Abstract

Performance-related-pay (PRP) is a controversial topic. Views about its impact are mixed. Through a meta-analysis of studies in public administration, we aim to provide an evidence-based answer to the question: Does PRP work? Our meta-analysis finds a statistically significant, positive but small population effect size between PRP and employee and performance outcomes. Subgroup analyses show that PRPs impact is contingent upon the type of outcome, geographical context, government level, and data source rather than universal in nature. Effect sizes decrease when performance outcomes are measured as opposed to employee outcomes; in USA and European contexts compared to Asian contexts; at the local level compared to the federal level; and when multiple source or experimental data are used compared to single source data. Based on our findings and PRP literature, we construct a flowchart to support practitioners in deciding whether PRP may “work” for them while avoiding its many and typical pitfalls.

Our meta-analysis demonstrates that the impact of performance-related-pay (PRP) on employee and performance outcomes in public administration is statistically significant and positive; however, the fact that the effects sizes are small leads us to conclude that PRP is not a “magic bullet”.

Intriguingly, performance outcomes are less impacted by PRP than employee-related outcomes like work motivation and job satisfaction, implying that PRP might carry some motivational benefits while its benefits for better performance outcomes are questionable.

PRP seemingly works better in Asia than in Europe or the USA – arguably due to existing predispositions regarding the effects of rewards and monetary incentives – and also seems more effective at the federal than the local government level.

Much of the small positive impact uncovered in this meta-analysis seems to be the result of the type of data used in studies. Specifically, studies using multiple or experimental data show a trivial and statistically insignificant overall impact. Practitioners thus need to carefully assess how they will evaluate PRPs impact to avoid biases due to data type.

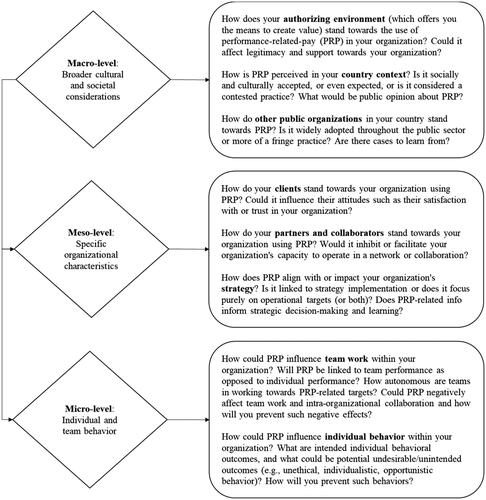

An evidence-based flowchart including questions at the macro (cultural and societal considerations), meso (specific organizational characteristics), and micro (individual and team behavior) level is presented as a support tool for practitioners in deciding upon and designing PRP systems in their organization.

Evidence for practice

Does performance-related-pay (PRP) work? It is a seemingly straightforward question. However, even though governments across the globe have introduced various forms of PRP since the 1980s (Miller, Doherty, and Nadash Citation2013; Perry, Engbers, and Jun Citation2009; Taylor and Beh Citation2013; Wenzel, Krause, and Vogel Citation2019) – Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) reports estimate that two-thirds of civil servants in the developed world are covered by some form of PRP – it is far from clear whether, when, and to what extent PRP actually benefits public-sector employees and organizations.

Nevertheless, PRP has been at the core of many New Public Management and Reinventing Government movements over the past decades, inspired by private sector practices (Pollitt Citation2011; Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2017). Indeed, various forms of PRP have been common practice in the private sector for many decades, particularly at the senior management level. Intriguingly, they have continued as an industry norm despite the turmoil caused by the 2008–2009 global financial crisis and widespread criticism of the “perverse”, unethical, and unintended consequences of high individual rewards tied to the individual and firm-level performance of financial firms (Den Butter, Citation2009; Tang and Chiu Citation2003; Zalm, Citation2009).

Similarly, PRP in public administration has received much critique, despite its popularity. Studies suggest that PRP schemes may “crowd out” prosocial behavior and intrinsic motivation (e.g. Bellé Citation2015; Bénabou and Tirole Citation2006). Moreover, simplistic monetary performance schemes may yield unintended consequences such as goal displacement, and “creaming”, “shirking”, and “cherry picking” by managers and employees: strategic behavior prioritizing often rudimentary tasks that satisfy quantitative performance metrics and therefore result in monetary rewards and recognition (e.g. Heinrich and Marschke Citation2010). Such critiques suggest PRP is about “hitting the target but missing the point”. On the other hand, PRP can help to tackle concerns surrounding goal ambiguity by making it clear what is expected of managers and employees, and how they will be evaluated and rewarded when meeting those expectations. By reducing goal ambiguity, it could be argued PRP also increases employee and performance outcomes (e.g. Jung Citation2014; Chun and Rainey Citation2005).

In short: whether, when, and to what extent PRP works in public administration remains unclear. First, empirical studies typically focus on data from one country, one type of public organization, and one type of outcome – insights across these studies are needed. Second, while there have been review or overview studies on PRP in public administration these do not provide a quantitative integration of evidence across studies (Dahlström and Lapuente Citation2010; Forest Citation2008; Perry, Engbers, and Jun Citation2009). Meta-analytical research methods are particularly apt at uncovering insights across studies by synthesizing individual studies findings into an overall analysis, identifying population effect sizes and variation in effect sizes (e.g. George, Walker, and Monster Citation2019; Gerrish Citation2016).

Hence, to advance our thinking about the impact of PRP and formulate evidence-based recommendations for practitioners, we conduct a meta-analysis of 48 effect sizes from 13 public administration studies on PRP and employee and performance outcomes. While meta-analytical evidence on PRP has been published previously in public administration (Weibel, Rost, and Osterloh Citation2010), it is important to emphasize that the authors here relied on nonpublic administration evidence mostly coming from management or economics journals and the private sector – thus making our meta-analysis stand out by focusing exclusively on public administration studies.

Employee outcomes are defined as all outcomes experienced by public-sector employees, and can be clustered as motivation-related variables (i.e. work motivation, intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation), employee attitudes (i.e. justice and fairness perceptions, and change acceptance) and general employee outcomes (i.e. self-efficacy, autonomy, commitment, Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB), empowerment, satisfaction, clarity, and turnover intention). Performance outcomes relate to both the individual performance of public-sector employees and the organizational performance of public organizations. Finally, PRP is defined as any type of monetary reward incentive scheme tied to the performance of individual public-sector employees, formally embedded in performance appraisal systems.

Incentivizing performance in the public sector

Practitioners and academics alike have long wrestled with the question of how to properly motivate and incentivize government employees and their managers to put in the required effort to perform their tasks; behave ethically; and display the right amount of creativity required for the task at hand.

Indeed, negative cliché-type imagery of Machiavellian, conservative, and self-interested “bureaucrats” motivated by job security and regular office hours has long dominated both popular and academic discourse (e.g. Niskanen Citation1971; Van der Wal Citation2013). However, the recent proliferation of studies into public service motivation (PSM) emphasizing altruism and a desire to work for the greater good, display a countermovement to this cynical discourse (e.g. Perry, Hondeghem, and Wise Citation2010; Ritz, Brewer, and Neumann Citation2016).

These overview studies show that most public sector employees possess high levels of PSM. Moreover, fostering PSM results in higher performance and job satisfaction. As mentioned before, various scholars have argued that overemphasizing extrinsic and monetary incentives may not necessarily sit well with more altruistic motivations.

Context matters

However, emerging non-Western scholarship shows public sector employees in those contexts value extrinsic rewards as much as intrinsic ones (Van der Wal Citation2015; Van der Wal, Mussagulova, and Chen Citation2021). Indeed, motivational dynamics differ substantially between Western, developed settings and non-Western, often developing countries. Moreover, motivational mixes may differ within these clusters, as crude labels like “Western” and “non-Western”, or “developed”, and “developing”, depreciate their enormous diversity, even within the same geographical region (Van der Wal, Mussagulova, and Chen Citation2021). Stereotypes affecting administrative reform paradigms of which PRP has been a prominent feature are hard to refute as research into performance, motivation, and incentives in public administration is almost exclusively Western (Ritz, Brewer, and Neumann Citation2016).

Rare studies in developing or “multiple incentive” settings (Perry Citation2014) yield mixed results. In some cases, public servants prioritize monetary drivers like opportunities to earn additional income and love of money. Indeed, PRP and related monetary performance incentives have been implemented more vigorously and enthusiastically in Asian administrations compared to Western ones (e.g. Aoki and Rawat Citation2020). Intriguingly, in other cases, particularly under conditions of low pay, prosocial drivers matter even more than in Western settings (e.g. Banuri and Keefer Citation2016; Chen and Hsieh Citation2015; Houston Citation2014; Liu and Perry Citation2016).

In addition to the country context, the level of government might also matter for the extent to which PRP is effective, and in what way. So far, studies have produced mixed evidence about the extent to which PRP – often implemented as part of larger administrative reforms – is well received by federal employees (Bertelli Citation2006; Rainey and Kellough Citation2000) vis-à-vis state or local agencies (Anderfuhren-Biget et al Citation2010; Nigro and Kellough Citation2000), while crowding out intrinsic drivers, occurring mostly at the highest levels (Bertelli Citation2006).

Conclusively, whether, when and to what extent PRP actually works in public settings is far from settled, and a meta-analysis is needed to inject substantial evidence into this debate.

Methods and results

Data collection

We conducted a systematic literature review process to identify public administration studies focused on PRP in relation to employee or performance outcomes. First, we used Web-of-Science with the following keywords in a topic search (which includes the article title, abstract, and keywords) on September 7th 2019: performance-based pay, performance-related pay, performance-based compensation, performance-related compensation, pay for performance, merit-based pay, merit-based compensation, merit related pay, merit related compensation, and pay for merit. Only English-language journal articles from Social Sciences Citations Index-classified journals in the Public Administration category of Web-of-Science were included (all of these are filter options within Web-of-Science). This resulted in a list of 93 potentially relevant articles.

Second, we scanned the titles and abstracts of these articles to identify whether these indeed focus on PRP in relation to employee or performance outcomes and provided quantitative evidence (which could be observational or experimental). This resulted in a list of 39 articles. Finally, these articles were read in full to see whether they qualified for the meta-analysis.

In the end, 13 studies remained which cluster 48 effect sizes between PRP and employee or performance outcomes. Most of the studies were observational (11) but we also had two experimental studies in our sample. Studies we excluded from our sample focused on the adoption of PRP as opposed to its impact. In order to be included, studies needed to:

Present quantitative evidence usable for meta-analysis (either correlations or coefficients) and

Clearly examine PRP in relation to employee or performance outcomes – e.g. not public service motivation as this is typically considered an antecedent of these outcomes, finally studies needed to draw on an actual, real sample – actual managers, employees, people working by and large in the public sector.

We provide a list of the included articles (and their characteristics) in . As can be seen from this table, our dataset includes a wide variety of countries (including European and Asian countries, and the USA), organizational settings (including local and federal governments), and respondents (including managers and employees).

Table 1. Included studies and their characteristics.

The effect sizes we obtained from these articles are r-based effect sizes. Specifically, we looked for correlation coefficients between PRP and one of our outcomes in the specific study. If correlation tables were presented, we took the correlation from there, if not we took the correlation from regression coefficients using the formulas discussed by Ringquist (Citation2013). As a robustness check, we tested whether r-based effect sizes collected from correlation tables versus from regression coefficients significantly differed in our sample – they did not.

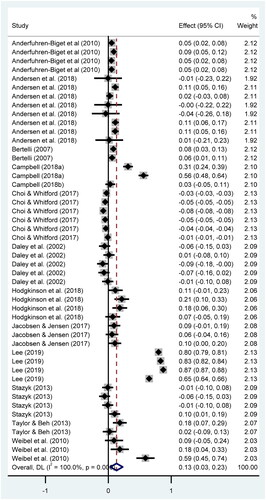

Moreover, shows three outlying effect sizes with a particularly high coefficient (i.e. above 0.70). Again, as a robustness check, we ran all analyses again excluding these three effect sizes and similar results emerged. In addition to collecting the r-based effect sizes, we also coded for each article’s specific outcome, country sample, and level of government. Doing so allowed us to identify potential sources of variation in effect, sizes using subgroup analysis. Coding was initially done by the first author, and replicated by the second author for intercoder reliability. No issues emerged in this process.

offers a forest plot for all identified effect sizes.

Data analysis and results

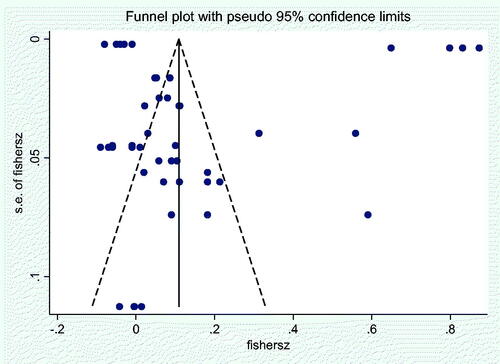

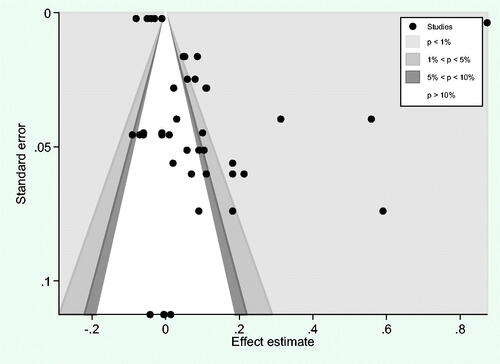

We conducted a random-effects meta-analysis on the identified effect sizes. Random-effects are preferred over fixed-effects when working with real-world data typically used in our field of study. Importantly, the r-based effect sizes underwent Fisher’s Z-transformation as is recommended for meta-analyses in our field (Ringquist Citation2013). and offer funnel plots of all effect sizes and below the figures we discuss several tests of publication bias. shows the results of the analysis. Importantly, we used a subgroup analysis to identify sources of variation in effect sizes and not a meta-regression. This choice resulted from the limited amount of data which hampers the potential of meta-regression. In such instances, subgroup analysis can provide an initial exploration of potential sources of variance. However, an additional robustness check including a meta-regression with one moderator at a time showed the same significant moderators compared to our subgroup analysis.

Table 2. Meta-analysis results.

Both the funnel plot and the contour funnel plot display observations in every quadrant of the plots, which is an argument against publication bias. However, while the funnel plots provide visual tests for asymmetry (which are sometimes hard to interpret as clear evidence for no publication bias), the Egger test (using the metabias command in Stata) provides a statistical test. The test confirms that we cannot reject the null hypothesis of no small-study effects (p = .418), arguing against publication bias. Taken together with our visual tests, this leads us to say that it is unlikely that publication bias is of strong influence on our findings (which is supported by the many small effect sizes and non-significant coefficients we came across when analyzing the studies).

Next, we calculated the overall population effect size. This showed that PRP has a statistically significant, positive, and small impact (<0.20) on the identified employee and performance outcomes. This analysis was replicated but this time on the average effect size per study to control for studies grouping large numbers of effect sizes. The strength of the population effect size remained the same, although significance was lost. Finally, three subgroup analyses were conducted – based on the type of outcome, region, and level of government.

These subgroup analyses demonstrated that PRP has a weaker positive impact on performance compared to the other outcomes, that PRP’s positive impact in Asia is stronger than in Europe and the US, and that PRP has a stronger positive impact at the federal level of government compared to the local level. Importantly, for Asian countries and federal levels of government, the strength of the impact of PRP actually becomes closer to moderate than small (>0.20). The data show effect sizes coming from a single source are much stronger compared to those coming from multiple or experimental sources, which indicates that much of the (still small) positive impact of PRP identified in the other analyses could actually be the result of common source bias that inflated correlations.

Evidence-based recommendations

Our study aimed to answer the question: Does PRP work? As often in our field of study, the answer is not as straightforward as one might hope. Indeed, PRP yields benefits at the federal government level, in Asian countries, and for employee outcomes. However, in general, its impact is small at best.

So, what do these findings imply for public managers (thinking of) using PRP in their organizations? Based on our observations, inspired by other systematic reviews on PRPs impact in public organizations (Dahlström and Lapuente Citation2010; Forest Citation2008; Perry, Engbers, and Jun Citation2009; Weibel, Rost, and Osterloh Citation2010), we constructed an evidence-based support tool for practice (shown in ). Our flowchart acknowledges the inherent multilevel nature of public management by focusing on macro, meso, and micro-level questions public managers ought to reflect on when thinking of using PRP. Rather than being an exhaustive checklist, this flowchart offers useful points of orientation for a comprehensive discussion on the value of PRP in public organizations.

It is important to emphasize this is a preliminary meta-analysis based on a first set of public administration studies on PRP. Ideally, a meta-analysis also includes meta-regression. Due to the limited dataset, we conducted subgroup analyses instead. While it is important to take stock of PRP literature for practical as well as scholarly purposes, we acknowledge more work is needed to allow us to make broadly generalizable statements on the impact of PRP.

Nonetheless, the face validity of our findings is high, adhering to our theoretical expectations while also being supported by meta-analyses from other disciplines (e.g. Pham, Nguyen, and Springer Citation2021). To conclude, while PRP is not a magical bullet for increasing employee and performance outcomes, we hope our flowchart can support strategic thinking and more careful implementation of PRP, aiding public managers to move beyond adopting PRP because it seems fashionable by acknowledging key environmental, organizational, and individual considerations.

Avenues for future research

Based on the meta-analysis, we suggest three avenues for future study. First, more comprehensive comparative survey studies and case studies should be conducted into the nature and origin of the variation in PRP impact between Western and Eastern public organizations. Recent studies into the extent to which reward reforms have been introduced in Asian countries (Aoki and Rawat Citation2020), and motivational profiles and cultures for civil servants are more extrinsically oriented in the East compared to the West (Mussagulova and Van der Wal Citation2021) provide rudimentary input for building theoretical propositions for the variations found in our study.

Second, conceptual and empirical endeavors are needed to aid scholars in distinguishing more specifically between different types of (desired and intended) performance outcomes, ranging from motivational and HR-related employee outcomes to quantifiable, results-oriented outcomes. Indeed, the results of the current study show how the impact of PRP varies significantly for various types of performance outcomes. In addition to quantitative studies, qualitative research in particular can further situate how and why this impact varies in relation to the applied performance regime and its underlying performance logics (see, Virani and Van der Wal Citation2023).

Third and final, the context of PRP seemingly becoming a less widespread practice in the private sector due to increased public scrutiny and the move toward environmental stewardship, social responsibility, and corporate governance (ESG) based reporting and accountability expectations, merits a new wave of comparative studies into PRPs performance impact across sectors. Traditional monetary rewards tied to individual (financial) performance may become less important and desirable over time, which begs the intriguing question regarding what business may learn from the government here, rather than the other way around.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

ReferencesNote: References marked by * are included in the meta-analysis

- *Anderfuhren-Biget, S., F. Varone, D. Giauque, and A. Ritz. 2010. “Motivating Employees of the Public Sector: Does Public Service Motivation Matter?” International Public Management Journal 13 (3): 213–246. doi:10.1080/10967494.2010.503783.

- *Andersen, L. B., S. Boye, and R. Laursen. 2018. “Building Support? The Importance of Verbal Rewards for Employee Perceptions of Governance Initiatives.” International Public Management Journal 21 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1080/10967494.2017.1329761.

- Aoki, N., and S. Rawat. 2020. “Performance-Based Pay: Investigating Its International Prevalence in Light of National Contexts.” The American Review of Public Administration 50 (8): 865–879. doi:10.1177/0275074020919995.

- Banuri, S., and P. Keefer. 2016. “Pro-Social Motivation, Effort and the Call to Public Service.” European Economic Review 83: 139–164. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2015.10.011.

- Bellé, N. 2015. “Performance‐Related Pay and the Crowding out of Motivation in the Public Sector: A Randomized Field Experiment.” Public Administration Review 75 (2): 230–241. doi:10.1111/puar.12313.

- Bénabou, R., and J. Tirole. 2006. “Incentives and Prosocial Behavior.” American Economic Review 96 (5): 1652–1678. doi:10.1257/aer.96.5.1652.

- Bertelli, A. M. 2006. “Motivation Crowding and the Federal Civil Servant: Evidence from the U.S. Internal Revenue Service.” International Public Management Journal 9 (1): 3–23. doi:10.1080/10967490600625191.

- *Bertelli, A. M. 2006. “Determinants of Bureaucratic Turnover Intention: Evidence from the Department of the Treasury.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 17 (2): 235–258. doi:10.1093/jopart/mul003.

- *Campbell, J. W. 2018a. “Felt Responsibility for Change in Public Organizations: General and Sector-Specific Paths.” Public Management Review 20 (2): 232–253. doi:10.1080/14719037.2017.1302245.

- *Campbell, J. W. 2018b. “Efficiency, Incentives, and Transformational Leadership: Understanding Collaboration Preferences in the Public Sector.” Public Performance & Management Review 41 (2): 277–299. doi:10.1080/15309576.2017.1403332.

- Chen, C.-A., and C.-W. Hsieh. 2015. “Does Pursuing External Incentives Compromise Public Service Motivation? Comparing the Effects of Job Security and High Pay.” Public Management Review 17 (8): 1190–1213. doi:10.1080/14719037.2014.895032.

- *Choi, S., and A. B. Whitford. 2017. “Employee Satisfaction in Agencies with Merit-Based Pay: Differential Effects for Three Measures.” International Public Management Journal 20 (3): 442–466. doi:10.1080/10967494.2016.1269860.

- Chun, Y. H., and H. G. Rainey. 2005. “Goal Ambiguity and Organizational Performance in US Federal Agencies.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 15 (4): 529–557. doi:10.1093/jopart/mui030.

- Dahlström, C., and V. Lapuente. 2010. “Explaining Cross-Country Differences in Performance-Related Pay in the Public Sector.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 20 (3): 577–600. doi:10.1093/jopart/mup021.

- *Daley, D., M. L. Vasu, and M. B. Weinstein. 2002. “Strategic Human Resource Management: Perceptions Among North Carolina County Social Service Professionals.” Public Personnel Management 31 (3): 359–375. doi:10.1177/009102600203100308.

- den Butter, F. A. G. 2009. “Falen Van De Financiële Markten.” Bank & Effectenbedrijf 59: 14–19.

- Forest, V. 2008. “Performance-Related Pay and Work Motivation: theoretical and Empirical Perspectives for the French Civil Service.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 74 (2): 325–339. doi:10.1177/0020852308089907.

- George, B., R. M. Walker, and J. Monster. 2019. “Does Strategic Planning Improve Organizational Performance? A Meta‐Analysis.” Public Administration Review 79 (6): 810–819. doi:10.1111/puar.13104.

- Gerrish, E. 2016. “The Impact of Performance Management on Performance in Public Organizations: A Meta‐Analysis.” Public Administration Review 76 (1): 48–66. doi:10.1111/puar.12433.

- Heinrich, C. J., and G. Marschke. 2010. “Incentives and Their Dynamics in Public Sector Performance Management Systems.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 29 (1): 183–208. doi:10.1002/pam.20484.

- *Hodgkinson, I. R., P. Hughes, Z. Radnor, and R. Glennon. 2018. “Affective Commitment Within the Public Sector: Antecedents and Performance Outcomes Between Ownership Types.” Public Management Review 20 (12): 1872–1895. doi:10.1080/14719037.2018.1444193.

- Houston, D. J. 2014. “Public Service Motivation in the Post-Communist State.” Public Administration 92 (4): 843–860. doi:10.1111/padm.12070.

- *Jacobsen, C. B., and L. E. Jensen. 2017. “Why Not “Just for the Money”? An Experimental Vignette Study of the Cognitive Price Effects and Crowding Effects of Performance-Related Pay.” Public Performance & Management Review 40 (3): 551–580. doi:10.1080/15309576.2017.1289850.

- Jung, C. S. 2014. “Organizational Goal Ambiguity and Job Satisfaction in the Public Sector.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 24 (4): 955–981. doi:10.1093/jopart/mut020.

- *Lee, H. W. 2019. “Moderators of the Motivational Effects of Performance Management: A Comprehensive Exploration Based on Expectancy Theory.” Public Personnel Management 48 (1): 27–55. doi:10.1177/0091026018783003.

- Liu, B., and J. L. Perry. 2016. “The Psychological Mechanisms of Public Service Motivation. A Two-Wave Examination.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 36 (1): 4–30. doi:10.1177/0734371X14549672.

- Miller, E. A., J. Doherty, and P. Nadash. 2013. “Pay for Performance in Five States: Lessons for the Nursing Home Sector.” Public Administration Review 73 (s1): S153–S163. doi:10.1111/puar.12060.

- Mussagulova, A., and Z. Van der Wal. 2021. “All Still Quiet on the Non-Western Front?” Public Service Motivation Scholarship in Non-Western Contexts: 2015–2020.” Asia Pacific Journal of Public Administration 43 (1): 23–46. doi:10.1080/23276665.2020.1836977.

- Nigro, L. G., and J. E. Kellough. 2000. “Civil Service Reform in Georgia: Going to the Edge.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 20 (4): 41–54. doi:10.1177/0734371X0002000405.

- Niskanen, William A. 1971. Bureaucracy and Representative Government. Chicago: Aldine-Atherton.

- Perry, J. L. 2014. “The Motivational Basis of Public Service: Foundations for the Third Wave of Research.” Asia Pacific Journal of Public Administration 36 (1): 34–47. doi:10.1080/23276665.2014.892272.

- Perry, J. L., T. A. Engbers, and S. Y. Jun. 2009. “Back to the Future? Performance-Related Pay, Empirical Research, and the Perils of Persistence.” Public Administration Review 69 (1): 39–51. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2008.01939_2.x.

- Perry, J. L., A. Hondeghem, and L. R. Wise. 2010. “Revisiting the Motivational Bases of Public Service: Twenty Years of Research and an Agenda for the Future.” Public Administration Review 70 (5): 681–690. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02196.x.

- Pham, L. D., T. D. Nguyen, and M. G. Springer. 2021. “Teacher Merit Pay: A Meta-Analysis.” American Educational Research Journal 58 (3): 527–566. doi:10.3102/0002831220905580.

- Pollitt, C. 2011. “30 Years of Public Management Reforms: Has There Been a Pattern?” World Bank Blog: Governance for Development Available at: http://blogs.worldbank.org/governance/30-years-of-public-managementreforms-has-there-been-a-pattern

- Pollitt, C., and G. Bouckaert. 2017. Public Management Reform: A Comparative Analysis-Into the Age of Austerity. 4th Ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rainey, H. G., and J. E. Kellough. 2000. “Civil Service Reform and Incentives in the Public Service.” In The Future of Merit, edited by J. P. Pfiffner and D. A. Brook, 127–145. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press.

- Ringquist, E. 2013. Meta-Analysis for Public Management and Policy. New York: Jossey-Bass

- Ritz, A., G. A. Brewer, and O. Neumann. 2016. “Public Service Motivation: A Systematic Literature Review and Outlook.” Public Administration Review 76 (3): 414–426. doi:10.1111/puar.12505.

- *Stazyk, E. C. 2013. “Crowding out Public Service Motivation? Comparing Theoretical Expectations with Empirical Findings on the Influence of Performance-Related Pay.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 33 (3): 252–274. doi:10.1177/0734371X12453053.

- Tang, T. L.-P., and R. K. Chiu. 2003. “Income, Money Ethic, Pay Satisfaction, Commitment, and Unethical Behavior: Is the Love of Money the Root of Evil for Hong Kong Employees?” Journal of Business Ethics 46 (1): 13–30. doi:10.1023/A:1024731611490.

- *Taylor, J., and L. Beh. 2013. “The Impact of Pay-for-Performance Schemes on the Performance of Australian and Malaysian Government Employees.” Public Management Review 15 (8): 1090–1115. doi:10.1080/14719037.2013.816523.

- Van der Wal, Z. 2013. “Mandarins Vs. Machiavellians? On Differences Between Work Motivations of Political and Administrative Elites.” Public Administration Review 73 (5): 749–759. doi:10.1111/puar.12089.

- Van der Wal, Z. 2015. “All Quiet on the non-Western Front?” A Review of Public Service Motivation Scholarship in non-Western Contexts.” Asia Pacific Journal of Public Administration 37 (2): 69–86. doi:10.1080/23276665.2015.1041223.

- Van der Wal, Z., A. Mussagulova, and C. A. Chen. 2021. “Path‐Dependent Public Servants: Comparing the Influence of Traditions on Administrative Behavior in Developing Asia.” Public Administration Review 81 (2): 308–320. doi:10.1111/puar.13218.

- Virani, A. A., and Z. Van der Wal. 2023. “Enhancing the Effectiveness of Public Sector Performance Regimes. A Proposed Causal Model for Aligning Governance Design with Performance Logics.” Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 6 (1): 54–65. doi:10.1093/ppmgov/gvac026.

- *Weibel, A., K. Rost, and M. Osterloh. 2010. “Pay for Performance in the Public Sector—Benefits and (Hidden) Costs.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 20 (2): 387–412. doi:10.1093/jopart/mup009.

- Wenzel, A.-K., T. A. Krause, and D. Vogel. 2019. “Making Performance Pay Work: The Impact of Transparency, Participation, and Fairness on Controlling Perception and Intrinsic Motivation.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 39 (2): 232–255. doi:10.1177/0734371X17715502.

- Zalm, G. 2009. “The Forgotten Risk: Financial Incentives.” De Economist 157 (2): 209–213. doi:10.1007/s10645-009-9111-z.