Abstract

This study investigates the role of managerial and marketing capabilities in moderating the relationship between competitive strategy and firm performance using data from 581 micro and small businesses (MSBs) in Ghana. Using a hierarchical multiple regression analysis the findings indicate that while differentiation strategy is related to performance, cost leadership strategy does not influence performance after controlling for several firm-specific factors. The findings further show that both managerial capability and marketing capability moderate the relationship between competitive strategy (cost leadership and differentiation) and performance for MSBs in Ghana. However, managerial capability strengthens the influence of cost leadership strategy on performance, while it weakens the impact of differentiation on performance. Moreover, marketing capability augments the impact of differentiation on performance, while it diminishes the influence of cost leadership on performance. The findings indicate a contingency approach to the implementation of competitive strategy by MSBs.

INTRODUCTION

Micro and small businesses (MSBs) are pervasive and critical to the economies of transition and emerging economies. In fact, the principal engines of growth in most economies all over the world are attributed to the activities of MSBs (Fatoki & Garwe, Citation2010). Although precise estimates of MSBs in transition economies are difficult to obtain, it is suggested that more than 95% of businesses across the world are micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) with a greater proportion of these businesses being MSBs (Ayyagari, Demirgüç-Kunt, & Maksimovic, Citation2011). MSBs are ubiquitous organizations in Africa. For example, in Ghana, it is estimated that about 92% of all businesses are MSBs and these businesses contribute about 70% of gross domestic product (GDP) (Abor & Quartey, Citation2010). Masakure, Henson and Cranfield (Citation2009) have also estimated that there are about 2.3 million non-farm small enterprises in Ghana and 99.4% of these enterprises could be classified as microenterprises. Thus, MSBs are instrumental in value-added creation, industrial change and innovation, poverty reduction, wealth generation, and job creation (Ayyagari et al., Citation2011; Kanyabi & Devi, Citation2011). It has also been contended by Shepherd and Wiklund that MSBs are “essential for entrepreneurial activity, innovation, job creation, and industry dynamics” (2005: 1).

Despite the important role played by MSBs in many economies, they are unstable and many of them do not survive beyond three years (Liberman-Yaconi, Hooper, & Hutchings, Citation2010). Thus the survival, competitiveness and success of MSBs is crucial to the achievement of socio-economic development in African economies. However, a number of factors have been identified as constraints to the survival and performance of MSBs, and those constraints are more evident in Africa. These include low levels of managerial skills, lack of access to market information, lack of resources and capabilities (e.g. financial capital, human capital, and capabilities) (Liberman-Yaconi et al., Citation2010; Robson, Haugh, & Obeng, Citation2009). What is usually missing from the factors contemplated to be constraining the survival, competitiveness, and performance of MSBs is their ability to focus on a coherent strategic orientation. It has been shown that effective strategic decision-making improves performance, and increases the success and survival chances of MSBs (Beaver & Jennings, Citation2005; Liberman-Yaconi, et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, the strategy pursued by small and medium-sized enterprises has been shown to improve performance (Madrid-Guijarro, Garcia-Perez-de-Lema, & Van Auken, Citation2013). Gaining insight into the strategic activities of MSBs would therefore represent a contribution to the strategic management literature in transition economies in general as it has received little attention when compared with large organizations (Johnson, Melin, & Whittington, Citation2003). The purpose of this paper is to fill this gap by examining the role competitive strategy plays in the performance of MSBs. We posit that the ability of MSBs in Africa to be competitive and improve their performance depends on their capacity to leverage their capabilities for implementing a coherent competitive strategy. In order words, we argue that organizational capabilities will positively moderate the influence of competitive strategy on performance for MSBs. We focus on the competitive strategies of cost leadership and differentiation strategies, and the marketing and managerial capabilities of MSBs in Ghana. We focus on MSBs for several reasons: (a) these firms dominate the economies of African countries; (b) these firms are confronted with severe resource constraints in the implementation of competitive strategy; and (c) the strategic activities of these firms in Africa are under-represented in strategy research.

The strategic management literature emphasizes the role played by organizational capabilities (Barney, Citation1991; Wernerfelt, Citation1984), and competitive strategy (Porter, Citation1980) in creating a sustainable competitive advantage for firms. The resource-based view (RBV) posits that the internal resource endowments and capabilities of firms are the sources of performance (Barney, Citation1991; Lippman & Rumelt, Citation1982; Wernerfelt, Citation1984) and there is ample evidence in the literature to corroborate the RBV propositions (e.g. Acquaah & Chi, Citation2007; Newbert, Citation2007). “These resources and capabilities can be viewed as bundles of tangible and intangible assets, including a firm’s management skills, its organizational processes and routines, and the information and knowledge it controls” (Barney, Wright, & Ketchen, Citation2001: 625). The RBV has also been used in SME studies because it has been argued that its focus on resources and capabilities, which are usually scarce in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), make it an appropriate theory to examine SME challenges (Camison & Villar-Lopez, Citation2010; Lu & Beamish, Citation2001). Moreover, despite the call from Barney et al. (Citation2001: 634) that “most of the focus of RBV research has been on larger firms, yet smaller firms also face the need to acquire critical resources to create sustainable competitive advantage”, little research has examined the strategic activities of MSBs from an RBV perspective (Kelliher & Reinl, Citation2009; Masakure et al., Citation2009). It has also been shown that the implementation of coherent competitive strategies allows firms, small, medium, and large alike, to improve their performance (e.g. Campbell-Hunt, Citation2000). The dominant view of the competitive strategy perspective is that resources and capabilities are required to effectively pursue a viable competitive strategy that would allow for creating and sustaining competitive advantage (Li, Zhou, & Shao, Citation2009). Despite the deficiencies in capabilities’ endowments by MSBs, we argue that leveraging the existing managerial and marketing capabilities to implement their competitive strategy would enable them to exploit the opportunities in the external environment in order to enhance their competitiveness and performance. Thus, the RBV and the competitive strategy perspective complement each other in explaining the performance of MSBs.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: The next section that follows this introduction presents the theoretical background and derives the hypotheses. We present a discussion of the definition of MSB first before discussing the theory and hypotheses. The next section is devoted to the methodology, which explains the data and statistical methods. A further section presents the results of the analysis, while the last section discusses the discussion of the findings and concludes the study.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Micro and Small Businesses (MSBs)

Micro and small businesses dominate all economies around the globe. In spite of the admirable contribution of MSBs to the world’s economy, there is no uniform acceptable definition of what constitutes a micro and small business (Storey, Citation1994). The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) considers businesses with less than 10 employees as small-scale enterprises and their counterparts with more than 10 employees as medium- and large-sized enterprises. The National Board for Small Scale Industries in Ghana (NBSSI) also defines a small-scale enterprise as one with not more than nine workers, which has plant and machinery (excluding land, buildings, and vehicles) not exceeding 10 million Cedis (US$ 9506, using the 1994 exchange rate, or US$1419 using the 2000 exchange rate) (Masakure et al., Citation2009). However, Steel and Webster (Citation1990) describe small-scale enterprises as businesses with less than 30 employees. It should be noted that neither the GSS nor NBSSI delineates micro businesses from small businesses in its definitions but considers them as part of small-scale enterprises. However, Osei, Baah-Nuakoh, Tutu and Sowa (Citation1993) disaggregate small-scale enterprises into three categories: (i) micro – businesses employing less than six people; (ii) very small – businesses employing six to nine people; and (iii) small – businesses employing between 10 and 29 people, thus indicating that micro and small businesses have fewer than 30 employees. Recent researchers define micro business in Ghana as businesses employing nine or fewer people (Masakure et al., Citation2009; Mensah, Tribe & Wess, Citation2007; Obeng, & Blundel, Citation2015) and small businesses as fewer than 20 employees (Obeng & Blundel, Citation2015). In this study, we adopt the definition of micro and small businesses provided by Osei et al. (Citation1993) because it is more comprehensive and captures micro and small businesses in Ghana accurately.

A distinguishing feature of MSBs when compared with medium and large-scale enterprises is that MSBs have limited resources and capabilities such as physical assets, financial resources, human capital, managerial capabilities, and marketing capabilities (Camison and Villar-Lopez, Citation2010). However, because of the heterogeneity of the resources and capabilities base of MSBs, identifying the resources and capabilities required for the strategic organization of their activities efficiently and effectively is not easy. Another feature of MSBs is that they are usually characterized by informality. For instance, MSBs in Ghana could be categorized as urban or rural enterprises. The MSBs in urban areas could be sub-divided into semi-formal or “organized” and informal or “unorganized” enterprises (Osei et al, Citation1993). The organized MSBs tend to have paid employees with a registered office whereas the unorganized MSBs are usually made up of artisans who work in open spaces, temporary wooden structures, or at home and employ few or in some cases no salaried workers. They rely mostly on family members or apprentices for their activities. The MSBs in the rural area are mostly characterized by family members, individual artisans, and women engaged in selling food prepared from local foodstuffs. The major activities of the MSBs in the rural areas have been found to include: soap and detergents manufacture; fabrics, clothing and tailoring, and textile making; blacksmithing and tin-smithing; ceramics manufacture; bricklaying; beverages and food processing and sales; furniture making; electronic assembly; agro processing; and mechanic work (Masakure et al., Citation2009; Osei et al., Citation1993, World Bank, Citation1992). It should be noted that most of these businesses activities are also characteristics of MSBs in urban areas.

Organizational Capabilities

Various theoretical perspectives have been proposed by the strategic management literature to explain variations in firm performance. One such theory that has received popular acceptance in the literature is the resource-based view (RBV) of the firm. The RBV propounds that a firm’s competitive advantage is based on the possession and deployment of resources and capabilities, which are often heterogeneous, idiosyncratic, immobile, inimitable, and sometimes intangible (Barney Citation1991; Habbershon and Williams, Citation1999; Peteraf, Citation1993). It is this bundle of resources and capabilities in the possession of a firm that increases the prospect of obtaining competitive advantage and superior performance. Resources may be thought of as inputs that enable an organization to carry out its activities whereas capabilities refer to a firm’s ability or capacity to exploit and combine resources, through organizational routines, in order to accomplish its targets (Amit & Schoemaker, Citation1993). Capabilities are usually considered lower-order functional, operational, or technical capacities that may be categorized into individual skills or specialized organizational skills (Ortega, Citation2010). Capabilities comprise individual employee skills, expertise, and tacit accumulated knowledge that are embedded in an organization’s routines, managerial processes, marketing communications, and culture. Organizational capabilities include marketing, innovative, managerial, technological, manufacturing capability, new product development, and customer service capability. However, for the purpose of this study, we consider how the managerial and marketing capabilities possessed by MSBs affect their capacity to deliver their competitive strategies effectively to achieve superior performance. We expect that the integration of managerial and marketing capabilities with competitive strategy will significantly account for differences in the performance of MSBs.

Marketing Capabilities

According to Orr, Bush and Vorhies, a marketing capability is the “accumulated knowledge and skills of the firm’s marketing employees that are utilized to create customer satisfying outcomes” (2011: 1074). A marketing capability is further defined as the repeated patterns of a firm to effectively undertake its market-related needs (Chang, Park, & Chaiy, Citation2010). A marketing capability is, therefore, the accumulated knowledge, skills, and expertise embedded in the marketing activities and the organizational processes throughout the firm. The accumulated knowledge, skills, and expertise may be developed in the areas of marketing research, pricing, product development, distribution channels, promotion, and marketing management (Vorhies & Harker, Citation2000; Vorhies, Harker & Rao, Citation1999). A firm’s marketing capability further shows its ability to develop and implement marketing strategy effectively. De Sarbo, Di Benedetto and Song (Citation2007) submit the view that the development of marketing capabilities in micro and small businesses is created as a result of policies and practices that are related to the firm’s marketing mix. The marketing literature has demonstrated that marketing capabilities are critical to the formulation and implementation of competitive strategies (Weerawardena, Citation2003), and enhancing firm performance (Day, Citation1994; Morgan, Slotegraff, & Vorhiess, 2009; Slotegraaf & Dickson, 2004; Vorhies & Morgan, Citation2005).

Managerial Capabilities

A managerial capability is defined as the management capacities, expertise, and processes in the custody of firms that are drawn to execute programs and activities to achieve superior performance (Graves & Thomas, Citation2006). A managerial capability is, therefore, “ the degree to which a firm’s corporate management team utilizes its team-embodied complementary yet heterogeneous skills, abilities, expertise and knowledge base that have been developed over time to generate rents” (Acquaah, Citation2003: 64). A managerial capability, therefore, includes the human, social, and cognitive abilities, used to deploy, integrate, and reconfigure tangible and intangible organizational resources. They are useful in planning, executing, and controlling processes and strategic actions. Adner and Helfat (Citation2003), however, suggest that the characteristics of the top management team of a firm are a major contributor to the development of managerial capabilities that ensures sustained competitive advantage. Fernández and Nieto (Citation2005) have also stated that an increase in the size or quality of management increases managerial capabilities. A managerial capability allows an organization to integrate the capabilities arising from technical, conceptual, and human skills, so as to be able to make better use of its human and physical resources by assigning not only employees but also other resources to areas where they have higher productivity (Acquaah, Citation2003). Barney and Hesterley (Citation2006) argue that the role of managerial capability in controlling and monitoring organizational systems is critical for executing the strategic actions of the firms for it to be effective and sustainable. Several studies have shown that managerial capability positively influences performance (Acquaah, Citation2003; Daily & Dollinger, Citation1993; Day, Citation1993; Littunen, Citation2003).

Competitive Strategy

Competitive strategy is basically concerned with the patterns of decisions or choices that managers of firms make over which markets to compete in and how the business can add more value for buyers in order to gain more advantage than competitors. Porter’s generic competitive strategy, which is the focus of this study, has been widely accepted as one of the most important contributors to the study of strategic behavior in organizations (Campbell-Hunt, Citation2000). The typology can be recognized as the dominant paradigm of competitive strategy. According to Porter (Citation1980), an organization can generate competitive advantage and ostensibly maximize performance – either through cost leadership, differentiation, or a focus strategy. Extant literature supports the notion that each of these three generic strategies influences firm performance in diverse contexts, and they are therefore highly implemented by firms that want to outcompete their competitors. This study focuses on the competitive strategies of cost leadership and differentiation.

Cost Leadership Strategy

A cost leadership strategy emphasizes creating competitive advantage through generating and maintaining low-cost positions relative to competitors (Porter, Citation1980). Cost leadership entails being the lowest cost provider of goods and services for a given quality level. Hoskisson, Ireland and Hitt (2011) define cost leadership strategy as an integrated set of actions taken to produce goods or services with features that are acceptable to customers at the lowest cost, relative to that of competitors. Such a strategy is characterized by tight control of costs and overheads, minimization of operational costs, reduced labor costs and reduced input costs (Acquaah, Citation2011; Porter, Citation1985). As Porter (Citation1980) notes, the focus of firms implementing a cost leadership strategy is on stringent cost control and efficiency in all areas of operation. Firms that implement cost-leadership strategies can achieve competitive advantage by engaging in value-chain activities at lower cost than competitors (Porter, Citation1985). Cost-leadership strategy seeks to provide a standard, no-frills, high-volume product at the cheapest prices to customers. Porter (Citation1980: 36) argues that maintaining “a low overall cost position often requires a high relative market share or other advantages, such as favourable access to raw materials”. MSBs can achieve cost leadership strategy by offering standardized products, offering basic no-frills products and limiting customization and personalization of service. Porter (Citation1980) contends that cost leadership strategy is not a viable strategy only for large businesses because of the benefits of economies of scale but small businesses can also use cost leadership successfully if they take any advantages beneficial to low cost. Firms aiming to gain competitive advantage through cost leadership need to be competitor rather than customer oriented (Frambach, Prabhu, & Verhallen, Citation2003). Empirical studies in both industrialized and emerging economies show that the implementation of cost-leadership strategy enhances performance in both small and large businesses (Acquaah & Yasai-Ardekani, Citation2008; Agyapong & Boamah, Citation2013; Bowman & Ambrosini, Citation1997; Campbell-Hunt, Citation2000; Kim, Nam & Stimpert, Citation2004).

Differentiation Strategy

Differentiation strategy involves creating a market position that is perceived as being unique industry-wide and that is sustainable over the long run (Porter, Citation1980). Differentiated goods and services satisfy the needs of customers through a sustainable competitive advantage. A differentiation strategy allows organizations to de-sensitize customers to prices and focus on value that generates a comparatively higher price and a better margin. When an organization differentiates its products, it is often able to charge a premium price for its products or services in the market. Some of the characteristics of the differentiation strategy include a focus on customer service, better product performance, design, brand image, and control of distribution channel (Frambach et al., Citation2003; Porter, Citation1980, Citation1985). The uniqueness of differentiation strategy may permit the organization to charge premium prices for its products and/or services. To succeed, the increased income generated from higher prices must cover the cost of offering the unique product or service. Porter (Citation1980) has argued that for a company employing a differentiation strategy, there would be extra costs that the company would have to incur. Such extra costs may include high advertising spending to promote a differentiated brand image for the product, which in fact can be considered as a cost and an investment. These costs must be offset by the increase in revenue generated by sales; costs must be recovered. Empirical evidence shows that a differentiation strategy positively influences performance in small and large businesses (Acquaah Citation2011; Acquaah, Adjei, & Mensa-Bonsu, Citation2008; Agyapong & Boamah, Citation2013; Li et al., Citation2009; Miller & Dess, Citation1993; Spanos, Zaralis, & Lioukas, Citation2004;).

Hypotheses Development

Moderating Effect of Managerial Capability on Competitive Strategy-Performance

Managerial capability plays an important role in the implementation of cost leadership and differentiation strategies. A firm’s managerial capability should not only fit but also strengthen the implementation of its strategy. Since the objective of implementing a cost-leadership strategy, for instance, is to be the lowest cost producer of goods or service provider within the industry, managerial capabilities are needed to narrow the business functions for efficiency and optimal impact. Porter (Citation1980) identified common required skills needed by the firm to implement a successful cost-leadership strategy to include sustained availability of process engineering skills, ability to constantly supervise employee activities, ability to evaluate and control the employees, and process design ability. Other skills include the ability to control cost, comprehensive control of reports, and the ability to establish incentive-based systems that are tied to the achievement of tight quantitative targets. It is therefore clear that the firm needs managerial capabilities to implement cost-leadership strategy. Without managerial capability, it would be difficult for the firm to implement a successful competitive strategy. Barney and Hesterley (Citation2006) for example argue that management control systems in the form of tight cost control and evaluation systems, meeting quantitative cost targets, close supervision and control of employees, and strict raw materials and inventory management are essential requirements for implementing a successful cost leadership strategy. An MSB with a strong managerial capability would be able to manage the skills required for the implementation of the cost-leadership strategy.

Similarly, differentiation strategy cannot be implemented without an organization having a strong managerial capability. Common organizational requirements suggested by Porter (Citation1980) to achieve differentiation include strong marketing capabilities, product design and engineering, corporate image and reputation, customer service, and a unique combination of skills drawn from other businesses, new product development, and the ability to attract highly skilled employees. To achieve these, an organization requires a strong managerial ability to obtain and manage requirements and skills to implement the differentiation strategy (Day, Citation1992). Managerial capability is needed to enhance the firm’s ability to integrate resources, and to innovate to improve product quality and features in order to create value for customers so as to charge high prices, and, thus, bring about higher performance. An MSB that implements differentiation strategy requires strong managerial capabilities to be able to emphasize the unique features of the products or services they offer as against their rivals. An MSB implementing a differentiation strategy is likely to rely on promotions and extensive communication activities with its customers so that it can build trust, strong brand image, and influence consumer perceptions positively towards its products and services. Although MSBs in Ghana generally lack extensive managerial capabilities, we believe that the managerial capabilities available to them could be used to monitor employees, which is required for the successful implementation of a cost-leadership strategy, and also to build the trust needed for the differentiation strategy. We therefore hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1: Managerial capability will positively moderate the relationship between cost leadership strategy and the performance of micro and small businesses in Ghana.

Hypothesis 2: Managerial capability will positively moderate the relationship between differentiation strategy and the performance of micro and small businesses in Ghana.

Moderating Effect of Marketing Capability on the Competitive Strategy–Performance Relationship

There is enough evidence to suggest that marketing capabilities contribute to firm performance (Day, Citation1994; Weerawardena, Citation2003). Therefore, we expect that marketing capabilities which are exhibited through the skills and knowledge of management and employees responsible for marketing activities would be leveraged to implement the competitive strategies of cost leadership and differentiation. The differentiation strategy focuses on creating the perception of uniqueness of a firm’s product or service offerings and thus increasing their perceived value in the minds of consumers so that they will be willing to pay premium prices. Several marketing techniques are required to communicate with consumers about the uniqueness and value-creating characteristics of the firm’s product or service portfolio. Some of the marketing techniques include advertising and promotion, branding and brand management, exceptional customer service, and control of channels of distribution (Acquaah & Yasai-Ardekani, Citation2008). These marketing techniques cannot be effectively deployed in the implementation of a differentiation strategy without strong marketing capability. In fact, it has been argued by Weerawardena (Citation2003) that marketing capabilities are essential in designing appropriately the competitive strategy that would lead to a competitive advantage. Thus, MSBs who will have greater success in implementing the differentiation strategy should have a strong marketing capability to enable them to communicate with consumers regarding their differentiation points and why they provide better overall value than the competition. Research has shown that MSBs are effective in constantly surveying the marketplace and customers so as to be responsive and to better serve those customers (Gonzalez-Benito, Gonzalez-Benito, & Munoz-Gallego, Citation2009).

Furthermore, a firm with strong marketing capability can leverage it in the implementation of the cost-leadership strategy. Although the cost-leadership strategy places a premium on efficient operations and cost minimization at all levels, having marketing capability can play an import role in its implementation. A firm that has accumulated extensive knowledge concerning its market would to be able to decipher alternatives and best practices for ways of satisfying customer needs, and be able to stay relevant in the market without compromising its cost thresholds. More importantly a firm would require good marketing communication abilities and planning to continuously engage its customer base so not to lose them to its competitors (Ortega, Citation2010). Hence it is not enough to be a low-cost producer or service provider if the firm lacks the capacity to engage its customers and/or showcase its strength in order to direct more traffic towards its products or services. Marketing capability allows the firm to build and manage its customer relationship during the implementation of its strategy (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994). Thus, MSBs with strong marketing capabilities will be knowledgeable about changing market and production trends, competitors’ activities, best practices, and other information that may be critical to its survival as a low-cost producer in the market. Marketing capability will, therefore, complement the effect of cost-leadership strategy on performance for MSBs.

It follows from the above arguments that though differentiation and cost-leadership strategies will influence performance positively, having strong marketing capability that allows the firm to communicate its value proposition effectively will augment the impact of both differentiation and cost-leadership strategies on performance. This means that MSBs that have developed a strong marketing capability would be able to gain more value out of the implementation of their competitive strategy. We, therefore present the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3: Marketing capability will positively moderate the relationship between differentiation strategy and the performance of micro and small businesses in Ghana.

Hypothesis 4: Marketing capability will positively moderate the relationship between cost leadership strategy and the performance of micro and small businesses in Ghana.

METHODS

Using a convenience sampling technique, the study identified MSBs operating in the Kumasi Metropolitan area of the Ashanti Region of Ghana. One thousand questionnaires were administered to owners and/or managers of the MSBs that were selected. To qualify to be selected as an MSB, the owners and/or managers were asked to indicate the number of employees in their business. All the businesses that had employees numbering 30 or less were considered micro and small and were therefore used for the study. Convenience sampling was used because of the difficulty of using probability sampling such as simple random sampling to identify businesses in the informal sector in a developing economy like Ghana. The data were collected through personally administered surveys with the assistance of 10 teaching assistants. To ensure a high response rate the owners and/or managers were promised that any information they provided would not be shared with any person or organization and that only the members of the research team would have access to the data. After several visits to the selected businesses, 677 questionnaires were collected for a response rate of 67.7%. Of the 677 responses, 581 MSBs provided complete responses to all the relevant constructs in the questionnaire survey required for this study.

In order to minimize the problem of common method variance (CMV), the competitive strategy items were intermingled with the organizational capability and firm performance measures. Moreover, some of the scales were reversed, so that one end of the responses did not always correspond to a larger effect. Furthermore the owners and/or managers who responded to the questionnaire survey were assured of the anonymity of their responses and company information in any published document. These techniques have been used in other studies to minimize CMV problems (e.g. Acquaah, Amoako-Gyampah, & Jayaram, 2011; Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Citation2003).

Measurement of Variables

Firm performance (α = 0.9386)

Firm performance was measured as a multi-dimensional construct focusing on five items: sales growth, profit growth, net profit, sales revenue, and productivity growth. We solicited self-reported perceptual information on performance measures because the businesses were micro and small and operated predominantly in the informal sector. The owners and/or managers were asked to rate their businesses’ actual performance relative to their planned performance on the five items over the past three years on a seven-point scale ranging from (1) “much less” to (7) “much more”. This approach is a significant deviation from the existing studies that ask respondents to indicate their firm’s performance relative to competition. This approach is not applicable here as all the businesses operate in the informal sector and it is not possible for managers to assess their performance relative to competitors due to lack of official statistics on such businesses. A composite measure from the average of the five items was used to measure firm performance.

Organizational capabilities

Organizational capabilities were measured with two variables – managerial capabilities and marketing capabilities. Managerial capability: (α = 0.7781) was measured with six items, which were adapted from Spanos and Lioukas (Citation2001): skills and expertise in developing a clear operating procedure to run the business successfully; ability to allocate financial resources to achieve the firm’s goals; ability to coordinate different areas of the business to achieve results; ability and expertise to design jobs to suit staff capabilities and interest; and ability to attract and retain creative employees. For each of the items, the respondents were asked to indicate their firm’s strength in undertaking the activities relative to their competitors in the same product or service lines over the last three years on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from (1) “much weaker” to (7) “much stronger”. We then conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on the seven items to examine the discriminant validity of the managerial capability construct. The fit measures indicated a good fit with the observed covariance matrix as indicated in .

Table 1. Construct reliability and validity.

Marketing capability (α = 0:7815)

Marketing capabilities were measured with six items, which were adapted from the work of Vorhies and Harker (Citation2000), and Lado, Boyd and Wright (Citation1992). The items were as follows: ability to develop marketing information about specific customer need; ability to offer competitive pricing of the firm’s products and services and monitoring prices in the market; ability to design products that can meet customer needs; skills in focusing on customer recruitment and retention; ability to control access to distribution channels; and providing better after-sales-service capabilities. For each of the items, the respondents were asked to indicate their firm’s strength in undertaking the activities relative to their competitors in the same product or service lines over the last three years on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from (1) “much weaker” to (7) “much stronger”. Again, we performed a CFA on the six items to examine the discriminant validity of the marketing capability construct. The fit measures indicated a good fit with the observed covariance matrix as shown in .

Competitive strategy

Competitive strategy was measured with Porter’s generic strategy typology. We measured competitive strategy by using nine items from the competitive methods of the work of Dess and Davis (1984), which has been used extensively to operationalize competitive strategy (see Campbell-Hunt, Citation2000). The respondents were asked to assess the extent to which their businesses have placed emphases on the nine competitive methods over the past three years on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from (1) “much less” to (7) “much more.” To ensure that the items being used to measure competitive strategy represented the underlying constructs, we conducted a CFA of both cost-leadership strategy and differentiation strategy. Cost leadership strategy (α = 0.709) was assessed with five items: offering a broad range of products/services; ability to achieve operating efficiency; offering competitive pricing for products/services; control of operating and overhead costs; and achieving innovation in production process or service offering. A CFA using the five items to measure the cost leadership construct did indicate a good fit with the observed covariance matrix as indicate in . Differentiation strategy (α = 0.820) was measured with four items: developing new products/service offerings; upgrading or refining existing products/service; innovation in marketing products/services; advertising and promotion of products/services. When we conducted a CFA on the four items, the construct also indicated a good fit with the observed covariance matrix as shown in .

Competitive strategy-organizational capability interactions

To obtain the competitive strategy and organizational capability interaction variables, the comparative strategy and organizational capability variables were centered or de-meaned and the variables were multiplied. For example, to create the interaction between cost-leadership strategy and managerial capability, we multiplied both the centered variables of cost leadership strategy and managerial capability. It has been argued that centering the variables before interacting them reduces the possibility of multicollinearity among the variables in the estimation process (Aiken & West, Citation1991).

Control variables

The study controlled for firm age, firm size, and business type (whether the business is in manufacturing or service). Firm age was measured as the numbers of years since business started, using categorical measures as follows: 1 = 1–5 years; 2 = 6–10 years; 3 =11–15 years; 4 =16–20 years; and 5 = 21 and more years. Firm size was measured as the number of employees in the firm, using categorical measures as follows: 1 = 1–5 employees; 2 = 6–10 employees; 3 = 11–15 employees; 4 = 16–20 employees; and 5 = 21–30 employees, while Business type was measured as manufacturing (coded 1) or service (coded 2).

Reliability and Validity Analysis

The validity and reliability of the variables in the study were evaluated through the use of CFA and Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficients. The use of the constructs in previous studies provides evidence of the validity of the scales (Anand & Ward Citation2004). The Cronbach’s α coefficients of the measures, which range from 0.709 to 0.939, indicates that all the constructs are reliable. The reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s α) of the variables are shown in . As indicated earlier, we used CFA to examine convergent and discriminant validities. Convergent validity is typically considered to be satisfactory when items load high on their respective factors. All items loaded highly (greater than 0.40) on their respective factors, indicating that convergent validity is met. Discriminant validity was examined by making sure that the fit indices from the CFA models were satisfactory for each construct. The overall results showed that reasonable discriminant validities have been attained. Moreover, all the models used for the constructs suggest good fit as indicated by the indices (the Comparative Fit Index, the Tucker–Lewis Index, and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA)). The summary results of the CFA are presented in .

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics and correlations among the variables are shown in and respectively. There are significant correlations among some of the variables, especially the organizational capability and competitive strategy variables. However, our check of the variance inflation factors (VIF) indicated that the maximum was 5.34, which is less than the limit suggested by Neter, Kutner, Nachtsheim and Wasserman (Citation1996) of 10. Therefore, the problem of multicollinearity is minimized in the analysis.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

Table 3. Correlation matrix of variables.

To examine the hypotheses, we used the hierarchical multiple regression analysis (HMR) procedure to estimate the impact of our moderating variables (). The use of HMR was justified on the grounds that it can simultaneously allow for the exploration of the overlapping/interaction effect of competitive strategies and resource capabilities on performance. It is also used when you want to control for other variables.

Table 4. Standardized results of hierarchical linear regression.

The regression analysis involved the estimation of four hierarchically interconnected models. In Model 1, we regressed firm performance on the control variables. The results show that firm size and the age of the business contributes positively and significantly to the performance of MSBs. However, firm size showed a higher impact on firm performance (β = 0.291, p < 0.01) than firm age (β = 0.102, p < 0.05). In Model 2, we tested the direct impact of implementing competitive strategy (cost-leadership strategy and differentiation strategy) on the performance while controlling for firm size, age, and business type. The results show that both cost-leadership strategy and differentiation strategy significantly influence firm performance, with differentiation strategy having a stronger impact on performance (β = 0.386, p < 0.01) than cost leadership strategy (β = 0.187, p < 0.01). The change in Adjusted R2 due to the inclusion of the competitive strategy (ΔAdjusted R2 = 0.226, p < 0.01) shows that competitive strategy makes a significant contribution to the variations in performance for MSBs in Ghana. In Model 3, the organizational capability variables (managerial capability and marketing capability) were included in the estimation. Here again, the variations in performance were significantly affected following the inclusion of marketing and managerial capabilities. The results showed that both managerial capability and marketing capability have a significant and positive influence on the performance of MSBs. However, cost leadership strategy lost its significance with the inclusion of the organizational capability variables. The results further show that the two capabilities together explained 6.8% of the variance in firm performance, (Δ Adjusted R2 = 0 .066, p < 0.01).

In model 4, we introduce the interaction variables to test the hypotheses. In Hypothesis 1 (H1), we posit the managerial capability will positively moderate the relationship between cost-leadership strategy and firm performance. The result shows that the interaction between managerial capability and cost leadership strategy is positively related to the performance of MSBs in Ghana (β = 0.235, p < 0.01). Thus, H1 is supported. H2 posits that managerial capability will positively moderate the relationship between differentiation strategy and performance. The results from Model 4 show that managerial capability negatively moderates the relationship between differentiation strategy and performance (β = –0.135, p < 0.10). This is contrary to our prediction and H2 is, therefore, not supported. H3 states that marketing capability will positively moderate the relationship between differentiation strategy and performance. This is borne out by the analysis (β = 0.136, p < 0.05), supporting H3. H4 predicts that marketing capability will positively moderate the relationship between cost-leadership strategy and performance. The findings for H4 were contrary to our prediction. Marketing capability negatively moderated the relationship between cost-leadership strategy and performance (β = –0.117, p < 0.10). Thus, two of the hypotheses, H1 and H4, were supported. The interactive variables as a whole explained 2% of the variation in firm performance as indicated by the change in R2 (Δ Adjusted R2 = 0 .020, p < 0.01).

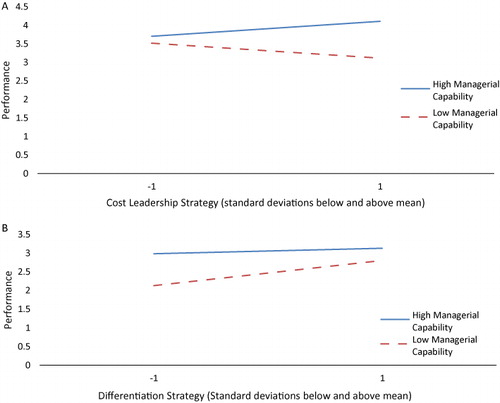

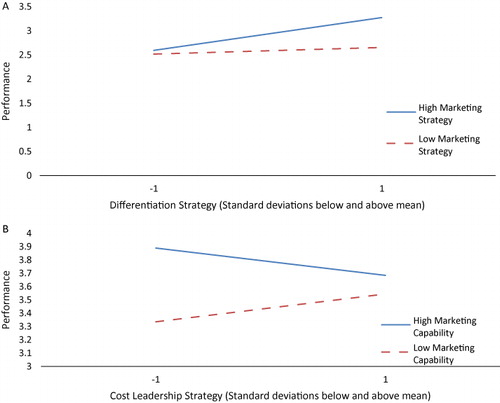

To determine the nature of the interactions, we plotted the relationships. To create the plots of the effects of competitive strategy (cost leadership and differentiation strategies) on performance, at different levels of managerial capability and marketing capability, we followed the procedure suggested by Aiken and West (Citation1991). We constrained all variables except managerial capability (in Model 4 for and ), and marketing capability (in Model 4 for and ) in to their mean values. Managerial capability and marketing capability then took the values of one standard deviation below the mean (low) and one standard deviation above the mean (high) at different levels (one standard deviation below the mean, and one standard deviation above the mean) of cost-leadership strategy and differentiation strategy. The moderating effects are shown in and presents the plots of the moderating effects of managerial capability on the relationship between competitive strategy (cost leadership and differentiation) and performance. As depicted in , and in congruence with H1, the effect of cost-leadership strategy on performance becomes more positive the higher the managerial capability of MSBs, but as shown in , the effect of differentiation strategy on performance becomes more positive the lower the managerial capability of MSBs, and the effect of the cost-leadership strategy on performance becomes more positive the higher the managerial capability of MSBs. The plots in are very similar to those in . shows that the effect of the differentiation strategy on performance becomes more positive the higher the marketing capability of MSBs. Conversely, indicates that the effect of cost leadership strategy on performance becomes negative at higher levels of marketing capability, while it increases at lower levels of marketing capability of MSBs.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Discussion

As pointed out earlier, the empirical evidence from the competitive strategy literature in both advanced industrialized and emerging economies indicates that the implementation of a coherent competitive strategy leads to superior performance. The literature also provides ample empirical evidence to support the RBV of the firm, which states that the resources and capabilities that are rare, valuable, and inimitable enable a firm to enhance and sustain its performance (Acquaah & Chi, Citation2007; Barney, Citation1991; Kelliher & Reinl, Citation2009). This study examines the moderating effects of organizational capability (managerial capability and marketing capability) on the relationship between competitive strategy and firm performance using survey data from micro and small businesses in Ghana. The findings provide mixed support for the hypothesized relationships. The findings suggested that the competitive strategies of cost leadership and differentiation influence the performance of micro and small businesses. These finding corroborate extant studies examining the relationship between competitive strategy and performance in transition and emerging economies (Acquaah, Adjei, & Mensa-Bonsu, Citation2008; Dadzie, Winston & Dadzie, Citation2012). The study further found that between the two competitive strategies investigated, MSBs in Ghana seem to benefit more from differentiation strategy than cost-leadership strategy, all things being equal. The findings also corroborated the organizational capability–performance relationship in microenterprises with both managerial and marketing capabilities enhancing the performance of MSBs (Masakure et al., Citation2009). We also find that superior managerial capability seems to have a greater impact on performance than marketing capability. However, several interesting and insightful findings were obtained from the moderating relationships with different capabilities augmenting the impact of different competitive strategies on performance.

Focusing on the effects of the interactions of organizational capabilities and competitive strategies on performance yielded the following findings. We found managerial capability to positively moderate cost-leadership strategy. Implementing cost-leadership strategy in the presence of organizational capability did not influence performance; however, when an MSB has a higher managerial capability, it is able to leverage those skills in effectively implementing the cost-leadership strategy. This may be due to the fact that the implementation of a cost-leadership strategy is not complicated and resource intensive, as the firm is just trying to create a product or service that is of similar value to its competitors (Porter, Citation1980). It is usually easier to enforce the characteristics of cost leadership such as tight cost control and evaluation systems, meeting of quantitative cost targets, and the close supervision and control of employees (Barney & Hesterley, Citation2006). This finding is interesting given that managerial capability also enhances performance. In a study of microenterprises in Ghana using data from the 1988/1999 Ghana Living Standards Survey (GLSS), Masakure et al. (Citation2009) were not able to find a relationship between the bundle of variables (including formal education and apprenticeship training) they call managerial skills or entrepreneurial resources and firm performance. They argue that the variables used to represent managerial skill and knowledge base may be poor proxies. Indeed, managerial capability goes beyond formal education and training to include the relevance of the skill to the activities being undertaken by the organization. Our findings show the utility of managerial capability in implementing a cost leadership strategy successfully.

We found, however, that managerial capability was detrimental to the implementation of differentiation strategy for the MSBs in Ghana. An explanation for this finding may be due to the fact that delivering products or services with unique features, which are the hallmark of a differentiation strategy, requires unique skills and competencies that are usually outside the reach of MSBs (Porter, Citation1980). Thus, the strong managerial competencies required for the effective implementation of the differentiation strategy are not available to MSBs. In fact, in most MSBs, most of the employees are non-hired labor or family members instead of hired labor, which tends to be more skilled, experienced, and productive (Akoten, Sawada, & Otsuka, Citation2006). For typical MSBs, which are usually entrepreneurial in nature, management structure may generally not be robust enough to successfully implement the differentiation strategy (Barney & Hesterly, 2006). Again, there could also be fundamental difficulties in augmenting managerial capabilities when the complexity of managerial roles increases as a result of the implementation of a differentiation strategy due to resource constraints. Moreover, MSBs may be unable to institute the required motivation packages that attract qualified skilled employees to the business. All these factors may affect the leveraging of managerial capability of MSBs in implementing the differentiation strategy.

The findings further show that marketing capability augments the effect of differentiation on the performance of MSBs in Ghana. This may be due to that fact that having marketing capability is important for implementing a differentiation strategy even for MSBs. This is because having and leveraging marketing capability is one of the foundations for building a competitive advantage via differentiation strategy (Grant, Citation2013). Moreover, MSBs with a high level of marketing capability are able to build trusted relationships with their customers with fewer resources; and are also better positioned to acquire first-hand information regarding their customer needs. MSBs are apt to use informal methods of communicating with their customers (Kelliher & Reinl, Citation2009), which lends itself to sharing information on the uniqueness of the products or services undertaken by the firm. Furthermore, MSBs leverage their marketing capability to make use of localized knowledge of the market to advertise and promote their products and services. These activities provide the opportunity for MSBs to emphasize their marketing capability in successfully implementing the differentiation strategy.

Having marketing capability, on the other hand, does not help in using the cost-leadership strategy to enhance performance of MSBs. Cost-leadership strategy is purposely implemented to cut down cost, encourage frills, and ensure efficiencies. Meanwhile, leveraging the marketing capability may be costly as it will involve intensive marketing activities, promotions, and other marketing strategies. Moreover, MSBs may not be well resourced to hire additional marketing experts and/or organize frequent training programs for their existing personnel to increase their capability. The findings may also indicate that marketing capability compensates for, rather than augments, a cost-leadership strategy on performance (Ortega, Citation2010). Note that cost-leadership strategy losses its significance when the organizational capability variables are introduced into the models (see Models 3 and 4), and also firm performance increases when marketing capability is low instead of high. Therefore the joint effect of marketing capabilities and differentiation strategy results in the lack of effective exploitation of the marketing capabilities and an unsuccessful execution of the cost-leadership strategy. This leads to a negative interaction effect on performance. Hence, MSBs may lack the ability and expertise to control costs that are associated with a marketing drive to optimize the allied benefits expected. It follows, then, that MSBs may find it difficult to achieve cost reduction and embark on intensive marketing activities at the same time.

Limitations and Future Research

Despite the insights gained from this study, the study has some limitations that future research should aim to overcome. First, the study used subjective measures of performance instead of objective measures. However, the nature of the firms’ surveyed for this study – micro and small businesses – made it impossible to use objective measures. There is enough evidence in the literature to show that subjective measures are valid since they are highly correlated with subjective measures (Wall et al., Citation2004). Second, the study relied on survey responses provided by only one informant for each of the MSBs. Obtaining responses from multiple informants would have been preferable but it was difficult to get multiple informants from the MSBs to complete the survey. Although single informants have been used effectively in strategy research in Africa, we encourage the use of multiple informants if it is feasible. Third, all the responses that were used to measure the constructs were obtained from one informant in each firm. The reported relationships may, therefore, be influenced by common method bias. However, we took several precautions to minimize any common method bias in the study (see Methods section). We will suggest that caution should be exercised in interpreting the findings. Fourth, we used cross-sectional data for the study so we cannot draw inferences about cause and effect from the findings. A study that explicitly uses longitudinal data would provide more robust conclusions concerning the direct effects of competitive strategy on performance and the effects of the interaction between competitive strategy and organizational capabilities (marketing capability and managerial capability) on performance for MSBs. Fifth, the study used data from Ghana, a small transition economy in sub-Saharan Africa, which obviously may affect generalizability of the findings to other African or transition economies. However, the findings may be generalized to several countries in Africa with social, economic, and institutional environments that are similar to those in Ghana.

Conclusion

There is a dearth of studies examining the role organizational capabilities play in the implementation of competitive strategy in micro and small businesses. This study is an attempt to fill that gap by investigating how organizational capabilities complement the implementation of competitive strategy in micro and small businesses in transition economies in sub-Saharan Africa. This study further uses data from micro and small businesses from both the informal and formal sectors in Ghana to test the hypotheses. The findings showed that while a differentiation strategy enhances performance for MSBs, a cost-leadership strategy does not. However, the findings from the study demonstrate that managerial capability plays a synergistic role in the implementation of a cost-leadership strategy by MSBs. Thus, when MSBs have strong managerial capabilities, there are performance benefits to the implementation of cost-leadership strategy. The findings further indicate that marketing capabilities augment the value of the implementation of differentiation strategy for MSBs. The implications from the findings point to a contingency approach to the implementation of competitive strategy by MSBs. MSBs that are intent on implementing a competitive strategy should evaluate to make sure they have the appropriate capabilities for their chosen competitive strategy. If MSBs would like to derive greater benefits from the implementation of a differentiation strategy they should make sure that they have the requisite marketing capabilities. This may include a reliance on creating customer loyalty and trust. Conversely, MSBs that would like to benefit from the implementation of the cost leadership strategy should make sure they have the managerial competencies to obtain the skills, expertise, and requirements necessary for effectively driving down cost in all areas of their business activities. We hope that this study has contributed positively to the role of organizational capabilities in the competitive strategy–performance relationships in MSBs.

REFERENCES

- Abor, J., & Quartey, P. 2010. Issues in SME development in Ghana and South Africa. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics, 39: 218–28.

- Acquaah, M. 2003. Corporate management, industry competition and the sustainability of firm abnormal profitability. Journal of Management and Governance, 7: 57–81.

- Acquaah, M. 2011. Business strategy and competitive advantage in family businesses in Ghana: The role of social networking relationships. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 16(1): 103–126.

- Acquaah, M., Adjei, M. C., & Mensa-Bonsu, I. F. 2008. Competitive strategy, environmental characteristics and performance in African emerging economies: Lessons from firms in Ghana. Journal of African Business, 9(1): 93–120.

- Acquaah M., Amoako-Gyampah, K., & Jayaram, J. 2011. Resilience in family and nonfamily firms: An examination of the relationships between manufacturing strategy, competitive strategy and firm performance. International Journal of Production Research, 49(18): 5527–5544.

- Acquaah, M., & Chi T. 2007. A longitudinal analysis of the impact of firm resources and industry characteristics on firm-specific profitability. Journal of Management and Governance, 11: 179 –213.

- Acquaah, M., & Yasai-Ardekani, M. 2008. Does the implementation of a combination competitive strategy yield incremental performance benefit? A new perspective from transition economy in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Business Research, 61: 346–354.

- Adner, R., & Helfat, C. E. 2003. Corporate effects and dynamic managerial capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 24: 1011–1025.

- Agyapong, A., & Boamah, R. 2013. Business strategies and competitive advantage of family hotel businesses in Ghana: The role of strategic leadership. Journal of Applied Business Research, 29(2): 531–544.

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. 1991. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Akoten, J. E., Sawada, Y., & Otsuka, K. 92006. The determinants of credit access and impacts on micro and small enterprises: The case of garment producers in Kenya. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 54(4): 927–944.

- Amit, R., & Schoemaker, P. J. 1993. Strategic assets and organisational rent. Strategic Management Journal, 14(1): 33–46.

- Anand, G., & Ward, P. T. 2004. Fit, flexibility and performance in manufacturing: Coping with dynamic environments. Production and Operations Management, 13: 369–385.

- Ayyagari, M., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. 2011. Small vs. young firms across the world: Contribution to employment, job creation, and growth. Policy Research Working Paper 5631. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Barney, J. B. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1): 99–120.

- Barney, J. B., & Hesterley, W. S. 2006. Strategic management and competitive advantage: Concepts. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Barney, J. B., Wright, M., & Ketchen, D. J. 2001. The resource-based view of the firm: Ten years after 1991. Journal of Management, 27(6), 625–641.

- Beaver, G., & Jennings, P. 2005. Competitive Advantage and entrepreneurial power: The dark side of entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 12(1), 9–15.

- Bowman, C., & Ambrosini, V. 1997. Perceptions of strategic priorities, consensus, and firm performance. Journal of Management Studies, 34: 241–258.

- Camison, C., & Villar-Lopez, A. 2010. Effects of SMEs’ international experience on foreign intensity and economic performance: The mediating role of internationally exploitable assets and competitive strategy. Journal of Small Business Management, 48(2): 116–151.

- Campbell-Hunt, C. 2000. What have we learned about generic competitive strategy? A meta-analysis. Strategic Management Journal, 21: 127–154.

- Chang, W., Park, J. E., & Chaiy, S. 2010. How does CRM technology transform into organizational performance? A mediating role of marketing capability. Journal of Business Research, 63: 849–855.

- Dadzie, C. A., Winston, E. M., & Dadzie, K. Q. 2012. Organizational culture, competitive strategy, and performance in Ghana. Journal of African Business, 13(3): 172–182.

- Daily, C. M., & Dollinger, M. J. 1993. Alternative methodologies for identifying family versus nonfamily managed business. Journal of Small Business Management, 31(2): 79–90.

- Day, G. S. 1992. Marketing’s contribution to the strategy dialogue. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 20(4): 323–329.

- Day, G. S. 1993. The capabilities of market-driven organisations. Report No. 93–123. Cambridge, MA: Marketing Science Institute.

- Day, G. S. 1994. The capabilities of market driven organisations. Journal of Marketing, 58: 37–52.

- De Sarbo, W., Di Benedetto, C., & Song, M. 2007. A heterogeneous resource based view for exploring relationships between firm performance and capabilities. Journal of Modeling in Management, 2(2): 103–130.

- Dess, G. G., & Davis P. S. 1984. Porter’s (1980) generic strategies as determinants of strategic group memberships and organizational performance. Academy of Management Journal, 27: 467–488.

- Fatoki, O., & Garwe, D. 2010. Obstacles to the growth of new SMEs in South Africa: A principal component analysis approach. African Journal of Business Management, 4(5): 729–738.

- Fernandez, Z., & Nieto, M. J. 2005. Internationalization strategy of small and medium-sized family business: Some influential factors. Family Business Review, 18(1): 77–89.

- Frambach, R., Prabhu, J., & Verhallen, T. 2003. The influence of business strategy on new product activity: The role of market orientation. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 20: 377–397.

- Gonzalez-Benito, O., Gonzalez-Benito, J., & Munoz-Gallego, P. 2009. Role of entrepreneurship and marketing orientation in firms’ success. European Journal of Marketing, 43(3): 500–522.

- Grant, R. M. 2013. Contemporary strategy analysis. 8th ed. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

- Graves, C., & Thomas, J. 2006. Internationalization of Australian family businesses: A managerial capabilities perspective. Family Business Review, 19(3): 207–224.

- Habbershon, G. T., & Williams, M. L. 1999. A resource-based framework for assessing strategic advantage of family firms. Family Business Review, 12: 27–39.

- Hooley, G., Fahy, J., Cox, T., Beracs, J., Fonfara, K., & Snoj, B. 1999. Marketing capabilities and firm performance. Journal of Market Focused Management, 4(3): 259–278.

- Hoskission, R. E., Ireland, R. D., & Hitt, M. A. 2011. Strategic management: Competitiveness and globalization. 9th ed. Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning.

- Johnson, G., Melin, L., & Whittington, R. 2003. Micro-strategy and strategising. Journal of Management Studies, 409(1): 3–22.

- Kanyabi, Y., & Devi, S. 2011. Use of professional accountants’ advisory services and its impact on SME performance in an emerging economy: A resource-based view. Journal of Management and Sustainability, 1(1): 43–55.

- Kelliher, F., & Reinl, L. 2009. A resource-based view of micro-firm management practice. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 16(3): 521–532.

- Kim, E., Nam, D., & Stimpert, J. L. 2004. Testing the applicability of Porter’s generic strategies in the digital age: A study of Korean cyber malls. Journal of Business Strategies, 21: 19–45.

- Lado, A. A., Boyd, N. G., & Wright, P. 1992. A competency-based model of sustainable competitive advantage: Toward a conceptual integration. Journal of Management, 18: 77–91.

- Li, J. J., Zhou, Z. K., & Shao, A. T. 2009. Competitive position, managerial ties and profitability of foreign firms in China: An interactive perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(2): 339–352.

- Liberman-Yaconi, L., Hooper, T., & Hutchings, K. 2010. Toward a model of understanding strategic decision-making in micro-firms: Exploring the Australian information technology sector. Journal of Small Business Management, 48(1): 70–95.

- Lippman, S., & Rumelt, R. P. 1982. Uncertain imitability: An analysis of interfirm differences in efficiency under competition. Bell Journal of Economics, 13: 418–438.

- Littunen, H. 2003. Management capabilities and environmental characteristics in the critical operational phase of entrepreneurship: A comparison of Finnish family and non-family firms. Family Business Review, 16(3): 183–190.

- Lu, J. W., & Beamish, P. W. 2001. The internationalization and performance of SMEs. Strategic Management Journal, 22: 565–586.

- Madrid-Guijarro, A., Garcia-Perez-de-Lema, D., & Van Auken, H. 2013. An investigation of Spanish SME innovation strategy during different economic conditions. Journal of Small Business Management, 51(4): 578–601.

- Masakure, O., Henson, S., & Cranfield J., (2009. Performance of microenterprises in Ghana: A resource-based view. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 16(3): 466–484.

- Mensah, J. V., Tribe, M., & Wess, J. 2007. The small-scale manufacturing sector in Ghana: A source of dynamism or of subsistence. Journal of International Development, 19: 253–273.

- Miller, A., & Dess, G. G. 1993. Assessing Porter’s (1980) model in terms of its generalizability, accuracy and simplicity. Journal of Management Studies, 30: 553–585.

- Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. 1994. The commitment–trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3): 20–38.

- Morgan, N. A., Slotegraff, R. J., & Vorhies, D. W. 2009. Linking marketing capabilities with profit growth. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 26(4): 284–293.

- Newbert, S. L. 2007. Empirical research on the resource-based view of the firm: An assessment and suggestions for future research. Strategic Management Journal, 28: 121–146.

- Neter, J., Kutner, M. A., Nachtsheim, C. J., & Wasserman, W. 1996. Applied linear statistical models. 4th ed. Chicago, IL: Irwin.

- Obeng, B. A., & Blundel, R. K. 2015. Evaluating enterprise policy interventions in Africa: A critical review of Ghanaian small business support services. Journal of Small Business Management. doi:10.1111/jsbm.12072.

- Orr, L. M., Bush, V. D., & Vorhies, D. W. 2011. Leveraging firm-level marketing capabilities with marketing employee development. Journal of Business Research, 64: 1074–1081.

- Ortega, M. J. R. 2010. Competitive strategies and firm performance: Technological capabilities’ moderating roles. Journal of Business Research, 643: 1273–1281.

- Osei, B., Baah-Nuakoh, A., Tutu, K. A., & Sowa, N. K. 1993. Impact of structural adjustment on small-scale enterprises in Ghana. In A. Helmsing, & T. H. Kolstee (Eds.), Structural adjustment, financial policy and assistance programmes in Africa. London: Intermediate Technology Publications.

- Peteraf, M. A. 1993. The cornerstones of competitive advantage: A resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal, 14(3): 179–191.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology Bulletin, 88(5): 879–903.

- Porter, M. E. 1980. Competitive strategy: Techniques for analyzing industries and competitors. New York: Free Press.

- Porter, M. E. 1985. Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performances. New York: Free Pres.

- Robson, P. J. A., Haugh, H. H., & Obeng, B. A. 2009. Entrepreneurship and innovation in Ghana: enterprising in Africa. Small Business Economics, 32(3): 331–350.

- Shepherd, D. A., & Wiklund, J. 2005. Entrepreneurial small businesses: A resource-based perspective. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Slotegraff, R. J., & Dickson, P. R. 2004. The paradox of a marketing planning capability. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(4): 371–385.

- Spanos, Y., & Lioukas, S. 2001. An examination into the causal logic of rent generation: Contrasting Porter’s competitive strategy framework and the resource-based perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 22(10): 907–934.

- Spanos, Y. E., Zaralis, G., & Lioukas, S. 2004. Strategy and industry effects on profitability: Evidence from Greece. Strategic Management Journal, 25; 139–165.

- Steel, W. F., & Webster, L. 1990. Ghana’s small enterprise sector: World Bank, industry and energy. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Storey, J. 1994. Understanding the small business sector. London: Thomson.

- Vorhies, D. W., & Harker, M. 2000. The capabilities and performance advantages of market driven firms. Australian Journal of Management, 25(2): 145–171.

- Vorhies, D. W., & Morgan, N. A. 2005. Benchmarking marketing capabilities for sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of Marketing, 69(1): 80–94.

- Vorhies, D. W., Harker, M., & Rao, C. P. 1999. The capabilities and performance advantages of market-driven firms. European Journal of Marketing, 33(11/12): 1171–1202.

- Wall, T.D., Michie, J., Patterson, M., Wood, S. J., Sheehan, M., Clegg, C. W., & West, M. 2004. On the validity of subjective measures of company performance. Personnel Psychology, 57: 95–118.

- Weerawardena, J. 2003. Exploring the role of market learning capability in competitive strategy. European Journal of Marketing, 37(3/4): 407–429.

- Wernerfelt, B. 1984. A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2): 171–180.

- World Bank. 1992. Malawi: Financial sector study. Washington, DC: World Bank.