ABSTRACT

This study explored the use of video screencasts to supplement written feedback with a small cohort of early-career academics (n = 29) undertaking a postgraduate programme aligned to the UK Professional Standards Framework for teaching in higher education. The aims were to support the academics’ professional development following their summative assessment as well as introducing the technology to inform their own feedback practice. Whilst staff, as learners, were positive about the video feedback, only 50% would consider providing it to their students. They would, however, consider other ways to incorporate video screencasts into their teaching. In addition, the differences between the marks awarded for the first and second assessment were analysed and compared to those of a previous cohort (n = 32) that received written feedback only. The findings would suggest that in spite of positive perceptions about video feedback, there were no differences in performance between the two groups.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

There is a growing body of research exploring the use of technology to improve feedback practices. Whilst the scores for the National Students Survey for assessment and feedback steadily improved during the period 2005–2013 (HEFCE, Citation2014), student satisfaction for these question scales still scored lower than those for the other areas of the survey. Encouraging new and inexperienced lecturing staff, referred to as early-career academics, to foster good teaching practice is the aim of initial professional development teacher training programmes such as postgraduate certificates for staff that teach in higher education. Many of these programmes are aligned to the United Kingdom Professional Standards Framework (UKPSF) which is a set of national standards and expectations outlining what comprises good teaching for effective learning (see Matthews & Pilkington, Citation2019). Assessment and feedback and the use of technology to enhance learning feature as part of the dimensions of practice of the UKPSF. Consequently, to model good practice, academic developers piloted the use of technology to give feedback to early-career academics studying such a programme. The purpose of this study was to add the experience of these early-academics, as learners receiving digital feedback, to the growing body of research around this area and to investigate whether this engagement would encourage them to use the technology with their own students.

Students’ perceptions of the use of technology for receiving feedback

Early studies suggest that audio feedback, as downloadable audio files, increase student satisfaction as students perceive this form of feedback to be clearer, more personal, more extensive and richer than written feedback (King, McGugan, & Bunyan, Citation2008; Merry & Orsmond, Citation2007; Rodway-Dyer, Knight, & Dunne, Citation2011; Rotherham, Citation2007). In addition, studies by Ice, Curtis, Phillips, and Wells (Citation2007) and Lunt and Curran (Citation2010) found that students were more likely to listen and thus engage with this type of feedback. Similar findings were echoed for the use of video technology for receiving feedback (Crook et al., Citation2012; Hyde, Citation2013; Marriott & Teoh, Citation2012), and West and Turner (Citation2016) found that students clearly preferred video (61%) to written feedback (21%) in their study with 299 students.

Proponents of using technology for giving feedback argue that it enables the delivery of high quality and timely feedback as recommended by Gibbs and Simpson (Citation2004) and following a detailed synthesis of meta-analyses including feedback involving more than 7,000 studies, Hattie states that, ‘the most effective forms of feedback provide cues or reinforcement to learners; are in the form of video-, audio-, or computer-assisted instructional feedback; and/or relate to goals.’ (cited in Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007, p. 84).

However, Rodway-Dyer et al. (Citation2011) reported that the main disadvantage of audio-feedback was that students often felt it was difficult to find the point in the essay to which the feedback referred and although students would like more audio feedback, they also wanted written feedback. This preference for the combination was also found by Lees and Carpenter (Citation2012) and Ice, Swan, Diaz, Kupczynski, and Swan-Dagen (Citation2010). Thus the benefit of video technology is that students can see exactly what is being commented on in the assessment (Marriott & Teoh, Citation2012; Whisen, Citation2010). In light of these findings, video rather than audio feedback was provided to the academics in this study, alongside the written feedback that they would normally receive, to enable them to experience the technology.

Staff’s perceptions of using technology to give feedback

Research findings capturing staffs’ perceptions of using technology to provide feedback have been mixed. Positive factors include increased levels of precision and enabling higher quality and quantity of feedback (Hyde, Citation2013; King et al., Citation2008). In addition, some findings suggest that lecturers believed that this type of feedback helped them to be more approachable and they were able to personalize comments to motivate their students (Gould & Day, Citation2013; Hyde, Citation2013; Ice et al., Citation2007; Lees & Carpenter, Citation2012; Nortcliffe & Middleton, Citation2011; Rotherham, Citation2007).

However, Fitzgerald (Citation2011) reported that the most controversial factor for providing a large number of audio feedback recordings (100 +) was whether it was time consuming or time effective. Studies by Rotherham (Citation2007), Ice et al. (Citation2007), Lunt and Curran (Citation2010), Nortcliffe and Middleton (Citation2011), Hyde (Citation2013) and West and Turner (Citation2016) would suggest that staff found it more time effective than writing feedback. However, several studies (King et al., Citation2008; Lees & Carpenter, Citation2012) found that staff thought the process was more time-consuming than giving written feedback and Crook et al. (Citation2012) conclude from their study with 27 staff that video feedback is only practical with low ratios of staff to students but could be used for generic or small-group feedback. In addition, some accessibility problems were also reported (Ice et al., Citation2007; Marriott & Teoh, Citation2012; Merry & Orsmond, Citation2007).

Impact of audio or visual feedback on student performance

Jackel, Pearce, Radloff, and Edwards (Citation2017) argue, ‘while the pedagogical theories behind current consensus on feedback are sound, solid evidence for effectiveness is correspondingly thin’ (Jackel et al., Citation2017, p. 25). These writers have recognized that there have been some studies, albeit with a limited sampling size, that have attempted to remedy this situation. Only a small number of the research studies reviewed above considered the impact of technology on student performance: Nortcliffe and Middleton (Citation2011) reported that it appeared that some students had reflected on their audio feedback; the lecturers in the studies by Fitzgerald (Citation2011) and by Gould and Day (Citation2013) were not convinced that audio feedback had made an impact on their students’ academic work. However, a research study conducted with doctoral students undertaken by Rockinson-Szapkiw (Citation2012) would suggest that the integration of audio and written feedback had a greater impact on learning scores than written feedback only.

Focus of this study

Although this study had a limited sample size, some attempt has been made to measure the impact of video feedback to supplement, rather than replace, written feedback by comparing the performance of the early-career academics that received video feedback with that of a previous cohort that received written feedback only. Thus, based on the review of the literature, this study had three aims:

to explore whether the early-career academics, in their role as learners, found video technology effective for receiving feedback on their own assessments;

to explore whether these academics having received video feedback would consider incorporating the technology into their teaching practice;

to examine whether the use of video feedback improved their performance on the postgraduate teacher training programme compared to that of a previous cohort.

Methods

The early-career academics that took part in this study were new lecturing staff that had less than three years’ teaching experience in higher education. They were studying a 40-credit module of the University’s Postgraduate Certificate in Academic and Professional Practice at a pre-92 university in the Midlands. This 40-credit module was a probationary requirement and mapped to Descriptor 2 of the UKPSF leading to HEA Fellow recognition. Consequently, the module, Learning, Teaching and Assessment, supported participants in developing their knowledge and skills to enable them to undertake their teaching duties effectively.

The 40-credit module took two semesters to complete and comprised two summative assessments undertaken at the end of each semester. The first assessment required the academics to write a reflective account demonstrating that they were developing good teaching practice through critical reflection, as outlined by S D (Citation1995). The second assessment developed from the first through another, albeit slightly longer, reflective account. Written feedback was provided for all the assessments. Whilst both assessments were summative, logically, the feedback received for the first reflective account would be used to develop the second reflective account (Zimbardi et al., Citation2017).

For this study, in addition to written feedback, 29 early-career academics were provided with an individual short screencast video for their first assessment. The free software, Screencast-0-Matic, was used for this purpose as it allowed up to 15 minutes of recording and files could be downloaded onto the University’s virtual learning environment. The software enabled the submitted script to be displayed on screen. The academic developer that had first marked all the assessments displayed each script on screen whilst recording the audio commentary. Prior to this, sections of the script were highlighted so that it was clear what the commentary was referring to. The purpose of the video was to provide specific examples to expand on the written feedback which provided a summary of the work.

Data collection

A self-administered survey was used to collect quantitative and qualitative data to explore the academics’ perceptions of the technology. The survey incorporated an open comment item to collect qualitative comments and a set of closed questions with possible responses being ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘don’t know’ to collect quantitative data.

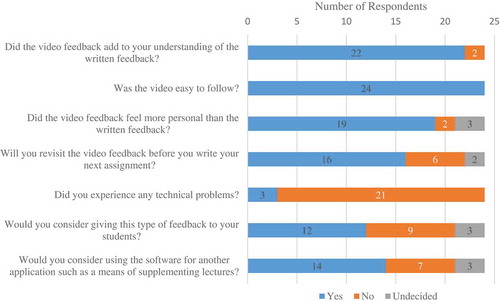

There were seven closed questions on the survey instrument; five were designed to test the findings from the students’ perspective generated by the literature review above. Thus as receivers of the technology to support their own learning, the academics were asked questions focusing on the factors identified: whether the video feedback added to their understanding of the written feedback, was clear and more personal, as well as ascertaining whether any technical problems were experienced. In addition, they were asked if they would revisit the feedback before their next assessment. The remaining two questions focused on the academics’ role as teachers to ascertain whether they would consider giving video feedback to their own students and whether they would incorporate the technology into other areas of their teaching practice (see Appendix).

To investigate whether the supplementary video feedback intervention improved performance, the marks achieved for both assessments were collected and compared with those from the previous year’s cohort that received written feedback only (the control group). For parity and to reduce variables, the assessments for both cohorts (the experimental and control group) were marked by the same assessors. Both assessments were marked out of 100 and each assessment was marked by two markers, who then agreed and provided all the written feedback. In addition, the module was delivered by the same facilitators for each cohort. Ethical approval was granted for the study and the University’s guidelines were followed.

The population

The two groups for the study were of a similar size, gender and from a similar range of disciplines: the group receiving the additional video feedback involved 29 early-career academics (69% female and 31% male). The control group was the previous year’s cohort of 32 early-career academics (53% female and 47% male). The academics that received the additional video feedback comprised 45% from a discipline in life sciences, science, technology, engineering or mathematics (STEM) and 55% from an arts, humanities or social science discipline. The control group comprised 47% from life sciences or STEM with the remaining 53% from the arts, humanities or social sciences. All the early-career academics undertaking the module had less than three years’ teaching experience.

Data analysis

Quantitative and qualitative data was collected through the survey. Content analysis was undertaken to interrogate the qualitative data using ‘information’ units (L S, Citation2009) for the unit of analysis. This involved dividing the qualitative comments into individual concepts expressed in phrases, sentences and, on occasion, paragraphs. Fifteen categories were generated and merged until eight remained. Each information unit was coded to one of the eight categories and the percentage of information units for each category was calculated to ascertain the proportion of comments associated with each. Descriptive analysis was undertaken with the quantitative data collected through the closed questions to compare results with those of the studies outlined in the literature review. Inferential statistics were not required for this element of the study.

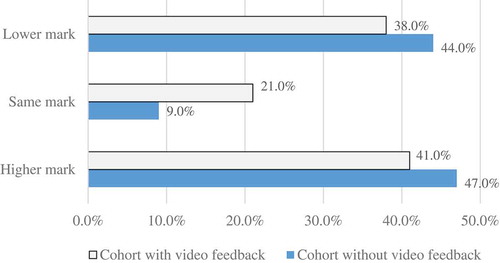

To investigate whether the video screencasts had supported development, the marks awarded for the two assessments submitted by each academic were compared. Since this was a repeated measure design, the data was analysed using the sign test (S) to discern any significant differences. The difference between the two marks was coded as a sign: positive for a higher mark for the second assessment compared to the first; negative for a lower mark for the second assessment than the first, and 0 if the mark was the same for the two assessments. The S statistic was determined by the counts of the less frequent sign. The value for N was the total count for both signs excluding 0. This binomial experiment assumed that the null hypothesis was true (there is no difference) with a probability of 0.5 of the sign being negative and 0.5 of it being positive. This analysis was undertaken with the marks awarded to the academics from both groups – the experimental (n = 29) and the control group (n = 32).

Results

Of the 29 academics that received video feedback, 83% completed the survey. Representative of the cohort, 71% of these respondents were female; 46% came from the life sciences or STEM disciplines and 54% from the arts, humanities or social sciences. Nineteen (79%) respondents (R) responded to the open ended section of the survey and 40 information units were coded to one of eight categories. These categories related to the respondents’ experiences of the video feedback as learners as well as considerations for incorporating this technology in their teaching practice ().

Table 1. Proportion of information units for each category.

Receiving video feedback as learners

The majority (92%) of the respondents to the survey agreed that the video feedback added to their understanding of the written feedback; all the respondents found the video feedback easy to follow; and 79% of respondents thought that this form of feedback felt more personal than the written feedback (). Three respondents (12%) experienced technical difficulties.

The majority of the qualitative responses related to their experiences as learners (72.5% of the information units) and the highest percentage of these comments (27.5%) referred to the process of receiving video feedback which was described as interesting, useful, helpful, clearer, encouraging, engaging, enjoyable and providing depth. In addition, 10% of the comments revealed that the video feedback enhanced the respondents’ understanding of the written feedback and 12.5% related to the perceived positive features of the use of this technology, which included:

… it did help having the tutor talk through different parts of the essay while picking out specific examples. (R18)

Having verbal feedback expands upon the written feedback and makes it feel more like a 1:1 tutorial. (R21)

Highlighting the paragraphs being discussed was really useful. (R20)

It gave real examples of where I could improve my work. (R24)

One respondent supplied a negative feature for using video feedback:

… but it was slightly less positive though as it (necessarily) focused on the areas for improvement. (R24)

The second largest category of responses (20%) compared the use of video feedback to other forms of feedback. One respondent did not feel that video feedback gave much more insight that written feedback (R22) but the remaining respondents that made comparisons were positive, although there were caveats:

I enjoyed it but I feel writing down the feedback is something more permanent and easier to access. (R1)

Although it was very useful, I wouldn’t want it instead of the written feedback. (R3)

The improvement was marginal … as I largely prefer reading to listening/watching. (R19)

The majority (67%) of respondents intended to revisit the feedback before writing the next assessment and one respondent had already re-used the screencast:

I was writing a re-submission so this was particularly important and helpful to me. But I also found it [the video feedback] useful for the writing of my next assignment. (R5)

One respondent explained that the reason why they would not revisit the feedback was because they had made notes about everything said in the video (R3).

The results would suggest that the early-career academics were generally positive about receiving video feedback for their assessment.

Incorporating video technology into own teaching practice

In light of the positive responses to receiving the video feedback in their role as learners, one might assume that this experience would encourage the respondents to consider using this type of feedback with their own students given the benefits: 50% indicated that they might (). There were less comments related to using this technology in their own teaching practice (27.5% of the total number of information units) but respondents that did comment considered the practicalities of providing feedback in this way:

I would try this with my students but I would definitely want to monitor whether they watched it as it is hard enough getting them to read through feedback that we give them already. (R18)

Many of these ideas are great in theory, but I can’t always see whether they are feasible in practice (although I like them!). (R9)

I see this type of software being useful for giving feedback to distance learning students in particular as it gives them contact with the tutor, which is otherwise limited. (R17)

Time would seem to be a factor in considering whether respondents would provide video feedback. Whilst two respondents thought it would be too time consuming, two believed they could save time:

I have 135 students. This type of feedback is great but would be too time consuming. (R7)

Interesting but not something I would use – too resource intensive. (R9)

It is engaging … my only concern as a lecturer is that I would be tempted to listen back and re-record the video a number of times if I thought I had got the tone wrong etc. – but with some practice it might save time overall. (R21)

I would like to trial this technology with students – especially on giving feedback … this is normally relatively time consuming and I think I could achieve more using the video feedback. (R5)

The results of the survey for considering using the technology for other teaching activities were slightly more positive with 58% agreeing that they would. Three respondents provided an indication that they might use the technology to explain an application process, for posting supplementary information in the virtual learning environment and for giving generic feedback.

I had previously looked into using the tool and now seeing it in practice, it has encouraged me to definitely utilise it. (R8)

Impact of video feedback on assessment performance

Whilst 92% of respondents agreed that the video feedback added to their understanding of the written feedback and 100% thought it was easy to follow, 41% of the total cohort (n = 29 including the academics that did not respond to the survey) improved their mark on the second assessment. This result was comparable to the control group’s improvement in marks (47%) that received written feedback only (). However, the result of the sign test (S = 11, N = 23) for this improvement indicated that this was not statistically significant because p > 0.05 (p = 0.16). The result for the control group was also not significant (p = 0.14).

Four second assignments obtained marks in the next grade marking band (i.e. from obtaining a mark between 50-59% for the first assessment to obtaining more than 60% for the second). This was comparable with three second assessments from the control group that received written feedback only.

Discussion

The first aim of this study was to add the experiences of the early-career academics to the literature in this area and indeed, the results would indicate that like the students that received audio feedback in the studies of Rotherham (Citation2007), Merry and Orsmond (Citation2007) King et al. (Citation2008) and Rodway-Dyer et al. (Citation2011) the academics also found technology for receiving feedback to be clearer and more personal as well as being easy to follow. However, whilst the academics were positive about the video feedback, unlike the findings of West and Turner (Citation2016), they did not necessarily prefer this to written feedback. Indeed, there was evidence to suggest that although the video added to their understanding and many comments reinforced the benefits of feedback given in this way, there were indications through the open comments that they might not have been so positive had the academics not received the combination. Whilst it is understandable that a combination of audio and written feedback might be preferred (Ice et al., Citation2010; Lees & Carpenter, Citation2012) to offset the potential difficulty of matching audio comments to written work, it would be worth exploring the reasons if a combination was required with video feedback. It may well be that this is due to study preferences rather than an issue with the technology as indicated by respondents that stated that they had taken notes or preferred written text. Even so, 67% of respondents still said that they would revisit the feedback before writing the next assignment.

Providing the academics with this experience was valuable for encouraging them to evaluate the benefits of this technology and to consider if they would integrate its use into their own practice, which was the second aim of the study. It was interesting that whilst the majority of respondents were positive about receiving this type of feedback as learners and the largest number of comments related to the benefits, only half would consider giving video feedback to their own students. Opinions that were expressed related to the feasibility of doing so and when a factor was indicated, it was the perceived time commitment. Those respondents that stated that they would not consider using video feedback or were concerned about its practicality came from the sciences and had larger student classes that their colleagues. This finding would appear to reflect the results of Crook et al. (Citation2012). However, slightly more respondents would consider using technology in other areas of their teaching practice and indeed one of the respondents was already using podcasts to supplement lectures.

However, since the effectiveness of feedback can only be judged by subsequent performance (see Boud, Citation2007), findings for the third aim of the study indicate that the supplementary video feedback was no more effective than receiving written feedback alone as there was no significant difference between the academics’ performance through this intervention. It is worth noting, however, since the majority of respondents agreed that the screencasts added to their understanding and all agreed that the feedback was clear, by implication the reason for a lack of improvement was not due to the feedback itself, or indeed the technology. This would suggest that other strategies need to be considered to close this apparent learning gap between understanding feedback and being able to apply or develop what students ‘understand’ by it. This might include providing students with multiple opportunities to practice ‘applying’ feedback – preferably through formative assessments – to continue to develop and reinforce the relationship between feedback and performance.

In summary, it would appear that early-career academics experiences of video technology for receiving feedback would support the findings of the reviewed studies. Video feedback can enhance understanding and enables more personalized comments. Therefore, it could potentially build the relationship between student and teacher, which is becoming an increasingly important factor in student satisfaction and retention. However, whether academics choose to use this technology in their practice will depend on the time commitment involved, especially since there is still no evidence to suggest that video feedback can improve student performance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Boud, D. (2007). Reframing assessment as if learning were important. In D. Boud & N. Falchikov (Eds.), Rethinking assessment in higher education. 14–26. Taylor & Francis: London.

- Crook, A., Mauchline, A., Maw, S., Lawson, B., Drinkwater, R., Lundqvist, K., … Park, J. (2012). ‘The use of video technology for providing feedback to students: Can it enhance the feedback experience for staff and students? Computers and Education, 58, 386–396. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2011.08.025

- Fitzgerald, R. (2011) To what extent does a digital audio feedback strategy support large cohorts? Paper presented to: 10th European Conference on e-Learning (ECEL-2011), 10-11 November 2011, Brighton Business School, University of Brighton, Brighton, UK. (Unpublished)

- Gibbs, G., & Simpson, C. (2004). Conditions under which assessment supports students’ learning. Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, 1, 3–31.

- Gould, J., & Day, P. (2013). Hearing you loud and clear: Student perspectives of audio feedback in higher education. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(5), 554–566. doi:10.1080/02602938.2012.660131

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The Power of Feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(81), 81–112. doi:10.3102/003465430298487

- HEFCE. (2014). UK review of the provision of information about higher education NSS results and trends analysis 2005-2013. Retrived from hefce.ac.uk

- Hyde, E. (2013). Talking Results – Trialling an audio-visual feedback method for e-submissions. Innovative Practice in Higher Education, 1, 3.

- Ice, P., Curtis, R., Phillips, P., & Wells, J. (2007). Using asynchronous audio feedback to enhance teaching presence and students’ sense of community. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11, 2.

- Ice, P., Swan, K., Diaz, S., Kupczynski, L., & Swan-Dagen, A. (2010). An analysis of students’ perceptions of the value and efficacy of instructors’ auditory and text-based feedback modalities across multiple conceptual levels. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 43(1), 113–134. doi:10.2190/EC.43.1.g

- Jackel, B., Pearce, J., Radloff, A., & Edwards, D. (2017). Assessment and feedback in higher education: A review of literature for the higher education academy, HEA. Retrived from https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/assessment-and-feedback-higher-education-1

- King, D., McGugan, S., & Bunyan, N. (2008). Does it make a difference? Replacing text with audio feedback. Practice and Evidence of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 3, 2.

- L S, N. (2009). Action research in teaching and learning. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Lees, D., & Carpenter, V. (2012). A qualitative assessment of providing quality electronically mediated feedback for students in higher education. International Journal of Learning Technology, 7, 1. doi:10.1504/IJLT.2012.046868

- Lunt, T., & Curran, J. (2010). Are you listening please? The advantages of electronic audio feedback compared to written feedback. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(7), 759–769. doi:10.1080/02602930902977772

- Marriott, P., & Teoh, L.K. (2012). Using screencasts to enhance assessment feedback: Students’ perceptions and preferences. Accounting Education: an International Journal, 21(6), 583–598. doi:10.1080/09639284.2012.725637

- Matthews, L., & Pilkington, R. (2019). Developing Teaching Standards: A professional development perspective. In E. Roger (Ed.), Handbook of quality assurance for university teaching, 29, 397–408. Abingdon: Routledge/SRHE.

- Merry, S., & Orsmond, P. (2007). Students’ attitudes to and usage of academic feedback provided via audio files. BioScience Education, 11(1), 1–11. doi:10.3108/beej.11.3

- Nortcliffe, A., & Middleton, A. (2011). Smartphone feedback: Using an iPhone to improve the distribution of audio feedback. International Journal of Electrical Engineering Education, 48(3), 280–293. doi:10.7227/IJEEE.48.3.6

- Rockinson-Szapkiw, A. (2012). Should on-line doctoral instructors adopt audio feedback as an instructional strategy? International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 7, 245–258. doi:10.28945/1595

- Rodway-Dyer, S., Knight, J., & Dunne, E. (2011). A case study on audio feedback with Geography undergraduates. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 35(2), 217–231. doi:10.1080/03098265.2010.524197

- Rotherham, B. (2007). Using an MP3 recorder to give feedback on students’ assignments. Educational Developments, 8(2), 7–10.

- S D, B. (1995). Becoming a critically reflective teacher. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- West, J., & Turner, W. (2016). Enhancing the assessment experience: Improving student perceptions, engagement and understanding using on-line video feedback. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 53(4), 400–410. doi:10.1080/14703297.2014.1003954

- Whisen, G. (2010). Student assessment using video feedback. [on-line]. Retrived from http://ideaconnect.edublogs.org/2010/08/14/student-assessment-using-video-feedback/

- Zimbardi, K., Colthorpe, K., Dekker, A., Engstrom, C., Bugarcic, A., Worthy, P., … & Long, P. (2017). Are they using my feedback? The extent of students’ feedback use has a large impact on subsequent academic performance. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(4), 625–644. doi:10.1080/02602938.2016.1174187