?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The connections between time and space have been studied considerably in quantitative and qualitative research on the geographies of care; however, researchers tend to prioritize one approach over the other. Our article integrates analyses of activity spaces and space–time paths with conceptualizations of care developed in qualitative studies to deepen understanding of the spatiotemporal care routines of older adults in Singapore. Using qualitative geographic information systems (QualiGIS), we develop a comparative frame to understand the differential sociopolitical logics that shape the care routines of older adults who are Singapore citizens and nonmigrants vis-à-vis temporary migrants from the People’s Republic of China. Building on recent writing about care assemblages, we conceptualize webs of care as the interlinked chains, in and through which individuals—in this case, older adults—exercise agency to give and receive care in the context of political, institutional, and social structures. Our article shows how the relational thinking of assemblage theory can inform geographic information systems analyses of activity space and space–time paths. We advance research on care assemblages by identifying in actual time–space how various resources within care assemblages (or the lack of) can diminish or enhance the capacity and resilience of older adults to give and receive care.

定量和定性的护理地理学中, 有大量的连接时间和空间的研究。但是, 研究人员倾向于把时间置于空间之上或反之。本文把对活动空间和时空路线的分析与护理的定性概念相结合, 目的是更好地理解新加坡老年护理的时空路线。利用定性地理信息系统, 采用对比的方法, 本文理解了差别社会政治逻辑如何决定老年护理路线。老年人包括新加坡公民和来自中华人民共和国的非移民。基于护理集合体的最新文献, 我们将护理网络做为一组互联的线段, 在网络内或穿越网络, 个人(老年人)在政治、体制和社会结构背景下给与或接受护理。本文显示, 集合体理论的关联思想, 可以为活动空间和时空路线的地理信息系统分析提供信息。在现实时空内, 本文确认了护理集合体的各种资源(或缺乏这些资源)如何削弱(或加强)老年人给与和接受护理的能力和耐性, 从而推动护理集合体的研究。

La conexiones entre el tiempo y el espacio han recibido considerable atención en la investigación cuantitativa y cualitativa sobre las geografías del cuidado; sin embargo, los investigadores tienden a dar prioridad a un enfoque sobre el otro. Nuestro artículo integra los análisis de espacios de actividad y las trayectorias del espacio–tiempo con conceptualizaciones del cuidado desarrolladas en estudios cualitativos, para profundizar la comprensión de las rutinas espaciotemporales del cuidado de adultos mayores en Singapur. Usando sistemas de información geográfica cualitativos (CualiSIG), desarrollamos un marco comparativo para entender la lógica sociopolítica diferencial, que configura las rutinas del cuidado de adultos mayores ciudadanos de Singapur y no migrantes, con respecto a migrantes temporales de la República Popular China. Construyendo a partir de escritos recientes sobre ensambles de cuidado, conceptualizamos las redes de cuidado como cadenas entrelazadas, en y a través de las cuales los individuos ––es este caso, adultos mayores–– ejercen agencia para dar y recibir cuidado en el contexto de estructuras políticas, institucionales y sociales. Nuestro artículo muestra cómo el modo de pensar relacional de la teoría del ensamblaje puede informar los análisis de sistemas de información geográfica del espacio de actividad y las trayectorias del espacio–tiempo. Avanzamos investigación sobre ensamblajes de cuidado identificando en el tiempo–espacio real cómo varios recursos dentro de esos ensamblajes (o la falta de ellos) pueden disminuir o realzar la capacidad y resiliencia de los adultos mayores para dar y recibir cuidado.

Researchers studying care work and care relations have considered the manifold connections between time and space in the geographies of care. Such efforts include research that draws out the spaces in which care is carried out; the time–space trajectories of individuals who care or are cared for; the multiple institutions and scales of governance involved in care provision; and discourses about care relations (Razavi Citation2007; Bowlby et al. Citation2010; Milligan and Wiles Citation2010; Bowlby Citation2012; De Silva Citation2017). Our article elicits and deepens understanding of the spatiotemporal care routines of older adults in Singapore, including how they give or receive care in the home, neighborhood, and beyond. We develop a comparative frame to understand the differential sociopolitical logics that shape the care routines of older adults who are Singapore citizens and nonmigrants vis-à-vis temporary migrants, specifically grandparenting migrants from the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Our analysis is situated in literature that theorizes care (e.g., Razavi Citation2007; Bowlby et al. Citation2010; Milligan and Wiles Citation2010; Bowlby Citation2012) and it engages with writing on care assemblages (e.g., Epp and Velagaleti Citation2014; Dombroski, McKinnon, and Healy Citation2016; Huff and Cotte Citation2016; Power Citation2019). Care assemblages refer to how spatiotemporal processes and various resources (i.e., components) related to caregiving or care receiving come together or apart, producing particular effects and potentialities on people’s decisions or capacities to care.

Whereas qualitative research elicits insights into the complexities of care relations at the individualized level, we leverage geographic information systems (GIS) approaches to generate spatial visualizations of the older adults’ care routines. We incorporated Global Positioning System (GPS) tracking maps into follow-up interviews and used the qualitative data to contextualize our interpretation of the maps generated. These approaches (i.e., qualitative geographic information systems, QualiGIS) reiteratively informed our research process. As Kwan and Knigge (Citation2006) argued, “GIS is [not only] suitable for quantitative analysis, but also has potential for use as a critical visual method for representing the spatiality of social processes, for facilitating critical thinking throughout the entire research process, and for building theory that is grounded in both quantitative and qualitative data” (2001).

Our article integrates analyses of activity spaces and space–time paths—approaches deployed in GIS and quantitative research—with conceptualizations of care relations developed in qualitative studies. It compares the care routines of the Singaporean and PRC older adults, asking these questions:

How do care routines differ depending on the role that family members play in facilitating or constraining individual mobility?

How are care routines shaped by the type and location of social networks, encompassing both familial and nonfamilial others?

How are care routines influenced by the availability of institutional support through community organizations, elder-friendly facilities and activities, or both?

We use the concept of care assemblages to draw together the relations, processes, and resources that shape care. Our contributions to research on aging and care relations are twofold: First, a comparative approach draws out similarities and differences in the way nonmigrant and migrant older adults experience aging and negotiate their care needs alongside the care they give others. This comparative optic is necessary in societies like Singapore, which is experiencing changes tied to both new immigration and demographic aging. Singapore manages these by maintaining formal distinctions between nonmigrants who are citizens or permanent residents and those who are temporary migrants, which impact the aging experiences of the two groups of older adults. Second, and related, our analyses extend recent writing on care assemblages by conceptualizing webs of care as the interlinked chains, in and through which individuals—in this case, older adults—exercise agency to give and receive care, in the context of political, institutional, and social structures (henceforth macrostructures). We show how the relational thinking of assemblage theory can inform GIS analyses of activity space and space–time paths. We also advance research on care assemblages by identifying in actual time–space how various resources (or their lack) within assemblages can diminish or enhance the capacity and resilience of older adults to give and receive care.

The next section frames care relations in a spatiotemporal framework, highlighting how GIS visualizations and analyses can engage with qualitative approaches that emphasize individual experiences and the macrostructures that shape aging and migration. Concurrently, qualitative arguments would benefit from the point data and visualizations afforded by GIS approaches. We then explain the research design and methods. We next present the statistical findings from GPS tracking to compare and contrast the mobility patterns of the Singaporean and PRC older adults. We then draw on GIS visualizations and qualitative research findings to examine the care routines of the Singaporeans, followed by the PRC older adults. We conclude the article by referencing Wang, Li, and Chai’s (Citation2012) fourfold model of activity space to show how QualiGIS draws out the relational and negotiated aspects of spatiotemporal experience, contributing a fifth dimension on tension points. We also sum up how this article advances research on care assemblages and for policy purposes.

Analyzing Care and Aging Using Qualitative GIS

Care theorists, informed by qualitative research, have long argued that care relations are characterized by interdependency and reciprocity (Milligan Citation2009; Bowlby et al. Citation2010), and care relations encompass both proximate or embodied care and distant or proxy care (Baldassar and Merla Citation2014). This body of work has also argued that care is expressed and experienced in complex ways at a personal level, as well as within the wider context of institutional, social, and political arrangements for care. Qualitative researchers propose various conceptual frameworks to capture the complexity of care. Razavi’s (Citation2007) notion of the “care diamond” highlights the multiple institutions—family, state, market, and community—involved in care provision, and De Silva (Citation2017) adapted Razavi’s four-cornered care diamond to a five-cornered “care pentagon” that foregrounds the agency of older adults in providing self-care. For Milligan and Wiles (Citation2010), “landscapes of care” functions as an analytical framework to understand the “macro-level governance or social arrangements that can operate at either (or both) the national or international scales as well as the interpersonal” (738). Relatedly, Bowlby (Citation2012) and colleagues (Bowlby et al. Citation2010) conceptualized the term carescape to refer to “the resource and service context shaping the ‘caringscape terrain’” (Bowlby Citation2012, 2112). These terms seek to capture care exchanges over space, changes over time, and the macrostructures governing care. They also illuminate how aging is mediated by care relations.

As scholarship on care evolves, analyses of care practices and exchanges are increasingly engaging with assemblage theory. Assemblages are entities made up of heterogeneous components with the capacity to interact in contingent and fluid ways, even as each component maintains its relative autonomy (Anderson et al. Citation2012). An analytical optic of “care assemblages” focuses on how various components within an assemblage come together or apart “in the moment” (Dombroski, McKinnon, and Healy Citation2016, 238) to enable care (Power Citation2019). Assemblage components could include family members and friends, material objects, values and ideologies, events, places, institutions, and the marketplace. Such components are often anchored in particular spaces, taking on place meaning as users associate those spaces with their personal (situational) identities, well-being, and feelings of being in or out of place. Rather than studying components individually, care assemblages emphasize the effects and potentialities of the mix of resources within an assemblage, such as on how people make decisions and their capacities to care (Epp and Velagaleti Citation2014; Power Citation2019). Our article contributes to the theorization of care assemblages by foregrounding the multifarious ways in which older adults are embedded in webs of care, a term that draws inspiration from Closs-Stephen and Squire’s (Citation2012) argument that the metaphor of “webs” departs from the language of structure or agency, highlighting how multiple social actors are connected as lines in the web. These lines in the web shift relationally in particular spaces and at different times, thus deterring expectations that there is a preconstituted subject of what it is like to age or to be an older person. The social actors included in one’s webs of care depend on the perceived significance of the relationships and the quality of interactions, also affecting the type of assemblage components activated in particular time–spaces. Relational encounters are negotiated in the context of macrostructures that might create tension or enhance well-being in the lives of older adults, affecting their vulnerability or resilience at particular time–spaces. We further show how one’s capacity to care or to receive care is differentiated by subject positions, namely, between nonmigrants and migrants we studied in Singapore, as well as through other intersecting identity axes.

Although qualitative research provides insights on the embodied and cultural aspects of aging and care, alongside the macrostructures governing aging and care, we argue that georeferencing tools are an important complement for generating point data and mapping the actual spatiotemporal care routines of older adults. Geographers who support the integration of qualitative research with GIS analyses argue that the former provides a level of detail and nuance that quantitative data on their own typically do not capture (Elwood and Cope Citation2009, cited in Mennis, Mason, and Cao Citation2013; Delyser and Sui Citation2014). Human geographers have used three main approaches to integrate qualitative and GIS research: (1) modifying qualitative data so that they can be represented using cartographic techniques such as classification and symbols (e.g., Jung Citation2009; Bagheri Citation2014); (2) using participatory methods to derive GIS data and grounded visualization (Knigge and Cope Citation2006; Chan et al. Citation2014); and (3) hyperlinking strategies that associate qualitative data with spatial objects in GIS together with using software modifications, including mobile-based apps, to capture and represent the data analyses (e.g., Kwan and Lee Citation2004; Kwan and Ding Citation2008). The QualiGIS analyses in this article adopt elements of the first and second approaches; that is, using participants’ GPS tracks to “ground” their everyday care routines and providing interview quotations to contextualize those maps. Combining these methods provides a fuller depiction of the participants’ care routines than qualitative or GIS approaches alone could elicit.

Within GIS research, an individual’s usage of space is commonly depicted by activity space and space–time path visualizations. Activity space is defined as the local areas within which people move or travel as they carry out their daily activities. It refers to a “set of spatial locations visited by an individual over a given period, corresponding to her/his exhaustive spatial footprint; the regular activity space is the subset of locations regularly visited over that period” (Chaix et al. Citation2012, 441). For Wang, Kwan, and Chai (Citation2018), “activity space is generated considering not only people’s actual daily activity patterns based on GPS tracks but also the environmental contexts that either constrain or encourage people’s daily activity” (3). Wang, Li, and Chai (Citation2012) introduced four dimensions of activity space—intensity, extensity, diversity, and exclusivity—that we reference again later in this article. Another GIS visualization drawing out mobility patterns is the space–time path, namely, a three-dimensional (3D) trajectory, with its x and y dimensions representing geographical and physical space and the z dimension representing temporal progression. Space–time paths depict an individual’s daily movement in space and time (Kwan and Ding Citation2008). Simply put, activity space provides an aggregate visualization of the individual’s geographical reach, whereas space–time path distills the data into the type and timing of those activities over a shorter temporal frame. Nonetheless, these visualizations alone do not adequately explain the motivations, resource and service contexts, social discourses, governance structures, and care exchanges shaping behavioral patterns (e.g., why an older adult’s mobility patterns might be confined despite having the ability to travel). To derive such insights, qualitative research methods such as ethnography and interviews remain essential.

For qualitative researchers, the GIS approaches introduced in this article enhance analyses of care routines and assemblages by making explicit how distance, reach, directionality, and the timing of care activities matter in the daily routines of older adults (e.g., juggling competing care needs). Activity space and space–time paths represent GIS approaches that capture the type of individual-level data valued by qualitative researchers. These visualizations depict how an older adult’s mobility patterns are situated in the physical attributes of the built environment and his or her social–cultural contexts (Kwan Citation2012). They allow researchers to convert individual-level GPS data to standardized visual patterns that enhance the ability of qualitative research to conduct comparative analyses. Moreover, GPS tracking and GIS methods can map the actual boundaries of participants’ geographical reach to verify their subjective interpretations of space (see Milton et al. Citation2015). Several QualiGIS projects have worked with small sample sizes and adapted their data collection and analyses to suit their research goals (e.g., Jones, Drury, and McBeath Citation2011; Naybor, Poon, and Casas Citation2016). A few focused on older adults (e.g., Zeitler et al. Citation2012; Milton et al. Citation2015; Zeitler and Buys Citation2015; Franke et al. Citation2017), deriving data from a combination of GPS tracking, travel diaries, surveys, and semistructured interviews. Likewise, we leverage our small sample size by using qualitative, quantitative, and visualization methods reiteratively to develop richer and nuanced analyses of the care routines and relations that make up the care assemblages examined in this article.

Our QualiGIS research thus not only gives attention to the measures and visualizations of space as GIS analyses would but also situates the care routines of older adults in thematic analyses of care relations and assemblages that qualitative researchers foreground. This integration of approaches draws out (1) how exchanges of and changes to care flows over time and space create webs of care that depict relationality and negotiations; (2) the wider macrostructures and the agency exercised by older adults that together shape webs of care; and (3) commonalities and differences in how nonmigrant and migrant older adults navigate care. We show that despite the seeming fixity of the web (represented here by GIS visualizations of space), the webs of care that populate care assemblages are actively woven through spatiotemporal encounters and negotiations that have a contingent and fluid nature.

Study Context and Methods

Aging in Singapore is shaped by state policies on urban planning, housing, immigration, and aging. Singapore’s urban and housing policies are based on the concept of “new towns”—these high-rise and high-density housing estates are designed as relatively autonomous communities to minimize residents’ need to travel further for amenities. The majority of these public housing flats—known as Housing Development Board (HDB) flats—are owner-occupied and categorized by rooms (e.g., four- or five-room flat). Housing type by rooms refers to a common living area (considered one room) and the number of bedrooms in a flat. Such categorizations can be taken as an approximation of a family’s socioeconomic status, because it is treated as asset ownership that is taken into consideration during means testing for state subsidies.

As Singapore’s housing estates have matured demographically, the state and voluntary welfare organizations—also known as social service agencies—have established elder-friendly facilities and services. The state uses housing policy to manage ethnic mixing in multicultural SingaporeFootnote1 as well as to encourage married children to live with or apply for flats near their parents (e.g., Proximity Housing GrantFootnote2). Qualifying for public housing purchase and subsidies are used as incentives to encourage immigrants to become Singapore permanent residents (SPRs) and Singapore citizens, if they fulfill the skills, occupational, and income criteria of Singapore’s immigration policy. The proportion of flats that can be owned by SPRs in a block of flats or neighborhood is regulated by the state to ensure social mixing with citizens. Immigrants who are not SPRs or Singapore citizens can only rent or purchase from HDB flat owners at nonsubsidized prices.

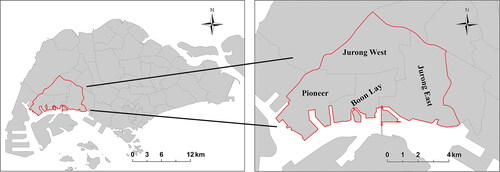

Our study was conducted in the Greater Jurong area (), a mature region with an aged residential population (sixty years old and above) of approximately 58,000 (Singapore Department of Statistics Citation2017), or approximately 10 percent of the total number of older adults in Singapore (Singapore Department of Statistics Citation2019). The area is served by a number of eldercare facilities and services (Agency for Integrated Care Citation2013). Many new immigrants reside in Greater Jurong, either by purchasing or renting flats. These include the PRC Chinese who account for around 18 percent of the migrant pool in Singapore (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Citation2019). Although this figure is lower than the percentage of Malaysian migrants (44 percent), Singaporeans have expressed strong social prejudice toward the PRC Chinese in everyday life and in news and social media reports (see Yeoh and Lin Citation2013; Ang Citation2017; Ho Citation2019). PRC older adults regularly come as “grandparenting migrants” to help care for young grandchildren by applying for dependent visas or short-term tourist visas. The former visa depends on their adult children’s eligibility visa type, income level, and occupation, whereas the latter is incrementally extended by repeatedly leaving and returning to Singapore.

Our QualiGIS research was part of a larger project on how Singapore functions as a hub of care relations, connecting the city-state to its regional neighbors, including China. Approval from the Institutional Review Board was obtained at the first author’s home institution. This article draws on two linked components of the project, one focusing on nonmigrants and the other on PRC older adults who are temporary migrants. All of our participants were formally retired at the time of interviews. We conducted opening in-depth interviews with sixty-nine Singaporeans and forty-one PRC older adults (n = 110 total), the majority of whom resided in Greater Jurong. These interviews focused on the participants’ experiences of aging in Singapore and the ways they give or receive care. Participants were recruited through formal (e.g., community centers, family service centers, day care centers) and informal (e.g., personal contacts and networks, public spaces) channels. To deepen our understanding of their care routines, we selected a subset of participants residing in Greater Jurong (ten Singaporean and ten PRC older adults; n = 20) to carry out go-along interviews, seven days of GPS tracking, and a closing interview (). The twenty participants were selected for the range of mobility patterns they exhibited (identified from initial interviews) and can all be classified as “young-old” (sixty to seventy-four years old).

Table 1. Fieldwork stages and number of participants

The average number of days tracked for the twenty participants was six and a half days of the seven days targeted. The GPS trackers were set to record every thirty seconds. GPS trackers with antennas were adopted because they provide high accuracy and work in environments where the signal could be weak. Participants were told to ensure that the trackers were on whenever they left their homes. Each participant would receive a text message in the early morning reminding them to change the batteries in the trackers to new ones. The GPS tracking data and GIS maps were processed in ArcMap 10.5, during which GPS data would be cleaned and GPS points that had deviated were removed. We used the GIS maps generated to conduct closing interviews, which elicited the participants’ recollections, attitudes, and feelings toward the care routines they had undertaken that week. This reiterative QualiGIS approach enabled the researchers to detect missing GPS data or deviations. For example, if there were two consecutive GPS records that extended longer than thirty minutes, the interviewer would ask the participant to identify any activity that had not been recorded. Missing GPS points would be inserted by interpolating the points in both spatial and temporal dimensions or only in the temporal dimension if the participant indicated that he or she had not changed location during that period. Likewise, the interviews helped identify deviations, such as when the participant was indoors but the GPS points had bounced far from the buildings. The in-depth interviews were conducted in communal spaces or in the participants’ homes with their consent. For sit-down interviews, we obtained the participants’ consent to record and transcribe the content, whereas the go-along interviews were mainly recorded as field notes. All interview transcripts and field notes were coded in Atlas-Ti for analysis.

For this article, we calculated activity space measures for twenty participants. Of this pool, we selected six examples to illustrate how QualiGIS enhances understanding of their care routines (categorized by nonmigrant and migrant statuses; see ). The names used in this article are pseudonyms and the participants’ home locations have been spatially altered by moving them slightly without affecting the activity spaces calculated. The urban housing morphology in Singapore is such that multiple flats are located within a high-rise block and closely built blocks are contained within a housing estate, making it unlikely that a participant’s home can be identified from the maps. The privacy measures taken and the context of the housing morphology in Singapore ensure that our participants’ identities have been adequately protected.

Table 2. Pseudonymized profile of the participants discussed

Measures of Activity Spaces

Recent studies of activity space have relied on GPS tracking to derive spatial and temporal data. Chaix et al. (Citation2012) argued that GPS tracking has an advantage over self-reporting survey data because the former provides nearly continuous polylines, whereas surveys collect data at a single point reported by the participant. Moreover, GPS tracking indicates the temporal sequence of places visited, whereas surveys provide “nonsequential data on temporally disconnected activity locations” (Chaix et al. Citation2012, 443). Chaix et al. (Citation2012) used GPS tracking and generated polygon visualizations to depict “participants’ network of regular destinations and assessment of the perceived boundaries of their residential neighborhood” (442). In another study, Hirsch et al. (Citation2014) generated three types of activity space visualizations, namely, the standard deviation ellipse (SDE), the minimum convex polygon (MCP), and the daily path area, drawing on GPS tracking as well. They argued that using activity spaces to investigate older adults’ mobility “will give additional insight into the community factors and resources that shape neighborhood activity” (Hirsch et al. Citation2014, 2).

We engaged with activity space analyses to determine quantitatively and generate visually the spatiotemporal routines that reflect the care relations of our participants. We used two different measures: SDE and MCP. Whereas SDE captures the frequency of the older adults’ mobility patterns, MCP provides information on the farthest points traveled to during the week of GPS tracking.

SDE Generation

Participants were provided with GPS trackers and their locations were recorded continuously for seven days, including during the night. For each participant, all locations were exported and mapped in ArcMap 10.5 to generate the ellipse. Locations that were more frequently visited by the participant had more recorded points and thus were assigned a larger weight when generating the ellipse. The participants’ homes had the largest number of points because they spent most of the day at home. Some participants opted to turned off the GPS trackers at night for power saving, whereas others did not do so. To ensure fair comparisons among all participants, we adopted a fixed total weightage of “stay at home” points set at 80 percent; according to our GPS tracking statistics, the average “stay at home” duration of our participants accounts for approximately 80 percent of a day.

The advantage of using SDE is it considers the frequency of the visited locations by counting the recorded points at these locations. Once the GPS points had been mapped and the proportion of home-recorded points adjusted, an ellipse was generated for each participant using the Spatial Statics Tools embedded in the ArcGIS software. Existing literature (Schönfelde and Axhausen Citation2003; Sherman et al. Citation2005; Zenk et al. Citation2011) on the conception of SDE is inconclusive on whether to adopt the first-level SDE (SDE1) or the second-level SDE (SDE2). SDE1 contains 68 percent of all of the adopted points, whereas SDE2 contains 95 percent of all of the points. Because the first-level SDE tends to underestimate the actual geographical activity area and the second-level SDE2 is sensitive to outlier activity points, we chose to generate both levels of SDEs in this study to complement each other.

MCP Generation

The same set of GPS points was employed to generate the MCP, namely, the smallest polygon that contains all GPS points. The vertices of the MCP are the outermost points. The advantage of using MCP is that it fully represents the spatial reach of a participant. It does not consider the frequencies of the visited locations by participants, however, and is sensitive to distributions of unusual long-distance activities.

In generating the GIS visualizations, we noticed that certain routes and location points that participants had spoken about during the qualitative interviews were not captured in the SDE or MCP visualizations. As discussed earlier, through the in-depth interviews, we were able to manually fill in the missing points and include the information in the SDE and MCP calculations. Because the calculations and visualizations generated before and after manually filling in the missing points were considerably different, we opted to include the manually plotted points in the SDE and MCP calculations to better reflect the mobility patterns of the participants.

indicates the activity spaces of the Singaporean and PRC older adults in terms of the three measures. Their activity spaces vary greatly by each measure. Of all three measures, the activity space of SDE1 has the smallest mean and median area, and that of MCP has the largest mean and median area. The mean and median areas of SDE2 are nearly four times those of SDE1. In comparing the area measures of the Singaporean and PRC older adults, we found that the activity spaces of the PRC older adults are significantly smaller than those of Singaporean older adults in terms of all three measures. The mean activity space area of the Singaporean older adults is about five times that of the PRC older adults (SDE1, 5.0; SDE2, 5.0; and MCP, 5.1). As for the median activity space area, the difference is even larger. The median SDE1 and SDE2 area of the Singaporean older adults is 8.0 times that of the PRC older adults, and the median MCP area of the Singaporean older adults is nearly 13.2 times that of the PRC older adults.

Table 3. Activity space of Singaporean older adults and PRC older adults

The calculations of the mean and median indicate that overall the PRC older adults have more restricted activity spaces than the Singaporeans. Activity space measures on their own, however, do not provide adequate information on the reasons for these findings. We turn to the space–time paths and qualitative research findings in the next two sections for more nuanced insights.

Singaporean Older Adults’ (Nonmigrants’) Webs of Care

The following sections bring together GIS and qualitative analyses of care relations. We highlight how insights from theorizations of care contribute to drawing out the relational and negotiated aspects embedded within two-dimensional (activity spaces) and three-dimensional (space–time paths) representations. For the latter, through findings derived from the point data and post-GPS interviews, we categorized the participants’ care-related motivations for mobility into three types of activities: mobility for self-care (e.g., leisure and fitness), mobility for other care (e.g., ferrying grandchildren and grocery shopping for the family), and stay at home (i.e., point data that indicate the participant stayed at home; the activity could be for either self-care, other care, or both). We acknowledge that the motivations for and outcomes of mobility are fluid; nonetheless, approaching the analyses through these heuristic categorizations—for example, how self-care is negotiated in relation to other care activities and resources—enables us to examine the relational and dynamic aspects of care assemblages and webs of care. Expressions of care by the older adults are demonstrated through a range of activities and they use multiple transportation modes: For proximate locations, they might walk or ride a bicycle; for further locations, they might take a bus or the mass rapid transit system. Public transportation in Singapore is generally convenient and affordable (our study area contains two mass rapid transit stations). Due to high costs, car ownership is less common, but a few of our participants have access to cars owned by other family members.

The first two cases presented here and in the next section depict the minimum and maximum activity spaces (and corresponding space–time paths) recorded by our participants; more importantly, these visualizations—accompanied by qualitative findings—convey how care is expressed through activity and mobility patterns. Crucially, we consider such visualizations not as fixed frames; rather, through the lens of care assemblage theory, we treat the places and mobility patterns depicted as assemblage components and webs of care that shift according to how older adults adjust their spatiotemporal routines to meet their own or others’ needs. In line with this approach, we added a third case in each section that extends insights on how care negotiations affect the routines of older adults.

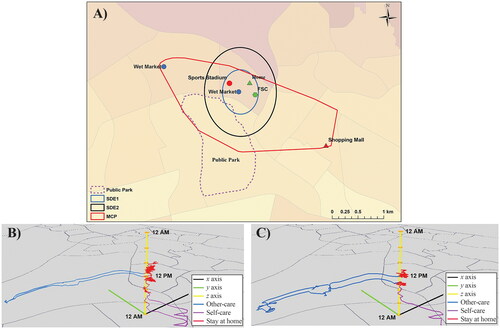

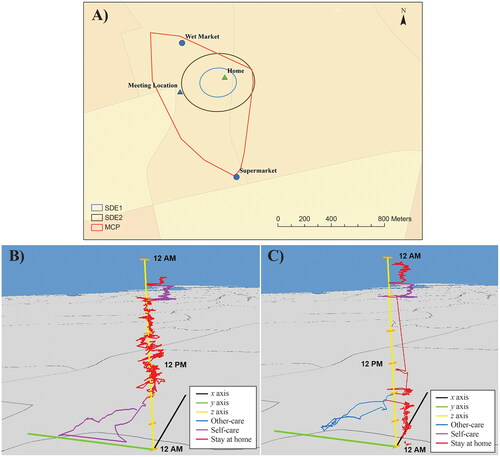

Among the Singaporean older adults in our study, Mr. Seet’s SDE and MCP calculations were the lowest (SDE1, 0.47; SDE2, 1.89; MCP, 4.00). His daily activities are centered within his housing estate, as reflected in his relatively contained SDE1 and SDE2 patterns (). Mr. Seet’s activity spaces are sustained by his active role in weaving care relations, primarily with those who stay with him (his wife and younger son) or in proximity to him within Greater Jurong (his elder son and family, mother-in-law, and brother-in-law; enabled in part by the Proximity Housing Grant). Among his activities are regular visits to the nearby wet market (within the SDEs in ) or occasionally to a farther wet market (westernmost end of the MCP in ), for grocery shopping to prepare meals for his family (i.e., expressing care relationally; blue lines in ). The easternmost point of his MCP is a shopping mall where he bought toys for his grandchildren. Mr. Seet’s webs of care extend to a large public park () that he visits every weekday to exercise with friends (magenta line in from 7 a.m. to 8:30 a.m.). He could use a nearer sports stadium () but prefers the park, reflecting that “care between friends is linked to particular activities in particular places” (Bowlby et al. Citation2010, 117). Such friendship networks in webs of care are vital care resources, but they are negotiated in relation to family care. Mr. Seet balances time to ferry his grandchildren with time for his friends by spending less time at home (fewer red lines in than ). Similarly, he adjusts his leisure and educational pursuits by only attending activities at the family services centerFootnote3 (FSC in ) nearest his home because traveling further could derail him from tending to the needs of his mother-in-law at short notice. Mr. Seet’s geographical reach is not constrained by debilitating ill health, inaccessibility, or monetary concerns. His compact SDEs and MCP foreground the everyday, informal ways in which care is structured to negotiate family priorities, resonating with Huff and Cotte’s (Citation2016) observation that “family is something that is done when the components [of the assemblage] that comprise it are set in motion” (896, italics in original). The webs of care highlighted in Mr. Seet’s case are spatially anchored to assemblage components (i.e., places) that he negotiates through time adjustments depending on how his care duties to different family members stack up against his self-care goals.

Figure 2. Geographic information systems visualizations of Mr. Seet. (A) MCP and SDEs; (B) space–time path without grandparenting duties; (C) space–time path with grandparenting duties. FSC = family service center; SDE1 = first-level standard deviation ellipse; SDE2 = second-level standard deviation ellipse; MCP = minimum convex polygon.

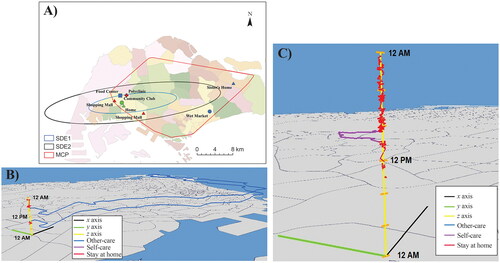

Another Singaporean, Madam Aisha, had the largest SDE and MCP calculations (SDE1, 63.69; SDE2, 254.75; MCP, 349.20). The SDE1 indicates that her most regular activities (e.g., meals, medical checkups) are centered in her neighborhood (food center and polyclinic in ). Nonetheless, her elongated SDE2 reflects the longer distances she would travel to connect her care needs with other resource components in her care assemblage. She makes regular trips to exchange emotional care with first her sister who lives in the east (sister’s home and wet market in ) and, second, ex-colleagues who work at two shopping malls in the west (shopping malls in ). Notably, Madam Aisha’s ability to travel is constrained—changing her care assemblage—whenever she has grandparenting duties (compare ; the red lines along the vertical z-axis in indicate she stayed at home). She adjusts her routine by making only necessary and short trips, such as to the nearby community club to renew her medical subsidies scheme (short magenta line in ). Madam Aisha cites her lower socioeconomic standing as one reason for remaining at home—outings with her grandchildren usually lead to increased expenditure (e.g., on toys). Her restricted movements must be understood as care that is negotiated in the context of class constraints. Moreover, the postretirement “new dimensions of selfhood” (Conradson Citation2005, 346) envisioned by Madam Aisha are not characterized primarily by grandparenting duties but mobility freedom (e.g., blue line in ; preparations for a relative’s wedding). Another reason for her expansive activity spaces is the lack of communal and institutional resources suitable for her in the neighborhood (i.e., a resource constraint in her care assemblage). Although there is a senior activity center nearby, Madam Aisha references the absence of other Malays like herself and an unwillingness to “mix with old women” as drivers to carve out her care routines. Her concerns about being an ethnic minority and the potentiality of reinforcing agist stereotypes prompt her to seek farther care options. The social and material components of assemblages (Power Citation2019)—and ensuing webs of care—must thus be analyzed in the context of class, ethnicity, and agist considerations, affecting the way people reason about what counts as appropriate care and how they gather or dislodge certain components in their care assemblages.

Figure 3. Geographic information systems visualizations of Madam Aisha. (A) MCP and SDEs; (B) space–time path without grandparenting duties; (C) space–time path with grandparenting duties. SDE1 = first-level standard deviation ellipse; SDE2 = second-level standard deviation ellipse; MCP = minimum convex polygon.

Our third example is Madam Low, whose heavy care responsibilities for family members result in her SDE1 (5.34) and SDE2 (21.37) being less than the mean of the other Singaporeans (M SDE1 = 16.40; M SDE2 = 65.59) and closer to those of the PRC older adults (M SDE1 = 3.27; M SDE2 = 13.08). Madam Low’s activity spaces and interviews reflect how she adjusts her routines to balance various care needs within her care assemblage. She is the primary carer for her husband, who has Parkinson’s disease, and her grandchildren after their schooling hours. Madam Low would face scheduling conflicts if not for a nearby senior daycare center (i.e., a resource in her care assemblage) that her husband uses during weekdays (7:30 a.m.–4:30 p.m.). This arrangement allows Madam Low to pursue leisure activities with friends (self-care) on weekday mornings and to look after her grandchildren (other care) in the afternoons, mainly at home. Madam Low’s SDE1 and SDE2 patterns are elongated, indicating that her regular routines extend eastward and westward (); this pattern reflects the friendship networks that expand her geographical reach. Through her neighbors, Madam Low’s webs of care have steadily grown—assembling a repertoire of activities and resources, such as Zumba and karaoke lessons, all of which were couched in tropes of self-care (e.g., “to avoid developing dementia”) and receiving care (e.g., “my friends have been encouraging me to continue”). The activities at the family service centers (FSC in ) are state subsidized, providing Madam Low with respite from a pressurizing situation at home. Assembling a mix of resources—supported by state services and subsidies—enables her to balance the need to give care with the ability to receive care. Nonetheless, Madam Low’s space–time paths reflect how one’s webs of care and their connections to assemblage components change when there are other relational care needs. During the GPS tracking week, Madam Low spent less time at home and on self-care (i.e., activities with friends) when her husband was hospitalized. The added responsibility of visiting him (blue lines in ) explains why her SDE2 is approximately four times the size of her SDE1 (). On another day, her space–time path unexpectedly widened to encompass a park and a shopping mall (blue line with a noticeably farther reach in ) when she spontaneously brought her grandchildren to purchase terrapins. Such spatiotemporal reorganizations attest to the “permeability” of care assemblages (Huff and Cotte Citation2016), shifting relationally when one family member has greater care needs.

Figure 4. Geographic information systems visualizations of Madam Low. (A) MCP and SDEs; (B) and (C) space–time paths (both with grandparenting duties). FSC = family service center; SDE1 = first-level standard deviation ellipse; SDE2 = second-level standard deviation ellipse; MCP = minimum convex polygon. FSC = family service center; SDE1 = first-level standard deviation ellipse; SDE2 = second-level standard deviation ellipse; MCP = minimum convex polygon.

The three cases just discussed are instructive on two fronts. First, activity spaces are more than indicators of directionality and extent of travel. Their sizes (compact or expansive) and shapes (spherical or oblate) are suggestive of an individual’s care assemblages and webs of care. Activity spaces that extend beyond the Greater Jurong region reflect care relations that are extensive (e.g., Madams Aisha and Low), whereas it is the reverse for those who coalesce around their neighborhoods (e.g., Mr. Seet). Second, activity spaces and space–time paths on their own are insufficient for eliciting the variegated processes undergirding them. Rather, complementing such analyses recursively with qualitative data can flesh out how assemblage components having to do with cultural discourses (e.g., family values or on aging), the built environment (e.g., proximity or distance from amenities or other resources), and intersecting identity axes (e.g., class, ethnicity, age) shape the way Singaporean older adults negotiate care across time–space and scales (home, community, or state).

As a framework, care assemblages hold together multiple assemblage components and give analytical space to the relational and negotiated aspects of webs of care. The social actors drawn into webs of care vary depending on the perceived significance of those relationships and the quality of interactions. For Madam Aisha, the neighbors who participate in the senior activity center near where she lives do not feature prominently in her webs of care because she is unwilling to mix with them, whereas Madam Low’s webs of care include her neighbors because their companionship is a source of comfort to her. Even the extent to which family members—normally associated with enduring blood ties—feature in webs of care often evolves, such as when older family members’ care needs increase as they grow frail (e.g., Mr. Seet’s mother-in-law or Madam Low’s husband) or when grandchildren require less hands-on care as they grow more independent (e.g., Madams Aisha and Low).

As for the negotiated aspects of webs of care, people’s decisions or capacities to care will depend on how the relations and components within one’s care assemblage converge or diverge in specific time–spaces (e.g., contrast Madam Aisha’s space–time paths on the days with and without grandparenting duties; Madam Low’s potential scheduling conflicts if not for the day care service her husband uses). Webs of care can illuminate potential tension points and the way older adults exercise agency and fulfill their care obligations by adjusting their spatiotemporal routines to activate resources within their care assemblages. We turn next to the PRC older adults to analyze how their care assemblages and webs of care are modulated by their subject positions as temporary migrants, affecting their capacity to give or receive care.

PRC Older Adults’ (Migrants’) Webs of Care

Researchers have argued that the extent to which older migrants are able to assert agency depends on the personal resources they have, their immigrant or citizenship status, and their access to care (De Silva Citation2017; Bélanger and Candiz Citation2019). These considerations could be regarded as components in care assemblages. We examine how care assemblages and webs of care feature in the activity spaces and space–time paths of the PRC older adults. Because their main role for migrating to Singapore is for child care, the following space–time paths both indicate days when they have grandparenting duties.

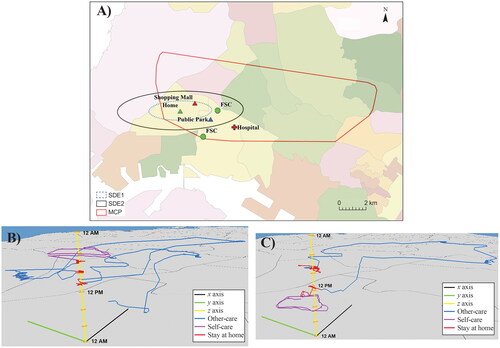

Among the PRC older adults sampled, Mr. Dai’s activity space calculations are the smallest (SDE1, 0.05; SDE2, 0.19; MCP, 0.54). His compact activity spaces show that his care assemblage and webs of care revolve around the immediate neighborhood (). Mr. Dai and his wife are grandparenting migrants but they have light roles, because the family employs a foreign domestic worker. Cultivating friendship networks is an important source of self-care for PRC older adults like Mr. Dai, functioning as an assemblage resource and extending his webs of care. His activity spaces and interviews illustrate how friendship networks can expand one’s geographic reach (Bunnell et al. Citation2012). Mr. Dai had ventured farther than usual during the weekend of GPS tracking (; first magenta line from the foot of the z-axis) compared to the weekdays (). His friends—also PRC older adults (migrants)—had brought him to a Christmas carnival at a location new to him. At other times, they go to different wet markets for fresher and less expensive produce. On weekday evenings, he meets his friends at a housing block around 8 p.m. (meeting location in ). Nonetheless, Mr. Dai adjusts his nightly routine to be home around 9 p.m. when the grandchildren are ready for bed. His morning routines are also organized around family needs (e.g., cooking breakfast at 5 a.m. and going to the market at 7 a.m.; red and blue lines, respectively, in ). Mr. Dai recounted that when his family moved to a private condominium farther from his former HDB flat, the social gatherings with his friends decreased substantially. To negotiate this change to his social life, he continues to visit his former neighborhood regularly. In other words, when new assemblage components are introduced, existing components and trajectories of the assemblage are modified to maintain important webs of care (in this case, friendships).

Figure 5. Geographic information systems visualizations of Mr. Dai. (A) MCP and SDEs; (B) and (C) space–time paths (both with grandparenting duties). SDE1 = first-level standard deviation ellipse; SDE2 = second-level standard deviation ellipse; MCP = minimum convex polygon; FSC = Family Service Centre.

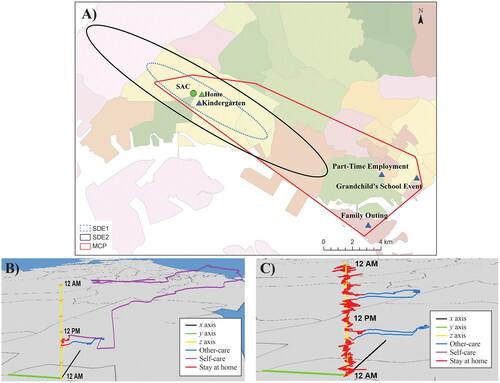

Among the PRC older adults, Madam Zhen’s SDE and MCP values are the largest (SDE1, 13.76; SDE2, 55.3; MCP, 84.88; ). Even so, her activity spaces—which are considerably larger than the mean of the PRC older adults—are only average relative to the Singaporean older adults. Madam Zhen’s oblate SDEs are tilted 45°, which indicate that she often moves in a southeastern direction, usually for family reasons (grandchild’s school outing and family outing in ). Her regular routine revolves around her granddaughter’s care needs (; blue lines indicate trips to the kindergarten). She participates in leisure activities, however, such as by enrolling for a five-year membership (costing about US$15) at a privately operated senior activity center, and socializes with other PRC older adults through walking or dancing activities in her neighborhood. Such social ties are important features of her webs of care and function as a resource in her care assemblage, such as by providing emotional support, facilitating leisure pursuits, and offering practical information about living in Singapore, including opportunities for informal work. Although waged work is not allowed under the visa that she holds, Madam Zhen finds it “too boring to stay at home” and feels “guilty” using her daughter’s credit card for her own purchases. Such sentiments bear strong resemblance to those of the other participants—both locals and foreigners—yearning for independence in old age, linking notions of selfhood with an active lifestyle and spatial mobility. To juggle her employment as a paid part-time cleaner, she sends her granddaughter to school in the west (8 a.m.) and then heads to the southern part of Singapore at 10 a.m. for work (blue line and magenta line, respectively, in ). Other times, she stays home (red lines in ) and ventures out only for grandparenting duties. Madam Zhen’s maps and interviews show that her webs of care and assemblage components are primarily shaped by grandparenting duties, but these coexist uneasily with her personal aspirations for “creative agency” (Power Citation2019, 774) to maintain autonomy.

Figure 6. Geographic information systems visualizations of Madam Zhen. (A) MCP and SDEs; (B) space–time path; (C) space–time path (both with grandparenting duties). SAC = senior activity center; SDE1 = first-level standard deviation ellipse; SDE2 = second-level standard deviation ellipse; MCP = minimum convex polygon.

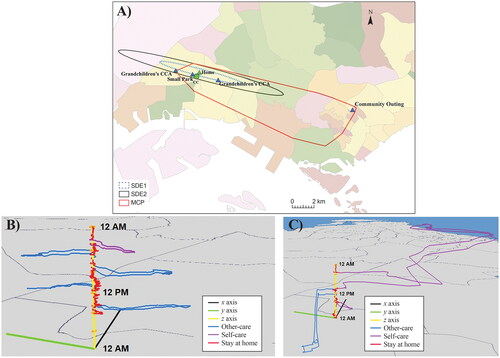

Our last participant, Mr. Liu, also balances his family duties with negotiating the challenges of being an older adult aging abroad. His relatively expansive activity space (SDEs in ) reflects the care assemblage and webs of care he maintains for two grandchildren, including doing grocery shopping for meal preparation, ferrying them to school on weekdays (blue lines in ), and bringing them to enrichment activities (i.e., cocurricular activities) within Greater Jurong on weekends (blue line in ). When he stays at home, he dabbles in the stock market “to keep [his] mind active” and takes a stroll to the neighborhood parks in the evenings (red and magenta lines, respectively, in ). Another key component of Mr. Liu’s care assemblage includes the state-affiliated and nonprofit groups that organize community activities, thereby expanding his geographical reach (community outing in ; long magenta line in ). Although he enjoys these activities, he participates in them sporadically now due to scheduling conflicts; moreover, as several of the PRC participants shared, they have felt unwelcome or excluded (i.e., lack of care) from some community activities, such as those held at the community club that prioritize citizens and permanent residents. Such accounts remind us of how state “policies and related regulatory systems … [are] forces that generatively shape the potential for care [or lack thereof]” from a distance (Power Citation2019, 768), constraining the participation of migrants in community activities that could have expanded and diversified the resource mix in their care assemblage.

Figure 7. Geographic information systems visualizations of Mr. Liu. (A) MCP and SDEs; (B) and (C) space–time paths (both with grandparenting duties). CCA = cocurricular activities; CC = community club or center; SDE1 = first-level standard deviation ellipse; SDE2 = second-level standard deviation ellipse; MCP = minimum convex polygon.

The cases of Mr. Dai, Mr. Liu, and Madam Zhen highlight the spatiotemporal adjustments they make to balance grandparenting duties with individual pursuits as older adults in a foreign land. Although formal child care spaces exist, such assemblage components are dislodged in favor of the personal care provisioned by grandparenting migrants. Webs of care tied to assemblage components of cultural values and family duty prompted their migration, whereas new webs of care and assemblage components are further incorporated after migration for leisure, fitness, and educational goals. Yet at times, priority given to citizens causes temporary migrants to feel excluded from state-funded activities. As temporary migrants, they lack the right to work in Singapore—an assemblage component that some older adults feel remains important to their self-actualization in later life. Such macrostructures shaping their assemblage components cause the PRC older adults to feel that they experience unequal power relations as temporary migrants in Singapore.

Conclusion: Weaving Together Webs of Care Using QualiGIS

The QualiGIS analyses reported here uncover key points for our conceptualization of the webs of care that exist within care assemblages and connect assemblage components. Webs of care highlight the everyday, routine ways in which the actions of older adults matter for peer and intergenerational care transfers as they activate or negotiate components within their care assemblages. GPS tracking and mapping pin down the timings and spaces in which the older adults we studied engaged in different activities, thereby identifying the components of their care assemblages, and the qualitative interviews helped corroborate their spatiotemporal routines and elicit in-depth information on their webs of care. We refer now to Wang, Li, and Chai’s (Citation2012) framework on the dimensions of activity spaces—intensity, extensity, diversity, and exclusivity—to show how QualiGIS extends conceptualization of care assemblages and webs of care by eliciting the relational and negotiated aspects of spatiotemporal experience and by drawing out the commonalities and differences between nonmigrants and migrants.

First, the activity spaces and space–time paths of the Singaporeans are characterized by a lower intensity than those of PRC older adults when it comes to grandparenting duties. Intensity refers to the frequency and duration of visits to certain spaces. The lower intensity of the former to spaces tied to grandparenting duties is partly because they do not always reside with their grandchildren. In contrast, the PRC older adults stay with their grandchildren, and turning to extended kin for child care help is not a recourse readily available to them. The differential intensity with which the older adults are engaged in grandparenting duties affects their schedules for self-care (e.g., mental and physical wellness, or self-actualization). Tropes of being a “sacrificial” or “dutiful” grandparent cut across both groups. Relational and affectual processes—namely, the “stickiness” of webs of care—undergird routes, routines, activity spaces, and space–time paths. The GIS visualizations show how their time for self-care is negotiated alongside care duties and the mix of institutional, political, and social resources (i.e., macrostructures) under which they operate (the latter point is further developed later). In other words, QualiGIS visualizations allow us to understand how the components within care assemblages and relational webs of care are assembled.

Second, the quantitative calculations show that the Singaporeans have more extensive activity spaces and space–time paths than PRC older adults owing to the latter’s migrant experience (i.e., less familiarity with the cityscape) and comparatively inflexible schedules. Extensity refers to the geographical extent of activity space, which is related to an individual’s sociospatial mobility. Nonetheless, the qualitative data inform us that there are marked similarities between both groups. Regardless of whether the activity spaces are compact or extensive, it is their webs of care that motivate them to restrict or extend the geographical boundaries of their activity spaces and adjust their space–time paths accordingly. As shown in the activity space maps, the assemblage components of Greater Jurong enable them to negotiate the care demands on their time efficiently within the precinct. Such assemblage components include the compact town planning, neighborhood amenities, and access to reliable public transportation. Other assemblage components shaping their webs of care include state policies (e.g., Proximity Housing Grant) and formal or informal social services (e.g., day care services), which are enabling for the Singaporeans, whereas access to these care provisions might not be fully available to PRC older adults. The locations within the QualiGIS visualizations thus not only indicate physical space but also reflect the macrostructures (i.e., assemblage components) through which webs of care are forged relationally and contingently.

Third, with greater extensity and lower intensity, it is unsurprising that the activity spaces and space–time paths of the Singaporeans display greater diversity in the types of places visited and activities undertaken—comprising their care assemblages—compared to PRC older adults. Diversity connotes gathering a mix of resources (people, places, and activities) as assemblage components to enrich one’s webs of care relationally, such as by participating in community activities for self-actualization, (re)assembling friendship networks, or earning a side income through informal work to reduce one’s financial reliance on his or her children. Both compact and extensive activity spaces reflect how the older adults perceive notions of personhood and self-actualization, including actively negotiating the opportunities or constraints posed by macrostructures to maintain their spatial and social independence in old age. Such activities and decisions convey the way that they express agency (De Silva Citation2017) within their webs of care to negotiate the dependent identity normally ascribed to them, potentially transforming how the components within their care assemblages take shape.

Fourth, compared to Singaporeans, the PRC older adults have reduced access to spaces managed by state bodies (e.g., CCs) and experience perceived social exclusion. Exclusivity refers to the degree of exclusion, isolation, or segregation of an activity space, and it is determined by the accessibility of that space. Analyzing individuals’ activity spaces and space–time paths can reveal their usage patterns as well as infer nonusage patterns of certain spaces at particular times, generating analyses of shared or segregated spaces. Privately owned elder-friendly facilities allow the PRC older adults to enjoy such spaces for a low membership fee. Their presence, however, reinforces the Chinese (majority) image of such facilities, unsettling ethnic minority Singaporeans who could feel excluded (e.g., language incompatibilities). Although GIS researchers might pay greater attention to where activities are conducted and transportation modes, the qualitative research draws out the exclusionary or contradictory aspects of social worlds that are characterized by class, gender, and race politics among other categories of difference, tempering one’s degree of inclusion or exclusion. Assemblage theory captures the dynamic interplay of inclusivity and exclusivity within webs of care, further conveying how care provision and reception within care assemblages is undergirded by macrostructures (in this case, those governing migrants’ status or ethnic belonging).

Drawing together these observations derived from combining qualitative and GIS methods, our conceptualization of webs of care within care assemblages incorporates another dimension beyond Wang, Li and Chai’s (Citation2012) fourfold model; namely, we drew out the tension points born out of relationally negotiated moments within activity spaces and space–time paths. The spatiotemporal negotiations just elucidated represent tension points within webs of care that could prove resilient or break under difficult circumstances. Components of care assemblages, such as state and social services, can help families manage tension points by providing an outlet for the older adults to find self-actualization, respite, or both. Foreign domestic workers also provide an additional resource, but the availability of such help depends on whether their labor is affordable, as well as the quality of care such workers can provide for different family members. Our research shows that the aging experiences and mobility patterns of older adults do not happen in silos. The resilience of tension points within webs of care is constituted through institutional, cultural, intergenerational, and interpersonal factors—extending or contracting (and even breaking) accordingly. This array of assemblage components, the relational outcomes when components come together or apart, and how tension points within webs of care are reworked determine how older adults negotiate their activity spaces and space–time paths.

This information translates into practical recommendations wherein policymakers can better attune their strategies to the lived realities of older adults by giving attention to time–space scheduling and demonstrating greater flexibility and responsiveness. The cases discussed depict consistently how older adults are called on for grandparenting duties (e.g., transporting or caring for grandchildren after school), potentially compromising time for themselves. This finding suggests that suitable and affordable child care arrangements are still lacking in Singapore (especially for younger children). Options that can be considered include enhancing flexible working arrangements for parents, providing pooled escorting for children whose homes are within walking distance from their schools, and arranging for more extensive preschool and after-school care services. Related, the timing and locations of day care services for frail older adults to whom the “young-old” have care obligations need to be synchronized with the timing of the latter’s self-care activities or other care duties. For those older adults whose care needs cannot be met within their neighborhood, transportation connectivity and affordability are crucial to enable them to receive from elsewhere the emotional and social support they need. Even so, provision and scheduling alone are inadequate. Rather, as the analytical optic of care assemblage and webs of care suggests, flexible care arrangements and policy responsiveness (e.g., preenrollment for anticipated care services; adjusting means-testing criteria for subsidies) toward changes in an older adult’s life circumstances are necessary for accommodating the contingent and dynamic aspects of webs of care.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the reviewers and to Professors Mei Po Kwan and Loretta Baldassar who had served as Academic Visitors and advisers at various junctures of this research project. Thanks as well to Dr Ick-Hoi Kim who had assisted with the Qualitative GIS research at an earlier stage of the project.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Elaine Lynn-Ee Ho

ELAINE LYNN-EE HO is Associate Professor at the Department of Geography and a Senior Research Fellow at the Asia Research Institute at the National University of Singapore, Singapore 117570. E-mail: [email protected]. Her research addresses how citizenship is changing as a result of multidirectional migration flows in the Asia-Pacific. Currently, she focuses on two domains: transnational aging and care in the Asia-Pacific and im/mobilities, transnationalism, and diaspora aid at the China–Myanmar border.

Guo Zhou

GUO ZHOU is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Department of Geography, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117570. E-mail: [email protected]. His research focuses on qualitative GIS, high-resolution satellite imagery (including land use classification, land cover change detection, and data fusion with other data sources), and 3D LiDAR point cloud (including point cloud classification and 3D reconstruction).

Jian An Liew

JIAN AN LIEW is a Research Associate at the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, Singapore 119260. E-mail: [email protected]. His research includes the intersections between migrant mobilities, class, skills, race and ethnicity, and space and place in the contexts of Singapore and London.

Tuen Yi Chiu

TUEN-YI CHIU is Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology and Social Policy, Lingnan University, Tuen Mun, New Territories, Hong Kong. E-mail: [email protected]. Her research includes migration and transnationalism, gender, marriage and family, intergenerational relations, aging, and violence in intimate relationships.

Shirlena Huang

SHIRLENA HUANG is Associate Professor in the Department of Geography, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117570. E-mail: [email protected]. Her research focuses on the intersection of migration, gender, and families (particularly on care labor migration and transnational families within the Asia-Pacific region), as well as urbanization and heritage conservation (particularly in Singapore).

Brenda S. A. Yeoh

BRENDA S. A. YEOH is Raffles Professor of Social Sciences at the National University of Singapore and Research Leader of the Asian Migration Cluster at the Asia Research Institute, Singapore 119260. E-mail: [email protected]. Her research includes the politics of space in colonial and postcolonial cities, and she has considerable experience working on a wide range of migration research in Asia, including key themes such as cosmopolitanism and highly skilled talent migration; gender, social reproduction, and care migration; migration, national identity, and citizenship; globalizing universities and international student mobilities; and cultural politics, family dynamics, and international marriage migrants.

Notes

1 Multiculturalism is constitutionally recognized in Singapore and accords equal recognition to four groups: Chinese (76 percent), Malays (15 percent), Indians (7.5 percent), and Eurasians (the last is subsumed within the category of “Others” making up 1.5 percent of the population; Strategy Group, Prime Minister's Office et al. Citation2019).

2 Subsidies are given to eligible applicants who purchase flats to live with or near parents or an adult child (see https://www.hdb.gov.sg/cs/infoweb/residential/buying-a-flat/resale/living-with-near-parents-or-married-child).

3 These provide community-based social services, usually for families in need, and are run by voluntary welfare organizations.

References

- Agency for Integrated Care. 2013. Map for eldercare service locator. https://street-directory.com/aic_site_prm/default.php/main/searchByService/region/17/service/-1. Accessed February 12, 2019.

- Anderson, B., M. Kearnes, C. McFarlane, and D. Swanton. 2012. On assemblages and geography. Dialogues in Human Geography 2 (2):171–89. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820612449261.

- Ang, A. S. 2017. I am more Chinese than you: Online narratives of locals and migrants in Singapore. Cultural Studies Review 23 (1):102–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.5130/csr.v23i1.5497.

- Bagheri, N. 2014. Mapping women in Tehran’s public spaces: A geo-visualization perspective. Gender, Place & Culture 21 (10):1285–301. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2013.817972.

- Baldassar, L., and L. Merla, eds. 2014. Transnational families, migration and the circulation of care. London and New York: Routledge.

- Bélanger, D., and G. Candiz. 2019. The politics of “waiting” for care: Immigration policy and family reunification in Canada. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (16):1–19. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1592399.

- Bowlby, S. 2012. Recognizing the time–space dimensions of care: Caringscapes and carescapes. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 44 (9):2101–18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1068/a44492.

- Bowlby, S., L. McKie, S. Gregory, and I. MacPherson. 2010. Interdependency and care over the lifecourse. London and New York: Routledge.

- Bunnell, T., S. Yea, L. Peake, T. Skelton, and M. Smith. 2012. Geographies of friendships. Progress in Human Geography 36 (4):490–507. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132511426606.

- Chaix, B., Y. Kestens, C. Perchoux, N. Karusisi, J. Merlo, and K. Labadi. 2012. An interactive mapping tool to assess individual mobility patterns in neighborhood studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 43 (4):440–50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.06.026.

- Chan, D. V., C. A. Helfrich, N. C. Hursh, E. S. Rogers, and S. Gopal. 2014. Measuring community integration using geographic information systems (GIS) and participatory mapping for people who were once homeless. Health & Place 27:92–101. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.12.011.

- Closs-Stephen, A., and V. Squire. 2012. Politics through a web: Citizenship and community unbound. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 30 (3):551–67. doi: https://doi.org/10.1068/d8511.

- Conradson, D. 2005. Landscape, care and the relational self: Therapeutic encounters in rural England. Health & Place 11 (4):337–48. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2005.02.004.

- Delyser, D., and D. Sui. 2014. Crossing the qualitative–quantitative chasm III: Enduring methods, open geography, participatory research, and the fourth paradigm. Progress in Human Geography 38 (2):294–307. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513479291.

- De Silva, M. 2017. The care pentagon: Older adults within Sri Lanka–Australian transnational families and their landscapes of care. Population, Space and Place 23 (8):e2061. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2061.

- Dombroski, K., K. McKinnon, and S. Healy. 2016. Beyond the birth wars: Diverse assemblages of care. New Zealand Geographer 72 (3):230–39. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/nzg.12142.

- Elwood, S., and M. Cope. 2009. Introduction: qualitative GIS: forging mixed methods through representations, analytical innovations, and conceptual engagements. In Qualitative GIS: a mixed methods approach, ed. S. Elwood and M. Cope, 1–10. London: Sage.

- Epp, A. M., and S. R. Velagaleti. 2014. Outsourcing parenthood? How families manage care assemblages using paid commercial services. Journal of Consumer Research 41 (4):911–35. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/677892.

- Franke, T., M. Winters, H. McKay, H. Chaudhury, and J. Sims-Gould. 2017. A grounded visualization approach to explore sociospatial and temporal complexities of older adults’ mobility. Social Science & Medicine 193:59–69. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.09.047.

- Hirsch, J. A., M. Winters, P. Clarke, and H. McKay. 2014. Generating GPS activity spaces that shed light upon the mobility habits of older adults: A descriptive analysis. International Journal of Health Geographics 13:1–14. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-13-51.

- Ho, E. L. E. 2019. Citizens in motion: Emigration, immigration and re-migration across China’s borders. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Huff, A. D., and J. Cotte. 2016. The evolving family assemblage: How senior families. European Journal of Marketing 50 (5–6):892–915. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-02-2015-0082.

- Jones, P., R. Drury, and J. McBeath. 2011. Using GPS-enabled mobile computing to augment qualitative interviewing: Two case studies. Field Methods 23 (2):173–87. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X10388467.

- Jung, J. 2009. Computer-aided qualitative GIS: A software-level integration of qualitative research and GIS. In Qualitative GIS: A mixed methods approach, ed. M. Cope and S. Elwood, 115–35. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Knigge, L., and M. Cope. 2006. Grounded visualization: Integrating the analysis of qualitative and quantitative data through grounded theory and visualization. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 38 (11):2021–37. doi: https://doi.org/10.1068/a37327.

- Kwan, M. P. 2012. The uncertain geographic context problem. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 102 (5):958–68. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2012.687349.

- Kwan, M. P., and G. Ding. 2008. Geo-narrative: Extending geographic information systems for narrative analysis in qualitative and mixed-method research. The Professional Geographer 60 (4):443–65. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00330120802211752.

- Kwan, M. P., and L. Knigge. 2006. Doing qualitative research using GIS: An oxymoronic endeavor? Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 38 (11):1999–2002. doi: https://doi.org/10.1068/a38462.

- Kwan, M. P., and J. Lee. 2004. Geovisualization of human activity patterns using 3D GIS: A time-geographic approach. In Spatially integrated social science, ed. M. Goodchild and J. Donald, 48–66. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Mennis, J., M. J. Mason, and Y. Cao. 2013. Qualitative GIS and the visualization of narrative activity space data. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 27 (2):267–91. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13658816.2012.678362.

- Milligan, C. 2009. There’s no place like home: Place and care in an ageing society. Surrey, UK: Ashgate.

- Milligan, C., and J. Wiles. 2010. Landscapes of care. Progress in Human Geography 34 (6):736–54. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510364556.

- Milton, S., T. Pliakas, S. Hawkesworth, K. Nanchahal, C. Grundy, A. Amuzu, J. P. Casas, and K. Lock. 2015. A qualitative geographical information systems approach to explore how older people over 70 years interact with and define their neighbourhood environment. Health & Place 36:127–33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.10.002.

- Naybor, D., J. P. H. Poon, and I. Casas. 2016. Mobility disadvantage and livelihood opportunities of marginalized widowed women in rural Uganda. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 106 (2):404–12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2015.1113110.

- Power, E. R. 2019. Assembling the capacity to care: Caring-with precarious housing. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 44 (4):763–77. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12306.

- Razavi, S. 2007. The political and social economy of care in a development context. Conceptual issues, research questions and policy options. Gender and Development Paper 3, United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Schönfelde, S., and K. W. Axhausen. 2003. Activity spaces: Measures of social exclusion? Transport Policy 10 (4):273–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2003.07.002.

- Sherman, J. E., J. Spencer, J. S. Preisser, W. M. Gesler, and T. A. Arcury. 2005. A suite of methods for representing activity space in a healthcare accessibility study. International Journal of Health Geography 4 (1):1–21.

- Singapore Department of Statistics. 2017. Population trends 2017. https://www.singstat.gov.sg/-/media/files/publications/population/population2017.pdf (accessed February 22, 2020).

- Singapore Department of Statistics. 2019. Elderly, youth and gender profile. Accessed February 22, 2020.

- Strategy Group, Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore Department of Statistics, Ministry of Home Affairs, Immigration and Checkpoints Authority and Ministry of Manpower. 2019. Population in brief. Accessed February 22, 2020. https://www.strategygroup.gov.sg/files/media-centre/publications/population-in-brief-2019.pdf.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2019. International migrant stock: Country profile: Singapore. Accessed February 20, 2020. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/countryprofiles.asp.

- Wang, J., M. P. Kwan, and Y. Chai. 2018. An innovative context-based crystal-growth activity space method for environmental exposure assessment: A study using GIS and GPS trajectory data collected in Chicago. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15 (4):1–24. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15040703.

- Wang, J., F. Li, and Y. Chai. 2012. Activity spaces and sociospatial segregation in Beijing. Urban Geography 33 (2):256–77. doi: https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.33.2.256.