?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The Fourth Industrial Age (4IA) is likely to be accompanied simultaneously by an increase in technology-mediated learning and an urgent need for people to learn rapidly, effectively and collaboratively. This study investigates the potential of vicarious learning from videoed tutorials as a pedagogical tool suitable for the challenges of 4IA. Undergraduate Business students observed videos of student tutees responding to tutor prompts as they tackled open-ended and conceptually challenging problems. The results revealed that student observers self-reported: gains in their conceptual understanding from watching videoed tutorials; preferences for watching tutorial dialogues over alternative learning methods; and that watching videoed tutorials had positive impacts on their affect and access to additional learning-related information. The study concludes that vicarious learning from videoed tutorials is an accessible technology-mediated pedagogy that is achievable by mainstream educators and is effective in developing conceptual understanding, engaging students and providing access to additional learning-related information.

Introduction

The Fourth Industrial Age (4IA) will bring with it uncertainties and rapid change, intensifying the need for learning (Xing, Citation2019). It will be a time characterized by rapid change in lives and working practices triggered largely but not exclusively by technological developments (Salmon, Citation2019). Citizens of the 4IA will need to be proficient learners; autonomous, able to work with uncertainty, flexible, creative, and collaborative in their approaches (Lotz-Sisitka, Wals, Kronlid, & McGarry, Citation2015; Salmon, Citation2019). This has implications for education providers. Providers will need to discover pedagogies to support all manner of learning, for increasingly large numbers of students and in situations where knowledge and practices are evolving and the application of problems is open and ill-defined (Brown-Martin, Citation2017). This necessarily has implications for curricula which will need to be rapidly, continuously and flexibly developed.

This study investigates a pedagogy that goes some way to meet the challenges presented by 4IR in that it is scalable, flexible, utilizes ubiquitous technologies and is purported to be effective in developing learning and learning-related capabilities. The research evaluates student observer reactions to opportunities for vicarious learning (Bandura, Citation1986) from videoed tutorials of students learning open-ended, hard-to-grasp concepts.

The paper begins with an account of traditional tutoring and outlines research into the impact of watching videoed tutorials. The theory behind the research is explored, and the knowledge gap, leading to the research questions that guide the present study, is identified. The paper then describes how videoed tutorials were made available to undergraduate business students. Students’ reactions are reported and discussed in light of theory, advances in learning technologies and the current and likely future demands on higher education.

Face-to-face tutoring has long played an important role in higher education, and researchers acknowledge the power of tutorials in bringing about an increase in tutees’ conceptual understanding (Bloom, Citation1984; Muldner, Lam, & Chi, Citation2014). Tutorials also serve to build learning-related skills in dialogue and enquiry which underpin the capabilities graduates need if they are to be equipped for the 4IA (Brown-Martin, Citation2017). Workers note that dialogue (conversational exchange) is an essential component of successful tutoring (Graesser, D’Mello, & Cade, Citation2011; Laurillard, Citation2013), and that tutees should be encouraged to think, explain, question, relate, reflect, collaborate, and discuss (Gholson et al., Citation2009; Graesser et al., Citation2011).

A number of studies have investigated how much student observers learn from watching or observing videos of tutorials (Muldner et al., Citation2014). Encouragingly, watching videos of tutorial dialogues (usually a conversation between a tutor and one or more tutees), has, in some situations, been found to be as effective as being physically present in a tutorial (Chi, Roy, & Hausmann, Citation2008; Muldner et al., Citation2014). Effect sizes, as indicated by the difference brought about by an intervention measured in standard deviations (Bakker et al., Citation2019), approaching 0.8 are reported for learning from observing videoed tutorial dialogues (Muldner et al., Citation2014), which is regarded as substantial and worthy of implementation (Hattie, Citation2008). Researchers have also compared learning from watching videoed tutorial discussions with other similar scalable methods, for example, watching a monologue (usually in the form of a lecture or talk by an expert or tutor). Results, with a few exceptions, reveal that watching a dialogue yields greater learning (Craig, Graesser, Sullins, & Gholson, Citation2004; Craig, Sullins, Witherspoon, & Gholson, Citation2006; Driscoll et al., Citation2003; Muldner et al., Citation2014; Muller, Sharma, Eklund, & Reimann, Citation2007). In short, it seems that student observers watching tutees discussing problems and arriving at solutions learn more than those watching tutor-produced monologues addressing the same issues.

Such a video pedagogy is attractive particularly in the context of changes in demand for learning associated with 4IA. The resource implications are modest, large audiences can be reached by a single skilled tutor with the aid of rudimentary videoing technologies; materials can be readily updated; and most importantly the approach lends itself to open-ended difficult issues where participants discuss, contribute their ideas and co-create. However, many, but not all, studies into vicarious learning from watching videoed tutorials have been undertaken in controlled laboratory conditions where research participants would be obliged to watch carefully prepared videos delivered in tightly controlled conditions. The value of such studies has been questioned with workers arguing in favour of educational research conducted in authentic settings where human agency is valued rather than being regarded as a source of error variance (Wong, Greenhalgh, Westhorp, & Pawson, Citation2012). However, a recent attempt to move this pedagogy out of the laboratory into a teaching setting, providing videoed tutorials on scale to a class of undergraduates, was not successful (Cooper, Ding, Stephens, Chi, & Brownell, Citation2018). There is a need to further evaluate this pedagogy within teaching rather than laboratory settings. It may be that in authentic settings that watching videoed tutorials is for some reason ineffective. Consequently, this research asks:

RQ1 In a teaching setting, to what extent do students report that watching videoed tutorials impacts on their conceptual understanding?

A number of workers suggest that videoed dialogues are simply more interesting, more engaging and, thus, more motivating than monologues and these affect-based outcomes, at least in part, explain the advantage of videoed dialogues over monologues (Stranc & Muldner, Citation2019). This is intuitively appealing; videoed dialogues capture the social aspect of humanity, and are, therefore, more likely to engage student observers and maintain their attention. Relatedly, it has been suggested that student observers may identify with and be inclined to watch videoed tutees who appear to be similar in age and outlook than they are to attend to older and dissimilar lecturers (Fowler & Mayes, Citation1999).

Additional motivation appears to be provided by student observers’ beliefs that the material discussed within tutorials must be relevant and important for their knowledge and success in assessments (Braaksma, Rijlaarsdam, & Van den Bergh, Citation2002; Braaksma, Rijlaarsdam, Van den Bergh, & van Hout-wolters, Citation2004). By contrast, in a videoed lecture there may be few cues that tell student observers what to attend to or what is important. Being exposed to the different and challenging views of others may also result in an affective response which primes learning (Mezirow, Citation1981). Moreover, student observers who watch tutees struggling with concepts benefit from a greater impact on learning than those watching tutees who are very competent, though there is some lack of consistency in findings here (Chan, Burtis, & Bereiter, Citation1997; Monaghan & Stenning, Citation1998; Schunk, Hanson, & Cox, Citation1987). It is likely that such videos increase observers’ confidence, make learning seem achievable and serve to motivate them.

There are few systematic studies of attention, affect and motivation outcomes from observing tutorials but those that exist attest to the importance of maintaining attention and avoiding boredom (Baker, D’Mello, Rodrigo, & Graesser, Citation2010). As Graesser et al. (Citation2011, p. 420) note, research into students’ perceptions of the precursors and outcomes of learning-related affect is ‘conspicuously absent’. Additionally, in controlled laboratory-based studies research participants are socially constrained and opportunities for learning are controlled. It could be that, in teaching settings where students are free to choose how they learn, the comparisons between videoed dialogues and monologues are moot because students elect to learn by other means and do not watch, do not attend to or do not value videoed tutorials. It is important therefore to establish whether, when given options, students choose to attend to videoed tutorials and if they do whether they find them useful and engaging and whether they perceive any influence on their affect, motivation and learning. Therefore, this study asks:

RQ2 In a teaching setting when there is choice and alternative sources of learning do students report watching videoed tutorials and how do they evaluate them particularly in relation to alternatives?

The power of observing dialogues over monologues has been explained by the way it reveals or provides access to information that might be obscured or assumed in monologues. Conversations generally start with an exploration and establishment of shared knowledge (Isaacs & Clark, Citation1987; Tree & Mayer, Citation2008). This shared lexicon or interactive alignment (Ivanova, Horton, Swets, Kleinman, & Ferreira, Citation2020) then shapes subsequent discussions. For monologues, there is no establishment of terminology or shared knowledge and so no mechanism by which the speaker’s lexicon can be influenced by their (less expert) audience and rendered more accessible. Relatedly, Chi, Kang, and Yaghmourian (Citation2017) posit that it is the language of the tutees that makes dialogues a more powerful pedagogical tool than monologues. Their study showed that student observers paid more attention to what tutees were saying than to the tutors because tutees tended to convey their ideas in terms that student observers could easily understand (Chi, Citation2013).

Additionally, it appears that observing dialogues exposes student observers to various perspectives and learning-related behaviours. This means that observers can access multiple analogies, descriptions, opinions and examples, both correct and incorrect. Muller et al. (Citation2007, Citation2008) suggest that showing faulty thinking and explaining why it is incorrect is valuable to the learning experience. This is much more likely to occur in a dialogue than a monologue.

Asking questions and answering them are central activities in tutorial dialogues and researchers argue that this plays a pivotal role in building understanding and meta-cognition (Gholson et al., Citation2009) by making thinking and learning visible (Collins, Brown, & Holum, Citation1991). Craig et al. (Citation2006) explored how using different question types in videoed tutorials affected learning and found that observers who were exposed to deep questions experienced superior learning. Monologues, videoed or otherwise, rarely involve deep questioning.

Chi et al. (Citation2017) point out, that observing tutorial dialogues makes information about appropriate learning behaviours available, which is thought to help student observers model, adapt and develop their own learning skills (Craig, Gholson, Ventura, & Graesser, Citation2000). Such behaviours include elaborating, providing self-explanations, and the ability to discuss sophisticated issues. Researchers have found that the behaviour of students who have previously observed videoed tutorials mirrors those of the tutees in videos they watched (Chi et al., Citation2017; Driscoll et al., Citation2003). This endorses the notion that students access information about complex learning-related behaviours through watching the behaviours of the tutees in videos. In contrast, lecturers delivering monologue explanations or providing demonstrations cannot provide for such modelling and therefore are unlikely to give students the opportunity to learn what to do, to gauge their level of understanding against other students or to see others developing their thinking.

It is not clear whether these accounts of the effectiveness of videoed dialogue will have an impact in authentic teaching settings when students can attend face-to-face tutorials, observe models directly and talk to fellow students in lectures. We therefore ask:

RQ3 Do students observing videoed tutorials in teaching settings report accessing information that they have not gained from alternative sources?

Method

The study context

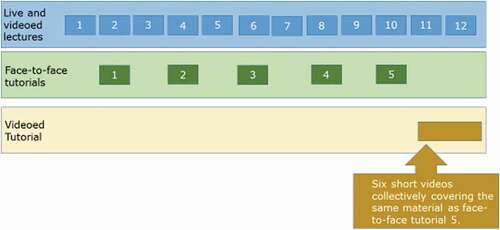

The study took place within a business school at a research-intensive university. Data were collected from students enrolled in a first-year course in Commercial Law during 2019. Data was collected in Semester 1 and 2 with course material and structure being consistent across both semesters. Historically, the course has had a moderately high fail rate (20%–25%) with non-law students finding it difficult to grasp the legal concepts necessary to achieve course learning outcomes. A traditional method is utilised in the course, with face-to-face lectures, focusing on teaching key concepts, being supplemented by a series of readings and face-to-face tutorials composed of a maximum of 16 students. All lectures are recorded and made available to students shortly after live lectures. Five face-to-face tutorials are offered in total during a semester of 12 teaching weeks. Students are graded for participation in face-to-face tutorials and via a mid-semester test and an end of semester exam.

Study design

We followed a treatment as usual (TAU) plus intervention design, an ethical approach that ensures all research participants access the standard best practice treatment (Reynolds et al., Citation2001). This provides a robust test of the intervention in that any impact would be over and above those brought about by the usual course offerings. Students were offered the course as usual and also offered the opportunity to observe a videoed tutorial (See below) as a supplement to the established offerings. All students observing the videos had the opportunity to attend lectures, watch videoed lectures and attend a tutorial covering the content in the videoed tutorial. Ethics approval for this research project was obtained from the University’s Human Participants Ethics committee prior to data collection.

The videoed tutorial

The fifth face-to-face tutorial was selected for videoing on the basis that it covered a challenging topic, involved solving open-ended problems and the application of legal methodology, required the communication of illusive key legal concepts, and tended to elicit student discussion and engagement.

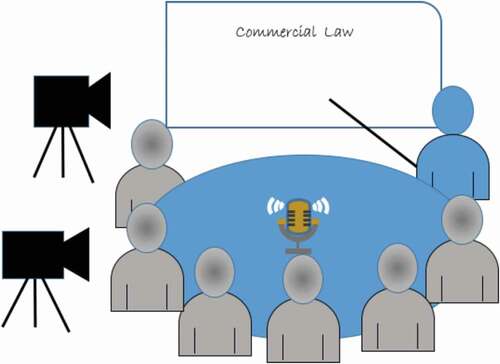

In order to produce the videos, the lead lecturer made an announcement via the course’s learning management system (LMS), asking for students to participate in a research project noting that they would be required to attend a tutorial, that the tutorial would be videoed, and the resultant videos would be made available to the rest of the class. Out of 14 students who responded, six students were selected, based on adequate coursework performance and a history of active participation in face-to-face tutorials.

The six selected students were given an open-ended problem before videoing and asked to prepare, as they would for a face-to-face tutorial. They were not given training or additional instructions, apart from the request to actively participate in the tutorial discussion. The lead lecturer performed the role of tutor and led the tutorial with the intention of eliciting student responses to questions and prompting discussion.

The lecturer was aware that short (5–10 minute) video clips would be produced and therefore structured the tutorial accordingly, with six distinct parts over 50 minutes. Each part corresponded to specific steps that students had to logically and systematically work through in order to fully explore the problem posed. The video was filmed in one take.

Two cameras were operated, one focusing on the six students, and the other on the tutor and whiteboard, which the tutor made extensive use of. A microphone was placed at the centre of the table the students were seated around. After editing, six videos were produced, ranging from approximately four minutes to ten and a half minutes in length (See above).

The procedure

The videoed tutorial, in the form of the 6 short videos, was made available, via the course LMS, in Week 11 of each 12-week semester, giving students approximately three weeks’ access before the final exam.

Students were free to watch none, any or all of the six video clips that made up the videoed tutorial. There were no rewards or participation grades for watching the videoed tutorial nor were students set a task associated with the videos. Students were assured that whether they watched or not would have no bearing on their grades. If they elected to watch the videos, they did so in their own time rather than in class.

Approximately two weeks after the final exam, students who had clicked on the video links were invited to complete a confidential online survey. Invitations were sent via an email and a follow-up reminder on the LMS. Students could rate the items in the survey within 5 minutes. Writing comments and providing feedback took additional time.

The online survey

The online survey was designed by the researchers for the present study. The questions were designed to capture the number of videoed tutorials watched by students, their self-reported level of knowledge before and after watching the videos, their preferences for videoed tutorials over alternative means, the affective consequences and access to additional learning-related information after watching the videos.

Number of videoed tutorials watched

For both semesters, the survey began by providing a list of the video topics and asking students to select the number of videoed tutorials they watched from 0 to 6. This question was designed to prompt students to the key concepts covered by the videoed tutorials that they watched, which helped them in rating their level of knowledge (RQ1) and contributed in part to the attempt to answer RQ2.

Self-reported level of knowledge

For both semesters, the impact of watching videoed tutorials on conceptual understanding (RQ1) was measured by two questions. The first asked students to rate their level of knowledge of the key concepts covered by the videoed tutorials before they watched the videos. The other asked students to rate their level of knowledge after they watched the videos. For both questions, students rated their comprehension on a scale between 1 and 10, with 1 being poor and 10 being excellent.

Preferences for watching videoed tutorials

For both semesters, student preferences for videoed tutorials (RQ2) were measured by asking students to indicate their preferences for information formats being either videoed-tutorial, videoed-lecture or written material.

Affective consequences

In Semester 2, the survey was extended to capture the affective consequences from watching videoed-tutorials (RQ2). Students were asked to rate the extent to which the videoed tutorials contributed to affective consequences, including: being motivated to learn, being more confident in learning the subject, and feeling part of the course. The ratings ranged from 1 to 5, with 1 being definitely not and 5 being a great deal.

Access to learning-related information

In Semester 2, the survey was also designed to capture the informational consequences from watching videoed-tutorials (RQ3). Students were asked to rate the extent to which the videoed tutorials helped them access to additional learning-related information, including: learning how to behave in discussions, ask questions, gauge level of understanding, and understand staff expectations. The ratings ranged from 1 to 5, with 1 being definitely not and 5 being a great deal.

Open ended questions

The survey also included opened-ended questions asking students to describe their learning experience when observing the videoed tutorials and the reasons for their preferences. The responses helped to gain further understanding in relation to RQ2 and RQ3.

The sample

There were 1,842 students enrolled in the course in 2019. In Semester 1, out of 798 students, 384 observed at least one of the available six videos, and in Semester 2, out of 1,044 students, 662 observed at least one, giving a total of 1,046 students who had clicked on at least one of the videos. Of these students, 226 (19%) responded to the survey (84 from Semester 1 and 142 from Semester 2). Thirty-one of the responses were removed from analyses, as answers were incomplete or respondents indicated that they had not watched any videos, giving a total sample of 195 (Semester 1, n1 = 77; Semester 2, n2 = 118). No additional demographic information was gathered.

Analyses

Quantitative data were collated and analysed using SPSS 20. Qualitative responses were analysed in NVivo using qualitative content analysis.

RQ1 was assessed by comparing the differences between level of conceptual understanding, using a related t-test and effect size was assessed by Cohen’s d. A regression analysis was also performed with number of videos watched and initial level of understanding as the independent variables and level of understanding after watching the videos as the dependent variable.

RQ2 was assessed by monitoring the number of videos students watched, by capturing their expressed preferences for alternative sources of learning and calculating descriptive statistics for students’ ratings of affective consequences.

RQ3 was analysed by assessing responses to survey questions asking students to rate the impact of the videos on access to learning-related information. Descriptive statistics and correlations were calculated.

In addition, responses to open-ended questions were analysed to complement quantitative findings in relation to RQ2 and RQ3. The responses were first categorised based on whether they addressed student evaluation of videoed-tutorials (RQ2) or the learning of additional information that was unavailable from alternative materials (RQ3). Then, for each category, an inductive approach was used to code the comments based on the issue they reflected, and the frequency of comment entries under each issue was counted. Finally, exemplar quotes representing the issues under each category were selected and reported.

Results

Each of the research questions is addressed in turn below.

RQ1 In a teaching setting, to what extent do students report that watching videoed tutorials impacts on their conceptual understanding?

The mean score of conceptual understanding prior to watching the videos was 6.17, rising to 8.49 after watching the videos. This difference was significant (Related t = −16.078, p < .001) and the effect size was over 1 which is a substantial effect (Cohen’s d = 1.30; Gates’ delta = 1.1.10).

A stepwise regression showed that self-rated levels of understanding after watching the videos were predicted both by self-rated levels of understanding before watching the videos (β = .399, p < .001) and the number of videos watched (β = .367, p < .001). In combination, they explained 29% of the variance (F2, 192 = 39.235, p < .001). In particular, watching videoed-tutorials explained 13.5% of the variance in self-rated levels of understanding (F1, 192 = 36.38, p < .01). These results indicate that while students perceived that they learnt from watching the videos, differences that existed before watching were not eliminated by exposure to the videos. It also suggests that the more videos students watched the more they gained in understanding.

RQ2 In a teaching setting when students have choice and alternative sources of learning do students report watching videoed tutorials and how do they evaluate them particularly in relation to alternatives?

In Semester 1, of the sample who responded to the survey, approximately half of the cohort watched at least one video, and in Semester 2 this rose to approximately two thirds. Of the sample of 195 students who completed a survey, 9.2% (18/195) viewed 1 or 2 videos, 18% (35/195) watched 3 or 4 videos and 72.8% (142/195) watched 5 or 6 videos. The majority (72.3%) of students reported a preference for watching the videoed tutorials over watching videoed lectures or reading texts. Approximately a quarter of students reported a preference for either watching videoed lectures (17.9%) or for reading texts (9.7%). Students’ evaluative comments were overwhelmingly positive.

The analysis of comments shared by students who completed the survey revealed two over-arching issues, one relating to the nature of the impact of watching the videos and one to the mechanisms that mediated the impact. With regard to the former, students reported improved understanding of content, improved understanding of process and improved affect. In terms of the mechanisms that led to the impact of watching videos, students tended to refer to the dialogue and the accessibility of information.

There were 75 generic positive comments relating to impact with ‘It was very helpful and wish there was one for contract law’(S26); ‘Really helped, other courses should do this too and more often:))’ (S85); and ‘This is an amazing idea to have a videoed tutorial about one of the most significant and hard topics in the course’ (S12) being typical examples. Fourteen students pointed to their effectiveness as a revision tool but did not necessarily explain why they thought the videos were effective, for example, ‘I wouldn’t have known as much as I did in the exam without watching these videos beforehand’ (S27).

In terms of affective consequences, the mean scores of feeling motivated to learn, feeling part of the course and feeling more confident were ,

, and

respectively. These mean scores are almost at ceiling indicating that students are reporting that watching the videos had an appreciable impact on their course related affect.

Responses to the open-ended questions similarly attested to the effect of watching the videos on affective consequences. Twenty-one comments referred to the impact of watching the videos on motivation and confidence. None refereed to feeling part of the course. For example, ‘The videos contained that exact format of a small group with 1 teacher who can teach and bring about arguments and conversations which just makes me motivated and [want to] interact and join in on the arguments’ (S39). Some students commented that the videoed tutorials were engaging suggesting that they were motivated to watch. For example, ‘It keeps me more actively engaged and my understanding thoroughly improved by the end of the video’ (S100); ‘It was very entertaining and informative and really helped me grasp the concepts of negligence’ (S11); and ‘I finished watching the videos feeling very productive and much more knowledgeable about negligence’ (S46).

Collectively these results suggest that students were likely to watch most of the videos if they watched one video, tended to prefer the videos to alternatives and evaluated them positively. Additionally, the positive affective and motivational effects of watching videoed tutorials suggested in the literature were similarly identified by the study participants.

RQ3 Do students observing videoed tutorials in teaching settings report accessing information that they have not gained from alternative sources?

Mean ratings are shown on the diagonal of and were: gauging own level of understanding ; understanding staff expectations

; knowing how to take part in discussions

; knowing how to ask questions

. Correlations between outcomes are significant, positive and in the moderate to strong range (see ).

Table 1. Mean ratings and correlations between information gains, affective outcomes and conceptual understanding

Nineteen students commented explicitly that they accessed information by listening to tutorial dialogue. ‘It was nice having students as they discuss what I would’ve thought which is corrected, plus they ask questions I would be interested in too’ (S9). Similarly, another said ‘It is also good to hear opinions from different students to see there [sic] perspective on a topic etc’ (S9). One student noted that ‘Often information given in conversation is more detailed rather than that given in text and it is more exciting this way as opposed to watching recordings of lectures’ (S57). Other students noted that ‘It [the videoed tutorial] gave a clear outline of how the different content linked together and made what was important clear’ (S35), and another commented that the videoed tutorial was ‘More in depth and person to person’ (S37).

Observing videoed tutorials seems to free students from constraints that might limit their ability to ask for information in face-to-face tutorials. Students may share the same perspectives and queries as the tutees in the video but be unable to articulate their questions in face-to-face situations. ‘I was able to relate to some of the questions the students asked that I did not know how to put into proper words’(S96). Other students noted that they are reluctant to ask questions in class due to potential embarrassment and humiliation when demonstrating a lack of knowledge in front of their peers. However, the tutees in the video were not so shy. ‘The videos did come in useful in a way that I was able to interpret the content from a student’s perspective so I thought this was helpful. The kind of questions students would think of that I don’t normally voice out but the student did in the video and it was corrected’ (S96). Not only did the students share their appreciation for having heard the videoed tutees’ perspectives, they also saw the value in how the tutor responded to the videoed tutees’ questions. ‘It is helpful to see both how other students digest a problem and how the instructor reacts to their answers as it allows you to get a deeper understanding of the content’. One student noted that ‘I prefer to study by myself, but the addition of having tutorial videos to review allows me to understand different points of view from different students, something that I cannot gain by studying by myself’(S74). There was an insightful suggestion of having the same topics videoed from two different tutorial classes to establish different perspectives.

Several students (N = 25) commented on how through the videoed tutorial they accessed information on process as well as content by seeing how other students thought about and tackled the problems they were discussing. One more lengthy comment than most stated, ‘It is helpful seeing others apply knowledge that you have or have forgotten as it helps you to remember not only the theory but the different ways it can be applied and when people get questions wrong, the different ways it cannot be applied. It is helpful to see both how other students digest a problem and how the instructor reacts to their answers as it allows you to get a deeper understanding of the content’(S55). Another students noted that, ‘The tutorial video was great practical application of the theories which really helped cement my understanding and give clarity on how to approach and answer big questions’ (S81), and another said the videos ‘Made my learning experience a lot better and made me feel so much more prepared for exams as it showed the step by step process to answer questions’ (S31).

In addition to commenting on aspects of the tutorial captured in the video students commented on the videos themselves. Most of these comments attested to the value in being able to access information efficiently and when it was required. In particular being able to watch and re-watch the videos was valued (although it should also be remembered that students could also access lecture recordings at will). Students also commented that watching the videos was time efficient as they were focused and required less time than attending a face-to-face tutorial or lecture. Two students commented on the variable quality of face-to-face tutorials and valued having vicarious access to the course lecturer who was the tutor in the videoed tutorial.

Discussion

This study evaluated a scalable and flexible pedagogy demonstrating that it is effective in building self-reported conceptual understanding, engaging students and providing additional learning-related information generally thought of as being best addressed through person-to-person contact. The three most substantial findings in this context are: firstly, students reported substantial conceptual gains as a consequence of watching the videoed tutorial; secondly, students expressed a preference for watching videoed tutorials over alternatives and provided insights into the origins of their preferences; finally, students reported positive impacts on accessing learning-related information from watching videoed tutorials that other course delivery mechanisms had not delivered.

The self-reported gain in conceptual understanding was substantial being in excess of one standard deviation. This is much larger than might be anticipated in a situation where students have already had access to lectures, lecture recording, tutorials and readings on the same subject. However, it should be recognised that this is a self-reported effect. The validity of students’ self-reported learning has been assessed with mixed results (Porter, Citation2013). Zilvinskis, Masseria, and Pike (Citation2017) suggest that students’ self-reports of learning gain are likely to be valid only when students have access to information to judge gain, for example, when the demands on memory are not too great, when there are no consequences associated with self-ratings and when survey question items are easy to understand. This study fulfilled these criteria, nevertheless, multiple measures of outcome would have been preferable since the assessment of learning gain remains contentious (Evans, Kandiko Howson, & Forsythe, Citation2018).

The present study begins to address the gap in research into vicarious learning from tutorials which has not examined whether students would engage in such a technique in a voluntary, non-experimental context. The findings reported here suggest that not only did students watch videoed tutorials when given the opportunity, but they chose to watch videoed tutorials even though they could access multiple alternative learning resources. Additionally, students reported that the videos were engaging and had a positive impact on affect. The importance of these finding should not be underestimated. There is little point producing efficacious pedagogies if students do not appreciate their value and access them. Equally, there is ample evidence that positive affect improves higher-order cognitive performance (Isen, Citation2008).

In an effort to explain why watching videoed tutorial dialogues generally results in superior learning to watching monologues, researchers have identified multiple sources of information that may be available in videoed tutorials. Although this study did not manipulate these sources of information in any purposeful sense, student comments pointed clearly to the value of accessing multiple perspectives, hearing questioning and answers, exposure to errors and corrections and seeing the process of addressing problems. Their responses to the survey confirmed the impact of the videoed tutorials on self-knowledge and understanding of requirements, the outcomes that Yeadon-Lee (Citation2018, p. 363) identifies as a consequence of ‘reflective vicarious learning’.

Students’ positive reactions to the videoed tutorial seemed to derive partly from the tutorial-based nature of the videos and partly from the ways the videos were produced, being short, well structured, clear and focused. It may be here that an explanation of previous unsuccessful attempts to adopt videoed tutorials in teaching settings lies. Cooper et al. (Citation2018) and Ding, Adams, Stephens, Brownell, and Chi (Citation2018), reporting on their use of videoed tutorials in course settings, suggest that students preferred and learnt more from watching monologues. These researchers had one tutee in each video and students who observed the videos reportedly found them confusing, long and disorganised, and said they could not differentiate correct and incorrect responses. The authors also note that the tutees appearing in videos asked relatively few questions. It may well be that failures to replicate laboratory studies in teaching settings reflect differences in the quality of video editing and the nature of the dialogues offered. To this end, we suggest that educators wanting to use videoed tutorials in their teaching should carefully select topics and plan, edit and pilot videoed dialogues to ensure student observers’ learning, affective and informational reactions are positive. Otherwise, the advantages of videoed tutorials are unlikely to emerge.

Theoretical implications and future work

As noted above, most studies on vicarious learning from videoed tutorials are conducted by cognitive scientists within closely controlled systems and by manipulating a limited number of independent variables. Wrigley and McCusker (Citation2019) argue powerfully against such kind of educational research that removes agency, the vagaries of individuality and the richness of the social environment, pointing out that research of this kind misses much that is crucial in the quest to understand and enhance education. The study presented here illustrates the weight of their argument, but it is an initial study. Much remains to be discovered through studies conducted in authentic settings.

It is likely that the various explanations for the advantages of dialogues over monologues offered by cognitive scientists are not in opposition but are complementary, each contributing to the learning advantage and each having implications for the design of videoed tutorials. It should be noted that, this area of research has its foundations in social learning theory (Bandura, Citation1986), which alerts us to the importance of attention, motivation, coding and recall, and preparation for enactment in learning from modelled behaviours. That is, Bandura saw vicarious learning as being a consequence of all these enablers working in conjunction. His thinking would readily explain the failures to replicate in a teaching setting where students were not motivated to learn and where the correct ways to behave or think could not be coded by observers. It may be that future studies draw more explicitly on the totality of the student experience and do so in authentic teaching settings.

Although multiple workers recognise the critical contribution of affect to vicarious learning and allude to the importance of social presence, emotional identification and vicarious social participation, this has not been theoretically or systematically investigated. The present research attests to its importance as a topic for future research.

Finally, the importance of exposure to contrasting perspectives was identified in this and other studies, but it has not been rigorously examined. Marton (Citation2018) and Marton and Pang (Citation2006) offer a theory of learning based on variation, arguing that learners will build conceptual schema via learning about dimensions of concepts that are seen to vary. This approach might provide both a theory and a method through which to investigate the efficacy of vicarious learning from videoed tutorials in teaching settings where variables cannot, and arguably should not, be systematically controlled.

Practical implications for today and the 4IA

Resource constraints and increasing student numbers mean that individual and small group tutoring is becoming difficult to provide in undergraduate teaching (Altbach, Reisberg, & Rumbley, Citation2019). Additionally, it appears that tutors, even when working with small groups or individuals, may not engage students in the kinds of activities that help build conceptual understanding (Graesser, Person, & Magliano, Citation1995). Rather, it is common for tutors to explain, lecture, and ask superficial questions (Graesser & McNamara, Citation2010). Taken together, this means that, for today’s students, engaging in rich, meaningful dialogue with a skilled tutor may be an infrequent occurrence.

If, with the coming of 4IA, technology-mediated learning increases and time spent in face-to-face learning and teaching decreases, then students’ opportunities to learn in this way may diminish further. Within 4IA, it will be critical for students to master conceptual complexities, learn through discussions, ask deep questions and generate ideas. These are capabilities that are traditionally developed in face-to-face situations but not necessarily so, as the pedagogy evaluated here suggests.

However, the technological advances of 4IA should render producing videos easier and more sophisticated ways of engaging learners may emerge (Mayes, Citation2015). The use of 3D technologies may mean that observers can be more socially present in virtual tutorials. In the future, it may be possible to record multiple discussions and for selection and editing to be, to some extent, automated. It should also be possible for students to be engaged in the production and curation of videoed tutorials and discussions.

In short, it would seem that videoed tutorials could well form part of a technologically mediated suite of pedagogies that are suited to the challenges of 4IA.

Limitations

The limitations and strengths of the study derive largely from its execution in a teaching setting rather than a laboratory. From an ethical point of view, it was not possible to provide videoed tutorials in lieu of face-to-face tutorials; they were therefore offered as a supplement and towards the end of the course. This was an ethical and cautious approach but probably reduced the potential impact on learning as student observers had had the opportunity to attend a face-to-face tutorial on the same topic as the videoed one. The other limitation of the study was that the impact data were subjective and the survey was brief. While the paper offers insight into the views of students who responded to the survey, no data are available on those who did not respond. Data were collected within the same survey, and so there may be an artificial level of concordance in the findings (Evans et al., Citation2018).

Conclusions

The paper argues that developing pedagogies that are fluid, flexible and social is essential if learners are to acquire the concepts and learning-related skills needed for 4IA. It sets out to test such a pedagogy using videoed tutorials in a large introductory business course. In an environment where multiple alternative sources of learning were available, a substantial proportion of students watched most of the videos and were overwhelmingly positive about the experience, identifying conceptual, affective and informational gains. The paper provides insight into previous failures to demonstrate that vicarious learning from videoed tutorials is a viable option within mainstream teaching settings. We conclude that vicarious learning from videoed tutorials is an accessible technology-mediated pedagogy that is achievable by mainstream educators and is effective in developing conceptual understanding, engaging students and providing access to additional learning-related information. As such it is worthy of further investigation within authentic teaching settings.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (24.9 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (130.5 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (34.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- Altbach, P.G., Reisberg, L., & Rumbley, L.E. (2019). Trends in global higher education: Tracking an academic revolution. BRILL: Sense Publisher.

- Baker, R., Sj., D’Mello, S.K., Rodrigo, M.M.T., & Graesser, A.C. (2010). Better to be frustrated than bored: The incidence, persistence, and impact of learners’ cognitive–affective states during interactions with three different computer-based learning environments. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 68(4), 223–241. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2009.12.003

- Bakker, A., Cai, J., English, L., Kaiser, G., Mesa, V., & Van Dooren, W. (2019). Beyond small, medium, or large: Points of consideration when interpreting effect sizes. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 102(1), 1–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-019-09908-4

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc.

- Bloom, B.S. (1984). The 2 sigma problem: The search for methods of group instruction as effective as one-to-one tutoring. Educational Researcher, 13(6), 4–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X013006004

- Braaksma, M.A., Rijlaarsdam, G., & Van den Bergh, H. (2002). Observational learning and the effects of model-observer similarity. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(2), 405–415. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.2.405

- Braaksma, M.A., Rijlaarsdam, G., Van den Bergh, H., & van Hout-wolters, B.H.M. (2004). Observational learning and its effects on the orchestration of writing processes. Cognition and Instruction, 22(1), 1–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532690Xci2201_1

- Brown-Martin, G. (2017). Education and the fourth industrial revolution. Groupe Media TFO. Retrieved from https://www.groupemediatfo.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/FINAL-Education-and-the-Fourth-Industrial-Revolution-1-1-1.pdf

- Chan, C., Burtis, J., & Bereiter, C. (1997). Knowledge building as a mediator of conflict in conceptual change. Cognition and Instruction, 15(1), 1–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532690xci1501_1

- Chi, M.T. (2013). Learning from observing an expert’s demonstration, explanations, and dialogues. In J. J. Staszewski (ed), Expertise and skill acquisition: The impact of William G. Chase (pp. 1–27). UK: Taylor and Francis. doi:https://doi.org/10/4324/9780203074541

- Chi, M.T., Kang, S., & Yaghmourian, D.L. (2017). Why students learn more from dialogue-than monologue-videos: Analyses of peer interactions. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 26(1), 10–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2016.1204546

- Chi, M.T., Roy, M., & Hausmann, R.G. (2008). Observing tutorial dialogues collaboratively: Insights about human tutoring effectiveness from vicarious learning. Cognitive Science, 32(2), 301–341. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03640210701863396

- Collins, A., Brown, J.S., & Holum, A. (1991). Cognitive apprenticeship: Making thinking visible. American Educator, 15(3), 6–11.

- Cooper, K.M., Ding, L., Stephens, M.D., Chi, M.T., & Brownell, S.E. (2018). A course-embedded comparison of instructor-generated videos of either an instructor alone or an instructor and a student. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 17(2), ar31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-12-0288

- Craig, S.D., Gholson, B., Ventura, M., & Graesser, A.C. (2000). The Tutoring Research Group: Overhearing dialogues and monologues in virtual tutoring sessions. Intl Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 11, 242–253.

- Craig, S.D., Graesser, A.C., Sullins, J., & Gholson, B. (2004). Affect and learning: An exploratory look into the role of affect in learning with AutoTutor. Journal of Educational Media, 29(3), 241–250. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1358165042000283101

- Craig, S.D., Sullins, J., Witherspoon, A., & Gholson, B. (2006). The deep-level-reasoning-question effect: The role of dialogue and deep-level-reasoning questions during vicarious learning. Cognition and Instruction, 24(4), 565–591. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532690xci2404_4

- Ding, L., Adams, J.A., Stephens, M.D., Brownell, S., & Chi, M.T. (2018). Failure to replicate using dialogue videos in learning: Lessons learned from an authentic course. In J. Kay & R. Luckin (Eds.), Rethinking Learning in the Digital Age: Making the Learning Sciences Count 13th International Conference of the Learning Sciences (ICLS) 2018, Volume 2. London, UK: International Society of the Learning Sciences.

- Driscoll, D.M., Craig, S.D., Gholson, B., Ventura, M., Hu, X., & Graesser, A.C. (2003). Vicarious learning: Effects of overhearing dialog and monologue-like discourse in a virtual tutoring session. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 29(4), 431–450. doi:https://doi.org/10.2190/Q8CM-FH7L-6HJU-DT9W

- Evans, C., Kandiko Howson, C., & Forsythe, A. (2018). Making sense of learning gain in higher education. Higher Education Pedagogies, 3(1), 1–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23752696.2018.1508360

- Fowler, C.J.H., & Mayes, J.T. (1999). Learning relationships from theory to design. ALT-J, 7(3), 6–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v7i3.11554

- Gholson, B., Witherspoon, A., Morgan, B., Brittingham, J.K., Coles, R., Graesser, A.C., … Craig, S.D. (2009). Exploring the deep-level reasoning questions effect during vicarious learning among eighth to eleventh graders in the domains of computer literacy and Newtonian physics. Instructional Science, 37(5), 487–493. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-008-9069-2

- Graesser, A.C., D’Mello, S., & Cade, W. (2011). Instruction based on tutoring. In R. Mayers & P. Alexander (Eds.), Handbook of research on learning and instruction (pp. 408–426). New York: Routledge.

- Graesser, A.C., & McNamara, D. (2010). Self-regulated learning in learning environments with pedagogical agents that interact in natural language. Educational Psychologist, 45(4), 234–244. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2010.515933

- Graesser, A.C., Person, N.K., & Magliano, J.P. (1995). Collaborative dialogue patterns in naturalistic one-to-one tutoring. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 9(6), 495–522. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.2350090604

- Hattie, J. (2008). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. London: Routledge.

- Isaacs, E.A., & Clark, H.H. (1987). References in conversation between experts and novices. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 116(1), 26–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.116.1.26

- Isen, A.M. (2008). Some ways in which positive affect influences decision making and problem solving. Handbook of Emotions, 3, 548–573.

- Ivanova, I., Horton, W.S., Swets, B., Kleinman, D., & Ferreira, V.S. (2020). Structural alignment in dialogue and monologue (and what attention may have to do with it). Journal of Memory and Language, 110, 104052. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2019.104052

- Laurillard, D. (2013). Rethinking university teaching: A conversational framework for the effective use of learning technologies. London: Routledge.

- Lotz-Sisitka, H., Wals, A.E., Kronlid, D., & McGarry, D. (2015). Transformative, transgressive social learning: Rethinking higher education pedagogy in times of systemic global dysfunction. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 16, 73–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2015.07.018

- Marton, F. (2018). Towards a pedagogical theory of learning. In K. Matsushita (Ed.), Deep active learning (pp. 59–77). Singapore: Springer.

- Marton, F., & Pang, M.F. (2006). On some necessary conditions of learning. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 15(2), 193–220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1502_2

- Mayes, J. (2015). Still to learn from vicarious learning. E-Learning and Digital Media, 12(3–4), 361–371. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2042753015571839

- Mezirow, J. (1981). A critical theory of adult learning and education. Adult Education, 32(1), 3–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/074171368103200101

- Monaghan, P., & Stenning, K. (1998). Effects of representational modality and thinking style on learning to solve reasoning problems. In M. A. Gernsbacher & S.J. Derry (eds.), Proceeding of the 20th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society (pp.716-721) . Maweh, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Muldner, K., Lam, R., & Chi, M.T. (2014). Comparing learning from observing and from human tutoring. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(1), 69–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034448

- Muller, D.A., Bewes, J., Sharma, M.D., & Reimann, P. (2008). Saying the wrong thing: Improving learning with multimedia by including misconceptions. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 24(2), 144–155. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2007.00248.x

- Muller, D.A., Sharma, M.D., Eklund, J., & Reimann, P. (2007). Conceptual change through vicarious learning in an authentic physics setting. Instructional Science, 35(6), 519–533. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-007-9017-6

- Porter, S. R. (2013). Self-reported learning gains: A theory and test of college student survey response. Research in Higher Education, 54(2), 201–226

- Reynolds, C.F., Degenholtz, H., Parker, L.S., Schulberg, H.C., Mulsant, B.H., Post, E., & Rollman, B. (2001). Treatment as usual (TAU) control practices in the PROSPECT study: Managing the interaction and tension between research design and ethics. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(6), 602–608. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.466

- Salmon, G. (2019). May the fourth be with you: Creating education 4.0. Journal of Learning for Development-JL4D, 6(2), 95–115.

- Schunk, D.H., Hanson, A.R., & Cox, P.D. (1987). Peer-model attributes and children’s achievement behaviors. Journal of Educational Psychology, 79(1), 54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.79.1.54

- Stranc, S., & Muldner, K. (2019). Learning from videos showing a dialog fosters more positive affect than learning from a monolog. In S. Isotani, E. Millan, A. Ogan, P. Hastings, B. McLaren, R. Luckin (eds) Artificial Intelligence in Education, AIED 2019.Lecture Notes in Computer Science: Vol. (pp.275–280). Springer, Cham.

- Tree, J.E.F., & Mayer, S.A. (2008). Overhearing single and multiple perspectives. Discourse Processes, 45(2), 160–179. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01638530701792867

- Wong, G., Greenhalgh, T., Westhorp, G., & Pawson, R. (2012). Realist methods in medical education research: What are they and what can they contribute? Medical Education, 46(1), 89–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04045.x

- Wrigley, T., & McCusker, S. (2019). Evidence-based teaching: A simple view of “science”. Educational Research and Evaluation, 25(1–2), 110–126. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2019.1617992

- Xing, B. (2019). Towards a Magic Cube framework in understanding higher education 4.0 imperative for the fourth industrial revolution. In M. Khosrow-Pour (Ed.), Handbook of research on challenges and opportunities in launching a technology-driven international university (pp. 107–130). USA: IGI Global. doi:https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-6255-9

- Yeadon-Lee, A. (2018). Reflective vicarious learning (RVL) as an enhancement for action learning. Journal of Management Development, 37(4), 363–371. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-11-2017-0348

- Zilvinskis, J., Masseria, A.A., & Pike, G.R. (2017). Student engagement and student learning: Examining the convergent and discriminant validity of the revised national survey of student engagement. Research in Higher Education, 58(8), 880–903. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-017-9450-6