ABSTRACT

Flexible learning increases access to higher education, particularly for traditionally undeserved students. First-time entrants, who may lack the cultural capital to be successful, may also be more likely to participate in flexible learning than traditional students, and particularly in online and blended courses. We posit that success for all students enrolling in flexible forms of learning can be achieved through course design and responsive pedagogies. For these efforts to be successful, competency frameworks must be developed, and initial and ongoing training provided for teaching staff. This paper discusses a theory-based and practice-informed framework for the scalable expansion of flexible learning, which in our case, encompassed online learning, blended learning, competency-based education, and open educational resources. We provide a context for the framework, introduce the framework, discuss the steps for developing and implementing it, and share initial findings and implications.

Flexible learning is a critical strategy for increasing access to higher education, particularly as worldwide enrollments are expected to double by 2025 (Maslen, Citation2012). It involves choice in ‘how, what, when and where [individuals] learn: the pace, place and mode of delivery’ (Higher Education Academy [HEA], Citation2015, para 1).” Flexible learning is a comprehensive approach that enables institutions to be ‘more responsive and relevant’ (Beaudoin, Citation2016, p. 15) to diverse student populations. In the United States, for example, 38% of undergraduate students are over 25 years of age, 58% work, 26% are raising children, 40% are attending part-time, and a growing number are ethnic minorities (Lumina Foundation, Citationn. d.).

This paper discusses a theory-based and practice-informed framework for the scalable expansion of flexible learning. The framework was implemented at a large, open-admission, regional higher education institution in the United States. Flexible learning in this context encompassed online learning, blended learning, competency-based education, and open educational resources. We first provide an overview of flexible learning and an examination of the four elements of flexible learning that are the focus of the framework as it was implemented at the university highlighted in this case study. We then provide a context for the framework, introduce the framework, discuss the steps for developing and implementing it, and share initial findings and implications.

Flexible learning

The key elements of flexible learning are pace, such as accelerated learning, part-time learning, or credit for prior learning; place, which may include classroom, home, and mobile learning as well as work-based and experiential learning; and mode, which refers to a delivery method (Gordon, Citation2014). One form of flexible learning is distance learning, which provides learners with options for pace – accelerated, part- or full-time study; place – where, when, and how learning occurs; and mode – technology-supported delivery such as online or by means of an app accessible on smart phone or tablet. Flexible learning empowers learners and offers them a choice in how, what, where, and when they learn (HEA, Citation2015).

Online and blended courses are two common approaches to flexible learning, and are often aimed at the needs of diverse learners, who are balancing school, work, and family. The term online refers to the technology or mode of delivery through which a course is offered. Learners complete all required elements of the course through an online delivery system (or an app) although they may participate in discussion forums or group projects involving interaction with each other and the instructor. Blended courses (also referred to as hybrid) consist of both an online and a face-to-face component. Students meet periodically in a classroom setting but less frequently than occurs in a traditional version of the class; other components of the course are accessed online. The number of class meetings vary and depend on the course design and course objectives.

Online learning

Non-traditional students are more likely to enroll online (Radford, Citation2011; Wladis, Conway, & Hachey, Citation2015) as are those with lower GPAs, ethnic minority students, and first-generation students (Ashby, Sadera, & McNary, Citation2011; Johnson & Palmer, Citation2015; Wladis et al., Citation2015). These factors must be considered when examining student success across learning modalities. Institutions must examine who is enrolling in online and blended courses, determine appropriate assessment measures, track student success, and ensure that effective support structures are in place, and address the needs of those unfamiliar with higher education or who may be at risk of failure.

Although online enrollments are expanding by 3.9% per year (Allen & Seaman, Citation2016), concerns about quality and student success continue. Nearly 45% of chief academic officers view retention in online courses as more difficult than in face-to-face courses, and 68.3% believe that the former requires greater discipline (Allen & Seaman, Citation2015). To address attrition rates, some institutions disallow certain populations from taking online courses, limit the number of online courses in which a student can enroll, and prohibit specific courses from being offered online (Liu, Gomez, Khan, & Yen, Citation2007).

Blocking students from online coursework will not improve outcomes nor does it provide a long-term solution to increasing demands for higher education globally and movements to democratize such opportunities. Data continue to show that an increasing number of individuals are entering and completing higher education, and that those successful in attaining degrees are not only more likely to be employed, but earn 56% more than those with only a high school education; however, immigrants and those with less educated parents are less likely to complete secondary education, and unemployment rates for these individuals are twice as high as for those who have completed it (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Citation2017).

First-time entrants to higher education, many of whom lack the cultural capital to be successful, may be more likely to participate in flexible learning in the form of online and blended learning as these delivery modalities increase access; however, these students may need the most support. We posit that success for all students enrolling in flexible forms of delivery can be achieved through course design and responsive pedagogies. Competency frameworks, outlining the digital skills and pedagogies needed by instructors in order to effectively use information and computer technologies in their teaching, must be developed and initial and ongoing training provided for higher education teaching staff (European Commission, Citation2014). Indeed, students may fare better in courses that have been intentionally designed and that provide embedded forms of support than in more traditional instructor-centric courses.

Competency-based education and open education resources

Additional components of flexible learning, which positively impact access, are competency-based education (CBE) and open educational resources (OER). Competency-based education provides self-paced learning opportunities in which students can demonstrate their competencies in certain areas. In some cases, students can gain credit for prior learning by demonstrating competencies they already have. In North American contexts, this is often referred to as Prior Learning Assessment (PLA), and in U.K. and E.U. contexts, it is often referred to as Accreditation of Prior Learning (APL). In the U.S., more than 500 higher education institutions reported offered some form of competency-based learning opportunities to their students (EdSurge, Citation2016). Both CBE and PLA are strategies for widening access to higher education for students who have significant experience in the workplace and who require a flexible way to demonstrate these abilities. Commonly, higher education institutions refer to CBE and PLA as opportunities for students to gain a university degree in less time and at a lower cost.

Open educational resources (OER) are a key strategy in the ‘opening up’ of higher education The use of OER is a key strategy for institutions that wish to become more open (Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition, Citation2016).

Open educational resources (OER) are teaching, learning, and research resources that reside in the public domain or have been released under an intellectual property license that permits their free use and repurposing by others. Open educational resources include full courses, course materials, modules, textbooks, streaming videos, tests, software, and any other tools, materials, or techniques used to support access to knowledge (Hewlett Foundation, Citation2019).

In an OECD (Orr, Remini, & Van Damme, Citation2015) report on open educational resources, OER is reported to help universities address six key educational challenges by:

Fostering new forms of learning for the 21st century

Fostering teachers’ professional development and engagement

Containing public and private costs of education

Continually improving the quality of educational resources

Widening the distribution of high-quality educational resources

Reducing barriers to learning opportunities

(Orr, Remini, &Van Damme, Citation2015)

In sum, these forms of flexible learning – online courses, blended courses, competency-based education, and open education resources – are innovative strategies that institutions are using to expand access and meet diverse learner needs. However, change in higher education, or in any organization, is not a simple matter, and requires vision, planning, structure, and strategy. These elements were considered in relation to the context for the change described in this article and in the development of a framework to guide the change.

Institutional context

The Framework for Flexible Learning, the focus of this article, was developed and implemented at an open admission higher education institution in the United States. At the time of implementation, the university had 37,000 students, which has now increased to 40,000. The university’s enrollments are projected to reach 45,000 by 2025. Students at this institution have a similar profile to those nationally in the U.S. −78% work from 21 to 31 hours per week, 30% are over the age of 25, and nearly 40% are first-generation (e.g. see Lumina Foundation, Citationn. d.). Enrollment increases are primarily due to demographics in terms of the number of students in the pipeline from secondary schools that feed into the university rather than to deliberate strategies to recruit additional students or increase enrollments through an expansion of flexible learning, and in particular, online learning, which may be the case at institutions with decreasing enrollments.

The institution’s mission is to provide access and opportunity for a broad range of students in order to meet regional workforce needs. The latter entails close collaboration with business and industry leaders to ensure that the university is providing future employees with appropriate skill sets and abilities. This might involve creating new academic programs or short-term training, certificates, or other credentials in addition to flexible delivery offerings such as online, blended, and off-site coursework.

With limited physical space and budget for expansion, the university sought to expand its capacity primarily through flexible delivery. Flexible delivery entails providing students with options in how, what, when, and where to learn and strives to meet the needs of both the institution and the student (HEA, Citation2015). Such endeavors require institutions and their constituents to rethink teaching and learning paradigms and related policies and practices. Student success must be central to these discussions, particularly in terms of supporting new entrants to higher education.

The framework for flexible learning – development and implementation

This section introduces the Framework for Flexible Learning and explains the steps involved in its development and implementation. This initiative was led by the university’s Office for Teaching and Learning (OTL). The mission of the OTL is to enable the enhancement of teaching and learning by providing faculty development opportunities, course design services, and learning technology support. This is best captured in its tagline – educate, innovate, transform.

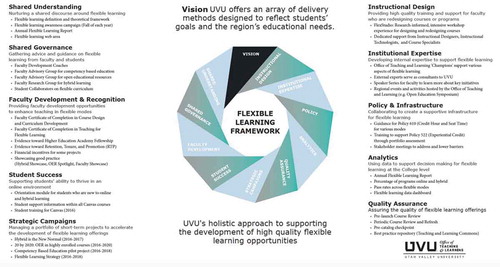

The OTL was specifically charged by the institution’s president and chief academic officer to increase flexible learning opportunities. The vision behind the initiative was to offer an array of delivery methods designed to reflect students’ goals and regional needs. The OTL defined flexible learning for institutional stakeholders as learning opportunities that give students a choice in the pace, place, and mode of study and lower barriers to higher education access. The latter includes the use of OER to lower costs. depicts the 11 areas within the Framework for Flexible Learning.

The framework is based on common elements, goals, and concerns across higher education, such as faculty governance, student success, and quality assurance, and as such, could be adopted by other institutions with adaptations to reflect context-specific variables and action steps. The aspects of the framework are next explained followed by the process for developing the framework. The latter is particularly important as it demonstrates how to launch a flexible learning initiative.

Framework aspects

This section outlines each aspect of the flexible learning framework to provide specific examples of how the vision for flexible learning was supported. The design of the framework was inspired by other frameworks for change initiatives within higher education. The OTL reviewed frameworks provided by the Higher Education Academy (HEA), such as those for flexible learning, embedding employability, and internationalizing the curriculum (see Advance HE, Citation2018). Similar to these frameworks, the elements of the OTL’s framework provide a comprehensive view of flexible learning that includes practical, infrastructure-building considerations (e.g., design, expertise, policy, strategic campaigns), process elements that emphasize collaboration (shared understanding, shared governance), motivational components (faculty rewards and recognition), evaluation and data collection (analytics, quality assurance), and desired outcomes (student success, faculty development). Additionally, each framework element contains a list of specific, practical action items.

The following discussion references two change models – Kotter and Cohen (Citation2002) and Bolman and Deal (Citation2017) – to demonstrate how the framework reflects practices leading to lasting change. Kotter and Cohen identify eight steps – 1) create a sense of urgency, 2) build a guiding team, 3) form a strategic vision and initiatives, 4) communicate for buy-in, 5) enable action by removing barriers, 6) generate short-term wins, 7) don’t let up, and 8) make change stick. Bolman and Deal encourage leaders to expand their perspective by viewing organizational issues through four frames – structural (policies, rules, reporting lines), human resource (people, motivation, rewards, training), political (conflict, power bases), and symbolic (vision, purpose, meaning, recognition). This theory-based framework provides a comprehensive view of what is involved in implementing an effective flexible learning change initiative.

Aspect 1: vision

The vision of the framework is aligned with a key objective of the university’s strategic plan, i.e. to offer an array of delivery methods designed to reflect students’ goals and the region’s educational needs. This vision is based on the institution’s mission, and specifically its role as a regional open-admission university. As such, it is familiar to stakeholders. Vision is critical in any change process as is creating urgency around that vision (Kotter & Cohen, Citation2002). In this case, urgency was conveyed with statistics showing past and projected enrollment growth, space needs, and budgetary constraints. Additionally, the vision was operationalized by the inclusion of specific initiatives and actions within in the framework. These aspects of the framework reflect Kotter and Cohen’s first step – form a strategic vision and initiatives.

Aspect 2: instructional design

An instructional design team provided expertise and support to faculty to redesign their courses to high-quality online learning experiences. The principal mechanism for this was a research-informed, workshop approach called Flex Studio, which mirrored the Carpe Diem (Salmon & Wright, Citation2014) and CAIeRO (Armellini, Howe, & Coulson, Citation2014) methodologies from the U.K. The instructional design aspect of the framework addressed the capacity-building needed to achieve the vision. It removed barriers (see Kotter and Cohen’s Step 5) that could have resulted from attempting to expand flexible learning opportunities without providing needed resources and developing faculty expertise (also consider Bolman and Deal’s human resource frame). Failing to develop stakeholder skills could have easily derailed the change process.

Aspect 3: institutional expertise

It was a priority to develop additional internal expertise to support flexible learning. To do this, the OTL invested in guest speakers, consultants, and training for its staff. Similar to the previous aspect, developing expertise is critical to ensuring that people know how to perform tasks associated with new directions. Professional development and training alleviates fear, builds confidence, and produces new skills. This strategy reflects Bolman and Deal’s human resource frame (Citation2017) and Kotter and Cohen’s (Citation2002) step of removing barriers and enabling action. Both focus on investing in people and providing tools to implement the desired change. The OTL staff needed to expand its expertise in order to help the faculty develop essential skills for online/blended course design and teaching.

Aspect 4: policy and infrastructure

Several policies related to online teaching and learning, and to other aspects of academic management were adjusted to be more supportive of flexible learning. For example, the university’s compensation structure for faculty to redesign flexible curriculum, the credit hour policy to account for time on task, and the university’s definitions of blended learning were adjusted to align with its efforts to enhance flexible learning. The policy and infrastructure aspect of the framework is primarily a structural element (Bolman & Deal, Citation2017), but also helps remove barriers (Kotter & Cohen, Citation2002). Institutions may need to examine documents outlining expectations for curriculum development, teaching, tenure and promotion, and even hiring. Some institutions create formal agreements with faculty members to design courses; these may delineate roles, expectations, intellectual property rights, review processes, timelines, and payment. Current processes and policies need to be reviewed to ensure that they enable the removal of barriers and help make change stick (Kotter & Cohen, Citation2002). Change is much more likely to stick if it is institutionalized in policy.

Aspect 5: analytics

The team used data from multiple sources to make decisions about flexible learning, and share updates with stakeholders. Annual reporting was used to raise awareness of the work being done to grow flexible learning offerings and enhance the quality of the flexible learning experience. For example, the OTL began publishing a Flexible Learning Report and presented data to show progress to various stakeholder groups. These groups included the Academic Affairs Council and the President’s Leadership Council. While leaders can use analytics, such as increases in faculty teaching online, new courses being launched, or student learning, to recognize short-term wins, Kotter and Cohen (Citation2002) would emphasize stories, such as compelling cases of how flexible learning changed the life of a student, rather than data. Success stories of faculty engaged in course design and online teaching are also advantageous. This approach is considered effective in getting buy-in and creating urgency; it appeals to the emotions and helps others see problems, needs, and working solutions first-hand. The OTL reports provided both quantitative and qualitative information.

Aspect 6: quality assurance

The quality assurance of flexible courses was addressed through peer review and other checkpoints along the approval pipeline, including a sign-off task prior to each course being listed in the course catalog. The OTL team reviewed well-known tools for assuring the quality of online course design, such as Quality Matters and the Online Learning Consortium toolkit, and took steps to create its own checklist of effective course design features. This was used in training workshops and in one-on-one consultation between instructional designers and faculty designers.

The quality assurance aspect of the framework enabled action by reducing a key barrier to change (Kotter & Cohen, Citation2002) – faculty concerns over quality, which is often a point of resistance. Quality assurance processes demonstrate that faculty controls the quality of online courses – content, requirements, tasks, and assessments. Quality standards often require peer review, a process familiar to faculty. These measures potentially result in making online courses more rigorous than face-to-face courses, which do not typically undergo a similar review. Thus, this structural change to implement quality assurance processes (Bolman & Deal, Citation2017) can be used to communicate for buy-in and demonstrate short-term wins (Kotter & Cohen, Citation2002) as faculty sees first-hand the rigor involved in online course design or in an OER textbook.

Aspect 7: strategic campaigns

The OTL spearheaded several promotional campaigns to raise awareness of their work in this area, and to gain buy-in from other stakeholders. Example of these campaigns included Hybrid is the New Normal, Hybrid is Double Awesome, and 20 by 2020 (20 completely online degrees by the year 2020). Each of these campaigns leveraged technology and multi-media to reach faculty and staff with creative messaging. For example, the OTL distributed USB storage devices to faculty and a note saying ‘watch me.’ On the storage device was a short video about the new initiatives toward flexible learning. To support the Hybrid is the New Normal project, faculty was asked to visit the initiative website to enter a raffle. On the website was a short video called ‘Double Awesome’ that explained how hybrid learning, if designed well, can combine the best of both online and face-to-face learning. Again, this aspect involves several aspects of Kotter and Cohen’s (Citation2002) steps for change – communicating for buy-in, enabling action, recognizing short-term wins, and not letting up. Communication through these campaigns was ongoing and wide-spread and impacted key stakeholders, particularly the faculty.

Aspect 8: student success

Enhancing student preparedness for learning in flexible modes was a priority for the guiding team. The OTL created video tutorials and other resources to help students thrive in the online learning environment. For example, short videos were created by the OTL that explained the nature of online and flexible courses and outlined the expectations of students in these environments. Links to tutorials for using the learning management system were embedded into each online and hybrid course. Walk-in, telephone, email, and live chat support were available to online students who needed technical support. The student success aspect of the framework addresses the human resource frame (Bolman & Deal, Citation2017) in that it helps students develop the learning strategies and skills to be successful in flexible learning contexts. It increases their confidence and can address the fears of the faculty as well. It also enables action by removing barriers and helps make change stick (Kotter & Cohen, Citation2002).

Aspect 9: faculty development and recognition

Faculty was supported to enhance their ability to teach effectively across flexible modes. Development opportunities were available through a new certificate in flexible teaching and learning, and various other workshops. Faculty was recognized in various ways, such as the Faculty Showcase for Teaching Excellence and specific showcases, such as the Hybrid Showcase. In this way, the university invested in its faculty members, expanded their capacity, and recognized them for their contributions. These strategies reflect two of Bolman and Deal’s frames – human resource and symbolic. The former focuses on developing the capacity of members of the organization in terms of skills and expertise while the latter emphasizes recognizing people for their accomplishments (e.g. see Bolman & Deal, Citation2017).

Aspect 10: shared governance

Faculty Advisory Groups were created for each key theme. These groups met on a regular basis to review progress on project plans and provide advice and direction to the OTL. This broadened the perspective of the guiding team and recognized that faculty are responsible for the curriculum. Advisory group members were committed, actively promoted change, and gained the trust and confidence of their colleagues, which helped create a strong supporting foundation for flexible learning. These strategies reflect aspects of Kotter and Cohen’s (Citation2002) steps to build a guiding team and communicate for buy-in. The involvement of faculty members was critical; the initiative could not succeed without them.

Aspect 11: shared understanding

The OTL worked to nurture a shared understanding of flexible learning by creating a web area, by publishing a flexible learning report, and by presenting its work to various groups. This resulted in transparency and was an effective way to communicate progress to key individuals and groups, answer questions, and address concerns. It supported buy-in by providing access to information and led to an increased common understanding of the initiative (see Kotter & Cohen’s communicate for buy-in step).

In sum, the framework offers a comprehensive view of what should be considered in the implementation of a flexible learning initiative, and does so based on widely-accepted change models (Bolman & Deal, Citation2017; Kotter & Cohen, Citation2002). The elements of the framework can be adopted or adapted by other institutions and leaders. Those doing so should consider the importance of capacity-building, collaboration, motivation, analytics, and outcomes, all of which are accounted for in the flexible learning framework as described earlier in this section. The 11 framework elements address these areas in more detail.

Developing the flexible learning framework

While the framework itself is key to managing an effective flexible learning initiative, much value resides in the process of developing the framework. Process elements must be jointly owned by institutional leaders and the guiding team for the project. In some cases, leaders will need to address these elements while in other cases, the guiding team will have primary responsibility. The four steps outlined in this section demonstrate foundational elements that had to be in place in order for the framework to be created and effectively implemented. These steps also reflect change model components as noted. For purposes of simplification, the steps are mapped to Bolman and Deals’ frames to demonstrate how all aspects of change were considered.

Step 1: organizational structure and resources – the structural frame

A first step in developing and implementing the Framework for Flexible Learning involved creating a space in which to situate the work. This entailed restructuring several units, but most notably, distance education and the faculty excellence center, to create a new unit, the OTL. Distance education had operated as a stand-alone entity with responsibility for developing and managing online courses, providing instructional design and technology support, hiring faculty (internally) to teach online courses, and student support. The faculty center offered events, workshops, and trainings on effective teaching. Training and support for technology in teaching and learning were offered by a third entity, which was also integrated into the OTL.

The restructuring enabled the hiring of an assistant vice president to lead the OTL. She was charged with creating a strategic plan to expand flexible learning and with associated faculty development, instructional design, and learning technologies. Additional funding was made available to hire faculty coaches, who served critical mentoring and advisory roles, as well as more instructional designers and other OTL staff to increase capacity for flexible learning. A new physical space was identified and remodeled. This space was centrally located and became an inviting gathering place for faculty. These resource allocations, and the title of the unit’s leader, demonstrated the institution’s commitment to flexible learning. Once these structural changes were in place, the OLT team commenced its work.

Step 2: a shared understanding – the human resource and political frames

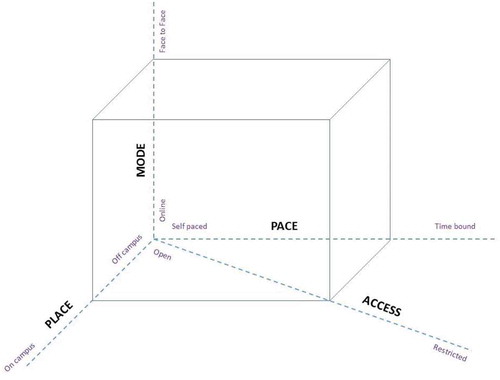

The OTL team developed a conceptual understanding of flexible learning that could be shared across the institution. Drawing on Gordon’s (Citation2014) pedagogical model for flexible learning (i.e. pace, place, mode), the OTL created an adapted version that showed a fourth axis for ‘access’ (see ). In doing so, this gave the institution a way to define and discuss flexible learning as providing educational opportunities that provide students ‘choice in the pace, place, and mode of study’ (Gordon, Citation2014, p. 4), and that lower barriers to entry, such as the cost of textbooks, e.g. OER.

Figure 2. Pedagogical space for flexible learning (adapted from Gordon, Citation2014).

As higher education institutions are loosely coupled, meaning there is typically a lack of coordination across departments, which operate independently, as well as a lack of hierarchical decision-making, and because the faculty are hired as specialists and given control over their areas of expertise – particularly, curriculum and instruction – leaders must take a collaborative approach (Frederickson, Citation2017; Weick, Citation1976). As such, faculty were involved in creating vision for the OTL and influencing its direction (see also the framework aspects of developing faculty expertise and shared governance). Faculty involvement, particularly the Faculty Advisory Groups, helped build coalitions of support across the university and address conflict.

This step of the process was supported in several ways. First, a workshop-based approach to flexible course design was introduced. Within the first nine months, it was offered, 62 faculty joined these sessions. Additionally, several faculty advisory groups were formed to share ideas and influence planning toward hybrid/blended learning, competency-based education, and open educational resources. Through extensive internal marketing and communication activities, and through these face-to-face activities, it was possible to nurture a shared discourse around flexible learning.

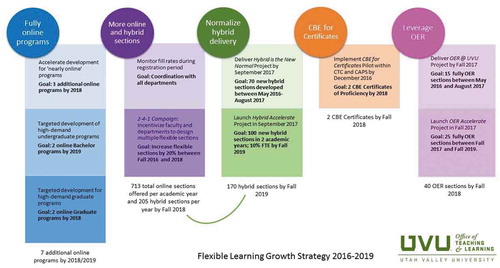

Step 3: vision and strategy – the symbolic frame

After establishing a definition of flexible learning, the OTL outlined a vision and strategic plan that supported the direction given them from institutional leaders. The team considered current approaches to learning that reflected the definition. These included online, blended, competency-based, and open educational resource-based courses, and other courses that required off-campus activities as part of the learning experience. At that point, the team designed a three-year strategic plan that focused on meeting the challenges of institutional growth, limited physical space, and inclusion (e.g. providing educational opportunities to an increasingly diverse population). While institutional leaders conveyed to university stakeholders in a general way that flexible learning was central to the future, the guiding team, with extensive input from across campus, defined the specific strategies needed to accomplish the vision.

shows the three-year strategic plan for flexible learning. This plan was communicated to several faculty advisory groups and staff teams in draft form, and then revised based on feedback. The plan was then presented to deans and executive staff to share ideas and establish a sense of accountability across the institution.

The three-year strategic plan outlined five priority areas for the university:

To develop more fully online programs

To develop more online and hybrid courses/sections

Normalize hybrid delivery

To introduce competency-based certificate pathways

To leverage open educational resources

The plan showed distinct projects or campaigns to support each priority, and included a quantitative goal for the three-year period ().

Step 4: integrating systems and structures – reframing

To support growth in flexible learning in a sustainable way, it was important to create an institutional ecosystem that nurtured the work. Drawing on the Higher Education Academy’s (HEA’s) Framework for flexible learning in higher education, the OTL designed the Framework for Flexible Learning to address certain sections of the HEA’s model. , discussed in detail in the previous section, depicts the various institutional systems and structures (HEA, Citation2015) that were identified by the OTL as being integral to sustainable growth in flexible learning. This step reflects the reframing concept as an overarching approach to create lasting organizational change.

Outcomes

Since implementing the Framework for Flexible Learning, each of the systems and structures in the framework have been developed and incorporated into the institution’s strategic planning process. As a result, several positive outcomes have been realized.

The number of faculty teaching online has increased and significant numbers of new instructors are teaching online each year. The number of sections and unique courses being offered online has also increased (see ). Note that the table compares data from each fall semester.

Table 1. Online course fall-to-fall comparison.

Online Course Fall-to-Fall Comparison

The OTL is working with department chairs to prioritize projects for online development. The focus is on the 50 highest enrolled courses that will impact the greatest number of students to provide greater access and an improved learning experience.

The number of faculties redesigning their face-to-face courses to online or blended courses increased from 27 in Year 1–72 in Year 2–98 in Year 3.

A quality assurance process for online and blended courses has been implemented to provide constructive feedback to faculty who teach in these modes. This process involves peer review based on a rubric and provides constructive feedback to both instructional designers and faculty subject matter experts. The feedback is respected as an external peer review of quality, as it is intended to be.

New reporting processes have been adopted to provide greater accountability and to raise awareness across the institution. These measures have continued efforts to communicate for buy-in, reflecting Kotter and Cohen’s admonition to not let up. This is critical to sustaining change and making it part of organizational culture.

The instructional design team has deepened their expertise through additional professional development activities. These have included an extensive array of guest speakers, workshops from external experts, and conference attendance. OTL staff have become ‘champions’ over specific aspects of flexible learning, which has been an incentive for them to develop their skills and share them with faculty.

Faculty development for flexible learning has been extended to provide a certification pathway for faculty who design and teach flexible courses. This pathway has enabled faculty to pursue fellowship recognitions through the Advance Education/Higher Education Academy scheme. An online course to train faculty members to teach online has also been developed and implemented.

Overall, these outcomes demonstrate incremental increases in the number of online and blended courses, faculty member involvement, and in faculty skill sets as the framework has been implemented. As data is collected and analyzed and feedback received from various stakeholders, those leading this effort continue to communicate for buy-in, update the strategic plan and action steps, enable action, and not let up in order to make the changes become embedded into the organizational culture. Several modifications have been made such as prioritizing the highest enrolled courses for development and working through department chairs rather than with individual faculty members to ensure that the critical courses are developed for online and blended delivery rather than low-enrolled boutique courses. The framework provides a comprehensive guide for the institution’s flexible learning initiative, helping leaders examine and account for critical components on an ongoing basis. Use of the framework has ensured that these components are integrated into the strategic planning process, which has increased accountability, organizational change, and cultural change.

Implications for practice

The “future of education in the twenty-first century is not simply about reaching more people, but about improving the quality and diversity of educational opportunities (Orr et al., Citation2015, p. 11). As such, flexible delivery programs must ensure effective design and pedagogical practice. Flexible learning represents a ‘partnership between [higher education providers] and students with the goal of providing accessible yet manageable learning opportunities for a wide range of people’ (HEA, Citation2015, p. 4). The Framework for Flexible Learning indicates one approach for accomplishing this goal.

The Framework for Flexible Learning provides institutions with a structure to guide discussion and planning. The 11 aspects of the framework create topic areas for teams to discuss and develop further. The examples provide possible ways for institutions to create a similar approach, or to highlight their existing approaches. Establishing and achieving strategic goals for flexible learning entails leadership and change. Implementation of the Framework for Flexible Learning must be managed in a way that leads to stakeholder buy-in and support and in making change stick. Institutions wanting to adopt or adapt this framework, or create one of their own, must consider how to manage change. Models for change, such as those referred to in this article, can provide guidance in this regard.

The framework offers a starting point for thinking and dialogue surrounding the implementation or enhancement of a flexible learning initiative. The 11 aspects of the framework are applicable across institutions; however, both these and the specific action steps for each can be adjusted to fit different contexts. As such, university leaders can adapt the framework to fit the institution’s needs and the specific elements of flexible learning it determines to emphasize. The framework also reflects principles of effective change, which should be considered as lenses through which to ensure change will be a permanent part of the organization’s culture.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Advance, H.E. (2018). Higher Education Academy frameWORKS. Retrieved from https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/institutions/consultancy/frameworks.

- Allen, E., & Seaman, J. (2016, February). Online report card. Tracking online education in the United States. Oakland, CA: Babson Survey Research Group and Quahog Research Group. Retrieved from http://www.pearsoned.com/higher-education/online-report-card-2016/.

- Allen, E.I., & Seaman, J. (2015). Grade change: Tracking online education in the United States. Babson Park, MA: Babson Survey Research Group and Quahog Research Group. Retrieved from. http://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/gradelevel.pdf

- Armellini, A., Howe, R., & Coulson, K. (2014, December 3–5). Effective online collaboration and academic skills within a transferable quality framework in higher education. Workshop presented to Online Educa – 20th International Conference on Technology Supported Learning and Training, Berlin, Germany. Retrieved from http://nectar.northampton.ac.uk/7220/.

- Ashby, J., Sadera, W.A., & McNary, S.W. (2011). Comparing student success between developmental math courses offered online, blended, and face-to-face. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 10(3), 128–140.

- Beaudoin, M. (2016). Issues in higher education—A primer for higher education decision makers. In B.O. Barefoot & J.L. Kinzie (Series Eds.), New Directions For Higher Education, & M.S. Andrade (Vol. Ed.), Issues inDistance Education (Vol. 173, pp. 9–19). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. doi:10.1002/he

- Bolman, L.G., & Deal, T. (2017). Reframing organizations: Artistry, choice, and leadership (6th ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- EdSurge. (2016, July 27). Two reports show untapped potential of competency-based education. Retrieved from https://www.edsurge.com/news/2016-07-27-two-reports-show-untapped-potential-of-competency-based-education

- European Commission. (2014, October). High level group on the modernisation of higher education. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/education_culture/repository/education/library/reports/modernisation-universities_en.pdf

- Fredericksen, E.E. (2017). A national study of online learning leaders in US higher education. Online Learning, 21(2). doi:10.24059/olj.v21i2.1164

- Gordon, N. (2014). Flexible pedagogies: Technology-enhanced learning. Retrieved from https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/resources/tel_report_0.pdf.

- Hewlett Foundation. (2019). Open education resources. Retrieved from https://hewlett.org/strategy/open-educational-resources/

- Higher Education Academy. (2015). Framework for flexible learning in higher education. York, UK: Author. Retrieved from. https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/enhancement/frameworks/framework-flexible-learning-higher-education

- Johnson, D., & Palmer, C.C. (2015). Comparing student assessments and perceptions of online and face-to-face versions of an introductory linguistics course. Online Learning, 19(2), 1–18.

- Kotter, J. & Cohen, D.S. (2002). The heart of change. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School.

- Liu, S., Gomez, J., Khan, B., & Yen, C.J. (2007). Toward a learner-oriented community college online course dropout framework. International Journal on E-Learning, 6(4), 519–542. Retrieved from https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/21789/

- Lumina Foundation. (n. d.). Today’s reality. Retrieved from https://www.luminafoundation.org/todays-student-statistics

- Maslen, G. (2012, February 19). Worldwide student numbers forecast to double by 2025. Retrieved from http://www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story=20120216105739999

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2017). Education at a glance. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/edu/education-at-a-glance-19991487.htm

- Orr, D., Remini, M., & Van Damme, D. (2015). Open educational resources: A catalyst for innovation. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/9789264247543-en

- Radford, A.W. (2011, October). Learning at a distance. Undergraduate enrollment in distance education courses and degree programs. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from. http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2012154

- Salmon, G., & Wright, P. (2014). Transforming future teaching through ‘Carpe Diem’ learning design. Education Sciences, 4(1), 52–63.

- Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition. (2016). Annual report SPARC 2016. Retrieved from https://www.sparc-climate.org/fileadmin/customer/6_Publications/ProgPlan_PDF/SPARC_AnnualReport2016_web.pdf

- Weick, K.E. (1976). Educational Organizations as Loosely Coupled Systems. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21(1), 1–19.

- Wladis, C., Conway, K.M., & Hachey, A.C. (2015). The online STEM classroom–Who succeeds? An exploration of the impact of ethnicity, gender, and non-traditional student characteristics in the community college context. Community College Review, 43(2), 142–164.