Abstract

We present a case of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) linked to N-acetylcysteine (NAC) overdose during treatment for acetaminophen overdose. The patient presented to the emergency department following the ingestion of 455 mg/kg of acetaminophen and was administered a total of 46.2 g of NAC over 14 h in error, compared to the intended 19.8 g. She subsequently developed status epilepticus. After seizure control, brain imaging by CT and MRI showed PRES. Continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) was started to eliminate NAC and acetaminophen. The patient eventually recovered neurologically with improved transaminases and was free of further seizures.

Introduction

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is a highly effective antidote for acute acetaminophen poisoning. Although widely regarded as safe, dosing errors do occur and large overdoses of NAC have harmed patients [Citation1–3], including several reports of direct central nervous system (CNS) toxicity [Citation4,Citation5].

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) is a condition characterized by reversible, acute cortical and subcortical vasogenic edema, mainly in the parieto-occipital regions [Citation6–8]. Afflicted patients classically present with encephalopathy, seizures, and visual disturbances [Citation9]. We present a case, in accordance with the CARE Guidelines [Citation10], of PRES associated with acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in the context of a NAC dosing error.

Case report

A 20-year-old woman (162 cm, 55 kg) with no past medical history presented to the emergency department 12 h following a reported intentional ingestion of 50 × 500 mg (455 mg/kg) acetaminophen tablets in less than an hour. On initial evaluation, the patient was asymptomatic with normal vital signs (heart rate 93 beats per minute, blood pressure 134/92, respiration 18 breaths/minute, temperature 36.3 °C), intact mental status, and an unremarkable physical exam. Her laboratory test results are summarized in .

Table 1. Laboratory results.

The regional Poison Centre uses a modified one-bag 3% IV NAC protocol, wherein a loading dose of 60 mg/kg/h of NAC (30 mg/mL) is given for 4 h, followed by a maintenance dose of 6 mg/kg/h, until stopping criteria are met. A higher maintenance dose of 12 mg/kg/h is used in high-risk patients [Citation11]. At 13.5 h post-ingestion, NAC was initiated at a continuous infusion of 60 mg/kg/h. Rather than transitioning to a maintenance dose as per Poison Centre protocol, the patient remained at 60 mg/kg/h continuously for 14 h (total 46.2 g of NAC administered over 14 h instead of intended 19.8 g). At 27 h post-ingestion, and 12 h into the 60 mg/kg/h IV NAC infusion, the patient suffered three self-terminating seizures without full recovery of consciousness. Her systolic blood pressure was documented to be 170–180 mmHg. During this time, the NAC administration error became apparent and prompted discontinuation.

The patient was intubated in the Intensive Care Unit. She was started on a propofol infusion (3 mg/kg/h) to abate her seizures as well as levetiracetam. Urine toxicology screen was negative for amphetamines, cocaine, opiates, cannabinoids, and barbiturates. Continuous electroencephalographic monitoring did not show epileptiform activity on or off propofol.

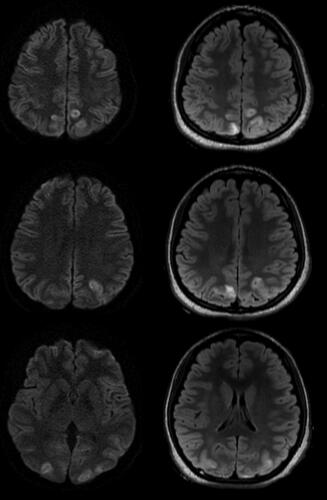

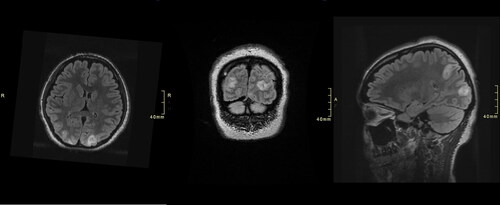

A computed tomographic (CT) head done 20 h post-admission showed mild effacement of cerebral sulci bilaterally, faint subcortical lucency in bilateral parasagittal, parieto-occipital regions, and no focal infarction, hemorrhage or mass lesion, in keeping with mild cerebral edema and possible PRES. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans obtained at 27 () and 70 h () post-admission demonstrated multifocal cortical and subcortical areas of T2/FLAIR hyperintensity within the bilateral medial parietal and occipital lobes with associated mass effect and diffusion restriction, suggestive of PRES.

Figure 1. Axial T2-weighted-fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (T2/FLAIR) MR (right column) and diffusion-weighted (left column) images demonstrated hyperintensity and diffusion restriction, respectively, within the bilateral medial parietal and occipital lobes at 27-h post-admission.

Figure 2. Axial (left), coronal (Middle), and sagittal (right) T2-weighted-fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (T2/FLAIR) MR images demonstrated hyperintensity within the bilateral medial parietal and occipital lobes at 70-h post-admission.

Continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) was started due to concern that seizures were related to NAC. Five doses of intravenous fomepizole (loading dose of 15 mg/kg, then 10 mg/kg over 30 min every 4 h during CRRT) were administered; it was stopped when serum acetaminophen level was undetectable. NAC was resumed (IV infusion 12 mg/kg/h) 14 h after it was held due to rising aminotransferases. CRRT was continued when NAC was restarted.

She did not have further seizures and was weaned off propofol and levetiracetam at 61 h post-admission and extubated after five days. A CT head obtained 165-h post-admission showed interval improvement in bilateral hypodensities noted on the initial CT head, with only minimal residual hypodensity in the left occipital lobe, demonstrating reversibility in keeping with PRES. She reported visual disturbances in the form of flashing lights with black spots, but an ocular examination by ophthalmology was normal. Ultimately, she had a full hepatic and neurological recovery by two weeks, and renal recovery in 4 weeks, following several weeks of dialysis support.

Discussion

PRES is an acute syndrome characterized by seizures, encephalopathy, visual changes, and radiographically by white matter vasogenic edema mainly involving the posterior occipital and parietal lobes [Citation6–8]. PRES has been associated with hypertension, pre-eclampsia, renal failure, liver disease, autoimmune conditions, immunosuppressants, and chemotherapeutic agents [Citation9,Citation12]. Although NAC has a wide therapeutic index, severe adverse outcomes and death have been reported following large iatrogenic NAC overdoses [Citation4,Citation5,Citation13]. There are at least 8 reported cases in the literature of iatrogenic NAC overdose leading to severe neurological outcomes [Citation14]. These cases involved NAC administration errors ranging from 4 to 16 fold dosing errors, leading to seizures, cerebral edema, brain herniation, hemolytic uremic syndrome and in some cases, death. The NAC dose received by our patient (46.2 g over 14 h, 840 mg/kg, a 2.3 fold error) was not as high as these previously reported cases. For our case, at the time of the neurological deterioration, her serum sodium levels were within normal range and liver enzymes as well as ammonia were only mildly elevated at this time, as it occurred prior to progression to more severe liver failure; however, serum osmolality was transiently elevated (). The 3% IV NAC admixture used for this patient is hyperosmolar [Citation15]. There are reports of PRES occurring in hyperosmolar states including hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome [Citation16], as well as in the context of hyperammonemia with hepatic encephalopathy, albeit at higher ammonia levels than documented for our patient [Citation17].

There are a few previous reports that have considered the relationship between acetaminophen, NAC, and the development of PRES. In the original case series of 15 patients with PRES published in 1996, one patient had acetaminophen-induced hepatorenal failure, although it was not described if they received NAC [Citation9]. Another case report described PRES presenting 11 days post acetaminophen ingestion (402 mg/kg) in a 21-year-old woman who received an appropriate dose of NAC (loading dose 200 mg/kg over 4 h and maintenance dose 150 mg/kg over 24 h) [Citation18]. In a case report of a 6-year-old girl with acute liver failure after sodium valproate toxicity treated with NAC, PRES developed after liver recovery but during NAC administration [Citation19]. The symptoms of PRES were similar to our patient including seizures and altered mental status. Interestingly, PRES resolved soon after discontinuation of NAC. Hershkovitz et al. describe a case of a 2.5 year old girl treated with an appropriate NAC dose (150 mg/kg loading dose over 30 min, 50 mg/kg over 4 h, and 100 mg/kg over 16 h) for presumed acetaminophen overdose [Citation20]. NAC was discontinued after 16 h total due to irritability that progressed to status epilepticus and reversible cortical blindness. Ultimately, acetaminophen levels were identified as being in non-toxic range, suggesting that the neurological symptoms were related to NAC and not acetaminophen, however, imaging was not reported.

Although we hypothesized that NAC may have played a role in the pathogenesis of PRES, the underlying mechanism is not clear. The pathophysiology of PRES is theorized to be related to increased vascular permeability and vasodilation through various mechanisms, either through disruption of cerebral autoregulation leading to vascular injury, blood-brain barrier compromise, and vasogenic edema, or via endothelial dysfunction from endogenous or exogenous toxins in diverse conditions [Citation12]. The role that NAC could play in this dysregulation would be purely speculative as it has not been previously described.

Our patient experienced status epilepticus in the context of a large acetaminophen overdose and acetylcysteine administration error. The radiographic distribution of the patient’s MR scans, with the reversibility of clinical and radiographical findings were highly suggestive of PRES. Although NAC may have played a role in the pathogenesis of PRES, the underlying mechanism is unclear.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- When the antidote causes harm: preventing errors with intravenous acetylcysteine. ISMP Can Saf Bull. 2023;23(7):1–13. https://ismpcanada.ca/bulletin/when-the-antidote-causes-harm-preventing-errors-with-intravenous-acetylcysteine/#

- Bailey B, McGuigan MA. Management of anaphylactoid reactions to intravenous N-acetylcysteine. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31(6):1–5. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(98)70229-X.

- Kao LW, Kirk MA, Furbee RB, et al. What is the rate of adverse events after oral N-acetylcysteine administered by the intravenous route to patients with suspected acetaminophen poisoning? Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(6):741–750. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(03)00508-0.

- Bailey B, Blais R, Letarte A. Status epilepticus after a massive intravenous N-acetylcysteine overdose leading to intracranial hypertension and death. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44(4):401–406. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.05.014.

- Heard K, Schaeffer TH. Massive acetylcysteine overdose associated with cerebral edema and seizures. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49(5):423–425. doi:10.3109/15563650.2011.583664.

- Fugate JE, Rabinstein AA. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: clinical and radiological manifestations, pathophysiology, and outstanding questions. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(9):914–925. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00111-8.

- Brady E, Parikh NS, Navi BB, et al. The imaging spectrum of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: a pictorial review. Clin Imaging. 2018;47:80–89. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2017.08.008.

- Bartynski WS, Boardman JF. Distinct imaging patterns and lesion distribution in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28(7):1320–1327. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A0549.

- Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B, et al. A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(8):494–500. doi:10.1056/NEJM199602223340803.

- Riley DS, Barber MS, Kienle GS, et al. CARE guidelines for case reports: explanation and elaboration document. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;89:218–235. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.04.026.

- Mullins ME, Yarema MC, Sivilotti MLA, et al. Comment on “transition to two-bag intravenous acetylcysteine for acetaminophen overdose”. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2020;58(5):433–435. doi:10.1080/15563650.2019.1649418.

- Fischer M, Schmutzhard E. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. J Neurol. 2017;264(8):1608–1616. doi:10.1007/s00415-016-8377-8.

- Mant TG, Tempowski JH, Volans GN, et al. Adverse reactions to acetylcysteine and effects of overdose. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984;289(6439):217–219. doi:10.1136/bmj.289.6439.217.

- Spence EEM, Shwetz S, Ryan L, et al. Non-intentional N-acetylcysteine overdose associated with cerebral edema and brain death. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2023;17(1):96–103. Published online February 8 doi:10.1159/000529169.

- Hendrickson RG. What is the most appropriate dose of N -acetylcysteine after massive acetaminophen overdose? Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57(8):686–691. doi:10.1080/15563650.2019.1579914.

- Hieda S, Ishimaru N, Ohnishi J, et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome complicating hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;49:438.e5-438–e6. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2021.04.051.

- John ES, Sedhom R, Dalal I, et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in alcoholic hepatitis: hepatic encephalopathy a common theme. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(2):373–376. doi:10.3748/wjg.v23.i2.373.

- Mann G, Gunja N. Paracetamol overdose complicated by posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES). Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2020;58(1):68–70. doi:10.1080/15563650.2019.1609023.

- Mettananda S, Fernando AD, Ginige N. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in a survivor of valproate-induced acute liver failure: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7(1):144. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-7-144.

- Hershkovitz E, Shorer Z, Levitas A, et al. Status epilepticus following intravenous N-acetylcysteine therapy. Isr J Med Sci. 1996;32(11):1102–1104.