ABSTRACT

Brexit has been the most important issue in British politics in recent years. Whereas extra-parliamentary actors dominated the run-up to the 2016 referendum, the issue moved back to Parliament after the vote. This paper analyses newspaper reporting on Brexit in major British outlets during the post-referendum phase from July 2017 to March 2019. We study the visibility of Members of Parliament to assess whether the debate was balanced between parties and individual MPs relative to their vote and seat share. We conduct an automated text analysis of 58,247 online and offline newspaper articles covering the ideological spectrum from left to right, and from pro-Brexit to anti-Brexit. Our main findings are: (1) Conservative politicians dominated the debate, and (2) organized pro-Brexit MP pressure groups such as ‘Leave Means Leave’ were disproportionally more visible. This means that reporting was biased towards Conservative MPs and within the Conservative Party towards supporters of a hard Brexit. These findings are remarkably stable across different types of newspapers. The results challenge previous analyses that found a higher degree of balance in reporting but corroborate recent studies on the tonality of Brexit reporting that found a pro-Brexit bias.

Introduction

The United Kingdom's vote to leave the European Union on 23 June 2016 has unquestionably been the most important political decision in the country's recent history. Britain's relationship with Europe has been a contentious one ever since it joined the European Community in 1973. While domestic opposition to membership was initially confined to the fringes of Labour and the Conservative Party (Geddes Citation2004; Forster Citation2002), it was catapulted to the centre by David Cameron's promise to hold a referendum after the success of UKIP in the 2014 European elections (Gowland Citation2017; Startin Citation2015). However, the referendum did little to settle the debate. Following a narrow victory of the Leave campaign, public opinion remained almost evenly divided (YouGov Citation2019). This division was mirrored in the British parliament, where votes on the withdrawal agreement and potential alternatives showed no clear majority for any solution (Aidt, Grey and Savu Citation2019).

The political debate in the run-up to the referendum was primarily characterized by competition between the Leave and the Remain campaigns, cutting across political parties and even splitting the Cabinet. The vote also divided the British newspaper landscape, where editorials have traditionally expressed preferences for specific parties or policies, including EU membership (Young Citation1999; Forster Citation2002; Daddow Citation2012; Firmstone Citation2016). After the referendum, the debate shifted back to the parliamentary arena, where the aim was to come to terms with Brexit and negotiate a withdrawal agreement with the EU. During this post-referendum stage, parties began to shift their Brexit stances. The Conservatives adopted an unequivocal pro-Leave position, although a considerable share of their MPs remained committed to the Remain side. At the same time Labour meandered from cautiously pro-Remain to purposely undecided. Furthermore, the post-referendum debate was characterized by the rise of new opinion leaders such as Jacob-Rees-Mogg (Conservative), Keir Starmer (Labour) and Chukka Ummana (Labour/Change UK/Liberal Democrats).

Against this backdrop, the analysis of newspaper reporting on Brexit can shed light on an important issue – mass media has the potential to shape public opinion (Zaller Citation1996, Bartels Citation1993, Broockman and Kalla Citation2016, Baum Citation2002) and biased reporting, in particular, may shift public opinion over time. Furthermore, previous studies on political news reporting in the UK have found that British newspapers exhibit strong ideological leanings (Brandenburg Citation2005, 2006). Studies on the Brexit reporting of UK newspapers likewise found that reporting during the referendum campaign favoured Brexit (Levy et al. Citation2016; Deacon et al. Citation2016; Muhammad Citation2018; Aftab Citation2018). However, there is as of yet little research on newspaper reporting on the period after the referendum. Therefore, the implications of the return of the Brexit debate to Parliament are unclear. Hence this paper asks: How balanced was newspaper reporting on Brexit under Theresa May's government?

This article studies the visibility of individual MPs to assess potential biases in British newspaper reporting on Brexit. Rather than focusing on the ideological slant or tonality of articles, we focus on how frequently particular MPs were mentioned. We argue that mentioning MPs presents an important information shortcut for voters, while also allowing for a straightforward assessment of reporting biases. The pattern of potential bias will be analysed for government functions, parties, pressure groups but also individual MPs. Focusing on the period between July 1st, 2017, just after the minority government of Theresa May took office, and the originally scheduled Brexit date of March 29th, 2019, we conduct an automated text analysis of 58,247 newspaper articles from major national newspaper outlets, covering the entire ideological spectrum, different Brexit positions, different target groups and publication venues. Our main findings are as follows: (1) Conservative politicians dominated the Brexit debate, and (2) pro-Brexit MP pressure groups such as ‘Leave Means Leave (LML)’ and the ‘European Research Group (ERG)’ were significantly overrepresented, in stark contrast to anti-Brexit groups like the ‘People's Vote Campaign (PVC)’. Notably, these findings are robust across newspapers, print and online editions, as well as front – and backbenchers.

The article proceeds as follows: In the next section, we provide a brief discussion of scholarship on media biases and Brexit reporting. Based on this, the third section defines the dependent variable and formulates expectations about Brexit reporting, before the fourth section introduces the period of analysis, the newspaper selection and the measurement concept. Our fifth section presents and discusses the empirical results for visibility across parties, newspapers and institutional roles, whereas the sixth section provides more information on the visibility of individual MPs. The final section concludes and sets the findings into a broader context.

Media influence, media bias and Brexit

Three aspects of the literature are particularly relevant for our research: (1) the literature on newspaper influence on political debates, (2) the literature on balance and bias of newspaper reporting and (3) the literature on Brexit and Euroscepticism in Britain. We discuss relevant concepts and findings from each in turn.

Political stances of newspapers and their influence on political debates

The media are generally assumed to shape public opinion (Zaller Citation1996, Bartels Citation1993, Broockman and Kalla Citation2016, Baum Citation2002). Nevertheless, this effect may be mediated by the degree of exposure during election campaigns (Kalla and Broockman Citation2018) or the multitude of opinions in news outlets with which citizens are confronted (Mutz and Martin Citation2001). Given the impact of the media on the public and public discourse, it is hence crucial which viewpoints the media represents.

In recent years, a considerable amount of research has been devoted to the political leanings of editorial positions. While there is no consensus about the degree to which media reporting is ideologically charged, scholars have generally acknowledged that different news outlets emphasize different issues and/or political perspectives, which can be summarized as ideological stances (Eilders Citation2002; Gentzkow and Shapiro Citation2006; Groeling Citation2008; Groseclose and Milyo Citation2005). Distinct editorial stances can be identified in virtually any free and competitive news market (Hallin and Mancini Citation2007). Nevertheless, they do not characterize all news reporting to the same degree; rather, they vary across policy issues (see e.g. Eilders et al. Citation2004 study on Germany).

Concerning British news organizations, research has shown that these are characterized by markedly partisan editorial stances (Brandenburg Citation2006), begging the question whether Brexit posed a sufficiently sizeable external shock for news desks to stray from their conventional editorial lines and exhibit increasing levels of similarity in their reporting. It should be noted that there is a conceptual distinction between news reporting and editorial stances; however, there is ample evidence that this distinction is more relevant in theory than in practice (Adam et al. Citation2019; Berkel Citation2006; Eilders Citation1999; Kahn and Kenney Citation2002). While position-taking may be less overt in news reporting than in editorials, journalists at the news desk have numerous strategies at their disposal to ensure that their accounts echo the positions of the editorial desk – not the least important of which are ‘opportune witnesses’ (Hagen Citation1993), i.e. giving more prominence to voices that support the editorial line. In this sense, the actors that appear in news reports provide a useful and systematic indicator for the slant of reporting (see also below). The analysis, therefore, requires to consider the editorial stances on the left-right and the pro-/anti-Brexit dimension.

The visibility of politicians in media coverage

From a normative point of view, it is crucial for the functioning of democracies that the media supplies voters with balanced information on political actors (Eberl et al. Citation2017). Similarly, politicians need to be visible to be (re-)elected and engage with the media for this purpose (Hopmann et al. Citation2010). Hence, media outlets have a strong influence on how – and through whom – citizens perceive and engage with politics, making balanced reporting a crucial standard for evaluating the news.

The question of how the press covers political actors and events has been of pronounced scholarly interest (see e.g. Brandenburg Citation2005, Citation2006; Hopmann et al. Citation2010, Citation2011a; Eberl et al. Citation2017). Hereby, studies have among others relied on concepts such as ‘media bias’ or ‘media balance’ to analyse the extent to which the media over- or under-report political actors or issues. Despite conceptual differences, one can argue that bias and balance are two sides of the same coin: bias is the degree to which a news report favours a political side, whereas balance is the degree to which it refrains from doing so (Eberl et al. Citation2017). Three dimensions of the concepts media bias/balance can be distinguished: visibility bias, tonality bias, and agenda bias (see e.g. Brandenburg Citation2005, Citation2006; Hopmann et al. Citation2010, Citation2011a; Eberl et al. Citation2017; for a different classification see D’Alessio and Allen Citation2000), where tonality bias pertains to the favourability of coverage, agenda bias relates to the link between actors and issues in news coverage, and visibility bias refers to the amount of news coverage. The particular importance of visibility bias for political competition and opinion formation is thereby highlighted by Hopman et al. (Citation2010) who find that Danish politicians benefited electorally from greater visibility; similar results are presented by Oegema and Kleinnijenhuis (Citation2000) for the Netherlands.

The degree of media bias naturally depends on the political realities within a political system. Hopmann et al. (Citation2011a) show that media coverage tends to be equally distributed between major political actors – i.e. it treats the most promising candidates equally or covers opinions from both the majority and the minority. From this point of view, balanced media coverage is either proportional to electoral strength or political power (Hopmann et al. Citation2011b). However, since media outlets rely on news values such as relevance/importance and conflict when selecting the news (Shoemaker and Reese Citation2014), coverage can become biased – for instance, when the media focus on newsworthy conflicts (Entman Citation2010). Brandenburg (Citation2005, Citation2006) shows that media coverage of UK parties, in general, differs considerably between newspapers concerning the visibility of parties. Our analysis, therefore, focuses on visibility but is conducted separately for different newspapers to control for variations in political leanings.

Euroscepticism and Brexit in British newspapers and broadcast TV

Newspapers and broadcast media continue to play an essential role in shaping public opinion about Europe in the UK (Carey and Burton Citation2004; de Vreese Citation2007; Vliegenthart et al. Citation2008; Copeland and Copsey Citation2017). After initially adopting a broadly pro-European stance that highlighted the economic benefits of European Community membership (Wilkes and Wring Citation1998), many print outlets came to focus more heavily on ideological arguments over time. Thereby, they became one of the key drivers of Euroscepticism in the country. Long-term studies of print media show a slow but steady increase of bias in favour of Eurosceptic positions. For instance, based on their analysis of over 16,000 newspaper articles, Copeland and Copsey (Citation2017) show a marked decline in positive and neutral reporting about the EU and an increase in negative coverage of critical events across newspapers between 1976 and 2013. Other long-term studies, such as Wilkes and Wring (Citation1998), Young (Citation1999), Forster (Citation2002) and Daddow (Citation2012) as well as analyses of more recent debates (e.g. Hawkins Citation2012) come to similar conclusions, i.e. they all point to right-of-centre news outlets and tabloids as the reason for the shift in the debate. Although direct causality may often be difficult to establish, Foos and Bischof (Citation2019) provide corroborating evidence based on the British Social Attitudes Survey. They demonstrate that the local boycott of the right-wing eurosceptic tabloid ‘The Sun’ in Merseyside (North England) since 1989 led to a significant decrease in Eurosceptic attitudes.

Scholarship on media coverage of the EU referendum campaign also underscores the existence of an anti-EU/pro-Brexit bias (for an overview see Aftab Citation2018; Rawlinson Citation2019). In a comprehensive analysis of press coverage, Levy, Aslan and Bironzo (Citation2016) show that pro-Leave dominated the public debate in the months before the vote. Studies of newspaper editorials on the EU referendum (Firmstone Citation2016) and coverage in major newspapers (Aftab Citation2018, Muhammad Citation2018, Deacon et al. Citation2016) similarly highlight bias in coverage – both in terms of quantity and content – across newspaper outlets and the consequences of the highly partisan UK newspaper landscape for the outcome of the vote. Furthermore, political scientists and communication scholars have explored how media outlets, and TV stations in particular, constructed and implemented their own impartiality guidelines as well as their influence on reporting. Thereby, early academic reactions (see e.g. contributions in Jackson, Thorson and Wing Citation2016), as well as more comprehensive studies, point towards a failure of the press to paint a balanced picture of the campaign.

In terms of the visibility of individual actors, reporting exhibited explicit biases. Most prominently, Cushion and Lewis’ (Citation2017) study of TV news bulletins during the campaign shows that although broadcasters gave equal time to representatives of Leave and Remain, the overwhelming majority of politicians interviewed (71.2%) were from the Conservative Party. These results corroborate findings from other research showing that the BBC's reporting on the EU mostly reflected divisions within the Conservative Party among the broader party spectrum (cf. Wahl-Jorgensen et al. Citation2013) and generally tended to give preference to right-of-centre sources over time (Lewis and Cushion Citation2019). Notably, the bias in selecting interviewees was also visible in TV stations’ use of statements from people on the street. In a study of 96 news programmes by major TV channels, 64% of those interviewed spoke in favour of leaving the EU (Tolson Citation2019).

Overall, these findings strengthen the case for further research on the visibility of individual politicians within the news media concerning Brexit. Furthermore, while the general representation of the EU in British media (as well as the associated rise in Euroscepticism) and the referendum campaign itself have received considerable scholarly attention, there is hardly any research on the period after the referendum. Thereby, the results may well differ from the period before the referendum: After the campaign split the country, parties, and the Cabinet alike, the focus moved away from the campaign organizations and back into the parliamentary arena, providing a new context for reporting on Brexit.

Expectations about visibility bias in Brexit newspaper reporting

Visibility bias

The visibility of individual politicians is a necessity for fair democratic political competition. Thereby, the selection of specific individuals as ‘opportune witnesses’ is not only a means to express different editorial positions, but also has important consequences for political competition. Visibility appears to influence the electoral behaviour of voters (Hopman et al. Citation2010, Oegema and Kleinnijenhuis Citation2000). Hence, our focus and main dependent variable in this study is the visibility bias in the mentioning of British MPs in national newspapers. Thereby, visibility refers to the relative amount of news coverage a political actor receives (Eberl et al. Citation2017). With this measure we follow the logic of Groseclose and Milyo (Citation2005), who use the citation of ideologically oriented think-tanks to identify the ideological orientation of US newspapers that mention the think-tanks, thus providing cues to readers.

Empirically, we focus on whether an MP is mentioned in a newspaper article. Such mentions might occur in the form of a citation, by paraphrasing an MP or reporting on their actions. Therefore, visibility is independent of tonality – mentions may have a positive, a neutral or a negative tone. However, visibility is the precondition for any message to reach the public. A poignant example is The Guardian journalist Marina Hyde, who regularly mentions Jacob-Rees Mogg as an example of a pro-Brexit MP with whom she strongly disagrees. However, in doing so, she implicitly provides a platform for Rees-Mogg and makes his views visible to the readership.

To assess balance in the visibility of a particular party, we compare it to their electoral strength as an indicator of their political power (Hopman et al. Citation2011a). Specifically, we use the vote and seat share of the 2017 election as a reference point. In a balanced situation, if a party receives 20% of the seat share, it should receive roughly 20% of the mentions – if the latter deviates strongly from the former, we observe biased reporting. For the individual MP, it makes less sense to use their respective electoral strength since this is based on different district-specific competitions. As an alternative, we differentiate between front- and backbenchers as we explicate below.

Expectations about the occurrence of visibility bias

Brexit challenges the traditional pattern of two-party politics in the UK. The Brexit vote split the country right in the middle, cutting across party lines and the traditional left-right cleavage (Ford and Goodwin Citation2017; Hobolt et al. Citation2020). This situation poses a problem for the adversarial model of decision-making, for voting patterns in the House of Commons, and ultimately for the stability of the government. We begin to develop our expectations on the occurrence of bias with reference to the traditional left-right dimension that has influenced both British politics and news reporting in British newspapers. As Brexit has also led to a strengthening of sub-groups within parties – e.g. the European Research Group (ERG) and Leave Means Leave (LML) – and the appearance of cross party groups such as the People's Vote Campaign (PVC), we also formulate expectations on how these groups may amplify visibility bias in reporting.

Ideological orientations: The division of voter preferences regarding Brexit – as expressed by the 2016 referendum and the narrow victory of the Leave campaign – is mirrored by the positions of political parties and their MPs. provides parties’ Brexit positions in 2019, and MPs vote intentions in 2016. In their official 2019 position, parties were almost evenly split between Leave and Remain – the government majority of Conservatives and DUP continued to back Leave, while all other parties except Labour unequivocally backed Remain. Notably, the positions of Conservative and Labour stand in stark contrast to their MPs’ declared vote intentions in the 2016 referendum – 56% of Conservative MPs and 95% of Labour MPs pledged to vote for Remain or did not declare themselves. These positions, however, only cover two data points. Especially the two large parties were not unified in their position or and they were intentionally ambiguous due to their internal divisions. These intra-party conflicts were prominently brought to the fore in early 2019. After Parliament's repeated failure to pass the withdrawal agreement negotiated by Theresa May (BBC Citation2019), a series of indicative votes highlighted that there was no majority for any of the proposed options (Aidt, Grey and Savu Citation2019). A peculiarity that is consistent with the strength of this division is the short-lived group Change UK. It was founded in February 2019 by Remain defectors from the Conservatives and the Labour Party but disappeared after the 2019 election.

Table 1. Party positions on Brexit.

Newspaper editors faced a situation where party affiliations did not necessarily coincide with official party positions. In such situations news routines and news values usually provide newspapers with a set of informal rules that ensure manageability of news production (Shoemaker and Reese Citation2014). Hence, visibility patterns should mirror these routines and news values to some degree. Nevertheless, journalists cannot be completely neutral commentators of political processes (Entman Citation2010) and British newspapers exhibit clear partisan entrenchments (2006). Therefore, news routines, as well as differences between newspapers and actor groups, may lead to systematic biases in representations of political parties. In the following, we spell out some expectations about these patterns.

The UK is the prototype of a majoritarian parliamentary system in which one of two main parties typically forms a majority government (Cheibub Citation2007; Budge et al. Citation2001; Lijphart Citation1999; Döring Citation1995), and the other one is the government in waiting. As shown by previous analyses (e.g. Brandenburg Citation2006) the two main parties should control the public debate and the media should treat the main actors equally (c.f. Hopman et al. Citation2011a). In this regard, the debate about Brexit should follow other political debates in Britain.

Expectation 1: The visibility of the two large parties, Conservatives and Labour, is balanced relative to their vote and seat share.

Seymour-Ure (Citation1974) defines parallelism between parties and newspapers by three features: (1) media ownership by political parties, (2) party affiliation of the readers, (3) editorial choices by media outlets. Accordingly, the concept of political parallelism describes the affiliations between the media system and the political system in a country. A high level of political parallelism indicates strong political affiliations within the news media. In contrast, weak organizational connections between the political actors and the media indicate low levels of political parallelism (Hallin and Mancini Citation2007). Content-wise it refers to the degree to which news content reflects the ideological orientations of the political parties (Hallin and Mancini Citation2007).

The British media system is typically associated with a low level of political parallelism, although its press closely mirrors the divisions of party politics: ‘within the limits of the British political spectrum, strong, distinct political orientations are clearly manifested in news content. Strong political orientations are especially characteristic of the tabloid press. But the British quality papers also have distinct political identities’ (Hallin and Mancini Citation2007, 28). Brexit is an issue which partially cross-cuts the traditional left-right cleavage (cf. Budge et al. Citation2001). Nevertheless, the cleavages overlap to some degree. Left-wing newspapers (such as The Independent and The Guardian) are opposed to Brexit, while right-wing newspaper (e.g. Daily Mail or Daily Telegraph) hold more favourable views (Aftab Citation2018). Hence, we expect left-leaning and right-leaning newspapers to differ substantially in their reporting, with left-leaning newspapers providing more space to left-leaning politicians and vice versa.

Expectation 2: Centre-right/right-wing and Leave newspapers mention MPs from the Conservative Party more than their relative vote and seat share, Centre-left/left-wing and Remain newspapers mention MPs from the left-wing and remain-oriented parties more than their relative vote and seat share.

Pressure groups: Orchestrated information campaigns influence media coverage. Shoemaker and Reese (Citation2014) argue that interest groups voice their preferences mostly through the media to influence public opinion and legislation. The strategies for organized groups to get their message into the media are twofold: organized events or press conferences that the media will cover on the one hand, and public relations efforts like press releases on the other. Vonbun-Feldbauer and Matthes (Citation2018) show that online media are particularly keen on covering press events and press releases. In our analysis, we only focus on pressure groups which are strongly linked to MPs as we analyse the influence of groups of MPs on the Brexit debate.

In the context of the Brexit debate, we can identify two main pressure groups on the Leave side. First, there is the European Research Group (ERG), which was founded in 1993 as a platform for Conservative MPs. Second, there is Leave Means Leave (LML). It was founded in 2016 as a general pressure group to ensure a ‘clean Brexit’ (LML Citation2019) and is organized as a cross-party platform open to MPs, party members, and citizens. There is no equivalent organization on the Remain side (Elgot Citation2018) – the All Parliamentary Group on EU Relations (APPG EU) set up in July 2017 and the Peoples Votes Campaign (PVC) launched in April 2018 are the closest counterparts. While the APPG EU only consisted of six publicly known MPs and showed little activity, the PVC had a broad membership of individual MPs and party groups.

Expectation 3: Politicians who are engaged in well-organized pressure groups are mentioned more frequently than non-organized MPs.

Beyond expectations about the political balance of the visibility, there are two further institutional and news values aspects for which we control in our analysis: First, potential differences between offline and online editions, and second, differences between frontbenchers and backbenchers.

Online vs offline editions: Although online news can react immediately and deliver up-to-the-minute information, communication research has shown that online and print editions of newspapers do not vary significantly concerning content (Shoemaker and Reese Citation2014; Vonbun-Feldbauer and Matthes Citation2018). However, we still control for possible differences.

Frontbenchers vs backbenchers: Journalists are more likely to choose news stories when they feature prominent actors (Shoemaker and Reese Citation2014). Thus, we expect politicians with an important position to be more visible. Specifically, we expect that senior government members should be mentioned more frequently. The same should hold for important Shadow Cabinet positions and members with important parliamentary functions. Hence, we control for effects of frontbench vs backbench.

Data and methods

Period of analysis

We analyse the Brexit debate between 1 July 2017 and 29 March 2019. This period was chosen for two reasons: First, the period starts just after Theresa May was able to form a government based on a confidence and supply arrangement with the Northern Irish DUP (Cabinet Office Citation2019). The agreement was formally signed on 16 June 2017. The Cabinet was relatively stable during this period – even though there were some prominent defections and changes in ministerial roles, no major cabinet reshuffles took place. Second, the one key task of the House of Commons and of the May government was to agree on a withdrawal agreement with the European Union before the original exit date on 29 March 2019. This is different from the referendum campaign in 2016, where numerous non-parliamentary actors were involved (Levy et al. Citation2016). In the post-referendum period, we can focus on the MPs as a consistent set of parliamentary actors.

Newspaper data and the creation of the corpus

We relied on the LexisNexis Academic online database to access the major UK newspapers. Our aim was to cover the political spectrum from left to right as well as newspapers with declared pro-Brexit and anti-Brexit positions. Therefore, we selected a mix of broadsheets and tabloids, both in their print (weekly and Sunday) and online editions (see ). We focused on national editions only and did not cover regional and regionalized newspapers (e.g. the Scottish edition of the Daily Mail).

Table 2. Newspapers in the analysis and their main characteristics.

Unfortunately, articles from The Guardian online as well as offline articles from the two selected tabloids (Daily Mirror and Daily Mail) were unavailable and could not be included in the analysis. Furthermore, since 2016 The Independent has been an online-only newspaper. We were also not able to include the Sun as a very prominent tabloid, as it was not available in the database. For reasons of consistency and comparability of data sources, we opted to stick to the database and not mix the data with other sources. The selection of papers leads to a slight pro-Brexit and right/centre-right tendency, which however reflects the British newspaper market as a whole. Furthermore, the average reach of newspapers and their respective online presences is still largely comparable. We present the results from separate analyses for each newspaper to account for this feature of the data.

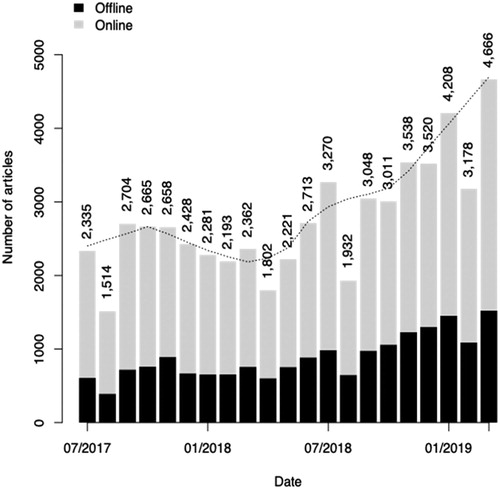

For these newspapers, we first selected all articles containing the expression ‘Brexit’. We then excluded all articles which were not published in sections broadly associated with politics (e.g. culture or sports). The resulting dataset contains 58,247 articles. The expression ‘Brexit’ is a valid and consistent term for our search of Brexit-related articles. We also searched for the terms ‘leave the EU’, ‘leave the European Union’, ‘remain in the EU’, ‘remain in the European Union’, ‘EU referendum’, ‘European Union referendum’ when articles did not contain the term ‘Brexit’. For the print editions of the Guardian and Observer, we lose 3% of articles by not including these terms in our corpus, for Times and Sunday Times 16%, Daily Telegraph and Sunday Telegraph 6%, for the online editions of the newspapers 5% or below. The number of Brexit articles across newspapers is displayed in ; presents the number of articles containing the term ‘Brexit’ for the period July 2017 to March 2019, showing a steady increase starting in the spring of 2018.

Measurement decisions for the dependent and independent variables

The variable of interest is the frequency of individual MP mentions, i.e. number of articles mentioning an MP at least once. The basic assumption for our measurement strategy is that the more frequently an MP or an issue was mentioned, the more visible and the more relevant they were for a debate – even if a journalist did not share the preferences of the MP. To identify the individual MPs in our corpus of newspaper articles, we automatically searched for the MPs’ full names in the articles. This resulted in an article-by-MP matrix, where each cell indicates whether an MP was mentioned in an article at least once (1) or not (0). As we did not count the repetition of an MPs name within the article, the precondition of the validity of our search strategy was that MPs are mentioned at least once with their full name in an article. To support the validity of this measurement strategy, we also tested alternative strategies.Footnote1

We used a binary indicator rather than a count variable for each article, as we believe that this provides a better measure of the overall visibility of MPs when summing up mentions over all articles in the subsequent analysis. It is reasonable to assume that readers are more likely to recognize MPs whom ten articles mention once each than those who are mentioned ten times in just one article. We also refrain from more elaborate coding strategies that might have weighted the counts with features such as the length of an article, or the placement of a name within an article – such efforts would only marginally impact upon the general patterns, while introducing more measurement errors.

For the analysis, we sum up the number of articles in which an MP was mentioned to get a sense of their overall visibility. Overall, we focus on descriptive statistics instead of estimating a statistical model in order to highlight trends and patterns in the data. We acknowledge that this analytical strategy comes at the expense of disregarding potential interactions between the factors that we study in this paper. Depending on the specific research interest, the counts are aggregated at the level of specific newspapers or the level of all articles. For instance, a value of approximately 30,000 for Theresa May in the entire corpus of roughly 58,000 articles means that the former prime minister was mentioned in approximately every other article on Brexit in the period under investigation.

A peculiarity in our data is the party assignment for Change UK, which was only founded in February 2019. To highlight the patterns for members of this group, we assigned the relevant MPs to this group for the entire research period, even though the defections occurred rather late in our period of analysis.

Furthermore, our narrow definition of the frontbench only includes the PM, senior Cabinet members (i.e. secretaries of state and the Minister for the Cabinet Office) and the leader of the House of Commons for the Conservative Party, and all equivalent posts in the Shadow Cabinet for the Labour Party; for other parties, we only code party leaders or Westminster leaders as frontbenchers. We also coded MPs as frontbench if they did not hold a frontbench position for the entire period of analysis, but only for a shorter time. As a result, we define 9.6% Conservative MPs, 15.2% of Labour Party MPs and 4.5% of MPs from other parties as frontbenchers.

Leave Means Leave consisted of 41 MPs at the end of March 2019 (36 Conservatives, 3 DUP, 1 Labour, 1 Independent). The ‘People's Vote’ Campaign (PVC) was supported by the Liberal Democrats, the Green Party, Plaid Cymru, the Scottish National Party, Change UK, Scottish Labour and London Labour plus a number of individual Conservative MPs. There are 121 MPs in our data who supported the PVC (18.7% of all MPs and 18.4% of backbenchers). Leave Means Leave MPs represented 11.5% of the Conservative backbench MPs. The European Research Group consisted of 85 MPs at the end of March 2019, 9 of whom were frontbenchers and 76 of whom were backbenchers. That means the ERG represented 27.1% of the Conservative backbench MPs. There was, however, an overlap between the two groups of 27 members. We retrieved information on group memberships from the relevant Wikipedia articles in their versions from April 2019. To the extent that membership in these groups is not formalized and public, the coding only provides an approximate sense of the membership, and the results have to be interpreted with caution.

Visibility patterns in Brexit reporting

We analyse the visibility patterns of MPs in five steps. First, we look at the visibility of parties across all newspapers in comparison to parties’ vote shares in the 2017 general election and the seat share in the House of Commons in March 2019. Second, we distinguish between left-wing and right-wing newspapers. Third, we analyse the influence of special interest pressure groups. Fourth, we consider the influence of frontbench positions on visibility. Finally, we look at the individual MPs dominating the debate within these groups.

Visibility across parties

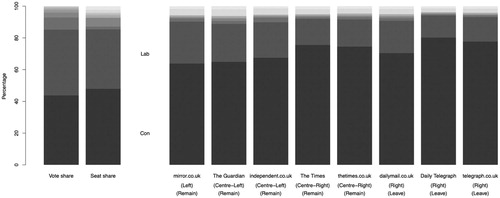

In the first step, we look at the parties in the House of Commons across all newspapers. We base this analysis on all MPs, including those with major government roles. We include offline and online mentions in newspapers which offer both (i.e. Times/Sunday Times and Daily/Sunday Telegraph). We also show the percentage of votes the parties received in 2017 as well the seats the parties held after the vote in July 2017, and in March 2019. These results are shown in .

Table 3. Vote and seat share. Visibility 2017–2019 (absolute and relative; print and online editions).

The debate almost exclusively focused on MPs from the Conservative Party. Even though only 48.0% of the MPs were Conservative, representing 43.9% of voters, 70.9% of MPs mentioned across all newspapers were Conservative. This is a remarkable difference in the representation of voters between their voting behaviour and newspaper reporting. In contrast, Labour as the principal opposition party was clearly underrepresented. Although it controlled 37.5% of MPs and received 41.4% of the popular vote in 2017, only 20.1% of mentions were for Labour MPs. Smaller parties were likewise under-represented. They received a combined vote share of 14.7% and held 14.5% of seats but their mention share was only 9%.

In sum, opinions within the Conservative Party dominated the newspaper debate about Brexit during our period of observation. Any other party, and especially Labour as the main opposition party, were just a side-show. However, as our newspaper sample exhibits a tendency towards centre-right and pro-Brexit papers (like the majority of the British national newspaper market), it is necessary to conduct the analysis separately for each newspaper as the general expectation is that right-wing papers mention right-wing MPs more often, which might explain the above results.

Visibility across left and right newspapers

In a second step, we distinguish between newspaper outlets based on political orientation (left-wing vs right-wing newspapers) and mode of publication (online and offline). Once again, we include the vote shares in 2017 and the seat shares in 2019 as a point of reference.

shows that there is some difference between the newspapers from left to right. An ANOVA test on each party's sum of MP mentions relative to the number of newspaper articles confirms that there is a significant difference between the newspapers. At first glance, there is some difference between left-leaning and right-leaning newspapers, whereby left-of-centre MPs featured more frequently in left-wing news outlets and vice versa. At the same time, we note a difference between vote and seat shares and the distribution of mentions in all newspapers. Across all papers, the debate was dominated by Conservative MPs, even in left-wing or centrist papers such as The Guardian. While 80.3% of the mentions in the Daily Telegraph and 75.6% in The Times were of Conservative MPs, even in papers such as the Mirror or The Guardian this value was still about two thirds, compared with a vote and seat share well below that. Labour had a seat share of 37.5% and a vote share of 41.4%, but even in the left papers such as the Mirror and the Guardian, the mentions did not exceed 23.0%, and 21.8%, respectively. This means that in all newspapers the debate about Brexit was mainly a debate within the Conservative Party; other parties only played a minor role. A further interesting finding is that there is little difference between online and offline editions (cf. Shoemaker and Reese Citation2014; Vonbun-Feldbauer and Matthes Citation2018).

Figure 2. Vote share (2017), seat share (2019), newspaper visibility in per cent.

Note: The horizontal order of the bars follows the ideological leanings of the news outlets. The ideological orientation and the Brexit position is provided in parentheses. The bars are stacked in the following order: Conservatives, Labour, Liberal Democrats, Scottish National Party, Green Party, Democratic Unionist Party, Sinn Fein, Plaid Cymru, Change UK, Independent/Other. For the data values, see Appendix, .

Visibility of special groups

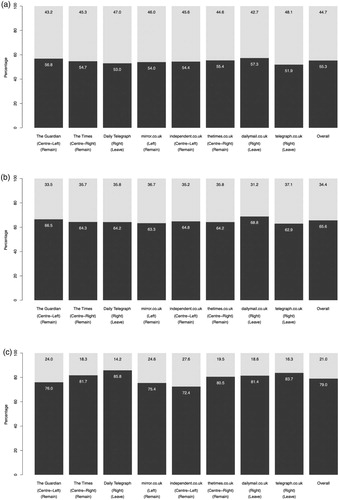

Among organized pressure groups with a strong parliamentary base, we focus on the European Research Group (ERG), Leave Means Leave (LML) and the People's Vote Campaign (PVC).Footnote2

Turning to the organized groups within the Conservative Party, we find that, to a large extent, the hardcore Brexiters of the ERG (see a) and LML (see b) controlled the debate. Compared with other Conservative backbenchers, members of these groups were overrepresented by a factor of 1.6 (ERG) and 3.0 (LML), respectively. 27.1% of the Conservative backbenchers were ERG members, yet they were responsible for no less than 44.7% of the mentions of Conservative backbenchers in the newspapers. Again, there is almost no variation between newspapers, whether from the left or the right. The situation is even more pronounced for LML members. A membership of 11.5% among Conservative backbench MPs constituted 34.4% of all mentions in the newspapers.

c shows the visibility of the People's Vote Campaign compared to all backbenchers. We find that the influence of the PVC was on par with their numerical strength – 18.4% of MPs could be attributed to the PVC and were responsible for 21.0% of mentions in the newspapers. In this case, we also observe a more notable difference between newspapers from the left and those from the right, whereby pro-Brexit newspapers afforded the People's Vote Campaign with slightly less room.

Figure 3. (a) Conservative visibility. European Research Group in light grey, all other Conservative backbenchers in dark grey (backbenchers only). (b) Conservative visibility. Leave Means leave in light grey, all other Conservative backbenchers in dark grey (backbenchers only). (c) Visibility of the People's Vote Campaign. Peoples Vote in light grey, all other MPs in dark grey (backbenchers only).

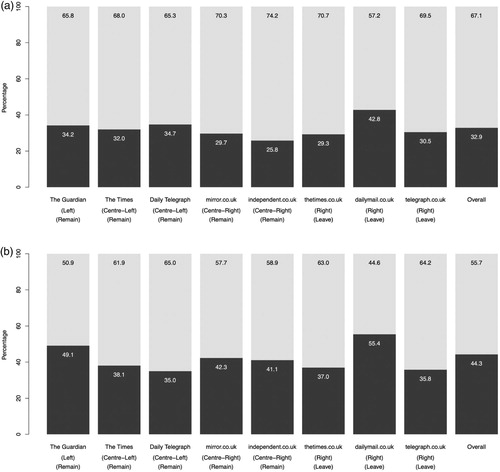

Visibility by roles: frontbenchers vs backbenchers

From the structure of the political system, we expect frontbenchers – and especially members of the government – to be mentioned more frequently in news articles. In the following, we test this expectation, but also check whether the patterns we described in the previous sections remain stable when focusing on backbenchers only. To this end, we differentiate between frontbench and backbench functions among majority and minority parties. compares the visibility of frontbenchers and backbenchers for the Conservatives (a) and Labour (b). As expected, frontbenchers were far more visible than backbenchers, especially for the Conservatives as the governing party. The reporting in online and offline editions was almost equally distributed between frontbenchers and backbenchers for both parties. The Daily Mail presents a slight exception here as it provided backbenchers with greater visibility than other news outlets.

Figure 4. (a) Conservative visibility. Frontbenchers in light grey, backbenchers in dark grey. (b) Labour visibility. Frontbenchers in light grey, backbenchers in dark grey.

When we remove the frontbenchers (see Appendix, Tables A2 and A3), the visibility across parties changes: Mentions of the Conservatives drop by 13.0 points, whereas Labour increases by 2.5 points. The share of Change UK increases notably by 5.4 points. The pattern is similar for offline and online newspapers. While the visibility of the Conservatives drops, the data still indicate that the overrepresentation of the Conservatives in the Brexit debate was not a mere function of their majority status. Even after excluding members of government and members of the Shadow Cabinet, the debate was still dominated by the Conservative Party, underlining our earlier proposition that the Brexit debate in the post-referendum phase heavily focused on an intra-party debate.

Visibility of individual MPs

So far, we have discussed which parties and intra-party groups were particularly influential in the debate. Beyond collective visibility patterns, we now turn to the question of whether specific MPs dominated the debate within the respective groups. To this end, we first look at the distribution of individual mentions before turning to the influence of the most important MPs.

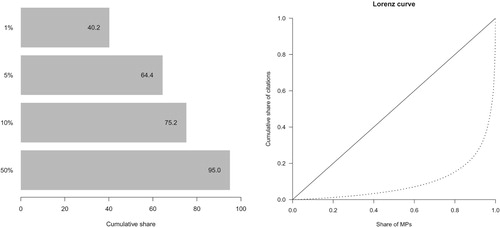

The main finding from a first look at the comprehensive data is that only a fraction of the MPs dominated the Brexit debate. We draw this conclusion by looking at the percentiles and their cumulative mention share (a). The top 1% of MPs are responsible for two fifths (40.2%) of all mentions. The top 5% produce almost two thirds (64.4%). The top 10% generate three fourths (75.2%) and the top 50% no less than 95% of mentions. Another way of looking at these disparities is the Lorenz curve (b), which displays the empirical deviation from a fair distribution, where 20% of the MPs would receive 20% of the mentions.

Figure 5. Share of MPs with shares of mentions across all newspapers (a, left) and Lorenz curve (b, right).

The descriptive analysis of the visibility patterns for the different cabinet and shadow cabinet roles, backbenchers and parties provides a more nuanced perspective on the variance within these groups (). Hereby, the distribution of mentions for all MPs provides a fitting first overview. It is no wonder that Theresa May as Prime Minister was mentioned most often with mentions in 30,479 articles. The average MP was mentioned in 289.6 articles, whereas the median MP received mentions in only 52 articles. The considerable difference between average and median indicates that the distribution is skewed, and that only few MPs were mentioned frequently. In contrast, many MPs were hardly mentioned at all. The standard deviation of 1,447.8 article mentions further highlights this chasm.

Table 4. Maximum, mean, standard deviation, median, minimum for all, with/without functions, Conservatives, Labour, and all other parties.

Turning to different groups of MPs, we find that even within the group of senior government members, there were considerable differences in visibility, ranging from a maximum of 30,479 articles (Theresa May) to a minimum of just 32 (Matthew Hancock). The same is true for shadow cabinet roles and backbenchers. Second, there were notable differences between the parties. We have already pointed to some of these differences at the aggregate level. However, these patterns are now also confirmed at the individual level. The differences between the maxima of the parties on the one hand and the median on the other are striking. The maximum for the Conservatives (T. May) is three times that of Labour (J. Corbyn), and the most prominent Conservative backbencher (J. Rees-Mogg) is mentioned still half as often as the leader of the opposition. The maxima of the smaller parties trail far behind those of the large parties: This is particularly surprising for the DUP as the backstop for Northern Ireland was the main sticking point in the entire debate.

As few MPs dominated the debate, it is insightful to consider who these influential actors were. Consequently, we provide a list of the ten most frequently mentioned MPs for all newspapers as well as for each major party represented in Parliament (). One can draw four lessons from this overview: (1) As expected, Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn top the list; other MPs with high numbers of articles mentioning them are typically senior cabinet members. (2) Jeremy Corbyn is the only non-Conservative politician who appears in the overall top 10. (3) Jacob Rees-Mogg is the only frequently mentioned backbencher who – unlike David Davis, Boris Johnson, or Amber Rudd – never held a high parliamentary or governmental office during our period of observation. (4) With the notable exception of Amber Rudd and Philip Hammond, the Conservative members on the list all hold pro-Brexit views. These results are reasonably consistent across all newspapers, online and offline (not shown here).

Table 5. Ten most mentioned MPs (across parties and all newspapers and declared vote intention).

The analysis of patterns in the Top Ten list () across parties shows that the Conservative list looks similar to the overall list minus Jeremy Corbyn. As could be expected, members of the Shadow Cabinet or MPs who at least temporarily held these positions fill the Labour list. In line with the above findings, the absolute number of article mentions shows the considerable differences between the Conservative Party and other parties on the individual level. The lowest ranking list member of the Conservative Party, Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt, received more absolute mentions than any non-Conservative member on the list except for Jeremy Corbyn. From the smaller parties, only Vince Cable as leader of the Liberal Democrats, and Anna Soubry and Chukka Umunna as prominent defectors to Change UK make it into the quadruple-digit mentions at all. Before they left their respective parties, they were the most prominent remain-oriented MPs in their parties. All other MPs from the smaller parties are in the area of 500 mentions and below. Notably, MPs who rose prominence in the House of Commons while taking control of the decision-making process, such as Hilary Benn (791), Yvette Cooper (1,475), Dominic Grieve (1,860), Oliver Letwin (866) and Caroline Spelman (252) are far behind MPs from the ERG and LML.

As we have seen in section 5.4., members in frontbench positions were more likely to be mentioned. Therefore, it is worthwhile to look at the Top Ten list for backbenchers as we do in . Again, we see a strong bias in favour of Conservative MPs. Jacob Rees-Mogg is leading the list, and six MPs make it to the four digit-level, while only Yvette Cooper from Labour reaches a four-digit level. Within the Conservatives, the Leave MPs were mentioned more frequently than the Remain MPs. This effect is only countered by the visibility of the Change UK MPs where at least Anna Soubry (ex-Conservative) and Chukka Umunna (ex-Labour) reach the four-digit level.

Table 6. Ten most mentioned backbench MPs (across parties and all newspapers and declared vote intention).

Conclusion

This article has investigated bias in newspaper reporting on Brexit between the snap election in 2017 and the original Brexit date in March 2019, i.e. the period of the most intense negotiations between the UK and the EU over Britain's exit from the European Union. Specifically, it examined whether newspaper reporting in this period was biased toward a strong focus on a few parties or MPs regarding visibility. For this purpose, we analysed how frequently articles about Brexit in print and online editions of major newspapers mentioned individual MPs. In total, our analysis covered 58,247 newspaper articles in eight newspapers across the political spectrum (left-centre-right), the Brexit divide (Remain vs Leave) different target groups (broadsheets vs tabloids) and different publication venues (print vs online).

The central result of our analysis is that newspaper coverage of MPs was neither descriptively nor substantively representative of the opinion of the population. Thus, our main findings go against the expectation that the range of existing positions is represented fairly and equally in the newspapers. In particular: (1) The debate was heavily focused on MPs from the Conservative Party with a share of 70.9% of mentions. In stark contrast, Labour was under-represented in the debate – despite a vote share of 41.4% in the 2017 election, their MPs attracted only 20.1% of mentions during our period of observations. Incumbency effects in media coverage have also been found in other studies of media attention (e.g. Hopmann et al. Citation2011b; Larcinese and Sircar Citation2017). However, these effects are usually minimized when the opposition addresses topics that are already important to the government (Meyer, Haselmeyer and Wagner Citation2020) or when the amount of negative coverage increases (Green-Pedersen, Mortensen and Thesen Citation2017) – both of which would theoretically also apply to the Brexit debate. (2) Members of organized pro-Brexit groups such as the European Research Group and Leave Means Leave were strongly overrepresented. The ERG MPs were mentioned about 1.6 times as frequently as other Conservative backbenchers, and Leave Means Leave MPs were overrepresented by a factor of 3. On the Remain side, however, supporters of the People's Vote campaign were not over-represented. Overall, this seems to reflect Mancur Olson's (Citation1965) argument that small groups with concentrated benefits are better able to organize. To put it explicitly: the world in the newspapers is a very different one than the world in Parliament. The majority of Remain-oriented MPs and MPs who supported a soft Brexit were not mentioned with adequate frequency. The paper also looked at the individual MPs and their visibility, revealing wide variation evidently driven by the divide between backbenchers and frontbenchers. Surprisingly, even within these groups, there were extreme differences. The entire national debate centred on a handful of MPs. The top 1% of MPs were responsible for 40% of all mentions, while the bottom 50% produced only 5% of all mentions.

In conclusion, there was a clear overrepresentation of Conservative and pro-Brexit positions in British newspapers. Furthermore, extreme right opinions were overrepresented within the pro-Brexit camp. These results mean that if studies on the effects of mass media on public opinion formation are correct, and mass media can influence public opinion (Zaller Citation1996, Bartels Citation1993, Broockman and Kalla Citation2016, Baum Citation2002), British newspapers played a crucial part in ensuring the acceptance of a hard Brexit in the British population by over-representing hard Brexit MPs in their coverage. In this sense, it is the culmination of an increase in Euroscepticism in the British media over the years (e.g. Copeland and Copsey Citation2017). The content of the British newspapers also has implications for broadcast media as TV and radio feel comfortable taking up newspaper headlines (Cushion et al. Citation2018).

Our findings are reasonably stable across the left-right divide in British newspapers, nor does it matter whether we study print or online editions. The observed patterns also change little if we focus on backbenchers. While we find slight tendencies of left-wing Remain newspapers preferring Remain and Labour MPs more, they were still under-represented there. Although one might expect the Daily Mail or the Daily Telegraph to focus their attention on Conservative pro-Brexit MPs, surprisingly, left-wing Remain oriented newspapers such as the Mirror and the Guardian behaved similarly.

One natural caveat of our analysis is that we did not analyse the tonality of the coverage. Previous studies have focused on the tonality, but have come to similar conclusions: The media reporting was more positive towards the Leave campaign than towards Remain (Levy, Aslan and Bironzo Citation2016, Firmstone Citation2016, Muhammad Citation2018, Walter Citation2019, Aftab Citation2018). While the pro-Brexit bias of newspapers is typically attributed to media ownership structures in the UK, the analysis of mentioning patterns on the individual level also allows for a deeper analysis of the reasons why some MPs are mentioned more often than others in future works.

Our findings may have implications for the further process of the separation of the UK from the European Union, and, in the long run, for the UK as a whole. First, we may reasonably assume that extreme opinions will continue to occupy the most dominant position in the newspapers in the near future. This will inevitably have implications for the type of future relationship on which the UK and the EU will eventually agree. It may also have consequences for the debate within the UK. In contrast to England, both Scotland and Northern Ireland voted Remain. In this study, we did not investigate Scottish or the other local newspapers (e.g. the Herald, the Scotsman), but only nation-wide newspapers published for a primarily English audience. It is an open question whether the local non-English papers reported the Brexit-debate differently from the national newspapers. If the citizens outside of England are exposed to another picture of the debate, and the current debate at the national level continues to be driven mainly by the extreme pro-Brexit actors, this might indeed question the future of a unified UK.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and also the participants of the conference Advances in the Empirical and Theoretical Study of Parliaments organized by the ECPR Standing Group Parliaments in September 2019, as well as the participants of the Norddeutsches Kolloquium Sozialwissenschaften in July 2019 and January 2020. We would especially like to thank our student assistants Virginia Bergholz, Jule Kegel, Carolin Luksche and Felix Münchow for research support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 For example, ‘Anna Soubry’ is mentioned in 2,304 articles. ‘Mrs. Soubry’ in none, ‘Mrs Soubry’ in 10, ‘MP Soubry’ in 1, ‘Mrs Soubry’ or ‘MP Soubry’ but not ‘Anna Soubry’ in only 5. Therefore the error percentage is 0.2%. ‘Jacob Rees-Mogg’ is mentioned 6,252 times. ‘Mr. Rees-Mogg’ in 10, ‘Mr Rees-Mogg’ in 1,171 articles and ‘MP Rees-Mogg’ in 1. One of the latter three terms but not ‘Jacob Rees-Mogg’ in 70 cases. Therefore the error percentage is 1.1%. Similar error percentages can be identified for other MPs. Additionally, we manually checked a random sample of newspaper articles (N = 426) on whether the full name of an MP (e.g. Jacob Rees-Mogg) was mentioned at least once or whether an acronym or something else but not the full name was used. In more than half of the articles, the full name of an MP was mentioned at least once.

2 The ERG / European Research Group was explicitly mentioned 3,653 times in our data, LML / Leave Means Leave only 42 times and the Leave Campaign in general 2,055 times. The APPG on EU Relations 3 times (146 times when adding all hits for APPG and All Parliamentary Group) and People's Vote 2,052 times.

References

- Adam, S., B. Eugster, E. Antl-Wittenberg, R. Azrout, J. Möller, C. de Vreese, M. Maier, and S. Kritzinger. 2019. “News Media’s Position-Taking Regarding the European Union: the Synchronization of Mass Media’s Reporting and Commentating in the 2014 European Parliament Elections.” Journal of European Public Policy 26 (1): 44–62. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2017.1375546

- Aftab, S. A. 2018. “Brexit Referendum and Media Coverage. An Appraisal.” Journal of European Studies 34 (1): 68–81.

- Aidt, T., F. Grey, and A. Savu. 2019. “The Meaningful Votes: Voting on Brexit in the British House of Commons.” Public Choice. doi: 10.1007/s11127-019-00762-9

- Bartels, L. M. 1993. “Messages Received: The Political Impact of Media Exposure.” American Political Science Review 87 (2): 267–285. doi: 10.2307/2939040

- Baum, M. A. 2002. “Sex, Lies, and War: How Soft News Brings Foreign Policy to the Inattentive Public.” American Political Science Review 96 (1): 91–109. doi: 10.1017/S0003055402004252

- BBC. 2019. “Brexit: MPs reject Theresa May’s deal for a second time.” BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-47547887.

- Berkel, B. 2006. “Political Parallelism in News and Commentaries on the Haider Conflict: A Comparative Analysis of Austrian, British, German, and French Quality Newspapers.” Communications 31 (1): 85–104. doi: 10.1515/COMMUN.2006.006

- Brandenburg, H. 2005. “Political Bias in the Irish Media: A Quantitative Study of Campaign Coverage During the 2002 General Election.” Irish Political Studies 20 (3): 297–322. doi: 10.1080/07907180500359350

- Brandenburg, H. 2006. “Party Strategy and Media Bias: A Quantitative Analysis of the 2005 UK Election Campaign.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 16 (2): 157–178. doi: 10.1080/13689880600716027

- Broockman, D. E., and J. L. Kalla. 2016. “Durably Reducing Transphobia: A Field Experiment on Door-to-Door Canvassing.” Science 352 (6282): 220–224. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9713

- Budge, I., H.-D. Klingemann, A. Volkens, J. Bara, et al. 2001. Mapping Policy Preferences. Estimates for Parties, Electors, and Governments, 1945–1998. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cabinet Office. 2019. “Confidence and Supply Agreement between the Conservative and Unionist Party and the Democratic Unionist Party.” https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/conservative-and-dup-agreement-and-uk-government-financial-support-for-northern-ireland/agreement-between-the-conservative-and-unionist-party-and-the-democratic-unionist-party-on-support-for-the-government-in-par.

- Carey, S., and J. Burton. 2004. “Research Note: The Influence of the Press in Shaping Public Opinion Towards the European Union in Britain.” Political Studies 52 (3): 623–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2004.00499.x

- Cheibub, J. A. 2007. Presidentialism, Parliamentarism, and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Copeland, P., and N. Copsey. 2017. “Rethinking Britain and the European Union: Politicians, the Media and Public Opinion Reconsidered.” Journal of Common Market Studies 55 (4): 709–726. doi: 10.1111/jcms.12527

- Cushion, S., A. Kilby, R. Thomas, M. Morani, and R. Sambrook. 2018. “Newspapers, Impartiality and Television News.” Journalism Studies 19 (2): 162–181. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2016.1171163

- Cushion, S., and J. Lewis. 2017. “Impartiality, Statistical tit-for-Tats and the Construction of Balance: UK Television News Reporting of the 2016 EU Referendum Campaign.” European Journal of Communication 32 (3): 208–223. doi: 10.1177/0267323117695736

- Daddow, O. 2012. “The UK Media and ‘Europe’: From Permissive Consensus to Destructive Dissent.” International Affairs 88 (6): 1219–1236. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2346.2012.01129.x

- D’Alessio, D., and M. Allen. 2000. “Media Bias in Presidential Elections: a Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Communication 50 (4): 133–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02866.x

- Deacon, D., D. Wring, E. Harmer, J. Downey, et al. 2016. “Hard Evidence: Analysis Shows Extent of Press Bias towards Brexit Hard Evidence: Analysis Shows Extent of Press Bias towards Brexit.” University of Loughborough. The Conversation (16th June 2016). https://theconversation.com/hard-evidence-analysis- shows-extent-of-press-bias-towards-brexit-61106.

- Döring, H. 1995. “Time as a Scarce Resource: Governmental Control of the Agenda.” In Parliaments and Majority Rule in Western Europe, edited by H. Döring, 223–247. Frankfurt (Main): Campus.

- Eberl, J. M., H. G. Boomgaarden, and M. Wagner. 2017. “One Bias Fits All? Three Types of Media Bias and Their Effects on Party Preferences.” Communication Research 44 (8): 1125–1148. doi: 10.1177/0093650215614364

- Eilders, C. 1999. “Synchronization of Issue Agendas in News and Editorials of the Prestige Press in Germany.” Communications 24 (3): 301–328. doi: 10.1515/comm.1999.24.3.301

- Eilders, C. 2002. “Conflict and Consonance in Media Opinion: Political Positions of Five German Quality Newspapers.” European Journal of Communication 17 (1): 25–63. doi: 10.1177/0267323102017001606

- Eilders, C., F. Neidhardt, and B. Pfetsch. 2004. Die Stimme Der Medien: Pressekommentare Und Politische Öffentlichkeit in Der Bundesrepublik. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Elgot, J. 2018. “Pro remain Tory MPs will form Group to Vote Down May’s Brexit deal.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/oct/10/pro-remain-tory-mps-will-form-group-vote-down-may-brexit-deal.

- Entman, R. M. 2010. “Media Framing Biases and Political Power: Explaining Slant in News of Campaign 2008.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 11 (4): 389–408. doi: 10.1177/1464884910367587

- Firmstone, J. 2016. “Newspapers’ Editorial Opinions During the Referendum Campaign.” In EU Referendum Analysis 2016: Media, Voters and the Campaign, edited by D. Jackson, E. Thorsen, and D. Wring. Bournemouth University – The Centre for the Study of Journalism, Culture and Community. www.referendumanalysis.eu.

- Foos, F., and D. Bischof. 2019. “Tabloid Boycott Decreases Euroscepticism.” Working Paper, 17 November 2019. http://www.florianfoos.net/resources/Foos_Bischof_Hillsborough_APSA.pdf.

- Ford, R., and M. Goodwin. 2017. “Britain After Brexit: A Nation Divided.” Journal of Democracy 28 (1): 17–30. doi: 10.1353/jod.2017.0002

- Forster, A. 2002. Euroscepticism in Contemporary British Politics: Opposition to Europe in the British Conservative and Labour Parties Since 1945. London: Routledge.

- Geddes, A. 2004. The European Union and British Politics. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gentzkow, M., and J. M. Shapiro. 2006. “Media Bias and Reputation.” Journal of Political Economy 114 (2): 280–316. doi: 10.1086/499414

- Gowland, D. 2017. Britain and the European Union. London: Routledge.

- Green-Pedersen, C., P. B. Mortensen, and G. Thesen. 2017. “News Tone and the Government in the News: When and Why Do Government Actors Appear in the News?” In How Political Actors Use the Media, edited by P. V. Aelst, and S. Walgrave, 207–223. Cham: Palgrave.

- Groeling, T. 2008. “Who’s the Fairest of Them All? An Empirical Test for Partisan Bias on ABC, CBS, NBC, and Fox News.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 38 (4): 631–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-5705.2008.02668.x

- Groseclose, T., and J. Milyo. 2005. “A Measure of Media Bias.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 120 (4): 1191–1237. doi: 10.1162/003355305775097542

- Hagen, L. M. 1993. “Opportune Witnesses: An Analysis of Balance in the Selection of Sources and Arguments in the Leading German Newspapers’ Coverage of the Census Issue.” European Journal of Communication 8 (3): 317–343. doi: 10.1177/0267323193008003004

- Hallin, D. C., and P. Mancini. 2007. “The North Atlantic or Liberal Media Model Countries: Introduction.” In European Media Governance: National and Regional Dimensions, edited by G. Terzis, 27–32. Chicago: intellect.

- Hawkins, B. 2012. “Nation, Separation and Threat: An Analysis of British Media Discourses on the European Union Treaty Reform Process.” Journal of Common Market Studies 50 (4): 561–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5965.2012.02248.x

- Hobolt, S. B., T. J. Leeper, and J. Tilley. 2020. “Divided by the Vote: Affective Polarization in the Wake of Brexit.” British Journal of Political Science In Press.

- Hopmann, D. N., C. H. de Vreese, and E. Albæk. 2011a. “Incumbency Bonus in Election News Coverage Explained: The Logics of Political Power and the Media Market.” Journal of Communication 61 (2): 264–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01540.x

- Hopmann, D. N., P. Van Aelst, and G. Legnante. 2011b. “Political Balance in the News: A Review of Concepts, Operationalizations and key Findings.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 13 (2): 240–257. doi:10.1177/1464884911427804.

- Hopmann, D. N., R. Vliegenthart, C. De Vreese, and E. Albæk. 2010. “Effects of Election News Coverage: How Visibility and Tone Influence Party Choice.” Political Communication 27 (4): 389–405. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2010.516798

- Jackson, D., E. Thorson, and D. Wing. 2016. EU Referendum Analysis 2016: Media, Voters and the Campaign. Bournemouth University – The Centre for the Study of Journalism, Culture and Community.

- Kahn, K. F., and P. J. Kenney. 2002. “The Slant of the News: How Editorial Endorsements Influence Campaign Coverage and Citizens’ Views of Candidates.” American Political Science Review 95 (1): 49–69.

- Kalla, J. L., and D. E. Broockman. 2018. “The Minimal Persuasive Effects of Campaign Contact in General Elections: Evidence From 49 Field Experiments.” American Political Science Review 112 (1): 148–166. doi: 10.1017/S0003055417000363

- Larcinese, V., and I. Sircar. 2017. “Crime and Punishment the British way: Accountability Channels Following the MPs’ Expenses Scandal.” European Journal of Political Economy 47 (1): 75–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2016.12.006

- Levy, D. A., B. Aslan, and D. Bironzo. 2016. UK Press Coverage of the EU Referendum. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/our-research/uk-press-coverage-eu-referendum.

- Lewis, J., and S. Cushion. 2019. “Think Tanks, Television News and Impartiality: The Ideological Balance of Sources in BBC Programming.” Journalism Studies 20 (4): 480–499. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2017.1389295

- Lijphart, A. 1999. Patterns of Democracy. Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-six Countries. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- LML. 2019. Leave Means Leave. Brexit will win in the end. https://www.leavemeansleave.eu.

- Meyer, T. M., M. Haselmayer, and M. Wagner. 2020. “Who Gets Into the Papers? Party Campaign Messages and the Media.” British Journal of Political Science 50 (1): 281–302. doi: 10.1017/S0007123417000400

- Muhammad, I. 2018. Media Coverage of the Role of Big Data in the 2016 Brexit Referendum. An Analysis of The Guardian and The Telegraph Coverage Using Social Responsibility Theory. Tallinn: School of Governance, Law and Society. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322928023.

- Mutz, D. C., and P. S. Martin. 2001. “Facilitating Communication Across Lines of Political Difference: The Role of Mass Media.” American Political Science Review 95 (1): 97–114. doi: 10.1017/S0003055401000223

- Oegema, D., and J. Kleinnijenhuis. 2000. “Personalization in Political Television News: A 13-Wave Survey Study to Assess Effects of Text and Footage.” Communications 25 (1): 43–60. doi: 10.1515/comm.2000.25.1.43

- Olson, M. 1965. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

- Publishers Audience Measurement Company. 2019. Individual Brand Reach – Newsbrands. April 2018 – March 2019. https://pamco.co.uk/pamco-data/data-archive/.

- Rawlinson, F. 2019. How Press Propaganda Paved the Way to Brexit. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Seymour-Ure, C. 1974. The Political Impact of the Mass Media. London: Constable.

- Shoemaker, P. J., and S. D. Reese. 2014. Mediating the Message in the 21st Century: A Media Sociology Perspective. New York: Routledge.

- Startin, N. 2015. “Have we Reached a Tipping Point? The Mainstreaming of Euroscepticism in the UK.” International Political Science Review 36 (3): 311–323. doi: 10.1177/0192512115574126

- Tolson, A. 2019. “‘Out is out and That’s it the People Have Spoken’: Uses of vox Pops in UK TV News Coverage of the Brexit Referendum.” Critical Discourse Studies 16 (4): 420–431. doi: 10.1080/17405904.2019.1592768

- Vliegenthart, R., A. R. T. Schuck, H. G. Boomgaarden, and C. H. De Vreese. 2008. “News Coverage and Support for European Integration, 1990–2006.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 20 (4): 415–439. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edn044

- Vonbun-Feldbauer, R., and J. Matthes. 2018. “Do Channels Matter?” Journalism Studies 19 (16): 2359–2378. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2017.1349547

- Vreese, C. d. 2007. “A Spiral of Euroscepticism: The Media’s Fault?” Acta Politica 42 (2–3): 271–286. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500186

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K., R. J. Sambrook, M. Berry, et al. 2013. Breadth of Opinion in BBC Output. London: BBC Trust.

- Walter, S. 2019. “Better off Without You? How the British Media Portrayed EU Citizens in Brexit News.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 24 (2): 210–232. doi: 10.1177/1940161218821509

- Wilkes, G., and D. Wring. 1998. “The British Press and European Integration.” In Britain for or Against Europe? British Politics and the Question of European Integration, edited by D. Baker, and D. Seawright, 185–205. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Yi Zhu, Y., and N. Carl. 2018. Are PPE graduates ruining Britain? MPs who studied it at university are among the most pro-Remain. LSE Brexit Blog, 11 November 2018. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/brexit/2018/11/14/mps-who-studied-ppe-at-university-are-among-the-most-pro-remain/.

- YouGov. 2019. In hindsight, do you think Britain was right or wrong to vote to leave the EU? https://whatukthinks.org/eu/questions/in-highsight-do-you-think-britain-was-right-or-wrong-to-vote-to-leave-the-eu/?notes.

- Young, H. 1999. This Blessed Plot: Britain and Europe from Churchill to Blair. London: Macmillan.

- Zaller, J. 1996. “Political Persuasion and Attitude Change.” In Political Persuasion and Attitude Change, edited by D. C. Mutz, B. Richard A, and S. Paul M, 17–78. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.