ABSTRACT

This systematic literature review (SLR) investigates the enablers and constraints which impact the enactment of Traditional Indigenous Games within curriculum. SLR methodology was used to identify all potential literature within Australia and internationally, between February 2022 and April 2022. Searches were limited to peer-reviewed literature, written in English and published between 2002 and 2022. Search protocols employed to investigate relevant literature were based upon the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) model with the following databases explored: A+ Education via Informit online, AEI ATSIS, ERIC Proquest, Taylor & Francis and Sage Journals (Education). The following search terms were used: ALL FIELDS, (‘Traditional Indigenous games’ OR ‘Indigenous games’ OR Yulunga OR ‘Indigenous sport’ OR ‘Aboriginal sports’ OR ‘Torres Strait Islander sports’ AND ‘Australian curriculum’ OR ‘cross curriculum priorities’ OR ‘Indigenous pedagogy’ AND ‘Indigenous perspectives’ OR ‘Indigenous knowledge’s’ OR ‘Embedding Indigenous perspectives’ AND ‘health and physical education’ OR ‘physical education teacher education’ OR ‘health & PE’ AND ‘Cultural competency’ OR ‘cultural safety’ AND ‘Initial teacher education’ OR ‘pre-service physical education teachers’). Results suggest that culturally relevant pedagogy is a dominant enabler, whilst curriculum and teacher cultural awareness are dominant constraints which impact the enactment of Traditional Indigenous Games within curriculum.

Introduction

Coloniser-settler conflict between IndigenousFootnote1 and non-Indigenous people has led to significant marginalisation of Indigenous knowledges and perspectives within the Australian education system (Williams, Citation2016). Since 1788, Indigenous people have been subjected to discrimination and systemic disadvantage perpetrated by Western culture (Bodkin-Andrews & Carlson, Citation2016). Furthermore, ‘Indigenous people have experienced displacement, been the targets of genocidal policies and practices, had families destroyed through the forcible removal of children, and continue to face the stresses of living in a racist world that systematically devalues Indigenous culture’ (Dudgeon et al., Citation2010, p. 38).

The gap in educational outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students is an international phenomenon. International policy flaws are identified within research from Canada (Neeganagwedgin, Citation2013), USA (Sato et al., Citation2013), Turkey (Aypay, Citation2016), Sweden (Barker, Citation2019), South Africa (Nxumalo & Mncube, Citation2018), New Zealand (Rata, Citation2012), Botswana (Lyoka, Citation2007), Zimbabwe (Madondo & Tsikira, Citation2021), Brazil (Pereira & Venâncio, Citation2021), UK (Santoro & Kennedy, Citation2016), Tanzania (Shehu, Citation2004) and Finland (Veintie, Citation2013), as well as Australia (Gray & Beresford, Citation2008). These policy flaws illustrate the failure to effectively embed Indigenous knowledges and perspectives within their respective curriculum systems (Villegas & Lucas, Citation2002). For example, Neeganagwedgin (Citation2013) stated in a review of Aboriginal education in Canada, that current policy frameworks are simply designed to identify deficiencies for Aboriginal students and are counterproductive to educational success. Furthermore, Gray and Beresford (Citation2008) suggest that policy reform is required within the current education system to improve educational outcomes for Indigenous students.

This also has significance across the Asia-Pacific region, with countries such as Indonesia and Vietnam endeavouring to implement policy compliance measures (Moodie & Patrick, Citation2017). However, some countries such as New Zealand have managed to make positive inroads regarding the discrepancies between Indigenous and non-Indigenous education for Māori students through the introduction of specialised primary and secondary schools (Kura Kaupapa Māori) where Māori has become the primary language of instruction and an effective way to embed Māori knowledges and perspectives (Rata, Citation2012). Notably, flaws regarding curriculum have also been identified.

In September 2007, following decades of planning and preparatory work, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) (United Nations (General Assembly), Citation2007). The UNDRIP is the most comprehensive international framework for the rights of Indigenous people (Rosnon et al., Citation2019). Within the Australian education system, the UNDRIP prompted positive change with a renewed focus on improving educational outcomes (Bishop, Citation2021). The UNDRIP supports the rights of Indigenous peoples through self-determining education through Article 14 (1) ‘Indigenous peoples have the right to establish and control their educational systems and institutions providing education in their own languages, in a manner appropriate to their cultural methods of teaching and learning’ (United Nations (General Assembly), Citation2007).

The Declaration provided a new impetus for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians to work together to close educational gaps (Kukutai & Taylor, Citation2016). Through policy enactment and Indigenous focus, educational outcomes for Indigenous students are continuing to improve (Morrison et al., Citation2019). However, the inclusion of Indigenous knowledges and perspectives within the Australian education system, is still viewed from a deficit standpoint (Burgess et al., Citation2022)

Historically, within Health and Physical Education (HPE) curriculum, inclusion of Indigenous Australian culture has been tokenistic (Whatman et al., Citation2017). This lack of Indigenous knowledges and perspectives within curriculum is due to Australia’s dependence upon sports and games steeped in colonial history, with traditional sports such as Rugby League, Rugby Union, Australian Rules Football, Cricket, Netball and basketball favoured over non-traditional sports within the curriculum (Evans et al., Citation2017). This has led to conflicting priorities between curriculum agendas and the needs of Indigenous people, with critics citing limited cultural integration as being detrimental to Indigenous students (Whatman et al., Citation2017). Recently, advancements have been made within curriculum to include the teaching of non-traditional sports such as Traditional Indigenous Games and Sports (TIGaS) (Edwards, Citation2008), as well as Indigenous concepts of health (Evans et al., Citation2017). Resources are available to assist HPE teachers with this process such as Yulunga: Traditional Indigenous Games (Edwards, Citation2008). Yulunga provides examples of Traditional Indigenous Games which can be implemented across K-12, provided there is meaning and purpose behind the objective as opposed to a tokenistic perspective (Dinan Thompson et al., Citation2014).

Concerns for teachers’ abilities to facilitate cultural diversity within HPE contexts have been raised for many decades (Barker, Citation2019; Schmidlein et al., Citation2014; Whatman et al., Citation2017). A major contributor to this has been the fact that physical education teacher education (PETE) students typically enter the profession from privileged white middle-class backgrounds (Barker, Citation2019). This results in a ‘widening’ of cultural competency needed to provide culturally inclusive teaching practices (Whatman et al., Citation2017), and criticism of teacher educators and PETE programs for failing to provide appropriate ‘pedagogical toolboxes’ to navigate cultural inclusivity (Barker, Citation2019).

This SLR was undertaken to understand the current scope of literature pertaining to embedding Indigenous Knowledges and perspectives from a TIGaS perspective within curriculum. The findings of this review reveal how learning outcomes can be strengthened for Indigenous students through embedding Indigenous knowledges and perspectives. To provide an effective and inclusive education system within Australia, it is crucial that current pedagogical approaches and strategies are examined to ensure an effective and inclusive curriculum for all. In this paper, we present a systematic review of literature of TIGaS within curriculum. We identified findings which could be broadly categorised as enablers or constraints of TIGaS which included culturally relevant pedagogy identified as a prominent enabler whilst curriculum and teacher cultural awareness are investigated as prominent constraints. This paper provides a summary of results and analysis and discussion of the most prominent enablers and constraints.

Methodology

Research design

This qualitative investigation was designed to evaluate current evidence pertaining to the research question: what does the literature say are the enablers and constraints which impact the enactment of Traditional Indigenous Games (and Sports) within curriculum? To effectively address this question, a systematic review methodology (Moher et al., Citation2009), was used to identify potential literature within Australia and internationally. This approach was used to identify if contributing effects were constant throughout literature, as well as providing an opportunity to identify potential gaps within current literature. The PRISMA approach was utilised due to its highly effective evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews, ensuring a transparent account of why the review was undertaken, the process that was followed and the results that were found (Moher et al., Citation2009).

Data collection

Search strategy

A systematic search of the current literature was completed between February 2022 and April 2022. Search protocols were based upon the PRISMA model (Moher et al., Citation2009). The following databases were explored: A + Education via Informit online, AEI ATSIS (Australian Education Index and Theses), ERIC Proquest, Taylor & Francis and Sage Journals (Education).

Searches were limited to peer-reviewed literature, written in English and published in the past 20 years (2002–2022). Additionally, search alerts were set for the search word combinations to ensure any literature published after the search date was included in the literature review and additional articles were identified via reference lists of literature located within the search. The following search key terms were used: ALL FIELDS (keywords will appear in any field; e.g. title, abstract, full text or any other field), (‘Traditional Indigenous games’ OR ‘Indigenous games’ OR Yulunga OR ‘Indigenous sport’ OR ‘Aboriginal sports’ OR ‘Torres Strait Islander sports’ AND ‘Australian curriculum’ OR ‘cross curriculum priorities’ OR ‘Indigenous pedagogy’ AND ‘Indigenous perspectives’ OR ‘Indigenous knowledges’ OR ‘Embedding Indigenous perspectives’ AND ‘health and physical education’ OR ‘physical education teacher education’ OR ‘health & PE’ AND ‘Cultural competency’ OR ‘cultural safety’ AND ‘Initial teacher education’ OR ‘pre-service physical education teachers’).

Inclusion criteria

For inclusion in the review, studies must have met the following criteria:

A primary focus on Indigenous games and/or sports.

Research since 2002.

Research relevant to embedding Indigenous knowledges and perspectives within curriculum.

Full-text articles.

Written in English.

Selection of studies

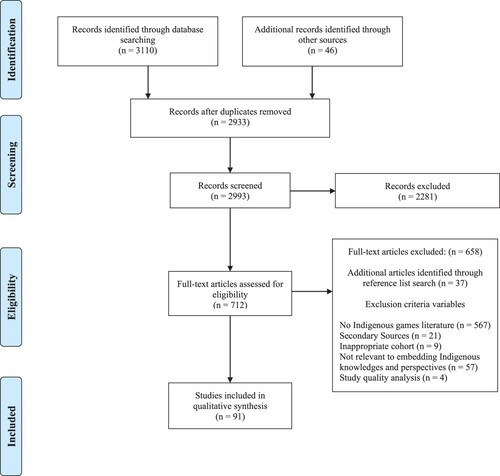

shows the approach taken for the systematic literature search. A total of 3155 identified articles were first stored in reference management software package (Endnote X9.2), before duplicates were removed using automated and manual screening processes. Articles were then screened by titles for keywords, followed by abstracts. Studies that contained the key terms ‘Traditional Indigenous Games’, ‘Indigenous Games’ or ‘Cultural Games’ within the title were retained for review. Remaining studies were then assessed based upon the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The remaining studies that met the inclusion criteria and were selected for review, were then assessed for methodological study quality. Grey literature pertinent to the research question was also investigated.

Figure 1. PRISMA search strategy for literature reporting Traditional Indigenous Games and Sports, 2002–2022. Source: adapted from Moher et al. (Citation2009).

Assessment of methodological study quality for included qualitative studies

Methodological quality was assessed using a quality assessment tool used for qualitative studies developed by Long and Godfrey (Citation2004) and Ryan et al. (Citation2007). Each study was measured against six criteria (research design, sources, theoretical framework, ethical implications, methodology and contribution to the field). Each element of the six criteria was scored as either 1 if met, 0.5 if met but not well described and 0 if not met. Scores were aggregated across each criteria to provide a total score out of 6. Any studies that did not meet a total score of 3/6 were removed from the final list of included studies ().

Table 1. Results of quality assessment for qualitative studies.

Findings

Several key findings arose from the SLR which have been thematically sorted into enablers and constraints to implementing Traditional Indigenous Games ().

Table 2. Findings from Literature.

To reduce the number of findings, only the following key results which were identified to have 30 or more hits within the literature, are discussed for enablers (culturally relevant pedagogy), and constraints (curriculum and teacher cultural awareness). These results were selected for synthesis because of the margin between findings, i.e. the next enabler (n = 9) and the next constraint (n = 15).

Enablers

Attempts to Indigenise curriculum can be perceived as developing an ‘impoverished version of Aboriginal pedagogy and the promotion of corrupted understandings of Indigenous knowledge’ (Williamson & Dalal, Citation2007, p. 51). What is required however, is an understanding of the complexities and tensions which arise when negotiating the interface between Indigenous and non-Indigenous knowledge systems (Nakata, Citation2002; Williamson & Dalal, Citation2007). To address this culturally relevant pedagogy was identified as an enabler to promote effective implementation of Indigenous perspectives.

Culturally relevant pedagogy

Culturally relevant pedagogy can be defined as an approach to teaching and learning which utilises ‘cultural characteristics, experiences, and perspectives of ethnically diverse students as conduits for teaching them more effectively’ (Gay, Citation2002, p. 106). For all Indigenous groups, Indigenous knowledge is a lived world experience which provides a construct between people and their environments and cultural identity (Pill et al., Citation2021). Since colonisation of Australia, Indigenous students have been severely disadvantaged by a Eurocentric schooling system which has resulted in their cultural identity being taken away from them (De Plevitz, Citation2007). Following what can only be described as government failure to ‘Close the Gap’ on educational outcomes for Indigenous students, urgent action is needed from educational stakeholders and all levels of government to address curriculum and pedagogical reform (Maxwell et al., Citation2018). Within the Australian education system, classrooms are becoming increasingly diverse (Williams & Pill, Citation2019). As such, the promotion of cultural inclusion through varying policy approaches such as the Australian Professional Standards for Teaching Leadership is welcomed, however, critics argue that policy outcomes are focused on Eurocentric pedagogies (Williams & Pill, Citation2019). A recent approach discussed within the SLR which has the potential to improve learning outcomes for Indigenous students is CRP. This approach is aligned with various other multicultural pedagogies and is also referred to as culturally responsive pedagogy (Boon & Lewthwaite, Citation2015), culturally responsive teaching (Gay, Citation2002) and culturally informed pedagogy (Legge, Citation2011).

Based upon a sociocultural understanding of learning, CRP propositions curriculum and pedagogy as culturally based, including HPE (Wrench & Garrett, Citation2021a). For example, Vass (Citation2012) within his study of exploring deficit discourses within Indigenous education, advocated that curriculum and pedagogies should be diverse, socio-politically grounded and culturally responsive. Furthermore, Sleeter (Citation2011) in her paper based upon strengthening CRP raised concerns that within school settings this could be perceived as ‘tokenistic’ forms of Indigenous alignment through ‘ticking the box’. However, if implemented effectively, CRP can promote student achievement by facilitating a sense of belonging within the classroom (Rahman, Citation2013). Essentially, CRP is the ability of teachers to incorporate specific strategies that inform their pedagogical approaches to support student learning (Lewthwaite et al., Citation2014). Villegas and Lucas (Citation2002), suggest that teachers can achieve this in several ways including using students’ prior knowledge and cultural backgrounds to inform learning, be socioculturally conscious and have positive views of students from diverse backgrounds, understand their learners and how they construct knowledge and finally, use pedagogical approaches and strategies in the classroom that cater for the learning needs of all students.

If teachers develop appropriate levels of CRP within their teaching practices and understand the impact that this will have on students, this may provide greater avenues of alignment between culturally based curriculum and teaching practices. For example, Vass (Citation2012) suggests that for year 5 students, only 63.4% of Indigenous students were above the national benchmark in literacy and numeracy, compared to 92.6% of non-Indigenous students. When examining TIGaS within curriculum, HPE educators who understand how to implement CRP within teaching and learning experiences, are more effective teachers with the potential to close the educational gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students (Wrench & Garrett, Citation2021a). Therefore, it is recommended that all teachers be knowledgeable in this framework to ensure best practice teaching and learning experiences for the implementation of TIGaS as well as ensuring professional teaching standards are met (Brown-Jeffy & Cooper, Citation2011).

Constraints

Cultural barriers between Indigenous students and western education systems have resulted in disparities between lived home experiences and western ways of schooling (Evans et al., Citation2017). These barriers make it difficult for Indigenous students to utilise cultural capital to improve educational outcomes. This relationship is causal and while education systems are continuing to develop policy initiatives to improve educational outcomes (Papp, Citation2016), constraints such as curriculum and teacher cultural awareness are still contributing to this divide.

Curriculum

The Australian Curriculum (AC) has seen significant updates since its inception in 2010, with HPE introduced in 2014 (Macdonald et al., Citation2018). Within the HPE landscape, the Australian Curriculum: Health and Physical Education (AC: HPE), has been considered a gateway to embedding Indigenous knowledges and perspectives (Whatman et al., Citation2017) and mobilising the CCP of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures (Pill et al., Citation2021). The latter is a welcome inclusion which has the potential to benefit Indigenous students however, Nakata (Citation2011) suggests proceeding with caution with objectives potentially viewed as tokenistic, within overarching priorities of an AC satisfying the needs of all stakeholders. Further concerns suggested a tokenistic approach is in place rather than meaningful and valued approaches (Williams, Citation2016). The concerns of Nakata (Citation2011) and Williams (Citation2016) are valid if the CCP of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures is not viewed as a positive reform to embed Indigenous knowledges and perspectives.

According to the AC, the CCP ‘provides an opportunity for all young Australians to gain a deeper understanding and appreciation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures, knowledge traditions and holistic world views’ (ACARA, Citation2016). Williams (Citation2018) study of Aboriginal games indicates that this policy agenda may not result in a greater focus of social justice issues within HPE. For example, he and Pill et al. (Citation2021) have raised concerns with teachers’ ability to implement the CCP. Evans et al. (Citation2017) further support this notion by suggesting that many teachers are reluctant to try and teach Indigenous perspectives for fear of ‘cultural trespass’ and simply because they do not know how. Contradictions appear to have emerged with ‘priorities’ to embed CCP’s, but often with little regard to how those CCP’s should be implemented (Booth & Allen, Citation2017; Salter & Maxwell, Citation2016). It is suggested that CCP’s should be embedded where educationally relevant (ACARA, Citation2016). However, within AC: HPE, exactly where Indigenous knowledges and perspectives can be embedded is still open for debate (Evans et al., Citation2017; Whatman & Meston, Citation2016). This results in a key constraint because teachers are unaware of how to position TIGaS within curriculum. Some might regard open possibilities to include TIGaS to be an enabler, but research into teacher agency (Johnson et al., Citation2015), particularly early career teachers, shows that teachers want more explicit guidance about what to teach and when – hence why it can be seen as a constraint.

Bodkin-Andrews and Carlson (Citation2016) within their study exploring the legacy of racism for Indigenous people within education, argue that the Westernised curriculum, contributes to ‘cultural extermination’ for Indigenous people. However, it has been reported that a ‘revival’ of TIGaS (Williams, Citation2016), has allowed HPE teachers the opportunity to embed CCP’s. Literature gaps appear to exist regarding how Indigenous knowledges can be represented and embedded within HPE teaching and learning experiences (Pill et al., Citation2021). Within the current HPE landscape, the consensus amongst educators suggests that the inclusion of TIGaS in HPE classes has the potential to facilitate the embedding of Indigenous perspectives (Williams, Citation2016). Evans et al. (Citation2017) states the importance of HPE being a viable option to embed TIGaS as this is a key learning area that allows both Indigenous and non-Indigenous students the opportunity to actively engage with Indigenous culture. Therefore, if the CCP of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures is not actively embedded within HPE, there is the possibility that it may not be embedded within the curriculum at all.

The role of curriculum is ambiguous and constraining as curriculum directives are not explicit in the development of CRP for teachers resulting in curriculum gaps which are being exploited by teachers (Evans et al., Citation2017). The constraint is that not all teachers can identify where TIGaS should be positioned within curriculum. However, if it were more explicit teachers may be required to have a greater understanding of cultural awareness and be more inclined to seek out further opportunities to embed Indigenous knowledges and perspectives within curriculum.

Teacher cultural awareness

Preparing culturally aware teachers who can provide effective teaching and learning experiences for all students is the fundamental focus for educational stakeholders (Turner, Citation2007). Teacher cultural awareness (TCA) requires competence to enhance teaching and learning experiences for students from diverse cultural backgrounds (Sarraj et al., Citation2015). The embedding of Indigenous knowledges and perspectives is complex and although stipulated in numerous curriculum documents and professional standards, it is still easy to avoid for teachers (Booth & Allen, Citation2017). Curriculum changes present opportunities for Indigenous culture to be expressed through teaching and learning experiences but only if teachers have the necessary cultural capital (Evans et al., Citation2017). Teachers who have not yet developed cultural awareness, inadvertently promote marginalisation (Aronson & Laughter, Citation2016), and incorporate pedagogical strategies within their teaching which actively promote epistemologies deeply embedded in white settler colonial discourses (Bascuñán et al., Citation2022). As a result, a distinct lack of cultural awareness inhibits teachers’ understanding and motivation to cater for the needs of diverse learners when implementing TIGaS within curriculum. Developing teacher cultural capital needs to be a priority for all educational stakeholders because allowing teachers to engage in meaningful discussions develops their cultural awareness and alleviates concerns within classrooms to provide greater learning outcomes for all students (Baynes, Citation2016).

Discussion

The focus on these enablers and constraints provides insight into the complexities of enacting TIGaS within curriculum to support policy and framework objectives such as the UNDRIP. This research aligns with the UNDRIP principles to promote the advancement of educational outcomes for Indigenous students. It was identified that the role that teachers play at a personal cultural capital level, has a significant impact upon facilitation of TIGaS within curriculum. This was evident with all dominant enablers and constraints identified at a micro level (universities, schools and classrooms). For example, McLaughlin et al. (Citation2014) suggest within their paper, which explores the embedding of Indigenous knowledges and perspectives for future curriculum leaders, that pre-service teachers need to be given the support and opportunity to develop cultural capital to develop into effective teachers. Furthermore, Papp (Citation2016) in her paper exploring teaching strategies to improve educational outcomes for Indigenous students, suggests that school leadership plays an integral role in underpinning improved outcomes for Indigenous students. This suggests that at the core of embedding TIGaS within curriculum, responsibility lies with teachers, teaching staff and senior leadership. A key feature reported found culturally relevant pedagogy to be the dominant enabler which suggests that teachers who engage and understand CRP conceptual frameworks, are more likely to provide culturally appropriate teaching and learning experiences for students (Brown-Jeffy & Cooper, Citation2011). However, TCA, which is integral to CRP, is a major constraint.

Warren (Citation2018) suggests CRP and TCA are the same phenomenon, the difference lies in whether it is viewed from a deficit perspective. Educators who enact CRP can provide more effective teaching and learning experiences for students. Likewise, educators who lack cultural awareness may not be able to identify cultural gaps in curriculum and are not effective in identifying where TIGaS should be positioned within curriculum. This tension is further exacerbated (Booth & Allen, Citation2017), by the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL), standards ‘1.4 Strategies for teaching Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students’ and ‘2.4 Understand and respect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to promote reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians’ (AITSL, Citation2017). These standards imply all teachers should have a pre-requisite level of cultural awareness to facilitate effective implementation of the standards although, the constraint suggests otherwise. Since initial teacher education is accredited by its compliance with AITSL standards, a flaw or deficit in understanding how to implement the standards may potentially perpetuate a lack of understanding of CRP approaches. For example, McLaughlin et al. (Citation2014) stated that pre-service teachers who undertook a 4-year Bachelor of Education, were not adequately prepared to embed Indigenous knowledges and perspectives. Additionally, Hickling-Hudson and Ahlquist (Citation2003), suggest to effectively prepare teachers to embed Indigenous knowledges and perspectives authentically, they must be provided with a teacher education program which facilitates alternative epistemologies and varying pedagogical approaches.

A potential limitation of this study was that although study quality was assessed using a quality assessment tool used for qualitative studies developed by Long and Godfrey (Citation2004) and Ryan et al. (Citation2007), the study did not assess the quality of the journals from which those papers were published. Additionally, the date ranges from which the literature was investigated (2002–2022), may be a further potential limitation of this study.

Conclusion

How ‘enablers and constraints’ impact the enactment of Traditional Indigenous Games (and Sports) within HPE curriculum will play a role in shaping the future of Indigenous education. In addressing how enablers and constraints are currently positioned within curriculum, including the tensions and complexities of the crossover between enablers and constraints, future investigation is needed to identify how educational stakeholders and policymakers consider changes at both micro and macro levels to improve educational outcomes for Indigenous students. The recent focus on embedding Indigenous knowledges and perspectives within curriculum, must continue to be a priority for educational stakeholders. Future generations of Indigenous students must have their cultural identity respected through a supportive HPE curriculum.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Graeme Bonato

Graeme Bonato ∼ Lecturer (Education) Graeme began his educational career as a secondary Health and Physical Education and History teacher before commencing sessional employment with James Cook University leading to doctoral studies and his current appointment within the college of Arts, Society and Education. Graeme’s research focuses on embedding Indigenous knowledges and perspectives within curriculum.

Maree Dinan-Thompson

Maree Dinan-Thompson ∼ Deputy Vice Chancellor, Education. Over a period of more than 20 years at James Cook University Maree has made an outstanding contribution to the delivery of innovative, contemporary, and authentic curriculum, assessment and course design which has drawn both her students and colleagues into a heightened level of engagement and transformation in teaching and learning.

Maree’s curriculum expertise forms a strong part of her research focus on health and physical education curriculum, curriculum change and assessment literacy. In more recent times Maree has engaged in research on Indigenous games and their cultural significance to stakeholders.

Maree’s learning and teaching expertise has led to senior management roles at James Cook University. From 2017 to 2020 Maree undertook the Dean, Learning, Teaching and Student Engagement, and followed to the DVC Students role in 2020. Maree’s research interests on curriculum, assessment, student success, and health promotion provide foundation to valuing students, valuing educators and enabling capability building.

Peta Salter

Peta Salter ∼ Senior Lecturer (Curriculum and Pedagogy). Dr Peta Salter, began her educational career as a secondary History and English teacher before commencing sessional employment with James Cook University, leading to doctoral studies and her current appointment in Education.

Peta’s teaching has focused on work-integrated learning approaches to enriching pre-service teachers’ efficacy and understandings of the contexts and communities in which they teach to support and develop ‘classroom-readiness’. Peta’s research examines the epistemological and ontological assumptions in intercultural policy in Australian education and their impacts on curriculum and pedagogy enacted by ‘classroom-ready’ teachers. Recent projects include supporting cultural sustainability and embedding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges in teacher education, and service-learning curriculum and pedagogy design with a focus on critical global citizenship and student agency.

Notes

1 The term ‘Indigenous’ is used as a collective term to refer to all Indigenous cultural groups examined within the literature including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The author acknowledges the diversity of people, encompassed in this term.

References

- Akena, F. A. (2012). Critical analysis of the production of Western knowledge and its implications for Indigenous knowledge and decolonization. Journal of Black Studies, 43(6), 599–619. doi:10.1177/0021934712440448

- Allen, A., Hancock, S. D., Starker-Glass, T., & Lewis, C. W. (2017). Mapping culturally relevant pedagogy into teacher education programs: A critical framework. Teachers College Record, 119(1), 1–26. doi:10.1177/016146811711900107

- Aronson, B., & Laughter, J. (2016). The theory and practice of culturally relevant education: A synthesis of research across content areas. Review of Educational Research, 86(1), 163–206. doi:10.3102/0034654315582066

- Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2016). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures. https://www.acara.edu.au/curriculum/foundation-year-10/cross-curriculum-priorities/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islanderhistories-and-cultures-ccp

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. (2017). Australian institute for teaching and school leadership. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/teach/standards

- Aypay, A. (2016). Investigating the role of traditional children’s games in teaching ten universal values in Turkey. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 16(62). doi:10.14689/ejer.2016.62.14

- Barker, D. (2019). In defence of white privilege: Physical education teachers’ understandings of their work in culturally diverse schools. Sport, Education and Society, 24(2), 134–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2017.1344123

- Bascuñán, D., Carroll, S. M., Sinke, M., & Restoule, J.-P. (2022). Teaching as trespass: Avoiding places of innocence. Equity & Excellence in Education, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2021.1993112

- Baynes, R. (2016). Teachers’ attitudes to including indigenous knowledges in the Australian science curriculum. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 45(1), 80–90. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2015.29

- Bergeron, B. S. (2008). Enacting a culturally responsive curriculum in a novice teacher’s classroom: Encountering disequilibrium. Urban Education, 43(1), 4–28. doi:10.1177/0042085907309208

- Biermann, S., & Townsend-Cross, M. (2008). Indigenous pedagogy as a force for change. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 37(S1), 146–154. doi:10.1375/S132601110000048X

- Bishop, M. (2021). A rationale for the urgency of Indigenous education sovereignty: Enough’s enough. The Australian Educational Researcher, 48(3), 419–432. doi:10.1007/s13384-020-00404-w

- Bishop, M., Vass, G., & Thompson, K. (2021). Decolonising schooling practices through relationality and reciprocity: embedding local Aboriginal perspectives in the classroom. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 29(2), 193–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2019.1704844

- Bodkin-Andrews, G., & Carlson, B. (2016). The legacy of racism and Indigenous Australian identity within education. Race Ethnicity and Education, 19(4), 784–807. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2014.969224

- Boon, H. J., & Lewthwaite, B. (2015). Development of an instrument to measure a facet of quality teaching: Culturally responsive pedagogy. International Journal of Educational Research, 72, 38–58. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2015.05.002

- Booth, S. R., & Allen, W. J. (2017). More than the curriculum: Teaching for reconciliation in Western Australia.

- Brown, M. R. (2007). Educating all students: Creating culturally responsive teachers, classrooms, and schools. Intervention in School and Clinic, 43(1), 57–62. doi:10.1177/10534512070430010801

- Brown-Jeffy, S., & Cooper, J. E. (2011). Toward a conceptual framework of culturally relevant pedagogy: An overview of the conceptual and theoretical literature. Teacher Education Quarterly, 38(1), 65–84.

- Burgess, C., Thorpe, K., Egan, S., & Harwood, V. (2022). Learning from Country to conceptualise what an Aboriginal curriculum narrative might look like in education. Curriculum Perspectives, 42(2), 157–169. doi:10.1007/s41297-022-00164-w

- Burnett, C. (2006). Indigenous games of South African children: A rationale for categorization and taxonomy. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation, 28(2), 1–13. doi:10.4314/sajrs.v28i2.25939

- Buxton, L. M. (2020). Professional development for teachers meeting cross-cultural challenges. Journal for Multicultural Education, 14(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/JME-06-2019-0050

- Craven, R. G., Yeung, A. S., & Han, F. (2014). The impact of professional development and indigenous education officers on Australian teachers’ indigenous teaching and learning. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 39(8), 85–108. doi:10.14221/ajte.2014v39n8.6

- De Plevitz, L. (2007). Systemic racism: The hidden barrier to educational success for Indigenous school students. Australian Journal of Education, 51(1), 54–71. doi:10.1177/000494410705100105

- Dinan Thompson, M., Meldrum, K., & Sellwood, J. (2014). “ … it is not just a game”: Connecting with culture through traditional indigenous games. American Journal of Educational Research, 2(11), 1015–1022. https://doi.org/10.12691/EDUCATION-2-11-3

- Dudgeon, P., Wright, M., Paradies, Y., Garvey, D., & Walker, I. (2010). The social, cultural and historical context of aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. In N. Purdue, P. Dudgeon, & R. Walker (Eds.), Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice (pp. 25–42). Commonwealth of Australia.

- Edwards, K. (2008). Yulunga: Traditional Indigenous Games. Australian Sports Commission.

- Edwards, K. (2009). Traditional games of a timeless land: Play cultures in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Australian Aboriginal Studies, (2), 32–43.

- Evans, J., Georgakis, S., & Wilson, R. (2017). Indigenous games and sports in the Australian national curriculum: Educational benefits and opportunities? Ab-original: Journal of Indigenous Studies and First Nations and First Peoples’ Cultures, 1(2), 195–213. https://doi.org/10.5325/aboriginal.1.2.0195

- Gay, G. (2002). Preparing for culturally responsive teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(2), 106–116. doi:10.1177/0022487102053002003

- Gray, J., & Beresford, Q. (2008). A ‘formidable challenge’: Australia’s quest for equity in Indigenous education. Australian Journal of Education, 52(2), 197–223. doi:10.1177/000494410805200207

- Hansen, K. (2014). The importance of ethnic cultural competency in physical education. Strategies, 27(3), 12–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/08924562.2014.900462

- Hart, V., Whatman, S., McLaughlin, J., & Sharma-Brymer, V. (2012). Pre-service teachers’ pedagogical relationships and experiences of embedding Indigenous Australian knowledge in teaching practicum. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 42(5), 703–723. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2012.706480

- Hickling-Hudson, A., & Ahlquist, R. (2003). Contesting the curriculum in the schooling of Indigenous children in Australia and the United States: From Eurocentrism to culturally powerful pedagogies. Comparative Education Review, 47(1), 64–89. doi:10.1086/345837

- Hradsky, D. (2022). Education for reconciliation? Understanding and acknowledging the history of teaching First Nations content in Victoria, Australia. History of Education, 51(1), 135–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/0046760X.2021.1942238

- Johnson, B., Down, B., Le Cornu, R., Peters, J., Sullivan, A., Pearce, J., & Hunter, J. (2015). Promoting early career teacher resilience: A socio-cultural and critical guide to action. Routledge.

- Kanu, Y. (2007). Increasing school success among Aboriginal students: Culturally responsive curriculum or macrostructural variables affecting schooling? Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 1(1), 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/15595690709336599

- Kiran, A., & Knights, J. (2010). Traditional Indigenous Games promoting physical activity and cultural connectedness in primary schools? Cluster Randomised Control Trial. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 21(2), 149–151. doi:10.1071/HE10149

- Kitchen, J., Hodson, J., & Cherubini, L. (2011). Developing capacity in indigenous education: Attending to the voices of Aboriginal teachers. Action in Teacher Education, 33(5–6), 615–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/01626620.2011.627308

- Klenowski, V. (2009). Australian Indigenous students: Addressing equity issues in assessment. Teaching Education, 20(1), 77–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210802681741

- Kukutai, T., & Taylor, J. (2016). Data sovereignty for indigenous peoples: Current practice and future needs. In Indigenous data sovereignty: Toward an agenda (Vol. 38). ANU Press. https://doi.org/10.22459/CAEPR38.11.2016

- Legge, M. (2011). Te ao kori as expressive movement in Aotearoa New Zealand physical education teacher education (PETE): A narrative account. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 2(3–4), 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/18377122.2011.9730361

- Legge, M. (2015). Case study, poetic transcription and learning to teach indigenous movement in physical education. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 6(2), 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/18377122.2015.1051266

- Lewthwaite, B., Owen, T., Doiron, A., Renaud, R., & McMillan, B. (2014). Culturally responsive teaching in Yukon First Nation settings: What does it look like and what is its influence? Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy (155).

- Linds, W., Hyslop, M., Goulet, L., & Eduardo Jasso Juárez, V. (2018). Weechi metuwe mitotan: Playing games of presence with Indigenous youth in Saskatchewan, Canada. International Journal of Play, 7(1), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2018.1437340

- Long, A. F., & Godfrey, M. (2004). An evaluation tool to assess the quality of qualitative research studies. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 7(2), 181–196. http://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000045302

- Louth, S., & Jamieson-Proctor, R. (2014). Empowering teachers to embed Indigenous perspectives: A study of the effects of professional development in Traditional Indigenous Games. Proceedings of the Australian Teacher Education Association Annual Conference (ATEA 2014).

- Lowe, K., Skrebneva, I., Burgess, C., Harrison, N., & Vass, G. (2021). Towards an Australian model of culturally nourishing schooling. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 53(4), 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2020.1764111

- Lowe, K., & Yunkaporta, T. (2013). The inclusion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander content in the Australian National Curriculum: A cultural, cognitive and socio-political evaluation. Curriculum Perspectives, 33(1), 1–14.

- Lyoka, P. A. (2007). Questioning the role of children’s indigenous games of Africa on development of fundamental movement skills: A preliminary review. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 15(3), 343–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930701679312

- Macdonald, D., Enright, E., & McCuaig, L. (2018). Re-visioning the Australian curriculum for health and physical education. In H. A. Lawson (Ed.), Redesigning Physical Education: An equity agenda in which every child matters (pp. 196–209). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429466991-13

- Madondo, F., & Tsikira, J. (2021). Traditional children’s games: Their relevance on skills development among rural Zimbabwean children Age 3–8 years. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2021.1982084

- Martin, G., Nakata, V., Nakata, M., & Day, A. (2017). Promoting the persistence of Indigenous students through teaching at the Cultural Interface. Studies in Higher Education, 42(7), 1158–1173. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1083001

- Maxwell, J., Lowe, K., & Salter, P. (2018). The re-creation and resolution of the ‘problem’ of Indigenous education in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cross-curriculum priority. Australian Educational Researcher, 45(2), 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-017-0254-7

- McLaughlin, J., & Whatman, S. (2016). Seeking affirmation via Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community knowledge: Transforming Australian school curricula. Proceedings of the 2016 American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting.

- McLaughlin, J., Whatman, S., & Nielsen, C. (2014). Supporting future curriculum leaders in embedding Indigenous knowledge on teaching practicum: Final Report 2014.

- McLaughlin, J. M., & Whatman, S. L. (2015). Beyond social justice agendas: Indigenous knowledges in preservice teacher education and practice in Australia. International Perspectives on race (and racism): Historical and contemporary considerations in education and society, 101–120.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Group, P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

- Moodie, N., & Patrick, R. (2017). Settler grammars and the Australian professional standards for teachers. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 45(5), 439–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2017.1331202

- Morrison, A., Morrison, A., Rigney, L.-I., Hattam, R., & Diplock, A. (2019). Toward an Australian culturally responsive pedagogy: A narrative review of the literature. University of South Australia Adelaide.

- Nakata, M. (2002). Indigenous knowledge and the cultural interface: Underlying issues at the intersection of knowledge and information systems. International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions Journal, 28(5–6), 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/034003520202800513

- Nakata, M. (2010). The cultural interface of islander and scientific knowledge (Vol. 39). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.473613845054948

- Nakata, M. (2011). Pathways for indigenous education in the Australian curriculum framework (Vol. 40). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.609902657428412

- Neeganagwedgin, E. (2013). A critical review of Aboriginal education in Canada: Eurocentric dominance impact and everyday denial. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 17(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2011.580461

- Nxumalo, S. A., & Mncube, D. W. (2018). Using indigenous games and knowledge to decolonise the school curriculum: Ubuntu perspectives. Perspectives in Education, 36(2), 103–118. https://doi.org/10.18820/2519593X/pie.v36i2.5

- Papp, T. (2016). Teacher strategies to improve education outcomes for Indigenous students. Comparative and International Education, 45(3). doi:10.5206/cie-eci.v45i3.9302

- Papp, T. A. (2020). A Canadian study of coming full circle to traditional Aboriginal pedagogy: A pedagogy for the 21st century. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 14(1), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/15595692.2019.1652587

- Parker, E., Meiklejohn, B., Patterson, C., Edwards, K., Preece, C., Shuter, P., & Gould, T. (2006). Our games our health: A cultural asset for promoting health in Indigenous communities. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 17(2), 103–108. doi:10.1071/HE06103

- Pereira, A. S. M., & Venâncio, L. (2021). African and Indigenous games and activities: A pilot study on their legitimacy and complexity in Brazilian physical education teaching. Sport, Education and Society, 26(7), 718–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2021.1902298

- Pill, S., Evans, J. R., Williams, J., Davies, M. J., & Kirk, M.-A. (2021). Conceptualising games and sport teaching in physical education as a culturally responsive curriculum and pedagogy. Sport, Education and Society, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2021.1964461

- Premier, J. A., & Miller, J. (2010). Preparing pre-service teachers for multicultural classrooms. Australian Journal of Teacher Education (Online), 35(2), 35–48. http://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2010v35n2.3

- Preston, J. P. (2016). Education for Aboriginal peoples in Canada: An overview of four realms of success. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 10(1), 14–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/15595692.2015.1084917

- Quijada Cerecer, P. D. (2013). Independence, dominance, and power: (Re)examining the impact of school policies on the academic development of indigenous youth. Theory Into Practice, 52(3), 196–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2013.804313

- Rahman, K. (2010). Addressing the foundations for improved Indigenous secondary student outcomes: A South Australian qualitative study. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 39(1), 65–76. doi:10.1375/S1326011100000922

- Rahman, K. (2013). Belonging and learning to belong in school: The implications of the hidden curriculum for indigenous students. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 34(5), 660–672. doi:10.1080/01596306.2013.728362

- Rata, E. (2012). Theoretical claims and empirical evidence in Maori education discourse. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 44(10), 1060–1072. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2011.00755.x

- Rogers, J. (2018). Teaching the teachers: Re-educating Australian teachers in Indigenous education. In P. Whitinui, M. del Carmen Rodríguez de France, & O. McIvor (Eds.), Promising practices in Indigenous teacher education (pp. 27–39). Springer, Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6400-5_3

- Rosnon, M. R., Talib, M. A., & Wan Abdul Rahman, N. A. F. (2019). Self-determination of indigenous education policies in Australia: The case of the Aboriginal people and Torres Strait islander people. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, 27.

- Ryan, F., Coughlan, M., & Cronin, P. (2007). Step-by-step guide to critiquing research. Part 2: qualitative research. British Journal of Nursing, 16(12), 738–744. http://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2007.16.12.23726

- Salter, P., & Maxwell, J. (2016). The inherent vulnerability of the Australian Curriculum’s cross-curriculum priorities. Critical Studies in Education, 57(3), 296–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2015.1070363

- Salter, P., & Maxwell, J. (2018). Navigating the ‘inter’ in intercultural education. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 39(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2016.1179171

- Santoro, N., & Kennedy, A. (2016). How is cultural diversity positioned in teacher professional standards? An international analysis. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 44(3), 208–223. doi:10.1080/1359866X.2015.1081674

- Sarraj, H., Bene, K., Li, J., & Burley, H. (2015). Raising cultural awareness of fifth-grade students through multicultural education: An action research study. Multicultural Education, 22(2), 39–45.

- Sato, T., Fisette, J., & Walton, T. (2013). The experiences of African American physical education teacher candidates at secondary urban schools. The Urban Review, 45(5), 611–631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-013-0238-5

- Savage, C., Hindle, R., Meyer, L. H., Hynds, A., Penetito, W., & Sleeter, C. E. (2011). Culturally responsive pedagogies in the classroom: Indigenous student experiences across the curriculum. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 39(3), 183–198. doi:10.1080/1359866X.2011.588311

- Schmidlein, R., Vickers, B., & Chepyator-Thomson, R. (2014). Curricular issues in urban high school physical education. Physical Educator, 71(2), 273–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2017.1271266.

- Shehu, J. (2004). Sport for all in postcolony: Is there a place for indigenous games in physical education curriculum and research in Africa. Africa Education Review, 1(1), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146620408566267

- Sisson, J. H., Whitington, V., & Shin, A.-M. (2020). Teaching culture through culture: A case study of culturally responsive pedagogies in an Australian early childhood/primary context. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 34(1), 108–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2019.1692110

- Sleeter, C. E. (2011). An agenda to strengthen culturally responsive pedagogy. English teaching: Practice and critique, 10(2), 7–23.

- Sumida Huaman, E., & Valdiviezo, L. A. (2014). Indigenous knowledge and education from the Quechua community to school: Beyond the formal/non-formal dichotomy. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 27(1), 65–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2012.737041

- Turner, J. D. (2007). Beyond cultural awareness: Prospective teachers’ visions of culturally responsive literacy teaching. Action in Teacher Education, 29(3), 12–24. doi:10.1080/01626620.2007.10463456

- United Nations (General Assembly). (2007). Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People.

- Vass, G. (2012). So, what is wrong with Indigenous education? Perspective, position and power beyond a deficit discourse. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 41(2), 85–96. doi:10.1017/jie.2012.25

- Vass, G. (2014). The racialised educational landscape in Australia: Listening to the whispering elephant. Race Ethnicity and Education, 17(2), 176–201. doi:10.1080/13613324.2012.674505

- Vass, G. (2017). Preparing for culturally responsive schooling: Initial teacher educators into the fray. Journal of Teacher Education, 68(5), 451–462. doi:10.1177/0022487117702578

- Vass, G., & Hogarth, M. (2022). Can we keep up with the aspirations of Indigenous education?. Critical Studies in Education, 63(1), 1–14. http://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2022.2031617

- Veintie, T. (2013). Practical learning and epistemological border crossings: Drawing on indigenous knowledge in terms of educational practices. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 7(4), 243–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/15595692.2013.827115

- Veintie, T., & Holm, G. (2010). The perceptions of knowledge and learning of Amazonian indigenous teacher education students. Ethnography and Education, 5(3), 325–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457823.2010.511443

- Villegas, A. M., & Lucas, T. (2002). Preparing culturally responsive teachers: Rethinking the curriculum. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(1), 20–32. doi:10.1177/0022487102053001003

- Walton-Fisette, J. L., Philpot, R., Phillips, S., Flory, S. B., Hill, J., Sutherland, S., & Flemons, M. (2018). Implicit and explicit pedagogical practices related to sociocultural issues and social justice in physical education teacher education programs. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 23(5), 497–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2018.1470612

- Walton-Fisette, J. L., Richards, K. A. R., Centeio, E. E., Pennington, T. R., & Hopper, T. (2019). Exploring future research in physical education: Espousing a social justice perspective. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 90(4), 440–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2019.1615606

- Wane, N. N. (2008). Mapping the field of Indigenous knowledges in anti-colonial discourse: A transformative journey in education. Race Ethnicity and Education, 11(2), 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613320600807667

- Warren, C. A. (2018). Empathy, teacher dispositions, and preparation for culturally responsive pedagogy. Journal of Teacher Education, 69(2), 169–183. http://doi.org/10.1177/0022487117712487

- Watkins, M., Lean, G., & Noble, G. (2016). Multicultural education: The state of play from an Australian perspective. Race Ethnicity and Education, 19(1), 46–66. doi:10.1080/13613324.2015.1013929

- Weuffen, S. L., Cahir, F., & Pickford, A. M. (2017). The centrality of Aboriginal cultural workshops and experiential learning in a pre-service teacher education course: A regional Victorian University case study. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(4), 838–851. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1242557

- Whatman, S., & Meston, T. (2016). Embedding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges in the AC: HPE-considering purposes of Indigenous games. Active & Healthy, 23(4), 36–39.

- Whatman, S., Quennerstedt, M., & McLaughlin, J. (2017). Indigenous knowledges as a way to disrupt norms in physical education teacher education. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 8(2), 115–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/18377122.2017.1315950

- Whatman, S. L., & Singh, P. (2015). Constructing health and physical education curriculum for indigenous girls in a remote Australian community. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 20(2), 215–230. doi:10.1080/17408989.2013.868874

- Williams, J. (2014). Introducing Torres Strait Island dance to the Australian high school physical education curriculum. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 34(3), 305–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2013.823380

- Williams, J. (2016). Invented tradition and how physical education curricula in the Australian Capital Territory has resisted Indigenous mention. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 7(3), 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/18377122.2016.1233803

- Williams, J. (2017). Embedding Indigenous content in Australian physical education-perceived obstacles by health and physical education teachers. Mystery Train, 2007.

- Williams, J. (2018). I didn’t even know that there was such a thing as Aboriginal games: A figurational account of how Indigenous students experience physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 23(5), 462–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2016.1210118

- Williams, J., & Pill, S. (2019). Using a game sense approach to teach Buroinjin as an Aboriginal game to address social justice in physical education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 39(2), 176–185. doi:10.1123/jtpe.2018-0154

- Williamson, J., & Dalal, P. (2007). Indigenising the curriculum or negotiating the tensions at the cultural interface? Embedding indigenous perspectives and pedagogies in a university curriculum (Vol. 36). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.909332930681170

- Wrench, A., & Garrett, R. (2021a). Culturally responsive pedagogy in health and physical education. In J. Stirrup & O. Hooper (Eds.), Critical pedagogies in physical education, physical activity and health (1st ed., pp. 196–209). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003003991

- Wrench, A., & Garrett, R. (2021b). Navigating culturally responsive pedagogy through an Indigenous games unit. Sport, Education and Society, 26(6), 567–578. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2020.1764520

- Yunkaporta, T., & McGinty, S. (2009). Reclaiming Aboriginal knowledge at the cultural interface. The Australian Educational Researcher, 36(2), 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03216899