?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The incidence of occupational injuries and diseases among informal welders demands an understanding of a wider perspective that goes beyond the identification of hazards and preventive measures to minimize their effects. The literature on economic cost at the workplace has mainly focused on the formal sector with very little attention to the informal work environment. This paper fills this gap by estimating lost man-days and the economic cost among informal welders. The cross-sectional survey design employing a quantitative approach was used for the study. The data were collected from 220 informal master welders and their apprentices. Musculoskeletal injuries, malaria, hypertension and respiratory diseases were the major injuries and diseases leading to the highest days (35 days and above) lost for masters and apprentices. The master welders spent more days off work than the apprentices because they performed most of the technical work and were exposed to hazards for a longer period. These occupational-related injuries and diseases led to a total economic cost of 7.7% and 9.4% of masters and apprentices’ total earnings, respectively. Environmentally safe working conditions of informal welders would reduce the occurrence of injuries and diseases and give them an opportunity to sustain themselves and their dependents and contribute to national development.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Informal sector workers are exposed to occupational hazards which often lead to occupational injuries and diseases and its associated economic cost. However, the literature on economic cost at the workplace mainly focuses on the formal sector with little attention to the informal sector. Our study fills this gap by estimating economic cost of injuries and diseases among informal welders in Ghana. The study revealed that musculoskeletal injuries, malaria, hypertension and respiratory diseases were the major injuries and diseases leading to the highest days (35 days and above) lost for informal welders. These occupational-related injuries and diseases led to a total economic cost of 8.1% of informal welders total earnings. The acquisition of skills and knowledge on hazard prevention would empower informal welders to take their health and safety issues seriously to minimise the occurrence of injuries and disease and its associated economic loss.

1. Introduction

More recently, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have renewed interest in improving workers’ occupational environment and health. The SDGs 8 and 3 envision the achievement of decent work, promote well-being, and ensure healthy lives for all (United Nations, Citation2015). Over the past century, there has been a dramatic increase in work-related injuries and diseases. According to the International Labour Organization (Citation2013), about 2.02 million work-related diseases yield to occupational death every year. Driscoll et al. (Citation2020) assert that an estimated 1.53 million deaths, globally, are attributable to occupational risk factors. Furthermore, approximately 2.8% death and 3.2% DALY (disability-adjusted life years) lost globally are attributable to occupational accidents at the workplace Driscoll et al., (Citation2020). Evidence suggests that occupational injuries and diseases resulting from harmful work environment constitute between 1.8% and 6.0% ($2.8 trillion) loss in Global Gross Domestic Product (GDP), in direct and indirect costs of injuries and diseases (International Labour Organization, Citation2013; Takala et al., Citation2014). However, the burden of occupational injuries and diseases is more pronounced in Africa. Africa has a fatality rate of 16.6 per 100,000 persons in the labour force, although it contributes approximately 12% (the lowest) to the world’s work-related deaths (Hamalainen et al., Citation2017). The statistics suggest that occupational health and safety at workplaces in Africa is poor. The aftermath of poor occupational health and safety at workplaces is the exposure to occupational injuries and diseases caused by physical, chemical or biological hazards, or overload of unreasonably heavy physical work or ergonomic factors that may be hazardous to health and reduce working capacity (Singh et al., 2012; World Health Organization, Citation1995).

The exposure to occupational hazards often leads to occupational injuries and diseases associated with economic cost (Fayad et al., Citation2003; International Labour Organization, Citation2013). Evidence indicates that occupational injuries, diseases, and deaths create cost not only on the employee but also on employers and the community (Safe Work Australia, Citation2015; Shalini, Citation2009). A study by Safe Work Australia (Citation2015) revealed that workers, employers and the community bears approximately 77%, 5% and 18% of the cost of work-related occupational injuries and diseases, respectively. Shalini (Citation2009) indicates that employers incur between US$11,287 and US$132,749 medical costs for Mauritius’ occupational accident. Correspondingly, the state incurs between US$259,000 and US$718,574 of occupational accidents’ medical cost while the employee loses a maximum of US$185,358 contingent on the number of lost man-days from work due to occupational injuries and diseases. Data provided by the Department of Factories Inspectorate in Ghana indicate that employers lose about 60,000 USD each year and 60 USD per case due to occupational accidents (Oppong, Citation2014).

Consequently, determining the cost of occupational accidents on decent work, health and well-being are critical for global economic production, preventing early retirement, unemployment and poverty. However, studies on occupational health and safety have sparsely focused on the cost of occupational health and safety (Adei et al., Citation2019; International Labour Organization, Citation2013; Kim et al., Citation2016; Niu, Citation2010). Furthermore, the literature on cost of occupational injuries and diseases have primarily centred on the formal sector of developed economies (Battaglia et al., Citation2014; Boden & Galizzi, Citation1999; Dembe, Citation2001; Leigh et al., Citation2004; Lebeau et al., Citation2014; Miller & Galbraith, Citation1995). Similarly, the literature on cost of occupational accident in developing economies has been in the formal sector while neglecting the informal sector. Shalini (Citation2009) estimated the cost of occupational injuries and diseases in the formal sector of Mauritius. Suglo and Gyimah (Citation2014) assessed the cost of industrial accidents of a mining company in Ghana. Nevertheless, the informal sector, which is said to be the backbone of developing economies (African Development Bank, Citation2018; Benjamin & Mbaye, Citation2012; UN-Habitat, Citation2016), has been understudied concerning cost of occupational accidents (Adei et al., Citation2019). Studies on occupational health and safety in the welding industry have widely focused on awareness, attitude, knowledge, safety practices, hazards and incidence of injuries and diseases (Alexander et al., Citation2016: Cadiz et al., Citation2016; Mehrifar et al., Citation2019: Okuga et al., Citation2012: Tadesse et al., Citation2016: Tagurum et al., Citation2018). All these studies highlight that the informal welding activities are associated with precarious working conditions, operating in unregulated and unplanned environment and employ rudimentary forms of production which engender occupational accidents.

Bonsu et al. (Citation2020) assert that with the rise in informal sector activities in developing countries, it is expected that the prevalence of occupational hazards, injuries and diseases is likely to surge, which may negatively affect health outcomes and have a toll on informal sector workers expenditure. Therefore, neglecting the estimation of economic cost would not safely guide the working environment of informal welders and ensure the formulation and implementation of targeted strategies policies to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. However, not many studies have been done to estimate the economic cost of injuries and diseases among informal welders in developing countries, particularly Ghana. This paper, therefore, contributes to bridging the gap in the literature by adapting the human capital method to estimate the economic cost of occupational injuries and diseases among informal welders in Ghana. Following (Kumar & Dharanipriya, Citation2014; Hisey, Citation2014; Lombardi et al., Citation2005; Raphela, Citation2015), the injuries considered in this study were burns, laceration, musculoskeletal injuries, fracture, eye, sprain and strain and electric shock. Also, occupational diseases considered in this study were headache (Greenberg & Vearrier, Citation2015; Korczynski, Citation2000; Uzun et al., Citation2012), malaria (Adei et al., Citation2019; Ametepeh et al., Citation2011; Bonsu et al., Citation2020), hypertension (Xu et al., Citation2017), diabetes (Alexander et al., Citation2016), respiratory (Chauhan et al., Citation2014; Riccelli et al., Citation2020), eye (Alexander et al., Citation2016; Chauhan et al., Citation2014), ear (Chauhan et al., Citation2014), skin (Brans, Citation2012; Chauhan et al., Citation2014; Dixon & Dixon, Citation2004), and musculoskeletal disease (Chauhan et al., Citation2014; Shahriyari et al., Citation2018). The understanding of the dynamics of economic cost of injuries and diseases would guide policymakers in the design of policies to streamline the activities of informal welders. This will reduce informal welders exposure to injuries thereby decreasing their economic cost of injuries and diseases.

2. Review of the literature on the estimation of economic cost

Dorman (Citation2000:1) asserts that “occupational injury and illness are matters of health, but they are also matters of economics, since they stem from work, and work is an economic activity”. Economic assessments in OHS have sought to establish a relationship between profits, costs, and workers’ productivity and health and safety. Gunderson (Citation2002) suggests that economic assessment in OHS aims to provide decision-makers with the relationships between OHS issues and annualized lost time and lost wage estimates, insurance and compensation claims, among others, which tend to affect the overall productivity of workers and businesses. In such circumstances, economic assessments of OHS encompass both causes and consequences (Dorman, Citation2000). Specific studies have developed specifying the relationships between worker productivity with specific variables that render the worker less efficient regarding time spent on an activity, workplace ill-health and the economic effects on the workers, enterprises, nations, and the world. Cockburn et al. (Citation1999) for instance, studied the effect of medications on productivity. Burton et al. (Citation1998) studied the relationship between allergies and productivity among telephone customer service operators while Dewa and Lin (Citation2002) and Druss et al. (Citation2001) studied depression and stress-related disorders at the workplace. In all these cases, the studies showed how the variables have, in most cases, adverse effects on work performance in the form of “presenteeism” or reduced effectiveness in one’s job, absenteeism and increased occupational injuries.

Despite these emerging findings, there have been persistent concerns about the challenge of building a relationship between cost savings interventions (Edington, Citation2001). The reason is that cost as an economic variable is a controversial measurement variable in the field. Different aspects of cost have been considered in several studies. These differences in economic assessments of cost in OHS have related to economic and non-economic costs (Burton et al., Citation1998; Drummond et al., Citation2005; Lee et al., Citation2005; Targoutzidis, Citation2011), private and social cost (Dahlgren & Whitehead, Citation2007; Maumbe & Swinton, Citation2003), financial and implicit cost (Leigh et al., Citation1997; Warch, Citation2002), and cost-shifting perspectives (Chenoweth, 1990). In addition to these cost assessment perspectives, some studies have incorporated opportunity costs in OHS issues’ economic assessments (Bunn et al., Citation2001; Lanoie, Citation1991; Maumbe & Swinton, Citation2003). Dorman (Citation2000: 25) asserts that the “value to society of the goods or services (including leisure) it could otherwise have enjoyed had there been no diversion of resources resulting from accidents or illness at work” is another perspective to which the cost in OHS can be estimated—the opportunity cost. The lost output, costs of treatment and rehabilitation, cost of administering the various programmes to prevent, compensate or remediate occupational injury and disease are all opportunity costs (Bunn et al., Citation2001; Dorman, Citation2000).

Furthermore, various specific cost models have been adopted by different authors to assess the cost of occupational injuries; human capital, friction costs, willingness to pay, jury awards and health status index methods (Butchart et al., Citation2008; Lebeau & Dugua, Citation2013; Leigh et al., Citation2004). However, two popular methods have been developed by economists for estimating the economic cost of occupational accidents; human capital (HC) and the willingness to pay (WTP) methods (Lebeau & Dugua, Citation2013). Lebeau and Dugua (Citation2013) assert that the HC approach considers the contribution of an individual to society as a contribution to the Gross Domestic Product. The contribution of the worker to the GDP can be determined by his gross income (before income tax) which relates to the marginal productivity of labour. In estimating the economic cost for short-term absences, the human capital approach employs the multiplication of the number of hours by hourly wage. In the case of long absences in which the loss of productivity last over many years, an estimation of the present value of future earnings is employed by the human capital method. Goodchild et al., (Citation2002) indicate that HC method presumes people are valuable economic resources used to produce a future stream of production in an economy. Therefore, an injury limits or truncates the stream of production that causes a reduction in the overall quantity of human capital available to the economy. Leigh et al. (Citation2000) study on the estimation of productivity losses is considered as one of the most complete and vital studies to apply the human capital method (Lebeau & Dugua, Citation2013). The HC method categorizes cost into direct and indirect cost. Direct cost emphasizes the cost incurred or anticipated to be incurred for administrative, medical care and insurance. Expanded direct costs include payments for hospital, physician, and allied health services; rehabilitation; nursing home care; home healthcare medical equipment; and insurance administration. Indirect costs characterize productivity losses, including wage losses, household production losses, and employer productivity losses. The WTP, on the other hand, takes into consideration the worth people put on the health of retirees, children and homemakers; on pain and suffering; and on variations across individuals and communities (Lebeau & Dugua, Citation2013). This study employed the HC method as used by Leigh et al. (Citation2000) because their study is considered as one of the most complete and important to date.

These methods of estimating economic cost have been critical in revealing economic costs of OHS to individuals, firms and communities. The central argument is that countries with better health indices are seen to grow and develop economically. In the debates between human capital and development of which health places a key component, the conceptualization provides credence to mainstreaming economic assessments in OHS (Lipsey, Citation1996). Understanding and estimating economic cost provides perspectives on which decision-makers and policymakers can make informed OHS interventions decisions.

3. Methods

3.1. Study setting

Suame Magazine, located in the northern section of Kumasi, is a hub of agglomerated small-scale mechanical garages that manufacture vehicle parts and provide other mechanical services to the Kumasi Metropolis and the West African sub-region. Suame Magazine and Asafo mechanical garages have positively impacted productive employment creation and revenue generation in Kumasi (Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly, Citation2010). Suame Magazine is an industrialized area with numerous workshops for metal engineering and vehicle repairs in Ghana and serves as a centre of employment to about 200,000 workers in the Kumasi Metropolis (Adeya, Citation2006; Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly, Citation2010). The industrial enclave recognition is due to its significant impacts on productive employment creation and revenue generation in Kumasi and the services rendered in the sub-region (Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly, Citation2010).

3.2. Research approach

The cross-sectional survey design was used to obtain data from master welders and their apprentices in the Suame and Asafo Magazine. The rationale for the use of the cross-sectional survey design is that the data on the prevalence and cost of occupational injuries and diseases were collected and recorded at a given point in time (Creswell, Citation2011; Olsen et al., Citation2010). This study adopts quantitative research approach to gather and analyse primary data to accomplish the aims of the study. A census of master welders (with apprentices) in the Suame magazine and Asafo Magazine was undertaken in November 2016 since a sampling frame was not readily available. A total of 180 and 10 master welders were identified at Suame and Asafo Magazine. The EPI Info 7 software was used to calculate the sample size at a 95% confidence level. Proportional stratification was used to select 122 master welders from Suame magazine and seven from Asafo magazine for the survey. The response rate was 85% for the master welders. A senior apprentice of a master welder was included in the study for the triangulation of responses. The data were collected from 09 January to 28 February 2017.

A close-ended questionnaire was used to collect the data. The questionnaire had three sections; (a) socio-demographic data such as age, educational attainment, income/allowance, number of hours worked per day and working experience, (b) the second section covered self-reported injuries and disease in 2016, number of lost man-days due to injuries sustained and diseases suffered, and (c) the nature of costs incurred by master welders and apprentices on healthcare and absenteeism due to injury or diseases associated with their work. A letter of introduction was obtained from the head of the Department of Planning to undertake the study. Both verbal and informed consent was sought from the study participants before data collection exercise started. Participants were assured of strict confidentiality of the information they provided. They were made to understand that their participation in the study was voluntary and as such, they were free to opt-out of the survey anytime they deem it fit.

The human capital method as used by Leigh et al. (Citation2000) was adapted to estimate the economic cost of injuries and diseases reported by welders. Economic cost was categorized into the direct cost and indirect costs. For the study, the following variables were considered under direct costs: medical expenses for hospitals/clinics/pharmacy/chemical shops; and health insurance administration cost. The indirect cost was calculated using wage losses, transportation cost for medical treatment, and cost of damage to material or equipment.

An attempt was made at estimating indirect cost, which according to the National Safety Council (Citation1992), is very difficult to calculate compared to direct cost because many variables need to be considered, for which data may not be readily available. It is also worthy of note that calculating the cost of occupational diseases has been a difficult task since sometimes one cannot easily distinguish between normal diseases that affect the general population and those occupational-related. These notwithstanding, following studies that have established diseases arising from occupational health risk, this study estimated the cost of occupational diseases (Adei et al., Citation2019; Alexander et al., Citation2016; Bonsu et al., Citation2020; Brans, Citation2012; Chauhan et al., Citation2014; Dixon & Dixon, Citation2004; Greenberg & Vearrier, Citation2015; Korczynski, Citation2000; Riccelli et al., Citation2020; Uzun et al., Citation2012; Shahriyari et al., Citation2018; Xu et al., Citation2017). Data collected from the field were collated, edited and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS-IBM version 20). Frequency and cross-tabulation were used to estimate self-reported occupational injuries and diseases, lost man-days, and economic cost of the informal welders. The worst-case scenario was used to estimate the lost wages of welders due to the understatement of lost wages during lost man-days resulting from occupational injuries/diseases. The formula for the estimation of lost wages using worst-case scenario is as follows:

where D—lost man-days due to occupational injuries/diseases, DI is the daily income paid to master welders and LW is the lost wage.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic and economic characteristics of welders

The survey covered a sample of 220 male welders out of which 110 were masters, and 110 were apprentices. About 90% of both master and apprentice welders were aged between 18 and 49 years, with their mean ages being 45 and 28 years, respectively. Approximately 66% of the master welders and 79.1 % of the apprentices had attained education at the basicFootnote1 level. Also, 5.5% and 6.4% of the masters and apprentices had not received any formal education. The study further revealed that the number of hours the welders worked in a day varied according to the volume of work available and electricity availability. Approximately 82.0% of masters and 86.0% of apprentices worked more than the recommended eight hours per day for Ghana’s formal sector. About 58% of the masters reported welding for more than 13 years (excluding their years of apprenticeship). On average, an apprentice was given an allowance of GH¢10.00 (US$2.27) a day by his master, which was more than the minimum daily wage of GH¢8.00 (US$1.81) in 2016. The mean monthly income earned by masters was GH¢931.00 (US$ 211.59) compared with the average monthly income of GH¢495.47 (US$ 112.60) reported in the Ghana Living Standards Survey (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2014).

4.2. Occupational injuries and diseases and lost man-days in 2016

Out of the 110 master welders, 41 (37.4%) sustained injuries while 48 (43.6%) out of 110 apprentices also reported work-related injuries. The injuries sustained by welders were laceration (32.4%), chronic back and shoulder pain (26.5%), burns (16.7%), muscle sprain and strain (11.7%), fractures (6.9%), eye injuries (4.9%), and electric shock (0.9%). The survey revealed that 136 (61.8%) reported occupational diseases in 2016, comprising 68 (61.8%) of masters and apprentices. Correspondingly, occupational-related diseases that the master welders and apprentices reported of were malaria (55.5%), eye diseases (14.4%), respiratory diseases such as chronic cough and asthma (12.4%), headache (3.8%), diseases of the ear (1.0%), diabetes (0.5%) and chronic skin diseases (0.5%). Aside from the diseases mentioned above, 16.7% of master welders also reported of hypertension.

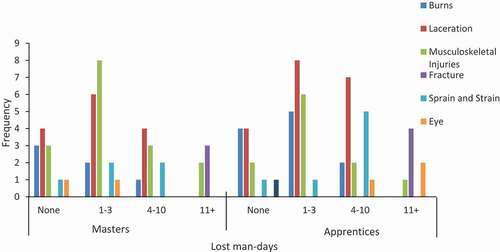

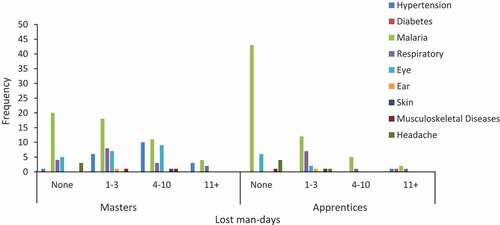

An analysis of the major injuries and the number of lost man-days revealed that apprentices lost more days (342) than masters (316). Approximately 24% of welders continued to work after sustaining occupational injuries such as laceration, burns, musculoskeletal injuries, strains and sprains and eye injuries in 2016 (see ). About 38% and 26% of the welders spent between 1–3 days and 4–10 days, respectively, away from work due to occupational injuries. Furthermore, even though 68 masters reported occupational diseases in 2016, 46 of them lost 653 days while 22 of them continued to work even after the diseases’ signs and symptoms had shown. Out of the 68 apprentices who reported diseases, 45 continued working while 23 were absent from work for 213 days for the period under consideration. The self-reported occupational diseases and the number of lost man-days revealed that malaria was the most reported disease which welders mostly treated without taking some time off work. Welders spent between one to three days away from work due to occupational diseases such as malaria, respiratory diseases, eye diseases and hypertension (see ). However, for the apprentices, the diseases included malaria (1 −34 days), respiratory diseases (1–18 days), and eye diseases (1–3 days). On average, diseases such as malaria (1–35 days or more), hypertension (1–34 days), eye diseases (1–34 days) and respiratory diseases (1–34 days) were the ones that resulted in the most lost man-days for masters.

4.3. Estimated economic cost incurred by welders

shows that 41 (37.3%) and 68 (61.8%) masters incurred economic losses due to work-related injuries and diseases in 2016. The total economic cost (losses) reported by the masters were GH¢21,290.00 (US$4,838.64) for injuries and GH¢20,210.00 (US$4,593.18) for diseases. These translated into the direct cost of GH¢10,096.00 (US$2,294.54) and GH¢ 15,746.00 (US$3,578.63) and indirect cost of GH¢11,194.00 (US$2,544.09) and GH¢ 4,464.00 (US$1,014.54) for injuries and diseases, respectively. The medical bills for injuries ranged from GH¢10.00 (US$2.27) to GH¢2,500 (US$568.18). The total economic cost (losses) as reported by masters indicates that the masters lost 1.1% of their total earnings in the period under review.

Table 1. Estimated Economic Cost of Diseases and Injuries by Welders in 2016

Only 21% of the sampled masters had registered with the National Health Insurance Scheme, which means that most had to pay cash for their healthcare The lost wages given by the masters was only GH¢ 4,040.00 (US$918.18) for injuries and GH¢ 3,540.00 (US$804.54) for diseases. The reason was that their senior apprentices worked and provided them with an income whenever they sustained injuries or suffered from occupational diseases while they recovered at home.

This scenario might not create the correct picture of economic losses, therefore, the worst-case scenario was used to calculate the lost wages. This was operationalized by calculating the real losses of wages based on the number of lost man-days due to injuries and diseases and the expected wage loss. Employing this approach, the lost wages were GH¢7,687.00 (US$1,747.04) for injuries and GH¢11,191.00 (US$2,543.40) for diseases, an increase of 90.3% for injuries and 216.1% for diseases. With a minimum loss of GH¢ 27.00 and a maximum of GH¢2,500.00 (US$568.18), the total indirect cost for injuries increased from GH¢11,194.00 to GH¢11,284.00 (0.8%), and that of diseases also increased from GH¢4,464.00 to GH¢12,165.00 (172.5%).

Of the 110 apprentices, 48 (43.6%) and 68 (61.8%) incurred economic cost in 2016 due to occupational injuries and diseases, respectively. Approximately10% of the apprentices had registered with the National Health Insurance, and none incurred any cost related to damage of materials and equipment resulting from an occupational accident. From , the estimated economic cost incurred by apprentices were GH¢ 17,086.00 (US$3,883.18) for injuries and GH¢ 9,174.00 (US$2,085.00) for diseases. These were made up of GH¢8,700.00 (US$1,977.27) and GH¢7,358.00(US$1,672.27) direct cost and GH¢8,386.00 (US$1,905.90) and GH¢1,816.00 (US$412.72) indirect cost for injuries and diseases, respectively. The major component of the indirect cost provided by the apprentices was the lost allowance, which amounted to GH¢ 3,120.00 (US$709.09). The minimum medical costs spent by an apprentice were GH¢10.00 (US$2.27) for injuries and GH¢15.00 (US$3.40) for diseases while the maximum was GH¢1000.00 (US$227.27) for injuries and GH¢3,500.00 (US$795.45) for diseases.

shows that the economic cost incurred as a result of occupational injuries and diseases by the welders (masters and apprentices) amounted to GH¢49,241.00 (US$11,191.13) and GH¢ 26,260.00 (US$5,968.18), respectively. This translates into master welders and their apprentices losing 7.7% and 9.4%, respectively, of their total annual earnings as economic cost (losses) on occupational injuries and diseases.

Table 2. Welders’ Economic cost as a percentage of annual income in 2016

5. Discussion

This study provides the baseline information on economic cost of injuries and diseases among informal welders in Ghana. As a result of the fact that this study constitutes the baseline information on economic cost of injuries and diseases in the informal sector, it was difficult getting similar studies to compare with the findings of this study. To compensate for this limitation, we compared our findings with studies that estimated economic cost in the formal sector.

The injuries sustained by master welders and their apprentice were laceration, musculoskeletal injuries (chronic back and shoulder pain, burns, muscle sprain and strain, fractures), eye injuries and electric shock. The literature indicate musculoskeletal injuries are caused by ineffective ergonomic practices in carrying and lifting heavy machines and equipment, squatting, bending and carrying or moving loads by hand or by bodily force (Halvani et al., Citation2014; Shahriyari et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, Hong and Ghobakhloo (Citation2014) assert that welding activities produces sparks of fire and spatters, causing burns if precautionary measures are not taken. It was, therefore, not surprising when 16.7% of welders reported of burns in 2016. The survey revealed that the occupational-related diseases that the master welders and apprentices reported of were malaria, eye diseases, respiratory diseases (chronic cough and asthma), diseases of the ear, diabetics and chronic skin diseases. Aside from the forestated diseases, approximately 17% of master welders also reported of hypertension. Studies conducted by Okuga et al. (Citation2012), Coggon et al. (Citation1994), Rothwell (Citation2012), Z’gambo (Citation2015) and Tagurum et al. (Citation2018) have also documented these injuries and diseases among welders. In addition, some of the diseases reported have also been recorded among the top 10 diseases in Ghana (Ghana Health Service, Citation2017).

The results of the study point out that apprentices lost more days (342) than masters (316) after suffering from occupational injuries and diseases. Even though an equal number of masters and apprentices reported occupational-related illness, the master welders spent more days off work than the apprentices probably because they performed most of the technical work and they have also been exposed to hazards for a more extended period. Self-reported diseases such as malaria, hypertension and respiratory diseases, which lead to an extended period of absenteeism, could have a more significant impact on work output, productivity and the income level of the welders especially if the person is the breadwinner of the family and the owner of the enterprise as well. The responses show that 9.8% and 3.3% of welders lost 27 or more days after suffering from occupational injuries and diseases. This corroborates Keogh et al. (Citation2000) finding that the worse the injury, the more likely one is to lose more days at work and the probability to lose a job. Due to the economic burden, the possibility of losing the job and clients that apprentices and master welders face as a consequence of sustaining an injury or disease, about 21% and 26% of master welders and apprentices, respectively, continued to work after sustaining occupational injuries.

The total economic cost as a result of occupational injuries and diseases among informal master welders and their apprentice was estimated at GH¢75, 501.00 (US$17,159.00) in 2016. This figure accounts for 8.1% of the annual income/allowance of the master welders and apprentices. Categorically, the total economic cost accounted for the economic cost of 7.7% and 9.4% of the total earnings for masters and apprentices, respectively. This finding confirms the observation by Safe Work Australia (Citation2015) that employees bear the brunt of work-related occupational injuries and diseases compared to employers. Similarly, according to Boden and Galizzi (Citation1999, p. 400) “workplace injuries have major economic consequences for workers and their families and that the economic burden falls heavily on workers”. Although master welders and apprentices experienced occupational injuries and diseases, apprentices incurred more economist cost (as a percentage of their annual allowance) because master welders had senior apprentices, who worked and provided them with an income while recovering at home from an occupational injury or disease. Apprentices maintained that they are usually not paid their daily allowance by their masters except for some few Ghana Cedi given as pocket money for not more than three working days when they suffer from an occupational injury or diseases. Therefore, it is not surprising that 91.5% of the apprentices who were injured or suffered from an illness admitted that they were unable to meet their basic needs after injury or disease because there was a reduction/non-payment of their allowance.

The welders were of the view that occupational injuries and diseases at the workplace were inevitable; however, none was aware of the economic losses they incurred due to the hazards they were exposed to at the workplace. These findings are consistent with observations made by Shalini (Citation2009), who revealed that none of employers surveyed had ever calculated the cost of occupational accidents at the workplace in Mauritius. The finding provides insights for educating informal sector employers and employees on the need to invest in safety and health as master welders revealed they paid allowances to absent injured apprentices for at most 3 days and incurring on the average GH¢200.00 (US$45.45) on damage to equipment, which affect the profitability of their activity.

It is also notable to find that medical cost falls on the state as about 15% of the welders are enrolled on the National Health Insurance Scheme. Categorically, 10% and 21% of the apprentices and masters had enrolled in the National Health Insurance Scheme. Shalini (Citation2009), however, reported that the State incurs about 93% of injured employees medical cost. Although the state bears the medical cost for about 15% of welders, the insurance prevents the impoverishment of workers and their families while improving the use of health services (Lagomarsino et al., Citation2012; Spaan et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, even though contributions to the SSNIT fund are opened to workers in the informal sector, none of the master welders contributed to the fund. This has implications for the survival and economic vulnerability of welders as they lacked social protection for the present and future resulting from occupational injuries and diseases and retirement.

This study has several policy implications that need to be commented on. In the first place, the findings from this study suggest the need for policymakers including health stakeholders to come to design policy to regulate the activities of informal welders. Also, the findings suggest that informal welders should frequently use PPEs in order to reduce their exposure to injuries and diseases which will help them to reduce their exposure to injuries and diseases and ultimately their economic cost. Further, local authorities such as district assemblies should frequently organize education and sensitisation for informal welders with the aim of reducing their exposure to injuries and diseases. Again, the findings of this study imply that informal welders should enrol in a health protection scheme so as to reduce their economic cost incurred when they are exposed to diseases.

6. Conclusion and recommendations for policy

This paper estimates the economic cost of occupational injuries and diseases among informal welders in Ghana. It was discovered that 40.5% and 61.8% of welders had suffered occupational injuries and occupational-related diseases, respectively. The apprentices suffered more injuries compared to their masters because they were inexperienced and did not use the appropriate PPE to protect themselves. Musculoskeletal injuries, malaria, hypertension and respiratory diseases were the major injuries and diseases which led to the highest lost man-days for both masters and apprentices. Again, injuries and diseases which led to a high medical cost also culminated in high wage loss for 2016. The study further uncovered that in 2016, the economic cost incurred due to occupational injuries and diseases by master welders and their apprentices amounted to GH¢49,241.00 (US$11,191.13) and GH¢ 26,260.00 (US$5,968.18), respectively. This accounted for 7.7% and 9.4% of the total earnings for masters and apprentices, respectively.

This study provides information for awareness creation as well as education of informal welders and policymakers on effective safety and health systems that could help prevent injuries and/or diseases in the informal working environment in order to reduce the economic cost of injuries and diseases.

To enhance occupational health and safety in the informal sector, the study recommends that since Ghana has not implemented OHS policy, Parliament should fast-track the passing into law of the OHS Policy (ILO convention C155) to enable the Department of Factories Inspectorate to cover the informal sector which employs more than 70% of the labour force in the country. The passage of OHS policy will help to ensure effective regulation of the activities of OHS policy in order to reduce their exposure to diseases and injuries. The government should also ensure that a master welder receives certification from the National Vocational Technical Institute (NVTI) before opening a welding shop. Master welders should practice for a year or two under regular supervision from government institutions before accredited to train apprentices. The welders should participate in the OHS training, which would be provided by the government. The acquisition of skills and knowledge on OHS would empower them to take their health and safety issues seriously when practising their profession. Implementing these recommendations will make Ghana achieve more tremendous strides to improve its economic status as a middle-income country and achieve the Sustainable Development Goals 3 and 8.

7. Limitations

One limitation recognized in this study was the recollection effect of the informal welders on variables such as income lost, lost man-days and cost of occupational injuries and diseases. It was acknowledged that the informal welders may not recollect accurately the amount of money spent on the occupational injury and diseases. In addressing this limitation, the data on injuries and diseases in 2016 were collected in early January 2017 to ensure that the respondents could recall the events under the study. Notwithstanding this limitation, an estimate of the economic cost of injuries and diseases sustained by informal welders was calculated to make a case for intervention to reduce occupational-related injuries and diseases.

Further research work could focus on the following:

Replication of the study among other welders in developing countries to enhance generalization of the findings.

Use of longitudinal design to collect multiple data sets over a period of time to ensure the establishment of causal relationship.

Focus on the calculation of social and economic cost incurred by welders after sustaining occupational injuries and diseases. Such a study may provide a better picture of the actual cost (economic and social) incurred by welders.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dina Adei

Dr. Mrs Dina Adei holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in Economics and Sociology, a Masters of Science in Development Policy and Planning and a PhD in Planning from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology Kumasi Ghana. She also holds a Certificate in Occupational Health Nursing from the University of California, Irvine and is a Registered Nurse in California. She joined the Department of Planning in January, 2006. Currently, she is a senior lecturer at the department. Her research interest mainly focuses on health planning and occupational health and safety issues. This study is part of a wider project on occupational health and safety among informal sector works in the Kumasi Metropolis of Ghana. The authors of this study jointly researched into the Economic Cost of Occupational Injuries and Diseases among Informal Welders in Ghana.

Notes

1. In this case basic level means completion of education at the primary and Junior High level.

References

- Adei, D., Braimah, I., & Mensah, J. V. (2019). Occupational health and safety practices among fish processors in kumasi metropolitan area. Ghana. Occupational Health Science, 3(1), 83–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-019-00038-0.

- Adeya, N. (2006). Knowledge, Technology and Growth: The Case Study of Suame Manufacturing Enterprise Cluster in Ghana. World Bank Institute, Africa Cluster Case Study.

- African Development Bank. (2018). African Economic Outlook 2018. Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire: African Development Bank.

- Alexander, V., Sindhu, K. N. C., Zechariah, P., Resu, A. V., Nair, S. R., Kattula, D., … Alex, R. G. T. (2016). Occupational safety measures and morbidity among welders in Vellore, Southern India. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health, 22(4), 300–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/10773525.2016.1228287.

- Ametepeh, R. S., Adei, D., & Arhin, A. A. (2011). Occupational health hazards and safety of the informal sector in the sekondi-takoradi metropolitan area of Ghana. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, 3(20), 87–99. Retrieved from https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/RHSS/article/view/10178

- Battaglia, M., Frey, M., & Passetti, E. (2014). Accidents at work and costs analysis: A field study in a large Italian company. Industrial Health, 52(4), 354–366. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2013-0168.

- Benjamin, N., & Mbaye, A. A. (2012). The informal sector in francophone Africa: firm size, productivity, and institutions. Africa Development Forum. Washington DC: The World Bank and Agence Française de Développement.

- Boden, L. I., & Galizzi, M. (1999). Ecnomic consequences of workplace injuries and illnesses: Lost earnings and benefit adequacy. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 36(5), 487–503. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0274

- Bonsu, W. S., Adei, D., & Agyemang-Duah, W. (2020). Exposure to occupational hazards among bakers and their coping mechanisms in Ghana. Cogent Medicine, 7(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2331205x.2020.1825172

- Brans, R. (2012). Mechanical Causes of Occupational Skin Disease. In T. Rustemeyer, P. Elsner, S.-M. John, & H. I. Maibach (Eds.), Kanerva’s Occupational Dermatology (pp. 891–896). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-02035-3_78.

- Bunn, W. B., Pikelny, D. B., Slavin, T. J., & Paralkar, S. (2001). Health, safety, and productivity in a manufacturing environment. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 43(1), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/00043764-200101000-00010.

- Burton, W. N., Chen, C. Y., Schultz, A. B., & Edington, D. W. (1998). The economic costs associated with body mass index in a workplace. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 40(9), 786–792. https://doi.org/10.1097/00043764-199809000-00007.

- Butchart, A., Corso, P., Florquin, N., & Muggah, R. (2008). Manual for estimating the economic costs of injuries due to interpersonal and self-directed violence. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press. Retrieved from:Accessed on September 1st, 2017. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43837/1/9789241596367_eng.pdf.

- Cadiz, A., Camacho, V., & Quizon, R. (2016). Occupational health and safety of the informal mining, transport and agricultural sectors in the Philippines. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public. Health, 47(4), 833-43. Retrieved from http://www.thaiscience.info/journals/Article/TMPH/10983771.pdf

- Chauhan, A., Kishore, J., Danielsen, T. E., Ingle, G. K. (2014). Occupational hazard exposure and general health profile of welders in rural Delhi. Indian journal of occupational and environmental medicine, 18(1), 21–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5278.134953

- Cockburn, I. M., Bailit, H. L., Berndt, E. R., & Finkelstein, S. N. (1999). Loss of work productivity due to illness and medical treatment. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 41(11), 948–953. https://doi.org/10.1097/00043764-199911000-00005.

- Coggon, D., Inskip, H., Winter, P., & Pannett, B. (1994). Lobar pneumonia: An occupational disease in welders. The Lancet, 344(8914), 41–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(94)91056-1.

- Creswell, J. W. (2011). Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research (4th ed. ed.). Addison Wesley.

- Dahlgren, G., & Whitehead, M. (2007). Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health Background document to WHO – Strategy paper for Europe. Institute for Future Studies. Stockholm, Sweden: World Health Organization

- Dembe, A. E. (2001). The social consequences of occupational injuries and illnesses. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 40(4), 403–417. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.1113

- Dewa, C. S., & Lin, E. (2002). Chronic physical illness, psychiatric disorder and disability in the workplace. Social Science & Medicine, 51(1), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00431-1.

- Dixon, A. J., & Dixon, B. F. (2004). of skin and ocular malignancy. The Medical Journal of Australia, 181(3), 155–157. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb06207.x.

- Dorman, P. (2000). The Economics of Safety, Health, and Well-Being at Work : An Overview. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---safework/documents/publication/wcms_110382.pdf

- Driscoll, T., Rushton, L., Hutchings, S. J., Straif, K., Steenland, K., Abate, D., … Lim, S. S. (2020). Global and regional burden of disease and injury in 2016 arising from occupational exposures: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 77(3), 133–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed–2019–106008

- Drummond, M. F., Sculpher, M. J., Torrance, G. W., O’brien, B. J., & Stoddart, G. L. (2005). Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford University Press.

- Druss, B. G., Schlesinger, M., & Allen, H. M. (2001). Depressive symptoms, satisfaction with health care, and 2-year work outcomes in an employed population. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(5), 731–734. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.731.

- Edington, D. W. (2001). Emerging Research: A View from One Research Center. American Journal of Health Promotion, 15(5), 341–49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-15.5.341

- Fayad, R., Nuwayhid, I., Tamim, H., Kassak, K., & Khogali, M. (2003). Cost of work-related injuries in insured workplaces in Lebanon. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 81(7), 509–516. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1590/S0042-96862003000700009

- Ghana Health Service. (2017). The Health Sector In Ghana Facts And Figures. Accra, Ghana: Ghana Health Service. Retrieved from https://www.ghanahealthservice.org/downloads/FACTS+FIGURES_2017.pdf

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2014). Ghana Living Standards Survey (GLSS6). Accra, Ghana: Ghana Statistical Service.

- Goodchild, M., Sanderson, K., Nana, G. (2002). Measuring the total cost of injury in New Zealand: a review of alternative cost methodologies. Report to The Department of Labour: BERL#4171. Wellington, New Zealand: Business and Economic Research Limited

- Greenberg, M. I., & Vearrier, D. (2015). Metal fume fever and polymer fume fever. Clinical Toxicology, 53(4), 195–203. https://doi.org/10.3109/15563650.2015.1013548.

- Gunderson, M. (2002). Rethinking productivity from a workplace perspective. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Policy Research Networks. Discussion Paper W17. Retrieved from: http://www.cprn.org/documents/123

- Halvani, G., Fallah, H., Hokmabadi, R., Smaeili, S., Dabiri, R., Sanei, B., & Saberi, A. (2014). Ergonomic assessment of work related musculoskeletal disorders risk in furnace brickyard workers in Yazd. Journal of North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, 6(3), 543–550. https://doi.org/10.29252/jnkums.6.3.543.

- Hamalainen, P., Takala, J., & Saarela, K. (2017). Global Estimates of Occupational Accidents and Work-related Illness. 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2005.08.017.

- Hisey, D. A. S. (2014). Welding electrical hazards: an update. Welding in the World, 58(2), 171–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40194-013-0103-x.

- Hong, T. S., & Ghobakhloo, M. (2014). Safety and security conditions in welding processes. In Comprehensive Materials Processing, 6, 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-096532-1.00608-7.

- International Labour Organization. (2013). The Prevention of Occupational Diseases: World Day for Safety and Health at Work. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-386454-3.00617-5.

- Keogh, J. P., Nuwayhid, I., Gordon, J. L., & Gucer, P. W. (2000). The impact of occupational injury on injured worker and family: outcomes of upper extremity cumulative trauma disorders in maryland workers. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 38 (5), 498–506. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0274(200011). 38:5<498::AID-AJIM2>3.0.CO;2-I.

- Kim, Y., Park, J., & Park, M. (2016). Creating a culture of prevention in occupational safety and health practice. Safety and Health at Work, 7(2), 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2016.02.002.

- Korczynski, R. E. (2000). Occupational health concerns in the welding industry. Applied Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 15(12), 936–945. https://doi.org/10.1080/104732200750051175.

- Kumar, S. G, & Dharanipriya, A. (2014). Prevalence and pattern of occupational injuries at workplace among welders in coastal south India. Indian Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 18(3), 135–139. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5278.146911.

- Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly. (2010). Kumasi metropolitan assembly medium term development plan, 2010-2013. kma.gov.gh/kma/?planning.

- Lagomarsino, G., Garabrant, A., Adyas, A., Muga, R., & Otoo, N. (2012). Moving towards universal health coverage: health insurance reforms in nine developing countries in Africa and Asia. The Lancet, 380(9845), 933–943. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61147-7.

- Lanoie, P. (1991). Occupational safety and health: A problem of double or single moral hazard. Journal of Risk and Insurance, 58(1), 80–100. https://doi.org/10.2307/3520049.

- Lebeau, M., & Dugua, P. (2013). The costs of occupational injuries: A review of the literature. Montréal, Québec: Institut de recherche Robert-Sauvé en santé et en sécurité du travail. Retrieved from https://www.irsst.qc.ca/media/documents/PubIRSST/R-787.pdf%5Cnhttp://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle:Studies+and+Research+Projects#0

- Lebeau, M., Duguay, P., & Boucher, A. (2014). Costs of occupational injuries and diseases in Québec. Journal of Safety Research, 50, 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2014.04.002.

- Lee, J. M., Botteman, M. F., Xanthakos, N., & Nicklasson, L. (2005). Needlestick injuries in the United States. epidemiologic, economic, and quality of life issues. AAOHN Journal: Official Journal of the American Association of Occupational Health Nurses, 53(3), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/216507990505300311.

- Leigh, J. P., Markowitz, S. B., Fahs, M., Shin, C., & Landrigan, P. J. (1997). Occupational injury and illness in the United States. estimates of costs, morbidity and mortality. Archives of Internal Medicine, 157(14), 1557–1568. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1997.00440350063006.

- Leigh, J. P., Waehrer, G., Miller, T. R., & Keenan, C. (2004). Costs of occupational injury and illness across industries. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 30(3), 199–205. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.780.

- Leigh, P. J., Markowitz, S., Fahs, M., & Landrigan, P. (2000). Costs of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses. Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

- Lipsey, R. G. (1996). Economic growth, technological change, and canadian economic policy. Toronto, Canada: C.D.Howe Institute. Retrieved from Accessed on September 4th, 2017. https://www.cdhowe.org/speeches-and-presentations/economic-growth-technological-change-and-canadian-economic-policy.

- Lombardi, D. A., Pannala, R., Sorock, G. S., Wellman, H., Courtney, T. K., Verma, S., & Smith, G. S. (2005). Welding related occupational eye injuries: A narrative analysis. Injury Prevention, 11(3), 174–179. https://doi.org/10.1136/ip.2004.007088.

- Maumbe, B. M., & Swinton, S. M. (2003). Hidden health costs of pesticide use in zimbabwe’s smallholder cotton growers. Social Science & Medicine, 57(9), 1559–1571. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00016-9.

- Mehrifar, Y., Zamanian, Z., & Pirami, H. (2019). Respiratory exposure to toxic gases and metal fumes produced by welding processes and pulmonary function tests. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 10(1), 40–49. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijoem.2019.1540.

- Miller, T. R., & Galbraith, M. (1995). Estimating the costs of occupational injury in the United States. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 27(6), 741–747. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-4575(95)00022-4.

- National Safety Council. (1992). Accident prevention manual For Business and industry. John Wiley.

- Niu, S. (2010). Ergonomics and occupational safety and health: an ILO perspective. Applied Ergonomics, 41(6), 744-753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2010.03.004.

- Okuga, M., Mayega, R. W., & Bazeyo, W. (2012). Small-scale industrial welders in jinji municipality, Uganda - awareness of occupational hazards and use of safety measures. African Newsletter on Occupational Health and Safety, 22(2), 43–45. Retrieved from http://www.riskreductionafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/AfricanNewsletter2_2012

- Olsen, J., Christensen, K., Murray, J., & Ekbom, A. (2010). The Cross-Sectional Study. In An Introduction to Epidemiology for Health Professionals. Springer Series on Epidemiology and Public Health (pp. 79). Springer. New York, NY: Springer. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1497-2_11

- Oppong, S. (2014). Common health, safety and environmental concerns in upstream oil and gas sector: implications for HSE management in Ghana. Academicus International Scientific Journal, (9), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.7336/academicus.2014.09.07.

- Raphela, S. F. (2015). Occupational injuries among workers in a welding company within mangaung metropolitan municipality. Occupational Health Southern Africa, 21(4), 4–9. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/11462/1471

- Riccelli, M. G., Goldoni, M., Poli, D., Mozzoni, P., Cavallo, D., & Corradi, M. (2020). Welding fumes, a risk factor for lung diseases. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2552. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072552.

- Rothwell, C. (2012). Ergonomics guide for welders. San Diego, USA: Navy Ergonomics Working Group. Retrieved from: Accessed on June 19, 2016. https://www.navfac.navy.mil.

- Safe Work Australia. (2015). The cost of work-related injury and illness for Australian employers, workers and the community: 2012-2013. Canberra, Australia: Safe Work Australia.

- Shahriyari, M., Afshari, D., & Latifi, S. M. (2018). Physical workload and musculoskeletal disorders in back, shoulders and neck among welders. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 0(0), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2018.1442401.

- Shalini, R. T. (2009). Economic cost of occupational accidents: evidence from a small island economy. Safety Science, 47(7), 973–979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2008.10.021.

- Spaan, E., Mathijssen, J., Tromp, N., McBain, F., Ten Have, A., & Baltussen, R. (2012). The impact of health insurance in Africa and Asia: A systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 90(9), 685–692. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.12.102301.

- Suglo, R., & Gyimah, P. (2014). Estimating the cost of industrial accidents at titaa mining ltd ., Jakpong. UMaT biennial international mining and mineral conference, 1 (July 2014), 178–186. Tarkwa, Ghana: The University of Mines and Technology. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.2159.9047

- Tadesse, S., Bezabih, K., Destaw, B., & Assefa, Y. (2016). Awareness of occupational hazards and associated factors among welders in Lideta Sub-City, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology, 11(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12995-016-0105-x.

- Tagurum, Y. O., Gwomson, M. D., Yakubu, P. M., Igbita, J. A., Chingle, M. P., & Chirdan, O. O. (2018). Awareness of occupational hazards and utilization of PPE amongst welders in Jos metropolis, Nigeria. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 6(7), 2227. https://doi.org/10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20182808.

- Takala, J., Hämäläinen, P., Saarela, K. L., Yun, L. Y., Manickam, K., Jin, T. W., … Lin, G. S. (2014). Global estimates of the burden of injury and illness at work in 2012. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 11(5), 326–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/15459624.2013.863131.

- Targoutzidis, A. (2011). An Investigation of the economic perspective in modeling occupational risk. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing and Service Industries, 21(1), 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/hfm.20215.

- UN-Habitat. (2016). Enhancing Productivity in the Urban Informal Economy. Nairobi, Kenya: UN-Habitat.

- United Nations. (2015). Sustainable Development Goals and Targets. New York, USA: United Nations.

- Uzun, O., Ince, O., Bakalov, V., & Tuna, T. (2012). Massive hemoptysis due to welding fumes. Respiratory Medicine Case Reports, 5(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmedc.2012.01.001.

- Warch, S. L. (2002). Quantifying The Financial Impact of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses, and the Costs and Benefits Associated with an Ergonomic Risk Control Intervention within the Unapprised Business Segment Of United Health Group (Doctoral dissertation, University of Wisconsin).

- World Health Organization. (1995). Global Strategy on occupational health for all: The way to health at work. Recommendations of the Second Meeting of the WHO Collaborating Centres in Occupational Health. 1994 Oct 11–14. Geneva: Switzerland.

- Xu, Y., Li, H., Hedmer, M., Hossain, M. B., Tinnerberg, H., Broberg, K., & Albin, M. (2017). Occupational exposure to particles and mitochondrial DNA - relevance for blood pressure. Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source, 16(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-017-0234-4.

- Z’gambo, J. (2015). A masters thesis submitted to university of Bergins, Norway. Occupational Hazards and Use of Personal Protective Equipment among Small Scale Welders in Lusaka. Retrieved from: Accessed on 13th May, 2019. http://bora.uib.no/bitstream/handle/1956/10194/133483529.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y