ABSTRACT

This paper is concerned with the strategic policy processes, economic structures and tactics within which age and plac e programmes are formed, implemented and evaluated. The research draws on the Multiple Streams Approach to understand the relationship between problem identification, policy processes and politics and how they come together to respond to the needs of older people. Drawing on Belfast (UK) the paper examines the interactions between planning, health and social policies in the creation of an age-friendly city. The data questions the claim to age-friendliness given the way in which older people are increasingly shifted from the asset-rich urban core to the suburban periphery. It highlights the need to understand how structural processes, the property economy and an emphasis on speculative development have favoured policies based on gentrification in general and youthification in particular. The paper reflects on the limitations of the Multiple Streams Approach but also shows that the challenge of ageing and place is not simply one of weak integration or poor governance. The way in which interests, policies and politics shape better outcomes for older people needs to be factored into initiatives to create a more inclusive approach to urban planning.

Introduction

Ageing has emerged as one of the defining features of urban restructuring as a range of international organisations, pressure groups, governments and academics have evaluated its implications for service provision, the economy and neighbourhood design (Buffel and Handler Citation2018). The policy emphasis on keeping older people at home for as long as practicable has also focused attention on what type of housing, communities and transport we will need and how planning, public health and social care should work together to create more age-friendly places (WHO Citation2007). The World Health Organization (WHO) age-friendly concept encourages cities to proof their plans and policies and adopt a more participatory approach to programme delivery in partnership with the older community. Age-friendly Belfast in Northern Ireland (UK) adopted the WHO guidelines in 2014, and this paper explores the way in which problems, policies and politics interact in the creation of a more inclusive city. It examines a range of urban policies and how they have evolved in response to demographic restructuring, the scope and integrative quality of programmes and the relationship between competing narratives of the city, who it is for and how it should be planned. In this context, the analysis draws on Healey’s work on politics and planning that sees space socially as well as physically produced, in which a range of actors in planning, housing, public health and communities have a material stake in the use, management and development of places (Healey Citation2010).

The empirical focus is Belfast, a city where space and identity are intimately connected, especially after nearly three decades of violence (1969–1996) between nationalists who broadly want to reunify Ireland and unionists, who mainly want to stay in the United Kingdom (UK) (Bollens Citation2018). The period of violence was paralleled by de-industrialisation, as the city lost much of its economic base to heavy engineering, textiles and shipbuilding and a major redevelopment and motorway programme that hollowed-out whole swathes of the population from the inner-city (Herrault and Murtagh Citation2019). The Good Friday Agreement and the subsequent Northern Ireland Act (1998) established a devolved parliament at Stormont, the Power-sharing Executive and in 2015, a stronger role for new local authorities in land use planning and economic development. The Assembly experienced a number of suspensions as the (unionist) Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and (nationalist) Sinn Féin have found it difficult to build trust and maintain collective government (Bollens Citation2018). The point is not so much about the particular politics of Northern Ireland, but to show that it is a dynamic institutional and policy arena in which the pressures of an ageing society cut across traditional ethno-religious identities.

To understand how ageing and place are then processed and shaped within these contexts, this paper draws on the Multiple Streams Approach (MSA), specifically because of its explanatory potential in unsettled policy regimes (Cairney and Jones Citation2016). John Kingdon’s (Citation1984, Citation2014) original formulation of MSA argued that policy making happens under conditions of uncertainty, in which there are competing claims, actors and political ambitions within a loosely defined arena. Ambiguity is a core assumption of MSA, which has three key elements. The first is that participation in organisations is fluid and turnover of policymakers is high as in reality they ‘drift from one decision to the next’ (Zahariadis Citation2014, p. 27). The second is that a clear policy objective is often rare as due to time constraints, politicians tend to make decisions without clearly articulating their preferences and indeed the lack of clarity may even enable policymaking. Third, it is often unclear to political and policy actors, what processes they have at their disposal, jurisdictional boundaries are blurred and ‘turf battles’ between different departments and agencies are common (Zahariadis Citation2014, p. 27).

MSA has been applied in a number of policy arenas including public health (Lencucha et al. Citation2018), physical activity (Milton and Grix Citation2015) and gender violence (Colombini et al. Citation2016) and has evolved over time and place in response to a range of criticisms and refinements (Knaggård Citation2015). Rawat and Morris (Citation2016) point out that this approach has been effectively applied to UK policy, especially in health, using primarily qualitative and case study methods. Fundamentally, they argue that it is not a universal framework effortlessly transferred to other political cultures, problems or administrative contexts, but a way to think about policy rather than a theory of policy’ itself (Rawat and Morris Citation2016, p. 682, italics authors original). Engler and Herweg (Citation2019, p. 906) agree that its applicability depends on ‘what is the question’ and whether MSA fits the particular dynamics being researched. Here, Amin (Citation2013, p. 476) warns against ‘telescopic urbanism’ and fragmentary observations at the expense of a wider understanding of the structural explanations for urban change, which is where MSA has a specific analytical role to play.

The key components of MSA and its applications are discussed in the next section. This sets up a description of the age and place policy arena with a particular focus on Belfast which, in turn, informs the methodology consisting of semi-structured interviews, a review of policy documents and analysis of statistics on demographic shifts in the city. This focuses on the connections and disconnections between ageing and territorial policies (planning, urban regeneration, transport, housing and so on) and programmes (public health, social care and older people) that have a clear spatial impact. These conclusions reflect the strengths and limitations of multiple streams as a way of understanding the politics of age in contemporary cities and what this means for policymakers and practitioners concerned with healthy places more broadly.

Multiple streams approach

Kingdon’s (Citation1984, Citation2014) original ideas on agenda setting and policy processes were formed in the specific conditions of Federal government structures in the United States (US) (Rozbicka and Spohr Citation2016). This emerged during the transition to Reganism in the early 1980s and focused on the relationship between problem identification, policy evaluation and the influence of the ‘body politic’ (including interest groups and the media) on decision-making outcomes (Béland and Howlett Citation2016, p. 222). The three strands of the model are:

The problem stream is concerned with the way in which issues attract policy attention, how they are framed cognitively and whether they represent an immediate response to crises or emerge gradually through feedback from existing programmes. The capacity of a problem to attract attention is also conditioned by the competence of the policy and political stream to deal with it.

The policy stream focuses on the way in which these problems are filtered through decision-making systems, state officials and often complex institutional regimes. Experts and analysts consider these issues, evaluate alternatives and identify the feasibility of options for implementation.

The political stream is dominated by elected representatives and institutions but Kingdon recognises that pressure groups, the media, academics, lobbyists and NGOs also shape policy outcomes and their distributive effects.

Policy windows

These streams form and reproduce more or less independently, until a ‘policy window’ brings them into relation with each other, often in unstructured ways (Herweg et al. Citation2019). The window can be opened by elections, crisis events, funding rounds and new legislation, but their formation creates opportunities for a mix of actors to enter. Howlett and Ramesh (Citation2003) identify four types of windows. In routinized political windows, institutional processes (principally elections) determine predictable opportunities for change, but they may also be discretionary in that individual politicians can create conditions to take advantage of particular events. Third, are spillover problem windows, in which a range of related issues and claims create new opportunities in an already open window and finally, random problem windows, such as a crisis or national emergency (Howlett and Ramesh Citation2003, p. 37). The window opens an opportunity to ‘couple’ the problem, policy and political stream and here the policy entrepreneur plays a vital role in reconfiguring the relationship between the three in order to achieve a particular outcome (Jones et al. Citation2016).

Herweg (Citation2017) argues that insufficient attention has been paid to how and why the policy window opens. For example, it might occur where a firm problem-solution connection is established (say bringing a draft bill into a legislative arena); or where the stream is clearly defined and tightly regulated (through parliamentary committee structures). However, once the window is open, it does not necessarily mean that the outcome will be preferential to a particular interest group. For example, Lencucha et al. (Citation2018) show how tobacco companies in Canada redesigned their devices or shifted to smokeless products to get around restrictions on flavoured tobacco, even though the political and policy stream firmly coupled to ban it. The ‘age-friendly city’ agenda in Belfast opened a type of discretionary window through the designation of WHO status, but as the analysis shows there are complexities to the way in which ideas travel through the streams, the barriers they invariably face and the extent to which they compete with other narratives to shape policy outcomes and political commitments.

How streams work

Béland and Cox (Citation2016) place particular emphasis on ideas through their ‘role as “coalition magnets”, which we define as the capacity of an idea to appeal to a diversity of individuals and groups and to be used strategically by policy entrepreneurs (i.e. individual or collective actors who promote certain policy solutions) to frame interests, mobilize supporters and build coalitions’ (Béland and Cox Citation2016, p. 429). The way in which ideas serve as coalition magnets relies on three factors. First, policy entrepreneurs need knowledge to challenge, disrupt or seek a new definition of the problem. Second, ideas need to be accepted and championed by key actors, capable of delivering change through access to resources, legislation or political leverage. Third, the ideation process involves bringing actors together where they might have been indifferent to the issue or oppositional (even antagonistic) to each other. In this respect, ideas are power-laden because they are ‘interpretations of the material world by our emotions and values. As causal beliefs, ideas posit relationships between things and events’ (Béland and Cox Citation2016, p. 430). This process of framing is critical to the performance of effective policy entrepreneurs and by necessity, it needs to be deliberately vague and polysemic in order to draw in (or at least avoid the defection of) the stakeholders necessary for change:

This positive role of ambiguity is related to the fact that ideas help actors define their interests, and that broader – and vaguer – ideas are more likely to appeal to a greater number of constituencies that have heterogenous preferences. (Béland and Cox Citation2016, p. 432)

Ideas with a higher level of positive valence are more likely to attract a broader base because each stakeholder can identify a net gain from participation, regardless of the advantage it offers other, even competitor interests. In this task, rhetorical skills and discursive strategies are critical to tailor the offer to each one in ways they see as relevant. Béland (Citation2009) acknowledges that ideas are more likely to become influential when leading political parties accept and actively promote them. Here, politicians and especially policymakers will take comfort if the approach is recognisable or where previous applications have proved to be low risk. The WHO Age-friendly Cities approach is itself an important framing device, validated by its adoption globally and endorsed by international researchers, experts and national governments. The availability of ‘readymade policy’ is particularly useful where there is a conservative attitude to innovation or where the political and financial risks may concern politicians (Unwin et al. Citation2017, p. 10). Löblová (Citation2018) points out that the simple presence of knowledge is therefore insufficient for policy leverage and even well-established epistemic communities are constrained by the problem context within which they operate. Here, epistemic communities are conceived as networks of competent experts within a particular policy arena who share normative values and beliefs combined with a broadly agreed set of objectives. This distinguishes them from interest groups or policy communities and while they need to form coalitions and bargain within political arenas, it is their scientific coherence that explains their importance. Knowledge and ideas are tactical resources, which becomes more important where the policy requires a degree of technical expertise and when professionals (such as planners) dominate decision-making processes (Lawrence Citation2020).

Policy entrepreneurs and networks

Policy entrepreneurs can help to identify or open the window, but their main role is in ‘coupling’ policy problems, solutions and political opportunities in a given context (Kingdon Citation1984, p. 21). Such convergence necessitates ‘focusing events’ but invariably, these are unpredictable and entrepreneurs need to act quickly to capitalise on often limited opportunity windows (Zohlnhöfer et al. Citation2016). Béland (Citation2017) later develops the idea of the policy entrepreneur into ‘identity entrepreneurs’ as they draw on and amplify existing identities that may not be fully formed to promote an alternative to the established problem stream. By necessity, the age-friendly concept needs to attract a wide range of actors who may not necessarily have an immediate concern for older people but who hold resources needed to deliver change. Such actors might have limited understanding of the issues, the risks that come with participation or how other organisations might respond to their involvement (Zamora et al. Citation2019).

Sætren is critical of Kingdon’s understanding of the policy entrepreneur as an insider because it ‘has too much focus on the situational, temporal and human agency elements at the expense of systematic institutional factors’ (italics authors original) (Sætren Citation2016, p. 73). Zahariadis (Citation2016) also argues that policy entrepreneurs are far more complex and tactically astute, showing how they employ manipulating strategies including framing the problem as gains or losses and ‘salami tactics’, which involves building consensus at specific points in the decision-making process. The success of the policy entrepreneur is therefore based on their personal (and interpersonal skills), their ability to manipulate allies, an open policy window and importantly, occupying a privileged position within the policy and the political stream.

Reardon (Citation2018) argues that MSA pays insufficient attention to the linkages between these streams and how they in turn relate to extra-local interests, networks and interpersonal relationships. In reality, most organisations rely on each other for the legal, financial and political resources that need to be ‘exchanged’ in order to achieve specific aims (Reardon Citation2018, p. 462). The organisation with the most resources dominates and can exercise authority over coalitions by setting ‘the rules of the game’, which ultimately shape the exchange process. Reardon largely internalises these relationships, whereas Pierce et al. (Citation2017) highlight the importance of advocacy coalitions, the stability of networks and how policymakers interact with both allies and opponents outside official streams. They argue that policy actors are more likely to be conservative than outsiders, but unofficial actors are also constrained because they acknowledge the damage that disruptive behaviours can do to the integrity of the group. Moreover, in arenas where routine policy practices are dominated by professional cultures, it can be difficult for secondary actors to challenge core beliefs in either the problem or the policy stream (Wellstead Citation2017).

Limits and refinements

The roles of secondary actors and advocates are also shaped by the structures of government and the levels at which they operate. Zahariadis (Citation2016) points out that the original model distinguished between open, hierarchical, and specialised organisations. Open structures connect a range of decision-makers to any opportunity whilst hierarchical organisations link key decision makers to a limited set of choices. In specialised structures, where technical expertise and systemic cultures prevail, connections are limited and professionally enclosed. The conceptual separation of problems from solutions is also artificial as participants in decision-making processes usually integrate these as a bundle of motivations and claims (Bache Citation2020). For example, Robinson and Eller (Citation2010) applied MSA to education policy and showed that relationships are far more fluid and overlapping than streamed in self-contained ways. Actors who participate in one stream are likely to participate in another (teachers and unions both identify problems and lobby politicians) and outsider groups (parent organisations) are not necessarily crowded out by other policymakers or elected officials. Moreover, external actors change their relationship with each other and drop claims in order to build stronger alliances to effect policy change, shifting the contours of the stream as new opportunities and barriers emerge (Fitch-Roy and Fairbrass Citation2018). In short, the streams are dynamic and situational, in that they need to be understood in particular regimes where multiple policy processes can be observed in practice. The next section describes the arena in Belfast where place, economics and older people’s policies are brought into relation in the development and implementation of the age-friendly programme.

Research design and the multiple stream arena

Healey (Citation2010) defines the arena as a network of actors and institutions with a material interest in the policy field and here specifically, how demography relates to the use, management and development of land. MSA is partly about tracing the networks established between such interests via three streams but emphasises the empirical discovery of relationships across time, structure, people and organisations. attempts to define the scope and composition of the policy arena as a framework to apply MSA to ageing and urban change in Belfast. It describes stakeholders with an interest in place (planning, urban policy, infrastructure, housing); older people (the public sector, Commissioner for Older People, NGOs and age networks); health (social care, public health, Healthy Cities) and politics (in the devolved administration as well as in the local authority). These interests are distributed across different sectors (public, private and voluntary); levels of government and governance (regional, local, intermediate and community); and actors (politicians, policymakers, programme managers, as well as community and voluntary sector activists). This is, of course, not complete, but attempts to map out the age-place regime and the explanatory value of MSA to understand its performance, politics and effects on the lives of older people.

Prominent in the structure is the Healthy Ageing Strategic Partnership (HASP) that delivers the Age-friendly Belfast (AfB) strategy in partnership with the city’s Greater Belfast Senior Forum (GBSF) and their six constituent neighbourhood groups. The Public Health Agency, Health and Social Care Trust and the Council have created the Belfast Health Development Unit (BHDU) to coordinate programmes to tackle health inequalities in the city. Indeed, much of the infrastructure around health and the city represents a form of institutional coupling by coordinating disparate agencies, programmes and actors in more coherent ways. Public transport is operated by a single authority, Translink, under the Department for Infrastructure (DfI) who are also responsible for strategic planning, roads and footpaths. In 2015, local authorities took on responsibility for land use planning but urban regeneration functions remained within the Department for Communities (DfC), who also have responsibility for the main older people’s strategy (Active Ageing) and the Commissioner for Older People.

The research design involved an analysis of policy and programme documents produced by key institutions in health, urban policy, planning and the city council. This then, informed a series of semi-structured, in-depth interviews with representatives from the main organisations, although these developed over time to identify and survey other interests with a stake in the policy arena. The questionnaire examined, inter alia, how respondents understand and prioritise problems; set and deliver their objectives; interact with other policy and political interests; and monitor and evaluate the impact of their programmes. Twenty-two interviews were completed with:

Central government officials n = 6;

Public sector agencies n = 4;

Local government officials n = 2;

NGOs and community groups n = 4;

Private sector (developers/planners) n = 2;

Policy researchers in the age sector n = 2; and

Politicians at regional and local authority level n = 2.

The third strand examined population restructuring in the city and in particular how the spatial distribution of older people has changed in the last two decades. The transcripts from the in-depth interviews were subjected to thematic analysis which Braun and Clark describe as ‘a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within the data’ (Braun and Clarke Citation2006, p. 79). In their extensive body of work, they developed a six-stage methodology for undertaking thematic analysis to reveal underlying meanings, replicated trends and consistency within rich text data (Braun and Clarke Citation2006, Citation2020). This involves:

1. Familiarisation with the data via close reading by a lead researcher to avoid ‘inter-rater reliability’ caused when multiple readers take different meanings and interpretations from the same text (Braun and Clarke Citation2020, p. 7).

2. Generating initial codes across the respondents, based on repeated words, terms and phrases.

3. Searching for and identifying potential connecting themes from the nodes is established, although these are kept open and interpretative in processing the script.

4. Reviewing the themes enables the thematic map to be drafted and agreed with the range of researchers involved in data gathering and analysis.

5. The themes are then defined and named and coherence established within each one to avoid duplication and overlap with other themes.

6. Reporting and illustrating the theme content, but also validating each one in the context of the research objectives and the broader literature on cities and ageing (based on Braun and Clarke Citation2006, p. 87).

Multiple themes emerged at stage five but here we focus on three for more detailed consideration. At first, the codes to emerge were not related to ageing specifically, but to the way in which the property market, planning system and housing policy work together to change the spatial demography of the city. Linked to this, older people’s services and facilities (such as transport, walking and mobility) are emphasised in the policy discourse but that does not necessarily translate into resource commitments or the actual delivery of programmes. Second, codes around the disconnected nature of decision-making and the role of beneficiaries in governance structures all emphasise the problems with coupling and the relative strength of older people over other interest groups. Third, respondents highlighted the agency, influence and impact on older people themselves, yet this dimension of MSA is conceptually weak. Thematic mapping draws out narratives across stakeholders but also reflects the strengths and limitations of broader theoretical explanations of policy, population and urban restructuring.

Issue 1: dominant policy streams in place making

The first issue concerns the policy theme and specifically, government departments, agencies and private sector groups with a role in the use, development and management of land including planning, urban policy, infrastructure and housing. This centres on property rights and the way in which the state, via regulatory planning and discretionary zoning, incentivises and de-risks speculative investment, especially in the Central Business District (CBD) and along the waterfront. Land assembly, decontamination and infrastructure provision (roads, water, sewage and utilities) dominate the Regional Development Strategy for Northern Ireland (2035) and related planning policy statements and development control guidance. The problem is framed in highly technocratic ways, but in particular by the overarching need to modernise Northern Ireland after decades of violence, de-industrialisation and a failure to connect to the high-growth, global service economy (Brownlow and Birnie Citation2018). Growth, competitiveness and creating an enabling environment for investment are dominant tropes. This sees planning and urban regeneration focus on renewing the commercial core and facilitating elite projects, especially the redevelopment of the former shipyard in Titanic Quarter and in the Cathedral Quarter, where Ulster University (UU) is developing a new 17,000 student campus, due to be completed in 2022.

Kelley et al. (Citation2018) have been critical of the way in which age-friendly approaches focus on the immediate aspects of everyday life at the expense of wider structural, economic, political and regulatory processes. Here, Kelley et al. see a necessary strategy of ‘erasure’ in which certain groups are rendered invisible or are devalued in the way in which problems are framed, policies are shaped and how parties value their political usefulness (Kelley et al. Citation2018, p. 52). Strategic planners are especially unclear about how older people and ageing are represented in high-level policies and laws.

The Planning Act (2011) points us as planners to look at the overall issue – it’s not a reference to health and wellbeing … I’m sure there is a reference to ageing somewhere but I can’t find it. (Strategic government planning official)

Older people are expressed as an enclosed demographic that will primarily change the number, size and type of housing the planning system, through Development Plans, is required to produce. According to the Local Development Plan 2035 for Belfast, older people are reduced to housing indicators and related estimates of land use needs. There is little mention in the Plan about how they use open space or parks, the importance of physical activity and walking or where designated housing would be located relative to shops, services and transport hubs. Older people are not erased from the strategic planning narrative, but they are firmly bracketed within projective techniques and housing need assessments. The ‘epistemic community’ in as far as a coherent field exists relies on technocratic knowledge and the normative certainties they provide for both politicians and policymakers.

Moreover, the city develops slowly and development is contingent on the performance of the regional economy, infrastructure investment and most importantly, the private sector. Age-friendly places are not an instant fix and retrofitting the city is a patient and unpredictable process:

Change is slow and you are kind of stuck with the built environment you’ve got … our places basically stayed broadly the same, there are small incremental changes over the years, so people tend to think planning is a mechanism to change everything and improve everything quite quickly, but it’s not. (Strategic government planning official)

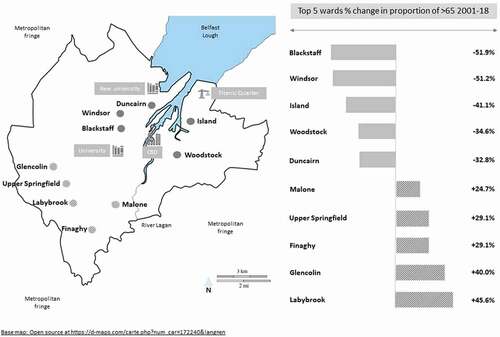

Planning and development processes are slow, especially in second-order settlements that lack the capital base to pursue fully fledged urban development models. However, it is the incremental and less visible nature of the decisions, actors and manoeuvres and in particular outcomes that explain the changing distribution of older people across the city. Belfast grew only marginally between 2001 and 2011 from 277,392 people to 280,962, an increase of 1.29%. The population aged over 65 declined from 42,370 to 40,891 or −3.49% over the same period, despite an 18% increase in their numbers in Northern Ireland as a whole (NISRA Citation2020). The spatialization of these processes explains most about the way in which the planning system and property market work together to produce differential outcomes for older people. shows that between 2001 and 2018 the proportion of people aged over 65 declined in the inner-city from 14.1% to 11.7% at the same time as the outer suburbs and metro-fringe increased significantly. In 2001, people over 65 whereas likely to live in the inner-city as in the metropolitan fringe, but by 2018 the gap widened by 6.8%, the sharpest of any category. Moreover, there is also a concentration of poverty and poor health in Belfast, especially in some areas where older people are concentrated. Whilst people overall are living longer, there is a difference in life expectancy between the most deprived and the least deprived neighbourhoods of 5.6 years for females and 9.2 years for men (AfB Citation2018, p. 22). Older people, especially in peripheral housing estates that lack services, health facilities and reliable transport, face multiple socio-economic and health problems that are accentuated by their geographic isolation.

The OECD (Citation2015, p. 35) examined 275 metropolitan areas and identified a ‘core-to-hinterland’ gap, where the increase of older people in the suburbs has been outpacing the inner-city over the last three decades. shows the top five electoral wards in terms of the increase or decrease in the proportion of people aged over 65. Island and Duncairn are separately impacted by major waterfront and university campus redevelopments, respectively, while Windsor and Blackstaff are proximate to the Queen’s University campus, the main teaching hospital and a concentration of the service economy to the south of CBD. The ring of wards in the outer-south and west characterise, in part, the hinterland model described by OECD, but they also cut across high-value housing markets (Malone) to more deprived communities (Glencolin).

The housing association sector is well aware of these pressures in terms of site availability for older people’s social housing, the cost of land assembly and the general thrust to remake Belfast city centre as a cosmopolitan space. There is a distinct ‘lack of progress toward mixed tenure, which is about mixed communities (where there) will be social rent, affordable rent, houses for sale and with specific housing for older people’ (Housing association representative). Part of the problem is that planning instruments such as conditions, development gain and age-specific zonings have not been used to pursue such outcomes. Transport planners were especially critical of the weak use of planning gain to leverage more socially and demographically integrated neighbourhoods and how they could subsidise new bus connections:

At the moment we’re running short of £0.5m a year in planning gain … planners are quite happy to write a cheque (for large scale developments) with pump-prime services and infrastructure (but will not) future-proof bus routes (Public transport manager).

Issue 2: the limits and potential of coupling

The problem here is that such negotiations are often ‘hidden’ (Housing association representative), necessarily because it ‘protects sensitive commercial and confidential information’ where investments are being ‘risked’ by the private sector (Property development representative). In short, there are aspects of stream dynamics that are not open to public scrutiny in which the interactions between interests, politicians and policy processes may be harder to unravel (Fox-Rogers and Murphy Citation2014). Indeed, it can be seen that the policy stream reflects a particular idea of the city embedded in strategies of youthification, in general and studentification in particular (Moos et al. Citation2019) in that ‘you’ve had a big push toward student accommodation in the city centre … so Belfast will become a very young centre and maybe older as you go further. The city centre tends to be asset rich so older people’s housing (with) good access to amenities, good access to pharmacies, hospitals and shops and the sort of stuff to reduce isolation is needed’ (Housing association official). Herrault and Murtagh (Citation2019) show that there is currently approval for 7,000 units of student accommodation in the city centre and that housing associations are pushed onto cheaper sites were services and transport connections are comparatively poor. A community planning aid organisation pointed out that two development sites originally designated for social housing in the Cathedral Quarter have been dropped and are now approved for student accommodation and car parking linked to the new university campus.

It is not the slow nature of urban change that explains constrained options for older people, but everyday decisions and redevelopment programmes that accumulate to reshape the city centre as a place for some people over others. The main physical regeneration programme Improving Places (DfC Citation2013) aims to renew the public realm and the appearance of CBD as well as its connection to new investment sites including Titanic Quarter and the Cathedral Quarter. Public health officials were especially critical of the superficiality of the proposals, the lack of concern for the mobility needs of older people and the nature of the consultation itself:

The architects came to give the people on the Healthy Ageing Strategic Partnership a talk on it but I was struck by the fact that it didn’t seem to be a requirement on the architects or anybody on that project to do a health impact assessment. (Public health services manager)

Similarly, Translink argued that public transport was the ‘weakest link in the chain’ because they cannot always get access to footpaths for low floor buses, integrate with sheltered accommodation or plan more flexible services where there are known concentrations of older people. For transit and health authorities, this is the type of programme coupling that is needed to think through, in problem stream terms, how a city might be future-proofed. Similarly, housing officials argued that we need to re-examine transport options for older people, the growth in suburban mobility and how roads, footpaths and public spaces will need to be re-imagined:

… you look at the types of transport for older people, scooters, accessible transport, accessible taxis - we know that some eighty thousand scooters are being used in the UK every year and (will) become a major mode of transport and our pathways, our public spaces will need to change. (Housing association representative)

The public realm is more than functional for older people. It is a site of encounter, which with age segregation and ‘increasing levels of loneliness (these) present significant challenges to the age-friendly concept’ (Age NGO representative). AfB and Belfast Healthy Cities (BHC) developed a joint approach based on the latter’s initial walkability assessments that involved older people identifying obstacles in the journey from home to shops, parks and health services. This showed that footpaths are increasingly commercialised (with extended restaurants and bars, advertising boards and street performers); surfaces are a fall risk; cars are parked over the kerb; and older people compete with runners, cyclists and prams for space (BHC Citation2014). The footpath, as a social space for older people, challenges the narrow way in which it is framed in primarily functional terms. Here, the research performs something of a cognitive challenge to the way in which planners and urban managers think about the public realm as infrastructure, primed for development. The emphasis is on the consumption rather than the production of space and is to some extent an entrepreneurial manoeuvre that has brought the Department for Infrastructure (DfI) into the restructured HASP in the second phase of the strategy. It has not necessarily produced better outcomes for older people but it can be read as a process of coalition building in which age-friendly structures have drawn in outsider interests and their ways of working. Interviews with infrastructure professionals suggest a mix of motives and strategies involved in their inclusion. Primarily, they acted as ‘good citizens’, keen to offer their expertise and play a part in planning the city, but they also wanted to monitor any implications for their brief, for the Minister politically and in particular, for resources. As one NGO put it, ‘you are always better off inside the tent’. They could also explain their approach, justify specific decisions (that may not always be age-friendly), overcome objections and smooth the path to implementation. AfB also knows that it is a transactional process and that they cannot push particular interests to the point where they withdraw or dilute their presence. Several participants noted how, over time, some members tend to send more junior staff, so that they still invest, but their participation becomes increasingly ineffectual. What is also interesting is the intra-issue tension between roads, footpath infrastructure and the public realm policy on one hand and public transport on the other. The different logics of production and consumption in transport alone reveal deeper complexities and contradictions within policy streams as well as across them.

Issue 3: valence, entrepreneurship and stream integration

Health and Wellbeing: Delivering Together 2026 (HSCB Citation2016) is the main strategy for health and social care and sets out the needs of a rapidly ageing population in which a person-centred model will focus on prevention, early intervention, supporting independence and improving wellbeing. A central part of the new approach is to build the capacity of neighbourhood groups, realign community development with wellbeing outcomes and ultimately care for people in their own home for as long as practicable. Again, the criticism is that resources do not follow the rhetoric and that it is the absence of effective coupling mechanisms that are the most significant barrier to change:

For older people who are in hospital (and) able to move back into the community, housing is a key enabler to make that agenda happen … (but) there’s been a 10% decrease in supporting people funding, so it has not kept up. (Housing association sector representative)

For some, the barrier is created by an overriding economic logic to the way in which programmes are designed and in particular, how older people are priced in semi-market forms of delivery. This involves public–private partnerships, contracting out and strengthening the independent sector, including NGOs and social enterprises, to implement programmes (Durand et al. Citation2015). The problem is a costly one; the policy a marketized one; and the politics are constrained by the fiscal implications of an ageing society. A declining tax base and rising dependency ratios leave little financial headroom, not least after a decade of austerity. The rhetoric might be user-centred and age-inclusive, but the reality is a cost-driven model in which value extraction, not values, dictates service delivery:

What we have now is a very fragmented independent set of little businesses all providing social care. So, I would talk about the commodification of care, we’ve made it into a business rather than really it being about what the person’s needs are, it’s all costed and measured in units of time. (Health and social care professional)

The issue of resources and how they relate to different modes of policy making is repeated in the older peoples’ strategy for Northern Ireland. The Active Ageing (DfC Citation2016) strategy also locates the problem in the shifting demographics of the region, the pressure on health and care services and the need to keep older people physically active and living at home for as long as possible. It aims to achieve this through the ‘coordinated delivery’ of housing, reliable transport, an adequate income and by promoting community safety (DfC Citation2016, p. 7). According to one official, the strategy has ‘drifted’ in the 3 years the Assembly was suspended, but commitment to its delivery across departments was already weak:

We’re not the police of the Active Ageing strategy … there’s no enforcement mechanism or anything. It’s a political strategy, which I think holds people to the actions we want to see. (Public sector official)

The idea of strategies as containers of existing commitments, is a form of superficial coupling in which actors may be present but not active in the implementation of a different approach. This may create the type of positive valence necessary to build an internal coalition, but if it fails to evolve (or even monitored), its ability to disrupt or realign any particular stream remains weak.

At the city level, AfB co-ordinates a programme of work under the management of HASP, which reports to Councilors on the All-party Group on Older People within Belfast City Council. In governance terms, AfB is strongly connected to GBSF, itself comprised of representatives from six area-based age networks. The first strategy operated between 2014 and 2017, with the revised plan covering 2018–22 and there has been significant progress for older people over that period. AfB (Citation2017) shows that the proportion of older people who feel that the city is a place where they ‘can live life to the full’ increased from 79% in 2014 to 84% in 2017 and that satisfaction with public transport increased from 63% to 70% over the same period. Older people are more physically active, volunteer more and feel safer in their neighbourhood after dark (AfB Citation2017, p. 6). Again, most of the proposals are for other agencies to deliver or are existing commitments within current policies and programmes. There is comparatively little in the way of direct delivery as the strategy is primarily concerned with identifying research priorities (barriers to services); raising awareness (access to welfare support); a call for better coordination (loneliness and isolation); and more effective consultation with older people’s groups (in the active travel plan).

There are criticisms of the lack of new resources devoted to the actions, representation across key areas, including by planners and the extent of leverage that it can exercise over mainstream policies and in particular finance. Even policymakers recognise that these types of ‘strategies can be forward looking but they also contain a lot of business as usual and things which have already started or tweaking things which are already in place’ (Central government official). To some extent, this misses the point about HASP and the value of the age-friendly strategy. It is necessarily polysemic, inclusive and facilitative because it aims to create positive valence and incentivise participation to achieve some coherence around a pro-age approach. Its managers act entrepreneurially, to a degree, by building the coalition through a form of conceptual coupling in which the benefits of participation are not outweighed by competition from other actors.

These entrepreneurial tactics are also political. Older people are what one politician called ‘safe’ because age is not embroiled in the same rivalries and resource competition as sectarian identity claims. It remains something of a ‘Cinderella topic’ (Political representative), neither likely to get you into power nor punished by the electorate. Indeed, the age-friendly cities concept now recognised by 760 global cities is exactly the signifier post-conflict Belfast wants to project (WHO Citation2018, p. 7). The ready-made legitimacy of the framework brought in politicians and more importantly policymakers, with the security that this is a recognisable but also a performative designation. While the assemblage of structures, policies and multiple streams might mean that ‘older people get lost in the whole dysfunction of how Northern Ireland works’ (COPNI representative), it does not mean that it is an ineffectual arena.

GBSF is politically active and holds monthly meetings with councilors, policymakers and academics on a range of issues that they define along with the G6 network. However, some in the age sector as well as in government agencies feel that this has encouraged, what Kelley et al. (Citation2018, p. 52) call ‘microfication’, a focus on immediate gains rather than on the broader processes of inequality. Local networks have persistently raised the frequency, flexibility and quality of bus services and GBSF has also discussed a concessionary fare scheme that has provided people over-60 with free transport since 2007. However, given the deep cuts in public spending, the Northern Ireland Assembly (NIARIS Citation2017, p. 1) produced a paper asking ‘is the continued provision of free transport for 60–64 year olds sustainable?’ and pointed out that other jurisdictions in Britain and Ireland have reviewed or removed entitlements or kept a 65-year limit. The transport authority was explicitly critical of free public transport for older people (not an insignificant gain) because it was at the expense of the (largely unprofitable) wider bus network:

I mean older people as a group tend to be better at voting and so I think it’s always been quite central across the political parties. This was set up quite a while back, the Translink passes for over-sixties, and so it’s a big DUP issue. (Public sector transport planner)

Transport planners point out that the concessionary fare allowance to Translink does not recover full operating costs but that the then (DUP) First Minister recognised it was ‘a vote catcher’. DUP in particular draws on an older electorate and GBSF recognised the threat and pointed out the way in which the scheme tackles loneliness and promotes physical activity. Their relationship with age-friendly structures and interests and ability to confront politicians and policymakers provided community groups with access and a degree of solidarity, especially with public health officials locally and regionally. However, it shows that the public interest is poorly articulated within MSA and that older people, social movements and informal coalitions lack definition within and between the three streams.

Conclusions

The value of the Multiple Streams Approach is that it helps to unravel the policy regime and how it delivers particular outcomes for older people. It highlights both the strength of the ‘friendliness’ discourse as a platform to build a coalition of interests, but also its risk as an empty signifier. The entrepreneurial capacity of community actors and officials to broaden the age strategy into policy and political streams (and to evidence the progress that has been made) underscores the potential of localised governance as a political space. It also emphasises the importance of the problem stream and in particular, how issues are defined and framed to favour some policy options over others. The need for a competitive city, a lean cost-efficient public sector and affordably priced health care in the context of increasing (demographic) demand, has shifted policy towards semi-market or fully fledged privatized delivery across planning, housing and social care. These processes are contestable and the age-policy arena reveals a range of tactics and methods to work around the various constraints of political structures. Building a coalition of interests involves a mix of entrepreneurial practices including interpersonal contacts; leveraging political capital; convincing incomers of the benefits and minimising the costs to more reluctant participants.

However, MSA has limitations that reveal some deeper insecurities about ageing in place and how it is resourced as an inclusive strategy for the city. First, a particular model of urban development based on the property economy emphasises structural explanations and challenges in creating a genuinely age-friendly city. The productive functions of the state, necessary to enable such forms of regeneration, are strategically critical, corporate in their mode of working and are primarily located in central, hard-to-reach departments and agencies. Land use policy in the form of zoning, infrastructure and public realm works; financial and fiscal incentives; and exclusions (social housing) determine the material shape of the city, who gets access and who does not. The age-friendly agenda in Belfast has made progress in the consumption arena (transit, public health and housing) or at least, it has buy-in from state agencies on particular issues. In short, MSA suggests that power does not reside exclusively in the political stream as all sorts of power (and especially property capital) appear to have privileged access to the policy stream in a way that older people simply do not. Social housing providers might want to develop asset-rich and well-connected sites in the city centre, but they have been evidently losing out to gentrifiers, students and a professional class, emblematic of the new post-conflict Belfast.

This relates to a second criticism of the multiple stream approach. How people, in this case older people, are framed and understood as active agents within the model is poorly developed. MSA concentrates on structural processes and instrumental logics that tend to abstract decision-making to known categories and actors. The public interest and various social movements that are not formally constituted have significant agency in policy making. Their weight, as has been shown here, is comparatively weak, certainly compared with elected representatives and civil servants operating in the political and policy streams, respectively. They are a class in their own right that has leverage but can also be marginalised in which the processes of exclusion as well as related countermoves need to be better understood within the real politic of MSA.

Third, MSA sees outcomes explained in linear streams but underplays the scales at which issues are debated, who has access to them and how they relate to each other (or not). The concern for some is that partnership models on ageing are too devolved and focus too much on neighbourhood concerns in a way that cannot unsettle the political or policy streams where key decisions are taken. How governance arenas resist such social formations or restructure to focus on material priorities (say social housing in the city centre) is an area for further study, not least to understand the tactics, alliances and institutions that are constitutive of democratised coupling strategies.

Finally, the approach, based on the particular conditions of the US, emphasises the potential of the policy entrepreneur but as suggests, the scope for individual agency is constrained by the complexity (if not necessarily effectiveness) of even localised administrative structures. More importantly, here are networks, not just to strengthen the ‘coalition magnet’ but to operate outside formal systems; penetrate individual or multiple streams; define the problem in more preferential ways; and mobilise to open new or protect existing policy windows. Networks (in this context at least) have political potential but further research could explore the extent to which they offer an alternative site of organisation that does not rely on explicitly entrepreneurial practices. It is, of course, necessary to integrate policies in the making of healthy cities but it is also important to recognise that the problems of coordination go well beyond a system breakdown that can be fixed by calls for better integration. How various forms of power and resources flow through and across these streams is also an area for study in making cities more economically, socially and demographically inclusive.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Brendan Murtagh

This paper emerged from an international and interdisciplinary research collaboration on healthy urban ageing. The research lead (Geraint Ellis) is a planner and environmentalist who brought together experts in policy analysis (Brendan Murtagh), ageing and the built environment (Sara Ferguson), public health (Claire Cleland) and physical activity (Ruth Hunter) to better understand the relationship between ageing, mobility and the city. Ruibing Kou specialises in the relationship between open space and the home and the team from the University of Paraná brought particular expertise in measuring physical activity (Adriano Akira Ferreira Hino), the environmental determinants of healthy ageing (Leonardo Augusto Becker) and on the interface between policy, politics and health (Rodrigo Siqueira Reis). Ciro Rodriguez Añez from the Federal University of Technology, Paraná is a specialist in physical education and how exercise empowers older people to improve their mobility and use of the city.

References

- Age-friendly Belfast (AfB), 2017. Age-friendly Belfast plan 2018-2021: a city where older people live life to the full. Belfast: AfB.

- Age-friendly Belfast (AfB), 2018. Age-friendly Belfast progress report April 2018. Belfast: AfB.

- Amin, A., 2013. Telescopic urbanism and the poor. City, 17 (4), 476–492. doi:10.1080/13604813.2013.812350.

- Bache, I., 2020. Evidence, policy and wellbeing. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Béland, D., 2009. Ideas, institutions, and policy change. Journal of European public policy, 16 (5), 701–718. doi:10.1080/13501763.2015.1115533.

- Béland, D., 2017. Identity, politics, and public policy. Critical policy studies, 11 (1), 1–18. doi:10.1080/19460171.2016.1159140

- Béland, D. and Cox, R.H., 2016. Ideas as coalition magnets: coalition building, policy entrepreneurs, and power relations. Journal of European public policy, 23 (3), 428–445. doi:10.1080/13876988.2016.1174410.

- Béland, D. and Howlett, M., 2016. The role and impact of the multiple streams approach in comparative policy analysis. Journal of comparative policy analysis: research and practice, 18 (3), 221–227. doi:10.1080/13876988.2016.1174410.

- Belfast Healthy Cities (BHC), 2014. Walkability assessment for healthy ageing. Belfast: BHC.

- Bollens, S., 2018. Trajectories of conflict and peace: Jerusalem and Belfast since 1994. London: Routledge.

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V., 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3 (2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V., 2020. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative research in psychology, 1–25. doi:10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238.

- Brownlow, G. and Birnie, E., 2018. Rebalancing and regional economic performance: Northern Ireland in a Nordic mirror. Economic affairs, 38 (1), 58–73. doi:10.1111/ecaf.12267.

- Buffel, T. and Handler, S., eds, 2018. Age-friendly cities and communities: a global perspective. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Cairney, P. and Jones, M.D., 2016. Kingdon’s multiple streams approach: what is the empirical impact of this universal theory? Policy studies journal, 44 (1), 37–58. doi:10.1111/psj.12111.

- Colombini, M., et al., 2016. Agenda setting and framing of gender-based violence in Nepal: how it became a health issue. Health policy and planning, 31 (4), 493–503. doi:10.1093/heapol/czv091.

- Department for Communities (DfC), 2013. Belfast city centre public realm masterplan report and update. Belfast: DFC.

- Department for Communities (DfC), 2016. Active ageing strategy 2016-21. Belfast: DFC.

- Durand, M., et al., 2015. An evaluation of the public health responsibility deal: informants’ experiences and views of the development, implementation and achievements of a pledge-based, public–private partnership to improve population health in England. Health policy, 119 (11), 1506–1514. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.08.013.

- Engler, F. and Herweg, N., 2019. Of barriers to entry for medium and large ‘n’ multiple streams applications: methodological and conceptual considerations. Policy studies journal, 47 (4), 905–926. doi:10.1111/psj.12235.

- Fitch-Roy, O. and Fairbrass, J., 2018. Negotiating the EU’s 2030 climate and energy framework: agendas, ideas and European interest groups. New York: Springer.

- Fox-Rogers, L. and Murphy, E., 2014. Informal strategies of power in the local planning system. Planning theory, 13 (3), 244–268. doi:10.1177/1473095213492512.

- Healey, P., 2010. Making better places: the planning project in the 21st century. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Health and Social Care Board (HSCB), 2016. Health and wellbeing: delivering together 2026. Belfast: HSCB.

- Herrault, H. and Murtagh, B., 2019. Shared space in post-conflict Belfast. Space and polity, 23 (3), 251–264. doi:10.1080/13562576.2019.1667763.

- Herweg, N., 2017. European union policy-making: the regulatory shift in natural gas market policy. New York: Springer.

- Herweg, N., Zahariadis, N., and Zohlnhöfer, R., 2019. The multiple streams framework: foundations, refinements, and empirical applications. In: P. Sabatier, ed. Theories of the policy process. 4th ed. London: Routledge, 17–53.

- Howlett, M. and Ramesh, M., 2003. Studying public policy: policy cycles and policy subsystems. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jones, M.D., et al., 2016. A river runs through it: a multiple streams meta‐review. Policy studies journal, 44 (1), 13–36. doi:10.1111/psj.12115.

- Kelley, J., Dannefer, D., and Masarweh, L.I., 2018. Addressing erasure, microfication and social change: age-friendly initiatives and environmental gerontology in the 21st century. In: T. Buffel, S. Handler, and C. Philipson, eds. Age-friendly cities and communities – a global perspective. Bristol: Policy Press, 51–71.

- Kingdon, J., 1984. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. London: Harper Collins.

- Kingdon, J., 2014. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. 2nd international ed. Pearson: Harlow.

- Knaggård, Å., 2015. The multiple streams framework and the problem broker. European journal of political research, 54 (3), 450–465. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12097.

- Lawrence, R.J., 2020. Collective and creative consortia: combining knowledge, ways of knowing and praxis. Cities and health, 1–13. doi:10.1080/23748834.2020.1711996.

- Lencucha, R., et al., 2018. Opening windows and closing gaps: a case analysis of Canada’s 2009 tobacco additives ban and its policy lessons. BMC public health, 18 (1), 13–21. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-6157-3.

- Löblová, O., 2018. When epistemic communities fail: exploring the mechanism of policy influence. Policy studies journal, 46 (1), 160–189. doi:10.1111/psj.12213.

- Milton, K. and Grix, J., 2015. Public health policy and walking in England-analysis of the 2008 ‘policy window’. BMC public health, 15 (1), 614–623. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1915-y.

- Moos, M., et al., 2019. The knowledge economy city: gentrification, studentification and youthification, and their connections to universities. Urban studies, 56 (6), 1075–1092. doi:10.1177/0042098017745235.

- Northern Ireland Assembly Research and Information Service (NIARIS), 2017. Is the continued provision of free travel for 60-64 year olds sustainable? Belfast: NIARIS. Available: https://www.assemblyresearchmatters.org/2017/12/08/is-the-continued-provision-of-free-travel-for-60-64-year-olds-sustainable/ [Accessed Jan 2020].

- Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA), 2020. 2019 mid-year population estimates for Northern Ireland. Belfast: NISRA.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2015. Ageing in cities. Paris: OECD Publications.

- Pierce, J., et al., 2017. There and back again: a tale of the advocacy coalition framework. Policy studies journal, 45 (S1), S13–S46. doi:10.1111/psj.12197.

- Rawat, P. and Morris, J.C., 2016. Kingdon’s ‘streams’ model at thirty: still relevant in the 21st century? Politics and policy, 44 (4), 608–638. doi:10.1111/polp.12168.

- Reardon, L., 2018. Networks and problem recognition: advancing the multiple streams approach. Policy sciences, 51 (4), 457–476. doi:10.1007/s11077-018-9330-8.

- Robinson, S.E. and Eller, W.S., 2010. Participation in policy streams: testing the separation of problems and solutions in subnational policy systems. Policy studies journal, 38 (2), 199–216. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00358.x.

- Rozbicka, P. and Spohr, F., 2016. Interest groups in multiple streams: specifying their involvement in the framework. Policy sciences, 49 (1), 55–69. doi:10.1007/s11077-015-9227-8.

- Sætren, H., 2016. From controversial policy idea to successful program implementation: the role of the policy entrepreneur, manipulation strategy, program design, institutions and open policy windows in relocating Norwegian central agencies. Policy sciences, 49 (1), 71–88. doi:10.1007/s11077-016-9242-4.

- Unwin, N., et al., 2017. The development of public policies to address non-communicable diseases in the Caribbean country of Barbados: the importance of problem framing and policy entrepreneurs. International journal of health policy and management, 6 (2), 71. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2016.74.

- Wellstead, A., 2017. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose? A review of Paul Sabatier’s ‘An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein’. Policy sciences, 50 (4), 549–561. doi:10.1007/s11077-017-9307-z.

- World Health Organization (WHO), 2007. Global age-friendly cities: a guide. Geneva: WHO.

- World Health Organization (WHO), 2018. The global network for age-friendly cities and communities: looking back over the last decade, looking forward to the next. Geneva: WHO.

- Zahariadis, N., 2014. Ambiguity and multiple streams. In: P. Sabatier, ed. Theories of the policy process. 3rd ed. Boulder, CO: Westfield Press, 25–58.

- Zahariadis, N., 2016. Delphic oracles: ambiguity, institutions, and multiple streams. Policy science, 49 (3), 3–12. doi:10.1007/s11077-016-9243-3.

- Zamora, F.M.V., et al., 2019. Use of community support and health services in an age-friendly city: the lived experiences of the oldest-old. Cities and health, 1–10. doi:10.1080/23748834.2019.1606873.

- Zohlnhöfer, R., Herweg, N., and Huß, C., 2016. Bringing formal political institutions into the multiple streams framework: an analytical proposal for comparative policy analysis. Journal of comparative policy analysis: research and practice, 18 (3), 243–256. doi:10.1080/13876988.2015.1095428.