Abstract

Freshwater mussels (Bivalvia, Unionida) play essential roles in the well-functioning of ecosystems, even providing essential services to humans. However, these bivalves face numerous threats (e.g. habitat loss and fragmentation, pollution, introduction of invasive species, and climate change) which have already led to the extinction of many populations. This underscores the need to fully characterize the biology of these species, particularly those, such as Potomida acarnanica, that are still poorly studied. This study presents the first mitogenome of P. acarnanica (Kobelt, 1879), an endemic species of Greece with a distribution limited to only two river basins. The mitochondrial genome of a P. acarnanica specimen, collected at Pamisos River (Peloponnese, Greece), was sequenced by Illumina high-throughput sequencing. This mitogenome (16,101 bp) is characterized by 13 protein-coding genes, 22 transfer RNA and 2 ribosomal RNA genes. The size of this mitogenome is within the range of another Potomida mitogenome already published for the species Potomida littoralis. In the phylogenetic inference, P. acarnanica was recovered as monophyletic with P. littoralis mitogenome in the Lamprotulini tribe, as expected. This genomic resource will assist in genetically characterizing the species, potentially benefiting future evolutionary studies and conservation efforts.

Keywords:

Introduction

Freshwater mussels play a crucial role in maintaining the health and balance of aquatic ecosystems (Strayer Citation2014). These mollusks contribute to nutrient cycling and act as nature’s water purifiers, filtering and cleansing the water they inhabit, helping to sustain a diverse array of aquatic life and supporting the overall health of freshwater ecosystems (Lopes-Lima et al. Citation2017; Vaughn Citation2018). Additionally, they also hold cultural and economic importance, as they have been used historically for food, tools, and even as sources of pearls (Strayer Citation2017; Zieritz et al. Citation2022). Nevertheless, freshwater mussel populations face numerous threats, such as habitat loss and fragmentation, pollution, introduction of invasive species, and climate change, underscoring the urgency of conservation efforts to safeguard these vital organisms and the ecosystems they inhabit (Ferreira-Rodríguez et al. Citation2019; Lopes-Lima et al. Citation2023). In fact, several freshwater mussel species, especially those that are less abundant and have restricted ranges, are now extinct or highly threatened (Lopes-Lima et al. Citation2018).

In the Mediterranean region, where freshwater mussel species endemism is high, their habitats are especially affected by water scarcity with the climate crisis and water over-exploitation exacerbating the situation. The Greek endemic Potomida acarnanica (Kobelt, 1879) is restricted to only two Greek river basins, i.e., Pamisos and Acheloos, that are affected by several anthropogenic pressures (Froufe et al. Citation2016; Skoulikidis et al. Citation2022). Due to its limited distribution, this poorly known species is at high risk of extinction.

Materials and methods

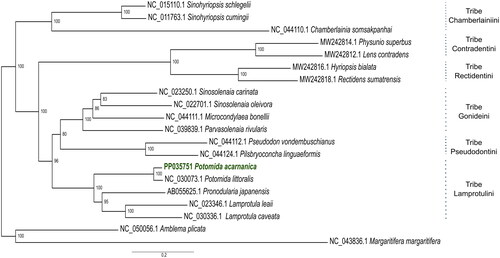

A specimen of P. acarnanica was collected on 27th September 2014 at Pamisos River (Peloponnese, Greece) (37.123287, 21.990056) by Manuel Lopes-Lima (). The voucher specimen has been deposited at the Museum of Natural History and Sciences of the University of Porto, Portugal (https://mhnc.up.pt/, Manuel Lopes-Lima, [email protected]) with voucher name MHNC-UP BIV1121. Genomic DNA was extracted from foot tissue following a standard high-salt protocol (Sambrook et al. Citation1989). The extracted genomic DNA was sent to the Deakin Genomics Center (Melbourne, Australia) for Illumina Paired-End (PE) library construction (2x150bp) and whole genome sequencing using a MiSeq Illumina platform. Mitogenome assembly was obtained using NOVOPlasty (v.4.2) (Dierckxsens et al. Citation2017) and annotation was conducted using MITOS2 web server (Bernt et al. Citation2013, Al Arab et al. Citation2017, Donath et al. Citation2019) with default parameters. Burrows–Wheeler Aligner v.0.7.17-r1198 (Li Citation2013) was used to create the coverage plot by mapping the PE reads to the final assembly, the respective graphical plot was generated using bam2plot (https://github.com/willros/bam2plot) (Supplementary Figure 1). Seventeen mitogenome sequences (NC_015110.1, NC_011763.1, NC_044110.1, MW242814.1, MW242812.1, MW242816.1, MW242818.1, NC_023250.1, NC_022701.1, NC_044111.1, NC_039839.1, NC_044112.1, NC_044124.1, NC_030073.1, AB055625.1, NC_023346.1, NC_030336.1) from the Unionidae family (Gonideinae subfamily), were retrieved from GenBank (22nd December 2023). Moreover, two mitochondrial genomes (from Amblema plicata (NC_050056.1) and Margaritifera (NC_043836.1)) were downloaded from Genbank (22nd December 2023) as outgroup. The 13 protein-coding genes of the downloaded mitochondrial genomes were aligned, trimmed and concatenated with MAFFT (default parameters) (version 7.505) (Katoh and Standley Citation2013), trimAL (version 1.2) (-gt 0.5) (Capella-Gutiérrez et al. Citation2009) and FasConCAT-G (-p -p -a -s -l) (version 1.05.1) (Kück and Longo Citation2014), respectively. The final alignment had 11148 bp. IQ-TREE (version 1.6.12) (-m TESTNEWMERGE -rcluster 10) (Nguyen et al. Citation2015; Kalyaanamoorthy et al. Citation2017) was used to identify the partition-scheme, best-fit nucleotide substitution models and Maximum Likelihood phylogeny. The evolutionary models applied were TPM3 + F + I + G4 (ATP6), TPM3u + F + I + G4 (ATP8), TN + F + I + G4 (COIII), TN + F + I + G4 (COII), TIM3 + F + R4 (COI and ND4L), TPM3u + F+R4 (Cytb, ND1 and ND2), K3Pu + F + I + G4 (ND3), GTR + F+R4 (ND4 and ND5), and TVM + F + I + G4 (ND6).

Results

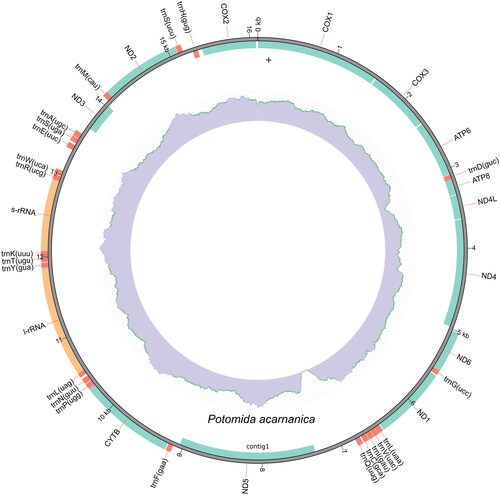

The mitogenome of P. acarnanica, with a total of 16,101 bp, has 13 protein-coding genes, 22 transfer RNA (tRNA), and 2 ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes (). Twenty six of these genes are in the complementary strand (ND1 (NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1), ND2 (NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2), ND6 (NADH dehydrogenase subunit 6), cytochrome b (CYTB), 12S ribosomal RNA, 16S ribosomal RNA and 20 tRNA (tRNAGly, tRNALeu, tRNAVal, tRNAIle, tRNACys, tRNAGln, tRNAPhe, tRNPro, tRNAAsn, tRNALeu, tRNATyr, tRNAThr, tRNALys, tRNAArg, tRNATrp, tRNAGlu, tRNASer, tRNAla, tRNAMet and tRNASer). This mitochondrial genome has been deposited in Genbank with accession number PP035751.

Figure 2. Mitogenome map of P. acarnanica. This plot was created with the annotation model of MITOZ. The outermost track displays the gene features and their strand positioning on the assembly. The color scheme are red for tRNA, green for PCGs, and orange for rRNAs. The Middle track represents read depth distribution across the assembly. The innermost track represents GC content distribution across the assembly.

In the phylogeny here provided, 17 mitogenomes of the subfamily Gonideinae (Unionidae family) are divided according to six tribes with high support (). P. acarnanica and Potomida littoralis are recovered as monophyletic and sister to Lamprotula caveata, Lamprotula leaii and Pronodularia japanensis (), all these five species belong to the Lamprotulini tribe ().

Figure 3. Maximum Likelihood Phylogenetic inference with all the downloaded mitogenomes (n = 19) and with the new mitochondrial genome of P. acarnanica (this mitogenome has been deposited in Genbank with accession number PP035751). The mitogenomes used in this phylogeny were: Sinohyriopsis schlegelii (NC_015110.1) (Sheng et al. Citation2014), Sinohyriopsis cumingii (NC_011763.1) (unpublished), Chamberlainia somsakpanhai (NC_044110.1) (Froufe et al. Citation2020), Physunio superbus (MW242814.1) (Zieritz et al. Citation2021), Lens contradens (MW242812.1) (Zieritz et al. Citation2021), Hyriopsis bialata (MW242816.1) (Zieritz et al. Citation2021), Rectidens sumatrensis (MW242818.1) (Zieritz et al. Citation2021), Sinosolenaia carinata (NC_023250.1) (Huang et al. Citation2013), Sinosolenaia oleivora (NC_022701.1) (Huang et al. Citation2015), Microcondylaea bonellii (NC_044111.1) (Froufe et al. Citation2020), Parvasolenaia rivularis (NC_039839.1) (unpublished), Pseudodon vondembuschianus (NC_044112.1) (Froufe et al. Citation2020), Pilsbryoconcha linguaeformis (NC_044124.1) (Froufe et al. Citation2020), Potomida littoralis (NC_030073.1) (Froufe et al. Citation2016), Pronodularia japanensis (AB055625.1) (unpublished), Lamprotula leaii (NC_023346.1) (unpublished) and Lamprotula caveata (NC_030336.1) (unpublished). The two outgroup taxa used were: Amblema plicata (NC_050056.1) (Teiga-Teixeira et al. Citation2020) and M. margaritifera (NC_043836.1) (Gomes-dos-Santos et al. Citation2019).

Discussion and conclusions

To date, only two mitochondrial genomes of Potomida have been available: the male (M-type) and female (F-type) mitogenomes of Potomida littoralis (Froufe et al. Citation2016b). This is the first complete F-type mitochondrial genome of P. acarnanica. The sex was determined using histology and this mitogenome presents the same F-type gene arrangement of this particular subfamily of Unionidae (Froufe et al. Citation2020). The single published F-type mitogenome of P. littoralis was 15,789 bp in length, similar to the length of the one presented here for P. acarnanica (16,101 bp). As expected, in the provided phylogenetic inference (), the mitogenome of P. acarnanica is grouped with that of P. littoralis. This phylogeny is congruent with other phylogenetic reconstructions of the Gonideinae subfamily (Froufe et al. Citation2020). M-type mitochondrial DNA has been independently evolving from the F-type since the origin of the Unionida order thus they will be far more divergent than any F-type mitogenome of any Unionidae species included in the phylogenetic analysis (Froufe et al. Citation2016b). Given this divergence, only F-type mitochondrial sequences were included in the phylogenetic reconstruction.

For the Potomida genus, there is still a lack of molecular data. Potomida acarnanica is a poorly studied freshwater mussel associated with a high risk of extinction. Genomic resources are essential in evolutive studies and conservation management strategies (Garrison et al. Citation2021). Therefore, we present the first mitogenome of P. acarnanica. This will aid in the comprehensive genetic profiling of the genus and the development of conservation measures for this species.

Author contributions

EF and MLL designed and planned the study. Sample collection was performed by IK and SZ. DNA extraction performed by AGS. Mitogenome assembly and annotation were performed by MLL and AGS, and phylogenetic analysis by AM. Figures prepared by AT, SV, and RS. Draft preparation by AM, AGS, MLL, and EF. All authors interpreted and discussed the data and contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical approval

The described work was approved by the CIIMAR Ethical Committee and CIIMAR Managing Animal Welfare Body (ORBEA), according to the European Union Directive 2010/63/EU. Permits for fieldwork were acquired from local coauthors, no permits were required for collecting invertebrate specimens. The voucher specimen has been deposited at the Museum of Natural History and Sciences of the University of Porto, Portugal (https://mhnc.up.pt/, Manuel Lopes-Lima, [email protected]) with voucher name MHNC-UP BIV1121.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (93.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download JPEG Image (350.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The genome sequence data that support the findings of this study are openly available in GenBank of NCBI at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov under the accession number PP035751. The associated BioProject, SRA, and Bio-Sample numbers are PRJNA1056157, SRR27332421 and SAMN39090842 respectively.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Al Arab M, Zu Siederdissen CH, Tout K, Sahyoun AH, Stadler PF, Bernt M. 2017. Accurate annotation of protein-coding genes in mitochondrial genomes. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 106:209–216. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2016.09.024.

- Bernt M, Donath A, Jühling F, Externbrink F, Florentz C, Fritzsch G, Pütz J, Middendorf M, Stadler PF. 2013. MITOS: improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 69(2):313–319. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2012.08.023.

- Capella-Gutiérrez S, Silla-Martínez JM, Gabaldón T. 2009. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 25(15):1972–1973. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348.

- Dierckxsens N, Mardulyn P, Smits G. 2017. NOVOPlasty: de novo assembly of organelle genomes from whole genome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 45(4):e18. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw955.

- Donath A, Jühling F, Al-Arab M, Bernhart SH, Reinhardt F, Stadler PF, Middendorf M, Bernt M. 2019. Improved annotation of protein-coding genes boundaries in metazoan mitochondrial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 47(20):10543–10552. doi:10.1093/nar/gkz833.

- Ferreira-Rodríguez N, Akiyama YB, Aksenova OV, Araujo R, Christopher Barnhart M, Bespalaya YV, Bogan AE, Bolotov IN, Budha PB, Clavijo C, et al. 2019. Research priorities for freshwater mussel conservation assessment. Biol Conserv. 231:77–87. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2019.01.002.

- Froufe E, Bolotov I, Aldridge DC, Bogan AE, Breton S, Gan HM, Kovitvadhi U, Kovitvadhi S, Riccardi N, Secci-Petretto G, et al. 2020. Mesozoic mitogenome rearrangements and freshwater mussel (Bivalvia: Unionoidea) macroevolution. Heredity (Edinb). 124(1):182–196. doi:10.1038/s41437-019-0242-y.

- Froufe E, Gan HM, Lee YP, Carneiro J, Varandas S, Teixeira A, Zieritz A, Sousa R, Lopes-Lima M. 2016b. The male and female complete mitochondrial genome sequences of the Endangered freshwater mussel Potomida littoralis (Cuvier, 1798) (Bivalvia: Unionidae). Mitochondrial DNA A DNA Mapp Seq Anal. 27(5):3571–3572. doi:10.3109/19401736.2015.1074223.

- Froufe E, Prié V, Faria J, Ghamizi M, Gonçalves DV, Gürlek ME, Karaouzas I, Kebapçi Ü, Şereflişan H, Sobral C, et al. 2016. Phylogeny, phylogeography, and evolution in the Mediterranean region: news from a freshwater mussel (Potomida, Unionida). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 100:322–332. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2016.04.030.

- Garrison NL, Johnson PD, Whelan NV. 2021. Conservation genomics reveals low genetic diversity and multiple parentage in the threatened freshwater mussel, Margaritifera hembeli. Conserv Genet. 22(2):217–231. doi:10.1007/s10592-020-01329-8.

- Gomes-dos-Santos A, Froufe E, Amaro R, Ondina P, Breton S, Guerra D, Aldridge DC, Bolotov IN, Vikhrev IV, Gan HM, et al. 2019. The male and female complete mitochondrial genomes of the threatened freshwater pearl mussel Margaritifera (Linnaeus, 1758) (Bivalvia: Margaritiferidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 4(1):1417–1420. doi:10.1080/23802359.2019.1598794.

- Huang X-C, Rong J, Liu Y, Zhang M-H, Wan Y, Ouyang S, Zhou C-H, Wu X-P. 2013. The complete maternally and paternally inherited mitochondrial genomes of the endangered freshwater mussel Solenaia carinatus (Bivalvia: Unionidae) and implications for Unionidae taxonomy. PLoS ONE. 8(12):e84352. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084352.

- Huang XC, Zhou CH, Ouyang S, Wu XP. 2015. The complete F-type mitochondrial genome of threatened Chinese freshwater mussel Solenaia oleivora (Bivalvia: Unionidae: Gonideinae). Mitochondrial DNA. 26(2):263–264. doi:10.3109/19401736.2013.823190.

- Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TK, Von Haeseler A, Jermiin LS. 2017. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat Methods. 14(6):587–589. doi:10.1038/nmeth.4285.

- Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 30(4):772–780. doi:10.1093/molbev/mst010.

- Kück P, Longo GC. 2014. FASconCAT-G: extensive functions for multiple sequence alignment preparations concerning phylogenetic studies. Front Zool. 11(1):81. doi:10.1186/s12983-014-0081-x.

- Li H. 2013. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv:1303.3997v2 [q-bio.GN].

- Lopes-Lima M, Burlakova LE, Karatayev AY, Mehler K, Seddon M, Sousa R. 2018. Conservation of freshwater bivalves at the global scale: diversity, threats and research needs. Hydrobiologia. 810(1):1–14. doi:10.1007/s10750-017-3486-7.

- Lopes-Lima M, Reis J, Alvarez MG, Anastácio PM, Banha F, Beja P, Castro P, Gama M, Gil MG, Gomes-dos-Santos A, et al. 2023. The silent extinction of freshwater mussels in Portugal. Biol Conserv. 285:110244. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2023.110244.

- Lopes-Lima M, Sousa R, Geist J, Aldridge DC, Araujo R, Bergengren J, Bespalaya Y, Bódis E, Burlakova L, Van Damme D, et al. 2017. Conservation status of freshwater mussels in Europe: state of the art and future challenges. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 92(1):572–607. doi:10.1111/brv.12244.

- Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, Von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. 2015. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 32(1):268–274. doi:10.1093/molbev/msu300.

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual (No. Ed. 2). Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

- Sheng JQ, Lin QH, Wang JH, Peng K, Hong YJ. 2014. Complete sequence analysis of mitochondrial genome in Hyriopsis schlegelii. Acta Hydrobiol Sin. 38(2):320–327.

- Skoulikidis NT, Zogaris S, Karaouzas I. 2022. Rivers of the Balkans. In: K. Tockner, C. Zarfl and C. T. Robinson (eds.), Rivers of Europe. Amsterdam: Elsevier; p. 593–653.

- Strayer DL. 2014. Understanding how nutrient cycles and freshwater mussels (Unionoida) affect one another. Hydrobiologia. 735(1):277–292. doi:10.1007/s10750-013-1461-5.

- Strayer DL. 2017. What are freshwater mussels worth? Freshw Mollusk Biol Conserv. 20(2):103–113. doi:10.31931/fmbc.v20i2.2017.103-113.

- Teiga-Teixeira J, Froufe E, Gomes-dos-Santos A, Bogan AE, Karatayev AY, Burlakova LE, Aldridge DC, Bolotov IN, Vikhrev IV, Teixeira A, et al. 2020. Complete mitochondrial genomes of the freshwater mussels Amblema plicata (Say, 1817), Pleurobema oviforme (Conrad, 1834), and Popenaias popeii (Lea, 1857) (Bivalvia: Unionidae: Ambleminae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 5(3):2959–2961. doi:10.1080/23802359.2020.1791008.

- Vaughn CC. 2018. Ecosystem services provided by freshwater mussels. Hydrobiologia. 810(1):15–27. doi:10.1007/s10750-017-3139-x.

- Zieritz A, Froufe E, Bolotov I, Gonçalves DV, Aldridge DC, Bogan AE, Gan HM, Gomes-Dos-Santos A, Sousa R, Teixeira A, et al. 2021. Mitogenomic phylogeny and fossil-calibrated mutation rates for all F-and M-type mtDNA genes of the largest freshwater mussel family, the Unionidae (Bivalvia). Zool J Linn Soc. 193(3):1088–1107. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa153.

- Zieritz A, Sousa R, Aldridge DC, Douda K, Esteves E, Ferreira-Rodríguez N, Mageroy JH, Nizzoli D, Osterling M, Reis J, et al. 2022. A global synthesis of ecosystem services provided and disrupted by freshwater bivalve molluscs. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 97(5):1967–1998. doi:10.1111/brv.12878.