?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This article develops a mechanism for automatically classifying rewarded collaboration proposals. The research’s purpose is to increase transparency in the rewarded collaboration process, thereby inviting more collaboration proposals, to aid in the fight against criminal organizations. The research focuses on critical facets of the public security system and of the organized crime in Brazil. Through rewarded collaboration, a new approach to plea bargaining is achieved that helps detect, disrupt, and ultimately dismantle illicit operations. This multi-criteria approach enables the consideration of the interests of detainees, the priorities of police institutions, and the perspective of the community. This approach results in the formation of a holistic understanding of the issue, taking into account the costs and benefits to society of punishing defendants whose guilt can be established. Composition of Probabilistic Preferences Trichotomic is the multi-criteria method employed to take imprecision into consideration while performing classification into predetermined classes. It enables the evaluation of each proposal independently. This boosts the system’s objectivity and consequently its attractiveness. Taking the interaction between the criteria into consideration, the analysis naturally applies to any number of evaluation criteria and individuals involved in the investigated crimes. Novel forms of interaction modeling are compared in practical instances.

1. Introduction

Brazil's justice system is grappling with both prison overcrowding and social pressure to increase productivity in the administration of criminal cases (Kovač and Bezerra, Citation2020; Biehl et al., Citation2021). To lessen the burden or overcome the prosecution's inability to increase its knowledge sufficiently to effectively punish the leaders of criminal organizations, a wise alternative is to promote the collaboration of caught individuals (Gonzalez-Ocantos and Hidalgo, Citation2019; Fishlow, Citation2020).

The rewarded collaboration mechanism arises to address instances in which an authority is aware of the involvement of multiple individuals in an unsolved crime. The law agents offer benefits such as the deferral of a procedure or a reduction in the penalty in exchange for a confession implicating more serious criminals. As a result of the arrangement, the agreement lessens the penalty for the collaborator while achieving elements that will enable the prosecution of other culprits.

Precisely, a proposal for rewarded collaboration is understood here as a document in which a person charged with a crime reports the occurrence in detail, accepting responsibility for its own role and describing the involvement of others, while requesting for a reduced penalty in compliance with the law.

In a broader sense, rewarded collaboration is a means of bridging the divide between marginality and legality for the sake of societal pacification. At the same time, collaboration with justice of persons with a better knowledge about criminal practice enhances the likelihood of success in combating powerful gangs (Luz and Spagnolo, Citation2017; Kanner et al., Citation2019, p. 502).

However, the new system has thus far drawn only collaborators from Brazil's upper social strata (Nishijima et al., Citation2019; Limongi, Citation2021). The initiative to collaborate carries significant risks if it is rejected (Meszaros, Citation2020; Pardieck et al., Citation2020). If acceptance is discretionary, the potential collaborator of humbler origins cannot help but suspect that authorities, despite their best intentions, are prone to agree with other participants in criminal episodes who are also members of their higher socioeconomic strata.

To foster collaboration, it is critical to establish an objective and transparent process for evaluating collaboration proposals (Schneider and Alkon, Citation2019; Turner, Citation2020). While Schneider and Alkon (Citation2019) place greater emphasis on the discretion granted to prosecutors in charging decisions, which increased transparency helps to limit, Turner (Citation2020) values the ability of transparency to prevent disparate treatment of defendants in comparable cases.

Regarding the lack of transparency in the United States’ plea bargaining institute, Turner (Citation2020, p. 975) makes the following points:

Unlike the trials it replaces, plea bargaining occurs privately and off the record.

Victims and the public are excluded from the negotiations, and even the defendant is typically absent. Plea offers are often not documented, and the final plea agreements are not always in writing or placed on record with the court.

Plea hearings—at which a judge reviews the validity of a defendant’s guilty plea—are public, but they tend to be brisk, rote affairs that often fail to reveal all of the concessions exchanged between the parties.

As a result, plea bargaining is largely shielded from outside scrutiny, and critical plea-related data are missing.

All of these considerations evidence the importance of precisely defining the decision rules. For the defendant, it is unappealing to engage in negotiations where the outcome is contingent on legal issues in which the opposing party has vastly superior knowledge. Additionally, requiring objective evaluation prior to accepting a proposal improves the quality of the proposals and stimulates proposers to include as much information as possible.

Recent articles have registered the utility of operations research techniques for addressing problems pertaining to public security. For instance, Konrad et al. (Citation2017), Baycik et al. (Citation2018), Basilio et al. (Citation2019) and Anzoom et al. (Citation2022) discuss the use of a variety of operations research techniques to disrupt various types of criminal networks. The present study opens a new vein in this field by using the Composition of Probabilistic Preferences (CPP) multi-criterion decision analysis method to introduce uncertainty components in the handling of collaboration proposals.

Sant'Anna et al. (2020) formulate the collaboration rewarding decision as a multicriteria negotiation (Raiffa, Citation1982), in which alternatives are identified by a variety of attributes. Among these attributes are the proper penalties assigned to each member of the group of defendants with different involvement in the case, as well as the costs to the authority and the benefits to society associated with concluding the elucidation of the case to properly punish those involved.

In multi-criteria decision analysis, the criteria are a subset of the attributes that characterize the alternatives of a problem. Among all these attributes, in general, only a few are really considered by the decision maker. Criteria can be selected by protocols or best practices pertaining to the problem, or even by personal choice of decision makers or a group of experts (Inotai et al., Citation2018; Roza et al., Citation2020).

In the present problem, the first part of the criteria comes from the motivation of the collaboration proponents to reduce their penalties. Each of these criteria is based on a single attribute, the length of the prison sentence – each potential perpetrator wishes to keep it as brief as possible.

To these criteria, a criterion representing the cost to the entity to which the collaboration proposal is addressed of the investigation that will be required to validate the information offered in the proposal is naturally added. Other criteria assess the collaboration's ability to effectively benefit the community.

To begin, the proposal must be evaluated by its ability to weaken criminal organizations through the dismantling of links in their chain of command. In economic crimes, for example, in addition to bringing the perpetrators to justice, certain information can aid in the derailment of money laundering schemes, tax fraud, and the corruption of agents who assist criminal organizations.

The proposal's potential relevance can also be determined by examining its internal coherence or compatibility with what is known about the case. If the proposal contains inconsistencies or contradicts publicly available information about the proposers' background, it will receive a lower rating under this last criterion.

Beginning with the transformation of attribute measures into probabilities of preference, CPP enables the consideration of the interaction between the criteria. This allows for the inclusion of a broad range of criteria. It also enables consideration of the social interest in selecting the solution that maximizes the satisfaction of all stakeholders through the use of a Choquet integral (Choquet, Citation1953), which combines the probabilities of optimization according to all criteria while accounting for their interaction.

To enable a separate analysis of each proposal, a classification variant of CPP called the trichotomic CPP or CPP-Tri (Sant'Anna et al., 2015) is used. Its structure presupposes that an ordered set of classes has been previously identified. The evaluation procedure entails determining the class into which the proposal should be classified. This is accomplished by comparing the vectors of its evaluations according to the multiple criteria to representative profiles of the classes. The dissemination of information about these profiles will have the side effect of boosting confidence in the system's independence from subjective influences.

Additionally, this approach allows for the use of probabilistic composition rules. The variability that this induces serves to limit subjective deviations of the decisions toward predetermined solutions. In the same direction, goes the feature of Choquet integration of giving greater importance to concordant evaluations by criteria presenting greater positive interaction and, in contrast, giving negative influence to contradictions between evaluations by criteria to which positive interaction is assigned and to concordances between evaluations by criteria with negative interaction.

This article will continue as follows. In the following section, the main features of CPP-Tri are described. Section 3 develops the strategy proposed for the collaboration proposals classification. This section begins with a brief illustration of a case of conflicting collaborators based on the prisoner’s dilemma (Straffin, Citation1980). Following this, the concepts of classes, criteria, composition rules, the format of the proposal, and the value generation process are detailed. Section 4 then provides numerical examples of application. Section 5 concludes the article by highlighting the most significant qualities of the novel model.

2. CPP-Tri

CPP is a methodology that incorporates the probabilistic nature of preference evaluation into the composition of multiple criteria. This probabilistic character can arise as a result of imprecision caused by subjective factors, which cause decision-makers to attribute different meanings to the same attributes of alternatives under different circumstances, or as a result of measurement errors that affect the evaluations of such attributes.

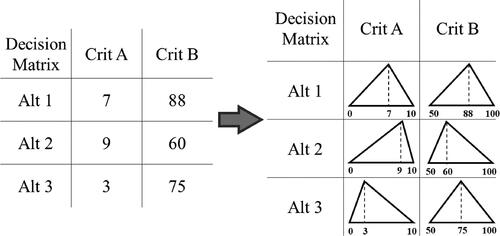

A critical step in CPP is the transformation of the numerical vector containing the evaluations of the various alternatives according to each criterion into a vector containing preference probabilities. This transformation of exact values into probabilities is illustrated in , where a triangular distribution emulates the preferences of an expert. Each exact value becomes the mode of a preference distribution, which varies between the extremes of the evaluations by the criterion. In this example, criterion A ranges from 0 to 10, while criterion B ranges from 50 to 100.

The final preference scores can be derived by combining these probability distributions using probabilistic aggregation rules. Classic aggregation rules employ a linear combination of individual scores (Fishburn, Citation1970), which, in the probabilistic context, can be thought of as the combination of the preference probabilities for each criterion conditional on the preference for that criterion. The linear combination's weights are then the marginal probabilities associated with each criterion chosen.

Due to the possibility of interaction, linearity can be extremely restrictive. The combination of criteria can be performed more generally using a Choquet integral rather than a total probability, with the importance of the criteria sets indicated by a capacity (Choquet, Citation1953) and the interaction being measured by Shapley values (Shapley, Citation1953).

A necessary condition for the use of a Choquet capacity in the combination of multiple criteria assessments is the commensurability of the criteria. This condition is ensured by the initial stage of the CPP's conversion of the numerical evaluations according to the criteria into probabilities.

To determine the capacity, we can rely on the opinion directly expressed by the decision-maker (Grabisch et al, Citation2008). To alleviate reliance on this opinion, the principle of concentration of preferences (Sant’Anna and Sant’Anna, Citation2019) can be used to extract information about capacity indirectly from the evaluation by the criteria.

CPP-Tri is a variant of CPP that is applicable if evaluation vectors representative of each element of a set of ordered classes can be determined. After that, the alternatives are compared to these vectors, which are referred to as representative profiles.

The use of representative profiles is fundamental in the identification of ordered classes in CPP-Tri. Each class is uniquely identified by a single profile or by a set of distinct profiles. The profiles must correspond to vectors of evaluations of genuine alternatives by the criteria. These evaluations indicate levels of satisfaction with the alternative according to the criteria that collectively represent better or worse conditions.

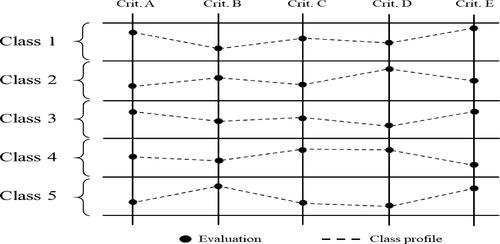

The representation by the probabilities of preference according to each criterion simplifies the comparison: we may use a single profile for each class and identify each class by numerical levels in the probabilities of preference. illustrates the situation of five classes with one profile per class.

Allocation of an alternative within a class is then determined by the similarity of its vector of assessments by the multiple criteria to each representative profile (with proximity measured by a rule that takes interactions into account). Thus, for instance, an alternative is assigned to the highest preference class if the distance between its vector of multiple criteria evaluations and the representative profile with the highest probabilities of satisfying the criteria is smaller than the distance between its vector of multiple criteria evaluations and any other vector of representative profile used.

After the comparison is performed using probabilistic measures of the similarity of each alternative to each profile, if the objective is to choose the best alternative or to completely ordering the best alternatives, the analysis continues by applying CPP to the alternatives placed by CPP-Tri in the upper or lower class, depending on the orientation of the criteria.

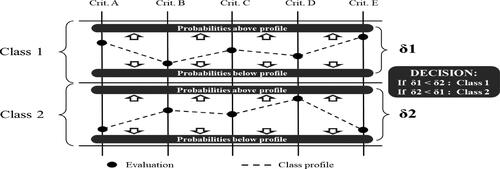

CPP-Tri evolves in successive steps. First, the probability that the distribution representing the evaluation according to each criterion assumes values above and below the respective coordinate of the representative profiles is estimated. These probabilities according to each criterion are then aggregated into probabilities according to the set of all criteria. Finally, to identify the class in which the alternative will be placed, the minimum of the differences between the estimates of the joint probabilities of being above or below the profiles is determined. illustrates this procedure, considering two classes.

Formally, in an additive composition with a single representative profile for each class (Sant’Anna et al., Citation2015), for i denoting the class, j denoting the criterion, cij denoting the jth entry of the representative profile of the ith class, wkj denoting the weight assigned to the jth criterion in the evaluation of the kth alternative and Xkj denoting the random variable associated with the evaluation of the kth alternative by the jth criterion, the classification procedure begins with the calculation of the probabilities

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

The joint probabilities of each alternative being above or below the profile of each class are then estimated:

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

The classification proceeds with the calculation of the distances

(5)

(5)

The kth alternative is classified in the i0–th class if

(6)

(6)

In a more general formulation, the linear combinations in Equation(3)(3)

(3) and Equation(4)

(4)

(4) may be replaced by Choquet integrals of {Ai1k-, …, Aink-} and {Ai1k+, …, Aink+} with respect to Choquet capacities CLik and CHik.

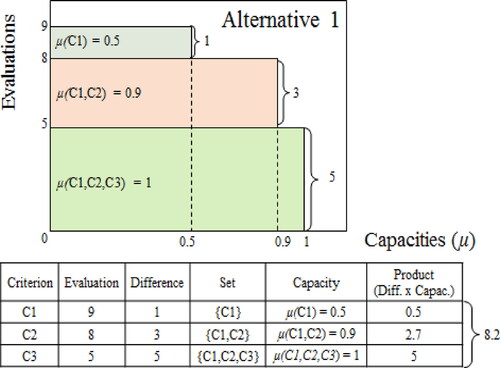

The Choquet integral of a vector (x1, …, xn) with respect to a capacity y on {1, …, n} is given by

(7)

(7)

for τ denoting a permutation of {1, …, n} such that

≤

≤…≤

≤

and

=0.

This is equivalent to

(8)

(8)

for z(j) = {j, . ., n} for all j from 1 to n and z(n+1)=0.

depicts the computation of a Choquet integral for a generic Alternative 1, evaluated by three criteria. In this example, the aggregate value of Alternative 1 as determined by the Choquet integral equals 8.2. This value, that is greater than the mean of the values 5, 8 and 9, indicates the performance of the alternative according to capacities of the sets, which consider not only isolated weights of criteria but also interactions between criteria.

3. Modeling the rewarded collaboration

The possibility of a defendant's sentence being reduced in exchange for information has existed in Brazilian law for a lengthy amount of time. The most notable example is a provision in Law 8.072/1990 (Heinous Crimes Law) that reduces the penalty for a defendant who informs authorities about a kidnapping, thereby facilitating the kidnap victim's release. Additionally, defendants are eligible for penalty reductions under Law 7492/1986 (White Collar Crimes Law) and Law 9613/1998 (Money Laundering Law). However, the systematic use of sentence reduction was only recently regulated by Law 12.850/2013 (Organized Crime Law) and its subsequent amendment by Law 13.964/2019 (Anti-Crime Law).

The Anti-Crime Law defines rewarded collaboration as a negotiation within the legal process and a means of obtaining evidence. This implies, on the one hand, that it is part of the criminal prosecution and, on the other, that it does not need to include legal evidence, but only to present means of obtaining evidence. The defendants in the proposal must explain how to locate the evidence, but are not required to provide it directly. It will be up to the defendants to prepare the proposal and attach to it an appropriate description of the facts, including all relevant circumstances and evidence of which they are aware.

To be accepted, the collaboration must contribute to the following: (i) identification of other participants in the criminal organization and crimes committed by them, (ii) dissemination of the criminal organization's hierarchical structure and task division, (iii) prevention of criminal offenses committed by the criminal organization, (iv) total or partial recovery of the product or benefit resulting from criminal offenses committed by the criminal organization or, finally, (v) location of possible victims.

A criterion that must be added to the criteria related to the defendants' interest in minimizing their sentences through collaboration in the elucidation of the crime is derived from the administration of justice's interest in minimizing the effort required to prove the information provided in the collaboration proposal. Another criterion is associated with the significance of the information contained in the proposal, once validated, to the dismantling of criminal organizations. The proposal can also be evaluated by its consistency and absence of internal contradictions. Other criteria may be added.

The number of potential defendants may differ from the number of criteria brought by the administration of justice, generating an imbalance between the interests of these two parties. This numerical difference becomes less important when composition rules that adequately account for interaction are used. Hypotheses about the interaction between the criteria in different groups can guide the modeling of a capacity with respect to which the composition by a Choquet integral is suitably carried out.

In the multi-criteria approach, the interests of all – the accused, the administration of justice, and the society as a whole applying a composition rule that conciliates such conflicting interests – guide the modeling of the rewarded proposals analysis. The multi-criteria approach also helps in making the participants find themselves represented and, simultaneously, recognize the importance of other interests being met.

3.1. Initial model formulation

Before delving deeper into the model's complexities, to illustrate the concepts involved, let us analyze the concrete case known as the “prisoners' dilemma”.

In this case, the resource currently employed to elicit information from the accused regarding the involvement of others is exploited to the fullest extent possible: it consists of eliminating all feasible communication channels between the accused.

This has been accomplished in Brazil through the preventative detention mechanism, sometimes exceeding the legal limits imposed to safeguard the citizen's fundamental right not to being imprisoned prior to conviction in accordance with the presumption of innocence.

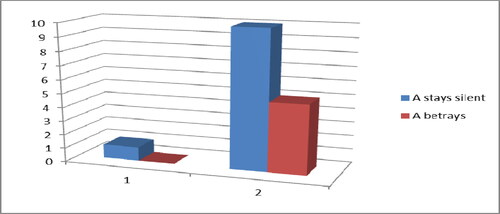

The “prisoner's dilemma” is a well-studied problem in game theory. Two agents are detained for minor involvement in a felony punishable by up to a year in jail. It is desired to discover who committed a serious offense. Each agent is presented with the following:

You have a choice between confessing and remaining silent. If you confess (i.e., betray your accomplice) and your partner remains silent (i.e., protects you), all charges against you will be dropped and you will be released. Your testimony will be used against your accomplice, who will receive the highest sentence allowed under the law for the offense (10 years in prison, say). If, in contrast, you remain silent while your companion confesses, your partner will be released while you will face the maximum penalty. If both of you confess, you will receive an average sentence (5 years each). If both of you remain silent, you will each receive a lighter sentence (1 year) for the less serious offense that has already been proven.

In this way, the captives betray one another, despite the fact that they would both benefit from remaining silent.

The initial criteria for the case's multi-criteria formulation are connected to the accused's desire to have their sentences reduced. The first criterion is a variable whose value decreases as the penalty for the first accused decreases. The second is a variable whose value decreases as the penalty for the second accused decreases.

The alternatives to the problem, in turn, are determined by the decisions to collaborate of each of the accused. Combining the individual's decisions to denounce or not denounce each other yields four possible alternatives. They are represented by vectors that initially include only these two coordinates, which correspond to the values of the penalties imposed on each defendant if the alternative materializes.

Inasmuch as separation of the accused logically compels them to inform, on the other hand, to avoid resorting to separation, it is conceivable to make the decision contingent on a third criterion: the cost to the Prosecution resulting of not getting information through the collaboration. In this instance, the alternatives are represented by vectors of three coordinates, the two previous ones with the values of the penalties and the third one with the cost for the administration of justice associated with the behavior of the accused that constitute the alternative.

Due to the fact that the criteria are binary variables, the possible interaction between them is determined solely by the higher or lesser importance assigned to the pair of concordant or discordant values in the alternative. Thus, for instance, there is negative interaction between the two criteria if the importance assigned to a vector with the same value in both coordinates (either representing the concordant decisions of the two accused to present a delation, or representing the concordant decisions of not presenting) is reduced.

A hypothesis of negative interaction between these two criteria stems from the idea that information about an accused’s behavior, whatever it may be, allows for the assumption that the other will exhibit that same behavior, implying that information about the pair's behavior is secondary to that about each individual element of the pair.

Additionally, a rationale for a positive interaction between any of the penalty criteria and the cost for the administration may be derived from the expectation of a high degree of complementarity between the information about the penalties in the collaboration proposals and the information about the burden borne by the authority responsible for determining the accused persons’ guilt.

3.2. Classes

To start we must determine the number of classes. Five classes are utilized. This number is frequently used in practice because it enables the identification of two extreme positions, a central position and two intermediate positions between the central position and each extreme. This maintains a sufficient distance between the positions while also allowing for precision in assigning values to a neutral position, a mild disagreement with neutrality, and the opposing extremes. A larger number of classes, even though resulting in a better fit of a normal distribution to the distribution of the number of alternatives assigned to each class (Leung, Citation2011), will be more difficult to apply, increasing the possibility of assignment errors.

Each class is identified by a single representative profile. The profiles are constructed using the values of quantiles 1/8, 1/4, 1/2, 3/4 and 7/8. In a simpler construction, with only three classes, the classes are typically identified by the observed quartiles and the median. For five classes, we divide each extreme segment into two segments of equal probability with the inclusion of the quantiles 1/8 and 7/8.

The evaluation according to each criterion is given by a value for the alternative that falls within a range of values that this numerical evaluation is supposed to achieve. This information gives rise to a probability distribution. In the absence of additional information on the peculiarities of this distribution other than the assigned value and the minimum and maximum permissible values, a triangular distribution with the mode at the observed value and extremes at the maximum and the minimum is assumed. Instead of the triangular distribution, it may also be recommended to use its smoothing by a beta-PERT distribution.

To make comparing the criteria easier, it is convenient to translate all the distributions to [0, 1], so ensuring that the same scale applies across all criteria. With five classes and one profile for each class, fixing the profiles in the quantiles 1/8, 1/4, 1/2, 3/4 and 7/8 and assuming the triangular distribution, we arrive at constant values of 0.25, 0.35, 0.5, 0.65 and 0.75, respectively, for all the coordinates of each of the five profiles. As the criteria are constructed with preference for the lowest values, the profiles are ordered from lowest to highest, so that Class 1, the most preferred, has the profiles with entries 0.25 and Class 5 has the profiles with entries 0.75.

In principle, proposals allocated in Class 1 are accepted, with, if this class is empty or anyhow this pattern is deemed excessively exacting, additional acceptance of proposals allocated in Class 2.

3.3. Criteria

The number of criteria will be a variable n, with a maximum value of six in the following analysis, but easily extendable. To simplify, a classification is initially presented with only three criteria, two of which correspond to the penalties on two defendants and the criterion CRIM.ORG, related to the dismantling of criminal organizations. Then, four criteria are applied, three based on the penalties on three defendants and, again, evaluation of the benefit to the fight against criminal organizations. In the sequence, the criterion related to the workload in additional fact-finding is added. Finally, the criterion of the presence of contradictions and inconsistencies in the proposal is added.

The penalty criteria are measured by the approximate number of years in prison. An objective attribute to measure the criterion of workload to explore the information in the proposal is the expected time required for a specialized team to deepen the investigation, validating the evidence that allows prosecuting with high hope of conviction criminal proceedings against all those involved. Dismantling criminal organizations may be assigned values from zero to three. Zero corresponding to complete effect and three to absolute inefficacy, with values one and twocorresponding to intermediate effects nearer to one or other of these two extremes. For the last criterion values of zero for the absence of inner contradictions and of contradictions to registered evidence, one for the presence of one of these two types of contradictions, and two for the presence of both of them are used.

3.4. Composition rules

To assess the composition rule's influence, this study compares the results of applying different rules based on three different interaction assumptions.

In the first form of composition, assuming null interactions, the principle of weighting proportionally to the observed values is applied. It leads to the probability Lk of the alternative with the vector of evaluations by the n criteria given by (c1, …, cn) being considered below the kth class, with the representative profile having an equal entry qk for each of the n criteria, proportional to the sum of the squares of the Fs(qk) for Fs denoting the cumulative distribution of a random variable with the mode at cs. Similarly, the estimate of the probability Hk of this alternative being above the kth class will be proportional to the sum of the squares of the 1-Fs(qk). Indeed, the vectors of probabilities to be linearly combined are in the first case (F1(qk), …, Fn(qk)) and in the second (1- F1(qk), …, 1- Fn(qk)).

In the second form of composition, maximum negative interaction between all criteria is assumed. This leads to assigning to each set of criteria a capacity proportional to the maximum of the evaluations by criteria of the set. That is, for any s ≤ n, the capacity of a set of criteria {Cj1, …, Cjs} whose elements assign to the alternative being evaluated the values cji, …, cjs, respectively, is given by max(cj1, …, cjs)/max(c1, …, cn).

Finally, in a third form of composition, maximum negative interactions are assumed only between the penalty criteria. In the sets that include any other criterion maximum positive interaction is assumed, that is, each of these sets of criteria is assigned a capacity equal to one.

3.5. Alternatives

The eight alternatives compared in Sant'Anna et al. (2020) are here analyzed separately. Some of them correspond to proposals submitted by multiple proponents, which may be interesting to admit in circumstances such as those discussed in Section 3.1.

The first alternative was created as a benchmark, not corresponding to a defendant's proposal. For this alternative, costs and benefits are calculated assuming no collusion between defendants. A median sentence of 4 years in prison for all suspects is used. It is expected that such penalties can be met without incurring additional investigation costs, but also without favoring the combat against crime. When the proposal consistency criterion is included, it receives the lowest value, to reflect the lack of information provided by proposers.

The following three alternatives correspond to equivalent proposals in which one of three suspects provides information that enables an increase in the sentences of the others. Average values are assigned to the other criteria, of deranging criminal organizations, effort required for validation and coherence.

Three other alternatives represent allegiances between two of three defendants. In each of them, the proposal is made by two suspects leading to the maximum in the sentence of the third. One of these proposals is distinguished by offering the maximum damage to the criminal organizations whereas the other two have, for this criterion, the same median level of the previous proposals. All three are structured with no contradictions, but require greater investigative effort to verify the greater volume of information offered by the two proponents.

Finally, a last alternative is designed, involving a proposal made jointly by three suspects, who achieve a greater reduction in their sentences. This reduction is associated with the notion that, by presenting a narrative agreed upon by all, the accused can evade conviction for some part of the crime investigated. On the other hand, this proposal makes the greatest possible contribution to the fight against organized crime. This alternative is also associated with a high cost of confirming its greater detail and with high consistency.

4. Data analysis

This section is intended to provide practical evidence on the feasibility of the multi-criteria approach and of its ability to introduce uncertainty into the evaluation of proposals. The R software (R Core Team, 2018) and, in particular, the CPP package (Gavião et al., Citation2018) are used to analyze the proposals described in Section 3 using CPP-Tri. The procedures designed to integrate these tools are all available in Sant’Anna (Citation2023), archived in Zenodo. A pseudocode and an example of proposal classification are provided in an online supplemental file to this article.

The evaluations of the eight proposals by the six criteria are given in . Each row of describes one proposal. The columns Penalty1, Penalty2 and Penalty3 present the number of years in prison for each of the three suspects. The three last columns quantify the proposal's impact on the dismantling of the criminal organization, the investigation costs resulting from the proposal acceptance and its level of inner contradictions, respectively.

Table 1. Characterization of eight Proposals by evaluations according to six criteria.

For a defendant, a low value in the respective penalty is favorable. For the justice administration, a low value in each of the other three criteria is advantageous. The proposal evaluation is then based on joint minimization.

Examining reveals that Proposal [1] is the best from the perspective of workload. Proposals [2], [3] and [4] are the best from the perspective of the defendant presenting them, Proposals [5], [6] and [7] are the best from the perspectives of two proponents and consistency, and Proposal [8] is the best from the perspectives of dismantling the criminal organization and consistency.

Proposals [2], [3] and [4] are identical, only changing the authorship of the proposal, as are Proposals [5] and [6]. Thus, there are five different types of proposals to be analyzed.

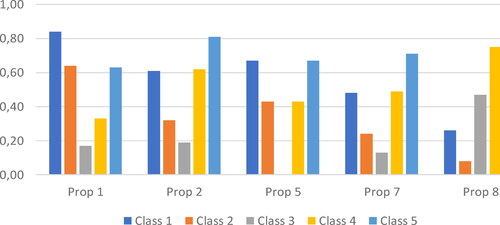

To facilitate comparisons, the evaluations are converted to the interval [0,1]. displays the conversion results obtained by subtracting the minimum and dividing by the range, for one proposal of each type.

Table 2. Translation of evaluations to the interval [0, 1].

Plausible hypotheses of interaction are negative interaction between the penalty criteria, which entails assigning less importance to joint low values for penalties, and positive interaction when other criteria are involved, which entails assigning more importance to proposals that combine low penalties with desirable values for the administration goals’ criteria. Other two capacities considered for comparison are easier to identify: the linear, with no interaction between any two criteria, and another with maximal negative interaction between any two criteria.

An initial application with only three criteria enables easy visualization of the successive stages of the evaluation. In this instance, the Choquet capacity is determined by only six values, those of the capacities of the three individual criteria and of the three pairs of criteria. The three criteria used are the sentencing levels for two defendants and the benefit of dismantling the criminal organizations. The alternatives are then identified by the values of the columns Penalty1, Penalty3 and CRIM.ORG of .

The first computation is of the complementary probabilities of each evaluation by one criterion being above or below the respective coordinate of the representative profile of each class. With five alternatives, five classes and three criteria, a total of 150 probabilities are computed.

Following, for every proposal, from the vectors of three probabilities of being above (or below) the profiles five Choquet capacities are derived.

The Choquet integrals with respect to these capacities are then utilized to calculate estimates for the probabilities of the proposal being ranked above and below each class.

Minimizing the absolute value of the differences between the probabilities of the alternative being ranked above and below each class completes the classification.

displays the absolute values of the differences obtained by applying the capacities determined under the assumption of maximal negative interaction between the penalty criteria and maximal positive interaction between each penalty criterion and the criterion of criminal organization weakening.

Table 3. Scores for the five alternatives based on three criteria.

depicts the absolute differences in . It evidences the minimum value, which determines the class, clearly away from the next values.

As the lowest value in the last column of is in the row corresponding to Class 2, Proposal [8] is classified in that class. The other proposals have the lowest score in the next row and are thus classified in Class 3.

The same result is obtained for all other forms of capacity composition considered, except for Proposal [2] for the capacity corresponding to maximal negative interaction between all pairs of criteria and for Proposal [7] for the assumption of no interaction, which are both classified in Class 2 instead of Class 3.

It is interesting to note in , the null entry for Proposal [5] for Class 3. This is explained by the perfect balance in the comparisons between the evaluations 0, 1 and 1/2 for Proposal [5] and the representative profile of Class 3 with the three coordinates equal to 1/2.

Identical analyzes were conducted with the successive inclusion of one more proponent, the investigation workload criterion and the consistency criterion. The classifications obtained are summarized in . In this table, for each group of columns identified by the number of criteria, the first column presents the classification by composition without interactions, the second column the classification by composition with maximal negative interactions and the third column the classification by composition with maximal negative interaction between penalties and maximal positive interaction otherwise.

Table 4. Classification by different composition rules.

It can be seen in that the addition of one more proponent has no effect on the classifications. In fact, with four criteria, as with three criteria, only the last proposal reaches Class 2 in all forms of composition, whereas Proposals [2] and [7] only reach Class 2 for one composition rule, and the other proposals remain in Class 3.

When five criteria are used, some proposals move from Class 2 to Class 3, without any proposal moving from Class 3 to Class 2. For Proposals [7] and [8], the inclusion of the investigation workload criterion, in which they received a poor evaluation, results in a loss. Only in the composition without interaction, does Proposal [8] remain in Class 2.

It can be seen then that, with the profiles established, no proposal is located in Class 1, but some proposals are frequently in Class 2, where acceptance is possible. This is especially true for the last proposal, the one with low penalties for all defendants and the best evaluations by the criteria of weakening criminal organizations and inner consistency, even though with the worst evaluation by the workload criterion.

Because the evaluation is not comparative, proposals [1] and [5], despite being dominated by other proposals, are eligible for high preference classes. However, this does not occur, indicating that they do not meet the standards established by means of the representative profiles adopted.

In a summary, the obtained results demonstrate the feasibility of the analysis. In addition, it is seen that changes in the composition rules led to minor classification effects.

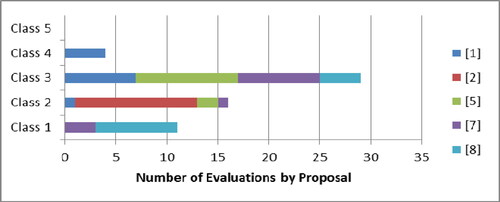

The smoothing of the triangular distribution by the Beta-PERT was also applied. It also leads to few changes in the final results, with Class 3 remaining as the modal class and no move of more than one class up or down. A widening in the classification then occurs, with some proposals moving from Class 2 to Class 1 and others moving from Class 3 to Class 2 or Class 4. Thus, for example, in the classifications without interaction, with three, four or six criteria, Proposals [7] and [8] move from Class 2 to Class 1 and Proposal [2] moves from Class 3 to Class 2. With five criteria, Proposal [8] moves from Class 2 to Class 1, while proposals [1], [2] and [7] move from Class 3 to Class 2. shows the number of times each alternative is allocated in each class, considering all combinations of number of criteria and composition rules.

5. Conclusion

This study proposes the use of a multi-criteria classification model in the process of evaluating proposals for rewarded collaboration, which could result in significant progress in the fight against large-scale illicit operations.

The model considers, in parallel, criteria representative of the collaborators' objective of minimizing potential penalties and criteria of broader interest. New approaches for modeling the relationships between criteria in practical situations are suggested. Consideration is given to the possibility of agreements between collaborators to submit joint proposals.

Incorporating an objective evaluation model makes rewarded collaboration more secure and appealing. By reducing discretion in the evaluation of the proposals, the presence of an objective instrument in the process can considerably increase the system's attractiveness. And agents in operational positions within the criminal structure may feel more secure in moving away from the criminal leadership and offering valuable collaboration to society in exchange for reduced sentences.

The approach developed using CPP-Tri to classify each proposal individually into predefined classes entails the disclosure of criteria and performance profiles according to each criterion in advance. This is in the interest of transparency and dependability.

By taking into account the interaction between the criteria and by internally determining the importance of the criteria as a function of the own assessments of the proposal's value, this methodology also expands the possibility of applying a greater number of criteria and of applying criteria for which anticipating preferences is impossible or undesirable.

Reproducibility Report

Download MS Word (29.6 KB)Online_Supplemental__File.pdf

Download PDF (33.1 KB)Data availability statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and in its supplementary materials.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Annibal Parracho Sant’Anna

Annibal Parracho Sant'Anna, PhD in Statistics from the University of California, Berkeley (1977), MSc in Mathematics from IMPA/CNPq (1970), and BA in Mathematics and Economics from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (1966 and 1970, respectively). Since 2014, he has been a Professor in the Doctoral Program in Sustainable Management Systems at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF). Former Director of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro's Institute of Mathematics (1980-1982,1986-1990) and Statistics Laboratory (1983-1986), as well as Coordinator of the Graduate Programs in Production Engineering at COPPE/UFRJ (1991-1992) and at the School of Engineering of UFF (2001-2008). Former President of the Brazilian Society for Operations Research (2007-2010). Benchmarking, Energy Policy, Information Sciences, International Statistical Review, Soccer and Society, and Social Indicators Research are among the journals in which he has published articles. He is presently the Editor-in-Chief of Pesquisa Operacional.

Luiz Octávio Gavião

Luiz Octávio Gavião, DSc (2017) and MSc (2014) in Production Engineering from the Fluminense Federal University, Brazil. MSc in Military studies from the United States Marine Corps University (2003). He graduated in Naval Sciences, major in Electronics, at the Brazilian Naval Academy (1990). He is active in the Postgraduate Program on International Security and Defense at the Brazilian War College. His research has been published in periodicals like International Journal of Business and Society, International Journal of Production Economics, Journal of Environmental Management and Journal of Sports Sciences.

Tiago Lezan Sant’Anna

Tiago Lezan Sant'Anna, DSc (2022) in Law by from State University of Rio de Janeiro. MSc in Law from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (2011). Graduated from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro in 2005 with a degree in Journalism and from the State University of Rio de Janeiro in 2006 with a degree in Law in 2006. He is a lawyer at the National Bank for Economic and Social Development in Brazil (BNDES). He has published in journals such as Revista do BNDES, Revista Dialética de Direito Processual and Revista Compliance Rio.

References

- Anzoom, R., Nagi, R. and Vogiatzis, C. (2022) A review of research in illicit supply-chain networks and new directions to thwart them. IISE Transactions, 54(2), 134–158.

- Basilio, M.P., Pereira, V. and Costa, H.G. (2019) Classifying the integrated public safety areas (IPSAs): A multi-criteria based approach. Journal of Modelling in Management, 14(1), 106–133.

- Baycik, N.O., Sharkey, T.C. and Rainwater, C.E. (2018) Interdicting layered physical and information flow networks. IISE Transactions, 50(4), 316–331.

- Biehl, J., Prates, L.E.A. and Amon, J.J. (2021) Supreme Court v. necropolitics: The chaotic judicialization of COVID-19 in Brazil. Health and Human Rights Journal, 23(1), 151–163.

- Choquet, G. (1953) Theory of capacities. Annales de l'Institut Fourier, 5, 131–295.

- Fishburn, P.C. (1970) Utility Theory for Decision Making, Wiley, New York.

- Fishlow, A. (2020) Lava Jato in perspective. Corruption and the Lava Jato Scandal in Latin America, Routledge, New York, pp. 17–34.

- Gavião, L.O., Sant’Anna, A.P., Lima, G.B.A. and Garcia, P.A. de A. (2018) CPP: Composition of Probabilistic Preferences. R package version 0.1.0. Available at https:cran.rproject.org/web/packages/CPP/index.html (accessed 24 February 2023).

- Gonzalez-Ocantos, E. and Hidalgo, V.B. (2019) Lava Jato beyond borders. Taiwan Journal of Democracy, 15(1), 63–89.

- Grabisch, M., Kojadinovic, I. and Meyer, P. (2008) A review of methods for capacity identification in Choquet integral based multi-attribute utility theory: Applications of the Kappalab R package. European Journal of Operational Research, 186(2), 766–785.

- Inotai, A., Nguyen, H.T., Hidayat, B., Nurgozhin, T., Kiet, P.H.T., Campbell, J.D., Bertalan Németh, B., Maniadakis, N., Brixner, D., Wijaya, K. and Kaló, Z. (2018) Guidance toward the implementation of multicriteria decision analysis framework in developing countries. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 18(6), 585–592.

- Kanner, S.L., Rosen, D., Zohar, Y. and Alberstein, M. (2019) Managerial judicial conflict resolution (JCR) of plea bargaining: Shadows of law and conflict resolution. New Criminal Law Review, 22(4), 494–541.

- Konrad, R.A., Trapp, A.C., Palmbach, T.M. and Blom, J.S. (2017) Overcoming human trafficking via operations research and analytics: Opportunities for methods, models, and applications. European Journal of Operational Research, 259(2), 733–745.

- Kovač, M. and Bezerra, M.N. (2020) Eroded rule of law, endemic violence and social injustice in Brazil. LeXonomica, 12(2), 211–242.

- Leung, S. (2011) A comparison of psychometric properties and normality in 4-, 5-, 6-, and 11-point Likert scales. Journal of Social Service Research, 37(4), 412–421.

- Limongi, F. (2021) From birth to agony: The political life of operation car wash (operação lava jato). University of Toronto Law Journal, 71(supplement 1), 151–173.

- Luz, R.D. and Spagnolo, G. (2017) Leniency, collusion, corruption, and whistleblowing. Journal of Competition Law & Economics, 13(4), 729–766.

- Meszaros, G. (2020) Caught in an authoritarian trap of its own making? Brazil’s ‘Lava jato’anti-corruption investigation and the politics of prosecutorial overreach. Journal of Law and Society, 47, S54–S73.

- Nishijima, M., Sarti, F.M. and Cati, R.C. (2019) The underlying causes of Brazilian corruption. In Corruption in Latin America, Springer, Cham, pp. 29–56.

- Pardieck, A.M., Edkins, V.A. and Dervan, L.E. (2020) Bargained justice: The rise of false testimony for false pleas. Fordham International Law Journal, 44(2), 469–528.

- R-Core-Team (2018) R: A language and environment for statistical computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna-Austria. Available at http://www.R-project.org (accessed 31 October 2022).

- Raiffa, H. (1982) The Art and Science of Negotiation. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Roza, D.A., Aguiar, G.T., Lima, E.P., Costa, S.E.G. and Adamczuk, G.O. (2020) Decision model for selecting advanced technologies for municipal solid waste management. International Business, Trade and Institutional Sustainability, Springer, Cham, pp. 201–220.

- Sant’Anna, A.P. (2023) Rcode CPPTRI reward, Zenodo,

- Sant’Anna, A.P., Costa, H.G. and Pereira, V. (2015) CPP-TRI: A sorting method based on the probabilistic composition of preferences. International Journal of Information and Decision Sciences, 7(3), 193–212.

- Sant’Anna, A.P., Gavião, L.O. and Sant’Anna, T.L. (2020) Abordagem multicritério para a delação premiada. In: Annals of LII SBPO. Available at https://proceedings.science/sbpo-2020/papers/abordagem-multicriterio-para-a-delacao-premiada?lang=pt-br (accessed 31 October 2022).

- Sant’Anna, A.P. and Sant’Anna, J.L. (2019) A principle of preference concentration applied to the unsupervised evaluation of the importance of multiple criteria. Pesquisa Operacional, 39(2), 317–338.

- Shapley, L. (1953) A value for n-person games. Contributions to the Theory of Games, Vol. II. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, pp. 307–317.

- Schneider, A.K. and Alkon, C. (2019) Bargaining in the dark: The need for transparency and data in plea bargaining. New Criminal Law Review, 22(4), 434–493.

- Straffin, P. (1980) The prisoner’s dilemma. The UMAP Journal, 1, 101–103.

- Turner, J.I. (2020) Transparency in plea bargaining. Notre Dame Law Review, 96(3), 973–1023.