Abstract

Once the muse of oracles and soothsayers, global systemic instability is now increasingly plausible given the convergence of wicked, synchronous, and interconnected problems like climate change and socioeconomic inequality. International organizations have confronted such crises with policy platforms like the Sustainable Development Goals, New Urban Agenda, and Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction. However, there is increasing need to connect the meta-context of systemic crises with the practical realities facing local policy practitioners, who must determine how to manage the local impacts of a so-called “perfect storm” of policy challenges. This article argues first that policy interventions addressing wicked problems are locked into a legacy epistemic focused on discrete problem identification and associated policy solutions, and second that such policy thinking will fail to adequately address global crises. The article critically visits Enlightenment rationality-inspired instrumentalism underlying the ongoing high-modernist and technocratic approach of policymaking, deriving a suite of recommendations based on a theoretical application of policy capacity.

1. Introduction and background

In 1755, the city of Lisbon, Portugal suffered a massive earthquake, triggering a catastrophic fire and flooding that led to wide-scale destruction of the city. The event was of such consequence as to receive mention by Voltaire in his classic Candide. The earthquake led to a turn toward formal conceptualizations of risk (de Almeida Citation2009) and other cognitive changes that some argued marked a historical contingency in the dawning of the Enlightenment (Jeffery Citation2008). In the modern era, the inadequacy of policy responses to address climate change exposes a paradigm resistant to change but may also mark a historical contingency of similar gravity. The Lisbon earthquake was a factor in an epistemic transition, with a new set of ideas replacing the old; collapsing structures, both literal and figurative, invited a new way of thinking and knowing. What does the modern policy practitioner do while awaiting this proverbial earthquake, the trigger for a new way of thinking, and the shift in epistemological paradigm? This article addresses that question.

In the twenty-first century, the global community will be confronted with a perfect storm of global crises: climate change, ecological degradation, food and water insecurity, emergent pandemics, and demographic shifts [Kuecker Citation2014 (2007)]. These crises have the characteristics of wicked problems; at minimum the perfect storm is precipitating an era of social, economic, and political disruption, and at worst it portends a catastrophic collapse of modern systems. With each day, the latter seems likelier. Labeling this phenomenon the “perfect storm” implies that human history has transitioned from an era of tame problems to one of wicked problems. Tame problems are soluble, whereas wicked problems have no solutions (Rittel and Webber Citation1973). The issue faced by policy practitioners (public servants involved in the policymaking process at any stage) is that Enlightenment rationality – the epistemic underlying the modernist problem-solving approach – treats every problem as tame. While that approach worked in an era lacking any concept of a “global crisis,” it is not well-suited for the current era; yet, old ways of understanding and addressing problems are surprisingly slow to pass. We argue that policy practitioners must understand that the current way of addressing the perfect storm is outdated and that a transition to a predicament thinking-based policy paradigm is needed. We define predicament thinking as the acknowledgment by policy practitioners that policy should not obsess over solutions to discrete problems but should instead acknowledge the need to live with and manage the impacts of problems that are wicked and unsolvable.

As global crises visiting themselves on localities with increasing frequency, meta-scale challenges are brought to the local doorstep of agencies and policy practitioners lacking the experience, expertise, training, or capacity to address them. Climate change is the global crisis on which this article focuses; however, the article’s lessons are applicable to other global crises and wicked problems. While global crises such as financial recessions, pandemics, forced migration, and security threats vary in scope and length according to economic, political, and other cycles, climate change is unique in its potential for long-term endurance. For this reason, we argue that climate change is an instructive context for exploring a long-term shift in the policy epistemic. The literature has helpfully considered the strategic policy implications of a world defined by wicked problems and global crises, with a particularly useful line of scholarship covering the limitations of instrumental rationality and the need for interpretive and discursive policymaking approaches (Davoudi Citation2012; Fischer Citation2007; Hendriks Citation2009; Howarth Citation2010). According to Head (Citation2018), “The wicked problems framework resonates more positively with constructivist approaches to policy studies because of the emphasis given to the diversity and primacy of stakeholder values and practitioner perspectives” (p. 13). From the era of Lindblom (Citation1959) and Simon (Citation1957) to more recent interest in constructivism (Hoppe Citation2002) and Foucault’s governmentality (Colebatch Citation2002), literature applied to understanding policymaking has acknowledged the limitations of executing pure rationality in the messy sphere of multi-level governance environments characterized by discrepancies in analytical and other capacities.

We build on this literature by connecting the meta-context of global crises with the context of policy capacity as defined along individual, organizational, and systemic dimensions (Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett Citation2015). Our argument maintains that the epistemic paradigm of problem-solving remains stubbornly present in procedural and heuristic conceptualizations of policy problems, but does not accord with the characteristics of wicked problems; the upshot is that efforts to upgrade and modernize policy tools – e.g. through technology – reflect legacy thinking ossified around principles of Enlightenment rationality and, thus, fail to realize their promised effectiveness. As such, there is theoretical space to integrate a new concept of policy problematization – what Turnbull (Citation2006) calls an “epistemology of questioning” – into theories of policy change that have already provided a rich theoretical lens for examining policymaking under the old epistemic. The practical implication of this argument is that seemingly transformative modifications in a given stage of the policy process [from problem definition to policy formulation, implementation, and evaluation; see Howlett and Geist (Citation2013) for a summary] improve only the efficiency of old models. To paraphrase a quote from the long-running animated television show The Simpsons, there’s the right way, the wrong way, and the Max Power way – which is the wrong way, but faster. Simpson’s declaration is epistemologically incrementalist; the old ways of thinking, being, and doing are not dismissed but tinkered with at the margins – modernized and reinvigorated, even if they are fundamentally ill-suited for the problems they seek to address. Modifications to existing paradigms can generate immediate and observable effects by economizing existing systems, iteratively addressing limiting constraints in the fashion of a Liebig’s Law1 adapted to public management. The danger lies in the fact that such effects can be used to excuse technocratic-minded policy regimes from the difficult work of systemic transformation.

Given these limitations in policy thinking, we argue that the foundations of the problem-solving epistemic must be at least reconsidered and ideally abandoned. In exploring how this can materialize, this article uses the concept of a “transition problem” to describe the current liminal state in which new ways of thinking based on wicked problems (e.g. predicament thinking) exist alongside old ways of thinking based on discrete problems (e.g. problem-solving). We seek to more deeply explore the difficulties of this transition while arguing that the new way of thinking that replaces the outdated policy epistemic is as yet unknowable – a reality that itself obstructs the advancement of the transition. The liminality of the transition period is characterized by neither the old nor the new; it is a third thing with its own policy context and mandates. In this light, policy practitioners have two options: to foster conditions for advancing the transition (to whatever degree such a transition results from top-down engineering rather than organic social or economic forces) or to keep using the old ideas and tools in a way that mitigates the damage of their continued use.

This article builds its argument on two claims that are later elaborated: (i) public policy has failed to properly address wicked problems due to anachronistic thinking (which we label “epistemic lock-in”); and (ii) the ability to address wicked problems is determined in significant part by building internal capacities oriented toward predicament thinking. The article provides strategies to change these conditions, addressing the question "which strategies can policy practitioners adopt to improve policy capacity to address wicked problems?" This article continues with a review of our foundational assumption: the lock-in of an epistemic bias toward Enlightenment rationality and the problem-solving ethos in policymaking. This includes an examination of how an alternative paradigm can be understood through elements of the capacity framework introduced by Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett (Citation2015). The section examines how the concept of predicament thinking for wicked problems can be interpreted through a policy capacity framework. The third section outlines policy recommendations, and the fourth describes how these recommendations can be applied toward fostering epistemic transition. The conclusion issues a call for an invigorated research agenda around epistemic transition.

2. Predicament thinking and policy capacity

Reliance on discrete measurement of tightly defined policy problems – a legacy of Enlightenment rationality – fails to account for the wicked nature of predicaments that are interconnected and lack clear paths to resolution. Confronting the predicaments of the twenty-first century using the problem-solving tools of twentieth century policymaking obstructs progress on policy visions. An example is climate change, for which the urgency of resolution is collectively agreed by the international community and articulated through a panoply of frameworks and protocols such as the Sustainable Development Goals, the New Urban Agenda, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, and the Paris Climate Agreement. While they offer some degree of policy guidance, it is unclear whether these frameworks and protocols – and indeed public policy as a discipline – are prepared to embrace epistemic transition away from a focus on discrete problem-solving and toward predicament thinking. Assuming the policy epistemic changes, it is also unclear whether the result will be a system of thought recognizable to modern scholarship and practice. We argue that a liminal period is emerging in which the epistemic transition balances old and new ways of thinking – arguably a third epistemic epoch unto itself with its own series of uncertainties and challenges. This is the perspective through which we derive fresh value from well-worn policy change frameworks.

Recent research in the field of policy sciences has turned toward policy tools and capacity. For example, Bali, Capano, and Ramesh (Citation2019) argue that previous “waves” of policy design (e.g. top-down before the 1970s and a focus on complexity and implementation challenges in the 1970s–1980s) have given way to an approach favoring policy tools and their mixes, whose anticipatory effectiveness in instrumentality and capacity can be understood through analytical, operational, and political levels. This section proceeds by taking up Head’s (Citation2008) call to research action in a context that has evolved substantially in the past decade: “The three most widely recommended approaches to wicked problems – better knowledge, better consultation, and better use of third-party partners – deserve closer attention in future research” (p. 114). Head (Citation2018) more recently calls on policy analysts to “focus carefully and reflexively on the nature of the policy problems, their evolution, the experience and knowledge of relevant stakeholders and the prospects of effective action in different situations” (p. 13). To both ends, this section outlines practical implications relevant to the design and management of policymaking systems, as structured through the concept of policy capacity – an analytical frame that can be used to, among other things, explain the process by which policymaking systems develop, democratize, and apply knowledge. The sub-field of policy capacity is fertile for examining wicked problems, as Head (Citation2018) argues: “the political debate about building the policy capacity of the public sector is part of the fabric of debates about better managing wicked problems” (p. 9).

The policy capacity framework introduced by Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett (Citation2015) has been referenced and developed in a number of studies, with foundational articles published in a special issue in the journal Policy and Society (Volume 34, 2015) and chapters in an edited volume (Wu, Howlett, and Ramesh Citation2018). Studies of particular relevance to this article include those addressing policy learning under uncertainty (Nair and Howlett Citation2017), environments of uncertainty where innovation in policymaking is needed (Karo and Kattel Citation2018), and measurements of policy capacity as treated by global-level governance indices (Hartley and Zhang Citation2018). A useful application of the capacity framework to address stakeholder dialogues for global-scale interventions is proposed by Cashore et al. (Citation2019), who argue that the anticipatory mandate for policymaking should be focused not only on the problem itself but on “multiple-step causal pathways through which influence of transnational and/or international actors and institutions might occur” (p. 1). Our approach builds on recognized connections between policy capacity and global-scale analysis by addressing capacity to confront wicked problems. The descriptors populating each cell of the matrix in are competencies aimed specifically at issues of relevance for predicament thinking and crisis management.

Table 1. Policy capacity for predicament policymaking (adapted from Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett Citation2015).

Efforts to build adaptive analytical competence across all levels of the capacity framework (individual, organizational, and systemic) have focused in the modern era on quantitative methods in service to technocratic rationality. We argue that epistemic transition requires capacities in qualitative methodology, understanding of cultural context and nuance, and open-mindedness about emerging techniques and idea frames. Thus, analytical proficiency is needed across both standard and non-standard methods [e.g. so-called “indigenous knowledges” or “other knowledges” – see Berg and Lidskog (Citation2018) for a related discussion with reference to global environmental governance]. Given the critical tone of our proposal, it is of further relevance to consider that the policy system and its broader societal context are imbued with a capitalist logic (as operationalized by New Public Management and robustly researched) and that the legitimacy of its dominant players rests on this logic. An example is the promotion of smart city projects as a “common-sense” solution to urban problems, as endorsed by local governments, international organizations, and the private sector (Kuecker and Hartley, Citation2019).

Other knowledges are destined to be expropriated and redefined unless the system of epistemological hegemony is dismantled. This process has particular implications for individual analytical capacity. Our argument about the need to deviate from the received epistemic calls for a radical pedagogy that challenges the legacies of colonial and neocolonial systems, including their vestiges in public policy education and practice. The practical implication of such a dismantling is that students of public policy must be exposed to the history of Enlightenment thought and its expression in high-modernist problem-solving and technocracy. Policy practitioners with a robust understanding of the intellectual legacies of policy theories are better equipped to recognize their own cognitive blind-spots and the general limitations of the field itself. Building competence is thus not a question solely of individual open-mindedness but of dismantling an epistemic system locked-in by path dependence. The implication of this argument is that the field of public policy needs an external shock to force a transition into a new paradigm; the perpetuation of outdated thinking – as embedded in legacy interests – will not achieve this. The individual’s managerial competences include not only standard administrative skills but also awareness of how alternative epistemological frames (e.g. other knowledges) can reshape organizational functionality and power dynamics. A strategic vision concerning crisis management is also essential and requires updated awareness about global trends and an understanding about how they relate to the individual’s duties and role, as a policy practitioner, within her organization and broader society. Much of the same is relevant, at higher scales, for individual political competencies; indeed, it is the presence or lack of such characteristics in global leaders (and potentially the power epistemic implied by the term “global leaders” itself) that may determine the fate of humanity in the twenty-first century.

Organizational-analytical capacity is built in part through appropriation of staff development resources, a concept that is fundamentally non-normative but can be targeted for the purpose of this study toward equipping staff with the individual analytical skills previously described. Organizations should also encourage a receptive environment for alternative forms of knowledge and analysis, not only in organizational culture but also in institutional structure. This includes internal requirements for analytical triangulation emphasizing both quantitative and qualitative methods, and an openness that allows those requirements to evolve as new methods of understanding global crises emerge. While concurrently pursuing the mandate to democratize public administration (Denhardt and Denhardt Citation2000), organizations must operate in a ring-fenced environment that is impervious to overt political capture. The process of inquiry that constitutes robust analysis must stand firm in the swirling crosswinds of political fervor. Examples are populist movements skeptical of science, such as the so-called “anti-vaxx” or “climate denial” phenomena that have moved from near obscurity to some level of political visibility since the mid-2010s. Caution against capture does not necessarily imply a greater threat from either the “right” or “left” wings of the political-ideological spectrum; instead, such caution addresses threats to the ability of an organization to conduct independent and valid analysis for use in policymaking. A balance must be ensured that protects the integrity of analysis (under whatever epistemology it is conducted) while maintaining a political fluidity that animates democratic systems; this article proposes no absolute level of balance, as the level must be re-calibrated across time and socio-political contexts.

Systemic-analytical capacity broadly enables analytical skills to develop at the two lower-scale levels (organizational and individual). This implies the need to create an environment conducive to the emergence of research communities, including legal protections for those engaged in the types of research that might threaten the commercial or legal viability of certain enterprises or industries. This may also include funding for research that might not otherwise be undertaken by the private sector. Ensuring systemic managerial capabilities is contingent on the promotion of inter-governmental, inter-organizational, and inter-sectoral collaboration; the benefit of this approach is not only collective capacity and gains from cooperative synergies, but also the cross-fertilization of epistemologies and potential awareness of marginalized methods. Such collaboration also builds redundancy and resilience into crisis preparedness systems, and can encourage progress toward harmonization of managerial practices across the broader policy ecosphere. Finally, systemic political variables are crucial for building and protecting policy capacity to address global crises and their local manifestations. Based on the assumption that robust preparedness involves open communication, along with a critical and introspective approach to analyzing policy options and implementing solutions, governments should ensure a political environment that promotes free exchange of ideas and democratic responsiveness in policymaking. Such efforts may seem antithetical to a political and economic system that seems to be steered within elite government and corporate circles; even the notion of technocracy implies a marginalization of democratic input. Nevertheless, working to fortify systemic democratic elements against authoritarian pressures can build independent and durable systemic capacity for building the adaptation and flexibility to address wicked problems.

3. Policy recommendations

3.1. Analytical capacities

Given the examinations of policy capacity in the previously mentioned special issue and edited volume, the question becomes which public policy behavior (process) or condition (capacity) generates evolution, adaptation, and flexibility (e.g. epistemic transition) in responding to wicked problems. There is scope also for looking beyond structural determinants of capacity to account for cultural factors like trust and conflict internal to organizations (Christensen, Laegreid, and Laegreid Citation2019) and analytical capacity for wicked problems like climate change (Hsu Citation2015). In combination, these factors can provide a more holistic picture of the ability of policy to respond to wicked problems. Having discussed various policy capacities, we provide in this section recommendations focusing mainly on analytical and political capacities. These capacity skill types are chosen first because in combination they relate best to our argument about the challenges of negotiated problem definitions and the limits of reductionist paradigms of knowledge development (i.e. understandings limited only to what is measured by “modern methods” and acknowledged by received technocratic wisdom). Second, we acknowledge that due research has been conducted on operational and implementation capacity related to systemic resilience for climate threats, namely through the execution of the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and more recently the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Allen, Metternicht, and Wiedmann Citation2018; Bhattacharya and Ali Citation2014; Elder, Bengtsson, and Akenji Citation2016; Sarvajayakesavalu Citation2015). For a discussion of the operational capacity element of the Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett (Citation2015) framework with reference to the transition from the MDGs to the SDGs, see Howlett and Saguin (Citation2018). Understanding how analytical competencies should not merely be deepened but reshaped to adjust to evolving epistemological paradigms is crucial to the advancement of policy preparedness regarding wicked problems. Political competencies are also relevant to the discussion of wicked problems, as issue-framing is often the result of discursive negotiations among those impacted by problem outcomes and is thus a politically mediated exercise.

Given the uncertainties and amorphous nature characterizing wicked problems, it is necessary to establish strong analytical capacities to determine what is knowable about problems. This article has already argued that practitioners with influence over policy design must be trained to identify and critically assess information, sources, and epistemological biases that attend analysis and research. This requires the development of internal training programs (e.g. seminars and workshops) for both newly hired and longer-serving practitioners. Equipping practitioners with crisis-specific skills and competencies can be achieved by requiring courses on crisis management and communications, providing opportunities for iterative up-skilling and retraining, and encouraging frequent rotations across functional agencies to ensure exposure to varying organizational cultures and their policy issues.

At the organizational level, the literature has been vocal concerning the role and usefulness of policy tools focusing on strategic foresight, horizon scanning, mixed scanning, futures planning, and other heuristic devices and critical capacities for managing complexity and uncertainty (Bali and Ramesh Citation2019; Capano and Woo Citation2017; Etzioni Citation1967, Citation1986; Higgott and Woo Citation2019). These capabilities can be embedded at the organizational level through the formation of strategic foresight units within public agencies and through the creation of a centralized agency focused on futures and foresight. Such units are prevalent in the United Kingdom, Singapore, Finland, and the Netherlands (Habegger Citation2010; Kaivo-Oja, Marttinen, and Varelius Citation2002; Kuosa Citation2011). Managerial functionality at the organizational level can further benefit from clear chains-of-command and lines of communications. This requires internal organizational discipline, often enforced by independent watchdog units that ensure strategic coherence, transparency, and public accountability.

Efforts to enhance systemic-analytical capacity should focus in one aspect on ensuring greater access to data and other forms of knowledge, usually through the establishment of open-access platforms (data is seen as instrumental in enabling the functionality of foresight tools); where possible, these systems should also be transparent about the sources of data and the purpose of data collection, and about the limitations of such data with regard to those purposes. Another recommendation is to dissolve information silos within government and institutionalize information sharing across governmental units and agencies. This may require the establishment of system-wide protocols and directives or incentives for individual agencies to oblige, along with further development of managerial skills. While analytical capacities can provide agencies and policy practitioners with access to information and data, managerial capacities are necessary for implementing responses to crises and systemic shocks. A “whole-of-government” approach has been proposed in the literature as a means of enabling closer coordination among functional units and agencies, allowing policy practitioners to respond to crises in a more swift and nimble manner (Christensen and Laegreid Citation2007; Morrison and Lane Citation2005).

The nature of wicked problems requires policy practitioners to remain wary of epistemologies and ways of thinking that have become entrenched across government systems, and to be critical and outspoken in challenging hegemonic narratives. Examples of these ways of thinking include bias toward technocratic solutions and the exclusive application of technology- or data-enabled interventions to address the impacts of wicked problems (e.g. urban flooding resulting from sea-level rise); even modest efficacy in achieving these solutions can generate the illusion that deeper systemic change is unnecessary. It is clear from the persistence of crises that reliance on such legacy systems has compromised current levels of systemic preparedness and resilience, and has arguably been complicit in exacerbating wicked problems themselves. Thus, managers must balance meeting the immediate needs of residents with gently nudging the system toward new epistemic paradigms. From a practical perspective, the latter is an incremental process that will progress only with shifting attitudes among managers and the general public (assuming a cataclysmic shock-event does not force an immediate change).

3.1.1. Policy recommendations suite #1 (analytical capacities)

Individual: training in multiple methodologies and sensitivity toward epistemological biases

Organizational: establishment of strategic foresight units at the agency and system-wide levels

Systemic: protocols for information sharing and collaborative efforts to define problems

3.2. Political capacities

Political capacities provide the foundation on which mutual state-society trust and social capital are built, both of which are crucial for managing wicked problems. At the individual level, efforts to establish political capacities can include rotation of line managers across units and even outside of government. For example, public sector leadership development courses in Singapore include operational departments as well as grassroots and social service organizations. Connections to grassroots and social service organizations are particularly important for crisis management, since these organizations frequently play a key role in collective action, ground-up initiatives, and front-line responses. At the epistemological level, such connections – if enabled through fair and equal discourse – can elevate and empower alternative problem-framing narratives. This includes the provision of platforms for idea-sharing such as dialogue sessions and “town hall” meetings (Lukensmeyer and Brigham Citation2002; Zuckerman-Parker and Shank Citation2008). These gatherings should occur in a way that does not simply mine participants for policy ideas in response to specific problems, but seeks to understand how participants obtain, construct, and use knowledge itself; such an approach could initiate a substantive dialogue and institutional self-reflection about the types of underlying epistemological assumptions that fail to be critically examined during crisis planning.

At the organizational level, public agencies need to ensure independence and transparency to avoid capture by power brokers, political factions, and elite interests. As with managerial capacities, this can be enforced through the establishment of independent watchdog units and other monitoring and accountability mechanisms. Furthermore, organizations need to be attuned to changes and events on the ground. This can be achieved through the use of technologies such as “mayors’ dashboards” and applications such as the “311” system in the United States [see Hartmann, Mainka, and Stock (Citation2017) for a discussion about the contribution of “311” to the quality of public service delivery in American cities]. These tools provide policy practitioners with real-time access to feedback on a variety of issues from waste management to emergency response. At the systemic level, public consultation and engagement efforts such as Singapore’s Our Singapore Conversation (Kuah and Lim Citation2014) can contribute to greater social trust and a collective approach to problem definition that incorporates residents’ views and opinions.

3.2.1. Policy recommendations suite #2 (political capacities)

Individual: political skills development through interdepartmental rotation

Individual and organizational: incorporation of non-government organizations in such rotations

Systemic: conduits of influence and exchange for non-mainstream and alternative epistemologies

4. Applying recommendations to foster transition

This section briefly extends the preceding discussion about capacity-based recommendations to efforts for fostering transition to a predicament-thinking policy paradigm. We have argued that it is necessary to create environments, cultures, contexts that promote capacity for building resilience. However, public policy struggles to embrace the concepts of liminality and emergence that are necessary for fostering such a transition; in its rationalist epistemological legacy, modern policymaking attempts to capture, dominate, control, and direct. The crucial disconnect lies in the fact that the concepts of management and emerging properties are incompatible. Johnson (Citation2001) argues that emergent properties are systems that lack pace-makers (a coordinating agent or leader) but are instead defined by “horizontal leadership,” distributed agency, and even anarchy. We argue that the modern policymaking paradigm is still characterized by the presence or assumed presence of pace-makers, even amidst the long popular theory and practice of collaborative governance and other bottom-up policy paradigms (anti-authoritarian but still rooted in the old epistemics of problem definition and largely bereft of Johnson’s emergence).

The closest the policy literature has come to theorizing emergence, as a property of collective action within a public commons, is Ostrom’s (Citation1990) Institutional and Analysis Development (IAD) framework. In explaining how a community relying not on a coordinating authority but on formal and informal institutions (as rules) can effectively self-govern in the use of common pool resources, Ostrom exhibits how emergent properties materialize in “open-source” (non-proprietary, non-corporate) environments, cultures, and contexts. Despite the emphasis of neoliberal policy and economic approaches on open markets (a particular form of open-source), such policies emphasize the agency and interests of the individual. By contrast, an open-source model for addressing wicked problems implies a collective action perspective; innovation and creativity occur in both contexts but more in the latter for collective problems [see Crosby, Hart, and Torfing (Citation2017) for a discussion about collaborative policy innovation for complex problems]. Emergence through horizontal leadership can lead to open-source solutions for problems in the public commons by creating space for innovation and creativity.

Three elements are essential for fostering a transition in public policy toward better preparation for addressing wicked problems through open-source models. The first is intellectual diversity, which can evolve naturally from an open-source commons and horizontal leadership structures and is crucial for emergent properties (as with a Darwinian model of evolution). For public policy to transition to a predicament thinking epistemic through intellectual cross-pollination, diversity in the characteristics of its practitioners is needed – across race, class, gender, age, and geography but also ideas, theories, and educational and disciplinary backgrounds. Second, rewards and incentives should be provided for “sideways thinking” and risk-taking. Such an approach unseats traditional power relations, an essential step in promoting open-source environments, horizontal leadership, and diversity; power relations should be equalized (horizontal) as far as possible for emergence to happen. The final element in the transition involves an honest reckoning about how the above partners with artificial intelligence technologies (AI). Johnson (Citation2001) discusses machine learning as an example of emergence. Public policy must consider AI as a partner in a horizontal sense, not as an agent (for now) but as a facilitator.

As these are high-level recommendations, it is appropriate to consider what policy practitioners should do in the interim period, provided they believe that their legacy epistemic has failed. We propose the following recommendations for how policy practitioners can operate in a liminal and transitioning policy environment.

Foster emergent properties in the policy practitioner environment

Create organizational structures that favor horizontal leadership over pace-makers; equalize power relations

Enable open-source approaches that serve the public commons

Incentivize innovation, creativity, sideways thinking, and risk-taking

Embrace all forms of diversity

Partner with AI and prepare for technological singularity (Bostrom, Dafoe, and Flynn Citation2018; Kurzweil Citation2005; Leitner and Stiefmueller Citation2019)

The practical need to maintain the consistency of current and prevailing policy models is understandable and prevents immediate and disruptive epistemological change as a designed intervention. However, policy practitioners can take some steps to build effectiveness in the current liminal environment and to prepare for the eventual transition. We propose first that the field of public policy, suffering a deficit of understanding about how to manage wicked problems, simply “stop digging” further into its epistemic hole. This involves coming to a collective understanding about criteria for identifying “no-go” policies – those current or under consideration that exacerbate wicked problems but can be discontinued with minimal systemic disruption. Second, we propose that policy practitioners consider the linkages between current policy models and economic and social models, embarking on a sincere reckoning about how these linkages perpetuate outdated thinking and confound transition. As long as public policies are in structural and functional thrall to unfettered varieties of capitalist reproduction, the aforementioned hole will deepen; the endogenous relationship between policy and economic models represents both their protection from exogenously imposed transition and their inability to embrace emergence, open-sourcing, and flexibility in pursuit of resilience. Third, internal policy systems should enable practitioners to recognize anomalous data and report it to those making policy. Kuhn’s (Citation1962) concept of paradigm shift maintains that anomalous data is what shifts paradigms – arguably in ways reminiscent of Baumgartner and Jones’ (Citation1993) punctuated equilibrium theory. The nature of paradigm shift in natural sciences is often more revolutionary than evolutionary; it is arguable that a similar expectation could be held when considering the broader structural context of epistemic transition. Finally, at the practical level protections are needed for whistleblowers and practitioners whose findings or ideas countervail narratives promoted by legacy interests within the policy system.

An important step in operationalizing applications of the predicament thinking model is identifying which levels and skills of policy capacity are most relevant to the organization and the policy issue at hand. provides guidance on this matter. An example is the SDGs [for a useful overview, see Sachs (Citation2012)]. Plans for the implementation of the SDGs (a process also referred to as “localization”) began in 2016 and cover the near totality of scope, policy subfields, and governance units. Additionally, the SDGs “place greater demands on the scientific community than did the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which they replace” (Lu et al. Citation2015, 432). This presents an instructive case of the interplay between knowledge and power at the local level. The importation of a predicament thinking perspective can mediate this interplay by recognizing a broader and more epistemologically diverse understanding of policy problems; this goes beyond the structural-fix (Heberlein et al. Citation1974) concepts of policy integration, consistency, and coordination (described by Stead and Meijers Citation2009) to encompass negotiated understandings of knowledge and policy problems themselves. The “codified recognition of epistemological contestation” in the organizational-analytical dimension of capacity () implies that understandings of knowledge may vary across local contexts and should be acknowledged in interpreting SDG imperatives. Focusing on the urban scale of SGD implementation, Barnett and Parnell (Citation2016) reference a growing critical urban studies literature maintaining that “geographical sources and reference points around which urban thought has traditionally been shaped need to be expanded and relocated” (p. 95). In bringing this issue to the ground-level, Wolfram and Frantzeskaki (Citation2016) provide a useful overview of epistemologies that can guide policymakers in channeling resources and efforts, including “empowering urban grassroots niches and social innovation” and “configuring urban innovation systems for green economies” (p. 144).

In closing, we bring distill the implications of this argument down to a set of practical skills. The literature has recently provided useful guidance with respect to arming the policy practitioner with an ability to foresee, understand, and recommend policy adaptations for systemic disruption. For example, van der Wal (Citation2017) recommends a set of five characteristics for the “twenty-first century public manager”: smart and savvy, balancing entrepreneurial spirit with an ethical orientation toward public service, willing to collaborate while maintaining the ability to lead, harboring an anticipatory outlook in the short and long-terms, and exhibiting an eagerness to learn as a means to both broaden and deepen expertise. Literature about public service motivation offers similarly useful guidance on understanding and shaping the characteristics of public managers, as usefully summarized by Ritz, Brewer, and Neumann (Citation2016); these concepts can be fruitfully applied to wicked problems and epistemic transition in public policy. We contribute to these discussions by proposing a set of individual capacities that relate specifically to the transition question. Following is a list of ideal characteristics of policy practitioners; this may be framed as a job description for the twenty-first century public servant prepared to function in an age of disruption.

She is a predicament thinker (embraces the concept of wicked problems rather than problems and solutions framed discretely).

She is a complexity thinker (recognizes that global crises and related problems are interconnected, circular, chaotic, and rarely linear).

She is a long-term thinker while sensitive to but not wholly distracted by short-term concerns.

She thrives in systemic, organizational, and institutional flux.

She thrives in the "fog” of macro-transition (the uncertainties of the liminal state between epistemological epochs).

She understands how paradigms shift (whether naturally or by design).

She recognizes that old paradigms are ossified, will persist in steady state, and will obstruct paradigm shifts.

She is open to questioning ossified economic and social systems and institutions that work tangentially to perpetuate outdated policy models.

5. Conclusion

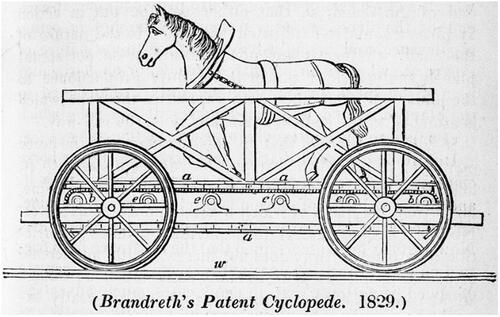

As the 1755 Lisbon earthquake marked a moment of contingency in the Enlightenment, the current moment of reckoning with global crises may mark another contingency in the way policy practice approaches wicked problems. We close with an analogy that illustrates our argument about liminality and public policy. The practice of public policy may be in a transition usefully visualized as Thomas Shaw Brandreth's horse-powered locomotive “cycloped” (Hebert Citation1836). In this depiction of a horse on a conveyer belt, the conveyor belt represents a new technology and the horse an old technology; both interact, and the unit as a whole is thus a hybrid of the old and new (see ). This can be seen conceptually as a partial transition, a tipping point, a moment of emergence, or a state of liminality: a new method is imposing itself on an old one. Full transition occurs when the horse is replaced by a machine engine. For the policy practitioner, what does the horse in the analogy represent? If it represents an anachronistic way of thinking, for example the reduction of wicked problems to a mix of measurable and solvable policy tasks, one might consider the full transition or climax moment as the embrace of predicament thinking and the acknowledgment of the intractability of wicked problems.

Figure 1. Brandreth’s cycloped (Hebert Citation1836).

This implication for policymaking of this analogy and of this article’s argument more generally is that the practitioner operates in a liminal world of partial disruption, where new ideas are only gradually formed or implemented. Ideally, a systemic shock is needed to transform the system into something better capable of addressing wicked problems and crises, but the practical needs of policy practitioners mandate that they be comfortable with liminality in a passing era where old ideas and tools interact with new ones. This article is an attempt to bring the broad-reaching discussion of wicked problems and the transition in thinking needed to address them to practical discussions about actionable guidance for policy practitioners. Structured around individual, organizational, and systemic levels of analytical and political skill development, this guidance seeks to balance the exigencies of uninterrupted public management and service provision with the need to gently nudge the epistemological foundations of public policy toward a more adaptable model, in preparation for what we argue is a gathering storm of systemic wicked problems. In their synchronous and interconnected nature, these problems – including but not limited to climate change, ecological degradation, their threats to human society, and their outsized impacts on vulnerable populations – are confounding analytical and predictive policy models. We argue that technocratization and the data-driven movement are perilously enamored with empiricism as their legacy, reductionism as their problem-framing approach, and initiatives like smart cities as their prescriptions; however, they offer at best an incomplete view of the factors that converge to generate existential crises. Public policy in the twenty-first century – in scholarship and practice – needs to take some intellectual risks by extending internal conversations about wicked problems to debates about systemic instability.

This article has provided one model for how the policy capacity framework can be used to identify specific initiatives for addressing wicked problems, offering a suite of recommendations for developing analytical and political capacities. In so doing, the article provides an example of how an interdisciplinary conversation between critical scholarship and the policy sciences might look. More than a simple punch-line ("a critical theorist, public policy expert, and editor walk into a bar…."), this exercise highlights just how large a gulf there is between efforts to critically conceptualize the underpinnings of modern policy challenges and theories regarding the practice of policymaking, policy change, and policy capacity. In providing practical recommendations for addressing wicked problems, this article also demonstrates that when public policy's epistemological viability is up for debate, the answer must be more nuanced and critical than a simple re-paving of policy models that have been dominant for decades – the period over which systemic policy problems have spiraled into wickedness.

According to Homer-Dixon (Citation2010, 29) a prospective mind “recognizes how little we understand, and how we control even less.” Enlightenment rationality has inspired the study and practice of public policy to address understanding and control in particular ways. The reality for modern scholars is that current systems of knowledge-making are deeply suffused with this epistemic legacy, and the transition must consider their lingering value as well as the importance of new ways of thinking. Existing policy theories therefore maintain their explanatory value even in a policy environment of liminality, as do relatively newer entrants such as policy capacity and tools, but both only in the context of a fresh conversation about shifting epistemological foundations. We argue that if the public policy discipline ignores the elephant-in-the-room – the intractability of global systemic crises like climate change and the failure of existing policy paradigms to provide more than incremental and middling responses – it does so at disservice to scholarly interdisciplinarity and at peril to policy practice and humanity itself. In closing, we acknowledge that discursive tension clearly arises from an attempt to harmonize both epistemics within a single article, but this should not be the case. Aversion to such tension may explain the literature’s unwillingness to put these two starkly divergent perspectives into relief, but this clash has the potential to be unexpectedly productive – pushing scholars to confront and even embrace tension as a starting-point for meaningful dialogue. This article implores the profession to more enthusiastically welcome such dialogues.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 According to Barak (Citation2000), Liebig’s Law states that “yield is proportional to the amount of the most limiting nutrient.” The concept takes a more colloquial tone when describing social scientific phenomena, with terms like “bottlenecks,” “weakest link,” and “theory of constraints” (Goldratt and Cox Citation1984). We argue that the concept can be applied to understand why a focus on optimizing one stage of the policymaking system often fails to make systemic impacts. Hartley (Citation2015) describes this phenomenon as a “constraint theory of governance.”

References

- Allen, C., G. Metternicht, and T. Wiedmann. 2018. “Initial Progress in Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A Review of Evidence from Countries.” Sustainability Science 13 (5): 1453–1467. doi:10.1007/s11625-018-0572-3.

- Bali, A. S., and M. Ramesh. 2019. Assessing health reform: studying tool appropriateness & critical capacities. Policy and Society, 38: 148–166.

- Bali, A. S., G. Capano, and M. Ramesh. 2019. “Anticipating and Designing for Policy Effectiveness.” Policy and Society 38 (1): 1. doi:10.1080/14494035.2019.1579502.

- Barak, P. 2000. Essential Elements for Plant Growth: Law of the Minimum. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin. https://soils.wisc.edu/facstaff/barak/soilscience326/lawofmin.htm

- Barnett, C., and S. Parnell. 2016. “Ideas, Implementation and Indicators: Epistemologies of the Post-2015 Urban Agenda.” Environment and Urbanization 28 (1): 87–98. doi:10.1177/0956247815621473.

- Baumgartner, F. R., and B. D. Jones. 1993. Agendas and Instability in American Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Berg, M., and R. Lidskog. 2018. “Deliberative Democracy Meets Democratised Science: A Deliberative Systems Approach to Global Environmental Governance.” Environmental Politics 27 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1080/09644016.2017.1371919.

- Bhattacharya, D., and M. A. Ali. 2014. “The SDGs–What Are the “Means of Implementation?” Future United Nations Development System.” Briefing 21: 1–4.

- Bostrom, N., A. Dafoe, and C. Flynn. 2018. Public Policy and Superintelligent AI: A Vector Field Approach. Oxford, UK: Governance of AI Program, Future of Humanity Institute, University of Oxford.

- Capano, G., and J. J. Woo. 2017. “Resilience and Robustness in Policy Design: A Critical Appraisal.” Policy Sciences 50 (3): 399–426. doi:10.1007/s11077-016-9273-x.

- Cashore, B., S. Bernstein, D. Humphreys, I. Visseren-Hamakers, and K. Rietig. 2019. “Designing Stakeholder Learning Dialogues for Effective Global Governance.” Policy and Society 38: 118–147.

- Christensen, T., O. M. Laegreid, and P. Laegreid. 2019. “Administrative Coordination Capacity; Does the Wickedness of Policy Areas Matter?” Policy and Society 1–18.

- Christensen, T., and P. Laegreid. 2007. “The Whole‐of‐Government Approach to Public Sector Reform.” Public Administration Review 67 (6): 1059–1066. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00797.x.

- Colebatch, H. K. 2002. “Government and Governmentality: Using Multiple Approaches to the Analysis of Government.” Australian Journal of Political Science 37 (3): 417–435. doi:10.1080/1036114021000026346.

- Crosby, B. C., P. ‘T Hart, and J. Torfing. 2017. “Public Value Creation through Collaborative Innovation.” Public Management Review 19 (5): 655–669. doi:10.1080/14719037.2016.1192165.

- Davoudi, S. 2012. “The Legacy of Positivism and the Emergence of Interpretive Tradition in Spatial Planning.” Regional Studies 46 (4): 429–441. doi:10.1080/00343404.2011.618120.

- de Almeida, A. B. 2009. “The 1755 Lisbon Earthquake and the Genesis of the Risk Management Concept.” In The 1755 Lisbon Earthquake: Revisited, 147–165. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Denhardt, R. B., and J. V. Denhardt. 2000. “The New Public Service: Serving Rather than Steering.” Public Administration Review 60 (6): 549–559. doi:10.1111/0033-3352.00117.

- Elder, M., M. Bengtsson, and L. Akenji. 2016. “An Optimistic Analysis of the Means of Implementation for Sustainable Development Goals: Thinking about Goals as Means.” Sustainability 8 (9): 962. doi:10.3390/su8090962.

- Etzioni, A. 1967. “Mixed-Scanning: A' Third" Approach to Decision-Making.” Public Administration Review 27 (5): 385–392. doi:10.2307/973394.

- Etzioni, A. 1986. “Mixed Scanning Revisited.” Public Administration Review 46 (1): 8–14. doi:10.2307/975437.

- Fischer, F. 2007. “Policy Analysis in Critical Perspective: The Epistemics of Discursive Practices.” Critical Policy Analysis 1 (1): 97–109. doi:10.1080/19460171.2007.9518510.

- Goldratt, E. M., and J. Cox. 1984. The Goal: excellence in Manufacturing. Great Barrington, MA: North River Press.

- Habegger, B. 2010. “Strategic Foresight in Public Policy: Reviewing the Experiences of the UK, Singapore, and The Netherlands.” Futures 42 (1): 49–58. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2009.08.002.

- Hartley, K. 2015. Can Government Think?: Flexible Economic Opportunism and the Pursuit of Global Competitiveness. New York: Routledge Press.

- Hartley, K., and J. Zhang. 2018. “Measuring Policy Capacity Through Governance Indices.” In Policy Capacity and Governance, 67–97. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hartmann, S., A. Mainka, and W. G. Stock. 2017. “Citizen Relationship Management in Local Governments: The Potential of 311 for Public Service Delivery.” In Beyond Bureaucracy, 337–353. Berlin: Springer.

- Head, B. W. 2008. “Wicked Problems in Public Policy.” Public Policy 3 (2): 101–118.

- Head, B. W. 2018. “Forty Years of Wicked Problems Literature: forging Closer Links to Policy Studies.” Policy and Society 1–18. doi:10.1080/14494035.2018.1488797.

- Heberlein, T. A., et al. 1974. “The Three Fixes: Technological, Cognitive and Structural.” In Water and Community Development: Social and Economic Perspectives, edited by Field, 279–296. London: Ann Arbor Science Publishers.

- Hebert, L. 1836. The Engineer's and Mechanic's Encyclopedia, Vol. 2. London: Thomas Kelly.

- Hendriks, C. M. 2009. “Deliberative Governance in the Context of Power.” Policy and Society 28 (3): 173–184. doi:10.1016/j.polsoc.2009.08.004.

- Higgott, R., and J. J. Woo. 2019. A Global ‘Policy Turn’? The Oxford Handbook of Global Policy and Transnational Administration, 310–327.

- Homer-Dixon, T. 2010. The upside of down: catastrophe, creativity, and the renewal of civilization. Island Press.

- Hoppe, R. 2002. “Cultures of Public Policy Problems.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 4 (3): 305–326. doi:10.1080/13876980208412685.

- Howarth, D. 2010. “Power, Discourse, and Policy: Articulating a Hegemony Approach to Critical Policy Studies.” Critical Policy Studies 3 (3–4): 309–335. doi:10.1080/19460171003619725.

- Howlett, M., and S. Geist. 2013. “The Policy-Making Process.” In Routledge Handbook of Public Policy, edited by E. Araral Jr., S. Fritzen, M. Howlett, M. Ramesh, and X. Wu, 17–28. London, New York: Routledge.

- Howlett, M. P., and K. Saguin. 2018. Policy Capacity for Policy Integration: Implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy Research Paper No. 18-06.

- Hsu, A. 2015. “Measuring Policy Analytical Capacity for the Environment: A Case for Engaging New Actors.” Policy and Society 34 (3–4): 197–208.

- Jeffery, R., ed. 2008. Confronting Evil in International Relations. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Johnson, S. 2001. Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities, and Software. New York: Scribner Press.

- Kaivo-Oja, J., J. Marttinen, and J. Varelius. 2002. “Basic Conceptions and Visions of the Regional Foresight System in Finland.” Foresight 4 (6): 34–45. doi:10.1108/14636680210453470.

- Karo, E., and R. Kattel. 2018. “Innovation and the State: Towards an Evolutionary Theory of Policy Capacity.” In Policy Capacity and Governance, 123–150. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kuah, A., and S. H. Lim. 2014. “After Our Singapore Conversation: The Futures of Governance.” Ethos 13: 18–23.

- Kuecker, G., and K. Hartley. 2019. “How smart cities became the urban norm: Power and knowledge in New Songdo City.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers.

- Kuecker, G. D. 2014 (2007). “The Perfect Storm: Catastrophic Collapse in the 21st Century.” In Transitions to Sustainability: Theoretical Debates for a Changing Planet, edited by D. Humphreys and S. Stober, 89–105. Champaign, IL: Common Ground Publishing.

- Kuhn, T. 1962. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kuosa, T. 2011. Practising Strategic Foresight in Government: The Cases of Finland, Singapore, and the European Union. S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies.

- Kurzweil, R. 2005. The Singularity Is near: When Humans Transcend Biology. New York: Viking Press.

- Leitner, C., and C. M. Stiefmueller. 2019. “Disruptive Technologies and the Public Sector: The Changing Dynamics of Governance.” In Public Service Excellence in the 21st Century, 237–274. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lindblom, C. E. 1959. “The Science of Muddling through.” Public Administration Review 19 (2): 79–88. doi:10.2307/973677.

- Lu, Y., N. Nakicenovic, M. Visbeck, and A. S. Stevance. 2015. Policy: Five priorities for the UN sustainable development goals. Nature 520: 432–433.

- Lukensmeyer, C. J., and S. Brigham. 2002. “Taking Democracy to Scale: Creating a Town Hall Meeting for the Twenty‐First Century.” National Civic Review 91 (4): 351–366. doi:10.1002/ncr.91406.

- Morrison, T., and M. Lane. 2005. “What ‘Whole-of-Government’ Means for Environmental Policy and Management: An Analysis of the Connecting Government Initiative.” Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 12 (1): 47–54. doi:10.1080/14486563.2005.10648633.

- Nair, S., and M. Howlett. 2017. “Policy Myopia as a Source of Policy Failure: Adaptation and Policy Learning under Deep Uncertainty.” Policy & Politics 45 (1): 103–118. doi:10.1332/030557316X14788776017743.

- Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rittel, H., and M. Webber. 1973. “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning.” Policy Sciences 4 (2): 155–169. doi:10.1007/BF01405730.

- Ritz, A., G. A. Brewer, and O. Neumann. 2016. “Public Service Motivation: A Systematic Literature Review and Outlook.” Public Administration Review 76 (3): 414–426. doi:10.1111/puar.12505.

- Sachs, J. D. 2012. “From Millennium Development Goals to Sustainable Development Goals.” The Lancet 379 (9832): 2206–2211. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60685-0.

- Sarvajayakesavalu, S. 2015. “Addressing Challenges of Developing Countries in Implementing Five Priorities for Sustainable Development Goals.” Ecosystem Health and Sustainability 1 (7): 1–4. doi:10.1890/EHS15-0028.1.

- Simon, H. A. 1957. Models of Man; Social and Rational. Oxford, England: Wiley.

- Stead, D., and E. Meijers. 2009. “Spatial Planning and Policy Integration: Concepts, Facilitators and Inhibitors.” Planning Theory & Practice 10 (3): 317–332. doi:10.1080/14649350903229752.

- Turnbull, N. 2006. How should we theorise public policy? Problem solving and problematicity. Policy and Society 25 (2): 3–22.

- van der Wal, Z. 2017. The 21st Century Public Manager. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wolfram, M., and N. Frantzeskaki. 2016. “Cities and Systemic Change for Sustainability: Prevailing Epistemologies and an Emerging Research Agenda.” Sustainability 8 (2): 144. doi:10.3390/su8020144.

- Wu, X., M. Howlett, and M. Ramesh, eds. 2018. Policy Capacity and Governance. Studies in the Political Economy of Public Policy. London: Palgrave Macmillan

- Wu, X., M. Ramesh, and M. Howlett. 2015. “Policy Capacity: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Policy Competences and Capabilities.” Policy and Society 34 (3–4): 165–171. doi:10.1016/j.polsoc.2015.09.001.

- Zuckerman-Parker, M., and G. Shank. 2008. “The Town Hall Focus Group: A New Format for Qualitative Research Methods.” The Qualitative Report 13 (4): 630–635.