Abstract

In the U.S., the prevalence of blindness is expected to double by 2050 and as many half of those with blinding eye disease are unaware of their diagnosis. Screening for vision health in the community setting may offer a key strategy to address the rising trend avoidable vision loss. However, problems with excessive referrals and low compliance with these referrals (often <50%) undermine the effectiveness of vision screening programs. We investigated the outcomes of a modified vision screening program design. Key modifications were 1) incorporating an on-site ophthalmologist during screening events; and 2) leveraging community partner resources to maximizing benefit to participants. A review of screening outcomes of 4349 particpant examinations from the Casey Eye Institute Outreach Program (CEIO program) from 01/04/2012 to 10/31/2016 were analyzed for demographics and disease findings. The burden on participants to comply with referrals was lessened as 97% of participants completed definitive exams. Clinical care was recommended for 924 (21.2%) participants. Nearly four out of five participants (78.8%) were provided care for all of their immediate vision health needs (full exams, refractions, and spectacle ordering). Modifications to vision screening program design may improve their effectiveness.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

In the U.S., the prevalence of blindness is expected to double by 2050 and as many as half of those with blinding eye disease are unaware of their diagnosis. Screening for vision health in the community setting may offer a key strategy to address the rising trend of avoidable vision loss. However, problems with excessive referral rates and low compliance with these referral recommendations undermine the effectiveness of vision screening programs. The Casey Eye Institute Adult Outreach Program vision health screening design attempts to address recognized limitations of traditional screening methods by utilizing an onsite ophthalmologist which may lessen the problems of over referral and non-compliance with referral recommendations.

1. Introduction

In the U.S., the prevalence of blindness and visual impairment is projected to double by 2050 (Prevention, Citation2006; Varma et al., Citation2016). The millions who will confront vision loss in the coming years may experience losses in quality of life, financial decline, and social isolation. Blindness and visual impairment also weigh heavily on society generally with a toll estimated at $139 annually for the U.S. economy (America, Citation2012; Wittenborn et al., Citation2013). In spite of these consequences, it is likely that half or more of those with sight-threatening eye diseases remain undiagnosed and untreated (Shaikh, Yu, & Coleman, Citation2014; Wittenborn, Rein, Citation2016; Wittenborn et al., Citation2013).

Vision health screening in the community setting can identify the major causes of vision loss in the U.S., including glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and macular degeneration (Mansberger, Edmunds, Johnson, Kent, & Cioffi, Citation2007; National Academies of Sciences et al., Citation2016; Quigley, Park, Tracey, & Pollack, Citation2002; Zhao et al., Citation2017). However, vision screening programs frequently report difficulties delivering efficient and cost-effective programs, which undermines support for their broader implementation. In recent years, both the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the National Academy of Science Engineering Medicine (NASEM) noted the insufficient evidence to demonstrate the benefits from vision screening or to guide screening strategies (Force, Citation2014; National Academies of Sciences et al., Citation2016). These limitations will need to be addressed if community-based vision screening is to fulfil its potential as a key strategy to improve vision health in the U.S. (National Academies of Sciences et al., Citation2016; Services, Citation2013).

The traditional design of vision screening programs may have led to significant losses of efficiency and cost-effectiveness (Zhao et al., Citation2017). Important problems reported by many screening programs include excessively high rates of referral for definitive exams and an inability to get participants to definitive exams (Friedman et al., Citation2013; Mansberger et al., Citation2007). Critical support from partner agencies and participants for vision screening can be lost when only modest benefits from screening are provided. As well, short program timelines limit the capacity to evolve and refine screening design to deliver more effective programs.

To attempt to address these limitations, we implemented the Casey Eye Institute Outreach (CEIO) program to evaluate design modifications and their effect on vision screening outcomes. The CEIO utilizes an on-site eye doctor to improve access for definitive exams, maximizes the benefit for participants from screening, and integrates local partner agencies into screening events. In this report, we present the program design and the findings from over four years of vision screening utilizing these design modifications.

2. Methods

The Institutional Review Boards of Oregon Health & Science University (Portland, OR) reviewed and approved the study protocol. All participants provided informed consent for use of their de-identified exam data to be used for research purposes. The study followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

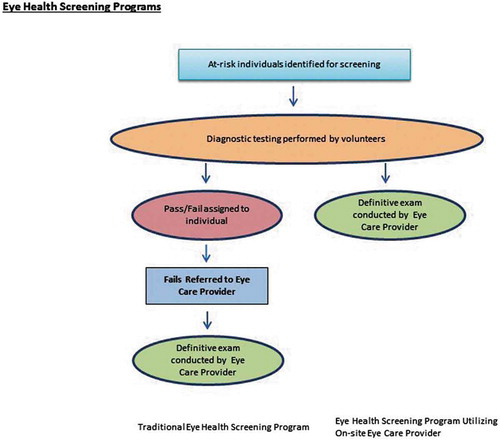

Figure depicts traditional vision screening programs compared to the CEIO program. The CEIO program components include, in order of occurrence, identification of at-risk individuals, diagnostic screening tests performed by volunteers, and on-site definitive eye exams as the final outcome. During the period analyzed here, definitive exams were recommended for all participants. The program is transitioning, at high volume locations, to a process where only participants with abnormal history or screening tests are referred for an on-site definitive exam. Vision health screening steps typically include the identification of at-risk individuals through a brief health history or diagnostic screening tests performed by volunteers, assignment of a pass/fail status for each participant, and referral of those with screening failures status to an eye care provider, and then a definitive eye exam followed by a referral for clinical care if needed. The CEIO program was created in 2010 to provide vision health screening to Oregon’s at risk populations and minimize the loss of efficiency and effectiveness that can occur during the additional steps listed in traditional screenings above.

2.1. CEIO program facilities

The 33 foot mobile clinic contains two fully-equipped ophthalmic lanes and equipment for an additional exam lane that can be transferred into the partner agency facility. Instrumentation includes slit lamp and indirect ophthalmoscopes, phoropters, auto-refractor, lensometer, visual acuity charts, Medtronic tonopens, near spectacle exam and spectacle dispensing station.

2.2. Partner agencies and reach

Over 60 local health and social service partner agencies dedicated to underserved communities throughout all regions of Oregon are integrated into the CEIO program. These partner agencies identify and organize at-risk participants. CEIO provides partner agencies with detailed inclusion criteria for scheduling at-risk participants defined as un- or under- insured persons who have not had access to preventive eye exams and those that describe vision loss or other eye health symptoms, a history of diabetes or eye disease, or family history of eye disease. Partner organizations also provide physical space to conduct the screenings (building, bathrooms, parking), provision of corrective lenses, and management of identified referrals for clinical care. Each year, we review program data to assess our reach demographically and then target community partners accordingly to address gaps in groups at risk.

2.3. Screening process

On each screening day, 40–100 participants register through the partner agency and a brief vision health questionnaires are completed by volunteers. Screening exam components include distance and near acuity, lensometry, auto refraction, manual refraction, and tonometry. Participants are then dilated and transferred to the adjacent mobile clinic where an eye doctor examines the anterior segment and fundus. Exam findings are discussed and the local partner agency manages referrals for clinical care. Reading glasses are dispensed when appropriate. Partner agencies facilitate delivery of eyeglasses (provided by the program) to participants.

2.4. Data analysis

We performed a retrospective review of screening events from 01 April 2012–31 October 2016. We excluded charts with insufficient documentation or illegible charting. We scanned paper charts documenting demographic data and screening findings were transcribed to OnBase® (version 15.0.1.84, Westlake, Ohio) and then exported to calculate frequency and percentages. We calculated proportions to compare the population from our study and the general population of Oregon.

3. Results

3.1. Study population

From 01 April 2012–31 October 2016 the CEIO program screened 4349 participants. The average age of these participants was 47.6 years, and they were predominantly Hispanic (40.9%) and White (34.9%). Table describes detailed demographics of the study population as well as comparisons to the general population of Oregon which as 3,831,074 according to the 2010 census (Bureau, Citation2016). While 78.5% of Oregon’s population is non-Hispanic White (Bureau, Citation2016), this group comprised only 29.9% of visits. Hispanics/Latinos accounted for 36% of exams (and 11.7 % of Oregon’s population). Those referred for follow up care were older (52.9 years mean age) than the participants as a group (47.6 years). We found no statistical difference in race/ethnicity and sex between the total population screened and those referred for follow up care.

Table 1. Demographics from the CEIO program (N = 4349 visits)

3.2. Screening exam findings

Table describes the full distribution of abnormal findings. Over half (2214) of the 4349 participants had refractive error. Prominent sight threatening eye diseases identified in participants included 390 (9%) glaucoma suspects, 385 (8.9%) with dry eye disease, 237 (5.4%) with diabetic retinopathy, and 218 (5.0%) with pterygium. Identification of likely systemic health concerns (e.g. diabetes and hypertension) was also noted for 14 participants.

Table 2. Distribution of abnormal findings in CEIO program (N = 4349)

3.3. Management and referrals for clinical care

A total of 924 screening participants, or 21.2% of total visits, were referred for clinical care. The most common reasons for referral to clinical care were; glaucoma suspect 314 (34% of total referred, 7.2% of total screened), visually-significant cataract 178 (19.3% of total referred, 4.1% of total screened), and diabetic retinopathy 96 (10.4% of total referred 2.2%, of total screened) (Further details are available in Table ). Even though partner agencies strive to find those most at risk, a portion of participants were already receiving clinical care. Therefore, the number of referrals for clinical care was lower than the number identified with disease. The CEIO program dispensed 1779 prescriptions for corrective lenses and 2685 reading glasses.

Table 3. Distribution of abnormal findings leading to referral for clinical care from the CEIO program (N = 4349)

4. Discussion

The program design modifications utilized by the CEIO may help to address important limitations of traditional community-based vision screening. Providing on-site and day of screening definitive examinations resulted in quick and convenient exam conclusions and completion of the screening process. These timely definitive exams minimized the drain on program efficiency from suboptimal testing specificity. The most troublesome obstacle for vision screening, the often poor compliance with referrals from screening sites to definitive exams (<50%), is essentially resolved by this program design (Friedman et al., Citation2013; Quigley et al., Citation2002; Zhao et al., Citation2017). When so many of those identified as at-risk for eye disease do not complete the full screening process, both the measured and generally perceived value of vision screening programs deteriorate. Due to important contributions from local partner agencies this has become a long-term sustainable program across a broad geographic and cultural reach (currently at eight years of service with continued program growth). The long term program design allows the CEIO to refine and improve the program across diverse settings and mold the service to each population groups (e.g. rural vs urban sites, Hispanic migrant laborers, or inner city whites). Partner agencies are uniquely positioned to improve the final health outcomes by integrating with local clinical care resources.

Vision screening programs traditionally utilize volunteers or technicians to administer questionnaires and vision health tests. Participants identified through this process as at-risk are referred for a later and often off-site definitive examinations. (Baker, Bazargan, Bazargan-Hejazi, & Calderon, Citation2005; Friedman et al., Citation2013; Kopplin & Mansberger, Citation2015; Quigley et al., Citation2002). This screening program design poses challenges from weak test performance (e.g. fundus photography with 39% (Zhao et al., Citation2017) of ungradable images) and limited test specificity (Kopplin & Mansberger, Citation2015; Zhao et al., Citation2017). These testing limitations, especially challenging for glaucoma, mean that as many as 39%—69% of participants fail the screening tests (Friedman et al., Citation2013; Mansberger et al., Citation2007; Quigley et al., Citation2002; Zhao et al., Citation2017). With this high a rate of referral, the primary goals of screening—efficiency and cost effectiveness—are quickly lost. What has been reported is that either many participants have eye disease, which may make screening is an inherently inefficient strategy, or fewer participants have disease and many definitive exams are unnecessary, yet consume participant and screening program resources (42–54% of later exams can be normal) (Friedman et al., Citation2013; Kopplin & Mansberger, Citation2015; Quigley et al., Citation2002).

The CEIO and other vision screening programs in the U.S. shared similar outcomes following definitive exams, in spite of the varied initial screening design and setting. Comparable proportions of participants were reported with glaucoma suspect status, diabetic retinopathy, and cataract as well as the requirement for later clinical care (approximately 20% of participants) (Friedman et al., Citation2013; Mansberger et al., Citation2005; Quigley et al., Citation2002; Zhao et al., Citation2017). A broad and detailed spectrum of eye disease (from peripheral retinal detachments to ocular surface neoplasms) were also identified with ophthalmology expertise. Corrective eyeglasses based on manifest refractions were ordered at the event and delivered by partner agencies, building further rapport between the CEIO, partner agencies, and the communities they serve. These additional program features lead to the provision of all needed eye care for nearly 80% of participants.

Screening programs reliant on off-site or later definitive exams have invested generously in efforts to improve low follow up rates for these exams (Friedman et al., Citation2013; Kopplin & Mansberger, Citation2015; Quigley et al., Citation2002; Zhao et al., Citation2017). Only modest and intermittent improvements in follow up have resulted despite offers of education on the potential damage from eye disease, appointment reminders via phone, text, email, and letter, free transportation, and free examinations. This persistent problem may be intrinsic as the populations that undergo screening generally do due to their inability to access health care. By offering definitive exams for all participants, rather than just those who failed screening the CEIO differed significantly from traditional screening programs. This strategy is now gradually being altered to provide exams only for those who failed initial screening tests to increase efficiency. The current program design was able to complete definitive exams for 98% of all participants. We are now investigating the capacity of partner agencies to facilitate access to clinical care.

Investing in on-site eye doctors may require considerable professional resources, yet these definitive exams would otherwise need to be completed in clinical settings. Published reports suggest that off-site or later exams require additional investments (e.g. free clinic exams, transportation, etc.) and are subject to high no-show rates that compromising efficiency in clinical setting where lost revenue can be significant. Whether these costs outweigh investments for on-site eye care provider is a key question that deserves further study. Also, this calculation should attempt to weigh the loss of social capital when investments in screening leave many of those identified as at-risk without a definitive diagnosis or needed medical care.

The over 60 community partner agencies integrated within a long-term and sustainable program design greatly increases program capacity. These partner agencies extend the reach of the program across diverse populations and broad geography. These partners integrate the CEIO with varied populations including rural and urban whites, largely rural Hispanics, urban Blacks, and AI/AN on tribal lands, among other groups. Years of cooperative programs has developed the skills within these agencies to manage screening promotion, scheduling, provision and organization of host facilities, volunteer recruitment and training, provision of spectacles, and referral to clinical eye care. Given the limited resources of the CEIO program, sharing the workload is essential to its long-term sustainability. This partnership model represents best practices in public health and the opportunity to continue to evaluate and improve the design and execution of the program over many years.

4.. Conclusion

Preventable vision loss is increasing in the U.S. and many sight-threatening diseases can be identified by community-based vision screening. Problems with the design of vision screening programs appears to limit their efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and governmental support. Utilizing an on-site eye care provider and integrating local partner agencies minimized the detrimental effects from screening test limitations, lessened the burden of definitive exams, resolved losses to follow up, and maximized the benefits of screening for participants. Future studies could compare the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of screening program designs to draw from the strengths of each and develop better vision screening programs in the future.

Conflicts of interest

None of the authors have any proprietary interests or conflicts of interest related to this submission.

Prior publication

This submission has not been published previously and it is not being considered for any other publication at this time.

Responsibility

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the supporting organization mentioned above or at acknowledgement section. The sponsor or funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research. Each author has contributed to the work of this manuscript.

IRB approval

This research was reviewed by the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board and approved under IRB protocol number 00009884.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the expertise of and data collection performed by, Lucy Malloch, Verian Wedeking, and Christine Flores. We would also like to thank our wonderful volunteers and partner agencies for their contribution to the success of our program.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mitch Brinks

Dr. Mitchell Vaughn Brinks is the Medical Director for Domestic Outreach at the Casey Eye Institute. He received his Master of Public Health from Oregon State University after completing his medical degree at OHSU. Dr. Brinks has dedicated his medical career to improve the quality of eye care to underserved communities throughout the Pacific Northwest. He oversees the Casey Eye Institute Adult Outreach Program that provides vision screening to under and un-insured individuals and is active in creating policy at the national level to address vision health. Current research and advocacy efforts include studying the cause, and the solution, for avoidable blindness in Oregon.

References

- America, P. B. (2012). Vision problems in the U.S. Prevalence of adult vision impairment and age-related eye disease in America. Retrieved from http://www.visionproblemsus.org/index.html

- Baker, R. S., Bazargan, M., Bazargan-Hejazi, S., & Calderon, J. L. (2005). Access to vision care in an urban low-income multiethnic population. Ophthalmic Epidemiology, 12(1), 1–12. doi:10.1080/09286580590921330

- Bureau, U. C. (2016). Oregon quick facts from the US Census Bureau. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/POP060210/41

- Force, U. S. P. S. T. (2014). Final recommendation statement: Impaired visual acuity in older adults: Screening. Retrieved from http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/impaired-visual-acuity-in-older-adults-screening

- Friedman, D. S., Cassard, S. D., Williams, S. K., Baldonado, K., O’Brien, R. W., & Gower, E. W. (2013). Outcomes of a vision screening program for underserved populations in the United States. Ophthalmic Epidemiology, 20(4), 201–211. doi:10.3109/09286586.2013.789533

- Kopplin, L. J., & Mansberger, S. L. (2015). Predictive value of screening tests for visually significant eye disease. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 160(3), 538–546.e533. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2015.05.033

- Mansberger, S. L., Edmunds, B., Johnson, C. A., Kent, K. J., & Cioffi, G. A. (2007). Community visual field screening: Prevalence of follow-up and factors associated with follow-up of participants with abnormal frequency doubling perimetry technology results. Ophthalmic Epidemiology, 14(3), 134–140. doi:10.1080/09286580601174060

- Mansberger, S. L., Romero, F. C., Smith, N. H., Johnson, C. A., Cioffi, G. A., Edmunds, B., … Becker, T. M. (2005). Causes of visual impairment and common eye problems in Northwest American Indians and Alaska Natives. American Journal of Public Health, 95(5), 881–886. doi:10.2105/ajph.2004.054221

- National Academies of Sciences, E., Medicine, H., Medicine, D., Board on Population, H., Public Health, P., & Promote Eye, H. (2016). The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In A. Welp, R. B. Woodbury, M. A. McCoy, & S. M. Teutsch (Eds.), Making eye health a population health imperative: Vision for tomorrow. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US) Copyright 2016 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved, 13–16.

- Prevention, C. F. D. C. A. (2006). Improving the nation’s vision health: A coordinated public health approach. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/visionhealth/pdf/improving_nations_vision_health.pdf

- Quigley, H. A., Park, C. K., Tracey, P. A., & Pollack, I. P. (2002). Community screening for eye disease by laypersons: The Hoffberger program. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 133(3), 386–392.

- Services, U. S. P. (2013). Third Annual Report to Congress on High-Priority Evidence Gaps for Clinical Preventive Services. Retrieved from https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/third-annual-report-to-congress-on-high-priority-evidence-gaps-for-clinical-preventive-services

- Shaikh, Y., Yu, F., & Coleman, A. L. (2014). Burden of undetected and untreated glaucoma in the United States. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 158(6), 1121–1129.e1121. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2014.08.023

- Varma, R., Vajaranant, T. S., Burkemper, B., Wu, S., Torres, M., Hsu, C., … McKean-Cowdin, R. (2016). Visual impairment and blindness in adults in the United States: Demographic and geographic variations from 2015 to 2050. JAMA Ophthalmology, 134(7), 802–809. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.1284

- Wittenborn, J. S., & Rein, D. (2016). The preventable burden of untreated eye disorders (p. 145). NORC at the University of Chicago. Chicago, IL.

- Wittenborn, J. S., Zhang, X., Feagan, C. W., Crouse, W. L., Shrestha, S., Kemper, A. R., … Saaddine, J. B. (2013). The economic burden of vision loss and eye disorders among the United States population younger than 40 years. Ophthalmology, 120(9), 1728–1735. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.01.068

- Zhao, D., Guallar, E., Gajwani, P., Swenor, B., Crews, J., Saaddine, J., … Friedman, D. S. (2017). Optimizing glaucoma screening in high-risk population: Design and 1-year findings of the screening to prevent (SToP) glaucoma study. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 180, 18–28. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2017.05.017