Introduction

This document incorporates recommendations from the 2021 Canadian Thoracic Society (CTS) Guideline – A Focused Update on the Management of Very Mild and Mild AsthmaCitation1 with previous statements and recommendations from the CTS 2010Citation2 and 2012Citation3 asthma guidelines and the CTS/Canadian Pediatric Society 2015 position statement on the diagnosis and management of asthma in preschoolers.Citation4 For the evidence and rationale informing those recommendations and detailed information about preschool asthma, users should refer to the original documents.Citation1–4 Recommendations from previous CTS guidelines were reviewed using the CTS Guideline Update Policy, the review process based on the “living guideline” concept, to determine if the information was still relevant and accurate.Citation5 The recommendations from the CTS 2017 Severe Asthma GuidelineCitation6 have not been incorporated as severe asthma is typically managed in subspecialty clinics, but may be incorporated in future guideline updates.

Summary of new featuresCitation 1 compared to the 2012 guidelineCitation 3

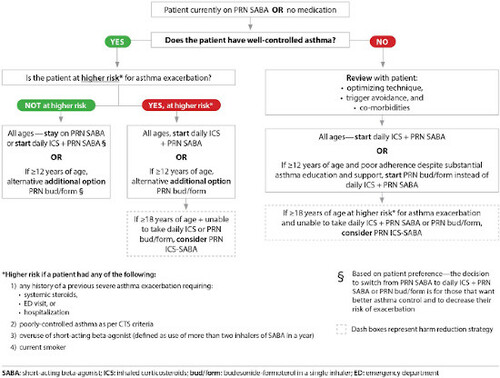

Treatment for very mild asthma. Patients on as needed (PRN) use of a SABA with well-controlled asthma at higher risk for asthma exacerbation should have treatment escalated to daily inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) + PRN SABA (all ages) or PRN budesonide/formoterol (bud/form) (≥12 years of age) (). Daily ICS (all ages) or PRN bud/form (≥12 years of age) are also options for patients on PRN SABA with well-controlled asthma who are not at higher risk for exacerbation, if they prefer to have better asthma control and to decrease their risk of asthma exacerbation.

Previous guidance: Patients with very mild intermittent asthma may be treated with PRN SABA. ICS should be prescribed for those with symptoms even “less than 3 times a week,” those with mild loss of control, or those presenting with an asthma exacerbation requiring systemic steroids.

Treatment for mild asthma. Patients on PRN SABA with poorly-controlled asthma (as per updated CTS criteria) should have treatment escalated to daily ICS + PRN SABA. For individuals ≥12 years of age not controlled on PRN SABA who have poor adherence to daily ICS despite substantial asthma education and support, PRN bud/form is recommended over daily ICS + PRN SABA ().

Previous guidance: Use of an ICS/LABA combination as a reliever in lieu of a fast-acting beta-agonist (FABA) alone was not recommended.

Assessing risk of exacerbation in addition to asthma control. When deciding on optimal treatment, in addition to evaluating asthma control, risk of asthma exacerbation should be assessed based on the criteria presented in .

Previous guidance: Exacerbations should be mild and infrequent, and some risk factors for exacerbation were included within the Asthma Control criteria.

Change in control criteria for daytime symptoms and frequency of reliever need. Those with well-controlled asthma should have daytime symptoms ≤ 2 days per week and need for reliever (SABA or PRN bud/form) ≤ 2 doses per week. For preschoolers, the frequency of symptoms has been changed from ≥8 days/month to >8 days/month to align with criteria for older patients.

Previous guidance: Good asthma control if <4 days per week of daytime symptoms or <4 doses per week of FABA.

Clarification for criteria of mild versus severe asthma exacerbation. A severe asthma exacerbation is one that requires either systemic steroids, an emergency department (ED) visit or hospitalization. A mild exacerbation is an increase in asthma symptoms from baseline that does not require systemic steroids, an ED visit or a hospitalization.

Previous guidance: Severity of exacerbations was not specifically defined.

Update of severity classification. Reclassification of asthma severity to remove the very severe category to align with the Recognition and Management of Severe Asthma Position Statement,Citation6 and to include other asthma therapies.

Previous guidance: Categories such as “mild intermittent” and “mild persistent” asthma were referred to in previous guidelines but are no longer used. This terminology can lead to a misunderstanding of the underlying pathophysiology of asthma as the term “mild intermittent” may suggest to patients that there are times when they do not have asthma when in fact, asthma is a chronic condition and it is only the symptoms that can be intermittent.

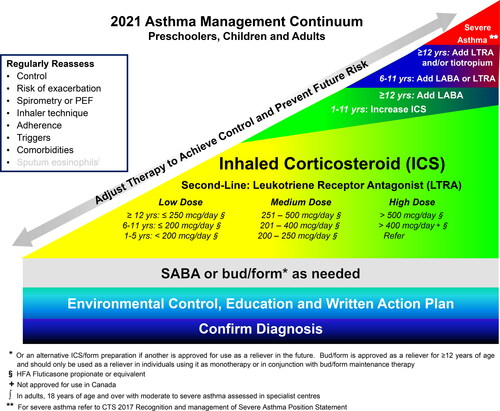

Asthma continuum and ICS dosing table. Reference ICS for dosing in the continuum has been changed to fluticasone propionate equivalents. SABA or bud/form as needed has been extended across the bottom of the continuum (). Dosing categories and treatments have been expanded in the continuum and ICS dosing table () to include preschoolers.

Previous guidance: Historically asthma guidelines used beclomethasone equivalents; however, this can lead to confusion when comparing to other guidelines and reviewing clinical trials as there are 2 forms of beclomethasone available in other countries with different potencies.

Asthma definition

It is recognized that asthma is a heterogenous disorder compromised of many different phenotypes with an increased understanding of the various endotypes or mechanistic pathways. Although some advocate viewing asthma as a component of its parts or treatable traits, outside of severe asthma, current evidence is not to the point where treatment recommendations can be based on phenotypes or endotypes, although trials utilizing this approach are being conducted.Citation7,Citation8 The definition of asthma remains unchanged from the previous CTS 2012 Asthma Guideline:

Asthma is an inflammatory disorder of the airways characterized by paroxysmal or persistent symptoms such as dyspnea, chest tightness, wheezing, sputum production and cough, associated with variable airflow limitation and airway hyper-responsiveness to endogenous or exogenous stimuli. Inflammation and its resultant effects on airway structure and function are considered to be the main mechanisms leading to the development and maintenance of asthma.Citation3

Asthma diagnosis

The diagnosis of asthma is based on a compatible clinical history (see previous definition) with objective evidence of reversible airflow obstruction (). In patients 6 years of age and over, spirometry demonstrating reversible airflow obstruction is the preferred method of confirming a diagnosis of asthma. Since spirometry has a higher specificity than sensitivity for diagnosing asthma, normal spirometry does not rule out a diagnosis of asthma.Citation9

Table 1. Diagnosis of asthma.

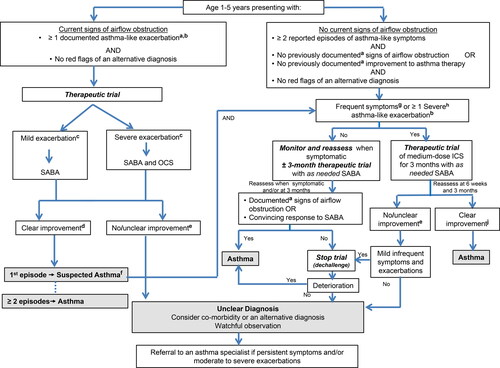

The diagnosis of asthma should be considered in children 1 to 5 years of age with recurrent asthma-like symptoms or exacerbations, even if triggered by viral infections. In children under the age of 6, a compatible clinical history, physical exam and trial of treatment are used to make a clinical diagnosis (, ). Given that up to 50% of children under the age of 6 outgrow their symptoms, a monitored trial off medication can be attempted when asthma is well-controlled with exposure to the child’s typical triggers, including no exacerbations, for at least 3-6 months.Citation10,Citation11

Figure 1. Diagnosis algorithm for children 1 to 5 years of age.

aDocumentation by a physician or trained health care practitioner.bEpisodes of wheezing with/without difficulty breathing.cSeverity of an exacerbation documented by clinical assessment of signs of airflow obstruction, preferably with the addition of objective measures such oxygen saturation and respiratory rate, and/or validated score such as the Pediatric Respiratory Assessment Measure (PRAM) score.dBased on marked improvement in signs of airflow obstruction before and after therapy or a reduction of ≥ 3 points on the PRAM score, recognizing the expected time response to therapy.eA conclusive therapeutic trial hinges on adequate dose of asthma medication, adequate inhalation technique, diligent documentation of the signs and/or symptoms, and timely medical reassessment; if these conditions are not met, consider repeating the treatment or therapeutic trial.fThe diagnosis of asthma is based on recurrent (≥ 2) episodes of asthma-like exacerbations (documented signs) and/or symptoms. In case of a first occurrence of exacerbation with no previous asthma-like symptoms, the diagnostic of asthma is suspected and can be confirmed with re-occurrence of asthma-like symptoms or exacerbations with response to asthma therapy.g>8 days/month with asthma-like symptoms.hSevere exacerbations require any of the following: systemic steroids, hospitalization; or an emergency department visit.IIn this age group, the diagnostic accuracy of parental report of a short-term response to as-needed short-acting β2-agonist (SABA) may be unreliable due to misperception and/or spontaneous improvement of another condition. Documentation of airflow obstruction and reversibility when symptomatic, by a physician or trained health care practitioner, is preferred.jBased on 50% fewer severe exacerbations, shorter and milder exacerbations, and fewer, milder symptoms between episodes.

Asthma management

The core components of asthma management are highlighted in the asthma management continuum () and include: 1) Assessing asthma control and risk of exacerbation, 2) Providing asthma self-management education including a written action plan, 3) Identifying triggers and discussing environmental control if applicable, and 4) Prescribing appropriate pharmacologic treatment to achieve and maintain asthma control which includes minimizing exacerbations.

Figure 2. 2021 Asthma continuum.

Management relies on an accurate diagnosis of asthma and regular reassessment of control and risk of exacerbation. All individuals with asthma should be provided with self-management education, including a written action plan. Adherence to treatment, inhaler technique, exposure to environmental triggers, and the presence of comorbidities should be reassessed at each visit and optimized.

Individuals with well controlled asthma on no medication or PRN SABA at lower risk of exacerbation can use PRN SABA, daily ICS + PRN SABA, and if ≥ 12 years of age PRN bud/form*.

Individuals at higher risk of exacerbation even if well-controlled on PRN SABA or no medication, and those with poorly-controlled asthma on PRN SABA or no medication should be started on daily ICS + PRN SABA. In individuals ≥ 12 years old with poor adherence despite substantial asthma education and support, PRN bud/form* can be considered. LTRA are second-line monotherapy for asthma. If asthma is not adequately controlled by daily low doses of ICS with good technique and adherence, additional therapy should be considered. In children 1-11 years old, ICS should be increased to medium dose and if still not controlled in children 6-11 years old, the addition of a LABA or LTRA should be considered. In individuals 12 years of age and over, a LABA in the same inhaler as an ICS is first line adjunct therapy. If still not controlled, the addition of a LTRA or tiotropium should be considered.

In children who are not well-controlled on medium dose ICS, a referral to an asthma specialist is recommended. After achieving asthma control, including no severe exacerbations, for at least 3-6 months, medication should be reduced to the minimum necessary dose to maintain asthma control and prevent future exacerbations.

HFA, hydrofluoroalkane; SABA, short-acting beta-agonist, LABA, long-acting beta-agonist, ICS, inhaled corticosteroid, LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist, bud/form: budesonide-formoterol in a single inhaler

Asthma control and risk of exacerbation

Asthma control () and risk for exacerbation () should be assessed at each clinical encounter.

Table 2. Well-controlled asthma criteria.

Table 3. Assessing risk for severe exacerbation.

The goal of asthma treatment is to have well-controlled asthma in order to minimize short- and long-term complications, morbidity and mortality.Citation3 Asthma control is often thought of as symptom control; however, the CTS control criteria incorporate all facets of asthma control including: 1) symptoms and impact on quality of life; 2) exacerbations; 3) lung function; and 4) inflammatory markers for adults with moderate to severe asthma. The use of the fraction of exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) as a marker of asthma control was assessed in the CTS 2012 asthma guidelineCitation3 and was not recommended as a routine measurement.

For patients with poorly-controlled asthma, potential reasons for poor control should be assessed and corrected prior to or in conjunction with escalation of pharmacologic therapy. This includes assessment of: adherence, inhalation technique and whether they have been using an empty inhaler, environmental (including occupational) exposures and key comorbidities (eg, rhinosinusitis, gastro-esophageal reflux, paradoxical vocal fold motion, anxiety and depression).Citation6

Individuals can have well-controlled asthma but still be at risk for exacerbation. Specific risk factors for severe exacerbations should be assessed at each clinical encounter (). These risk factors are particularly important when deciding on controller therapy for a patient with very mild or mild asthma.

A more complete list of risk factors for severe exacerbations () and for near-fatal and fatal asthma () are provided to facilitate discussion between clinicians and patients about their individual risk. Patients at risk for near fatal or fatal asthma require careful follow-up, and may benefit from a multi-disciplinary team, given that factors such as non-adherence, substance use and psychiatric illness increase their risk of death from asthma.

Table 4. Risk factors associated with severe asthma exacerbations.

Table 5. Risk factors associated with near-fatal or fatal asthma.Citation 19 ,Citation 20

Asthma education and written action plan

Once a diagnosis of asthma is made, it is important that patients and families receive appropriate asthma self-management education. Key components of an asthma education program are listed in .Citation2

Table 6. Components of an asthma education program.

Written action plan

Written asthma action plans are an important part of care for all patients with asthma.Citation2 They have been shown to decrease exacerbations in children and adults.Citation21,Citation22

There is no clear benefit of peak-flow based action plans in comparison to symptom-based action plans.Citation23,Citation24 The choice between these 2 types of action plans can be individualized based on patient preference and physician judgment, as there are some circumstances (eg, patients with poor symptom perception) where a peak-flow based action plan may be of benefit.

Action plans should outline recommended daily preventive management strategies to maintain control, when and how to adjust reliever therapy (and controller therapy in adults prone to exacerbations) for loss of control and provide clear instructions regarding when to seek urgent medical attention.Citation2 Treatment in the yellow zone of an action plan will be discussed in the pharmacologic treatment section. Examples of action plans for children and adults can be found on the CTS website under Guidelines and Resources at https://cts-sct.ca/guideline-library/knowledge-tools-resources/asthma/

Environmental control

Environmental factors that trigger a patient’s asthma should be identified on history and avoided, if possible. Approximately 36% of adult-onset asthma cases are probably or possibly work-related;Citation25 therefore, it is important to perform a thorough medical and occupational history to identify work-related asthma.

Evidence for the clinical benefit of specific interventions to reduce exposure to indoor allergens in all patients with asthma is lacking.Citation26–29 Given the expense and complexity of these interventions, these are not recommended as a general strategy; however, in patients with asthma symptoms triggered by indoor allergens, it would be prudent to minimize exposure. The current literature suggests that multi-component interventions (eg, use of two or more single-component interventions) are more effective than single-component interventions (eg, HEPA filters, cleaning products, carpet removal, pet removal).Citation30

First- or secondhand exposure to tobacco smoke is a risk factor for asthma exacerbations and counseling on smoking cessation should be provided. Smoking marijuana and vaping are increasing in prevalence, particularly among adolescents, and these exposures are increasingly recognized as a cause for respiratory symptoms and risk for exacerbation in patients with asthma.Citation17,Citation18,Citation31

Pharmacologic treatment

Inhaler device

It is important to consider the type of inhaler device that a patient prefers to use and can use properly before prescribing asthma medication, as most categories of medication come in multiple devices (eg, pressurized meter dose inhaler (pMDI), dry powder inhaler; ). Poor inhaler technique is still seen in up to 70% of patientsCitation32 and is associated with poor asthma control and increased exacerbations.Citation33 The use of valved holding chambers with pMDIs decreases oropharyngeal deposition of medication, increases lower airway deposition and overcomes issues with actuation-inhalation coordination.Citation34 Up to 50% of patients have poor actuation-inhalation coordination with pMDIs;Citation32 thus, valved holding chambers should be recommended for all ages of patients prescribed a pMDI, particularly with inhaled corticosteroids.Citation35 Dry powder inhalers require a minimal inspiratory pressure, which may be difficult in young children and occasionally in adult patients with low FEV1 or other comorbid illnesses such as neuromuscular weakness,Citation36 particularly during asthma exacerbations. For resource with pictures of available asthma medication and videos on proper inhaler technique, see https://cts-sct.ca/guideline-library/knowledge-tools-resources/asthma/.

Table 7. Recommendations for asthma devices by age.Citation 37

Reliever therapy

All individuals with asthma should have access to a reliever for use as needed to treat acute symptoms. In Canada, SABAs (salbutamol, terbutaline), and a combination inhaler (bud/form) are approved for this indication. As needed bud/form is approved for use as a reliever in adults and children ≥12 years of age.

Bud/form is not studied and should not be used as a reliever when controller medications other than maintenance bud/form are used. The use of bud/form as a reliever in patients not on a daily controller medication (p 8), and in those on a fixed dose of bud/form for maintenance (p 8) will be discussed in the Controller Therapy section.

Regular need for a reliever (more than 2 doses per week) merits reevaluation to identify the reason(s) for poorly-controlled asthma. Frequent use of a SABA reliever is a risk factor for severe exacerbations and asthma-related death,Citation16 and the use of more than two inhalers of SABA in a year (typically containing 200 doses each) should prompt reevaluation of asthma control.

SABAs should only be used for symptom relief and should not be regularly used “to open the airways” before daily controller therapy administration as this has been shown to increase risk of exacerbations.Citation1

Controller therapy

The effectiveness of each treatment should be carefully evaluated for its impact on current control, future risk (in particular asthma exacerbations), and side effects.Citation3

The safest and minimum effective ICS dose that acheives the goals of current control and eliminates exacerbations, should be prescribed to minimize side effects in all groups, particularly in children to address the concern regarding growth velocity.

Improvement in clinical symptoms occurs within 1-2 weeks of starting daily ICS,Citation38 although it can take months to see a plateau in improvement.Citation39–41 The dosing table provides comparative dosing for the ICS approved for use in Canada (). There is a plateau in the dose-response curve for ICS in a large number of patients who respond to daily low- to medium-dose ICS that is dose equivalent to 200-250 mcg of fluticasone proprionate.Citation42,Citation43

Table 8. Comparative inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) dosing categories in preschoolers, children and adults.

For patients with poorly-controlled asthma, potential reasons for poor control should be assessed and corrected prior to or in conjunction with escalation of pharmacologic therapy. This includes assessment of: adherence, inhalation technique and whether they have been using an empty inhaler, environmental (including occupational) exposures and key comorbidities (eg, rhinosinusitis, gastro-esophageal reflux, paradoxical vocal fold motion, anxiety and depression).Citation6

Patients not on controller therapy ()

Patients who are well controlled on PRN SABA or no medication with a lower risk for exacerbations can continue PRN SABA or be switched to either daily ICS + PRN SABA (all ages) or PRN bud/form (≥12 years of age) if they prefer to have better asthma control or reduce their risk for exacerbations.Citation1

Patients well-controlled on PRN SABA or no medication who are at higher risk for exacerbations should not be on PRN SABA, even if they have minimal symptoms. They should be switched to daily ICS + PRN SABA (all ages) or PRN bud/form (≥ 12 years of age). Daily ICS + PRN SABA is the recommended controller therapy except for patients ≥ 12 years of age with poor adherence to daily medication despite substantial asthma education and support, for whom PRN bud/form is recommended over daily ICS + PRN SABA.Citation1

Patients who are not controlled on PRN SABA or no medication should be on daily ICS + PRN SABA

The strategy of taking an ICS each time a SABA is taken (PRN ICS-SABA) is not approved for use in Canada, and is only recommended as a harm reduction measure in patients ≥18 years of age at higher risk for exacerbations who are unable to use daily ICS + PRN SABA or PRN bud/form.Citation1 The clinical trial that evaluated this strategy in adults using 2 separate inhalersCitation44 used a regimen of beclomethasone 50 mcg 2 puffs each time salbutamol 100 mcg 2 puffs was used. If clinicians recommend this strategy (off-label), we suggest that the maximum approved daily ICS dose should not be exceeded (see ).

In patients of all ages, leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRAs) are second line to daily ICS.

Patients not achieving control on low dose ICS

Children not achieving asthma control despite adherence to low dose ICS should be increased to medium dose ICS (). Children < 6 years of age, not achieving control on medium dose ICS should be referred to an asthma specialist (section Reasons for Referral).

Children 6-11 years of age not achieving control on medium dose ICS should be started on a second controller medication, either a LABA (in the same inhaler as the ICS) or LTRA. Improvement is overall more likely to be seen with the addition of a LABA; however, individual responses vary and the side effect profile of these medications should also be discussed with patients and parents when making this decision (section Safety of LABA and LTRA).Citation45 In children 6-11 years of age not controlled on low dose ICS, other guidelinesCitation46,Citation47 recommend either increasing to medium dose ICS or adding a LABA, based on the current evidence not showing clear superiority and safety of one regimen over the other. However, the limited approval of ICS/LABA formulations in Canada for children 6-11 years of age precludes a similar recommendation at this time.

Children ≥12 years of age and adults not achieving control despite adherence to low dose ICS should be started on daily ICS/LABA. Alternative options include adding an LTRA or increasing to a medium dose of ICS.

Individuals ≥12 years of age and adults on an ICS/LABA with poor control or who are prone to exacerbations can be switched to bud/form maintenance and reliever therapy at the same maintenance ICS dose.

Patients not achieving control on moderate dose ICS + second controller medication

Health care providers are referred to the CTS 2017 position statement on the Recognition and Management of Severe AsthmaCitation6 for further recommendations on assessment and management.

Safety of LABA and LTRA

The safety of LABA taken in conjunction with ICS has been demonstrated in large trials,Citation48 and there is no longer a black box warning on LABA medications. They are still, however, not to be used as monotherapy. A new black box warning has been issued for LTRAs due to neuropsychiatric side effects, most commonly irritability, aggressiveness, anxiety and sleep disturbance including suicidal thoughts or actions.Citation49 These side effects have been reported in up to 16% of pediatric asthma patients started on montelukast and typically occurred within 2 weeks of initiation.Citation50,Citation51

Yellow zone management ()

It is not recommended that children and adults on maintenance ICS double the dose of their ICS with acute loss of asthma control given the lack of benefit of this approach.

Table 9. Yellow Zone action plan recommendations based on age and maintenance controller therapy.

In children (<16 years of age and older) it is not recommended that the ICS dose be increased by 4-fold or more given the lack of benefit of this approach. This was recently confirmed in a trial of 5 to 11 year olds examining fluticasone 200 mcg/day versus 1000 mcg/day in the yellow zone, which did not find any decrease in exacerbations.Citation52

In adults (≥16 years of age) with a history of a severe exacerbation in the last year, a trial of a 4 or 5-fold increase in maintenance ICS dose for 7-14 days is suggested. A pragmatic trial of adults (16 years of age and older) compared quadrupling the dose of ICS in the yellow zone to maintaining the same baseline dose and found a modest improvement in severe exacerbations (45% in the quadrupling group vs 52% in the control group, hazard ratio for time to first exacerbation 0.81, 95% confidence interval 0.71-0.92, p = 0.002) at the expense of increased dysphonia and oral candidiasis in the quadrupling group.Citation53

In adults (≥16 years of age) on daily bud/form, it is suggested that the dose be increased to a maximum of 4 inhalations twice daily for 7-14 days, as this has been shown to decrease severe exacerbations.Citation3

Evidence for increasing doses for other ICS/LABA formulations is lacking, and for adult patients on daily ICS/LABA other than bud/form, a 4-fold or greater increase in ICS dose for 7-14 days or a course of systemic steroids is only suggested for adults that are exacerbation prone. Health care providers should be aware of the maximum daily LABA dose approved for adult use in Canada (salmeterol 100 mcg, formoterol 48 mcg, vilanterol 25 mcg). A tool to assist clinicians prescribe increased doses of ICS or ICS/LABA in the yellow zone is available in the Guidelines and Resources section of the CTS website at https://cts-sct.ca/guideline-library/knowledge-tools-resources/asthma/.

It is not recommended to routinely add oral corticosteroids as part of a written action plan in children or adults except in patients with recent severe exacerbations who fail to respond to inhaled SABA as part of their written action plan.

Prednisone dose and duration in adults should be individualized based on previous or current response. A dose of 30 to 50 mg/day for at least 5 days is suggested. For children suggested dose is 1 mg/kg/day (maximum 50 mg) for at least 3 days.

Any severe exacerbation (requiring use of systemic steroids, ED visit or hospitalization) is an indication to start a controller therapy for patients only on PRN SABA (see ) and for all patients is an indication for a reassessment of asthma mangement. Frequent courses of oral corticosteroid should prompt referral to a specialist (see the Reasons for referral section).

Asthma severity

Asthma severity is defined by the intensity of medication required to maintain asthma control. Given that it can only be determined once asthma control is achieved, categorization of asthma severity is not useful to guide treatment decisions except when a patient meets the criteria for severe asthma and other therapeutic options are available.Citation6 This classification () is an update to the 1999 criteria and is provided to standardize terminology. It is important to highlight that even those with very mild or mild asthma are at risk for asthma-related morbidity, including exacerbations and mortality.Citation19

Table 10. Severity classification.

Reasons for referral

A referral to an asthma specialist for consultation or co-management is recommended for the following reasons:

Diagnostic uncertainty

Children not controlled on moderate dose ICS with correct inhaler technique and appropriate medication adherence

Suspected or confirmed severe asthma

Life-threatening event such as an admission to the ICU for asthma

Need for allergy testing to assess the possible role of environmental allergens in those with a suggestive clinical history

Confirmed or suspected work-related asthma or

Any asthma hospitalization (all ages), ≥ 2 ED visits (all ages) or ≥ 2 courses of systemic steroids (children)

An asthma specialist includes specialists in asthma, general respirology, pediatrics, and/or allergy/immunology who have access to lung function, certified asthma/respiratory educators/nurse clinicians +/- FeNO, induced sputum analysis.Citation6

Questions for future guidelines to address

These topics were identified during the update of this guideline as areas where there is differing recommendations in international and national guidelines, or where a specific clinical question has not been addressed in the past or requires updating.

Sensitivity and specificity of peak flow change after bronchodilator or trial of controller medication for the diagnosis of asthma

Sensitivity and specificity of exhaled nitric oxide for the diagnosis of asthma

Sensitivity and specificity of different challenge tests for the diagnosis of asthma

Sensitivity and specificity of different diagnostic algorithms for the diagnosis of asthma

Contribution of diurnal variation in assessing asthma control

90% of personal best FEV1 for cut-off to define well-controlled asthma

Safety and efficacy of ICS-LABA medication in children 6-11years of age compared to moderate dose ICS

Safety and efficacy of daily seasonal use of asthma controller therapy versus daily use year-round in those with seasonal triggers

Safety and efficacy of sublingual or subcutaneous immunotherapy for the treatment of asthma

Safety and efficacy of combination ICS/LABA/LAMA (long-acting muscarinic antagonists) for the treatment of asthma

Safety and efficacy of combination ICS/LAMA for the treatment of asthma

Performance metrics for monitoring practice concordance with guideline recommendations

Health care providers wishing to monitor adherence to the key recommendations in this guideline may use the following parameters:

Patients 1-5 years of age with suspected asthma who have documentation by trained health care provider of wheeze or other signs of airflow obstruction and improvement with SABA or documentation of caregiver report of response to 3-month trial of medium dose ICS or SABA (numerator) among patients 1-5 years of age with suspected asthma (denominator)

Patients 6 years of age and older with suspected asthma who have spirometry as part of diagnostic workup for asthma (numerator) among patients 6 years of age and older with suspected asthma

Number of clinic visits for asthma where asthma control and risk for exacerbation are assessed (numerator) among total clinic visits for asthma (denominator)

Number of patients with poorly-controlled asthma who have medication adherence and inhalation technique assessed (numerator) among patients with poor asthma control (denominator)

Number of patients with poorly-controlled asthma provided with asthma education (numerator) among patients with poor asthma control (denominator)

Number of patients with asthma referred for spirometry as part of asthma control assessment (numerator) among total number of asthma patients (denominator)

Patients with well-controlled asthma at high risk for exacerbation or patients with poorly-controlled asthma prescribed a controller medication (numerator) among patients with well-controlled asthma at high risk for exacerbation or patients with poorly controlled asthma (denominator)

Patients with asthma prescribed a reliever medication (SABA or bud/form) (numerator) among patients with asthma (denominator)

Patients prescribed short courses of ICS (numerator) among patients with asthma (denominator) (practice should not occur)

Adults with one asthma hospitalization or ≥2 ED Visits seen by asthma specialist (numerator) among adults with one asthma hospitalization or ≥2 ED visits for asthma (denominator)

Children with one asthma hospitalization or ≥2 ED Visits or ≥2 courses of systemic steroids seen by asthma specialist (numerator) among children with one asthma hospitalization or ≥2 ED Visits or ≥2 courses of systemic steroids (denominator)

Children with uncontrolled asthma on moderate dose ICS (with good technique and adherence) seen by asthma specialist (numerator) among children uncontrolled on moderate dose ICS (denominator)

Children or adults with suspected or confirmed severe asthma seen by asthma specialist (numerator) among children or adults with suspected or confirmed severe asthma (denominator)

Definitions

Preschool = refers to children ≥ 1 year of age to 5 years of age

Children = refers to children ≥ 6 years of age to 11 years of age

Adult = refers to individuals ≥ 12 years of age unless otherwise specified, individuals 12-18 years of age are included in this category because medication approval is often for patients ≥12 years of age, however, patients 12 to 18 years of age (particularly those who are pre-pubertal) are at higher risk for some medication side-effects such as growth suppression and should be monitored similarly to children

Controller = A medication taken daily to decrease airway inflammation, maintain asthma control and prevent exacerbations

Reliever = A medication taken only as needed for quick relief of symptoms (eg, SABA, bud/form); use of >2 doses of reliever medication in a week is a sign of poorly-controlled asthma (the number of actuations in a dose is variable depending on the reliever medication but is often 1-2 actuations)

SABA = Short-acting beta-agonist (eg, salbutamol, terbutaline)

LABA = Long-acting beta-agonist (e.g., salmeterol, formoterol, vilanterol)

FABA = Fast-acting beta-agonist which can either be a short-acting beta-agonist or a long-acting beta-agonist with rapid onset of action. In Canada, formoterol in a single inhaler with budesonide is approved for use as a fast-acting beta-agonist. The term is used in this document in reference to previous CTS guidelines, however for clarity the terms SABA and bud/form will be used when appropriate

LTRA = Leukotriene receptor antagonist

LAMA = Long-acting muscarinic antagonist

bud/form = Single inhaler of budesonide and formoterol

PRN ICS-SABA = As needed use of an inhaled corticosteroid each time a short-acting beta-agonist is taken; in Canada, this would be in 2 separate inhalers as there is not currently a single inhaler containing ICS and SABA

Severe exacerbation: an exacerbation requiring any of the following:

systemic steroids

emergency department visit; or

hospitalization

Mild exacerbation: an increase in asthma symptoms from baseline that does not require systemic steroids, an emergency department visit or a hospitalization. Differentiating this from chronic poorly- controlled asthma may only occur retrospectively.

Higher risk of exacerbation is defined by presence of any of the following:

any history of a previous severe asthma exacerbation (requiring either systemic steroids, ED visit or hospitalization);

poorly-controlled asthma as per CTS criteria;

overuse of SABA (using more than 2 inhalers of SABA in 1 year); or

being a current smoker.

Individuals without any of these features have a lower risk of exacerbation.

Well-controlled asthma: Asthma in which all criteria for well-controlled asthma are met ()

Poorly-controlled asthma: Asthma in which any one of the criteria for well-controlled are not met ().

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to recognize and thank CTS staff (Anne Van Dam), CTS member (Om Kurmi), CTS Executive members (Dina Brooks, Paul Hernandez, Richard Leigh, Mohit Bhutani, and John Granton), CTS CRGC Executive members (Samir Gupta and Christopher Licskai), and CTS Asthma Assembly Steering Committee members (Diane Lougheed, Francine Ducharme, Dhenuka Radhakrishnan, Andréanne Côté, Tania Samanta) for their input and guidance. We would also like to acknowledge with sincere appreciation our expert reviewers who made valuable contributions to the manuscript: Andrew Menzies-Gow, Director of the Lung Division, Deputy Medical Director, Royal Brompton & Harefield National Health Service Foundation Trust, London, England; Robert Newton, Professor and Head, Department of Physiology & Pharmacology, Airways Inflammation Research Group, Snyder Institute for Chronic Diseases, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta; Emilie Zannis, Clinical Editor, Canadian Pharmacists Association, Ottawa, Ontario; Yue Chen, Professor, School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario.

Disclosure statement

Members of the CTS Asthma Guideline Panel declared potential conflicts of interest at the time of appointment and these were updated throughout the process in accordance with the CTS Conflict of Interest Disclosure Policy. Individual member conflict of interest statements are posted on the CTS website.

References

- Yang CL, Hicks EA, Mitchell P, et al. 2021 Canadian Thoracic Society Guideline – A focused update on the management of very mild and mild asthma. Can J Respir Criti Care Sleep Med. 2021;5(4). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/24745332.2021.1877043.

- Lougheed MD, Lemière C, Dell SD, Canadian Thoracic Society Asthma Committee, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society Asthma Management Continuum-2010 Consensus Summary for children six years of age and over, and adults. Can Respir J. 2010;17(1):15–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/827281.

- Lougheed MD, Lemiere C, Ducharme FM, Canadian Thoracic Society Asthma Clinical Assembly, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society 2012 guideline update: diagnosis and management of asthma in preschoolers, children and adults. Can Respir J. 2012;19(2):127–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/635624.

- Ducharme FM, Dell SD, Radhakrishnan D, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Asthma in Preschoolers: A Canadian Thoracic Society and Canadian Paediatric Society Position Paper. Can Respir J. 2015;22:101572.

- Canadian Thoracic Society. Canadian Thoracic Society Guideline/Position Statement Update Policy - 2016. Available at: https://cts-sct.ca/guideline-library/methodology/. Accessed on December 8, 2020.

- FitzGerald JM, Lemiere C, Lougheed MD, et al. Recognition and management of severe asthma: A Canadian Thoracic Society position statement. Can J Respir Crit Care Sleep Med. 2017;1(4):199–221. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/24745332.2017.1395250.

- Lazarus SC, Krishnan JA, King TS, et al. Mometasone or Tiotropium in Mild Asthma with a Low Sputum Eosinophil Level. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(21):2009–2019. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1814917.

- Pavord ID, Beasley R, Agusti A, et al. After asthma: redefining airways diseases. The Lancet. 2018;391(10118):350–400. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30879-6.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK). Asthma: diagnosis and Monitoring of Asthma in Adults, Children and Young People. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK); 2017. Nov. PMID: 29206391.

- Castro-Rodriguez JA, Holberg CJ, Wright AL, et al. A Clinical Index to Define Risk of Asthma in Young Children with Recurrent Wheezing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(4 Pt 1):1403–1406. doi:https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.162.4.9912111.

- Hallas HW, Chawes BL, Rasmussen MA, et al. Airway obstruction and bronchial reactivity from age 1 month until 13 years in children with asthma: A prospective birth cohort study. PLoS Med. 2019;16(1):e1002722. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002722.

- Reddel HK, Taylor DR, Bateman ED, American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Task Force on Asthma Control and Exacerbations, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: asthma control and exacerbations: standardizing endpoints for clinical asthma trials and clinical practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(1):59–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200801-060ST.

- Coates AL, Wanger J, Cockcroft DW, the Bronchoprovocation Testing Task Force, et al. ERS technical standard on bronchial challenge testing: general considerations and performance of methacholine challenge tests. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(5):1601526. doi:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01526-2016.

- Buelo A, McLean S, Julious S, ARC Group, et al. At-risk children with asthma (ARC): a systematic review. Thorax. 2018;73(9):813–824. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210939.

- British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. British guideline on the management of asthma. 2019. Available from: https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/guidelines/asthma/. Accessed on September 18, 2020.

- Nwaru BI, Ekström M, Hasvold P, et al. Overuse of short-acting β2-agonists in asthma is associated with increased risk of exacerbation and mortality: a nationwide cohort study of the global SABINA programme. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(4):1901872. doi:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01872-2019.

- Bayly JE, Bernat D, Porter L, et al. Secondhand Exposure to Aerosols From Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems and Asthma Exacerbations Among Youth With Asthma. Chest. 2019;155(1):88–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2018.10.005.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on the Review of the Health Effects of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. Eaton DL, Kwan LY, Stratton K, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). 2018.

- Royal College of Physicians. Why asthma still kills: the National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD) Confidential Enquiry report. 2014. Available from: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/why-asthma-still-kills. Accessed on September 18, 2020.

- To T, Zhu J, Williams DP, et al. Frequency of health service use in the year prior to asthma death. J Asthma. 2016;53(5):505–509. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2015.1064949.

- Bhogal SK, Zemek RL, Ducharme F. Written action plans for asthma in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006; Issue (3)Art. No.: CD005306.

- Gibson PG, Powell H, Wilson A, et al. Self-management education and regular practitioner review for adults with asthma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1998; Issue (4)Art. No.: CD001117.

- Buist AS, Vollmer WM, Wilson SR, et al. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Peak Flow versus Symptom Monitoring in Older Adults with Asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(10):1077–1087. doi:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200510-1606OC.

- Adams RJ, Boath K, Homan S, et al. A randomized trial of peak-flow and symptom-based action plans in adults with moderate-to-severe asthma. Respirology. 2001;6(4):297–304. doi:https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1843.2001.00350.x.

- Johnson AR, Dimich-Ward HD, Manfreda J, et al. Occupational Asthma in Adults in Six Canadian Communities. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(6):2058–2062. doi:https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.9805079.

- Campbell F, Gibson PG. Feather versus non‐feather bedding for asthma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2000; Issue (4). Art. No.: CD002154.

- Gøtzsche PC, Johansen HK. House dust mite control measures for asthma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008; Issue (2). Art. No.: CD001187.

- Kilburn SA, Lasserson TJ, McKean MC. Pet allergen control measures for allergic asthma in children and adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2003; Issue (1). Art. No.: CD002989.

- Singh M, Jaiswal N. Dehumidifiers for chronic asthma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013; Issue (6). Art. No.: CD003563.

- Cloutier MM, Baptist AP, Blake KV, Expert Panel Working Group of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) administered and coordinated National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Coordinating Committee (NAEPPCC), et al. 2020 Focused Updates to the Asthma Management Guidelines: A Report from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Coordinating Committee Expert Panel Working Group. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(6):1217–1270. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2020.10.003.

- Clapp PW, Peden DB, Jaspers I. E-cigarettes, vaping-related pulmonary illnesses, and asthma: A perspective from inhalation toxicologists. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(1):97–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2019.11.001.

- Sanchis J, Gich I, Pedersen S, Aerosol Drug Management Improvement Team (ADMIT) Systematic Review of Errors in Inhaler Use: Has Patient Technique Improved Over Time?Chest. 2016;150(2):394–406. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2016.03.041.

- Price DB, Román-Rodríguez M, McQueen RB, et al. Inhaler Errors in the CRITIKAL Study: Type, Frequency, and Association with Asthma Outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(4):1071–1081.e1079. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2017.01.004.

- Lavorini F, Barreto C, van Boven JFM, et al. Spacers and Valved Holding Chambers-The Risk of Switching to Different Chambers. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(5):1569–1573. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2019.12.035.

- Volerman A, Balachandran U, Siros M, et al. Mask Use with Spacers/Valved Holding Chambers and Metered Dose Inhalers among Children with Asthma. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(1):17–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.202005-522CME.

- Clark AR, Weers JG, Dhand R. The Confusing World of Dry Powder Inhalers: It Is All About Inspiratory Pressures, Not Inspiratory Flow Rates. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2020;33(1):1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/jamp.2019.1556.

- Laube BL, Janssens HM, de Jongh FH, International Society for Aerosols in Medicine, et al. What the pulmonary specialist should know about the new inhalation therapies. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(6):1308–1331. doi:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00166410.

- Vathenen AS, Knox AJ, Wisniewski A, et al. Time Course of Change in Bronchial Reactivity with an Inhaled Corticosteroid in Asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143(6):1317–1321. doi:https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm/143.6.1317.

- Bateman ED, Boushey HA, Bousquet J, et al. Can Guideline-defined Asthma Control Be Achieved?Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(8):836–844. doi:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200401-033OC.

- Brand PL, Duiverman EJ, Waalkens HJ, et al. Peak flow variation in childhood asthma: correlation with symptoms, airways obstruction, and hyperresponsiveness during long-term treatment with inhaled corticosteroids. Dutch CNSLD Study Group. Thorax. 1999;54(2):103–107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.54.2.103.

- Kerstjens HA, Brand PL, de Jong PM, et al. Influence of treatment on peak expiratory flow and its relation to airway hyperresponsiveness and symptoms. The Dutch CNSLD Study Group. Thorax. 1994;49(11):1109–1115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.49.11.1109.

- Beasley R, Holliday M, Reddel HK, et al. Controlled Trial of Budesonide–Formoterol as Needed for Mild Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(21):2020–2030. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1901963.

- Zhang L, Axelsson I, Chung M, Lau J. Dose response of inhaled corticosteroids in children with persistent asthma: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2011;127(1):129–138. doi:https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-1223.

- Calhoun WJ, Ameredes BT, King TS, Asthma Clinical Research Network of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, et al. Comparison of physician-, biomarker-, and symptom-based strategies for adjustment of inhaled corticosteroid therapy in adults with asthma: the BASALT randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;308(10):987–997. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/2012.jama.10893.

- Lemanske RF, Mauger DT, Sorkness CA, et al. Step-up Therapy for Children with Uncontrolled Asthma Receiving Inhaled Corticosteroids. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(11):975–985. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1001278.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Advisory Council Asthma Expert Working Group. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma (EPR-3). 2007. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/guidelines-for-diagnosis-management-of-asthma. Accessed on September 18, 2020.

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2020. Available from: www.ginasthma.org. Accessed on September 18, 2020.

- Stempel DA, Szefler SJ, Pedersen S, VESTRI Investigators, et al. Safety of Adding Salmeterol to Fluticasone Propionate in Children with Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):840–849. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1606356.

- USA Food and Drug Administration. FDA requires Boxed Warning about serious mental health side effects for asthma and allergy drug montelukast (Singulair); advises restricting use for allergic rhinitis. Available at:https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-requires-boxed-warning-about-serious-mental-health-side-effects-asthma-and-allergy-drug#:∼:text=FDA%20is%20requiring%20a%20Boxed,allergy%20medicine%20montelukast%20(Singulair). 2020. 3-4-2020 FDA Drug Safety Communication(Accessed on November 3, 2020.).

- Benard B, Bastien V, Vinet B, et al. Neuropsychiatric adverse drug reactions in children initiated on montelukast in real-life practice. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(2):1700148. doi:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00148-2017.

- Glockler-Lauf SD, Finkelstein Y, Zhu J, et al. Montelukast and Neuropsychiatric Events in Children with Asthma: A Nested Case-Control Study. J Pediatr. 2019;209:176–182.e174. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.02.009.

- Jackson DJ, Bacharier LB, Mauger DT, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute AsthmaNet, et al. Quintupling Inhaled Glucocorticoids to Prevent Childhood Asthma Exacerbations. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(10):891–901. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1710988.

- McKeever T, Mortimer K, Wilson A, et al. Quadrupling Inhaled Glucocorticoid Dose to Abort Asthma Exacerbations. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(10):902–910. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1714257.