ABSTRACT

The UNESCO Biosphere Reserve concept has been one of the first conservation approaches to adopt an integrated conservation perspective (‘nature and people’), rather than focus on nature conservation exclusively. Biosphere Reserves designated before 1995 were mandated to shift their focus adequately. Pre-1995 Biosphere Reserves provide unique case studies to examine how a conceptual shift in conservation can be implemented in practice. I focus on three areas in (West) Germany (Bayerischer Wald, Berchtesgadener Land, Niedersächsisches Wattenmeer) that underwent this shift to explore implementation challenges and resulting outcomes. I find that political and administrative decision-makers reacted differently: one area withdrew, one extended its area, and one is still working on an implementation of the shift. Top-down processes of designation and objective setting, the overlaps between other conservation designations and the Biosphere Reserves, and the exclusion of local people have created challenges for the legitimacy of the Biosphere Reserves because they miss broader societal support. Clear objectives and distinctions to other conservation schemes, adequate human and financial resources, and political (local) support are important aspects to implement a conceptual shift. Researchers can support the implementation by allocating space in their theories and concepts for the integration of different knowledge types and context-specific adaptions.

EDITED BY:

Shifting conservation

Mace (Citation2014) labels the current phase of conservation science ‘nature and people’. It acknowledges the interlinkages between humans and ecosystems and the importance of cultures and institutions (Linnell et al. Citation2015). The recent renaming of this journal to Ecosystems and People can be seen as part of the development to welcome a more integrated perspective on conservation (van Oudenhoven et al. Citation2018; Martín-López et al. Citation2019). Hand-in-hand comes often an endorsement of a governance shift: from a top-down, prohibitive approach with governments as main actors and decision-makers to more multi-level, polycentric and participatory approaches with multiple stakeholders involved in the decision-making and execution (Lockwood Citation2010; Eagles et al. Citation2013; Tengö et al. Citation2014). In such governance approaches, success criteria are both ecological (e.g. status of biodiversity, water quality) and social criteria (e.g. legitimacy, responsibility, costs and benefits) (Bennett Citation2016).

Today, little research has explored how the shift in conservation from ‘nature for itself’ to ‘nature and people’ and from top-down to participatory governance is implemented on the ground within existing structures. This would be important because many existing protected areas were set up to prioritize nature conservation, not considering how the areas can or should contribute to human well-being. These areas need to shift their focus, objectives, and approaches within the present, local context of formal and informal institutions and existing relationships, experiences, and perspectives.

The UNESCO Biosphere Reserve (BR) concept was one of the first international conservation approaches that shifted its conceptual focus. With the Sevilla Strategy from 1995, the UNESCO outlined the conceptual shift from nature conservation exclusively to an integrated approach with the aim to create ‘more than just protected areas’ (UNESCO Citation1996, p. 5). Before 1995, the objective of the UNESCO BRs was to establish a global network of protected areas focusing on nature conservation (Ishwaran et al. Citation2008). Their governance was top-down and often half-hearted. BRs were commonly superimposed on existing protected areas or research sites (Price et al. Citation2010; Reed and Massie Citation2013; Bridgewater Citation2016; Tanaka and Wakamatsu Citation2018) with the result that the BR title was frequently an add-on without effects on the wider landscape or the management (Schliep and Stoll-Kleemann Citation2010; Coetzer et al. Citation2014).

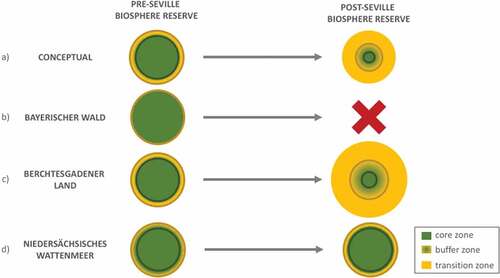

Since 1995, the conceptual idea of BRs is to acknowledge and foster the interlinkages between humans and ecosystems (Stoll-Kleemann and Welp Citation2008). Nowadays, BRs should have three zones (core, buffer, and transition zone) with the majority of the BR dedicated to the sustainable development of people and nature in the transition zone (); Ishwaran et al. Citation2008). The UNESCO has defined three objectives for BRs: (1) conservation of cultural and biological diversity, (2) sustainable development, and (3) logistic support facilitating projects, education, training, research, and monitoring (UNESCO Citation1996, Citation2017a). BRs should achieve these objectives through participatory governance that includes stakeholders. After 1995, about 320 BRs which had been designated before, had to implement this conceptual shift (Price et al. Citation2010; Reed and Massie Citation2013). As such, pre-1995 BRs can serve as case studies to explore how conceptual shifts affect on the ground management and governance in conservation.

Figure 1. Changes in the focus of Biosphere Reserves before and after 1995. (a) Conceptual shift from nature protection with a dominant core zone to sustainable development with a dominant transition zone. (b) Bayerischer Wald with a focus on the core zone is no longer a BR. (c) Berchtesgadener Land which had a marginal transition zone before 1995 which got extended. (d) Niedersächsisches Wattenmeer which major part was and is the core zone with a marginal buffer zone and no considerable transition zone.

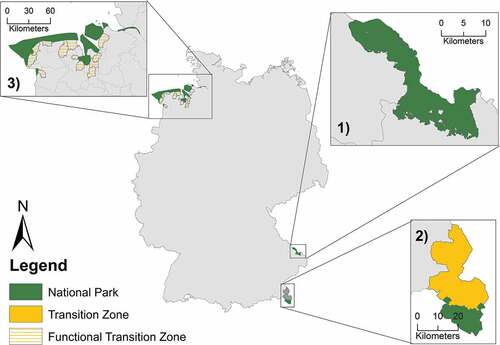

In this perspective paper, I examine how three (West) German BRs implemented the 1995 conceptual shift in practice, and I reflect on governance challenges that still persist in pre-1995 BRs more than 20 years later. The three areas are typical pre-1995 BRs because they had already been National Parks before the BR title was conferred, resulting in double designations of the areas (Erdmann et al. Citation1995). The ways and speeds of reaction were different in the three areas, which helps to uncover different dimensions affecting change.

Case studies

The Bayerischer Wald (Bavarian Forest) is located along the Czech-German border () and hosts Germany’s oldest National Park founded in 1970 (BfN Citation2016). In 1981, the same area was designated as the first BR in former West Germany. More than 75% of the BR area was the core zone and no transition zone was designated (Erdmann et al. Citation1995). The National Park administration was also responsible for the BR. In 1997, the National Park was extended to its current extent of 24,000 ha (Nationalpark Bayerischer Wald Citation2010). Large parts of the local population opposed the enlargement because they were concerned about the increased amount of bark beetles and their effect on the forestry around the National Park. After the conceptual shift of the BR concept in 1995, the BR would have needed a transition zone. In 2007, the BR Bayerischer Wald withdrew and is nowadays solely a National Park (, Price et al. Citation2010, UNESCO Citation2017b).

Figure 2. Map of Germany with the three areas: (a) Bayerischer Wald: National Park since 1970 and BR between 1981–2007; (b) Berchtesgadener Land: National Park since 1978 and BR since 1990; (c) Niedersächsisches Wattenmeer: National Park since 1986, biosphere reserve since 1992, and World Heritage Site since 2009.

The Berchtesgadener Land is located in the German Alps (). In 1978, an area of more than 20,000 ha was designated as a National Park (BfN Citation2016). In 1990, the BR title was conferred to the area of the National Park plus a similar big area attached to the north (Erdmann et al. Citation1995). Since then, the National Park has been the core and some of the buffer zone of the BR. As a reaction to the conceptual shift in 1995, the transition zone was extended and the BR renamed into Berchtesgadener Land in 2010 (). Nowadays, the BR area covers the whole county Berchtesgadener Land and is four times larger than the National Park and more than 70% of the BR is designated as the transition zone (BfN, Citation2016, Citation2017). The BR and the National Park have always had separate administrations.

The BR Niedersächsisches Wattenmeer (Wadden Sea of Lower Saxony) is located at the German North Sea coast (). It was designated as a National Park in 1986 and as a BR in 1992 (BfN Citation2017, Citation2016). In 2009, the UNESCO additionally conferred the title of UNESCO World Heritage to the trilateral Wadden Sea which includes the Niedersächsisches Wattenmeer (UNESCO Citationn.d.). The BR administration is part of the National Park administration which is a state-level administration. The BR is almost coherent with the National Park which covers mainly area on the seaside. Less than 1% of the 240,000 ha area is classified as the transition zone (BfN Citation2017).

Methodological approach

I conducted explorative, semi-structured interviews (Bryman Citation2016) with one purposively chosen key informant within each of the four administrations: National Park Bayerischer Wald, National Park Berchtesgaden, BR Berchtesgadener Land, and National Park and BR Niedersächsisches Wattenmeer. The general lack of scientific literature on the consequences of the shift of the BR concept in general and in the three BRs, in particular, made an explorative methodological approach necessary. Interviewees were either the head of the administration or of a department within the administration and were nominated by the administration to be the most competent interviewee on the topic. The specificity of the topic and the fact that only a few people were or are aware and working with the BR in the three areas limited the number of potential interviewees.

The interviews targeted the development of my perspectives regarding the implementation of the conceptual shift in each area. Below I outline reflections on each area specifically and then discuss some of the observed generalizations across the cases and BRs more broadly. I present the three case studies along three categories for governance in the context of conservation: (1) process, (2) structure, and (3) legitimacy (Bennett Citation2016). I reference interviewees’ direct quotes with acronyms using BW for the National Park Bayerischer Wald, NPBG for the National Park Berchtesgaden, BRBL for the BR Berchtesgadener Land, and NW for the BR Niedersächsisches Wattenmeer.

Results

Bayerischer Wald

Process – top-down and without drive

Ecological research within the National Park Bayerischer Wald was the main reason to receive the BR title in the 1980s. In the following years, the BR was ‘unanimated’ (I_BW) and only the research in the National Park ‘kept [it] above water’ (I_BW). In the 2000s, the German MAB-Committee pushed that either ‘we [National Park administration] bury the whole or we move a step further’ (I_BW). Neither state or county politicians nor the National Park administration were eager to keep the BR title and withdrew in 2007.

Structure – National Park overshadows Biosphere Reserve

From the beginning of the BR, the National Park was valued and promoted more within and also outside the area. One person partly worked on the administration of the BR in the unit for regional development within the department for regional development and education in the National Park administration.

Nowadays, the National Park concentrates on nature conservation and has picked single topics related to sustainability, e.g. sustainable transportation which is ‘typical for biosphere reserves’ (I_BW). Local municipalities collaborate to strengthen their touristic offer and capitalize on the National Park. However, all of this has not stirred a regional strategy for sustainable development.

Legitimacy – when nobody knows

The discussion about the BR and the decision to withdraw happened on the local administrative and political level. Other stakeholders were not involved: ‘the citizens did basically not know that a biosphere reserve existed or that there was a discussion’ (I_BW). Prior processes connected with nature conservation (e.g. enlargement of the National Park) had caused a negative attitude in the general public towards conservation designations. Public discussions ‘always’ (I_BW) had a negative connotation concerning protected areas with the effect that ‘in the region, an almost total sullenness existed regarding protected areas’ (I_BW). For this reason, local administrative and political decision-makers did not want a public debate.

Berchtesgadener Land

Process – a long, winding way

In the Berchtesgadener Land, the BR title was ‘imposed without any involvement of citizens’ (I_BRBL) and ‘suddenly, it was said ‘you are a Biosphere Reserve now’‘ (I_NPBG). ‘Then relatively little happened’ (I_NPBG). In the 2000s, the German MAB-Committee demanded more activities within the BR. Politicians at the county level, especially the county administrator, wanted to keep the BR title. They reacted and extended the transition zone to its present extent of the whole county. In fall 2013, a new director of the BR started with the aim ‘to search and find ways together’ (I_BRBL) with the county administration, the National Park administration, but also other organizations at the county level.

Structure – separation of administrations and tasks

The BR and the National Park have two separate administrations located in different towns in the county. The two administrations meet from time to time, but there is ‘no institutionalized collaboration’ (I_NPBG). The National Park administration belongs to the state ministry for environment. The BR administration is part of the district government but is located in the building of the county administration. ‘This makes sense in any case. The short ways in the building are super’ (I_BRBL) because the BR concurs with the county.

Tasks and responsibilities are clearly distributed between the BR and National Park administrations. Both administrations cover ‘research, outreach, and education’ (I_BRBL) with own activities. The ‘highest priority is nature conservation’ (I_NPBG) for the National Park. The BR uses the NP as the core zone and considers itself as ‘a model region for sustainable development’ (I_BRBL) rather than as a protected area. It concentrates on the regional economy with, for example, local agricultural products. The BR has no legal power to enforce rules and is ‘an additional institution which other regions in Bavaria do not have’ (I_BRBL) – ‘a playing ground’ (I_NPBG) with ‘many, many more chances than restrictions’ (I_NPBG).

The BR administration works on two main tasks: (1) informing local people what the BR is, and (2) initiating projects and cooperation. Until the early 2010s, local people saw the BR in the ‘nature conservation corner’ (I_BRBL). The BR administration tries to change this understanding by stressing topics which ‘basically address every area of life of the population’ (I_BRBL). Nevertheless, ‘the National Park is the dominant brand’ (I_NPBG). The BR administration is building a network of different administrations, municipalities, and the tourism sector. Additionally, it engages in the local group of the European rural development programme (LEADER) and cooperates with the county departments of economic development, health, education, and climate. However, it has ‘just no capacities to engage with individual people’ (I_BRBL) or to initiate a bottom-up process in order to create a broader foundation.

Legitimacy – need to communicate

The adaption of the BR title ‘without forerun and without the involvement of the citizens […] was definitely a disadvantage’ (I_BRBL). In the 2000s, the discussion, which resulted in the extension and renaming of the BR, ‘was a sheer political discussion’ (I_NPBG). Still, nowadays, ‘many do not know that they live in a Biosphere Reserve’ (I_BRBL). Consequently, the local population has limited enthusiasm for the BR. For this reason, the main task is to engage with local people, raise awareness about possibilities, and rectify ‘crude superficial knowledge’ (I_BRBL) about the BR with the result ‘that people understand it more and more’ (I_BRBL). Nobody opposes the BR and mayors hope for additional financial opportunities through the BR.

Niedersächsisches Wattenmeer

Process – limited political attention

Since its creation in 1992, the BR Niedersächsisches Wattenmeer has been coherent with the National Park concerning extent and activities (Farke and Potel Citation1995). After the conceptual shift in 1995, the state government neglected the BR because it focused on a ‘discussion around the National Park’ which local residents fuelled who opposed use and access restrictions (NMU, Citation2005a, Citation2005b). In the early 2000s, the BR administration realized that the shift of the BR concept posed new requirements. Since then, the enlargement of the transition zone has been a major concern. In 2005, the state government decided to maintain the BR title without any additional designated area (NMU, Citation2005a). Nevertheless, the national MAB-Committee demanded an extended transition zone. In 2013, the BR administration began searching for municipalities along the coastline to join the transition zone. In fall 2017 [after the interviews], the German MAB-committee approved this endeavour (Nationalpark Wattenmeer Citation2017).

Structure – three overlapping designations and haziness

The BR administration is one of four departments within the National Park administration which is a ‘conscious’ (I_NW) decision. It belongs to the state ministry for environment with the effect that the state government takes major decisions and the administration executes them. The area is also part of the UNESCO World Nature Heritage Site administered by the trilateral Common Wadden Sea Secretariat located in the same building as the National Park administration.

The three designations partly overlap creating an administrative, jurisdictional, thematic, and spatial complexity which is challenging to understand and communicate. The distribution of tasks and responsibilities is hazy. For example, all three deal with tourism and the local economy. While the local population has embraced the National Park and the World Heritage designations, there ‘is now a problem with the communication […] of the biosphere reserve’ (I_NW).

The BR mainly works on the extension of the transition zone because the zone currently makes up less than 1% of the BR area (BfN Citation2017). Three municipalities have joined the BR as ‘partners’ (I_NW) and other municipalities gave ‘very positive feedback’ (I_NW). The BR administration mainly communicates and cooperates with mayors or municipal councils. The municipalities joining the transition zone commit to ‘a common declaration’ (I_NW) which is legally non-binding. The aim is to have a shared vision, but ‘the speed of and the exact topics for sustainable development are not dictated’ (I_NW). The BR faces opposition mainly from agricultural stakeholders. ‘For example, during a public information event, agriculture heavily mobilized against [the BR]’ (I_NW). The BR administration tries ‘to explain as much as possible and show the opportunities’ (I_NW) to local people in order to inform and clarify misunderstandings.

Legitimacy – participation in the future

Participation has not been part of the BR. The BR administration interacts with municipalities and holds information events for the public. Participation is part of the envisioned governance of the future, enlarged BR. However, the BR administration wonders: ‘How and in which way do we ensure that in the future, processes take place in the transition zone that evolve from within the population?’ (I_NW).

The BR experiences ‘mistrust’ (I_NW) from the local population concerning the extension of the transition zone as people fear restrictions on land use. ‘Farmers tell you […]: we made bad experiences with the designation of Natura2000 sites. We fear that one day somebody will use the situation, we agree to now, to say that we then will have to fulfill totally different requirements. […] Another point […] farmers say that as soon as they as farmers are part of a protected area […], their property incurs immediate depreciation’ (I_NW). But, the BR has ‘enough nature protection’ (I_NW) and wants to extend the transition zone to ‘secure the value of the region in the future through […] sustainability dimensions […] in the business sector: be it tourism or also agriculture’ (I_NW). This illustrates that trust, knowledge, and objectives are not aligned between the different local actors.

Discussion

Top-down, monocentric governance has characterized the past of the three areas. When creating the BRs and also when reacting to the conceptual shift after 1995, politicians made decisions and the administrations executed them without any public involvement. The three areas are no outliers: still today, BRs and many other protected areas are established and managed in a top-down way (Wallner et al. Citation2007; Plieninger et al. Citation2015). More multi-level, participative governance could allow both to balance and accommodate different interests and to rectify crude knowledge and misconceptions in the population. It seems challenging for the administrations of the two remaining BRs to adopt the new role as a moderator and a facilitator rather than an implementer. Especially, the administration of the BRs seem less grounded in the local population, and especially the BR Niedersächsisches Wattenmeer seems to act more as a state-level administration. Decision-making and administrative structures seem not flexible enough to accommodate the demands posed on the BRs since 1995.

Spatial, administrative, and thematic overlaps between BRs and other designations like the National Parks hamper a clear distinction. This is a common challenge for multi-level governance (Görg et al. Citation2014). BRs should be distinguishable from other areas that focus on nature conservation (Dudley Citation2008). However, many protected areas are increasingly pursuing an integrative approach by having visitor centres, improving accessibility, and promoting local products (Hammer et al. Citation2016; Huber and Arnberger Citation2016; Mathevet et al. Citation2016; Hausner et al. Citation2017). In all three areas, the National Parks are the bigger trademarks mainly for tourism purposes and as such, they do not pursue only nature conservation (Coetzer et al. Citation2014). In the Bayerischer Wald, tourism based on the National Park is a major aspect of the local economy. The BRs need to dissociate from the National Park in order to create clear distinctions for laypersons. In the BR Berchtesgadener Land, the separation of the two administrations supports this distinction, while in the BR Niedersächsisches Wattenmeer, a clear distinction is challenging since there is only one administration without a clear assignment of responsibilities between the three designations. People can only understand the difference with a clear distinction based on the clear objectives of the various administrations.

Local people’s support is crucial for the legitimacy and the final success of a designation (Bennett Citation2016). In both BRs, local people fear restrictions and in the BR Niedersächsisches Wattenmeer they partly even oppose the BR. They cannot differentiate the BR from other protected areas such as National Parks (Wallner et al. Citation2007; Hernes and Metzger Citation2017; Price Citation2017). Local people, but also scientists and politicians seem unaware of the specific characteristics of BRs (Reed Citation2016). The lack of understanding can function as a negatively reinforcing feedback loop (Holling Citation1973; Folke Citation2006; Tidball et al. Citation2017) because mistrust and fear continue growing when people think a designation comes with rules and restrictions affecting them (Huber and Arnberger Citation2016). More educational work and networking is necessary to create knowledge and trust.

Experiences, people had with the execution of nature conservation in the past, influence their relationships with the designated areas. All areas went through periods in which the local population opposed the National Parks. Nowadays, people embrace or at least accept them. This was possible due to a lot of attention and (human and financial) resources invested to improve the relationship. However, this kind of support and political commitment is not as strong for the BRs. The two remaining BRs are equipped only with a minimum of resources and staff concerning their spatial extent. The adequate equipment and political support are pivotal for the success to implement the conceptual shift. The BR administrations need not only to implement the conceptual shift and work with a broad range of stakeholders but also need to make their objectives known and build relationships and trust with the local population.

The new phase of conservation with its integrated approach poses challenges to the implementation because the new combination stretches over well-established sectors. The development from conservation to something more comprehensive needs leeway and bravery to explore new pathways. In the BR Berchtesgadener Land, they use the leeway describing the BR as ‘playing ground’ with opportunities. Its administrative position in the district government and its physical location in the country administration gives the BR administration freedom and autonomy. In the Bayerischer Wald, the National Park administration and the surrounding municipalities have picked single topics that appeal to them, but a comprehensive integrated approach is missing. Taking the idea of integrated approaches serious and implementing it on the ground requires a strategic plan on how to bring stakeholders together even when are they doubtful. This seems challenging and offers future research opportunities.

We should reflect the developments in our research work and not only point at administrations and local governments for not adequately implementing the conceptual conservation shift. We need to consider general and contextual challenges for the implementation of theories and concepts discussed in our research. Even if they are developed based on empirical research, their implementation in other contexts might face challenges. For this reason, empirical work should not only inform theoretical and conceptual research, but we should also allow for space in our theories and concepts to adapt them to the local circumstances. On a theoretical level, this means giving different knowledge systems space in our work. For empirical work, this means that we need to consider much more the context, recognize the local history, norms, and objective. This might seem profane sometimes, but might be the key for a complete understanding of the local situation and in order to find pathways to sustain human well-being and biodiversity.

Acknowledgments

I want to thank the Biosphere Reserve administrations and National Park administrations and the interviewees for their time, honesty and support of this work. In addition, comments by Kimberly A. Nicholas, Stefan Partelow, the handling editor and two anonymous reviewers on earlier versions of this paper greatly helped to improve the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bennett NJ. 2016. Using perceptions as evidence to improve conservation and environmental management. Conserv Biol. 30(3):582–592. doi:10.1111/cobi.12681.

- Bridgewater P. 2016. The Man and Biosphere programme of UNESCO: rambunctious child of the sixties, but was the promise fulfilled? Curr Opin Environ Sustainability. 19:1–6. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2015.08.009.

- Bryman A. 2016. Social Research Methods. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bundesamt für Naturschutz (BfN). 2016. Daten zur Natur 2016. Bonn: Bundesamt für Naturschutz.

- Bundesamt für Naturschutz (BfN). 2017. Biosphärenreservate in Deutschland. https://www.bfn.de/fileadmin/BfN/gebietsschutz/Dokumente/BR_Tab_06_2017_barrierefrei.pdf.

- Coetzer KL, Witkowski ETF, Erasmus BFN. 2014. Reviewing biosphere reserves globally: effective conservation action or bureaucratic label? Biol Rev. 89(1):82–104. doi:10.1111/brv.12044.

- Dudley N, Eds. 2008. Guidelines for applying protected area management categories. Gland (Switzerland): IUCN.

- Eagles PFJ, Romagosa F, Buteau-Duitschaever WC, Havitz M, Glover TD, McCutcheon B. 2013. Good governance in protected areas: an evaluation of stakeholders’ perceptions in British Columbia and Ontario Provincial Parks. J Sustainable Tourism. 21(1):60–79. doi:10.1080/09669582.2012.671331.

- Erdmann K-H, Kerner HF, Köppel J, Mayerl D, Mattern K, Pokorny D, Schönthaler K, Spandau L, Weidenhammer S. 1995. Leitlinien für Schutz, Pflege und Entwicklung der Biosphärenreservate in Deutschland. Pages 1–59 in Ständige Arbeitsgruppe der Biosphärenreservate in Deutschland, editor. Biosphärenreservate in Deutschland - Leitlinien für Schutz, Pflege und Entwicklung. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer Verlag.

- Farke H, Potel P. 1995. Biosphärenreservat Niedersächsiches Wattenmeer. in Ständige Arbeitsgruppe der Biosphärenreservate. In: Deutschland, editor. Biosphärenreservate in Deutschland - Leitlinien für Schutz, Pflege und Entwicklung. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; p. 127–135.

- Folke C. 2006. Resilience: the emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Global Environ Change. 16(3):253–267. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.04.002.

- Görg C, Spangenberg JH, Tekken V, Burkhard B, Thanh Truong D, Escalada M, Luen Heong K, Arida G, Marquez LV, Victor Bustamante J, et al. 2014. Engaging local knowledge in biodiversity research: experiences from large inter- and transdisciplinary projects. Interdiscip Sci Rev. 39(4):323–341. doi:10.1179/0308018814Z.00000000095.

- Hammer T, Mose I, Siegrist D, Weixlbaumer N. editors. 2016. Parks of the future: protected areas in Europe challenging regional and global change. München: oekom Verlag.

- Hausner VH, Engen S, Bludd EK, Yoccoz NG. 2017. Policy indicators for use in impact evaluations of protected area networks. Ecol Indic. 75:192–202. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.12.026.

- Hernes MI, Metzger MJ. 2017. Understanding local community’s values, worldviews and perceptions in the Galloway and Southern Ayrshire biosphere reserve, Scotland. J Environ Manage. 186:12–23. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.10.040.

- Holling CSS. 1973. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 4(1):1–23. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000245.

- Huber M, Arnberger A. 2016. Opponents, waverers or supporters: the influence of place-attachment dimensions on local residents’ acceptance of a planned biosphere reserve in Austria. J Environ Plann Manage. 59(9):1610–1628. doi:10.1080/09640568.2015.1083415.

- Ishwaran N, Persic A, Tri NH. 2008. Concept and practice: the case of UNESCO biosphere reserves. Int J Environ Sustainable Dev. 7(2):118. doi:10.1504/IJESD.2008.018358.

- Linnell JDC, Kaczensky P, Wotschikowsky U, Lescureux N, Boitani L. 2015. Framing the relationship between people and nature in the context of European conservation. Conserv Biol. 29(4):978–985. doi:10.1111/cobi.12534.

- Lockwood M. 2010. Good governance for terrestrial protected areas: A framework, principles and performance outcomes. J Environ Manage. 91(3):754–766. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.10.005.

- Mace GM. 2014. Whose conservation? Science. 345(6204):1558–1560.

- Martín-López B, van Oudenhoven APE, Balvanera P, Crossman ND, Parrotta J, Rusch GM, Schröter M, Smith-Hall C. 2019. Ecosystems and People – an inclusive, interdisciplinary journal. Ecosyst People. 15(1):1–2. doi:10.1080/26395908.2018.1540160.

- Mathevet R, Thompson J, Folke C, Chapin FS. 2016. Protected areas and their surrounding territory: social-ecological systems in the context of ecological solidarity. Ecol Appl. 26(1):5–16. doi:10.1890/14-0421.

- Nationalpark Bayerischer Wald. 2010. 40 Jahre Nationalpark-Geschichte und -Geschichten: festschrift 40 Jahre Nationalpark Bayrerischer Wald. Grafenau: Nationalpark Bayerischer Wald.

- Nationalpark Wattenmeer. 2017, September 1. Niedersächsisches Wattenmeer als UNESCO-Biosphärenreservat bestätigt.

- Niedersächsisches Ministerium für Umwelt, Energie, B and Klimaschutz (NMU). 2005a. UNESCO Biosphärenreservat Niedersächsisches Wattenmeer: Sander - Wir wollen am Biosphärenreservat festhalten.

- Niedersächsisches Ministerium für Umwelt, Energie, B and Klimaschutz (NMU). 2005b. UNESCO Biosphärenreservat Niedersächsisches Wattenmeer: Sander - Menschen in der Region sind gefragt.

- Plieninger T, Kizos T, Bieling C, Le Dû-Blayo L, Budniok M-A, Bürgi M, Crumley CL, Girod G, Howard P, Kolen J, et al. 2015. Exploring ecosystem-change and society through a landscape lens: recent progress in European landscape research. Ecol Soc. 20(2):art5. doi:10.5751/ES-07443-200205.

- Price MF. 2017. The re-territorialisation of biosphere reserves: the case of Wester Ross, Northwest Scotland. Environ Sci Policy. 72:30–40. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2017.02.002.

- Price MF, Park JJ, Bouamrane M. 2010. Reporting progress on internationally designated sites: the periodic review of biosphere reserves. Environ Sci Policy. 13(6):549–557. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2010.06.005.

- Reed M, Massie M. 2013. Embracing ecological learning and social learning: UNESCO biosphere reserves as exemplars of changing conservation practices. Conserv Soc. 11(4):391. doi:10.4103/0972-4923.125755.

- Reed MG. 2016. Conservation (In)Action: renewing the relevance of UNESCO biosphere reserves. Conserv Lett. 9(6):448–456. doi:10.1111/conl.2016.9.issue-6.

- Schliep R, Stoll-Kleemann S. 2010. Assessing governance of biosphere reserves in Central Europe. Land Use Policy. 27(3):917–927. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2009.12.005.

- Stoll-Kleemann S, Welp M. 2008. Participatory and integrated management of biosphere reserves. GAIA - Ecol Perspect Sci Hum Econ. 17:(S1):161–168.

- Tanaka T, Wakamatsu N. 2018. Analysis of the governance structures in Japan’s biosphere reserves: perspectives from bottom–up and multilevel characteristics. Environ Manage. 61(1):155–170. doi:10.1007/s00267-017-0949-6.

- Tengö M, Brondizio ES, Elmqvist T, Malmer P, Spierenburg M. 2014. Connecting diverse knowledge systems for enhanced ecosystem governance: the multiple evidence base approach. Ambio. 43(5):579–591. doi:10.1007/s13280-014-0501-3.

- Tidball KG, Metcalf S, Bain M, Elmqvist T. 2017. Community-led reforestation: cultivating the potential of virtuous cycles to confer resilience in disaster disrupted social–ecological systems. Sustainability Sci. 13(3):797–813.

- UNESCO. 1996. Biosphere reserves: the Seville strategy and the statutory framework of the world network. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2017a. Fulfilling the three functions. http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/environment/ecological-sciences/biosphere-reserves/main-characteristics/functions/.

- UNESCO. 2017b. Biosphere reserves withdrawn from the world network of biosphere reserves. http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/environment/ecological-sciences/biosphere-reserves/withdrawal-of-biosphere-reserves/.

- UNESCO. n.d.. Wadden sea. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1314.

- van Oudenhoven APE, Martín-López B, Schröter M, de Groot R. 2018. Advancing science on the multiple connections between biodiversity, ecosystems and people. Int J Biodivers Sci Ecosyst Serv Manage. 14(1):127–131. doi:10.1080/21513732.2018.1479501.

- Wallner A, Bauer N, Hunziker M. 2007. Perceptions and evaluations of biosphere reserves by local residents in Switzerland and Ukraine. Landsc Urban Plan. 83(2–3):104114. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2007.03.006.