Abstract

Teaching the scientific, historical, and social facets of global climate change, its causes, and inequitable impacts presents a challenge to most K–12 teachers. In this article we describe the design and implementation of a yearlong professional learning program created to support urban, public K–12 teachers in the creation and enactment of Justice-Centered Climate Change Pedagogy (JCCCP) while developing a long-term teacher learning community. The program, “Oakland Teachers Advancing Climate Action” (OTACA) is now in its fourth iteration in a major West Coast city. Here, we present the conceptual framework of JCCCP used to design the program; our approach to the professional development framework for supporting teachers in their collective development of JCCCP; and examples of JCCCP and our professional learning program in practice, along with commentary on the strengths and challenges of our design as well as its transferability across contexts. This article can serve as a guide for researchers and practitioners who want to support teachers as they develop teaching practices focused on addressing climate (in)justice in their classrooms.

The inextricabilities of climate change and environmental racism (United Nations, Human Rights Council Citation2019) create a socio-spatial landscape in which BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) communities bear a disproportionate burden of environmental harms and their associated effects on health and well-being (e.g., Lane et al. Citation2022). The pervasive racial and material injustices that characterize our social and physical environments broadly (Robinson Citation1983) also shape widespread inequalities in public education (see Morales-Doyle Citation2017). Given this, addressing climate change and its social impacts in K–12 classrooms is an urgent task for schools and educators across the United States (Morales-Doyle Citation2017).

Despite the urgent need for teaching, learning, and action focused on disrupting the climate crisis, climate change is not consistently taught in U.S. classrooms (Plutzer et al. Citation2016). When it is, the content is often introduced as “unsettled” or inconclusive (Plutzer et al. Citation2016), and the bulk of pedagogical approaches are typically focused on understanding its “scientific” (rather than social or political) causes and consequences (Clark, Sandoval, and Kawasaki Citation2020). Even when climate-focused social actions are incorporated into the curriculum, the practices in focus are typically more individualized (i.e., recycling more) than collective or political and are generally not centered on environmental justice (Busch et al. Citation2019; Clark, Sandoval, and Kawasaki Citation2020; Damico, Baildon, and Panos Citation2020).

To address these shortcomings, educators must continue to develop teaching and learning practices oriented specifically toward what we call “Justice-Centered Climate Change Pedagogy” (JCCCP), a climate change–specific adaptation of Morales-Doyle’s (Citation2017) “justice-centered science pedagogy.” Morales-Doyle’s framework, which we extend to focus specifically on climate change, seeks to “[address] inequity in science education as one component of oppression by challenging larger structures” (Morales-Doyle Citation2017, 1035), such as links between white supremacy and the built environment in cities. In this we must also work collectively and in community, given the myriad challenges that individual teachers working to develop JCCCP may face: a general misalignment between Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) and justice-centered science pedagogy generally (Morales-Doyle, Price, and Chappell Citation2019), a lack of appropriate existing curriculum (Plutzer et al. Citation2016), and gaps in the content knowledge and local knowledge needed to feel confident in developing such curriculum themselves.

In this article we describe the design and implementation of a yearlong professional learning program created to support urban, public K–12 teachers in the creation and enactment of JCCCP while developing a long-term learning and practice community. The program, “Oakland Teachers Advancing Climate Action” (OTACA), is now in its fourth iteration. In the following three sections, we present

a conceptual framework for approaching the design of JCCCP;

a professional development framework for supporting teachers in their collective development of JCCCP; and

examples of JCCCP and our professional learning program in practice, along with commentary on the strengths and challenges of our design as well as its transferability across contexts.

This article can serve as a guide for researchers and practitioners who want to support teachers as they develop teaching practices focused on addressing climate (in)justice in their classrooms.

OTACA origins

OTACA was cofounded by the Environmental Justice Caucus (EJC) of the Oakland Education Association (OEA)—Oakland’s teachers’ union—and graduate students from UC Berkeley. Oakland Unified School District (OUSD) is a medium-size urban district with 83 preK–12 schools serving nearly 35,000 students, many of whom live in communities most impacted by climate injustice. In 2022–2023, district students were 22% African American, 44% Latino, 12% Asian, 6% multiethnic, and 11% white. Over 50% of students speak a language other than English at home, and 71% of students receive free or reduced lunch.

The OEA EJC was formed in 2016 by a group of OUSD teachers who kept running into one another at local environmental and racial justice protests. They felt a collective urgency to focus on climate justice in their classrooms and met monthly, often in members’ classrooms or living rooms, to share teaching resources and local environmental justice news. From 2017 to 2019, the group collaborated with OUSD high school youth and other environmental advocacy organizations in OUSD, resulting in a 2019 OUSD Board Policy on Environmental and Climate Change Literacy (ECCL) and the formation of an ECCL working group amongst school district staff. However, since the passage of the 2019 board policy, only a few district-led supports for teachers have materialized, and none have had longitudinal structure (i.e., beyond a one-off event).

Wanting more support for themselves and fellow teachers to develop as local climate justice experts with the capacity to teach climate in justice-centered ways, EJC (with authors Fitzmaurice and Barton) created and began to facilitate the OUSD Teachers Advancing Climate Action (OTACA) program. OTACA is focused on supporting OUSD teachers in designing and implementing justice-centered, place-based, student-led projects that critically investigate the scientific and social phenomena that shape the climate crisis and environmental injustice. This program has supported more than 70 OUSD teachers, many of whom have participated in the program for multiple years. Participants have included classroom teachers in OUSD and neighboring districts across all grade levels and subjects, in addition to other school-based educators such as English language development (ELD) or special education pull-out teachers, librarians, garden teachers, and retired classroom teachers currently substitute teaching in the district.

Guiding principles

Central to OTACA are two guiding principles. First, teaching and learning focused on addressing the climate crisis must be justice-centered and action-oriented to address its basis in—and consequences for—ongoing environmental racism (thus the need for JCCCP). Second, programs like OTACA can greatly support teachers’ design and implementation of JCCCP by structuring collective, collaborative, and continuous opportunities for teachers to learn and act with their communities toward climate justice. This ongoing, community-situated work can thereby support teachers’ development as “transformative intellectuals” (Giroux Citation1988), which we describe in greater detail below.

Justice-centered climate change pedagogy

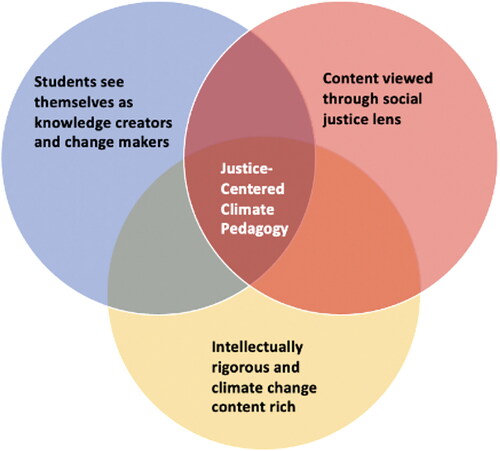

JCCCP is directly inspired by and adapted from Morales-Doyle’s (Citation2017) Justice Centered Science Pedagogy, and for us is composed of three primary elements (see ). First, JCCCP must be intellectually rigorous, meaning that it invites students to expand and/or evaluate their existing knowledge(s) by developing new and nuanced climate-related knowledge(s) and analytical skills. To be intellectually rigorous, JCCCP must be grounded in local climate change content that emerges from students’ lives and community experiences. Engaging with such locally situated issues can support students’ abilities to synthesize and create new knowledge(s), and develop practices that lead to justice-oriented change.

Second, as in our experiences with teachers and Morales-Doyle’s (Citation2017) framing, the work of JCCCP must be approached critically, in ways that “emphasize the centrality of race and racism, gender and sexism, and the economic exploitation of capitalism in structuring society and schools” (Morales-Doyle Citation2017). For us, these critical approaches should synthesize perspectives on relationships between space, place, and power from across multiple subjects, giving students opportunities to apply critical theories of power and self to the environmental data they collect and analyze (e.g., Damico, Baildon, and Panos Citation2020).

Finally, JCCCP should be characterized by students’ ongoing development as knowledge creators and change-makers. We understand self-perception as a knowledge creator to include both “epistemic agency” (Stroupe Citation2014), defined as students’ agency in shaping relevant knowledge, and “epistemic affect” (Jaber and Hammer Citation2016), or their feelings and reactions related to knowledge creation. We understand self-perception as a change-maker as largely analogous to self-perception as a knowledge creator, the key difference being a focus on direct local action rather than local knowledge. Supporting students’ continued growth as change-makers includes creating conditions to support both their local, climate-related agency and their affective relationships to local environmental work.

Teachers as transformative intellectuals

Based on our experiences in the classroom, working with teachers and engaging with literature around justice-centered teaching (e.g., Giroux Citation1988; Morales-Doyle Citation2017), we hold that teachers can most effectively design and implement JCCCP as they become transformative intellectuals: educators who—in the context of their communities—question knowledge, social structures, and the relationship between the two (Giroux Citation1988). This understanding parallels Morales-Doyle’s (Citation2017) particularly rich description of the importance of students’ development as transformative intellectuals in justice-centered learning environments.

In practice—and to develop as transformative intellectuals in the realm of climate justice—teachers must develop familiarity and fluency with a range of historical, scientific, and experiential knowledges. These might include, for example, the environmental issues most pressing in their students’ neighborhoods, the historical and contemporary structures that shape environmental racism across their cities, and work with community experts (environmental justice advocates, scientists, city officials) as their students explore and act. They must also be equipped to dynamically respond to their students’ affective experiences with environmental racism, and to support their development as knowledge-creators and change-makers themselves.

Such expertise takes time and support to develop and forms part of an ongoing learning process in an ever-shifting landscape of environmental racism (e.g., local victories, new threats), local climate impacts (e.g., a season of particularly bad wildfires or drought), and opportunities for youth participation (e.g., climate strikes, public meetings). In this endeavor, educators need each other: as informational resources, as brainstorming and planning partners, as design and/or teaching collaborators, and as emotional support.

Program pedagogical supports and structure

Both the subject matter content and the programmatic structure of OTACA are organized around the two guiding principles described above.

Content and curricular supports

Delivered throughout the academic year, OTACA workshops are designed to support teachers in

developing climate justice action research projects with their students, and

becoming expert resources in local climate justice knowledge, fundamentally through direct connections with local organizations and experts working toward climate justice.

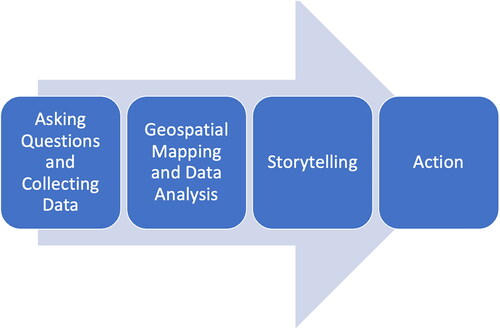

Regardless of grade level and content, OTACA participating teachers work to design and implement student action projects guided by the OTACA Project Template (). This template aims to connect students to both the research and analysis process and the importance of civic engagement. Although teachers are encouraged to adapt this progression to their students’ particular contexts, the template we present in OTACA workshops is composed of four explicit steps:

developing critical questions and data collection plans;

using geospatial mapping and data analysis (this is the analytical “tool” we spend the most time workshopping with teachers);

communicating and telling stories both with and about that data (following Wilkerson et al. Citation2021); and

proposing and taking actions based on findings.

Through OTACA workshops, we engage teachers in each part of this process: collecting and examining local data themselves, mapping out the environmental hazards and assets in their schools’ neighborhoods, telling their own climate justice stories, and imagining a better future for their students. Although mapping is only named as one “step” in our project template, we encourage teachers to engage spatial justice (Soja Citation2010) approaches with their students throughout the project. In our workshops, we support teachers in this process by using maps to guide data collection and analysis work, by creating maps that serve as storytelling and analysis tools, and by applying a critical lens to existing mapped data (including evaluating the purposes for which a given map was made and the effects of the authors’ biases on the stories the map tells).

OTACA is also focused on developing connections between teachers and local climate justice experts and practitioners. To do this, OTACA collaboratively hosts workshops with local environmental justice advocates, community organizers, local officials, and scientists working on a wide range of local climate justice issues (e.g., food justice, air quality, our city’s climate action plan). Beyond connections through workshops, the OTACA planning team have also facilitated classroom-level partnerships between participating teachers and these various local partners.

Structure to build teacher community

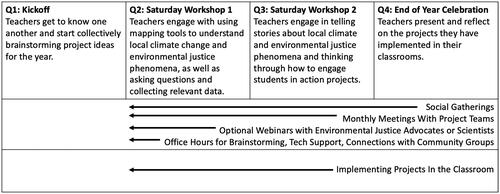

The programmatic structure of OTACA () is designed to build long-term teacher community. Each year all OTACA teachers participate in a Kick-Off event, two full-day Saturday workshops, and an End of Year Celebration. The workshops address both pedagogical practices and curricular content related to local climate issues, and include presentations by local experts. In addition to these programwide workshops, teachers participate in small (3–6 people) project teams that meet roughly once a month. These project teams are typically composed of teachers focusing on a specific topic or supporting students in similar grades or subject areas. Examples of past teams include “Air Quality,” “Habitats at Home,” and “Food Justice.” The End of Year Celebration in May is part poster-session, part structured reflection during which teachers share their work, reflect on their projects, and learn from other projects designed and implemented by other participants.

In addition to the four main events and smaller project team meetings, OTACA participants are supported via weekly office hours, optional Zoom webinars by climate and environmental justice experts, connections to local environmental justice advocates or scientists, reimbursements for small classroom purchases, optional social events, and (grant-funded) stipends. End-of-year surveys and interviews with teachers indicate that most have felt a sense of community with other teachers in the group, and many participants have joined OTACA for several years in a row, becoming project team leaders, sharing past years’ projects at workshops, and presenting their OTACA-related work at teaching conferences.

OTACA’s classroom impact

Because of the wide range of contexts in which OTACA educators teach and as a result of our own experiences using prescribed curricula as teachers, OTACA planners have thus far encouraged participating teachers to pursue an open-ended set of projects and modalities in their classrooms. As a result, teachers have designed a wide range of classroom experiences through the program. One high school class used demographic and visually collected data to plan a tree-planting project for a local environmental nonprofit. Another fifth-grade class gathered stories about contemporary indigenous communities’ environmental justice work and drew on those narratives to make recommendations on local issues. Below, we describe two themes that highlight ways in which OTACA teachers brought their learning and collaborations with one another into their classrooms: “mapping for justice,” and “living as a part of nature within our city.”

Mapping for justice

“Justice,” Edward Soja writes, “has a consequential geography, a spatial expression that is more than just a background reflection or set of physical attributes to be descriptively mapped” (Citation2010). The spatial expression of (in)justice is precisely the field of inquiry and action in which OTACA aims to engage teachers and students through analysis of maps and engagement in mapmaking. This has two key components:

a place-based exploration of the ways in which environmental racism is inscribed in the built environment and lived experiences of it, and

a collective engagement in actions that can support a reimagined vision of/for public space.

Maps and mapmaking can help support nuanced understanding(s) of the spatialization of structural oppression (e.g., Rubel, Hall-Wieckert, and Lim Citation2017; see also Lane et al. Citation2022). As we have seen throughout our work with OTACA, maps can also serve as dynamically critical storytelling tools for students in K–12 classrooms. Maps, broadly speaking, have served teachers and students as a cohesive tool for inquiry and data collection, data analysis and visualization, and storytelling about local and consequential places.

Working together in programwide workshops and then in their classrooms, OTACA teachers have engaged maps and mapmaking practices in a range of ways. For the past two years, our second Saturday workshop has included sessions on “Mapping for Justice,” one led by a local environmental advocate and organizer and another led by a program facilitator. At the first workshop, teachers used web-based, interactive mapping tools to explore environmental justice issues in Oakland. Then, depending on grade level and area of interest, teachers participated in 1–3 subsequent workshops in which they engaged with specific mapping methods or map-related storytelling tools (e.g., hand-drawn maps, re-populating existing maps through new data collection, Google MyMaps, ArcGIS Online, StoryMaps), as well as conversations around engaging with maps by asking critical questions.

One high school teacher’s experiences with this mapping work illustrate the possibilities and potentials of this approach. In an integrated unit between this teacher’s Ethnic Studies class, a math class, and a science class, they organized students into working groups focusing on the spatial distribution of local pollutants. Because the school was composed of students from a wide range of city neighborhoods, a wide range of lived experiences emerged in students’ conversations about the data and their relationships to it. The maps in particular made these differences—and their spatial distribution—readily apparent. The teacher reflected:

I have done something like this before, but this was one that I think was so meaningful because it applied to students’ lives… You can see the impact directly, and the learning that took place was like, in your face…versus what I think we had done in the past before was, just taking data from one place to another place, and then learning about the history, wasn’t asked to connect it to their personal [lives]… But this was, I mean, it was powerful.

Even in our city we are a part of nature

Environmental education initiatives for urban students are often focused on connecting students to nature by bringing them into pristine wilderness areas. However, an emphasis on this type of activity as students’ only connection to nature through formal education can be highly detrimental as it communicates that they and their cities exist separately from nature, and implies that environmental learning cannot happen at home or at school. Pushing against this notion that students and cities exist separately from nature, several OTACA teachers focused on helping students notice, interact with, steward, advocate for, and understand that they are a part of the natural world within our city.

The first year of OTACA was, for most teachers, completely remote and characterized by the challenges of the pandemic. Teachers of older students in particular commented on the effects of remote learning on students’ mental health. To combat this, one high school teacher designed his OTACA project to facilitate students’ interactions with the natural world around them. Through the project, students were given small challenges each week (e.g., spend 10 minutes with a tree). After completing the challenge, students recorded noticings, wonderings, and hopes, both about nature and about themselves, and later discussed their experiences in small Zoom breakout rooms, sharing pictures and videos in discussing their experiences. As part of the assignment, students spent time outside thinking by themselves, took walks with family members, and appreciated and recorded small changes in weather and the plants around them. Students reported enjoying the check-ins with each other and the project as a whole, especially getting away from their computer screens.

Several other teachers engaged students in stewarding and supporting natural spaces within our community. For example, a group of seven elementary school teachers collaborated on a project that they named “Habitats at Home.” After collecting data on and mapping pollinator plants in their neighborhoods and/or schoolyards, students engaged in a milkweed planting project to plant native milkweed in their yards, neighborhoods, and schoolyards. In addition, two school gardens grew out of teachers’ OTACA projects.

Beyond student learning and engagement with natural spaces in our city, teachers who engaged their students with projects on this theme reported a particularly strong sense of teacher community and personal learning. For example, one of the school gardens that was revived as part of an OTACA project resulted in a teacher text chain, as teachers met with one another on weekends and during the summer to maintain the garden. Another teacher reported that learning about native and invasive milkweeds as part of the habitats at home project led her to make changes to her own garden at home. Although she told us “I don’t know how much I’m getting out of it v. the kids,” part of our focus has been on helping teachers develop their own practices and knowledges in the process of transforming their teaching and their students’ experiences.

Strengths, challenges, and portable program components

While OTACA was designed in relation to meet the needs of OUSD teachers and students, we are confident that much from the programmatic structure could be adapted to work in other districts.

First, at the level of content and classroom practice, OTACA’s focus on using geospatial tools as “anchors” for planning data collection, analyzing and telling stories about that data, and planning resulting actions could be broadly applicable to school- and district-level professional learning efforts. Teachers certainly benefit from structured and locally contextualized learning support in using these tools, but the tools themselves—and the classroom-level pedagogical structures that teachers have been building around them—are largely free, digitally accessible, and relevant to any number of curricular goals and content areas. One teacher described how the literality of maps—especially as they represent abstract phenomena—helps students understand the scale, scope, and nature of (in)justice(s) in the places they call home.

Second, the programmatic focus on developing teacher community, growth, and sustainability over multiple years has been a critical aspect of OTACA and something that could transfer well across contexts. Structurally, OTACA has benefited from the consistency of its facilitator team and the consistency of funding for which program facilitators have applied (entirely from non-district sources). This has been complemented by a handful of teachers’ participation across multiple program years (including two who began their participation as student teachers in OUSD). Many of these teachers grew over time in their participation level: starting as participants, becoming project team facilitators, and presenting their projects to other OTACA teachers and then at statewide educator conferences. These structural features have supported OTACA’s pedagogical emphasis on building a long-term community of practitioners. This community of practice, we hope, will be durable and continue to expand beyond the program itself.

Third, OTACA’s focus on recruiting participants across the district has been both a challenge and a factor critical to the strength of the program. As of this year’s iteration, teachers at 15% of the district’s 85 schools have participated in the program. Broadening participation across the district, which will continue to be a goal and area of growth for OTACA moving forward, is highly applicable to longitudinal PD programs everywhere. Having teachers from a range of school sites has unquestionably made a difference in the richness and rigor of the professional learning opportunities we’ve facilitated.

Finally, the iterative and flexible nature of the program has allowed us to improve and change the program based on teacher needs and local events. As we continue OTACA into its fourth year, the program continues to evolve in response to the challenges and opportunities that the organizing team has observed directly or those we have learned about through teacher surveys and interviews. For example, we have found that while teachers at school sites with more than one participant have been able to build institutional momentum and support in their school communities, such momentum is far more difficult for teachers working “alone” at their school sites, who benefit from more frequent one-on-one check-ins with OTACA organizers.

Furthermore, developing workshops, tools, and techniques that are relevant and applicable to teachers across all the grade levels we serve has been an ongoing learning opportunity for the leadership team. While particularities of their classroom contexts require different approaches from a professional learning perspective, both kindergarten and 12th-grade physics teachers (for example) share certain unifying principles that bring them to this work; they can learn from one another in ways the planning team did not anticipate. Finally, like teachers everywhere, OUSD teachers have overwhelming demands on their time, energy, and resources. The heterogeneity of schools in the district means that some teachers have greater demands and fewer institutional resources to draw upon than others. Moving forward, we hope to strengthen our support for such teachers (and all participants generally) by holding programming during the summer, a time during which teachers with greater demands are less likely to feel overwhelmed by the particularities of their teaching experiences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Busch, K. C., N. Ardoin, D. Gruehn, and K. Stevenson. 2019. “Exploring a Theoretical Model of Climate Change Action for Youth.” International Journal of Science Education 41 (17): 2389–2409.

- Clark, H. F., W. A. Sandoval, and J. N. Kawasaki. 2020. “Teachers’ Uptake of Problematic Assumptions of Climate Change in the NGSS.” Environmental Education Research 26 (8): 1177–1192.

- Damico, J. S., M. Baildon, and A. Panos. 2020. “Climate Justice Literacy: Stories‐We‐Live‐by, Ecolinguistics, and Classroom Practice.” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 63 (6): 683–691.

- Giroux, H. A. 1988. Teachers as Intellectuals: Toward a Critical Pedagogy of Learning. South Hadley, MA: Bergin Garvey.

- Jaber, L. Z., and D. Hammer. 2016. “Learning to Feel Like a Scientist.” Science Education 100 (2): 189–220.

- Lane, H. M., R. Morello-Frosch, J. D. Marshall, and J. S. Apte. 2022. “Historical Redlining is Associated with Present-Day Air Pollution Disparities in US Cities.” Environmental Science & Technology Letters 9 (4): 345–350.

- Morales-Doyle, D. 2017. “Justice‐Centered Science Pedagogy: A Catalyst for Academic Achievement and Social Transformation.” Science Education 101 (6): 1034–1060.

- Morales-Doyle, D., T. C. Price, and M. J. Chappell. 2019. “Chemicals Are Contaminants Too: Teaching Appreciation and Critique of Science in the Era of Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS).” Science Education 103 (6): 1347–1366.

- Plutzer, E., A. L. Hannah, J. Rosenau, M. McCaffrey, M. Berbeco, and A. H. Reid. 2016. Mixed Messages: How Climate Change Is Taught in America’s Public Schools. Oakland, CA: National Center for Science Education. https://ncse.ngo/files/MixedMessagesReport.pdf

- Robinson, C. J. 1983. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press.

- Rubel, L. H., M. Hall-Wieckert, and V. Y. Lim. 2017. “Making Space for Place: Mapping Tools and Practices to Teach for Spatial Justice.” Journal of the Learning Sciences 26 (4): 643–687.

- Soja, E. W. 2010. Seeking Spatial Justice. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Stroupe, D. 2014. “Examining Classroom Science Practice Communities: How Teachers and Students Negotiate Epistemic Agency and Learn Science-as-Practice.” Science Education 98 (3): 487–516.

- United Nations, Human Rights Council. 2019. “41st Session.” U.N. Doc A/HRC/41/39 (July 17 Climate Change and Poverty: Report of the Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights.) April 10, 2024. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3810720/files/A_HRC_41_39-EN.pdf?ln=en

- Wilkerson, M., W. Finzer, T. Erickson, and D. Hernandez. 2021, June. “Reflective Data Storytelling for Youth: The CODAP Story Builder.” In Proceedings of the 20th Annual ACM Interaction Design and Children Conference, 503–507. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3459990