ABSTRACT

The possibilities of unfiltered communication in social media provide the perfect opportunity structure for spreading populist ideas. Generally, populist communication features an antagonistic worldview that blames elites for betraying the people and promises to reverse a ‘downward societal trend’ by bringing the people's ‘real’ interests back into politics. Although populist success is often attributed to crisis-induced dissatisfaction, research remains unclear on whether and how political actors foster such negative societal perceptions. Building on the German case, our paper accomplishes two things: It explores the use of populist social media communication and relates it to the exploitation of crisis-related messages among political parties. Conducting a manual content analysis of 3,500 Facebook posts by German parties and leading politicians, we find that the outsider parties AfD and the Left use and combine populist and crisis-related messages by far the most. Insider parties also spread crisis-related content to some extent. However, like the government parties, they are very reluctant to communicate in a populist way. By explaining the communicative output with their relative position in the party system, we deepen the understanding of parties’ social media behaviour. Overall, this study offers more in-depth insights into how politicians influence perceptions of the societal state.

Introduction

Populist parties have gained considerable popularity in almost all liberal democracies throughout Europe (Mazzoleni Citation2008; Wirth et al. Citation2016). Social media channels such as Facebook and Twitter, in particular, provide a breeding ground for populist messaging since they offer the opportunity structures that enable unmediated communication with recipients (Moffitt Citation2016). Unsurprisingly, a lot of research tackles social media and their role in the success of populists, especially the populist radical right (e.g. Engesser, Fawzi, and Larsson Citation2017; Groshek and Koc-Michalska Citation2017). Some studies also examine the extent of populist communication in social media (e.g. Ernst et al. Citation2017), with only a few focusing specifically on the German party landscape (e.g. Gründl Citation2020; Spieß, Frieß, and Schulz Citation2020; Stier et al. Citation2017).

This paper goes beyond previous work in offering a three-fold contribution: First, we provide the most extensive analysis of populist ideas in German parties’ Facebook communication based on manual coding to date. This analysis is also not limited to specific parties but instead studies the whole party landscape. Second, we explicitly scrutinize the role of crisis-related communication and its interaction with populist messages. Here we provide a novel operationalization of crisis-related Facebook content. Third, we make a theoretical contribution by explicitly relating different communication strategies on Facebook to the parties’ roles as outsiders, insiders, or government parties. Like much recent work, we follow the ideational approach toward populism and treat populist communication as a content feature of political texts (Engesser et al. Citation2017). According to this approach, populists share a few core ideas based on an antagonistic relationship between detached elites and the good people. From the populists’ perspective, political elites suppress the homogeneous will of the people in representative democracies, and it is the populists who aim at bringing back sovereignty to ordinary citizens (Mudde Citation2004). Populist parties and politicians see themselves as legitimate spokespersons defending the peoples’ very own interests in politics and the public – obviously also through political communication. Thus, communication is populist if it expresses the core populist ideas.

Such populist communication, especially on social media, might be ‘helping populism win’ (Groshek and Koc-Michalska Citation2017). However, economic, cultural, and political threats, often triggered by globalization (Inglehart and Norris Citation2017; Kriesi et al. Citation2006; Laclau Citation2005; Rippl and Seipel Citation2018), as well as a resulting sense of societal decline constitute the additional factors for populists’ electoral gains (Spruyt, Keppens, and Van Droogenbroeck Citation2016; Taggart Citation2004). Populists blame the political elites for the downfall of society, and they offer to resolve crises by refocusing on listening to the people and common sense. Some studies on the demand side even suggest that populism and a ‘sense of crisis’ only unleash their full power when they are combined (e.g. Giebler et al. Citation2020). Nevertheless, the crisis narratives often accompanying populist messages only played a minor role in studying populism in political texts (for partial exceptions, see Schmuck and Hameleers Citation2019; Wirz et al. Citation2019). By analyzing these two communication features, this paper makes a two-fold contribution. It sheds light on German parties’ social media usage of populism and uncovers how political parties combine populist features with crisis-related messages.

We chose Germany as an exemplary case for a Western European country because it represents a prototypical robust multiparty system that now faces new populist challengers (Arzheimer Citation2015). Moreover, Germany builds an ideal case for an explorative study regarding its wide-ranged party spectrum. According to electoral competition literature (Hobolt and Tilley Citation2016), we can differentiate between government parties (two moderate conservative and a social democratic party), insider parties (a green-liberal and an economic-liberal party), and outsiders (a more extreme left-wing and a right-wing party).

To answer our research question, we studied a sample of Facebook posts (N = 3,500) by the seven leading German political parties and their top politicians. Building on this text corpus, we conducted a manual quantitative content analysis using established measures to detect populism (e.g. Blassnig et al. Citation2018; Ernst et al. Citation2017). Since there was no existing measurement of crisis-related content in this context, we developed a novel measurement to reliably measure crisis content in political communication. Our results provide evidence of populism being predominantly an outsider phenomenon, as ideological fringe parties (especially the AfD [Alternative für Deutschland]), but also the Left) use populist messages by far the most (Petrarca, Giebler, and Weßels Citation2020). Regarding crises, at first glance, the variation across parties appears similar to populism, but there are considerable differences since insider parties also exploit crisis-related messages to a certain extent.

Our paper highlights that crisis and populism are interrelated yet distinct concepts. Differences between parties in the way crises and populism are used may be explained by a function of harsh us-vs-them rhetoric in populist communication and parties’ relative positions (as an outsider, insider, or government party) within the party system. Overall, our framework may serve as a template for future research to gain more in-depth insight into the dynamics of party communication in social media against the backdrop of populist challenges in various political systems.

Populist communication

Due to their electoral success and enduring presence in various liberal democracies, social scientists have investigated the populist phenomenon from a theoretical (Canovan Citation1999; Laclau Citation2005; Mouffe Citation2005; Mudde Citation2004; Taggart Citation2004) as well as an empirical perspective (Akkerman, Mudde, and Zaslove Citation2014; Castanho Silva et al. Citation2020; Schulz et al. Citation2017). Particularly, Mudde's ideational approach to populism has gained much attention in empirical political science (e.g. Hawkins et al. Citation2018). In the ideational approach, populism is defined as a set of ideas or a ‘thin-centred ideology’ that can be enriched with right-wing (e.g. nationalism), left-wing (e.g. socialism), as well as less common, centrist political ideologies (Mudde Citation2004, 544). This definition serves as a ‘minimal definition’ that centres around the features populist politicians and movements must share in order to be labelled populist.

In a nutshell, the idea of the homogeneous people that demand more sovereignty against the ‘corrupt’ elites (anti-elitism) can be regarded as the ‘thin’ core in the ideational approach (Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2018). Thus, two homogeneous and antagonistic groups with conflicting interests exist in society. The corrupt elites are to blame for societal decline since they are incompetent or only pursue their own interests and disregard the people's wishes. In theory, populist politics seeks to empower the good and honest people against the ‘detached’ elites (Wirth et al. Citation2016).

Focusing on political communication, we consider communication as populist if it conveys the ideas mentioned above. Thus, populist communication entails messages that attack the elites, appeal to the people, and demand more sovereignty for the people and their will (Ernst et al. Citation2019; Wirth et al. Citation2016). In populist communication, populists are by the people’s side; they speak in their name and equate their viewpoint with the general will of the people (Caramani Citation2017; Müller Citation2017). Our approach, however, is not the only one possible. Engesser, Fawzi, and Larsson (Citation2017) distinguish different approaches regarding their respective research interest. Our ideational approach focuses on the content of populist communication (What?).

Other research considers populism primarily as a political style and thus is concerned with the presentation and form of populist communication (How?; e.g. Moffitt Citation2016). Lastly, analysis of populism as a strategy aims to explain the goals and motives underlying populist rhetoric (Why?; e.g. Weyland Citation2001). However, style and strategy are not necessarily defining features of populist movements since not all populist parties have a particular style of doing politics (e.g. rough or shirt-sleeved) or employ specific strategies (e.g. focusing on a charismatic leader). Conversely, it may also be possible that parties use stylistic and strategic elements of populism without being populist at heart (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2013). Since we are primarily interested in the very content of political messages, we use a ‘minimal definition’ of populism that only entails the core ideas of a populist mindset as suggested in the ideational concept (Hawkins et al. Citation2018).

Empirically, populist ideas might flourish in all kinds of media such as party manifestos (Rooduijn and Akkerman Citation2017), press releases (Bernhard and Kriesi Citation2019), party broadcasts on TV (Jagers and Walgrave Citation2007), or political talk shows (Ernst et al. Citation2019). Nevertheless, new media provide the perfect opportunity structure for populist communication (Bos and Brants Citation2014). Social media channels like Facebook and Twitter are particularly well suited for populist messaging. They allow the circumvention of gatekeepers (i.e. journalists and media organizations considered part of the rejected elites), mutual exchange of populist ideas, and the mobilization of supporters (Chadwick Citation2017; Jungherr, Schroeder, and Stier Citation2019; Rone Citation2021). Since populists are particularly interested in close contact with the people, the opportunity of reciprocal interaction creates a feeling of intimacy between individuals and populist leaders. Consequently, Ernst et al. (Citation2017, Citation2019) as well as Schmuck and Hameleers (Citation2019) find that populist content is more widespread on social media, especially Facebook, than other media outlets.

These populist messages can be detected in different party contexts and countries but often appear in fragmented form (Engesser et al. Citation2017). Previous studies confirm – at least for countries in Western Europe – that almost all parties use populist communication to a certain extent. However, extreme parties on the left and right, opposition parties, and, not surprisingly, populist parties rely on it more frequently. For example, Schmuck and Hameleers (Citation2019) report (based on Austria and the Netherlands) that all parties, but in particular left- and right populist parties, exploit populist messages on their social media channels. A six-country comparative study by Ernst et al. (Citation2017) finally confirms that fringe and opposition parties are also more populist in their social media communication than mainstream and governmental parties.

On the role of crises for populism

However, populist ideas alone might not explain the appeal of populist parties. Their populism should thrive in a situation where they are also able to proclaim a crisis. Indeed, a stream of literature is concerned with crisis-induced dissatisfaction as an important cause of the populist rise. Canovan (Citation1999) argues that the attractiveness of populist parties is rooted in a crisis of the political system producing deep disaffection with the promise and performances of representative democracies. Meny and Surel (Citation2002) understand populism as a reaction to a malfunctioning political system; Laclau (Citation2005) sees a lack of representation as an ‘unfulfilled demand’ of democracy and populism as a logical consequence of these unfulfilled needs in the population. Mudde (Citation2004) associates the concept of populism – relatively vaguely – with social crises triggered by massive transformations toward a post-industrial society. More specifically, Kriesi et al. (Citation2006) argue that populist parties are mainly supported by ‘losers of modernization,’ that is, people who are most disadvantaged by globalization in economic, cultural, and social terms.

Thus, populism can be seen as the logical consequence of an objective economic, political, or societal threat (Kriesi et al. Citation2015). Further studies consider crises – a subjective negative perception of the state of society – as an inherent part of the populist belief system itself (Kaltwasser Citation2012; Moffitt Citation2015; Rooduijn and Burgoon Citation2018). Similarly, Taggart (Citation2004) strongly links populism to a so-called ‘sense of crisis,’ which can best be described as the feeling that society is heading towards a tipping point – which would culminate in the collapse of society if nothing is done to prevent it.

Building on this line of research, recent studies highlight that it is not only objective factors but also the perception of a malfunctioning society that drives populist support (Gest, Reny, and Mayer Citation2018; Giebler et al. Citation2020; van der Bles, Postmes, and Meijer Citation2015). However, where do these feelings of crisis stem from? It stands to reason that populists fuel this perception of societal situations as threatening and critical in their communication. Brubaker (Citation2017) points out that politicians themselves create a framework of crisis to push their populist policies as the only alternative. By emphasizing the urgency of a situation and the need for immediate action in the crisis, this communication strategy enables populists to create a divide between the people and the elites, presenting themselves as the people's advocates and reprimanding the elites for their behaviour (Moffitt Citation2015). Accordingly, Wirz et al. (Citation2019) show that a dramatizing communication style creates a sense of crisis, which increases the persuasive power of a populist message. In this sense, populist actors can be considered as political entrepreneurs who exploit crisis narratives as a tool to expand their supporter base. They act as ‘agents of discontent’ (van Kessel Citation2015) or ‘crafty identity entrepreneurs’ (Mols and Jetten Citation2016) and use the resonance effect of populist ideas and threatening crisis scenarios.

Research based on political texts may be unable to assess whether a society is facing an objective crisis or not. However, it can analyze whether political actors frame social situations negatively in order to benefit from the combination of crisis and populism. Unfortunately, supply-side studies on the co-occurrence of populism and crisis-related content in political communication are still underrepresented. However, first empirical results suggest that elements that reinforce crisis perceptions often occur together with populism in political parties’ communication. Schmuck and Hameleers (Citation2019) find a strong link between negative emotions in the communication style of politicians and populist content. Rooduijn's (Citation2014) qualitative case study shows that the proclamation of crises frequently appears with anti-elitism, homogeneity, and people-centrism. Ernst et al. (Citation2019) are the only ones to compare the combined use along party ideological lines. They note that extreme parties tend to mix up populist language with crisis-related stylistic elements (e.g. negativity) more frequently than mainstream parties.

Populism and crises in the social media communication of German parties

Some studies in the German context address the communication strategies of the radical-right populist AfD from a qualitative empirical perspective (Berbuir, Lewandowsky, and Siri Citation2015; Kim Citation2017). Other research deals with the populist surge in analyzing social media output of German parties, measuring user reactions (e.g. comments, likes, shares), or comparing topic use on social media (Schwemmer Citation2021; Serrano et al. Citation2019; Stier et al. Citation2017, Citation2018). Nevertheless, few authors explicitly analyze populist content by political parties in social media and usually from a comparative perspective rather than specifically for the German case (Ernst et al. Citation2017, Citation2019). A small-N case study by Spieß, Frieß, and Schulz (Citation2020) shows that German Social Democrats (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, SPD) and the Christian Democrats (Christlich Demokratische Union, CDU) use significantly less populist content in their Facebook posts than the AfD. Running a dictionary-based content analysis, Gründl (Citation2020) also identifies the largest amount of populist messages with the AfD, followed by the Left (Die Linke) by a considerable margin. All other German parties are much more restrained in their use of populism. But there is still no literature that systematically examines the distribution of populism among German political parties in the context of crisis-related communication in social media.

This gap is remarkable since the German party landscape offers a wide variety of parties with high ideological variance. On the right fringe, Germany has with the AfD a clear-cut right-wing populist party (Arzheimer Citation2015; Arzheimer and Berning Citation2019), while at the extreme left, the Left can be regarded as a borderline case of a populist party (Gründl Citation2020; Lewandowsky, Giebler, and Wagner Citation2016). Currently, the economically liberal FDP (Freie Demokratische Partei) and the Greens (Bündnis 90/Die Grünen), an ecological left-wing liberal party, remain in opposition. The three major German parties, the moderate left social-democratic SPD and the moderate right-conservative CDU and CSU (Christlich-Soziale Union), form the government coalition.

Since we aim to find structural differences between party communication, we draw on electoral competition literature – introducing the concept of outsider, insider, and governing parties. Following this research line, parties are classified according to their relative position in the respective party system, namely past, present, and (expected) future government participation. Both government and insider parties can be considered ‘mainstream’ parties representing the political status quo and only differ regarding their present participation in government (Hobolt and Tilley Citation2016). In contrast, outsider parties are untouched by office duties. They have a history and future of not being coalitionable because they are new, often radical parties that do not want to – or the mainstream parties do not let them – participate in government. Unlike insiders, who are counted as ‘effective’ parties, they stand outside the political system (Barr Citation2009). According to this classification, parties are expected to differ in terms of tactical and strategical considerations, including external communication (van de Wardt, De Vries, and Hobolt Citation2014).

Germany provides a fascinating case, since two parties with opposing ideological positions represent each category (Barr Citation2009). Petrarca, Giebler, and Weßels (Citation2020) suggest categorizing German parties based on their national government participation in the last thirty years. Following their operationalization, the Left and AfD can be classified as outsiders; the FDP and the Greens are labelled insiders, while SPD, CDU, and CSU are the government parties.

Since we do not yet know how German parties use populist and crisis-related communication, we explore how such messages are distributed among the social media accounts of the different political parties. We take advantage of the multi-faceted German party landscape to investigate whether and how populist and crisis-related messages are used as a potential strategy to appeal to voters. Based on the gaps in the literature, we consider if both elements are used simultaneously and provide first insights into the function of crises in communicating populist ideas from an empirical political communication perspective.

Data and methods

As indicated above, a growing number of studies addresses populist content in political texts. Nevertheless, methodological approaches still vary substantially (for an overview, see Aslanidis Citation2018; Pauwels Citation2017). Based on the ideational notion of populism as a core ‘set of ideas’ (Wirth et al. Citation2016), researchers are exploiting texts as a data source with quantitative but also qualitative methods (e.g. Engesser et al. Citation2017). For our deductive approach of measuring populism, automated dictionaries and manual content analysis seem the most appropriate tools. Dictionaries offer the great advantage that they can be applied very quickly and cost-efficiently (Rooduijn and Pauwels Citation2011). However, the only readily available German dictionary for social media (Gründl Citation2020) lacks final validation against manually coded content. What is more, it does not detect crisis-related messages. We therefore collect all our data using manual content analysis.

Luckily, there are already several populism studies (e.g. Blassnig et al. Citation2018; March Citation2017) in different temporal and country contexts based on the ‘gold standard’ of manual coding (Song et al. Citation2020) that could serve as a starting point. Unfortunately, only a few studies operationalized populism and crises simultaneously. Moreover, these studies grasp crises exclusively as a stylistic feature captured by rhetoric elements such as tonality (Ernst et al. Citation2019; Schmuck and Hameleers Citation2019; Wirz et al. Citation2019). Therefore, we developed a novel measure that encompasses different facets of crises in political texts.

Sample

Since we are interested in populist and crisis-related communication aimed at the general public, we draw on Facebook data from German parties and politicians. Facebook is by far the most used social network in the German context (Beisch and Schäfer Citation2020). More importantly, Facebook provides an intimate environment for reciprocal interactions since it is socially rather diverse and targeted at regular citizens. In contrast, Twitter is dominated by journalists and other practitioners who use the network for professional purposes (Schmuck and Hameleers Citation2019).

We collected data from six months before the German Bundestag election on 24 September 2017 to one year after the election (24 March 2017–24 September 2018). Thus, this period entails the electoral campaign, coalition building and a period of ‘business as usual’ after the election. For each party, we included the party account and three accounts belonging to prominent politicians. Our account selection aims at capturing a representative segment of the parties’ social media activities. By including the accounts of prominent party figures, we also ensured that the studied content reached a broad audience (see Online Supplement A).

In total, we downloaded 16,448 posts from 28 accounts. We then drew a sample of 3,500 posts from the overall population, as it would not have been feasible to code all available posts manually. In drawing the sample, we stratified it by parties and accounts to allow inferences for each party and every account. Due to the fact that some actors hardly use populist messages (Gründl Citation2020), we also oversampled populist parties and posts that included a term listed in available populism dictionaries (Gründl Citation2020; Pauwels Citation2017; Rooduijn and Pauwels Citation2011). To account for this stratified sampling procedure with different sampling probabilities, we created corresponding sampling weights applied in all analyses presented in this paper (see Online Supplement A for a detailed description of the account selection, sampling, and weighting).

Coding process

Five student coders coded the 3,500 posts. The coders underwent extensive coder training. After an initial pre-test, we followed up on critical issues and once more clarified the codebook. The main coding of the material took place in March and April 2020. We conducted three inter-coder reliability tests – at the beginning of the coding process, around half-time, and one towards the end. The intra-coder reliability test was based on ten percent of the total sample (i.e. 350 posts that were coded by each coder). We supervised the coders during the whole process using the communication platform Slack; however, no communication was available to coders during inter-coder reliability testing.

Operationalization

We have developed a codebook that allows precise and fine-grained measurement of populist messages while also offering a completely new measure for detecting crisis messages at the level of individual Facebook posts. The selection of variables for populist messages are inspired by work from the EU-COST project ‘Populist Communication in Europe’ (e.g. Blassnig et al. Citation2018), but also benefits from other codebooks in the field (Wirth et al. Citation2017). At the beginning of the codebook, general coding guidelines for coders are summarized. Two main parts can be distinguished, one for populism and one for crisis-related messages. Each part starts with a general definition followed by the actual measurement, which is divided into categories. Each category represents a specific element of populism or crises communication. The categories entail explicit definitions and examples for the coders. For each category, the coders indicated whether the described element occurs or not.Footnote1

Populist messages

Generally, we follow the framework by Wirth et al. (Citation2016) for measuring populist communication in text. Populist messages are classified into a total of eight categories, covering the three main dimensions of populist ideology: anti-elitism, people-centrism, and sovereignty (see in Appendix and Online Supplement B). Since Facebook posts consist of relatively short text pieces, we do not expect all populist elements to appear in a single post. Rather, we regard populism as a ‘fragmented ideology’ (Engesser et al. Citation2017) that spreads across the entire communication output of a particular account. Therefore, a Facebook post is counted as populist if at least one of the various populist elements is present (see Ernst et al. Citation2017; Schmuck and Hameleers Citation2019). This binary measure of populism achieved satisfactory inter-coder reliability for the exploratory analyses of such a complex construct (Gwet’s AC1 = .73).Footnote2

Crisis-related messages

Based on the literature on populism and crises, we have developed a novel measure to detect crisis-related messages in political texts. In general, a crisis is a turning point in a dangerous development preceded by massive disruption. The turning point is characterized by a decision-making situation, usually offering both the chance to resolve the conflict and the opportunity to escalate it (Koselleck and Richter Citation2006). Various authors have extended this concept theoretically with regard to populist communication (Brubaker Citation2017; Moffitt Citation2015; Taggart Citation2004). Based on their ideas, we have identified four core features of crisis messaging:

A negative situation is described as extremely urgent. Fast action is required (urgency),

the communicator dramatizes the present situation by using strong exaggerations (dramatization),

adverse outcomes for society are strongly emphasized (societal consequences) and

a failure is identified.

We created and refined coding rules for all four elements. Necessarily, all crisis messages express a pessimistic view of the current societal situation. However, this is not a sufficient condition to be counted as a crisis message, and at least one of the four crisis elements must be present as well (see in Appendix). Existing measures on ‘negative campaigning’ or ‘negative emotions’ usually address the (negative) tonality of a given content in general, while our approach defines crises as a subset of negativity by solely focusing on messages about societal topics that contain the specific features of a crisis (Freedman and Goldstein Citation1999; Widmann Citation2021). This binary measure of crisis-related communication in a Facebook post also attains satisfactory intercoder reliability (Gwet’s AC1 = .75).

Research strategy

For the subsequent analyses, we combine descriptive and multivariate statistical methods. We compute three main logistic regression modelsFootnote3 (see in Appendix) with populist communication, crisis-related communication, and populism and crisis-related communication appearing together as dichotomous dependent variables. Our main independent variable, party affiliation (of the account), is coded as a categorical variable with the only clear-cut populist AfD as the reference category. For improved clarity and facilitated interpretation, we use predicted probabilitiesFootnote4 in the main text. This measure allows us to show the probability of crisis-related or populist content in a post for every party based on our logit regression models.

To control for confounding factors, we included the type of account (i.e. whether it is the main party account or an individual politician’s account) and the post type with status updates (n = 230) as the reference category – other post types are video (n = 883), photo (n = 1862), and link/other (including link [n = 517], event [n = 7], and note [n = 1]). Moreover, we also included the post length (as word count, rescaled to range from 0–1), the publication date (divided into six three-month periods; reference category: last period before elections), and the post’s main topic (in nine categories) as covariates in all models described below.

Results

Overall, 20.1% of the 3,500 coded messages contain at least one element of populist communication, while crisis-related messages appear slightly more often (25.2%). Comparing the three populism dimensions, anti-elite messages (15.4%) are used most frequently, but people-centrism (11.5%) is also relatively prominent. In contrast, popular sovereignty occurs in only 5% of all posts. Furthermore, shows the frequency of every single element in the dataset. Two crisis elements (identification of failure [17.6%] and proclaiming societal consequences [15.2%]) are most pronounced, followed by the populist discrediting of the elites (13.1%). While populist communication is frequently present overall, it is striking that some core elements from the theoretical literature on populism (praising of the people [0.5%] and a call for sovereignty [0.4%]) are empirically hardly present in the collected Facebook posts. Even without populism, crisis-related messaging seems to be an important component of political communication on social media.

Table 1. Frequency of posts containing elements of populist or crisis-related messages.

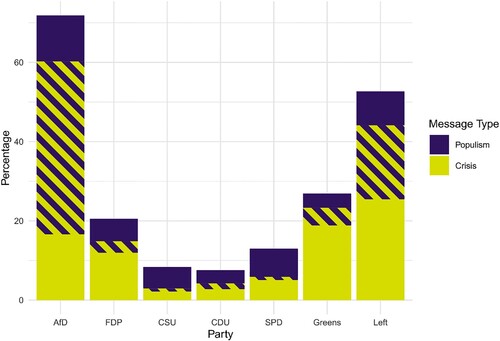

In the next step of our analysis, we plot the use of populist and crisis-related messages by German political parties (see ).Footnote5 We differentiate between populist (yellow bars) and crisis-related messages (purple bars); the hatched parts represent the proportion of messages that contain both populist and crisis-related elements at the same time. The respective bars display how often (at least one element) occurs in a given party's messages. 55.3% of all AfD messages contain populist content in some form (alone or in combination with crises), followed at a considerable distance by the Left (27.3%). All other parties use populist messages significantly less. No significant differencesFootnote6 are detectable between the third-placed FDP (8.6%) and last-placed CDU (4.8%).

Figure 1. Shares of populist and crisis-related messages by party.

Note. The hatched parts represent the proportion of posts combining both populist and crisis-related messages.

Similar to populism, we also compare the use of crisis-related language (alone and in combination with populism). Again, the AfD (60.2%) has the highest proportion of crisis-related messages, followed by the Left (44.1%). Remarkably, the AfD uses crises slightly and the Left considerably more often than populism in their messages. While no difference between government and insider parties could be measured in populist messaging, the Greens (23.3%) and FDP (14.9%), score significantly higher than the governing CDU (4.2%), CSU (2.9%), and SPD (5.9%) regarding crisis-related communication.

It is striking that the outsider parties, AfD (43.6%) and the Left (18.7%), use the combination of populism and crises (hatched parts) particularly frequently relative to using these messages alone and also compared to the other parties. The Greens (4.4%) exploit the combination of populism and crises more often than populist messages alone. All other parties tend to use either crisis or populism exclusively, but rarely the combination of both (FDP = 2.9%; CDU = 1.4%; SPD = 0.8%; CSU = 0.7%).

Thus, the combination of crises and populism is not a mandatory one: While 60.7% of AfD's messages that contain at least one of the two elements are populist and crisis-related at the same time, 39.3% do not (populism only: 16.2%; crisis only: 23.1%). For the Left, the relative proportion of messages containing both elements compared to messages that are only crisis-related or only populist is 35.6%; for all other parties, the respective share is significantly lower (CDU = 18.8%; Greens = 16.5%; FDP = 14.2%; CSU = 8.9%; SPD = 6.1%). The overall picture remains clear: The AfD makes the most use of populism and crises. The great distance to other parties can mainly be explained by the frequent combination of both elements. On the other ideological extreme, the Left confirms its status as a borderline case. Due to the high exploitation of crises (exclusively but also in combination with populism), they also stand out from the other opposition parties, but at the same time, also lag well behind the AfD. Overall, the insider (FDP and Greens) and government parties (CDU, CSU, and SPD) employ populism at a similarly low level. However, they can be distinguished by their use of crisis, which is relatively pronounced for insider parties but not for the governing parties.

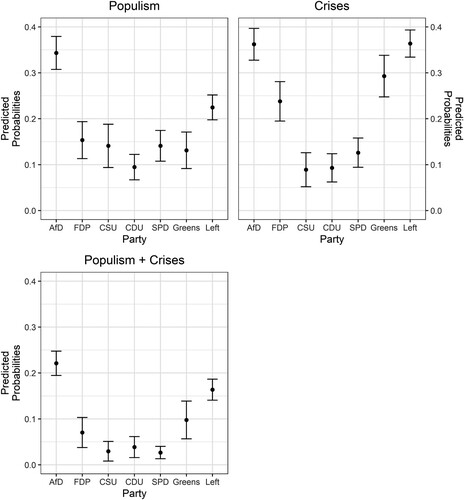

In order to get a better picture of the differences between parties, we ran a series of logistic regression analyses. We calculated and plotted the predicted probabilities for different parties for all logit models to compare the parties’ probabilities to use populist, crisis-related messages or the combination of both. In Model I (McFadden's R² = 0.35), we treat populism in Facebook posts as the dependent variable and include important control variables (full results from Model I and the following Models II–V can be found in in the Appendix).

Starting with the controls, our results suggest that account type, post type, and the date of the postFootnote7 did not affect the prevalence of populist messages. Wordcount, unsurprisingly, has a strong positive effect on populist messages. Finally, compared to the reference group economy, all topics exert a negative impact on populist messages. Considering the account’s party affiliation and other controls, messages on economy most likely contain populist features.

But even when controlling for these confounders, the results from the descriptive analysis remain stable. The upper left part of indicates the highest probability for a message to be populist for the AfD (34.3%), followed by the Left (22.5%). All other parties score at considerablyFootnote8 lower levels than the two parties on the ideological extremes. The probability of a populist message is lowest for the CDU at 9.5%. The Greens (13.1%), the CSU (14.1%), the SPD (14.1%), and the FDP (15.3%) also remain at a relatively moderate level.

Figure 2. Predicted probabilities for populist, crisis-related and populist + crisis-related messages by party.

Note. Based on logit models (Model I- Model III) in in Appendix.

Next, we computed a second logit regression (Model II; McFadden's R² = 0.43), including the same independent variables as in the former model, but with crisis communication in the Facebook post as the dependent variable. Overall, the controls exert a moderate impact on crisis-related messages (except of other/no substantial topics: b = −1.96, SE = 0.21, p < 0.001). In this model, the effect of the topics does not deviate significantly from each other.

Unlike the populism model, regression results and derived predicted probabilities (see the top right plot in ) lead to slightly different findings compared to the descriptive results. The Left’s messages are now most likely to be crisis-related (36.3%). However, the probability for the AfD is at a similar level (36.2%). Messages by the Greens (29.3%) or the FDP (23.8%) also have a high probability of including at least one crisis element. Regarding crisis-related communication, the two insider parties – especially the Greens – are much closer to the outsider parties than in regards to spreading populism. Messages from the governing parties SPD (12.6%), CDU (9.3%), and CSU (8.9%) have a significantly lower probability of entailing a crisis reference.

Summing up these results, we can state that all parties use populist and crisis-related messages, although to a strongly varying extent. A certain parallel between the spread of crisis and populism through parties seems undeniable (see ). Nevertheless, it is noticeable that populist messages are either used a lot (AfD and the Left) or very little (all other parties). In contrast, the differences for crisis messages are more nuanced. Parties can be divided into three groups: AfD and the Left employ crisis communication the most, but insider parties (Greens and FDP) also make regular use of it. In contrast, the governing parties CDU, CSU, and SPD adopt significantly less crisis communication in their Facebook posts.

In Model I and Model II, we have considered populism and crises empirically separate from each other. However, we have also theorized that populist and crisis-related communication often occur together. To study this combination of messages, we ran an additional model that estimates effects for the occurrence of both elements in Facebook posts (1 = populism and crises appear together; 0 = all other possible outcomes). This third logistic regression model (Model III; McFadden’s R² = 0.46) again includes the categorical party variable as the primary independent factor and the other parameters as controls (see in Appendix). As the predicted probabilities (bottom left in ) indicate, the AfD maintains its prominent position standing out from all other parties. The probability of a message containing populism and crisis simultaneously lies slightly above one-fifth (22.1%) for the AfD. All other parties are significantly less likely to use messages that combine elements of populism and crises. Again, the Left scores relatively high (16.4%), followed by the Greens (9.8%) and the FDP (7%). Unsurprisingly, the government parties have the lowest probability of using populism and crises in combination (CDU = 3.9%; CSU = 3.0% and SPD = 2.7%).

While our results indicate that the populist radical right AfD communicates populist ideas on Facebook a lot, it is also apparent that many of these messages also portray a crisis. Thus, it is not certain that the AfD, and the Left, are indeed more populist than other parties or if their populism is simply a by-product of portraying critical situation(s) they have identified. Therefore, Model IV predicts populist content on Facebook but also controls for the depiction of crises in these messages (see in Appendix). Comparing Model I (without crises as explaining variable) to Model IV (including crises), we find no substantial differences in the overall model fit (McFadden’s R² = 0.36) and coefficients. Populism is indeed more prevalent in posts that include a crisis-related message, but the AfD and the Left are also more populist than other parties even when controlling for the presence of crises.Footnote9

Summary and discussion

With increasing electoral success in Western democracies, the presence of populist parties in public discourses has also proliferated, not least through aggressive political communication in social media (Aalberg et al. Citation2017). Searching for the multiple causes for trending populism, some demand-side studies find growing evidence that populist parties build their success, among other factors, on the narrative of a collapsing society. Based on the unfolding sense of crisis, ‘corrupt elites’ can be made responsible for perceived negative societal trends, allowing populism to exert its full force (Spruyt, Keppens, and Van Droogenbroeck Citation2016). Social media channels may reinforce populist tendencies in rewarding emotionalizing and dramatizing language with more attention. Moreover, social networks supply the perfect opportunity structure for outsiders to spread their ideas without the corrective impact of journalistic gatekeepers and serve as an echo chamber for extreme positions at the same time (e.g. Jungherr, Schroeder, and Stier Citation2019; Schmuck and Hameleers Citation2019). Nevertheless, data combining populist and crisis-related communication are still rare. Therefore, this paper aims to set an empirical basis for the discussion on populist and crisis-related communication in political parties’ social media outreach. To capture the distribution of populism and crises across parties, we conducted a quantitative content analysis containing 3,500 Facebook posts by German political parties and top politicians. In addition to familiar tools for tracking populism in political texts, we have developed a new measure for capturing crisis-related communication, which could also serve future research to identify crisis content in political texts.

How do German parties differ regarding the use of populist messages on Facebook?

Results clearly show that all German parties use populist communication on social media. Unsurprisingly, the AfD scores exceptionally high, but also the Left differs significantly, albeit less clearly, from the other parties. The CDU, CSU, SPD, Greens, and the FDP draw very little on populist language. These results support earlier findings identifying the AfD as the only clear-cut populist party in the German context (Lewandowsky, Giebler, and Wagner Citation2016). We further contribute to the ongoing discussion on the question of whether the Left is populist. Unlike categorized in the PopuList (Rooduijn et al. Citation2019), our data suggest classifying the Left as a borderline case between a populist and a non-populist party (Gründl Citation2020). Simultaneously, these corresponding results serve as a good indicator of high external validity for our measurement of populism.

To address the described dichotomous division of parties regarding populism (i.e. high values for AfD and the Left versus low values for the other parties), we draw on the concept of outsider, insider, and government parties (Barr Citation2009). Since outsiders have no chance of participating in government, they can expect – from a cost–benefit perspective – the greatest success by working against the established political system and mainstream parties (McDonnell and Newell Citation2011). Therefore, the us-against-them-driven populist rhetoric fits perfectly for outsider parties at the party system's fringes. This is, of course, different for government parties but also for insider parties that have recently participated in government or hope to return to power anytime soon. From a Manichaean populist viewpoint, they are part of the criticized political elite. As such, insiders cannot credibly offer anti-elite appeals, resulting in a low motivation for being populist.

The negative campaigning literatureFootnote10 also provides insights into such differences in the populist blame strategy and argues along similar lines. The propensity for negative campaigning depends on the coalition potential of a particular party (i.e. government experience and the ideological distance to the median party). Thus, political attacks on the government parties, including the kind of brash anti-elite rhetoric populists often employ, may serve outsider parties. Insider parties, however, might refrain from attacking their potential coalition partner with antagonistic anti-elite rhetoric, as such behaviour might more easily backfire for them and could also negatively affect future negotiations with the challenged party (Lau and Rovner Citation2009; Walter, van der Brug, and van Praag Citation2014).

How do political parties use crisis-related messages?

Focusing on crisis messages – both alone and in the nexus of populism, we measured a gradual regression from ideological extreme to centrist political positions. The Left and the AfD make extensive use of crisis messages; the Greens and the FDP also reach a relatively high level. The government parties are relatively reluctant to employ crisis-related content on Facebook. Unlike populism, the proclamation of crises appears a reasonable tool for the oppositional Greens and the FDP. These results can be interpreted through the retrospective voting literature suggesting that voters’ electoral behaviour is strongly influenced by the government’s past performance and the resulting current situation of the country (Healy and Malhotra Citation2013). Therefore, non-government parties should maintain a natural interest in forcefully addressing undesirable societal developments. Insider parties that do not belong to the current government can and should also normatively address, to a certain degree, unsatisfactory developments caused by governmental action. To an even greater extent this applies to outsider parties that are less coalitionable and need to be less worried about tarnishing their chances of participating in government.

What is the linkage between populism and crisis in political communication?

Despite described variations in the use of populism and crisis-related content between political parties, the literature supposes strong interactions between both concepts. Since it remains empirically unclear how political parties actually combine both elements, we conducted some further analyses. First of all, we found only partial evidence for frequent combined use across all parties, since mostly ideological fringe parties, and to a much lesser extent the Greens, post texts that include both elements. Foremost, the AfD exploits both message types in the same post (see and ). The party’s pronounced outsider status could explain why this party is particularly prone to spreading crisis-related and populist communication.

However, this result alone does not answer why the AfD and the Left take advantage of this combination. Following the idea of populism as a ‘thin-centered ideology’ (Mudde Citation2004) and of populist communication as ‘a master frame […] to wrap up all kinds of issues’ (Jagers and Walgrave Citation2007, 322), one may argue that they use populist reasoning strategically to promote a ‘thicker’ or more substantive agenda – in our case, the portrayal of an unsatisfactory or even dangerous state of society. Our findings partially confirm this claim in the sense that the presence of crises does indeed significantly impact the occurrence of populism. Thus, we could speculate that populist outsiders use populist argumentation as an instrument to fuel anger against the governing elites whom they blame for various societal disruptions in a populist way.

Yet, controlling for crisis-related content in a post does not account for much variation in the parties’ propensity for populist communication. Moreover, descriptive findings and distinct patterns of utilization along the lines of outsider, insider, and government parties rather argue against this interpretation (see ). Populism is not exclusively used to amplify and promote a sense of crisis. To a considerable extent, the two concepts are exploited independently by different parties. Hence, based on these findings, we would argue that populism and crisis should be treated as distinct concepts (cf. Moffitt Citation2015).

A limitation of our study is that we only concentrated on political texts on Facebook. As images and videos might be relevant carriers of meaning on social media, future research should also include these features. Additionally, we only focused on one single social media platform. Since it is the most popular social network, it provides access to the so-called ordinary people. Accordingly, research suggests that Facebook is more saturated with populism than the somewhat elitist Twitter (Schmuck and Hameleers Citation2019). Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether the same holds for crisis-related messages. It is also important to note that the logic of attention is particularly strong in social networks. Therefore, it may be fruitful for future research to investigate whether populist and crisis-related messages are more popular than other message types in terms of shares, likes, and comments (e.g. Serrano et al. Citation2019). But, due to media commercialization, including dramatizing and emotionalizing communication styles, populist and crisis-driven language has also spread in all kinds of professional media and political communication (e.g. Bernhard and Kriesi Citation2019; Blassnig et al. Citation2018). Research should address the question of whether populism and crises are actually more widespread in social media, with their algorithms and potential filter bubbles, than in other media (cf. Ernst et al. Citation2019).

Furthermore, even if our operationalization is common and conceptually based on the idea of populism as a thin ideology that only occurs in a fragmented form (see Engesser et al. Citation2017; Schmuck and Hameleers Citation2019), we have applied a liberal criterion to qualify a message as populist or crisis-related; only one element needs to appear in a given message. We recommend keeping this fact in mind, especially when interpreting the descriptive results on the overall prevalence of populism and crises on social media. Moreover, we have restricted our sample to German top politicians and parties at the national level. This selection allows us to provide an exemplary overview of the most visible and critical party accounts. Follow-up studies should include ordinary members of the Bundestag, politicians, and parties from the Landtag or municipal level to map the full range of parties’ social media communication.

The German multiparty system constitutes a particular case, as a kind of cordon sanitaire prevents radical populist parties from entering the government at the federal level.Footnote11 In other countries, populists may no longer qualify as outsiders since they have already participated in government. As argued by the widespread inclusion-moderation thesis, we would generally expect populists to dampen their rhetoric when moving from an outsider position into the centre or even entering government (Krause and Wagner Citation2019). At the same time, they might also rely on the mutability of the populist appeal. Their anti-elitism may shift from national political elites to critical media, oppositional intellectuals, democratic institutions, or supranational actors (Barr Citation2009). Similarly, the depiction of crises might shift toward supranational crises.

Which strategy prevails might also depend on the context. In some Western democracies, populists join coalition governments with more established parties (e.g. Austria). In such cases, the pressure to, at least somewhat, moderate their populist and crisis rhetorics might be high. In other countries (e.g. Hungary, Czech Republic), populists gain a large or even absolute majority in parliament and face a less resilient democratic system (Guasti Citation2020; Kim Citation2021). Populists in power in such cases have little reason to restrain their rhetoric. In general, it would be worthwhile to comparatively assess the use of populist and crisis-related messages in cases where populists do not qualify as outsiders anymore. Moreover, our findings are not easily transferable to a two-party system such as in the US, where distinctions regarding parties’ outsider or insider status do not apply.

Demanding popular sovereignty is an integral part of the theoretical idea of populism. Yet, this element is little exploited by German actors and other parties in stable Western democracies (Ernst et al. Citation2017; Schmuck and Hameleers Citation2019). One reason for this could be that (right-wing) outsiders in most of these countries are more interested in destabilizing elites than in empowering the electorate. Instead, references to the people might primarily serve a symbolic purpose of confirming the claims of the populist movement (Müller Citation2017; Schulz et al. Citation2017). In contrast, popular sovereignty demands might be more prevalent on social media in countries with more inclusionary populist movements (e.g. Latin America; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2013).

Thanks to our new measure of crisis as a content feature, we found that populism particularly often coincides with crises in the social media accounts of parties at the ideological fringes. However, future experimental research could examine whether the combined use of populism and crises activates certain predispositions and mobilizes party support or political action in general. Research in this direction could uncover both underlying psychological mechanisms for populist support on the demand side and underlying tactical motives of parties’ communicative behaviour on the supply side.

Like Rooduijn (Citation2014), we could not find strong evidence for a widespread populist zeitgeist in the German context because populism does not seem to spread across all parties. However, we must note that a longitudinal design mapping the potential rise of populist communication over time would be necessary to disprove this popular narrative. Overall, our work intends to represent a first step in understanding party behaviour on social media regarding the use of populism and crisis-related communication. Our study contributes to the state of research in finding populism to be an outsider phenomenon – in contrast to crisis-related communication, which oppositional insider parties also employ. In the political arena, these communication patterns, especially the combination of the two elements, might help parties on the sidelines to attract voter attention and increasingly intervene and engage in politics. Even if we do not aim to assess the democratic value of these communication strategies with our approach, future research should investigate the consequences of this potentially dangerous and persuasive mix of illiberal populist ideas of democracy and alarmist politics of crises.

Online Supplement

Additional supplementary information may be found in the online version of this article.

Online Supplement A: Sampling and weighting

Table SA1. Sample for the manual content analysis

Table SA2. Complete overview of sample for the manual content analysis

Table SA3. Weighting at the account level (incl. dictionary hits)

Table SA4. Population and sample characteristics compared to weighted results

Online Supplement B: Additional information on the operationalization

Table SB1. Original example of codebook instructions for the category homogeneity of the people (in German)

Table SB2. Original examples for populist messages from our sample

Table SB3. Original examples for crisis-related messages from our sample

Table SB4. Intercoder reliability results for all included variables

Online Supplement C: Additional analyses

Figure SC1. Shares of populist, crisis-related, and combined use of populist and crisis-related messages by party

Figure SC2. Share of populist messages by party over time

Figure SC3. Share of crisis-related messages by party over time

Figure SC4. Share of combined use of populist and crisis-related messages by party over time

Figure SC5. Predicted probabilities for populist messages by party for Model I (without crisis messages as predictor) and Model IV (with crisis messages as predictor)

Figure SC6. Predicted probabilities for crisis messages by party for Model II (without populist messages as predictor) and Model V (with populist messages as predictor)

Table SC1. Unadjusted (unadj.) and Bonferroni corrected (Bonf.) p-values for pairwise comparisons between different parties

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.1 MB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (730.4 KB)Acknowledgments

We want to thank the participants of the DGPuK’s political communication section conference 2020 in Mainz (Germany) and the workshop participants of the ‘Democracy and Democratization’ unit at the WZB Berlin Social Science Centre for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. Special thanks go to the colleagues of the project ‘Against Elites, Against Outsiders’ (DIR) and particularly to Heiko Giebler for many constructive ideas throughout the whole research process; to Sven Engesser for providing a codebook, our student coders for collecting the data, Ekpenyong Ani for copyediting, and finally Lisa Zehnter and the reviewers for many helpful remarks on the (pre-)final version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Raw data were generated by accessing text data from Facebook using the statistical software R. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author Benjamin Schürmann on request.

Notes

1 A coding example from the codebook can be found in Online Supplement B, Table SB1. Additionally, we present exemplary messages for populist and crisis-related content for each party in Table SB2/SB3.

2 Due to the populism and crises appearing rarely, we see higher agreement (Holsti = .83 for populism and .86 for crises) and lower chance-adjusted reliability scores (Krippendorff's alpha = .56 for populism and .68 for crises). Following recent recommendations (Riffe et al. Citation2019), we reported Gwet’s AC1 and considered scores above .7 as adequate. We provide more details on intercoder reliability scores in Online Supplement B and Table SB4.

3 We have refrained from using multinominal logistic regression since the underlying assumption that belonging in one category is not related to belonging in another category would be violated in our models (Benson, Kumar, and Tomkins Citation2016).

4 Since almost all of our control variables are scaled dichotomously or categorically, we follow Muller and MacLehose (Citation2014) and use "marginal standardization" for adjusting control variables in computing predicted probabilities. Other than prediction at the means (i.e., setting each cofounder to its mean value), marginal standardization is based on the confounding variables‘ distribution in the dataset.

5 Figure SC1 in the Online Supplement C shows the shares of populist, crisis-related, and combined use of populist and crisis-related messages by party in separate bar plots. Detailed numbers from can be found in Appendix, .

6 To assess the statistical significance of differences between the parties, we ran post-hoc tests for bivariate models (see Online Supplement C, Table SC1).

7 In the Online Supplement, we provide figures mapping the use of all message types by party over time (Figures SC2–4).

8 We also ran post-hoc tests to assess the statistical significance of differences between parties in (see Online Supplement C, Table SC1).

9 However, a reverse argument about the co-occurrence of populism and crisis also seems plausible. One could think of crises as a tool to increase the persuasiveness of populist arguments, which mainly radical parties use. As a robustness check, we ran a final logistic regression Model V (see in Appendix) that follows Model II for explaining crisis messages but controls for populism. Again, the explanatory power of the parties barely varies across the models. More detailed information on Model IV and Model V can be found in the Online Supplement C.

10 Negative campaigning can be briefly defined as a political strategy that addresses negative features or performance of a political opponent in order to win (back) votes (Walter, van der Brug, and van Praag Citation2014).

11 At the state level, the Left is a minor coalition partner in the city-states of Bremen and Berlin. In Thuringia (former GDR), they even hold the office of the Ministerpäsident.

References

- Aalberg, T., F. Esser, C. Reinemann, J. Stromback, and C. H. D. Vreese, eds. 2017. Populist Political Communication in Europe. New York: Routledge.

- Akkerman, A., C. Mudde, and A. Zaslove. 2014. “How Populist Are the People? Measuring Populist Attitudes in Voters.” Comparative Political Studies 47 (9): 1324–1353. doi:10.1177/0010414013512600

- Arzheimer, K. 2015. “The AfD: Finally a Successful Right-Wing Populist Eurosceptic Party for Germany?” West European Politics 38 (3): 535–556. doi:10.1080/01402382.2015.1004230

- Arzheimer, K., and C. C. Berning. 2019. “How the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and Their Voters Veered to the Radical Right, 2013–2017.” Electoral Studies 60: 102040. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.004

- Aslanidis, P. 2018. “Measuring Populist Discourse with Semantic Text Analysis: An Application on Grassroots Populist Mobilization.” Quality & Quantity 52 (3): 1241–1263. doi:10.1007/s11135-017-0517-4

- Barr, R. R. 2009. “Populists, Outsiders and Anti-Establishment Politics.” Party Politics 15 (1): 29–48. doi:10.1177/1354068808097890

- Beisch, V. N., and C. Schäfer. 2020. “Internetnutzung mit Großer Dynamik: Medien, Kommunikation, Social Media.” ARD/ZDF-Onlinestudie 2020: 20.

- Benson, A. R., R. Kumar, and A. Tomkins. 2016. “On the Relevance of Irrelevant Alternatives.” Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on World Wide Web, 963–973. doi:10.1145/2872427.2883025

- Berbuir, N., M. Lewandowsky, and J. Siri. 2015. “The AfD and its Sympathisers: Finally a Right-Wing Populist Movement in Germany?” German Politics 24 (2): 154–178. doi:10.1080/09644008.2014.982546

- Bernhard, L., and H. Kriesi. 2019. “Populism in election times: A comparative analysis of 11 countries in Western Europe.” West European Politics 42 (6): 1–21. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1596694

- Blassnig, S., N. Ernst, F. Büchel, and S. Engesser. 2018. “Populist Communication in Talk Shows and Social Media. A Comparative Content Analysis in Four Countries.” Studies in Communication | Media 7 (3): 338–363. doi:10.5771/2192-4007-2018-3-338

- Blassnig, S., N. Ernst, F. Büchel, S. Engesser, and F. Esser. 2018. “Populism in Online Election Coverage: Analyzing populist statements by politicians, journalists, and readers in three countries.” Journalism Studies 20 (8): 1110–1129. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2018.1487802

- Bos, L., and K. Brants. 2014. “Populist Rhetoric in Politics and Media: A Longitudinal Study of the Netherlands.” European Journal of Communication 29 (6): 703–719. doi:10.1177/0267323114545709

- Brubaker, R. 2017. “Why Populism?” Theory and Society 46 (5): 357–385. doi:10.1007/s11186-017-9301-7

- Canovan, M. 1999. “Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy.” Political Studies 47 (1): 2–16. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.00184

- Caramani, D. 2017. “Will vs. Reason: The Populist and Technocratic Forms of Political Representation and Their Critique to Party Government.” American Political Science Review 111 (1): 54–67. doi:10.1017/S0003055416000538

- Castanho Silva, B., S. Jungkunz, M. Helbling, and L. Littvay. 2020. “An Empirical Comparison of Seven Populist Attitudes Scales.” Political Research Quarterly 73 (2): 409–424. doi:10.1177/1065912919833176

- Chadwick, A. 2017. The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power (Second Edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Engesser, S., N. Ernst, F. Esser, and F. Büchel. 2017. “Populism and Social Media: How Politicians Spread a Fragmented Ideology.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (8): 1109–1126. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2016.1207697

- Engesser, S., N. Fawzi, and A. O. Larsson. 2017. “Populist Online Communication: Introduction to the Special Issue.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (9): 1279–1292. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2017.1328525

- Ernst, N., S. Blassnig, S. Engesser, F. Büchel, and F. Esser. 2019. “Populists Prefer Social Media Over Talk Shows: An Analysis of Populist Messages and Stylistic Elements Across Six Countries.” Social Media + Society 5 (1). doi:10.1177/2056305118823358

- Ernst, N., S. Engesser, F. Büchel, S. Blassnig, and F. Esser. 2017. “Extreme Parties and Populism: An Analysis of Facebook and Twitter Across six Countries.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (9): 1347–1364. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2017.1329333

- Freedman, P., and K. Goldstein. 1999. “Measuring Media Exposure and the Effects of Negative Campaign Ads.” American Journal of Political Science 43 (4): 1189–1208. doi:10.2307/2991823

- Gest, J., T. Reny, and J. Mayer. 2018. “Roots of the Radical Right: Nostalgic Deprivation in the United States and Britain.” Comparative Political Studies 51 (13): 1694–1719. doi:10.1177/0010414017720705

- Giebler, H., M. Hirsch, B. Schürmann, and S. Veit. 2020. “Discontent With What? Linking Self-Centered and Society-Centered Discontent to Populist Party Support.” Political Studies 69 (4): 1–21. doi:10.1177/0032321720932115 .

- Groshek, J., and K. Koc-Michalska. 2017. “Helping Populism win? Social Media use, Filter Bubbles, and Support for Populist Presidential Candidates in the 2016 US Election Campaign.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (9): 1389–1407. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2017.1329334

- Gründl, J. 2020. “Populist ideas on social media: A dictionary-based measurement of populist communication.” New Media & Society, 641–659. doi:10.1177/1461444820976970

- Guasti, P. 2020. “Populism in Power and Democracy: Democratic Decay and Resilience in the Czech Republic (2013–2020).” Politics and Governance 8 (4): 473–484. doi:10.17645/pag.v8i4.3420 .

- Hawkins, K. A., R. E. Carlin, L. Littvay, and C. R. Kaltwasser, eds. 2018. The Ideational Approach to Populism: Concept, Theory, and Analysis. New York: Routledge.

- Healy, A., and N. Malhotra. 2013. “Retrospective Voting Reconsidered.” Annual Review of Political Science 16: 285–306. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-032211-212920

- Hobolt, S. B., and J. Tilley. 2016. “Fleeing the Centre: The Rise of Challenger Parties in the Aftermath of the Euro Crisis.” West European Politics 39 (5): 971–991. doi:10.1080/01402382.2016.1181871

- Inglehart, R., and P. Norris. 2017. “Trump and the populist authoritarian parties: The silent revolution in reverse.” Perspectives on Politics 15 (2): 443–454. doi:10.1017/S1537592717000111 .

- Jagers, J., and S. Walgrave. 2007. “Populism as Political Communication Style: An Empirical Study of Political Parties’ Discourse in Belgium.” European Journal of Political Research 46 (3): 319–345. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00690.x

- Jungherr, A., R. Schroeder, and S. Stier. 2019. “Digital Media and the Surge of Political Outsiders: Explaining the Success of Political Challengers in the United States, Germany, and China.” Social Media + Society 5 (3): 1–12. doi:10.1177/2056305119875439 .

- Kaltwasser, C. R. 2012. “The Ambivalence of Populism: Threat and Corrective for Democracy.” Democratization 19 (2): 184–208. doi:10.1080/13510347.2011.572619

- Kim, S. 2017. “The populism of the Alternative for Germany (AfD): An extended Essex School perspective.” Palgrave Communications 3 (1): 5. doi:10.1057/s41599-017-0008-1

- Kim, S. 2021. “ … Because the homeland cannot be in opposition: Analysing the discourses of Fidesz and Law and Justice (PiS) from opposition to power.” East European Politics 37 (2): 332–351. doi:10.1080/21599165.2020.1791094

- Koselleck, R., and M. W. Richter. 2006. “Crisis.” Journal of the History of Ideas 67 (2): 357–400. doi:10.1353/jhi.2006.0013 .

- Krause, W., and A. Wagner. 2019. “Becoming part of the gang? Established and nonestablished populist parties and the role of external efficacy.” Party Politics 27 (1): 161–173. doi:10.1177/1354068819839210 .

- Kriesi, H., E. Grande, R. Lachat, M. Dolezal, S. Bornschier, and T. Frey, eds. 2006. “Globalization and the Transformation of the National Political Space: Six European Countries Compared.” European Journal of Political Research 45 (6): 921–956. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00644.x

- Kriesi, H., T. S. Pappas, H. Kriesi, and T. S. Pappas, eds. 2015. “Populism in Europe During Crisis: An Introduction.” In European Populism in the Shadow of the Great Recession, 1–19. ECPR Press.

- Laclau, E. 2005. “Populism. What’s in a Name?” In Populism and the Mirror of Democracy (First Printing Edition, edited by F. Panizza, 32–49. London: Verso.

- Lau, R. R., and I. B. Rovner. 2009. “Negative Campaigning.” Annual Review of Political Science 12 (1): 285–306. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.071905.101448

- Lewandowsky, M., H. Giebler, and A. Wagner. 2016. “Rechtspopulismus in Deutschland. Eine Empirische Einordnung der Parteien zur Bundestagswahl 2013 Unter Besonderer Berücksichtigung der AfD.” Politische Vierteljahresschrift 57 (2): 247–275. doi:10.5771/0032-3470-2016-2-247

- March, L. 2017. “Left and Right Populism Compared: The British Case.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 19 (2): 282–303. doi:10.1177/1369148117701753

- Mazzoleni, G. 2008. “Populism and the Media.” In Twenty-first Century Populism: The Spectre of Western European Democracy, edited by D. Albertazzi and D. McDonell, 49–64. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- McDonnell, D., and J. L. Newell. 2011. “Outsider Parties in Government in Western Europe.” Party Politics 17 (4): 443–452. doi:10.1177/1354068811400517

- Y. Mény, and Y. Surel. 2002. “The Constitutive Ambiguity of Populism.” In Democracies and the Populist Challenge, edited by Y. Mény and Y. Surel. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Moffitt, B. 2015. “How to Perform Crisis: A Model for Understanding the Key Role of Crisis in Contemporary Populism.” Government and Opposition 50 (02): 189–217. doi:10.1017/gov.2014.13

- Moffitt, B. 2016. The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Mols, F., and J. Jetten. 2016. “Explaining the Appeal of Populist Right-Wing Parties in Times of Economic Prosperity: Economic Prosperity and Populist Right-Wing Parties.” Political Psychology 37 (2): 275–292. doi:10.1111/pops.12258

- Mouffe, C. 2005. “The “End of Politics” and the Challenge of Right-Wing Populism.” In Populism and the Mirror of Democracy (First Printing Edition), edited by F. Panizza, 50–71. London/New York: Verso.

- Mudde, C. 2004. “The Populist Zeitgeist.” Government and Opposition 39 (4): 541–563. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

- Mudde, C., and C. R. Kaltwasser. 2018. “Studying Populism in Comparative Perspective: Reflections on the Contemporary and Future Research Agenda.” Comparative Political Studies 51 (13): 1667–1693. doi:10.1177/0010414018789490..

- Mudde, C., and C. Rovira Kaltwasser. 2013. “Exclusionary vs. Inclusionary Populism: Comparing Contemporary Europe and Latin America.” Government and Opposition 48 (02): 147–174. doi:10.1017/gov.2012.11

- Müller, J.-W. 2017. “Was ist Populismus?” Zeitschrift Für Politische Theorie 7 (2): 187–201. doi:10.3224/zpth.v7i2.03

- Muller, C. J., and R. F. MacLehose. 2014. “Estimating Predicted Probabilities from Logistic Regression: Different Methods Correspond to Different Target Populations.” International Journal of Epidemiology 43 (3): 962–970. doi:10.1093/ije/dyu029

- Pauwels, T. 2017. “Measuring Populism: A Review of Current Approaches.” In Political Populism, edited by R. C. Heinisch, C. Holtz-Bacha, and O. Mazzoleni, 123–136. Baden-Baden: Nomos. doi:10.5771/9783845271491-123 .

- Petrarca, C. S., H. Giebler, and B. Weßels. 2020. “Support for Insider Parties: The Role of Political Trust in a Longitudinal-Comparative Perspective.” Party Politics. doi:10.1177/1354068820976920

- Riffe, D., S. Lacy, B. R. Watson, and F. Fico. 2019. Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research. 4th ed. New York: Routledge.

- Rippl, S., and C. Seipel. 2018. “Modernisierungsverlierer, Cultural Backlash, Postdemokratie: Was erklärt rechtspopulistische Orientierungen?” KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 70 (2): 237–254. doi:10.1007/s11577-018-0522-1

- Rone, J. 2021. “Far Right Alternative News Media as ‘Indignation Mobilization Mechanisms’: How the far Right Opposed the Global Compact for Migration.” Information, Communication & Society, 1–18. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2020.1864001

- Rooduijn, M. 2014. “The Nucleus of Populism: In Search of the Lowest Common Denominator.” Government and Opposition 49 (4): 573–599. doi:10.1017/gov.2013.30

- Rooduijn, M., and T. Akkerman. 2017. “Flank attacks: Populism and left-right radicalism in Western Europe.” Party Politics 23 (3): 193–204. doi:10.1177/1354068815596514

- Rooduijn, M., and B. Burgoon. 2018. “The Paradox of Well-Being: Do Unfavorable Socioeconomic and Sociocultural Contexts Deepen or Dampen Radical Left and Right Voting Among the Less Well-Off?” Comparative Political Studies 51 (13): 1720–1753. doi:10.1177/0010414017720707

- Rooduijn, M., and T. Pauwels. 2011. “Measuring Populism: Comparing Two Methods of Content Analysis.” West European Politics 34 (6): 1272–1283. doi:10.1080/01402382.2011.616665

- Rooduijn, M., S. van Kessel, C. Froio, A. Pirro, S. L. de Lange, D. Halikiopoulou, P. Lewis, C. Mudde, and P. Taggart. 2019. The PopuList: An Overview of Populist, Far Right, Far Left and Eurosceptic Parties in Europe. http://www.popu-list.org

- Schmuck, D., and M. Hameleers. 2019. “Closer to the people: A comparative content analysis of populist communication on social networking sites in pre- and post-Election periods.” Information, Communication & Society 23 (10): 1–18. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2019.1588909.

- Schulz, A., P. Müller, C. Schemer, D. S. Wirz, M. Wettstein, and W. Wirth. 2017. “Measuring Populist Attitudes on Three Dimensions.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 30 (2): 316–326. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edw037

- Schwemmer, C. 2021. “The Limited Influence of Right-Wing Movements on Social Media User Engagement. Social Media + Society 7 (3): 1–13. doi:10.1177/20563051211041650

- Serrano, J. C. M., M. Shahrezaye, O. Papakyriakopoulos, and S. Hegelich. 2019. “The rise of Germany’s AfD: A social media analysis.” Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Social Media and Society, 214–223. doi:10.1145/3328529.3328562

- Song, H., P. Tolochko, J.-M. Eberl, O. Eisele, E. Greussing, T. Heidenreich, F. Lind, S. Galyga, and H. G. Boomgaarden. 2020. “In Validations We Trust? The Impact of Imperfect Human Annotations as a Gold Standard on the Quality of Validation of Automated Content Analysis.” Political Communication 37 (4): 1–23. doi:10.1080/10584609.2020.1723752.

- Spieß, E., D. Frieß, and A. Schulz. 2020. “Populismus auf Facebook: Ein explorativer Vergleich der Parteien- und Anschlusskommunikation von AfD, CDU und SPD.” Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft 30: 219–240. doi:10.1007/s41358-020-00221-8

- Spruyt, B., G. Keppens, and F. Van Droogenbroeck. 2016. “Who supports populism and what attracts people to it?” Political Research Quarterly 69 (2): 335–346. doi:10.1177/1065912916639138

- Stier, S., A. Bleier, H. Lietz, and M. Strohmaier. 2018. “Election Campaigning on Social Media: Politicians, Audiences, and the Mediation of Political Communication on Facebook and Twitter.” Political Communication 35 (1): 50–74. doi:10.1080/10584609.2017.1334728

- Stier, S., L. Posch, A. Bleier, and M. Strohmaier. 2017. “When Populists Become Popular: Comparing Facebook use by the Right-Wing Movement Pegida and German Political Parties.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (9): 1365–1388. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2017.1328519

- Taggart, P. 2004. “Populism and Representative Politics in Contemporary Europe.” Journal of Political Ideologies 9 (3): 269–288. doi:10.1080/1356931042000263528

- van der Bles, A. M., T. Postmes, and R. R. Meijer. 2015. “Understanding collective discontents: A psychological approach to measuring zeitgeist.” PloS One 10 (6): 1–26. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0130100 .

- van de Wardt, M., C. E. De Vries, and S. B. Hobolt. 2014. “Exploiting the Cracks: Wedge Issues in Multiparty Competition.” The Journal of Politics 76 (4): 986–999. doi:10.1017/S0022381614000565

- van Kessel, S. 2015. Populist Parties in Europe: Agents of Discontent?. London: Palgrave Macmilan.