Abstract

Through a series of three vignettes, each of us critically reflects on how the visual arts have come to inform our geographical questions and approaches, illustrating the possibilities for art and experimentation as geographical practice. We outline common threads that run through our individual work, including our approaches to process and experimentation; our orientations towards the use, making, and reimagining of tools; and how we make spaces and time for art practice. Individually, we offer vignettes that capture and document fragments of our own practices that connect critical making, visual arts, cartography, and geographic inquiry. Collectively, our vignettes offer a gallery of possibilities for art and experimentation in geographical scholarship and pedagogy. By sharing our practices collectively, we aim to generate conversation that simultaneously recognizes connectivity and difference among these practices, while situating art and experimentation as modes of geographical inquiry and knowledge production.

通过三个研究片段, 我们批判性地反思了视觉艺术如何帮助我们去理解地理问题和方法, 展示了艺术和实验成为地理实践的可能性。我们概述了这三个研究的共同点:如何开展实验, 如何对工具进行使用、制造和重新构想, 如何创造艺术实践的空间和时间。这三个研究, 捕捉和记录了我们的个人实践, 衔接了批判性创作、视觉艺术、制图和地理探究。我们的研究, 展示了艺术和实验在地理研究和教学中的可能性。通过分享实践, 我们旨在意识到这些实践之间的联系和差异, 将艺术和实验作为地理研究和知识生产的模式。

Por medio de una serie de tres viñetas, cada uno de nosotros reflexiona críticamente sobre el modo como las artes visuales han llegado a informar nuestros interrogantes y enfoques geográficos, ilustrando las posibilidades para el arte y la experimentación como práctica geográfica. Hacemos un esbozo de los hilos conductores de nuestro trabajo individual, incluyendo nuestros enfoques al proceso de experimentación; nuestras orientaciones hacia el uso, la creación y la reimaginación de herramientas; y cómo construimos espacios y tiempo por la práctica del arte. Individualmente, ofrecemos viñetas que captan y documentan fragmentos de nuestras propias prácticas, que conectan la creación crítica, las artes visuales, la cartografía y la investigación geográfica. De manera colectiva, nuestras viñetas ofrecen una galería de posibilidades para el arte y la experimentación en la erudición y en la pedagogía geográficas. Al compartir colectivamente nuestras prácticas, apuntamos a generar una conversación que a un tiempo reconozca la conectividad y las diferencias entre estas prácticas, situando al mismo tiempo el arte y la experimentación como modos de indagación geográfica y producción de conocimiento.

In this article, we critically reflect on how visual arts have come to inform each of our individual practices as geographers. While each of our paths connecting visual arts and geography are varied, in this introduction we identify key themes that connect our practices, highlighting the possibilities we see in such hybrid practices. While our ability to engage with this kind of work is made possible by the discipline’s support of visual and creative practices (Hawkins Citation2014), we seek to suggest generative directions for geographic engagements with art. In other words, we see in art a wealth of possibilities for spatial inquiry and knowledge production. We hope that critical reflection on our own practices may serve as inspiration for other experimental visual practices that build on scholarship within and beyond geography. In the set of vignettes that follow, each of us, in turn, reflects on our own attempts to connect critical making, visual arts, cartography, and geographic inquiry. While each vignette was written individually, through ongoing conversations about our work, we have identified a series of themes that resonate across our practices. These themes first emerged in our discussions at the 2019 AAG meeting, in the “Creative Geovisualisation” panel organized by Philip Nicholson and chaired by Deborah Dixon and have continued through the writing of this article. Those themes include our approaches to process and experimentation; our orientations towards using, making, and reimagining tools; and how we make spaces and times for visual practices.

In our experience, research is always a fraught process of experimentation. Engagements with artistic practice often reorient how we approach experimentation in relation to geographical problems. As geographers, we confront relational problems that emerge from diverse materialities. Through these engagements, we recognize our inability to make sense of it all, which comes forth in the language of contingency and complexity and the recognition of the profound and always shifting relationalities that make space. Indeed, we are living in a “weighted and reeling present” that resists easy explanations or singular narratives (Stewart Citation2007, 1), which leads us to ask: how might we intervene not just through critical study, but also at the level of materiality? Art invites this sort of experimentation and play, offering different lenses through which to engage geographic problems—lenses invested in not only interpreting problems, but also engaging with their material relations. Here we might understand experimentation in two ways. First, as Trevor Paglen (Citation2008) writes, experimental geography can be understood as a set of artistic practices concerned with “experimenting with the production of space as an integral part of one’s own practice” (31). In other words, space, here understood as a set of emergent materialities, is engaged through processes of experimentation that intervene in and remake those spaces. Second, we might understand experimentation through Karen Barad’s (Citation2007) writing on experimental apparatuses of science. Barad writes, “apparatuses are not mere observing instruments but boundary-drawing practices—specific material (re)configurings of the world—which come to matter” (140). For Barad, the boundary-drawing practices of experimental apparatuses (which are initially theorized through scientific practice but come to include myriad social practices) are the processes through which phenomena and materiality emerge. In other words, the apparatuses through which we engage the world—which might include computational media, pencils and paper, social science surveys, or geographical information systems (GIS)—brings that world forth differently, constituting what we might understand as “reality.” This drawing of boundaries, which determines how “matter comes to matter” (Barad Citation2007, 152), could always happen otherwise. How might the experimental redrawing of map iconography (see Meghan’s vignette) or the reappropriation of scientific data (see Philip’s vignette) result in different orientations to phenomena and materiality? Experimentation and play might lead us to different relational understandings as we are surprised by the connections and alliances that emerge through shifting modes of engagement with various phenomena. In the vignettes below, we outline our individual processes of experimentation, which often involve experimenting and reimagining what is possible with boundary-drawing tools close at hand.

Our vignettes reveal tensions within, re-orientations towards, and newly built alternative tools within our art practices. Critical mapping scholars, ourselves included, grapple with how digital spatial technologies contribute to colonial projects (Rose-Redwood et al. Citation2020), reinforce systems of oppressions (Benjamin Citation2019), and work in the service of state power (Jefferson Citation2017). Despite legacies and tensions baked within our practice and tools, Sarah Elwood (Citation2006) notes that the stakes are too high to completely ignore the tools that have been used to oppress. We can reorient these technologies and epistemologies by first recognizing the legacies and impacts of our tools as well as our relationship to them. To those ends, our work re-appropriates tools to productively work within these tensions, not to circumvent such legacies but to generate new dimensions and ruptures from within these contradictions. For example, Meghan generates alternative graphic vocabularies from existing tools and techniques to differently convey lived experiences and the power relations that shape them.

Our visual art practices often find a “home” within and adjacent to geography’s mapping traditions owing to their deep engagements with aesthetic concerns. While mapping provides art practices with a legible point of entry into the discipline, our interests in art and experimentation extend well beyond their engagements with maps. In other words, while maps might be a common point of intersection for us, we also want to think through how experimental engagements with materiality might extend into other modes of spatial inquiry. Discourses in mapping, however, have been generative in our individual practices and how our paths intersect with maps have been varied. Nick and Philip were trained in the visual arts before finding cartography; in contrast, Meghan found her art practice through academic cartography. At times, our relationships between art and cartography have been fraught. Coming from a visual arts background, for example, Nick grappled with cartography’s moniker as both an art and science, a moniker that is too often imbalanced by rule-laden scientific mapmaking. Whereas Meghan does not identify as an artist (although she is slowly being convinced otherwise) but has similarly confronted the limits of existing cartographic practices.

We often find inspiration at the margins of cartographic traditions and GIScience. These margins are vibrant, and we draw inspiration from their intersections and emphasis on expressive vocabularies, questions of power, and attention to process. Recently, there have been a number of interdisciplinary collaborations that use mapping not as a simple means of representation, but rather, as a mode of political intervention (Mogel Citation2011). In their work with the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, Manissa Maharawal and Erin McElroy (Citation2018), for example, insist on the need for countermapping to go beyond merely representing political issues, but to actually contribute to activist movements. In their work, they grappled with the reductionist representational tendencies of maps by engaging with the complex materialities and politics that connect maps to activist movement building. In projects like these, we can see a move towards more-than-representational approaches to mapping, where other materialities and situated positionalities are engaged. In this context, following Joanna Drucker (Citation2020) we might understand mapping and visualization in a humanistic register—as a form of knowledge production itself, or what Drucker terms “visual epistemology.” In other words, maps have the potential to not only act as representations of phenomena, but to be active participants in the production of knowledge (Drucker Citation2020). In artistic practice and experimentation, we find a similar engagement with different modes of knowledge production that exceed the tools we choose to engage.

While recognizing the default assumptions and prescriptive methods within any tools or technology, we collectively demonstrate a decentering of tools and a recentering of processes. In the classroom, this approach emphasizes concepts over points, clicks, and code (Knowles Citation2000; Elwood and Wilson Citation2017). Outside of the classroom, we gravitate towards tools and technology that fit our particular contexts as opposed melding our contexts to specific tools. Nick, for example, expounds on these concepts by repurposing tools in unexpected ways or ways they were never intended to be used (Lally Citation2022a). This includes exploring possibilities for tools that reimagine engagements with geographical concepts and technologies). For example, Nick (Lally Citation2022b) challenges the limitations of mapmaking software by asking “what can GIS do?” (emphasis added). This question presupposes that we do not yet know (and, perhaps, will never know) the expansive potentialities of GIS without exploring the material possibilities of GIS as well as socio-technological relations between ourselves and our tools. Below, Philip illuminates such possibilities by building new tools for design and mapping and new relationships with the machines at our fingertips. Taken together, our vignettes approach our tools—their limitations and possibilities abound—as new horizons and sites for deeper exploration.

On the one hand, this work looks to reimagine and reconstitute the traditional and established spaces of geographical research and pedagogy (i.e., the classroom, the archive, the computer lab, the remote field site). Conventional spaces and approaches are appropriated, occupied, reconfigured, misused, and so on, giving way to more interventionary practices (Hawkins, Citation2015). Meghan explores the classroom and workshops as sites for feminist intervention by emphasizing processes over products, centering power relations and situated knowledges, and disrupting individualized pedagogical norms through collective creative practice. On the other hand, we seek to broaden the scope of what is understood as the place for geographic knowledge production and discourse. As an example, Philip re-envisions laboratories as sites that blur artistic and scientific experimentation. These sites present opportunities for dialogue with histories and cultures of practice differently established and constituted to that of the geography laboratory, classroom, or field site. Similarly, how time and attention is imagined and valued both within and beyond geographic scholarship, research, and teaching is often governed by institutionally produced priorities. For instance, what is a good use of time? For example, Philip, in their creative experiments with GIS, intentionally left themselves open to producing nothing at all. How are the outcomes of such projects measurable within the framework of promotion and tenure? What is time well spent within institutional contexts? The kinds of research practices outlined in the sections below often shirk established norms of how “science,” “research,” and “education” is supposed to play out. We attend to time differently, playing with the conventions of how time is understood as a delimiter of attention and knowledge production, sometimes slowing down and sometimes speeding up, making time for creativity to happen (or even fail).

In this introduction, we have read across our individual practices to identify and theorize some unifying themes. Our backgrounds, circumstances, and positions in relation to broader power structures, however, differentially shape our practices as well as our collaborations, teaching, and research. In the reflective vignettes that follow, the differences in our practices become evidently clear as our voices, approaches, pacing, and the very structure of our vignettes shift in attunement with our art practices and modes of geographic inquiry. Because of this, like the order of our names, the three vignettes can be read in any order. First, Philip assesses how his own creative geographic practice has formed through interaction with different disciplines and intellectual fascinations. Second, Meghan documents the development of her artistic practice from cartographic expression in the classroom to feminist mapping and collaborative workshops. Finally, Nick reflects on his art practice and how it informed his shift to geography.

GETTING TO “CREATIVE GEOVISUALISATION”

By Philip Nicholson

There is a hybridity to my skillset that in some ways eschews disciplinary classification, and in other ways has found a productive context in academic geography. I came to my PhD in Human Geography a creative practitioner with an undergraduate degree in Fine Art and a master’s degree in Spatial and Narrative Design. At this point my practice had shifted from the domain of formal and conceptual sculpture and installation towards narrative and the principles of museum and exhibition design. I frequently reflect upon this journey, asking myself—technical skillsets, conceptual frameworks, and disciplinary registers aside—what are the fascinations, sticking points, centres of gravity, or intellectual fetishes, that have driven and persevere throughout these shifts in context?

Making Sense of Interdisciplinarity

I often find myself fixated on how colleagues and collaborators from different fields of research and practice, embody, and deploy their disciplinary expertise. I am fascinated by how these are constructed, in academic and vocational training, experience, and practice. I am interested in the ways in which individuals come to imagine the world, conceptualise or construct particular ways of seeing. My collaboration with astrophysicists at the Institute for Gravitational Research (IGR) () involved references to certain established histories, and tried and tested metaphors, and analogy.

FIGURE 1 Touching Space-Time was a research project cum curated installation that I undertook at the beginning of my PhD studentship at the University of Glasgow. As part of the installation, I made a three-channel video installation entitled Nature’s Undiscovered Window, that focused on how the physicists from IGR seek to communicate their theoretical observations, practices and insights.

For the IGR project, I took the form of what Hawkins calls “art as a ‘lab’ for sensory exploration” (Hawkins Citation2013, 60). That is, I was interested in exploring the notion of art as a laboratory, such that particular sites can become a focus for creative as well as scientific experimentation. Specifically, I wanted to explore the way theoretical and experimental physicists investigate cosmic events (neutron star collisions, supernovae explosions, ripples in the fabric of spacetime) that are “intangible,” but that can be translated into sensible forms via various technologies and, moreover, how this investigatory process can itself be translated into creative forms associated with the arts such that diverse, often unpredictable, affects can be generated. shows the works created by me as through the lens of my art practice I strove to make sense, or code my exchanges with astrophysicists at IGR via the mediums of video, storytelling, and installation.

Creating Space for Experimentation

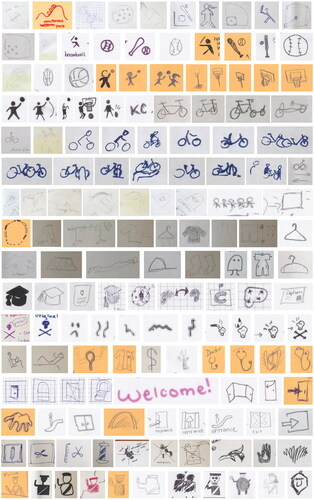

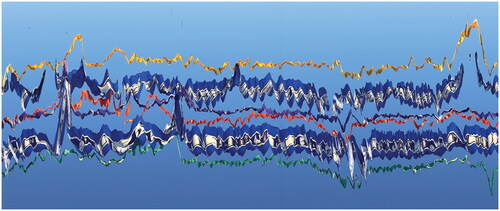

The remit of my PhD project was to critically interrogate the question of “what are” Geographical Information Systems (GIS) from an arts and humanities perspective, and to contribute to the emergence of what scholars have called a “third stage,” or “creative” GIS (Sui Citation2004). There was a clear context within the academic literature for my PhD project, but this remit was very much fed through my own practice-based approach and the hybridity of my disciplinary training. A key manoeuvre here was to create space for creative experimentation (). To do this I set myself the loose objective of creating at least one kind of creative response per day (with the implicit expectation that some days I would intentionally take myself down dead ends), taking a charrette-like approach (a method used by architects and designers that involves working intensively and rapidly) creating doodles, sketches, video clips, and staging small re-enactments of practices I had observed in previous research activities. The intention here was to think through my research findings via the lens of my own creative practice. Repurposing, repositioning, creating taxonomies, rehearsing processes, drawing attention to tech heaviness, repetition, grid ontologies, mundanities, using different visual registers. Here, I deployed my method of creative practice to work through the abundance of materials, insights, and feelings that I had amassed over the course of the project.

FIGURE 2 As part of my PhD, I worked for a period of two weeks on a series of creative experiments drawing from and reflecting upon fieldwork data collected using conventional social science methods of observation, interview, and autoethnography, figuring them as a kind of creative reservoir for creative experimentation.

This period of creative experimentation brought to light specific aesthetic touch points that resonated with me in learning to do, and think about, GIS. For me, this project became a matter of interfacing, between GIS as a broad discipline and my creative and aesthetic sensibilities. A significant endeavour for me in carrying out this project was working out how mine was a legitimate perspective from which to cast a rendering of what GIS is—to be a producer of knowledge in this field that I am not traditionally invested in. To be sure, a series of tensions unfolded as I reworked and repurposed my particular understanding of terms such as “rendering,” my attraction and articulacy to aesthetic forms such as narrative, and my propensity to immerse myself in activities such as doodling and playing with technology. All of these became strange, and then familiar again as I became part of GIS.

Between “Dialogues and Doings”

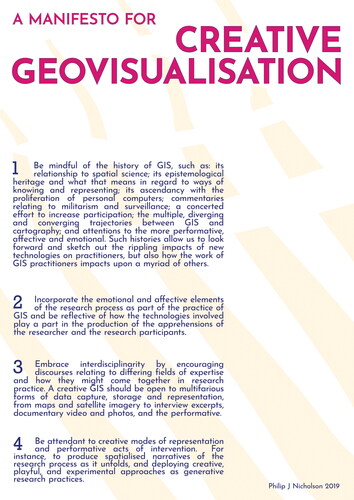

The dichotomy outlined by Harriet Hawkins (Citation2011) as “dialogues and doings” as modes of practice employed by the “creative geographer” seems to be a good fit for my research practice. For example, this manifesto () was an opportunity for me to take stock, to distil the scholarship that had gone before, to create a snapshot at the end point of my PhD. In short, this was the setting of a research agenda. At the same time, I see this as an artwork, a provocation, a way of coding a type of creative practice following the tradition of artist manifestos. I am at once creating “dialogue” with the scholarly canon of critical GIS, and “doing” in making a graphic form (in this case a poster).

“Playing in the Field”

Much of my recent work has focused on developing creative geovisualisation as a methodology of working collaboratively and creatively to map social and environmental data sets on human environment relations and environmental change predominantly in post-independence and post-colonial contexts. depicts some of the research activities carried out with refugees living in Dzaleka Camp in Malawi in January 2020. What was novel about our research activities was how we chose to supplement methods of citizen science data collection with playful approaches that fostered deeper engagement with our participants (Haklay Citation2013).

FIGURE 4 Hacking Citizen Science Project with refugees at Dzaleka Camp in Malawi—In January 2020 I spent a month working with refugees and testing water, soil, and air quality around the camp. A set of other research activities were built around environmental data collection including a data analysis session, participant led mobile interviewing, a short-video making project, and a hack the method workshop.

In “playing in the field” and much of what has become my own creative geographic practice I follow the work of feminist geographer Cindy Katz as described in, “Playing the field” (Katz Citation1994) in embracing multiplicity and shifting contexts in creative practices and geographic fieldworking and scholarship. As such, participants (in this case) were invited to join in playful and experimental approaches that I use in my research practice. This included a hack-the-method workshop in which we looked to investigate the materials of scientific knowledge production through practices of disassembly and remaking (literally breaking and sticking back together) in order to foster intense moments of focus and immersion in the materials outside of their intended use. Key to our participants’ creative contributions to the project was the contribution of their narratives of the site and reflections on the research process as it unfolded. And so, participants led mobile interviews to create spatialised video geonarratives (SVG see Curtis et al. Citation2019) with me, and each other, throughout the project and produced their own 3-minute videos.

In Summary

I have a prevailing fascination with visual culture and practices that produce images and artworks. And my research practice is adapted from and informed by what went before in terms of my art and design education. My research methodologies are often led by processes of making, experimentation, and play serving as provocations for research participants and collaborators to engage in dialogue, and paying attention to the aesthetics and affordances of geospatial technologies (Nicholson Citation2022). A key characteristic of my practice is a resistance to what we understand as the finished or “fixed” art object. I find that what is valuable in the making or doing is often lost. That is, I feel it is important to be attendant to how things are always in a process of becoming. I find parallels between participatory art practices (see Bourriaud Citation2002 on “Relational Aesthetics”)—mindful and contingent of the agency of others—and work in critical cartography and GIS that position the map, or “mappings” and, “ontogenetic in nature (always in the process of becoming)” (e.g., Kitchin et al. Citation2013, 481).

I find working in-between—as an outsider and an insider—affords me a useful perspective on how sense-making assemblages from scientific disciplines to creative practices and the telling of lived experience, produce the world in different ways. I am interested in how collaborative practices involving discussion, storytelling, and experimentation (Nicholson Citation2019) with other researchers and research participants allows us to unpack and reflect and create together.

FEMINIST CREATIVE PRACTICE

By Meghan Kelly

Creative Practice and Pedagogy

Creative practice in mapping began for me in the classroom, where the focus was on cartographic expression and process, not simply singular static outputs. This attention towards expression and process was bolstered by experimenting and learning predominantly within graphic design software instead of GIS or mapping software. The malleability of graphic design software opened creative possibilities outside of the bounds of default and often constrained map design options in GIS. This approach revealed maps and mappings as the curation of graphic vocabularies that expand imaginaries, illuminate narratives, and build alternative ways of knowing.

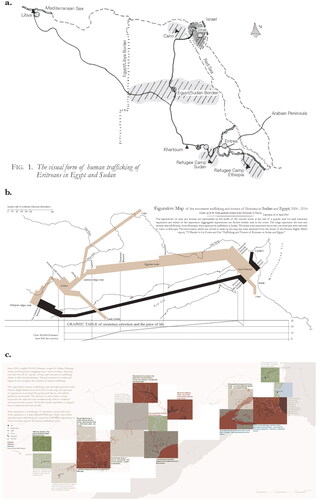

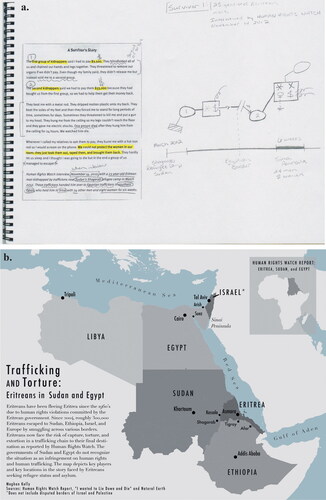

For me, pedagogy for creative mapping blurs mapping/writing, making/remaking, and trial/error. My class project, Human Trafficking in Sudan and Egypt: Mapping Traumatic Experience through Multiple Lenses, began with writing ( and ). Writing and reflection uncovered my frustration with conventional mapping techniques (e.g., flow lines) that present trafficking stories as disembodied and removed from the realities on the ground, especially when paired with intense written stories and imagery. I wanted to build graphic vocabularies and mapping techniques to better convey the gravity of the stories being shared in a Human Rights Watch (HRW) report on Eritrean human trafficking (Simpson Citation2014). Drawing inspiration from humanistic and narrative cartographies, I adopted a process-based and iterative design approach translating these stories into graphical marks.

FIGURE 5 Relational sketch maps documenting the human trafficking of Eritreans writ large (a) and individual trafficking stories (b). These sketch maps captured people, places, and events as well as tensions, emotions, and trauma. I then mapped these stories using conventional symbolization strategies, strategies that typically hide tensions, emotions, and trauma (c).

FIGURE 6 Map experiments inspired by varying mapping visually translated to stories of human trafficking. Each experiment includes an aggregated map (left) and an individual’s map (right). Descriptions and reflection are provided for each experiment. (a) Image of the City, Kevin Lynch (Citation1960): Lynch identifies the “legibility” or experiential impact of city features through a series of cognitive sketch mapping activities with city dwellers and uses symbols that darken as experiences of locales coalesce. I applied this same logic to stories of human trafficking. The impact and intensity of given experiences are reflected in more saturated symbols. The size of Lynch’s maps (often fitting into the margins of his text) create an intimate and intensive viewing experiences. Further, the hand-drawn sketches humanize the storied experiences. (b) Napoleon’s March, Charles Minard (1812): Minard utilizes graduated flow lines and numeric labels that reflect the number of deaths along their advance and retreat. The dwindling line width is linked to a line graph documenting temperature, a visceral mapping technique linking deaths to falling temperatures. The base map illustrates minimal detail focusing the attention of the viewer. In my rendition, the width of the flow lines changes according to intensity of experience. Instead of temperature, the width of the flow line is linked with the price of life along the trafficking route. The flow line is labelled with experiences from the written story. (c) The Intricacies of These Turns and Windings, A Voyageur’s Map, Margaret Pearce (Citation2008): Pearce visually expresses place through a series of day frames documenting a French fur trader’s journey. Pearce devises experiential color palettes for each day frame combining hues in the physical/emotional landscape. The fur trader carries the viewer through the story using annotations separated by typeface from the mapmaker’s voice. I similarly translated trafficking stories day frames and experiential color palettes drawing on saturated red tones. My stories, however, were not linear and incomplete. As a result, story gaps are reflected as blank boxes.

The HRW stories arose as my dataset and included people, places, and events with some geographic locations but also emotions, tensions, and experiences, features that are typically left off of maps. Sketch mapping techniques opened space for me to map in/visible data layers outside of GIS software and created possibilities for expressive symbolization. The differences between my sketch maps and standard mapping techniques () were starkly apparent and demonstrated the need for expanded cartographic vocabularies. As such, I turned to cartographers, past and present, for map design inspiration, translating their varying techniques to HRW stories. I began with Kevin Lynch’s (Citation1960) Image of a City before moving to the work of Charles Minard, and Margaret Pearce, among others (2008) (). While iteratively mimicking each mapmaker’s aesthetic, I developed my technical cartographic toolkit. As part of this toolkit, I kept a journal to document the limits and opportunities within each design style as well as position as mapmaker/outsider, shifting my focus from product to intentional process. Most importantly and quite unexpectedly, I was building my own cartographic voice, a voice cognizant of my design decisions, by putting myself in conversation with other mapmakers.

Creative pedagogies directly inform my creative practice, embracing concepts over tools, trial and error, and iterative design paired with reflection. In my experimentation mimicking Kevin Lynch (Citation1960) (), for example, I relied on sketch mapping techniques to highlight places mentioned in the stories where traumatic events occurred. By opting out of GIS software, I retained the integrity of Lynch’s original concepts of “legibility” or memorable experiences of place. Additionally, creative pedagogy left room for tinkering despite the outcome as techniques were more or less effective across other contexts. In Framing the Days, Margaret Pearce (Citation2008) generated experiential color palettes, shading the landscape with expressive hues tied to an individual’s journal entries. Yet, her “day frames” (i.e., geographic containers documenting the travels of a single day) did not translate to the temporal gaps in Eritrean trafficking stories. As a result, missing or unaccounted for timestamps appear as ominous white boxes (). Finally, writing was essential to my iterative design approach. The combination of writing and mapping made space for critical reflection where I came to understand the limits and possibilities of each graphic mark. Writing/mapping became inseparable, generating a cartographic toolkit that I carry with me into my own classroom.

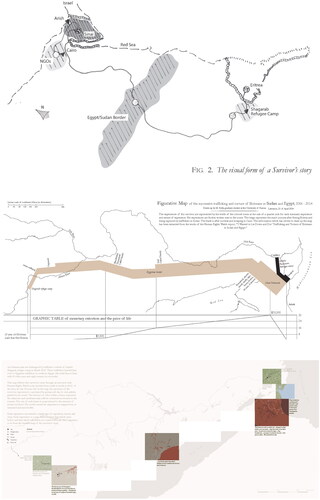

Creative Practice and Research

My creative practice and research merged as I explored mapping through the lens of feminist theory and borders literature, two pools of literature that re-envision traditional imaginaries of borders as static, solid black lines. Together, they offered new vocabularies and visual variables (i.e., the building blocks of visualization) to better reflect the dynamism and lived experience of all borders, not just the geopolitical. Geopolitical borders, for example, are not only dynamic, intermittently opening and closing over time, they are multi-dimensional consisting of points (checkpoints), lines (fences), and areas (borderlands or regions). Yet, map symbolization typically concretizes border imaginaries. Further, feminist theory expands conceptualizations of borders to include intimate and personal borders such as the body and home and grounds borders through embodied experiences. Default cartographic symbolization (e.g., solid black lines) underrepresent the possibilities for border symbols and alternative theoretical lenses generate a plethora of new possibilities (Kelly Citation2019).

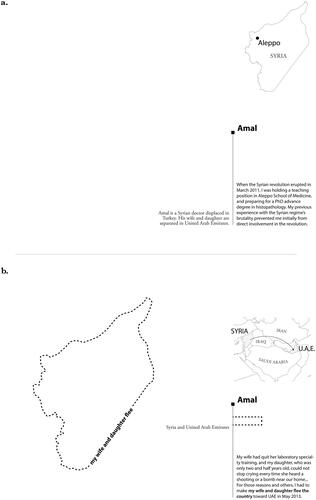

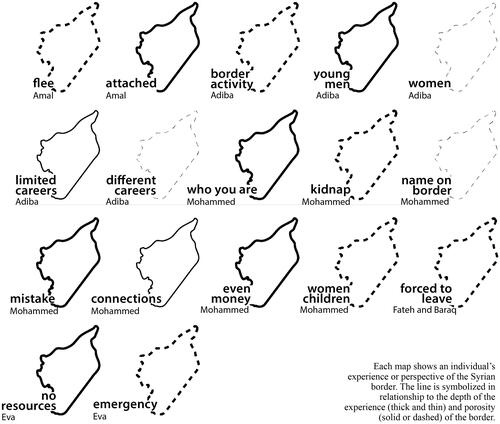

News maps depicting the Syrian refugee crisis, particularly refugee flows across borders, became my site for feminist intervention. Cartographic coverage of the ongoing crisis relies on aggregated mapping techniques (e.g., flow lines, shaded choropleths, proportional symbols that inflate according to numeric values) and homogeneous black borderlines that demarcate nation-states. Individualized maps similarly neglect personal stories and erase non-traditional personal borders. As a result, I posed the question: How can the cartographic portrayal of Syrian peoples’ border crossings be improved to better represent their experiences? To answer this question, I first analyzed the mapping techniques used in a series of news maps through a feminist theoretical lens. I then interviewed refugees and humanitarian workers listening to their border stories before developing an alternative mapping technique that was situated in feminist and border theory.

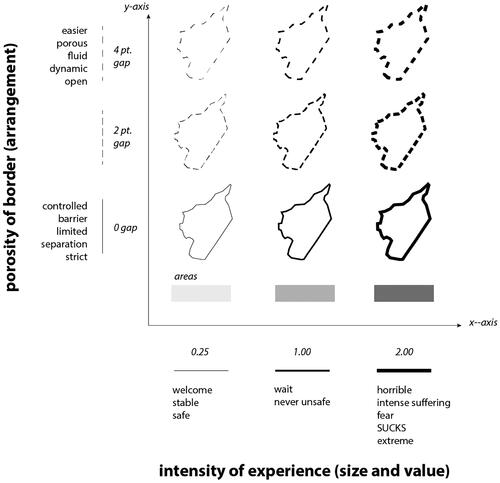

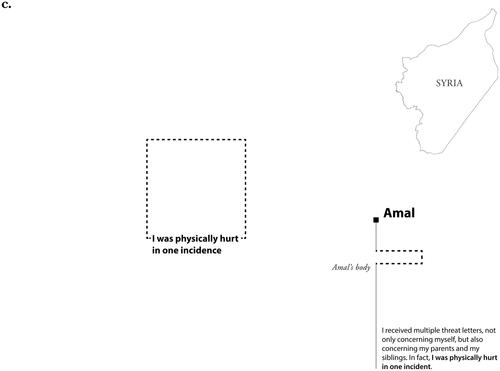

I approached this research project in both writing and mapping, including a manuscript and Borders: An Atlas of Syria Border Crossings (Kelly Citation2019). The atlas documents border stories at the individual and aggregate levels. To illustrate the possibilities for border symbolization, I grounded the atlas in four feminist concepts: embodied experience, intersectionality, transformation, and reflexivity (). For example, I encoded embodied experience within my line symbolization schema, border labels, and narrative text ( and ). I also included the body as a bordered site (). I developed a small multiple display to recognize commonality and difference across intersectional power structures (). The differential intersections of gender, age and socioeconomic status, among others, radically shifted the experiences of the same border. Throughout the atlas, I embraced all borders, including borders that are often made invisible and borders without a shapefile or precise location. I expanded the dimensionality of borders as linesto borderlands (i.e., polygons) and symbolized the porosity of borders on a dynamic continuum (). Unlike my more recent collaborative work (Bley et al. Citation2021), folks most impacted by the topic at hand, like refugees, did not partake in the mapping process, a research decision that indisputably steeped the resulting atlas within my position as mapmaker and outsider. To challenge perceptions of mapmakers as omnipotent and invisible forces, I made my position as mapmaker and outsider to these stories visible within the maps using two distinct typefaces and shared a reflexivity statement at the beginning of the atlas, common practice in artistic practice (e.g., artist statements) but less common in mapping ( and ).

FIGURE 7 A bivariate symbolization scheme for borders (lines) and borderlands (areas) that simultaneously encode porosity (y-axis) and the intensity of border experiences (x-axis) as continua. I then applied this schema to border experiences documented in interviews, including traditional geopolitical borders and non-traditional borders (see Kelly Citation2019 for details).

FIGURE 8. Three pages from Amal’s story that recounts his border experiences. (a) The opening page of Amal’s map series. The text in the lower right corner provides story context. The text on the left side of the line is written in a serif typeface, which reflects my voice as the outside mapmakers. The text on the right side of the line is written in a san serif typeface, which reflects Amal’s voice and excerpts from our interview. This technique transparently conveys my position as outsider and recenters voices within the story. (b) Amal’s first encounter with the Syrian border when his wife and daughter flee the country. The line is dashed recognizing their ability to cross the border and the line is thick recognizing the emotive toll of being separated from his family. The border line is label with his voice, an excerpted from our conversation. (c) Amal’s body depicted as a non-traditional border. The border’s label notes that Amal “was physical hurt in one incident” and as a result, the boundary is porous and thick having been violently transgressed. I did not have a precise geographic location for this incident. As such, I created space for border experience that cannot be located by giving them square border shapes.

FIGURE 9 A small multiple display of borders to illustrate commonality and difference across 17 border experiences.

This project reframed creative practice as feminist research. Writing and mapmaking were mutually constitutive and necessary components to addressing the question at hand. This approach blurred the artificial divide between theory and practice, requiring both. In addition to borders theory, feminist interventions like embodiment, intersectionality, transformation, and reflexivity provided new considerations for map design. In terms of symbolization, for example, line weights or the thickness of borderlines became imbued with embodied experience increasing in thickness as the intensity of an experience elevates (). Interdisciplinary theoretical lenses add news tools to my ever-evolving toolkit and mapping provided a creative outlet to explore and make theoretical concepts legible, generating alternative ways of understanding, challenging, and sharing theory. Finally, the combination of writing and mapping opened new visual modalities for reflexivity that move beyond written reflexivity statements (Kelly and Bosse Citation2022).

Collective Creative Practice

Most recently, I’ve turned to creative practice through collaborative design and workshops. To extend my work on border symbolization, I created an interactive poster for the North American Cartographic Information Society annual meeting that asked participants to sketch alternative borders symbols informed by Syrian border stories (). In Collectively Mapping Borders (Kelly Citation2016), mapmakers, mainly academics and mapakers attending the conference, stretched the cartographic vocabulary of border symbols beyond my imagination. I then mosaicked their border sketches to re-envision the cartographic portrayal of the Syrian border (). Taken altogether, the mosaic captures a wider expanse of design possibilities, curating a more expressive and pluralistic visualization of border experiences (Kelly Citation2016).

FIGURE 10 A collective sketch map of Syria mosaicked from alternative border symbols (see Kelly [Citation2016] for an expanded discussion). A collective sketch map of Syria mosaicked from alternative border symbols.

![FIGURE 10 A collective sketch map of Syria mosaicked from alternative border symbols (see Kelly [Citation2016] for an expanded discussion). A collective sketch map of Syria mosaicked from alternative border symbols.](/cms/asset/45eb45f7-c9d4-49fc-aaf6-2bd1a3772234/rgeo_a_2187313_f0010_b.jpg)

Inspired by collective creative practice and Black feminist thought applied to design (Costanza-Chock Citation2020), I developed a feminist mapping framework adapted from feminist principles in data science (D’Ignazio and Klein Citation2020) that could be applied across spatial data, map design, and mapping processes (Kelly Citationforthcoming). Classroom activities and workshops offered a venue for feminist experimentation in mapping. In feminist icon design workshop settings, I introduced mapmakers to the feminist framework and asked them to iteratively redesign individual map icons (e.g., bathroom, park, police) with the framework as a guiding lens, a task aimed to disrupt the supposed universality in icon sets. Participants combined sketching and writing to document and contextualize their designs and processes, producing an icon set with over a thousand alternative designs grounded in feminist thought (). The power of this icon set stems from its collective, contextualized curation and engagement with feminist questions.

FIGURE 11 Map icon sketches curated by workshop participants tasked with creating alternative iconography grounded in feminist principles (see Kelly Citation2021 for details).

Collective creative practice through border sketching and feminist icon design de-centered my interventions as a single mapmaker. Instead, they embraced the collective creative practice as a feminist method for presenting a multitude of worlds views to challenge default norms and power structures (see Costanza-Chock Citation2020 and Bosse Citation2021 for more on community-driven design processes). Workshops in particular became important sites for feminist mapping interventions because each workshop emphasized iterative and reflexive practice. As a feminist method, they also opened space for collaboration and creativity, disrupting institutionalized norms and envisioning design possibilities.

I’ve come to know creative practice through pedagogy, research, and collective workshops. As a student, I came to creative practice through coursework that de-centered technology and instead embraced expressive design. Now as a teacher, I similarly incorporate these lessons into my pedagogical strategies. Scaffolding creative practice into the classroom allows students to explore, play, and, at times, fail. Creative practice in research blurs theory and practice. It re-envisions research questions, alternative ways to explore geographic questions or spatial theory, and modes to share research. Creative practice in research requires new ways to understand and grapple with our positions in relation to power structures and our projects. Finally, creativity is enriched through collective practice and an emphasis on process. In sum, creative practice sparks new lines of feminist inquiry, new ways of thinking and visualizing, and new modes of collective engagement.

SOME NOTES ON ART PRACTICE AND GEOGRAPHY

By Nick Lally

In the fall of 2012, I lead groups of cyclists through Silicon Valley to visit important places in the history of personal computing and the internet (). The tour, which I called “A Spatial History of Computing,” is an artwork for the ZERO1 Biennial in San Jose. As we tour the valley, I tell stories that had happened in particular places—here’s the bar where the first email was transmitted, here’s the garage where a multinational behemoth claims to have started, here’s where the toxic remains of computer hardware manufacturing has poisoned the ground and water, here’s where the CIA studied the effects of LSD, and here’s where a group of hackers shared stolen paper tape copies of BASIC. Fragmented and partial, based on histories and myths, the project tells a few of the many intersecting stories that have produced (and continue to reproduce) the spatial imaginaries of Silicon Valley and computing. Like many of my art projects, the tour is an experiment and an experience—a selection of scattered notes rooted in place and spread unevenly across time, open to interpretation and speculation.

FIGURE 12 “A Spatial History of Computing,” bike tour for the ZERO1 Biennial, 2012. Photograph by Aaron Caley.

*-*-*-*-*-*

In his “Affectivist Manifesto,” art theorist Brian Holmes (Citation2009) generalizes a tendency of the previous century’s art:

In the twentieth century, art was judged with respect to the existing state of the medium. What mattered was the kind of rupture it made, the unexpected formal elements it brought into play, the way it displaced the conventions of the genre or the tradition. The prize at the end of the evaluative process was a different sense of what art could be, a new realm of possibility for the aesthetic. (13)

*-*-*-*-*-*

In Portland, Maine, Michael Huggins and I fill a small gallery with invasive knotweed harvested from surrounding areas (). We wire the plants so electrical signals flowing through the plants control an ambient soundscape. By touching the plants, visitors modulate the signals, changing the soundscape. Inspired by growing evidence that plants communicate to each other through root-fungus assemblages, we invite gallery goers to take part in the communicative networks of plants by touching and listening and connecting through low voltage electrical currents. While the plants’ rhizomes inside the gallery become one with the musical network we have built, outside, those same rhizomes slowly spread, choking out existing plants, breaking through the cement, and burrowing into the foundations of surrounding buildings.

*-*-*-*-*-*

Tara McPherson (McPherson Citation2018) writes about the creative and exploratory approach to making and theorizing that informed the Vectors lab at USC. The lab engaged with the materiality of the digital as a means to grapple with concepts and issues that spanned the humanities, arts, and computation:

Jane Bennett writes of the craftperson’s desire to see what a material can do (as opposed to the scientist’s desire to learn what a material is). This curiosity about the material, this desire to understand what things can do, operates in a different register from critique…. [T]here are other materials we might engage, other agencies to explore, that exist beyond the discursive realm, agencies that might move us toward new alliances and practices. (McPherson Citation2018, 21)

*-*-*-*-*-*

For a show on art-science collaborations, I work with Gautam Agarwal, a computational neuroscientist researching connections between animal behavior and neural activity (Agarwal et al. Citation2014). We spend months talking about art and brains while exploring different ways to translate and visualize his massive datasets. While in San Francisco, I videotape a group of flags and streamers flapping in the wind that remind me of our discussions. I use a slitscan technique to assemble a single image made up of thin, vertical slices of the video, each representing a discrete moment in time. In the image, Agarwal sees resonances with his data as the thin streamers look like neuronal spikes while the flags exhibit similar characteristics as an electrode array measuring brain waves (). We play on the similarities, producing a series of virtual 3D flags and streamers controlled by brainwaves that mimic the aesthetics of the videotaped flags. Of the project, we wrote, “we explored connections between electrical rhythms arising in the brain and other rhythms observed in the material world. Specifically, how does our understanding of these rhythms relate to the generative processes from which they arise, and to the ways in which we choose to depict them?”

FIGURE 14 “Fabricated Rhythm” print for installation with Gautam Agarwal (Citation2014). Image by author.

*-*-*-*-*-*

Bruce Braun and Sarah Whatmore (Citation2010) encourage us to think about the politics of the more-than-human, considering how “things of every imaginable kind—material objects, informed materials, bodies, machines, and even media ecologies—help constitute the common worlds that we share and the dense fabric of relations with others in and through which we live” (ix). Intervening in the world of things through explorations of materialities or the production of encounters are some of the spatial and political possibilities for art (Hawkins Citation2014). Similarly, Holmes continues his manifesto quoted above with a description of art in the twenty-first century, which he argues stands in relation to an existing state of society: “What we look for in art is a different way to live, a fresh chance at coexistence.”

*-*-*-*-*-*

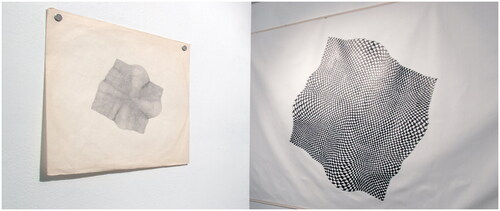

I begin drawing geometric patterns by hand, starting in the middle and working my way in circles to the edge of the paper (). Tiny imperfections multiply as the pattern grows, producing bigger imperfections that look like waveforms. I then write a computer program that draws similarly imperfect patterns. Those become the basis for new drawings, but also of large patterns that would take months to draw (if they were even possible). The code I have written is not a means to achieve some pre-determined goal, but rather, a means to collaborate with the machine and experiment with aesthetic possibilities. It seems that we are always collaborating with machines these days, but it is often limited by a rather narrow horizon of possibilities.

*-*-*-*-*-*

Writing a narrative is often an act of providing coherence to a fragmented and contingent series of events, making them congeal into a thematic journey with legible stops along the way. In tracing my path to geography, I sometimes narrate a path that leads from art to geography in a legible way. This is not a fiction, of course, but like my art projects, it is a creative reimagining of existing materials. The materials of my art practice include digital systems—the very things I theorize about in my work as a geographer. Art and geography, then, are not divergent interests or practices for me, but rather, mutually reinforcing ways of intervening in and poking, sometimes experimentally, at the edges of various computational systems.

CONCLUSION

In the above vignettes, each of us, in turn, has reflected on how our art practices are intertwined with our research practices as geographers. In our collective discussions, we identified three thread lines that run through our work described above: experimentation and play, tools, and sites and time. Individually, we offer our vignettes to capture and document the beginnings of our practices and their permutations within our larger body of work. Collectively, our vignettes illuminate a gallery of possibilities or alternative interventions for art and experimentation in geographic scholarship and pedagogy. By sharing our practices collectively, we hope to generate conversation that simultaneously recognizes connectivity and difference among such practices, building a community toolkit for art and experimentation.

Writing this piece has also led us to reflect on our pedagogical practices, including the possibilities and challenges of bringing this kind of work into the classroom. Efforts to introduce such practices can be difficult when they disrupt students’ expectations. As Anne Kelly Knowles (Citation2000) observes of her creative efforts to teach mapping without a GIS, “The first step in developing new habits was to soften students’ inhibitions about “being artists” and encourage them to experiment, to play with depicting historical ideas graphically” (27). But we believe that making room for experimentation and play, which often involves nurturing collaborations and making room for failure, can be transformative for students, just as that space has been transformative for us. In those moments, we see room for creative scholarship that expands the possibilities for geographical engagement and inquiry.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to Philip Nicholson for organizing the 2019 AAG paper session on “Creative Geovisualisation” that sparked our initial conversations and the beginnings of this article. Special thanks to Deborah Dixon for moderating our AAG session and for encouraging a collective reflection on art and geographical practice. We thank Tim Cresswell and Jennifer Cassidento for managing the editorial process and the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable input that encouraged and strengthened our ruminations. Perhaps most importantly, we thank everyone who has informed our art practices in- and outside of the academy. This includes but is not limited to our collaborators, mentors, teachers, and students. We also acknowledge the heaviness and complexity of the current moment that has placed extenuating pressure on each of us (like many others) throughout the writing and publishing process. While we each carry privilege in differential ways, we continue to recognize the increased difficulty and precarity of creative geographical practice in contemporary academic spaces.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Meghan Kelly

MEGHAN KELLY is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Geography at Durham University, Durham, DH1 3LE, UK. E-mail: [email protected]. Her research interests include feminist and transformative mapping, feminist digital geographies, and digital storytelling.

Nick Lally

NICK LALLY is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40506, USA. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests include speculative cartography, critical computation, and technologies of policing.

Philip J. Nicholson

PHILIP J. NICHOLSON is a Research Data Analyst in the Institute of Education at University College London, London, WC1H 0AL, UK. Email: [email protected]. His research interests include creativity and play with geospatial media as well as the power relations within which geospatial work takes place.

Notes

1 There are, of course, exceptions to be found within the discipline, which serve to inform the software tools I build (2022).

REFERENCES

- Agarwal, G., I. H. Stevenson, A. Berenyi, K. Mizuseki, G. Buzsáki, and F. T. Sommer. 2014. Spatially distributed local fields in the hippocampus encode rat position. Science 344 (6184):626–30. doi:10.1126/science.1250444.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Benjamin, R. 2019. Race after technology: Abolitionist tools for the New Jim Code. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Bley, K., K. Caldwell, M. Kelly, J. Loyd, R. E. Roth, T. M. Anderson, A. Bonds, J. Plevin, D. Madison, C. Spencer, et al. 2021. A design challenge for transforming justice. GeoHumanities 8 (1):344–65. doi:10.1080/2373566X.2021.1986100.

- Bosse, A. 2021. Collaborative cartography. In The geographic information science & technology body of knowledge, ed. John P. Wilson, 3rd quarter 2021 ed. Chesapeake, VA: UCGIS. doi:10.22224/gistbok/2021.3.2.

- Bourriaud, N. 2002. Relational aesthetics. Les Presses du réel.

- Braun, B., and S. Whatmore. 2010. Political matter: Technoscience, democracy, and public life. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Costanza-Chock, S. 2020. Design justice: Community-led practices to build the worlds we need. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Curtis, A., J. Tyner, J. Ajayakumar, S. Kimsroy, and K.-C. Ly. 2019. Adding spatial context to the April 17, 1975 evacuation of Phnom Penh: How spatial video geonarratives can geographically enrich genocide testimony. GeoHumanities 5 (2):386–404. doi:10.1080/2373566X.2019.1624186.

- D’Ignazio, C., and L. F. Klein. 2020. Data feminism. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Drucker, J. 2009. SpecLab: Digital aesthetics and projects in speculative computing. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Drucker, J. 2020. Visualization and interpretation: Humanistic approaches to display. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

- Elwood, S. 2006. Critical issues in participatory GIS: Deconstructions, reconstructions, and new research directions. Transactions in GIS 10 (5):693–708. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9671.2006.01023.x.

- Elwood, S., and M. Wilson. 2017. Critical GIS pedagogies beyond “Week 10: Ethics.” International Journal of Geographical Information Science 31 (10):2098–116. doi:10.1080/13658816.2017.1334892.

- Haklay, M. 2013. Citizen science and volunteered geographic information: Overview and typology of participation. In Crowdsourcing geographic knowledge: Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) in theory and practice, ed. D. Sui, S. Elwood, and M. Goodchild. New York, NY: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-4587-2.

- Hawkins, H. 2011. Dialogues and doings: Sketching the relationships between geography and art. Geography Compass 5 (7):464–78. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2011.00429.x.

- Hawkins, H. 2013. Geography and art. An expanding field: Site, the body and practice. Progress in Human Geography 37 (1):52–71. doi:10.1177/0309132512442865.

- Hawkins, H. 2014. For creative geographies: Geography, visual arts and the making of worlds. New York; NY: Routledge.

- Hawkins, H. 2015. Creative geographic methods: Knowing, representing, intervening. On composing place and page. Cultural Geographies 22 (2):247–68. doi:10.1177/1474474015569995.

- Holmes, B. 2009. Escape the overcode: Activist art in the control society. Eindhoven, Netherlands: Van Abbemuseum.

- Jefferson, B. J. 2017. Digitize and punish: Computerized crime mapping and racialized carceral power in Chicago. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 35 (5):775–96. doi:10.1177/0263775817697703.

- Katz, C. 1994. Playing the field: Questions of feminist fieldwork. The Professional Geographer 46 (1):67–72. doi:10.1111/j.0033-0124.1994.00067.x.

- Kelly, M. 2016. Collectively mapping borders. Cartographic Perspectives 84:31–8. doi:10.14714/CP84.1363.

- Kelly, M. 2019. Mapping Syrian Refugee border crossings: A feminist approach. Cartographic Perspectives 93:34–64. doi:10.14714/CP93.1406.

- Kelly, M. 2021. Mapping bodies, designing feminist icons. GeoHumanities 7 (2):529–57. doi:10.1080/2373566X.2021.1883455.

- Kelly, M. Forthcoming. Feminist geography and geospatial technology. In The Routledge handbook of geospatial technologies and society, ed. A. Kent and D. Specht. Boca Raton, FL: Routledge.

- Kelly, M., and A. Bosse. 2022. Pressing pause, “doing” feminist mapping. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 21 (4):399–415.

- Kitchin, R., J. Gleeson, and M. Dodge. 2013. Unfolding mapping practices: A new epistemology for cartography. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 38 (3):480–96. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2012.00540.x.

- Knowles, A. K. 2000. A case for teaching geographic visualization without GIS. Cartographic Perspectives 36:23–37. doi:10.14714/CP36.823.

- Lally, N. 2022a. Sculpting, cutting, expanding, and contracting the map. Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization 57 (1):1–10. doi:10.3138/cart-2021-0013.

- Lally, N. 2022b. What can GIS do? ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 21 (4):337–45.

- Lynch, K. 1960. Image of a city. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Maharawal, M. M., and E. McElroy. 2018. The anti-eviction mapping project: Counter mapping and oral history toward bay area housing justice. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108 (2):380–9. doi:10.1080/24694452.2017.1365583.

- McPherson, T. 2018. Feminist in a software lab: Difference + design. Cambridge, MA; Harvard University Press.

- Mogel, L. 2011. Disorientation guides: Cartography as artistic medium. In Geohumanities: Art, history, text at the edge of place, ed. M. Dear, J. Ketchum, S. Luria, and D. Richardson, 187–95. London and New York: Routledge.

- Nicholson, P. J., D. Dixon, D. Pullanikkatil, B. Moyo, H. Long, and B. Barrett. 2019. Malawi stories: Mapping an art-science collaborative process. Journal of Maps 15 (3):39–47. doi:10.1080/17445647.2019.1582440.

- Nicholson, P. J. 2022. Technologies, aesthetics and affordances. In Routledge handbook of geospatial technologies and society, ed. D. Specht and A. Kent. Boca Raton, FL: Routledge.

- Paglen, T. 2008. Experimental geography: From cultural production to the production of space. In Experimental geography: Radical approaches to landscape, cartography, and urbanism, ed. N. Thompson, 27–33. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House.

- Pearce, M. W. 2008. Framing the days: Place and narrative in cartography. Cartography and Geographic Information Science 35 (1):17–32. doi:10.1559/152304008783475661.

- Rose-Redwood, R., N. B. Barnd, A. H. Lucchesi, S. Dias, and W. Patrick. 2020. Decolonizing the map: Recentering Indigenous mappings. Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization 55 (3):151–62. doi:10.3138/cart.53.3.intro.

- Simondon, G. 2016. On the mode of existence of technical objects. Minneapolis, MN: Univocal Pub.

- Simpson, G. 2014. ‘I wanted to lie down and die,’ Trafficking and torture of Eritreans in Sudan and Egypt. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/report/2014/02/11/i-wanted-lie-down-and-die/trafficking-and-torture-eritreans-sudan-and-egypt.

- Stewart, K. 2007. Ordinary affects. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Sui, D. Z. 2004. GIS, cartography, and the “Third Culture”: Geographic imaginations in the computer age. The Professional Geographer 56 (1):62–72. doi:10.1111/j.0033-0124.2004.05601008.x.