ABSTRACT

Scrutinising disproportionate media and political attention provided to the ills of the ‘white working-class’, this article examines the framing of their apparent underachievement in education policy and discourse in early post-Brexit vote England. In a political context dominated by anti-immigration and nationalist rhetoric, this article aims to investigate the framing of such underachievement across class, gender and ethnic differentials. To that end, a Critical Frame Analysis was conducted of four policy documents focusing on differences in diagnosis of, and solutions for, ‘white working-class’ underachievement, and of responses to these documents in mainstream newspapers. We contend that the political emphasis on redistributive social justice and identity politics can introduce a logic that can lead to remedies consistent with the idea of interest-divergence emanating from Critical Race Theory (CRT). The article concludes that transformative reform is lacking and communicated outcomes overly focus on ‘white working-class’ boys, obscuring issues common across groups.

Introduction

Upon being confirmed as the new Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Theresa May proclaimed that it was a ‘burning injustice … if you’re a white, working-class boy, you’re less likely than anybody else in Britain to go to University’ (May Citation2016b). While the politically controversial topic of ‘white working-class’ underachievement in education is far from a new idea, there is considerable divide between academics as to whether such a concern is just. For some, ‘white working-class’ educational underachievement is one of contemporary education’s misguided ‘moral panics’ (Archer and Francis Citation2006), yet for others it is a subject that is much warranted (Demie and Lewis Citation2011).

In June 2016, the British electorate voted to leave the European Union after four decades of membership. Analysis of the British vote to leave the EU has somewhat over-simplistically characterised the decision as a consequence of political discontent and the growing voice of the ‘white working-class’ or the ‘left-behind’, as they have been repeatedly referred to (Ford Citation2016). Yet empirical data reveal that the vote to leave the EU was disproportionately delivered by the white middle class (particularly those in southern England), rather than the working classes (Becker, Fetzer, and Novy Citation2017; Bhambra Citation2017). Newspapers, academics and political analysts have frequently reduced the Brexit vote to economic austerity, anti-immigrant sentiment and anti-elite/anti-establishment mindsets, however (Zoega Citation2016; The Guardian Citation2016; Bennett Citation2016). The post-Brexit vote period thus provides a compelling backdrop to prospective education policy in that racial and ethnic undertones were strongly prominent throughout the campaign period, with anti-immigration rhetoric endemic, particularly in the media.

The principal aim of this paper is to build upon the existing body of literature on how the construction of a victimised ‘white working-class’ in education has manifested itself in discourse and policy in the politically charged post-Referendum period during Theresa May’s premiership. The decision to concentrate on this period was motivated by the apparent centrality of concerns regarding, and at the rhetorical level a political pandering to, ‘left behind’ working-classes during Prime Minister Theresa May’s period in office (see e.g. May Citation2016a).It should be noted that while this rhetorical pandering has been far less prominent since Boris Johnson’s tenure as prime minister, Conservative MP Ben Bradley’s recent invocation of May’s ‘burning injustice’ of white working-class boys – specifically, their being sent ‘to the bottom of the pile’ – suggest that concerns live on (Bradley Citation2020).

Some scholarship exists on ‘white working-class’ underachievement, for example, that which deploys a social justice lens (Keddie Citation2015) and critical race theory (Gillborn Citation2010a,b). However, literature has not sought to explore how a redistributive social justice discourse that adopts identity politics can act as a form of interest-divergence. That is, we argue that by portraying education as a zero-sum game, underachievement of ‘white working-class’ boys can be framed as the fault of initiatives targeting girls and ethnic minorities. Thus, solutions in favour of ‘white working-class’ boys may directly compete with the interests of young women and ethnic minorities. We contend that applying Fraser’s notion of status subordination can allow for reforms that target specific aspects of ‘white working-class’ male underachievement that are not limited to this group identity. A focus on status subordination creates space for groups across ethnic, racial and gendered lines to better mobilise in challenging social injustices.

In what follows, we examine the framing of ‘white working-class’ male underachievement in four education policy documents published in England after the Brexit referendum. These documents include Theresa May’s Government’s first policy consultation about education in 2016, followed by two prominent responses to this consultation paper and finally, a report by the Social Mobility Commission. The analysis of the documents is supplemented by an examination of the reception of these documents in mainstream British media. The analysis concentrates on the secondary schooling system in England, the latter in light of the devolution of education policy across the United Kingdom.

Theoretical framework

Theoretically, this research explores the relationship between two separate but interrelated bodies of scholarship: social justice theory and critical race theory, with a focus on redistributive social justice and interest-divergence. Before turning to a discussion of these areas of scholarship, we engage with the notion of the ‘white working-class.’

The ‘white working-class’

The term ‘white working-class’ has been called a sliding signifier (Apple Citation1992), with fluid boundaries defined by context and the writer in question. At times, ‘white working-class’ is presented in popular and political discourse as ‘non-elite’ people, at other times it is used to refer to a (deviant) ‘underclass’ (Gillborn Citation2010b). Such contingent and contradictory deployment illuminates the conceptual slipperiness of the notion of ‘white working-class’ and its political value, that is, its potential to mobilise support around particular issues or conversely, apportions blame to sections of society.

An important example is how the ‘white working-class’ is defined with regard to educational underachievement. Each year in the past decade, ‘white working-class’ boys have ranked in the bottom two ethnic groups (excluding travellers) in terms of GSCEFootnote1-performance, a qualification that is taken by 15 and 16 year olds (The Telegraph Citation2016). Gillborn (Citation2010b) argues that the figures used to define the ‘white working-class’ in educational discourse are ‘conveniently’ inconsistent with other definitions. For example, the educational definition uses students that are recipients of Free School Meals (FSM), which amounts to 15.1% of all pupils (Department for Education (DfE) Citation2016b). However, this categorisation is in stark contrast with the British Social Attitudes Survey 2016 where 60% of UK adults self-identified as working class (National Centre for Social Research (NatCen SR) Citation2016). Gillborn (Citation2010b) asserts that ‘FSM statistics provide the basis for media and political commentators to repeat a view of white “working-class” boys as a racially victimised group who need urgent attention’.

The gendered nature of this discussion is striking, in that, in relation to educational achievement, debates have largely centred on ‘white working-class’ boys (Gillborn Citation2010b; Keddie Citation2015). Engaging with the (enduring) moral panic surrounding academic performance of boys, feminist scholars such as Epstein (Citation1998) and, more recently, Archer and Francis (Citation2006), Smith (Citation2010) and Keddie (Citation2015) have drawn attention to explanatory narratives underpinning debates concerning gender gaps in achievement levels. Epstein (Citation1998) draws a distinction between a discourse of ‘poor boys,’ ‘boys will be boys’ and ‘blaming schools.’ The ‘poor boys’ narrative frames ‘white working-class’ boys as the new marginalised or ‘lost’ (Wigmore Citation2016), whereby their low educational performance is attributed to the ‘crisis of masculinity’ (Keddie Citation2015). The ‘boys will be boys’ discourse celebrates masculinity and highlights young men’s resistance to the ‘feminine’ sphere of the school and its ethos of discipline (Nayak Citation2001; Archer and Francis Citation2006). Finally, the ‘blaming schools’ discourse refers to policy efforts focusing on ‘standards and effectiveness,’ whereby underperforming schools are named and shamed.

The ‘poor boys’ narrative is considered to have been most damaging – casting blame on female teachers and young school going women, and providing grounds for calls for redirecting resources towards young school going men (Reay Citation2002; Archer and Francis Citation2006). Crucial here is the hold the ‘poor boys’ story line has retained on public imagination and, we argue, the ways in which this narrative informed post-Brexit referendum educational discourse and policy in England.

Like ‘white working-class’ underachievement, ‘victimisation’ of white people is not a recent phenomenon (Gillborn Citation2010b; Butler, Gambetti, and Leticia Citation2016; Bhambra Citation2017). Since 2008, portrayals of underachievement have been widespread, featuring in prominent articles in The Telegraph, The Times and The Independent, and programmes such as the BBC’s ‘White Season’ and the Channel 4 documentary series ‘Immigration: The Inconvenient Truth’ (Sveinsson Citation2009; Gillborn Citation2010b). As is now, the source of attention then was reports showing white students in receipt of Free School Meals (FSM) performing worse than any other ethnic group (Gillborn Citation2010b).

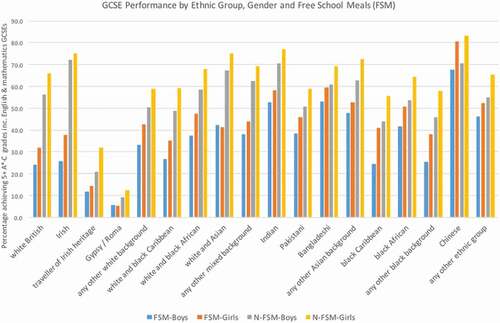

Although it is important to take grievances of ‘white working-class’ members seriously, the common underlying message in political and media discourse is that the ‘white working-classes’ are the ‘losers in the struggle for scarce resources, while minority groups are the winners’ (Sveinsson Citation2009, 5), and that they are disadvantaged on the basis of their ethnicity (Keddie Citation2015). What is discussed to a lesser extent is that intra-ethnic-group class gaps (White Non-FSM vs White FSM) are far more pronounced than inter-ethnic-group or gender gaps (see ). Ultimately, the debate has mostly been positioned around ethnicity, which is often used as an easy explanation of failure (Guinier Citation2004). However, as Sveinsson (Citation2009, 6) has observed, while there are significant levels of discrimination towards white-working-classes, ‘they are not discriminated against because they are white’.

Figure 1. GCSE performance by ethnic group, gender and FSM 2014–15 (adapted from Department for Education (DfE) Citation2016c).

Social justice: redistributive critiques

Distributive principles of justice have featured prominently in equity schooling policy and practice in the UK and other Western contexts (Fraser Citation1999; Keddie Citation2012). Distributive social justice concentrates on relationships between poverty, school attainment, economic deprivation and social discontent. From a distributive perspective, it is generally assumed that these kinds of problems can be resolved through resource redistribution. In the British context, this approach has been evident in policies such as the Ethnic and Minority Achievement Grant (EMAG) initiative and Aiming High programme, which directed extra funds to certain disadvantaged groups, often based on race, ethnicity and gender.

Building on Iris Marion Young (Citation1990) and Fraser (Citation1999), we question the value of a solely redistributive approach to social justice – as Young argues, while equitable distribution of resources is critical, reallocation may do little in tackling structural causes of inequalities. A distributive understanding of power assumes a zero-sum game, and in the context of the ‘white working-class’ this conception perpetuates the view that the ‘white working-class’ are victims of support provided to other ethnic groups (Young Citation1990; see also Keddie Citation2015). Illustrative of this perspective are statements made by Angela Rayner, the former British Labour Party shadow education secretary, that ‘a focus in the educational system on women and minority ethnic groups had perhaps inadvertently had “a negative impact” on the attention paid to white working-class boys’ (in Walker Citation2018). According to Young (Citation1990), a distributive paradigm tends to separate equity issues from their broader context. Through what she terms ‘social atomism’, a distributive discourse ‘enables white victimology’ by largely ignoring the broader privileged status of whites (Keddie Citation2015, 528).

Fraser (Citation1997) views social justice through the lens of ‘parity of participation’, where equity is understood as removing barriers that impede individuals’ capacity to participate in the social world on a par with others. Rejecting identity politics, Fraser argues that a focus on status subordination is a more appropriate strategy for obtaining greater levels of social justice. A focus on status subordination is consistent with the lens of intersectionality: instead of homogenising groups, status subordination entails looking at intersecting areas of difference. In theory, there are many commonalities between the ‘white-working-class’ and ethnic minority communities, and centring on areas of similarity may be more appropriate in challenging unjust socio-economic structures. However, in practice, marginalised groups find themselves on opposing sides of the political debate, aligned in terms of ethnic solidarity rather than collectively confronting common concerns (Guinier Citation2004; Gillborn Citation2010b).

Critical race theory – interest-divergence

Given the emphasis on ethnicity and/or race in debates on educational underachievement of the ‘white working-class’, Critical Race Theory (CRT) offers a crucial framework with which to further examine notions of (redistributive) social justice in and through education. Emerging in part from American critical legal studies in the mid-1970s, CRT situates race at the centre of questions of social inequalities (Donnor Citation2005). Critical race theorists contend that racism must be examined in terms of what Tatum (Citation1997/2003) refers to as a ‘system of advantage’ rather than as a matter of individual prejudice. CRT scholars regard racism and racial inequity as systematic in that they normalise and privilege beliefs, institutional policies and practices that serve to – directly or indirectly – advantage whites at the expense of people of colour (Tatum Citation1997/2003; Donnor Citation2005; Choi Citation2008). Crucially, CRT challenges ahistoricism, emphasising the need to examine racism in its socio-economic and historical context (Matsuda et al. Citation1993; Gillborn Citation2015).

Critical Race Theory was introduced in the field of education by Ladson-Billings and Tate in 1994 (Ladson-Billings and Tate Citation1995). CRT views education as one of the main means by which white privilege and supremacy are maintained and normalised in society (Ladson-Billings and Tate Citation1995; Delgado and Stefancic Citation2000; Guinier Citation2004; Cole Citation2012; Gillborn Citation2014). Within the field of educational research, Parker and Lynn (Citation2002) argue that studies on students of colour have tended to neglect historically disenfranchised groups by disregarding their concerns, and have de-emphasised the racial nature of inequalities by arguing that problems minority students face in schools can be understood by applying a classed and/or gender lens (p. 13).

Parker and Lynn’s critique of educational research is particularly relevant to debates regarding ‘white working-class’ boys’ educational underachievement. That is, while media and political debates in the United Kingdom regarding the ills of ‘white working-class’ boys can be seen to attend to intersections of class, gender and race, in direct contrast with CRT scholars and activists, these debates focus their attention on historically privileged rather than marginalised gender and race.

CRT scholar BellDerrick’s (Citation1980) work on ‘interest-convergence’ and ‘interest-divergence’ are central to discussions within CRT and the present paper. The former refers to the idea that advancements in racial justice are predominately a result of convergence of interests between white power-holders and non-whites (Gillborn Citation2014; Donnor Citation2005). However, the focus of this research is on the lesser cited concept of interest-divergence. Not mutually exclusive from interest-convergence, interest-divergence refers to the position where racial interests are seen to diverge. The concept highlights the psychological wage that poor whites draw from their sense of racial superiority despite continued economic marginalisation (BellDerrick Citation1980; Guinier Citation2004). As Guinier (Citation2004: 10) contends, interest-divergence is central to understanding ‘racism’s ever-shifting yet ever-present structure.’

Interest-divergence asserts that elites often highlight and reinforce this ‘psychological wage’ of poor whites to divert attention from the unequal distribution of resources and power (Guinier Citation2004). In practice, reinforcing the psychological wage could entail portraying poor whites as victims of multiculturalism, apportioning blame regarding socio-economic inequalities to ethnic minorities, and/or using ‘white working-class’ underachievement as an argument against (further) anti-discrimination policies. Gillborn professes that ‘when economic conditions become harder, we can hypothesise that white elites will perceive an even greater need to placate poor whites by demonstrating the continued benefits of their whiteness’ (Citation2014: 30).

Parallels can be drawn with the political and media discourse around ‘white working-class’ underachievement in education, which notably has coincided with an ongoing period of economic struggle for the ‘white working-class’. Runnymede Trust, an independent race equality think tank based in the United Kingdom, asked several prominent thinkers on race, class and inequality to reflect on ‘white working-class’ underachievement. The overriding feeling was that the plight of the ‘white working-class’ is constructed by politicians, anti-immigrant groups and the media, often as the fault of immigrants and minority ethnic groups, which Sveinsson (Citation2009) asserts, allows elites and middle-class commentators to leave the ‘hierarchical and highly stratified nature of Britain out of the equation’ (p.5). With the apparent opportunity for transformational reform presented by the Brexit referendum, CRT thus offers a compelling lens to analyse whether prospective education policy will construe redistributive justice as a means of advancing ‘white working-class’ male interests.

Materials and methods

Context

Although fairly limited in prominence, from an educational perspective, the political battleground during the EU referendum campaign was centred on the idea that the education system was being overburdened by immigrants. Like healthcare and other public services, immigration was framed as affecting access and quality at the expense of ‘natives’. Analysis has shown that those in areas of sustained low economic growth were more likely to vote Leave (Mckenzie Citation2017). The position of Theresa May’s government was in line with the notion of the ‘left behind’ finally voicing their discontent. In her most significant speech on education and social justice, Britain, the great meritocracy, May, for example, asserts that:

Because one thing is clear. When the British people voted in the referendum, they did not just choose to leave the European Union. They were also expressing a far more profound sense of frustration about aspects of life in Britain and the way in which politics and politicians have failed to respond to their concerns. (May Citation2016a)

In this speech, May’s rhetoric leans towards more fundamental change, arguing largely against the constraints that working class families face, including a paucity of good schools in some areas, lacking additional support and an inability to ‘buy’ their way into a school catchment area. Like Gillborn (Citation2010b), May (Citation2016a) emphasises a necessity for improving data to reflect the large segments of population who are not wealthy yet do not qualify for FSM. Despite concerns over the usefulness of FSM as an indicator of socioeconomic disadvantage, it remains a frequently cited class-based data for school, and particularly pupils, performance (Gilborn Citation2010b). FSM eligibility thus often provides the foundations for analyses on ‘white working-class’ underachievement.

Methodology

Critical Frame Analysis (CFA), which is designed to disclose the differing representations that socio-political actors offer about particular policy problems and solutions is deployed in this article (Verloo and Lombardo Citation2007; Meier Citation2008). Methodologically, CFA analyses the framing of problems and solutions based on a set of sensitising questions (Van Der Haar and Verloo Citation2016). Within CFA, a frame understood as an ‘interpretation scheme that structures the meaning of reality’ (Verloo Citation2016: 19). Accordingly, CFA interrogates how particular meanings of reality are constructed and how such meanings shape, promote and sanction certain responses and interventions. In our case, CFA was used to enable the analysis of the ways in which policy problems and solutions were framed in relation to educational achievement of white working-class boys, and to reflect on the implications of these frames for questions of racial justice.

Given the relatively short time period for analysis between the Brexit referendum in June 2016 and the end of Theresa May’s tenure as Prime Minister, there is limited formal policy to analyse. Thus, CFA will be applied to contemplate four policy documents published in 2016 soon after the referendum: a Department of Education consultation paper, a Knowsley Council-commissioned paper, a report by ‘do-tank’ The Sutton Trust and finally, a report written by the bipartisan Social Mobility Commission (SMC). The Department for Education (DfE) consultation paper was selected as it was the first official consultation of the new administration. The other three documents consist of two responses to the consultation paper, in addition to a broader analysis of social mobility; yet, each has additional compelling reasons for their inclusion. Knowsley council is predominately white working-class area but is also the worst performing local educational area in England (Crawford and Morrin Citation2016). Additionally, the text was written by ResPublica, an independent think-tank that has been influential over conservative policy during the last decade (Harding Citation2016b). The Sutton Trust have been influential in social mobility policy in the UK, playing a role in the establishment of the Social Mobility and Childhood Poverty Commission (The Sutton Trust Citation2017). Finally, the SMC is an advisory non-departmental public body, sponsored by the DfE. The SMC assesses progress made towards improving social mobility in the UK, and to that end publishes annual social mobility monitoring reports and more in-depth studies such as the one discussed here.

Drawing on Verloo and Lombardo (Citation2007), Hidalgo and Duarte (Citation2013), and Bustelo and Lombardo (Citation2007), the following sensitising questions () were used to guide the analysis of the four documents:

Table 1. Overview of sensitising questions.

While not necessarily individually or explicitly addressed in the proceeding discussion of results, this set of questions was deemed analytically useful in examining the manner in which the ‘problem’ of ‘white working-class’ underachievement has been framed. Furthermore, deviating from a straightforward CFA, this study also investigates the framing of these policies in the media – both through press releases and media commentary. A summary of the findings of the research is provided in (see annexe).

Table 2. summary of findings.

Results

Schools that work for everyone

The first text that will be discussed is a government consultation paper, Schools That Work for Everyone (STWE), produced by the DfE, launched on 12 September 2016 with a three-month consultation period (Department for Education (DfE) Citation2016a). The consultation outlines government aims to create an education system that caters to all levels of society rather than just a privileged few (ibid). The principal problem established in the text is a broader lack of social mobility, which is blamed on an insufficient number of good school places. In keeping with the latter, the central solution that is proposed relates to opening up school places to children regardless of background. The document largely avoids mentions of specific groups, at least on gendered and ethnic bases, but rather appears to take an approach which is more in line with the notion of ‘status subordination’ insofar that the recommendations are not aimed solely at the benefit of a particular group.

The UK education system has historically been one of great diversity in choice. Authors such as West and Currie (Citation2008) have accused the mixture of fee-paying independent schools, selective grammar schools (schools that determine admission on the basis of examination taken at the ages of 10 and 11), faith schools (selective on basis of religion and occasionally academic performance) and non-selective state schools as being a cause of social segregation and a barrier to social justice. This segregated structure is particularly pertinent given independent, selective and faith schools all outperform non-selective state schools (Department for Education (DfE) Citation2016a, West and Currie Citation2008). While a lot of the concern centres on poor quality schooling in the state system, STWE proposes remedies that increase the number of ‘good school places’ solely through parties external to the non-selective state school system: independent schools, universities, faith schools, and most contentiously, selective grammar schools.

All parts of the education system need to collaborate more to widen opportunity and raise standards in existing schools, in order to contribute to meeting these challenges. Four areas stand out where more could be done: independent schools, universities, selective schools and faith schools. This consultation outlines proposals for change in each of these areas. (Department for Education (DfE) Citation2016a, 10)

The vague nature of the proposals in the SWTE document makes it difficult to clearly position the text as demonstrating interest-divergence. However, considering the context of May’s (Citation2016b) references to ‘burning injustices’ and the broader political environment, some commentators have perceived the STWE proposals to be a response to white working-class underachievement, with an emphasis on ‘white working-class’ boys (The Sunday Times Citation2016; Young Citation2017).

Achieving educational excellence in Knowsley

The Achieving educational excellence in Knowsley report was commissioned by Knowsley Council in Liverpool and written by ResPublica, an independent think-tank (Crawford and Morrin Citation2016). The report was initially completed in June 2016, but was updated in light of the EU Referendum and the new government’s ambitions to expand the selective schooling system. Unlike the STWE document, this document clearly frames the problem of educational underachievement as a ‘white working-class’ issue. Illustrative of this explicit framing is the statement early on in the report that ‘with a predominantly white working-class population and high levels of deprivation, the problem in Knowsley is twofold and negatively reinforcing’ (6).

The authors of the document postulate that being ‘white’ acts as an additional disadvantage, underpinned by two factors. One, that ‘white working-class’ parents are less likely than other ethnic groups to engage in children’s attainment, and secondly, through a lack of exposure to other ethnic and socio-economic groups, low expectations are endemic in areas that are mainly ‘white working-class’ (6). These explanations can be problematic for multiple reasons. First, the explanations homogenise the ‘white working-class’ as a single group. Second, a lack of parental engagement has been positioned as an almost exclusively ‘white working-class’ issue, and third, it fails to consider the ways in which class intersects and can be compounded by other social categories, such as gender.

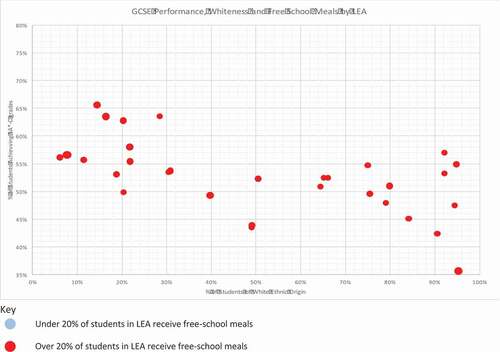

Unpacking this ‘double disadvantage’ of being white and deprived, data on school performance shows that while the two worst performing Local Education Authorities (LEAs) in England are predominately white, of areas where the percentage of children on FSM is in excess of 20%, only four of the ten worst areas have white student populations in excess of 80%. below shows the distribution of LEAs by GCSE performance in relation to the proportion of students in receipt of FSM and the percentage of white students. In particular, bubble sizes represent the percentage of students on FSM, and those with proportions in excess of 20% are highlighted in red. The fact that there is no overly strong correlation between GCSE-performance and percentage of white students, even when areas of high FSM are taken into account does not support the logic of ‘double disadvantage’.

Figure 2. GCSE performance, whiteness and free school meals (adapted from Department for Education (DfE) Citation2016b, Department for Education (DfE) Citation2016c).

The paper’s 33 recommendations are broad. While the recommendations make limited reference to ethnicity but rather to ‘disadvantaged areas’, in a press release concerning the report, Philip Blond, the director of ResPublica, framed the problem as follows:

For too long white working-class children have been left behind by an education system which is not working properly … with a new Education Secretary we have the chance to implement change, not only in Knowsley […], but across the whole of the country. Reintroducing grammar schools is potentially a transformative idea for working-class areas where there are little or no middle classes to game the admission system […].We know that selection improves the performance of those white working-class children selected - the trouble is too few of them are[…]We recommend that new grammars in the first instance are exclusively focused on the needs of white working-class children. (ResPublica Citation2016, emphasis added)

Blond’s solution has gained the most attention in the press. While the report draws no major distinction between boys and girls, media coverage reinforces the moral panic around ‘white working-class’ boys, echoing the ‘poor boys’ narrative (Epstein Citation1998). Illustrative in this regard is the introductory statement to an Espinoza (Citation2016) article in The Telegraph summarising the report as ‘New grammar schools will improve the prospect of white working-class boys in Britain’s worst-performing area.’ In a similar vein, referring to the Knowsley report, Harding and Doyle reporting in the Daily Mail (Citation2016) state that ‘[w]orking-class white boys are the least likely group to gain access to higher education,’ and that the report ‘revealed the difference a grammar school education can make [in] multiplying the chances of this disadvantaged group … ’ (emphasis added). That the above and other social commentary have been published in the Daily Mail (Harding Citation2016a, Citation2016b), the Sun (Davidson Citation2016) and the Telegraph (Espinoza Citation2015, Citation2016; The Telegraph Citation2016) highlight the reach of this discourse into popular thought given they were the most, second-most and fourth-most widely circulated newspapers in the UK during the period that the articles were published (Statista Citation2017).

Class differences: ethnicity and disadvantage

The third document, Class differences: Ethnicity and disadvantage (CD), was released by The Sutton Trust, a UK-based ‘do-tank’ that specialises in improving social mobility in education. Released in November 2016, the 6-page document emphasises the ‘increasing discussion of the low school attainment of disadvantaged white British pupils, particularly boys’ where historically, ethnic minority pupils had faced the greatest educational challenges (Kirby and Cullinane Citation2016, 1). Consideration of intersectionality is much greater in this text – it argues that the ‘well-publicised debates around disadvantaged boys should also not detract from the challenges of other groups and specific ethnic minority groups’ (1). Ultimately, the text frames the problem in terms of ethnic, racial and gendered differences in educational attainment.

Despite the broader and more nuanced focus in this document that identifies cross-group factors such as socio-economic inequalities, levels of aspiration and cultural norms, the policy recommendations are segregated by ethnicity. The first recommendation relates to the implementation of ‘targeted attainment improvement programmes for disadvantaged white British pupils’ (6), whereas the second and third recommendations concern disadvantaged ethnic minority pupils, such as those from black Caribbean and Irish backgrounds. Guided by CFA it is pertinent to consider the context and the voices involved in the production of the CD document. Sir Peter Lampl, the chairman and founder of the Sutton Trust could be accused of feeding into the ‘poor boys’ narrative:

It has been a bad week for white working-class boys. Two new reports show they’re missing out on a good education. (Lampl Citation2015)

We need a more concerted effort with white working-class boys, in particular. (Lampl in Davidson Citation2016)

Furthermore, media coverage has primarily focused on the programmes for ‘disadvantaged white pupils,’ again with particular emphasis on left behind ‘white working-class’ boys (Davidson Citation2016; Harding Citation2016b; Line Citation2016; Weale and Adams Citation2016). Thus, while this final document does not make suggestions that would be detrimental to non-white ethnic groups, the segregation of ‘targeted attainment improvement programmes’ by ethnicity arguably creates a situation whereby different ethnic groups may be set in competition with each other. Statements by Lampl and the media concerning white ‘working-class’ boys not only pit ethnic groups against each other but also boys against girls.

Ethnicity, gender and social mobility

The final document, Ethnicity, Gender and Social Mobility (EGS) was developed by the Social Mobility Commission, a DfE-sponsored non-departmental advisory body. Adopting an intersectional approach, this 66-page document examines how ‘gender, ethnicity and SES interact with education to produce or reduce social mobility’ (Shaw et al. Citation2016, 2), and explores causal factors in and outside schools for gaps found in educational attainment. Referring to the ‘significant’ (2) recent attention dedicated to disadvantaged White British boys’ low educational achievement, the authors observe that – despite low attainment at all educational levels – White British boys face fewer barriers upon entry to the labour market and are more socially mobile than their female, black and Asian Muslim peers.

The document concludes by reiterating that different groups of young people face particular barriers to social mobility at varying educational stages and/or in the transition to the labour market, and offers a series of recommendations for different sets of actors, including schools and policy-makers. Recommendations tend to be disaggregated according to ethnicity, SES and gender, but the authors also identify common challenges, such as access to high-quality pre-schools for children with English as a second language, and those from low-income White British families. In a similar vein, and in keeping with their opening statement, the authors’ first recommendation for policy-makers concerns the importance of not allowing ‘[a]ttention to the “worst” performing groups [to] detract from addressing issues faced by other poorly performing groups’ (50). Disaggregated recommendations could be read as framing needs of different young people in oppositional terms. However, the authors’ intersectional approach and focus on barriers in school access, tiering and setting practicesFootnote2 and teacher assessment at differing educational stages is instead suggestive of an important attempt to draw attention both common obstacles to social mobility and those that are particular to different groups of young people.

Media coverage on this report similarly appears to have been more varied, notwithstanding an Express article which, while acknowledging the SMC finding that other ethnic groups also face social mobility barriers, focuses particularly on the broken ‘British social mobility promise’ to ‘Poor white British boys’ (Hall Citation2015). In other coverage, attention is drawn to structural factors related to poor attainment levels across groups, such as funding cuts to schools, school selection and segregation, and the need for high-quality teachers, especially in the ‘toughest’ schools (Weale and Adams Citation2016).

Discussion

The four documents under consideration offer different perspectives on the English education system. The first three documents discussed here are limited in their discussion of transformative changes to the structure as a whole. First, the STWE consultation paper is superficial in its attempt to suggest which groups are disadvantaged by the current system, but, to its credit, refrains from positioning ‘white working-class’ boys as either the victims of policies favouring ethnic minorities and girls, instead applying a broader focus on all disadvantaged students. However, in its failure to establish a rationale as to why the existing non-selective state school system does not provide adequate quality education, the consultation paper largely proposes redistributive measures without challenging the structural inequalities created by the stratified education system. While the STWE paper does not demonstrate interest-divergence, the proposal of redistributive measures, such as the creation of new selective schools, creates the potential for interest-divergence to emerge.

One manifestation of interest-divergence is evident in the communicated solution of the Knowsley paper. The focus of the paper is constrained by its interpretation of the problem as socio-economic inequalities compounded by ‘whiteness’ in the sense that a lack of parental engagement and an unambitious monoculture are almost exclusively embedded in ‘white working-class’ areas. Gillborn’s (Citation2010b) argument that the term ‘white working-class’ has dual applications, being the ‘non-elites’ or an ‘underclass’, is evident in the case of the Knowsley paper. On the one hand, the paper characterises the ‘white working-class’ as an underclass, suffering from a deficit in aspirations and disinterest in education in comparison to other ethnic and socio-economic groups. On the other hand, the press release portrays the ‘white working-class’ as the non-elite victims of a system that has left them behind (ResPublica Citation2016). Furthermore, the analysis of pupil performance in , found little empirical support of the notion that being ‘white working-class’ was disadvantageous. No clear relationship could be found between predominantly ‘white working-class’ areas and performance.

In the 33 recommendations of the Knowsley paper, the ‘white working-class’ are not mentioned. Rather, recommendation 4 only says that ‘any future grammar schools target the most disadvantaged areas’ (Crawford and Morrin Citation2016, p.34). However, the press release clearly demonstrates interest-divergence by recommending future (selective) grammar schools only target ‘the needs of white-working class children’ (ResPublica Citation2016). The press release and associated media analysis of the Knowsley text can be interpreted as diverting attention away from the broader structural class inequalities that would require transformational reform to the education system. The fact that the results of the report were held back in light of the referendum suggests that an opportunity was seen to politicise the findings in a way not necessarily consistent with its own recommendations.

Removing the restrictions against the formation of new selective schools is a politically controversial topic, which has been intensely argued across the political spectrum for over half a century and continues to be debated (West and Currie Citation2008; Observer Editorial Citation2016; Richardson Citation2018). Proponents of selective education argue that selective schools allow intelligent children from poorer backgrounds to prosper. However, much research acknowledges that the value-added of selective schools is limited, and instead better performance can be attributed to the higher aptitude of students who exhibit higher attainment levels at the time of admission (Morris and Perry Citation2017; Richardson Citation2018). The extent to which the establishment of grammar schools in predominantly ‘white working class’ would improve their educational outcomes is thus debatable.

In comparison to the Knowsley Paper, the ‘Class Differences’ paper does more to provide a holistic view when framing the problem and includes a considerable level of consideration of intersections between gender, ethnicity and class. However, its recommendations are largely redistributive and limited by their ethnic segregation. While the recommendations do not directly favour the ‘white working-class’ versus other ethnic groups, such separation of the recommendations on the basis of ethnicity can leave groups competing for scarce resources. The Social Mobility Commission (Shaw et al. Citation2016), finally, offers a series of recommended actions to reduce social mobility barriers of young people along ethnic, gendered and classed lines. This report goes beyond redistributive measures, recommending action to address, for example, the under-representation of Black Caribbean students in entry to higher tiers of national science and mathematics tests relative to White British students (on this topic, see also Strand Citation2012).

Of particular interest, is that the separate documents have largely avoided entering the debate about the ‘angry’ left-behind ‘white working-class’. However, media focus and communication has sought to add the said political dimension. With respect to the ‘Class Differences’ paper, the media has focused on the recommendations in favour of ‘white working-class’ boys. Furthermore, the ‘Class Differences’ and Knowsley documents do not provide clear distinctions on the basis of gender within their recommendations. However, in line with the ‘poor boys’ narrative, media coverage continues to place more emphasis on ‘white working-class’ boys, emphasising their underperformance relative to other disadvantaged groups, including white working-class girls and ethnic minorities (Espinoza Citation2016; Lampl in Davidson Citation2016; Line Citation2016; Walker Citation2018; Wigmore Citation2016).

Conclusion

The aim of this paper is not to understate or shadow the real issues that face the ‘white working-classes’ but rather to scrutinise how such issues may be used as a political tool that obscures the need for transformational societal change in favour of pitting the ‘white working-classes’, and especially boys, in a zero-sum game against ethnic minorities. Here it is important to again highlight the inconsistencies between rhetoric and policy. Rhetoric, particularly in the media, creates an impression that a need exists for redistributive measures towards the ‘white working-class’ boys. However, in terms of proposed policy solutions, such as the expansion of selective schooling, we argue that such measures do little to transform the more imposing unequal class structures within society. Despite rhetoric concerning social mobility and ‘burning injustices’ (May Citation2016b), excluding the ESG report (Shaw et al. Citation2016), the documents fail to challenge the status quo of an educational system that has long been socially segregated and stratified.

The educational discourse about the ‘white working-class’, and ‘poor boys’, is nothing new. However, Gillborn (Citation2010b) argues that the timing of its prominence in discussions is highly significant. In Gillborn’s case, the headlining of ‘white working-class’ underachievement in late 2008 sought to provide a distraction to the expected scrutiny of neoliberalism in the wake of the financial crisis. In this case, we argue that the rhetoric surrounding the documents must be considered against the context of the political mobilisation of the ‘left-behind’ and the purportedly angry ‘white working-class’ after the Brexit vote. Positioning remedies that are specifically targeted to ‘exclusively … white working-class children’ (Espinoza Citation2016), ‘disadvantaged white British pupils’ (Kirby and Cullinane Citation2016, 6) or, more specifically, ‘lost boys’ (Wigmore Citation2016), creates an image that policy-makers are listening to such discontented voices, without considering the fundamental role of the education system in perpetuating social injustices that affect a variety of disadvantaged young men and women. Ultimately, bringing ethnicity to the forefront of the debate to the exclusion of class, disguises oppressive structures faced by ‘white working-class’ boys, girls and ethnic minorities alike.

Since the Brexit vote there has been limited progress in terms of domestic policy-making, which has meant that our analysis has necessarily been confined to the four policy documents discussed here. Additionally, there has been a succession of different education ministers since the referendum. Given this limited empirical basis, care needs to be taken in drawing conclusions regarding political action taken to address class-based, ethnic and/or gendered disparities in school performance. However, given how the plight of ‘white working-class’ boys is construed in oppositional terms to that of ethnic minorities and girls, we argue that it is critical to continue tracing who evokes the trope of left-behind ‘white working-class’ boys and their educational underachievement, which solutions are proposed at which specific political junctures, and whose interests doing so ultimately serves.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for the valuable feedback on earlier iterations of this paper.

Notes

1. General Certificate of Secondary Education

2. Setting refers to the practice whereby teachers group students in different hierarchical teaching groups for one or, commonly, more subjects. Tiering refers to the allocation of students (by teachers) to separate exam tiers. The tier a student is placed in determines the limits on the grades available; those in the lowest tier cannot attain more than a C. Study at more advanced levels may not be possible for these students as the required grades cannot be awarded in that tier (Gillborn Citation2010a).

References

- Apple, M. W. 1992. “Do the Standards Go Far Enough? Power, Policy, and Practice in Mathematics Education.” Journal for Research in Mathematics Education 23 (5): 412–431.

- Archer, L., and B. Francis. 2006. Understanding Minority Ethnic Achievement: Race, Gender, Class and Success.’. Oxon: Routledge.

- Becker, S. O., T. Fetzer, and D. Novy. 2017. “Who Voted for Brexit? A Comprehensive District-level Analysis.” Economic Policy 32 (92): 601–650. doi:10.1093/epolic/eix012.

- BellDerrick, A., Jr. 1980. “Brown V. Board of Education and the Interest-convergence Dilemma.” Harvard Law Review 518–533.

- Bennett, A. 2016. “Did Britain Really Vote Brexit to Cut Immigration?” Accessed 16 December 2016. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/06/29/did-britain-really-vote-brexit-to-cut-immigration/

- Bhambra, G. K. 2017. “Brexit, Trump, and ‘Methodological Whiteness’: On the Misrecognition of Race and Class.” The British Journal of Sociology 68: S214–S232. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12317.

- Bradley, B. 2020. Accessed 13 March 2020. https://www.politicshome.com/news/uk/education/house/house-magazine/109861/ben-bradley-its-time-give-white-working-class-boys

- Bustelo, M., and E. Lombardo. 2007. Políticas de igualdad en españa y en europa. Madrid: Catedra Ediciones.

- Butler, J., Z. Gambetti, and S. Leticia, eds. 2016. Vulnerability in Resistance. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Choi, J.-A. 2008. “Unlearning Colorblind Ideologies in Education Class.” The Journal of Educational Foundations 22 (3/4): 53–71.

- Cole, M. 2012. “Critical Race Theory in Education, Marxism and Abstract Racial Domination.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 33 (2): 167–183.

- Crawford, E., and M. Morrin. 2016. Achieving Educational Excellence in Knowsley: A Review of Attainment. London: ResPublica.

- Davidson, L. “Poor White Children are the Worst Performing in School and Get Lowest GSCE Results - the Sun. [Cited 12/ 16/2016 2016].” Accessed 16 December 2016. https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/2153574/white-lads-are-the-worst-at-school-and-get-the-lowest-gcse-results-according-to-new-report/

- Delgado, R., and J. Stefancic. 2000. Critical Race Theory: The Cutting Edge. Harvard: Temple University Press.

- Demie, F., and K. Lewis. 2011. “White Working Class Achievement: An Ethnographic Study of Barriers to Learning in Schools.” Educational Studies 37 (3): 245–264.

- Department for Education (DfE). 2016a. Schools that Work for Everyone. https://consult.education.gov.uk/school-frameworks/schools-that-work-for-everyone/supporting_documents/SCHOOLS%20THAT%20WORK%20FOR%20EVERYONE%20%20FINAL.PDF

- Department for Education (DfE). 2016b. Schools, Pupils and Their Characteristics: January 2016. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/schools-pupils-and-their-characteristics-january-2016

- Department for Education (DfE). 2016c. Revised GCSE and Equivalent Results in England: 2014 to 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/revised-gcse-and-equivalent-results-in-england-2014-to-2015

- Donnor, J. K. 2005. “Towards an Interest‐convergence in the Education of African‐American Football Student Athletes in Major College Sports.” Race Ethnicity and Education 8 (1): 45–67. doi:10.1080/1361332052000340999.

- Editorial, O. 2016. “The Observer View on Grammar Schools.” The Guardian 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/sep/10/observer-view-on-grammar-schools

- Epstein, D. 1998. “‘Real Boys Don’t Work: Under-achievement, Masculinity and the Harassment of Sissies.’” In Failing Boys? Issues in Gender and Achievement, edited by D. Epstein, J. Elwood, V. Hey, and J. Maw. Buckingham, (pp. 96-108). UK: Open University Press.

- Espinoza, J. 2015. “Extremists are Setting up Anti-british Schools, Report Claims - Telegraph [Cited 12/ 16/2016 2016].” Acecessed 16 Decmber 2016. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/education/11531140/Extremists-are-setting-up-anti-British-schools-report-claims.html

- Espinoza, J. 2016. “Create New Grammars to Help Poor, White Pupils, Report Commissioned by Labour Council Suggests [Cited 12/ 16/2016 2016].” Accessed 16 December 2016. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/10/31/create-new-grammars-to-help-poor-white-pupils-report-commissione/

- Ford, R. 2016. “Older ‘Left-behind’ Voters Turned against a Political Class with Values Opposed to Theirs.” The Guardian 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/jun/25/left-behind-eu-referendum-vote-ukip-revolt-brexit

- Fraser, N. 1997. Justice Interruptus: Critical Reflections on The’ Postsocialist’ Condition. New York: Cambridge Univ Press.

- Fraser, N. 1999. “Social Justice in the Age of Identity Politics: Redistribution, Recognition, and Participation.” In Culture and Economy after the Cultural Turn, edited by Ray, Larry, and Andrew Sayer, 25-52. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Gillborn, D. 2010a. “Reform, Racism and the Centrality of Whiteness: Assessment, Ability and the ‘New Eugenics’.” Irish Educational Studies 29 (3): 231–252. doi:10.1080/03323315.2010.498280.

- Gillborn, D. 2010b. “The White Working Class, Racism and Respectability: Victims, Degenerates and Interest-convergence.” British Journal of Educational Studies 58 (1): 3–25.

- Gillborn, D. 2014. “Racism as Policy: A Critical Race Analysis of Education Reforms in the United States and England.” Paper Presented at the Educational Forum 78 (1): 26–41.

- Gillborn, D. 2015. “Intersectionality, Critical Race Theory, and the Primacy of Racism: Race, Class, Gender, and Disability in Education.” Qualitative Inquiry 21 (3): 277–287.

- Guinier, L. 2004. “From Racial Liberalism to Racial Literacy: Brown V. Board of Education and the Interest-divergence Dilemma.” The Journal of American History 91 (1): 92–118.

- Hall, W. 2015. “Poor white boys’ are falling behind in education, says social mobility expert”, The Express, Access 15 January 2017. https://www.express.co.uk/news/uk/748013/Poor-white-boys-failing-education-Social-Mobility-Commission

- Harding, E. 2016a. “GCSE Pupils from Poor Chinese Families are Three Times More Likely to Achieve Good Results | Daily Mail Online [Cited 12/ 16/2016 2016].” Accessed 16 December 2016. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3921992/GCSE-pupils-poor-Chinese-families-three-times-likely-achieve-good-results-children-white-working-class-backgrounds.html

- Harding, E. 2016b. “Grammar Schools ‘Can Transform White Working Class Areas’ | Daily Mail Online [Cited 12/ 16/2016 2016].” Accessed 16 December 2016. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3888312/Grammars-transform-white-working-class-areas-Report-says-schools-enable-children-achieve-middle-class-backgrounds.html

- Harding, E., and J. Doyle. 2016. “Grammars Help White Working Class Boys into Top Universities: Pupils are Three Times More Likely to Go to a Russell Group Institution. | Daily Mail Online.” Accessed 16 March 2018. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3899796/Grammars-help-white-working-class-boys-universities-Pupils-three-times-likely-Russell-Group-institution.html#ixzz59ux2sIGu

- Hidalgo, C., and M. Duarte. 2013. “La interseccionalidad en las políticas migratorias de la comunidad de madrid.” Revista Punto Género 3: 167–194.

- Keddie, A. 2012. “Schooling and Social Justice through the Lenses of Nancy Fraser.” Critical Studies in Education 53 (3): 263–279.

- Keddie, A. 2015. “‘We Haven’t Done Enough for White Working-class Children’: Issues of Distributive Justice and Ethnic Identity Politics.” Race Ethnicity and Education 18 (4): 515–534.

- Kirby, P., and C. Cullinane. 2016. Class Differences: Ethnicity and Disadvantage. London: Sutton Trust.

- Ladson-Billings, G., and W. Tate. 1995. “Toward a Critical Race Theory of Education.” Teachers College Record 97 (1): 47–68.

- Lampl, S. P. 2015. “White Working Class Boys - Sutton Trust.” Accessed 3 March 2018. https://www.suttontrust.com/newsarchive/sir-peter-lampl-writes-for-the-sun/

- Line, H. 2016. “Majority of White Working Class Boys Fail to Get Good GCSEs. | Independent.” Accessed 16 March 2018. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/education/education-news/gcses-white-working-class-boys-education-majority-sutton-trust-fail-exam-results-a7408606.html

- Matsuda, M. J., C. Lawrence, R. Delgado, Richard, and K. W. Crenshaw, Eds. 1993. Words that Wound: Critical Race Theory, Assaultive Speech, and the First Amendment. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- May, T. 2016a. “Britain, the Great Meritocracy: Prime Minister’s Speech. [Cited 12/ 16/2016 2016].” Accessed 16 December 2016 https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/britain-the-great-meritocracy-prime-ministers-speech

- May, T. 2016b. “Statement from the New Prime Minister Theresa May. [Cited 12/ 16/2016 2016].” Accessed 16 December 2016 //www.gov.uk/government/speeches/statement-from-the-new-prime-minister-theresa-may

- Mckenzie, L. 2017. “‘It’s Not Ideal’: Reconsidering ‘Anger’and ‘Apathy’in the Brexit Vote among an Invisible Working Class.” Competition & Change 21 (3): 199–210.

- Meier, P. 2008. “Critical Frame Analysis of EU Gender Equality Policies: New Perspectives on the Substantive Representation of Women.” Representation 44 (2): 155–167. doi:10.1080/00344890802079656.

- Morris, R., and T. Perry. 2017. “Reframing the English Grammar Schools Debate.” Educational Review 69 (1): 1–24.

- National Centre for Social Research (NatCen SR). 2016. Social Class: Identity, Awareness and Political Attitudes: Why are We Still Working Class?. British Social Attitudes 33. https://www.bsa.natcen.ac.uk/media/39094/bsa33_social-class_v5.pdf

- Nayak, A. 2001. “Ivory Lives: Race, Ethnicity and the Practice of Whiteness in a Northeast Youth Community.” Paper presented at Economic and Social Research Council Research Seminar series: Interdisciplinary Youth Research: New Approaches. Birmingham University, Birmingham

- Parker, L., and M. Lynn. 2002. “What’s Race Got to Do with It? Critical Race Theory’s Conflict with and Connections to Qualitative Research Methodology and Epistemology.” Qualitative Inquiry 8 (1): 7–22.

- Reay, D. 2002. “Shaun’s Story: Troubling Discourses of White Working-class Masculinities.” Gender and Education 14 (3): 221–234.

- ResPublica. 2016. “White Working Class Education Needs Overhaul To Reverse Cycle Of Failure.” Achieving Educational Excellence in Knowsley – Press Release. Accessed 13 November 2017. http://www.respublica.org.uk/press-centre/press-releases/achieving-educational-excellence-knowsley-press-release/

- Richardson, H. “Grammar School Success ‘Down to Privilege’ - Study - BBC News 2018 [Cited 3/29/2018 2018].” Accessed 29 March 2018. http://www.bbc.com/news/education-43542565

- Shaw, B., L. Menzies, E. Bernardes, S. Baars, P. Nye, and R. Allen. 2016. Ethnicity, Gender and Social Mobility. London: Social Mobility Commission.

- Smith, E. 2010. “Underachievement, Failing Youth and Moral Panics.” Evaluation & Research in Education 23 (1): 37–49.

- Statista. 2017. “UK: Top Selling Newspapers 2017.” Accessed 13 March 2018. https://www.statista.com/statistics/246077/reach-of-selected-national-newspapers-in-the-uk/

- Strand, S. 2012. “The White British‐Black Caribbean Achievement Gap: Tests, Tiers and Teacher Expectations.” British Educational Research Journal 38: 75–101. doi:10.1080/01411926.2010.526702.

- Sveinsson, K. 2009. “The White Working Class and Multiculturalism: Is There Space for a Progressive Agenda.” In Who Cares about the White Working Class, 3–6. London: Runnymede Trust.

- Tatum, B. 1997/2003. ‘Why are All Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?’ and Other Conversations about Race. New York: Basic Books

- The Guardian. 2016. How Did UK End up Voting to Leave the European Union? 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/jun/24/how-did-uk-end-up-voting-leave-european-union

- The Sunday Times. 2016. “Give Mrs May’s Grammars a Fair Hearing | Comment.” Accessed 21 March 2018. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/give-mrs-mays-grammars-a-fair-hearing-336t6z3xm

- The Sutton Trust. “Sutton Trust - about Us [Cited 12/ 16/2016 2016].” Accessed 12 December 2017. http://www.suttontrust.com/about-us/us/

- The Telegraph. “White Working Class Boys Perform Worst at GCSEs, Research Shows [Cited 12/ 16/2016 2016].” Accessed 16 December 2016. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/11/10/white-working-class-boys-perform-worst-at-gcses-research-shows/

- Van Der Haar, M., and M. Verloo. 2016. “Starting a Conversation about Critical Frame Analysis: Reflections on Dealing with Methodology in Feminist Research.” Politics & Gender 12 (3): E9.

- Verloo, M. 2016. “Mainstreaming Gender Equality in Europe. A Critical Frame Analysis Approach.” Επιθεώρηση Κοινωνικών Ερευνών 117 (117): 11–34.

- Verloo, M., and E. Lombardo. 2007. “Contested Gender Equality and Policy Variety in Europe: Introducing a Critical Frame Analysis Approach.” In Multiple Meanings of Gender Equality.A Critical Frame Analysis of Gender Policies in Europe, 21–49. Budapest : Central European University Press.

- Walker, P. 2018. “White Working-class Boys Should Be More Aspirational, Says Labour Minister.” https://www.theguardian.com/education/2018/jan/03/white-working-class-boys-should-be-more-aspirational-says-labour-minister

- Weale, S., and R. Adams. 2016. “Schools Must Focus on Struggling White Working-class Pupils, Says UK Charity.” The Guardian 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2016/nov/10/schools-focus-struggling-white-working-class-pupils-uk.

- West, A., and P. Currie. 2008. “School Diversity and Social Justice: Policy and Politics.” Educational Studies 34 (3): 241–250.

- Wigmore, T. 2016. “The Lost Boys: How the White Working Class Got Left Behind.” New Statesmen, Accessed 10 November 2017. https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/education/2016/09/lost-boys-how-white-working-class-got-left-behind

- Young, I. M. 1990. Justice and the Politics of Difference. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- Young, T. 2017. “Is the Government Right to Shelve Its Grammar School Plans? | CPG | Towards a Thoughtful Conservatism.” Accessed 13 March 2018. https://conservativephilosophy.org/is-the-government-right-to-shelve-its-grammar-school-plans/

- Zoega, G. 2016. On the Causes of Brexit: Regional Differences in Economic Prosperity and Voting Behavior. Vox EU. https://voxeu.org/article/brexit-economic-prosperity-and-voting-behaviour