?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

There has been a divergence in the pace of fertility decline between the Muslim-dominated countries of Maghreb and those of Middle/West Africa (despite having similar religious beliefs, which studies have implicated as a major determinant of fertility behaviours). While the Maghreb countries have total fertility rate ranging between 2 and 3, it ranges between 6 and 7 in Muslim-majority countries of Middle/West Africa. Factors other than religion seem to be responsible for this divergent pattern. Evidence is sparse on this. This paper provides empirical evidence on factors influencing divergent pattern in fertility levels of selected Muslim-dominated countries of Maghreb and Middle/West Africa. Based on availability of recent data, this paper drew on Demographic and Health Survey data of three Middle/West Africa countries—Mali (2013–14), Niger (2012) and Northern Nigeria (2013); and two North African countries—Egypt (2014) and Morocco (2003–04). Relationships were explored using Poisson regression models that adjusted for religion and women characteristics. Findings showed that age at first marriage, age at first birth, contraceptive use, child mortality, plurality of marriage and women education are the major drivers of divergence in fertility patterns of the selected countries in both sub-regions. Differences in proximate determinants of fertility played significant roles in shaping the divergent pattern in fertility levels between both sub-regions. Rather than focusing on religion, this study suggests the need for transition in the proximate determinants of fertility in Middle/West African countries, if the sub-region would achieve the desired fertility decline.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Huge variations exist in fertility level of the Muslim-dominated countries of Maghreb and those of Middle/West Africa (MWA), despite their affiliation to the same religion. Drawing on the Demographic and Health Survey data of 3 Middle/West African countries and 2 North African countries, we provide empirical evidence on the drivers of divergent fertility pattern of selected Muslim-dominated countries in the two regions. We found that age at first marriage, age at first birth, contraceptive use, child mortality, plurality of marriage and women education were the major drivers of divergent fertility pattern in the selected countries in both regions. The study concludes that differences in fertility level between the two regions are attributable to women’s characteristics other than their religious affiliation.

1. Introduction

Africa has one of the fastest growing populations, having reached 1 billion people in 2011 (UNFPA, Citation2011). Research has shown that the pace of fertility decline on the continent remains the slowest globally (Bongaarts, Citation2008). Meanwhile, during the era that preceded the first two United Nations’ population conferences held in Bucharest in 1974 and Mexico City in 1984, almost all the countries in Africa had a convergent disposition in respect of fertility. First, at the time of the 1974 conference, 59 countries largely from Europe and North America promoted family planning while African countries intensely stood against it (United Nations, Citation2015). Delegates from African countries noted that development was the best contraceptives. By the time of the second UN’s population conference in Mexico City, 64 countries, including many from Africa, had shifted ground and expressed their firm supports for adoption of population programmes and family planning (United Nations, Citation2015). This translated to a total of 123 countries that supported the need for explicit population policies and programmes. After this conference, most African countries had a convergent disposition towards the adoption of explicit population policies and programmes. For example, the post-1984 era witnessed the adoption of explicit population policies in Kenya, Egypt, Ghana, Ethiopia, Niger, Nigeria, and many other countries in Africa (United Nations, Citation2015).

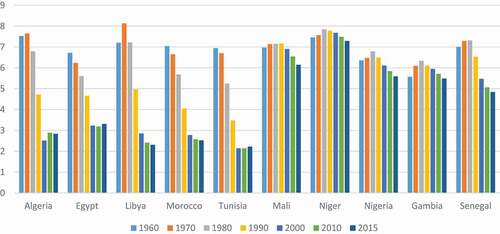

However, the post-ICPDFootnote1 era appeared to have witnessed some divergence in fertility-related behaviours and patterns across countries in Africa. Evidence suggests that the ICPD’s Programme of Action which emphasized a new concept on sexual and reproductive health, reproductive right and women empowerment had reshaped Africa’s research and policy agenda (C. Odimegwu et al., Citation2012), particularly as it concerns fertility-related issues. While the pre- and post-1984 period witnessed a convergent pattern in fertility level and transition in many African countries, the post-1994 era witnessed a divergent trend in fertility decline across the continent (as shown in below). For instance, evidence shows that most Muslim-dominated countries of Maghreb have witnessed a uniform trend in fertility levels and patterns comparable to those of Europe and North America, while other Muslim-majority countries in Middle/West Africa have sustained high fertility regime (World Bank, Citation2018). The fertility levels and patterns of Maghreb countries are quite contrary to the general patterns that exist in many other Muslim-majority countries in Africa, such as Mali, Niger, The Gambia, Senegal, etc.

Figure 1. Fertility transition in selected Muslim-majority sub-Saharan and North African countries

Prior research has implicated adherence to Islamic doctrines as the bane of high fertility regime in Middle/West Africa (Izugbara & Ezeh, Citation2010; Morgan et al., Citation2002). This is because Islam is conventionally deemed as a religion with doctrines that encourage relatively large family size, thus permitting plurality of spouses and tagging abortion and some forms of contraception as haram (i.e. forbidden) (Ilyas et al., Citation2009), amongst other high-fertility enabling factors. However, evidence across many Arab and North African countries where Islam is predominantly practised reveals that majority of these countries have either completed the demographic transition or approaching fertility levels (replacement level) close to those of many European countries. Total fertility rate currently stands at 2.8 in Algeria and Egypt, 2.1 in Morocco and Libya, and 2.0 in Tunisia (World Bank, Citation2010). This fertility scenario seems to contravene the expected reproductive behavior of Muslims, thereby suggesting there are other major contributing factors that shape the fertility level of these countries.

On the other hand and in comparison with the Maghreb countries, the fertility levels and patterns are quite different in the Muslim-majority countries of Middle/West Africa, including Mali, Niger, Somalia and Northern part of Nigeria where total fertility rate currently ranges between 6 and 7 children per woman (World Bank, Citation2010; UNPD, 2016). Evidence from these countries and region indicates a preference for polygyny, plurality of marriage (Omariba & Boyle, Citation2007; Smith-Greenaway & Trinitapoli, Citation2014) and large family size as emphasized and encouraged by the Islamic doctrine. This clearly shows a divergent pattern in fertility levels between the Muslim-dominated countries of Maghreb and those of Middle and West Africa.

Further, in-country variation in fertility level, for instance, between the Muslim-dominated northern Nigeria (with total fertility rate of 7) and Christian-majority south (with total fertility rate of 4) seems to implicate religion as a major driver of the observed differences. The minority-group fertility hypothesis proposed by Goldscheider (Citation1971), which posits that minority groups adjust their fertility in order to protect their status in a society, would have served as a good premise for the Muslim-Christian fertility differentials in Nigeria. However, this scenario does not hold across many countries, as Muslim-dominated countries of Maghreb, for instance, even have slightly lower fertility than many Christian-majority sub-Saharan African countries.

Given that population is the driver of just about everything else and rapid population growth largely worsens environmental degradation, diminishes human capital investment (World Bank, Citation2010a, Citation2010b), exacerbates all kinds of challenges such as poor maternal and child health (Adedini et al., Citation2014; Ononokpono et al., Citation2014), poverty (Barro, Citation1998), pollution (Angelsen & Kaimowitz, Citation1999), as well as rising unrest and crime (Buhaug & Urdal, Citation2013); high fertility and rapid population growth remain a very important health and developmental issue for research and policy. Although fertility transition is underway across countries in Africa, the pace of decline has been too slow or stalled in many Middle/West African countries (Ezeh et al., Citation2009; Garenne, Citation2013) while many countries in North Africa (the Maghreb) have completed or on their way to completing fertility transition. Considering the divergent patterns in fertility levels and trends of Muslim-majority countries of North Africa and Middle/West Africa, despite adherence to similar religious tenets of Islam, this study thus aimed to empirically investigate the factors influencing divergence in fertility levels and patterns of selected Maghreb and Middle/West African countries where Islam is predominantly practised.

2. Conceptualization and theoretical perspectives

Scholars have traditionally cast the conceptualization of religion–fertility relationship within three theoretical models (Agadjanian & Yabiku, Citation2014). As theorized by Goldscheider (Citation1971), the first theoretical model is the particularistic theology, which links religious differences in fertility behaviour to variations in doctrinal beliefs or practices. Such religious tenets tend to approve or disapprove of certain sexual, conjugal, contraceptive or fertility behaviours that directly or indirectly influence fertility level (Agadjanian, Citation2013).

The second model is the minority-group status hypothesis. It advances that religious minority groups adjust their fertility in order to preserve their status in the society. This adjustment could lead to upward or downward change in fertility level (Agadjanian & Yabiku, Citation2014; Hirsch, Citation2008).

The third hypothesis is the characteristics framework, which posits that religious differences in fertility is due to other characteristics such as socio-economic, demographic, or cultural attributes of the adherents of different faiths and denominations. This hypothesis suggests that it is not religion per se that is responsible for fertility differentials, but other characteristics of the individuals, such as their demographic, socio-economic, and cultural attributes. This hypothesis suggests that religious differences in fertility are attributable to women’s characteristics other than their religious affiliation. Some of these characteristics include women’s level of education, employment status, wealth status, etc. (Agadjanian & Yabiku, Citation2014; Hirsch, Citation2008). Arguably, differences in the level of religiosity or adherence to religious beliefs may bring about variations in these characteristics.

Although scholars have argued that Muslims adopt high fertility behaviour in countries where they are minority, as postulated by the minority hypothesis (Agadjanian & Yabiku, Citation2014; Goldscheider, Citation1971; Hirsch, Citation2008); evidence has shown that fertility level is generally higher in Muslim-majority zones or countries of Middle/West Africa (irrespective of whether they are minority or majority) compared to their Christian-dominated counterparts in the same country, even as their fertility rates are also higher than those of their counterparts in the Maghreb. Our study thus builds on the characteristics hypothesis and posits that it is not religious tenets per se that account for fertility differentials between the Muslim-majority Middle/West African countries and those in the Maghreb. Rather, we hypothesize that characteristics other than religion account for the fertility differentials across these countries in the two sub-regions. We posit that generally the level of development and socio-economic status that women attain in a country largely accounts for the differentials in fertility across countries. This hypothesis was tested using Demographic and Health Survey data of five selected countries in the two sub-regions.

3. Data and methods

Based on availability of recent data for countries in Maghreb and Middle/West Africa, data for this study came from Egypt and Morocco (in Maghreb); and Mali, Niger, and Northern Nigeria (in Middle/West Africa). The study drew on the most recent Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data of these countries (i.e. 2014 Egypt DHS, 2013 Nigeria DHS, 2012–13 Mali DHS, 2012 Niger DHS, and 2003–04 Morocco DHS).

Essentially, the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs) employed similar methodology across countries to elicit information on an extensive range of demographic and health issues. This allows for comparability of findings across countries. The DHSs are nationally representative surveys, which employed a cross-sectional study design. Using a two-stage cluster design sampling procedure, primary sampling units (PSU) or enumeration areas in different countries were stratified and samples of PSU were drawn from stratified areas with probability proportional to size. Also, households were sampled from the selected PSUs. Further, eligible women of reproductive ages 15–49 years were randomly selected across the sampled households in different countries. Birth histories data for individuals were collected from women aged 15 to 49 years. The detailed methods and data collection procedures used in respective country surveys are provided in the final DHS reports of selected countries.

All analysis was done using appropriate weighting factors to correct for the under- or over-sampling of different strata in sample selection. The weighted sample sizes for the current analysis are 21,762 (Egypt), 16,798 (Morocco), 10,424 (Mali) 11,160 (Niger) and 23,215 (Northern Nigeria). The individual women data of the five selected countries were analysed to address the objective of this paper.

3.1. Ethical consideration

The DHS Programme obtained approval for the conduct of the survey from the Ethics Committee of the Opinion Research Corporation Macro International (USA) and the Human Health Research Ethics Committee of the selected countries. Permission to use the data for this study was obtained from the DHS programme. There were no ethical issues with respect to analysis of the secondary data because it excluded all the unique identifier information.

3.2. Variables measurements

3.2.1. Outcome variable

The dependent variable in this study is children ever born (CEB), defined as the number of children ever born by women of reproductive ages 15–49.

3.3. Independent variables

Guided by the theoretical model and the reviewed literature, the selected independent variables for this study included religion [categorised as (i) Muslim, (ii) Christian and (iii) others], education [grouped as (i) no education, (ii) primary and (iii) secondary or higher], respondent’s age [grouped as (i) 15–24 (ii) 25–34 (iii) 35+], marital status [categorised as (i) never married, (ii) currently married, and (iii) previously married], respondent’s occupation [categorized as (i) not working, (ii) professional/managerial work, (iii) agric/clerical and (iv) labour], wealth index [grouped as (i) poor, (ii) middle and (iii) rich], contraceptive use [grouped as (i) currently using and (ii) not currently using], age at first birth [categorized as (i) <18 (ii) 18+], family structure [grouped as (i) monogamous (ii) polygynous], place of residence [grouped as (i) urban (ii) rural], and experience of child death [categorized as (i) had experienced (ii) had never experienced]. The existing empirical and theoretical studies have established the relevance of the selected covariates as factors influencing fertility behaviour globally (Adedini et al., Citation2014; Odimegwu & Adedini, Citation2013, Citation2013).

3.4. Statistical analysis

The study employed descriptive and inferential statistics in data analysis. The descriptive statistics include mean, standard deviation and percentage distributions. The inferential statistics were obtained using Poisson regression analysis. To disentangle the effects of religion as well as other selected covariates on fertility behaviour of respondents, three models were fitted at the multivariable level of analysis for each of the three selected countries for which religion variable was available in the datasets.Footnote2 Poisson regression analysis was applied using three basic modelling equations: (i) Model 0 which examined the effects of religion on fertility; (ii) Models 1 that examined the effects of selected control variables; and (iii) full model (Models 2 that examined the effects of religion and all selected covariates on CEB.

Given that CEB is a count variable, it was treated in our analysis as a count measure. Hence, Poisson regression model was employed as the suitable statistical technique. Rodriguez (Citation2007) opined that a random variable X can be said to have a Poisson distribution with parameter μ, if it takes integer values x = 0,1,2,3 …, with probability:

for μ > 0. The mean and variance of the distribution can be shown to be:

From the equations above, the mean and variance of the Poisson distribution are equal (Rodriguez, Citation2007).

Results from multivariable analysis were presented as incidence rate ratio (IRR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs). All analysis was conducted using Stata software (version 13.0).

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive results

presents the distribution of respondents by socio-economic and demographic characteristics in the selected five countries. With respect to age categories, except in Egypt and Niger, about 4 in 10 respondents were aged 15–24 years. Evidently, older respondents were in Egypt’s sample compared to other countries. Current marital status shows Morocco having the highest proportion of never married respondents with 42% . While other countries had about 8 or 9 in 10 being currently married, Morocco had 5 in 10 as currently married. Expectedly, Muslims dominate the proportion of respondents across countries as about 93% practised Islam in Mali, 77% in Northern Nigeria and 96% in Egypt. Most respondents had no education in Mali, Niger, and Northern Nigeria with 76%, 80% and 59%, respectively, but only Egypt had as high as 66% of the respondents with secondary or higher education. Except in Northern Nigeria with the lowest proportion of unemployed respondents (41%), unemployed respondents were dominant across other countries, highest in Egypt (84%), followed by Morocco (79%), Niger (71%) and Mali (62%). Proportional representations across countries in Professional/Managerial and Agricultural/Clerical categories were low except in Mali where, although still low, 15% were into Agricultural/Clerical employment. Northern Nigeria among the countries had more poor respondents with 56%. Others had about 36 to 38% of their respondents in poor category.

Table 1. Percentage distribution of socio-economic and demographic characteristics of respondents

On current use of contraception, except in Egypt and Morocco with relatively higher proportion of respondents that were currently using contraceptives with 55% and 33%, respectively; Mali, Niger and Northern Nigeria all had low current usage of contraceptives with 10%, 13% and 7%, respectively. Furthermore, it was evident from the results that Middle and West African countries had younger age at first birth. While half of the respondents in Niger and Northern Nigeria had their first birth below 18 years of age, closely followed by Mali with 44%, only 13% and 19% of respondents in Egypt and Morocco, respectively, had their first births below 18 years of age.

With focus on family structure, there exists clear a divergence in the practice of polygyny between Middle/West African countries and those in the Maghreb. Where 35%, 36% and 40% of respondents in Mali, Niger and Northern Nigeria, respectively, practise polygyny, about 4%did same in both Maghreb countries. Of all the countries, only Morocco had relatively fewer rural respondents (40%). On child mortality experience, respondents in Middle and West African countries experienced more child death than the Maghreb countries, as 22%, 40% and 32% from Mali, Niger and Northern Nigeria, respectively, have experienced child death, whereas only less than 11% had experienced same from Egypt and Morocco.

In , attempt was made to examine, across the selected countries, average number of children ever born (CEB) and surviving, age at first birth and current age of respondents. Mali, Niger and Northern Nigeria had average CEB of above 3, with Niger having the highest (4.0), followed by Northern Nigeria (3.5). Egypt and Morocco had average CEB of 2.7 and 1.9, respectively. Children survival appeared higher in Egypt (2.6) than in Morocco (1.8), And Mali, Niger and Northern Nigeria had 2.9, 3.2 and 2.8, respectively. Average age at first birth was lower in Niger and Northern Nigeria at 18 years; however, average age at first birth was highest in Egypt at 22 years, followed by Morocco at 21 years and Mali at 19 years of age. Focusing on current age of women, average age of respondents remained highest in Egypt at 33 years, followed by Morocco with 30 years. Mali, Niger and Northern Nigeria had the same average age of 29 years old.

Table 2. Means and standard deviation for continuous variables used in the models

Table 3. Mean number of children ever born (mean CEB) by respondents’ selected characteristics

Attempt was also made to assess average number of CEB across selected socio-economic and demographic characteristics for the selected countries. shows that average CEB among ages 35 and above was highest in Niger (7.1), followed by Northern Nigeria (6.7), Mali (5.6), Morocco (4.1) and the least in Egypt (3.7). Once again, Niger followed by Northern Nigeria had the highest average CEB among currently married women with 4.5 and 4.2, respectively, and maintaining the trend, Egypt had the least average CEB (2.7) followed by Morocco (3.4). With respect to religion, Northern Nigeria had the highest CEB among Muslims with least average CEB among Egyptian Muslim respondents. However among Christians, with Egypt still having the lowest average CEB, Mali had the highest average CEB. Expectedly, the table shows that average CEB across countries was inversely related to educational level. However, among respondents with no education, Niger, followed by Northern Nigeria, had the highest average CEB with 4.6 and 4.4, respectively. The least in this regard was Morocco (2.8). Among the unemployed, Niger had the highest average CEB with 3.7, and the least of which was in Morocco. The poor respondents had the highest average CEB across the selected countries, as shown in the table.

Expectedly, respondents who started childbirth earlier had higher average CEB. However, among respondents with age at first birth above 18 years, Niger and Northern Nigeria still had high average CEB of 4.4 and 4.1, respectively, while Egypt and Morocco had 2.8 and 3.5, respectively. In relation to family structure, with focus on polygynous family, Niger and Northern Nigeria had average CEB of 5.2 and 4.9, respectively, whereas Egypt and Morocco had average CEB of 2.9 and 3.6, respectively, among polygynous families. Among rural dwellers, Mali, Niger and Northern Nigeria had average CEB of more than 3, whereas Egypt and Morocco had 2.9 and 2.3, respectively. There was higher average CEB among respondents who had experienced child mortality across all countries, however, where only Egypt had an average CEB of 4.9, other countries but Mali (5.7), had 6 and above average CEB.

4.2. Results from multivariable analysis

Enquiry was made to examine the influence of religion on children ever born in a multivariable analysis, using Poisson regression models. presents the results from the analysis of countries that had religion variable in the datasets (i.e., Northern Nigeria, Mali and Egypt), while presents results for Niger and Morocco whose surveys had collected no information on religion. The results in Models 0, 1, and 2 () indicated no significant relationship between religion and fertility in the three countries that had information on religion (analysis not shown for Model 0).

Table 4. Results from poisson regression showing the effect of religion and other selected characteristics on fertility level (mali, northern nigeria and egypt)

Table 5. Results from poisson regression showing the effect of selected characteristics on fertility level (niger, morocco)

As earlier noted, Model 1 examined the effects of other selected variables independent of religion. The results in Models 1 and 2 established age at first birth, current age of respondents, and experience of child’s loss as significant predictors of CEB in Egypt, Mali and Northern Nigeria. For instance, Model 3 revealed that women aged 35 and above were significantly more likely to have higher CEB in Egypt (IRR: 2.27, p < 0.01), Mali (IRR: 3.03, p < 0.01) and Northern Nigeria (IRR: 3.39, p < 0.01) compared to those aged 15–24. Women who had first birth at age 18 or older were significantly more likely to have fewer children in Egypt (IRR: 0.79, p < 0.05), Mali (IRR: 0.77, p < 0.05) and Northern Nigeria (IRR: 0.77, p < 0.05) compared to those whose first birth was before age 18. Women who had experienced child’s death were significantly more likely to have higher CEB in Egypt (IRR: 1.44, p < 0.01), Mali (IRR: 1.39, p < 0.05) and Northern Nigeria (IRR: 1.37, p < 0.05) compared to those who had lost no children.

In addition, results indicated that CEB significantly reduces with higher education a significant relationship between educational attainment and CEB, as women that had secondary or higher education in Mali (IRR: 0.88, p < 0.05) and Northern Nigeria (IRR: 0.87, p < 0.5) were likely to have fewer kids compared to the uneducated women. Further, occupation significantly predicted CEB in Mali, as women in professional cadre were likely to have fewer children (IRR: 0.83, p < 0.05) compared to the unemployed.

Although information on religion was not available in the datasets of Niger and Morocco, the results obtained from Poisson regression model for the two countries showed comparable findings to those obtained from the analysis of datasets of Egypt, Mali and Northern Nigeria. For instance, showed that respondents’ age, education, occupation, age at first birth and experience of child’s loss were significantly associated with fertility in Morocco and Niger.

5. Discussions and conclusion

This study examined the drivers of divergence in fertility levels and patterns between the selected countries in Middle/West Africa and the Maghreb, all of which are dominated by practice of Islamic religion. The study adopted most recent Demographic and Health Survey data of the selected countries in testing the study hypothesis. It appears in consonance with our hypothesis that, factors other than strict adherence to Islamic religious beliefs, are the drivers of fertility levels and patterns in the selected countries.

Exclusively examining religious implications for fertility level across countries, it was found that religion, as a determinant of fertility, is unlikely across the selected countries. Clearly, the divergence in fertility pattern between the Middle/West African countries and their Maghreb counterparts is traceable to the differences in the proximate determinants of fertility across these countries.

First, our descriptive findings established marriage as a universal phenomenon in Mali, Niger and Norther Nigeria, with a predominantly majority of respondents being currently married, compared to as high as two-fifths of respondents being currently unmarried in Morocco. Given that childbearing is greatly linked with marriage, and childrearing is much expected in the context of marriage in most Middle/West Africa (Desai, Citation1992; Hayase & Liaw, Citation1997; C. O. Odimegwu et al., Citation2017), universality of marriage among women aged 15–49 in this sub-region plays a significant role in shaping the observed divergent fertility pattern in the selected Middle/West Africa countries as compared to those in the Maghreb.

Second, our analysis indicates that mean age at first birth remains very low in Mali, Niger and Nigeria, currently estimated at around 18 years, compared to around 22 years in Egypt and Morocco (UNICEF, Citation2018; World Factbook, Citation2018). As established in the multivariable analysis, this is a significant factor and it plays a major role in influencing the divergent pattern in fertility levels of selected countries in both sub-regions.

Third, descriptive findings of this study also showed that percentage of women using contraception was very low in Mali, Niger and Northern Nigeria—estimated at around one-tenth, which was far lower than the proportion of women using contraception in Egypt (more than half)) and Morocco (one-third). This is a major basis for divergence in fertility levels of selected countries in both sub-regions. Previous studies have established higher unmet need for contraception in Middle/West African countries compared to those in North Africa (Kotb et al., Citation2011; Moreland et al., Citation2010; Shakhatreh, Citation2003).

Further, our analysis lends credence to the previous findings which established a predominantly higher under-five mortality for Mali, Niger and Nigeria at well above 100 deaths per 1000 live births, compared to just around 30 deaths/1000 live births in Egypt and Morocco (UNICEF, WHO, Bank, W. & UN DESA Population Division, Citation2017). As postulated by the replacement and insurance fertility hypotheses, higher fertility levels are generally found in countries with high under-five mortality, and this is a major factor influencing divergence in fertility levels of countries in both sub-regions. Results from multivariable analysis support these hypotheses, thus establishing experience of child’s loss as a significant driver of fertility in the selected Middle/West African countries.

Moreover, results of this study suggest that plurality of marriage is a major concern for divergent pattern in fertility levels between Middle/West African and Maghreb countries, as around 2 in 5 women were in polygynous unions in Mali, Niger and Norther Nigeria; compared to the selected Maghreb countries where polygynous marriage was almost non-existent. Based on this result, polygyny (although insignificant in the multivariable analysis) appears to be a driver of divergent pattern in fertility levels between the selected countries of Middle/West Africa and the Maghreb. Previous studies have established polygyny as a prevalent form of marriage in West/Middle Africa (Adedini & Odimegwu, Citation2017; Omariba & Boyle, Citation2007; Smith-Greenaway & Trinitapoli, Citation2014).

In addition, education seems to contribute to the observed divergence in fertility levels between the countries in both sub-regions, as fertility level was significantly higher for the uneducated women compared to their educated counterparts. Meanwhile, the study found that the proportion of women with no education was higher in Mali, Niger and Northern Nigeria compared to Egypt and Morocco. Prior research has also shown education, particularly of girl children, as an important determinant of fertility in developing countries (Ezeh et al., Citation2009; Garenne, Citation2013)

This study has demonstrated that it is not Islamic religion per se that is responsible for the high level of fertility in Middle/West Africa in particular, and perhaps in other parts of sub-Saharan Africa. As hypothesized and based on the theoretical foundation established by the framework, differences in fertility level between the selected Middle/West Africa and Maghreb countries is due to characteristics such as socio-economic and demographic variables. Results of this analysis seem to support this hypothesis.

Religious differences in fertility are attributable to women’s characteristics other than their religious affiliation. The study shows the importance of women characteristics as key drivers of fertility in the selected countries. It demonstrates that women’s religious affiliation had insignificant influence on the level of fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. This study therefore concludes that policies that target achievement of fertility reduction in Middle/West Africa must include strategies that aim at ameliorating women’s socio-economic characteristics and positions.

6. Limitations and strengths of study

This study has some limitations. First, due to the cross-sectional nature of the survey data, the study could not establish causal relationship between fertility behaviour and the selected characteristics. Second, some important individual and contextual variables were not included in the analysis due to their non-availability in the datasets. For instance, religion variable was not available in Niger and Morocco’s datasets. Nevertheless, because religion variable was available in other selected countries, analysis was done to tease out its effect on fertility behaviour. Although the Morocco data were not recent, its inclusion in the analysis was to ensure sufficient results were obtained from the Maghreb countries. The data provided useful results from the Maghreb region. Also, we acknowledge it as a limitation that the latest datasets of some of the selected countries were not analysed in this study. Notwithstanding these limitations, the study extends the frontier of knowledge and established a significant new finding that variations in fertility are largely attributable to differences in women’s socio-economic status and characteristics other than their religious affiliation.

7. Acknowledgments

Earlier version of this paper was presented at the 28th International Population Conference of the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population (IUSSP) held in November 2017 in Cape Town, South Africa. Authors appreciate the comments from conference participants.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sunday A. Adedini

Sunday A. Adedini is an Associate Professor in the Department of Demography and Social Statistics, Federal University Oye-Ekiti, Nigeria, and a Research Fellow at the Programme in Demography and Population Studies, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. His research interests include maternal and child health and reproductive health. The research reported in this paper is part of his work on reproductive health. Hassan Ogunwemimo holds B.Sc and M.Sc in Demography and Social Statistics and is currently a doctoral student in Public Health at the Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, with interest in Health Systems and Health Services Research. He leads a research firm, Knightmark Consultancy Services. Luqman Adeleke Bisiriyu holds Ph.D in Demography and Social Statistics from the Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria. He is an Associate Professor in the same Department. His research interests cover Sexual and Reproductive Health, Gender, infant and child health.

Notes

1. International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) of 1994 held in Cairo.

2. Religion variable was not available in the DHS data of Niger and Morocco, hence the study only examined the influence of other selected variables on fertility behaviour of women in these two countries.

References

- Adedini, S. A., & Odimegwu, C. (2017). Polygynous family system, neighbourhood contexts and under-five mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. Development Southern Africa, 34(6), 704-720.

- Adedini, S. A., Odimegwu, C., Bamiwuye, O., Fadeyibi, O., & De Wet, N. (2014). Barriers to accessing health care in Nigeria: Implications for child survival. Global Health Action, 7:(23499), 23499. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.23499

- Agadjanian, V. (2013). Religious denomination, religious involvement and contraceptive use in Mozambique. Studies in Family Planning, 44(3), 259–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2013.00357.x

- Agadjanian, V., & Yabiku, S. T. (2014). Religious affiliation and fertility in a sub-saharan context: dynamic and lifetime perspectives. Population Research and Policy Review, 33(5), 673–691. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-013-9317-2

- Angelsen, A., & Kaimowitz, D. (1999). Rethinking the causes of deforestation: Lessons from economic models. The World Bank Research Observer, 14(1), 73–98. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/14.1.73

- Barro, R. J. (1998). Determinants of Economic Growth: A Cross Country Empirical Study. MIT Press.

- Bongaarts, J. (2008). Fertility transitions in developing countries: Progress or stagnation? Studies in Family Planning, 39(2), 105–110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00157.x

- Buhaug, H., & Urdal, H. (2013). An urbanization bomb? Population growth and social disorder in cities. Global Environmental Change, 23(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.10.016

- Desai, S. (1992). Children at risk: The role of family structure in latin america and West Africa. Population and Development Review, 18(4), 689–717. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1973760

- Ezeh, A. C., Mberu, B. U., & Emina, J. O. (2009). Stall in fertility decline in Eastern African countries: Regional analysis of patterns, determinants and implications. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 364(1532), 2991–3007. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0166

- Garenne, M. (2013). Situations of fertility stall in sub-Saharan Africa. African Population Studies, 23(2). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.11564/23-2-319

- Goldscheider, C. (1971). Population, modernization, and social structure. Little, Brown and Company.

- Hayase, Y., & Liaw, K.-L. (1997). Factors on polygamy in sub-Saharan Africa: Findings based on the Demographic and Health Surveys. The Developing Economies, 35(3), 293–327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1049.1997.tb00849.x

- Hirsch, J. S. (2008). catholics using contraceptives: religion, family planning, and interpretive agency in rural Mexico. Studies in Family Planning, 39(2), 93–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00156.x

- Ilyas, M., Alam, M., Ahmad, H., & Sajid ul, G. (2009). Abortion and protection of the human fetus: Religious and legal problems in Pakistan. Human Reproduction & Genetic Ethics, 15(2), 55–59. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1558/hrge.v15i2.55

- Izugbara, C. O., & Ezeh, A. C. (2010). Women and high fertility in islamic northern Nigeria. Studies in Family Planning, 41(3), 193–204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2010.00243.x

- Kotb, M. M., Bakr, I., Ismail, N. A., Arafa, N., & El-Gewaily, M. (2011). Women in Cairo, Egypt and their risk factors for unmet contraceptive need: A community-based study. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care, 37(1), 26–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/jfprhc.2010.0006

- Moreland, S., Smith, E., & Sharma, S. (2010). World population prospects and unmet need for family planning. Futures Group.

- Morgan, S. P., Stash, S., Smith, H. L., & Mason, K. O. (2002). Muslim and non‐Muslim differences in female autonomy and fertility: Evidence from four Asian countries. Population and Development Review, 28(3), 515–537. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2002.00515.x

- Odimegwu, C., & Adedini, S. A. (2013). Do family structure and poverty affect sexual risk behaviors of undergraduate students in nigeria? African Journal of Reproductive Health, 17(4), 137–149.

- Odimegwu, C., Pallikadavath, S., & Adedini, S. (2012). The cost of being a man: Social and health consequences of Igbo masculinity. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 15(2), 219-234. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2012.747700

- Odimegwu, C. O., Wet, N. D., Adedini, S. A., Nzimande, N., Appunni, S., & Dube, T. (2017). Family demography in sub-saharan Africa: A systematic review of family research. African Population Studies, 31(1), 3528–3572. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.11564/31-1-1023

- Omariba, D. W. R., & Boyle, M. H. (2007). Family structure and child mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: Cross-national effects of polygyny. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(2), 528–543. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00381.x

- Ononokpono, D. N., Odimegwu, C. O., Imasiku, E. N., & Adedini, S. A. (2014). Does it really matter where women live? A multilevel analysis of the determinants of postnatal care in Nigeria. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 18(4), 950–959. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1323-9

- Rodriguez, G. (2007). Poisson Models for Count Data

- Shakhatreh, F. M. (2003). Unmet need for family planning. Saudi Med J, 24(11), 1268–1269.

- Smith-Greenaway, E., & Trinitapoli, J. (2014). Polygynous contexts, family structure, and infant mortality in sub-saharan Africa. Demography, 51(2), 341–366. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-013-0262-9

- UNICEF. (2018). Many are mothers at 18. https://www.unicef.org/pon95/fami0009.html

- UNICEF, WHO, Bank, W., & UN DESA Population Division. (2017). UN Inter-agency group for child mortality estimation. http://www.childmortality.org/

- United Nations. (2015). Trends in Contraceptive Use Worldwide.

- UNFPA. (2011). World Population Day 2011: The World at 7 Billion. www.unfpa.org/world-7-billion

- World Bank. (2010). Determinants and Consequences of High Fertility: A Synopsis of the Evidence.

- World Bank. (2010a). Determinants and Consequences of High Fertility: A Synopsis of the Evidence.

- World Bank. (2010b). Determinants and Consequences of High Fertility: A Synopsis of the Evidence. http://www.worldbank.org

- World Bank. (2018). World Bank Open Data. https://data.worldbank.org/

- World Factbook. (2018). Mother’s age at first birth. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2256.html