Abstract

A 57-year-old woman was found at home in quiet coma secondary to a deliberate insulin glargine injection. Due to the persistent hypoglycemia, she was referred to the ICU where she remained hypoglycemic for seven days. The patient presented recurrent episodes of hypoglycemia, even after day 7 and she received a total of 587 g of dextrose. Few data are available concerning the management of intoxication by long-lasting insulin. Our case illustrates the critical importance of admitting such patients in ICU for both close monitoring of blood sugar and dextrose administration. We discuss the discrepancy between the in vitro half-life of the insulin and the actual half-life with a “reservoir effect”. Eventually, we compare our case with the case-studies in the literature and summarize the review of those published cases.

Case

We report the case of a deliberate self-poisoning with a very high dose of long acting insulin glargine in a 57-year-old woman.

The patient was found at home in a quiet GCS 6 coma, with bilateral myosis and hypoglycemia measured at 0.18 g/L (18 mg/dL, 1 mmol/L). Next to her were found seven pens of long acting insulin glargine (Lantus®), containing 300 IU each and all empty. The highest dose possibly injected was 2100 IU. Initial care consisted of hypoglycemia correction by intravenous (IV) injection of 80 mL of 30% glucose fluid corresponding to 24 g of glucose and oxygen therapy. Patient regained consciousness once hypoglycemia had been corrected and presented no organ failure. The longest possible time between injection of insulin and primary care was 7 h.

The patient was transferred to the ICU where the other causes of coma were eliminated: no sign of stroke, no sign of infection, no metabolic disorders (except the hypoglycemia), no other toxins detected (alcohol, tricyclic, acetaminophen, salicylate, benzodiazepine were all negative). There were no oral hypoglycemic agents found in blood nor urine.

The patient had a past medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with basal bolus insulin scheme. Her diabetes was complicated with a chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 5 requiring dialysis every two days. No other additional complications of diabetes were known. She had a left nephrectomy for a benign tumor and gastric by-pass surgery for obesity. She also had a psychiatric history with major depressive disorder and one suicide attempt.

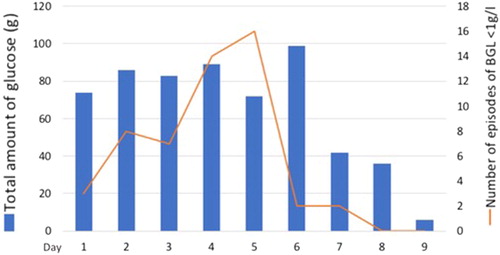

In the ICU the patient had recurrent hypoglycemia with confusion requiring continuous infusion of 10% glucose fluid for 8 days and with G30% bolus when blood glucose level (BGL) was under 1g/L (100 mg/dL, 5.5 mmol/L). To restrict the IV fluid intake, enteral feeding using Nutrison Iso® (1 kcal/mL), was started on day 2 until day 6. Glucose was administered IV using 30% and 10% glucose fluid and the patient received a total amount of 587 g of glucose ().

Figure 1. Evolution of the blood glucose level and glucose infused over the days in ICU. BGL: blood glucose level.

She had no neurologic sequelae due to the repeated hypoglycemia. After two days with BGL >1g/L (100 mg/dL, 5.5 mmol/L) without glucose supplementation, the patient was discharged to the psychiatric ward for further care. A recent clinical follow-up confirmed that after more than two months, the patient had no neurologic sequelae due to the episode.

Discussion

Different studies [Citation1,Citation2] described the treatment of intentional insulin overdoses with intravenous glucose. Both studies underlined that insulin overdoses often require prolonged aggressive IV glucose infusion and serial monitoring of BGL. Moreover, they found out that these patients may become hypoglycemic much longer than expected based on the duration of therapeutic action of the insulin preparations involved.

The pharmacokinetics of the glargine insulin involved in our case has been studied in healthy volunteers. At both therapeutic (0.4 IU/kg) and high (0.8 IU/kg) doses, the insulin glargine was metabolized in 24 h [Citation3]. No data are available to predict the pharmacokinetics of higher doses than 0.8 IU/kg. Megarbane et al. [Citation4] published in 2007 a prospective study involving regular and NPH insulin. The application of their results to the dose of insulin would predict a duration of glucose infusion of 110 h. But the fact that the insulin was different from the one involved in our case precludes extrapolation, as illustrated by the prolonged duration of hypoglycemia in our case. Among the 25 patients included in the study of Megarbane et al. [Citation4], 13 patients involved NPH which is long acting insulin. The median of the total duration of glucose infusion was 32 h (range 12–68) for a median total amount of infused glucose of 301 g (extreme values 184–1056). The authors found that the optimal glucose infusion was difficult to predict because of the potentially delayed and erratic absorption of the injected insulin, leading to varying kinetics (especially when different types of insulin were injected).

Lu et al. [Citation5] described a case of insulin glargine overdose in 2011. The patient had self-administered 2700 units of insulin glargine in an attempted suicide. Despite glucose infusion and liberal oral intake, the patient presented recurrent hypoglycemic episodes during 96 h.

We performed a review of similar cases and reported these data in .

Table 1. Review of similar cases.

Several factors may have altered insulin kinetics, resulting in prolonged elimination and consequently prolonged duration of action in our case: (i) injection of a large volume of insulin led to the formation of a cistern and reduced the absorption (due to the mass effect on the tissues at the injection site), (ii) there is a reservoir effect as can be seen in lipodystrophies secondary to repeated injections of insulin, and (iii) impaired kidney and hepatic function may also alter insulin clearance [Citation4]. It is likely that the reservoir effect and the terminal kidney failure had played a major role in modifying the kinetics of insulin and could have explained the particularly long time of hypoglycemia.

Considering the prognosis, it seems that the best predictive factors are the interval between insulin injection and initiation of therapy (cut-off at 10 h) and the duration of hypoglycemia are relevant prognostic factors [Citation2,Citation20].

Our case highlights the possibly long hypoglycemia after injection of a large quantity of long-lasting insulin. It underlines the critical importance of tight monitoring of the BGL. The clearance of the insulin can widely vary. It depends on several factors like kidney failure or depot effect. The duration of the hypoglycemia and the duration of glucose infusion are not easily predictable.

To conclude, it seems reasonable to recommend that such cases should be monitored in ICU until the BGL remains >1g/L (100 mg/dL, 5.5 mmol/L) without glucose infusion.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Stapczynski JS, Haskell RJ. Duration of hypoglycemia and need for intravenous glucose following intentional overdoses of insulin. Ann Emerg Med. 1984;13:505–511.

- Arem R, Zoghbi W. Insulin overdose in eight patients: insulin pharmacokinetics and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1985;64:323–332.

- Lucidi P, Porcellati F, Candeloro P, et al. Glargine metabolism over 24 h following its subcutaneous injection in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a dose–response study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24:709–716.

- Mégarbane B, Deye N, Bloch V, et al. Intentional overdose with insulin: prognostic factors and toxicokinetic/toxicodynamic profiles. Crit Care. 2007;11:R115.

- Lu M, Inboriboon PC. Lantus Insulin Overdose: a Case Report. J Emerg Med. 2011;41:374–377.

- Mork TA, Killeen CT, Patel NK, et al. Massive insulin overdose managed by monitoring daily insulin levels. Am J Ther. 2011;18:e162–e166.

- Kumar A, Hayes CE, Iwashyna SJ, et al. Management of intentional overdose of insulin glargine. Endocrinol Nutr. 2012;59:570–572.

- Canning J, O’Connor A, Truitt C. Prolonged, refractory hypoglycemia after insulin glargine overdose treated with continuous D50 infusion and confirmed with insulin and C-peptide levels. North Am Congr Clin Toxicol. 2010;48:657.

- Brvar M, Mozina M, Bunc M. Poisoning with insulin glargine. Clin Toxicol (Phila).. 2005;43:219–220.

- Kuhn B, Cantrell L. Unintentional overdose of insulin glargine. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65:508.

- Kim CCK, Rosano TG, Chambers EE, et al. Insulin glargine and insulin aspart overdose with pharmacokinetic analysis. AACE Clin Case Rep. 2016;2:e122–e128.

- Fromont I, Benhaim D, Ottomani A, et al. Prolonged glucose requirements after intentional glargine and aspart overdose. Diabetes Metab. 2007;33:390–392.

- Tofade TS, Liles EA. Intentional overdose with insulin glargine and insulin aspart. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24:1412–1418.

- Karatas F, Sahin S, Karatas H, et al. The highest (3600 IU) reported overdose of insulin glargine ever and management. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2015;19:750.

- Fuller ET, Miller MA, Kaylor DW, et al. Lantus overdose: case presentation and management options. J Emerg Med.. 2009;36:26–29.

- Doğan FS, Onur OE, Altınok AD, et al. Insulin glargine overdose. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2012;3:333.

- Groth CM, Banzon ER. Octreotide for the treatment of hypoglycemia after insulin glargine overdose. J Emerg Med. 2013;45:194–198.

- Ashawesh K, Padinjakara RNK, Murthy NP, et al. Intentional overdose with insulin glargine. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66:534.

- Thornton S, Gutovitz S. Intravenous overdose of insulin glargine without prolonged hypoglycemic effects. J Emerg Med. 2012;43:435–437.

- Moore DF, Wood DF, Volans GN. Features, prevention and management of acute overdose due to antidiabetic drugs. Drug Saf. 1993;9:218–229.