ABSTRACT

Many scientists agree that the increasing disconnect between modern societies and nature is one of the greatest sustainability challenges of our time. At the level of individuals, human-nature connectedness has shown to be positively correlated with pro-environmental behavior and well-being. Reconnecting humans to nature may therefore constitute a leverage point for sustainability transformation. While a more comprehensive understanding of the multiple dimensions of human-nature connectedness is vital, many studies inquire exclusively into cognitive connections to nature, often following quantitative approaches. In this paper, I examine the potential of arts-based methods to overcome the reliance on language and unveil nuances of human-nature connectedness that lie beyond words. Arts-based research is capable of tapping into emotions and embodied experiences, which are often neglected in science. Since most art forms entail a non-verbal component, using them in the research process may transcend the cognitive to elicit unspoken knowledge. This makes arts-based research eligible particularly for investigating and enhancing emotional connections with nature. Nonetheless, arts-based methods pose specific challenges in data collection, data interpretation, and data representation and should be carefully integrated alongside quantitative and qualitative methods. This paper aims to provide valuable impulses for all researchers, artists, and practitioners concerned with human-nature connectedness.

EDITED BY:

1. Introduction

The increasing disconnect between humans and nature has led to an ‘extinction of experience’ (Pyle Citation1993; Miller Citation2005; Soga and Gaston Citation2016) and is arguably one of the main drivers of unsustainability (Zylstra et al. Citation2014; Pett et al. Citation2016). Lately, there is heightened interest in reconnecting humans to nature on both societal (Pyle Citation2003; Folke et al. Citation2011; Cooke et al. Citation2016) and individual levels (Mayer and Frantz Citation2004; Nisbet et al. Citation2009). On the individual level, this has given rise to the notion of human-nature connectedness (Schultz Citation2002; Zylstra et al. Citation2014). As human-nature connectedness has shown to be positively correlated with pro-environmental behavior (e.g. Schultz Citation2001; Mayer and Frantz Citation2004; Nisbet et al. Citation2009; Gosling and Williams Citation2010; Hoot and Friedman Citation2011; Geng et al. Citation2015) as well as human well-being (e.g. Howell et al. Citation2011; Cervinka et al. Citation2012; Nisbet and Zelenski Citation2013; Capaldi et al. Citation2014; Trigwell et al. Citation2014; Zelenski and Nisbet Citation2014), reinforcing it may constitute a deep leverage point (Meadows Citation1999) for sustainability transformation (Abson et al. Citation2017; Ives et al. Citation2018). In this perspective paper, I first provide a brief overview of the existing research on human-nature connectedness, then examine the potential of integrating arts-based approaches, and finally discuss the implications from a leverage points perspective.

2. Existing research on human-nature connectedness

Human-nature connectedness is not a clear concept itself but rather a ‘core construct’ (Bogdon Citation2016, p. 18) that encompasses several concepts such as connectivity with nature (Dutcher et al. Citation2007), love and care for nature (Perkins Citation2010), and dispositional empathy with nature (Tam Citation2013b). The literature on the topic is fragmented across disciplines and relatively incoherent with regards to conceptions and measurements of connections to nature (Ives et al. Citation2017, Citation2018). Based on a broad literature review, Zylstra et al. (Citation2014, p. 119) provide an operationally useful definition of human-nature connectedness as ‘a stable state of consciousness comprising symbiotic cognitive, affective, and experiential traits that reflect a realization of the interrelatedness between one’s self and the rest of nature’. This definition illustrates that human-nature connectedness is a subjective construct that is composed of at least three interacting dimensions: cognitive (knowledge and beliefs about nature), affective (feelings and emotions toward nature), and experiential (actions and experiences in/with nature) connections (Nisbet et al. Citation2009; Bragg et al. Citation2013; Zylstra et al. Citation2014). Although this tripartite view of human-nature connectedness is most commonly found in the literature, more recent studies suggest five dimensions: material, experiential, cognitive, emotional (cf. affective), and philosophical connections (Ives et al. Citation2017, Citation2018). However, it should be noted that the two additional dimensions, i.e. material connections such as resource use and extraction, and philosophical connections that reflect different world views on nature, bear more relevance on a societal than on an individual level (Ives et al. Citation2018).

To understand the complex ways in which these relations to nature form human-nature connectedness, scholars have followed various methodological approaches. Empirical research has been biased towards quantitative approaches, primarily in the form of surveys involving psychometric scales (Keniger et al. Citation2013; Zylstra et al. Citation2014; Restall and Conrad Citation2015; Ives et al. Citation2017). Several of these measures have been developed over the last two decades, ranging in scope and focus but overlapping significantly (Tam Citation2013a). They constitute a useful instrument for quantifying human-nature connectedness, allowing for statistical analyses and correlations with other variables. However, these scales may not correspond to the multidimensionality of human-nature connectedness for several reasons: (a) most of them inquire exclusively into cognitive nature connections (Restall and Conrad Citation2015); (b) their forced-choice questions do not account for different mental models of the natural environment (Fischer and Young Citation2007; Shepardson et al. Citation2007) and inherently subjective definitions of nature (Thomashow Citation1995; Louv Citation2008; Cosgriff et al. Citation2009; Freeman et al. Citation2015; Windhorst and Williams Citation2015); and (c) they all rely on self-report (Schultz et al. Citation2004; Schultz and Tabanico Citation2007; Bruni and Schultz Citation2010; Zylstra et al. Citation2014). Furthermore, it is questionable whether language-based methods in general are capable of uncovering intangible dimensions such as emotions, experiences, and spirituality (Cosgriff et al. Citation2009; Morse Citation2011; Barone and Eisner Citation2012; Zylstra et al. Citation2014).

Apart from quantitative studies on human-nature connectedness, some scholars have thus chosen qualitative and mixed-methods approaches, mostly using interviews (Ives et al. Citation2017). In doing so, some of the above-mentioned shortcomings of exclusively quantitative approaches can be eluded. For example, to accommodate for the quantitative bias towards cognitive connections, interviewees’ responses were analyzed along multiple dimensions of human-nature connectedness in several studies (e.g. Guiney and Oberhauser Citation2009; Cosgriff Citation2011; Silvas Citation2013; Materia Citation2016). Unlike surveys, interviews allow for a conversational inquiry into highly personal terms such as ‘connectedness’ (Cosgriff et al. Citation2009; Zylstra et al. Citation2014), resolving potential unclarities about the research process and its results for both the researcher and the interviewees (Klassen Citation2010). However, interviews share some of the main disadvantages of psychometric scales, namely the reliance on self-report and language. During a graduate research project titled ‘RECONNECT’, my colleagues (full names in Acknowledgements) and I were constantly confronted with this apparent dilemma. By interviewing members of urban gardening projects, nature conservation groups, and scout organizations in the metropolitan areas of Hamburg, Germany, and Phoenix, AZ, USA, we aimed at scrutinizing the relation between human-nature connectedness and pro-environmental behavior in the two different cultural contexts. During our study, interviewees repeatedly articulated how difficult it was for them to express their connections to nature in words. Interestingly, few studies on human-nature connectedness draw a substantive proportion of their data from qualitative methods that are not completely language-based, e.g. participant observation (Morse Citation2011; Vroegop Citation2014) or the photovoice method (Windhorst and Williams Citation2015). This led me to the idea that the newly emerging field of arts-based research, which ‘values preverbal ways of knowing’ (Heinrichs Citation2018, p. 134) could hold promising methods to go beyond words and uncover new nuances of human-nature connectedness.

3. A turn to the arts

Art is the bridge between humans and nature.

Friedensreich Hundertwasser, 1983

(translated from German)

(Hundertwasser Citation1983, p. 136)

Science and the arts inarguably apply separate logics and seek largely different goals. However, since both share basic characteristics such as the thrive for innovation and imagination, some scholars argue that they should be seen as complimentary partners (McNiff Citation1998; Scheffer et al. Citation2015). The growing hybridization between the arts and science over the last decades has thus led to the development of arts-based research (Heras and Tàbara Citation2014; Heinrichs Citation2018). There are several methodologies that incorporate the arts into knowledge production, such as a/r/tography (Springgay et al. Citation2008) and arts-informed research (Cole and Knowles Citation2008), which have different disciplinary foci and differ slightly in how they let the arts guide the research process. A/r/tography, for example, is rooted in education, the a/r/t standing for artist/teacher/researcher. Arts-informed research is defined as ‘a mode of qualitative research in the social sciences that is influenced by, but not based in, the arts broadly conceived’ (Cole and Knowles Citation2008, p. 59). For the scope of this perspective paper, these minor differences can be considered secondary, which is why I will use arts-based research as an umbrella term in line with others (Heras and Tàbara Citation2014; Leavy Citation2017) (for a comparison between arts-based methodologies, see e.g. Knowles and Cole Citation2008; Chilton Citation2013). As arts-based research can guide different phases of the research process, e.g. data collection or representation (Leavy Citation2009), I conceptualize it as the methodological ‘use of the arts as objects of inquiry as well as modes of investigation’ (McNiff Citation1998, p. 15). It should also be noted here that arts-based research processes can clearly vary between different art forms (for a further categorization of arts-based research according to art forms, see e.g. Knowles and Cole Citation2008; Leavy Citation2009). Arts-based research aims specifically at integrating multiple forms of knowledge, in particular scientific knowledge and what is sometimes referred to as ‘artistic knowledge’ (Jagodzinski and Wallin Citation2013; Richardson Citation2016). Furthermore, this type of research is distinct in its capacity to transcend the cognitive mind and tap into human faculties such as emotions, (embodied) experiences, and identities (Leavy Citation2009; Barone and Eisner Citation2012; Heras and Tàbara Citation2014; Ives et al. Citation2018), which are often neglected by generally abstract and reductive scientific procedures (Leavy Citation2017; Heinrichs Citation2018).

Considering these characteristics of arts-based research on the one hand and the complex web of connections between humans and nature on the other hand, integrating arts-based methods into research approaches on human-nature connectedness seems easily justifiable. While numerous studies address the broader intersection of nature and the arts, I only found three that in fact apply arts-based methods to gain insights about human-nature connectedness (see for an overview). For example, Gilbertson (Citation2012) integrated arts-based methods into a mixed-methods study exploring the effects of a role-play on children’s sense of connectedness in two phases: firstly, as an education intervention (the role-play itself) and secondly, for data collection through the medium of drawing. Although her results indicated no significant changes in quantifiable human-nature connectedness, children departed from an anthropocentric view of their environment and started valuing nature more intrinsically. Similarly, Gray and Birrell (Citation2015) analyzed high school students’ artistic outputs ranging from poetry and painting to dance, music and films to investigate the changes in human-nature connectedness induced by an arts-based outdoor learning program (see also: Gray and Thomson Citation2016). In their study, participation in the program led to greater connectedness in numbers as well as the establishment of new emotional connections to nature, suggesting ‘that the Arts [sic] leverage deep engagement and links with the natural environment’ (Gray and Birrell Citation2015, p. 341). In the most recent study, researchers collaborated with an artist using an arts-based method called ‘social land art’, which included the supported design of participants’ own art installations as well as reflections on their meanings of and relations with nature (Riechers et al. Citation2019). Their results underline the capacity of arts-based research to reveal participants deep emotional connections to nature and to specific landscapes, which the authors are convinced ‘could not have been elicited with conventional research methods’ (Riechers et al. Citation2019, p. 6). However, it should be noted that the results of the study largely draw on qualitative data connected to the created art, i.e. audio recordings of group discussions, participant observations, and other qualitative workshop data, rather than using the art itself as a primary data source. This exemplifies the above-mentioned different methodologies that are subsumed under the umbrella of arts-based research and could also be seen as an indicator that this relatively young type of research is yet to be well-defined.

Table 1. Overview of the three studies applying arts-based methods in research approaches on human-nature connectedness as well as the experiences from the participatory arts workshop ‘Human.Nature.Art’ as part of the graduate research project RECONNECT.

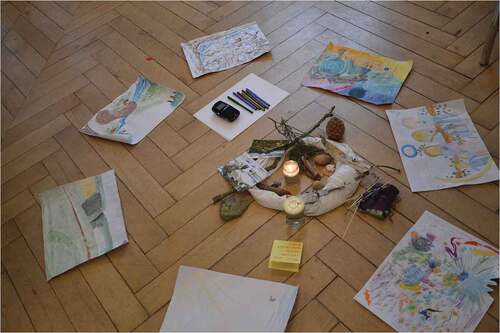

My own experiences of an arts-based research process on human-nature connectedness serve as a good supplement to the three studies described. As part of the above-mentioned graduate research project RECONNECT, my colleague Lisa Schlesinger and I hosted a participatory arts workshop ‘Human.Nature.Art’ on March 5th, 2017 in Lüneburg, Germany. The participants – seven female university students involved in urban gardening projects or nature conservation groups – were asked to embody their connections to nature through a theater exercise rooted in the work of Augusto Boal’s Theater of the Oppressed (Boal Citation2002) and to visually depict them in a guided drawing exercise, followed by immediate reflective conversations in the group as well as individual written reflections. In the context of this perspective paper, three aspects seem particularly worth highlighting to me. First, compared to the interviews conducted within the frame of the RECONNECT project, the arts-based methods revealed new nuances of emotional and experiential human-nature connectedness. Both the theater exercise and the drawings included notions of concealment and emotional security in nature that had not surfaced during the interviews, and particularly the drawings let us draw new inferences about the sensory perceptions and overall atmospheres that constitute participants’ nature experiences (see for an impression of the drawings). Second, participants’ verbal reflections vitally supported our analyses of their artistic output, making us recognize the value of complementing arts-based methods with qualitative methods for data analysis. Third, both participants and researchers perceived the workshop as a unique and enjoyable learning experience in which we co-created new knowledge on our personal connections to nature. provides an overview of the experiences from the workshop alongside the three studies described.

Figure 1. An impression from the workshop ‘Human.Nature.Art’: some of the participants’ drawings of their connections with nature. Photo: Berta Martín-López.

The examples presented above suggest that research on human-nature connectedness could benefit from serious consideration of arts-based approaches. Arts-based methods can unveil feelings (Barone and Eisner Citation2012; Fernández-Giménez Citation2015), which makes them eligible particularly for investigating emotional connections to nature. In valuing the need to experience as a complementary goal of the research process (McNiff Citation1998), arts-based research may also provide new insights into experiential connections with nature and serve as a countermeasure to the ‘extinction of experience’ (Miller Citation2005; Soga and Gaston Citation2016). Furthermore, as almost all art forms entail an important non-verbal component, they allow for eliciting tacit and unspoken knowledge (McNiff Citation1998) and expressing connections with nature through mediums and processes that go beyond words (Leavy Citation2009; Barone and Eisner Citation2012). Naturally, this entails challenges in data collection, data analysis, and in particular data representation (Eisner Citation1997), not at last because publishing in academic journals requires transferring research into writing (Prior Citation2018). Although it is sometimes argued that art should speak for itself (McNiff Citation1998), triangulating arts-based methods with quantitative or qualitative methods particularly for data collection may thus be necessary to assure the good quality of analyses and interpretations (Leavy Citation2009). As the examples presented above indicate, following mixed-methods approaches seems promising and Savin-Baden and Wimpenny (Citation2014) particularly recommend combining arts-based methods with ethnographic research, phenomenology, and narrative inquiry. Other recommendations include the clarification of one’s philosophical paradigms, the purposeful sampling of research participants as well as conducting a broad literature-review on the relation between the research topic and the arts (Leavy Citation2017). Close collaboration with artists, as exemplified by Riechers et al. (Citation2019), as well as the engagement of the researchers themselves with the art forms they intend on using can further help to ‘find a way to address both the language of the arts and the language of the rational mind’ (Kossak Citation2018, p. 65) (Heinrichs Citation2018). With this perspective paper, I want to invite researchers to integrate arts-based methods alongside conventional research methods in their research on human-nature connectedness. While this requires careful consideration of the different paradigms, theories, and quality criteria that characterize quantitative, qualitative, and arts-based research (Johnson and Onwuegbuzie Citation2004; Rolling Citation2010; Moon et al. Citation2016; Leavy Citation2017), it might help alter a deep leverage point for sustainability transformation and thus be well worth the effort.

4. Arts-based research as a lever for sustainability transformation

Assuming that reconnecting humans to nature indeed constitutes a deep leverage point for sustainability transformation (Abson et al. Citation2017; Ives et al. Citation2018), the question remains which levers need to be pulled or in other words, which system interventions could be applied to foster human-nature connectedness. Ives et al. (Citation2018) argue that what they call ‘inner connections’, i.e. emotional and philosophical connections to nature, are more likely to influence deeper realms of leverage, such as the underlying goals and values of a system, than ‘outer connections’, i.e. material and experiential connections to nature, that rather effect shallower realms of leverage, such as the parameters of a system. I have shown that in research on human-nature connectedness, considering arts-based approaches has the potential to evoke and reinforce particularly these deep emotional connections and thus be a powerful system intervention. However, as it is one of the key advantages of a leverage points perspective that it allows for examining and potentially making use of interactions between different leverage points (Fischer and Riechers Citation2019), it is interesting to consider what else the integration of arts-based research could result in. For example, by uncovering individual emotional connections to nature (a deep leverage point), the use of arts-based methods can lead to philosophical reflections on how society in general should interact with nature (an even deeper leverage point) (Gilbertson Citation2012; Gray and Birrell Citation2015), which in turn may possibly influence shallower leverage points, such as individual leisure time spent in nature (an experiential connection to nature) or food consumption (a material connection to nature) (Ives et al. Citation2018). Undoubtedly, more empirical research is needed to help foster our understanding of such ‘chains of leverage’ (Fischer and Riechers Citation2019), but when extending the scope from human-nature connectedness to a broader environmental sustainability context, several studies support the idea that arts-based research could facilitate these different types of changes in a system (e.g. De Groot and Zwaal Citation2007; Zurba and Berkes Citation2014; Heras and Tàbara Citation2016; Rathwell and Armitage Citation2016; Johansson and Isgren Citation2017; Lopez et al. Citation2018; Goris et al. Citation2019).

From a slightly different view that is not particularly related to human-nature connectedness, embracing arts-based research could also serve as an intervention regarding another deep leverage point for sustainability transformation: the way of producing and using (scientific) knowledge (Abson et al. Citation2017). From a leverage points perspective, this intervention, as it advances the methods and methodologies of research, can be seen as a change in system rules (a relatively deep leverage point) (Meadows Citation1999) and thus system design (one of the four ‘realms of leverage’ (Abson et al. Citation2017)). But not only can arts-based research alter the rules of science through methodological innovation, it also differs from quantitative and qualitative research in its purposes (McNiff Citation1998; Barone and Eisner Citation2012) and its underlying paradigm (Leavy Citation2017; Heinrichs Citation2018). It is not inconceivable that the integration of arts-based approaches may thus cause discussions and ultimately, adaptations to the goals of science or the positivist mindset that is still prevailing in science, both deep leverage points pertaining to system intent (the deepest realm of leverage (Abson et al. Citation2017)). In the light of the discourse about knowledge production and application that has been central to sustainability science from its very beginnings (e.g. Gibbons Citation1994; Brand and Karvonen Citation2007; Spangenberg Citation2011; Lang et al. Citation2012; Miller Citation2013), von Wehrden et al. (Citation2017) call for method plurality and the opening of epistemological and disciplinary barriers underpinning methods. I would argue that embracing arts-based research as a (methodological) boundary objectFootnote1 between the arts and science could initiate promising chains of leverage for the transformation of sustainability science (Heinrichs Citation2018, Citation2019). The practical challenges of integrating arts-based methods into research designs as well as an increased exchange between artists and scientists may lead to important reflections on the goals and performativity of science in the 21st century, e.g. by questioning basic criteria such as reliability and validity (Leavy Citation2009), by targeting broader, non-scientific audiences (Barone and Eisner Citation2012; Kossak Citation2018) or by inviting more creativity, spontaneity, and aesthetical value into research (Leavy Citation2017). While it may seem far-fetched that an intervention regarding system rules bears the potential for such transformative change, it was Donella Meadows herself who argued that ‘power over the rules is real power’ (Meadows Citation1999, p. 14). summarizes how arts-based research could influence leverage points for sustainability transformation.

Table 2. Leverage points that could potentially be influenced by integrating arts-based methods into research on human-nature connectedness and research in general. Realms of leverage (*excluding fourth realm ‘feedbacks’) and leverage points according to Abson et al. (Citation2017).

Although I have focused this perspective paper on arts-based research, there are other possible ways of incorporating the arts into interventions that reconnect humans to nature. In comparing different environmental education programs, those involving activities that revolve around creativity and the arts have shown to increase human-nature connectedness more than programs lacking such a component (Arbuthnott and Sutter, Citation2019; Bruni et al. Citation2017). This might be due to the arts’ capability to emphasize the inherently aesthetic qualities of nature, which can be a meaningful pathway toward nature connectedness (Lumber et al. Citation2017). Similarly, in his recent theory of resonance, Rosa (Citation2016) argues that experiences of the aesthetics of nature are meaningful intersections of two of modernity’s central spheres of resonance, through which humans define, establish and make meaning of their relations with the world: nature and the arts. Therefore, further integration of the arts into environmental education could serve as another effective lever for reconnecting humans to nature. The various university courses and programs that already combine ecology with the arts see e.g. [Blanchet Citation2009; Van Borek Citation2013; Jacobson et al. Citation2016] could be examined with regards to their effect on human-nature connectedness and serve as an inspiration for designing new education interventions. Generally, transdisciplinary collaboration with artists could help in designing and implementing further concrete interventions that foster human-nature connectedness (Zylstra et al. Citation2014; Riechers et al. Citation2019).

5. Conclusions

Considering the increasing interest in the arts-science-sustainability interface, the intention of this perspective paper was to highlight the potentials of triangulating quantitative, qualitative, and arts-based methods to broaden our understanding of human-nature connectedness. Guided by a leverage points perspective, I have shown how the specific qualities of arts-based research may foster particularly but not exclusively emotional connections to nature. As a boundary object between the arts and science, careful integration of arts-based research could also serve to challenge the established rules, goals and underlying paradigm of (scientific) knowledge production, another deep leverage point for sustainability transformation. I invite researchers of all disciplines to find more ways of how the arts can serve as a bridge between humans and nature through (a) empirical exploration of arts-based methods in their research on human-nature connectedness; (b) reflection on the complementarity between science and the arts in general; and (c) transdisciplinary collaboration with artists. Hopefully, this perspective paper may also serve as a valuable impulse for other practitioners concerned with human-nature connectedness, nature conservation, and sustainability in general.

Acknowledgments

I thank Nivedita Biyani, Milena Groß, Sean Murray, Matthias Nachtmann, and Lisa Schlesinger for countless hours of research on human-nature connectedness in the project “RECONNECT”, which has led to the idea for this article. Berta Martín-López has been the greatest academic advisor imaginable. Netra Chhetri, Christian Kitazume, and Eike Niklas Schmidt greatly supported the research process as well. I am grateful for the valuable input on arts-based research that was provided by Petra Biberhofer, Sacha Kagan, Elisa Oteros-Rozas, Federica Ravera, and Sophia van Ruth. I thank the two anonymous reviewers whose comments helped substantially improve the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Interestingly, the School of Art at Arizona State University recently hosted an event titled “Imaginative Futures: Arts-Based Research as Boundary Event“ (https://tinyurl.com/sk2z334, accessed February 9th, 2020)

References

- Abson DJ, Fischer J, Leventon J, Newig J, Schomerus T, Vilsmaier U, Von Wehrden H, Abernethy P, Ives CD, Jager NW, et al. 2017. Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio. Springer Netherlands. 46(1):30–39. doi:10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y.

- Arbuthnott KD, Sutter GC. 2019. Songwriting for nature: increasing nature connection and well-being through musical creativity. Environ Educ Res. Routledge. 25(9):1300–1318. doi:10.1080/13504622.2019.1608425.

- Barone T, Eisner EW. 2012. Arts based research. Thousand Oaks (CA, USA): SAGE Publications.

- Blanchet BKD. 2009. Sustainability program profile, green mountain college puts liberal arts focus on the environment and sustainability. Sustainability: J Rec. 2(5):288–291. doi:10.1089/SUS.2009.9840.

- Boal A. 2002. Games for actors and non-actors. 2nd ed. London/New York (NY, UK/USA): Routledge.

- Bogdon Z. 2016. Towards understanding the development of connectedness-to-nature, and its role in land stewardship behaviour. Waterloo (ON, Canada): University of Waterloo.

- Bragg R, Wood C, Barton J, Pretty J 2013. Measuring connection to nature in children aged 8-12: A robust methodology for the RSPB, A short report for RSPB.

- Brand R, Karvonen A. 2007. The ecosystem of expertise: complementary knowledges for sustainable development. Sustainability: Sci, Pract, Policy. 3(1):21–31.

- Bruni CM, Schultz PW. 2010. Implicit beliefs about self and nature: evidence from an IAT game. J Environ Psychol. Elsevier Ltd. 30(1):95–102. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.10.004.

- Bruni CM, Winter PL, Schultz PW, Omoto AM, Tabanico JJ. 2017. Getting to know nature: evaluating the effects of the get to know program on children’s connectedness with nature. Environ Educ Res. 23(1):43–62. doi:10.1080/13504622.2015.1074659.

- Capaldi CA, Dopko RL, Zelenski JM. 2014. The relationship between nature connectedness and happiness: a meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 5(August):1–15. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00976.

- Cervinka R, Röderer K, Hefler E. 2012. Are nature lovers happy? On various indicators of well-being and connectedness with nature. J Health Psychol. 17(3):379–388. doi:10.1177/1359105311416873.

- Chilton G. 2013. Altered inquiry: discovering arts-based research through an altered book. Int J Qual Methods. 12(1):457–477. doi:10.1177/160940691301200123.

- Cole AL, Knowles JG. 2008. Arts-informed research. In: Knowles JG, Cole AL, editors. Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues. Thousand Oaks (CA, USA): SAGE Publications; p. 55–70.

- Cooke B, West S, Boonstra WJ. 2016. Dwelling in the biosphere: exploring an embodied human–environment connection in resilience thinking. Sustainability Sci. Springer Japan. 11(5):831–843. doi:10.1007/s11625-016-0367-3.

- Cosgriff M. 2011. Learning from leisure: developing nature connectedness in outdoor education. Asia-Pac J Health, Sport Phys Educ. 2(1):51–65. doi:10.1080/18377122.2011.9730343.

- Cosgriff M, Little DE, Wilson E. 2009. The nature of nature: how new zealand women in middle to later life experience nature-based leisure. Leisure Sci. 32(1):15–32. doi:10.1080/01490400903430822.

- De Groot WT, Zwaal N. 2007. Storytelling as a medium for balanced dialogue on conservation in Cameroon. Environ Conserv. 34(1):45–54. doi:10.1017/S0376892907003682.

- Dutcher DD, Finley JC, Luloff AE, Johnson JB. 2007. Connectivity with nature as a measure of environmental values. Environ Behav. 39(4):474–493. doi:10.1177/0013916506298794.

- Eisner EW. 1997. The promise and perils of alternative forms of data representation. Educ Res. 26(6):4–10. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1176961.

- Fernández-Giménez ME. 2015. “A shepherd has to invent”: poetic analysis of social-ecological change in the cultural landscape of the central Spanish Pyrenees. Ecol Soc. 20(4):art29. doi:10.5751/ES-08054-200429.

- Fischer A, Young JC. 2007. Understanding mental constructs of biodiversity: implications for biodiversity management and conservation. Biol Conserv. 136(2):271–282. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2006.11.024.

- Fischer J, Riechers M. 2019. A leverage points perspective on sustainability. People Nat. 1(1):115–120. doi:10.1002/pan3.13.

- Folke C, Jansson Å, Rockström J, Olsson P, Carpenter SR, Chapin FS, Crépin AS, Daily G, Danell K, Ebbesson J, et al. 2011. Reconnecting to the Biosphere. AMBIO. 40(7):719–738. doi:10.1007/s13280-011-0184-y.

- Freeman C, Van Heezik Y, Hand K, Stein A. 2015. Making cities more child- and nature-friendly: a child-focused study of nature connectedness in New Zealand cities. Child Youth Environ. 25(2):176–207. doi:10.7721/chilyoutenvi.25.2.0176.

- Geng L, Xu J, Ye L, Zhou W, Zhou K. 2015. Connections with nature and environmental behaviors. Plos One. Edited by M. Friese. 10(5):e0127247. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0127247.

- Gibbons M. 1994. The new production of knowledge: the dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. Thousand Oaks (CA, USA): SAGE Publications.

- Gilbertson E. 2012. When nature speaks: evoking connectedness with nature in children through role-play in outdoor programming. Colwood (BC, Canada): Royal Roads University.

- Goris M, Van den Berg L, Da Silva Lopes I, Behagel J, Verschoor G, Turnhout E. 2019. Resignification practices of youth in zona da mata, Brazil in the transition toward agroecology. Sustainability (Switzerland). 11:1. doi:10.3390/su11010197.

- Gosling E, Williams KJH. 2010. Connectedness to nature, place attachment and conservation behaviour: testing connectedness theory among farmers. J Environ Psychol. Elsevier Ltd. 30(3):298–304. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.01.005.

- Gray T, Birrell C. 2015. “Touched by the Earth”: a place-based outdoor learning programme incorporating the arts. J Adventure Educ Outdoor Learn. 15(4):330–349. doi:10.1080/14729679.2015.1035293.

- Gray T, Thomson C. 2016. Transforming environmental awareness of students through the arts and place-based pedagogies. LEARNing Landscapes. 9(2):239–260. doi:10.36510/learnland.v9i2.774.

- Guiney MS, Oberhauser KS. 2009. Conservation volunteers’ connection to nature. Ecopsychology. 1(4):187–197. doi:10.1089/eco.2009.0030.

- Heinrichs H. 2018. Sustainability science with Ozzy Osbourne, Julia Roberts and Ai Weiwei. Gaia. 27(1):132–137.

- Heinrichs H. 2019. Strengthening sensory sustainability science-theoretical and methodological considerations. Sustainability (Switzerland). 11:3. doi:10.3390/su11030769.

- Heras M, Tàbara JD. 2014. Let’s play transformations! Performative methods for sustainability. Sustainability Sci. 9(3):379–398. doi:10.1007/s11625-014-0245-9.

- Heras M, Tàbara JD. 2016. Conservation theatre: mirroring experiences and performing stories in community management of natural resources. Soc Nat Resour. Taylor & Francis. 29(8):948–964. doi:10.1080/08941920.2015.1095375.

- Hoot RE, Friedman H. 2011. Connectedness and environmental behavior: sense of interconnectedness and pro-environmental behavior. Int J Transpersonal Stud. 30(1–2):89–100. Available at: http://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies/vol30/iss1/10/.

- Howell AJ, Howell AJ, Dopko RL, Passmore H, Buro K. 2011. Nature connectedness: associations with well-being and mindfulness. Pers Individ Dif. 51(2):166–171. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.03.037.

- Hundertwasser F. 1983. Schöne Wege: gedanken Über Kunst Und Leben. Schurian W Edited by. Munich (Germany): Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag.

- Ives CD, Giusti M, Fischer J, Abson DJ, Klaniecki K, Dorninger C, Laudan J, Barthel S, Abernethy P, Martín-López B, et al. 2017. Human-nature connection: a multidisciplinary review. Curr Opin Environ Sustainability. 26–27(November 2016):106–113. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2017.05.005.

- Ives CD, Abson DJ, von Wehrden H, Dorninger C, Klaniecki K, Fischer J. 2018. Reconnecting with nature for sustainability. Sustainability Sci. 13(5):1389–1397. doi:10.1007/s11625-018-0542-9.

- Jacobson SK, Seavey JR, Mueller RC. 2016. Integrated science and art education for creative climate change communication. Ecol Soc. 21(3):art30. doi:10.5751/ES-08626-210330.

- Jagodzinski J, Wallin J. 2013. Arts-based research: a critique and a proposal. Rotterdam (Netherlands): Sense Publishers.

- Johansson EL, Isgren E. 2017. Local perceptions of land-use change: using participatory art to reveal direct and indirect socioenvironmental effects of land acquisitions in Kilombero Valley, Tanzania. Ecol Soc. 22(1):art3. doi:10.5751/ES-08986-220103.

- Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ. 2004. Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educ Res. 33(7):14–26. Available at: http://edr.sagepub.com/content/33/7/14.short.

- Keniger L, Gaston KJ, Irvine KN, Fuller RA. 2013. What are the benefits of interacting with nature? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 10(3):913–935. doi:10.3390/ijerph10030913.

- Klassen MJ. 2010. Connectedness to nature: comparing rural and urban youths’ relationships with nature. Colwood (BC, Canada): Royal Roads University. Available at: http://media.proquest.com.ezproxy.royalroads.ca/media/pq/classic/doc/2005489331/fmt/ai/rep/NPDF?hl=&cit%3Aauth=Klassen%2C+Michael+Jonathan&cit%3Atitle=Connectedness+to+nature%3A+Comparing+rural+and+urban+youths%27+relationships+with+nature&cit%3Apub=ProQu.

- Knowles JG, Cole AL. 2008. Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues. Thousand Oaks (CA, USA): Sage Publications.

- Kossak M. 2018. A different way of knowing: assessment and feedback in art-based research. In: Prior RW, editor. Using art as research in learning and teaching: multidisciplinary approaches across the arts. Bristol/Chicago (IL, UK, USA): Intellect; p. 61–74.

- Lang DJ, Wiek A, Bergmann M, Stauffacher M, Martens P, Moll P, Swilling M, Thomas CJ. 2012. Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: practice, principles, and challenges. Sustainability Sci. 7(Supplement 1):25–43. doi:10.1007/s11625-011-0149-x.

- Leavy P. 2009. Method meets art: arts-based research practice. New York (NY, USA): The Guilford Press. Available at: http://libraryproxy.griffith.edu.au/login?url=http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/griffith/detail.action?docID=352685.

- Leavy P. 2017. Research design: quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, arts-based, and community-based participatory research approaches. New York (NY, USA): The Guilford Press.

- Lopez FR, Wickson F, Hausner VH. 2018. Finding creative voice: applying arts-based research in the context of biodiversity conservation. Sustainability (Switzerland). 10(6):1–18. doi:10.3390/su10061778.

- Louv R. 2008. Last child in the woods: saving our children from nature-deficit disorder. Chapel Hill (NC, USA): Algonquin Books.

- Lumber R, Richardson M, Sheffield D. 2017. Beyond knowing nature: contact, emotion, compassion, meaning, and beauty are pathways to nature connection. PLoS ONE. 12(5):1–24. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0177186.

- Materia CJ. 2016. Climate state anxiety and connectedness to nature in rural Tasmania. Hobart (Australia): University of Tasmania. Available at: http://eprints.utas.edu.au/23089/.

- Mayer FS, Frantz CM. 2004. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. J Environ Psychol. 24(4):503–515. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2004.10.001.

- McNiff S. 1998. Art-based research. London (UK): Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Meadows D. 1999. Leverage points: places to intervene in a system, world futures. Hartland (VT, USA): The Sustainability Institute.

- Miller JR. 2005. Biodiversity conservation and the extinction of experience. Trends Ecol Evol. 20(8):430–434. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.05.013.

- Miller TR. 2013. Constructing sustainability science: emerging perspectives and research trajectories. Sustainability Sci. 8(2):279–293. doi:10.1007/s11625-012-0180-6.

- Moon K. 2016. A guideline to improve qualitative social science publishing in ecology and conservation journals. Ecol Soc. 21(3):art17. doi:10.5751/ES-08663-210317.

- Morse M. 2011. River experience: a phenomenological description of meaningful experiences on a wilderness river journey. Hobart (Australia): University of Tasmania.

- Nisbet EK, Zelenski JM. 2013. The NR-6: a new brief measure of nature relatedness. Front Psychol. 4(NOV):1–11. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00813.

- Nisbet EK, Zelenski JM, Murphy SA. 2009. The nature relatedness scale: linking individuals’ connection with nature to environmental concern and behavior. Environ Behav. 41(5):715–740. doi:10.1177/0013916508318748.

- Perkins HE. 2010. Measuring love and care for nature. J Environ Psychol. Elsevier Ltd. 30(4):455–463. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.05.004.

- Pett TJ. 2016. Unpacking the people–biodiversity paradox: a conceptual framework. BioScience. 66(7):576–583. doi:10.1093/biosci/biw036.

- Prior RW. 2018. Art as the topic, process and outcome of research within higher education. In: Prior RW, editor. Using art as research in learning and teaching: multidisciplinary approaches across the arts, 43–60. Bristol/Chicago (IL, UK, USA): Intellect. Available at http://hdl.handle.net/2436/622185.

- Pyle RM. 1993. The thunder tree: lessons from an urban wildland. Boston (MA, USA): Houghton Mifflin.

- Pyle RM. 2003. Nature matrix: reconnecting people and nature. Oryx. 37(2):206–214. doi:10.1017/S0030605303000383.

- Rathwell KJ, Armitage D. 2016. Art and artistic processes bridge knowledge systems about social-ecological change: an empirical examination with Inuit artists from Nunavut, Canada. Ecol Soc. 21(2):art21. doi:10.5751/ES-08369-210221.

- Restall B, Conrad E. 2015. A literature review of connectedness to nature and its potential for environmental management. J Environ Manage. 159:264–278. Elsevier Ltd. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.05.022.

- Richardson L. 2016. Sharing knowledge: performing co-production in collaborative artistic work. Environ Plan A. 48(11):2256–2271. doi:10.1177/0308518X16653963.

- Riechers M. 2019. Stories of favourite places in public spaces: emotional responses to landscape change. Sustainability. 11(14):3851. doi:10.3390/su11143851.

- Rolling JH Jr. 2010. A paradigm analysis of arts-based research and implications for education. Stud Art Educ. 51(2):102–114. doi:10.1080/00393541.2010.11518795.

- Rosa H. 2016. Resonanz: eine Soziologie der Weltbeziehung. 1 ed. Berlin (Germany): Suhrkamp.

- Savin-Baden M, Wimpenny K. 2014. A practical guide to arts-related research. Rotterdam (Netherlands): Sense Publishers.

- Scheffer M. 2015. Dual thinking for scientists. Ecol Soc. 20(2):art3. doi:10.5751/ES-07434-200203.

- Schultz PW. 2001. The structure of environmental concern: concern for self, other people, and the biosphere. J Environ Psychol. 21(4):327–339. doi:10.1006/jevp.2001.0227.

- Schultz PW. 2002. Inclusion with nature: the psychology of human-nature relations. Psychol Sustainable Dev. Boston, MA, USA: Springer US:61–78. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-0995-0_4.

- Schultz PW. 2004. Implicit connections with nature. J Environ Psychol. 24(1):31–42. doi:10.1016/S0272-4944(03)00022-7.

- Schultz PW, Tabanico J. 2007. Self, identity, and the natural environment: exploring implicit connections with nature. J Appl Soc Psychol. 37(6):1219–1247. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2007.00210.x.

- Shepardson DP, Wee B, Priddy M, Harbor J. 2007. Students’ mental models of the environment. J Res Sci Teach. 44(2):327–348. doi:10.1002/tea.20161.

- Silvas DV. 2013. Measuring an emotional connection to nature among children. Colorado State University. Available at: https://dspace.library.colostate.edu/bitstream/handle/10217/78868/Silvas_colostate_0053A_11603.pdf;jsessionid=1uby4fhgox2gj1rop2nokdk8g3?sequence=1.

- Soga M, Gaston KJ. 2016. Extinction of experience: the loss of human-nature interactions. Front Ecol Environ. 14(2):94–101. doi:10.1002/fee.1225.

- Spangenberg JH. 2011. Sustainability science: a review, an analysis and some empirical lessons. Environ Conserv. 38(3):275–287. doi:10.1017/S0376892911000270.

- Springgay S. 2008. Being with a/r/tography. Rotterdam (Netherlands): Sense Publishers.

- Tam K-P. 2013a. Concepts and measures related to connection to nature: similarities and differences. J Environ Psychol. 34(June 2013):64–78. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.01.004.

- Tam K-P. 2013b. Dispositional empathy with nature. J Environ Psychol. 35:92–104. Elsevier Ltd. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.05.004.

- Thomashow M. 1995. Ecological identity: becoming a reflective environmentalist. Cambridge (MA, USA): MIT Press.

- Trigwell JL, Francis AJP, Bagot KL. 2014. Nature connectedness and eudaimonic well-being: spirituality as a potential mediator. Ecopsychology. 6(4):241–251. doi:10.1089/eco.2014.0025.

- Van Borek S. 2013. Natural capital: illuminating the true value of nature’s services through community-engaged, site-specific creative production and exhibition. Sustainability: J Rec. 6(5):282–288. doi:10.1089/SUS.2013.9838.

- Von Wehrden H. 2017. Methodological challenges in sustainability science: a call for method plurality, procedural rigor and longitudinal research. Challenges Sustainability. 5(1):35–42. doi:10.12924/cis2017.05010035.

- Vroegop J. 2014. Nature connectedness & winter camping: a combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches. Linköping (Sweden): Linköping University.

- Windhorst E, Williams A. 2015. Growing up, naturally: the mental health legacy of early nature affiliation. Ecopsychology. 7(3):115–125. doi:10.1089/eco.2015.0040.

- Zelenski JM, Nisbet EK. 2014. Happiness and feeling connected: the distinct role of nature relatedness. Environ Behav. 46(1):3–23. doi:10.1177/0013916512451901.

- Zurba M, Berkes F. 2014. Caring for country through participatory art: creating a boundary object for communicating Indigenous knowledge and values. Local Environ. 19(8):821–836. doi:10.1080/13549839.2013.792051.

- Zylstra MJ, Knight AT, Esler KJ, Le Grange LL. 2014. Connectedness as a core conservation concern: an interdisciplinary review of theory and a call for practice. Springer Sci Rev. 2(1–2):119–143. doi:10.1007/s40362-014-0021-3.