Abstract

Consultation may have the potential to be an effective mechanism of collaborative governance but only insofar as it is empowered. Empowerment in this context means that consultations are characterized by a degree of decision-making power or, at least, the power to directly influence decisions. This potential for empowered consultation is far from realized in policy processes. Not only is it a long road to consultations that go beyond merely justifying elites’ decisions, but there is even further to go toward entrenching empowered consultation in the formulation and implementation of public policy. In this paper, we identify categories of consultation, including their features and their ends, ranging from the disempowered to the empowered. We also make a normative argument for empowered consultation, while articulating the limitations of this mechanism.

1. Introduction

Can governments’ attempts at public consultations ever be collaborative? When policymakers consult stakeholders, the potential for collaborative governance reaches only as far as the stakeholders are empowered – that is, only as far as the stakeholder participants in the consultative process have the power to make decisions or, at least, the power to meaningfully influence decisions. This potential is far from realized in many policymaking processes that include consultative procedures. Indeed, consultations that go beyond merely justifying elites’ decisions are not the norm, and empowered consultation is seldom if ever implemented in policy processes. As demands from across the political spectrum for responsive governance increase, policymakers run the risk of increasing alienation and cynicism when they fail to take the results of consultations seriously. To respond to this pressing challenge, we identify categories of consultation – their features and their ends – ranging from the disempowered to the empowered. We highlight the characteristics of empowered consultation in order for collaboration to be achieved, and we show the pitfalls that policymakers must navigate to avoid disempowering participants during and after consultations. Ultimately, we make a normative argument for empowered consultation, while articulating the limitations of this mechanism.

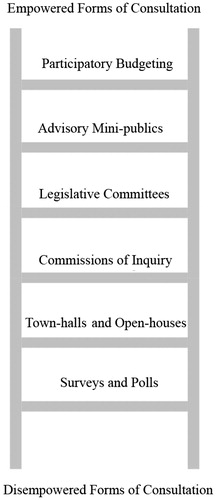

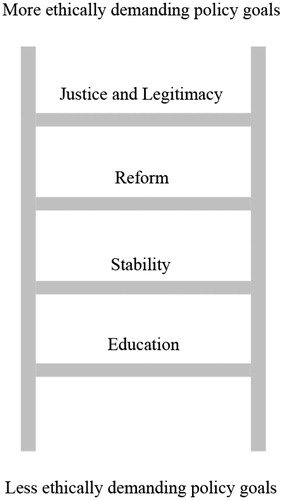

We invoke Sherry Arnstein’s classic ladder metaphor to exemplify the importance of empowerment in consultation (Arnstein Citation1969). As opposed to one, we develop two ladders. One is a Ladder of Forms, which is developed on the basis of a qualitative survey of consultation processes in diverse areas of public policy. This ladder represents an empirical claim, ranking particular kinds of consultation from the disempowered to empowered (e.g. from online surveys, through to participatory budgeting). Second, the Ladder of Ends ranks the goals of consultation relative to their normative significance (e.g. from policy education to policy justice and legitimacy). These ladders correspond to two basic claims of this paper: (1) consultation is collaborative only insofar as it takes an empowered form; and (2) the greater normative significance of the ends of consultation, the greater the importance of collaboration. In other words, if the end goal of consultation is the development of just and legitimate policy, then it is of greater importance that the consultation is collaborative and thus empowered.

2. Collaboration and consultation

Consultation can be defined as a form of political participation that is initiated from the top-down, typically by either a government or corporation. Non-elite actors as individuals, as an aggregate, or as a group provide their opinions to state or corporate actors – in other words, to actors with decision-making authority – on a specific policy or issue. Contrast this with collaboration, which, through “high intensity” participant engagement, strives to create a common understanding and a shared set of goals (Keast, Brown, and Mandell Citation2007, 12, 19). This requires mutual interdependence and joint action but nonetheless enables participants to be autonomous and responsive to their particular communities (Thomson, Perry, and Miller Citation2007). These processes can lead to lasting collaborative governance structures.

As Kirk Emerson, Tina Nabatchi and Stephen Balogh write, collaborative governance refers broadly to “the processes and structures of public policy decision making and management that engage people constructively across … agencies, levels of government, and/or the public, private and civic spheres” (Emerson, Nabatchi, and Balogh Citation2012, 2). More narrowly, it refers to interactions of stakeholders in collective decision-making processes that are “formal, consensus-oriented and deliberative” (Ansell and Gash Citation2008, 544). Collaboration is also designed to strengthen the normative values of “democracy and social learning,” with other goals and strategies co-produced by participants themselves, who share “responsibilities and resources” to execute collectively-determined strategies (Davies and White Citation2012, 160). While governments, civil society, and private enterprises have often turned to collaborative processes “as a last resort,” such processes are now being taken up “as a more proactive policy instrument on a grander scale” (Ansell and Gash Citation2018, 17; see also Johnson Citation2015). Thus, collaborative governance is evolving into a type of “governing arrangement” that is made unique through formal processes that employ consensus and deliberation to reach decisions (Ansell and Gash Citation2008, 544).

Collaboration, according to pioneers in this field, Chris Ansell and Alison Gash, should “transform adversarial relationships into more cooperative ones” (Ansell and Gash Citation2008, 545–547). Moreover, the state collaborates with stakeholders – whether as individuals or as groups – in a multilateral fashion, to enable stakeholders to create dialogue among themselves (Citation2008, 546). The process of collaboration is thus “highly iterative and non-linear” (Ansell and Gash Citation2008, 550), with participants responsible for policy outcomes, even if they lack the ultimate decision-making authority (2008). While Ansell and Gash tend to overstate their recent empirical claim regarding the prevalence of real collaboration in policy processes by not explicitly acknowledging the ways in which elite actors may create illusions of collaborative and deliberative governance (see for example Johnson Citation2009; Citation2011; Citation2015), their normative point remains in force: “collaborative governance is never merely consultative” because such mechanisms do not provide “two-way flows of communication or multilateral deliberation” (2008, 546).

Collaborative governance also demands more than the responsiveness valued by the New Public Management movement (Vigoda Citation2002). This responsiveness, which sees the citizen as client, values efficiency over accountability (Tindal et al. Citation2017; Vigoda Citation2002) and expects professional policy practitioners to wield their decision-making authority autonomously and vertically – reporting back up the chain of command (Christensen Citation2012; Fierlbeck, Gardner, and Levy Citation2018; Vigoda Citation2002). But as civil service managers have come to be viewed not as leaders of “service units producing public services” (Osborne Citation2006, 382), but also as “network managers and partnership leaders”, they have been asked to think and act “horizontally” as well (Christensen Citation2012, 1, 7). They are being asked to see citizens not merely as service recipients, but as sources of knowledge and legitimacy, and as “quite capable of engaging in deliberative problem solving” (Bryson, Crosby, and Bloomberg Citation2014, 447). This might be an idealized view of the citizen, but it moves us away from the idea of the disempowered client who might be consulted about the services she receives, toward an empowered stakeholder with whom policymakers can collaborate.

The gap between collaboration and consultation is a well-established theme. Arnstein’s classic definition shows consultation is neither collaborative nor necessarily empowering (Arnstein Citation1969). Consultation lands on a “middle rung” of Arnstein’s typology of participation – just above merely informing citizens, but below the kinds of partnerships that share decision-making power. Consultative acts by government are not designed to guide decisions. Instead, they exist primarily to demonstrate that “decision-making elites have gone through the required motions” (Arnstein Citation1969, 219). This kind of consultation offers flexibility to political actors and policy practitioners because it can be incorporated into policy processes without having substantive impacts. The consulted citizens have no guarantee that “their views will be heeded by the powerful” (Arnstein Citation1969, 217, italics in original). Indeed, government and corporate actors are not bound to act upon the views they hear in consultation processes (Arnstein Citation1969; Catt and Murphy Citation2003; Fung Citation2006; Roberts Citation2015). The process is often a one-way flow of information that does not foster ongoing participation through dialogue (Ansell and Gash Citation2008). It requires less work by those who have already considered the policy options, but allows political actors to claim they have sought public input.

There are other problems with consultation. The consulted rarely participate in the design of the consultation (Ansell and Gash Citation2008; Arnstein Citation1969; Halseth and Booth Citation2003), allowing the initiators to frame issues and direct the flow of decision-making. Moreover, neither elite actors nor consultation participants are provided an opportunity to clarify responses (Andriof et al. Citation2017; Ansell and Gash Citation2008; Arnstein Citation1969). Finally, the kind of interactions that might foster participation, for example, bringing competing stakeholders into direct contact with one another to reach a solution, are not encouraged (Andriof et al. Citation2017; Ansell and Gash Citation2008). In short, empowered consultations must avoid activities that constitute a mere “window dressing ritual” (Arnstein Citation1969, 219). But even more advanced efforts at consultation rarely meet the full criteria of collaboration. We develop these criteria in the following section.

3. Criteria of empowered consultation

While there is no hard and fast line that separates disempowered from empowered consultation, we argue that the more certain criteria are present in a form of consultation, the more likely it will be empowered. The more empowered, the more we can expect non-elite actors to participate in ways that influence the formulation and implementation of policy and the more we can say that the consultation between elites and non-elites is collaborative. Inclusion, interdependence, equal contributions to decisions, orientation toward an agreement, access to information, multilaterally exchanging reasons and considerations, and consequential input are all required (Johnson Citation2015).

The primary criteria are inclusive and equitable processes. This goes beyond merely inviting participation of all who are impacted by the policy under consideration. It includes ensuring participants are able to attend, which includes, for example, providing child-minding services, transportation and/or financial compensation for the expenses participation incurs. While participating, these actors need to understand the policy problem, options and implications of proposed solutions. This might mean producing materials in multiple languages and at appropriate reading levels, and providing independent experts to describe the situation and answer questions. It might also mean ensuring all participants can voice their thoughts – including those who, for cultural or personal reasons, shy away from addressing a large audience. Thus, an opportunity to share views and exchange reasons for those views is foundational to empowered consultation.

Participants in empowered processes are interdependent and seeking joint action. If they achieve joint action, the outcome is likely to be mutually beneficial, and these processes are consensus or agreement oriented. Instead of mimicking legislative systems with debates and votes, participants share their perspectives, conclusions, opinions, and reasoning to find common ground, reveal shared priorities and goals, and reach new understanding. Communication is not unidirectional in empowering consultations. Instead, participants present their views, respond to inquiries about those views, clarify, and even alter their positions. All participants must be able to interact with one another directly and contemporaneously, rather than through appointed intermediaries, the news media or a government committee.

Finally, the process of empowered consultation must be consequential by inducing responsive political decisions. For this criterion to be met, the process should in some way be binding on the authority that initiated it, and on the participants. Ideally, it also allows participants to play a role in implementation, ensuring the intentions of the participants are manifested, unintended consequences can be addressed, and eventually, the policy can be evaluated. This leads to another important element of consequential consultations: they allow for improvisational agenda setting. That is, the participants can, in some way, raise questions and concerns that the initiators of the process had not anticipated being part of the process.

In the following sections, we employ these criteria to categorize several processes of consultation. We develop our ladders – one of the forms, ranking consultation methods in terms of empowerment, and the other of ends, ranking the particular goals of consultation in terms of their normative significance.

4. Ladder of forms

In invoking Arnstein’s ladder metaphor, we highlight a range of consultation mechanisms that are ordered on the Ladder of Forms in terms of their features of empowerment. shows the bottom rung of the ladder occupied by surveys and polls, cited by both Arnstein (Citation1969) and Ansell and Gash (Citation2008). Participants are not interdependent, nor seeking joint action. Driven by elites from the top-down, surveys and polls gather public opinion – rather than foster consensus or agreement – for purposes established by policy or corporate elites. And they are not necessarily consequential; elites may or may not act on their results. They are therefore not empowered.

An example of a disempowered on-line survey comes from the Canadian Department of Justice officials’ consultation and subsequent analysis regarding prostitution laws in the Criminal Code (2014). All of the six questions were framed by the Department of Justice, and of them, three called for binary “yes/no” responses. One of the questions simply asked if the respondent was affiliated with an organization. While there were three opportunities to provide open-ended responses, there appears to have been little analysis – or at least little publicly available analysis – of these responses. The questions were asked only in a single round, resulting in a seven-page public report that relies solely on a “keyword search” for analysis of one question (Department of Justice Citation2014). There is little in the report to suggest that the remaining open-ended questions were analyzed. Such disempowering practices can lead to frustration by participants and provoke the very questions of legitimacy consultations seek to address.

The proliferation and sophistication of online surveys demonstrate how surveys can be more inclusive. For example, The City of Vancouver uses online surveys to ask participants to weigh in on issues ranging from infrastructure planning, livability, transportation systems, housing, and the presence of advertising in the city’s visual landscape (City of Vancouver n.Citationd.). For large and controversial projects, the City involves respondents in multiple rounds of online consultation, which suggests a kind of mutual interdependence and commitment to joint action. For example, when the City began planning the relocation of St. Paul’s Hospital – the only hospital in its downtown core – it went through two phases of consultation. It first launched an online survey and in-person open house to “identify aspirations and concerns” (City of Vancouver Citation2016a, 1). Later in the year, the City returned to the public, again through online and in-person methods, with two concepts to determine which one more closely adhered to the principles developed in the first phase (City of Vancouver Citation2016b).

While this project saw the integration of the guiding principles into the final policy statement developed by the City (City of Vancouver Citation2017), the larger, more controversial aspect of the project was ignored. The Ministry of Health, along with St. Paul’s Hospital management, through Providence Health Care, determined the hospital should be moved (Daily Hive Citation2015). Although one elected representative expressed concern over the move itself, public consultations were not designed to question whether the move was necessary or in the best interests of the city and/or province; indeed, prior to a provincial election, residents had been assured the hospital would not be moved (CBC News Citation2016). Policymakers often make important and controversial decisions prior to consultative processes, undermining legitimacy in the process. Empowering processes must also begin at the appropriate point in decision-making.

Town-hall or open-house meetings are an improvement over online forms in part because they offer two-way communication. Initiators typically seek input from the general public on complex and controversial policy options, and often do so on multiple occasions, in multiple locations. For example, in 2002, the Canadian Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO) launched a consultation process to obtain input that would be technically effective in managing nuclear waste and would align with the social and environmental priorities of Canadians. The expressed aim of this process was to develop collaboratively with Canadians a “socially acceptable, technically sound, environmentally responsible, and economically feasible” option (NWMO Citation2005, 17). The process was designed, funded, and overseen by the NWMO. It included more than 150 information open-houses and other participatory events, and was iterative, going through four phases. During each phase, NWMO focused these events on a key decision related to the long-term waste management and disposal of Canada’s nuclear waste. At the end of each phase, the NWMO publicly released a discussion document encapsulating the overall results of the dialogues. The document was then the focus of the next phase of dialogues, which sought validation of the previous decision and direction on the subsequent decision. In 2005, at the end of the fourth phase of the study, the NWMO released its final report and recommendations.

The NWMO’s recommendation for “adaptive phased management” was accepted in 2007 by the federal government. Generally, the consultation process yielded support for the recommendation (NWMO Citation2005). However, it suffered from many barriers to empowered participation, including insufficient funding and time for groups to develop their positions, important documents translated into only English and French, and relevant views being excluded from the ultimate recommendation (Johnson Citation2015). Indigenous nations and organizations, in particular, claimed their views were not given sufficient or even equal weight (Johnson Citation2015), which led to claims of further disempowerment. In other words, the consequential nature of this consultation process was limited.

National commissions of inquiry in parliamentary democracies are one rung higher on the Ladder of Forms in part due to their capacities for inclusiveness and two-way communication. While each commission has its own mandate, given to it by the government of the day, they all hear testimony and issue findings (Privy Council Office n.d.). Although somewhat rare – on average only three per decade in Canada – these multi-year processes can be empowering in terms of inclusion. The recent Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) attempted to uncover the truth and tell the stories about Canada’s residential school system.

The TRC was distinct in its inclusiveness. It not only accepted spoken testimony in the formal commission setting, but also accepted audio, video, photographs, documents, and written testimony. Such testimony could be submitted via an online form, rather than as sworn testimony (see Truth and Reconciliation Commission Citationn.d.). In addition to testifying in front of a large audience and members of the press, the TRC invited participants to testify in a private session (Niezen Citation2017). This is the kind of inclusiveness that is sensitive to the subject matter being discussed, and is an important criterion in circumstances of historical and on-going oppression and exploitation. Participants also acted as co-creators of the process. Local Aboriginal ceremonies were incorporated into proceedings, and Elders and traditional healers were present throughout proceedings to aid in the healing process (Truth and Reconciliation Commission Citation2015). We might consider this a form of cultural inclusivity.

These commissions can provide an opportunity for stakeholders to raise new issues. At the TRC for example, witnesses not only testified to their treatment at residential schools, but also put “unresolved claims on the table,” bringing to light their mistreatment and attempted assimilation through “Indian day schools, orphanages, schools for the deaf, convents, TB wards and prisons” (Niezen Citation2017, 149). And indeed, commissions, once established, can interpret their mandate as they see fit. The TRC did so in offering its eventual 94 Calls to Action that ranged from child care, poverty reduction, jurisdictional and juridical issues, to cultural issues (see Truth and Reconciliation Commission Citation2015).

Although creating an opportunity for innovation and inclusion, however contingent, commissions lack real multilateral deliberation and the capacity to directly initiate joint action. Moreover, such commissions’ findings are not binding on governments, and they have been seen as a means of putting off government action on controversial issues.

Legislative committees at federal and lower-level governments are a step up the ladder from commissions of inquiry. While the impact and experience of participants vary greatly at both commissions and committees, the potential for a consultation to be consequential is much stronger at a committee, where citizens come face to face with lawmakers. When a bill has moved to committee, it ideally receives scrutiny, very often provided by civil society actors, who voice concerns or support for pending legislation. While they hold the potential to be more inclusive than commissions of inquiry because Parliamentary committees are likely to be composed of a range of political perspectives, there are no guarantees. Legislators choose whom to bring before their committee and what questions to ask, for example. While David Docherty (Citation2005) reminds us that legislative committees can be less partisan and more collegial than whole legislatures, they are hardly oases from the ideological disagreements characteristic of democratic institutions. Indeed, a witness’s position on a bill might impact the kind of questions that witness is asked, and consequently impact that participant’s experience. While this might seem obvious to even casual observers of politics, it was only recently measured (see Johnson, Burns, and Porth Citation2017).

When Canadian Parliamentarians took up Bill C-36, new prostitution legislation, witnesses’ position on the bill affected the treatment they received and their likelihood of being invited. More supportive witnesses were called compared to those that opposed it (Johnson, Burns, and Porth Citation2017), suggesting a lack of equity in terms of time and diversity of views. Witnesses who opposed the bill were more likely to have a disempowering experience. They were more likely to experience questions that were disrespectful, receiving questions that included “gratuitous or inflammatory language” and/or that dismissed, diminished, or trivialized their experiences (Johnson, Burns, and Porth Citation2017, 931). Some questioners were combative toward opponents; instead of attempting to deepen understanding or reach consensus, these committee members seemed to be driven by a desire to “highlight disagreement,” “bring out contradictions,” confuse a witness or “to shut [a witness] down” (Johnson, Burns, and Porth Citation2017, 933). Finally, some questions posed to opponents of the bill by the government’s representatives were negative in tone, with questioners sounding “irritated, dismissive, or discouraging” (Johnson, Burns, and Porth Citation2017, 933).

Advisory mini-publics are a step up the ladder due to a number of empowering factors. They offer multilateral discussions, and allow for greater elaboration of reasons outside of a brief formal setting like a committee. They are more inclusive because they don't require the kind of preparation required of testifying in front of a committee, and might be more equitable because they are less intimidating and less reminiscent of colonial power structures. Among the best-known mini-publics are Deliberative Polls, which were developed in the late-1980s. Deliberative Polls bring together a random sample of citizens over one or two days, to engage with experts, deliberate among themselves, develop their understanding, and express their views. Participants receive balanced background information, listen to a diversity of expert opinions, raise questions and make comments in plenary sessions, and deliberate in small, moderated groups. To support inclusion and encourage multilateral participation, moderators act as neutral non-experts who encourage equitable participation (Fishkin and Farrar Citation2005, 75). They do not restrict what participants say or how they say it and do not attempt to develop a consensus (Fishkin and Farrar Citation2005). In plenary sessions, participants can ask questions of expert panels, and in small groups of ideally no more than eighteen participants, a resource person is available to answer questions of fact. The process is designed so that participants can reflect on what they have learned, and exchange reasons and arguments.

Similar to Deliberative Polls, Citizens’ Initiative Reviews (CIRs) are assembled to collectively deliberate on the strengths and weaknesses of a US state ballot initiative. CIRs were established in Oregon to review statewide ballot measures (House Bill 2895) in 2009. These CIRs consist of a random sample of 18 to 24 registered Oregonian voters. The process, developed on a model of a citizen jury (Crosby and Nethercut Citation2005), is structured as a formal “pro- and con-” debate. Two teams of petitioners and advocates compete to win the support of panelists, who then articulate their perspectives on the initiative in the Citizens’ Statement. But while teams compete, the structure facilitates collaboration among panelists, creating opportunities for the productive expression of reasons for or against the initiative. Panelists deliberate in plenary sessions that include presentations by petitioners, advocates, and experts followed by question-and-answer periods. They also participate in small “break out” groups, which enable them to discuss issues in greater depth. Additional plenary sessions follow so that all panelists are able to express and exchange reasons. While such elaborate processes might not be possible in all policymaking contexts, CIRs offer duplicable elements. Among the most significant of these is offering access to multiple perspectives, not merely multiple options developed by the government agency.

Another variation on the mini-publics is citizen juries and committees that are designed to develop policy. In England’s National Health System, such bodies have been convened since early in the Tony Blair era to guide decision making (Rowe and Shepherd Citation2002). John Parkinson (Citation2004) describes one early incarnation in 2000, where the process was driven by the desire to resolve a contentious dispute. Local officials at the Leicestershire Health Authority had determined that services should be discontinued at one Leicester facility, and centralized at another. This led to a public backlash led by local patient groups who gathered a 150,000-person petition calling for a reversal of the decision. Only then was a citizen jury initiated. While the citizen jury chose a path that was consistent with what the protestors wanted, Parkinson wonders what would have happened had their decision gone the other way. Indeed, some in the Health Authority agree that politicians would have “forced” local decision makers to reverse their decision, given the local and national political dynamics at play (Parkinson Citation2004, 384). A lack of consequentiality in consultative processes raises not only the possibility of disempowering participants, but undermining public faith in such processes, should they not be heeded by decision makers. Further, the citizen jury was enacted so late in the process, it can hardly be described as a consultation. Instead, it was forced to make a binary decision – relocate or not relocate a set of services – rather than having citizen engagement in developing priorities.

Even in 2017, NHS consultations suffer from a public perception of “secrecy” in policymaking and a “focus on securing support for a predetermined vision” (Martin, Carter, and Dent Citation2018, 29). Such views seem justified in light of views held by health system policymakers, managers and clinicians at the local level. One study of these actors’ views of participation in decision-making found that while those inside the system ideally want public engagement, they have a number of reservations about the role it should play. Concerns about oversimplification of complex problems; the diminishing and de-prioritization of services that might be unpopular, like addiction treatment; and dominance of well-organized groups led insiders to hesitate to use consultative methods (Daniels et al. Citation2018). Some professionals faced stumbling blocks, such as difficulty recruiting participants, and they aired concerns about a lack of representativeness. Others saw consultations as a necessary evil to avoid policy reversal after a decision has been made (Martin, Carter, and Dent Citation2018). It seems many in the NHS believe that members of the public should have minimal input. Instead, they should play an advisory role, where they “support and inform” rather than raise issues or decide (Daniels et al. Citation2018, 131).

While the professionals might, in fact, be correct that citizens cannot fully grasp the complexity of the situation, it is a problem when elites continue to refuse to offer any agenda-setting role to stakeholders. Ironically, some policy practitioners avoid early consultation out of fear that it will provoke an “adversarial” response (Daniels et al. Citation2018), when it is the very lack of early, empowered consultation that often leads to public outcry and criticism.

At all of the above points on the ladder, consultation is disempowered to the extent that participants’ influence in decision making and policy formulation is limited. Moving up the ladder, participatory budgeting provides a more empowering process. Participatory budgeting originated in Brazil in the late 1980s, emerging out of efforts to re-democratize political practices (Novy and Leubolt Citation2005). In 1988, the Workers’ Party came to power in Porto Alegre and initiated participatory budgeting to empower citizens regarding decisions that most directly affected them, such as funding for schools, roads, water, sewers, health care, and social welfare (Smith Citation2009).

In Porto Alegre, citizens not only develop a policy position, but also implement and evaluate their decisions. Although the municipal council retains the legal authority to reject budget proposals, in practice, it has never changed the outputs of participatory budgeting (Novy and Leubolt Citation2005). While 10% of the budget is technically allocated to popular assemblies (Pateman Citation2012), the Participatory Budget Council reviews the entire budget and comments on it before the Municipal Council finalizes it (Cabannes 2004). Brazil’s participatory budgeting is founded on several normative principles similar to those of deliberative and collaborative governance. It strives for inclusion and equality for all who wish to participate in collective decision making and upholds the principle that all affected by collectively binding decisions have a right to participate in those decisions. It recalls the ancient principle that citizens should meet in regular public forums, honoring rules such as procedural equality, access to information, and reasoned discourse towards a shared interest or common good (Johnson Citation2015).

In Canada, the Toronto Community Housing Corporation (TCHC) was inspired by participatory budgeting and decided to implement it in the early 2000s to address alienation and disenchantment among residents (Johnson Citation2015). Participatory budgeting within social housing communities in Toronto was one of the first experiments of its kind in Canada and the United States (Johnson Citation2009; Citation2011; Citation2015). Despite a strong commitment to the principles of participation, the TCHC’s system for resident participation developed a tension between procedural success and substantive shortcomings. The system granted participants regular opportunities to participate in the political life of their communities, and their outputs fed directly into decisions authorized and implemented by the TCHC. However, there were troubling limitations that hint at the lack of scope and authority participants might have expected to enjoy. Decision making within the TCHC continued to have a distinctively “top-down” tenor, with senior management in the corporate head office, and residents dispersed among local communities across the city. Instead of residents addressing larger structural challenges or engaging in critical evaluations of the TCHC, their deliberations were confined to the distribution of limited funds for highly localized projects (Johnson Citation2015). Rather than a process of empowering consultation, resident participation within the TCHC appears to have been a tool for management to justify funding some basic maintenance and security projects over others (Johnson Citation2015). Although empowered in policy development and implementation, and for this reason occupying the highest rung on our Ladder of Forms, participatory budgeting remains at a distance from an ideal of collaboration, and subject to manipulation by policymakers.

5. Ladder of ends

The preceding empirical categorization of consultation procedures ties into a normative argument that the more ethically demanding the goal or ends of the consultation, the more empowered the consultation ought to be. We thus propose a Ladder of Ends.

shows the lowest rung of this ladder is Policy Education – Arnstein’s (Citation1969) “non-participation” (217), which is driven by the goal of persuading. Here, the initiators of the consultation attempt to increase public support for a project rather than gather information about needs, interests, and wants. At best, the goal is the imposition of policy from elites who feel they are better equipped to determine a population’s needs. At worst, the end is manipulation of participants and the larger public. Government actors and the processes they employ in Policy Education take place in the domain of public relations, rather than in any arena of discovery, development, or debate. These public relations exercises very often take place after an unpopular policy has been decided upon. For example, in the US, federal Republican Congress members held town halls to respond to angry constituents after passing a law that weakened provisions of the Affordable Care Act (see for example Fortin and Victor Citation2017). While angry community members might voice their outrage and vent some steam, the role of the government actor is more one of advocacy as opposed to learning. It is unlikely that such attempts to appease the public succeed; it is instead likely to inflame tensions. But more importantly, such performances hold the potential to increase cynicism and reinforce populist arguments that elites are driving policymaking with very little concern for the impact of their agenda on the public. They not only undermine the goal of the politician but can erode faith in democratic institutions.

Next up the ladder is Policy Stability. Here, there is perhaps a greater desire for dialogue, but similar to Policy Education, the goal is to maintain a larger policy decision that has already been reached. By involving community members and stakeholders – through surveys and town hall meetings, for example – the goal is not to change policy outcomes, but to demonstrate outputs such as distributing numerous brochures, achieving high levels of attendance at meetings, and hitting the target number of survey respondents. We see this end most clearly illustrated above in the Canadian government’s approach to prostitution law. It is hard to see how a brief survey that was minimally analyzed was designed with any intention other than political theatre.

Policy Improvement is higher up the ladder. In this epistemic domain, empowered consultation might be a genuine goal of those conducting the consultation as they attempt to assess the needs and interests of a community. There might be an effort to ensure well-informed, equitable participation for all stakeholders. Such endeavors are also characterized by other activities we see at the higher end of the Ladder of Forms: multilateral discussions, and a preference for consensus and collaboration over combativeness. While this goal still runs the risk of stakeholders’ views being interpreted through more powerful actors’ lenses, there is the potential for governments to be held accountable. As we see in the example of the TRC, the Commission made efforts to ensure it could gather as much information as possible, and then attempted to convert that information into a significant program of change via its Calls to Action. Both the process and the outcome were potentially empowering, in that knowledge was directly produced from participants’ efforts, and those participants now have policy outcomes to work toward.

At the highest rung of the Ladder of Ends, we have the goal of Policy Justice and Legitimacy. This is the ethical domain where the process is designed to achieve a larger social goal – the empowerment of non-elite actors. Thus, the policy outcome, while important, is a secondary priority to a redistribution of power. We see this in participatory budgeting in Brazil. The goal is not merely to allow citizens to determine their budget priorities. It is to create a system whereby elected officials and bureaucrats are responsive to the will and needs of a larger, formerly disempowered group of stakeholders.

Many policymakers might not be consciously setting an end. But as consultative and deliberative governance practices become more widespread across levels of government and departments, practitioners who are able to match the ends to the means are more likely to achieve their goals. When policy practitioners are designing consultative efforts, they can use the tools of empowerment – and avoid the pitfalls – outlined above by first recognizing the dangers in lower-rung ends. As audiences grow more sophisticated about consultation, lower-rung ends typified by single-stage, tightly controlled events become riskier. Instead of provoking further frustration on the part of stakeholders, policymakers can strive to empower participants through creating opportunities for ongoing dialogue and committing to act on the information received through consultations. In doing so, elites can demonstrate a genuine desire to not only listen but alter their trajectory based on what they have learned.

Conclusion

We have not presented an exhaustive list of forms of consultation. Instead, we have shown examples that illuminate the characteristics and pitfalls of consultation, revealing an imperfect, contingent set of processes. We expect and welcome further investigation into a seemingly increasing number of forms of dialogue between powerful institutions and the people they affect.

When governments and corporations initiate public consultation, both they and their audiences should ask whether the consultation processes – its forms – are empowering. If elites truly desire a consultative process that will guide policy decisions, they must choose forms of consultation that will indeed be empowering. Thus, a more ambitious goal demands a greater role for stakeholders from the creation and adaptation of the consultation process, all the way through to implementation and evaluation of their policies. It is our hope that, by clarifying and defining empowering consultation that leads to collaborative governance, we have provided senior leaders in government and industry with a clearer pathway to empowered consultation that strives for meaningful consultation. We also hope to have provided analysts and activists with a toolkit by which to assess consultations. That is, to not only ask the right questions about the ends elites hope to achieve, but also to probe procedural features to determine if they are likely to lead to the kind of empowered consultation elites often claim to be seeking.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Andriof, J., S. Waddock, B. Husted, and S. S. Rahman. 2017. Unfolding Stakeholder Thinking 2: Relationships, Communication, Reporting and Performance. London: Routledge.

- Ansell, C., and A. Gash. 2008. “Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (4): 543–571. doi:10.1093/jopart/mum032.

- Ansell, C., and A. Gash. 2018. “Collaborative Platforms as a Governance Strategy.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 28 (1): 16–32. doi:10.1093/jopart/mux030.

- Arnstein, S. R. 1969. “A Ladder Of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35 (4): 216–224. doi:10.1080/01944366908977225.

- Bryson, J. M., B. C. Crosby, and L. Bloomberg. 2014. “Public Value Governance: Moving beyond Traditional Public Administration and the New Public Management.” Public Administration Review 74 (4): 445–456. doi:10.1111/puar.12238.

- Cabannes, Y. 2004. “72 Frequently Asked Questions about Participatory Budgeting. Urban Governance Toolkit Series. Nairobi, Kenya: UN-HABITAT.

- Catt, H., and M. Murphy. 2003. “What Voice for the People? Categorising Methods of Public Consultation.” Australian Journal of Political Science 38 (3): 407–421. doi:10.1080/1036114032000133967.

- CBC News. 2016. “St. Paul’s Hospital Operator Defends Relocation Ahead of Public Forums.” Accessed October 16, 2018. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/st-pauls-hospital-move-forums-1.3449642.

- Christensen, T. 2012. “Post-NPM and Changing Public Governance.” Meiji Journal of Political Science and Economics 1 (1): 1–11.

- City of Vancouver. 2016a. “New St. Paul’s Hospital and Health Campus: Phase 1: Guiding Principles.” Consultation Summary. Vancouver.

- City of Vancouver. 2016b. “New St. Paul’s Hospital and Health Campus: Phase 2: Development Concept Options.” Consultation Summary. Vancouver.

- City of Vancouver. 2017. “New St. Paul’s Hospital and Health Campus Policy Statement.”

- City of Vancouver n.d. “Talk Vancouver.” Accessed April 27, 2018. https://www.talkvancouver.com/S.aspx?s=126&r=Lf9hD3xc34QP0yw3qX8u0B&so=true&a=313&as=O_5n6d_D_T&fromdetect=1.

- Crosby, N., and D. Nethercut. 2005. “Citizens Juries: Creating a Trustworthy Voice of the People.” In The Deliberative Democracy Handbook: Strategies for Effective Civic Engagement in the Twenty-First Century, edited by John Gastil and Peter Levine, 111–119. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Cuthill, M. 2001. “Developing Local Government Policy and Processes for Community Consultation and Participation.” Urban Policy and Research 19 (2): 183–202. doi:10.1080/08111140108727871.

- Daily Hive. 2015. “St. Paul’s Hospital Closure Confirmed, New $1.2 Billion False Creek Flats Hospital to Be Built.” Daily Hive. Accessed October 16, 2018. http://dailyhive.com/vancouver/st-pauls-hospital-closure-confirmed-new-1-2-billion-false-creek-flats-hospital-built/.

- Daniels, T., I. Williams, S. Bryan, C. Mitton, and S. Robinson. 2018. “Involving Citizens in Disinvestment Decisions: What Do Health Professionals Think? Findings from a Multi-Method Study in the English NHS.” Health Economics, Policy and Law 13 (02): 162–188. doi:10.1017/S1744133117000330.

- Davies, A. L., and R. M. White. 2012. “Collaboration in Natural Resource Governance: Reconciling Stakeholder Expectations in Deer Management in Scotland.” Journal of Environmental Management 112: 160–169. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.07.032.

- Department of Justice. 2014. “Online Public Consultation on Prostitution-Related Offences in Canada: Final Results.” Accessed April 27, 2018. http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2014/jus/J2-394-2014-eng.pdf.

- Docherty, D. C. 2005. Legislatures. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

- Emerson, K., T. Nabatchi, and S. Balogh. 2012. “An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 22 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1093/jopart/mur011

- Fierlbeck, K., W. Gardner, and A. Levy. 2018. “New Public Governance in Health Care: Health Technology Assessment for Canadian Pharmaceuticals.” Canadian Public Administration 61 (1): 45–64. doi:10.1111/capa.12253.

- Fishkin, J., and C. Farrar. 2005. “Deliberative Polling: From Experiment to Community Resource.” In The Deliberative Democracy Handbook: Strategies for Effective Civic Engagement in the Twenty-First Century, edited by John Gastil and Peter Levine, 68–79. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Fortin, J., and D. Victor. 2017. “Critics at Town Halls Confront Republicans over Health Care.” The New York Times, December 22, 2017, sec. U.S. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/09/us/politics/town-hall-meetings-.html.

- Fung, A. 2006. “Varieties of Participation in Complex Governance.” Public Administration Review 66 (s1): 66–75. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.lib.sfu.ca/stable/4096571.

- Halseth, G., and A. Booth. 2003. “‘What Works Well; What Needs Improvement’: Lessons in Public Consultation from British Columbia’s Resource Planning Processes.” Local Environment 8 (4): 437–455. doi:10.1080/13549830306669.

- Johnson, G. F. 2009. “Deliberative Democratic Practices in Canada: An Analysis of Institutional Empowerment in Three Cases.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 42 (03): 679–703. doi:10.1017/S0008423909990072.

- Johnson, G. F. 2011. “The Limits of Deliberative Democracy and Empowerment: Elite Motivation in Three Canadian Cases.” Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de science politique 44 (1): 137–159. doi:10.1017/S0008423910001058.

- Johnson, G. F. 2015. Democratic Illusion: Deliberative Democracy In Canadian Public Policy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Johnson, G. F., M. Burns, and K. Porth. 2017. “A Question of Respect: A Qualitative Text Analysis of the Canadian Parliamentary Committee Hearings on the Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 50 (04): 921–953. doi:10.1017/S0008423917000294

- Keast, R., K. Brown, and M. Mandell. 2007. “Getting the Right Mix: Upacking Integration Meanings and Strategies.” International Public Management Journal 10 (1): 9–33. doi:10.1080/10967490601185716

- Martin, G. P., P. Carter, and M. Dent. 2018. “Major Health Service Transformation and the Public Voice: Conflict, Challenge or Complicity?” Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 23 (1): 28–35. doi:10.1177/1355819617728530.

- Niezen, R. 2017. Truth And Indignation: Canada’s Truth And Reconciliation Commission On Indian Residential Schools. 2nd ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Novy, A., and B. Leubolt. 2005. “Participatory Budgeting in Porto Alegre: Social Innovation and the Dialectical Relationship of State and Civil Society.” Urban Studies 42 (11): 2023–2026. doi:10.1080/00420980500279828

- Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO). 2005. “Choosing a Way Forward: The Future Management of Canada's Used Nuclear Fuel: Final Study.”

- Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO). 2005. Dialogue On Choosing A Way Forward: The NWMO Draft Study Report. Toronto: NWMO.

- Oregon Legislative Assembly. 2009. House Bill 2895. 75th Assembly, Session.

- Osborne, S. P. 2006. “The New Public Governance?” Public Management Review 8 (3): 377–387. doi:10.1080/14719030600853022.

- Parkinson, J. 2004. “Hearing Voices: Negotiating Representation Claims in Public Deliberation.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 6 (3): 370–388. doi:10.1111/j.1467-856X.2004.00145.x.

- Pateman, C. 2012. “Participatory Democracy Revisited.” Perspectives on Politics 10 (01): 7–19. doi:10.1017/S1537592711004877.

- Privy Council Office, Privy Council. n.d. “Commissions of Inquiry.” Government of Canada. Accessed May 25, 2018. https://www.canada.ca/en/privy-council/services/commissions-inquiry.html.

- Roberts, N. C. 2015. The Age Of Direct Citizen Participation. New York: Routledge.

- Rowe, R., and M. Shepherd. 2002. “Public Participation in the New NHS: No Closer to Citizen Control?.” Social Policy & Administration 36 (3): 275–290. doi:10.1111/1467-9515.00251.

- Smith, G. 2009. Democratic Innovations: Designing Institutions For Citizen Participation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Thomson, A. M., J. L. Perry, and T. K. Miller. 2007. “Conceptualizing and Measuring Collaboration.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 19 (1): 23–56. doi:10.1093/jopart/mum036.

- Tindal, C. R., S. N. Tindal, K. Stewart, and J. S. Patrick. 2017. Local Government In Canada. Toronto: Nelson Education.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. “Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.”

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. n.d. “Share Your Truth.” Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Accessed May 25, 2018. http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/index.php?p=807.

- Vigoda, E. 2002. “From Responsiveness to Collaboration: Governance, Citizens, and the Next Generation of Public Administration.” Public Administration Review 62 (5): 527–540. doi:10.1111/1540-6210.00235.