》).

夏东海: 来吧, 把偷偷配的家里钥匙给我拿出来。

刘星 : 老爸!(电视剧《家有儿女》).

(Morpheme-by-morpheme gloss (word-for-word translation))

Mother Liu: It’s rare for the three of you to get together. And an honest man doesn’t do anything underhand. Today Let’s talk about this thing that has no clue or understanding.

Liu Huifang: Mom… (TV series ‘Desire’).

Wang Zitao: You! Hurry up and bring him back to me!

Wang Husheng: Dad… (TV series ‘Desire’).

Xia Donghai: Come on, bring out the spare keys you secretly made for the house.

Liu Xing: Dad! (TV Series ‘Family with Children’).

In example (31), the address ‘ma’ followed by ellipses serves to decline the request to ‘shuodaoshuodao.’ Similarly, examples (32) and (33) demonstrate analogous patterns, wherein the function of the addresses is refusal. When employing an address, the speaker intends to decline a request or plea with a firm tone. Such refusals are typically more prevalent in interactions where there exists a close relationship between the interlocutors, but they may not be suitable for formal discourse or exchanges between individuals with significant social distance. For instance, in example (29), the sole use of ‘Sister Yaru’ to refuse would be deemed inappropriate. However, it’s essential to note that this form of refusal is infrequently employed in discourse based on collected corpora. In most instances, addresses are combined with other elements to articulate refusal collectively. These may include standalone negations like ‘no’, ‘forget’, rhetorical questions, imperative sentences, among others. Apart from serving as deictic markers to reference the hearer (the one being refused), addresses also contribute to fostering a close relationship between speakers and hearers during conversation, aligning with principles and strategies of politeness.

Conclusion

While previous research predominantly delved into the role of politeness in indirect refusals, our study reveals that politeness may also play a significant role in direct refusals, as evidenced by corpus analysis. This stresses the hierarchical nature of politeness; wherein successful refusal implementation necessitates adherence to appropriateness criteria. Although this paper has outlined and analyzed five common forms of refusal in Chinese, each reflecting distinct refusal strategies, they all give emphasis to the importance of politeness. Consequently, this analysis not only offers a systematic and pertinent explanation of refusal patterns in Chinese but also contributes to the broader literature on politeness principles and strategies.

Acknowledgment

The authors extend their gratitude to Assistant Professor Dr. Budi Waluyo, Assistant Professor Dr. Wararat Whanchit, and Assistant Professor Dr. Thanapas Dejpawuttikul, for the invaluable comments and suggestions that greatly improved this work. The final version of the aricle is possible due to all reviewers’ comments. However, all errors should be us.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ying Li

Li Ying has a Bachelor of Chinese Minority Language and Literature from Minzu University of China, a Master and a Doctor of Linguistics and Applied Linguistics from Communication University of China. After finishing her master’s degree, Li Ying was appointed to teach Chinese as a second language in Beijing Language and Culture University during which time she had a chance to be an international Chinese volunteer teacher at Confucius Institute at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, Korea. After that, she obtained her Ph.D. degree, and became a full-time lecturer at Civil Aviation Flight University of China, Air Crew Academy, specializing in teaching modern Chinese. Later, she relocated to Guizhou University, College of International Education to teach Chinese as a second language. Her research interests include Chinese syntax, discourse analysis and second language acquisition.

Wari Wongwaropakorn

Wari Wongwaropakorn has a Bachelor of Arts in Chinese Language from Prince of Songkla University, a Master of Arts in Linguistics and Applied Linguistics from Guangxi Normal University, and a Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics and Applied Linguistics from Communication University of China. After finishing her bachelor’s degree, Wongwaropakorn obtained a full-time lecturer position at Walailak University, Department of Chinese Language under the School of Education and Liberal Arts. After that, she chose to seek a Master’s Degree and Ph.D. Her research interests include pragmatics, semantics, discourse analysis, Chinese Grammar and second language acquisition. She hopes that her expertise will contribute to enhancing Chinese language instruction in Thailand.

Notes

1 The additional question “xingma(行吗)” here means confirmation, not cross-examination.

2 Examples (7b) is written according to (7a).

3 Example (8) is written by the author.

4 Example (20, 21) is written by the author. The parentheses and ellipsis indicate whether the subject appears or not, and the person of the subject cannot be the first person form.

References

- Allami, H., & Naeimi, A. (2011). A cross-linguistic study of refusals: An analysis of pragmatic competence development in Iranian EFL learners. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.07.010

- Beebe, L. M., Takahashi, T., & Uliss-Weltz, R. (1990). Pragmatic transfer in ESL refusal. In R. Scarcella, E. Andersen, & S. D. Krashen (Eds.), The development of communicative competence in a second language (pp. 55–73). Newbury House. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587180

- Buckledee, S. J. (2020). "Collect a thousand loyalty points and you get a free coffin". Creative impoliteness in the TV comedy drama Doc Martin. Pragmatics & beyond. New Series, 312, 248–269. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.312.11buc

- Chang, H. C. (2001). Harmony as performance: The turbulence under Chinese interpersonal communication. Discourse Studies, 3(2), 155–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445601003002001

- Chang, Y. F., & Ren, W. (2020). Sociopragmatic competence in American and Chinese children’s realization of apology and refusal. Journal of Pragmatics, 164, 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445601003002001

- Chelliah, S. L., Burke, M., & Heaton, M. (2021). Using interlinear gloss texts to improve language description. Indian Linguistics, 82(1-2), 10383818.

- Chen, X., Ye, L., & Zhang, Y. (1995). Refusing in Chinese. In G. Kasper (Ed.), Pragmatics of Chinese as native and target language (pp. 121–161). University of Hawaii at Manoa. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.1998.0221

- Chintawidy, P. A., & Sartini, N. W. (2022). A cross-cultural pragmatics study of request strategies and politeness in Javanese and Sundanese. Journal of Pragmatics Research, 4(1), 152–166. https://doi.org/10.18326/jopr.v4i2.152-166

- Culpeper, J. (2011). 13. Politeness and impoliteness. Pragmatics of Society, 5, 393–438. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110214420.393

- Dong, P. (1999). Refusals in Chinese. Journal of Baicheng Normal University, 2, 22–23.

- Du, Y., He, H., & Chu, Z. (2024). Cross-cultural nuances in sarcasm comprehension: a comparative study of Chinese and American perspectives. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1349002. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1349002

- Eslami, Z. (2005). Invitations in Persian and English: ostensible or genuine? Interculture Pragmatics, 2(4), 453–480. https://doi.org/10.1515/iprg.2005.2.4.453

- Fauziyah, L. Q., Djatmika, D., & Nugroho, M. (2024). The influence of character traits to the politeness using on serial Drama Losmen Bu Broto. International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding, 11(2), 339–345. https://doi.org/10.18415/ijmmu.v11i2.5390

- Grice, H. P. (1975). Logic and conversion. Cole et al, syntax and semantics 3: Speech acts[C] (pp. 41–58). Harvard University Press.

- Gu, Y. G. (1990). Politeness phenomena in modern Chinese. Journal of Pragmatics, 14(2), 237–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(90)90082-O

- Gu, Y. G. (1992). Politness, pramatics and culture. Foreign Language Teaching and Research, 4(2), 10–17.

- Hargie, O. (2021). Skilled interpersonal communication: Research, theory and practice. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003182269

- He, Z. R., & Ran, Y. P. (2002). Introduction to pramatics (Revised Edition). Hunan Education Press.

- House, J., & Kádár, D. Z. (2023). An interactional approach to speech acts for applied linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2022-0116

- Isabella, R. A., Munthe, E. J. B., Sigalingging, D. J. N., Purba, R., & Herman, H. (2022). Learning how to be polite through a movie: A case on Brown and Levinson’S politeness strategies. Indonesian EFL Journal, 8(2), 147–154. https://doi.org/10.25134/ieflj.v8i2.6438

- Jakučionytė, V. (2020). Cross-cultural communication: Creativity and politeness strategies across cultures. A comparison of Lithuanian and American cultures. Creativity Studies, 13(1), 164–178. https://doi.org/10.3846/cs.2020.9025

- Jaspers, J. (2023). Interactional sociolinguistics and discourse analysis. In The Routledge handbook of discourse analysis (pp.85–97). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203809068

- Jia, M., & Yang, G. (2021). Emancipating Chinese (im) politeness research: Looking back and looking forward. Lingua, 251, 103028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2020.103028

- Kádár, D. Z., & House, J. (2021). ‘Politeness markers’ revisited-a contrastive pragmatic perspective. Journal of Politeness Research, 17(1), 79–109. https://doi.org/10.1515/pr-2020-0029

- Kapoor, S. (2022). “Don’t act like a Sati-Savitri!”: Hinglish and other impoliteness strategies in Indian YouTube comments. Journal of Pragmatics, 189, 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2021.12.009

- Kasper, G. (2006). Speech acts in interaction: Towards discursive pragmatics. Pragmatics and Language Learning, 11,281–314. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojml.2020.101002

- Kuhn, J. (2019). Computational text analysis within the Humanities: How to combine working practices from the contributing fields? Language Resources and Evaluation, 53(4), 565–602. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10579-019-09459-3 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10579-019-09459-3

- Lee, C. (2016). Understanding refusal style and pragmatic competence of teenage Cantonese English learners in refusals: An exploratory study. Intercultural Pragmatics, 13(2), 257–282. https://doi.org/10.1515/ip-2016-0010

- Leech, G. N. (1983). Principles of pragmatics. Longman.

- Leech, G., & Tatiana, L. (2014). Politeness: West and east. Russian Journal of Linguistics, 18(4), 9–34. https://journals.rudn.ru/linguistics/article/view/9380

- Li, J., & Cao, Q. (2011). Hanyu yaoqing xingwei de hualun jiegou moshi fenxi (Patterns of conversational turns of invitations in Chinese context). Yuyan Wenzi Yingyong [Appl. Ling.], (4), 44–53. https://doi.org/10.16499/j.cnki.1003-5397.2011.04.008

- Li, Y., & Guo, X. Y. (2021). Speech acts of refusals expressed by the negative imperative sentences in Chinese. The Journal of Society for Humanities Studies in East Asia (저널이름), 54, 233–248.

- Liao, C. C., & Bresnahan, M. I. (1996). A contrastive pragmatic study on American English and mandarin refusal strategies. Language Science, 18(3-4), 703–727. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0388-0001(96)00043-5

- Lii-Shih, Y.-H. (1994). What do “Yes” and “No” really mean in Chinese? In: Alatis, J. (Ed.), Educational linguistics, crosscultural communication, and global independence. Georgetown University Press. 128–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2020.03.007

- Lingling, Y., & Chuanmao, T. (2020). Comparative analysis of the refusal language between 2 broke girls and ode to joy. International Journal of English Literature and Social Sciences, 5(6), 1851–1859. https://doi.org/10.22161/ijels.56.10

- Liu, S. (2011). An experimental study of the classification and recognition of Chinese speech acts. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(6), 1801–1817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.10.031

- Lu, S. X. (1999). 800 words in modern Chinese (Revised Edition). The Commercial Press.

- Mao, L. R. (1994). Beyond politeness theory: ‘Face’revisited and renewed. Journal of Pragmatics, 21(5), 451–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(94)90025-6

- Ojukwu, C. K., & Dike, C. J. (2023). Politeness strategies and face-threatening acts in master-servant relationships in selected wole Soyinka and William Shakespeare’S drama texts. IKENGA International Journal of Institute of African Studies, 24(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.53836/ijia/2023/24/1/008

- Pan, Y., & Kádár, D. Z. (2011). Historical vs. contemporary Chinese linguistic politeness. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(6), 1525–1539.), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.10.018

- Pandharipande, R. (1992). Defining politeness in Indian English. World Englishes, 11(2-3), 241–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-971X.1992.tb00068.x

- Pizziconi, B. (2003). Re-examining politeness, face and the Japanese language. Journal of Pragmatics, 35(10-11), 1471–1506. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(02)00200-X

- Qiu, J., Chen, X., & Haugh, M. (2021). Jocular flattery in Chinese multi-party instant messaging interactions. Journal of Pragmatics, 178, 225–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2021.03.020

- Ran, Y. P., & Lai, H. D. (2014). A study of the interpersonal pragmatic motivations of ostensible refusals. Journal of Foreign Languages, 2, 65–70. https://doi.org/10.16263/j.cnki.23-1071/h.2014.02.017

- Ren, W., & Woodfield, H. (2016). Chinese females’ date refusals in reality TV shows: Expressing involvement or independence? Discourse, Context and Media, (13), 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2016.05.008

- Salman, H. S., & Betti, M. J. (2020). Politeness and face threatening acts in Iraqi EFL learners’ conversations. Glossa, 3(8), 221–233.

- Scollon, R., & Scollon, S. W. (2001). Intercultural communication: A discourse approach. Blackwell.

- Searle, J. R. (1979/2001). Expression and meaning. Foreign Language Teaching and Research.

- Sperber, D., & Wilson, D. (1986). Relevance: Communication and cognition. Blackwell.

- Sperber, D., & Wilson, D. (1995). Relevance: Communication and cognition (2nd ed.). Blackwell.

- Su, Y. (2020). Yes or no: Ostensible versus genuine refusals in Mandarin invitational and offering discourse. Journal of Pragmatics, 162, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2020.03.007

- Takimoto, M. (2020). Investigating the effects of cognitive linguistic approach in developing EFL learners’ pragmatic proficiency. System, 89, 102213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102213

- Wiedemann, G. (2016). Text mining for qualitative data analysis in the social sciences. Springer Vs.