Abstract

This article discusses the use of language in primary schools in Kupang, East Nusa Tenggara (ENT), Indonesia, to reveal the representation of national, foreign, and local languages in the public space of primary schools as a form of implementing several language policies in primary education institutions within the framework of the linguistic landscape approach. This approach is based on the understanding that the use of language in an educational environment is for language learning in the early stages of a child’s language learning. Data was obtained through observation, interviews, and documentation studies of language policies. Data was found for 998 photos consisting of four languages: Indonesian, English, Arabic, Kupang Malay, and Spanish. The results of the research show that the strength of Indonesia is related to the implementation of the national curriculum; the use of English is because it belongs to local content subjects, Arabic is found only in private schools under the funding of the Muslim Foundation, while Spanish is found in schools under the Catholic Foundation to symbolize the origin country of the school’s congregation founder. There is limited use of local languages in LL primary schools indicating the marginalization of local languages in the education ecology in Kupang. It is hoped that this study can provide meaningful input for local government regarding the importance of ENT local language policies in the educational environment as formal support for the revitalization program of local languages through education and helping students learn to read or write at an early stage.

Reviewing Editor:

Introduction

Kupang is a capital city of East Nusa Tenggara (ENT) province, Indonesia. It is the final destination for immigrants from sixteen tribes of ENT and other tribes in Indonesia. In the 2023 cencus, the population of Kupang was 444.661, Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS) Provinsi Nusa Tenggara Timur (2023). The citizen of Kupang city is from the local tribe in ENT such as Dawan, Helong, Rote, Sabu, Sumba, Alor, and Flores, and the other tribe outside ENT such as Jawa, Cina, Bugis, Manado, Ambon, Arab, dan Timor Leste, Rafael A.M.D (Citation2019). Kupang has grown into a contemporary metropolis. It comprises numerous business, commercial, residential, and educational districts in eastern Indonesia.

Even though the city is increasingly developing in all aspects, culturally, some of Kupang’s residents still maintain the use of local languages in domestic domains, traditional events, and religious rituals, Rafael (Citation2019). The young generation in Kupang (born in 1990) is bilingual, and some are multilingual (Benu et al., 2023; Rafael, Citation2019). Some of their first languages are Kupang Malay or other local languages as their mother tongue, such as Dawan, Rote, Sabu, or Helong languages (Benu et al., 2023; Doko et al., 2021). Their second language is Indonesian, while English recently became the third language spoken by some children in Kupang, as English is one of the compulsory subjects in some primary schools and the mandatory subject starting from junior school until university, Benu et al. (2023).

Moreover, most Kupang citizens use Indonesian in official settings, while Kupang Malay is the lingua franca in daily communication among citizens from different tribes, Rafael (Citation2019) and Jacob and Grimes (Citation2011). Furthermore, the languages of Kupang Malay and the local ENT are utilized not just for verbal communication in daily interactions but also for displaying information on signage in public areas within Kupang city (Benu et al., 2023). In Kupang city’s public spaces, there are four ENT locales featured on public signs for language selection: Dawan Malay, Sabu, Rote, and Kupang Malay. There is no question regarding the presence of the four languages in the public spaces of Kupang City, as they have been spoken by tribes long before the city existed in its current form.

The use of language in public spaces is regulated in Law Number 24 of Citation2009. This regulation regulates four main elements: the state flag, language, symbol, and national anthem. Based on this regulation, Indonesia dominates 15 specific fields, including state documents, speeches, educational introductions, public services, agreements, official communications, reports, scientific works, geographical names, building names, trademarks, information on goods/services, the public signs, and mass media communication. Regional and foreign languages can be used in public signs, but Indonesian is still preferred.

Regarding efforts to develop, foster, and protect the local language, Law Number 24 of Citation2009 gives local governments the authority and obligation to handle local language and literature. The Minister of Education and Culture also introduced the Local Language Revitalization initiative in 2022, through the 17th episode of the Independent Learning Curriculum. This endeavor was undertaken because numerous local Indonesian languages are facing extinction. Primary and secondary school students are the target audience for the revival. There are five local languages in 10 districts and one capital city in ENT province, which are the focus of language revitalization, namely Dawan, Manggarai, Kambera, Rote, and Abui. Kupang City is one of the language areas targeted to revitalize the Dawan language.

One of the strategies to revitalize the local language is through education; as stated by Duarte et al. (Citation2023), improving local Language awareness and societal position through education should be necessary, as students currently have rather negative attitudes towards locals. Duarte et al. (Citation2023) added that the schools could use the linguistic landscape (LL) to raise language awareness. LL has the potential for the mediation of students’ language attitudes. At the same time, it can be a valuable way to improve minority language education and the position of the minority language itself, Duarte et al. (Citation2023). On the other hand, the effectiveness of using local languages in school instruction can motivate and inspire students to continue learning that language at home, Jansen et al. (Citation2013).

Moreover, the languages in the school environment reflect the daily experiences of parents, teachers, students and the education system. Shohamy (Citation2006), Brown (Citation2012), Aronin and Laoire (Citation2012), and Amara (2018) suggest that language in schools reflects tolerance towards diversity and provides information about the sociopolitical environment. It also provides a visual depiction of the covert educational curriculum linked to language ideology (Amara, 2018; Aronin & Laoire, Citation2012; Brown, Citation2012; Shohamy, Citation2006). Language serves as a tool for teaching that permeates classrooms and school environments, bridging the gap between students’ personal lives and their communities outside of school, Hewitt-Bradshaw (Citation2014, p. 160). Learning the local language can enhance students’ understanding of the linguistic and cultural variety in the country, enabling them to positively grasp the diversity and dissimilarities present in themselves and their peers, Hewitt-Bradshaw (Citation2014, p. 160).

According to the primary research, the school curriculum needs to incorporate subjects in the local language. As per UNESCO (Citation2020), a sound education system is education for all children, considers their socio-cultural background, caters to students struggling with the national language in their early stages of learning, and values local knowledge. This study was carried out due to the intricate language ecology in the educational sector of Kupang. The main focus of this study is twofold: firstly, to determine the visibility of languages in primary schools in Kupang, and secondly, to analyze how the use of languages in these schools aligns with Indonesia’s language policy. This study aims to gather data on language ecology conditions representing language learning in multilingual education in Kupang, ENT province.

Studies related to public signs and the use of language in public signs are some of the most recent studies in sociolinguistics, namely Linguistic Landscape (LL). LL was first introduced by Landry and Bourhis (Citation1997). Landry and Bourhis (Citation1997) limit the area of language studies to the study of public road signs, billboards, street names, place names, shop names, tavern names, and government buildings in a region or city. Furthermore, Shohamy and Gorter (Citation2009) expanded the study area of LL by connecting language in the environment of words and images, which are contested in public spaces, where these signs become the center of attention in areas of rapid growth.

In 2005, Brown introduced language in the school landscape, known as ‘schoolscape.’ Brown studied the phenomenon of linguistic landscape in Southern Estonia. She saw that the Estonian government’s and schools’ efforts to foster regional identity in schools could have been more extensive. Learning local languages is not given space in Estonia’s school curriculum. Even contemporary schools in rural southeastern Estonia are set up deliberately to alienate students from their native cultural identity. Brown’s research is a decade of diachronic research. The results of Brown’s study also contribute to revitalizing the Voro language in schools in Southern Estonia today. Currently, schools in Estonia, especially kindergartens and primary schools, have provided space for revitalizing minority languages. Public signs using the local vernacular have been displayed in the corridors, foyers, entrances, and school museums. Even local languages have been included in the Estonian school curriculum. At the end of her research, Brown (Citation2012, p. 281) concluded that the reintroduction of minority languages in public school spaces must go through a language negotiation process that involves all parties. Brown (Citation2012, p. 281) states that ‘…school, a central civic institution, represents a deliberate and planned environment where learners are subjected to powerful messages about language(s) from local and national authorities.’

Numerous scholars have examined LL, language policies, and language vitality in the education field in several Indonesian cities. Andriyanti (Citation2019) looks at the representation of language situations in multilingual contexts, language use in education, and patterns of public space signs. This study discovered that Javanese is neglected, and Indonesian dominates the LL of senior high schools. The situation in the multilingual city of Yogyakarta is comparable to that of Kupang. In contrast, Yogyakarta has a local language policy controlling the use of local languages in public places, but Kupang does not.

Additionally, Auliasari (Citation2019) explores the language used in Surabaya’s public and private schools. The study revealed that LL in state junior high schools uses Javanese, English, Arabic, and Indonesian. Private junior high schools, on the other hand, only speak Greek, English, and Indonesian. However, this study must cover the language policy in the schools of Surabaya. Sinaga carried out research at the International School in Medan in 2020. The study revealed a correlation between the schools’ written language policy and the visibility of language use in the school’s public space. This study shows that schools can decide what language rules are taught in the classroom, which impacts how people speak in public school areas.

Benu et al. (Citation2023) offer more thought-provoking insights into the sustainability of local languages in Kupang. It shows the evolution of language in public environments, especially in local dialects. Benu found four indigenous languages in the ENT Province that can be heard in public areas of Kupang City, even though the local language is often ignored. The frequency of Dawan, Rote, Sabu, and KML is low compared to Indonesian. Discovering that these four languages are present in the linguistic environment of primary schools in Kupang is inherently interesting.

Although experts in the linguistic landscape (LL) have analyzed language use in school public spaces from various perspectives, there has yet to be a single LL study that critically highlights language visibility in primary school public spaces in ENT province, the eastern part of Indonesia, a multilingual region—related to language policies in education. This study is critical because it shows whether schools in Kupang accommodate the presence of a child’s first language as a form of the school’s obligation to create a child-friendly learning environment. Law no. 20 of 2003 concerning the National Education System contains regulations for the use of the mother tongue as the language of instruction in the early grades of primary school, which states, "regional languages can be used as the language of instruction in the early stages of education if necessary, in providing certain knowledge and skills.

This study also reveals the extent to which primary schools in ENT support the government’s program in revitalizing regional languages in the ETT region as stated in the Citation2015–2019 National Medium Term Development Plan (RPJMN) – known as Nawa Cita – Book II, in the section on curriculum empowerment and its implementation, which stated that: ‘…the curriculum must increase students’ various potentials, interests and intelligence, as well as provide opportunities to use their mother tongue, other than Indonesian, as the language of instruction in the teaching and learning process.’ Moreover, according to the Early Grade Reading Assessment of Students in Early Grade (EGRA, Citation2014), East Nusa Tenggara province is one of the five province in Indonesia that the students move on to grade III, with not meeting the criteria for promotion. This is due to reasons such as having trouble reading fluently despite understanding, reading slowly without comprehending, and being unable to read at all because they haven’t learned the letters even after two years of schooling.

Research method

This LL study is not 100% quantitative. As stated by Yendra and Ketut (Citation2020), ‘It is very wrong to conclude that LL research is solely characterized by quantitative, because the decision to determine an LL research approach depends on the nature of the research question.’ Observational data collection is the main instrument for capturing LL data in the form of photos. This method is in line with the LL studies conducted by Yavari, (Citation2012), David and Manan (Citation2015), Thai (Citation2019), Andriyanti (Citation2021), and Rohman and Wijayanti (Citation2023). The corpus comprises 998 data, as presented in and , and .

Table 1. Language visibility in LL of public primary schools in Kupang.

Table 2. Language visibility in LL of private primary schools in Kupang.

Photos of public signs are the primary data, while the secondary data is obtained through interviews conducted with the principal of each school. The interviews were conducted unstructured, with one example being asking if the use of Indonesian on school information boards served a particular purpose. The interviews’ findings were utilized as evidence to explore how language policy influences the visibility of language in public spaces. The results of the interviews were transcribed and used to reveal the reasons for using national languages, foreign languages, and local languages in public spaces in those schools.

The other secondary data is also collected from the documentation studies to complement interviews and observations. The study also acquires information by examining school rules documents such as the 2013 curriculum and independent learning curriculum, language policies in education, regulations by the Minister of Education and Culture in Indonesia regarding national, local and foreign language learning in primary schools, the 2020 National School/Madrasah Accreditation Instrument, and the school’s goals and objectives.

Thus, applying the observation method to answer the first problem regarding language use in the primary school landscape in Kupang, thus the documentation studies and interviews to answer the second problem related to the implementation of language policy in the schools public spaces.

The study was conducted in six primary schools in Kupang—located in the center of Kupang City. Purposive sampling with specific considerations is the way to select the research sites, as Sugiyono (Citation2017, p. 85) stated. The sample selection was purposefully made based on the necessary characteristics that represent the main population features, Arikunto (Citation2010, p. 183). The selected samples represented the population’s essential features, identified through through preliminary analysis.

With the heterogeneous sampling type consisting of state and private schools, accredited schools, and private schools consisting of Christian, Islamic, and Catholic private schools representing student backgrounds, purposive sampling captures various perspectives on our study. Purposive sampling was used to choose research sites based on specific criteria, such as the schools being in the center of Kupang City, because urban research influences the urban population as societal representatives showing diversity in social, ethnic, religious, economic, and linguistic aspects, according to Barni and Bagna (Citation2010) and Cenoz and Gorter (2006); accredited primary schools by the ENT Province National Schools/Madrasah Accreditation Board (now the National Accreditation Board for Early Childhood Education, primary, and secondary education in ENT Province); schools’ public spaces showing varying signs of public space representing primary schools in Kupang; implementing the recent national curriculum (Merdeka Belajar Curriculum) and the local content learning in their curriculum; state and private primary schools with over 5 years of establishment and students from diverse ethnic backgrounds were selected.

These schools are divided into two groups, namely state primary schools and private primary schools. This division helps researchers understand the phenomenon of language displays in public primary schools, which are always in line with the national curriculum and government language policies, and language displays in public spaces of private primary schools where private primary schools have their language policies for particular purposes, for example, commercialization or other purposes.

There are several limitations in conducting this research because investigating LL in educational settings is still a relatively recent focus of study, as noted by Cenoz and Gorter (Citation2008). This research focuses on the written public signage outside the classroom, which is visible to all school residents and the public. While public space signs consisting of only images or symbols are not a focus of analysis, as Backhaus (Citation2006, p. 55) noted, the LL study still captures all photographs of these signs, emphasizing the written text within a frame.

Findings

This section examine the quantity and variety of observable languages in the LL of primary schools in Kupang. In the research, the terms monolingual, bilingual, and multilingual adopted the linguistic landscape review procedure by Lai (Citation2012), David and Manan (Citation2015), and Andriyanti (Citation2021). These terms denote the presence of linguistic signs in public areas utilizing one, two, or more than two languages (multilingual). The study gathered a total of 998 data samples from both public and private primary schools in Kupang.

Based on , it can be shown that three public primary schools have monolingual displays in Indonesian, English, and Kupang Malay, while the other public signs t use two language codes with variations of Indonesian-English and English-Indonesian.

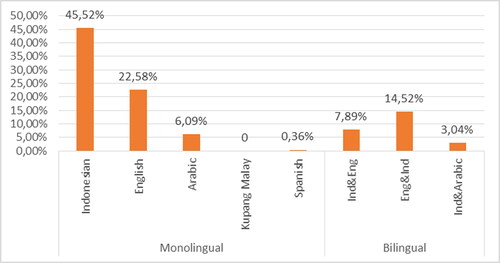

Three private primary schools have monolingual displays in their LL for Indonesian, English, Arabic, and Spanish. In the meanwhile, pairs of English-Indonesian, English-Indonesian, and Indonesian-Arabic are displayed in the bilingual language.

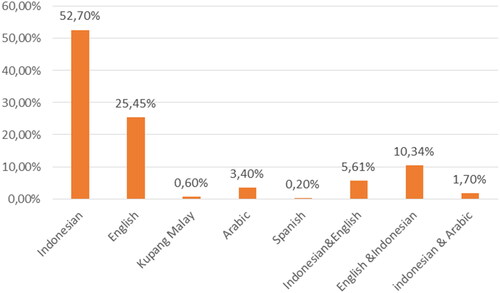

The entire LL data corpus of Kupang primary schools consists of monolingual and bilingual language displays. The following languages are displayed in monolingual form: Indonesia at 52.70%, English at 25.45%, Kupang Malay at 0.60%, Arabic at 3.40%, and Spanish at 0.20%. The bilingual languages in LL primary schools in Kupang are English and Indonesian at 5.61%, Indonesian and Arabic at 1.70%, and English and Indonesian at 10.34%.

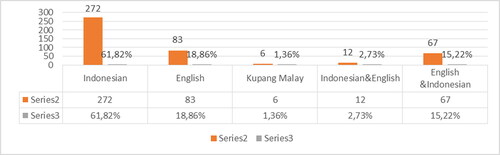

Indonesians dominate the LL in primary schools in Kupang, namely 52.70%, in both public and private primary schools. Nevertheless, the proportion of Indonesian monolinguals is more significant in public primary schools, standing at 61.82%, in contrast to private primary schools, where it is 45.52%. Due to the strength of Indonesian as a national language, many public signs must use that official language in educational environments. This result finding some of the same pattern as those found Riani et al. (Citation2021), which found that Indonesian is a more comprehensible language for message delivery. Andriyanti (Citation2016) similarly mentioned that it is logical to use Indonesian in schools since it is the official language for education and academic writing instruction.

The chart above’s analysis reveals that Indonesian appears as a monolingual language at a rate of 61.82% in public primary schools in Kupang. Moreover, Indonesians are also featured bilingually, with a prevalence of 15.22%. This bilingual presentation includes a distinct pattern where Indonesian is positioned above English following a top-bottom alignment, while another representation shows English preceding Indonesian with a percentage of 2.73%.

English is additionally represented monolingually at 18.86%. The singular local ENT language within the linguistic panorama of public primary schools in Kupang is Kupang Malay at 1.36%. Local languages are few found in schools in the eastern region, which mirrors the lack of indigenous languages in other areas of Indonesia, like Yogyakarta (Andriyanti, Citation2021) and Surabaya (Auliasari, Citation2019). A fascinating angle of this finding compared to the results of a previous study by Andriyanti in 2019, which showed a lack of Arabic signage in Kupang’s public primary schools. Conversely, Andriyanti (Citation2019) study indicated that Arabic accounted for 13.5% of the data, including public primary schools.

Indonesia has a strong presence in language usage at private primary schools in Kupang, accounting for 45.52% of dominance and being the monolingual used. English accounted for 22.58%, Arabic accounted for 6.10%, and Spanish represented 0.36% as monolingual. There are not any local languages displayed in LL of Private primary schools. Moreover, English and Indonesian are used in bilingual form at a rate of 14.52%, with English being the language displayed on top and Indonesian on the bottom. Indonesian and English are also used bilingually, with Indonesian at the top and English at the bottom, with a 7.89% usage rate.

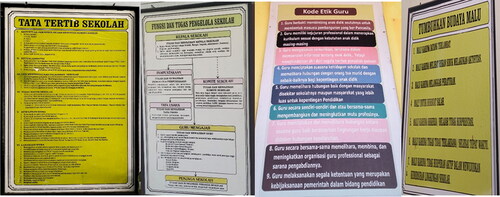

Indonesian is commonly used on public school signs to symbolize the school’s identity, including school name boards, academic calendar boards, scout movement name boards, school work program boards, school vision and mission boards, and student and teacher discipline boards. shows that all sample schools use only the Indonesian language for these signs.

is a group of public signs that provide information about school rules ‘Tata Tertib Sekolah’, the functions and duties of school administrators ‘Fungsi dan Tugas Pengelolah Sekolah’, the teacher code of ethics ‘Kode Etik Guru’, and school programs to foster a disciplined school culture ‘Tumbuhkan Budaya Malu’. The figure shows a monolingual language situation with the use of Indonesian. shows that long texts containing normative regulations and requiring detailed and complete explanations tend to use Indonesian monolingually.

is a group of public signs that provide information about school rules ‘Tata Tertib Sekolah’, the functions and duties of school administrators ‘Fungsi dan Tugas Pengelolah Sekolah’, the teacher code of ethics ‘Kode Etik Guru’, and school programs to foster a disciplined school culture ‘Tumbuhkan Budaya Malu’. The figure shows a monolingual language situation with the use of Indonesian. shows that long texts containing normative regulations and requiring detailed and complete explanations tend to use Indonesian monolingually.

The use of Indonesian also dominates several warning and prohibition signs at LL of primary schools in Kupang. As shown in , these public signs use Indonesian monolingually.

Specific warning and prohibition signs are employed in Indonesia. The signs specify the regulations and responsibilities that all school members, particularly students, must adhere. At the same time, the warning signs are created by writing on the school fence, providing a more adaptable approach. According to the corpus, specific graffiti warnings and prohibition signs utilize English and Indonesian languages, as shown in : ‘Keep your School Clean – Jagalah Kebersihan Sekolah Anda!.’

is the group of samples of room nameplates that provide information on the names of the rooms. The picture shows a bilingual situation with two language codes, Indonesian and English. The use of these languages represents that the school views the importance of Indonesian and English in the school environment. On the other hand, show the use of the English language monolingually. Several public signs in English contain appeals, namely ‘respect your teacher, love your friend; that is a sign that you are an estimated student’. Several other signs prohibit smoking and using illegal drugs. Public signs that function to shape students’ characters into individuals who are non-violent and care about fellow friends also appear in monolingual English in the text that reads, ‘Being a Buddy is better than being a bully.’

Moreover English is commonly utilized in student work showcased on bulletin boards in the school corridors as shown in . Many students use English for two reasons: to recognize students’ excellent work and to serve as a learning tool for language-related topics. English is learned via these specific literary pieces. According to the the schools principals, those schools conduct daily literacy sessions lasting around 15 minutes. During these sessions, students are encouraged to read books or any written material in the school environment, such as wall magazines.

Beside English, Arabic is another foreign languages found in LL in private school in Kupang (). Arabic is taught in private primary schools in Kupang that connect with Islamic religious groups. Hence, it is unsurprising that the school’s linguistic setting consists of public signs written in Arabic. Arabic is integrated into the school curriculum, resulting in numerous public signs being in Arabic to help students learn and enhance their faith and religion.

Spanish is another foreign language found in primary schools in Kupang city. The use of Spanish more as a representation of the school’s founding congregation’s country of origin. It is not practical for learning languages or building students’ beliefs. The last function we identify here is for decoration, as shown in . One of the texts reads ‘En medio de nuestro jardin esta Maria, levantemos con frecuancia a Ella nuestra vista, que Ella nos dara virtud, Ella nos dara poder.’ These Spanish sentences are used as decoration in schools. The students do not understand the meaning of these texts, but they know that the language displayed on the public signs is foreign. Spanish is not included in the school curriculum, and the private school does not use it to introduce the language to students; it is used as a symbol of the school’s Spanish founding foundation ().

The only ENT local language found in elementary school public spaces in Kupang is KML; from all KML data, it is found in only one state school and only two public space signs or 0.60% use this language. According to the school’s principal, which has public space signs in the KML, the KML is used in both signs so that children can better understand the meaning conveyed by the text. The two public signs present in BMK function as conveying information to students about the language of drugs () ‘ Beta, LU, Katong Semua Tolak Narkoba’ and also inform students not to carry out bullying acts ‘jang ba’pukul, jang ba’olok, jang ba’maki, stop ba’ganggu kawan dong!’

Discussion

The above findings depict the languages visibility in Kupang’s primary schools’ public spaces. According to the results, it appears that certain language practices in public primary schools align with national education language policies, but others do not adhere to these policies. Below are a few key points regarding the visibility of language in schools’ public spaces and the implementation of education language policies.

Alignment of the visibility of Indonesian languages with the education language policy

As stated in government regulation number 24 of 2009, the policy of using Indonesian in schools as public spaces has proven to be successfully implemented by primary schools in Kupang, which prioritizes the use of Indonesian on public signs in the school environments. The percentage of monolingual use of Indonesian in both state primary schools and private primary schools is relatively high. The display of Indonesian on public signs in primary schools in Kupang has more of an information function (see Landry & Bourhis, Citation1997). The information function is a sign that Indonesian is the instructional language and the official language in educational areas in Indonesia.

In this way, these primary schools have fulfilled the demands of one of the points in the components of Instrumen Akreditasi Satuan Pendidikan (IASP) Sekolah Dasar/Madrasah Ibtidaiyah, (Citation2020), point 18, which reads thus, "the learning process utilizes the facilities and infrastructure available within and outside the school/madrasah, both available and created by teachers/students as learning media and resources (including language learning resources) which have an impact on improving the quality of learning and student learning outcomes." Thus, Indonesian on public signs is intended for learning purpose.

Apart from that, the dominance of Indonesian in the linguistic landscape of primary schools in the city of Kupang is not only because the school has implemented law number 24 of 2009, but also because the choice of Indonesian monolingual signs relates to language subjects learned at primary schools in Kupang. In the primary education curriculum, Indonesian is a mandatory subject taught at the initial grade levels (grades 1, 2 and 3) to advanced grades (grades 4, 5 and 6). Thus, using Indonesian on primary school public signs is also intended to introduce and teach Indonesian to students to increase their language competence.

Moreover, signs in Indonesian with simple expressions and only a straightforward clause or one phrase (see ) make it easier for grade 1 to grade 3 students who are just learning to read a text. Thus, the Indonesian language in the primary school landscape in Kupang plays a communication rather than a symbolic function. This statement was also stated by Andriyanti (Citation2021) in a study of LL in senior high schools in Yogyakarta, stating that the monolingual use of Indonesian in the school landscape is more for communication than the symbolic function.

Alignment of foreign language visibility with education language policy

English is the most common foreign language displayed monolingually in public areas (see ). The decision to incorporate these languages into the linguistic environment of primary schools serves particular purposes. All primary schools in Kupang have implemented the independent learning curriculum. Based on the observation of the curriculums applied in all researched and interviewed schools, English is a part of the local content subjects taught in public and private schools. Consequently, numerous public signs use English to immerse students in the language and enhance their English vocabulary abilities. Most texts featuring English include room nameplates, warning and prohibition signs, and building character signs. English is commonly utilized in student work, as showcased on bulletin boards in the school corridors, as shown in . These findings support LL researchers’ claim that LL serves not only as a form of communication but also as a valuable tool for language learning, literacy improvement, and enhancing language awareness and sensitivity, Cenoz and Gorter (Citation2008); Sayer (Citation2010); Lotherington (Citation2013); Hewitt-Bradshaw (Citation2014).

The use of English in the primary school environment follows language policy because it has been regulated in several policies from 2006 to 2024, such as, National Education Ministerial Decree Number 22 of 2006 and Culture Regulation No. 12 of (Citation2024) concerning Curriculum at the Child Early Education, Basic Education and Secondary Education Levels. English is one local content that has been mandatory for all primary school students from class I to class VI since 2006 in some schools in Kupang. The school determines the local content substance. However, since the national curriculum revision 2013, English has yet to be mentioned in the 2013 curriculum. However, several primary schools in Kupang that have implemented the 2013 curriculum still include English subjects in their learning content until now.

Apart from that, using English in public school spaces has an informational function that informs that the language is included in the school’s curriculum and spoken by the students and the teacher. Andriyanti (Citation2019) stated that English is used for communication rather than symbolization in schools.

In addition to English, Arabic is taught in private primary schools in Kupang that connect with Islamic religious groups. Hence, it is unsurprising that the school’s linguistic setting consists of public signs written in Arabic. Arabic is integrated into the school curriculum, resulting in numerous public signs being in Arabic to help students learn and enhance their faith and religion. According to Andriyanti (Citation2019), although Arabic is not frequently used in daily discussions, numerous topics in Islamic schools are associated with the Arabic language. Public schools and other private schools do not have monolingual and bilingual Arabic public signs. The presence of mostly Christians and Catholics in Kupang City also affects why Arabic is only taught in Islamic schools. The results contrast Andriyanti’s (Citation2019) study, which revealed that Arabic is also utilized in public areas of state schools in Yogyakarta. The prevalence of Muslims in Yogyakarta’s social landscape justifies the presence of Arabic in state schools despite the absence of Arabic language courses in their curriculum. The language scenery of a location can mirror the societal circumstances through this method. According to Chandler (2007, p. 15), language is a communication tool that shapes social reality.

Spanish is another foreign language found in primary schools in Kupang city. While English and Arabic focus on language acquisition and enhancing students’ faith, Spanish serves a symbolic purpose. The use of Spanish on the public space sign acts more as a representation of the school’s founding congregation’s country of origin. It is not practical for learning languages or building students’ beliefs. Spanish is not included in the school curriculum, and the private school does not use it to introduce the language to students; it is used as a symbol of the school’s Spanish founding foundation.

Mismatch between visibility of local language and education language policy

The only local ENT language in the linguistic landscape of primary schools in Kupang is KML. Primary schools in Kupang do not include local language teaching in the school curriculum. Based on the results of interviews, the school does not feel an urgent need to teach local languages to students, so the use of local languages on public signs in the school environment is not considered a priority. These findings explain that local ENT languages are marginalized in the educational environment, especially primary education.

The school prohibits using Kupang Malay because this language is often considered impolite when used in formal situations within educational institutions. This finding is in line with the opinion of Jacob and Grimes (Citation2011) that some people view Kupang Malay as a dialect. It is typically seen as reinforcing the minority status of the Kupang language in the academic setting of Kupang city, such as the Dawan and Rote languages, with a significant presence in urban areas (see Benu et al., 2023), as illustrated in the linguistic environment of primary schools in Kupang.

The limited presence of local languages on signs in primary schools in Kupang does not adhere to the language policy specified in Law no. 20 of 2003 regarding the National Education System. This law allows for the use of the mother tongue as the language of instruction in early primary school grades, stating that regional languages can be used if needed to impart specific knowledge and skills.

Primary schools in Kupang do not include regional languages in their curriculum or as the language used on public signs, despite the regulations in Law No. 20 of (Citation2003) that advocate for using the mother tongue in early primary education. In the early years of education, if needed, regional languages may be utilized as the medium of instruction to impart specific knowledge and abilities, as stated in Article 33, paragraph 2. As an extension of the National Education System Law stated previously, the Minister has released Minister of Education and Culture Regulation No. 37/ (Citation2018) as a revision to Minister of Education and Culture Regulation No. 24/ Citation2016 regarding Core Competencies and Basic Competencies in the 2013 Curriculum for Primary & Secondary Education. This Policy Copy specifically permits the development of fundamental Indonesian language skills in addition to regional and Indonesian languages in Class I SD/MI.The rules concerned are truly inclusive and benefit early-grade students who have only spoken regional languages before starting school and have not yet mastered Indonesian.

The efforts to revive the local language by the Ministry of Education and Culture in 2022 have not been put into practice in primary schools in the city. Nevertheless, the responsibility does not solely fall on the school as the local government sets the curriculum based on specific laws and regulations. It is possible to criticize the East Nusa Tenggara provincial government for requiring a policy on local languages, as schools can now incorporate local resources into the learning curriculum based on a recent independent study. Incorporating local languages alongside Indonesian in Indonesia’s national education is regulated by Law Number 20 of Citation2003.

The query revolves around determining the most suitable regional language learning approach for schools with diverse language backgrounds. This study suggests a contextual local language learning model for elementary schools in Kupang City. The local content subjects in elementary schools should use the local language spoken by the majority of residents in that community. For instance, in the Nunbaun Sabu sub-district, Kupang City, where most residents are from the Sabu tribe, the Sabu language should be prioritized for the school curriculum. Therefore, the existence of the Sabu language can reflect the surrounding school community, in line with the Indonesian Minister of Education and Culture Regulation Number 79 of (Citation2014) discusses the inclusion of local content in the 2013 Curriculum, emphasizing the importance of incorporating study materials and subjects that highlight the distinct features and potential of the local area to cultivate students’ appreciation for their community’s advantages and wisdom.

This research still has limitations. Even though this research is research that combines quantitative and qualitative methods, the informants interviewed were only limited to school principals; interviews with students, teachers, parents, and the local community were not carried out, and only observations were made, so they did not capture the complete picture of the relationship between public sign language and the mother tongue used by students. Thus, this research cannot reveal just the languages used by primary school students in the city of Kupang; more qualitative data can provide a complete understanding of the actual conditions of the community around the school, which can be used as material for reflection to implement local language teaching, in local content subjects at primary schools in Kupang.

Conclusion

Utilizing the local language on external signs at elementary schools in Kupang, East Nusa Tenggara, serves to preserve the language and enhance literacy among students. Teachers in elementary schools can utilize all public space signs to help students learn letters, reading, and writing in the early stages. The use of their native language in an elementary school’s public areas can indicate the presence of their community in the school setting. The Indonesian government has implemented different language policies in the education field to incorporate local languages in schools. Nevertheless, the federal government allows regional governments and all education stakeholders in the regions more autonomy to integrate the learning of regional languages into local content subjects. The regional government and local community where the school is situated have the final say in local content learning, as they are the ones who know and understand the local potential.

Hence, school administration, educators, school boards, founding organizations, local authorities, and all stakeholders can convene to deliberate on incorporating any indigenous languages as a single local content subject in Kupang’s primary education institutions. The government and the community both share responsibility for owning the language. Ultimately, both formal and informal support from all stakeholders is crucial to preserving language as a cultural identity and a valuable aspect of the diverse Kupang City community, beginning with the foundation of education.

Acknowledgement

The authors would greatly appreciate the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education Agency or Lembaga Penyulur Dana Pendidikan (LPDP) providing financial support and opportunities for researchers to conduct this research. The researcher also highly appreciates the journals editor and anonymous reviewers in providing the contribution and valuable feedback to enrich this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Agnes Maria Diana Rafael

Agnes Maria Diana Rafael is a linguistic doctoral student in the Linguistic Doctoral Study Program Faculty of Language and Culture, Udayana University. Meanwhile, she is also a lecturer in the English Education Study Program Faculty of Teacher Training and Education at Citra Bangsa University. She is currently conducting her dissertation paper on schoolscape linguistics in Kupang. As a lecture, she teaches linguistic courses such as morphology and syntax and other educational courses, such as second language acquisition, English for specific purposes, extensive reading and language culture and society. Her research interest is in linguistics and education, and she has been an active speaker at national and international seminars.

Ketut Artawa

Ketut Artawa, head the Linguistics Doctoral Study Program Faculty of Language and Culture at Udayana University. He is also a lecturer in that study program and an active lecturer in the English Department, Faculty of Language and Culture, Udayana University. He completed his bachelor’s degree (BA) in English language and literature at Udayana University. Then he continued his master’s study in linguistics field in La Trobe University, and he also continued his PhD study at La Trobe University. He obtained his professorship in linguistics in 2005. Until now, he has been actively doing much research in linguistics, especially concerning developing the study of landscape linguistics in Indonesia. He has been the keynote speaker for several national and international seminars.

Made Sri Satyawati

Made Sri Satyawati is a lecturer at the Linguistics Doctoral Study Program, Faculty of Language and Culture, Udayana University; she is also a lecturer at the Indonesian Department, Faculty of Humanities, Udayana University. She is interested in conducting research in the area of linguistics field, such as typology, syntax, typology, semantics, and Eco linguistic. She has published many research articles in micro and macro linguistics, such as some studies of local languages in Eastern Indonesia. She is the academic supervisor for many research theses and dissertations and participates actively as the invited speaker and keynote speaker in various national and international seminars.

Ketut Widya Purnawati

Ketut Widya Purnawati is a Lecturer at Udayana University since 2001. She graduated from the Department of Japanese Literature at Padjadjaran University in 2000. She was continuing his Masters and Doctorate Degrees in the Udayana University Linguistics Program, graduated from the Master’s Program in 2009 and graduated from Doctoral Program in 2018. In 2005–2006 attended the Long-term Training for Japanese Language Teachers at the Japan Foundation, Saitama, Japan. In 2015 received a Research grant from the Hyogo Overseas Research Network to conduct joint research at Kobe Women’s University. Her research interest is linguistics, and she has researched syntax, typology, semantics, and landscape linguistics. She has supervised many bachelor papers, theses and doctorate dissertations. She has also participated as a guest and invited speaker in several national and international seminars.

References

- Andriyanti, E. (2016). Multilingualism of high school students in Yogyakarta, Indonesia: The language shift and maintenance [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Macquarie University.

- Andriyanti, E. (2019). Linguistic landscape at Yogyakarta’s senior high schools in a multilingual context: Patterns and representation. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 9(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v9i1.13841

- Andriyanti, E. (2021). Social meanings in school linguistic landscape: A geosemiotic approach, KEMANUSIAAN, 28(2), 105–134.

- Arikunto, S. (2010). Prosedur Penelitian Suatu Pendekatan Praktik. Rineka Cipta.

- Aronin, L & Laoire M. Ó. (2012). The material culture of multilingualism: Moving beyond the linguistic landscape. International Journal of Multilingualism, 10(3), 225–235.

- Auliasari, W. (2019). A linguistic landscape study of state school and private school in Surabaya [Unpublished Thesis]. UIN Sunan Ampel.

- Backhaus, P. (2006). Multilingualism in Tokyo: A look into the linguistic landscape. In D. Gorter (Ed.), Linguistic landscape: A new approach to multilingualism (pp. 52–61). Multilingual Matters.

- Barni, M., & Bagna, C. (2010). Linguistic landscape and language Vitality. Multilingual Matters.

- Benu, N. N., Artawa, I. K., Satyawati, M. S., & Purnawati, K. W. (2023). Local language vitality in Kupang city, Indonesia: A linguistic landscape approach. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 10(1), 2153973. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2022.2153973

- Brown, K. D. (2012). The linguistic landscape of educational spaces: Language revitalization and schools in Southeastern Estonia. In D. Gorter, L. V. Mensel and H. F. Marten (Eds.), Minority languages in the linguistic landscape (pp. 281–298). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230360235_16

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2008). Linguistic Landscape as an additional source of input in second language acquisition. IRAL, 46, 257–276. https://doi.org/10.1515/IRAL.2008.012

- David, M. K., & Manan, S. A. (2015). Language ideology and the linguistic landscape: A study in Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia. Linguistics and the Human Sciences, 11(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1558/lhs.v11i1.20228

- Duarte, J., Veenstra, S., & van Dijk, N. (2023). Mediation of language attitudes through linguistic landscapes in minority language education. In S. Melo-Pfeifer (Ed.), Linguistic landscapes in language and teacher education: Multilingual teaching and learning inside and beyond the class (Vol. 43. pp. 165–185). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22867-4_9

- Gorter, D. (2006a). Introduction: The study of the linguistic landscape as a new approach to multilingualism. In D. Gorter (Ed.), Linguistic landscape: A new approach to multilingualism. Multilingual Matters.

- Gorter, D. (2006b). Further possibilities for linguistic landscape research. In D. Gorter (Ed.), Linguistic landscape: A new approach to multilingualism. Multilingual Matters.

- Gorter, D. (2013). Linguistic landscapes in a multilingual world. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 13, 190–212. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190513000020 .

- Hewitt-Bradshaw, I. (2014). Linguistic landscape as a language learning and literacy resource in Carribean Creole contexts. Carribean Curriculum, 22, 157–173.

- INSTRUMEN AKREDITASI SATUAN PENDIDIKAN. 2020. SEKOLAH DASAR/MADRASAH IBTIDAIYAH. Badan Akreditasi Nasional Sekolah/Madrasah. 03_IASP2020_SMA-MTs__KEPMENDIKBUD__Sosialisasi_2020_12_21__FA3(2).pdf

- Indonesian Minister of Education and Culture Regulation. 2014 about the inclusion of local content of 2013 curriculum.

- Jacob, J. A., & Grimes, C. E. (2011). Aspect and directionality in Kupang Malay serial verb constructions: Calquing on the grammars of substrate languages. Creoles, Their Substrates, and Language Typology, 95, 337–366.

- Jansen, J., Underriner, J., & Jacob, R. (2013). Revitalizing languages through place-based language curriculum identity through learning: Responses to language endengerment: Studies in language companios seroies 143. John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam/Philadelphi.

- Lai, M. L. (2012). The linguistic landscape of Hong Kong after the change of sovereignty. International Journal of Multilingualism, 10(3), 251–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2012.708036

- Landry, R., & Bourhis, R. Y. (1997). Linguistic landscape and ethnolinguistic vitality: An empirical study. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 16(1), 23–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X970161002

- Law (UU) Number 20 of 2003 concerning the National Education System.

- Lotherington, H. (2013). Creating third spaces in the linguistically heterogeneous classroom for the advancement of plurilingualism. TESOL Quarterly, 47(3), 619–625. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.117

- Minister of Education and Culture Regulation No. 24/2016 regarding Core Competencies and Basic Competencies in the 2013 Curriculum for Primary & Secondary Education.

- Minister of Education and Culture Regulation. 2018. about regarding national languages and literary policies.

- Regulation of the Minister of Education, Culture, Research and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia. 2024. Concerning the Curriculum in Early Childhood Education, Basic Education Levels and Secondary Education Levels.

- Regulation of The President of the republic of Indonesia Number 2 Of 2015. about Development Plan National Medium Term 2015-2019.

- Rafael, A. M. D. (2019). Interferensi Fonologi Penutur Bahasa Melayu Kupang ke Dalam Bahasa Indonesia di Kota Kupang. Jurnal Penelitian Humaniora, 20(1), 47–58. https://doi.org/10.23917/humaniora.v20i1.7225

- Republic of Indonesia Law number 24, 2009 concerning the national flag and national emblem and the national anthem.

- Riani, M. W., Ningsih, A. W., & Novitasari, Z. M. (2021). A linguistic landscapes study in Indonesian sub-urban high school signages: an exploration of patterns and associations. Journal of Applied Studies in Language, 5(1), 134–146.

- Rohman, Z., & Wijayanti, E. W. N. (2023). Linguistic landscape of Mojosari: Language policy, language vitality and commodification of language. Cogent Art and Humanities, 10(2), 2275359.

- Sayer, P. (2010). Using the linguistic landscape as a pedagogical resource. ELT Journal, 64(2), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccp051

- Shohamy, E. G. (2006). Language policy: Hidden agendas and new approaches. Routledge.

- Shohamy, E. G., & Gorter, D. (2009). Linguistic landscape expanding the scenery. Routledge.

- Sugiyono, P. (2017). Metode Penelitian Kuantitatif, Kualitatif, dan R&D. Alfabeta, CV.

- Thai, K. (2019). The implementation of Malay language education policy and the linguistic landscape in Malaysia. International Journal of Humanities, Philosophy, and Language, 2(8), 266–277.

- UNESCO. (2003). Language vitality and endangerment. Paper presented at the International Expert Meeting on UNESCO Programme Safeguarding of Endangered Languages, Paris. www.unesco.org/culture/ich/doc/src/00120-EN.pdf

- UNESCO. (2020). Inclusion and education all means all. UNESCO. unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373718

- (USAID)/Indonesia. 2014. The National Early Grade Reading Assessment (EGRA) and Snapshot of School Management Effectiveness (SSME) Survey Report of Findings. Jakarta.RTI International.

- Yavari, S. (2012). Linguistic landscape and language policies: A comparative study of Linköping University and ETH Zürich [Master’s Thesis]. Linköping University Department of Culture and Communication Master’s Programme in Language and Culture in Europe.

- Yendra, Y., & Ketut, A. (2020). Lanskap Linguistik: Pengenalan, Pemaparan, dan Aplikasi. Deeppublish.