Abstract

Abstract: Studies on the exposure to occupational hazards among bakers and the strategies they employ to control occupational hazards are lacking in Ghana. In this study, we aimed at examining the exposure to occupational hazards among bakers in the Kumasi Metropolis of Ghana and further explore their coping mechanisms. By employing a cross-sectional design, the study was conducted among 172 bakers in the Kumasi Metropolis of Ghana. We found that the participants were exposed to different types of occupational hazards, including physical (noise, flour dust/smoke, fire, and high temperature), biological (mosquitoes, insects and rodents), psychosocial (stress, verbal abuse, and poor interpersonal relationship), chemical (chemicals in the local soap used to clean and wash napkins after baking), and ergonomic hazards (standing, sitting and bending repetitively). The health risks associated with exposure to the different forms of occupational hazards include rhinitis, excessive cough, irritation of the eye and wheezing, resulting in breathlessness, burns, scalds, dizziness and bodily pain (lower back pain, shoulder pain, neck pain, pain in the hand and, muscle spasm and pain in the leg). The coping mechanisms employed to control occupational hazards comprise the use of a wooden and metallic peel to place and remove bread from the oven, use of peel to move excess fire from the oven, use of mosquito repellent and coil, rest breaks and staying hydrated. The findings of this study are therefore critical to informing policymakers in implementing occupational health and safety policies to safeguard the health of bakers in Ghana and other LMICs.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Occupational hazards remain a major health challenge in the informal sector. However, not much information is available in Ghana concerning the specific occupational hazards bakers are exposed to and their coping mechanisms. This study examined exposure to occupational hazards among bakers and the measures they have adopted to deal with the hazards. The study revealed that bakers are exposed to varied types of occupational hazards. Because of this, they have employed many strategies to contain their exposure to occupational hazards; however, these strategies to address occupational hazards appear to be less effective in containing the hazards. Thus, further policy measures to lessen exposure to occupational hazards among bakers in Ghana have been proposed for the implementation by policymakers.

1. Introduction

As the attention of development actors turns towards safety and health at the workplace, international bodies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Labour Organisation (ILO) are increasingly advocating the implementation of occupational health and safety standards to ensure health and safety of workers. This is because the work environment and its varied circumstances have both negative and positive effects on the health and safety of its workers. For instance, harmful work environment accounts for significant causes of morbidity, mortality, and disability (Bhuiyan, Citation2016; WHO, Citation2006).

Globally, workplace accidents lead to over 2.3 million deaths annually (International Labour Organization, Citation2005; Takala et al., Citation2014). Occupational injuries and diseases that result from harmful work environments account for approximately 4 percent loss of the world’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Machida, Citation2010). This suggests that occupational health and reduced working capacity of workers causes an economic loss of about 10–20 percent of the Gross National Product of a country (WHO, Citation1994). Thus, safety and health at the workplace cannot be seen solely as a sound economic policy but also as a basic human right (Amponsah-Tawiah & Dartey-Baah, Citation2011). Approximately 75 percent of the world’s labour force live in developing countries, with only 5–10 percent having access to occupational health services (Kumar et al., Citation2016).

To date, Ghana has no Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) national policy to streamline issues concerning occupational hazards (Adei & Kunfaa, Citation2007). The two main statutes that back the implementation of OHS in Ghana are the Factories, Offices and Shops Act 1970 (Act, 328) and Workmen’s Compensation Law 1987 (PNDC Law 187): Act 328 focuses on meeting the internationally accepted standards for safety, health and welfare of workers. Ghana’s Factories, Offices and Shops Act, 1970 (Act 328) Part 5 sections 10, 11 and 12 make it mandatory for employers or occupiers of the premises to report accidents that cause death or disabled employees for more than three days. Again, dangerous occurrences and industrial diseases are to be reported to the Chief Inspector or Inspector of factories of the district. The provisions of the Factories, Offices and Shop Act of 1970 are insufficient in scope since most industries, agricultural and the informal sectors (including those in the bakery industry) are not specifically covered (Clarke, Citation2005). The Workmen’s Compensation Law 1987, on the other hand, directs the payment of cash compensation by employers to employees in the event of work-related injuries and diseases as well as in the unlikely event of death. The benefits are payable to the employer’s dependents through the Law Court (Amponsah-Tawiah & Dartey-Baah, Citation2011; Asumeng et al., Citation2015), with an accumulative amount of GH¢ 13,541,106.09 being paid to employees from the period of 2008 to 2013 across the public and private sector (Ministry of Employment and Labour Relations, Citation2016).

In Ghana, the baking industry is an essential sub-sector of the economy. The sector plays a vital role in employment creation and income generation. This implies that bakers contribute to their livelihoods, their communities and the country at large (Amponsah-Tawiah & Dartey-Baah, Citation2011). Despite the enormous contribution, the baking industry, like other occupations is prone to occupational health and safety challenges (Joshua et al., Citation2017). Doaa et al. (Citation2017) highlighted that bakery poses several hazards to the health of its workers. These hazards include electric shock, fall/explosion, cuts, burns, skin irritation, muscle problems, chest tightness, cough, catarrh, sneezing and symptoms of asthma (Joshua et al., 2017). Because of this, baking as an economic activity exposes workers to work injuries and diseases that affect the production and productivity, which translates into low incomes (Stoia & Oancea, Citation2008; Yossif & Abd Elaal, Citation2012). Further, occupational injuries and diseases among workers result in absenteeism, reduces the ability of households to earn income and affect the local and national economy (Doaa et al., Citation2017).

Studies on occupational hazards have been focused on knowledge, attitude and safety practices (Aluko et al., Citation2016; Amosu et al., Citation2011; Anozie et al., Citation2017; Gajida et al., Citation2019; Gebrezgiabher et al., Citation2019; Okafoagu et al., Citation2017; Sabitu et al., Citation2009). Almost all these studies conclude that participants have good knowledge and attitude towards occupational hazards. Despite this good knowledge, evidence suggests that informal sector workers are still exposed to occupational hazards (Doaa et al., Citation2017; Stoia & Oancea, Citation2008; Yossif & Abd Elaal, Citation2012). With the rise in informal sector activities especially bakery in Ghana and other developing countries, it is expected that the incidence of occupational hazards among bakers is likely to increase which may negatively impact their health outcomes and healthcare expenditure. However, to date, little is known about bakers’ exposure to occupational hazards in Ghana and the strategies they employ to limit their exposure to workplace hazards. Joshua et al. (2017) have studied knowledge of occupational hazards and use of protective measures among bakery workers in Nigeria. However, their study was not comprehensive as they failed to identify the specific biological, physical, ergonomic, chemical and psycho-social hazards bakers are exposed to and the specific measures they have adopted to deal with their exposure to occupational hazards. Health/policy intervention that aims at addressing occupational hazards among bakers may need specific occupational hazards (that is physical, ergonomic, chemical and psycho-social hazards bakers) and their dynamics to ensure a successful outcome. This knowledge gap is partly attributed to inadequate studies documenting exposure to occupational hazards among bakers in Ghana and other developing countries. The objectives of this study are to: 1) examine the specific occupational hazards bakers are exposed to 2) explore the strategies employed by bakers to deal with their exposure to occupational hazards in the Kumasi metropolis of Ghana. Identifying the specific strategies employed by bakers to address their exposure to occupational hazards could be useful measure to estimate how effective these measures are in helping to control occupational hazards among bakers. It could further help to measure the preparedness and willingness of both employees and employers in contributing to occupational health and safety issues in the bakery industry. Understanding the exposure to occupational hazards among bakers is therefore critical to informing policymakers in the formulation and implementation of occupational health and safety policies to safeguard the health of bakers in Ghana and other low-and middle-income countries. Findings from the study will inform occupational health and safety policies, procedures, Acts and legislation established in the country towards the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goal 8 (decent work and economic growth) specifically target 8.8 indicates the need “to protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers and those in precarious employment of which bakery is no exception. The study also partly contributes to the realisation of Sustainable Development Goal 3, which seeks to improve health and wellbeing for all at all ages by 2030.

2. Methods

2.1. Setting and research design

The study was conducted in the Kumasi Metropolis of Ghana. The metropolis is the second most populous settlement in the country with an annual growth rate of 2.7 percent (Ghana Statistical Service [GSS], Citation2014). The increase in population growth rate is due to the attractiveness (tourism, and employment opportunities) of the metropolis (GSS, Citation2014). Approximately 91.2 percent of the labour force is employed in the private sector with 79.2 percent of the employed population working in the private informal sector. Small/medium scale-manufacturing industries employ 13.6 percent of the labour force. The use of modern production methods to produce both traditional and modern products dominates this sub-sector. Notable among the activities conducted include brewery and food processing, which creates and promotes job opportunities for the youth. Most of the baking industries are located in Asafo and Fanti New Town. Asafo and Fanti New Town are one of the well-patronized baking centres in the Kumasi Metropolis. They are the hub for informal bakery units that produce baked foods to serve the metropolis and beyond. The bakery units operating within the enclave are composed of flour processors, bread makers and batteries.

This study used a cross-sectional survey to examine exposure to occupational hazards among bakers in the Kumasi Metropolis. A cross-sectional survey was used because data were gathered from the participants at a specific point in time (Dillman, Citation2000; Hall, Citation2008; Levin, Citation2006; Oslen & George, Citation2004).

2.2. Sampling frame and technique

We first undertook a headcount of the bakers to determine the sampling frame; this approach was necessitated by the absence of data on the population of bakers. The headcount covered the employers and employees working as bakers within the study area. The criterion for selecting the bakers was based on those who are actively engaged in baking and those who had employees. A census was conducted to cover all bakers because the study group was small and easy to identify in the study area. This implied that the results obtained from respondents were generalised based on the sampling technique employed. With the detailed information on the location and contacts, respondents were easily located and interviewed.

After the headcount/preliminary census, each bakery unit had different activities being conducted. An average of four groups of employees, which comprised pan cleaners, slicers, oven bakers and mixers. The headcount identified 39 employers at Fanti New Town and Asafo. Each employer was selected purposively together with three employees to respond to questions through a questionnaire administration. In addition, the study identified 16 mixers who were actively involved in mixing the flour. Thus, a total sample frame for the study was 172 representing both employers and employees.

The study adopted a purposive sampling technique in selecting the bakers because of their knowledge and experience in the baking profession.

2.3. Data collection instrument and procedure

Questionnaire was used as the data collection instrument. This was designed and administered to bakers. Closed-ended questions were mostly used to enhance high response to sensitive questions. Data gathered included socio-demographic and economic information (sex, education status, age of respondents, working experience, among others), and exposure to occupational hazards (biological, ergonomic, psychosocial, and physical hazards) and strategies adopted to curb the effects. The questionnaire was developed in English but was translated into Twi (the local language of the study participants) considering the World Health Organisation guidelines for assessing instruments (Üstun et al., Citation2005). To ensure validity, the translation was done by the first author and was followed by independent checks and re-checks by the authors to ensure quality control (Agyemang-Duah et al., Citation2019). Three research assistants who have knowledge on occupational hazards were recruited from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) to help administer the data collection instrument. However, the first author monitored the data collection process to ensure quality control. In all, each administered questionnaire lasted 40 min on the average.

2.4. Ethical consideration

A letter of introduction was obtained from the head of the Department of Planning, KNUST and sent to the heads of the Kumasi Metropolitan Labour Department, Bread Union, Environmental Health Department, and the Factories Inspectorate before the data collection exercise began. The respondents were also informed of the purposes and procedures involved in the study and the time needed to complete each questionnaire. They were also reassured that all information provided would be treated with the required confidentiality and anonymity. Further, informed and verbal consent was sought from the respondents before the data collection exercise began. They were further assured that their participation in the study was voluntary and that they were free to opt-out at any time.

2.5. Data analysis

The primary data were collated, edited and harmonised after the field survey. This was to ensure quality control. The quantitative data were collected using Kobo Collect Software and exported using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 21 to organise the data into categories that were useful to the study. The application of the software made it possible for the enumeration of data in percentages, charts/graphs, and tabular representations. Descriptive deductions (cross-tabulation, frequencies, and percentages) were adopted and used to provide a detailed explanation of the tables and charts produced from the quantitative analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and socio-economic characteristics of the respondents

The majority (59.3%) of the respondents were females. The female dominance could be explained by the traditional role of women, as household managers hence are responsible for the day-to-day administration/ management of processing food. The study revealed that 41.3% of the respondents had no level of formal education. This demonstrates a low educational background among the respondents. The likely explanation for this is that the informal sector is characterised by free entry and exit, hence allow people with low educational levels to engage in informal economic activities. This in a way affects their understanding of vital occupational health and safety issues.

The majority (55.8%) of the respondents indicated that they had worked in the bakery industry for more than 11 years. The higher work experience of the respondents could have implications on the study as most of them would be able to bring to light their exposure to occupational hazards. The study revealed that most respondents earned between 500 and 1,000 Ghana Cedis (1 USD = 4.97 GHS as at 31 January 2019) monthly (see Table ).

Table 1. Demographic and Socio-economic characteristics of the respondents

3.2. Exposure to occupational hazards

Bakers are exposed to biological, physical, ergonomic, chemical and psychosocial hazards. Bakers’ provided information on their exposure to occupational health and safety hazards, the sources of the hazards and strategies adopted to minimise the effects. The total sample of the respondents were 172 comprising pan cleaners (39), slicers (39), oven bakers (39), dough mixers (16) and employers (39). Therefore, the sample size was made up of 133 employers and 39 employees. As a result of the application of multiple responses, the frequencies are probably more than the required sample size for the study

3.3. Exposure to physical hazards

Physical hazards discussed are grouped into noise, smoke/dust, temperature (heat from the oven) and fire.

3.3.1. Noise

The bakery environment involves flour milling and mixing by using machines such as a dough-kneading machine, turbo sifters, mixer, roll plant and hand tray for shaping the edible dough. This shows that dough mixers are always exposed to noise once they start kneading the flour. From the survey, all dough mixers were exposed to noise because of their activity.

The dough mixers disclosed that they did not feel comfortable wearing ear protective devices. However, further discussions with them revealed that they did not know the importance of using ear protective devices during their operation. When asked to rate their noise exposure, 75 percent of mixers rated their exposure as high (above 85 Db).

3.3.2. Strategies against the noise

In preventing the effects associated with noise, none of the employees had structural or mechanical modifications such as earplugs, mufflers, and noise protection enclosures, which provide noise reduction.

3.3.3. Dust/Smoke

Flour dust is associated with employees who are engaged in mixing the dough. It appeared from the survey that all dough mixers were exposed to flour dust. Among the dough mixers; runny nose, excessive cough, wheezing, irritation of the eye and respiratory problems were some effects resulting from flour dust (see Table ).

Control measures adopted by bakers to protect themselves from the effect of the flour dust included having active ventilation (88%) and the use of handkerchief (12 percent). The dough mixers did not use the nose mask because it was uncomfortable during breathing.

The survey revealed that 92 percent of the employers used traditional ovens to bake bread and pastries because it was cheaper to purchase fuelwood. All oven bakers and 97 percent of the pan cleaners were exposed to smoke because of the fuelwood. Materials such as metal or wood slates and sacks were used to cover the oven during the burning of the fuelwood. The oven bakers checked on frequently to ensure that the logs placed in the oven were burnt. Notwithstanding, pan cleaners were exposed to smoke because they were required to clean, grease and pack the baking pans at the same compound. From the survey, two percent of the employers had created chimneys to direct the smoke away from the baking space.

Exposure to smoke resulted in occupational diseases such as rhinitis, excessive cough and wheezing resulting in breathlessness. The smoke also results in residential hazards since the activities are conducted in a residential environment where people live. The smoky environment was seen as a normal issue since they use fuelwood.

3.3.4. Strategies adopted against smoke

The strategies respondents have adopted against smoke include staying away from fire, frequent break, working in an open space, active ventilation and adjustments of ovens (Table ).

Table 2. Effects of flour dust reported by dough mixers (N = 16)

Table 3. Exposure to Smoke and measured adopted by Bakers

3.3.5. Fire hazard

The use of fire predominates in baking environment since fuelwood is the main source of energy for baking of bread and pastries. All oven bakers interviewed disclosed that they were exposed to fire hazards. Employers (63 percent) and employees (74 percent) rated exposure to fire hazards as high. Approximately 41 percent of employers indicated that they did get close to the fire when they wanted to check if the ovens were hot and whether the bread had been well baked. Both employers and oven bakers sustained burns because they used their hands in lifting hot baking pans from the oven.

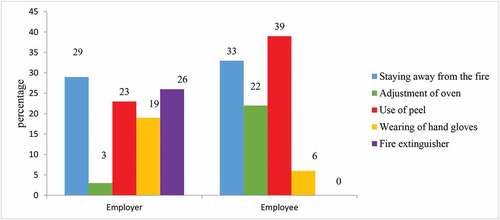

3.3.6. Measures adopted against fire hazards

The most frequent measure adopted by employers and employees to fight against fire hazard is the use of a wooden and metallic peel to place and remove bread from the oven as well as regulate the fire in the oven. Surprisingly, some employers used hand gloves to hold the wooden and metallic peel to prevent burns from the hot oven (Figure ). Employees, on the other hand, commented that the use of hand gloves made it difficult to work with the peels since they had to remove the baked bread from the oven.

Notwithstanding the effects of fire, out of the 12 employers who are members of the Ghana Flour Users Association, eight of them had fire extinguishers at their workplaces. Employers indicated that process for acquiring them was cumbersome and expensive.

3.3.7. High temperature

The high temperature indicated was related to fire from the oven. Approximately 53 percent and 59 percent of employers and employees claimed their exposure to high temperature from the ovens as uncomfortable. According to Avula et al. (Citation2015), the standard temperature at the baking premises should be between 55°C—60°C. Among the effects reported by employees were burns, scalds, fainting, and dizziness that recorded 33 percent, 23 percent, five percent, and 39 percent, respectively. Employers also sustained burns (80 percent), (seven percent) scalds because of their exposure to the hot ovens.

3.3.8. Strategies employed to control high temperature

Strategies were, however, adopted to help curb the exposure of bakers to the effects of high temperature. Strategies ranged from physical barriers (use of metallic or wood sacks to cover the oven), manual regulation (by removing excess fire from the oven with a peel), rest breaks and staying hydrated were adopted by both employers and employees (Table ).

Table 4. Effects and strategies adopted against high temperature

3.4. Exposure to biological hazard

All dough mixers complained of being exposed to mosquitoes (34 percent), insects (34 percent) and rodents (32 percent), this is because ingredients such as flour, wheat, margarine, and sugar were kept in their working room. Oven bakers were least (21 percent) exposed to mosquito bites because of extreme temperatures from the oven. However, slicers who mostly started their work between the hours of 4 pm to 10 pm were exposed to mosquito bites (95 percent) (see Table ).

Table 5. Exposure of Bakers to Biological Hazard and Control Measures Adopted

3.4.1. Strategies employed to control their exposure to biological hazards

To protect themselves from mosquito bites bakers resulted in wearing long-sleeved clothes and the use of mosquito repellent and coil. Another method adopted by bakers was the use of burning orange peels gathered from an orange seller, others also resorted to drinking “Dr Ceaser Lina Energy Tea” as a remedy to prevent malaria.

3.5. Exposure to psychosocial hazard

Stress (workload), verbal abuse and poor interpersonal relationships are some types of psychosocial hazards reported. Approximately 90 percent of employers indicated that their work was stressful, since they worked more than 12 h daily. These results in injuries, low productivity, absenteeism, and poor concentration at work (Table ). This contributes to a stressful and an unfriendly work environment.

Table 6. Exposure of Bakers to Psychosocial hazard

3.5.1. Strategies against psychosocial hazard

Employers adopted strategies such as showing respect at the workplace (39 percent), the reduction in work hours (22 percent) and settling of disputes among employees (39 percent) to reduce psychosocial hazards at the workplace (Table ).

3.6. Exposure to chemical hazard

Approximately 72 percent of the pan cleaners were exposed to chemical hazards because they used bleach and “Azuma blow” to clean and wash napkins after baking. The perceived effects of the chemical hazard were mainly whitlow (44 percent) and irritation of the eye (56 percent) (Table )

Table 7. Exposure of Pan Cleaners to Chemical hazard

3.7. Exposure to ergonomic hazard

The working postures of bakers were in a form of standing, sitting and bending, which were done repetitively. Pan cleaners, slicers stood for less than two hours when working because their activity required them to sit for close to seven hours each day. Sitting, standing, bending and lifting of heavy equipment for a longer period led to musculoskeletal disorders such as lower back pain, shoulder pain, and pain in the hand (see Table ).

Table 8. Exposure of Bakers to Ergonomic hazard

The muscles around the joints are subjected to tension. These could lead to low productivity among bakers and hence reduced incomes and profits on the side of employers.

3.7.1. Strategies adopted against ergonomic hazard

The prevalence of ergonomic hazard was controlled by ensuring proper lifting, continuous change in work posture and adhering to mini-breaks (Table ). Moving large baking trays and tins of flour dough from the mixer room to the bakery poses many health risks. They are usually heavy and bulky.

4. Discussion

This study examines the exposure to occupational hazards among bakers in the Kumasi Metropolis of Ghana. The study found that the participants were exposed to various forms of occupational hazards such as physical, chemical, ergonomic, psycho-social and biological hazards. This finding was consistent with a previous study that found that bakers are exposed to biological, physical, ergonomic, chemical and psycho-social hazards (Yossif & Abd Elaal, Citation2012). In addition, Shezi et al. (Citation2019) have found that traditional medicine traders in South Africa are exposed to varied forms of occupational hazards including ergonomic, physical, biological and environmental hazards. It could be inferred that the exposure to occupational hazards may further expose the respondents to economic and social consequences through the payment of medical bills, absence from work and loss of productivity, which could go a long way to undermine the quality of life and wellbeing of bakers in Ghana and other low and middle-income countries. To this end, specific interventions such as the formulation and implementation of occupational health and safety policy that incorporate frequent education and sensitisation exercise on occupational hazards may help scale down the exposure to hazards among bakers in Ghana.

The study revealed that the specific physical hazards the participants were exposed to include noise, smoke/dust, temperature (heat from the oven) and fire, which is consistent with previous studies (Doaa et al., Citation2017). Exposure to noise, for instance, could cause hearing impairments among the participants and may result in pain in the ear (discharge), deafness and psychosocial hazards (stress, anxiety) (Mellor & Webster, Citation2013; Wachira, Citation2016; Yossif & Abd Elaal, Citation2012). Apart from their exposure to noise, most respondents were exposed to smoke and flour dust, which resulted from the use of traditional ovens to bake bread and pastries and inhalation of flour dust, respectively. Higher exposure to smoke could also result in health and safety problems among the bakers as evident in the Giza Governorate (Doaa et al., Citation2017). Similar to previous studies, this study found health outcomes of exposure to smoke to include rhinitis, excessive cough and wheezing, which could result in breathlessness (Po et al., Citation2011; Smoke, Citation2012) and consequently death (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2013). The inhalation of flour dust that may contain fungi, silica, and bacterial endotoxins is considered to be harmful to human health (Rushtan, Citation2007). In line with Avula et al. (Citation2015), the major health problems associated with flour dust were irritation of the eye, excessive cough, and wheezing. This implies that bakers are probably affected by chronic pulmonary diseases such as bronchial asthma in the long term.

The study further found that most respondents were exposed to fire because they predominantly use fuelwood as their main source of energy for baking of bread and pastries. To this end, the participants sustained burns because they used their hands in lifting hot baking pans from the oven. This finding agrees with Yossif and Abd Elaal (Citation2012), who indicated that 14 percent of bakers were exposed to burns in Benha City. Besides their exposure to fire hazards, the study revealed that the participants were exposed to a high temperature, which resulted in burns, scalds, fainting, and dizziness. These have confirmed studies by Yossif and Abd Elaal (Citation2012), Aguwa and Arinze-Onyia Sussan (Citation2014), and Ahmed et al. (Citation2009) who stated that fainting, scalds, and burns are common effects of high temperature at the bakery industries. Heat stress leads to heat cramps, heat stroke and long-term death (Commission on Health, Safety and Workers’ Compensation, Citation2010).

The study revealed that the specific biological hazards the participants were exposed to include mosquitoes, insects, and rodents because ingredients such as flour, wheat, margarine, and sugar were kept in their working room. Malaria was noted as the predominant effect of biological hazard participants were exposed to. Besides the biological hazards, the study reported that the participants were exposed to stress (workload), verbal abuse and poor interpersonal relationship as the types of psychosocial hazards. These psychological hazards resulted in injuries, low productivity, absenteeism and poor concentration at work. Employers refuse to increase their staff because the informal sector is geared towards profit maximisation (De Bruin & Taylor, Citation2005). This contributes to a stressful and an unfriendly working environment. These psychosocial hazards affect workers and their families as well as their jobs since sickness is related to loss of productivity and hence low incomes. Besides, stress reduces workers’ productivity, which causes an economic loss of approximately 4–5 percent of the Gross National Product of many countries (Greenlund et al., Citation1995). These also have physical, mental, social and health implications on bakers (Greenlund et al., Citation1995). In this study, participants were exposed to chemical hazards. Bakers especially pan cleaners used sodium hydroxide, bleach and other chemicals for cleaning the baking environment, which cause skin infection and irritation to the eye (Aguwa & Arinze-Onyia Sussan, Citation2014; Arrandale et al., Citation2013). Due to the chemicals used in the preparation of the local soap “Azuma blow” cleaners, develop whitlow and parts of their skin peel off.

This study revealed that bakers assumed working postures such as standing, sitting and bending. However, occupational activities such as weight lifting, poor work posture, repetitive movements and operating of the dough mixer led to an ergonomic hazard (Ghamari et al., Citation2009). The risk of musculoskeletal disorders increases with an increase in the length of working (Yossif & Abd Elaal, Citation2012). Further, this finding is also in line with the assertion by Aluko et al. (Citation2016) that exposure to occupational hazards leads to musculoskeletal problems (such as low back pain) as a result of prolonged standing and stress-related conditions. Besides, sitting, standing, bending and lifting of heavy equipment for a longer period led to musculoskeletal disorders such as lower back pain, shoulder pain, and pain in the hand. Ghamari et al. (Citation2009) and Yossif and Abd Elaal (Citation2012) indicated that awkward and repetitive work posture led to pain in the back and shoulder, which are common in most developing countries. This can be attributed to the muscles around the joints being subjected to tension. These could lead to low productivity among bakers and hence reduced incomes and profits on the side of employers.

The study found that the participants employed varied strategies to control their exposure to the occupational hazards they were exposed to. Because different occupational hazards may require different strategies (Joshua et al., Citation2017), participants have employed different strategies to control their exposure to each type of occupational hazard. While operating in open spaces and the use of handkerchiefs has been employed against flour dust, the use of a wooden and metallic peel to place and remove bread from the oven and regulate the fire in the oven have been adopted against fire hazards. Regarding the high-temperature exposure, the study revealed that strategies employed ranged from physical barriers (use of metallic or wood sacks to cover the oven), manual regulation (by removing excess fire from the oven with a peel), rest breaks and staying hydrated. The prevalence of biological hazards was controlled through wearing long-sleeved clothes and the use of mosquito repellent and coil, whilst psychological hazards were reduced by showing respect at the workplace, reduction in work hours and settling of dispute and ergonomic hazards were controlled by ensuring proper lifting, continuous change in work posture and adhering to mini-breaks. This implies that the strategies employed by the participants could help lessen their exposure to occupational hazards. It was, however, a surprise to note that in preventing the effects associated with noise, none of the employees had structural or mechanical modifications such as earplugs, mufflers, and noise protection enclosures, which provide a noise reduction of 85 Db (Wachira, Citation2016). This could be a result of poor knowledge of the importance of using ear protective devices during their operation to reduce the noise-induced hearing loss. This implies that the participants need to be sensitised or educated to deepen their knowledge of the importance of using ear protective devices to control noise. Also, effective collaboration between all OHS institutions to ensure the use of personal protective equipment among informal workers including bakers to prevent injuries (Ametepeh, Citation2011).

Even though we noted that bakers have employed strategies to reduce their exposure to occupational hazards, they are still exposed to the hazards. Our findings have implications for existing laws and regulations related to occupational health and safety standards in Ghana. First, results suggest that most of the measures adopted by the participants are less effective in containing occupational hazards. Two, not much has been done by the government to enforce health and safety standards to protect the health and safety of informal sector workers especially bakers. In this regard, there is a need to have a comprehensive provision of occupational health and safety standards and practices in all sectors of the economy especially the informal sector in Ghana (Annan et al., Citation2015). Three, we further stress the need for employers in the bakery industry to train their workers on occupational health and safety practices and the essence of using personal protective equipment. Collaboration between the employers, employees, and the established body responsible for the implementation, management, and monitoring of the occupational health and safety standards is critical in scaling down the incidence of occupational hazards (Annan et al., Citation2015) in the informal sector including those in the bakery industry. Such collaborations are useful in strengthening the capacity of employers to implement, monitor and evaluate occupational health and safety standards. The study has both strengths and weaknesses that should be remarked upon. In the first place, this is one of the first studies in Ghana to have examined the perceived exposure to occupational hazards among bakers and their strategies employed against their exposure to occupational hazards. Specifically, this study has advanced knowledge in relation to exposure to occupational hazards among the participants and their coping strategies. The study has revealed that bakers are exposed to multiple occupational hazards, including biological, physical, ergonomic, chemical and psychosocial hazards. The causes of the exposure to the specific occupational hazards have been extensively discussed in this study. Again, the study has indicated that various specific strategies bakers have employed to contain their exposure to occupational hazards. These are an important contribution to the occupational hazards literature. The findings from this study have implications for informing appropriate policy and decision making to safeguard the health and safety as well as the quality of life of bakers in the Kumasi metropolis and Ghana at large. The findings suggest the need for formulation and implementation of occupational health and safety policies, procedures, acts and legislation to reduce the exposure of bakers to occupational hazards. This study is essential to contribute partly to the realisation of the Sustainable Development goal 8 and target 8.8, which seeks to protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers. The major limitations are that the authors could not get adequate literature to support the findings on the strategies employed against exposure to occupational hazards. This is because studies on coping strategies adopted by bakers to reduce their exposure to occupational hazards are scare. We encourage more studies to be conducted in Ghana and other low-and middle-income countries to validate our findings. Also, this study was purely descriptive and so could not establish a relationship and the association between the socio-economic and demographic characteristics of the respondents and their exposure to occupational hazards. To this end, we recommend that future studies should examine the contribution of demographic and socio-economic factors in explaining perceived exposure to different types of occupational hazards among bakers to inform policy direction. In addition, the scope of the study was limited to bakers in the Kumasi Metropolis of Ghana, however, the results still enrich the literature in occupational health field. Although, the study is a cross-section of bakers in the Kumasi Metropolis, the results need not be generalisable to the entire population of Ghana. Hence, it is worth stating such caveats to be considered by the readers when interpreting the results.

5. Conclusion

This study examined perceived exposure to occupational hazards among bakers and their strategies employed to control their exposure to occupational hazards. The study found that participants were exposed to different types of occupational hazards such as physical hazards (fire, noise, smoke/flour dust, and high temperature), chemical hazards, ergonomic hazards, psycho-social and biological hazards. We argue that frequent exposure to occupational hazards among the participants could undermine their quality of life and wellbeing. It was, however, revealed that the participants had employed different coping strategies to control their exposure to occupational hazards. One key finding was that each type of occupational hazard requires a different coping strategy. We suggest that there should be a participatory and action-oriented programme organised for bakers at weekly meetings to discuss topics on clear walkways, work posture, machine guards and safe handling of hazardous substances. Union executives should conduct a worksite inspection accompanied by a checklist to monitor the progress of the sessions held during meetings. International Organisations should serve as facilitators in strengthening local efforts to improve health and safety among bakers. Properly constructed preventive programmes will help reduce or eliminate occupational injuries and disease. The employees should avail themselves for training, obey all safety rules and regulations and use the appropriate PPE’s to protect themselves against occupational hazards, injuries, and diseases.

List of abbreviation

GDP- Gross Domestic Product

PPE- Personal Protective Equipment

SPSS- Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

ILO- International Labour Organisation

WHO- World Health Organization

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Williams Agyemang-Duah

Winifred Serwaa Bonsu holds MSc in Development Policy and Planning from the Department of Planning, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana. She obtained her first degree in the same department and institution. Her research interests mainly focus on occupational health and safety practices in the informal sector. This study is part of a larger project that explored occupational health and safety practices among bakers. The authors of this study jointly looked at the aspect of the larger project examined exposure to occupational hazards among bakers and their coping mechanisms in the Kumasi Metropolis of Ghana.

References

- Adei, D., & Kunfaa, E. Y. (2007). Occupational health and safety policy in the operations of the wood processing industry in Kumasi, Ghana. Journal of Science and Technology, 27(2), 159–19. DOI: 10.4314/just.v27i2.33052

- Aguwa, E. N., & Arinze-Onyia Sussan, U. (2014). Assessment of baking industries in a developing country: The common hazards, health challenges, control measures and association to asthma. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 15(20), 21–25. http://www.isca.in/MEDI_SCI/Archive/v2/i7/1.ISCA-IRJMedS-2014-034.php

- Agyemang-Duah, W., Owusu-Ansah, J. K., & Peprah, C. (2019). Factors influencing healthcare use among poor older females under the livelihood empowerment against poverty programme in Atwima Nwabiagya District, Ghana. BMC Research Notes, 12(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-019-4355-4

- Ahmed, A., Bilal, L., & Merghani, T. (2009). Effects of exposure to flour dust on respiratory symptoms and lung function of bakery workers: A case control study. Sudanese Journal of Public Health, 4(1), 210–213. https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20113037783

- Aluko, O. O., Adebayo, A. E., Adebisi, T. F., Ewegbemi, M. K., Abidoye, A. T., & Popoola, B. F. (2016). Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of occupational hazards and safety practices in Nigerian healthcare workers. BMC Research Notes, 9(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-016-1880-2

- Ametepeh, R. S. (2011). Occupational health and safety of the informal service sector in the Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolitan Area [Master’s thesis]. KNUST.

- Amosu, A. M., Degun, A. M., Atulomah, N. O. S., Olanrewju, M. F., & Aderibigbe, K. A. (2011). the level of knowledge regarding occupational hazards among nurses in Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria. Current Research Journal of Biological Sciences, 3(6), 586–590. https://www.airitilibrary.com/Publication/alDetailedMesh?docid=20410778-201111-201512280014-201512280014-586-590

- Amponsah-Tawiah, K., & Dartey-Baah, K. (2011). Occupational health and safety: Key issues and concerns in Ghana. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(14), 119–126. http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh/handle/123456789/4371

- Annan, J. S., Addai, E. K., & Tulashie, S. K. (2015). A call for action to improve occupational health and safety in Ghana and a critical look at the existing legal requirement and legislation. Safety and Health at Work, 6(2), 146–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2014.12.002

- Anozie, O. B., Lawani, L. O., Eze, J. N., Mamah, E. J., Onoh, R. C., Ogah, E. O., Umezurike, D. A., & Anozie, R. O. (2017). Knowledge, attitude and practice of healthcare managers to medical waste management and occupational safety practices: Findings from Southeast Nigeria. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research JCDR, 11(3), IC01–IC04. DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/24230.9527

- Arrandale, V., Meijster, T., & Pronk, A. (2013). Skin symptoms in bakery and auto body shop workers: Associations with exposure and respiratory symptoms. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 86(2), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-012-0760-x

- Asumeng, M., Asamani, L., Afful, J., & Agyemang, C. B. (2015). Occupational safety and health issues in Ghana: Strategies for improving employee safety and health at the workplace. International Journal of Business and Management Review, 3(9), 60–79. https://www.academia.edu/18695871/

- Avula, I. J., Stanley, O. N., & Samuel, N. K. (2015). Assessment of safety measures used by staff in bakeries in Yenagoa, Bayelsa State, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Health Sciences, 2(1), 7–15. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Assessment+of+safety+measures+used+by+staff+in+bakeries+in+Yenagoa%2C+Bayelsa+State%2C+Nigeria.+&btnG=

- Bhuiyan, M. S. I. (2016). Pattern of occupational skin diseases among construction workers in Dhaka city. Bangladesh Medical Journal, 44(1), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.3329/bmj.v44i1.26338

- Clarke, E. (2005). Do occupational health services really exist in Ghana? A special focus on the agricultural and informal sectors. WHO/ICOH/ILO Workshop: Challenges to occupational health services in the regions, the national and international response. Retrieved January 15, 2019, from http://www.ttl.fi/en/publications/Electronic_publications/Challenges_to_occupational_health_services/Documents/Ghana.pdf

- Commission on Health, Safety, and Workers’ Compensation. (2010). The whole worker: Guidelines for integrating occupational health and safety with workplace wellness programs. State of California Department of industrial relations. Retrieved January 18, 2019, from http://lohp.org/whole-worker/

- De Bruin, G. P., & Taylor, N. (2005). Development of the sources of work stress inventory. South African Journal of Psychology, 35(4), 748–765. https://doi.org/10.1177/008124630503500408

- Dillman, D. A. (2000). Mail and internet surveys: The tailored design method (2nd ed.). John Wiley.

- Doaa, M. A., Nagah, M. A., & Heba, M. S. (2017). Common health problems and safety measures among workers in traditional bakeries at Giza Governorate. Medical Journal of Cairo University, 85(3), 993–1001. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Doaa%2C+M.+A.%2C+Nagah%2C+M.+A.%2C+and+Heba+M.+S.+%282017%29.+Common+health+problems+and+safety+measures+among+workers+in+traditional+bakeries+at+Giza+Governorate.+Med.+J.+Cairo+Univ.+85+%283%29%3A+993-1001.+&btnG=

- Gajida, A. U., Ibrahim, U. M., Iliyasu, Z., Jalo, R. I., Chiroma, A. K., & Saidu, F. A. (2019). Knowledge of occupational hazards, and safety practices among butchers in Kano metropolis, Kano State, Nigeria. Pyramid Journal of Medicine, 2(2), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.4081/pjm.2019.41

- Gebrezgiabher, B. B., Tetemke, D., & Yetum, T. (2019). Awareness of occupational hazards and utilization of safety measures among welders in Aksum and Adwa towns, Tigray region, Ethiopia, 2013. Journal of Environmental and Public Health, 2019, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/4174085

- Ghamari, F., Mohammad, B. A., & Tajik, R. (2009). Ergonomic assessment of working postures in Arak bakery workers by the OWAS method. Journal of School of Public Health and Institute of Public Health Research, 7(1), 47–55. https://journals.tums.ac.ir/sjsph/browse.php?a_id=125&sid=1&slc_lang=en

- Ghana Statistical Service [GSS]. (2014). 2010 population and housing census: District analytical report, Kumasi Metropolitan. Ghana Statistical Service. Retrieved October 20, 2018.

- Greenlund, K., Liu, K., Knox, S., McCreath, H., Dyer, A., & Gardin, J. (1995). Psychosocial work characteristics and cardiovascular disease risk factors in young adults: The CARDIA study. Social Science & Medicine, 41(5), 717–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(94)00385-7

- Hall, J. (2008). Encyclopedia of survey research methods; Cross-sectional survey design. In P. J. Lavrakas Ed.. Retrieved February 20, 2019 from https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412963947.n120

- International Labour Organization. (2005). Facts on safety at work. International Labour Office.

- Joshua, A. I., Abubakar, I., Gobir, I., Nmadu, G., Igboanusi, J. C. C., Onoja-Alexander, M., Adiri, F., Bot, T. C., Joshua, W., & Shehu, A. (2017). Knowledge of occupational hazards and use of preventive measures among bakery workers in Kaduna north local government area, Kaduna State, Nigeria. Archives of Medicine and Surgery, 2(2), 78. doi:10.4103/archms.archms_39_17

- Kumar, C. R., Verma, K. C., & Neetika, A. (2016). An assessment of the knowledge, attitudes and practices about the prevention of occupational hazards and utilization of safety measures among meat workers in a city of Haryana state of India. Indian Journal of Applied Research, 6(3), 40–48. https://www.worldwidejournals.com/indian-journal-of-applied-research-(IJAR)/fileview/March_2016_149208227

- Levin, K. A. (2006). Study design III: Cross-sectional studies. Evidence-based Dentistry, 7(1), 24–25. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400375

- Machida, S. (2010). Strategic approach to occupational safety and health. A presentation at the 5th China international forum on work safety, Beijing. August 31–September 2. Geneva: Safe Work & ILO.

- Mellor, N., & Webster, J. (2013). Enablers and challenges in implementing a comprehensive workplace health and well-being approach. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 6(2), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-08-2011-0018

- Ministry of Employment and Labour Relations. (2016). 2016 statistical report. Author.

- Okafoagu, N. C., Oche, M., Awosan, K. J., Abdulmulmuni, H. B., Gana, G. J., Ango, J. T., & Raji, I. (2017). Determinants of knowledge and safety practices of occupational hazards of textile dye workers in Sokoto, Nigeria: A descriptive analytic study. Journal of Public Health in Africa, 8(1), 49–53. https://doi.org/10.4081/jphia.2017.664

- Oslen, C., & George, D. M. (2004) Cross-sectional study design and data analysis under the young epidemiology scholars program (YES) supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and administered by the College Board. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Retrieved March 15, 2020, from http://yes-competition.org/media.collegeboard.com/digitalServices/pdf/yes/4297_MODULE_05.pdf

- Po, J. Y. T., FitzGerald, J. M., & Carlsten, C. (2011). Respiratory disease associated with solid biomass fuel exposure in rural women and children: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PubMed, 66(3), 232–239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.2010.147884

- Rushtan, L. (2007). Occupational causes of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases. Reviews on Environmental Health, 22(3), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1515/REVEH.2007.22.3.195

- Sabitu, K., Iliyasu, Z., & Dauda, M. M. (2009). Awareness of occupational hazards and utilization of safety measures among welders in Kaduna metropolis, Northern Nigeria. Annals of African Medicine, 8(1), 46–51. https://doi.org/10.4103/1596-3519.55764

- Shezi, B., Naidoo, N. N., Muttoo, S., Mathee, A., Alfers, L. & Dobson, R. (2019). Informal-sector occupational hazards: an observational workplace assessment of the traditional medicine trade in South Africa. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 1 – 8. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2019

- Smoke, H. W. (2012). How wood smoke harms your health. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved May 8, 2019, from https://fortress.wa.gov/ecy/publications/publications/91br023.pdf

- Stoia, M., & Oancea, S. (2008). Occupational risk assessment in a bakery unit from the district of Sibiu. Research Paper. Acta Universitatis Cibiniensis Series E: Food Technology, Xii(2), 11–17.

- Takala, J., Hämäläinen, P., Saarela, K. L., Yun, L. Y., Manickam, K., Jin, T. W., & Lin, G. S. (2014). Global estimates of the burden of injury and illness at work in 2012. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 11(5), 326–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/15459624.2013.863131

- Üstun, T. B., Chatterji, S., Mechbal, A., & Murray, C. (2005). Quality assurance in surveys: Standards, guidelines and procedures. Household Sample Surveys in Developing and Transition Countries, 199–230.

- Wachira, W. B. (2016). Status of occupational safety and health in flour milling companies in Nairobi, Kenya [Unpublished M.Sc, Occupational Safety and Health]. Special Study Submitted to the Department of Occupational Safety and Health, Jomo Kenyata University of Agriculture and Technology.

- World Health Organization [WHO]. (1994). Global strategy on occupational health for all, the way to health at work. World Health Organization. Retrieved August 18, 2018, from www.who.org

- World Health Organization [WHO]. (2006). Declaration of workers health. WHO collaborating centres of occupational health.

- World Health Organization [WHO]. (2013). Declaration on occupational health for all. WHO.

- Yossif, H. A., & Abd Elaal, E. M. (2012). Occupational hazards: Prevention of health problems among bakery workers in Benha City. Journal of American Science, 8(3), 99–108. doi: 10.7537/marsjas080312.11