Abstract

Abstract: Media reports of difficulties with post-career functioning and death in ex-professional hockey enforcers have led to concerns within the ice hockey community. The purpose of the study was to interview 10 ex-professional ice hockey enforcers and integrate their lived experiences into the narrative on post-retirement problems experienced by these athletes. Based on the existing literature, it was hypothesised that ex-professional hockey enforcers would be at high risk for development of symptomology consistent with Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). A mixed methods analytical approach informed by Pragmatic and Indigenous methodologies was employed. Participants had a significant history of fighting in their sport (range 100–250; mean = 218.5). All had significant concussion histories related to their careers in hockey. One participant reported problems post-career associated with concussions sustained while playing hockey. Five participants reported issues with chronic pain that mildly impacted their sleep and/or daily functioning. The majority reported relatively good post-career functioning. In summary, the hypothesis that ex-professional hockey enforcers are at high risk for developing symptomology consistent with CTE was not supported. The pattern of results is in opposition to the commonly held perspective that fighting in hockey leads to a cascade of events that results in poor post-career outcome.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Concussion in sport has become a major concern internationally. In Canada, there have been several high-profile cases of ex-professional ice hockey enforcers dying prematurely due to suicide and accidental death including drug overdose. Some have speculated that the deaths are related to fighting in ice hockey – the primary role of an enforcer. This study interviewed 10 ex-professional ice hockey enforcers in an effort to learn whether they are experiencing negative outcomes following retirement from the sport. All participants had a history of multiple concussions. Only one participant reported cognitive or emotional problems post-career that in his opinion were associated with concussions sustained while playing hockey. Five participants reported issues with chronic pain that mildly impacted their sleep and/or daily functioning. The majority of participants reported relatively good post-career functioning. In summary, the perspective that ex-professional hockey enforcers are at high risk for cognitive and/or emotional problems post-career was not supported.

1. Introduction

On 31 August 2011 National Post columnist Bruce Arthur began his column with: “What a summer. What a wretched summer.” (National Post 31 August 2011). What Arthur was referring to were the deaths of three National Hockey League (NHL) enforcersFootnote1 by suicide or accidental death including overdose. This article can be considered the symbolic origin of a scientifically informed perspective in the North American media. The perspective in question is that hockey enforcers may be particularly susceptible to negative consequences of neurotrauma in sport due to the cumulative exposure to concussive and sub-concussive events that occur in hockey generally and the role of enforcer specifically.

The narrative that has developed in media reports is rooted in the science of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). Specifically, there has been speculation that the deaths of ex-professional hockey enforcers have been linked to CTE (e.g., Arthur, Citation2011; Blakemore, Citation2016; Fitz-Gerald, Citation2015; Larsen, Citation2017; Pollock, Citation2019; Strong, Citation2019; Westhead, Citation2017). This position is supported by past studies on suicide and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in athletes (e.g., Azad et al., Citation2016; Omalu et al., Citation2010; Omalu et al., Citation2011) and studies on suicide in the general population (e.g., Fralick et al., Citation2016; Madsen et al., Citation2018). Headlines such as “List of NHL enforcers who have passed away gets longer” (Fitz-Gerald, Citation2015) have led the public to anticipate the “next case”. These media reports are relevant because they are often the final stage of knowledge translation that informs the public. As such, it can be argued that there is a “disconnect” between the state of science on the long-term effects of sport-concussion and what is being portrayed in the media (Burley, Citation2020; Riley, Citation2016). There may also be an incongruence between this media-driven narrative and the lived experiences of ex-professional hockey enforcers.

CTE has been described as a neuropathologically distinct progressive tauopathy with a clear environmental aetiology (McKee et al., Citation2009) and is the only known neurodegenerative dementia with a specific identifiable cause—head trauma (Gavett, Stern, and McKee 2011). Two primary clinical variants of CTE have been described. Younger people may experience more behavioural and/or mood symptoms with older persons exhibiting cognitive and motor impairment similar to dementia (Davis et al., Citation2015; Huber et al., Citation2016; Bailes et al., Citation2015; Bieniek et al., Citation2015; Stern et al., Citation2013). The causes of CTE vary by study with some stating that a single blunt force episode may be sufficient (Omalu et al., Citation2011) with others stating that CTE develops following repetitive concussive or sub-concussive events (Armstrong et al., Citation2016; Omalu et al., Citation2010; Edwards et al., Citation2017; Huber et al., Citation2016; Lesman-Segeva et al., Citation2019; McKee, Abdolmohammadi et al., Citation2018; McKee, Stein et al., Citation2018; Stern et al., Citation2011; Tsai, Citation2020; VanItallie, Citation2019) or both (Bailes et al., Citation2019). Limited prevalence data suggest that CTE has been observed in 9% of autopsy cases with a history sport participation versus 3% of those with no history of participation in sport (Bieniek et al., Citation2020). Modern-day CTE symptomology has evolved since it was first discussed by Omalu et al. (Citation2005). More recently, CTE symptomology has been categorized into four classifications: cognition, behaviour, mood, and motor symptoms (Huber et al., Citation2016; Bailes et al., Citation2015; Montenigro et al., Citation2015). Suicide has been discussed as “clinically associated” with CTE (McKee et al., Citation2012), over-represented in CTE cases (Omalu et al., Citation2011), not uncommon (Stern et al., Citation2011), with the heightened suicidal risk in stark contrast to other tauopathies (Bailes et al., Citation2015; VanItallie, Citation2019). The link between CTE and suicide has been described for professional athletes (Azad et al., Citation2016). Recently, concussion has also been linked to suicide (Montenigro et al., Citation2015).

The scientific literature stating that single or repetitive concussive and sub-concussive blows lead to the development of CTE pathology and symptomology has led to substantial concern in the sporting and medical communities. The Athlete Post-Career Adjustment (AP-CA) model (Gaetz, Citation2017) was developed to help to understand post-career functioning of athletes beyond the consequences of concussion. The AP-CA model states that four factors may be related to significant negative outcomes following retirement from contact sport: neurotrauma, chronic pain, substance use, and career transition stress. In addition, depression can be a chronic lifelong co-morbid condition that may be present prior to an athletic career, or may be developed secondary to any of the model elements (Gaetz, Citation2017). The purpose of this study is to utilise the AP-CA framework to explore the lived experiences of ex-professional hockey enforcers regarding the problems they may experience post-retirement regarding chronic pain and cognitive functioning.

Based on the CTE literature, it was hypothesised that ex-professional ice hockey enforcers would be at high risk for developing symptomology consistent with a history of neurotrauma given the dose response relation between exposure to traumatic forces and the development of CTE (Mez et al., Citation2020). In addition, it was also anticipated that participants would describe substantial issues with chronic pain associated with their role in the sport and that this too could impact symptomology (Gaetz, Citation2017). The current study is guided by empirical data as per Deweyan pragmatism (Hall, Citation2013) and Indigenous methodologies (Kovach et al., Citation2014). A 15-item semi-structured in person interview format was utilised with questions intended to elicit conversation with ex-professional hockey enforcers regarding their experiences with neurotrauma, physical injury, chronic pain, and their post-career functioning. The purpose of this study was first to establish the nature and frequency of brain and physical injury that occurred during the participant’s career via the development of descriptive themes within the categories Concussion, Physical Injury, Chronic Pain, and Post-career functioning (). Finally, interpretive themes based on injury characteristics and post-career functioning were developed based on the descriptive theme content (Bryman, Citation2006). The overall goal of the study was to allow participants to inform the discussion regarding how concussions and physical injury have affected them following a career as a professional hockey enforcer based on their lived experiences.

Table 1. Thematic organisation based on injury history and post-career functioning categories as well as descriptive and interpretive themes

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Methodology and philosophical underpinnings

The study employed two forms of mixed methodologies. One of the mixed methodology approaches has been described as “two-eyed seeing”. Two-eyed seeing is a methodologic framework intended to approach science through a Western lens as well as through the lens of Indigenous knowledge (Martin, Citation2012). The main premise behind two-eyed seeing is that by acknowledging and respecting Western and Indigenous perspectives, we can develop a new way of understanding that respects the differences that each can offer (Botha, Citation2011; Chilisa & Tsheko, Citation2014; Martin, Citation2012; Richardson, Citation2015; Sanchez et al., Citation2019). The current study also utilised a quantitative and qualitative mixed methods approach (Bryman, Citation2006, Citation2007; Fetters et al., Citation2013; Hesse-Biber, Citation2010; Hesse-Biber & Burke Johnson, Citation2015; Norwich, Citation2020). The philosophical underpinning of mixed methods in this sense aligns with Deweyan pragmatism (Burke et al., Citation2017; Feilzer, Citation2010; Hall, Citation2013; Norwich, Citation2020). Therefore, in this study, the “Western” lens utilises both Deweyan pragmatism and quantitative methods while the “Indigenous” lens utilises an Indigenous qualitative approach that is secondarily informed by feminist constructs based within a relational epistemology (Bird-David, Citation1999; Brownlee & Berthelsen, Citation2008; Causadias et al., Citation2018; Chilisa & Tsheko, Citation2014; Elliot-Groves, Citation2019; Held, Citation2019; Kawagley, Citation1993; Kovach et al., Citation2014; Marin, Medin, and Ojalehto, Citation2017; Martin, Citation2012; Sanchez et al., Citation2019; Sonn & Quayle, Citation2012). Embedded within relational epistemology is a highly developed sense of social consciousness characterized by the responsibilities inherent in each relationship (Kawagley, Citation1993) with knowledge distributed through collective human networks (Held, Citation2019) by story and narrative (Richardson, Citation2015).

Deweyan pragmatism (DP) has been simplified by some as a “whatever works best” approach; however, it shares a number of philosophical elements with Indigenous methodologies (IM). For example, both DP and IM state that intuition is central to the process of inquiry (Botha, Citation2011; Burke et al., Citation2017; Kawagley, Citation1993; Richardson, Citation2015). Both perspectives consider the ethics of the research to be of equal or greater importance than the requirements of a specific methodologic perspective (Cochran et al., Citation2008; Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2008; Hall, Citation2013; Weber-Pillwax, Citation2001). DP and IM value “story” or the shared history of people within their specific communities (Burke et al., Citation2017; d´Ishtar, Citation2005; Elliot-Groves, Citation2019; Hall, Citation2013; Kawagley, Citation1993; Kovach et al., Citation2014; Martin, Citation2012; Richardson, Citation2015). Both perspective value communication between the participant and researcher that is reflexive and reciprocal (Bird-David, Citation1999; Chilisa & Tsheko, Citation2014; d´Ishtar, Citation2005; Elliot-Groves, Citation2019; Martin, Citation2012; Richardson, Citation2015). Importantly, both perspectives are action oriented (Elliot-Groves, Citation2019; Hall, Citation2013; Kovach et al., Citation2014; Martin, Citation2012).

Finally, unlike some qualitative approaches that consider knowledge generated by the researcher at an equal or even greater level of prominence as the participant (Bell et al., Citation2017; Smith, Citation2011; Smith, Citation1996; Smith & Osbourne, Citation2009; Larkin et al., Citation2006; Smith et al., Citation1999), this study takes a “participant as expert approach” (Chilisa & Tsheko, Citation2014; Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2008; Dey et al., Citation2018; Hesse-Biber, Citation2010; Ingram et al., Citation2011). As Kovach et al. (Citation2014) states, in this type of research, the participants’ stories are the teachers. “Listening to hear” the unique and insightful perspectives of the participant rather than “listening to respond” was the guiding principle for communication during interviews (Chilisa & Tsheko, Citation2014; Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2008; Kovach et al., Citation2014). As such, the study employed a participant-centred approach that attempted to minimise the issues associated with researcher bias (Svenson et al., Citation2018; Wilson et al., Citation2020) and editorialisation with an attempt to maximise the opportunity for participants to accurately express their perspectives based on their lived experiences (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2008; Kovach et al., Citation2014; Martin, Citation2012; McGloin, Citation2015). The primary analytical role of the researcher then was to listen and then integrate and contextualise the participant’s experiences within the existing research literature.

2.2. Participants and researcher

A total of 15 ex-professional ice hockey enforcers were invited to participate in the study with 10 agreeing to participate in face-to-face interviews. Reasons provided for declining to be involved in the study included time constraints associated with the role of hockey scout, uncertainty about how involvement would impact their careers within professional hockey, or having a perceived conflict between the purpose of the study and a leadership role within a professional hockey alumni association. The participants represented a reasonably homogenous, purposive sample. Participant age ranged from 31 to 61 years (mean = 48.9). All participants were drafted into the National Hockey League (NHL). Seven participants played in the NHL with the remainder having careers in the American Hockey League (AHL) as their highest level of hockey played. The number of years as a professional hockey player ranged from four to 15 (mean = 10). The range in calendar years for careers in professional hockey was from 1978 to 2014. There were two Calder Cup champions (AHL Championship) and two Stanley Cup (NHL Championship) champions in the sample.

Hockey fights occurred in minor hockey, junior hockey, and professional hockey games and practices. Fights outside of hockey occurred with some participants but were not included in this study. The first hockey fight occurred between the ages of 10–18 years (mean = 15). Two participants had estimated approximately 100 career fights with six reporting over 200 career fights (range 100–250; mean = 218.5).

All participants were employed at the time of interview. Current participant occupations included firefighter, sales, upper management in a resource-based industry, founder of a non-profit organization following a number of years of coaching in professional hockey, owner operator of a number of successful businesses as well as being an NHL scout, a radio and television media broadcast personality for an NHL team, and being employed in professional hockey as a coach, general manager, or scout.

The author is a white settler born on the northern border of the traditional lands of the Blackfoot, Tsuu T’ina and Stoney Nakoda peoples, raised on the traditional lands of the Cree and Dakota Sioux people, and who currently lives and works on the traditional lands of the Stó:lō people. Each indigenous group has impacted the author’s value systems and ways of interacting with the world. The author has been studying concussion in hockey since the late 1990s and has published on the effects of concussion in sport as well as developing methods to explain the negative experiences that some athletes face post-retirement. He has extensive experience in ice hockey as a player, coach, and as a member of a sport science team within junior hockey in Canada. He shares a common cultural and geographical history with the participants and as such, was able to develop a good rapport based on a common cultural history and knowledge of the sport.

2.3. Procedure

This study is based on semi-structured interviews from 10 former professional ice hockey enforcers and is a part of a broader ongoing research project. In this study, a “hockey fight” was operationally defined as participation in a fight between two players where a five minute major penaltyFootnote2 was assessed to the participant for “fighting” during games. A fight during practice resembled a fight that occurred during games but with no penalty assessed. Both were included as hockey fights in this study. A “hockey enforcer” was operationally defined as a professional ice hockey player who’s role on the team included bareknuckle fighting in a hockey game or practice, was recognized by other enforcers as someone who had this role, and had a minimum of 100 fights total in amateur and professional hockey. A “professional” was defined as a player who had signed a professional contract with a hockey organisation and had played professionally for at least one season. Convenience sampling was initially used with snowball sampling utilised once the contact information of hockey enforcers who were willing to participate in the study was provided. The ethics of the research were reviewed and approved by the University Human Research Ethics Board.

The interview guide was developed to elicit conversation that encompassed the issues surrounding concussions in hockey as well as other factors that may affect post-career functioning (Gaetz, Citation2017). The semi-structured interview was composed of 15 questions as well as follow-up prompts. In an effort to hear the stories, a reflexive conversational approach was employed (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2008; Kovach et al., Citation2014). The interview was premised with a general statement that the purpose of the study was to allow participants to provide their perspective about their role in ice hockey and the potential negative outcomes that they have heard about in the media and biographical accounts. This signalled to the participants that they were in a position of expertise and power regarding the eventual results. In other words, an ethical position was established that shifted focus to the participant (d´Ishtar, Citation2005; Kovach et al., Citation2014). One-on-one interviews were conducted face-to-face at a location mutually agreed upon by the participant and researcher. The locations of the interviews included five Canadian provinces and two states within the United States. The duration of the interviews was between 25 and 99 minutes (mean = 60.9). The consent process occurred immediately prior to the interview and included a review of the consent letter, an opportunity for questions and clarification, followed by written consent. It was stressed that the information provided would be treated in a confidential manner and that any content that would link a response to a specific participant would be anonymised. A copy of the consent form was provided for participants.

Each interview was audio-recorded using both a Panasonic RR-US551 recorder and a Samsung Galaxy 4 smartphone. Digital audio files were deleted from the primary devices once transferred to the password encrypted personal computer of the researcher. The digital audio files were transcribed verbatim by the researcher or a student research assistant. Once transcription for each file was complete, the transcripts were sent to the personal email of the participants for review and editing if necessary. This “member checking” has been criticised as an index of rigor (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018). Nonetheless, it was utilised to ensure that the ethical responsibilities of the researcher were met (Parr, Citation2015) by ensuring that participants could be confident that their responses were those intended and that they were allowed the time to reflect and change their comments as required. When changes were requested, the transcript was edited and sent back to the participant for review and approval prior to analysis. Once the transcript was approved, the digital audio file was deleted. Non-descriptive labels were used for each participant (e.g., P1). Player, city, and team names were anonymised (e.g., NHL City).

2.4. Data analysis

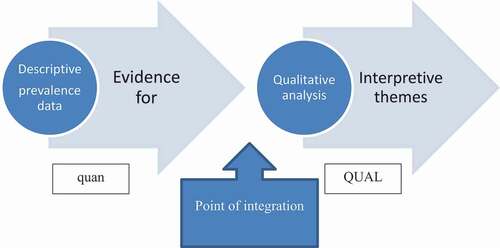

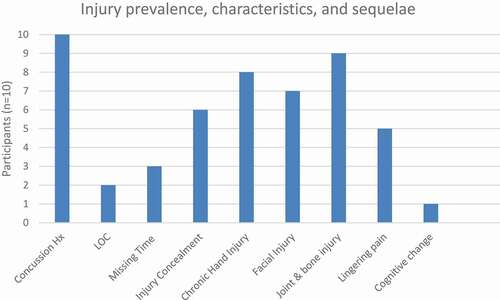

Mixed method research has been recognized by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) as effective for the comprehensive understanding of health issues (NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences, Citation2018). The strategy for the use of mixed methods in this study was to initially quantify the nature and frequency of the injuries (—Descriptive Themes) sustained by participants during their careers within the empirically derived primary categories “Concussion” and “Physical Injury” (). This quantitative analysis transformed qualitative responses from interview transcripts into variables describing injury characteristics and frequency shown in (Fetters et al., Citation2013). Providing injury history was necessary to establish the bases for potential for problems within the primary categories “Chronic Pain” and Post-career Functioning” (). Therefore, the descriptive themes provided a contextual basis for the qualitative thematic development to follow (Bryman, Citation2006).

Figure 1. Frequency of injury, injury characteristics, sequelae, and pain (Hx = history; LOC = loss of consciousness)

Qualitative analysis involved the development of interpretive themes based on the descriptive themes (; ). The thematic development was informed by Indigenous methodologies with a focus on recurring concepts within the conversations guided by relational epistemology (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2008; Kovach et al., Citation2014) as described in section 2.1. The method used for thematic analysis was that of Braun et al. (Citation2016). This form of thematic analysis allows the researcher to identify and interpret patterns of responses independent from a specific ontological and epistemological framework. The process of thematic development adhered to the prescribed steps of Familiarization, Coding, Theme development, Refinement and Naming (Braun et al., Citation2016). The development of descriptive quantitative themes followed by more substantial interpretive themes is consistent with an explanatory sequential design where the qualitative component is employed to try to explain or contextualize the earlier quantitative results (Creswell, Citation2015; Creswell et al., Citation2007; Fetters et al., Citation2013; Hesse-Biber, Citation2010; Hesse-Biber & Burke Johnson, Citation2015). Integration of the transformed quantitative data with the interpretive qualitative themes are indicated in .

2.5. Research quality and methodological rigor

The research was conducted as per NIH best practices for mixed methods research in health sciences (NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences, Citation2018). Operational definitions are provided as well a clear hypothesis. Consistent with DP and IM, there was a continuous reflection on how the results could impact lives of people via consequential validity (Burke et al., Citation2017; Hall, Citation2013; Kovach et al., Citation2014). Rigor as per Braun et al. (Citation2016) was demonstrated in multiple ways. The number of participants exceeded the suggested minimum sample size of six and utilised the 15-point “checklist” for a good thematic analysis. The study incorporated Yardley’s (Citation2000) suggestions for good quality qualitative research including in-depth coverage of the relevant literature, having a theoretical basis (Gaetz, Citation2017), transparency in methods, and having an impact to theory and impact for those involved in contact sport. Finally, consistent with Smith and McGannon (Citation2018) member checking was utilised as a part of ethical practice, but not as an index of rigor. Issues with interrater reliability were avoided during the interview or coding process because all work was completed by the author. The concept of “critical friends” was employed while acknowledging that the ultimate critical friends are peer-reviewers embedded within all peer-reviewed science (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018).

3. Results

3.1. Concussion

Descriptive prevalence categories and themes are presented in . The descriptive themes that emerged under the category “Concussion” were Concussion history, Loss of consciousness, and Missing time. The interpretive theme for this category was “Injury concealment and threat to employment”. The frequency of descriptive theme occurrence for participants is shown in .

3.1.1. Concussion history

Participants reported an average of 1.5 (range = 0–5) medically diagnosed concussions defined as a team physician or trainer identifying a concussion and subsequently removing from the participant from that game or practice. When asked to estimate how many concussions they actually experienced, participants reported an average of 5.9 (range = 2–15). When asked to estimate how many of the concussions were related specifically to fighting, participants reported an average of 2.45 (range = 0–5).

3.1.2. Loss of consciousness

Two participants commented on the loss of consciousness related to concussions they experienced. One stated that during practice he accidentally collided with a team mate—“ … planted my face, like hit my chin right on his shoulder pad … and like I literally woke up … and the whole team was standing around me on the ice, like are you OK, are you OK?” (P4). He also mentioned a number of “flash knock-outs” that were associated with fighting: “you know after five minutes in the box you come out and you feel like you’re OK” (P4). Another participant reported loss of consciousness associated with a serious motor vehicle accident. Four participants stated that they were never “knocked out” during a fight with a single opponent. One discussed the added danger of fighting in a hockey brawl (multiple combatants fighting on the ice at the same time). He noted that: “ … those are where you, you can get knocked out … it’s a war and half of them are just happy to be holding onto each other. The other half aren’t … they got axes to grind and here is their chance”. (P7).

3.1.3. Missing time

Three participants experienced concussions of sufficient severity to disrupt memory for portions of a game they played in. P2 stated “I got into a fight, I think I took a few, pretty heavy shots, and … went to the penalty box. And after the game I, uh, the whole second period I don’t remember.” P4 mentioned multiple occasions where he played in a “fog”. On one occasion, he described:

“ … another time, NHL player frickin” elbowed me coming around the net one night in NHL city and we were down 3–1 going into the third period and I’m on the bench and all of a sudden I look up at the clock and it’s like, 4–1 and I was like ooh when did they score the 4th goal … ? … and have I been playing? And it’s like oh ya you’ve been playing … ’ (P4).

Another participant also relayed a story about how a concussion caused him to have no memory for an entire period of hockey:

“And so I have this fight. Uh, the period ends, I go in, I’m sitting there and I got my stuff off and he’s doing it (trainer checking his hands after a fight during a period break), and it was almost like a (finger snap) poof, and there I had my shoulder pads on. … and I don’t remember putting them on” (P10).

3.1.4. Interpretive theme:” Injury concealment and threat to employment

Six of the participants described intentionally concealing concussion symptoms in order to continue playing during that game or future games. In other words, they masked an injury that could be worsened or have a longer term impact on their health. In the previous scenario described by P10, the trainer understood what was happening and asked some important questions:

“ … he was a smart, really good trainer, smart guy, and he picked up on it … and he’s like, uh what’s the score? I’m like fuck off. Don’t fuck with me. He goes what’s the score? I didn’t know the score. He goes which period is it? I go fuck-off, we’re getting ready for the second. I had come in, did my hands, went out, played an entire period … got in another fight … never got hit in the fight, I went back and watched it. I played an entire period that to this day I don’t remember”(P10).

The quote is informative from a variety of perspectives. First, the participant clearly intended to continue participation despite being injured. Second, it indicates that a significant concussion had occurred prior to this event given that the participant had no memory of a large portion of the game. Third, it demonstrates that there were trainers who knew when to remove players from play when concussed. This suggests that there was knowledge available to team trainers and medical staff about the potential for long-term issues associated with concussion however not all trainers had this information or worked in an environment that allowed for its implementation. Fortunately, once he had the information he needed, the trainer took the necessary steps to ensure the player’s safety:

‘Um, he was good, he goes you know what, you can take your shit off, you’re not playing. I said I’m not taking my stuff off. He goes well that’s fine, I’m going to tell NHL coach your hand’s fucked, you’re not playing. I never had a shift the rest of the game. He wouldn’t let me play’ (P10).

This portion of the story reveals that at that time, concussion was not seen by all team personnel as a legitimate injury. The trainer had to utilise an “acceptable injury” (hand injury following a fight) to remove the player from a game. He presumably did this to protect the player from the consequences of leaving a game due to concussion or perhaps protect himself from scrutiny over a decision to remove a player for that reason.

Unfortunately, most of the time, the player was successful in his attempt to mask symptoms. P2 stated “I can think back to maybe a couple of times where I look back and OK, that’s symptoms there, but, nothing was said or the trainers didn’t do anything.” P3 added “ … you know he hit me in the head, he hit me in the skull … I was, concussed and I wanted to keep playing (and did).” Players from an earlier era reported that playing through concussion symptoms was expected: “Ya, you got your bell rung. We just looked at it, you got your bell rung. But they still played you” (P9) and “it was like tape an aspirin to it (laughs) … and get back out there” (P8). One participant disclosed going to great lengths to conceal substantial symptoms from coaches and team medical staff. Following loss of consciousness he experienced following a collision during practice, P4 described the following:

‘ … the first thing that came to my mind was that I’m not missing these two games (laughs) … because I’m going to have friends and family and everybody here … I’m not missing these games. And so, you know the trainer’s telling me that I’ve got to get off the ice, and (I’m) like no I’m OK … and go to the bench … and all of a sudden I get like, you know when somebody takes you picture with the old flashbulb? … and you get that black spot? … well I had this black spot … and it’s like I’m sitting there and it won’t go away. I kind of finished the practice by, you know, kind of just making my way through it … . I made sure I stayed on the ice a little bit longer … and it was like a big black, almost like a, almost like the size of a puck’ (P4).

This quote is revealing for a number of reasons. It clearly shows that the desire to play in the games was due to the location of the games and that family members would be present. However, it does not rule out the motivation to play through injury due to a warrior mentality, commitment to team mates, or concern over job security. It also indicates the magnitude of the injury and the potentially serious neurological injury that some participants were willing to play through.

A subtheme that emerged regarding playing through concussion was a threat to employment. Three participants clearly expressed playing through concussions due to concerns about losing their job. For example, “not saying anything (about being concussed) because I was starting to play … and wanting to stay in the line-up” (P2) or “ … if I had a concussion and was going to miss whatever like … I might lose my job and I might end up getting sent to the minors’ (P4). Finally, P10 concisely described the concern: ‘”You know what, you got a concussion? You can’t play? That’s fine. I got someone in the minors that can.” And that’s basically what it was. You’re going to lose your job’ (P10). These comments clearly indicate that concussion was not considered a legitimate injury by some team personnel. Participants were motivated by perceived threat to employment to continue to play while injured. However, this was not limited to concussion.

3.2. Physical injury

Descriptive themes within this category included injuries to the hands, face/head (not concussion), and joints as well as the perception of pain associated with each injury. Post-career pain relief was noted as well as current levels of chronic pain ().

3.2.1. Chronic hand injury

As one would expect, the hands and face are two regions of the body that are susceptible to injury when fighting. Eight participants described injury to their hands that caused significant pain during the hockey season. For example, P2 stated that “I was fighting every other night because I wanted to … re-sign, and my hand, it would hurt to turn the faucet on. It is like my hand would be a balloon, and I would just keep doing it (fighting) … I really didn’t like the way my hands my hands would feel” (P2). P7 continued that “All the cuts and that, like I said your hands are always sore. The other guys will say that too. They are just always sore. People would look at them in a restaurant and, you know, there is a hole where a tooth cut you.” (P7). Of course, a hand injury caused by an opponent’s tooth could cause secondary injury due to infection: “When I was in junior I’d got in a fight and I, I cut my hand on a guy’s teeth. A couple days later my hand’s swelling up. I did like 10 days in the … hospital because I had an infection” (P10). In addition to cuts, two participants noted fractures to bones in the hand that occurred during fights. One recalled a significant injury to a finger caused by a laceration from a skate. In addition to blunt force trauma, hand injuries such as sprains could occur to the wrist, thumb, or other digits during fights. P3 described “I always generally just threw with my rights because I didn’t know how to throw with a left that well or anything so it (his thumb) would get caught … and bent over so I know in the minors … it would be way over here and I’d have to tape it back over” (P3). The constant state of physical pain the hand injuries caused was difficult to manage and caused some participants to question their role within the sport. For example, as his career came to a close, P6 recalled thinking:

“Again, it’s not sustainable you know what I mean? It’s like, again the injuries accumulate and you’re always playing with a finger, a wrist, or you know, just like, again that’s when the next day … or that night kind of kicks in and ‘what am I doing?’ … you know what I mean?” (P6).

3.2.2. Facial injury

General injuries to the face and head (non-concussion) were reported by seven participants. Those related to fighting ranged from general complaints such as lacerations that required stitches and general head pain (not headache), to more substantial injuries. Lost teeth were reported by two participants. For example, P8 recalled: “he had cranked me one really good one here and in fact I got stiches but it didn’t bother me … Frigging looked like a camel after the game” (P8). Broken facial bones were reported by three participants with one stating he had fractures to the nose, “cheekbone”, and jaw, all caused by different on ice events. Lost fights could result in substantial facial trauma: “He annihilated me. He absolutely kicked the living daylights out of me. Broke my nose, I wouldn’t go down and he just kept beating me” (P9). Two participants sustained facial injuries unrelated to fighting. One experienced an eye injury with vision loss related to being hit by a puck. The other was in a serious car accident that resulted in loss of consciousness and facial lacerations.

3.2.3. Other joint and bone injury

Joint injuries and fractures were reported by nine participants. Joint injuries included those to the shoulder (four participants), knee (two participants), spine (two participants) and a high ankle sprain in one participant that caused a lingering susceptibility to injury. Fractures occurred in six participants due to blocking shots, e.g., ‘I never had a bone that was displaced … like I had, a couple cracked bones in my feet … getting hit by shots’ (P5), stick induced trauma to the wrist (two participants), and a C5-6 vertebral fracture that occurred in a motor vehicle accident. Playing through substantial injury to bodily regions other than the hands was noted by a number of participants. For example, P8 described his ankle bending:

‘right back over, I played the rest of the game, it was frigging hurting like I am telling you … frigging hurting like a bastard but back then, the medical staff was taping aspirin to it, you know “don’t take your skate off”. Ya well after the game, a bucket and ice on the way back and next day I am in a frigging cast’ (P8).

Cortisone and anti-inflammatory injections were noted by two participants as well as various prescription opioids for pain management.’

Four participants mentioned surgical interventions to correct injuries sustained during career. The surgeries included inserting a metal plate into a broken finger, knee surgeries, a hip replacement, removal of herniated intervertebral discs, and reconstructive shoulder surgeries.

3.2.4. Lack of injury

A surprising number of participants reported low levels of specific types of injury that would be expected given their role. A participant with a minimum of 250 fights reported ‘I never got cut ever. I’ve never had a stitch in my face (laughs) … no issues’ (P3). Another reported never experiencing a headache. Given the degree of hand trauma experienced, it may be expected that arthritis might plague participants during retirement; however, this was not frequently reported. As stated by P7, “My hands you know what, I kept waiting for arthritis to kick in. Because like I said hundreds of fights, you’re just wondering when it’s going to happen. But god bless no … they don’t (hurt)”. Another participant stated “I didn’t get hurt, I never got hurt in a fight. Never got hurt bad, never … ” (P8).

3.3. Chronic pain

Descriptive themes included acute post-career pain reduction and lingering post-career pain ().

3.3.1. Acute post-career pain reduction

Three participants reported perceived post-career pain relief. Surgery was one of the stated reasons for pain reduction. P4 noted that “before I had my hip done I used to, used to really you know, live on Ibuprofen. It was like … a bad toothache, all the time … I’d walk cutting my grass and for two days … I couldn’t walk … ” (P4). There was a notable reduction in chronic pain shortly following the surgery: “it was amazing like, when I woke up from the surgery like it was painful but it was like, the toothache’s gone” (P4). Other stated reasons for pain reduction included lifestyle changes including diet and exercise such as yoga. Finally, simply not playing hockey was a reason for notable pain reduction: “You didn’t realize the effect of it till a couple weeks after the season and now all of a sudden your hands are in … no discomfort” (P7).

3.3.2. Lingering post-career pain

Half of the participants reported post-career pain that affected their daily functioning via loss of mobility, pain, or sleep loss. Three participants reported shoulder injury as a source of pain, with two reporting that it affected sleep. For example: “I’m reminded daily of you know my shoulders, like I mean I always had shoulder problems when I played and a bunch of injuries with my shoulders and like I said I’ve had four shoulder surgeries since I’ve retired … ” (P4). Two participants reported wrist injuries that continued to cause pain post-career. Other sources of bodily pain included hand arthritis, knee pain, and back pain. One participant reported migraine that he felt was directly related to concussions sustained in hockey: “obviously the migraines I would have to say are 100% … related to my getting punched in the head a lot” (P1).

The other half of participants reported relatively low levels of pain. The participant with a plate in his finger stated “It’s not ever painful, it’s just, you can, it just looks, looks a little funny and uh, when it’s cold and damp winters it gets a little cold” (P2). Another reported “I’m 60 years old, 61 so it just maybe comes with it but no I could go out and walk the (golf) course with you right now or go ride a bike with you and no I’m not aching, hurting and stuff” (P3). Two participants reported very little pain at all. For example, “I don’t know, I’ve pretty good lines as far as my folks … we’re pretty healthy people. So I was lucky that way. So no, not a lot of pain” (P5).

3.4. Post-career functioning

Descriptive themes included current employment, the presence or absence of cognitive/emotional change, current levels of substance use, and general perceptions of health (). An interpretive theme ‘We got it wrong—“Don’t do that” also emerged relative to the descriptive themes.

3.4.1. Current employment

As stated earlier, all participants were employed at the time of interview. It may come as a surprise to learn that ex-professional hockey athletes had to continue to work following their careers, but this was generally understood by most participants. The salaries for players in the league were relatively low prior to the mid-1990s and enforcers were at the lower end of the professional ice hockey pay scale. No participant reported problems with physical or cognitive-emotional functioning that impacted their ability to work. Most were employed in vocations that had substantial cognitive demands. Most reported being happy and fulfilled in their current employment. Most had positions as coaches, scouts, media personalities and management within professional hockey all of which require high-level cognitive functions such as the ability to evaluate, plan, organize, and strategize. Working within professional hockey is also a taxing career due to the travel and long hours that are required to be successful. Regarding his professional life post-career, P7 offered: “Yeah I have had a good career, I mean I have been vice-president of several resource-based companies, sold them became well off because of it”. Another participant stated “ … I’ve built a hell of a good business. Two businesses, in fact I had more than two because I’ve sold a few” (P8).

3.4.2. Cognitive changes

Three participants commented on cognitive functioning post-career. P7 was mildly concerned with perceived memory loss. He described his concerns as follows:

‘I have trouble only in the morning sometimes, just in the mornings … with … names, or I look at a tree and go like I should know what that tree is called. Like yesterday I was doing that. It was a Mountain Ash and you think I could, it took me five minutes to clue that in, so did that come from hockey … ?’ (P7).

He continued: “now you’re 40 years out of the game, maybe these chickens are coming home to roost. Hard to say, I don’t think it helps to have had any brain trauma, when you have already got that (dementia) in your family” (P7). Two other participants commented on their lack of perceived memory problems. One stated ‘You know, so for being 61 … my memory’s fairly good. So I don’t think it’s, I mean I might get some sort of dementia because … it’s hereditary or it just happens’ (P3). Another continued:

‘ … as far as daily life I don’t have any problems. … I think everybody has some type of memory loss, like … there’s a lot of things I don’t remember from the past … you know. So you recall some things and some things and somethings you don’t but I don’t, I just think it’s just a natural process and I think naturally some people probably remember more from the past that what other people do. … everybody’s different right? But you know as far as uh, short term things I don’t have any problems with that. And probably, anything I forget, I probably just wasn’t listening’ (P5).

None of the other participants commented on cognitive problems that they were experiencing at the time of interview.

3.4.3. Post-career substance use

Three participants described recreational levels of alcohol use. P3 stated ‘I like beer, I’ll have a, I’m not a wine drinker but I’ll have a scotch with you, I’ll have a rum and coke and, 3 or 4ʹ. P5 added:

‘No I don’t … I don’t have a problem with alcohol though I can consume a lot of it at times … They’ve got to be thinking in summer time I have, maybe I’m drinking too much, but you know … I’ve stopped for long stretches … so I don’t feel like I have any problems like that’.

One participant described alcohol use combined with prescription opioid use to manage the post-career onset of depression and migraine headache:

‘ … there’s a point like when I was … starting to get depressed where … I would seek out … I know my like mother-in-law, or my in-laws they have T3s all the time … so I’d … go and I would sneak T3s, or I would try to get a prescription for T3s and I would pop three or four in a night and have a few glasses of whiskey … just to mellow myself out, and I just liked feeling like … essentially a vegetable on the couch … and just sleep like a rock’ (P1).

For P1, the prescription substance use also included the use of prescription sleeping medication. However, once this participant started to manage the depression and migraine headaches with the assistance of a physician, he relied less on alcohol and pharmaceuticals. Another participant reported a significant history of illicit substance use that started in the last year of his career and persisted into his retirement. This participant also reported a life-long history of depression and ADHD and attempted suicide once. He has now been sober for over a decade and has a demanding career in hockey. This case will be described in detail in subsequent manuscripts that focus on mental health and substance use/abuse.

Two participants reported abstinence from alcohol and prescription medication. One of these participants now uses CBD (cannabidiol) oil for management of pain, mental health, and the potential effects of concussions:

‘ … when I retired I started taking CBD oil to mitigate … you know not even knowing what … the long term effects of concussions would have (been), I just like taking it, you know … just in case you know what I mean? … haven’t taken a pharmaceutical since 2010ʹ (P6).

3.4.4. Generally good health

Four participants described medical problems they experienced post-career. One described migraine and depression, another lifelong depression and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), with two having serious cardiovascular issues (stroke and pulmonary embolism). However, there were many more comments associated with feeling fortunate that they were doing well post-career. For instance, even though P1 struggled with migraine and depression, he stated ‘ … other than that, my hands are fine, my knees, joints … ya, everything’s fine. P3 stated “I’ve been lucky that I haven’t had a lot of repercussions from it (fighting). Ya, I’ve been very fortunate”. Even though P4 had a significant injury history, he stated “uh overall I’m going to say that my, you know, I feel good”. P5 continued “ … I’m healthy … Never had problems with headaches. Never had, I hardly take any medication, ever”. One participant attributed his good post-career functioning to taking ownership of his health:

‘To hopefully maybe get those years back on the, on the back end of it or just, you know, stay healthier and, and not go down like some of these guys that I see go down, like you know what I mean? … there’s a choice here to be made, and I think that a lot of what I do I think requires a lot of discipline … the concepts are easy to understand but it’s nothing more than just, uh, dialing into it and treating yourself with respect and … taking ownership of your own health … not putting it into someone else’s hands. I think we’re so used to that in sports, … oh, let’s go to the medical room and lay on the, medical table and you know … they’ll take care of me … It’s our society, it’s like ya, just go to the doctor and just give me some pills … we all have to be accountable, that’s what I’ve learned … this is what I owe to myself, and this is the way I’m going to do it’ (P6).

Participants 8 and 10 commented specifically about the lack of hockey-related injury. Finally, despite his concerns about perceived changes in memory, P7 added: “ … I haven’t been one of those guys to sit around and … go into (the) dark uh or I can’t talk to people or you know I don’t want to function. That hasn’t happened to me yet … ” (P7).

3.4.5. Interpretive theme 2: We got it wrong -“Don’t do that”

It became evident that most of the participants lived experiences were not consistent with the media reports, biographies, and books that describe negative outcomes for ex-professional ice hockey enforcers. Eight participants commented on how what they have been hearing was inconsistent with their lived experiences. The two participants that did not comment in that manner were the most recently retired. They had their careers at a time when concussions were being treated as a more serious problem in hockey with CTE being found in retired hockey players. In other words they had been exposed to these media reports cautioning against concussion since minor hockey. Therefore, accepting the possibility that they could end up with CTE was a part of their lived experience.

Four participants had strong opinions regarding what some scientists and media are stating about their past profession. When discussing this, they often appeared frustrated. One stated:

‘ … I’m left in a real grey area … on this concussion issue. I was pretty active in that role. I don’t think these players nowadays are as active … you might go 15 NHL team games and not see a fight – come on. Really? So these guys that are getting hurt or getting concerns with uh, depression, drugs, um, you know are they killing themselves because of the fighting, because of off-ice issues or medications? I mean, I throw this out there … I asked my wife because … when I first got in touch with you, and I said OK … I don’t know what’s coming of this, I’m not crying wolf here that I’m an injured ex-player that got, needs some compensation for concussion problems. I said unless you think I’m compromised in some way … you know I asked her … She lives with me every day and she says “not at all” (P3).

Three other participants shared similar thoughts. Regarding some of the reports in the media, another stated “ … I guess that part bothers me, when people use it the wrong, in my opinion the wrong way. Or use the, you know, these peop-these guys that have passed on … for their own cause and it’s not real. It’s not, don’t fucking do that. That’s just not right” (P10). Clearly, this participant felt that the deaths of the ex-professional hockey enforcers had been misrepresented for the purposes of an engaging media story or for book sales.

4. Conclusion

It was hypothesised that ex-professional hockey enforcers would have a significant number of challenges post-career such as 1) cognitive problems such as memory impairments, attention problems, and problems with executive functioning; 2) behavioural problems such as explosivity and being physically violent; 3) problems with mood including depression, anxiety, mania and suicidal ideation; and 4) motor problems such as Parkinsonism, tremor, and gait (e.g., Montenigro et al., Citation2015; Stern et al., Citation2013; Tator, Citation2013). This pattern of symptomology was present in a previous study of five ex-NHL athletes (non-enforcers) who retired from hockey due to multiple concussions (Caron et al. Citation2013). The participants in the current were considered to be at risk due to their high exposure to single or repetitive concussive or sub-concussive events (Armstrong et al., Citation2016; Bailes et al., Citation2019; Edwards et al., Citation2017; Huber et al., Citation2016; Lesman-Segeva et al., Citation2019; McKee, Abdolmohammadi et al., Citation2018; McKee, Stein et al., Citation2018; Mez et al., 2020; Omalu et al., Citation2010; Omalu et al., Citation2011; Stern et al., Citation2011; Tsai, Citation2020; VanItallie, Citation2019). Participants in the current study did have a positive history of concussion with a reported average of 5.9 (range = 2–15). The severity of concussion was indicated by loss of consciousness and missing time as well as neurological signs (i.e. loss of vision) for some participants. Nonetheless, a majority of participants experienced dissonance between what they have heard in print (including biographies), radio, and visual media when compared to their lived experiences. Headlines such as “List of NHL enforcers who have passed away gets longer” (Fitz-Gerald, Citation2015) and “ … there is direct link between hockey concussions and CTE” (Strong, Citation2019) have generated substantial concern in the ice hockey community and have led to what has been termed a “concussion crisis in the national hockey league” (Miller & Wendt, Citation2015). However, despite having significant concussion histories and significant exposure to concussive and sub-concussive blows, most participants expressed a relatively good level of post-career functioning evidenced by their current careers, general lack of cognitive complaint, low levels of substance use, and general good health. The dissonance they experienced was the source of frustration. Their responses indicate that our current efforts at knowledge translation, from science to media, may be failing.

It must be stated that in the current study, one participant did report significant issues with addiction and has had life-long depression that resulted in one suicide attempt. However, at the time of the interview he had 14 years of sobriety, is medically managing his depression, and has a demanding career in hockey. Another participant reported problems post-career that in his opinion were associated with concussions in hockey. This participant sought help from a physician for migraine headaches and depression and is now being successfully treated for both. As described previously, one participant in his 60s was beginning to question short-term memory loss. The remaining seven participants did not believe that their concussion history substantially impacted their functioning or quality of life post-career. In other words, while they did report a positive history of neurotrauma and physical injury, there was not the anticipated pattern of symptomology consistent with the presence of CTE. Therefore, the primary scientific contribution of this work is that contrary to the position of CTE scientists, and despite the potential for post-retirement sequelae proposed by the AP-CA model (Gaetz, Citation2017), this sample reported suffering few if any consequences related to a positive history of concussion and a positive injury history that has led to chronic pain.

The current research is action oriented (Elliot-Groves, Citation2019; Hall, Citation2013; Kovach et al., Citation2014; Martin, Citation2012). Important aspects of the participant’s experience can be used to inform decision-making for current and future hockey athletes and organisations. It is hoped that we are well beyond the days where medical personnel or a coach are concerned about removing a player with a suspected concussion from a game without fear of reprisal such as loss of employment. However, there continues to be anecdotal media reports of players not being removed from play in a number of sports, especially as the stakes get higher during play-offs. There should be continued attempts to ensure that neutral parties such as concussion spotters and physicians (without a conflict of interest) are responsible for removal of players from a game if a concussion is suspected (e.g., National Hockey League, Citation2016). New technology for injury monitoring and detection may also prove beneficial (Hilton, Citation2020).

In addition, significant physical injuries were sustained in this sample that resulted in chronic pain. Fortunately, none of the participants reported debilitating levels of post-career pain. Nonetheless, issues with chronic pain should be considered important when discussing post-career functioning in athletes due to the known overlap in symptomology with neurological sequelae (Gaetz, Citation2017). Another factor to consider is the substantial levels of pain that were reported by participants during the hockey season. Substantial levels of pain, when coupled with a desire to mask injury (especially when there is a threat to employment), may lead to a dependence on pain medication. There have been notable cases of ex-professional hockey enforcers developing substantial issues with addiction to pain medication and sleep aids (Branch, Citation2014; Probert & Kristie, Citation2010). The issues of substance use/abuse also overlap with the sequelae from neurotrauma and should be considered in any discussion of post-career functioning (Gaetz, Citation2017). Medical staff should be prepared to manage pain cautiously and without the use of opioid pain medication and prescription sleep aids when possible.

There has been much speculation about the effects of fighting in hockey on post-career functioning. This is the first study to solicit the opinions of ex-professional hockey enforcers who have not previously discussed these issues with the media or in books form. In this study, the participants were considered content experts (Chilisa & Tsheko, Citation2014; Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2008; Dey et al., Citation2018; Hesse-Biber, Citation2010; Ingram et al., Citation2011; Kovach et al., Citation2014). There was a conscious effort made to value the perspectives of the participant (Bell et al., Citation2017) over the interpretive method (e.g., Larkin et al., Citation2006). Most hockey athletes are gifted story tellers who embed deeper meaning in narrative that is often laced with humour and humility. By crafting questions that were open-ended, they were able to provide a more complete depiction of their experiences both past and current without substantial editorialization from the researcher. Their contradictory perceptions are encouraged within an Indigenous methodology (Martin, Citation2012) and can now be added to the ongoing discussion on the post-career functioning of professional hockey enforcers.

This study had a number of limitations. It relied on the retrospective recall of concussive events including concussion history and severity. In addition, because some of the participants were employed by professional hockey organisations, they may have felt that speaking negatively regarding their current health status may impact their employment. This was addressed by reassuring participants that the quotes utilised would contain no personally identifying information and that they were able to read and revise their transcripts as required prior to data analysis. As evidence that the process worked, one participant sent his transcript back to the author with suggested changes three times. The sample was initially by convenience followed by snowball sampling. This may have led to a bias within the sample that led to contacting participants who were doing well post-career. It must also be acknowledged that people naturally differ in their perceptions of subjective well-being and this trait may have a genetic foundation (An et al., Citation2019). Finally, the sample consisted of 10 participants. Ten participants is not a large number; however, it is approximately double the size of the number of CTE positive cases that involve ex-professional hockey enforcers that would meet the criteria for this study and is above the minimum limit suggested for this type of research (Braun et al., Citation2016).

It must be stated that it is possible that all of the participants in this study have CTE present in their brains or may have at the time of their death. However, in summary, there is very little evidence in this sample to suggest that ex-professional hockey enforcers experience significant negative functional outcomes consistent with CTE symptomology post-career. While approximately half of the sample may have had problems with chronic pain, they generally feel that they are functioning well post-retirement and have transitioned successfully to other careers. What can be stated is that negative outcomes associated with being a professional ice hockey enforcer are not inevitable. However, it is clear that some ex-professional hockey athletes are struggling post-retirement (Caron et al. Citation2013). The answers as to why may be embedded within their mental health, substance use/abuse, and challenges to athletic identity. These topics will be addressed in future publications.

Declaration of interest

There was no financial interest or benefit associated with this research or the production of this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the participants in this study who for their time, willingness to be candid in their comments, and their motivation to improve the sport of hockey for future participants.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study will be made available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author [MG]. The data are not publicly available because they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants. Misuse (intentional or unintentional) could compromise confidentiality and may negatively impact employment or social relationships of the participants within their profession.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michael Gaetz

I have been engaged in research on concussion in sport for approximately 20 years. More recently, I have published a theory intended to explain the experiences of athletes following retirement from contact sport. This work is ongoing and will add to the literature on chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). My other current research interests are how activity may effect quality of life in the elderly and the effects of weight cutting on cognitive and physical functioning in combat sport. My clinical background is as a neurophysiologist. Working in the operating room, I used electrophysiologic procedures to monitor brain and spinal cord functioning during high risk surgeries.

Notes

1. An “enforcer” in ice hockey is someone who fights (bareknuckle) during a hockey game or practice with the intended purpose of protecting a teammate or himself, to change momentum in a game, or to intimidate the opposition.

2. In hockey, a major penalty is given for more serious infractions. It differs from a minor penalty in that it is longer (five or 10 minutes instead of two) and that the player must remain in the penalty box for the entire duration of the penalty whereas minor penalties end after two minutes or when a goal is scored while the player is serving the penalty.

References

- Arthur, Bruce. (2011, August 31). Belak death an end to a wretched summer. National Post. https://nationalpost.com/sports/2011-in-sport-our-most-popular-stories-of-the-year-2

- An, L.Liu, C. Zhang, N. Chen, Z. Ren, D. Yuan, F... ...Bai, B. Yu, T. He, G. (2019). GRIK3 rs490647 is a Common Genetic Variant between Personality and Subjective Well-being in Chinese Han Population. Emerging Science Journal 3(2), 78–21. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.28991/esj-2019-01171

- Armstrong, R. A., McKee, A. C., Stein, T. D., Alvarez, V. E., & Cairns, N. J. (2016, March 21). A quantitative study of tau pathology in 11 cases of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology. 43(2), 154-166. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/nan.12323

- Azad, Tej, D., Amy, L., Pendharkar, A. V., Veeravagu, A., & Grant, G. A. (2016, February 86). Junior Seau: An illustrative case of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy and update on chronic sports-related head injury. World Neurosurgery, 86, 515.e11-515.e16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2015.10.032

- Bailes, J. E., Origenes, A. K., & Alleva, J. T. (2019). Chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Disease-a-Month, 65(10), 100855. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.disamonth.2019.02.008

- Bailes, J. E., Turner, R. C., Lucke-Wold, B. P., Patel, V., & Lee, J. M. (2015). Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy: Is it real? The relationship between neurotrauma and neurodegeneration. Neurosurgery, 62(Suppl 1), 15–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0000000000000811

- Bell, E., Kothiyal, N., & Willmott, H. (2017). Methodology-as-Technique and the meaning of rigour in globalized management research. British Journal of Management, 28(3), 534–550. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12205

- Bieniek, K. F., Blessing, M. M., Heckman, M. G., Diehl, N. N., Serie, A. M., Paolini, M. A., Boeve, B. F., Rodolfo, S.,Reichard,R., Dickson, D.W. (2020). Association between contact sports participation and chronic traumatic encephalopathy: A retrospective cohort study. Brain Pathology, 30(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/bpa.12757

- Bieniek, K. F., Ross, O. A., Cormier, K. A., Walton, R. L., Soto-Ortolaza, A., Johnston, A. E., DeSaro, P.,Boylan, K.B., Graff-Radford, N.R., Wszolek, Z.K., Rademakers, R., Boeve, B.F., McKee, A.C., Dickson, D.W. (2015). Chronic traumatic encephalopathy pathology in a neurodegenerative disorders brain bank. Acta Neuropathologica, 130(6), 877–889. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-015-1502-4)

- Bird-David, N. (1999). ‘Animism’ revisited: Personhood, Environment, and relational epistemology. Current Anthropology, 40(S1), S67–S79. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/200061

- Blakemore, E. (2016, February 22). The terrifying link between concussions and suicide”. Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/to-your-health/wp/2016/02/22/the-terrifying-link-between-concussions-and-suicide/

- Botha, L. (2011). Mixing methods as a process towards indigenous methodologies. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 14(4), 313–325. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2010.516644

- Branch, J. (2014). Boy on Ice: The life and death of Derek Boogaard. Harper Collins Publishers.

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Weate, P. (2016). Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In B. Smith & A. C. Sparkes (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 191–205). Routledge. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315762012

- Brownlee, J., & Berthelsen, D. (2008). Developing Relational Epistemology Through Relational Pedagogy: New Ways of Thinking About Personal Epistemology in Teacher Education. In M. S. Khine (Ed.), Knowing, Knowledge and Beliefs Epistemological Studies across Diverse Cultures. Springer. (pp. s67-s79) https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6596-5_19

- Bryman, A. (2006). Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: How is it done? Qualitative Research, 6(1), 97–113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794106058877

- Bryman, A. (2007). Barriers to Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(1), 8–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2345678906290531

- Burke, J. R., de Waal, C., Stefurak, T., & Hildebrand, D. L. (2017). Understanding the philosophical positions of classical and neopragmatists for mixed methods research. Köln Z Soziol, 69(Suppl 2), 63–86. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-017-0452-3

- Burley, C. (2020). Suicide as a clinical feature of chronic traumatic encephalopathy: What is the evidence? Aggression and Violent Behavior, 54(September-October): 101417. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2020.101417

- Caron, G. Jeffery, Gordon A. Bloom, Karen M. Johnston, Catherine M. Sabiston. (2013). “Effects of multiple concussions on retired national hockey league players.” Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology35: 168–179. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.35.2.168

- Causadias, J. M., Updegraff, K. A., & Overton, W. F. (2018). Moral Meta-Narratives, Marginalization, and Youth Development. American Psychologist, 73(6), 827–839. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000252

- Chilisa, B., & Tsheko, G. N. (2014). Mixed Methods in Indigenous Research: Building Relationships for Sustainable Intervention Outcomes. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 8(3), 222–233. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689814527878

- Cochran, P. A. L., Marshall, C. A., Garcia-Downing, C., Kendall, E., Cook, D., McCubbin, L., & Reva Mariah, S. G. (2008). Indigenous Ways of Knowing: Implications for Participatory Research and Community. American Journal of Public Health, 98(1), 22–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2006.093641

- Creswell, J. W. (2015). Revisiting Mixed Methods and Advancing Scientific Practices. In S. N. Hesse-Biber & R. Burke Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry. Oxford University Press Incorporated. ProQuest Ebook Central. (pp. 57-71). http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ufvca/detail.action?docID=2044599

- Creswell, J. W., Vicki, L., & Clark, P. (2007). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research (3rd ed.). Los Angeles. Usage. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428108318066

- d´Ishtar, Z. (2005). Striving for a common language: A white feminist parallel to Indigenous ways of knowing and researching. Women’s Studies International Forum, 28(5), 357–368. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2005.05.006

- Davis, G. A., Castellani, R. J., & McCrory, P. (2015). Neurodegeneration and sport. Neurosurgery, 76(6), 643–655. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1227/neu.0000000000000722

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2008). Introduction: Critical methodologies andIndigenous inquiry. In N. K. Denzin, Y. S. Lincoln, & L. T. Smith (Eds.), Handbook of critical and Indigenous methodologies (pp. 1–20). Sage. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483385686.n1

- Dey, A., Singh, G., & Gupta, A. K. (2018). Women and Climate Stress: Role Reversal from Beneficiaries to Expert. World Development, 103, 336–359. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.07.026

- Edwards, I. I. I., George, A., Moreno-Gonzalez, I., & Soto, C. (2017). Amyloid-beta and tau pathology following repetitive mild traumatic brain injury. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 483(4), 1137–1142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.07.123

- Elliot-Groves, E. (2019). A culturally grounded biopsychosocial assessment utilizing Indigenous ways of knowing with the Cowichan Tribes. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 28(1): 115–133. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2019.1570889

- Feilzer, M. Y. (2010). Doing Mixed Methods Research Pragmatically: Implications for the Rediscovery of Pragmatism as a Research Paradigm. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 4(1), 6–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689809349691

- Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving Integration in Mixed Methods Designs—Principles and Practices. Health Services Research, 48(6), 2134–2156. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12117

- Fitz-Gerald, S. (2015, September 22). List of enforcers who have passed away gets longer. The Star. https://www.thestar.com/sports/hockey/2015/09/22/list-of-nhl-enforcers-who-have-passes-away-gets-longer.html

- Fralick, M., Thiruchelvam, D., Homer, C. T., & Redelmeier, D. A. (2016). Risk of suicide after a concussion. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 188(7), 497–504. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.150790

- Gaetz, M. (2017). The multi-factorial origins of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) symptomology in post-career athletes: The athlete post-career adjustment (AP-CA) model. Medical Hypothesis, 102, 130–143. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2017.03.023

- Gavett, B. E., Stern, R. A., & McKee, A. C. (2011). Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: A potential late effect of sport-related concussive and subconcussive head trauma. Clinics in Sports Medicine, 30(1), 179–188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csm.2010.09.007

- Hall, J. N. (2013). Pragmatism, evidence, and mixed methods evaluation. New Directions for Evaluation, 13815–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.20054

- Held, M. B. (2019). Decolonizing Research Paradigms in the Context of Settler Colonialism: An Unsettling, Mutual, and Collaborative Effort. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918821574

- Hesse-Biber, S. (2010). Qualitative Approaches to Mixed Methods Practice. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(6), 455–468. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410364611

- Hesse-Biber, S. N., & Burke Johnson, R. (Eds.). (2015). The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry. Oxford University Press, Incorporated. ProQuest Ebook Central. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ufvca/detail.action?docID=2044599

- Hilton, D. J. (2020). Sports Monitoring with Moving Aerial Cameras Maybe Cost Efficient For Injury Prevention. SciMedicine Journal, 2(3), 132–137. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.28991/SciMedJ-2020-0203-3

- Huber, B. R., Alosco, M. L., Stein, T. D., & McKee, A. C. (2016). Potential long-term consequences of concussive and subconcussive injury. Physical Medicine Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 27(2), 503–511. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2015.12.007

- Ingram, D., Wilbur, J., McDevitt, J., & Buchholz, S. (2011). Women’s Walking Program for African American women: Expectations and recommendations from participants as experts. Women & Health, 51(6), 566–582. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2011.606357

- Kawagley, A. O. 1993. “A Yupiaq world view: Implications for cultural, educational, and technological adaptation in a contemporary world”. Ph.D. Thesis in Social and Educational Studies. University of British Columbia.

- Kovach, M., Carrier, J., Montgomery, H., Barrett, M. J., & Gilles, ca. 2014. “Indigenous Presence: Experiencing and envisioning indigenous knowledges within selected post-secondary sites of education and social work”. http://www.usask.ca/education/profiles/kovach/index.php

- Larkin, M., Watts, S., & Clifton, E. (2006). Giving voice and making sense in interpretive phenomenological analysis. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 102–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp062oa

- Larsen, K. (2017, January 12) Repeated concussions suffered by the star cowboy may have led to permanent brain changes, says expert. CBC News https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/mother-of-ty-pozzobon-says-concussion-related-depression-a-factor-in-his-death-1.3930708

- Lesman-Segeva, O. H., La Joie, R., Stephens, M. L., Sonni, I., Tsai, R., Viktoriya Bourakova, A. V., Visani, L. E., O'Neil, J.P., Baker, S.L., Gardner, R.C., Janabi, M., Chaudhary, K., Perry, D.C., Kramer, J.H., Miller, B.L., Jagust, W.J., Rabinovic G.D. (2019). Tau PET and multimodal brain imaging in patients at risk for chronic traumatic encephalopathy. NeuroImage: Clinical, 24, 102025. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2019.102025

- Madsen, T., Erlangsen, A., Orlovska, S., Mofaddy, R., Nordentoft, M., & Benros, M. E. (2018). Association between traumatic brain injury and risk of suicide. Journal of the American Medical Association, 320(6), 580–588. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.10211

- Marin, A., Medin, D., & Ojalehto, B. (2017). Conceptual change, relationships, and cultural epistemologies. In T. G. Amin & O. Levrini (Eds.), Converging perspectives on perceptual change (pp.43-50). Routledge. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315467139-7

- Martin, D. H. (2012). Two-Eyed Seeing: A Framework for Understanding Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Approaches to Indigenous Health Research. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 44(2), 20–42.

- McGloin, C. (2015). Listening to hear: Critical allies in Indigenous Studies. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 55(2), 267–282.

- McKee, A. C., Stein, T. D., Huber, B. R., & Alvarez, V. E. (2018). Chapter 2 - Pathology of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. In A. E. Budson, A. C. McKee, R. C. Cantu, & R. A. Stern (Eds.), Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (pp.19-38). Elsevier. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-54425-2.00002-3