ABSTRACT

Playing Out began as a simple, direct action by two mothers on their own street in Bristol, UK. Over eight years, it has grown into a UK-wide movement driven by parent and resident activists and involving over 800 street communities. This case study sets out the background and context for this modern street play movement, provides evidence of its impact for children and communities and makes an argument for the restoration of street play as a normal part of urban childhood.

Introduction

Back in 2009, two mothers in Bristol, UK, were concerned about their children’s lack of freedom to play out. Compared to their own urban and suburban childhoods in the 1970s, their children were spending far more time indoors, inactive and isolated. In one generation, the physical and social environment had changed to the extent that it no longer felt safe or acceptable to let their children simply ‘play out’ on the street or near home. One of these mothers was me; the other was my neighbour Amy Rose. Unwilling to accept the status quo and the implications for our children’s health and well-being – and their rights as citizens – we decided to try and change things, starting with our own street.

Unaware of a historical precedent (Cowman Citation2017), our idea was to create a temporary ‘play street’ for a few hours one day after school. With our neighbours, we would formally close the road to through traffic, giving over the space for children to play freely. The aim was to provide both an immediate solution and a catalyst towards children regaining the freedom to play out every day. We called the model ‘Playing Out’.

The problem

Our own parental concerns reflected a widespread modern reality. Children’s time spent outdoors (Cleland Citation2010), outdoor play (Play England Citation2010), ‘roaming range’ and independent mobility (Shaw et al. Citation2013) have all massively reduced over a few decades. Children’s lack of freedom in the UK has been likened in the mainstream media to that of battery-reared animals and high-security prisoners (see e.g. Independent Citation2004, Guardian Citation2016).

We also know that children’s physical activity levels – linked to independent travel and time spent outdoors (Page Citation2009, Cooper Citation2010) – are alarmingly low in the UK. Despite heavy government investment, replacement activities such as organised sports have not compensated and only around one in five children gets the minimum recommended 1 hour a day of moderate-to-vigourous physical activity (Health Survey for England Citation2015). Alongside rising obesity levels, the decline in children’s fitness over one generation has been so rapid that it has been claimed that the least fit child in a class of 30 twenty years ago would be one of the fittest today (Sandercock Citation2018).

In any case, activities aimed purely at getting children more active do not provide the opportunity for free, independent play that children need, both for its social and developmental benefits and for its own sake. Some may say that outdoor play can still happen in private gardens, parks and playgrounds – and that these designated spaces are sufficient to meet children’s needs – but this view is both erroneous and dangerous. Most children living in UK cities have either no garden or one so small as to make ‘big’ active play impossible. Children without access to a garden – generally those from less well-off backgrounds – are far more likely to become overweight or obese (Schalkwijk et al. Citation2018) and even where private gardens are a reasonable size, they cannot afford a comparable experience to playing out in a public space with other children.

Parks and playgrounds offer the possibility of more sociable and ‘big’ play. They may even have the added benefit of natural, exciting or risky features. If you want to climb a tree, skate a half-pipe or play a proper game of football, you probably need to go to a park. But even the best, safest, greenest parks do not compensate children for the loss of safe, accessible space literally on their own doorstep. One impact of the reduction in children’s independence is that, under a certain age (in my neighbourhood, the norm is probably 10- or 11-years old), they do not have the ‘licence’ to get to these places alone and are therefore completely dependent on parents taking them there. As a result, the time most children spend in these spaces is far from sufficient to meet their basic need for active play.

But even if a parent could somehow find the time to take their child to the park every day, would this be enough, or would they still be missing something important?

History and importance of street play

There is a long tradition of children informally playing out in the streets and shared spaces near to their homes, and this is still the case in many towns and cities worldwide (). It is natural and easy for children to play close to their front door – within parental sight or shouting distance. Indeed, until very recently, ‘it was an accepted use of residential streets that children could play in them’ (Tranter Citation1996, p. 91–2).

Cowman (Citation2017) narrates how the rise of the motorcar in Britain from the 1920s onwards began to push children off the streets that had, until then, been a social space and extension of the domestic sphere. Children started to be knocked down and killed in shocking numbers (Moran, quoted in Cowman Citation2017), leading to a polarised reaction: get children off the streets, or protect their right to play out. Pertinently, in the light of the current parent-led Playing Out movement, Cowman reveals that the resulting Play Streets (c.1930–70) were not just a bureaucratic top-down intervention but also a fiercely radical protecting of domestic space campaigned for by working-class mothers (). However, it could be argued that these designated Play Streets still served to ‘ghettoise’ children’s play without challenging the ever-increasing dominance of motorised traffic. Ultimately, cars won the battle for space on residential streets and Play Streets fell out of use.

Despite this, informal ‘playing out’ persisted, and up until the 1970s () and 1980s was still very much the norm in UK towns and cities (Department of the Environment Citation1973). Most adults over the age of 40 say they played out regularly as children (Playday Citation2007), perhaps migrating to a nearby quiet street or cul-de-sac. Children and cars found a reasonable balance and most children still walked to school independently (Hillman Citation1990). Many have written of the importance of this type of informal street play and of the importance of streets as a space for play (e.g. Jacobs Citation1961, Ward Citation1978). In her M.Sc. dissertation, Emma Griffin (Citation2015) neatly summarises the literature:

In these accounts the street is celebrated as an important and irreplaceable space for children. This is ‘un-programmed space’ (Lynch Citation1977) for imaginative and creative play and ‘random and spontaneous amusement’ (Percy-Smith Citation2002, p. 67). The street is also on the doorstep and acts as a ‘crucial mediator between the home and the outside world’ (Appleyard Citation1981, p. 9). It provides space for both independence and supervision of children (Hart Citation2002). As such, the street is a learning ground (Lynch Citation1977, Hillman Citation2006) or ‘site of passage’ from the restrictions of ‘childhood roots towards the independence of adulthood’. (Matthews Citation2003, p. 101)

Just ask any adult who grew up with this as a large part of their daily life and they will light up at the memory, listing a whole range of positive, often intangible social and personal outcomes: learning to deal with people and situations independently; managing risk; having a sense of ‘belonging’ in your neighbourhood; the pure enjoyment of freedom and self-determination. However, as Hillman (Citation2006, p. 63) points out, ‘The benefits of that freedom – being able to go out unaccompanied – appear to have been largely forgotten’.

So what has gone wrong?

Paul Tranter’s 1996 paper ‘Reclaiming the Residential Street as Play Space’ is an excellent summary of how and why street play has declined over one generation, and the impact of this on children’s lives.

In a nutshell, since 1980, car ownership and traffic volume have both more than doubled (DfT Citation2013) and residential streets have become so physically and psychologically dominated by cars that people – and children in particular – have been pushed out of the space. The negative social impact of heavy traffic in residential streets has been clearly shown (Appleyard Citation1969, Hart and Parkhurst Citation2011) and it can be assumed that this impact is even greater for children, who may not even be able to cross their own road to call on a friend. We know that it is real traffic danger, not imagined ‘stranger danger’ that is parents’ main concern (Playday Citation2007, Shaw et al, Citation2013), contrary to what the media would have us believe.

Screens and indoor technology are often blamed as the cause of children’s inactivity – the implication being that lazy modern children choose to play indoors on their X-box instead of playing outside. But the reality – demonstrated clearly by the playing out model and by ‘snow days’ (Gill Citation2017b) – is that when children have the opportunity to play out with others in a safe space near home, they generally prefer to, whatever the weather! ()

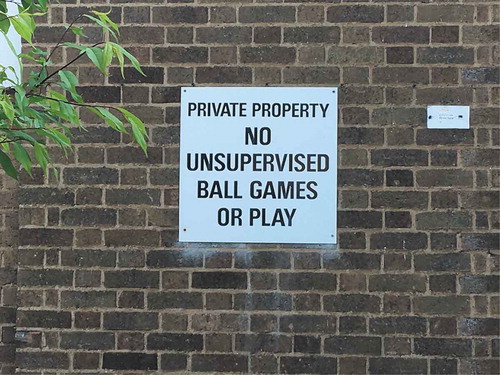

By unthinkingly creating child-unfriendly streets ( and ), a vicious circle has been set in motion: the less children are seen playing out, the less playing out is seen as a feasible or attractive idea and ‘eventually, residential streets are perceived as being deserted, lonely and hence dangerous places for children [reinforcing] drivers’ perceptions that the street is their territory’ (Tranter and Doyle Citation1996). All this has led to a general acceptance that children no longer belong in the streets (). Mother, academic and ‘playing out’ organiser Emma Griffin (Citation2015) describes a feeling undoubtably shared by many parents today:

I was frustrated by how closely supervised children needed to be in public spaces. I was tired of my fear of the road, of clutching my children at crossings and running after them down pavements. I was also tired of the judgment from others if I ever did relax my vigil. I have been advised, unnecessarily and on more than one occasion, to literally tie my children to me to keep them safe.

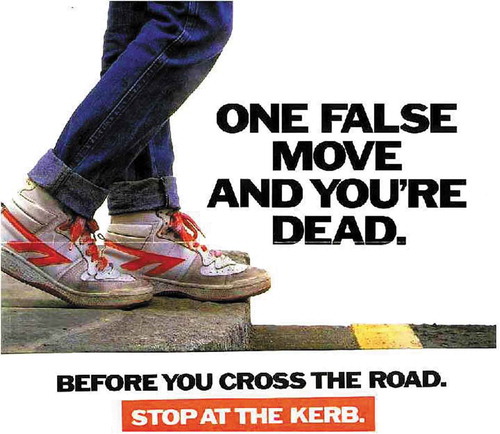

Arguably, the situation has been further exacerbated by the prevalent road safety approach, which instead of reducing danger at source has attempted to keep children away from roads (Tight et al. Citation1998) (). In the UK, the number of children killed by cars, whilst walking or playing in the streets, has fallen steadily from a horrific peak of 396 deaths in 1983. Those responsible for road safety policy claim that ‘this change is extremely positive’ (CAPT Citation2013), but is it really? What is the real reason for this reduction and what has the cost been to children’s health and freedom? Hillman et al. (Citation1990)and Hillman (Citation2006), amongst others, have argued that roads are in fact becoming more dangerous and the reduction in casualties is purely a result of children deferring to motorised traffic and staying away from streets altogether.

Children’s independent mobility has been curtailed still further since the 1980s, with traffic danger being cited as the dominant cause (Shaw et al. Citation2013). Unbelievably, there still does not seem to be any objective measure of traffic/road danger. In a classic example of circular reasoning, accident statistics are commonly used to assess this, so a road that is dangerous enough to deter pedestrians – particuarly children – from going anywhere near it might be classified as ‘very safe’ (see Adams Citation1993).

Over 20 years ago Tranter (Citation1996, p. 91–2) declared, ‘In most cities now, streets are seen as barriers for children, rather than as a useful resource for play’. This is now even more true, and the full impact of this loss – on children’s health, well-being, happiness, development, socialisation, sense of place and belonging, resilience and independence – is yet to be formally evaluated (an urgent research gap to fill) but seems likely to be significant.

The ‘playing out’ model

The ‘playing out’ or Temporary Play Street model is an attempt to turn the situation around and reclaim residential streets as communal, playable spaces. It is an immediate, temporary and ‘do-able’ solution, giving children the opportunity to play out safely on a regular basis (Ferguson and Page Citation2015). Through building community cohesion, raising awareness and making children more visible, it is also a catalyst for wider cultural change. In the short term, it provides set times when streets are transformed and children’s right to play takes precedence over cars. In the longer term, it begins to re-negotiate a more egalitarian sense of shared ownership and use of residential streets.

Key features of the ‘playing out’ model:

Resident-led

Low-cost

Using existing space

Regular and sustainable

Safe and legal

Inclusive

Free, child-le play

Catalyst for change.

From the perspective of parents, it is a simple action they can take themselves to address a pressing concern. For policy-makers, it is a cheap, easy and sustainable way of getting children more physically active whilst also bringing communities together and addressing social isolation.

Helen Jarvis (Citation2018) has recently written about the Playing Out movement in the context of ‘Do it Together’, bottom-up urban development, which fits well with how we see it ourselves: the radical, neighbour-led process being as important as the end result.

First steps

The first ‘playing out’ session on my street in 2009 was somewhat of an experiment. My artist neighbour Amy Rose had been making images of the street reimagined, including barracading the road so children could play out. Together, we decided to make this vision a reality in the short term, using the council’s existing road closure procedure.

With support from neighbours, we applied to close the road for a few hours after school one day, to reinforce the idea that playing out was – or should be – a normal, everyday activity, not a special event. We had organised street parties before; this was going to be different. There would be no food, music or games – just a safe, empty space and permission to play freely. Residents could keep their cars parked on the street and drive in or out if necessary, ‘stewarded’ by a volunteer neighbour (). We wanted to show that just a small change – removing fast traffic – could transform the street from an underused resource to a useable space alive with activity.

This first session was a lightbulb moment. Given the opportunity to play safely outside their own front door, with no ‘activities’ provided, children came out in surprising numbers (you don’t know who lives on your street when everyone is stuck indoors!) and played more actively and joyfully than we had thought possible (–). Adults of all ages also came out to socialise and reminisce about their own childhood. We knew – and others agreed – this was an idea worth pursuing.

Establishing the model

The following summer, we ran a pilot on six local streets, led by residents with our support (Playing Out Citation2010a). The success of this, and the sheer sight of children playing out freely and actively, prompted local politicians to back the idea. We helped the council to develop a trial ‘Temporary Play Street Order’ (TPSO), using existing legislation to allow residents to apply for a whole year’s worth of regular (up to weekly) closures for play, as opposed to just three one-off events per year.

There were some teething troubles during the pilot year – one street was refused permission as a neighbour objected on the grounds they ‘didn’t like the idea’ of children playing in the street. However, 16 streets went ahead with regular sessions and the response from residents was overwhelmingly positive (Playing Out Citation2012). The council decided to make the policy permanent and soon other UK councils started to follow suit, using a variety of legal routes (Layard Citation2013).

In 2011, in response to growing interest from around the country, we set up Playing Out as a not-for-profit Community Interest Company to promote and support the idea and grow a grassroots movement for change across the UK.

Barriers and enablers

Over the past eight years, through supporting this model in many different settings across the UK, we have learned a lot about what is needed to make it work, for residents and authorities.

For residents, the main enabling factors are: support from neighbours; a simple, accessible council policy; clear guidance; peer-support and a basic road-closure kit. Some, especially those living in areas of high deprivation (Gill Citation2017a), may also need more hands-on help through the process or help with costs such as printing letters.

For local councils, barriers include a lack of clarity about which legislative basis to use, administrative costs (again linked to the legislation), and concerns about risk and litigation. However, many are willing to take on these small costs and risks for the sake of enabling an effective, community-building solution to a pressing public health problem, and there is a growing peer-support network of active local authority officers who can advise and reassure any nervous colleagues.

Opposition to street play

A small minority of people are firmly against either the ‘playing out’ model or children playing out generally, with the same objections and concerns coming up repeatedly (Playing Out Citation2010b), seemingly based in an underlying belief that ‘roads are for cars’ and no place for children. Some are explicitly self-interested (‘My car might get scratched’), others apparently more altruistic (‘I’m worried a child will get run over’) and the majority simply not ‘getting it’ (“Why can’t they just play in the park’?). Online comments in response to media coverage about Playing Out have been particularly revealing of the breadth of current attitudes about children’s right to public space (see BBC World Hacks Citation2017).

These attitudes are themselves another barrier to children playing out, so are important to understand and challenge. Some councils have taken the decision to discount this type of response to play streets, only considering so-called ‘material’ objections from residents. Occasionally, initially opposed residents have completely changed their attitude after seeing the positive effects of playing out on their street, with some even volunteering to steward (Playing Out Citation2015).

A growing movement

To date (September 2018), with support from Playing Out and local organistions, thousands of adults in over 800 street communities across the UK have self-organised regular playing out sessions, directly benefitting an estimated 24,000 children. 57 UK councils have so far adopted a ‘Temporary Play Street’ policy enabling residents to apply for regular road closures. In Bristol, our home patch, we have supported over 170 streets to play out all over the city, alongside project work to highlight and tackle particular barriers to playing out in tower block estates and areas of high deprivation.

The strength of the model is that it is resident-led, and the same is true for the wider movement. Parents especially are strongly driven to change things for children and are willing to take action in their streets and communities. Some are taking on a bigger role as local ‘activators’, promoting the idea across their city or county, working with their councils to get the right policy and support in place, and providing peer-support to other streets.

Emma Griffin (Citation2015) identifies the ‘wide appeal’ of the idea, hitting many different motivators for both parents and policy-makers, as key to its success and rapid growth.

Gathering evidence for the impact of the ‘playing out’ model

Over the past 8 years, we have seen first-hand the many benefits of the model for children, parents and whole communities. Now there is evidence to back this up. Independent research and our own evaluation confirm the four main areas of impact:

(1) Improving children’s health and well-being

(2) Improving community cohesion

(3) Increasing ‘active citizenship’

(4) Bringing about longer-term culture change

(1) Improving children’s health and well-being

New research by the University of Bristol has shown that children are three to five times more active during playing out sessions than they would be on a ‘normal’ day after school (Page et al. Citation2017). Using GPS and accelerometers, it was found that children were outdoors for a large proportion (>70%) of the time the streets were closed and spent on average 16 min per hour in moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA). Whilst this might not sound earth-shattering, the report concludes that, ‘This can make a meaningful contribution to whether children are likely to meet the 60 min MVPA daily target set out in the UK physical activity guidelines’. It also found that ‘playing out’ was sustainable, scalable and applicable across a broad range of socio-economic situations. An earlier study of council-led play streets in Ghent found similar results (D’Haese et al. Citation2015).

Significantly, both studies also note the limited success of traditional, behaviour-centric physical activity interventions, which involve encouraging children to take more exercise (see e.g. Peymane et al. Citation2018). By contrast, play streets target ‘the neighborhood environment (e.g. creating a car-free play place) and the social environment (e.g. increased social interaction between children playing in the street)’ (D’Haese), fitting better with more recent thinking around ‘ecological’ models of health behavior, which emphasize the interaction between the individual and social/environmental factors (Sallis Citation2008). Common sense says that, especially when it comes to children, whose natural state is to be moving, they do not need to be told to be active, they just need the opportunity to be – but as Hillman (Citation2006, p. 63) points out, ‘their choices are very much constrained by influential factors way beyond their control’.

The vast majority of respondants to our own survey of ‘playing out’ streets also said that children had learned or improved physical and social skills during sessions, including riding a bike (80%) and interacting with other children (88%). But, significant as these health and developmental outcomes are, we must not lose sight of the main motivation and benefit for children – simply the chance for free, joyful play, with its intrinsic value in making their lives better and happier (Lester and Russell Citation2008). As Adrian Voce says, ‘More children playing outside, more often, in the common spaces of their local neighbourhoods, is an end in itself’ (Voce Citation2015, p. 159).

Beyond the direct impact for the children and adults participating in street play sessions, the impact of this parent-led movement is likely to be far wider, inspiring more informal play in streets, estates and shared spaces.

(2) Stronger communities; a sense of belonging

Several anecdotal reports have highlighted the increased community cohesion resulting from both the organisation process on a street and the ‘playing out’ sessions themselves. The University of Bristol study found both a strengthening of existing connections and building new connections between neighbours (Page et al. Citation2017) the vast majority of respondants to our own survey (Playing Out Citation2017) said they know more neighbours (91%) and feel more sense of belonging (84%) as a result of playing out sessions: ‘the street feels different…friendlier, safer, more known, more lively’; ‘playing out has made my street feel like home’.

(3) Active citizenship

Organising or helping at a playing out session is a form of community activism in itself and around 12,000 residents have taken this action in their street across the UK. Many organisers have also reported an increased sense of citizenship in their neighbourhood. Crucially, at a time when – economically, politically, socially and practically – community-led action is becoming ever more essential, over a third of survey respondents said playing out has led to them being involved in other community activities. One simply said, ‘I feel more empowered to make positive change in my community and in the street where I live’.

(4) Long-term culture change

One of the most encouraging outcomes of the model is the lasting effect it can have on the culture of a street, with children starting to feeling it’s normal to be out playing on other days. According to one organiser, ‘Over time, the playing out sessions have led to more of a “calling for you” culture as more kids know each other and they sometimes now play football together in the evenings’. Just last week I walked past another local street that has been doing regular playing out sessions for a few years. There were around ten children of all ages out playing in the middle of the road, with no adults in sight. It felt like a real moment of hope.

The wider impact on attitudes and culture is hard to measure, but there are signs of a ‘ripple effect’ from the streets that are playing out to surrounding streets. The movement as a whole, via media and social media, is at least raising awareness and increasing discussion about the issues. A recent BBC News video about Playing Out has had over 10 million views and and an initial analysis of the comments suggests widespread support for children’s right to play out.

International links

This low-key, low-cost resident-led street play model is increasingly recognised by cities internationally as a modern solution for children’s well-being and for community cohesion. Playing Out has been approached by non-profits and community activists from the USA, Australia, Canada, France, Spain, Portugal, Norway and Ireland with requests to translate our model and materials into different cultural and linguistic contexts. In Germany, residents on one Berlin street are campaigning for a change in national and local legislation to support the temporary play street model.

Looking to the future

We are not looking for this model to continue indefinitely – it’s a stop-gap giving children a semblance of ‘real’ (independent and every day) playing out. But, crucially, it is also helping to build the conditions needed for playing out to become normal again: increased neighbourliness, safer streets, more confident parents, greater awareness of and legitimacy for children being in that space. By making children and their need for play more visible, it may also help lead to changes in policy and planning, as well as increasing the societal support that children need to feel safe and welcome in public space.

Despite some intransigence at the national policy level, there are encouraging signs of a culture-shift in thinking about cities and children. In particular, we are seeing a growing recognition (particularly at local authority level, as shown by the level of interest and support for the ‘playing out’ model) that physical spaces – streets, estates, neighbourhoods – where children live need to lend themselves far better to enabling everyday physical activity, independent mobility and play. There is also growing evidence of a strong correlation between the quality and safety of children’s immediate local environment (e.g. their own street) and their ability to play out (Blinkert and Wheeler Citation2015, Foreman Citation2017).

This journal edition itself is part of that culture shift, along with recent publications aimed at policy-makers and city leaders internationally, such as Arup’s Citation2017 publication on designing more child-friendly cities and a recent report – entitled ‘Playing Out’ – from the Children’s Commission (Children’s Commissioner for England Citation2018).

For as long as there is interest and resourcing, Playing Out will continue to support the growing grassroots street play movement and advocate for children’s right to play out, working with other organisations both in the UK and internationally to bring about lasting change.

To be part of this change, or link up with the movement as an individual, organisation, academic or decision-maker, please visit www.playingout.net and get in touch.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alice Ferguson

Alice Ferguson: In 2009, Alice and her neighbour, Amy Rose, temporarily transformed their street into a safe ‘shared space’ where children could play freely outside their front door, simply by closing the road to through-traffic for a short time. This model was intended as a stop-gap and a catalyst for change. Alice is now Co-Director of Playing Out CIC, set up to support a growing parent-led movement to restore children's freedom to play out where they live. Twitter: @aliceplayingout

References

- Adams, J., 1993. Risk compensation and the problem of measuring children’s independent mobility and safety on the roads. Ch. 7. In: Children, transport and the quality of life. London: Policy Studies Institute.

- Appleyard, D., 1969. The environmental quality of city streets: the residents’ viewpoint. Journal of the american planning association, 35, 84–101.

- Appleyard, D., 1981. Livable streets. Berkeley, Cal: University of California Press.

- Arup, 2017. Cities alive: designing for urban childhoods. London: Arup.

- BBC, 2017. ‘World hacks’ film and comments. Available from: https://www.facebook.com/bbcnews/videos/10155322030712217/

- Blinkert, B. and Weaver, E., 2015. Residential environment and types of childhood. Humanities and social sciences, 3 (4), 258–267. doi:10.11648/j.hss.20150304.16

- CAPT, 2013 Making the link, Available from http://www.makingthelink.net/child-deaths-road-traffic-accidents

- Children’s Commissioner for England, 2018. Playing out: a children’s commissioner report on the importance to children of play and physical activity. Available from: https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Play-final-report.pdf

- Cleland, V., et al., 2010. Predictors of time spent outdoors among children: 5-year longitudinal findings. Journal of epidemiology & community health, 64, 400–406. doi:10.1136/jech.2009.087460

- Cooper, A.R., et al., 2010. Patterns of GPS measured time outdoors after school and objective physical activity in English children: the PEACH project. International journal of behavioural nutrition and physical activity, 22 (7) 31. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-7-31

- Cowman, K., 2017. Play streets: women, children and the problem of urban traffic, 1930–1970. Social history, 42 (2), 233–256. doi:10.1080/03071022.2017.1290366

- D’Haese et al., 2015. Organizing “Play Streets” during school vacations can increase physical activity and decrease sedentary time in children. International journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity, 12, 14. doi:10.1186/s12966-015-0171-y

- Department of the Environment, 1973. Children at play: design bulletin 27. London: HMSO.

- DfT, 2013. UK government traffic statistics Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/tra01-traffic-by-road-class-and-region-miles

- Ferguson, A. and Page, A., 2015. Supporting healthy street play on a budget: a winner from every perspective. International journal of play, 4 (3), 266–269. doi:10.1080/21594937.2015.1106047

- Foreman, H., 2017. Residential street design and play: a literature review of policy, guidance and research on residential street design and its influence on children’s independent outdoor activity. Bristol: Commissioned and published by Playing Out.

- Gill, T., 2017a. Street play initiatives in disadvantaged areas: experiences and emerging issues. London: Play England.

- Gill, T., 2017b. Snow 1, Snapchat 0 and why this result matters. Retrieved from: https://rethinkingchildhood.com/2017/12/13/snow-snapchat-outdoor-play-tech-social-media/#more-6627

- Griffin, E., 2015. Hackney play streets: rethinking, re-materializing and representing public life on streets (Unpublished Dissertation for MSc in Urban Studies at University College London.)

- Guardian, 2016. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/mar/25/three-quarters-of-uk-children-spend-less-time-outdoors-than-prison-inmates-survey

- Hart, J. and Parkhurst, G., 2011. Driven to excess: impacts of motor vehicles on the quality of life of residents of three streets in Bristol UK. World Transport Policy & Practice, 17 (2), 12–30. [ ISSN 1352-7614].

- Hart, R., 2002. Containing children: some lessons on planning for play from New York City. Environment & Urbanization, 14 (2), 135–148. doi:10.1177/095624780201400211

- Health Survey for England, 2015. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/health-survey-for-england-2015

- Hillman, M., 2006. Children’s rights and adults’ wrongs. Children’s Geographies, 4 (1), 61–67. doi:10.1080/14733280600577418

- Hillman, M., Adams, J., and Whitelegg, J., 1990. One false move: a study of children’s independent mobility. London: Policy Studies Institute.

- Independent, 2004. Available from: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/this-britain/battery-reared-children-miss-out-on-play-547211.html

- Jacobs, J., 1961. The death and life of great American cities. New York: Modern Library edition.

- Jarvis, H., 2018. Envisioning liveability and do-it-together urban development. In: K. Ward, et al., eds. The Routledge handbook on spaces of urban politics. London: Routledge, 336–349.

- Layard, A., 2013. Temporary play street orders: advice on legality and procedure. Retrieved from: http://playingout.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Legal-basis-for-Temporary-Play-Street-Orders-.pdf

- Lester, S. and Russell, W., 2008. Play for a Change. London: Play England/NCB.

- Lynch, K., 1977. Growing up in cities: studies of the spatial environment of adolscence in Cracow, Melbourne, Mexico City, Salta, Toluca and Warszawa. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

- Matthews, M.H., 2003. The street as a liminal space: the barbed spaces of childhood. In: P. Christensen and M. O’Brien, eds. Children in the city: home, neighbourhood and community. London: Routledge, 101–117.

- Page, A.S., et al., 2009. Independent mobility in relation to weekday and weekend physical activity in children aged 10–11 years: the PEACH project. The international journal of behavioural nutrition and physical activity, 6, 2. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-6-2

- Page, A.S., et al., 2017. Why temporary street closures for play make sense for public health. London: Play England.

- Percy-Smith, B., 2002. Contested worlds: constraints and opportunities in city and suburban environments in an English Midlands town. In: L. Chawla, ed. Growing up in an urbanizing world. London: Earthscan.

- Peymane, A., et al., 2018. Effectiveness of a childhood obesity prevention programme delivered through schools, targeting 6 and 7 year olds: cluster randomised controlled trial (WAVES study). BMJ, 360, k211.

- Play England, 2010. ICM survey for Playday. Available from: http://www.playday.org.uk/campaigns-3/previous-campaigns/2010-our-place/

- Playday, 2007. Opinion Poll survey results. http://www.playday.org.uk/resources/research/2007-research/

- Playing Out, 2010a. Playing out June 2010 project report. Available from: http://playingout.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/finalreport2010.pdf

- Playing Out, 2010b. Possible Concerns Available from: http://playingout.net/why/possible-concerns/

- Playing Out, 2012. Bristol’s temporary play street order trial, September 2011–12 Available from: http://playingout.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/TPSO-final-report-Sept-2012.pdf

- Playing Out, 2015. A turn in the road. Blog post by resident activator Clare Rogers. Available from: http://playingout.net/a-turn-in-the-road/

- Playing Out, 2017. Survey of playing out streets: summary and report. Available from: http://playingout.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Playing-Out-Survey-Report-2017.pdf

- Sallis, J.F., Owen, N., and Fisher, E.B., 2008. Ecological models of health behavior. In: K. Glanz, B.K. Rimer, and K. Viswanath, eds. Health behavior and health education. 4th ed. United States of America: John Wiley and Sons, 465–485.

- Sandercock, G., 2018, quoted in article Available from from: https://www.essex.ac.uk/news/2018/01/22/least-fit-child-20-years-ago-would-be-among-today%E2%80%99s-fittest

- Schalkwijk, A.A.H., et al., 2018. The impact of greenspace and condition of the neighbourhood on child overweight. European journal of public health, 28 (1) 88–94. ISSN 1101-1262 doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckx037

- Shaw, B., et al., 2013. Children’s independent mobility: a comparative study in England and Germany (1971–2010). London: Policy Studies Institute.

- Tight, M., et al., 1998. Casualty reduction or danger reduction: conflicting approaches or means to achieve the same ends? Transport policy, 5 (3), 185–192. doi:10.1016/S0967-070X(98)00016-X

- Tranter, P. and Doyle, J.W., 1996. Reclaiming the residential street as play space. Published in international play journal, 4, 91–97.

- Voce, A., 2015. Policy for play. London: Policy Press.

- Ward, C., 1978. The child in the city. London: The Architectural Press.