ABSTRACT

Purpose/Rationale

This article identifies whether domestic and foreign owners of professional football clubs in England have a different propensity to gamble on sporting success by spending excessively on wages.

Design/Methodology/Approach

Data on wages, revenue and profit was extracted from the financial accounts of the football clubs in the Premier League and Football League from 2009–2010 to 2018–2019 to identify seasons in which the clubs gambled. In each case the ownership of the club was classified as either domestic or foreign. T-tests were performed to identify any statistically significant differences in incidents of gambling related to ownership type.

Findings

Foreign owners have provided more financial stability to football clubs in the Premier League, with less propensity to gamble for success, than domestic owners.

Practical Implications

The research shows the importance of understanding differences in ownership and the objectives of club owners at a league level for professional football clubs in England.

Research Contribution

The paper uses gambling as an indication of sporting ambition and provides evidence on the relative priorities of owner types to prioritise profits or sporting success.

Originality/Value

Neither the relationship between ownership and sporting ambition, nor between the ownership of clubs in different leagues, has previously been addressed.

Introduction

There is a wealth of literature that has looked at the financial performance of football clubs in England demonstrating that there has been a general tendency for clubs to overspend (e.g. Hamil & Walters, Citation2010: Rohde & Breuer, Citation2017; Szymanski & Smith, Citation1997). Within this literature, studies have sought to understand the incentives for overspending (e.g. Dietl et al., Citation2008); why football clubs are remarkably resilient (Kuper & Szymanski, Citation2009; Storm & Nielsen, Citation2012); the role that financial regulations play in attempting to curb spending (Evans et al., Citation2019; Citation2022); and also the link between financial performance and football club ownership (Rohde & Breuer, Citation2016a; Wilson et al., Citation2013). However, there is limited understanding on whether there are differences between domestic and foreign club ownership and sporting ambition. This article seeks to address this by focusing on whether domestic and foreign owners of professional football clubs in England have a different propensity to gamble on sporting success by spending excessively on wages.

The article builds on research that has looked at foreign ownership in football, a significant trend in English football from the late 1990s (Rohde & Breuer, Citation2018). Previous research has shown that foreign investors have tended to pay higher wages and thus generate lower profits compared with clubs that have more distributed ownership (Rohde & Breuer, Citation2016a). This suggests that foreign owners are more likely to financially gamble, defined as overspending on playing talent (Evans et al., Citation2022), a practice also known as “financial doping” that has led to accusations of competition distortion (Schubert & Hamil, Citation2018). Literature explicitly analysing financial gambling in football however is relatively recent (Evans et al., Citation2022) and as such, the relationship between ownership and sporting ambition as evidenced by the propensity to gamble has not yet been addressed. This article explicitly addresses this gap.

This article makes two main contributions to the literature on football club ownership and finance. First, it uses the concept of gambling, evidenced by excessive spend on wages, as an indication of sporting ambition. The assumption here is that excessive spending suggests that the owners are prioritising sporting performance given the strong correlation between player wages and league position (Szymanski & Smith, Citation1997). This has also been shown in research that has identified financial gambling as an almost necessary strategy to achieve promotion from the Championship to the Premier League (Evans et al., Citation2019). This adds to the long-standing debate regarding the objective functions of the owners of professional football clubs and provides evidence of the differing weight between their financial and sporting objectives. Second, as far as we are aware, this is the first article that assesses, or even looks at, the relationship between sporting ambition and different types of football club ownership (domestic and foreign). It does so for clubs in each of the top four leagues in England.

The article is structured as follows. It begins with an overview of academic literature on football club ownership, before summarising work on the relationship between football club financial performance and football club ownership. This provides the platform for this research that looks to build on existing literature by seeking to identify whether domestic and foreign owners have a different propensity to gamble. The methods are then set out, detailing how we define gambling, building on the work of Evans et al. (Citation2022), and explaining the data set used in this research and how we analysed this. The results are presented in three sections: firstly, we look at how often football clubs gambled and break this down by domestic and foreign-owned clubs. We then look at the overall results across all four leagues that sets out the propensity to gamble, before we break this down by league and highlight whether there are any differences by league. Following this, we discuss potential explanations that help to understand the results before concluding.

Ownership models and owner objectives

This research develops the academic literature relating to the ownership, and financial and sporting objectives of owners of clubs in English professional football. For the majority of the twentieth century, once football clubs were able to be constituted as private companies with limited liability, individual owners, more often than not businessmen local to the regional area, were the ultimate owners of football clubs (Buraimo et al., Citation2006). This began to change, however, in the 1980s and in particular, the 1990s, which coincided with a commercial boom for the sector at the same time that the wider societal trends around financialisation (the growth of stock markets and the focus on shareholder value, e.g. Lazonick & O’Sullivan, Citation2000) were occurring. Many existing football club owners saw the opportunity to list on the stock market and make a personal fortune through the selling of their shareholding, leading many football clubs in England to become public limited companies (Morrow, Citation1999).

The listing of football clubs on the stock market led to debates about the motives of football club ownership. There is a long history of sports economics literature on this particular topic. In the US, where professional sports clubs have long been viewed as businesses, the early literature assumed that the objective of owners would be to maximise profits (Quirk & Fort, Citation1992). Whilst this may have been a realistic assumption for clubs in American sports leagues, where much of the initial interest from an academic perspective focused, it was apparent that it was not realistic more generally and particularly for clubs in professional football (“soccer”) leagues elsewhere where owners were giving weight to sporting success (e.g. Cairns et al., Citation1986; Garcia-del-Barrio & Szymanski, Citation2009; Késenne, Citation2006; Rascher, Citation1997; Sloane, Citation1971; Szymanski & Smith, Citation1997; Zimbalist, Citation2003). For football clubs in England this was, in part, due to the historic approach of the governing body which introduced rules, such as Rule 34 which imposed a maximum permissible dividend and barred payment to the club’s directors, to act as a bulwark against people coming into football looking just to make money for themselves (Conn, Citation1997). This rule was abolished in 1998 and that opened up opportunities to make money. However, the rule already been side-stepped by clubs, beginning with Tottenham Hotspur, when they floated on the stock market in 1983, by setting up a holding company.

The more recent move in English football for foreign private investment has been argued to be the most important trend in ownership (Rohde & Breuer, Citation2018, p. 19) football clubs from the Premier League and the Championship were bought by foreign private majority investors between 2006 and 2012. It has been argued that the motives for foreign investors were due to the increasing internationalisation of the game (Rohde & Breuer, Citation2017) and the growing commercial focus of the game (Walters & Hamil, Citation2010). However, it must also be recognised that the preferences of owners may not be aligned with those who are responsible for implementing them. In the case of football clubs, there is a form of principal-agent moral hazard whereby the manager of the team may have the opportunity and personal incentive to give greater weight to winning relative to the financial objectives of owners (Vöpel, Citation2011). Consequently, observed outcomes actually may be a hybrid of the owners’ objectives and those of the club’s management.

The growth in foreign ownership has also coincided with the more recent development which has been the growth in multi-club ownership where a number of football clubs are owned by the same individual or investment fund (UEFA, Citation2022). UEFA’s recent Club Licensing Benchmarking report indicates this has been driven predominantly across Europe, and in the main by US-based investors and private equity investment. While multi-club ownership has been around for some time (for example, when ENIC bought Tottenham Hotspur in 2000, they also were part owners of five other European football clubs), the recent expansion of this model is more evident. For example, there are 14 clubs in England that are part of a multi-club ownership (UEFA, Citation2022). This serves to highlight that football club ownership, and motives for ownership, are therefore an ever changing and evolving landscape.

Initial studies on football club ownership were descriptive in nature, seeking to understand the different types of ownership models (e.g. Walters & Hamil, Citation2010) and sought to better understand why there were changes in ownership type. There was often a focus on understanding different types of ownership models in place across various European countries. For example, the German model of ownership, whereby supporters retain a 50 + 1% share as a way to protect supporter interests and maintain financial and competitive balance in the league, is one notable form of ownership that has received academic attention (Hamil, Citation2019). However recent research from a sample of 47 German football clubs over a 30-year period has shown that there has been increasing financial and competitive imbalance and inequality since this rule was introduced, in direct contrast to the rationale for its implementation (Budzinski & Kunz-Kaltenhäuser, Citation2020). Indeed, despite evidence for support of the rule due to the democratic and participatory benefits (Bauers et al., Citation2020), case study research has also highlighted concerns that this model has constrained the ability of clubs to compete on the field of play (Ward & Hines, Citation2018).

Recent studies on ownership have also become more sophisticated, moving beyond a descriptive understanding and seeking to link ownership to financial performance. These studies have emerged during a period where financial sustainability has become a key issue of study (alongside ownership). For example, Wilson et al. (Citation2013) looked at the financial performance of football clubs and identified that clubs owned by private investors performed worse (in financial terms) than those clubs listed on a stock market. Further research suggests that the reason underpinning this is that private majority investors were more likely to increase investment in the team to improve sporting performance and thus increase debts, losses and reduce overall profitability (e.g. Acero et al., Citation2017; Franck, Citation2010; Rohde & Breuer, Citation2016a, Citation2016b). The utility function for a club owner could also be maximised under an inter temporal budget function to adjust the weight between winning and profit according to the opportunities in the environment (Storm & Nielsen, Citation2015; Terrien et al. Citation2017). The priority of club owners in their sporting and financial situations is addressed by Carlsson-Wall et al. (Citation2016). One of the five situations they identify is where a club senses the possibility to become champion and, as in this research, the sports logic is prioritised over the business logic.

There have also been studies that have sought to see whether there are differences in financial performance by clubs that are in foreign ownership. Nauright and Ramfjord (Citation2010) argued that objective functions pursued depend on their origin. Rohde and Breuer (Citation2016a) looked at a sample of English Premier League clubs and found that clubs owned by private majority investors and, particularly those owned by foreign owners, paid higher wages and generated lower profits than clubs with distributed ownership. This aligned with earlier research that found that football clubs owned by foreign private investors achieved better sporting performance than those listed on stock markets due to increased team investment (Wilson et al., Citation2013). However, the idea that foreign ownership has led to less financially efficient performance is also contested. It has been argued that some types of foreign investor, for example US-based investors that have a long history in profit maximisation through sports team ownership (Nauright & Ramfjord, Citation2010) may in fact lead to a focus on new and innovative revenue streams that improve financial efficiency (Rohde & Breuer, Citation2018).

It is evident that research has shown a lack of clarity on the relationship between ownership and financial performance. What is evident however, is that the changes in ownership have, in the UK in particular, been a catalyst for increasing government and policy focus on the governance and regulation of the industry. In the late 1990s, the work undertaken by the Football Task Force (Citation1999), initiated due to the commercial growth in the game, highlighted ownership as an issue that needed to be addressed. Similarly, the Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) “Football Governance” report in 2011 noted that the football authorities were “behind the curve” on ownership issues, allowing poor business practices, a lack of transparency, debt levels to rise, and insolvencies to occur (DCMS, Citation2011, p. 73). The notion of introducing and improving regulation was central to this policy work with the emphasis on having in place robust criteria that prospective owners and directors meet before they are allowed to own or run a club. The issue of the regulation of football club ownership arose due to concerns around the financial sustainability of football clubs: a situation that was also prevalent across Europe more broadly. As Acero et al. (Citation2017) note, levels of aggregated debt across European football clubs increased significantly, with many clubs on the verge of bankruptcy. This was a key factor in UEFA introducing financial fair play regulations to try to improve financial performance but also to minimise the ability of owners achieving sporting success through increased team investment that gave a sporting advantage.

The aforementioned body of research has sought to analyse the relationship between football club financial performance and football club ownership. It has shown that football clubs have demonstrated a tendency to overspend and identified that the issue of ownership, and in particular, foreign ownership, can be a factor in this (Rohde & Breuer, Citation2017). A more recent focus within the literature on football finances has been to try to quantify the extent to which football clubs gamble financially by overspending on playing talent (Evans et al., Citation2022). Evans et al. (Citation2022) found that over a period of 15 seasons in the Championship, gambling was a prevalent strategy used by football clubs despite the fact that financial regulations were introduced in the period to limit financial losses made by clubs. They concluded that gambling was a rational strategy in the non-economic sense to achieve promotion. However, what is not clear at this stage, is whether ownership type has any bearing on whether an owner is more or less likely to gamble.

This research takes this as a stepping-off point. It seeks to build on research on foreign ownership in football, linking this with recent research on financial gambling, and seeks to identify whether domestic and foreign owners have a different propensity to gamble. In line with previous research that has identified foreign ownership results in team investment, and reduced financial efficiency (e.g. Franck, Citation2010; Rohde & Breuer, Citation2016a), this article seeks to test whether foreign owners are more or less likely to demonstrate a propensity to gamble by spending excessively on wages to achieve improved sporting performance.

Methods

Approach

The research has a positive theoretical perspective and takes an inductive approach to build a theory with regard to the ownership of football clubs and sporting ambition indicated by the propensity of each type of owner to gamble on sporting success by spending excessively on wages. Student’s t-tests are used to identify any statistically significant differences in the propensity to gable by domestic and foreign owners.

Following Evans et al. (Citation2022) owners were considered to have gambled if, in relation to the previous season:

Wage spend increased; and

Wage spend increased by more than revenue increased; and

Wage spend increased by more than profit before tax increased.

The assumptions used in this research are that in addition to clubs that reduce their spending on wages, the clubs that increase wage spend are not gambling if the increase in spending on wages was supported by an increase in revenue or an increase in profit. An increase in revenue, for example through additional commercial income, enables a club to spend more on wages. An increase in profit, for example through the sale of players or from exceptional income that might come from the sale of the stadium or a reduction in operating costs, can also be used to spend more on wages. In both these cases, the assumption is that the football club is not gambling. The results show the instances of gambling by each owner type in each league and overall. In each case the significance levels (p-values) are reported for tests of whether the propensity of domestic owners to gamble is greater to, equal to or less than that of foreign owners.

Data

There is a hierarchy of four leagues of professional football in England. The top tier league is called the English Premier League (EPL) and is managed by the Premier League. The other three leagues are managed by the English Football League (EFL) and throughout the study period were called, in descending order, the Championship, League One and League Two. The study covered clubs in all four of these leagues in the ten seasons from 2009–2010 to 2018–2019.

The primary data source for the study was the financial statements and related notes to the accounts filed at Companies House by the clubs for the corresponding seasons. Following the approach adopted by Deloitte,Footnote1 the accounts used were the legal entity registered in the United Kingdom which was at, or close to, the “top” of the ownership structure in respect of each club. Where the accounts identified that the ultimate owner was a company it was classified as “domestic” if it was registered in the UK and all other registered locations were classified as “foreign”. Where the accounts identified individuals as the controlling owner(s) or they did not identify a controlling party the owner(s) their nationality was identified from the confirmation statement of directors and shareholders filed at Companies House.

Sample

A total of 92 clubs participated in these four leagues in each of the seasons. This produced a maximum potential data set from 920 company accounts. The definition of “gamblers” created a requirement for data for each of these variables for each club in both the current and previous season. The clubs that were either promoted or relegated into the league each season were removed on the assumption that the comparison of data between season in different leagues was not valid. Each season three teams were relegated from the Premier League and the Championship and replaced for the following season by the corresponding number of teams promoted from the league below. Similarly, four teams were relegated from League One and two teams are relegated from League Two, with replacements coming from the league below.

From a club perspective, in addition to the 92 clubs in the top four leagues in 2009–2010 (the earliest in the study) 11 other clubs joined League Two in the study period. When the promoted and relegated club seasons were removed and the club seasons lacking the required data were also removed it left 80 clubs included in the study. Of these, 38 had a change in ownership in the study period and of those five began in domestic ownership and changed to foreign ownership and two began in foreign ownership and changed to domestic ownership. Unlike the clubs promoted from League Two and above leagues, the clubs replacing the two clubs relegated from League Two were not in the study leagues in their promotion season and are therefore excluded in their first season in the study period. This means that 70 teams in the top four leagues remain in the same league for the following season (with 17, 18, 17 and 18 from each of the leagues in descending hierarchal order) and there is a maximum potential of 700 company accounts for “on-going” clubs in the study period. However, the data required to assess whether the owners gambled was not available for 189 of those club seasons. Consequently there are 511 club seasons in the study (with 169, 175, 113 and 54 from each of the leagues in descending hierarchal order).

Data analysis

The data for each club season was coded for analysis with the values of either 1 or 0 to denote whether the ownership was domestic of foreign and either 1 or 0 to denote whether or not the owner gambled. Student t-tests were used to assess whether there was a significant difference between the propensity of domestic and foreign owners to gamble. The null hypothesis that there was no difference was tested against the alternative hypothesis that either:

the propensity of domestic owners to gamble was greater than that of foreign owners

the propensity of domestic owners to gamble was equal to that of foreign owners

the propensity of domestic owners to gamble was less than that of foreign owners

Each test was applied to all of the club seasons in the study and separately to the club seasons in each of the four leagues in the study. It was assumed that the comparative samples had unequal variances.

Results

Propensity to gamble: results across all leagues

The data was analysed to see whether there were any statistical differences between domestic owners and foreign owners in regard to propensity to gamble. Initially, we looked at the entire sample across all four leagues. Summary data, showing the propensity to gamble and results of the t-tests of the null hypothesis, revealed that there was no difference between owner types with regard to whether or not they gambled. summarises the results of the analyses for all 511 club seasons of 80 clubs over the 10 years of the study period. The column headed “Gambling” shows the propensity to gamble and “n” gives the number of observations in the test. The results show that clubs in domestic ownership gambled 38 per cent of the time compared to 39 per cent of the time for clubs in foreign ownership. The results from the t-tests show that the null hypothesis of no difference between the domestic and foreign owners cannot be rejected and suggests that there was no significant difference in the propensity to gamble between domestic and foreign owners overall across all four leagues.

Table 1. Propensity to gamble, all clubs.

Propensity to gamble: results for each league

We also analysed the results for each league. summarises the results of the analyses for clubs in each of the four leagues over the 10 years of the study period. First, it can be seen that the propensity for owners to gamble is higher in the Premier League and Championship, at c.43 per cent, than in Leagues One and Two, at c.30 per cent.

Table 2. Propensity to gamble, by league.

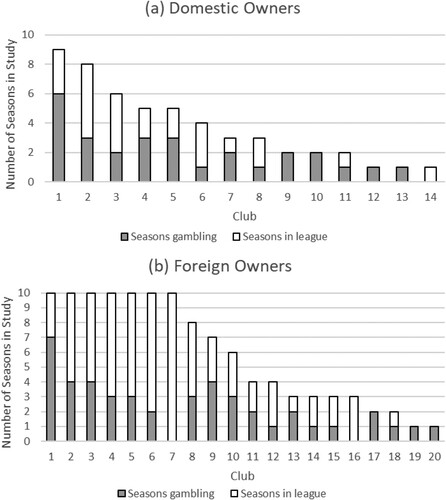

Second, the results from the t-tests showed that there was no statistically significant difference between domestic and foreign owners in all three leagues of the EFL. However, the results show that in the Premier League the propensity to gamble was statistically significantly higher (at the 5% level) for domestic owners than for foreign owners in the Premier League. Closer examination of the data for the Premier League (see ) found that the relatively low propensity to gamble by foreign owners was largely attributable to the number of seasons when six of the seven clubs in foreign ownership that were in the Premier League in all ten seasons of the study period did not gamble. In this sense, a handful of foreign owners, that demonstrate less propensity to gamble, have distorted the picture to some extent.

Discussion

When we look at the results for the entire sample of clubs across all leagues, it is evident that there was no statistically significant difference between ownership types when it comes to propensity to gamble. This is interesting given that previous research has shown that foreign investors tend to increase spending on player wages to ensure sporting success at the expense of lower profits (e.g. Rohde & Breuer, Citation2016a). One could assume, therefore, that foreign owners would in fact have a higher propensity than domestic owners to gamble on sporting success by spending excessively on wages. Our results for the entire sample of clubs across the Premier League and the three leagues in the EFL suggest that this is not the case. This, in and of itself, is an interesting finding and adds to the literature around football club ownership.

When we break down the results by league, however, the results demonstrate there are differences between foreign owners and domestic owners in the Premier League in particular. Clubs under domestic ownership gambled 54 per cent of the time compared to 38 per cent of the time for foreign ownership. This is interesting in that again, it could be expected that the influx of foreign owners into the Premier League, evidenced by the fact that 117 club seasons in the ten-year period were under foreign ownership compared to 52 club seasons in domestic ownership, would result in a greater propensity to gamble if foreign investors have tended to increase spending to achieve sporting success (e.g. Rohde & Breuer, Citation2016a, Citation2016b). However, this was not the case in the Premier League.

Looking in more detail into the results of the research within the Premier League, we can see that six clubs in the Premier League in all of the study seasons with a relatively low propensity to gamble were the larger clubs by revenue generation (). One explanation could be that these clubs have less of a need to gamble financially because they are already able to afford higher player salaries that keep them competitive due to the revenue they generate. This could explain why the rest of the clubs in the Premier League, including those owned by domestic owners, are more likely to gamble on player wages to achieve sporting success or to avoid sporting failure in the form of relegation.

One explanation to help understand why they are less likely to gamble could be the motivations of the owners. Interestingly, three of these six clubs had US owners but between them only won two of the ten titles in the study period. They could be investing in these particular teams with a strategy to give more priority to the profitability of the business than to sporting success, perhaps in the belief that they will still achieve an acceptable level of sporting success as the internally generated resources provide a degree of protection against sporting decline. This would align with the arguments made by Nauright and Ramfjord (Citation2010) and Rohde and Breuer (Citation2018), that some types of foreign investor may focus more on profit maximisation through sports team ownership that leads them to target new revenue streams. Arguably we have seen this at a number of clubs in the Premier League (and particularly those in foreign ownership) in two ways. First, there has been an increased focus on growing commercial revenues. For example, since Kroenke Sports and Entertainment took full ownership of Arsenal Football Club in 2018, commercial revenue has grown from £117.2 m per year in 2017 (28 per cent of income), to £142 m in 2022 (38 per cent of income). Second, the initial support for the European Super League was largely due to this being a potentially new revenue stream for those clubs involved. The Premier League clubs that had signed up for this were the larger clubs under foreign ownership. Whilst supporter and political outcry led to this proposal being (temporarily) abandoned, it is clear that the creation of a European Super League is a logical move, if a club has an owner for whom the priority is to increase profitability, towards a new form of competition that would have generated a new, significant, source of revenue and more consistent profitability.

It could also be argued that these results are also relevant for the incoming independent regulator for football (IREF) in regard to increasing the financial sustainability of football clubs. The recent sporting sanction placed on Everton Football Club (a club under foreign ownership) for breaching the Premier League’s Profitability and Sustainability rules, that allow clubs to make a cumulative loss of £105m over a three-year period, is a case in point (Premier League, Citation2023). Everton, like the majority of clubs in the Premier League, are not able to generate the revenues of the larger clubs and perhaps fearing relegation (they finished in 16th position in the 2021/22 season), and having committed to expenditure on a new stadium, spent more, including on players, than was permitted by the rules. It has been reported that the club received forewarning from the Premier League that they were nearing their spending limit (Independent, Citation2023). Evidently this was not a sufficient deterrent to stop Everton spending on new players in 2021/22 to comply with the rules and they avoided relegation in that season and the significant loss of revenue that would have resulted. This suggests that an independent regulator needs to have the ability to impose penalties that are sufficient to deter breaches of the financial regulations. An important point arising from this research is that whilst you cannot regulate owner motives, what is needed are financial regulations from an independent body that will regulate owner behaviour, be adhered to, and that will act as a sufficient deterrent to stop football clubs overspending.

When we look at the Championship, although the propensity for owners to gamble was similar to the Premier League, it is a different picture with regard to the propensities to gamble for domestic and foreign owners. In the ten-year period that we analysed, foreign ownership accounted for 94 club seasons and domestic ownership for 81 club seasons. This is understandable if potential domestic owners lack the financial resources of potential foreign owners as it requires less investment to buy a Championship club compared to a Premier league club and there exists the opportunity to achieve promotion into the Premier League which brings greater financial rewards. However, the results show that there was no significant difference in propensity to gamble between foreign owners in the Championship and domestic owners.

What was evident however was that owners of clubs in the Championship had a higher propensity to gamble than owners in either League One and League Two, indicating greater potential financial unsustainability. This is unsurprising given that previous research has argued that clubs in the Championship are gambling on player wages and that this is endemic and an almost necessary (but not sufficient) strategy to gain promotion (Evans et al., Citation2022). As argued above, this also suggests the need for the independent regulator to bring in more significant financial regulation to protect clubs and the integrity of the sporting competition in the Championship.

The propensity for owners to gamble in Leagues One and Two was clearly less than in the Premier League and the Championship. This may reflect the reduced financial incentive for sporting success that promotion from the Championship provides. However, the results show that there was no statistically significant difference between the propensity to gamble of domestic and foreign owners in either of the two lower leagues in the EFL, which suggests little difference in the motivation of domestic and foreign owners of clubs in these leagues. Nevertheless, there were far fewer cases of clubs in foreign ownership in the lower leagues so it would appear that clubs in Leagues One and League Two are less attractive an investment for foreign owners – something that does not come as a surprise as previous research has argued that football club ownership, particularly in the Premier League, is attractive to foreign investors who are able to capitalise on what is essentially seen as a “trophy asset” (Walters & Hamil, Citation2010). This may be changing however to some extent, with a more recent influx of foreign investors investing in lower league clubs (Wrexham and Carlisle for example). This is something that could be worthy of further research looking at the motivations for foreign investors to buy into lower league clubs.

Conclusion, limitations and future research perspectives

This article has drawn on data on wages, revenue and profit from the financial accounts of the clubs in the Premier League and Football League over a ten-year period (seasons 2009–2010 to 2018–2019) to identify seasons in which the clubs could be said to have financially gambled. It has then sought to identify any statistically significant differences in incidents of gambling related to ownership type that has allowed us to see whether there is a difference between domestic and foreign owners and their propensity to gamble on sporting success by spending excessively on wages.

This article makes two main contributions to the literature on football club ownership and finance. First, it introduces the concept of gambling, evidenced by excessive spend on wages, as an indication of sporting ambition. Despite not explicitly focusing on the win versus profit maximisation debate in existing literature, the focus on sporting ambition through propensity to financially gamble adds a potential new dimension to this, adding to the debate regarding the objective functions of the owners of professional football clubs. It is used to provide evidence of the differing weight between their financial and sporting objectives. Second, the concept is applied to analyse differences in sporting objectives between types of owner in each of the top four leagues in England. As far as we are aware, this is the first article that looks at the relationship between different types of football club ownership (domestic and foreign) and sporting ambition. The results show that domestic owners of clubs in the Premier League had a significantly greater propensity to gamble on achieving sporting success by spending excessively on wages than foreign owners. This contrasts with previous research that found the opposite result (Rohde & Breuer, Citation2016a, Citation2016b).

The difference in the Premier League was found to be largely attributable to six clubs with foreign ownership which gambled relatively infrequently. Three of these clubs had American ownership which suggests that they took an interest in these clubs more with an objective of financial gain than the achievement of sporting success. Whilst this may benefit the financial sustainability of the clubs, with less external financial support required, it is unlikely to be welcomed by fans who want to see their club achieve sporting success. Owners of clubs in the Championship had a higher propensity to gamble than owners in either of the two lower leagues indicating greater potential financial unsustainability. There were relatively fewer clubs with foreign ownership in Leagues One and Two but there was no statistically significant difference between the propensity to gamble of domestic and foreign owners in any of the three EFL leagues. Finally, the article also highlights the need for effective financial regulation to mitigate against the effects of gambling by both domestic and foreign owners to spend excessively on player wages to gain a sporting advantage.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 This approach is used by Deloitte for their Annual Review of Football Finance

References

- Acero, I., Serrano, R., & Dimitropoulos, P. (2017). Ownership structure and financial performance in European football. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 17(3), 511–523. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-07-2016-0146

- Bauers, S. B., Lammert, J., Faix, A., & Hovemann, G. (2020). Club members in German professional football and their attitude towards the ‘50 + 1 Rule’ – a stakeholder-oriented analysis. Soccer & Society, 21(3), 274–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2019.1597717

- Budzinski, O., & Kunz-Kaltenhäuser, P. (2020). Promoting or restricting competition? – The 50plus1-Rule in German Football. Ilmenau Economics Discussion Papers, 26(141).

- Buraimo, B., Simmons, R., & Syzmanski, S. (2006). English football. Journal of Sports Economics, 7(1), 29–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002505282911

- Cairns, J. A., Jennett, N., & Sloane, P. J. (1986). The economics of professional team sports: A survey of theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Studies, 13(1), 3–80. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb002618

- Carlsson-Wall, M., Kraus, K., & Messner, M. (2016). Performance measurement systems and the enactment of different institutional logics: Insights from a football organization. Management Accounting Research, 32, 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2016.01.006

- Conn, D. (1997). The football business: The modern football classic. Mainstream Publishing.

- Department for Culture Media and Sport. (2011). Football governance: Response to the Culture, Media and Sport Committee Inquiry. (HC792-1).

- Dietl, H., Franck, E., & Lang, M. (2008). Overinvestment in team sports leagues: A contest theory model. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 55(3), 353–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9485.2008.00457.x

- Evans, R., Walters, G., & Hamil, S. (2022). Gambling in professional sport: The enabling role of “regulatory legitimacy”. Corporate Governance, 22(5), 1078–1093. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-07-2021-0251

- Evans, R., Walters, G., & Tacon, R. (2019). Assessing the effectiveness of financial regulation in the English Football League – ‘The dog that didn’t bark’. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 32(7), 1876–1897. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-12-2017-3288

- Football Task Force. (1999). Football: Commercial issues: A submission by the Football Task Force to the Minister of Sport.

- Franck, E. (2010). Private firm, public corporation or member‘s association governance structures in European Football. International Journal of Sport Finance, 5(2), 108–127.

- Garcia-del-Barrio, P., & Szymanski, S. (2009). Goal! Profit maximisation versus win maximisation in soccer. Review of Industrial Organisation, 34(1), 45–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-009-9203-6

- Hamil, S. (2019). Not for sale: The development of and resistance to fan-owned sports clubs. In J. in Maguire, M. Falcous, & K. Liston (Eds.), The business and culture of sports: Society, politics, economy, environment (pp. 193–209). USA.

- Hamil, S., & Walters, G. (2010). Financial performance in English professional football: ‘An inconvenient truth’. Soccer & Society, 11(4), 354–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660971003780214

- Independent. (2023). Everton rocked by points deduction as Premier League takes stand over financial fair play. https://www.independent.co.uk/sport/football/everton-points-deduction-premier-league-ffp-financial-fair-play-b2449122.html [Accessed: 11 December 2023]

- Késenne, S. (2006). The win maximisation model reconsidered. Journal of Sports Economics, 7(5), 981–1006.

- Kuper, S., & Szymanski, S. (2009). Why England lose & other curious football phenomena explained. Harper Sport.

- Lazonick, W., & O’Sullivan, M. (2000). Maximizing shareholder value: A new ideology for corporate governance. Economy and Society, 29(1), 13–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/030851400360541

- Morrow, S. (1999). The new business of football: Accountability and finance in football. MacMillan Business.

- Nauright, J., & Ramfjord, J. (2010). Who owns England's game? American professional sporting influences and foreign ownership in the Premier League. Soccer & Society, 11(4), 428–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660971003780321

- Premier League. (2023). Everton FC deducted 10 points by independent Commission. https://www.premierleague.com/news/3788486 [Accessed 14th December 2023]

- Quirk, J., & Fort, R. D. (1992). Pay Dirt, The Business of Professional Team Sports. Princeton University Press.

- Rascher, D. (1997). A model of a professional sports league. In W. Hendricks (Ed.), Advances in the economics of sport (Vol. 2, pp. 27–76). JAI Press.

- Rohde, M., & Breuer, C. (2016a). The Financial impact of foreign private investors on team investments and profits in professional football: Empirical evidence from the Premier League. Applied Economics and Finance, 3(2), 243–255. https://doi.org/10.11114/aef.v3i2.1366

- Rohde, M., & Breuer, C. (2016b). Europe’s elite football: Financial growth, sporting success, transfer investment, and private majority investors. International Journal of Financial Studies, 4(2), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs4020012

- Rohde, M., & Breuer, C. (2017). The market for football club investors: A review of theory and empirical evidence from professional European football. European Sport Management Quarterly, 17(3), 265–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2017.1279203

- Rohde, M., & Breuer, C. (2018). Competing by investments or efficiency? Exploring financial and sporting efficiency of club ownership structures in European football. Sport Management Review, 21(5), 563–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.01.001

- Schubert, M., & Hamil, S. (2018). Financial doping and financial fair play in European Club football competitions. In M. Breuer & D. Forrest (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook on the economics of manipulation in sport (pp. 135–157). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sloane, P. (1971). The economics of professional football: The football club as a utility maximiser. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 18(June), 121–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9485.1971.tb00979.x

- Storm, R. K., & Nielsen, K. (2012). Soft budget constraints in professional football. European Sport Management Quarterly, 12(2), 183–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2012.670660

- Storm, R. K., & Nielsen, K. (2015). Soft budget constraints in European and US leagues: Similarities and differences. In W. Andreff (Ed.), Disequilibrium sports economics, competitive imbalance and budget constraints (pp. 151–174). Elgar.

- Szymanski, S., & Smith, R. (1997). The English Football Industry: Profit, performance and industrial structure. International Review of Applied Economics, 11(1), 135–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692179700000008

- Terrien, M., Scelles, N., Morrow, S., Maltese, L., & Durand, C. (2017). The win/profit maximization debate: strategic adaptation as the answer? Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 7(2), 121–140. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-10-2016-0064

- UEFA. (2022). The European club footballing landscape: Club licensing benchmark report, UEFA: Nyon.

- Vöpel, H. (2011). Do we really need Financial Fair Play in European club football? An economic analysis. CESifo DICE Report, 9(3), 54–60.

- Walters, G., & Hamil, S. (2010). Ownership and governance. In S. Hamil & S. Chadwick (Eds.), Managing football – an international perspective (pp. 17–36). Elsevier.

- Ward, S. J., & Hines, A. (2018). The demise of the members’ association ownership model in German professional football. Managing Sport and Leisure, 22(5), 358–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2018.1451359

- Wilson, R., Plumley, D., & Ramchandani, G. (2013). The relationship between ownership structure and club performance in the English Premier League. Sport Business and Management, An International Journal, 3(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1108/20426781311316889

- Zimbalist, A. (2003). Sport as business. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 19(4), 503–511. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/19.4.503