Abstract

Parental distress is a major issue in pediatric oncology. The literature shows that intervention programs aimed at supporting parents are effective in reducing parental distress following their child’s cancer diagnosis. However, most programs bear limitations, most often related to their focus on the individual (rather than the family), and their dissemination possibilities. TAKING BACK CONTROL TOGETHER is an integrative program which was developed to respond to these limitations and take the best of effective existing components. In line with development standards from behavioral medicine (ORBIT model), this 6-sessions program aims to reduce parental distress by reinforcing both Problem Solving Skills Techniques (PSST) in 4 individual sessions and communication within the couple and dyadic coping in 2 sessions with the parent couple. The program was first developed in French-language and is now being adapted in English. Because the program addresses both individual PSST and dyadic coping, it is expected to yield more benefits for parents than existing interventions. After this first phase of definition, the program should be pre-tested for refinement, and pilot-tested. This article aims to present the definition of this program, including handbooks for caregivers and parents, as well as worksheets and electronic resources.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Pediatric cancer is associated with significant sources of stress for both the children and their families. Medical and Psychosocial research strongly suggest that supporting parents is crucial to promote adjustment in parents and in children. Therefore, researchers have developed and evaluated psychological intervention programs to systematically support parents. Those of high-quality and high pertinence train parents in problem-solving techniques and promote better communication within the couple. This article aims to present the design of a new program combining existing procedures and building on their successes, TAKING BACK CONTROL TOGETHER. This new intervention program aims to target emotional distress in the couple of parents and strengthen their sense of unity, by promoting their regaining control over the dramatic situation they are facing. The program will facilitate their coping with cancer as well as promoting a clearer view of what they can do to deal with practical difficulties. We hope that the intervention will yield better emotional outcomes in parents in the short and longer term.

1. Introduction

Studies conducted with parents of a child with cancer have shown high levels of stress, emotional distress and loss of control immediately after the diagnosis, during treatment, and over the long term (Picoraro et al., Citation2014; Sultan et al., Citation2016; Vrijmoet-Wiersma et al., Citation2008). Studies also showed an impact of childhood cancer on both healthy and dysfunctional parental relationships. Long periods of illness were associated with parental resource depletion, weaker support, and a reduced sense of cohesion (Mongeau et al., Citation2006). As a result, tensions, separations and even divorces are strongly correlated with the severity of the child’s health status (Statistique Canada, Citation2008a). Acute parental distress at the time of diagnosis and during treatment is a risk factor for long-term psychological and relationship distress in parents and has been associated prospectively with children’s coping difficulties during and after treatment, as well as with impaired school functioning at the end and after treatment (Barrera et al., Citation2008; Maurice-Stam et al., Citation2008; Yagci-Kupeli et al., Citation2012). Therefore, it is crucial to address parental distress as soon as possible in order to optimize the resilience of families confronted with childhood cancer and to reduce long-term pervasive effects of childhood cancer on parents and children.

The majority of professional services offered to address parental distress in pediatric cancer settings suffers from a number of issues, including the fact that less than 11% of psychological services have implemented evidence-based treatments (Kazak et al., Citation2015). However, it is essential to offer patients the most effective intervention programs evaluated by rigorous studies, as is the case in pharmacology for drug development (Craig et al., Citation2008; Czajkowski et al., Citation2015). The Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR) and Canadian Cancer Society stressed the importance of developing behavioral treatments to prevent or manage chronic diseases (Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research., Citation2011; Canadian Cancer Society, Citation2017). These organizations’ recommendations are in line with recent research and suggest identifying innovative approaches to solve significant clinical problems based on theory and research in behavioral science.

In a recent systematic and critical literature review, we identified 11 manualized programs to support parents of children with cancer (D. Ogez, Péloquin et al., Citation2019). Studies conducted on these programs showed that they were designed according to various models of change including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), psycho-education, and family therapy. The review revealed that therapeutic procedures were generally appropriately chosen and that their development process followed established guidelines for the development of behavioral interventions. Pre-post-follow-up distress reduction studies were available for 8/11 programs and quasi-experimental Randomized Control Trials (RCTs) were performed for 7/11 programs. Importantly, not all programs documented processes followed for concept design and refinement.

Only two programs were evaluated in well-designed studies that followed the standard phases of behavioural interventions development and were recommended by the NCI: Bright IDEAS and Surviving Cancer Competently Intervention Program (SCCIP) (Kazak et al., Citation1999; Sahler et al., Citation2013). Bright IDEAS is based on Problem Solving Skills Therapy (PSST) and aims at fostering effective problem-solving skills in mothers (Nezu et al., Citation2013; Sahler et al., Citation2002). This 8-session individually based program involves the teaching of a 5-step problem-solving process: 1- Problem identification; 2- Problem definition; 3- Solutions evaluation; 4- Solution implementation; 5- Assessment of its effectiveness. Although Bright IDEAS has excellent NCI scores on dissemination (5/5) and research integrity (4.4/5), this program still bears limitations. However, Bright IDEAS received a limited impact score (2/5) because it is only offered to mothers on an individual basis, is relatively burdensome and somewhat repetitive (8 face-to-face sessions), and has a high dropout rate (42%) (National Cancer Institute, Citationn.d.).

The second program, SCCIP, is based on the principles of CBT and family therapy (Kazak et al., Citation1999). This program consists of family interventions that focus on improving intrafamily communication and calls for different activities: the multiple family discussion group, which proposes a group discussion to clarify parental functions, and the family-oriented approach to help families cope with cancer (Kazak & Simms, Citation1996; Ostroff et al., Citation2004). SCCIP has received fair NCI scores on research integrity (3.6/5) and dissemination (4/5), but a lower score on impact (1.3/5). This later score may be explained by lower effect sizes in efficacy studies (Institute). Moreover, the manual is very general because of the complexity of communicative interventions in the family, and lacks important details on the specific interventions to be carried out. Thus, it is difficult for professionals to use the interventions prescribed by the program in a systematic way. Of note, Bright IDEAS was developed in two languages (English and Spanish), and SCCIP only in English. Like the vast majority (8/11) of available interventions, these programs were developed for a North American population, which raises questions about the transferability to other cultural or language contexts (David Ogez et al., Citation2019).

With reference to the results of this critical review, we developed a new intervention program in order to appropriately respond to needs of parents who are faced with pediatric cancer. This program is specifically based on the advantages and the limits identified in previous programs and follows recommendations on behavioral treatments development (Czajkowski et al., Citation2015). In developing our program, our goal was to capitalize on previous evidence-based interventions and articulate one individual component based on PSST and one couple component based on a CBT- systemic approach. This paper presents the definition of the program TAKING BACK CONTROL TOGETHER (in French: Reprendre le Contrôle Ensemble). Specifically, we describe 1- the procedure followed to define the concept of the program based on previous programs and 2- the intervention’s content and material: manuals, paper and electronic tools.

2. Methods

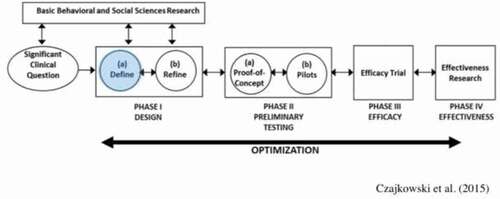

The developmental process of TAKING BACK CONTROL TOGETHER followed recommendations that formalize behavioral treatments development. The Obesity-Related Behavioral Intervention Trials (ORBIT), initially developed within the framework of an obesity management program, is a comprehensive behavioral program evaluation model that explicitly describes the preliminary stages of program development. This model recommends four phases of behavioral intervention program development: I- program definition phase, II- preliminary tests, III- Efficacy studies and, IV-Effectiveness studies (Czajkowski et al., Citation2015). The definition phase includes two steps: the definition (Ia) and the refinement (Ib) of the design ().

With the aim of defining this new program, we focused on Orbit’s stage Ia. Firstly, we conducted a systematic review of intervention programs that resulted in: 1-formulating a definition of the target population, 2- selecting the program’s primary and secondary intervention targets, 3- justifying our choice of models of change and their translation into interventional procedures, and 4- formulating a coherent program comprising these procedures (Ogez, Bourque et al., Citation2019). Secondly, three researchers and clinicians from the University of Montreal (Québec, Canada), bringing together skills in psychology, oncology, pediatrics, cognitive-behavioral and couple therapies (DO, KP, SS), were involved in defining the concept of the program TAKING BACK CONTROL TOGETHER. The program’s objectives and conceptual framework were established following training of the team members in the two programs highlighted in our review—Bright IDEAS and SCCIP—and meetings with core authors in the last three years (Kazak et al., Citation1999; Sahler et al., Citation2013). Finally, in order to systematize this intervention’s administration, we created a manual for practitioners and parents, as is standard practice in behavioral sciences (National Cancer Institute, Citationn.d.). summarizes each stage of this program’s definition.

Table 1. Definition of the program taking back control together

3. Program definition

3.1. Target population

Most authors in this field stress the importance of supporting both parents, echoing studies that observed similar long-term levels of distress in mothers and fathers at the end of their child’s treatment (Maurice-Stam et al., Citation2008). Studies have also shown that the couple’s intimacy, sexuality, time, and activities are negatively impacted by cancer (Burns et al., Citation2018). This distress can even lead to separations and divorces, strongly correlated with the severity of the child’s health condition (Statistique_Canada, Citation2008b). Previous research suggests that parents who are better able to function as a team under stressful conditions by developing better dyadic coping are better able to cope with major stressors, including their child’s illness (G. Bodenmann et al., Citation2006; G Bodenmann & Shantinath, Citation2004). To address parental distress, it is therefore important to support individuals as part of their relationship and to promote unity and relationship adjustment to optimize the individual adjustment of each partner. Yet, despite this recommendation, very few intervention programs target both parent couple. In rare cases, couple or family programs include fathers (Cernvall et al., Citation2017; Kazak et al., Citation2005; Manne et al., Citation2016).

Addressing this limitation, the present program equally targets mothers and fathers, and use individual as well as couple intervention modalities. In order to address the needs of both mothers and fathers, we offered individual sessions independently to both parents. We also included single-parent families to whom we offer only individual sessions. Moreover, to address the lack of French-language interventions, the program was developed in international French and draws on the team’s language competencies.

3.2. Program targets

In oncology, research highlighted the importance of treating anxiety and depression in cancer patients and their family (Kangas, Citation2015). Previous programs in pediatric oncology have targeted psychological distress, depression, post-traumatic stress (PTS), quality of life, and perception of uncertainty. In regard to Bright IDEAS and SCCIP, their intervention targets were emotional distress in mothers and PTS in family, respectively. In most programs, these targets were understood as being the result of parental overload (e.g., child support, financial difficulties) in the pediatric cancer context (Manne, Citation2016; Mullins et al., Citation2012; Sahler et al., Citation2013). Interventions thus aimed to reduce feelings of parental overload through mediator targets and foster parents’ optimal involvement in the medical care of their child. As such, improving problem-solving skills led to a reduction of negative affectivity and parental distress, while decreasing the perception of uncertainty led to a reduction of parents’ stress levels (Sahler et al., Citation2013, Citation2005; Santacroce et al., Citation2010) . SCCIP’s efficacy evaluation also showed very positive results on relationship and family well-being (Kazak et al., Citation1999).

Based on these results, we chose self-reported parental emotional distress as the primary target of TAKING BACK CONTROL TOGETHER. In line with studies on previous programs, we also chose three secondary process targets (mediators) for which evidence strongly suggests an effect on individual emotional distress: problem-solving skills, couple communication, and dyadic coping (Kazak et al., Citation1999; Sahler et al., Citation2013). That is, intervening on these process targets was expected to reduce perceived emotional distress in parents.

3.3. Models of change and activities

We chose models of change and activities that are likely to reduce distress through the modification of the secondary process targets (mediators). First, consistent with Bright Ideas’ model of change, we chose to offer problem-solving training (Nezu et al., Citation2013). Pilot studies’ results and Bright IDEAS’ RCTs showed a significant decrease in distress and improved problem-solving skills in mothers post-treatment and at 3 months follow-up for participants in the intervention program compared to the control group (Sahler et al., Citation2013, Citation2005, Citation2002). The significant dropout rate during Bright IDEAS was caused by parents’ refusal to participate and the program’s length (8 sessions), that is—many mothers considered the treatment too long and preferred to spend their time with their child during treatment. To address this limitation, the Brief Problem-Solving Intervention for Parents of Children with Cancer, a short version of Bright IDEAS, which included only 2 sessions, was developed (Lamanna et al., Citation2017). However, this short program yielded no significant effects on parental distress, mostly because it did not allow enough time for problem solving. Balancing considerations for attrition and intervention intensity, we chose to include 4 individual problem-solving training sessions (50% of Bright IDEAS sessions) in TAKING BACK CONTROL TOGETHER.

Second, we chose to integrate a module focused on couple adjustment in the program based on SCCIP’s systemic orientations which also draws from CBT models of change: coping readjustment centered on the change of beliefs that each family member has about cancer (Kazak et al., Citation1999). This model of change has been used in the majority of existing manualized intervention programs for parents of children with cancer (7/11 programs) and has been found to significantly reduce parents’ distress and improve their quality of life (Kazak et al., Citation1999; Ogez et al., Citation2019). SCCIP and its revised version, Surviving Cancer Competently Intervention Program Newly Diagnosed (SCCIP-ND) have been evaluated in RCTs, which have shown beneficial effects on relationship and family well-being, as well as significant improvements in parental distress (Kazak et al., Citation2005, Citation1999). Accordingly, TAKING BACK CONTROL TOGETHER includes two couple sessions during which activities are designed to foster positive stress communication between partners and enhance dyadic coping by encouraging parents to work as a team (G Bodenmann & Shantinath, Citation2004; Kazak et al., Citation1999). Interventions targeting dyadic coping consist of supporting one or both partners to engage in a stress management process that aims to create or restore physical, psychological or social homeostasis in both partners individually and within the couple as a unit (G Bodenmann & Shantinath, Citation2004). In line with previous research on resilience in couples faced with pediatric cancer, our couple module aims to improve couples’ resilience by 1- supporting partners’ sense of we-ness, 2- helping partners to gain a common vision of the pediatric cancer context, and 3- fostering the implementation of a collaborative dynamic within the couple (Martin et al., Citation2014).

The program sessions in TAKING BACK CONTROL TOGETHER are conducted by a health practitioner (social worker, nurse, psychologist, etc.). The first individual session and the couple sessions last one hour and a half to allow time for the initial contact, to introduce the program, and to share information on the disease and its treatments. The other individual sessions, (3 and 4) last one hour. Home tasks are also required between each session and are related to the practice of problem-solving techniques acquired during individual and couple sessions, and the practical implementation of identified solutions.

To provide an easily transferable program, TAKING BACK CONTROL TOGETHER was manualized. A manual for health practitioners presents specific instructions for each intervention to be used in all program sessions and numerous examples of transcripts to convey the information to parents adequately and in a standardized manner (64 pages). The program also includes a manual for parents (28 pages), a problem-solving toolkit for individual and couple sessions, and two videos illustrating 1- an example of problem solving and 2- relationship challenges in the context of pediatric cancer through interviews with couples. These documents and tools can be accessed free of charge through our web platform after registration (www.cpo-montreal.com). Given the usefulness of having electronic versions of intervention programs, we also propose a simple and easily accessible electronic platform for parents that provides access to all program resources in electronic version as well as videos summarizing each program sessions (Askins et al., Citation2009; Cernvall et al., Citation2017; Wakefield et al., Citation2016).

4. Conclusion

Our team of researchers and clinicians in pediatric oncology developed the program TAKING BACK CONTROL TOGETHER to better support parents during their child’s treatment. To carry out this project, we followed recommendations for designing behavioral interventions and requirements for evidenced-based interventions in this field (Czajkowski et al., Citation2015). To define this new intervention, we relied on a careful analysis of previous experiences and identified gaps.

The definition of the intervention program is an important and integral part of the intervention development stages (Czajkowski et al., Citation2015). According to recommendations for the development of health care intervention program, it is essential to develop new interventions in oncology based on previous studies and taking the best evidence-based therapeutic procedures available (Ownsworth et al., Citation2015). Research on interventions program development is currently in agreement with studies in pharmacology on drugs (Craig et al., Citation2008). Therefore, it must be organized and follow strict protocols. Its main function is to significantly improve therapeutic procedures and their articulations in intervention programs.

Following this definition step, our next tasks on this program was to refine its content and format with end-users in a qualitative inquiry. The program, manuals and tools was presented to parents who have experienced their child’s cancer and to healthcare professionals to be evaluated and criticized (D. Ogez, Bourque et al., Citation2019). Next, we will be in a position to lead a full pilot study, to assess the program’s acceptability, feasibility and treatment fidelity. As the TAKING BACK CONTROL TOGETHER program draws on the best evidence and an explicit and coherent model of change and activities, we expect this intervention to yield a clear clinical signal on the primary outcome of emotional distress and process outcomes, i.e. problem-solving skills, impact of cancer on couple communication and dyadic coping.

In reference to previous studies, we have developed TAKING BACK CONTROL TOGETHER which enhances procedures and formats of existing manualized programs. Following efficacy testing, we hope to provide the clinical community with a new and more effective program that will reduce parents’ emotional overload and thus improve the quality of life of families in pediatric oncology.

Notes on contributors

DO, SS, KP developed the intervention program and wrote the manuscript. SS, KP supervised the project. All authors helped write the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interests statement

The authors state that they have no interests, which may be perceived as posing conflict or bias.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Charles-Bruneau Cancer Care Centre Foundation; the CHU Sainte-Justine Foundation; the Fonds de la Recherche du Québec – Santé (FRQs).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

David Ogez

David Ogez, PhD is a clinical psychologist and associate professor in Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine at the University of Montreal. This project was conducted during his post-doctoral fellow at the University of Montréal and the Centre of Psycho-Oncology at Sainte-Justine University Health Centre. Serge Sultan, PhD, is full professor in psychology and pediatrics at the University of Montreal and heads the Centre of Psycho-Oncology. Katherine Péloquin is associate professor in psychology at the same university. Other co-authors are members of an interdisciplinary project designed to optimize quality of life of families confronted with pediatric cancer during the treatment phase. The interdisciplinary team is led by Daniel Sinett, PhD, full professor in pediatrics in the same university and head of research at the CIUSSS Nord-de-l’île-de-Montréal.

References

- Askins, M. A., Sahler, O. J., Sherman, S. A., Fairclough, D. L., Butler, R. W., Katz, E. R., Dolgin, M. J., Varni, J. W., Noll, R. B., & Phipps, S., & ADDIN EN.REFLIST. (2009). Report from a multi-institutional randomized clinical trial examining computer-assisted problem-solving skills training for English- and Spanish-speaking mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34(5), 551–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsn124

- Barrera, M., Atenafu, E., Andrews, G. S., & Saunders, F. (2008). Factors related to changes in cognitive, educational and visual motor integration in children who undergo hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 33(5), 536–546. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsm080

- Bodenmann, G., Pihet, S., Shantinath, S. D., Cina, A., & Widmer, K. (2006). Improving dyadic coping in couples with a stress-oriented approach: A 2-year longitudinal study. Behavior Modification, 30(5), 571–597. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445504269902

- Bodenmann, G., & Shantinath, S. D. (2004). The Couples Coping Enhancement Training (CCET): A new approach to prevention of marital distress based upon stress and coping. Family Relations, 53(5), 477–484. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0197-6664.2004.00056.x

- Burns, W., Péloquin, K., Émélie, R., Drouin, S., Bertout, L., Lacoste-Julien, A., … Sultan, S. (2018). Cancer-related effects on relationships, long-term psychological status and relationship satisfaction in couples whose child was treated for leukemia: A PETALE study.

- Cernvall, M., Carlbring, P., Wikman, A., Ljungman, L., Ljungman, G., & von Essen, L. (2017). Twelve-Month follow-Up of a randomized controlled trial of internet-based guided self-Help for parents of children on cancer treatment. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(7), e273. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6852

- Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M., & Medical Research Council, G. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new medical research council guidance. BMJ, 337, a1655. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1655

- Czajkowski, S. M., Powell, L. H., Adler, N., Naar-King, S., Reynolds, K. D., Hunter, C. M., Laraia, B., Olster, D. H., Perna, F. M., Peterson, J. C., Epel, E., Boyington, J. E., & Charlson, M. E. (2015). From ideas to efficacy: The ORBIT model for developing behavioral treatments for chronic diseases. Health Psychology, 34(10), 971–982. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000161

- Kangas, M. (2015). Psychotherapy interventions for managing anxiety and depressive symptoms in adult brain tumor patients: A scoping review. Frontiers in Oncology, 5, 116. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2015.00116

- Kazak, A. E., & Simms, S. (1996). Family systems intervention in neuropediatric disorders In C. In Cofee & R. Brumback (Eds.), Textbook of pediatric neuropsychiatry (pp. 114–1464). American Psyhiatric Press.

- Kazak, A. E., Abrams, A. N., Banks, J., Christofferson, J., DiDonato, S., Grootenhuis, M. A., Kabour, M., Madan-Swain, A., Patel, S. K., Zadeh, S., & Kupst, M. J. (2015). Psychosocial assessment as a standard of care in pediatric cancer. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 62(Suppl 5), S426–459. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.25730

- Kazak, A. E., Simms, S., Alderfer, M., Rourke, M., Crump, T., McClure, K., Jones, P., Rodriguez, A., Boeving, A., Hwang, W.-T., & Reilly, A. (2005). Feasibility and preliminary outcomes from a pilot study of a brief psychological intervention for families of children newly diagnosed with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 30(8), 644–655. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsi051

- Kazak, A. E., Simms, S., Barakat, L., Hobbie, W., Foley, B., Golomb, V., & Best, M. (1999). Surviving cancer competently intervention program (SCCIP): A cognitive-behavioral and family therapy intervention for adolescent survivors of childhood cancer and their families. Family Process, 38(2),175–191. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://MEDLINE: 10407719. . https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.1999.00176.x

- Lamanna, J., Bitsko, M., & Stern, M. (2017). Effects of a brief problem-solving intervention for parents of children with cancer. Children’s Health Care,47(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02739615.2016.1275638

- Manne, S. (2016). Parent Social-Cognitive processing intervention program: P-SCIP.

- Manne, S., Mee, L., Bartell, A., Sands, S., & Kashy, D. A. (2016). A randomized clinical trial of a parent-focused social-cognitive processing intervention for caregivers of children undergoing hematopoetic stem cell transplantation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(5), 389–401. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000087

- Martin, J., Péloquin, K., Flahault, C., Muise, L., Vachon, M. F., & Sultan, S. (2014). Vers un modèle de la résilience conjugale des parents d’enfants atteints par le cancer. Psycho-Oncologie, 8(4), 222–229. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11839-014-0488-9

- Maurice-Stam, H., Oort, F. J., Last, B. F., & Grootenhuis, M. A. (2008). Emotional functioning of parents of children with cancer: The first five years of continuous remission after the end of treatment. Psycho-Oncology, 17(5), 448–459. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1260

- Mongeau, S., Champagne, M., & Carignan, P. (2006). Au-delà du répit … un message de solidarité. Les cahiers de soins palliatifs, 6(2), 81–103.

- Mullins, L. L., Fedele, D. A., Chaffin, M., Hullmann, S. E., Kenner, C., Eddington, A. R., Phipps, S., & McNall-Knapp, R. Y. (2012). A clinic-based interdisciplinary intervention for mothers of children newly diagnosed with cancer: A pilot study. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 37(10), 1104–1115. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jss093

- National Cancer Institute NCI (n.d.). https://rtips.cancer.gov/rtips/index.do

- Nezu, A. M., Nezu, C. M., & D’Zurilla, T. (2013). Problem-Solving therapy:. Springer.

- Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. (2011). Translating basic behavioral and social science discoveries into interventions to improve health-related behaviors (R01). http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PA-11-063.html

- Ogez, D., Bourque, C. J., Peloquin, K., Ribeiro, R., Bertout, L., Curnier, D., Drouin, S., Laverdière, C., Marcil, V., Rondeau, É., Sinnett, D., & Sultan, S. (2019). Definition and improvement of the concept and tools of a psychosocial intervention program for parents in pediatric oncology: A mixed-methods feasibility study conducted with parents and healthcare professionals. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 5(1), 20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-019-0407-8

- Ogez, D., Péloquin, K., Bertout, L., Bourque, C. J., Curnier, D., Drouin, S., Laverdière, C., Marcil, V., Ribeiro, R., Callaci, M., Rondeau, E., Sinnett, D., & Sultan, S. (2019). Psychosocial intervention program for parents of children with cancer: A systematic review and critical comparison of programs’ models and development. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 26(4), 550–574. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-019-09612-8

- Ostroff, J., Ross, S., Steinglass, P., Ronis-Tobin, V., & Singh, B. (2004). Interest in and barriers to participation in multiple family groups among head and neck cancer survivors and their primary family caregivers. Family Process, 43 (2), 195–208. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15603503. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.04302005.x.

- Ownsworth, T., Chambers, S. K., & Dhillon, H. M. (2015). Editorial: Psychosocial advances in Neuro-Oncology. Frontiers in Oncology, 5, 243. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2015.00243

- Picoraro, J. A., Womer, J. W., Kazak, A. E., & Feudtner, C. (2014). Posttraumatic growth in parents and pediatric patients. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 17(2), 209–218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2013.0280

- Sahler, O. J., Dolgin, M. J., Phipps, S., Fairclough, D. L., Askins, M. A., Katz, E. R., Noll, R. B., & Butler, R. W. (2013). Specificity of problem-solving skills training in mothers of children newly diagnosed with cancer: Results of a multisite randomized clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31(10), 1329–1335. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.39.1870

- Sahler, O. J., Fairclough, D. L., Phipps, S., Mulhern, R. K., Dolgin, M. J., Noll, R. B., Katz, E. R., Varni, J. W., Copeland, D. R., & Butler, R. W. (2005). Using problem-solving skills training to reduce negative affectivity in mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: Report of a multisite randomized trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(2), 272–283. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.272

- Sahler, O. J., Varni, J. W., Fairclough, D. L., Butler, R. W., Noll, R. B., Dolgin, M. J., Phipps, S., Copeland, D. R., KATZ, E. R., & Mulhern, R. K. (2002). Problem-solving skills training for mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: A randomized trial. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 23(2), 77–86. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00004703-200204000-00003

- Santacroce, S. J., Asmus, K., Kadan-Lottick, N., & Grey, M. (2010). Feasibility and preliminary outcomes from a pilot study of coping skills training for adolescent-young adult survivors of childhood cancer and their parents. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 27(1), 10–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454209340325

- Canadian Cancer Society. (2017). http://www.cancer.ca/en/?region=on

- Statistique Canada. (2008a). L’Enquête sur la participation et limitations d’activités de 2006: Familles d’enfants handicapés au Canada. Ottawa.

- Statistique Canada. (2008b). L’Enquête sur la participation et limitations d’activités de 2006: Familles d’enfants handicapés au Canada. Statistique Canada. Ottawa.

- Sultan, S., Leclair, T., Rondeau, E., Burns, W., & Abate, C. (2016). A systematic review on factors and consequences of parental distress as related to childhood cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care, 25(4), 616–637. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12361

- Vrijmoet-Wiersma, C. M., van Klink, J. M., Kolk, A. M., Koopman, H. M., Ball, L. M., & Maarten Egeler, R. (2008). Assessment of parental psychological stress in pediatric cancer: A review. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 33(7), 694–706. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsn007

- Wakefield, C. E., Sansom-Daly, U. M., McGill, B. C., Ellis, S. J., Doolan, E. L., Robertson, E. G., Mathur, S., & Cohn, R. J. (2016). Acceptability and feasibility of an e-mental health intervention for parents of childhood cancer survivors: “Cascade”. Supportive Care in Cancer, 24(6), 2685–2694. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3077-6

- Yagci-Kupeli, B., Akyuz, C., Kupeli, S., & Buyukpamukcu, M. (2012). Health-related quality of life in pediatric cancer survivors: A multifactorial assessment including parental factors. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, 34(3), 194–199. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0b013e3182467f5f