ABSTRACT

As a consequence of increasing pressures to enhance assessment and feedback in response to the National Student Satisfaction (NSS) and Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF), universities continue to invest significant time and resources in making improvements to this area of practice. Since 2013 the University of Greenwich has adapted, enhanced and implemented an approach called TESTA (Transforming the Experience of Students through Assessment). This case study offers a unique and sustained institutional perspective of the landscape of assessment and feedback. It examines the results from the analysis of 157 programmes over 5 years categorised as a top ten set of challenges. Through an examination of programme documentation and module evaluation by staff, the paper highlights some findings of facilitators, barriers and impact at institutional, faculty, departmental, programme and module levels. Its ultimate aim is to explore the real impact of TESTA and to contribute to an understanding of the conditions required for making and disseminating changes and spreading good practice across an HE institution.

Introduction

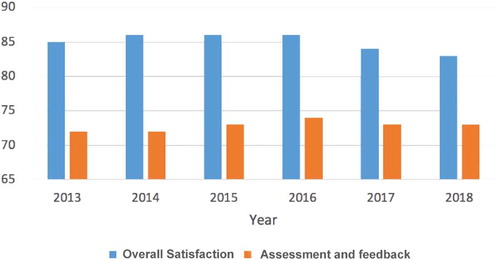

Higher education (HE) market mechanisms such as the National Student Survey (NSS), now incorporated into the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF), seek to control the quality of teaching, learning and assessment through competitive ranking systems (Burgess, Senior, & Moores, Citation2018; Hillman, Citation2017). Since the start of the NSS in 2005, assessment and feedback have been at the sharp end of this, with rates of student satisfaction lower than for most other areas ().

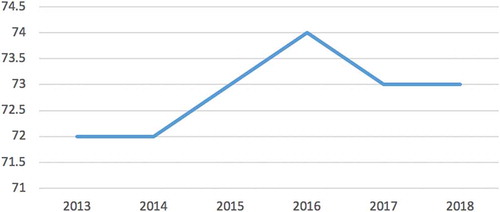

Low returns on assessment and feedback in the NSS have been the object of much hand-wringing and scrutiny (Gibbs, Citation2015) and the focus of many subsequent funded initiatives. Interventions have taken different perspectives and adopted a wide range of methodologies. Some have developed principles of effective practice (REAP, Nicol, Citation2007), which have been debated, discussed and disseminated through programme/module team activity, such as Viewpoints (Jisc, Citation2015); others have aimed to improve students’ attainment through such technological interventions as the MAC initiative (Kerrigan et al., Citation2011) which used a feed-forward approach to help students reflect on their preparation and completion of future work. Whilst they have had some impact, their influence has been limited (largely to local level), driven by enthusiasts and lacking in institutional sustainability. Generally, projects have been taken up neither systematically nor consistently across the sector, nor within institutions – except through a policy response, such as the setting of targets for the return of marked work. With year-on-year NSS results showing, at best, a levelling-out or, more recently, a downward trend (), the search for large-scale impactful ways to improve assessment and feedback continues.

Recent initiatives, such as ABC (UCL, Fung, Citation2017), CAieRO (University of Northampton, Usher, Citation2014) and PACE (University of Greenwich), emphasise the importance of assessment design using learning-design approaches at modular and programme level. They aim to balance the load and variety of assessment and to overcome some of the drawbacks of the all-pervasive modular structure of HE degrees. Other initiatives focus on the development of students’ assessment and feedback literacies, self-regulation, and their partnership in learning (EAT framework, Evans, Citation2016; DEFT toolkit, Winstone & Nash, Citation2016). One initiative, globally implemented at many universities, is TESTA (Transforming the Experience of Students Through Assessment)Footnote1, with its emphasis on assessment and feedback at programme level. Unlike other initiatives, TESTA considers a wide range of assessment issues – by means of an analysis of load, variety, timeliness and quality of feedback through different lenses – and produces evidence-informed recommendations that can be used to encourage positive changes in student and staff behaviour.

TESTA research has produced useful insights into assessment patterns – it has demonstrated, in particular, the negative impact of structural barriers. For example, modular design can over-emphasise the student experience of the module at the expense of the programme which is the true heart of the student experience. It may also adversely influence academics’ understanding of assessment across programmes, with such significant consequences as over-assessment and risk of surface learning (Jessop & Tomas, Citation2017; Tomas & Jessop, Citation2018; Wu & Jessop, Citation2018). There is a convincing argument for enhancing assessment practice by working systematically at programme level as the picture of students’ journey through their modules becomes much clearer. This programme-level approach enables academic teams to make evidence-based decisions with direct and positive impact on students’ experience and attainment and therefore, one might infer, on the NSS and the TEF.

By presenting the experience of a systematic, institution-wide, five-year adaptation and implementation of TESTA, this paper offers a unique and sustained institutional perspective of the landscape of assessment and feedback. It provides an updated ‘top ten’ list of assessment and feedback challenges and builds upon previous research on this topic (Walker, McKenna, Abdillahi, & Molesworth, Citation2017).

After outlining the characteristics of the TESTA@Greenwich approach, this case study reports on the methodology used to develop the set of ‘top ten’ institutional challenges. It then sets out to explore the challenges and barriers to improving assessment and feedback at institutional, faculty, departmental, programme and module levels. Its ultimate aim is to examine the real impact of TESTA and to contribute to an understanding of the conditions required for making and disseminating changes and spreading good practice across an HE institution.

Ethics

This study formed part of a professional audit conducted with the approval of Professor Simon Jarvis, Deputy Vice-Chancellor, University of Greenwich, with ethics consent sought and approved by University Ethics Committee. Data from the module surveys were compiled in collaboration with the Directorate of Planning and Statistics. All but the last author of this paper are responsible for promoting the methodology within the institution. The risk then is that observation – and hence reporting – is particularly ‘theory-laden’ (Kuhn, Citation1996) and potentially coloured by a positive view of TESTA. The authors’ efforts to mitigate this effect include consistent, accurate record-keeping and reporting for quantitative data. An example of unbiased reporting is that the lead author published a quantitative paper affirming that TESTA had no effect on first-year student retention rates (Walker et al., Citation2017). The authors are correspondingly aware that the analysis of qualitative data presented here may reflect unconscious bias.

The treatment of qualitative data in the form of personal opinions provided by students () reflects the guidance offered by the British Educational Research Association (BERA, Citation2018). For example, student participation in survey or focus groups was voluntary. Participants were told how their data would be used and confidentiality was maintained. Any potential for negative consequences for participation was mitigated by conducting focus groups away from students’ study locations and away from any academic staff associated with the students’ programmes of study.

TESTA@Greenwich

The TESTA methodology was first trialled at the University of Greenwich in 2013, using the original methodology developed by Graham Gibbs and Tansy Jessop as a National Teaching Fellowship project funded by the Higher Education Academy from 2009–12 (Jessop, El Hakim, & Gibbs, Citation2014). The methodology was further developed to meet the specific perceived needs of the University of Greenwich and became known in the institution as TESTA@Greenwich. Greenwich is one of the most extensive and successful adopters of TESTA across the sector (Jessop, Citation2017), with a dedicated team (a project leader, a project officer, a data analyst and an intern) based in the Educational Development Unit. One of the strengths of the team is its diversity and complementarity: some members are close in age to the students and are themselves former students of Greenwich, a clear asset when running student focus groups; the team combines data and statistics experts with an assessment, feedback and curriculum design specialist with extensive HE teaching experience. In short, the composition of the team provides credibility for both staff and students.

The original TESTA looked at assessment and feedback at programme level through the lens of audits, student focus groups and questionnaires, in order to gain a comprehensive picture of students’ assessment and feedback journey and experience. TESTA@Greenwich has built on the original methodology and has made a number of adjustments and additions:

Students of all years (not just the final year) are included in the exercise, so as to provide a thorough picture of their experience at all stages of the programme.

A detailed analysis of written coursework feedback has been added to the audit part of the process. In addition to the average word count (which is part of the original methodology), TESTA@Greenwich analyses the balance of praise, criticism and advice given in written feedback.

The Assessment Environment Questionnaire (AEQ) includes questions relating to employability and perceived fairness of assessment. Boxes for comment add to the qualitative data gleaned from focus groups.

We have developed an institutional benchmark tool – an update of Gibbs’ model (Citation2007) – for the Assessment Environment, obtaining scales which are comparable to those of (Jessop & Tomas, Citation2017). The novelty of the TESTA@Greenwich benchmark is that it concentrates on Greenwich’s environment.

Improved assessment visualisation through the development of Map My AssessmentFootnote2 (MMA) which has been integrated as a core part of the audit process. Building on the original concept of the ESCAPE project (Russell & Bygate., Citation2010), MMA is an online platform that enables staff to visualise a complex picture of module assessment information across modules and programmes. It stimulates discussion of formative and summative assessment distribution by module and programme teams, with the aim of improving the holistic experience of assessment from the student’s viewpoint. This has led to a step change in eliminating assessment bunching and choke points, introducing or reducing assessment variety, reducing assessment volume and meeting marking turnaround deadlines more effectively. This visualisation has subsequently been built into the university’s student management information system.

The TESTA@Greenwich report includes recommendations and commendations which are now part of the quality-assurance process requiring programme teams to reflect and take action.

This last point has enabled us to produce an annual ‘top ten’ – henceforth institutionally referred to as the ‘Top 10 Recommendations’ – of the most frequently cited assessment and feedback-related recommendations generated through TESTAFootnote3.

The ‘top 10 recommendations’ methodology

Over a five-year period, 157 programmes across all four faculties have been audited by means of the TESTA methodology. Owing to data protection and confidentiality agreements between TESTA staff and programme teams, individual programmes are not identified. In this case study, ‘completion’ is defined as full engagement by programmes with all five TESTA@Greenwich process elements, viz: 1) Audits; 2) Assessment Experience Questionnaires (AEQ); 3) Focus Groups; 4) Feedback Analysis; and 5) Map My Assessment. Programmes that had only partially completed the TESTA process – i.e. those that had started a particular stage but did not see it through – were, on account of missing values, omitted from the dataset. Relatively few programmes – thirty-two in total – lacking values were dropped from the final dataset. All other programmes – for example, those which had not yet entered TESTA or were still in the process of going through (and were therefore still in the process of collecting assessment and feedback data) – were not considered. By faculty, the final sample comprised:

Sixty Education and Health programmes;

Forty-two Architecture, Computing and Humanities programmes;

Thirty-five Business programmes; and

Twenty Engineering and Science programmes.

The Assessment Experience Questionnaire (AEQ) captures students’ views about their experience of assessment and feedback across their programme. These are grouped into 10 broad themes (quantity of effort, coverage of syllabus, quantity and quality of feedback, clarity of feedback, use of feedback, appropriate assessment, clear goals and standards, deep approach, learning from the examination, and overall satisfaction). The TESTA recommendations are derived from these groupings. As the groupings were in some cases too broad and too limiting, a new – two-stage – coding approach was adopted. The first stage consisted of textually analysing each of the 438 recommendations from the 157 programmes and then classifying them into three broad themes: (1) Assessment (2) Feedback (3) Other. The second stage repeated the first, but it deconstructed these broad themes into finer – granular – sub-themes based on key words and phrases; for example, ‘Assessment’ was deconstructed into spread, volume, weighting and variety, while ‘Feedback’ was broken down into timeliness, clarity, depth and consistency. Seven per cent of recommendations did not fit within the themes and were classified as ‘other’.

Findings from our analysis have provided valuable insights into assessment and feedback and form our top 20 challenges (). These challenges are multifaceted and cover a wide range of issues – from inconsistent delivery of feedback to unvaried assessment environments – and draw particular attention to aspects of programme design (e.g. ensuring that students experience a deep approach to learning). We focused on the challenges that appeared most regularly and disseminated them across the institution as a ‘Top Ten’. These have also been analysed at faculty and departmental levels. The notion of having a top ten set of challenges appears to be attractive for a number of reasons: we are accustomed to working with lists and rankings; grouping similar items into categories aids interpretation of difficult concepts and helps to identify their origin; a ‘Top Ten’, like ‘the law of threes’, is easily digestible – senior managers can sift out discrete problems and focus on targeted solutions to them, while developers can steer programme-team discussions to specific measures for enhancement.

Table 1. TESTA top 20 challenges.

The major revelation yielded from this research, however, was the insufficient clarity of goals and standards communicated to students throughout their degree. This outlier has persisted as the number one challenge throughout all five rounds and is particularly concentrated at the start of students’ higher education journey as they adjust to the transition into higher education. This confirms the results of a previous study of predictors of retention at the University of Greenwich: it found that first-year students had exponentially greater odds of attrition compared to second- and third-year students (Walker et al., Citation2017). Other significant findings of the ‘Top 10ʹ include a lack – or a perceived lack – of linkage between modules on a programme, limited use of formative assessments to develop understanding, delayed feedback return times, uneven spread of assessments (creating choke-points), lack of depth in feedback and overload of assessments.

Facilitators for and barriers to change

The embedding of TESTA in the Quality Assurance process at Greenwich – and more specifically the quinquennial review (revalidation of a programme) – requires academic teams to document their responses to change. Consequently, TESTA results now play an integral role in panel discussions about the evolution of a programme. As part of their preparation for review, programme teams have to place assessment and feedback at the heart of reflective activity and discussion about teaching and learning. A TESTA analysis is timed for the moment when programme teams actively review and update a programme; it therefore provides the opportunity for maximising the overall impact of the student assessment experience.

Two core principles – of confidentiality and neutrality – permeate the process and are key to building trust with programme teams. The resulting recommendations are non-binding – programme teams choose how best to respond. They therefore feel a greater sense of ‘ownership’ of the data and make team decisions about what to change to improve the design and delivery of the curriculum. The only requirement from the Quality Assurance point of view is that programme teams must respond to the recommendations in their critical appraisal. Enhancement is a collaborative and somewhat messy process to which individual players bring uniquely personal knowledge and insights. The TESTA team – like other staff outside the discipline or professional area – is unlikely to know the intricacies and internal logic of the subject or discipline; for example, a TESTA recommendation to ‘reduce volume’ or ‘increase variety of assessment’ may be inappropriate if a Professional Statutory and Regulatory Body (PSRBs) requires a particular volume or type of assessment.

The principle of confidentiality has to be balanced with accountability and the achievement of institutional impact – the ‘top ten’ list is therefore discussed at the highest levels of the institution and informs such key policies as the University’s ‘Learning, Teaching and Assessment Strategy’ and ‘Feedback and Assessment Policy’. Faculty Directors of Learning and Teaching and Faculty Quality Assurance staff also engage strategically with the ‘top ten’. Over 90% of departments have invited the TESTA team to present the methodology and general findings to academic teams. It is therefore apparent that TESTA has direct impact at institutional level. But what about its impact on programmes?

The critical appraisal required from programme teams as part of the quinquennial review provides useful documentary evidence of the potential impact of TESTA at programme level. An analysis of critical appraisal documentation was undertaken for eleven undergraduate and postgraduate programmes that had been through a TESTA audit in the latest round.

The first step was to identify and code references to TESTA and replicate the same procedure across all programmes within the sample. shows:

TESTA recommendations. These are provided by the TESTA team in the presentation of their findings but are not always mentioned in critical appraisal reports.

Recommendations met: These are identified if the critical appraisal document contains sufficient evidence of how the recommendations are being met. In addition, we were also interested to see if TESTA was cited as the factor determining whether the recommendations were met.

Table 2. Number of recommendations met (sample size = 11 programmes).

Overall, out of all the recommendations met, 69% were attributed to TESTA as the key factor behind the successful meeting of recommendations. As can be seen, from a sample of eleven programmes, the TESTA team made sixty-seven recommendations. Based on a textual analysis of critical appraisal documents, 42 recommendations (63%) were deemed to have been met. From this point of view, TESTA has a significant impact on programmes. The limitation of our study, however, is the small number of programme documentations analysed – owing to the fact that explicit mention of TESTA in review documentation has been mandatory only since September 2017. The findings from the critical appraisal document do not form a complete picture as data that may inform this particular analysis is missing from rounds one, two and three.

What about the impact of TESTA on modules? Whilst the focus of TESTA is assessment at programme level, analysing its impact at module level is valuable, as many changes recommended by TESTA require adaptation of modules. As Helen McLean (Citation2018) reminds us, many barriers to the development of effective assessment approaches are situated in individual academics’ circumstances (such as the context in which they work, conflicting motivations and priorities, previous experiences of assessment, etc.). In this respect, the University of Greenwich’s 2017 module survey (a pilot investigation which asked module leaders questions about changes to, and innovation in modules) provides some insights into questions posed about the impact of TESTA and MMA.

In answer to the question ‘Was the assessment and feedback structure of this module informed by TESTA@Greenwich?’ only 12% of 806 module leaders responded positively, whilst almost three-tenths (29%) did so negatively. However, more than a third of the respondents (35%) answered: ‘Don’t know’. Such a response indicates that TESTA is still not fully embedded at module level, although it is worthwhile to point out that nearly a quarter (24%, or 191 respondents) also stated that they were not yet at pre-review stage, so there was no expectation that their modules would have been informed by TESTA.

A follow-up question asked: ‘If you answered yes, please explain briefly how TESTA findings were used.’ Key findings were that the majority of respondents stated or implied that TESTA was used as part of the review process for the programme (61%). Of this percentage, 10 respondents made the general statement that TESTA was involved in review, the remainder stated the outcomes of that review process. These comprised both confirmation that no change was needed, identification of issues, either unspecified or related to assessment structure such as volume and timing. A smaller percentage of respondents (35%) stated concrete actions that had been taken as a result of the TESTA review process. These included changes to the timing and volume of assessment and feedback as well as consultation with students.

Thirty-one per cent of respondents (73 module leaders) who answered ‘no’ to the question ‘Was the assessment and feedback structure of this module informed by TESTA@Greenwich?’ explained their answer.

Key findings were that a lack of experience or awareness of TESTA accounted for nearly three-tenths (29%) of the responses, while just under a quarter (21%) of respondents said that their course: had not been through TESTA; was a new course; was about to be involved in the TESTA process. Just over one-tenth of respondents (11%) said TESTA had not been rolled out in their faculty at the time. One-tenth of respondents (10%) also indicated that their adoption of a particular assessment structure was governed by the influence of professional bodies whose recommendations they were (and still are) compelled to follow.

The above results are not surprising: TESTA focuses on programmes undergoing review; the timing of the survey in relation to the TESTA process and the review cycle thus meant that not all of the module leaders surveyed had experienced TESTA in the preceding year. It is encouraging to see that a proportion of respondents did highlight TESTA as an influencer. However, what this result also shows is how slowly change occurs in large institutions.

Conclusion

This case study set out to examine the degree to which TESTA@Greenwich has been embedded within the institution and what barriers and facilitators might appear at different levels of the University.

What makes TESTA@Greenwich a success is a combination of factors. It benefits from institution-wide support and, because it is embedded in the quality-assurance review, all programmes across the University will in time have gone through the process (approximately half of programmes have been audited so far), thus providing an increasingly detailed picture of assessment and feedback across the institution. The confidentiality of the reports ensures the programme teams’ buy-in and their openness in discussions. That the academic teams are required to document responses and are challenged through a robust revalidation process means that they take the recommendations seriously, with consequent direct impact on programme design.

The production and dissemination of the ‘Top 10ʹ TESTA recommendations is a key tool in promoting the importance of learner self-regulation and assessment for learning at Faculty and University level, and its impact on University policy (for example, the importance given to formative assessment) is clear.

However, much remains to be done to continue enhancing assessment and feedback across the institution. As our analysis has revealed:

the timing of TESTA in the fourth year of the quinquennial review process may be too late for making changes to the design of assessment. Other changes, such as approaches to feedback or communications of goals and standards are, however, easier to implement, as these relate to practice, not design. There are currently discussions about changes to the timing of TESTA from the fourth to the third year of the review process. The fourth year then would accommodate programme development workshops to help programme teams implement recommendations in time for the Review.

a perceived lack of agility due to university regulations. Changing assessment weightings, patterns and approaches is regarded as a barrier. In response to this, further guidance on regulations and timings should be developed.

difficulties, reported by Programme Leaders, exist in the application of changes at module level. Assessment bunching, for example, occurs at programme level, but changes need to be made by module leaders. It is therefore crucial that TESTA reports are disseminated to the whole teaching team, especially module leaders.

a lack of communication between programme and module leaders is regarded as a potential barrier, especially relating to assessment bunching. MMA is seen as a valuable tool to assist with discussions as it provides a visualisation of the student journey. As assessment drives teaching, this could well have an impact on how modules are delivered.

that follow-up on the TESTA recommendations is also key – future developments of TESTA@Greenwich include devising a methodology for more systematic tracking of the impact of recommendations on programme design and the provision of training to support staff in assessment design and problem-solving.

Our experience with the implementation of TESTA provides an insight into how change can be encouraged and supported across an institution. It also shows the challenges to be addressed at different levels when attempting to embed new approaches. Some strategies have been implemented across the sector to achieve and sustain assessment and feedback enhancement. In 2018, however, NSS feedback and assessment scores flatlined or decreased across the sector; the deep embedding of TESTA has enabled the permeating of awareness and actions on assessment and feedback and may account for this institution having bucked the sector norm. We have learnt some general principles that provide us with insights into the challenges, barriers and facilitating features in the making of changes at module, programme, faculty and institutional levels. The external deep-dive evaluation – built on trust and collaboration and resourced appropriately with a combination of academic expertise and data-analysis skills, as is characteristic of our approach – may provide ways forward for other institutions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

3. Although there are differences between TESTA@Greenwich and TESTA, references to TESTA@Greenwich are simply started as TESTA in the rest of this case study to assist readability.

References

- British Educational Research Association [BERA]. (2018). Ethical guidelines for educational research (4th ed.). London. Retrieved from https://www.bera.ac.uk/researchers-resources/publications/ethicalguidelines-for-educational-research-2018

- Burgess, A., Senior, C., & Moores, E. (2018). A 10-year case study on the changing determinants of university student satisfaction in the UK. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0192976

- Evans, C. (2016). Enhancing assessment feedback practice in higher education: The EAT framework. EAT. Retrieved from https://www.srhe.ac.uk/downloads/events/280_EAT_Guide_CE.pdf

- Fung, D. (2017). A connected curriculum for higher education. London: UCL Press. doi:10.14324/111.9781911576358

- Gibbs, G. (2015). Maximising student learning gain. In H. Fry, S. Ketterridge, & S. Marshall (Eds.), A handbook for teaching and learning in higher education: enhancing academic practice (4th ed., pp. 193–208). London and New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315763088

- Gibbs, G., & Dunbat-Goddet, H. (2007). The effects of programme assessment environments on student learning. Higher Education Academy (HEA). Retrieved from https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/gibbs_0506.pdf

- Hillman, N. (2017). Is the TEF a good idea – And will it work? Compass: Journal of Learning and Teaching, 10(2). doi:10.21100/compass.v10i2.530

- Jessop, T. (2017). Fostering educational change through research: Stories from the field. Southampton Solent University. Retrieved from https://www.solent.ac.uk/events/2017/fosteringeducational-change-through-research-stories-from-the-field

- Jessop, T., El Hakim, Y., & Gibbs, G. (2014, June). TESTA in 2014: A way of thinking about assessment and feedback. Educational Developments Issue, 15(2), 2014 SEDA. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/15601591/TESTA_in_2014_A_Way_of_Thinking_About_Assessment_and_Feedback

- Jessop, T., & Tomas, C. (2017). The implications of programme assessment patterns for student learning. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(6), 990–999. doi:10.1080/02602938.2016.1217501

- Jisc (2015).Viewpoints implementation framework, resources and guidance. Retrieved from https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/developing-successful-student-staff-partnerships/viewpoints

- Kerrigan, M.J.P., Walker, S., Gamble, M., Lindsay, S., Reader, K., Papaefthimiou, M.C., … Saunders, G. (2011). The Making Assessment Count (MAC) consortium–Maximising assessment and feedback design by working together’. Research in Learning Technology ALT’s Open Access Journal. doi: 10.3402/rlt.v19s1.7782

- Kuhn, T.S. 1996. The structure of scientific revolutions (3rd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226458106.001.0001 https://www.bibliovault.org/BV.landing.epl?ISBN=9780226458083

- McLean, H. (2018). This is the way to teach: Insights from academics and students about assessment that supports learning. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(8), 1228–1240. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1446508

- Nicol, D. (2007, May 29–31). Principles of good assessment and feedback: Theory and practice. From the REAP International Online Conference on Assessment Design for Learner Responsibility.

- Russell, M., & Bygate., D. (2010). Assessment for learning: An introduction to the ESCAPE project. Blended Learning in Practice, 2010, 38–48.

- Tomas, C., & Jessop, T. (2018). Struggling and juggling: A comparison of student assessment loads across research and teaching-intensive universities. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1463355

- Usher, J. (2014). Demystifying the CAIeRO. Retrieved from http://blogs.northampton.ac.uk/learntech/2014/12/24/demystifying-the-caiero/

- Walker, S., McKenna, D., Abdillahi, A., & Molesworth, C. (2017). Examining predictors of retention with implications for TESTA@Greenwich. The Journal of Educational Innovation, Partnership and Change, 3(1), 122–134. doi:10.21100/jeipc.v3i1.607

- Winstone, N., & Nash, R.A. (2016). The Developing Engagement with Feedback Toolkit (DEFT). HEA Academy. Retrieved from https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/developing-engagement-feedback-toolkit-deft

- Wu, Q., & Jessop, T. (2018). Formative assessment: Missing in action in both research-intensive and teaching focused universities. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(7), 1019–1031. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1426097