Abstract

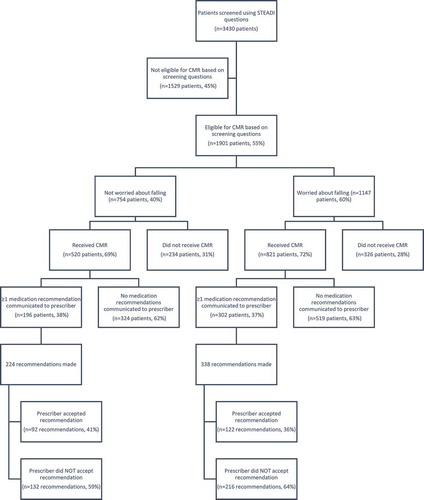

Background: Certain medications place older adults at higher risk for experiencing falls. This is a modifiable risk factor that may be managed by community pharmacists, but requires prescriber acceptance of recommendations. Previous studies indicate that prescriber acceptance of pharmacist recommendations may be impacted by patient-reported concerns. Objective: To examine the relationship between patient-reported fear of falling and prescriber acceptance of pharmacist recommendations. Methods: A prospective, observational study design was used. Eligible patients were age 65 and older and received care at one of 31 participating pharmacies. Patients were screened for falls risk using three evidence-based questions; patients screening positive were eligible for a comprehensive medication review. Data were collected via a prescriber response form. The primary outcome was the prescriber acceptance of pharmacist recommendations. Results: Pharmacists communicated 562 recommendations to prescribers, with 338 (60%) for patients who worried about falling. There was no significant difference in prescriber acceptance rate between those who worried about falling and those who did not (36.1% vs. 41.1%, X2 = 0.23, p = 0.43). However, patient pharmacy was a significant predictor of recommendation acceptance (p = 0.047). Conclusion: Prescribers were not more likely to consider a pharmacist’s recommendations regarding medications that contribute to falls risk for patients who worried about falling.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Falls are the leading cause of injury and injury-related death in older adults, and certain medications can put patients at an increased risk for falls. Community pharmacists have the ability and expertise to address medication-related risk factors; however, their success relies on the implementation of their recommendations by prescribers. Several studies have suggested that prescribers may be more likely to implement recommendations if the recommended changes are related to patient concerns. Therefore, this study aimed to identify whether including information about a patient’s fear of falling in communication with prescribers would influence the rate at which they accept pharmacists’ recommendations about medications that may increase fall risk. Our study found that a patient’s fear of falling was not significantly associated with increased acceptance of pharmacists’ recommendations by prescribers. However, prescriber acceptance varied across individual pharmacies, suggesting additional studies are needed to determine how to best communicate with prescribers.

Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

1. Introduction

Falls in older adults cause a significant burden to both patients and the healthcare system. Globally, 646,000 people die each year from a fall, with those older than the age of 65 at greatest risk (WHO | Falls, Citation2018). Following a nonfatal fall, patients are more likely to report serious and non-serious physical injury, as well as decline in physical and social activities (Stel, Smit, Pluijm, & Lips, Citation2004). Furthermore, one estimate placed the total fall-related medical costs at $50 billion for 2015 in the United States alone, making fall injuries one of the most expensive medical conditions (Carroll, Slattum, & Cox, Citation2005; Florence et al., Citation2018).

While a wide range of factors may contribute to an individual’s risk of falling, evidence suggests that medication use may play a significant role. A meta-analysis by Woolcott et al. (Citation2009) found a significant relationship between risk of falls and the use of antidepressants, benzodiazepines, sedatives/hypnotics, antipsychotics, and other medication classes. Accordingly, many of these medications are included in the American Geriatrics Society’s Beers’ Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults (Samuel, Citation2015). These medications are often referred to in the literature as “high-risk medications” due to their increased risk of adverse events, including falls, in older adults. One study showed that medication management services performed by general practitioners in Australia decreased the risk of falls in older adults by 39% (Pit et al., Citation2007).

Given their frequent contact with patients and training in medication management, community pharmacists can play an important role in reducing high-risk medication use and falls risk through medication management services (MMS) (Casteel, Blalock, Ferreri, Roth, & Demby, Citation2011). A key component of MMS in the community pharmacy setting is the pharmacist-led medication review, which is defined by The Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners as “a spectrum of patient-centered, pharmacist-provided, collaborative services that focus on medication appropriateness, effectiveness, safety, and adherence with the goal of improving health outcomes” (Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners, Citation2018). MMS performed by pharmacists has been demonstrated to be both economically and clinically beneficial for several disease states, including falls prevention (Doucette et al., Citation2017; Morrison & MacRae, Citation2015). Despite evidence of improved outcomes, the overall rates at which prescribers implement pharmacists’ recommendations following medication review vary widely between studies (Casteel et al., Citation2011; Doucette, McDonough, Klepser, & McCarthy, Citation2005; Kwint, Bermingham, Faber, Gussekloo, & Bouvy, Citation2013; Michaels, Jenkins, Pruss, Heidrick, & Ferreri, Citation2010; Morrison & MacRae, Citation2015; Roth et al., Citation2013). Reasons reported for not implementing a pharmacist’s recommendation include lack of willingness of the patient, lack of willingness to engage with pharmacists by the primary care physician, and information about the patients’ medical histories that was unknown to the pharmacist (Morrison & MacRae, Citation2015; Rose et al., Citation2016). These results suggest a need for more in-depth analysis of factors that affect prescriber implementation rates.

Another factor that may contribute to an individual’s risk of falling is having a fear of falling, with several studies finding that patients who fear falling are at an increased risk of falling than those who do not, even when controlling for other risk factors (Bruce, Hunter, Peters, Davis, & Davis, Citation2015; Allali, Ayers, Holtzer, & Verghese, Citation2017; Enderlin et al., Citation2015; Landers, Oscar, Sasaoka, & Vaughn, Citation2016). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed a toolkit that addresses risk factors such as fear of falling and high-risk medication use. The Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths, and Injuries (STEADI) toolkit is a comprehensive resource guide for health-care professionals to assess and address falls risk in their patients aged 65 and older (Stevens & Phelan, Citation2013). This toolkit provides resources and tools that can be applied across a wide variety of practice settings, including community pharmacies.

While several studies have demonstrated that direct communication strategies such as case conferences and established relationships between pharmacists and prescribers may influence implementation rates (Kwint et al., Citation2013), literature regarding clinical factors that contribute to the implementation of pharmacists’ recommendations by prescribers is lacking. One study by Hanus et al. (Citation2016) analyzed pharmacists’ interventions using the anticholinergic risk scale (ARS) but found that neither baseline ARS score nor baseline number of medications were predictors of implementation rate. This suggests that even robust clinical surrogates may not influence prescribers’ willingness to alter medication therapy. Boesen, Perera, Guy, and Sweaney (Citation2011) analyzed prescribers’ implementation of pharmacist recommendations by type of medication therapy problem (MTP) (i.e. guideline adherence, safety, cost-saving) and found that prescribers were more willing to accept recommendations regarding cost-savings as opposed to guideline adherence or safety. Since patients report being less likely to take higher-cost medications (Dolovich et al., Citation2008), this result suggests that prescribers may be more likely to address MTPs that reflect patient concerns. As stated previously, patients who fear falling are at a higher risk for falling. This fear also has a negative impact on their quality of life (Patil, Uusi-Rasi, Kannus, Karinkanta, & Sievänen, Citation2014). Therefore, we hypothesized that fear of falling may be a patient concern that increases prescriber acceptance of pharmacist recommendations intended to mitigate this risk.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient population and study design

Participants in this study were a subset of patients from a randomized controlled trial currently being conducted by investigators at the University of North Carolina Eshelman School of Pharmacy with funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Cooperative Agreement Number, 5 U01 CE002769-01]. A total of 65 pharmacies, all located in North Carolina, participated in the parent study. Thirty-one of these pharmacies were assigned to the intervention group.

Patients were included in the parent study if within the three months prior to the study, they: (1) were age ≥65 years, (2) filled ≥80% of their prescriptions at a participating intervention pharmacy, and (3) took ≥4 chronic medications of any kind or ≥1 high-risk medications. Medication use was determined using information from prescription claims and dispensing records. For the purpose of this study, high-risk medications included antidepressants, benzodiazepines, opioid analgesics, antipsychotics, sedative hypnotics, anticonvulsants, skeletal muscle relaxants, antihypertensives, and medications with anticholinergic effects.

A list of patients who met the eligibility criteria described above was provided to each participating pharmacy. Pharmacy staff screened eligible patients for falls risk by asking the following three questions from the STEADI toolkit: “Have you fallen in the past year?”, “Do you feel unsteady when standing or walking?”, and “Do you worry about falling?” If a patient responded “yes,” to at least one these questions, they were eligible to receive a comprehensive medication review (CMR).

During the CMR, pharmacists evaluated the patient’s medication regimen for high-risk medications and used evidence-based algorithms developed by the study team to recommend medication changes aimed at reducing the patient’s risk of falling. Pharmacists then used a prescriber communication form (Appendix A) to inform the patient’s prescriber(s) of any MTPs identified and corresponding recommendations. The prescriber communication form also provided space to document patient responses to the three STEADI screening questions.

Upon receiving a recommendation from a pharmacist, prescribers were asked to complete a prescriber response form (Appendix B) that included the following two statements: (1) “I plan to discuss medication information with the patient at their next visit” and (2) “I plan to make changes to this patient’s medication regimen based on this information.” For each statement, prescribers were requested to select either “yes,” “no,” or “unsure”. Pharmacists were required to reach out to prescribers via fax and/or phone a minimum of two times to demonstrate a good faith effort to obtain a completed response form back from each prescriber.

Participants included in this paper were limited to those who screened positive for falls risk (i.e., answered “yes” to at least one of the three STEADI screening questions), received a CMR, and had at least one specific medication regimen change recommendation recorded on the prescriber communication form. Regimen changes could include a change in dose, agent, administration or other change as determined by investigators.

2.2. Primary outcome variable

The primary outcome was prescriber acceptance of medication recommendations. A recommendation was coded as accepted if the prescriber checked “yes” to either “I will discuss medication information with the patient at their next visit” or “I will make changes to the patient’s medication regimen based on this information.” Recommendations for which follow-up from the prescriber was not obtained were considered not accepted.

2.3. Predictor variable

The primary predictor variable was participant response to the question “Do you worry about falling?” (Y/N), administered during the screening process.

2.4. Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS University Edition software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina). A chi-square test was performed to determine if the proportion of pharmacist recommendations accepted by prescribers differed between patients who reported being worried about falling compared to those who reported that they were not worried about falling. This relationship was also examined using logistic regression to control for age, gender, and pharmacy. Statistical significance was evaluated with Type I error set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

Participants were primarily female (73%) with a mean age of 75.7 ± 7.9 years. These demographics were similar between those who worried about falling and those who did not. Medication recommendations were communicated to prescribers on 562 occasions for 550 unique patients. Individual patients may have been included more than once if medication recommendations were sent to multiple prescribers. Qualifying medication recommendations were collected from 28 of the 31 participating pharmacies. One pharmacy did not complete any CMRs, and two others did not make any medication recommendations as part of their completed CMRs and were therefore not included in the final analysis. As shown in Figure , 338 (60%) recommendations were for patients who indicated that they worried about falling.

4. Prescriber acceptance

Overall, 214 (38.1%) recommendations were accepted by prescribers. The difference in prescriber acceptance rate between patients who reported worrying about falling and those who did not was not statistically significant (36.1% vs. 41.1%, respectively, X2 = 0.23, p = 0.43). This difference remained nonsignificant after controlling for age, gender, and pharmacy (p = 0.83).

5. Prescriber acceptance by pharmacy

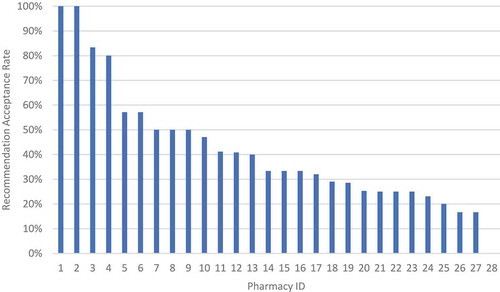

The median acceptance rate across the 28 pharmacies that made qualifying recommendations was 33%, with acceptance rates for individual pharmacies ranging from 0% to 100%. Of the 28 included pharmacies, 22 (79%) had acceptance rates of less than or equal to 50%. An exploratory logistic regression analysis was performed to analyze the effect of the individual pharmacy on prescriber acceptance rate, controlling for patients’ worry about falling, age, and gender. This analysis showed a statistically significant difference in acceptance rates (p = 0.047) across the individual pharmacies. Figure shows the distribution of acceptance rates by pharmacy. Table shows the results for individual pharmacies.

Table 1. Recommendations by Pharmacy ID

6. Discussion

Community pharmacists have the ability to identify patients at an increased risk for falls and leverage their expertise in medication therapy to reduce this risk. This study and others show, however, that acceptance of falls-related medication recommendations by prescribers is highly variable.

The results of this study suggest that knowledge related to patient concerns about falling does not influence prescribers’ decision to accept a falls-related medication recommendation from a community pharmacist. Consequently, more research examining clinical factors that may be leveraged to encourage collaboration between pharmacists and their patients’ prescribers is needed. That being said, it is widely acknowledged that a productive relationship between pharmacists and prescribers is multifactorial and the fact that this study demonstrated substantial variability in acceptance rates between individual pharmacies supports this concept.

This study was novel in its attempt to probe the impact of the patient-concerning factor of fear of falling in the CMR process. Importantly, it is unreasonable to expect most patients to understand the psychologic and physiologic relationships between their worries about falling, their medication regimen, and the risk of falling. Given the limited impact that fear of falling seems to have on prescriber acceptance of pharmacist recommendations related to high-risk medications, patients who do not understand the relationship between their medications and fall risk may not feel empowered to make medication changes. In this study, data were not collected regarding whether recommendations were also communicated to the patient, nor if the patient was accepting of the recommendation. Although patients may not initially make the connection between a medication they are taking and their risk of falls, explaining this information to them during a CMR and documenting a willingness to make medication changes may be useful information to provide to their prescriber. A pilot study by Mott et al. implemented a similar falls prevention program to the one described here, but with a key difference: changes in high-risk over-the-counter (OTC) product use (e.g. diphenhydramine, meclizine) were included in their analysis (Mott et al., Citation2016). This study showed a relatively high overall recommendation acceptance rate of 75%, speculated to be largely due to the inclusion of OTC products, which importantly, can be changed by the patient without prescriber consent (Mott et al., Citation2016). This result suggests that patients are willing to make informed decisions about their medication therapy when empowered and that perhaps by more directly involving patients in the decision-making process, it may result in improved outcomes. Despite significant advancements in the role of pharmacists as members of the health-care team, more research is required into the pharmacist’s role in patient-centered care, particularly as it relates to patient engagement.

7. Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, the study was conducted in independent community pharmacies in North Carolina that provide established clinical services, which may limit generalizability to other geographic areas and pharmacies with less well-established clinical services. In addition, the definition of prescriber acceptance for the purposes of this study was indirect, as the prescribers’ indication of plans to discuss or change medications does not necessarily mean that the changes were implemented. Ideally, a study would use claims data to determine if the recommended medication changes were actually implemented and maintained over a period of time. Furthermore, as previously mentioned, there was a broad distribution of acceptance rates between participating pharmacies suggesting that additional variables might play a more significant role in prescriber acceptance. Further research is warranted to determine those aspects of individual pharmacies and pharmacists that may influence prescriber acceptance of community pharmacists’ recommendations.

8. Conclusion

This study found no difference in the rate of prescriber acceptance of pharmacists’ recommendations between those patients who worry about falling and those who do not. Pharmacists have the knowledge and tools to address potentially inappropriate medication use in their older adult patients to reduce their fall risk. However, traditional barriers to implementation and success of clinical services in the community pharmacy setting remain. This study indicates the importance of continued research on strategies for effective collaboration between patients, community pharmacists, and prescribers.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Stefanie Ferreri

Stefanie Ferreri The authors on this team conduct research in the outpatient pharmacy setting with a special interest in advancing clinical practice for community pharmacists. The research group aims to generate best practices to optimize medication management and improve patient outcomes. Our work focuses on integrating pharmacists into team-based care with an overall goal to improve quality of health care. The outcomes resulting from this study are based on community pharmacists coordinating patient care in regards to falls prevention. The methods of this study add important knowledge surrounding design, implementation, and analysis of practice-based research in a community pharmacy setting.

References

- Allali, G., Ayers, E. I., Holtzer, R., & Verghese, J. (2017). The role of postural instability/gait difficulty and fear of falling in predicting falls in non-demented older adults. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 69, 15–9. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2016.09.008

- Boesen, K. P., Perera, P. N., Guy, M. C., & Sweaney, A. M. (2011). Evaluation of prescriber responses to pharmacist recommendations communicated by fax in a Medication Therapy Management Program (MTMP). Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy, 17(5), 345–354. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2011.17.5.345

- Bruce, D., Hunter, M., Peters, K., Davis, T., & Davis, W. (2015). Fear of falling is common in patients with type 2 diabetes and is associated with increased risk of falls. Age and Ageing, 44(4), 687–690. doi:10.1093/ageing/afv024

- Carroll, N. V., Slattum, P. W., & Cox, F. M. (2005). The cost of falls among the community-dwelling elderly. Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy : JMCP, 11(4), 307–316. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2005.11.4.307

- Casteel, C., Blalock, S. J., Ferreri, S., Roth, M. T., & Demby, K. B. (2011). Implementation of a Community Pharmacy–Based Falls Prevention Program. The American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy, 9(5), 310–319.e2. doi:10.1016/j.amjopharm.2011.08.002

- Dolovich, L., Nair, K., Sellors, C., Lohfeld, L., Lee, A., & Levine, M. (2008). Do patients’ expectations influence their use of medications? Qualitative study. Canadian Family Physician Me´Decin De Famille Canadien, 54(3), 384–393.

- Doucette, W. R., McDonough, R. P., Herald, F., Goedken, A., Funk, J., & Deninger, M. J. (2017). Pharmacy performance while providing continuous medication monitoring. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association, 57(6), 692–697. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2017.07.006

- Doucette, W. R., McDonough, R. P., Klepser, D., & McCarthy, R. (2005). Comprehensive medication therapy management: Identifying and resolving drug-related issues in a community pharmacy. Clinical Therapeutics, 27(7), 1104–1111. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(05)00146-3

- Enderlin, C., Rooker, J., Ball, S., Hippensteel, D., Alderman, J., Fisher, S. J., … Jordan, K. (2015). Summary of factors contributing to falls in older adults and nursing implications. Geriatric Nursing, 36(5), 397–406. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2015.08.006

- Florence, C. S., Bergen, G., Atherly, A., Burns, E., Stevens, J., & Drake, C. (2018). Medical Costs of Fatal and Nonfatal Falls in Older Adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66, 693–698. doi:10.1111/jgs.15304

- Hanus, R. J., Lisowe, K. S., Eickhoff, J. C., Kieser, M. A., Statz-Paynter, J. L., & Zorek, J. A. (2016). Evaluation of a pharmacist-led pilot service based on the anticholinergic risk scale. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association, 56, 555–561. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2016.02.015

- JCPP | Medication Management Services (MMS) Definition and Key Points. (2018). Retrieved from https://jcpp.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Medication-Management-Services-Definition-and-Key-Points-Version-1.pdf

- Kwint, H. F., Bermingham, L., Faber, A., Gussekloo, J., & Bouvy, M. L. (2013). The relationship between the extent of collaboration of general practitioners and pharmacists and the implementation of recommendations arising from medication review: A systematic review. Drugs and Aging, 30(2), 91–102. doi:10.1007/s40266-012-0048-6

- Landers, M. R., Oscar, S., Sasaoka, J., & Vaughn, K. (2016). Balance Confidence and Fear of Falling Avoidance Behavior Are Most Predictive of Falling in Older Adults: Prospective Analysis. Physical Therapy, 96(4), 433–442. doi:10.2522/ptj.20150184

- Michaels, N. M., Jenkins, G. F., Pruss, D. L., Heidrick, J. E., & Ferreri, S. P. (2010). Retrospective analysis of community pharmacists’ recommendations in the North Carolina Medicaid medication therapy management program. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association : JAPhA, 50(3), 347–353. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2010.09021

- Morrison, C., & MacRae, Y. (2015). Promoting Safer Use of High-Risk Pharmacotherapy: Impact of Pharmacist-Led Targeted Medication Reviews. Drugs - Real World Outcomes, 2(3), 261–271. doi:10.1007/s40801-015-0031-8

- Mott, D. A., Martin, B., Breslow, R., Michaels, B., Kirchner, J., Mahoney, J., & Margolis, A. (2016). Impact of a medication therapy management intervention targeting medications associated with falling: Results of a pilot study. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association, 56(1), 22–28. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2015.11.001

- Patil, R., Uusi-Rasi, K., Kannus, P., Karinkanta, S., & Sievänen, H. (2014). Concern about falling in older women with a history of falls: Associations with health, functional ability, physical activity and quality of life. Gerontology, 60(1), 22–30. doi:10.1159/000354335

- Pit, S. W., Byles, J. E., Henry, D. A., Holt, L., Hansen, V., & Bowman, D. A. (2007). A Quality Use of Medicines program for general practitioners and older people: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Medical Journal of Australia. doi:10.1007/978-94-6300-842-6_3

- Rose, O., Mennemann, H., John, C., Lautenschläger, M., Mertens-Keller, D., Richling, K., … Köberlein-Neu, J. (2016). Priority setting and influential factors on acceptance of pharmaceutical recommendations in collaborative medication reviews in an ambulatory care setting - Analysis of a cluster randomized controlled trial (WestGem-study). PloS One, 11(6). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0156304

- Roth, M. T., Ivey, J. L., Esserman, D. A., Crisp, G., Kurz, J., & Weinberger, M. (2013). Individualized medication assessment and planning: Optimizing medication use in older adults in the primary care setting. Pharmacotherapy, 33(8), 787–797. doi:10.1002/phar.1274

- Samuel, M. J. (2015). American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(11), 2227–2246. doi:10.1111/jgs.13702

- Stel, V. S., Smit, J. H., Pluijm, S. M. F., & Lips, P. (2004). Consequences of falling in older men and women and risk factors for health service use and functional decline. Age and Ageing, 33(1), 58–65. doi:10.1093/ageing/afh028

- Stevens, J. A., & Phelan, E. A. (2013). Development of STEADI: A Fall Prevention Resource for Health Care Providers. Health Promotion Practice, 14(5), 706–714. doi:10.1177/1524839912463576

- WHO | Falls. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/falls

- Woolcott, J. C., Richardson, K. J., Wiens, M. O., Patel, B., Marin, J., Khan, K. M., & Marra, C. A. (2009). Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Archives of Internal Medicine, 169(21), 1952-1960. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.357