Abstract

Objective: To select patients eligible for outpatient therapy for acute colonic diverticulitis (ACD), we had proposed a new ultrasonography (US)-based classification of ACD. In this study, we validated this US grading system by comparing diagnostic results with those of computed tomography (CT).

Methods: We performed a two-part study. In Study 1, we retrospectively analyzed data collected from 116 ACD patients in Japan, who had undergone both US and CT examinations. The severity of inflammation was two grades (I,II) scored as classification of ACD on the basis of US.

Study 2: According to US-based classification, we retrospectively evaluated whether 170 patients with grade I were successfully treatable in outpatient hospital setting.

Results: 107/107 (100%) US grade I were also CT grade I, and 5/9 (55.6%) US grade II were also CT grade II. The concordance (kappa) value between US and CT grades was 0.698 (SEM = 0.142). Among grade II cases, the findings by US of inflamed diverticulua, pericolitis and abscess > 2 cm in diameter were same as CT. However, CT did not detect an abscess ≤ 2 cm in diameter as detected by US. The retrospective study revealed that 97 (95.1%) of 102 right-sided ACD and 65 (95.6%) of 68 left-sided ACD cases that were diagnosed as grade I were treatable as outpatients.

Conclusions: US can select patients eligible for outpatient therapy, and ACD patients with grade I are allowed to be treated as outpatients.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

How to select patients eligible for outpatient therapy for acute colonic diverticulitis (ACD)? We had proposed a new ultrasonography (US)-based classification of ACD. Also, there is no other US grading system of ACD. We validated this US grading system by computed tomography (CT).

1. Introduction

The increasing incidence of colonic diverticular disease in Japan has been attributed to the adoption of a Western diet, low in fiber and high in fats and sugar. (Miura, Kodaira, Aoki, & Hosoda, Citation1996; Stollman & Raskin, Citation1999) Complications of diverticular disease, including acute colonic diverticulitis (ACD) and diverticulosis with hematochezia, have also been increasing. (Etzioni, Cannom, Ault, Beart, & Kaiser, Citation2009; Etzioni, Mack, Beart, & Kaiser, Citation2009, pp. 210-7) While most patients with ACD in Japan have mild-to-moderate disease, a few cases require surgical intervention (Stollman & Raskin, Citation1999). As such, the determination of cases that can be treated on an outpatient basis and those which require surgery is considered vital.

Computed tomography (CT) imaging has become by now the gold standard in the diagnosis and staging of patients with ACD. We proposed the new ultrasonography (US) classification of ACD (grade I,II) to select mild to moderate ACD patients for outpatients treatment; grade I: An inflamed diverticulum, pericolitis and an abscess ≤ 2 cm in diameter; grade II: An abscess > 2 cm in diameter and pneumoperitoneum (Mizuki et al., Citation2005).

We performed two studies. Study 1 retrospectively validated US findings with those on CT. Study 2 retrospectively examined the accuracy of a US grade I diagnosis in predicting the ability of the disease to be treated on an outpatient basis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study 1

2.1.1. Patients

We reviewed the US and CT reports of 116 patients whose diagnosis was confirmed by medical records, medical summary, discharge summary and/or operative notes between January 2010 and December 2015 at Saiseikai Central Hospital, Tokyo. Given that ACD was suspected based on lower abdominal pain, abdominal tenderness on physical examination and leukocytosis on laboratory testing.

For all patients suspected of having ACD, US examination was performed by expert technicians and a diagnosis was agreed upon by three radiologists. We collected data on cases where CT examination was performed no more than 24 h after US examination, excluding cases with an interval ≥ 24 h. Three abdominal radiologists with over 20 years’ experience (S.K. et al.) independently assessed US (SSA-660A Xraio, APLIO 500 TUS-A500 or AplioXG SSA-700A; Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan) and CT findings (Light Speed VCT or Light Speed VCT VISION; GE, Connecticut, USA) simultaneously. Disagreements among three reviewers were resolved by consensus upon consultation with the senior radiologist (S.K.).

2.1.2. Ultrasonography (US) grading system (Mizuki Et al., Citation2005) and CT criteria

To establish our US grading system (Etzioni et al., Citation2009, pp. 210–7; Mizuki et al., Citation2005), the most significant issue was how to define whether or not a patient should be admitted or should undergo outpatient treatment. To develop the US grading system, we reviewed all of the consecutive patients with a final diagnosis of acute colonic diverticulitis were enrolled in this study, US and CT reports, and their clinical course and outcome based on medical summary, discharge summary and/or operative notes. These data suggested that ACD patients with small abscess detected by US could possibly be treated in the outpatient clinic. On the basis of these data (data not to be shown) and the US features of ACD in the literatures (Townsend, Jeffrey, & Fc, Citation1989; Wada, Kikuchi, & Doy, Citation1990; Wilson & Toi, Citation1990), we developed a tentative US grading system (grade I and II): grade I indicated an inflamed diverticulum with/without pericolitis with/without an abscess ≤ 3 cm in diameter; grade II indicated an inflamed diverticulum with an abscess > 3 cm in diameter, or with perforation of the diverticulum.

To verify the tentative US grading system, we performed a pilot study in outpatient clinic in Saisaikai Central Hospital, Tokyo. Although outpatient treatment of five consecutive cases presenting with abscess ≤ 2 cm in diameter outpatient treatment was successful, treatment of consecutive three cases involving an abscess > 2 cm in diameter was unsuccessful because there was an exacerbation of abdominal pain the following day or on the third day. First patient was a 37-year-old woman with right-sided ACD. Second was a 34-year-old man with right-sided ACD. Third was 34-year-old man with right-sided ACD. It was the first episode for all three patients and no comorbidity was reported in any of the three. A CT scan was performed on second case and the finding was colonic wall thickening with paniculitis but without an abscess. They were treated with intravenous antibiotics on admission: The first patient’s pain subsided without surgical intervention, but conditions of the second and the third patients deteriorated and the abscess grew to 5 cm in diameter. Surgery was performed to the second case and percutaneous drainage guided by US was performed in the third case. We stopped the pilot study at this time, and finally defined that grade I was indicating an inflamed diverticulum with an abscess ≤ 2 cm in diameter and that outpatient treatment was possible.

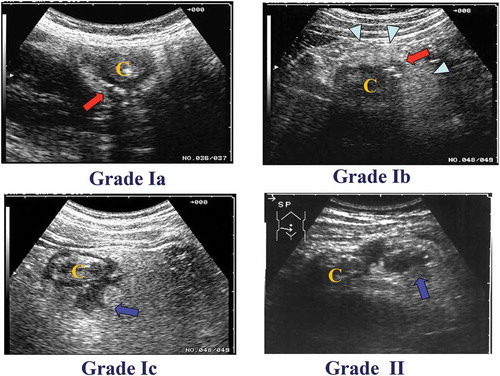

On the basis of our pilot study, we revised the tentative US grading system and we proposed a new US grading system for ACD: grade I includes patients requiring medication in outpatient treatment and grade II included those requiring inpatient hospital care with or without surgical treatment. Different subgrades are then assigned based on the severity of inflammation. An inflamed diverticulum with inflammation limited to the diverticulum itself is graded Ia. An inflamed diverticulum with pericolitis (inflammation clearly extending to the pericolic tissue around the diverticulum) is scored Ib. An inflamed diverticulum with an abscess ≤ 2 cm in diameter is Ic. Grade II indicates an inflamed diverticulum with an abscess > 2 cm in diameter, or with perforation of the diverticulum (Figure ). The CT criteria included localized thickening of the colon wall to ≥ 5 mm and signs of inflammation of pericolic fat, with or without abscess formation, and/or extraluminal air.

Figure 1. Classification of ACD on the basis of US. The severity of ACD was classified into two grades. Grade Ia: an inflamed diverticulum (arrow). “C” indicates colon. Grade Ib: an inflamed diverticulum (arrow) with pericolitis (arrow head). Grade Ic: an inflamed diverticulum with abscess formation of ≤ 2 cm in diameter (arrow). Grade II: an inflamed diverticulum with abscess formation of > 2 cm in diameter (arrow) or with perforation.

2.2. Study 2

2.2.1. Outpatient treatment

A total of 170 patients determined to be treatable as outpatients based on an assigned ACD grade of I by US were treated in accordance with a 10-day treatment protocol (Mizuki et al., Citation2005). The exclusion criteria of this protocol were: bacteremia, any severe comorbidity (such as uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, heart failure, renal failure or end-stage cancer), broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment up to 24 h prior to presentation in the outpatient clinic, inability to understand the protocol and inability to manage self-care. We examined the results of outpatient treatment using medical records.

2.3. 10-day treatment protocol (Mizuki Et al., Citation2005)

The 10-day treatment protocol consisted of an oral antibiotic (cefpodoxime proxetil 200 mg twice daily for 10 days) with at least 1,500 mL/day of a sports drink (405 kcal, 27 kcal/100 mL) for the first 3 days. A free intake of water was allowed during the first 10 days. If the patient showed improvement on day 4, a clear liquid diet was allowed. If improvement was still evident on day 7, a regular diet was resumed (patients were also advised to increase their fibre intake). Where there was no improvement, the patient was hospitalized and given intravenous antibiotics. The evaluation on day 4 and day 7 included a physical examination and blood tests, particularly a white blood cell (WBC) count and a C-reactive protein (CRP) level. A repeat US was performed on day 4. The decision on whether to continue the protocol on day 4 and day 7 was made on the basis of the patient’s symptoms and a physical examination. After clinical signs of local inflammation had disappeared, a final evaluation was performed. This evaluation included a physical examination and a barium enema or a colonoscopy to confirm the presence of diverticula and rule out colon cancer.

3. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using commercial software (SPSS 19.0; IBM-SPSS Japan, Inc., Tokyo). Student’s t-test was used to determine the significance of differences in parametric values between right and left sides. A chi-squared test was used to assess differences between US and CT grades of ACD severity. The concordance of the results was estimated by a kappa test. P values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

4. Results

4.1. Study 1

The records of 116 patients who were diagnosed with ACD were examined. The mean (± standard deviation) age of subjects was 47.6 (± 14.6) years old and BMI (body mass index) was 22.8 (± 4.3). Sixty-nine of these patients were male and 47 were female, 108 with grade I ACD (Ia 13, Ib 79 and Ic 15) and 9 with grade II (Table ).

Table 1. Patient characteristics

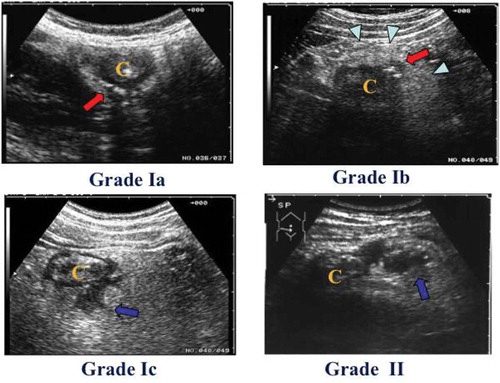

Results of comparisons between US and CT findings are shown in Table . Of the 13 patients designated as grade Ia with US, 8 were diagnosed as Ia, 3 as Ib and 2 as no inflammation by CT. Of the 79 patients designated as grade Ib with US, 3 were diagnosed as grade Ia and 76 as Ib by CT. Of the 15 patients designated as grade Ic with US, 11 was diagnosed as Ib and 4 as Ic by CT. Four pericolic abscesses with a maximum diameter of 2 cm, as revealed by US, were evident on CT. Of the 9 patients designated as grade II with US, 5 were diagnosed as grade II, 2 as Ib (since the size of the abscess could not be determined by CT) and 2 as Ic by CT (Figure ). Overall, 107/107 (100%) US grade I were also CT grade I, and 5/9 (55.6%) US grade II were also CT grade II. The concordance (kappa) value between US and CT grades for grades I and II was 0.698 (SEM = 0.142). There were no significant differences in the concordance by US and CT grades between right-and left-sided ACD (data not shown).

Table 2. Results of grades of acute colon deverticulitis between ultrasound sonography (US) and computer tomography (CT)

Figure 2. Comparison of findings by ultrasonography (US) with those by computed tomography (CT).

(A) In more than 60% of cases, US Grades Ia were diagnosed as Grade Ia. The red arrow indicates the inflamed diverticulum. The arrow indicates the inflamed diverticulum. The arrowhead indicate the inflamed pericolic tissue. The letter “C” indicates colon.(B) In more than 90% of cases, US Grades Ib were diagnosed as Grade Ib. The arrow indicates the inflamed diverticulum. The arrowheads indicate the inflamed pericolic tissue. The letter “C” indicates colon.(C) In more than 25% of cases, US Grades Ic were diagnosed as Grade Ic. The arrow indicates the small abscess. The arrowhead indicates the inflamed diverticulum. The letter “C”indicates colon.Da,b) In more than 50% of cases, US Grades II were diagnosed as Grade II. The long arrow indicates a large abscess. The short arrow indicated free air. The arrowhead indicates air leakage. The letter “C” indicates colon.

4.2. Study 2

We followed up the results of outpatient treatment. A total of 170 patients (right/left side symptoms: 102/68) with grade I ACD on US were treated as outpatients (Table ).

Table 3. Patients characteristics of outpatient treatment

Of 170 patients with ACD, 164 (95.3%) were treated successfully as outpatients. No significant differences were noted between the percentages of right- and left-sided ACD assigned to outpatient treatment (Table ).

Table 4. Clinical results in Right and Left side ACD patients

Five grade I ACD patients with right-sided symptoms were unsuccessfully treated as outpatients and needed hospitalization for exacerbation of abdominal symptoms with unchanged US findings and mild elevation of C-reactive protein (CRP) levels. They were treated in the hospital with intravenous antibiotics, and all were improved. Three patients with left-sided grade I ACD were also unsuccessfully treated as outpatients, presenting with the same exacerbation of abdominal symptoms, unchanged US findings and mild elevation of CRP. They were also treated in the hospital with intravenous antibiotics, and then they improved except for one. One left-sided grade I ACD needed percutaneous drainage and surgical resection, but no deaths due to ACD occurred.

5. Discussion

Here, to assess ACD severity and properly assign patients to outpatient or inpatient treatment, we had proposed the new US-based classification of ACD. (Mizuki et al., Citation2005) In this study, we successfully demonstrated the accuracy of our US-based classification.

The clinical course of ACD passes through four steps: Beginning with an inflamed diverticulum, proceeding to pericolitis, then to formation of a small abscess, and then to either or both enlargement of the abscess or peritonitis. US may be useful as an initial diagnostic test to determine the presence of ACD. The main sonographic sign of perforation is free intraperitoneal air, resulting in increased echogenicity of the peritoneal stripe associated with multiple ring-down artifacts with a characteristic comet-tail appearance. The scheme devised by Hinchey et al. (Hinchey, Schaal, & Richards, Citation1978) is a useful way of classifying the stages of inflammation encountered in patients with diverticular disease. Stage I encompasses patients with small confined pericolonic abscesses, Stage II those with larger collections, Stage III those with generalized suppurative peritonitis and Stage IV those with fecal peritonitis. However, the main focus of Hinchey’s classification is to identify patients with perforated diverticula, who need surgical treatment; this system is not useful for assessing treatable patients with mild-to-moderate acute colonic diverticulitis. Using our US grading system may facilitate differentiation between Hinchey’s Stages I and II disease and to detect patients with disease necessitating hospital admission.

CT is considered the gold standard diagnostic procedure for ACD, and this modality has additional potential in the detection of abscesses. (Destigter & Keating, Citation2009; Labs, Sarr, Fishman, Siegelman, & Cameron, Citation1988; McKee, Deignan, & Krukowski, Citation1993; Neff & Van Sonnenberg, Citation1989; Padidar, Jeffrey, Mindelzun, & Dolph, Citation1994; Saini et al., Citation1986; Siewert & Raptopoulos, Citation1994) Previous studies using US suggested that this modality has a sensitivity of 84%–98% and a specificity of 80%–99%. There is a positive predictive value of 76%–96% for US and 81% for CT; a negative predictive value of 84%–96% for US and 81% for CT; and an accuracy of abscess detection of 90%–97% for US. (Chou et al., Citation2001; Eggesbo, Jacobsen, Kolmannskog, Bay, & Nygaard, Citation1998; McKee et al., Citation1993; Pradel et al., Citation1997; Schwerk, Schwarz, & Rothmund, Citation1992; Verbanck et al., Citation1989) These data indicate that US is useful to detect earlier ACD.

In our previous study, US showed 98.8% sensitivity in detecting ACD (unpublished data). Six patients (1.2%) of 499 with ACD were negative on US, and additional imaging with CT scanning was performed due to either or both severe obesity or excess colonic gas. In the present study (Study 1), the concordance (kappa) value between grades of US and CT was 0.698. In addition, CT did not detect an abscess ≤ 2 cm in diameter on US. These data suggest that US is, at least, also useful as CT in determining whether or not a patient requires hospital admission.

In Study 2, we retrospectively evaluated the validity of our US classification in predicting whether or not patients could be treated as outpatients. A total of 170 grade I patients determined by US were treated as outpatients. More than 95% of ACD patients with grade I scores were treatable as outpatients.

Taken together, the results of Study 1 (validation with CT) and Study 2 (> 95% treatable as outpatients) suggest that US-based classification among patients with mild-to-moderate ACD is useful and available in clinical cite.

Apart from this study, from our experience, five grade II patients (right/left side: 2/3) were treated as outpatients because they refused recommendation of administration to the hospital. Ultimately, five needed to be admitted due to exacerbation of abdominal pain after a few days. Three (one perforation, one moderate abscess, one penetration into the bladder) were treated with intravenous antibiotics on admission and then improved. The other two (one large abscess, one peritonitis) required surgical treatment. From these results, we concluded the cut-off of 2 cm for outpatient management and believe that patients with US grade I ACD can undergo outpatient treatment, whereas patients with US grade II should be admitted.

Several limitations to the present study warrant mention. First, a large proportion of our population had right-sided ACD, which is distinctly uncommon in Western countries. Patients with higher weight and BMI in Western countries may not be good candidates for US. Second, the diagnostic accuracy of US is operator-dependent. Third, we did not use a CT scanner with multi-slice imaging capabilities or dynamic US, which can both easily detect small abscesses in the range of 2–3 cm in diameter. Fourth, our patients’ fluid collections were not drained or aspirated, so we could not confirm the presence of small abscesses. Further studies using multi-slice CT imaging and dynamic US are therefore required to clarify the actual accuracy of the two modalities in distinguishing between cases requiring medication and those needing surgery.

The cost of US is 1,600 yen ($13: 1$ = 120 yen), while CT with contrast material is 9,500 yen ($79) in Japan. US is inexpensive, noninvasive and has a number of options available (Destigter & Keating, Citation2009; Pradel et al., Citation1997; Verbanck et al., Citation1989). We therefore proposed a new US-based classification of ACD severity and validated this system using CT. Although we were unable to conclude that hypoechoic foci were small abscesses, the diagnosis of ACD by US was also found to be comparable to that by CT.

6. Conclusions

US is available in early, uncomplicated ACD and can be used as the first modality in outpatient wards for patients with suspected ACD symptoms and histories. ACD patients with grade I diagnosed by US are allowed to be treated as outpatients.

Authors listed below DO NOT have any financial or other relationships to disclose:

Akira Mizuki MD, Masayuki Tatemichi MD, Satoshi Kaneda MD, Atsushi Nakazawa MD, Nobuhiro Tsukada MD, Hiroshi Nagata MD

Authorship and contributions

Akira Mizuki contributed to conception and design, acquisition of data and drafting the airticle.

Satoshi Kaneda contributed to acquisition of data and analysis.

Masayuki Tatemichi contributed to analysis and interpretation of data.

Atsushi Nakazawa and Nobuhiro Tsukada contributed to acquisition of data.

Hiroshi Nagata contributed to revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Takanori Kanai contributed to finnal approval of the version to be published.

Ethics

This study protocol was approved by the review board of Saiseikai Central Hospital and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the residents and staff of the Internal Medicine, Surgery and Radiology departments of Saiseikai Central Hospital for their help in the care of patients. In particular, we would like to thank Toru Mori, MD, and Kenichi Kodera, MD, who provided diagnostic ultrasound services and CT scans; and Yutaka Mishima, Mikiko Nozaki, Eriko Honda, Seishi Sasahara and Kyoko Kanemaru, who performed the ultrasound examinations. Finally, we are grateful to Ken Haruma, MD for useful comments.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Akira Mizuki

Akira Mizuki obtained AGA Distinguished Abstract Plenary Session, clinical practice, DDW2003. He obtained a PhD in Experimental Medicine from Toho University in 2004. Akira's research focuses on the etiology, diagnosis, treatment and prevention of acute colonic diverticulitis and colonic diverticular bleeding. Akira will apply the findings of this paper to inform the analysis of validation by CT of the new Ultrasonography classification of acute colonic diverticulitis.

References

- Chou, Y. H., Chiou, H. J., Tiu, C. M., Chen, J. D., Hsu, C. C., Lee, C. H.…. Yu, C (2001). Sonography of acute right side colonic diverticulitis. American Journal of Surgery, 181, 122–127. doi: 10.1080/2331205X.2017.1313505

- Destigter, K. K., & Keating, D. P. (2009). Imaging update: Acute colonic diverticulitis. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery, 22, 147–155. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1236158

- Eggesbo, H. B., Jacobsen, T., Kolmannskog, F., Bay, D., & Nygaard, K. (1998). Diagnosis of acute left-sided colonic diverticulitis by three radiological modalities. Acta Radiologica, 39, 315–321.

- Etzioni, D. A., Cannom, R. R., Ault, G. T., Beart, R. W., Jr, & Kaiser, A. M. (2009). Diverticulitis in California from 1995 to 2006: Increased rates of treatment for younger patients. Annals of Surgery, 75, 981–985.

- Etzioni, D. A., Mack, T. M., Beart, R. W., Jr, & Kaiser, A. M. (2009). Diverticulitis in the United States: 1998–2005: Changing patterns of disease and treatment. The American Surgeon. 249, 210–217. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181952888

- Hinchey, E. J., Schaal, P. G., & Richards, G. K. (1978). Treatment of perforated diverticular disease of the colon. Advances in Surgery, 12, 85–109.

- Labs, J. D., Sarr, M. G., Fishman, E. K., Siegelman, S. S., & Cameron, J. L. (1988). Complications of acute diverticulitis of the colon: Improved early diagnosis with computerized tomography. American Journal of Surgery, 155, 331–336.

- McKee, R. F., Deignan, R. W., & Krukowski, Z. H. (1993). Radiological investigation in acute diverticulitis. The British Journal of Surgery, 80, 560–565.

- Miura, S., Kodaira, S., Aoki, H., & Hosoda, Y. (1996). Bilateral type diverticular disease of the colon. International Journal of Colorectal Disease, 11, 71–75.

- Mizuki, A., Nagata, H., Tatemichi, M., Kaneda, S., Tsukada, N., Ishii, H.… Hibi, T. (2005). The out-patient management of patients with acute mild-to-moderate colonic diverticulitis. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 21, 889–897. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02422.x

- Neff, C. C., & Van Sonnenberg, E. (1989). CT of diverticulitis. Diagnosis and treatment. Radiologic Clinics of North America, 27, 743–752.

- Padidar, A. M., Jeffrey, R. B., Jr., Mindelzun, R. E., & Dolph, J. F. (1994). Differentiating sigmoid diverticulitis from carcinoma on CT scans: Mesenteric inflammation suggests diverticulitis. American Journal Roentgenol, 163, 81–83. doi:10.2214/ajr.163.1.8010253

- Pradel, J. A., Adell, J. F., Taourel, P., Djafari, M., Monnin-Delhom, E., & Bruel, J. M. (1997). Acute colonic diverticulitis: Prospective comparative evaluation with US and CT. Radiology, 205, 503–512. doi:10.1148/radiology.205.2.9356636

- Saini, S., Mueller, P. R., Wittenberg, J., Butch, R. J., Rodkey, G. V., & Welch, C. E. (1986). Percutaneous drainage of diverticular abscess. An Adjunct to Surgical Therapy Archives Surgery, 121, 475–478.

- Schwerk, W. B., Schwarz, S., & Rothmund, M. (1992). Sonography in acute colonic diverticulitis. A Prospective Study Diseases Colon Rectum, 35, 1077–1084. doi:10.1007/BF02252999

- Siewert, B., & Raptopoulos, V. (1994). CT of the acute abdomen: Findings and impact on diagnosis and treatment. American Journal Roentgenol, 163, 1317–1324. doi:10.2214/ajr.163.6.7992721

- Stollman, N. H., & Raskin, J. B. (1999). Diverticular disease of the colon. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 29, 241–252.

- Townsend, R. R., Jeffrey, R. B., Jr, & Fc, L. (1989). Cecal diverticulitis differentiated from appendicitis using graded-compression sonography. American Journal Roentgenol, 152, 1229–1230. doi:10.2214/ajr.152.6.1229

- Verbanck, J., Lambrecht, S., Rutgeerts, L., Ghillebert, G., Buyse, T., Naesens, M.…Tytgat, H (1989). Can sonography diagnose acute colonic diverticulitis in patients with acute intestinal inflammation? A prospective study. Journal of Clinical Ultrasound : JCU, 17, 661–666.

- Wada, M., Kikuchi, Y., & Doy, M. (1990). Uncomplicated acute diverticulitis of the cecum and ascending colon: Sonographic findings in 18 patients. American Journal Roentgenol, 155, 283–287. doi:10.2214/ajr.155.2.2115252

- Wilson, S. R., & Toi, A. (1990). The value of sonography in the diagnosis of acute diverticulitis of the colon. American Journal Roentgenol, 154, 1199–1202. doi:10.2214/ajr.154.6.2110728