Abstract

Acetaminophen (paracetamol) remains the leading pharmaceutical agent in overdoses in North America. The three-bag Prescott protocol for intravenous (IV) acetylcysteine is complex and prone to errors. It has frequent adverse reactions, particularly non-allergic anaphylactoid reactions (NAARs). Over 15 years ago, we adopted a simplified, one-bag protocol using a standard concentration to reduce errors. We report the adverse reactions with this protocol. We used hospital pharmacy records to retrospectively identify patients who received IV acetylcysteine between 12 January 2005 and 20 June 2016. We excluded patients without acetaminophen overdose or with any part of their IV acetylcysteine at an outside hospital. We searched pharmacy records for diphenhydramine or any antiemetic after commencing IV acetylcysteine. We reviewed progress notes for descriptions of nausea, dyspnea, itching/pruritus, or rash. Out of 252 patients receiving IV acetylcysteine, 202 met our inclusion criteria. Thirty-three patients had at least one adverse reaction including nausea in 28 patients and any symptom of NAAR in 8 patients. Twenty-eight patients received an antiemetic. Eleven patients received diphenhydramine (nine for NAAR and two with prochlorperazine). Nausea was the most common adverse reaction. The rate of non-allergic anaphylactoid reactions with the one-bag protocol was 4%.

Introduction

Acetylcysteine is the antidote for acetaminophen (APAP) poisoning, the most common pharmaceutical poisoning in the US and Canada [Citation1, Citation2]. The Prescott protocol, the standard treatment for four decades, consists of a three-bag regimen with each bag having unique, patient-specific concentrations and different infusion rates [Citation3, Citation4].

Adverse reactions, typically mild non-allergic anaphylactoid reactions (NAARs), are common with the Prescott protocol and tend to occur during or soon after infusion of the first and most concentrated bag [Citation5–7]. Estimates of NAAR frequency vary widely. A 2016 review article found published frequencies of NAARs ranging from 9% to 69% [Citation6]. The Canadian Acetaminophen Overdose Study (CAOS) group has the largest database of acetaminophen overdoses comprising 11,987 hospital admissions in 34 hospitals in eight Canadian cities from 1980 to 2005 [Citation7]. The CAOS group studied 6455 patients receiving the 21-hour Prescott acetylcysteine protocol and found that NAARs occurred in 8.2% of patients [Citation7]. Most of these were cutaneous reactions treated with antihistamines.

Our hospital has used a simpler, standardized approach for over 15 years [Citation8–11]. This method uses a standard concentration of 30 mg/mL (30 g/L) for all patients. Our programmable infusion pumps (BD-Alaris®; Becton, Dickinson, and Co., Franklin Lakes NJ) are set to this standard concentration. The loading dose remains 150 mg/kg over one hour followed by a 12.5 mg/kg/h maintenance infusion. We continue the infusion until laboratory data demonstrate no detectable APAP, international normalized ratio (INR) < 2, and transaminases returning to normal with decline of >50% from the highest observed AST activity. The aim of this study was to describe the rates of adverse reactions associated with our one-bag regimen over a twelve-year interval.

Methods

We conducted a single-center, retrospective cohort study with adherence to the RECORD guidelines [Citation12]. We reviewed all charts of adult (≥18 years of age) patients presenting with a potentially toxic APAP ingestion treated with IV acetylcysteine from 12 January 2005 through 20 June 2016 at the Emergency Department (ED) of Barnes-Jewish Hospital in Saint Louis. Barnes-Jewish Hospital is a university-affiliated, urban, adult teaching hospital with on-site medical toxicology consultation service. The ED comprises 80 beds with over 90,000 visits per year. Patients received acetylcysteine at the discretion of the treating ED physician or the toxicology service.

We used pharmacy records to identify patients receiving acetylcysteine in the given time period in the ED using the Allscripts® electronic medical record system (Allscripts Healthcare Solutions, Chicago, IL). We excluded patients receiving acetylcysteine for reasons other than acetaminophen ingestions, those transferred from another hospital with acetylcysteine treatment in progress, and patients ≤17 years of age, although we do use a similar approach at the affiliated children’s hospital. We developed a standardized data abstraction form and pilot tested it prior to beginning the study. We reviewed pharmacy records, nursing notes, and progress notes and extracted data for adverse reactions, including nausea, NAARs and anaphylaxis. We defined NAARs as reactions suggesting histamine release including respiratory difficulty, shock, pruritus, and/or urticaria or any reactions treated with diphenhydramine after acetylcysteine administration commenced. Our primary outcome was the total proportion of patients with any adverse reactions (including nausea and NAARs). Two investigators received training in abstracting and recording data but were aware of the purpose of the study. The Washington University School of Medicine Human Studies Committee approved the study with exemption from informed consent.

Results

Patient characteristics

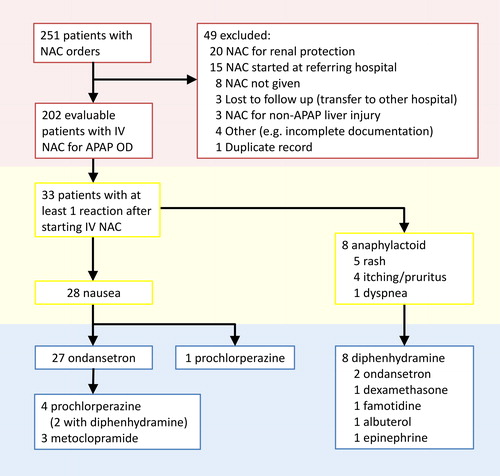

We identified 251 patients from 12 January 2005 to 20 June 2016 who received IV-acetylcysteine. We excluded 49 patients, mostly due to the patients receiving acetylcysteine at an outside hospital or due to receiving acetylcysteine for reasons other than APAP intoxication (). This left 202 patients in the final sample. The 202 patients (73 M, 129 F) meeting inclusion criteria had a mean age of 36.9 years (range 18–90) and a mean body weight of 73.6 kg (standard deviation 18.9 kg, range 36–136 kg).

Patient outcomes

Of the 202 patients, 33 (16.3%) experienced at least one adverse reaction after starting acetylcysteine (). Nausea was the most frequently reported reaction with this symptom recorded in 28 patients (13.9%). Twenty-five patients with nausea received ondansetron, five received prochlorperazine (four as rescue after ondansetron), and three received metoclopramide (all as rescue after ondansetron). Two patients received ondansetron with recorded symptoms of NAAR without recorded nausea.

Table 1. Frequencies of adverse reactions (n = 202).

Excluding nausea, 8 patients (4.0%) experienced a total of ten recorded symptoms comprising rash (five, 2.5%), itching/pruritus (four, 2.0%) , and dyspnea (one, 0.5%). Eleven patients (5.4% received diphenhydramine. Of these eleven, eight (4.0%) had at least one symptom of NAAR, and two (1.0%) had nausea only (diphenhydramine given with prochlorperazine). One patient (0.5%) received epinephrine.

One patient who reported pruritus also reported rash and shortness of breath after starting IV acetylcysteine empirically before the APAP concentration was available because he presented to the ED 16 h after ingestion. He received diphenhydramine 50 mg orally, epinephrine 0.3 mg by intramuscular injection, and prednisone 20 mg orally with cessation of IV acetylcysteine. His symptoms completely resolved. His initial [APAP] then resulted as 36.9 μg/mL. Acetaminophen was undetectable on repeat testing. He received no further acetylcysteine and had normal transaminases.

Five patients had acetaminophen concentrations that were less than 10 μg/mL on presentation to the ED. They received IV acetylcysteine based upon the ingestion history or abnormal transaminases. All five had reactions including NAAR in four and nausea in four (three had both NAAR and nausea).

Eight patients (4.0%) died of acute liver failure in the hospital. All eight presented more than two days after overdose with evidence of hepatic injury (elevated INR, AST, and ALT) on admission. None of these eight had nausea or NAAR. No death was attributable to acetylcysteine treatment.

Discussion

The complexity of the three-bag regimen is a major cause of medication errors [Citation11, Citation13–16]. Errors may occur in as many as one-third of IV acetylcysteine administrations with the three-bag regimen [Citation13]. In 2001, Ferner et al. measured the acetylcysteine concentrations in bags prepared for APAP poisoned patients in the UK and found the concentrations to be within 10% of the intended dose in only 37% of the bags [Citation14]. In 2017, a similar study by Bailey et al. determined that the dose accuracy (within 10%) had improved to only 50% of the infusion bags [Citation15]. The same study group found that two-thirds of patients receiving the three-bag protocol had at least one delay of at least 1 h with a median delay of 90 min [Citation16]. Most recently, Awad et al. found administration errors in more than half of their patients receiving IV acetylcysteine [Citation17].

Though IV acetylcysteine is generally very safe with only mild adverse effects, dosing errors resulting in much higher doses produce serious complications including cerebral edema, seizures, hemolytic uremic syndrome, and death [Citation18–21]. More common adverse reactions may include nausea, vomiting, and NAARs within the first two hours of IV acetylcysteine administration [Citation6, Citation7].

Different two-bag regimens seem to show reduced dosing errors and adverse reactions when compared to the three-bag protocol [Citation22–26]. The Australian and Danish studies demonstrate rates of NAAR of about 4% with the two-bag regimens, which is comparable to the 4% rate seen in this study [Citation23–26]. However, the Australian two-bag protocol and the UK SNAP two-bag protocol both retain most of the complexity of the Prescott protocol with patient-specific concentrations in each of the two bags and opportunity for delay between administration of the first and second bags.

Our results corroborate those of Kao et al. who observed an adverse reaction rate of 3.7% (7 of 187 patients receiving one-bag, standard concentration acetylcysteine [Citation27]. Six of these seven reactions were minor cutaneous reactions. The seventh reaction listed was junctional bradycardia and apnea leading to ventricular fibrillation. The authors classified this event as not clearly attributable to acetylcysteine. All ten deaths in their cohort occurred in patients who presented late to care with fulminant hepatic failure.

For over 15 years, our hospital has used the same simplified, one-bag regimen described by Kao et al. in 2003 [Citation27]. We use a uniform concentration of 30 mg/mL prepared by diluting 30 g of acetylcysteine into 1 L of D5W (or 15 g of acetylcysteine in 500 mL of D5W for children and patients weighing less than 40 kg) [Citation9–11]. From this bag, we administer a 150 mg/kg loading infusion over an hour followed by a 12.5 mg/kg/h maintenance infusion. We continue the infusion for 20 h or until lab data meet criteria for stopping acetylcysteine. The majority of patients receive the entire course of treatment from a single bag. Patients weighing more than 75 kg or needing acetylcysteine beyond the first 21 h may require a second bag.

The simplicity of this one-bag regimen compared to the standard three-bag and newer two-bag regimens promotes safety by decreasing the number of interventions required to administer the therapy. The one-bag approach delivers a total dose of 400 mg/kg over 21 h with a single, standardized compounding step. Additionally, the higher total dose of 400 mg/kg affords additional protection for patients with larger overdoses resulting in concentrations above the 300 μg/mL line of the Rumack-Matthew nomogram [Citation28]. Johnson et al. studied administration errors in an earlier and smaller cohort of our acetaminophen overdose patients [Citation9]. When using the same definitions for errors as used by Hayes et al., the error rate was lower than with the three-bag method [Citation9, Citation13].

Five patients with adverse reactions associated with acetylcysteine infusions with undetectable APAP concentrations (<10 μg/mL). At least two received acetylcysteine empirically based upon the ingestion history, and three received it for abnormal transaminase activities. Low APAP concentrations increase the likelihood of an adverse reaction with acetylcysteine [Citation7, Citation29–33]. These cases illustrate the value of determining the APAP concentration before ordering IV acetylcysteine in patients who present early after APAP overdose.

The current study provides further evidence that the one-bag, single-concentration approach is safe and well-tolerated by patients. Retrospective studies may underestimate the frequency of adverse reactions, especially minor or transient reactions. However, we found the frequency of NAARs to be lower than with the Prescott three-bag and comparable to the frequency with of two-bag regimens [Citation6, Citation7, Citation23–26]. None of the eight deaths in our sample were attributable to acetylcysteine therapy. In our study, patients most commonly reported nausea, which may be attributed to the effects of acetaminophen toxicity itself rather than IV acetylcysteine therapy.

The limitations of this study are similar to those in related studies [Citation23–26]. This study occurred at a single institution with no simultaneous comparison to the three-bag regimen. However, now multiple hospitals in our area, in other regions of the country, and in Canada are using the one-bag approach [Citation11].

Data abstractors were aware of the study purpose, but the principal data sources were pharmacy records of anti-emetic or anti-histamine administration. Our study methods, case definitions, and comparison to historical controls are similar to those in studies of the two-bag protocols [Citation22–26]. However, the simplicity of the one-bag regimen may be especially useful in settings with low volume of acetaminophen intoxication and nursing staff that is unfamiliar with the more complicated three-bag approach. Finally, this study did not account for co-ingestants which might have contributed to the adverse reactions experienced during acetylcysteine therapy.

Conclusion

The one-bag method with a standard concentration of 30 mg/mL results in fewer adverse reactions when compared to published data for the three-bag Prescott protocol. The rate of adverse reactions is similar to rates seen with the two-bag methods. The simplicity and uniformity of a single-bag regimen promotes safety by minimizing opportunity for error.

Acknowledgement

This work was presented as abstract poster at 2017 North American Congress of Clinical Toxicology, Vancouver, British Columbia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2018 Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers' National Poison Data System (NPDS): 36th annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57(12):1220–1413.

- Myers RP, Li B, Fong A, et al. Hospitalizations for acetaminophen overdose: a Canadian population-based study from 1995 to 2004. BMC Public Health 2007;7(1):143.

- Prescott LF, Illingworth RN, Critchley JA, et al. Intravenous N-acetylcystine: the treatment of choice for paracetamol poisoning. Br Med J. 1979; 2(6198):1097–1100.

- Acetadote® package insert. Nashville (TN): Cumberland Pharmaceuticals Inc. [accessed 2019 31 May]. Available from: http://acetadote.com/acetadote-prescribing-information-11-2016.pdf.

- Bonfiglio MF, Traeger SM, Hulisz DT, et al. Anaphylactoid reaction to intravenous acetylcysteine associated with electrocardiographic abnormalities. Ann Pharmacother. 1992;26(1):22–25. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/106002809202600105

- Sandilands EA, Morrison EE, Bateman DN. Adverse reactions to intravenous acetylcysteine in paracetamol poisoning. Adv Drug React Bull. 2016; 297:1147–1150.

- Yarema M, Chopra J, Sivilotti MLA, et al. Anaphylactoid reactions to intravenous N-acetylcysteine during treatment for acetaminophen poisoning. J Med Toxicol. 2018;14(2):120–127.

- Mullins ME, Dribben WH, Halcomb SE, et al. Comment: frequency of medication errors with intravenous acetylcysteine for acetaminophen overdose. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(12):1914–1915.

- Johnson MT, McCammon CA, Mullins ME, et al. Evaluation of a simplified N-acetylcysteine dosing regimen for the treatment of acetaminophen toxicity. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(6):713–720.

- Schwarz ES, Mullins ME, Liss DB. When two is not better than one. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(10):2310–2311.

- Mullins ME, Yarema MC, Sivilotti MLA, et al. Comment on “Transition to two-bag intravenous acetylcysteine for acetaminophen overdose". Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2020;58(5):433–435.

- Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al., RECORD Working Committee. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) Statement. PLoS Med. 2015; 12(10):e1001885.

- Hayes BD, Klein-Schwartz W, Doyon S. Frequency of medication errors with intravenous acetylcysteine for acetaminophen overdose. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(6):766–770.

- Ferner RE, Langford NJ, Anton C, et al. Random and systematic medication errors in routine clinical practice: a multicentre study of infusions, using acetylcysteine as an example. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;52(5):573–577.

- Bailey GP, Wood DM, Archer JR, et al. An assessment of the variation in the concentration of acetylcysteine in infusions for the treatment of paracetamol overdose. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(2):393–399.

- Bailey GP, Najafi J, Elamin MEMO, et al. Delays during the administration of acetylcysteine for the treatment of paracetamol overdose. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82(5):1358–1363.

- Awad NI, Geib AJ, Roy A, et al. Protocol deviations in intravenous acetylcysteine therapy for acetaminophen toxicity. Am J Emerg Med. 2020. (online ahead of print). DOI:10.1016/j.ajem.2019.158405

- Bailey B, Blais R, Letarte A. Status epilepticus after a massive intravenous N-acetylcysteine overdose leading to intracranial hypertension and death. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44(4):401–406.

- Heard K, Schaeffer TH. Massive acetylcysteine overdose associated with cerebral edema and seizures. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49(5):423–425.

- Mullins ME, Vitkovitsky IV. Hemolysis and hemolytic uremic syndrome following five-fold N-acetylcysteine overdose. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49(8):755–759.

- Personne M. A 10-fold dose of N-acetylcysteine with fatal consequences. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2018;56(6):446–446.

- Thanacoody HKR, Gray A, Dear JW, et al. Scottish and Newcastle antiemetic pre-treatment for paracetamol poisoning study (SNAP). BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013; 14(20):20–12.

- Chiew AL, Isbister GK, Duffull SB, et al. Evidence for the changing regimens of acetylcysteine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;81(3):471–481.

- Wong A, Graudins A. Simplification of the standard three-bag intravenous acetylcysteine regimen for paracetamol poisoning results in a lower incidence of adverse drug reactions. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2016;54(2):115–119.

- McNulty R, Lim JME, Chandru P, et al. Fewer adverse effects with a modified two-bag acetylcysteine protocol in paracetamol overdose. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2018;56(7):618–621.

- Schmidt LE, Rasmussen DN, Petersen TS, et al. Fewer adverse effects associated with a modified two-bag intravenous acetylcysteine protocol compared to traditional three-bag regimen in paracetamol overdose. Clin Toxicol. 2018;56(11):1128–1134.

- Kao LW, Kirk MA, Furbee RB, et al. What is the rate of adverse events after oral N-acetylcysteine administered by the intravenous route to patients with suspected acetaminophen poisoning?. Ann Emerg Med. 2003; 42:742–750.

- Hendrickson RG. What is the most appropriate dose of N-acetylcysteine after massive acetaminophen overdose?. Clin Toxicol. 2019;57(8):686-691. DOI:10.1080/15563650.2019.1579914

- Dawson AH, Henry DA, McEwen J. Adverse reactions to N-acetylcysteine during treatment for paracetamol poisoning. Med J Aust. 1989;150(6):329–331.

- Lynch RM, Robertson R. Anaphylactoid reactions to intravenous N-acetylcysteine: a prospective case controlled study. Accid Emerg Nurs. 2004;12(1):10–15.

- Waring WS, Stephen AF, Robinson OD, et al. Lower incidence of anaphylactoid reactions to N-acetylcysteine in patients with high acetaminophen concentrations after overdose. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2008;46(6):496–500.

- Pakravan N, Waring WS, Sharma S, et al. Risk factors and mechanisms of anaphylactoid reactions to acetylcysteine in acetaminophen overdose. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2008;46(8):697–702.

- Schmidt LE. Identification of patients at risk of anaphylactoid reactions to N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of paracetamol overdose. Clin Toxicol. 2013;51(6):467–472.