ABSTRACT

Rationale/Purpose

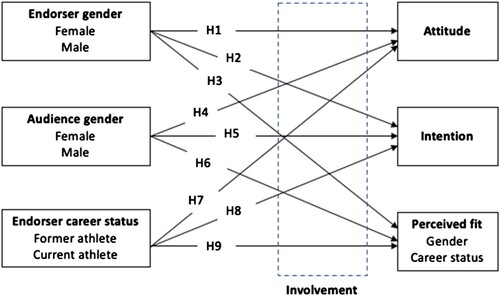

We investigated the role of gender (both endorser and audience) and career status on young people’s attitude, participation intention and perception of fit in the context of a social marketing campaign promoting sport and physical activity participation.

Design/Methodology/Approach

In a 2 × 2 × 2 experiment, the eight conditions were based on endorser gender (female and male), endorser career status (current and former) and participant gender (female and male). Participants were aged between 16 and 24 years.

Findings

Endorser’s gender, career status and participants’ gender had no significant effect on attitude and intention related to the social marketing campaign. However, endorser gender significantly influenced participants’ perceptions of gender fit, and perceptions of career status fit. Either a current or former female athlete was perceived as a better fit than a male athlete endorser. Furthermore, the career status of an endorser significantly impacted perception of career status fit, but only for participants who were highly involved in sport and physical activity.

Practical Implications

Using former athletes is a more-than-viable strategy, and both male and female endorsers are equally likely to facilitate behaviour change in young adults.

Research Contribution

Social marketing campaigns promoting promote sport and physical activity can leverage the celebrity capital of retired athletes.

Social marketing campaigns promote the adoption of prosocial behaviours and therefore have widespread importance (Huhman et al., Citation2005). Social marketing campaigns aim for consumers to accept a new behaviour, reject a potential behaviour, modify a current behaviour or abandon an old behaviour (Kotler et al., Citation2002). Social marketers have a number tools at their disposal to promote participation in sport and physical activity. One of these is the use of athlete endorsers as part of a wider promotional campaign. An athlete endorser as a person who shares their identity or social status to promote a product, brand or service, or to raise awareness about an issue. An athlete endorser is a type of celebrity endorser, but likely different from fitness influencers who rely heavily on self-developed content distributed via social media (Kubler, Citation2023). Social marketing strategists have a variety of athlete endorsers to select from, but have little guidance on which endorser characteristics will resonate (or not) with the target audience.

Recent research highlights that, in the context of social marketing, celebrity endorsers are not all created equal, and that there is growing interest on how endorser traits explain differences in campaign effectiveness (Schimmelpfenning & Hunt, Citation2020). For example, race and gender of endorsers can impact perceptions of source credibility, source favourability, homophily, message reactance, message evaluation and behavioural intention (Schartel Dunn & Nisbett, Citation2020). The same research called for future research on celebrity endorsement in social marketing to consider a variety of (unspecified) contexts. We seek to contribute to this line of social marketing research by investigating the role of endorser gender and career status on participants’ attitude, participation intention and perception of fit in the context of a social marketing campaign designed to encourage young people to be more physically active.

Promoting sport and physical activity is important. The World Health Organization (WHO) recognises the contribution of public health initiatives to many of the United Nation’s sustainable development goals. Physical inactivity remains “a major, unresolved public health challenge” (p. 1163). An estimated 23% of adults and 81% of adolescents (aged 11–17 years) failing to achieve sufficient levels of physical activity (World Health Organization, Citation2022).

Celebrity athletes have a profound influence on young people (Mikuláš & Shelton, Citation2021; Xu et al., Citation2021). Young people perceive athletes as role models and/or sports heroes who they admire, look up to and after whom they model their behaviours (Reid, Citation2017). Athlete role models can positively affect young adults purchase intentions and behaviour (Shin & Lee, Citation2021). Yet, “young adults can be discerning when it comes to athletes as role models” (Leng & Phua, Citation2022, p. 164), and many young people are without realistic sport and physical activity role models (Young et al., Citation2015). Hence, selecting the most appropriate athlete to promote sport and physical activity participation is challenging.

This research provides novel insights of the athlete endorser effect on participants’ attitudes, intentions and perceptions of fit. Furthermore, gender is explored from the perspective of both the audience and the endorsers. Gender differences in consumer behaviour are both intriguing and frequently consequential (Meyers-Levy & Loken, Citation2015). For consumer psychologists, understanding gender differences in cognitive processing styles, affective responses and reactions to marketing stimuli foreshadows product choices and preferences. Unsurprisingly, “gender is a common building block of the customer portfolio” (p. 130). Gender portrayals in advertising have begun to attract more attention from practitioners and industry leaders (Mohan et al., Citation2022). This reflects changing societal and cultural dynamics such as those reflected in the SeeHer movement (www.seeher.com) which seeks to increase the representation and accurate portrayal of all women and girls in marketing, media and entertainment. The career status of endorsers (i.e. either current athlete or former/retired athlete) is also included as a variable in the experiment. Little is known about the career status of athletes, an unavoidable endorser characteristic. Former/retired athletes may still possess brand equity and retain their potential to influence consumer behaviours and perceptions (McDonald, Citation2016). As endorsers, they are less likely to transgress and subsequently compromise the credibility or reputation of an organisation engaged in social marketing (Dickson et al., Citation2018). This study also illuminates the role of endorser gender when pursuing behaviour change in young adults. A final feature of the study was consideration of the intersectionality between endorser characteristics such as gender and career stage. The findings of this study can inform the design of endorsement-based social marketing campaigns because it highlights how endorser selection impacts participants’ attitude, participation intention and perception of fit in the context of a social marketing campaign.

Background and hypothesis development

Celebrity athlete endorsement

Advertising is a common promotional tool used to reach consumers and communicate product benefits. However, messages may be lost because target audiences are experiencing advertisement overload (Muda et al., Citation2012). In this cluttered and highly competitive environment, endorsement is becoming more common because it can better capture a target audience’s attention and transfer value (Lohneiss & Hill, Citation2014). A celebrity endorser is a person who has public recognition and who can accompany an advertisement (McCracken, Citation1989). Their public recognition helps make a brand more entertaining and trustworthy (Atkin & Block, Citation1983). Some celebrity endorsers are also well-known athletes. Athlete endorsers are more influential than non-athletes when endorsing a sport-related brand or service (Fink et al., Citation2012).

A single framework is insufficient to “holistically explain effective endorsements due to the inherent variability of advertised products” (Schimmelpfenning & Hunt, Citation2019, p. 489). Therefore, we rely on the match-up hypothesis (Till et al., Citation2008; Till & Busler, Citation2000), the source credibility theory (Hovland & Weiss, Citation1951; Pornpitakpan, Citation2004) and source attractiveness theory (McGuire, Citation1985) to provide an appropriate theoretical framework for our context and hypotheses.

The premise of the match-up hypothesis is that endorsers are more effective when there is an endorser–product congruency (Chen et al., Citation2012; Fink et al., Citation2012; Till et al., Citation2008; Till & Busler, Citation2000). Endorser–product congruency enhances likability and perceived trust (Koernig & Boyd, Citation2009), believability (Erdogan et al., Citation2001), attitudes towards the product or service (e.g. Chen et al., Citation2012; Till et al., Citation2008; Till & Busler, Citation2000) and purchase intention (e.g. Fink et al., Citation2012; Fleck et al., Citation2012). Although endorser–product match-up is important, so too is endorser–audience fit (e.g. Bailey & Cole, Citation2004; Kim & Cheong, Citation2011; Till, Citation1998). Considering a three-way match-up (i.e. product–endorser–audience fit) is fundamentally important. Congruence between athlete endorser, products and target audience is the second most important factor after costs when selecting an athlete endorser with a risk of negative publicity (Charbonneau & Garland, Citation2005). This study fills a gap by examining a three-way match-up between campaign, endorser and audience based on endorser and audience gender as well as endorser’s career status.

Source credibility theory proposes that the effectiveness of a message depends upon the perceived level of expertise and trustworthiness associated with an endorser or communicator (Hovland & Weiss, Citation1951; Pornpitakpan, Citation2004). Trustworthiness refers to the source’s perceived honesty and reliability, whereas expertise is the perception of the source’s skills and competence in delivering genuine and accurate information (Halder et al., Citation2021). Source attractiveness theory (McGuire, Citation1985) posits attractiveness as the third characteristic of a credible source of communication. Attractiveness incorporates likability (i.e. consumer affection for the endorser), similarity between endorser and the consumer, and familiarity (i.e. consumer knowledge of the endorser) (Frank & Mitsumoto, Citation2021).

Assessing endorsement

Three common means to assess endorsement are attitudes, intentions and perception of fit. These measures are antecedents of behaviour itself, have been used extensively in endorsement research (Bailey & Cole, Citation2004; Chen et al., Citation2012; Fleck et al., Citation2012) and are therefore the outcomes of interest here. Involvement should also be considered when assessing endorsement in this context. It exists “when a social object is related by the individual to the domain of the ego” (Havitz & Dimanche, Citation1990, p. 179). Involvement is linked to communication persuasiveness in advertising settings because it can stimulate personal connection between the receiver and a related message (Petty et al., Citation1983). The construct is included in the current research as a covariate because individual’s involvement plays a significant role in attitude change and may impact consumers’ responses (Beaton et al., Citation2011; Petty et al., Citation1983; Rice et al., Citation2012).

Endorser gender

Endorser gender is an under-investigated construct in the endorsement literature (Tzoumaka et al., Citation2016). Males are far more likely to feature as celebrity endorsers, especially in the context of sport (Fink et al., Citation2012). This likely reflects the “often culturally masculinised context” of sport (Forsdike & O’Sullivan, Citation2022, p. 4). However, there is evidence that advertisements featuring a female celebrity are evaluated more favourably than those featuring a male celebrity, and that attitudes toward female endorsers are more favourable than male endorsers (Klaus & Bailey, Citation2008). Previous research regarding sport and physical activity suggests that females are perceived as appropriate endorsers for sport and physical activity (Behnoosh et al., Citation2017). On this basis, several hypotheses related to the impact of endorser gender on attitude, participation intention and campaign fit are proposed. The hypotheses are:

H1: Controlling for involvement, attitude towards a social marketing campaign promoting sport and physical activity is more positive with a female celebrity athlete endorser than a male celebrity athlete endorser.

H2: Controlling for involvement, participation intention related to a social marketing campaign promoting sport and physical activity is higher with a female celebrity athlete endorser than a male celebrity athlete endorser.

H3: Controlling for involvement, perception of gender fit is higher for a social marketing campaign promoting sport and physical activity with a female celebrity athlete endorser than a male celebrity athlete endorser.

Audience gender

Audience characteristics matter when it comes to endorsement effectiveness (Premeaux, Citation2009) although the evidence does not always suggest that females and males perceive endorsement differently (Bhutada & Rollins, Citation2015; Bush et al., Citation2004).

Young male adults are more likely to recognise athletes than females (Peetz et al., Citation2004) but it’s not yet clear what the means for endorsement effectiveness. The selection of the right endorser based on how males and female participants are likely to respond is important, but further evidence is needed on how this is perceived in the context of a social marketing campaign. Further, the interaction between the gender of an endorser and the gender of the participant (audience) can influence endorsement effectiveness when the population of interest are young adults (Peetz et al., Citation2004). Younger students, females and individuals living on campus were more likely to be aware of MoveU, a social marketing initiative aimed at increasing moderate-to-vigorous physical activity among undergraduate students (Scarapicchia et al., Citation2015). How this works for an endorsed campaign remains unknown. Females are more likely to buy products endorsed by female athletes (Bush et al., Citation2005) but again there are no studies exploring this in a sport and physical campaign context. Based on the evidence, it is likely that females will respond more positively to the social marketing campaigns in this research. So, two hypotheses related to audience gender are tested in the current research in conjunction with attitude and participation intention:

H4: Controlling for involvement, female participants have a more positive attitude towards an endorsed social marketing campaign promoting sport and physical activity than male participants.

H5: Controlling for involvement, female participants have higher participation intention related to an endorsed social marketing campaign promoting sport and physical activity than male participants.

H6: Controlling for involvement, perception of gender fit is higher when the gender of the celebrity athlete endorser matches the gender of the participant.

Endorser career status

Athlete endorsers have a capital life cycle which changes over a career (Carrillat & Illicic, Citation2019) and likely into retirement as well. Known as the celebrity capital life cycle (Carrillat & Illicic, Citation2019), the model stipulates that the celebrity capital fluctuates throughout different stages (i.e. acquisition, consolidation, downfall/decline and redemption/resurgence) over time. This lens for athlete endorsement research is in its very early stages and is yet to contrast during-career (i.e. current athlete) and post-career (i.e. retired athlete) status. There are indications it is worth exploring though. In a discussion of charitable ambassadors, McDonald (Citation2016, p. 259) wrote that “further analysis of the social value and longevity of retired elite athletes is warranted”. The author went on to suggest that retired athletes could reach various audiences and serve as catalysts for social change. Retired athletes may prove to be a good choice for endorsement as a result of trustworthiness. They may be less risky than current athletes (Hassan et al., Citation2005) and may also have less propensity to be involved in scandal which can be very problematic (Ge & Humphreys, Citation2021; Lohneiss & Hill, Citation2014)

Although some evidence exists that older retirees may actually be less credible (Widrick & Raskin, Citation2010) thereby making them inferior endorsers, many athletes retire comparatively younger than other professions so likely retain credibility they may lose much later. In fact, it has been suggested that former/retired athletes celebrity capital may be retained (Hassan et al., Citation2021). Younger retired athletes must learn that continued exercise is the key to their lifelong health (Jones & Denison, Citation2019, p. 834) and this phenomenon may create a compelling and believable narrative as an endorser.

All in all, there is a need to better understand how athletes of varying career status “match-up” (Chen et al., Citation2012; Fink et al., Citation2012; Till & Busler, Citation2000) to the context of a social marketing campaign to drive sport and physical activity. Therefore, an exploration of career status is theoretically justifiable based on the match-up hypothesis. Furthermore, the source credibility and source attractiveness model support our focus on career status. The former athlete is likely to be familiar. The former athlete may also be perceived as being more similar to the audience than a current athlete because they are no longer an elite athlete. The following hypotheses are also tested in this study to further explore endorser career status, attitudes, intentions and perceptions of fit related to an endorsed social marketing campaign:

H7: Controlling for involvement, attitude towards a social marketing campaign promoting sport and physical activity is more positive with a former athlete rather than a current athlete as a celebrity endorser.

H8: Controlling for involvement, participation intention related to a social marketing campaign promoting sport and physical activity is higher with a former athlete rather than a current athlete as a celebrity endorser.

H9: Controlling for involvement, perception of career status fit is higher for a social marketing campaign promoting sport and physical activity with a former athlete than a current athlete as a celebrity endorser.

Method

Procedure

To test the hypotheses, we conducted an experiment featuring a 2 × 2 × 2 factorial design. The effect of independent variables (i.e. endorser gender, endorser career status and participant gender) on dependent variables (i.e. attitudes, intentions and perceived gender/career status fit) were tested while controlling for participants’ psychological involvement in sport and physical activity (). The eight conditions were based on endorser gender (female and male), endorser career status (current and former) and participant gender (female and male). Male and female participants were randomly assigned to the endorser gender and career status condition groups.

Consistent with recent endorsement in social marketing research (Schartel Dunn & Nisbett, Citation2020), we recruited university students. A total of 447 undergraduate students at a New Zealand university were recruited across different subject areas. The 392 usable questionnaires (48.5% female, 51.4% male) exceeded the minimum sample size requirement (237) as calculated using G*Power. Fifty-five questionnaires were eliminated due to incomplete responses or respondent being out of the target age range for the study (18–24). Participants had an average age of 19.8 years and the project was approved by a university-based research ethics committee.

Measures

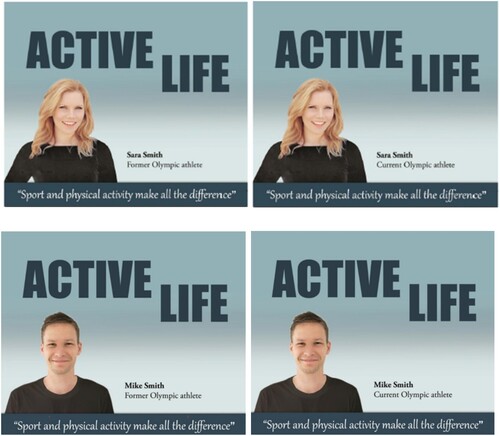

Mock social marketing advertisements including photos of an unknown endorser were created to control for familiarity effects and eliminate the influence of attitudes that participants may have brought to the experiment (Chen et al., Citation2012; Till & Busler, Citation2000). Two photographs of unknown endorsers (one female, one male) with fictitious names were utilised in this study to avoid confounding independent variables (i.e. career status and gender) with other characteristics of the endorser such as attractiveness, expertise and trustworthiness. Two popular names were chosen for the endorsers (Sara and Mike), with an identical surname (Smith). The models used to depict the unknown endorsers were siblings aged three years apart which provided a degree of similarity of facial appearance. The endorser’s athletic career status (i.e. current or former) was conveyed to participants below the photographs with a short description. To enhance credibility, the advertisements were developed by a professional graphic designer. The images for a female current and former athlete are presented as .

The four advertisements were embedded within separate questionnaires capturing the gender and career status conditions. Each questionnaire had an identical set of items measuring the other variables which in some cases were adapted for context: demographics, involvement’s three dimensions (i.e. centrality, symbolic value and hedonic value; Beaton et al., Citation2011; α = .96), attitude towards the social marketing campaign (Till & Busler, Citation2000; α = .89), participation intentions (Till & Busler, Citation2000; α = .97), gender (α = .89) and career-status fit (α = .91). The latter two scales were adapted from Till and Busler (Citation2000) and Fleck et al. (Citation2012). Items were adjusted for male, female and career status conditions. Please refer to .

Table 1. Questionnaire items.

Statistical assumptions

Prior to testing group differences, data normality and homogeneity of variance were assessed for all dependent variables. A Shapiro–Wilk test (p > .05); values of skewness and kurtosis; and an inspection of histograms, Q–Q plots and box plots for all eight groups indicated that responses on the attitude, participation intention, perceived gender fit and perceived career status fit variables were approximately normally distributed. The homogeneity of variance assumption was also explored for all four outcome variables using Levene’s tests. Equal variances for attitude (F (7,384) = .91 p = .47), participation intention (F (7,384) = .88 p = .52), gender fit (F (7,384) = 1.99 p = .05) and career status fit (F (7,384) = .62 p = .74) were uncovered which supports the assumption.

Likewise, assumptions were carefully considered related to the series of two-way between-subjects ANCOVAs that were to be carried out involving the four dependent variables (i.e. attitude, participation intention, perceived gender fit and perceived career status fit). This involved consideration of linearity and homogeneity of regression slopes.

For attitude towards the campaign, the scatter plot, along with deviation from linearity (F (52) = 1.19 p = .18) suggested that the assumption of a linear relationship between attitude and involvement had been met. The assumption of homogeneity of regression slopes was also checked through both a scatter plot and the General Linear Model (GLM) interaction term between involvement and the independent variables (D'Alonzo, Citation2004). Although the scatter plot showed some interactions between the covariate and experimental manipulation, the p-values of the ANOVA interaction term of the GLM revealed support for the homogeneity of regression slopes assumption for all independent variables: endorser gender (F (1,384) = .04, p = .84), endorser career status (F (1,384) = .13, p = .72) and participants’ gender (F (1,384) = .12, p = .73). A p-value of over .10 indicates that the interactions in the scatter plot are not a significant problem and ANCOVA remains robust for the model (D’Alonzo, Citation2004).

Both a visual inspection of the scatter plot, and a deviation from linearity test revealed support for the linearity assumption between the intention variable and involvement (F (52) = .73, p = .91). Overall, participation intention increased when participants were highly involved. Furthermore, evidence from an inspection of the scatter plot and p-values of the ANOVA interaction term of the GLM revealed support for the assumption of homogeneity of regression slopes (F (1,384) = .14, p = .71; F (1,384) = .07 p = .78; F (1,384) = .08, p = .78).

An inspection of the scatter plot and a test for deviation from linearity for perceived fit (endorser gender), revealed a linear relationship between the perceived fit variable and involvement (F (52) = 1.35 p = .06). Evidence also emerged supporting the homogeneity of regression slopes assumption both from the scatter plot and the interaction term of the GLM, F (1,384) = .46, p = .50; F (1,384) = .03, p = .86; F (1,384) = 1.67, p = .20.

Evidence supporting the linearity assumption for perceived fit (career status) was generated through an inspection of scatter plot and deviation from linearity test (F (52) = 1.34, p = .07). The homogeneity of regression slopes assumption was supported for the interaction between endorser gender with involvement (F (1,384) = .39, p = .53); and participants’ gender with involvement (F (1,384) = .31, p = .58). However, the assumption was not met for the interaction between endorser career status with involvement (F (1,384) = 3.95, p = .048). Due to the heterogeneity of regression slopes for the career status variable (p < .05), an alternative Picked-Point Analysis was used to compare former/current athlete groups at different levels of the covariate. ANCOVA remained robust when comparing the other groups varying on endorser gender and participant (audience) gender.

Results

Attitudes towards the campaign

After controlling for participants’ psychological involvement, ANCOVA revealed that endorser gender (F (1,383) = .44, p = .51, η2 < .01), endorser career status (F (1,383) = 1.74, p = .19, η2 < .01) and participants’ gender (F (1,383) = .14, p = .71, η2 < .01) did not significantly affect participants’ attitudes towards the campaign. These results provided evidence refuting H1, H4 and H7. In addition, two-way interactions between the independent variables were insignificant. However, the three-way interaction between independent variables was significant (F (1,383) = 7.03, p = .01, η2 = .02). Furthermore, participants psychological involvement as a covariate remained significant in the model (F (1,383) = 11.45, p < .01, η2 = .03). In terms of endorser career status, the attitude adjusted mean scores of male participants towards the campaign endorsed by the former athlete (adj M = 4.57, SE = .18, 95% CI [4.23, 4.92]) were higher than for the campaign endorsed by the current male athlete (adj M = 4.16, SE = .18, 95% CI [3.81, 4.50]). For female participants, the group with the female former athlete endorser had higher adjusted mean scores (adj M = 4.52, SE = .18, 95% CI [4.17, 4.87]), than those in the female current athlete endorser groups (adj M = 3.95, SE = .18, 95% CI [3.60, 4.31]).

Participation intentions

ANCOVA results showed that the independent variables (i.e. endorser gender, endorser career status and participants’ gender) had no significant effects on participants’ intentions, which was evidence to reject H2, H5, and H8 respectively. In addition, the two-way interactions (F (1,383) = .47, p = .49, η2 < .01; F (1,383) = .61, p = .44, η2 < .01; F (1,383) = .00, p = .97, η2 < .00), and three-way interaction (F (1,383) = 3.57, p = .06, η2 = .01) among independent variables were insignificant. The covariate, psychological involvement, remained significant F (1,383) = 18.30, p < .01, η2 = .05. The adjusted means in all groups were calculated after considering the effect of participants’ involvement in sport and physical activity. Male participants in the group with the campaign advertisement endorsed by the male former athlete had the highest adjusted mean (adj M = 3.25, SE = .23, 95% CI [2.79, 3.70]), while the campaign endorsed by the female former athlete had the lowest adjusted mean (adj M = 2.78, SE = .22, 95% CI [2.35, 3.21]). In contrast, for female participants, intention was higher for those in the campaign endorsed by the female former athlete (adj M = 3.22, SE = .23, 95% CI [2.77, 3.67]), while those in the campaign endorsed by the male former athlete reported the lowest adjusted mean (adj M = 2.83, SE = .23, 95% CI [2.37, 3.29]).

Endorser gender fit

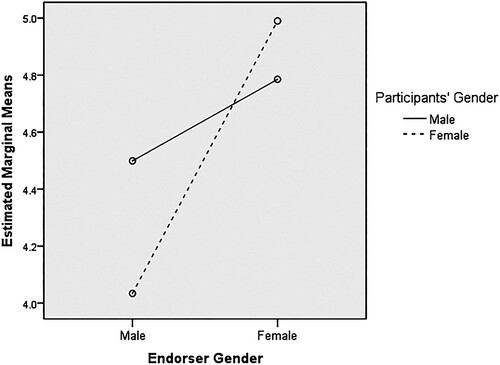

ANCOVA indicated that endorser gender had a significant effect on participants’ perception of endorser gender fit (F (1,383) = 36.15, p < .01, η2 = .08), although the effect was modest. The female endorser had a higher adjusted mean score compared with the male endorser in terms of participants’ perception of endorser gender fit for a social marketing campaign (Adj MFemale = 4.89, SE = .07, 95% CI [4.74, 5.03]; Adj MMale = 4.27, SE = .07, 95% CI [4.12, 4.41]). This provided evidence in support of H3.

When the participant and endorser’s gender were the same, perception of fit increased for female participants (Adj MMatch = 4.99, SE = .11, 95% CI [4.78, 5.20]) while, the reverse was true for males (Adj MMis-Match = 4.78, SE = .10, 95% CI [4.59, 4.98]). Please refer to . These results partially support H6.

Table 2. Adjusted means – gender interaction.

The scatter plot of the interaction between endorser gender and participants’ gender showed that both female and male participants perceived a female endorser as a better match for the sport and physical activity campaign. Please refer to .

Endorser’s career status fit

To investigate perceived career status fit, Picked-Point Analysis was used to compare groups while controlling for participants’ involvement in sport and physical activity. The analysis is based on establishing three levels of participants’ psychological involvement to enable assessment of the current and former athlete condition groups. Representing disparate levels of involvement, three points were chosen based on a procedure outlined by Huitema (Citation2011). The first picked point (PP1) was one standard deviation below the respondents’ mean score for involvement which represented a low level on the covariate (PP1 = 2.85). The second point was the mean score itself (PP2 = 4.41) which represented a moderate level of involvement. The third point (PP3) was one standard deviation above the mean to represent participants with a high level of involvement (PP3 = 5.97). A dummy variable (D) was then created to specify two athletic career statuses (i.e. current and former). Each picked point was subtracted from an individual’s involvement score (Centered PP). Then, each of those scores were multiplied with the dummy variable (D*Centered PP). Ultimately, three variables, (i.e. D, Centered PP and D*Centered PP) were included in a multiple regression to compare participants’ perception of endorser–campaign fit in terms of endorser career status at each picked point.

The regression equation was significant for the model (R2 = .05, F (3,388) = 6.88, p < .01) meaning that the independent variables explained a significant amount of the variance in the value of perceived fit. The results therefore indicated that career status was not a significant predictor of campaign–endorser fit at low levels of involvement in sport and physical activity, (β = −.17, t (388) = −1.05, p = .29). Similarly, in PP2 (moderate level of involvement in sport and physical activity) career status was not a significant predictor of perceived fit, (β = .07, t (388) = .66, p = .51). However, at higher levels of involvement in sport and physical activity (PP3), endorser career status was a significant predictor in the model, (β = .32, t (388) = 1.98, p = .048). Please refer to . In addition, the perceived fit at PP3 was higher for the former athlete than the current athlete, (β = .32, SE = .16). However, the reverse was true for PP1 (low involvement), as perceived fit for the current athlete endorser was higher than the former athlete endorser, (β = −.17, SE = .16). At PP2 (moderate involvement in sport and physical activity) participant perception of fit was almost equivalent between former and current athlete endorsers, (β = .07, SE = .11). Refer to .

Table 3. Adjusted means – career status fit.

These results provided partial support for H9. Overall, perception of campaign–endorser fit was significantly predicted by career status, but only at higher levels of psychological involvement in sport and physical activity. Those who were highly involved in sport and physical activity perceived a former athlete endorser to be a better fit for a social marketing campaign than a current athlete endorser.

To further explore gender matching and fit effects, a two-way between-subjects ANCOVA was performed to compare four groups featuring the possible endorser gender and participant gender combinations. ANCOVA revealed that participants’ psychological involvement significantly impacted perception of career status fit (F (1,387) = 16.17, p < .01, η2 = .04). Endorser gender was found to have an effect on perception of career status fit (F (1,387) = 6.91, p = .01, η2 = .02). The female endorser was perceived to fit better in the campaign in terms of their career status compared to the male endorser (Adj MFemale = 5.14, SE = .08, 95% CI [4.99, 5.30]; Adj MMale = 4.84, SE = .08, 95% CI [4.68, 5.00]). No significant effect was found on perception of career status fit between female and male participants (F (1,387) = .30, p = .59, η2 < .01). The interaction between endorser gender with participants’ gender was also insignificant in terms of perception of career status fit (F (1,387) = .10, p = .76, η2 < .01).

The adjusted means for all four groups after considering the effect of participants’ involvement in sport and physical activity were calculated. Refer to . Female participants reported the highest mean score when the campaign was endorsed by the female athlete either former or current (adj M = 5.19, SE = .12, 95% CI [4.96, 5.42]). Likewise, male participants had the highest mean score for the campaign endorsed by the female athlete either former or current (adj M = 5.10, SE = .11, 95% CI [4.88, 5.31]).

Table 4. Multiple regressions in three picked points.

below summarises the support for our nine hypotheses.

Table 5. Summary of hypotheses.

Discussion

This study explored the impact of endorser’s gender, endorser’s career status and participants’ gender on attitude, participation intention and perceived endorser–campaign fit (gender and career status) related to a social marketing campaign promoting sport and physical activity. The research responds to Schimelpfennig and Hunt’s (Citation2019) call for research covering combinations of endorser and brand/product combinations. The results suggested that endorser’s gender, career status and participants’ gender had no significant effect on attitude and intention related to the social marketing campaign. However, endorser gender significantly influenced participants’ perceptions of gender fit, and perceptions of career status fit. Either a current or former female athlete was perceived as a better fit for endorsing a social marketing campaign than a male athlete endorser. Furthermore, the career status of an endorser significantly impacted perception of career status fit, but only for participants who were highly involved in sport and physical activity. Although six of nine hypotheses were not supported, our collective knowledge of endorser characteristics in this context has advanced and future research will carry this further forward. The results have several important implications relevant to both practitioners and scholars.

Audience and endorser gender

With regards to two of the dependent variables – attitudes and intentions related to an endorsed social marketing campaign – males and females were similar in this research. The insignificance of audience gender on attitudes and intentions aligns with the work of Dix et al. (Citation2010), who concluded that the gender of consumers (17–25 years old) is not a major indicator of those two outcomes. Buksa and Mitsis (Citation2011) also found that the gender of young adults that comprise an endorsement audience does not play a critical role in subsequent positive word of mouth behaviours. However, other related studies suggested that either males (Peetz et al., Citation2004; Shuart, Citation2007) or females (Bush et al., Citation2004) respond more favourably to endorsement. Another research project, although not explicitly in the context of endorsement, indicated that young female consumers generally have a more positive attitude towards cause-related marketing than males (Cui, Trent, Sullivan, & Matiru, 2003). In those studies, gender effects might be due to the fact that one gender or another were generally more familiar with the endorsers (Peetz et al., Citation2004) and/or were more involved with the endorsed subject. Furthermore, audience response to celebrity endorsement could have been affected by socio-economic status because only high socio-economic status females are likely to be influenced by celebrity endorsements (Premeaux, Citation2009).

An athlete endorser’s gender does not significantly impact campaign-related attitude and intention. The findings were consistent with the research of Bailey and Cole (Citation2004) indicating that an endorser’s gender does not significantly affect consumers’ attitudes towards an advertisement nor that a consumer’s purchase intention is influenced by the gender of an athlete endorser. However, in their work some differences between female and male athlete endorsers were reported based on audience familiarity with the celebrity athletes.

The results revealed that the interaction between audience and endorser gender has no significant effect on attitude and intention. These findings were consistent with the work of Bhutada and Rollins (Citation2015) and health-related endorsements. In contrast with the current findings, other endorsement research reported an interaction between an endorser’s gender and audience gender in some cases. One study found that male consumers have higher intentions to buy a product endorsed by a male athlete (Peetz et al., Citation2004). However, the authors found that female consumers, may or may not be influenced by a female endorser. In another study, females are more likely to buy products endorsed by female athletes (Bush et al., Citation2005).

Our research does not bring absolute clarity to what is known about the role of gender among young adult endorsement audiences. There are mixed findings from studies related to endorsers’ gender and its interaction with the gender of the audience (Wolin, Citation2003). A generic sport and physical activity campaign does not necessarily need to be targeted at one gender or the other. Therefore, gender consideration for selecting endorsers may not always be necessary. All in all, more research is required related to gender.

Endorser–campaign fit

Although endorsers and audience gender was not a significant predictor of attitude and intention, perceived endorser–campaign fit in terms of gender (p < .01) and career status (p = .01) were significantly higher for the campaign endorsed by the female athlete than the male athlete. That is, participants perceived a female athlete endorser as a better match in terms of gender and career status for a social marketing campaign promoting sport and physical activity. Females are stereotypically expected to be caring and warm (Ebert et al., Citation2014). The warmth dimension captures traits related to perceived intent, including friendliness, helpfulness, sincerity, trustworthiness and morality (Zhang et al., Citation2020). Women are also stereotyped as being more communal than men (Eagly et al., Citation2020; Infanger & Sczesny, Citation2015). Although the effect of endorser’s gender on perception of fit was significant, the effect size was modest which means the gender of an endorser should be considered a subtle influence.

Despite this potentially actionable insight, caution is necessary because this finding may be due in part to participants’ lack of recognition of the endorsers in the experiment. An endorser’s familiarity/recognition can significantly impact the endorsement process (e.g. Behnoosh et al., Citation2017; Biswas et al., Citation2006). The two athlete endorsers in the mock advertisements were fictitious and unknown to participants. Unfamiliar female endorsers may be more effective than familiar female endorsers, while the reverse is true for male endorsers (Bailey & Cole, Citation2004). Unfamiliarity with the endorsers can mitigate the transfer of endorser’s qualities to the advertisement/endorsed product (McCracken, Citation1989), while the physical appearance of the endorser in the advertisement becomes paramount. Although the attractiveness of the female endorser was not manipulated by the researcher, she might be perceived as a better fit for the campaign due to this attribute compared to the male athlete.

Athlete career status

The findings of this study also revealed that endorser’s career status does not significantly affect participants’ attitudes (p = .19) and intentions (p = .93) for social marketing campaign in sport and physical activity. However, it does impact perception of endorser–campaign fit, but only for participants who are highly involved in sport and physical activity (p = .048). In this context, a former athlete can be more effective than a current athlete. Former athletes are featuring in advertisements more often compared to current athletes in part because former athletes as endorsers can reduce the risk of anti-social behaviours associated with current and possibly younger athletes (Stone et al., Citation2003). Former athletes can be seen as more trustworthy than current athletes for endorsing a social marketing campaign. So, consistent with the source credibility model (Hovland & Weiss, Citation1951; Pornpitakpan, Citation2004), social marketers should carefully consider endorser trustworthiness in campaigns featuring former athletes as endorsers and ensure they select endorsers that are well liked among the target market.

Involvement

Participants’ psychological involvement in sport and physical activity was measured as a covariate in the experiment phase of this study and was significant for all dependent variables (i.e. attitude, participation intention, perceived gender fit and perceived career status fit). This is consistent with previous research on the significant role of participant’s involvement on attitude and intention and subsequent behaviour change (e.g. Petty et al., Citation1983; Rice et al., Citation2012). Highly involved consumers respond more favourably and have stronger intention related to endorsed products and services (Bhutada et al., Citation2012). Celebrity athlete endorsers in this study were presented as experts, and early identification of an endorser’s expertise for those that are highly involved may help persuasion because the source’s expertise serves as a central cue for persuasion and attitude change (Homer & Kahle, Citation1990). So, communicating endorser expertise related to sport for a target market that is psychologically involved in sport is advisable for campaign managers.

Implications

The findings contribute to our understanding of how to select the most effective endorsers for social marketing campaigns aimed at promoting sport and physical activity in young people. The findings highlight that using former athletes is a more-than-viable strategy, and not just because of the likely lower cost. As noted, retired/former athletes may also have a lower propensity to be involved in scandal which can be very problematic (Ge & Humphreys, Citation2021; Lohneiss & Hill, Citation2014). In terms of gender, both male and female endorsers are equally likely to facilitate behaviour change in young adults. Therefore, the gender of the endorser, at least as it pertains to promoting sport and physical activity context, may not be the most crucial of decisions impacting a campaign’s effectiveness.

Theoretically, this study took the opportunity to extend the celebrity capital life cycle (Carrillat & Illicic, Citation2019). The model stipulates that the celebrity capital of well-known individuals fluctuates throughout different stages (i.e. acquisition, consolidation, downfall/decline and redemption/resurgence) over time. The abrupt downfall or slow decline stage of the celebrity capital life cycle refers to a decrease in media visibility. The model focuses on celebrities, not just sport celebrities. The model is not well suited to athletes given that most sporting careers have a clearly defined end to the activities which underpin their celebrity status. The careers of singers, actresses and models are not nearly as well defined as elite athletes. Retirement (in sport or otherwise) is a distinct phase where the celebrity is no longer able to directly generate any more celebrity capital from their traditional source. Within the context of the celebrity capital life cycle, our contribution has been to demonstrate that being a former athlete (i.e. retired) (and unable to produce any more celebrity capital from the traditional source), is not necessarily detrimental to the exercise of celebrity capital, and subsequently endorsement effectiveness when promoting sport and physical activity.

Limitations and future research

Several limitations specific to this study are worth noting. First, we relied upon a convenience sample of undergraduate students. Although convenient sampling is problematic, they are commonly used in experimental endorsement research (e.g. Chang et al., Citation2018; Lee & Bang, Citation2021).

Taking into consideration the complexity of consumer psychology, artificiality in experimental design does allow for the isolation and testing of variables (Webster & Kervin, Citation1971). Artificiality also helps to create consistencies that may not occur in real conditions (Henshel, Citation1980).

Although not without benefits, the use of fictitious endorsers and mock advertisements has the potential to limit the ecological validity of the study. All things equal, a fictitious endorser’s lack of familiarity will make them less trustworthy (Bailey & Cole, Citation2004). Also it may have been more difficult for participants to perceive sport expertise from a fictitious athlete endorser. For all these reasons, future research should replicate our design using authentic (i.e. non-fictitious) celebrity athlete endorsers.

The influence of athlete career status (i.e. current or former) on the endorsement outcomes in this research may overlap with the age of an athlete endorser. In this research, both current and former endorsers were relatively young which may have influenced perceptions of fit. Furthermore, the age at which an athlete retires differs across various sports. For example, equestrian Mary Hanna was 61 when she competed the 2016 Olympics and Phil Mickelson is still competing actively in professional golf at the age of 50. In contrast, in sports like American football or swimming, athletes commonly retire much younger. Therefore, it is important to isolate more carefully the “retirement” effect from the “age” effect. Moreover, in future research sport and physical activity contexts could be explored separately to isolate endorser career status effects.

The extent to which the endorsers and consumers’ race/ethnicity was not examined in this study remains an opportunity for future research. Future research should also consider the interaction effects between and amongst gender, race/ethnicity and socio-economic status for both endorsers and consumers.

Social marketing is more than just the promotional and endorsement dimension emphasised in this research. Future studies should incorporate all other aspects of the marketing mix.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Atkin, C., & Block, M. (1983). Effectiveness of celebrity endorsers. Journal of Advertising Research, 23(1), 57–61.

- Bailey, A. A., & Cole, C. A. (2004). The effects of multiple product endorsements by celebrities on consumer attitudes and intentions: An extension. In L. R. Kahle & C. Riley (Eds.), Sports marketing and the psychology of marketing communication (pp. 133–157). Erlbaum.

- Beaton, A. A., Funk, D. C., Ridinger, L., & Jordan, J. (2011). Sport involvement: A conceptual and empirical analysis. Sport Management Review, 14(2), 126–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2010.07.002

- Behnoosh, S., Naylor, M., & Dickson, G. (2017). Promoting sport and physical activity participation: the impact of endorser expertise and recognisability. Managing Sport and Leisure, 22(3), 214–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2018.1424024

- Bhutada, N. S., Menon, A. M., Deshpande, A. D., & Perri M. (2012). Impact of celebrity pitch in direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs. Health Marketing Quarterly, 29(1), 35–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/07359683.2012.652576

- Bhutada, N. S., & Rollins, B. L. (2015). Disease-specific direct-to-consumer advertising of pharmaceuticals: An examination of endorser type and gender effects on consumers’ attitudes and behaviors. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 11(6), 891–900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.02.003

- Biswas, D., Biswas, A., & Das, N. (2006). The differential effects of celebrity and expert endorsements on consumer risk perceptions. Journal of Advertising, 35(2), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2006.10639231

- Buksa, I., & Mitsis, A. (2011). Generation Y's athlete role model perceptions on PWOM behaviour. Young Consumers, 12(4), 337–347. https://doi.org/10.1108/17473611111185887

- Bush, A. J., Martin, C. A., & Bush, V. D. (2004). Sports celebrity influence on the behavioral intentions of Generation Y. Journal of Advertising Research, 44(1), 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021849904040206

- Bush, V. D., Bush, A. J., Clark, P., & Bush, R. P. (2005). Girl power and word-of-mouth behavior in the flourishing sports market. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 22(5), 257–264. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760510611680

- Carrillat, F. A., & Illicic, J. (2019). The celebrity capital life cycle: A framework for future research directions on celebrity endorsement. Journal of Advertising, 48(1), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2019.1579689

- Chang, Y., Ko, Y. J., & Carlson, B. D. (2018). Implicit and explicit affective evaluations of athlete brands: The associative evaluation-emotional appraisal-intention model of athlete endorsements. Journal of Sport Management, 32(6), 497–510. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2017-0271

- Charbonneau, J., & Garland, R. (2005). Talent, looks or brains? New Zealand advertising practitioners’ views on celebrity and athlete endorsers. Marketing Bulletin, 16(3), 1–10.

- Chen, C. Y., Lin, Y. H., & Hsiao, C. L. (2012). Celebrity endorsement for sporting events using classical conditioning. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 13(3), 209–219.

- D'Alonzo, K. T. (2004). The Johnson-Neyman procedure as an alternative to ANCOVA. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 26(7), 804–812. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945904266733

- Dickson, G., O'Reilly, N., & Walker, M. (2018). Conceptualizing the dissolution of a social marketing sponsorship. Journal of Global Sport Management, 3(2), 146–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2018.1441738

- Dix, S., Phau, I., & Pougnet, S. (2010). “Bend it like Beckham”: The influence of sports celebrities on young adult consumers. Young Consumers, 11(1), 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1108/17473611011025993

- Eagly, A. H., Nater, C., Miller, D. I., Kaufmann, M., & Sczesny, S. (2020). Gender stereotypes have changed: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of US public opinion polls from 1946 to 2018. American Psychologist, 75(3), 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000494

- Ebert, I. D., Steffens, M. C., & Kroth, A. (2014). Warm, but maybe not so competent? Contemporary implicit stereotypes of women and men in Germany. Sex Roles, 70(9), 359–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0369-5

- Erdogan, B. Z., Baker, M. J., & Tagg, S. (2001). Selecting celebrity endorsers: The practitioner’s perspective. Journal of Advertising Research, 41(3), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-41-3-39-48

- Fink, J. S., Parker, H. M., Cunningham, G. B., & Cuneen, J. (2012). Female athlete endorsers: Determinants of effectiveness. Sport Management Review, 15(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2011.01.003

- Fleck, N., Korchia, M., & Le Roy, I. (2012). Celebrities in advertising: Looking for congruence or likability? Psychology & Marketing, 29(9), 651–662. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20551

- Forsdike, K., & O’Sullivan, G. (2022). Interpersonal gendered violence against adult women participating in sport: A scoping review. Managing Sport and Leisure. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2022.2116089

- Frank, B., & Mitsumoto, S. (2021). An extended source attractiveness model: The advertising effectiveness of distinct athlete endorser attractiveness types and its contextual variation. European Sport Management Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2021.1963302

- Ge, Q., & Humphreys, B. R. (2021). Athlete off-field misconduct, sponsor reputation risk, and stock returns. European Sport Management Quarterly, 21(2), 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2020.1728778

- Halder, D., Pradhan, D., & Roy Chaudhuri, H. (2021). Forty-five years of celebrity credibility and endorsement literature: Review and learnings. Journal of Business Research, 125, 397–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.12.031

- Hassan, A., Biscaia, R., & Ross, S. (2021). Understanding athlete brand life cycle. Sport in Society, 24(2), 181–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2019.1624722

- Havitz, M. E., & Dimanche, F. (1990). Propositions for testing the involvement construct in recreational and tourism contexts. Leisure Sciences, 12(2), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490409009513099

- Henshel, R. L. (1980). The purposes of laboratory experimentation and the virtues of deliberate artificiality. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 16(5), 466–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(80)90052-9

- Homer, P. M., & Kahle, L. R. (1990). Source expertise, time of source identification, and involvement in persuasion: An elaborative processing perspective. Journal of Advertising, 19(1), 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1990.10673178

- Hovland, C. I., & Weiss, W. (1951). The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 15(4), 635–650. https://doi.org/10.1086/266350

- Huhman, M., Potter, L. D., Wong, F. L., Banspach, S. W., Duke, J. C., & Heitzler, C. D. (2005). Effects of a mass media campaign to increase physical activity among children: Year-1 results of the VERB campaign. Pediatrics, 116(2), e277–e284. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-0043

- Huitema, B. (2011). The analysis of covariance and alternatives: Statistical methods for experiments, quasi-experiments, and single-case studies (2nd ed.). Wiley.

- Infanger, M., & Sczesny, S. (2015). Communion-over-agency effects on advertising effectiveness. International Journal of Advertising, 34(2), 285–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2014.993794

- Jones, L., & Denison, J. (2019). Jogging not running: A narrative approach to exploring “exercise as leisure” after a life in elite football. Leisure Studies, 38(6), 831–844. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2019.1662831

- Kim, K., & Cheong, Y. (2011). The effects of athlete-endorsed advertising: The moderating role of the athlete-audience ethnicity match. Journal of Sport Management, 25(2), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.25.2.143

- Klaus, N., & Bailey, A. (2008). Celebrity endorsements: An examination of gender and consumers’ attitudes. American Journal of Business, 23(2), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1108/19355181200800010

- Koernig, S. K., & Boyd, T. C. (2009). To catch a tiger or let him go: The match-up effect and athlete endorsers for sport and non-sport brands. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 18(1), 25–37.

- Kotler, P., Roberto, N., & Lee, N. (2002). Social marketing: Improving the quality of life (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Kubler, K. (2023). Influencers and the attention economy: The meaning and management of attention on Instagram. Journal of Marketing Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2022.2157864

- Lee, C., & Bang, H. (2021). Managing athlete brands in transgressions: Influence of athlete performance level and the severity of the transgression on consumer perceptions of the athlete. Journal of Global Sport Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2021.1936590

- Leng, H. K., & Phua, Y. X. P. (2022). Athletes as role models during the COVID-19 pandemic. Managing Sport and Leisure, 27(1-2), 157–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1762330

- Lohneiss, A., & Hill, B. (2014). The impact of processing athlete transgressions on brand image and purchase intent. European Sport Management Quarterly, 14(2), 171–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2013.838282

- McCracken, G. (1989). Who is the celebrity endorser? Cultural foundations of the endorsement process. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(3), 310–321. https://doi.org/10.1086/209217

- McDonald, S. (2016). Elite athletes as charitable ambassadors: Risks associated with indiscretions. In P. D. Marshall, G. D’Cruz, S. McDonald, & K. Lee (Eds.), Contemporary publics: Shifting boundaries in new media, technology and culture (pp. 247–265). Palgrave Macmillan.

- McGuire, W. J. (1985). Attitudes and attitude change. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 233–346). Random House.

- Meyers-Levy, J., & Loken, B. (2015). Revisiting gender differences: What we know and what lies ahead. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25(1), 129–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2014.06.003

- Mikuláš, P., & Shelton, A. (2021). Product endorsement on Slovak TV: Generation Y’s recall of celebrity endorsements and brands. Celebrity Studies, 12(4), 618–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2020.1746678

- Mohan, M., Ferguson, J. L., & Huhmann, B. A. (2022). Endorser gender and age effects in B2B advertising. Journal of Business Research, 148, 60–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.04.050

- Muda, M., Musa, R., & Putit, L. (2012). Breaking through the clutter in media environment: How do celebrities help? Procedia. Social and Behavioral Sciences, 42, 374–382. https://doi.org/10.21744/irjmis.v9n1.2010

- Peetz, T. B., Parks, J. B., & Spencer, N. E. (2004). Sport heroes as sport product endorsers: The role of gender in the transfer of meaning process for selected undergraduate students. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 13(3), 141–150.

- Petty, R. E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Schumann, D. (1983). Central and peripheral routes to advertising effectiveness: The moderating role of involvement. Journal of Consumer Research, 10(2), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1086/208954

- Pornpitakpan, C. (2004). The persuasiveness of source credibility: A critical review of five decades’ evidence. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(2), 243–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02547.x

- Premeaux, S. R. (2009). The attitudes of middle class versus upper class male and female consumers regarding the effectiveness of celebrity endorsers. Journal of Promotion Management, 15(1-2), 2–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496490902854820

- Reid, H. (2017). Athletes as heroes and role models: An ancient model. Sport, Ethics and Philosophy, 11(1), 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/17511321.2016.1261931

- Rice, D. H., Kelting, K., & Lutz, R. J. (2012). Multiple endorsers and multiple endorsements: The influence of message repetition, source congruence and involvement on brand attitudes. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22(2), 249–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2011.06.002

- Scarapicchia, T. M. F., Sabiston, C. M. F., Brownrigg, M., Blackburn-Evans, A., Cressy, J., Robb, J., & Faulkner, G. E. J. (2015). MoveU? Assessing a social marketing campaign to promote physical activity. Journal of American College Health, 63(5), 299–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2015.1025074

- Schartel Dunn, S., & Nisbett, G. (2020). If Childish Gambino cares, I care: Celebrity endorsements and psychological reactance to social marketing messages. Social Marketing Quarterly, 26(2), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524500420917180

- Schimmelpfenning, C., & Hunt, J. B. (2019). Fifty years of celebrity endorser research: Support for a comprehensive celebrity endorsement strategy framework. Psychology & Marketing, 37(3), 488–505. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21315

- Shin, J. H., & Lee, J. W. (2021). Athlete brand image influence on the behavioral intentions of Generation Z. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 49(2). https://doi.org/10.2224/SBP.9533

- Shuart, J. (2007). Heroes in sport: Assessing celebrity endorser effectiveness. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 8(2), 11–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-08-02-2007-B004

- Stone, G., Joseph, M., & Jones, M. (2003). An exploratory study on the use of sports celebrities in advertising: A content analysis. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 12(2), 94–102.

- Till, B. D. (1998). Using celebrity endorsers effectively: Lessons from associative learning. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 7(5), 400–409. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610429810237718

- Till, B. D., & Busler, M. (2000). The match-up hypothesis: Physical attractiveness, expertise, and the role of fit on brand attitude, purchase intent and brand beliefs. Journal of Advertising, 29(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2000.10673613

- Till, B. D., Stanley, S. M., & Priluck, R. (2008). Classical conditioning and celebrity endorsers: An examination of belongingness and resistance to extinction. Psychology and Marketing, 25(2), 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20205

- Tzoumaka, E., Tsiotsou, R. H., & Siomkos, G. (2016). Delineating the role of endorser’s perceived qualities and consumer characteristics on celebrity endorsement effectiveness. Journal of Marketing Communications, 22(3), 307–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2014.894931

- Webster, M., & Kervin, J. B. (1971). Artificiality in experimental sociology. Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue Canadienne de Sociologie, 8(4), 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-618X.1971.tb02366.x

- Widrick, R. M., & Raskin, J. D. (2010). Age-related stigma and the golden section hypothesis. Aging & Mental Health, 14(4), 375–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860903167846

- Wolin, L. D. (2003). Gender issues in advertising: An oversight synthesis of research 1970–2002. Journal of Advertising Research, 43(1), 111–130. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-43-1-111-130

- World Health Organization. (2022). Global status report on physical activity 2022.

- Xu, Z., Islam, T., Liang, X., Akhtar, N., & Shahzad, M. (2021). I’m like you, and I like what you like’ sustainable food purchase influenced by vloggers: A moderated serial-mediation model. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 63, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102737

- Young, J. A., Symons, C. M., Pain, M. D., Harvey, J. T., Eime, R. M., Craike, M. J., & Payne, W. R. (2015). Role models of Australian female adolescents: A longitudinal study to inform programmes designed to increase physical activity and sport participation. European Physical Education Review, 21(4), 451–466. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X15579574

- Zhang, H., Zheng, X., & Zhang, X. (2020). Warmth effect in advertising: The effect of male endorsers’ warmth on brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising, 39(8), 1228–1251. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2020.1763089